Abstract

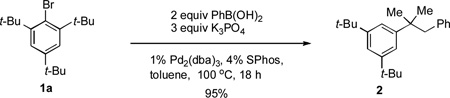

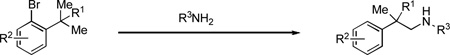

The Pd(0)-catalyzed intermolecular C–H amination of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds using aryl amines as the nitrogen source is disclosed. Either the C–N cross-coupling product or the C–H amination product could be accessed selectively by adjusting the steric environment of the substrate.

Keywords: C–H amination, unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds, palladium, catalysis

Nitrogen-containing compounds are ubiquitous among biologically active molecules.[1] Consequently, the development of efficient methods to form carbon-nitrogen bonds is of great importance. From a synthetic standpoint, a strategy involving transition metal-catalyzed C–H bond activation followed by C–N bond formation represents an extremely attractive approach for installing nitrogen functional groups.[2] In fact, great achievements have been made based on amination of C(sp2)–H bonds,[3] as well as activated C(sp3)–H bonds.[3h, 4] However, the activation of a simple C(sp3)–H bond followed by C–N bond formation remains a challenge, especially in an intermolecular fashion.[5] To the best of our knowledge, the intermolecular C–H amination of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds has only been reported using in situ-generated, highly reactive nitrene intermediates.[6] Thus, the development of complementary methods is strongly desired. Herein, we report on the Pd(0)-catalyzed intermolecular C–H amination of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds using aryl amines as the nitrogen source.

|

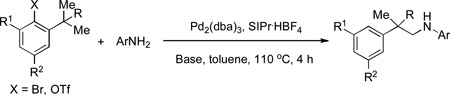

(1) |

During our investigation of Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling processes,[7] we disclosed that the reaction of 1-bromo-2,4,6-tri-tert-butylbenzene (1a) with phenylboronic acid produced the α,α-dimethyl-β-phenyl hydrostyrene, 2, in 95% yield, instead of the desired biaryl [Eq. (1)]. This transformation likely proceeds via a pathway involving a tandem C–H activation/Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction. On the basis of these results, we postulated that a related transformation involving an intermolecular tandem C(sp3)–H activation/C–N coupling might be feasible [Eq. (2)].

|

(2) |

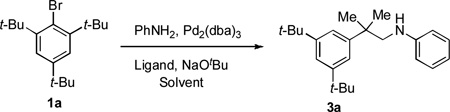

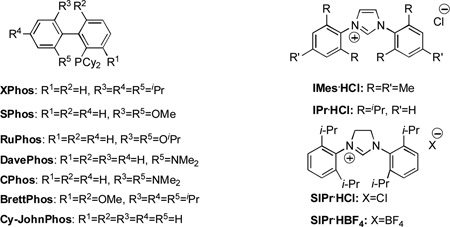

Our study commenced by examining the C–H amination of 1a to afford the corresponding N-(2-methyl-2-phenylpropyl)aniline, 3a, using Pd catalysts based on different ligands. While the biarylphosphane ligands developed in our laboratory led to catalysts that exhibited modest activities (Table 1, entries 1 to 7),[8] an examination of alternative ligand classes revealed that the utilization of a N-heterocyclic carbene ligand (SIPr·HBF4) provided a significantly improved reaction efficiency to afford 3a in 80% yield (Table 1, entry 13).[9] Further optimization of the solvent system led to an 83% isolated yield of 3a (Table 1, entry 14).

Table 1.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ligand | Yield [%][e] |

Entry | Ligand | Yield [%][e] |

| 1 | XPhos | 30 | 8[c] | PCy3·HBF4 | 0 |

| 2 | SPhos | 23 | 9[c] | PtBu3·HBF4 | 59 |

| 3 | RuPhos | 32 | 10[c] | IMes·HCl | 0 |

| 4 | DavePhos | 7 | 11[c] | IPr·HCl | 30[f] |

| 5 | CPhos | 23 | 12[c] | SIPr·HCl | 72 |

| 6 | BrettPhos | 0 | 13[c] | SIPr·HBF4 | 86 (80) |

| 7 | Cy-JohnPhos | 0 | 14[d] | SIPr·HBF4 | 88 (83) |

| |||||

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.5 mmol), PhNH2 (0.6 mmol), NaOtBu (0.75 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (5 mol %), ligand (20 mol %), dioxane (5 mL), 120 °C, 40 h.

The reaction reached 100 % conversion, unless otherwise noted. The mass balance consists of product, reduced starting material and benzocyclobutene byproduct.

Reaction was run at 110 °C for 12 h.

Reaction was performed in toluene with 11 mol % ligand at 110 °C for 4 h.

Determined by GC, with dodecane as an internal standard. Yield of isolated 3a (1 mmol scale reaction) in parentheses.

The reaction reached 58 % conversion.

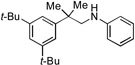

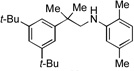

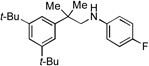

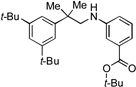

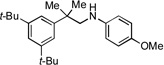

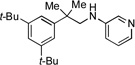

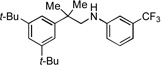

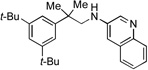

With optimized conditions in hand, we then evaluated the scope of the C–H amination of 1a with respect to the aryl amine component (Table 2). Both electron-rich and electron-deficient anilines gave the expected products in good to excellent yield (3a–3f), as well as anilines containing an ortho alkyl substituent (3e). We were pleased to find that heteroaryl amines such as 3-aminopyridine and 3-aminoquinoline also provided the corresponding products in good yields (3g, 3h). Unfortunately, N-substituted anilines and alkyl amines do not work under current reaction conditions. It is worth noting that, for reactions of 1a with aryl amines, no diaryl amines were observed despite the fact that SIPr·HBF4 is an efficient ligand for Pd-catalyzed C–N cross-coupling reactions.[10] We reasoned that this was likely due to the steric effects of the two ortho tert-butyl groups of 1a.

Table 2.

C–H Amination of 1a with Aryl Amines.[a]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Yield [%]b] |

Product | Yield [%]b] |

|

3a, 83% |  |

3e, 76% |

|

3b, 84% |  |

3f, 76% |

|

3c, 86% |  |

3g, 75% |

|

3d, 73% |  |

3h, 84% |

Reaction conditions: 1a (1.0 mmol), ArNH2 (1.2 mmol), NaOtBu (1.5 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (5 mol %), SIPr·HBF4 (11 mol %), toluene (10 mL), 110 °C, 4 h.

Isolated yield based on an average of two runs.

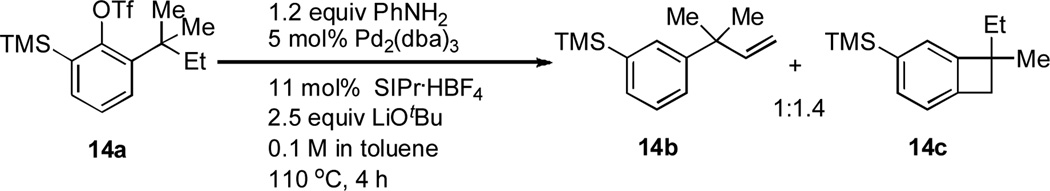

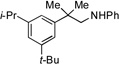

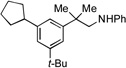

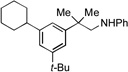

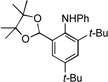

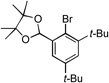

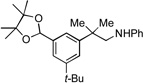

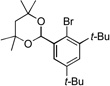

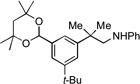

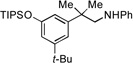

We next examined the reactivity of less sterically hindered substrates (Table 3). The reaction of 4a with aniline produced the diaryl amine 4b as the sole product (Table 3, entry 1). It is likely that the ortho methyl group does not possess the steric bulk necessary to suppress the direct C–N cross-coupling. Replacing the methyl group with a bulkier isopropyl, cyclopentyl or cyclohexyl group led to a complete suppression of the C–N cross-coupling pathway, affording the desired C–H amination products exclusively in 75–81% yields (Table 3, entries 2–4). No C–H amination of the isopropyl, cyclopentyl or cyclohexyl group was observed, indicating the amination is highly selective for only the methyl groups of the tert-butyl group. The steric influence on the outcome of this reaction could be further illustrated when using the diol-protected benzaldehyde substrates 8a, 9a and 10a. In the reaction of ethylene glycol-protected substrate 8a with aniline, only the direct C–N cross-coupling product 8b was observed (Table 3, entry 5). However, using a more sterically hindered pinacol-protecting group led to the formation of a 1:1 ratio of the C–N cross-coupling product 9b and the C–H amination product 9c (Table 3, entry 6). A further increase in size of the diol-protecting group resulted in exclusive formation of the C–H amination product 10b (Table 3, entry 7). Thus, a simple switch of diol from ethylene glycol to 2,4-dimethyl-2,4-pentanediol allows access to both the C–N cross-coupling product and the C–H amination product selectively. In addition, substrate 11a bearing an ortho OTIPS group underwent the C–H amination smoothly giving the desired product 11b in 80% yield (Table 3, entry 8). It should be noted that the reaction was not restricted to aryl bromide substrates. Starting from aryl triflate 12a, the corresponding C–H amination product 12b was also produced in good yield when LiOtBu was employed as base instead of NaOtBu (Table 3, entry 9). C–H amination of the TMS group was not observed. Employing 13a under the optimized reaction conditions provided the desired product 13b along with the olefin product 13c (Table 3, entry 10). By-product 13c possibly arose from the C–H activation of the ethyl group followed by β-H elimination.[11] Interestingly, the tert-amyl group in the para position plays a crucial role in producing the desired product, as 14a failed to yield any C–H amination product under the same reaction conditions. Instead, a mixture of olefin 14b and benzocyclobutene 14c[12] was obtained in a ratio of 1:1.4 and in an 81% combined yield (Scheme 1). It is worth noting that the reactive benzylic and ethereal hydrogens are tolerated in the reaction (Table 3, entries 1 to 7). Therefore, it provides an orthogonal approach to the existing nitrene methods.[2]

Table 3.

Amination of Unactivated C(sp3)–H Bonds with Aniline.[a]

| Entry | Substrate | Product | Yield [%][b] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

4a |  |

4b, 94% |

| 2 |  |

5a |  |

5b, 75% |

| 3 |  |

6a |  |

6b, 77% |

| 4 |  |

7a |  |

7b, 81% |

| 5 |  |

8a |  |

8b, 82% |

| 6 |  |

9a |  |

9b, 40% |

|

9c, 41% | |||

| 7 |  |

10a |  |

10b, 70% |

| 8 |  |

11a |  |

11b, 80% |

| 9[c] |  |

12a |  |

12b, 70% |

| 10[c] |  |

13a |  |

13b, 37% |

|

13c, 35% |

Reaction conditions: substrate (1.0 mmol), PhNH2 (1.2 mmol), NaOtBu (1.5 mmol), Pd2(dba)3 (5 mol %), SIPr·HBF4 (11 mol %), toluene (10 mL), 110 °C, 4 h.

Isolated yield based on an average of two runs.

LiOtBu (2.5 mmol) was used.

Scheme 1.

Reaction of 14a with aniline.

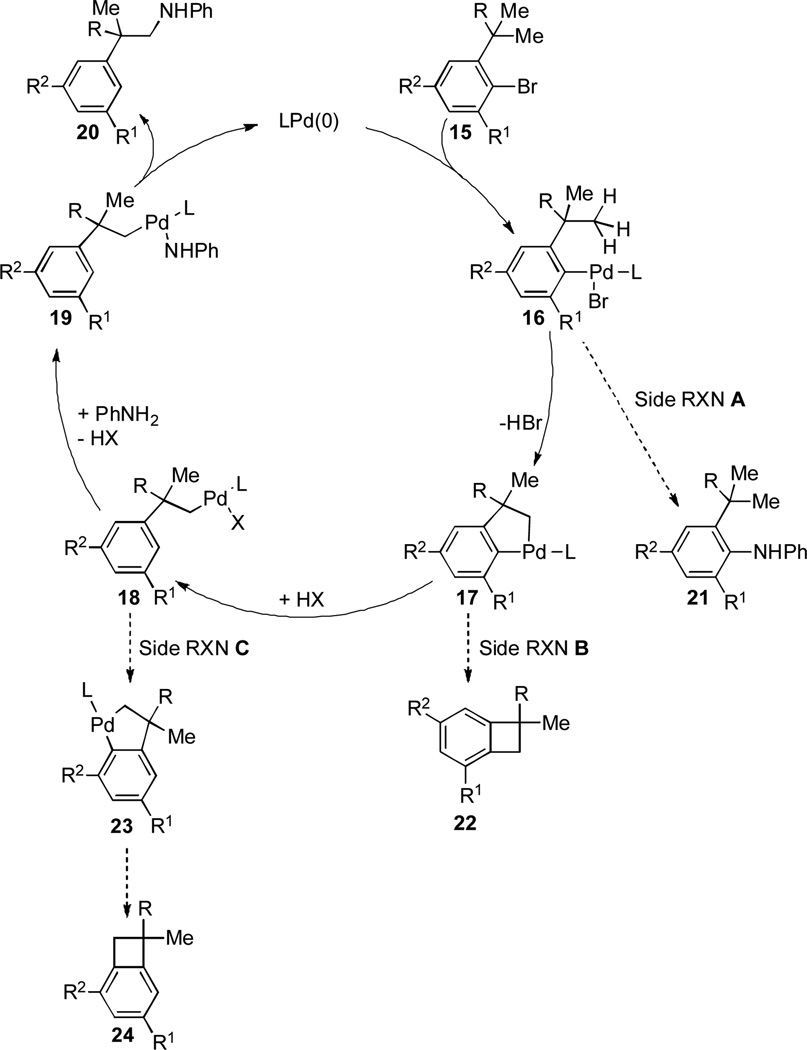

Based on the results described above, we propose a reaction mechanism as shown in Scheme 2. The oxidative addition of Pd0 to aryl bromide 15 gives intermediate 16, which would undergo C–H activation of one of the C(sp3)–H bonds to form palladacycle 17. Protonation of the C(sp2)–Pd bond of 17 affords the alkyl PdII species 18, which then undergoes transmetallation with aniline to give 19. Finally, reductive elimination occurs to yield the product 20 with concomitant regeneration of LPd(0). A sterically hindered R1 group helps to suppress the direct C–N cross-coupling (side reaction A), as well as the benzocyclobutene formation (side reaction B).[12] Therefore, it diminishes the formation of undesired by-products 21 and 22. In addition, as suggested by the results of the reaction of 14a with aniline, a bulky R2 group seems critical to minimize the formation of by-product 24 that most likely arises from the intramolecular C(sp2)–H activation of 18 followed by reductive elimination (side reaction C).[12]

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism of the tandem C–H activation/C–N cross-coupling.

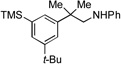

To gain additional insight into the steric influence of the substrates 8a, 9a, and 10a on direct C–N cross-coupling vs. C–H amination, we performed a computational study at the density functional theory (DFT) level with the hybrid functionals B3LYP.[13] The oxidative addition intermediates of 8a, 9a and 10a were evaluated (Table 4). The intermediates (OA1a, OA2a and OA3a) with the carbene ligand trans to the aromatic ring are found to be more stable. The calculated distances between the PdII atom and the C–H σ bond of the tert-butyl group and the bond angles, Pd–C1–C2, are listed in Table 4. It is worth noting that the distance decreases as the size of diol-protecting group increases; the Pd is being “pushed” toward the tert-butyl group as indicated by the decrease in the bond angle. In addition, the calculated distances are consistent with a three-center two-electron, agostic interaction between the PdII atom and the C–H σ bond in OA2a and OA3a.[12, 14] As recently demonstrated,[14c, 15] an agostic interaction increases the acidity of the C–H bond that is geminal to the agostic C–H bond. This is supported by the computed natural atomic charges. For OA3a, the agostic hydrogen atom has a less positive charge (+0.203) than either of the geminal hydrogen atoms (+0.227 and +0.225). Similar results were found for OA2a (agostic H: +0.150; geminal H: +0.209, 0.211). The shorter distance in OA3a suggests that the agostic interaction is likely stronger than that in OA2a. This stronger agostic interaction in OA3 confers a more acidic character on the geminal hydrogen atom to be deprotonated. Consequently, the tendency for the subsequent C–H activation rises from OA1a to OA3a (OA1a < OA2a < OA3a), which is indeed consistent with our experimental observations.

Table 4.

DFT Calculations of the Oxidative Addition Intermediates

|

In summary, we have developed a conceptually novel Pd(0)-catalyzed intermolecular C–H amination of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds using aryl amines as the nitrogen source. We have also demonstrated a selective access to both the C–N cross-coupling product and the C–H amination product by adjusting the steric environment of the substrate. To the best of our knowledge, this reaction is the first intermolecular unactivated C(sp3)–H bond activation/C–N bond-forming process that does not involve nitrenes. Further investigations to increase the generality of this process and to better understand its mechanism are currently underway in our laboratory.

Experimental Section

Typical procedure: In a nitrogen-filled glovebox, to an oven-dried test tube containing a magnetic stir bar, was added aryl bromide (1.0 mmol, 1.0 equiv), Pd2(dba)3 (46 mg, 5 mol %), SIPr·HBF4 (53 mg, 11 mol %), NaOtBu (144 mg, 1.5 mmol, 1.5 equiv), aryl amine (1.2 mmol, 1.2 equiv) and toluene (10 mL). The test tube was sealed with a Teflon-lined septum, removed from the glovebox, and heated at 110 °C in a pre-heated oil bath for 4 h. After the reaction was complete, the reaction mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature, filtered through a plug of silica gel and eluted with diethyl ether. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo and the crude product was purified by flash chromatography on silica gel.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Generous financial support from the National Institutes of Health (GM-46059) is gratefully acknowledged. The Bruker 400 MHz instrument used in this work was purchased with funding from the National Institutes of Health (GM 1S10RR13886-01). We are grateful to Georgiy Teverovskiy (MIT) for initial studies on DFT calculations and to Sophie Rousseaux (MIT) for helpful discussions.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- 1.a) Kibayashi C. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2005;53:1375. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Cheng JH, Kamiya K, Kodama I. Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 2001;19:152. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2001.tb00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sanchez C, Mendez C, Salas JA. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2006;23:1007. doi: 10.1039/b601930g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For recent reviews on C–H amination, see: Armstrong A, Collins JC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:2282. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906750. Thansandote P, Lautens M. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:5874. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900281. Collet F, Dodd RH, Dauban P. Chem. Commun. 2009:5061. doi: 10.1039/b905820f. Davies HML, Manning JR. Nature. 2008;451:417. doi: 10.1038/nature06485. Dick AR, Sanford MS. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:2439. Davies HML, Long MS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:3518. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500554. Muller P, Fruit C. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:2905. doi: 10.1021/cr020043t. Collet F, Lescot C, Dauban P. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1926. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00095g. Zalatan DN, Du Bois J. Top. Curr. Chem. 2010;292:347. doi: 10.1007/128_2009_19.

- 3.For selected examples of C–N bond formation following activation of C(sp2)–H bonds, see: Sun K, Li Y, Xiong T, Zhang J, Zhang Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1694. doi: 10.1021/ja1101695. Xiao B, Gong T-J, Xu J, Liu Z-J, Liu L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1466. doi: 10.1021/ja108450m. Tan YC, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3676. doi: 10.1021/ja100676r. Ng KH, Chan ASC, Yu WY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12862. doi: 10.1021/ja106364r. Inamoto K, Saito T, Hiroya K, Doi T. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:3900. doi: 10.1021/jo100557s. Monguchi D, Fujiwara T, Furukawa H, Mori A. J. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1607. doi: 10.1021/ol900298e. Mei TS, Wang XS, Yu JQ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:10806. doi: 10.1021/ja904709b. Wasa M, Yu JQ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:14058. doi: 10.1021/ja807129e. Jordan-Hore JA, Johansson CCC, Gulias M, Beck EM, Gaunt MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16184. doi: 10.1021/ja806543s. Tsang WCP, Munday RH, Brasche G, Zheng N, Buchwald SL. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:7603. doi: 10.1021/jo801273q. Brasche G, Buchwald SL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:1932. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705420. Chen X, Hao XS, Goodhue CE, Yu JQ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:6790. doi: 10.1021/ja061715q. Tsang WCP, Zheng N, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14560. doi: 10.1021/ja055353i. Wang Q, Schreiber SL. J. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5178. doi: 10.1021/ol902079g. Kienle M, Dunst C, Knochel P. J. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5158. doi: 10.1021/ol902056j. Kawano T, Hirano K, Satoh T, Miura M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:6900. doi: 10.1021/ja101939r. Zhao HQ, Wang M, Su WP, Hong MC. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010;352:1301. Wang HG, Wang Y, Peng CL, Zhang JC, Zhu QA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:13217. doi: 10.1021/ja1067993. Cho SH, Kim JY, Lee SY, Chang S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:9127. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903957. Miyasaka M, Hirano K, Satoh T, Kowalczyk R, Bolm C, Miura M. J. Org. Lett. 2010;13:359. doi: 10.1021/ol102844q. Guo S, Qian B, Xie Y, Xia C, Huang H. J. Org. Lett. 2010;13:522. doi: 10.1021/ol1030298.

- 4.For selected examples of C–H amination of activated C(sp3)–H bonds which include allylic, benzylic C–H bonds, and C–H bonds having heteroatoms or electron-withdrawing substituents on the carbon, see: Diaz-Requejo MM, Belderrain TR, Nicasio MC, Trofimenko S, Perez PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:12078. doi: 10.1021/ja037072l. Fructos MR, Trofimenko S, Diaz-Requejo MM, Perez PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11784. doi: 10.1021/ja0627850. Bhuyan R, Nicholas KM. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3957. doi: 10.1021/ol701544z. Pelletier G, Powell DA. Org. Lett. 2006;8:6031. doi: 10.1021/ol062514u. Liang JL, Yuan SX, Huang JS, Yu WY, Che CM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002;41:3465. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020916)41:18<3465::AID-ANIE3465>3.0.CO;2-D. Liang JL, Yuan SX, Huang JS, Che CM. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:3610. doi: 10.1021/jo0358877. Espino CG, Fiori KW, Kim M, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15378. doi: 10.1021/ja0446294. Fiori KW, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:562. doi: 10.1021/ja0650450. Zhang Y, Fu H, Jiang Y, Zhao Y. J. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3813. doi: 10.1021/ol701715m. Milczek E, Boudet N, Blakey S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6825. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801445. Fraunhoffer KJ, White MC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7274. doi: 10.1021/ja071905g. Reed SA, White MC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3316. doi: 10.1021/ja710206u. Liu GS, Yin GY, Wu L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:4733. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801009.

- 5.For an elegant example of intramolecular C–H amination of unactivated C(sp3)–H bonds, see: Neumann JJ, Rakshit S, Droge T, Glorius F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:6892. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903035.

- 6.a) Thu HY, Yu WY, Che CM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9048. doi: 10.1021/ja062856v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li ZG, Capretto DA, Rahaman R, He CA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:5184. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Liang CG, Robert-Pedlard F, Fruit C, Muller P, Dodd RH, Dauban P. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:4641. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Liang CG, Collet F, Robert-Peillard F, Muller P, Dodd RH, Dauban P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:343. doi: 10.1021/ja076519d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Gomez-Emeterio BP, Urbano J, Diaz-Requejo MM, Perez PJ. Organometallics. 2008;27:4126. [Google Scholar]; f) Collet F, Lescot C, Liang CG, Dauban P. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:10401. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00283f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barder TE, Walker SD, Martinelli JR, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4685. doi: 10.1021/ja042491j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For reviews on biarylphosphane ligands, see: Surry DS, Buchwald SL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6338. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800497. Surry DS, Buchwald SL. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:27. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00331J.

- 9.For recent reviews on N-heterocyclic carbenes, see: Nolan SP. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010;44:91. doi: 10.1021/ar1000764. Clavier H, Nolan SP. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:841. doi: 10.1039/b922984a. Marion N, Nolan SP. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1440. doi: 10.1021/ar800020y. Marion N, Diez-Gonzalez S, Nolan IP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:2988. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603380.

- 10.Marion N, Navarro O, Mei J, Stevens ED, Scott NM, Nolan SP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:4101. doi: 10.1021/ja057704z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Baudoin O, Herrbach A, Gueritte F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:5736. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hitce J, Retailleau P, Baudoin O. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:792. doi: 10.1002/chem.200600811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Jazzar R, Hitce J, Renaudat A, Sofack-Kreutzer J, Baudoin O. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:2654. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For a related study on benzocyclobutene formation (mechanism & scope), see: Chaumontet M, Piccardi R, Audic N, Hitce J, Peglion JL, Clot E, Baudoin O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:15157. doi: 10.1021/ja805598s.

- 13.See the Supporting Information for details.

- 14.a) Brookhart M, Green MLH, Parkin G. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:6908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610747104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lafrance M, Gorelsky SI, Fagnou K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14570. doi: 10.1021/ja076588s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Rousseaux S, Davi M, Sofack-Kreutzer J, Pierre C, Kefalidis CE, Clot E, Fagnou K, Baudoin O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10706. doi: 10.1021/ja1048847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Haller LJL, Page MJ, Macgregor SA, Mahon MF, Whittlesey MK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4604. doi: 10.1021/ja900953d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kefalidis CE, Baudoin O, Clot E. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:10528. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00578a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.