Interactions between a virus and a cell of the immune system can lead to suppression of the host’s immune response and/or suppression of viral replication. The two viruses infecting humans that this phenomenon has been most intensely studied in are measles virus (MV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (reviewed in ref. 1). In this issue of the Proceedings, two papers, one by Schlender et al. (2) and one by Blackbourn et al. (3) explore these concepts from different sides of the same coin.

Suppression of the immune system was first documented 88 years ago by Clement von Pirquet (4) who observed that the tuberculin skin test of immune individuals was depressed during the course of acute MV infection from just prior to the rash until 1–2 months or more following its appearance. Although transiently depressed, the degree of immune suppression was sufficiently severe that prior to the discovery of corticosteroids, MV was used therapeutically to treat autoimmune nephrotic syndrome (5). Furthermore, this suppression of immune function has long been appreciated as a major cause for the high mortality of currently over 1 million deaths per year and morbidity of currently over 40 million cases per year from MV infection (6, 7). These observations are firm, as is previous research documenting that MV infects cells of the immune system (8–16), interferes with cellular and humoral immune responses and lymphoid proliferation (for reviews see refs. 1 and 17–20) and causes cell cycle arrest in late G1 of infected T and B lymphocytes (21–23), but does not shut down protein synthesis of infected cells (23–26). However the mechanism(s) and molecules involved in the initiation and maintenance of this process have been poorly understood. The paper by Schlender et al. (2) in this issue addresses the mechanism of MV-induced immunosuppression.

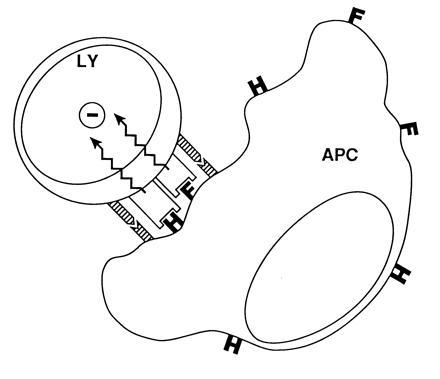

Schlender et al. (2) built on an earlier observation of Sanchez-Lanier et al. (27) that responding lymphocytes do not themselves need be infected by MV in order for their proliferation to be suppressed in vitro, but require cocultivation with MV-infected cells. They confirm this finding, and show that the suppressive effect is abolished, if MV-infected cells and responding lymphocytes are separated by a 0.2 μ membrane filter, suggesting that cell-to-cell contact is required and that soluble factors may not be involved. Investigating which viral protein(s) is involved in mediating the interaction that triggers immune suppression, Schlender et al. (2) found that neither the hemagglutinin nor the fusion protein of MV was able to trigger suppression alone when expressed on a non-lymphoid cell type, but that coexpression of both proteins did. These results are cartooned in Fig. 1. Whether both the MV hemagglutinin and fusion proteins are required to deliver signals to the lymphocyte, which affect its responsiveness; or alternatively, whether one of these proteins only functions to increase the overall avidity of the expressor–responder cell interaction (perhaps particularly necessary in the system used by Schlender et al. (2) where the expressor cell was not of lymphoid origin), or alternatively whether one protein affects the function of the other (e.g., it has been suggested that MV fusion may help MV hemagglutinin to form oligomeric structures at the cell surface) is unknown. In addition, the ligand(s) on the responding lymphocyte surface by which the signal that triggers immune suppression acts, remains unidentified. Furthermore, suppression does not appear dependent on an MV glycoprotein(s) binding the virus-cell surface receptor, the CD46 molecule (refs. 29–31; MV hemagglutinin not fusion binds to CD46) as mitogen-induced proliferation of rodent peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) or splenic lymphocytes is also inhibited after coculture with human MV–PBL. Rodent cells do not express the CD46 molecule (29, 31). In addition, proliferation of HeLa cells that have high expression of CD46 molecules was not inhibited when cocultivated with human MV–PBL. Surprising were the different cell type specificities generated in this system by the rodent (rat PBL; mouse splenocytes) versus human HeLa cells.

Figure 1.

A mechanism for how MV-induced suppression of lymphocyte proliferation may occur via cell–cell interactions mediated by MV glycoproteins. The interaction of a lymphocyte (LY) with MV hemagglutinin (H) and/or fusion (F) proteins expressed on the surface of an infected cell delivers a transmembrane signal (zig-zag arrows) to the responding cell, which arrests its proliferation (−). Adhesion proteins (striped bars) may facilitate suppression by enhancing cell–cell interactions. What the ligand(s) on the uninfected cell are, or the signal, is unknown. The cartoon shows the proposed interaction between an infected cell (displayed as an antigen-presenting cell: APC) and an uninfected cell. Evidence for components of this model is provided by Schlender et al. (2) and was proposed earlier by Borrow and Oldstone (28). [Reprinted with permission from ref. 28 (Copyright 1995, Springer, Berlin).]

These studies appear to stand in contrast to a paper by Karp et al. (32) reporting that cross-linking of the CD46 molecule with MV hemagglutinin, antibody to CD46 or with complement activation product C3b, is a required membrane event leading to inhibition of the production of the cytokine interleukin 12 and the postulated immunosuppression associated with MV infection. Thus, two pathways by which MV proteins may trigger immunosuppression are reported. The first by Schlender et al. (2) involves MV hemagglutinin and fusion joint activity and occurs independent of CD46, and the second by Karp et al. (32) is CD46 dependent and almost certainly involves MV hemagglutinin interaction. But perhaps these two pathways (and others?) are both involved. Karp et al. (32) did not directly evaluate the effect of interleukin 12 reduction on measles virus immunosuppression (i.e., report on functional studies), whereas as acknowledged by Schlender et al. (2) the effects of cytokines in the local milieu cannot be completely ruled out. More data will be required to clarify these issues, as will studies that define the immunosuppressive mechanism in vivo. Both the Schlender and Karp studies use in vitro models. Only then will the puzzle of MV-induced immunosuppression first presented by von Pirquet more than 88 years ago be solved.

The paper by Blackbourn et al. (3) in this issue of the Proceedings focuses on the other side of the coin, that is the ability of CD8+ T cells in lymph nodes from HIV-infected individuals to decrease virus load in infected CD4+ lymphocytes. The importance of host T-lymphocyte response (CTL) in control of many viral infections is supported by either evidence of the failure of CTL-deficient hosts to cleanse viruses from tissues during acute infections or direct evidence of their inability to lower or keep low viral loads during persistent infections. In HIV infection, HIV-specific CD8+ CTL responses have been found prior to the generation of anti-HIV antibodies and are noted to be temporally associated with the fall in viremia and viral load during the acute phase of HIV-1 infection (33, 34). Furthermore, the loss of anti-HIV CTL in the later stages of disease correlates with the reemergence of high viral loads (33, 34). CTL recognize infected cells as foreign. In the conventional way, CTL recognize proteolytic fragments of viral proteins that are presented at the cell surface by the major histocompatibility complex glycoproteins (35, 36). Two consequences may follow. First, CTL may directly lyse the infected cell (37–39), thus diminishing it as a factory able to produce virus. Second, CTL can release cytokines, notably interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α, which are able to interfere with viral replication, transcription, or assembly and thereby clear infectious virus and viral sequences from cells without lysing them (39–42). Both mechanisms require triggering by a major histocompatibility complex-restricted recognition event and are likely complementary and likely occur together with the target (tissue) being attacked favoring enhanced participation of one pathway over the other in virus control (39, 41). [Reprinted with permission from ref. 28 (Copyright 1995, Springer, Berlin).]

Levy and associates (42) reported an unconventional way that CD8+ T lymphocytes recognize and control virus infection. They found CD8+ T lymphocytes that function without major histocompatibility complex restriction and lower viral loads in the absence of lysis and action of known cytokines, but with the release of a soluble suppressor factor. Blackbourn et al. (3) show for the first time that such “unconventional” CD8+ T-cell activity is found in vivo. They report that these CD8+ T cells are present in lymph nodes of HIV-infected individuals who better control their HIV infection, i.e., have lower viral loads, but are absent or have diminished activity in lymph nodes of patients who fail to control HIV loads. These kinds of observations (reviewed ref. 43), coupled with others reporting on HIV and other human viral infections being controlled in association with CTL responses, the control of many viral infections by individuals with genetic disorders of immunoglobulin synthesis, and the use of animal models, all clearly indicate that CTL responses during infection or following solicitation by vaccination are important mediators of the control of viruses. The ability to define the peptides of viral proteins that function as recognition units for CTL (44), the ability to incorporate such “epitopes” as short oligonucleotides in vaccines (45), and the knowledge of what items are required to maintain CTL activity in vivo over time to be effective and efficient (46, 47) speak to the inclusion of this component of the immune response along with antibodies for effective vaccination. Finally, the current attempts to adoptively transfer CTL into persistently infected individuals (reviewed in ref. 48) should shortly allow a direct assessment of the role of this arm of the immune response in the control of viral infections.

References

- 1.McChesney M B, Oldstone M B A. Adv Immunol. 1989;45:335–380. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60696-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlender J, Schnorr J-J, Spielhofer P, Cathomen T, Caltaneo R, Billeter M A, ter Meulen V, Schneider-Schavlies S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13194–13199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackbourn D J, Mackewicz C E, Barker E, Hunt T K, Hemdier B, Haase A T, Levy T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13125–13130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Pirquet C. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1908;30:1297–1300. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumberg R W, Cassady H A. Am J Dis Child. 1947;63:151–166. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1947.02020370015003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clements C J, Cutts F. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;191:13–34. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78621-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin D E, Bellini W J. In: Fields Virology. Fields B N, Knipe D, Howley P, Channock R, Monath T, Melnick J, Roizman B, Straus S S, editors. Philadelphia: Lippincott–Raven; 1996. pp. 1267–1312. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papp K. Bull Acad Med (Paris) 1937;117:46–51. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gresser J, Chany C. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1963;113:695–698. doi: 10.3181/00379727-113-28465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whittle H C, Dossetor J, Oduloju A, Bryceson A, Greenwood B M. J Clin Invest. 1978;62:678–684. doi: 10.1172/JCI109175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyypia T, Korkiamaki P, Vainionpaa R. J Exp Med. 1985;161:1261–1271. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.6.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneider-Schaulies S, Kreth H W, Hofman G, Billeter M, ter Meulen V. Virology. 1991;182:703–711. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90611-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joseph B S, Lampert P W, Oldstone M B A. J Virol. 1975;16:1638–1649. doi: 10.1128/jvi.16.6.1638-1649.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan J L, Barry D W, Lucas S J, Albrecht P. J Exp Med. 1975;142:773–784. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.3.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huddlestone J R, Lampert P W, Oldstone M B A. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1980;15:502–509. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(80)90062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esolen L M, Ward B J, Moench T R, Griffin D E. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:47–52. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Casali P, Rice G P A, Oldstone M B A. J Exp Med. 1994;159:1322–1337. doi: 10.1084/jem.159.5.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smithwick E M, Berkovich S. In: Cellular Recognition. Smith R T, Good R A, editors. New York: Appleton Century Crafts; 1969. p. 131. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zweiman B. J Immunol. 1971;106:1154–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucas C J, Galana J M D, Ubels-Postma J. Cell Immunol. 1977;32:70–85. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McChesney M B, Kehrl J H, Valsamakis A, Fauci A S, Oldstone M B A. J Virol. 1987;61:3441–3447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.11.3441-3447.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McChesney M B, Altman A, Oldstone M B A. J Immunol. 1988;140:1269–1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanagi Y, Cubitt B A, Oldstone M B A. Virology. 1992;187:280–289. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90316-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haspel M V, Pellegrino M A, Lampert P W, Oldstone M B A. J Exp Med. 1977;146:146–156. doi: 10.1084/jem.146.1.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ilonen J, Salonen R, Marusyk R, Salmi A. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:247–254. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-1-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salonen R, Ilonen J, Salmi A. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;75:376–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez-Lanier M, Guerin P, McLaren L C, Bankhurst A D. Cell Immunol. 1988;116:367–381. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(88)90238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borrow P, Oldstone M B A. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;191:85–100. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78621-1_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naniche D, Varior-Krishnan G, Cervoni F, Wild F, Rossi B, Rabourdin-Combe C, Gerlier D. J Virol. 1993;67:6025–6032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6025-6032.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dorig R E, Marcil A, Chopra A, Richardson C D. Cell. 1993;75:295–305. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80071-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manchester M, Liszewski M K, Atkinson J, Oldstone M B A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2161–2165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karp C L, Wysocka M, Wahl L M, Ahearn J M, Cuomo P J, Sherry B, Trinchieri G, Griffin D E. Science. 1989;273:228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koup R A, Safrit J T, Cao Y, Andrews C A, McLeod G, Borkowsky W, Farthing C, Ho D D. J Virol. 1994;68:4650–4655. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4650-4655.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borrow P, Lewicki H, Hahn B H, Shaw G M, Oldstone M B A. J Virol. 1994;68:6103–6110. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6103-6110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zinkernagel R M, Doherty P C. Nature (London) 1974;248:701–702. doi: 10.1038/248701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Townsend A R M, Rothbard J, Gotch F M, Bahadur G, Wraith D, McMichael A J. Cell. 1986;44:959–968. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark W R, Walsh C, Glass A, Matloubian M, Ahmed R. Intl Rev Immunol. 1995;13:1–14. doi: 10.3109/08830189509061734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kagi D, Ledermann B, Burki K, Seiler P, Odermatt B, Olsen J, Podack E R, Zinkernagel R, Hengartner H. Nature (London) 1994;369:31–37. doi: 10.1038/369031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oldstone M B A, Blount P, Southern P J, Lampert P W. Nature (London) 1986;321:239–243. doi: 10.1038/321239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tishon A, Eddleston M, de la Torre J C, Oldstone M B A. Virology. 1993;197:463–467. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guidotti L, Ando K, Hobbs M, Ishikawa T, Runkel L, Schreiber R, Chisari F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3764–3768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mackewicz C E, Yang L C, Lifson J D, Levy J A. Lancet. 1994;344:1671–1673. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90459-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oldstone M B A. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1994;189:1–8. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78530-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Falk K, Rotzschke O, Stevanovic S, Jung G, Rammensee H G. Nature (London) 1991;351:290–296. doi: 10.1038/351290a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitton J L, Sheng N, Oldstone M B A, McKee T A. J Virol. 1993;67:348–352. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.348-352.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tishon A, Lewicki H, Rall G, von Herrath M, Oldstone M B A. Virology. 1995;212:244–250. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Matloubian M, Concepcion R J, Ahmed R. J Virol. 1994;68:8056–8063. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8056-8063.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riddell S R, Greenberg P D. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1994;189:9–34. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78530-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]