Abstract

Memory B cells are generated during an individual's first encounter with a foreign antigen and respond to re-encounter with the same antigen through cell surface immunoglobulin G (IgG) B cell receptors (BCRs) resulting in rapid, high-titered IgG antibody responses. Despite a central role for IgG BCRs in B cell memory, our understanding of the molecular mechanism by which IgG BCRs enhance antibody responses is incomplete. Here, we showed that the conserved cytoplasmic tail of the IgG BCR, which contains a putative PDZ-binding motif, associated with synapse-associated protein 97 (SAP97), a member of the PDZ domain–containing, membrane-associated guanylate-kinase family of scaffolding molecules that play key roles in controlling receptor density and signal strength at neuronal synapses. We showed that SAP97 accumulated and bound to IgG BCRs in the immune synapses that formed in response to engagement of the B cell with antigen. Knocking down SAP97 in IgG-expressing B cells or mutating the putative PDZ-binding motif in the tail impaired immune synapse formation, the initiation of IgG BCR signaling, and downstream activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Thus, heightened B cell memory responses are encoded, in part, by a mechanism that involves SAP97 serving as a scaffolding protein in the IgG BCR immune synapse.

Introduction

Memory responses are characterized by the rapid production of high-affinity, class-switched antibodies, which are predominantly of immunoglobulin G (IgG) sub-classes. Antibody memory is encoded, in part, in memory B cells that are generated during an individual's first encounter with an antigen and have high-affinity IgG B cell receptors (BCRs). In contrast, naïve B cells, which give rise to primary antibody responses upon the first encounter with antigen, have IgM and IgD BCRs (1). It has long been suspected that differences in the signaling capacities of IgM and IgG BCRs might account for the accelerated, high-titered antibody memory responses as compared to primary responses. However, IgM and IgG BCRs are both composed of a membrane-bound form of Ig (mIg) that associates in a 1:1 molar ratio with a heterodimer of Igα and Igβ, which contain immunoreceptor tyrosine activation motifs (ITAMs) in their cytoplasmic domains that are phosphorylated upon antigen binding to initiate signaling (2). Thus, differences in the signaling capacities of IgM and IgG BCRs must reflect functional differences in mIgM and mIgG. Indeed, in addition to differences in the extracellular domains of mIgM and mIgG, mIgM has no cytoplasmic tail, with just three amino acids predicted to face the cytoplasm; in contrast all mIgG subtypes have highly conserved cytoplasmic tails consisting of 28 amino acids. Early studies in vivo with transgenic mouse models clearly demonstrated that the cytoplasmic tail of mIgG was both necessary and sufficient for enhanced IgG memory antibody responses (3, 4). Biochemical studies suggested that the mIgG tail served to enhance Ca2+ responses in BCR signaling relative to that induced by mIgM (5–7). Comparing antigen-induced gene transcription profiles, Horikawa et al. showed that gene activation in mIgG-expressing (IgG+) B cells was qualitatively different than that in mIgM-expressing (IgM+) B cells (5), with the majority of the gene expression induced in IgM+ B cells diminished in IgG+ B cells. However, the molecular mechanism by which the mIgG cytoplasmic tail enhances the response of IgG BCR-expressing B cells is incompletely understood.

Waisman et al.(6) showed that the cytoplasmic tail of mIgG was able to partially replace the requirement for the Igα and Igβ heterodimer during B cell development, which suggested the possibility that the cytoplasmic tail of mIgG independently interacted with cytoplasmic BCR signaling–related molecules. The first evidence for a direct interaction between the cytoplasmic tail of IgG and a component of the BCR signaling cascade came from Engels et al.(8) who showed that a conserved Ig tail tyrosine (ITT) motif in the cytoplasmic domain of both mIgG and mIgE was phosphorylated upon crosslinking of IgG BCRs, which resulted in the recruitment of the adapter protein Grb2 and the enhancement of Ca2+ responses and B cell proliferation. This result indicated that once BCR signaling was initiated, the mIgG cytoplasmic tail functioned to enhance downstream signaling, raising the question of whether the mIgG cytoplasmic tail played a fundamental role in initiating signaling and forming the immunological synapse in IgG+ memory B cells.

Our understanding of the molecular events that initiate antigen-driven BCR signaling that lead to the formation of an immunological synapse has advanced dramatically with the use of total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy to image B cells as they first encounter antigen incorporated into lipid bilayers (9, 10). These studies provided evidence for an ordered series of events beginning with BCR oligomerization and microcluster formation, which triggered a dynamic spreading of the B cell over the bilayer and the formation of new microclusters, which was ultimately followed by a contraction event that concentrated the BCRs in an ordered immunological synapse. We previously compared the initiation of BCR signaling for IgM and IgG BCRs, and provided evidence that compared to IgM BCRs, IgG BCRs were enhanced in their ability to oligomerize and form active signaling BCR clusters and immunological synapses (11). We further showed that the enhanced antigen-induced clustering of IgG BCRs was dependent on the membrane-proximal 15 amino acid residues of the mIgG cytoplasmic tail, a region that does not overlap with the ITT motif described by Engels et al. (8) and had not been previously implicated in IgG BCR signaling. Here, we report that a member of the membrane-associated, guanylate-kinase (MAGUK) family, synapse-associated protein 97 (SAP97), is a binding partner of the membrane-proximal region of the cytoplasmic tail of mIgG and functions to enhance the accumulation of IgG BCRs in the B cell immunological synapse, which results in heightened signaling by IgG+ memory B cells.

Results

The cytoplasmic tail of mIgG binds to SAP97

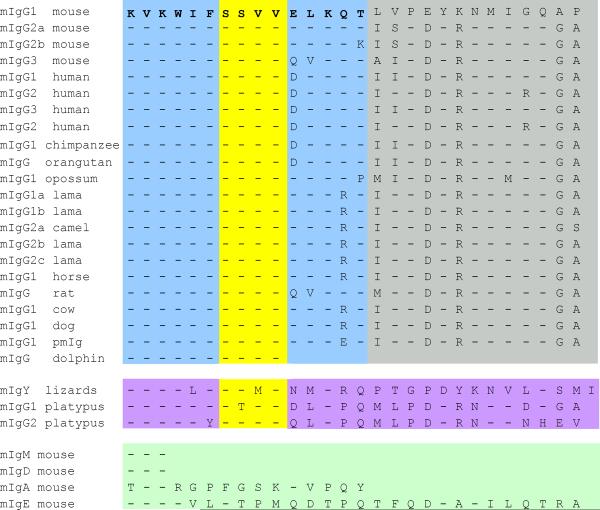

We recently determined that the 15-amino acid membrane-proximal region of the mouse mIgG tail (Fig. 1) was both necessary and sufficient for the enhanced microclustering and signaling of IgG BCRs at the immunological synapse compared to that of IgM BCRs (11). We noted that this membrane-proximal region contained the evolutionarily-conserved sequence SSVV, which is a putative type I postsynaptic density 95 (PSD95)/Disk large (Dlg)/Zona occludens 1 (PDZ) domain–binding motif (X-S/T-X-V) (12, 13). PDZ domains are protein interaction domains often found in multidomain scaffolding proteins that serve to assemble specific proteins into large complexes at defined locations in the cell. The SSVV sequence is conserved in all mIgG subtypes in both humans and mice and in all known mammalian IgG cytoplasmic tail sequences, including platypus mIgG2 (Fig. 1). Even the lizard mIgY contains a sequence that fits the PDZ domain–binding motif. We also examined the sequences of the cytoplasmic tails of mouse mIgA and mIgE, both of which can be expressed as BCRs; however, neither tail shares sequence similarity with the mIgG tails nor contains a putative PDZ domain–binding motif.

Fig. 1.

The cytoplasmic tails of mIgGs are highly conserved. Alignment of the amino acid sequences of all of the mIgG cytoplasmic tails in the NCBI database. Also shown are the sequences of the cytoplasmic tail of lizard mIgY and mouse mIgM, mIgD, mIgE, and mIgA. The region highlighted in blue (and containing the yellow region) indicates the membrane-proximal 15 amino acid residues that we previously showed were both necessary and sufficient for the enhanced microclustering and signaling of IgG BCRs as compared to that of IgM BCRs (11). The evolutionarily conserved sequence SSVV, highlighted in yellow, is a putative type I PDZ domain–binding motif (X-S/T-X-V) (12, 13).

To search for potential PDZ domain–containing binding partners for the mIgG tail, we performed immunoprecipitations of lysates of the mouse B cell myeloma cell line, J558L, with either a biotin-conjugated, membrane-proximal 15 amino acid peptide that contained the SSVV motif (N15SSVV) bound to streptavidin beads or a control biotin-conjugated peptide in which SSVV was changed to GGGG (N15GGGG). N15SSVV immunoprecipitated a 130-kD protein, which was absent in N15GGGG immunoprecipitates, that was recognized by a monoclonal antibody (mAb) that broadly recognizes members of the PDZ domain–containing, membrane-associated guanylate kinase family (anti-PAN-MAGUK) (12) (Fig. S1A). The anti-PAN MAGUK mAb itself immunoprecipitated a 130-kD protein from mouse B cell lysates that was identified by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry as SAP97 (Fig. S1B). A SAP97-specific mAb recognized the 130-kD protein in the N15SSVV immunoprecipitate from lysates of the mouse B cell line, A20 II1.6, which was absent in the samples immunoprecipitated with N15GGGG (Fig. S1, C and D). Collectively, these results suggested that SAP97 was a binding partner for the 15–amino acid, membrane-proximal peptide within the cytoplasmic tail of mIgG. SAP97 is a member of a subfamily of MAGUK proteins that consists of four proteins, PSD-95, PSD-93, SAP102, and SAP97. Of these, B cells have predominantly SAP97, as determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of mouse B cell lines and primary splenic B cells (Fig. S2A).

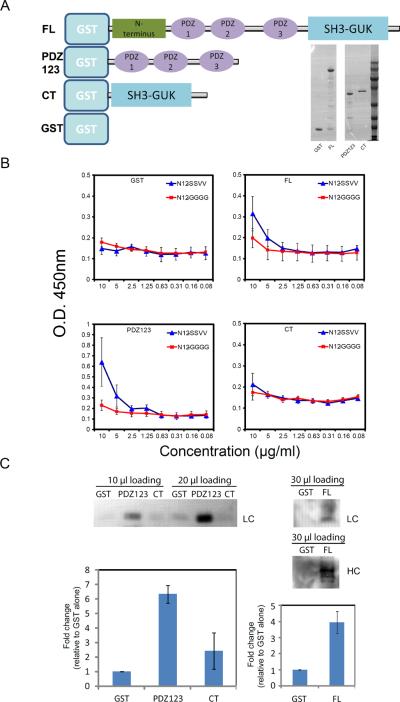

SAP97 and other members of the MAGUK family have been best characterized in neurons, where they play an essential role as synaptic scaffolding proteins in controlling the density, localization, and clustering of glutamate receptors and ion channels at the synapse, and by so doing control excitatory synaptic transmission (12, 13). SAP97 contains an N-terminal L27 domain and a proline (P), glutamic acid (E), serine (S) and threonine (T) rich (PEST) domain, three PDZ domains, and a C-terminal Src homology 3 (SH3)-GUK domain (Fig. 2A) (12, 13). To characterize the binding of SAP97 to the mIgG tail, we generated full-length SAP97 (FL) as well as the three PDZ domains (PDZ123) and the C terminal SH3-GUK domain (CT) of SAP97 as GST fusion proteins (Fig. 2A). By enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) in which N12SSVV or N12GGGG was coated onto the assay plates, we observed that both full-length SAP97 and the PDZ123 construct bound selectively to N12SSVV (Fig. 2B). The extent of binding of full-length SAP97 to N12SSVV was weaker than that of the PDZ123 domains of SAP97, which may be because of incomplete folding of the full-length SAP97 expressed in Escherichia coli. Indeed, the PSD-95 subfamily of PDZ scaffold proteins fold into compact structures and form N-terminal head-to-head multimers that may be essential to their function (12, 13). Such folding may not be achieved in proteins produced in E. coli. Neither the C-terminal SH3-GUK domain nor the GST control bound to either peptide (Fig. 2B). We also performed GST-pull downs from detergent lysates of A20II1.6 cells with GST, GST-PDZ123, GST-CT, and GST-FL-SAP97 constructs (Fig. 2C). When 10 to 20 μl of the puldown eluates were used we observed selective binding of Ig to GST-PDZ123 as compared to GST alone (Fig. 2C). In separate experiments, we observed selective binding of Ig to GST-FL-SAP97 as compared to GST alone, but only by loading larger amounts of the pulldown eluates for SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2C), consistent with the weak binding of GST-FL-SAP97 to the N15-SSVV peptide as determined by ELISA (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

The binding of SAP97 to the cytoplasmic tail of mIgG. (A) The GST fusion proteins that were expressed and purified as described in the Materials and Methods, including full-length SAP97 (FL), the three tandem PDZ domains of SAP97 (PDZ123), the C-terminal SH3-GUK domain of SAP97 (CT), and GST alone. These purified GST fusion proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining as shown in the gel on the right. (B) The purified proteins were tested by ELISA for their ability to bind to the N15-SSVV and N15-GGG peptides. Binding is indicated by the increased optical density (OD) at 450 nm. The data represent the mean ± SD from four independent experiments. (C) GST pull-down assays with GSH beads bound to the same amounts of purified GST alone or of the FL, PDZ123, and CT fusion proteins. Beads were incubated with A20 II1.6 cell lysates, centrifuged, washed, eluted into the same volume, and subjected to SDS-PAGE. For the GST, PDZ123, and CT pulldowns, 10 and 20 μl of the pulldown eluates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. In separate experiments, 30 μl of the eluates from samples containing GST alone or the FL construct were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Western blots were analyzed with mouse IgG-specific antibodies for light chain (LC) or heavy chain (HC). Bar graphs show a statistical comparison (mean ± SD from 5 independent experiments) showing the fold changes in the intensity of the PDZ123, CT or FL bands relative to those in the GST alone samples.

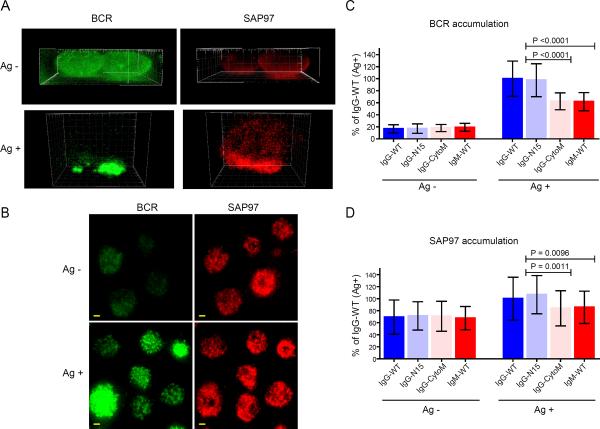

IgG BCRs induce increased accumulation of SAP97 in the immunological synapse

We determined the subcellular location of the BCR and SAP97 by confocal microscopic analysis of B cells placed on fluid lipid bilayers that either did or did not contain antigen (Fig. 3). After 10 min on the bilayers, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with fluorescently tagged antibodies specific for the BCR or SAP97. In the absence of antigen, the BCRs were dispersed over the B cell surface (Fig. 3A). SAP97 was located at the plasma membrane, but, in contrast to the BCR, SAP97 showed a clear polarization towards the interface of the B cell and the bilayer (Fig. 3A, movies S1–S4). In the presence of antigen in the bilayer, the BCRs accumulated in the immunological synapse at the interface with the bilayer, as previously described (14, 15), and SAP97 appeared to show an increased accumulation in the immunological synapse (movie S1–S4).

Fig. 3.

IgG BCRs enhance the accumulation of SAP97 in the immunological synapse. (A and B) Representative (A) two-color 3D images and (B) TIRF images of the BCR and SAP97 in J558L cells expressing reconstructed B1-8** NIP-specific BCRs. Cells were placed on planar lipid bilayers containing either no antigen or the antigen NIP-H12 for 10 min. Cells were then fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with fluorescently tagged antibodies specific for the BCR or for SAP97. (A) The 3D images are shown in side view (see movies S1 to S4 for 360° full views). (B) For the original 16-bit grey scale TIRF images, the display range was set from 0 to 500 for both BCR and SAP97 images to enable direct evaluation of the accumulated amounts of the BCR and SAP97 by comparing the MFIs. Scale bar: 1.5 μm. (C and D) Accumulation of (C) the BCR and (D) SAP97 within the contact area of the cell with planar lipid bilayers containing either no antigen or NIP-H12 antigen for J558L cell lines expressing either wild-type B1-8-High mIgG-BCR (IgG-WT), mIgG-BCR with a mIgG tail composed of only the membrane-proximal 15 amino acids (IgG-N15), mIgG-BCR with the cytoplasmic tail of mIgM (IgG-CytoM), or wild-type mIgM-BCR (IgM-WT). The accumulation of the BCR and SAP97 into the contact interface is given as the percentage of their accumulation in IgG-WT cells placed on antigen-containing lipid bilayers. The data represent the mean ± SD of at least 20 cells from three independent experiments. Two-tailed t tests were performed for the statistical comparisons.

We used TIRF microscopy to quantify the accumulation of the BCR and SAP97 in the B cell immunological synapse (Fig. 3B). We imaged a series of J558L cell lines expressing either wild-type mIgG-BCR (IgG-WT), a mutant mIgG-BCR in which the mIgG tail was composed of only the membrane-proximal 15 amino acids (IgG-N15), a mutant mIgG-BCR that contained the cytoplasmic tail of mIgM (IgG-CytoM), or wild-type mIgM-BCR (IgM-WT). All four cell lines showed similar amounts of cell-surface BCR as measured by flow cytometric analysis of the binding of the antigen NP16-BSA to the BCR (Fig. S2B). When placed on membrane lipid bilayers that did not contain antigen, there was no obvious accumulation of the BCR at the interface of the B cell and the bilayer for any of the B cell lines (Fig. 3, B and C). In contrast, a portion of SAP97 was present at the interface of the B cell and the bilayer in similar amounts in all of the B cell lines (Fig. 3, B and D). When placed on antigen-containing bilayers, BCRs rapidly accumulated at the immunological synapse, and B cells expressing BCRs containing mIgG tails (either IgG-WT or IgG-N15) showed the accumulation of substantially increased amounts of BCR at the immunological synapse than did B cells expressing BCRs containing mIgM cytoplasmic tails (either IgM-WT or IgG-CytoM) (Fig. 3C), as previously reported (11). The amount of SAP97 in the immunological synapse was also substantially increased with BCR antigen engagement, but only in B cells expressing BCRs with mIgG cytoplasmic tails (IgG-WT) or BCRs with the mIgG membrane-proximal 15 amino acid tails (IgG-N15) (Fig. 3D). Collectively, these results provide evidence that SAP97 is associated with the plasma membrane in resting B cells and that it polarizes towards the region of contact between the cell and the bilayer in an antigen-independent manner. Upon BCR-antigen engagement and immunological synapse formation, SAP97 further accumulated in the immunological synapse in B cells expressing BCRs containing the membrane proximal region of the mIgG cytoplasmic tail.

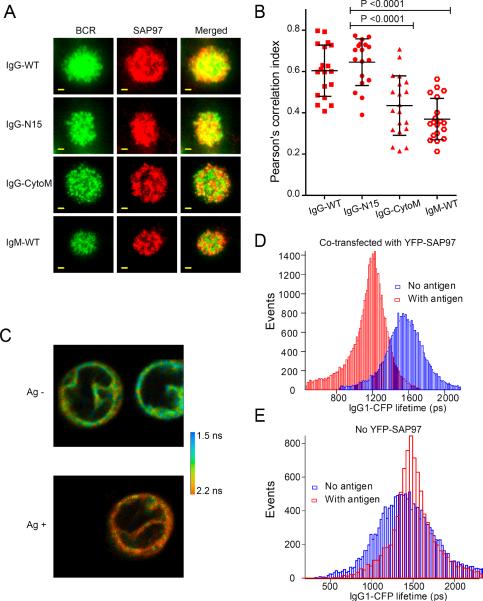

The observation that engagement of the IgG BCR with antigen resulted in increased accumulation of SAP97 in the immunological synapse raised the question of whether SAP97 and IgG BCRs were colocalized or possibly in contact in the immunological synapse. A Pearson's correlation analysis of two-color TIRF images showed a greater degree of colocalization of the IgG-WT BCR and IgG-N15 BCR with SAP97 than that of IgM-WT BCRs and IgG-CytoM BCRs with SAP97 (Fig. 4, A and B). To determine whether the IgG BCRs were in contact with SAP97, we used fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) combined with fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM), taking advantage of the feature that FRET measured by FLIM is independent of changes in donor or receptor concentration, excitation intensity, and other factors that limit sensitized fluorescence intensity–based measurements (16). To do so, we generated J558L cells that expressed yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-tagged SAP97 (YFPSAP97) and cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)-tagged mIgG (mIgG-CFP) by cotransfecting J558L B cells that stably expressed endogenous Igβ and Igλ light chain and a plasmid containing Igα with plasmids containing YFP-SAP97 and mIgG-CFP. The fluorescence lifetime of the CFP molecule was measured with a Becker-Hickl time-correlated single-photon counting device linked to a confocal fluorescence microscope equipped with a two-photon–pulsed laser. Upon antigen binding, the lifetime of CFP fluorescence was substantially reduced, indicating that BCR clustering and immunological synapse formation induced the close molecular proximity of YFP-SAP97 and mIgG-CFP (Fig. 4, C and D), supporting the conclusion that SAP97 binds to the tail of antigen-engaged IgG BCRs in living B cells. In control experiments, J558L B cells stably expressing Igβ, Igα and Igλ light chains that were transfected with plasmid encoding mIgG-CFP alone showed no substantial reduction in the lifetime of CFP fluorescence upon antigen engagement (Fig. 4E), indicating that the reduced fluorescence lifetime was not a result of quenching of clustered BCRs.

Fig. 4.

IgG BCRs and SAP97 show increased colocalization and close molecular proximity after antigen binding. (A to E) Pearson's correlation analyses of two-color (A and B) TIRF images and (C to E) FLIM analyses. (A) Two-color TIRF images of the BCR and SAP97 within the immunological synapse of J558L cells expressing BCRs containing IgG-WT, IgG-N15, IgG-CytoM, or IgM-WT. The cells were placed on planar lipid bilayers containing NIP-H12 for 10 min, fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with fluorescently tagged antibodies specific for the BCR or for SAP97. Scale bar: 1.5 μm. (B) Pearson's correlation indexes quantifying the colocalization of BCR and SAP97 within the immunological synapse in two-color TIRF images, as represented in (A). Each dot represents one cell analyzed in three independent experiments, and bars represent the mean ± SD. Two-tailed t tests were performed for the statistical comparisons. (C to E) To assess molecular proximity between YFP-SAP97 and mIgG-CFP, we measured the fluorescence lifetime of the CFP molecules with a Becker and Hickl time-correlated, single-photon counting device linked to a confocal fluorescence microscope equipped with a two-photon–pulsed laser. (C) Representative FLIM images from at least three independent experiments for J558L B cells stably expressing Igβ, Igα, and Igλ light chains that were cotransfected with plasmids encoding YFP-SAP97 and mIgG-CFP and placed on planar lipid bilayers containing no antigen (upper panel) or the antigen NIP-H12 (lower panel). The FLIM images were pseudo-colored to indicate the lifetime of CFP pixel by pixel. (D) Histogram plots of the CFP lifetime values from all of the pixels in the FLIM images. (E) Histogram plots of the CFP lifetime values from all of the pixels in FLIM images of J558 B cells expressing Igβ, Igα, Igλ, and mIgG-CFP.

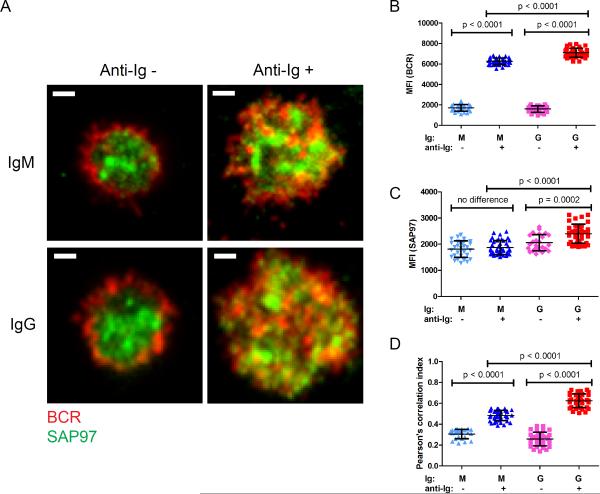

We also imaged the spatial distribution and colocalization of the BCR and SAP97 in primary human IgM+ and IgG+ B cells isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors by negative selection. We found that SAP97 protein was similarly abundant in human IgM+ and IgG+ B cells (Fig. S2C). We recently showed with F(ab')2 antibodies specific for human IgG and IgM (H + L) [F(ab')2 anti-Ig] or for human K light chain to crosslink the BCRs, that human IgG+ memory B cells are more robust than naïve B cells at each step in the initiation of B cell activation, including the accumulation of BCR in the synapse and the recruitment and activation of signaling-associated kinases (17). Here, we labeled B cells with fluorescently tagged Fab goat antibodies specific for human IgM or IgG and placed them for 10 min on fluid lipid bilayers that did or did not contain F(ab')2 anti-Ig to crosslink the BCRs. The cells were permeabilized and stained with fluorescently labeled anti-PAN-MAGUK mAb and imaged by TIRF microscopy (Fig. 5). In the absence of BCR crosslinking, little BCR, either IgM or IgG, accumulated at the interface of the B cells and the bilayer (Fig. 5, A and B). BCR crosslinking resulted in the accumulation of BCRs in the immunological synapse, with the IgG BCR substantially more abundant than the IgM BCR (Fig. 5, A and B), as shown previously (17). In the absence of BCR crosslinking, similar amounts of SAP97 were present at the interface between either IgM- and IgG- expressing cells and the bilayer (Fig. 5, A and C). BCR crosslinking induced an increase in the amount of SAP97 in the immunological synapse, but only in IgG-expressing B cells (Fig. 5C). In resting B cells, IgM BCRs and IgG BCRs showed low but similar extents of colocalization with SAP97 (Fig. 5D). Upon BCR crosslinking, the colocalization increased in both cases; however, the extent of colocalization of IgG BCRs with SAP97 was substantially greater than that of IgM BCRs (Fig. 5D). Thus, consistent with the earlier experiment with mouse J558L cell lines, in the context of human primary and isotype-switched memory B cells, SAP97 accumulated in the immunological synapse after crosslinking of IgG BCRs to a substantially greater degree and showed enhanced colocalization with IgG BCRs than with IgM BCRs.

Fig. 5.

The accumulation of SAP97 at the immunological synapse and its colocalization with IgG and IgM BCRs in human B cells. (A) Two-color TIRF images showing BCR and SAP97 within the immunological synapse of IgM+ and IgG+ human peripheral blood B cells. Cells were placed on planar lipid bilayers that did or did not contain anti-Ig to crosslink the BCRs for 10 min and then were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with fluorescently labeled antibodies specific for IgM or IgG and for SAP97. Scale bar: 1 μm. (B and C) MFIs of (B) the BCR and (C) SAP97 in the immunological synapse. (D) Pearson's correlation analysis for the colocalization of the BCR and SAP97 in the two-color TIRF images. Each dot represents one cell analyzed in two independent experiments, and bars represent the mean ± SD. Two-tailed t tests were performed for the statistical comparisons.

The enhanced initiation of IgG-BCR signaling is SAP97-dependent

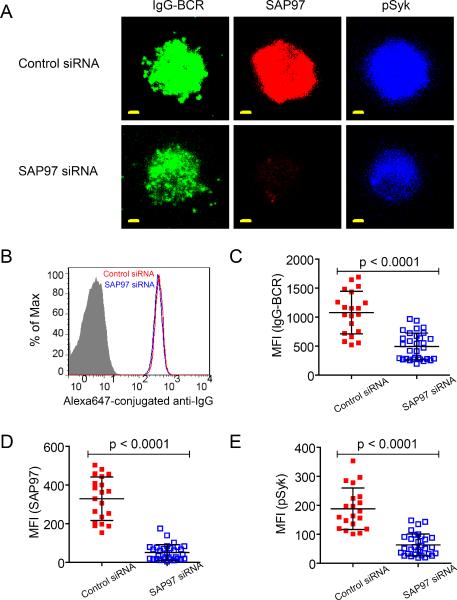

To determine whether SAP97 was necessary for the enhanced accumulation of IgG BCRs into the B cell immunological synapse, we knocked down SAP97 by short interfering RNA (siRNA) in IgG+ A20 II1.6 B cells. The abundance of SAP97 protein was decreased by >60% after transfection with a Thermal on-target plus Smartpool siRNA SAP97 construct as compared to that in cells transfected with a control, non-targeted siRNA construct (Fig. 6A and S3A), although both sets of cells maintained comparable amounts of surface IgG BCRs, as assessed by flow cytometry (Fig. 6B). Cells were placed on lipid bilayers containing F(ab')2 anti-IgG to crosslink the BCRs, and the accumulation of IgG BCRs and phosphorylated Syk (pSyk), one of the earliest kinases recruited to BCR microclusters, in the immunological synapse was imaged by TIRF microscopy. We observed a marked reduction in the amounts of IgG BCRs and pSyk recruited to the immunological synapse of B cells in which SAP97 was knocked down compared to those of the control cells (Fig. 6, C–E). Through correlation analyses, we determined that within the immunological synapse, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IgG BCRs was substantially positively correlated with the MFI of SAP97 (Fig. S3B).

Fig. 6.

The enhanced accumulation of IgG-BCRs in the immunological synapse and the increased recruitment of pSyk is SAP97-dependent. (A) Three-color TIRF images showing the accumulation of the BCR, SAP97, and pSyk within the immunological synapse of A20 II1.6 B cells expressing a control siRNA (control) or a SAP97-specific siRNA (SAP97 KD). B cells were placed on planar lipid bilayers containing F(ab')2 anti-IgG to crosslink the BCRs. Scale bar: 1.5 μm. (B) Cell-surface abundance of IgG BCRs in control and SAP97 KD A20 II1.6 cells as measured by flow cytometry with Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated mouse IgG-specific antibodies. (C to E) MFIs of (C) the BCR, (D) SAP97, and (E) pSyk within the immunological synapse. Each dot represents one cell analyzed in three independent experiments, and the bars represent the mean ± SD. Two-tailed t tests were performed for the statistical comparisons.

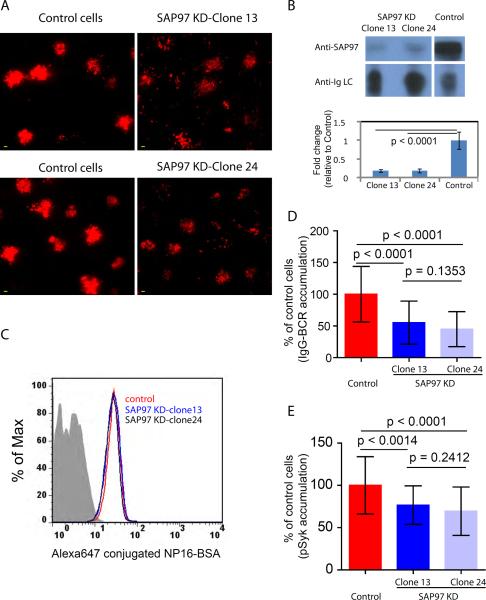

We obtained similar results investigating the SAP97-dependence of the enhanced accumulation of IgG-BCRs into the immunological synapse in J558L cells stably expressing the reconstructed IgG-BCR (IgG-WT-BCR) containing the B1-8-High heavy chain that binds to the small hapten, nitrophenol (NP) with high affinity (11). With a pSuper plasmid construct targeting SAP97 (18), we generated two stable sub-lines (clones 13 and 24) in which the abundance of SAP97 was decreased by over 80% compared to that of control cells expressing non-targeting, scrambled siRNAs (Fig. 7A, B). Both sub-lines showed equivalent binding to the antigen NP16-BSA by flow cytometry (Fig. 7C), indicating similar cell-surface abundances of the BCR. We found a marked impairment in the accumulation of IgG-BCRs and pSyk in the immunological synapse in clone 13 and 24 cells compared to that of control cells (Fig. 7, D and E).

Fig. 7.

The enhanced accumulation of IgG-BCRs in the immunological synapse is SAP97-dependent. (A) TIRF images show the BCR within the immunological synapse of J558L-IgGB1-8-High cells expressing a control siRNA and in cell lines stably expressing SAP97-specific siRNAs (SAP97 KD-Clone 13 and SAP97 KD-Clone 24). In the original 16-bit TIRF images, the display range was set from 0 to 500 to enable direct evaluation of the amount of the BCR by comparing the MFIs. Scale bar: 1.5 μm. (B) Western blotting analysis of the lysates of J558LIgG-B1-8-High control cells and SAP97 KD-Clone 13 and Clone 24 cells. Bar graph shows the statistical analysis of the fold change in SAP97 abundance compared to that of control cells and data are given as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. (C) Cell-surface abundance of the BCR was measured by flow cytometry with Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated NP16-BSA. (D and E) Accumulation of (D) IgG-BCR and (E) pSyk into the contact interface as a percentage of that in control cells placed on antigen-containing lipid bilayers. Data represent the mean ± SD of (D) 40 to 67 cells or (E) 29–43 cells from five independent experiments. Two-tailed t tests were performed for the statistical comparisons.

To ensure that the observed reduction in the accumulation of the BCR in cells with decreased abundance was specific to IgG BCRs, we initially transfected mouse CH27 B cells expressing phosphocholine (PC)-specific IgM BCRs with the Thermal on-target plus Smartpool siRNA SAP97 construct. However, we found that SAP97 abundance was reduced by only approximately 40% probably as a result of the relatively low transfection efficiency of CH27 cells. Thus, we used the pSuper plasmid construct, which specifically interferes with the translation of SAP97 mRNA (18). After puromycin screening and selection, we obtained a cell line in which SAP97 protein abundance was reduced by >70% compared to that in CH27 cells transfected with the control scrambled siRNA (Fig. S3A), although both lines maintained similar amounts of cell-surface BCR as assessed by flow cytometry (Fig. S3C). We imaged the accumulation of IgM BCRs, SAP97, and pSyk in the immunological synapse of SAP97-knockdown CH27 B cells (SAP97KD cells) placed on lipid bilayers containing the antigen BSA-PC10 and observed a substantial reduction in the amount of SAP97 that accumulated in the immunological synapse compared to that of the control cells (Fig.S3D). However, we did not observe a substantial difference in the antigen-induced accumulation of IgM BCRs and pSyk in the immunological synapse of control and SAP97KD cells (Fig. S3, E and F).

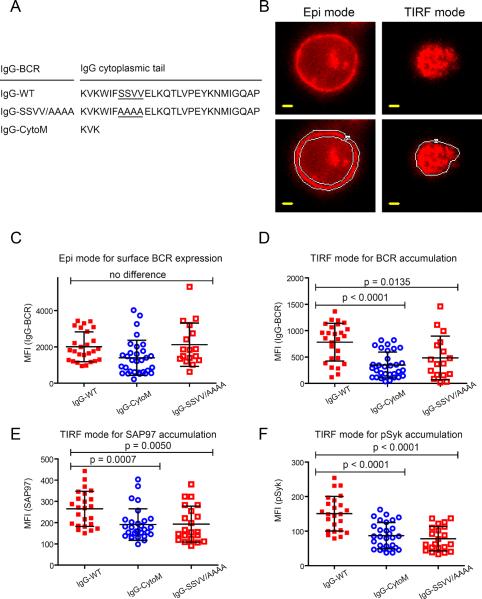

We next determined whether the SSVV motif in the mIgG cytoplasmic tail was required for the enhanced accumulation of IgG BCRs in the immunological synapse. To do so, we cotransfected J558 cells stably expressing endogenous Igβ and Igλ light chains and transfected with a plasmid expressing Igα-YFP with plasmids expressing wild-type IgG, mIgG with the SSVV tail motif mutated to AAAA (IgG-SSVV/AAAA), or the IgG CytoM construct (Fig. 8A). We first determined the amount of cell-surface BCR by epi-fluorescence imaging and subsequently switched to a TIRF mode to quantify the accumulation of IgG-BCRs in the immunological synapse (Fig. 8B). Although all three cell lines had similar amounts of BCRs on their surfaces (Fig. 8C), cells expressing either IgG-SSVV/AAAA BCRs or IgG-CytoM BCRs showed substantially reduced accumulation of SAP97 and pSyk in the immunological synapse compared to that of cells expressing IgG-WT BCRs (Fig. 8, D–F). Moreover, cells expressing the IgG-SSVV/AAAA BCRs and SAP97 showed significantly less co-localization of the BCRs and SAP97 as compared to cells expressing IgG-WT BCRs and SAP97 (P < 0.0001) (Fig. S4). These findings indicate a requirement for the evolutionarily conserved SSVV motif in the mIgG tail for the colocalization of the IgG BCR with SAP97 and the enhanced immunological synapse formation of cells expressing IgG BCRs.

Fig. 8.

The SSVV motif in the mIgG cytoplasmic tail is required for the enhanced accumulation of IgG BCRs into the immunological synapse. (A) The cytoplasmic tail sequences of B1-8-High IgG-BCR (mIgG-WT) and mutant forms of IgG-BCRs in which the SSVV motif was changed to AAAA (underlined) or the tail was truncated. (B) Images of the same representative cell illuminated first in an epifluorescence mode (left panels) and then in TIRF mode (right panels). The area of the BCR epifluorescence image from which the MFI of cell-surface BCR was acquired is outlined in white (left bottom panel). Similarly, the area of the BCR TIRF image from which the MFI of the BCRs in the immunological synapse was acquired is outlined in white (right bottom panel). Scale bar: 1.5 μm. (C to F) The MFIs of (C) surface BCRs, (D) accumulated BCRs, (E) SAP97, and (F) pSyk in the immunological synapse are given for cells expressing BCRs containing IgG-WT, IgG-CytoM, or IgG-SSVV/AAAA. Each dot represents one cell analyzed in three independent experiments, and the bars represent the mean ± SD. Two-tailed t tests were performed for the statistical comparisons.

SAP97 is required for signaling downstream of the BCR, including activation of p38

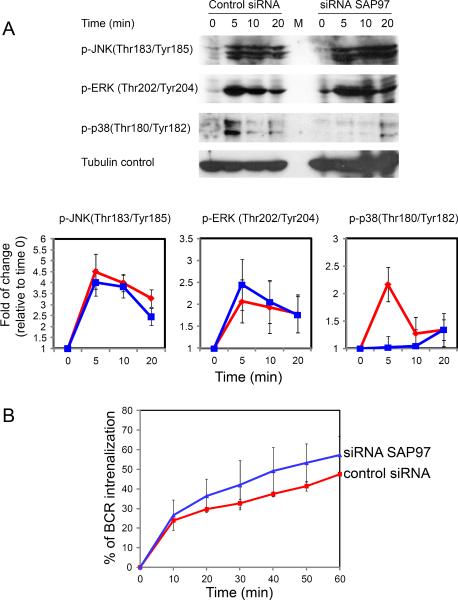

We also wanted to determine the effect of knocking down SAP97 on signaling downstream of the BCR. Because SAP97 is required for the activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in activated T cells (19), we determined the effect of SAP97 deficiency on MAPK activation after crosslinking of IgG BCRs. We activated A20 II1.6 SAP97 KD cells and control cells by crosslinking their BCRs with F(ab')2 anti-IgG F(ab')2 in solution. Knockdown of SAP97 did not affect the phosphorylation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) or extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK); however, we found that the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK at Thr180 and Tyr182, an indication of p38 MAPK activation, was substantially decreased in SAP97 KD cells compared to that in control cells (Fig. 9A). This finding is similar to that in T cells in which knock down of SAP97 blocked T cell receptor (TCR)-induced activation of p38 (19). In neuronal cells, members of the PSD-95 subfamily of MAGUK proteins regulate the activity of membrane proteins by influencing their surface abundance and endocytosis (13). Consequently, we also characterized the internalization of the BCR after crosslinking of the BCR in A20 II1.6 SAP97 KD cells and control cells. Knockdown of SAP97 accelerated the rate of crosslinking-induced BCR internalization (Fig. 9B), which suggested that SAP97 might function to retain BCR-antigen signaling complexes at the plasma membrane.

Fig. 9.

Knockdown of SAP97 substantially impairs activation of p38 MAPK. (A) Control or SAP97 KD A20II1.6 cells were activated by F(ab)2 anti-mouse IgM F(ab)2 (20 μg/ml) for the indicated times. Cells were lysed and lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting analysis for pJNK, pERK, and pp38. Bar graphs shows the fold change in protein accumulation over time and the statistical comparisons. Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. The red lines represent control cells and the blue lines represent SAP97 KD cells. (B) Internalization of IgG-BCRs in SAP97 KD versus control A20 II1.6 B cells. Cells were incubated with biotin-conjugated F(ab')2 anti-mouse IgG F(ab')2, washed, and incubated at 37°C for the indicated times. The amounts of cell-surface IgG-BCR at each time point were measured by flow cytometry with PE-conjugated streptavidin. Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments.

Discussion

Here, we provide evidence that SAP97 associates with the membrane-proximal region of the cytoplasmic tail of mIgG, and that through this interaction it acts to enhance the initiation of early signaling and immunological synapse formation in class switched IgG+ B cells, which led to enhanced signaling. These results place isotype switching at a critical tipping point in B cell activation that ensures the enhanced initiation of IgG+ B cell responses through SAP97. The importance of the interaction of the mIgG tail and SAP97 for the biology of IgG+ B cells is reflected in the degree of conservation of the membrane-proximal region of the IgG tail and the PDZ-binding motif among all known mammalian mIgGs and lizard mIgY-BCRs. The functions of SAP97 and other members of the family of MAGUK scaffold proteins are best understood in neuronal cells, in which SAP97 plays an essential role in controlling the density, localization, and clustering of glutamate receptors and ion channels at the synapse, and by doing so controls the size and transmission strength of excitatory synapses (12, 13, 20). Our results suggest a similar role for SAP97 in the immunological synapse of IgG+ memory B cells. In experiments with knockout mice, several SAP family members have been demonstrated to be of key importance in the establishment of learning and memory (13, 21–24). The observation that SAP97 also functions in immunological memory adds to the long-standing analogies drawn between neurological and immunological synapses and memory.

The markedly impaired phenotype in antigen recall responses of transgenic mice lacking the cytoplasmic tail of mIgG strongly suggested the possibility that the mIgG cytoplasmic tail directly connected to the B cell signaling apparatus to enhance B cell activation (5–7). Wienands and colleagues (8) provided the first evidence for such an association by showing that a conserved ITT motif present in both mIgG and mIgE is phosphorylated upon BCR crosslinking, which results in the recruitment of the adapter protein Grb2 and enhanced Ca2+ responses and subsequent increased B cell proliferation. The results presented here, that the ITT motif was not required for the enhanced ability of IgG BCRs to cluster and initiate signaling, places the function of the ITT motif as an important amplifier downstream of the initiating events in BCR signaling.

We provided evidence from FLIM that the association of SAP97 and the mIgG tail was greatly enhanced upon antigen-induced clustering of IgG BCRs, which raised the question of how the interaction between SAP97 and IgG BCRs is restricted to clustered BCRs. The binding of PDZ-binding motifs to PDZ domains is weak in the low micromolar range (1 to 10 μM) when measured by solution-based methods (25–27). Thus, individual IgG BCRs may not be able to stably associate with SAP97, but when clustered by antigen, the avidity of the interactions of the clustered tails with the PDZ domains of SAP97 may be sufficient to stabilize the interaction. Alternatively, the mIgG tail may not be available for binding to SAP97 in resting B cells. Consistent with this possibility, we previously showed with FRET microscopy that the IgG BCR tail and the Igα and Igβ tails initially come into close molecular proximity upon antigen binding to the BCR but then rapidly come apart to an “open” state (28). The antigen-induced “open” form of the BCR may enable the binding of SAP97. It is also possible that SAP97 is brought into close molecular proximity with the clustered IgG BCRs by a mechanism similar to that which brings the first kinase in the BCR signaling cascade, Lyn, into proximity with clustered BCRs. We previously showed that BCR clustering perturbs its local lipid microenvironment, congealing raft lipids around the BCR cluster (29). Lyn, which is myristoylated and palmitoylated and associates with lipid rafts, is first brought into proximity with clustered BCRs transiently through lipid-lipid interactions, and then through protein-protein interactions between Lyn and the Igα and Igβ tails, Lyn becomes stably associated with the BCR. SAP97 is palmitoylated at its N-terminus and is predicted to associate with the saturated lipids in lipid rafts in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane (30, 31); thus, it may similarly be brought into close molecular proximity with clustered BCRs. Such a mechanism for the association between SAP97 and IgG BCRs may also explain why IgM BCRs that perturb the local lipid environment but lack the ability to bind to SAP97 do not stably associate with SAP97.

We do not yet know the mechanisms by which SAP97 contributes to the enhanced initiation of signaling. SAP97, acting as a scaffold, could enhance the stability of early BCR oligomers, driving these towards the growth of larger clusters. Consistent with this possibility, we previously observed that a portion of IgG BCRs, but not IgM BCRs, were recruited to growing BCR clusters in an antigen-ndependent fashion (11). Even the weak interaction between SAP97 and IgG BCRs could serve to amplify signaling. SAP97 interacts with the Src-family kinase, Lck, and with Zap70 in T cells (32–34), suggesting that SAP97 might serve to concentrate early kinases around the clustered BCR. Once engaged, SAP97 could also enhance the activation of IgG+ B cells by enhancing the coordination of BCR microclusters with the cytoskeleton. Studies have highlighted the substantial role of cortical actin and ezrin-radixin-moesin (ERM) in regulating both tonic and antigen-driven BCR signaling (35–37). It has been reported in other cell types that ezrin interacts with SAP97 through its N-terminal FERM domain (38, 39). It is possible that through SAP97, the IgG BCRs more efficiently interact with the cytoskeleton to promote signaling.

Here, we also provided evidence that activation of p38 MAPK by IgG BCRs was substantially decreased in cells in which SAP97 was knocked down. This result mirrors reported results showing that crosslinking of TCRs on antigen-experienced T cells, but not naïve T cells, results in the association of SAP97 and p38 and the phosphorylation of p38 (40). Regulatory T cells (Tregs) were also recently reported to require SAP97 for the phosphorylation of p38 at Thr180 and Tyr182 and for the activation of nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 (NFATc1), which is necessary for Treg function (41). Earlier results showed that SAP97 mutants that cannot bind to p38 fail to trigger downstream signaling in T cells (19). Together, these results indicated an important function of SAP97 in the activation of p38 in memory B cells and antigen-experienced T cells, as well as in Tregs. The findings presented here indicate that once having switched from expressing mIgM BCRs to expressing mIgG BCRs, the B cell is endowed with an enhanced ability to initiate and transduce signaling that may enable IgG+ B cells to outcompete IgM+ B cells in immune responses. The discovery that the binding of the conserved IgG tail to SAP97 is required for enhanced signaling may provide new targets for therapies to block enhanced BCR activation in autoimmune disease and in some B cell tumors.

Materials and Methods

Cells, antibodies, antigens, plasmids, and transfections

J558L, A20II1.6, and CH27 mouse cell lines were maintained as previously reported (14, 15). B cells were purified from PBMCs from healthy, anonymous, adult blood bank donors (collected for research purposes at the NIH Department of Transfusion Medicine under an NIH IRB approved protocol with informed consent) by negative selection magnetic cell separation with a human B cell isolation kit II (Miltenyi). Anti-PAN MAGUK antibody (Clone K28/86) and anti-SAP97 antibody (Clone K64/15) were purchased from the UC Davis/NIH NeuroMab Facility. Anti-human SAP97 antibody (Clone 2D11) was purchased from Santa Cruz. Anti-phospho-ZAP70 (pY319)-Syk (pY352) antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling. Isotype-matched mouse IgG1 antibody was purchased from Invitrogen. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibodies against mouse or rabbit IgG were purchased from GE. HRP-conjugated anti-GST antibody was purchased from Sigma. HRP-conjugated anti-mouse light chain antibody was purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Purified unconjugated Fab goat anti-mouse Fcμ5 IgM (anti-IgM), biotin-conjugated F(ab')2 goat anti-mouse or anti-human IgM + IgG F(ab')2, and goat anti-mouse or anti-human IgG Fc were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch. Fab anti-mouse or anti-human IgG Fc (anti-IgG) was prepared with a Fab micro preparation kit (Pierce) as previously reported (11). Antibodies against IgM and IgG were conjugated to Alexa fluorophores with Alexa Fluor mAb labeling kits (Invitrogen) as previously reported (15). F(ab')2 anti-IgG F(ab')2 were biotinylated with an EZ-Link Biotinylation kit (Pierce). Antibodies against the following targets were purchased from Cell Signaling: pERK, phospho-p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) (197G2); pJNK, phospho-SAPK/JNK (Thr183/Tyr185); pp38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182). Anti-γ-tubulin antibody was purchased from Sigma. Anti-actin antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz (C-11). HRP-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG was purchased from Santa Cruz, and ECL anti-mouse IgG was from GE. Real-time PCR primers specific for Dlg1 (SAP97), Dlg2 (PSD93), Dlg3 (SAP102), Dlg4 (PSD-95), and internal control rRNA were purchased from Qiagen. Plasmids expressing μ-B1-8 or γ1-B1-8 fused at the C-terminus with CFP and plasmid expressing Igα fused at the C-terminus with YFP through the linker peptide GGGAAS were constructed as previously described (28). Plasmids expressing γ1-WT, γ1-Cyto N15 γ1 and γ1-Cyto μ were constructed as previously reported (11). Plasmid expressing SAP97 fused at the N-terminus with YFP and the p-Super plasmid expressing shRNA specific for SAP97 (p-Super-puromycin-SAP97) were constructed as previously reported (18) and were provided as gifts from R. T. Javier (Baylor College of Medicine, USA). The sequence of the hairpin used in scrambled control plasmids was reported in the literature (42). Plasmids expressing full-length SAP97 or the SH3-GUK domain of SAP97 fused at the N-terminus with GST (GST-SAP97-FL or GST-SAP97-SH3-GUK) were constructed as previously reported (19) and were provided as gifts by M. Carrie Miceli (UCLA, USA). Based on the GST-SAP-FL plasmid, a plasmid expressing the PDZ123 of SAP97 fused at the N-terminus with GST (GST-SAP97-PDZ123) was generated by standard subcloning. ON-TARGET plus SMART pool against mouse SAP97 (Cat. No., L-042037-00) and non-targeting control (Cat. No. D-001810-10-05) were purchased from Thermal Dharmacon. NIP conjugated to the peptide ASTGKTASACTSGASSTGSHis12 (NIP1-His12), N15 SSVV peptide conjugated at the N-terminus with biotin (Biotin-GG-KVKWIFSSVVELKQT), and the biotin-conjugated mutant form N15 GGGG (Biotin-GG-KVKWIFGGGGELKQT) were purchased from Anaspec and California Peptides. All peptides were purified by HPLC and verified by mass spectrometry with >90% purity. Bovine serum albumin (BSA)-conjugated 1:16 with phosphoryl-choline (PC16-BSA) was purchased from Biosearch Technologies. Transient transfections were performed with Amaxa transfection kits, and the transfected B cells were imaged after overnight culture.

Preparation of antigen-containing planar fluid lipid bilayers

Planar fluid lipid bilayers were prepared as described previously (11). Ni-NTA–containing lipid bilayers were prepared by mixing 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) and 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-Glycero-3-[N(5-Amino-1-Carboxypentyl) Imino-diacetic Acid]-Succinyl (Nickel Salt) (DOGS-Ni-NTA; Avanti Polar Lipids) in a mixture of 90% DOPC and 10% DOGS-Ni-NTA. Biotin-containing planar lipid bilayers were prepared with DOPC and 1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-Glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-cap-biotin (DOPE-cap-biotin, Avanti Polar Lipids) in a mixture of 99% DOPC and 1% DOPE-cap-biotin. Ni-NTA–containing or biotin-containing unilamellar vesicles were formed by sonication of the mixed lipids and were clarified by ultracentrifugation and filtering as described previously (15). Glass coverslips were cleaned with Nanostrip (Cyantek) and dried. Lipid bilayers were prepared from 0.1 mM lipid unilamellar vesicles on freshly cleaned glass coverslips. NIP1-His12 hapten antigen was attached to the Ni-NTA–containing lipid bilayer by incubating NIP1-His12 with the bilayer for 20 min at room temperature. After washing, the antigen-containing lipid bilayers were used in TIRF imaging. The amount of antigen bound to the bilayer was quantified as described previously (15). Incubating the planar lipid bilayers with 10 nM NIP1-His12 peptide solutions resulted in bilayers containing approximately 25 molecules per μm2, as previously reported (15). For biotin-containing lipid bilayers, biotinylated ICAM-1 and PC16-BSA or biotin-conjugated F(ab')2 goat anti-mouse or anti-human IgM + IgG F(ab')2 were attached through streptavidin as reported previously (29). Briefly, 50 nM streptavidin was incubated with biotin-containing lipid bilayers for 10 min. After washing, 10 nM biotinylated ICAM-1 and 10 nM PC16-BSA or 10 nM biotin-conjugated F(ab')2 goat anti-mouse or anti-human IgM + IgG F(ab')2 were bound to the planar lipid bilayer.

Imaging BCR, SAP97, and pSyk microclusters by two-color TIRF microscopy

Cells were placed on planar fluid lipid bilayers lacking or containing antigens. TIRF images were acquired at 37°C on a heated stage by an Olympus IX-81 microscope supported by a TIRF port, CascadeII 512 × 512 electron-multiplying CCD camera (Roper Scientific), and an Olympus 100 × 1.45 N.A. and Zeiss 100 × 1.4 N.A. objective lens. The acquisition was controlled by Metamorph software (Molecular Devices). The exposure time was 100 ms unless specially indicated. Three types of lasers were used: a 442 nm solid state laser; a 488 nm and 514 nm argon gas laser, and a 568 nm and 647 nm red krypton and argon gas laser. When indicated, B cells were labeled with Fab anti-Ig as specified in each figure, washed twice, and placed on lipid bilayers. B cells were then fixed 10 min after being placed on antigen-containing lipid bilayers. The fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then incubated in blocking buffer. The cells were incubated with rabbit antibody against p-ZAP70 (pY319)-Syk (pY352), washed three times, and then incubated with Alexa 488– or Alexa 647–conjugated F(ab')2 goat antibodies specific for rabbit IgG (Invitrogen). BCR and pSyk images were acquired by two-color TIRF microscopy through multidimensional acquisition mode controlled by Metamorph software. YFP, Alexa Fluor 568, and Alexa Fluor 647 were excited by the 488 nm, 568 nm, and 647 nm lasers, respectively. YFP, Alexa Fluor 568, and Alexa Fluor 647 emission fluorescence were collected by 550 ± 40 ET BP, 605 ± 40 BP, and 665 LP emission filters through a 488 and 568 and 647 dichroic wheel filter cube. Intracellular staining for SAP97 with Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated Fab anti-SAP97 antibody was by the procedure described for the intracellular staining of pSyk. TIRF images were background subtracted with Image Pro Plus. The MFIs of BCR, SAP97, and pSyk microclusters within the contact area were measured with Image J.

Immunoprecipitations, purification of GST fusion proteins, and ELISA

Peptide-based immunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (8), with some modifications obtained from protocols available online (http://www.protocol-online.org/cgibin/prot/view_cache.cgi?ID=4089. Briefly, biotinylated N15SSVV or control biotinylated N15GGGG peptides were conjugated to streptavidin beads. B cells (107 cells) were lysed in lysis buffer, and clear supernatants were incubated with the peptide-streptavidin-beads overnight at 4°C. The beads were then washed and boiled with sample buffer to elute the associated proteins. The eluted samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE for subsequent silver staining or Western blotting analysis. The induction of GST and SAP97 fusion protein production by IPTG in Bl21 E. coli cells and the further purification of GST fusion proteins were performed by standard protocols. The ELISA assay was also performed according to standard protocols. Briefly, N15SSVV or N15GGGG peptides were coated onto the wells of an ELISA assay plate overnight at 4°C. The wells were then blocked and incubated with various GST-SAP97 fusion proteins for 1 hour at room temperature. The plates were then washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-GST antibody and subjected to optical density measurement at 450 nm.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total cellular RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed with the Superscript III First Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Cycling conditions were 10 min at 95°C, followed by 40 repeats of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Analysis was performed by the sequence detection software supplied with the instrument (Eppendorf Realplex 2). Real-time PCR primers targeting Dlg1 (SAP97), Dlg2 (PSD93), Dlg3 (SAP102), Dlg4 (PSD-95), TFRC, and rRNA were purchased from Qiagen. Sequences are unavailable because of proprietary licensing, but the primers yielded bands between 90 and 168 base pairs in length. TFRC and rRNA served as internal controls in our experiments.

FLIM analysis

Sensitized FRET measurements based on the intensities of donor or acceptor emission fluorescence are difficult to apply to inter-molecular FRET experiments because the emission fluorescence intensity can often be affected by changes in the concentrations of donors or receptors or in excitation intensity (16). FLIM-linked FRET experiments can avoid these problems. FLIM is a measurement of the rate of decay of the donor emission, which will not be affected by donor concentration and excitation laser intensity. Instead, the donor fluorescence life time is substantially influenced by the FRET energy transferred from the donor to the acceptor. In our experiments, a femtosecond two-photon laser (~ 120fs, Coherent) was used to provide the 890 nm excitation laser source for CFP in confocal fluorescence microscopy (710, Zeiss). The laser line was conditioned and steered to the confocal scanner and a Zeiss 63× 1.4 NA-oil immersion objective lens by the microscopy system manufacture. Fluorescence life images were captured with a time-correlated single-photon counting device (Becker & Hickl). Live cell images were initially chosen and focused by the standard procedure for CFP and YFP channels through the ZOIN software package from Zeiss, and then the FLIM images were recorded with the standard Becker and Hickl SPCM software package (version 9). The FLIM images were then analyzed with Becker and Hickl SPCM software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Javier (Baylor College of Medicine), S. Vandel Pol (Virginia University), and A. I. Cuenda Mendez (National Center for Biotechnology, Spain) for providing experimental materials. We also thank S. Russell (Swinburne University of Technology), S. Bolland, P. Sun, T. Jin (LIG-NIAID-NIH), and M. F. Flajnik (University of Maryland) for helpful discussions and suggestions.

Funding: This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. This work was also supported by the funds from Tsinghua University and the Center for Life Sciences.

Footnotes

Author contributions: S.K.P. and W.L. designed and supervised the experiments; W.L., E.C., Z.W., X.Z., Y.G., A.D., E.H., and L.Z. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; J.C., G.S., M.G.J., C.M., J.L., L.A., W.S., and J.B. contributed experimental materials or provided helpful suggestions; and S.K.P. and W.L. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References and Notes

- 1.McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Antigen-specific memory B cell development. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:487–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reth M. Antigen receptors on B lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:97–121. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaisho T, Schwenk F, Rajewsky K. The roles of gamma 1 heavy chain membrane expression and cytoplasmic tail in IgG1 responses. Science. 1997;276:412–415. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5311.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin SW, Goodnow CC. Burst-enhancing role of the IgG membrane tail as a molecular determinant of memory. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:182–188. doi: 10.1038/ni752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horikawa K, Martin SW, Pogue SL, Silver K, Peng K, Takatsu K, Goodnow CC. Enhancement and suppression of signaling by the conserved tail of IgG memory-type B cell antigen receptors. J Exp Med. 2007;204:759–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waisman A, Kraus M, Seagal J, Ghosh S, Melamed D, Song J, Sasaki Y, Classen S, Lutz C, Brombacher F, Nitschke L, Rajewsky K. IgG1 B cell receptor signaling is inhibited by CD22 and promotes the development of B cells whose survival is less dependent on Ig alpha/beta. J Exp Med. 2007;204:747–758. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakabayashi C, Adachi T, Wienands J, Tsubata T. A distinct signaling pathway used by the IgG-containing B cell antigen receptor. Science. 2002;298:2392–2395. doi: 10.1126/science.1076963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engels N, Konig LM, Heemann C, Lutz J, Tsubata T, Griep S, Schrader V, Wienands J. Recruitment of the cytoplasmic adaptor Grb2 to surface IgG and IgE provides antigen receptor-intrinsic costimulation to class-switched B cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1018–1025. doi: 10.1038/ni.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harwood NE, Batista FD. Early events in B cell activation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:185–210. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pierce S, Liu W. The tipping points in the initiation of B cell signalling: how small changes make big differences. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010;10:767–777. doi: 10.1038/nri2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu W, Meckel T, Tolar P, Sohn HW, Pierce SK. Intrinsic properties of immunoglobulin IgG1 isotype-switched B cell receptors promote microclustering and the initiation of signaling. Immunity. 2010;32:778–789. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheng M, Sala C. PDZ domains and the organization of supramolecular complexes. Annual review of neuroscience. 2001;24:1–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim E, Sheng M. PDZ domain proteins of synapses. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2004;5:771–781. doi: 10.1038/nrn1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu W, Won Sohn H, Tolar P, Meckel T, Pierce SK. Antigen-induced oligomerization of the B cell receptor is an early target of FcγRIIB inhibition. J. Immunol. 2010;184:1977–1989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu W, Meckel T, Tolar P, Sohn HW, Pierce SK. Antigen affinity discrimination is an intrinsic function of the B cell receptor. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:1095–1111. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallrabe H, Periasamy A. Imaging protein molecules using FRET and FLIM microscopy. Current opinion in biotechnology. 2005;16:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davey AM, Pierce SK. Intrinsic Differences in the Initiation of B Cell Receptor Signaling Favor Responses of Human IgG+ Memory B Cells over IgM+ Naive B Cells. J Immunol. 2012;188:3332–3341. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frese KK, Latorre IJ, Chung SH, Caruana G, Bernstein A, Jones SN, Donehower LA, Justice MJ, Garner CC, Javier RT. Oncogenic function for the Dlg1 mammalian homolog of the Drosophila discs-large tumor suppressor. The EMBO journal. 2006;25:1406–1417. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Round JL, Humphries LA, Tomassian T, Mittelstadt P, Zhang M, Miceli MC. Scaffold protein Dlgh1 coordinates alternative p38 kinase activation, directing T cell receptor signals toward NFAT but not NF-kappaB transcription factors. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:154–161. doi: 10.1038/ni1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elias GM, Nicoll RA. Synaptic trafficking of glutamate receptors by MAGUK scaffolding proteins. Trends in cell biology. 2007;17:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zanni G, van Esch H, Bensalem A, Saillour Y, Poirier K, Castelnau L, Ropers HH, de Brouwer AP, Laumonnier F, Fryns JP, Chelly J. A novel mutation in the DLG3 gene encoding the synapse-associated protein 102 (SAP102) causes non-syndromic mental retardation. Neurogenetics. 2010;11:251–255. doi: 10.1007/s10048-009-0224-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarpey P, Parnau J, Blow M, Woffendin H, Bignell G, Cox C, Cox J, Davies H, Edkins S, Holden S, Korny A, Mallya U, Moon J, O'Meara S, Parker A, Stephens P, Stevens C, Teague J, Donnelly A, Mangelsdorf M, Mulley J, Partington M, Turner G, Stevenson R, Schwartz C, Young I, Easton D, Bobrow M, Futreal PA, Stratton MR, Gecz J, Wooster R, Raymond FL. Mutations in the DLG3 gene cause nonsyndromic X-linked mental retardation. American journal of human genetics. 2004;75:318–324. doi: 10.1086/422703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Migaud M, Charlesworth P, Dempster M, Webster LC, Watabe AM, Makhinson M, He Y, Ramsay MF, Morris RG, Morrison JH, O'Dell TJ, Grant SG. Enhanced long-term potentiation and impaired learning in mice with mutant postsynaptic density-95 protein. Nature. 1998;396:433–439. doi: 10.1038/24790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yao WD, Gainetdinov RR, Arbuckle MI, Sotnikova TD, Cyr M, Beaulieu JM, Torres GE, Grant SG, Caron MG. Identification of PSD-95 as a regulator of dopamine-mediated synaptic and behavioral plasticity. Neuron. 2004;41:625–638. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris BZ, Lim WA. Mechanism and role of PDZ domains in signaling complex assembly. Journal of cell science. 2001;114:3219–3231. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.18.3219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niethammer M, Valtschanoff JG, Kapoor TM, Allison DW, Weinberg RJ, Craig AM, Sheng M. CRIPT, a novel postsynaptic protein that binds to the third PDZ domain of PSD-95/SAP90. Neuron. 1998;20:693–707. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall RA, Ostedgaard LS, Premont RT, Blitzer JT, Rahman N, Welsh MJ, Lefkowitz RJ. A C-terminal motif found in the beta2-adrenergic receptor, P2Y1 receptor and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator determines binding to the Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor family of PDZ proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:8496–8501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tolar P, Sohn HW, Pierce SK. The initiation of antigen-induced B cell antigen receptor signaling viewed in living cells by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Nature immunology. 2005;6:1168–1176. doi: 10.1038/ni1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sohn HW, Tolar P, Pierce SK. Membrane heterogeneities in the formation of B cell receptor-Lyn kinase microclusters and the immune synapse. The Journal of cell biology. 2008;182:367–379. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200802007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waites CL, Specht CG, Hartel K, Leal-Ortiz S, Genoux D, Li D, Drisdel RC, Jeyifous O, Cheyne JE, Green WN, Montgomery JM, Garner CC. Synaptic SAP97 isoforms regulate AMPA receptor dynamics and access to presynaptic glutamate. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:4332–4345. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4431-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou W, Zhang L, Guoxiang X, Mojsilovic-Petrovic J, Takamaya K, Sattler R, Huganir R, Kalb R. GluR1 controls dendrite growth through its binding partner, SAP97. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:10220–10233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3434-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xavier R, Rabizadeh S, Ishiguro K, Andre N, Ortiz JB, Wachtel H, Morris DG, Lopez-Ilasaca M, Shaw AC, Swat W, Seed B. Discs large (Dlg1) complexes in lymphocyte activation. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:173–178. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miceli MC, Round JL, Tomassian T, Zhang M, Patel V, Schoenberger SP. Dlgh1 coordinates actin polymerization, synaptic T cell receptor and lipid raft aggregation, and effector function in T cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;201:419–430. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludford-Menting MJ, Oliaro J, Sacirbegovic F, Cheah ET, Pedersen N, Thomas SJ, Pasam A, Iazzolino R, Dow LE, Waterhouse NJ, Murphy A, Ellis S, Smyth MJ, Kershaw MH, Darcy PK, Humbert PO, Russell SM. A network of PDZ-containing proteins regulates T cell polarity and morphology during migration and immunological synapse formation. Immunity. 2005;22:737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Treanor B, Depoil D, Bruckbauer A, Batista FD. Dynamic cortical actin remodeling by ERM proteins controls BCR microcluster organization and integrity. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1055–1068. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Treanor B, Depoil D, Gonzalez-Granja A, Barral P, Weber M, Dushek O, Bruckbauer A, Batista FD. The membrane skeleton controls diffusion dynamics and signaling through the B cell receptor. Immunity. 2010;32:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parameswaran N, Matsui K, Gupta N. Conformational switching in ezrin regulates morphological and cytoskeletal changes required for B cell chemotaxis. J Immunol. 2011;186:4088–4097. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lue RA, Brandin E, Chan EP, Branton D. Two independent domains of hDlg are sufficient for subcellular targeting: the PDZ1-2 conformational unit and an alternatively spliced domain. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1125–1137. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.4.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lasserre R, Charrin S, Cuche C, Danckaert A, Thoulouze MI, de Chaumont F, Duong T, Perrault N, Varin-Blank N, Olivo-Marin JC, Etienne-Manneville S, Arpin M, Di Bartolo V, Alcover A. Ezrin tunes T-cell activation by controlling Dlg1 and microtubule positioning at the immunological synapse. The EMBO journal. 2010;29:2301–2314. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adachi K, Davis MM. T-cell receptor ligation induces distinct signaling pathways in naive vs. antigen-experienced T cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:1549–1554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017340108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zanin-Zhorov A, Lin J, Scher J, Kumari S, Blair D, Hippen KL, Blazar BR, Abramson SB, Lafaille JJ, Dustin ML. Scaffold protein Disc large homolog 1 is required for T-cell receptor-induced activation of regulatory T-cell function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:1625–1630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110120109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.