Abstract

Background and Purpose

States and counties in the US began implementing regional systems of acute stroke care in the first decade of the 21st century, whereby emergency medical services (EMS) systems preferentially route acute stroke patients directly to primary stroke centers (PSCs). The pace, geographic range, and population reach of regional stroke system implementation has not been previously delineated.

Methods

Review of legislative archives, internet and media reports, consultation with American Heart Association/American Stroke Association and Centers for Disease Control staff, and phone interviews with state public health and emergency medical service officials from each of the fifty states.

Results

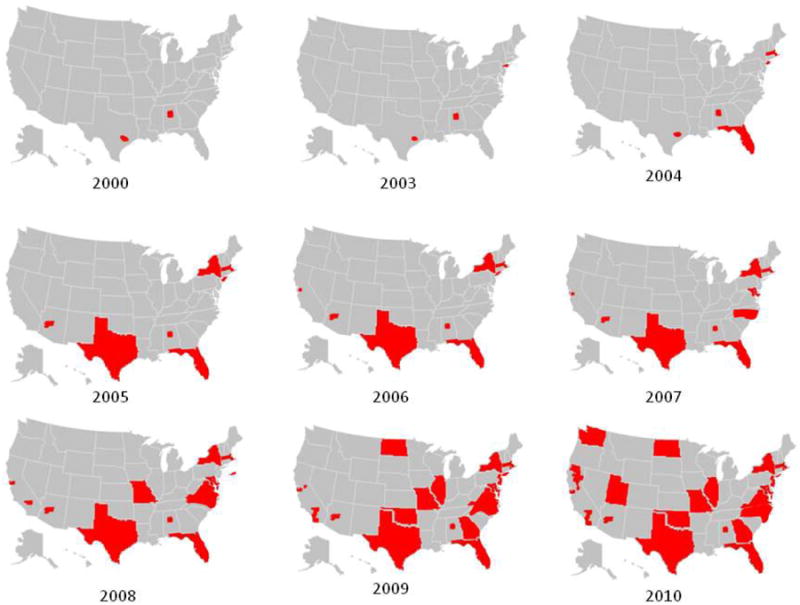

The first counties to adopt regional regulations supporting routing of acute stroke patients to PSCs were in Alabama and Texas in 2000; the first states were Florida and Massachusetts in 2004. By 2010, 16 states had state-level legislation or regulations to enable EMS routing to PSCs, as did counties in 3 additional states. The US population covered by routing protocols increased substantially in the latter half of the decade, from 1.5% in 2000, to 53% of the U.S. population by the end of 2010.

Conclusions

The first decade of the 21st century witnessed a remarkable structural transformation in acute stroke care - by the end of 2010, over half of all Americans were living in states/counties with EMS routing protocols supporting the direct transport of acute stroke patients to primary stroke centers. Additional efforts are needed to extend regional stroke systems of care to the rest of the US.

Keywords: All Cerebrovascular disease/Stroke, Outcome research, Emergency medicine and stroke, Health policy

Background and Purpose

At the start of the 21st century, stroke was the third leading cause of death and leading cause of disability among Americans. In 2000, a vision for regional organization of stroke care was first promulgated by the Brain Attack Coalition (BAC), launching the Stroke Center movement in the United States.(1) The BAC document recognized that: 1) the two interventions of proven value in acute stroke care, intravenous thrombolysis within 3 hours of onset and organized supportive care on a Stroke Unit, were not universally available, and 2) their successful implementation required institutional level commitment from hospital administration to integrate stroke care provided by emergency physicians, stroke specialists, nursing, radiology, pharmacy, and additional support services. The BAC recommended EMS systems train paramedics to recognize stroke patients in the field and preferentially route ambulances directly to primary stroke centers certified to be able to deliver standard acute stroke therapies reliably and rapidly. Subsequent policy and guideline statements from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) and the Brain Attack Coalition refined recommendations for organization of regional systems acute stroke care.(2-6)

The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (TJC) first began certifying Primary Stroke Centers in December 2003. Other national hospital certifying organizations, including Det Norske Veritas (DNV) and Healthcare Facilities Accreditation Program (HFAP), later developed similar certification programs.Some states, such as Florida and New Jersey, developed their own facility certifying programs, generally with TJC-overlapping criteria.(7)

In the United States, EMS transport policies are largely determined by state and county, rather than federal legislation and regulation. Given interest in collaborative efforts between EMS and neurologists in improving acute stroke outcomes, documenting trends in routing protocol policy expansion is essential for illustrating the growing recognition of the importance of regional stroke system development.

Methods

We identified 1) stroke system routing protocol legislation or regulation in US states and counties in December 2010, and 2) for jurisdictions with active regional stroke systems of care, the year of first passage of enabling legislation by the state legislature or adoption of enabling regulation by the applicable state or county authority. Resources queried included: 1) online legislative databases, 2) public health and emergency medical officials from each of the fifty states, 3) staff tracking prehospital stroke routing policies at the AHA/ASA and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and 4) county-level EMS or public health department officials. Initial queries using legislative databases were performed; individuals from each state's Department of EMS and/or Department of Public Health were contacted for verbal verification; the resulting preliminary list was compared with lists maintained by the AHA/ASA and CDC. Discrepancies were further investigated with online searches and phone calls.

Populations were quantified using online U.S. census databases from 2000 to 2010.

Results

In 2000, counties in Alabama and Texas first began routingacute stroke patients to stroke-designated hospitals. The first states to adopt policies supporting routing of acute stroke patients preferentially to Primary Stroke Centers were Massachusetts and Florida in 2004. By 2010, sixteen states, along with counties in three additional states, had acute EMS stroke routing protocol policies (Figure 1). In 2000,1.5% of the US population lived in areas that were covered by these routing protocols. By the end of the decade, 53% of the US population lived in areas that had legislation, regulations, or policies in support of EMS acute stroke routing protocols (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Cartographs depicting the dissemination of acute stroke EMS preferential routing systems to stroke centers in the United States 2000-2010.

Table 1. States and counties with acute stroke routing protocols by year.

| Year | State/County | Population covered (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Alabama – Blount, Chilton, Jefferson, St. Clair, Shelby, Walker, Winston County, Texas – Harris County | 4,471,933 (1.5) |

| 2003 | New York – Queens, Kings County | 290,326,418 (3) |

| 2004 | Massachusetts, Florida | 293,655,404 (11) |

| 2005 | New York, Texas, Arizona – Maricopa County | 71,024,756 (24) |

| 2006 | California – Santa Clara County | 73,779,894 (25) |

| 2007 | Maryland, California – San Francisco County | 81,189,754 (27) |

| 2008 | Missouri, Virginia, California – Alameda, San Mateo, Kern County | 98,690,632 (32) |

| 2009 | Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Vermont, California – Los Angeles, Orange, Sacramento, San Diego County | 154,585,210 (50) |

| 2010 | Utah, Washington, California – Nevada, Placer, Sutter, Yolo, Yuba, Colusa, Butte, Tehama, Shasta, Siskiyou County | 164,705,539 (53) |

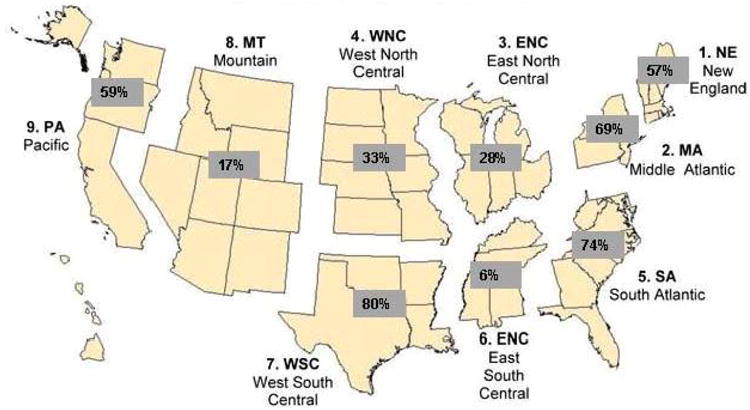

Population coverage in 2010 varied considerably by census region (Figure 2). The greatest coverage was in the West South Central region at 80%, and the lowest covered region was the East South Central region at 6%.

Figure 2.

Cartograph of United States by census region, and percentage of population covered by acute stroke EMS routing protocols in 2010.

Conclusions

Regional stroke systems increased in adoption throughout the period from 2000 – 2010. Concurrent with the development and publication of policy statements, continued data demonstrating the effectiveness of thrombolytic therapy and organized stroke care,(8-9) data publication from successful pilot projects in metropolitan Houston and New York City,(10-11) launch of a stroke center certification process by TJC, the development of telemedicine for stroke, and effective advocacy campaigns, adoption of local and state policies and regulations to create stroke systems of care expanded throughout the decade.12

This study has limitations. We identified the year of legislation passage or regulation adoption, not the dates of actual implementation of routing in the field, which typically occurs after a delay of several months. Also, state or county-level legislative/regulatory policies often enabled and promoted, but did not mandate, adoption of preferential EMS routing policies for acute stroke patients. Given wide geographic variations in distances to hospitals, EMS legislation/regulation in the US frequently leaves final details and mandating authority to County and other local EMS provider agencies. Another study limitation is the full details of each state and county's EMS routing system policy are not explored, including which stroke center certifying bodies were specified (e.g. the Joint Commission, state Department of Public Health, County EMS Agency, etc.) and which patients could be re-routed (all, under 6 hours, under 3 hour, etc.) A final limitation is that we confined our analysis to the United States, but the acute system of care movement has been an international in scope over the past decade.

By 2010, over 147 million Americans still did not have assured access to hospitals certified to provide standard acute stroke care. This inequitable access to effective health care is an important challenge to the American health system, as the frequency of acute stroke is projected to increase with the aging of the U.S. populace.(12) The pattern of uptake of regional stroke systems from 2000-2010 suggests a greater tendency for early adoption by states and counties with greater population density. Fortunately, several advances make implementation of regional acute stroke systems in currently uncovered states and counties an achievable goal, including stroke telemedicine, a growing cadre of vascular neurologists and neurohospitalists well-trained in acute stroke care, wide acceptance of the importance of routing patients to directly to stroke centers by the national EMS leadership,(13) and increasing penetration of U.S. stroke center designation.(14) If public health officials, legislators, hospital associations, and EMS medical directors work to ensure equitable access to proven, effective acute stroke care,(15) regional acute stroke care system coverage for all Americans can be achieved within the next few years.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jeffrey Ranous and the American Heart Association.

Dr. Saver is an employee of the University of California (UC), which holds a patent on retriever devices for stroke. The UC Regents also receive funds for his service and that of other faculty on scientific advisory boards for CoAxia, Inc., Concentric Medical, Talecris Biotherapeutics, Ferrer, AGA Medical Corporation, BrainsGate, PhotoThera, Ev3, and Sygnis Bioscience GmbH & Co. KG. Dr. Saver is an unpaid site investigator in multicenter clinical trials sponsored by AGA Medical Corporation, Lundbeck Inc., and GlaxoSmithKline for which the UC Regents received payments based on clinical trial contracts for the number of subjects enrolled; and is a site investigator in the NIH IRIS, CLEAR, IMS 3, SAMMPRIS, and VERITAS multicenter clinical trials for which the UC Regents receive payments based on clinical trial contracts for the number of subjects enrolled.

Disclosures: Dr. Song received support from the University of California, Los Angeles, Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly (RCMAR/CHIME) under NIH/NIA Grant P30-AG021684, and the content does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA or the NIH. Dr. Song is supported by the American Heart Association/Pharmaceutical Roundtable – Spina Outcomes Research Center.

References

- 1.Alberts MJ, Hademenos G, Latchaw RE, Jagoda A, Marler JR, Mayberg MR, et al. Recommendations for the establishment of primary stroke centers. Brain Attack Coalition JAMA. 2000;283:3102–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.23.3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams R, Acker J, Alberts M, Andrews L, Atkinson R, Fenelon K, et al. Recommendations for improving the quality of care through stroke centers and systems: an examination of stroke center identification options: multidisciplinary consensus recommendations from the Advisory Working Group on Stroke Center Identification Options of the American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2002;33:e1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberts MJ, Latchaw RE, Selman WR, Shephard T, Hadley MN, Brass LM, et al. Recommendations for comprehensive stroke centers: a consensus statement from the Brain Attack Coalition. Stroke. 2005;36:1597–616. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170622.07210.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwamm LH, Pancioli A, Acker JE, 3rd, Goldstein LB, Zorowitz RD, Shephard TJ, et al. Recommendations for the establishment of stroke systems of care: recommendations from the American Stroke Association's Task Force on the Development of Stroke Systems. Stroke. 2005;36:690–703. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000158165.42884.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acker JE, III, Pancioli AM, Crocco TJ, Eckstein MK, Jauch EC, Larrabee H, et al. Implementation Strategies for Emergency Medical Services Within Stroke Systems of Care: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Expert Panel on Emergency Medical Services Systems and the Stroke Council. Stroke. 2007;38:3097–115. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.186094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams HP, Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Brass L, Furlan A, et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38:1655–711. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.181486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Toole L, Slade CP, Brewer GA, Leech BA, Grinstead N, Rho EJ. Summary of Primary Stroke Center Policy in the States. The University of Georgia. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hacke W, Donnan G, Fieschi C, Kaste M, von Kummer R, Broderick JP, et al. Association of outcome with early stroke treatment: pooled analysis of ATLANTIS, ECASS, and NINDS rt-PA stroke trials. Lancet. 2004;363:768–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15692-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Audebert HJ, Schenkel J, Heuschmann PU, Bogdahn U, Haberl RL. Effects of the implementation of a telemedical stroke network: the Telemedic Pilot Project for Integrative Stroke Care (TEMPiS) in Bavaria, Germany. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:742–8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70527-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wojner AW, Persse D, Alexandrov AV, Grotta J. Weaving a web for stroke treatment: the Houston Paramedic/Emergency Stroke Treatment Outcomes Study (HoPSTO) Stroke. 2003;34:248A. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170700.45340.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gropen TI, Gagliano PJ, Blake CA, Sacco RL, Kwiatkowski T, Richmond NJ, et al. Quality improvement in acute stroke: the New York State Stroke Center Designation Project. Neurology. 2006;67:88–93. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223622.13641.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, Butler J, Dracup K, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Forecasting the Future of Cardiovascular Disease in the United States: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933–44. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820a55f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crocco TJ, Grotta JC, Jauch EC, Kasner SE, Kothari RU, Larmon BR, et al. EMS management of acute stroke--prehospital triage (resource document to NAEMSP position statement) Prehosp Emerg Care. 2007;11:313–7. doi: 10.1080/10903120701347844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Facts about Primary Stroke Center Certification. 2011 [cited 2011 March 11]; Available from: http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/Facts_about_Primary_Stroke_Center_Certification.pdf.

- 15.O'Toole LJ, Jr, Slade CP, Brewer GA, Gase LN. Barriers and facilitators to implementing primary stroke center policy in the United States: results from 4 case study states. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:561–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.197954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]