Abstract

Evidence regarding a functional serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) signaling system in bone has generated considerable recent interest. The specific biochemical nature of serotoninergic pathways and their direct and/or indirect effects on bone metabolism are still unclear.

Clinical evidence supports an effect of serotonin and altered serotonin signaling on bone metabolism. Serotonin is involved in the pathophysiology of depression, and therefore studies of depression and antidepressant treatments (as modulators of the serotonin system) are relevant with regard to bone outcomes. Studies of the effect of depression on bone mineral density (BMD) and fractures have been mixed. Studies of associations between antidepressant use and BMD and/or fractures are more consistent. SSRIs have been associated with lower BMD and increased rates of bone loss, as well as increased rates of fracture after accounting for falls. These studies are limited by confounding because depression is potentially associated with both the outcome of interest (BMD, fracture) and the exposure (SSRIs).

With mounting evidence for an effect on bone, this review considers the question of causality and whether selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors should be considered among those medications that contribute to bone loss, and therefore prompt clinicians to evaluate BMD proactively. Future research will be required to confirm the serotoninergic effects on bone and the biochemical pathways involved, and to identify clinical implications for treatment based on this novel pathway.

Keywords: bone, depression, serotonin, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, screening, epidemiology, neurotransmitter

Introduction

A functional signaling system in bone for the centrally acting neurotransmitter serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT) was identified by two groups in 2001.[1, 2] Evidence regarding this system has accumulated slowly, but the recent publication from Yadav et al (2008) has provided an unexpected twist and stimulated great interest in a novel mechanism for regulating bone mass.[3-5] [6] This mechanism involves gut-derived serotonin as the mediator for LRP-5 action on bone cells.[3] However, the specific biochemical nature of serotoninergic pathways and their direct and/or indirect effects on bone metabolism are still unclear. In this issue, Warden et al have reviewed in detail the pre-clinical evidence for an effect of serotonin and altered serotonin signaling on bone metabolism.[7] This review will expand on those findings, bringing to light the current knowledge about clinical findings of serotonin and bone, particularly as they relate to individuals using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and provide perspective for clinical practice: that is, screening, case finding and population health.

Clinical evidence for a relationship between SSRI use and bone health

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, are a class of medications that selectively and potently block the serotonin transporter (5-HTT). Serotonin transporters are located in the central nervous system (CNS) and in the periphery, including bone. SSRIs appear to effect CNS and bone 5-HTT with similar potency.[1] In the CNS, these medications serve to effectively increase the extra-cellular levels of serotonin thereby relieving symptoms of depression. SSRIs are first-line therapy and widely used for treatment of major depressive disorder as well as several other psychiatric conditions including post-traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and some non-psychiatric conditions such as chronic pain, fibromyalgia, and post-menopausal vasomotor symptoms (night sweats, hot flashes).

Several studies in varied populations have demonstrated an effect of SSRIs on bone mineral density (BMD). Cross-sectional studies support an association between SSRIs and lower BMD in men[8] [9] and women.[9-11] Adjusted differences in BMD between SSRI users and non-users range from 2.4 to 6.2% across anatomic sites.[8-10] More important for demonstrating causal associations, longitudinal studies have shown that SSRI users have at least 1.6 fold greater declines in BMD compared to those not taking SSRIs.[11] Contrasting results from and show no association between antidepressant use and BMD among men and women age 17 years and older using data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), [12] or among postmenopausal women participating in the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) Observational Study.[12, 13]

The use of population-based cohorts to demonstrate the effect on BMD has been important for several reasons. First, these studies are large enough to account for various other confounding variables in the analysis of SSRI use and BMD. Second, they tend to enroll fairly healthy adults, so there are potentially fewer unmeasured variables contributing to declines in BMD. Third, they demonstrate a direct effect on bone density (as opposed to falls), an aspect that is important when considering the mechanism for increased fracture risk among SSRI users. Most of these studies have attempted to adjust for depression and/or depressive symptoms using various measures. Williams et al demonstrated an association between SSRI use and lower BMD among women (mean age 54.2 years) from the Geelong Osteoporosis Study with either past or current depression according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria determined by a structured clinical interview.[10] By successfully and rigorously defining current/past depression and excluding women who may have taken SSRIs for another indication, they were able to demonstrate the association between SSRIs and BMD independent of depression.

An association between antidepressants and increased risk of fracture is supported by case-control studies using large administrative datasets from Denmark,[14] Manitoba Canada,[15] Michigan USA,[16] and Ontario, Canada.[17] Vestergaard demonstrated increased odds of hip and any fracture for antidepressant users, and specifically for SSRIs rather than TCAs (adjusted OR 1.15-1.40 for all antidepressants; 95% CI 0.99-1.30 for TCAs [NS] and 1.08-1.62 for SSRIs across dosages).[14] This is important because TCA's as a class are less potent inhibitors of the serotonin transporter than SSRIs.[18]Likewise, Bolton demonstrated increased odds of hip fracture for SSRI users (OR 1.45 for SSRI users, 95% CI 1.32-1.59).[14, 15] While database studies can be problematic because of the inability to control for unmeasured variables (i.e. depressive symptoms, history of falls), they add to the growing body of literature that support a contribution by SSRIs to fracture risk.

Among several prospective cohort studies, fracture risk is also increased for those taking SSRIs compared to those who do not use antidepressants. Men from the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) cohort have an overall increased in risk for non-spine fracture.[19, 20] Women from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) taking anti-depressants had elevated risk for fracture (the relative risk is significant for TCAs and hip fracture only, but point estimates suggest that SSRIs and TCAs both increase non-spine fracture risk).[21] In the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study (CaMOS) cohort, older men and women taking SSRIs had higher rates of fracture over 5 years compared to non-users (hazard ratio 2.1; 95% confidence interval 1.3-3.4).[9] Among men and women in Rotterdam age 55 and older, the risk was increased 2-fold (HR 2.35, 95% CI 1.32-1.48) for nonvertebral fracture. From the Women's Health Initiative, antidepressant use among postmenopausal women were associated with increased risk of any fracture and non-clinical vertebral fracture, but not hip or wrist.[13]

Decisions about causal relationships in clinical research

Acceptance of causality requires a complementary set of studies that address several aspects of the associations in question. First and most important are the consistency and strength of the associations demonstrated.[22] In the case of SSRIs, associations have been demonstrated in several distinct populations, using various study designs and with bone density, bone loss or fractures as outcomes. The associations are consistent after adjustment for confounding variables such as age, body mass index, lifestyle factors (alcohol, tobacco use), family history and personal history of fractures.

Second, a demonstrated dose-response supports causal inference.[22] Ideally, studies that imply causation will demonstrate dose and duration effects (increasing risk for the negative outcome with increasing dose and/or duration of medication). For SSRIs, three studies have examined dose with varied results.[9, 14, 15] Among users of all antidepressants, Vestergaard demonstrated progressive increases in relative risk for any fracture, hip fracture, and spine fracture as the antidepressant dose increased across levels of defined daily dose (DDD): from <0.15 DDD;0.15-0.75 DDD; and ≥0.75 DDD. In sub-analyses, increasing daily doses of TCAs showed progressive, but non-significant, increases in the RR of fracture for any fracture, Colles’ fracture, and spine fracture but not for hip fracture; SSRIs showed increases in the RR of fracture across doses for all categories of fracture, but results were significant only for hip fracture. Other antidepressants showed no dose-response. [14] Bolton also demonstrated a dose effect for SSRIs using the Manitoba dataset. Odds ratios for fracture among men and women over age 50 using SSRIs increased significantly across tertiles of SSRI dose (p<0.05).[15] The CaMOS study observed a dose-dependent effect for SSRIs: 1.5 fold increase in risk of fragility fracture for each unit increase in the daily dose of SSRI.[9] Other studies have not found a linear increase in risk with increasing dose.[23]

Addressing the question of whether duration of SSRI use increases risk, Richards demonstrated higher fracture risk among men and women using SSRIs at baseline and 5 years later. Other studies suggest higher risk within the first 15 days of treatment.[24] Ziere evaluated both dose and duration in the Rotterdam cohort, but had small numbers and did not show a progressive effect with either increasing dose or increasing duration of SSRI treatment.[23] In the UK General Practice Research Database, Hubbard found that OR for fracture were highest for those with a first SSRI prescription within 0-14 days prior to the fracture, compared with those 15-42 and ≥43 days before the fracture.[24] One explanation for this finding, particularly with regard to fracture, is that SSRIs contribute to fracture through falls early in the course of treatment, and through a direct bone mechanism later in the course of treatment.

Overall, medication adherence is difficult to estimate without direct pharmacy records. Thus, some database studies that utilize pharmacy records are better suited to critical evaluation of dose and duration effects than standard cohort studies. However, as with all database studies, they often lack the ability to control for all necessary confounders.

A final consideration for causality is biologic plausibility: the existence of a potential mechanism whereby the proposed effects can be achieved within our current understanding of the biology of the system being studied.[22] The groundwork for biologic plausibility for an SSRI effect on bone has been defined by several studies that confirm the existence of functional serotonin transporters and receptors,[1, 2], and demonstrate the bone effects of inactivation of the serotonin transporter both in vitro and in vivo.[25-28] Yadav et al. posit that LRP-5 exhibits its effect on bone through gut-derived serotonin.[3] Although these findings are provocative, questions remain concerning how LRP5 regulates serotonin synthesis in the gut, the biochemical pathways used by serotonin in bone cells, and what feedback loop is used to inform enterochromaffin cells in the gut about the status of skeletal health.[7]

Limitations of current studies on SSRIs effect on bone

Complicating the interpretation of current SSRI studies in terms of causality are several methodologic issues, inherent to epidemiologic studies. One is the issue of confounding by indication, which can exist if a disease and the treatment both have potential to be associated with the outcome of interest.[29] In this case, depression has also been associated with low bone density in some [30-37] but not all[13, 38-42] studies;[43] mixed results have also been observed for an association between depression and falls[39, 42, 44-46] and depression and fractures.[13, 21, 33, 39, 40, 42, 47, 48] Within a particular study it can be difficult to determine whether the disease state (depression) or the treatment (SSRIs) is responsible for the effects seen.[49, 50] Most studies of SSRIs have used a measure of depressive symptoms (SF-12 or SF-36, Center for Epidemiologic Studies 10-item Depression scale, Beck Depression Inventory, Geriatric Depression Scale, and others). One study by Williams et al included only women with a lifetime history of past/current depression according to DSM-IV diagnostic criteria evaluated with a structured clinical interview.[10] This method of rigorously defining depression and restricting the analytic cohort to a group that is more homogenous (i.e. removing women who may have been taking an SSRI for another indication) is another method of demonstrating an association between SSRI use and BMD independent of depression.

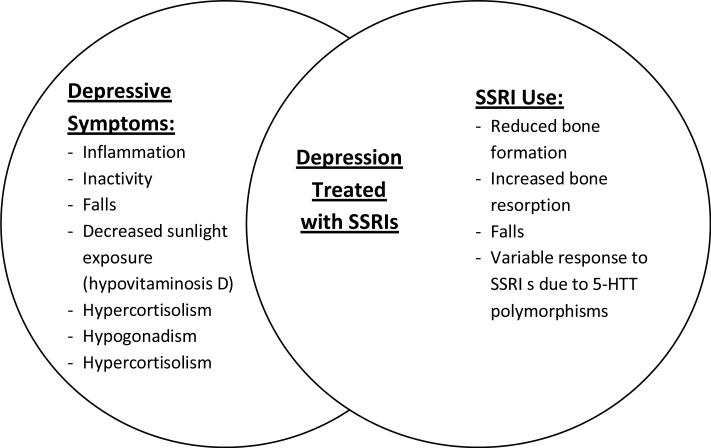

Thus, depression and SSRIs have the potential to impact bone independently through distinct mechanistic pathways that convey particular risks (Figure). For instance, SSRIs could influence bone through reduced bone formation, increased bone resorption or both, or through falls. The skeletal response to SSRIs could be modulated by genetic differences in the serotonin transporter. Depression could influence bone through inflammation, physical inactivity, falls, decreased outdoor exposure (and therefore lower vitamin D levels), hypercortisolism, or hypogonadism. Theoretically, when a person has persistent depressive symptoms and is taking an SSRI, he/she could be at higher risk based on overlapping pathways. Those with depressive symptoms that are in remission after treatment with an SSRI, and those using SSRIs for non-depressive illness, may be at lower risk.

Figure.

Depressive symptoms and SSRI treatment may have distinct but potentially overlapping mechanisms for effects on bone loss and fracture. SSRI users may have persistent symptoms of depression, may be in remission from depression, or may be using SSRIs for a non-depressive condition.

The relationship between SSRIs and fall risk is not clear. On one hand, several studies show SSRI use is associated with an increase in fall risk, and that this risk is higher than for other types of antidepressants, namely TCAs.[3, 44, 51-53] Conversely, other studies show SSRIs confer equivalent or lower fall risk to TCAs[45, 46] Undermining the interpretation of these studies is the failure to clarify the dose of TCA medication, the indication, and the frailty of the individual patient. In geriatric practice, TCAs are generally avoided because of their side effect profile, and potential for drug-drug interactions.[24] If used at all, they are often given in doses well below those required to treat depression. In addition, SSRIs vary with respect to their potency for inhibiting the serotonin transporter. Whether this variation among medications within a class is associated with variation in fall risk has not been studied. An Italian study of patients admitted to home care showed no increased risk for falls with any antidepressant or with SSRIs. This study had a particularly rigorous assessment of medications, self-reported falls within past 90 days, and was adjusted for depressive symptoms as assessed by the Minimum Data Set for Home Care (MDS-HC).[54] Resolution of remaining questions about SSRIs and their contribution to bone loss, falls and fractures will require randomized controlled trials with careful measurement of depression and depressive symptoms.

Implications for screening and population health

Findings that suggest a detrimental effect of SSRI use on bone imply that clinicians should be vigilant about detection of bone disease in patients who have perturbation of the serotonin system (whether by depression or by SSRIs), and should perhaps consider earlier testing of BMD by dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for patients on these medications as they do for patients taking corticosteroids,[55-57] depomedroxyprogesterone, or anti-epileptic medications, among others. Indeed similar questions have arisen recently bone health of people taking proton pump inhibitors[58-61] and thiazolidinediones.[62-64]

Is it time to recommend bone density testing for patients on SSRIs? Before considering that question, it is worth defining and clarifying the definition of screening. Epidemiologists, primary care physicians and specialists may all have different definitions for “screening.” The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations contribute to screening guidelines across a variety of clinical disciplines. The USPSTF considers screening the process of detecting disease in those who are otherwise felt to be at average risk. In contrast, case finding is the detection of disease when one suspects it based on clinical risk factors or symptoms. Ideally, a screening test should detect disease before it is symptomatic, at a stage where effective treatments are available, and acceptable to patients; the disease must be one that has significant impact and whose clinical course can be altered by available treatments.[65] Using this approach, the USPSTF has considered and made recommendations on screening for osteoporosis in 2002,[66] and it is currently revising those guidelines to provide updated recommendations in 2009.

Implementing recommendations for or against screening may take into account the varied risk according to specific population groups. The overall rate and the relative age and gender distributions of SSRI use with in the population would impact resource utilization and therefore the cost effectiveness of a universal program. Because depression and SSRI use are common among postmenopausal women, this group may be at higher risk than younger or male populations. Likewise, the severity and duration of depressive symptoms and/or treatment may be important considerations.

The question then becomes whether we should consider SSRI users as a population at average risk for bone loss and fractures, in which case screening guidelines would be no different than for non-SSRI users. Or should SSRI use now be considered a secondary cause of osteoporosis, prompting a case finding approach for detection of osteoporosis akin to what is done for glucocorticoid users? Recently, the NOF issued revised guidelines that suggest that early diagnostic testing and treatment should be considered for those patients with lifestyle characteristics that suggest increased risk for fracture.[57] Pertinent to this discussion, depression is included on the list of medical conditions that confer increased risk for both osteoporosis/fractures and falls; psychotropic medications are included with medications that cause oversedation as a medical risk factors for falls. SSRIs are not included on the list of medications that cause or contribute to osteoporosis and fractures.

In our opinion, the evidence now seems sufficient to consider adding SSRIs to the list of medications that contribute to osteoporosis. This would imply that clinicians consider bone density testing for people on SSRIs, or those on SSRIs with certain additional risk factors, for their risk of fracture. Potential recommendations could vary by population, taking in to account age, gender, duration and severity of depression, length of SSRI treatments and other concurrent risk factors. At this stage, it seems appropriate to expect that everyone taking SSRIs have at least some discussion about bone health with their provider. Measurement and replacement of vitamin D, supplementation with calcium, and recommendations for exercise also seem reasonable. It is too early to suggest that all SSRI users be tested with DXA (in the absence of other risk factors), but the question should be addressed with trials of screening to know whether screening with DXA improves outcomes over usual care—usual care in this case could include measuring/replacing vitamin D, supplementing with calcium and recommending exercise as described above, or doing nothing. Additional research should inform the risk-benefit discussions between patients and providers about medications. Studies of bone outcomes among younger (children and adolescents) SSRI users are lacking yet necessary, as there is some evidence for a potential detrimental effect.[68]

Conclusion

This is an exciting time for bone biologists, clinicians, and all those doing translational research. The neuroendocrine aspects of bone metabolism are only beginning to be understood. Efforts to confirm the serotoninergic effects on bone, the biochemical pathways utilized, and the feedback loops involved among bone, gut and perhaps brain are underway. Additional work is needed on the potential role of estrogen as a modulator of the SSRI response through its effect on the serotonin transporter, and the implications of such a potential interaction on post-menopausal women. An important clinical implication of the work on serotonin signaling through LRP-5 is the potential for identifying novel therapeutic targets. These questions should continue to fuel the recent surge in interest in neuroendocrine regulation of the skeleton.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Haney is supported by a K23 award (051926) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Citations

- 1.Bliziotes M, et al. Neurotransmitter Action in Osteoblasts: Expression of a Functional System for Serotonin Receptor Activation and Reuptake. Bone. 2001;29(5):477–486. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westbroek I, et al. Expression of Serotonin Receptors in Bone. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(31):28961–28968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yadav VK, et al. Lrp5 Controls Bone Formation by Inhibiting Serotonin Synthesis in the Duodenum. Cell. 2008;135(5):825–837. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen CJ. Serotonin Rising -- The Bone, Brain, Bowel Connection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(10):957–959. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0810058. 10.1056/NEJMp0810058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosen CJ. Breaking into bone biology: serotonin's secrets. 2009;15(2):145–146. doi: 10.1038/nm0209-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Long F. When the gut talks to bone. Cell. 2008;135:795–796. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warden SJ, et al. The emerging role of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) in the skeleton and its mediation of the skeletal effects of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP-5). Bone. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.06.029. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haney EM, et al. Association of Low Bone Mineral Density With Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Use by Older Men. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1246–1251. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Richards JB, et al. The impact of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors on the risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(2):188–94. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams LJ, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use and bone mineral density in women with a history of depression. International Clinical Pscyhopharmacology. 2008;23:84–87. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f2b3bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diem S, et al. Use of Antidepressants and Rates of Hip Bone Loss in Older Women: The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(12):1240–1245. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinjo M, et al. Bone mineral density in subjects using central nervous system-active medications. Am J Med. 2005;118(12):1414e7–1414.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spangler L, et al. Depressive symptoms, bone loss, and fractures in postmenopausal women. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Feb 20; doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0525-0. (e-pub ahead of print; COI 10.1007/x11606-008-0525-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Anxiolytics, sedatives, antidepressants, neuroleptics and the risk of fracture. Osteoporosis International. 2006;17:807. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0065-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolton JM, et al. Fracture risk from psychotropic medications: a population-based analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;28(4):384–391. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31817d5943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray WA, et al. Psychotropic drug use and the risk of hip fracture. New England Journal of Medicine. 1987;316(7):363–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198702123160702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu B, et al. Use of Selective Serotonin-reuptake Inhibitors or Tricyclic Antidepressants and Risk of Hip Fractures in Elderly People. Lancet. 1998;351:1303–07. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)09528-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richelson E. Pharmacology of antidepressants. May Clinic Proceedings. 2001;76:511–527. doi: 10.4065/76.5.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haney EM, et al. SSRI use is associated with increased risk of fracture among older men. JBMR. 2007;22(supple 1):s45. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis CE, et al. Predictors of non-spine fracture in elderly men: The MrOS Study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 2007;22(2):211–219. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ensrud KE, et al. Central nervous system active medications and risk for fractures in older women. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:949–957. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.8.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hulley SB, et al. Designing Clinical Research. 2nd Edition Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziere G, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibiting antidepressants are associated with an increased risk of nonvertebral fractures. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;28(411-417) doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31817e0ecb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hubbard R, et al. Exposure to Tricyclic and Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressants and the Risk of Hip Fracture. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(1):77–84. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bliziotes MM, et al. Serotonin Transporter and Receptor Expression in Osteocytic MLO-Y4 Cells. Bone. 2006;39(6):1313–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warden SJ, et al. Neural regulation of bone and the skeletal effects of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine). Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2005;242(1-2):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warden SJ, et al. Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) transporter inhibition causes bone loss in adult mice independently of estrogen deficiency. Menopause. 2008;15(6):1176–1183. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318173566b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Battaglino R, et al. Serotonin regulates osteoclast differentiation through its transporter. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19(9):1420–1431. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Psaty B, et al. Assessment and Control for Confounding by Indication in Observational Studies. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1997;47(6):749–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coelho R, et al. Bone mineral density and depression: A community study in women. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46(1):29–35. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diem SJ, et al. Depressive symptoms and rates of bone loss at the hip in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:824–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robbins J, et al. The Association of Bone Mineral Density and Depression in an Older Population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:732–736. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Silverman SL, et al. Prevalence of depressive symptoms in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density and/or prevalent vertebral fracture: Results from the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) study. Journal of Rheumatology. 2007;34(1):140–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mussolino ME, Jonas BS, Looker AC. Depression and bone mineral density in young adults: Results from NHANES III. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66:533–537. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000132873.50734.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wong SYS, et al. Depression and bone mineral density: is there a relationship in elderly Asian men? Results from Mr. Os (Hong Kong). Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:610–5. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1730-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacka FN, et al. Depression and bone mineral density in a community sample of perimenopausal women: Geelong Osteoporosis Study. Menopause. 2005;12(1):88–91. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200512010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eskandari F, et al. Low bone mass in premenopausal women with depression. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(21):2329–2336. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whooley MA, et al. Depressive Symptoms and Bone Mineral Density in Older Men. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2004;17(2):88–92. doi: 10.1177/0891988704264537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whooley MA, et al. Depression, Falls, and Risk of Fracture in Older Women. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:484–490. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sogaard AJ, et al. Long-term mental distress, bone mineral density and non-vertebral fractures. The Tromso Study. Osteoporosis International. 2005;16(8):887–897. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1784-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reginster JY, et al. Depressive vulnerability is not an independent risk factor for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1999;33:133–137. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitson HE, et al. Depressive symptomatology and fracture risk in commnity-dwelling older men and women. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2008;20:585–592. doi: 10.1007/bf03324888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mezuk B, Eaton WW, Golden SH. Depression and osteoporosis: epidemiology and potential mediating pathways. Osteoporosis International. 2008;19(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0449-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kerse N, et al. Falls, depression, and antidepressants in later life: a large primary care appraisal. PlosONE. 2008;3(6):e2423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thapa PB, et al. Antidepressants and the Risk of Falls among Nursing Home Residents. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(13):875–882. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809243391303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ensrud KE, et al. Central nervous system-active medications and risk for falls in older women. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2002;50:1629–1637. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tolea MI, et al. Depressive symptoms as a risk factor for osteoporosis and fractures in older Mexican American women. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:315–22. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0242-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Forsen L, et al. Mental distress and risk of hip fracture. Do broken hearts lead to broken bones? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1999;53:343–347. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.6.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams LJ, et al. Depression and bone metabolism. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2009;78:16–25. doi: 10.1159/000162297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haney EM, Warden SJ. Skeletal effects of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) transporter inhibition: Evidence from clinical studies. Journal of Musculoskeletal & Neuronal Interactions. 2008;8(2):133–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sterke CS, et al. The influence of drug use on fall incidents among nursing home residents: a systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics. 2008;20(05):890–910. doi: 10.1017/S104161020800714X. doi:10.1017/S104161020800714X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hartikainen S, Lonnroos E, Louhivuori K. Medication as a risk factor for falls: Critical systematic review. Journal of Gerontology: MEDICAL SCIENCES. 2007;62A(10):1172–1181. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.10.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.French DD, et al. Drugs and falls in community-dwelling older people: a national veterans study. Clinical Therapeutics. 2006;28(4):619–630. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Landi F, et al. Psychotropic Medications and Risk for Falls Among Community-Dwelling Frail Older People: An Observational Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(5):622–626. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Canalis E, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: pathophysiology and therapy. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1319–1328. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0394-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Canalis E, et al. Perspectives on glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Bone. 2004;34(4):593–598. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.National Osteoporosis Foundation . Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu EW, et al. Acid-suppressive medications and risk of bone loss and fracture in older adults. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008;83:251–259. doi: 10.1007/s00223-008-9170-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang Y-Z, et al. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006;296(24):2947–2953. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.24.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Targownik LE, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2008;179(4):319–326. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Richards JB, Goltzman D. Proton pump inhibitors: balancing the benefits and potential fracture risks. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2008;179(4):306–307. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vestergaard P. Bone metabolism in type 2 diabetes and role of thiazolidinediones. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2009;16:125–131. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e328325d155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Solomon DH, et al. A Cohort Study of Thiazolidinediones and Fractures in Older Adults With Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009:jc.2008–2157. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2157. 10.1210/jc.2008-2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lipscombe LL. Thiazolidinediones: Do harms outweigh benefits?. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2009;180(1):16–17. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harris RP, et al. Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;3(suppl 1):21–35. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00261-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(6):526–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-6-200209170-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weintrob N, et al. Decreased Growth During Therapy With Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(7):696–701. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.7.696. 10.1001/archpedi.156.7.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]