Abstract

Dual process models of addiction suggest that the influence of alcohol-related cognition might be dependent on the level of executive functioning. This study investigated if the interaction between implicit and explicit alcohol-related cognitions and working memory capacity predicted alcohol use after one month in at-risk youth. Implicit and explicit alcohol-related cognitions were assessed in 88 Dutch at-risk adolescents ranging in age from 14 to 20 (51 males) with an adapted version of the Implicit Association Test (IAT) and an expectancy questionnaire. Working memory capacity was assessed using the computer-based version of the Self-Ordered Pointing Task (SOPT). Alcohol use and alcohol-related problems were measured at baseline and after one month with self-report questionnaires. The hierarchical regression analysis showed that both the interaction between implicit positive-arousal cognitions and working memory capacity and the interaction between explicit positive-arousal cognitions and working memory capacity predicted unique variance in alcohol use after one month. Implicit positive-arousal cognitions predicted alcohol use after one month more strongly in students with lower levels of working memory capacity, whereas explicit positive-arousal cognitions predicted one-month follow-up alcohol use more strongly in students with higher levels of working memory capacity. This could imply that different intervention methods could be effective for different subgroups of at-risk youth.

Keywords: implicit cognition, explicit cognition, executive functioning, IAT, adolescence, alcohol use

1. Introduction

Several dual process models predict that both more reflective explicit and more impulsive implicit cognitive processes influence behavior (e.g. Fazio and Towles-Schwen, 1999; Kahneman, 2003; Strack and Deutsch, 2004). Implicit cognitions represent more automatic underlying motivational processes, whereas explicit cognitions are related to more deliberate thought processes (Greenwald and Banaji, 1995; Kahneman, 2003). Recently, there has been increased interest in the role of implicit cognitions in the development of addictive behaviors. These implicit alcohol-related cognitions represent individual differences in memory associations between alcohol-related cues (e.g. presence of alcohol), outcomes (e.g. excitement), and behaviors (e.g. drinking). These associations if strengthened over time become motivationally significant and guide behavior relatively automatically (Stacy, 1997). The mesolimbic dopamine reward system has been associated with these relatively automatic motivational processes, which are believed to play an important role in the development of addictive behavior (e.g. Bechara, 2005; Kalivas and Volkow, 2005). Implicit cognitions have been shown to predict unique variance in current and prospective alcohol use after controlling for explicit cognitions (e.g. Jajodia and Earleywine, 2003; Palfai and Wood, 2001; Stacy, 1997; Thush and Wiers, 2007; Wiers et al., 2002).

A second assumption of several dual process models is that the influence of implicit processes on subsequent behavior is moderated by explicit processes if motivation and the opportunity to do so are present (e.g. Fazio and Towles-Schwen, 1999; Kahneman, 2003; Strack and Deutsch, 2004). Indeed, neurobiological addiction research has shown that the prefrontal cortex and associated areas are involved in more reflective decision making and in the moderation of impulses (e.g. Bechara, 2005; Kalivas and Volkow, 2005; Wilson et al., 2004). Dual process models of addiction specifically predict that the influence of implicit appetitive cognitions on subsequent addictive behavior might be dependent on the level of executive functioning (e.g. Stacy et al., 2004; Wiers et al, 2007).

Executive functions can be described as a set of cognitive skills relevant to goal-directed behavior involving different abilities such as shifting, updating and inhibition (Miyake et al., 2000). Working memory capacity has been proposed to be a central construct that possibly binds these different but related executive functions (Kane and Engle, 2002). The relationship between executive functions and alcohol use has been shown to be bidirectional. Poorer executive functioning can be considered a risk factor for developing addictive behaviors such as drinking alcohol (e.g. Finn and Hall, 2004; Peterson et al., 1992; Tapert et al., 2002). Additionally, alcohol abuse has been shown to negatively affect the maturation of brain regions (e.g., DeBellis et al., 2000), to impair neuropsychological functioning (e.g., Brown et al., 2000) and to alter processing on executive functioning tasks (Tapert et al., 2004). During adolescence, when executive functions and associated brain regions are still developing, alcohol induced damage in the prefrontal cortex can lead to inhibitory and attentional control problems which, in turn, may influence continued alcohol use (Crews et al., 2000; Wiers et al, 2007). This bidirectional nature might be more apparent in at-risk adolescents. It is also possible that these at-risk adolescents may start with poorer executive functions and begin drinking at earlier ages, which, in turn, further interferes with their ability to control their drinking behavior.

Prior research has suggested that the influence of implicit automatic processes, on other behaviors, indeed, is moderated by executive control (e.g. Feldman-Barrett et al., 2004; Payne, 2005), as has also been proposed for addictive behaviors (e.g. Stacy et al., 2004; Wiers et al, 2007). Grenard et al. (manuscript under review) evaluated the interaction between working memory capacity and spontaneous memory associations assessed with word association tasks (an alternative indirect assessment of implicit cognitive processes) among at-risk youth and found evidence that drug-relevant associations were stronger predictors of alcohol and cigarette use among those with lower working memory capacity than among those with higher working memory capacity. Finn and Hall (2004) proposed that two mechanisms might be responsible for the moderating influence of executive functioning on the implicit processes-behavior relationship. First, low activating capacity of working memory makes it difficult to shift attention away from highly activated stimuli to stimuli that are less salient. Second, short term positive associations with behavior tend to be highly activated (salient), whereas the long term negative associations with behavior are usually weakly activated. Consequently, in high-risk situations, such as being at a party where alcohol is readily available, an individual needs to be able to switch to less immediately salient goals and attend to them - such as the intention to not drink large amounts of alcohol or binge drink - while distracting salient information in the current high-risk situation is more automatically activated (e.g., the urge to feel intoxicated or to give in to peer pressure). This relationship between executive functioning and behavior suggests that adolescents who are less able to actively manage less salient but adaptive goals when faced with distracting information are more likely to let their behavior be influenced by distracting salient information that is triggered in the current situation (e.g. Stacy et al., 2004; Wiers et al, 2007).

Conversely, research suggests that explicit positive expectancies might be moderated by executive functioning in the opposite direction. In addiction research, alcohol expectancies have been shown to be good predictors of concurrent and, to a lesser extent, prospective alcohol use (e.g., Goldman and Darkes, 2004; Jones et al., 2001; Sher et al., 1996; Stacy et al., 1991). Tapert and colleagues (2003) showed that explicit positive alcohol expectancies predicted alcohol use in substance use disorder adolescents with good verbal skills, but not in substance use disorder adolescents with poor verbal skills. Verbal skills are needed for developing internal language-based reasoning skills (Luria, 1961) and predictive of positive alcohol expectancies (Deckel et al., 1995). Verbal skill tasks such as the verbal fluency task are commonly regarded as measuring frontal-lobe processing (Deckel et al., 1995) and verbal executive functioning (Tapert et al., 2003). Tapert et al. (2003) concluded that positive alcohol expectancies require encoding and deep processing in order for them to affect decision making and thus drinking. However, other studies have found that adolescents who show good executive functioning (e.g. good inhibitory neural processing) generally had fewer positive and more negative outcome alcohol expectancies (Anderson et al., 2005) and that verbal skills sometimes are also negatively predictive of positive expectancies (Deckel et al., 1995). Thus, there are still some questions about whether positive alcohol expectancies might be moderated by executive functioning in the opposite direction than implicit appetitive associations.

Hence, from a dual process perspective we hypothesized that the influence of implicit appetitive associations (both positive-arousal and positive-sedation) on subsequent drinking behavior is stronger in adolescents with low working memory capacity than in adolescents with high working memory capacity. Conversely, the influence of explicit positive-arousal alcohol-related processes on subsequent drinking behavior is hypothesized to be stronger in adolescents with high working memory capacity compared with adolescents with low working memory capacity. The current study investigated these two interactions between alcohol-related cognition and working memory capacity in the prediction of alcohol use after one month in at-risk youth.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

A total of 88 Dutch adolescents (51 male) in the age range of 14 to 20 (mean age = 16.34, SD = 1.34) were recruited from four low-level vocational schools (Thush et al., in press). Based on a Dutch national health survey among high school adolescents, low-level vocational schools showed the highest prevalence of alcohol and drug use as well as behavioral problems. Hence, at the group level, these students are considered to be at risk for developing substance-related problems. Participants self-reported drinking an average of 10.85 Dutch standard alcoholic drinks on a weekend day (SD = 10.30) and an average of 2.72 Dutch standard alcoholic drinks on a weekday (SD = 6.18). (A standard alcohol serving in the Netherlands contains somewhat less alcohol than a standard American standard glass: 10 vs. 14 g). Of the 88 participants 68 (77.27 %) indicated having one or more binge drinking episodes (5 or more Dutch standard alcoholic drinks on one occasion) in the past 2 weeks.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Alcohol use

Alcohol use was assessed with a Dutch version of the alcohol use questionnaires as described in Ames et al. (2007). Self-report questionnaires have been proven to be reliable and valid if participant sobriety and confidentiality of data are assured (Sobell and Sobell, 1990). Both requirements were fulfilled in this study. Participants were asked how many times they used various drugs in the last month and in their lifetime on an 11-item rating scale (ranging from ‘never used’ to ‘91-100+ times’). Participants respond to a list of specific drugs (i.e. alcohol, marijuana, ecstasy, etc.) or more general drug categories (i.e. hallucinogens, stimulants, other club drugs, etc.). Additionally, participants indicated how many Dutch standard glasses of alcohol they consumed at the last weekend day and weekday they drank. In addition, they indicated on a 3-point Likert scale how many standard glasses of alcohol they consumed on each day of the past week (ranging from ‘no drinks’ to ‘more than 5 drinks’), and they indicated on a 6-point Likert scale on how many occasions they drank five Dutch standard glasses of alcohol or more in the past two weeks (ranging from ‘I do not drink’ to ‘seven times or more’). Lastly, participants indicated on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from ‘I do not drink’ to ‘very intoxicated’) how intoxicated they were the last time they drank in the past 12 months.

2.2.2 Alcohol-Related Problems

An index of alcohol-related problems was assessed using an adapted version of the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI; White and Labouvie, 1989). We used the 18-item version of the RAPI which correlated .99 with the original 23-items version (White and Labouvie, 2000). Participants were asked to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from ‘never’ to ‘daily’) how many times they experienced certain problems within the last months because of their alcohol use. An example of an item is: “Not able to do your homework or study for a test”. The items were summed to create an index of alcohol-related problems (Cronbach’s alpha =.87).

2.2.3 Implicit Association Test

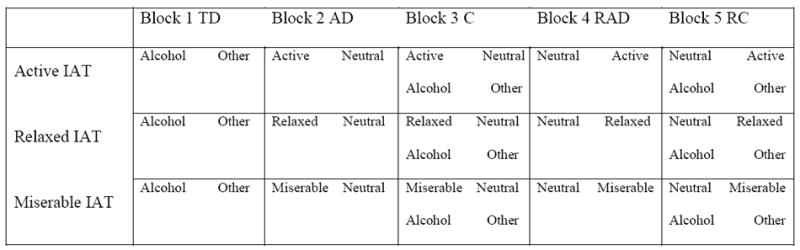

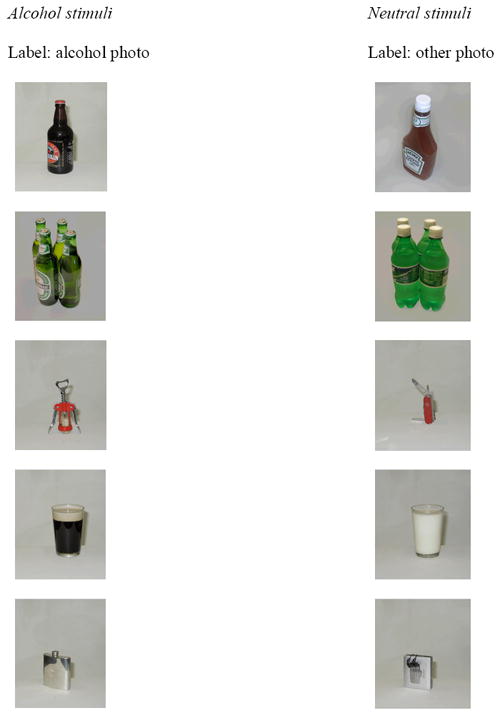

In the IAT, participants categorize stimuli into four categories as quickly as possible while only using a left or right response key (see Greenwald et al., 1998). Since prior studies have shown that people can be ambivalent toward alcohol (Houben and Wiers, 2006), we decided to use three unipolar IATs to obtain the association between alcohol and a single attribute. One IAT assessed the association between ‘active’ positive arousal words versus ‘neutral’ words with photos of objects related to alcohol or objects not related to alcohol. Another IAT assessed the association between ‘relaxed’ positive sedation words versus neutral words with objects related or not related to alcohol. Lastly, one IAT assessed the association between ‘miserable’ negative words versus neutral words with objects related or not related to alcohol. These attribute categories were chosen because they represent the three main categories of alcohol expectancies (Goldman and Darkes, 2004). Stimulus pictures, in addition to stimulus words, were used in order to be able to have a neutral contrast category next to the alcohol target category. The perceptual features of the stimulus pictures were matched by using pictures of objects with approximately the same background, color, size and shape (see Appendix A). The words used (see Appendix B) were matched on number of letters, syllables, familiarity, and on valence and arousal values. The valence and arousal values of stimulus words were matched on group level (positive-arousal, positive-sedation, negative and neutral words) by using student word ratings (for exact procedure see Ames et al., 2007). In this study the three IATs were used in partially balanced order and programmed in ERTS 3.18 (Beringer, 1996). Each attribute discrimination block consisted of 20 trials and each combination block consisted of 40 trials. The D-2SD penalty score for practice and test was chosen as the main reaction time measure (see Greenwald et al., 2003). The internal consistency between practice (10) and test items (30) was acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .52 to .59) and comparable to most other implicit measures (see Houben & Wiers, 2006).

2.2.4 Expectancy Questionnaire

The direct measure of alcohol-related cognitions was an expectancy questionnaire consisting of an 18 unipolar item representing an explicit version of the implicit test words (see Appendix B; as in Wiers et al. 2002). Each item consisted of a statement on drinking alcohol (for example: ‘drinking alcohol makes me feel energetic’). Participants indicated the extent to which they (dis)agreed with each item on a 6-point Likert scale. The questionnaire consisted of three scales: a positive-arousal, a positive-sedation and a negative outcome scale. The internal consistency of all three scales was good (Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .73 to .84)

2.2.5 Self-Ordered Pointing Task

The Self-Ordered Pointing Task (SOPT) used in the current study was a computer-based version (Peterson et al., 2002) of the assessment developed by Petrides and Milner (1982) to measure working memory capacity. Participants were instructed to select pictures from a 3 × 4 matrix of 12 pictures. Each time a participant selected one picture, the arrangement of pictures in the matrix changed. The participant had to select a picture on a different location that had not been selected previously. The participant continued to select a different picture on each of 12 screen displays. The task was administered in three repetitions of the task using pictures of concrete items (e.g., a calculator, bus, stopwatch). Each task consisted of 12 trials and thus there were 36 trials in total. The number of correct responses is summed across the three tasks, with higher scores indicative of good working memory capacity. The internal consistency between the number of correct pictures across the three trials was good (Cronbach’s alpha = .74)

2.3 Procedure

Participants were recruited through five-minute classroom enrollment talks. After obtaining active consent from both the participants and parents, participants were tested in small groups of four at school in a separate test room during school time. The IAT was administered on a laptop with a separate response device. The order of the IAT was partially counterbalanced. The instructions were given on the computer screen preceding the task. Throughout the trials of both tasks, participants received feedback in red letters on their screen (incorrect response= ‘ERROR’, > 3000 ms. = ‘TOO SLOW’, < 150 ms. = ‘TOO FAST’). Next, the computer-based SOPT was administered. The instructions were given verbally by the experimenter. Throughout the trials of the tasks, participants received limited feedback on their screen; participants only received an error message indicating they had to select another picture when they had selected a picture on the same picture location as in the preceding turn. Subsequently, the participants filled out the expectancy questionnaire. The alcohol use questionnaire was administered last, in order to avoid any interference between having to report ones alcohol use and the measures of implicit and explicit alcohol-related cognitions. One month later, the participants were asked to fill out the alcohol use and alcohol-related problems questionnaire. All 88 participants were present at follow-up.

2.4 Data reduction

In order to obtain a normally distributed dependent index variable and to reduce the chances of a Type I error by multiple testing, we computed a log transformed standardized alcohol use index score in three consecutive steps. First, z - scores were calculated for eight different correlated outcome measures, namely number of times alcohol used in lifetime, number of times alcohol used in the past month, the number of standard drinks on a weekend day, the number of standard drinks on a weekday, number of times drunk in the last year, frequency of binges per two weeks, the number of binges in the last week, and the total sum score on the RAPI. Subsequently, the alcohol use index score was computed by calculating the mean of these eight z-scores. Finally, the alcohol use index was log transformed to obtain a normally distributed dependent variable.

3. Results

3.1 Outliers

Analyses included only those participants reporting that they had consumed alcohol in their lifetime. Two participants reported that they had never consumed alcohol and were therefore eliminated from further analyses. In addition, 5 participants were excluded from further analysis because they exceeded the mean error scores in the reaction time task by more than 3 standard deviations. The SOPT scores of participants that exceeded the mean by more than 3 standard deviations were recoded to the lowest value after removal of the outliers minus 1 (a method referred to as winsorizing). The analytic sample was 81.

3.2 Bivariate Analyses

As is shown in Table 1, the IAT measures and the alcohol expectancy measures were not correlated with each other (all p > .20). Furthermore, both the IAT measures and the alcohol expectancy measures were not correlated with the SOPT (except for the positive correlation between the negative IAT and SOPT of r = .21, p = .06, all p-values > .40). Additionally, although prior research has shown that poor working memory has been reliably associated with alcohol problems, the RAPI did not correlate with the SOPT (r = .07, p =.52).

Table 1.

Pearson Correlations for Explicit and Implicit Cognition and Working Memory Capacity

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Expl. Active | - | ||||||

| 2. Expl. Relaxed | .01 | - | |||||

| 3. Expl. Miserable | -.11 | -.45** | - | ||||

| 4. IAT Active | -.12 | -.02 | .13 | - | |||

| 5. IAT Relaxed | -.03 | .13 | -.06 | .21 | - | ||

| 6. IAT Miserable | -.05 | -.09 | .06 | .27* | -.11 | - | |

| 7. WMC | .06 | -.08 | .03 | .02 | -.01 | .21 | - |

Note. Expl Active = explicit positive-arousal alcohol cognitions; Expl Relaxed = explicit positive-sedation alcohol cognitions; Expl Miserable = explicit negative alcohol cognitions; IAT Active = D-2SD score for the positive-arousal IAT; IAT Relaxed = D-2SD score for the positive-sedation IAT; IAT Miserable = D-2SD score for the negative IAT; WMC = working memory capacity expressed in total number of correct responses on three consecutive Self Order Pointing Tasks

p < .05, two-tailed.

p < .01, two-tailed.

3.3 Multiple Regression Analyses

To assess whether there was a significant interaction between working memory capacity and alcohol-related cognition in the prediction of alcohol use, three hierarchical regression models for alcohol use were evaluated. One model tested the hypothesis that implicit and explicit positive-arousal cognitions interacted with working memory capacity. Another model tested the hypothesis that implicit and explicit positive-sedation cognitions interacted with working memory capacity. Lastly, one model tested the hypothesis that implicit and explicit negative cognitions interacted with working memory capacity. In each of these models the variables were centered before calculating the interaction term and a setwise hierarchical procedure was used. In Step 1 gender, age, and school attended were entered into the regression equation as background variables. In Step 2 the SOPT total sum score, the relevant (positive arousal, positive sedation or negative) IAT D-measure and the relevant (positive arousal, positive sedation or negative) expectancy sum score were added to the regression equation. In Step 3 the interaction between the relevant (positive-arousal, positive sedation or negative) expectancy sum score and the SOPT total sum score was added to the model. In Step 4 the interaction between the relevant (positive arousal, positive sedation or negative) IAT D-measure and the SOPT total sum score was added to the model. The alpha level was set at .05 for all analyses to ensure an optimal trade-off between completeness (not leaving out possibly interesting effects) and the correctness (restricting Type-II error) given the exploratory nature of the data. The term borderline significant was used when the p-value exceeded .05 but was less than .10.

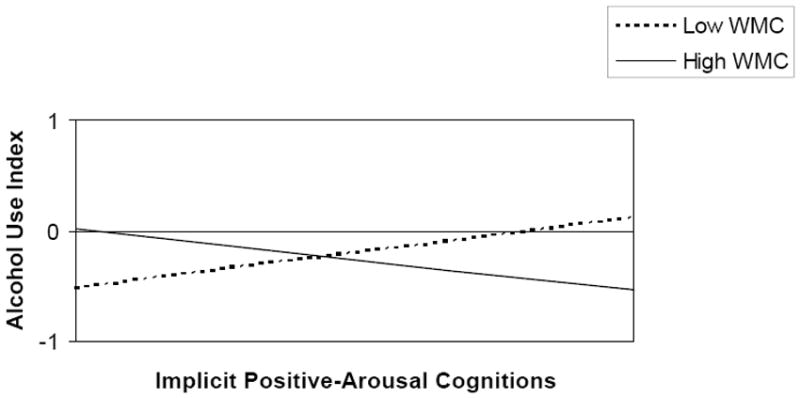

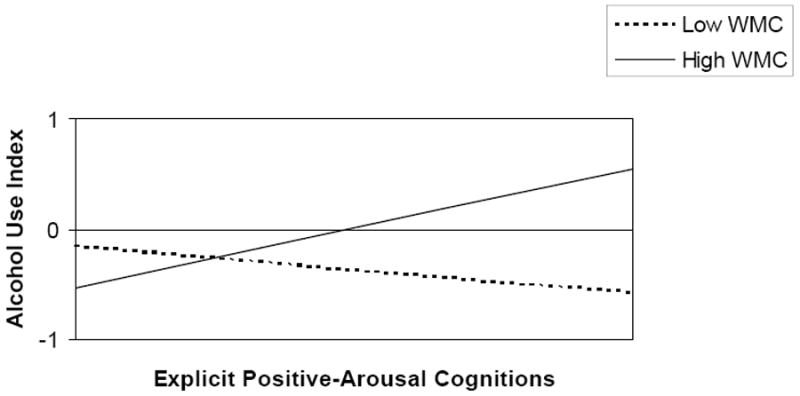

Only the model, in which the interactions between explicit and implicit alcohol-related cognitions and working memory capacity reached borderline significance in the prediction of alcohol use, was subjected to further analysis. Both interactions added significantly to the prediction of one-month follow-up alcohol use (Step 3 Δ R2 = .06, p = .02, Step 4 Δ R2 = .05, p = .02) above and beyond the background variables and main effects (see Table 2). Overall, the full model explained 31 % of all variance (R2 adjusted = .21, F (10, 70) = 3.08, p < .01). A trimmed model was obtained by removing all variables that were not (borderline) significant from the regression equation. The final trimmed model shows that both the interaction between working memory capacity and explicit positive-arousal cognitions and the interaction between working memory capacity and implicit positive-arousal cognitions predicted alcohol use after one month controlling for gender (see Table 3). Figure 2 shows that in participants with low working memory capacity, the implicit positive-arousal associations positively predicted one-month follow-up alcohol use. However, in the participants with high working memory capacity the opposite appeared to be true. In contrast Figure 3 shows that in participants with high working memory capacity, stronger explicit positive- arousal cognitions predicted greater alcohol use. In those with low working memory, there was no such relation between explicit positive arousal expectancies and subsequent alcohol use. Overall, the final trimmed model explained 27 % of all variance (R2 adjusted = .21, F (6, 74) = 4.55 p < .001).

Table 2.

Summary of Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting Alcohol Use After One Month (N = 81)

| Variable | B | SE B | β |

|---|---|---|---|

| Step1 | |||

| Gender | 0.29 | 0.17 | .19 |

| Age | -0.05 | 0.08 | -.09 |

| School 1 | -0.16 | 0.36 | -.05 |

| School 3 | 0.46 | 0.28 | .27 |

| School 4 | -0.15 | 0.21 | -.10 |

| Step 2 | |||

| Gender | 0.39 | 0.17 | .25* |

| Age | -0.05 | 0.08 | -.08 |

| School 1 | -0.03 | 0.36 | -.01 |

| School 3 | 0.40 | 0.27 | .23* |

| School 4 | -0.19 | 0.20 | -.12 |

| Expl. Active | 0.21 | 0.09 | .27* |

| IAT Active | 0.02 | 0.12 | .02 |

| WMC | 0.00 | 0.03 | .02 |

| Step 3 | |||

| Gender | 0.38 | 0.17 | .25* |

| Age | -0.06 | 0.08 | -.11 |

| School 1 | -0.14 | 0.35 | -.04 |

| School 3 | 0.31 | 0.27 | .18 |

| School 4 | -0.22 | 0.20 | -.14 |

| Expl. Active | 0.16 | 0.09 | .20 |

| IAT Active | 0.06 | 0.12 | .06 |

| WMC | 0.00 | 0.03 | .01 |

| WMC X Expl. Active | 0.09 | 0.04 | .28* |

| Step 4 | |||

| Gender | 0.37 | 0.16 | .24* |

| Age | -0.03 | 0.08 | -.05 |

| School 1 | -0.16 | 0.34 | -.05 |

| School 3 | 0.14 | 0.27 | .08 |

| School 4 | -0.25 | 0.19 | -.16 |

| Expl. Active | 0.12 | 0.09 | .15 |

| IAT Active | 0.02 | 0.12 | .02 |

| WMC | 0.02 | 0.03 | .07 |

| WMC X Expl. Active | 0.09 | 0.04 | .28* |

| WMC X IAT Active | -0.09 | 0.04 | -.25* |

Note. R2 = 0.12 (p = .07) for Step 1; Δ R2 = .07 (p = .13) for Step 2; Δ R2 = .06 (p < .05) for Step 3; Δ R2 = .05 (p < .05) for Step 4. Expl. Active = explicit positive-arousal alcohol expectancies; IAT Active = Implicit Association Test D2SD-score expressing the strength of the positive-arousal association with alcohol; WMC = working memory capacity expressed in total number of correct responses on three consecutive Self Order Pointing Tasks.

p < .05

p < .01

Table 3.

Summary of Simultaneous Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting Alcohol Use After One Month (N = 81)

| Variable | B | SE B | B |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | .37 | .16 | .24* |

| Expl. Active | .11 | .09 | .14 |

| IAT Active | .02 | .11 | .02 |

| WMC | .02 | .03 | .09 |

| WMC X Expl. Active | .10 | .04 | .28** |

| WMC X IAT Active | -.10 | .04 | -.29** |

Note. Expl. Active = explicit positive-arousal alcohol-related cognitions; IAT Active = Implicit Association Test d2SD-score expressing the strength of the positive arousal association with alcohol; WMC = working memory capacity expressed in total number of correct responses on three consecutive Self Order Pointing Tasks.

p < .05

p < .01

Figure 2.

Interaction between Working Memory Capacity and Implicit Positive-Arousal Cognitions in the Prediction of Alcohol Use (ß = -.29, p < .01). Alcohol Use Index = log transformed standardized sum score of eight outcome variables, Implicit Positive-Arousal Cognitions = Implicit Association Test d2SD-score expressing the strength of the positive arousal association with alcohol, WMC = working memory capacity expressed in total number of correct responses on three consecutive Self Order Pointing Tasks.

Figure 3.

Interaction between Working Memory Capacity and Explicit Positive-Arousal Cognitions in the Prediction of Alcohol Use (ß = .28, p < .01). Alcohol Use Index = log transformed standardized sum score of eight outcome variables, Explicit Positive-Arousal Cognitions = explicit positive-arousal alcohol expectancies score, WMC = working memory capacity score expressed in total number of correct responses on three consecutive Self Order Pointing Tasks.

Additionally, the analysis was repeated controlling for baseline drinking. In this analysis the interaction between implicit positive-arousal cognitions and working memory capacity was no longer significant (Δ R2 = .02, p = .44). This is not surprising, given the limited power of this analysis. Note that it is a different question whether change in drinking overtime can be predicted by an interaction between working memory capacity and implicit or explicit alcohol-related cognitions, or whether drinking behavior itself can be predicted by an interaction between working memory capacity and implicit or explicit alcohol-related cognitions. This study primarily evaluated implicit and explicit cognitive processes and interactions between specific cognitive processes and working memory in the prediction of one-month follow-up drinking.

4. Discussion

This study showed that the interaction between implicit and explicit positive-arousal cognitions and working memory capacity predicted one-month follow-up alcohol use in our sample of at-risk adolescents. Results from a hierarchical regression analysis showed that both interactions predicted unique variance in one-month follow-up alcohol use after controlling for the main effects and background variables. Interestingly, the signs of these interactions were in the opposite direction. That is, implicit positive-arousal cognitions predicted one-month follow-up alcohol use more strongly in students with lower levels of working memory capacity, whereas explicit positive-arousal cognitions predicted one-month follow-up alcohol use more strongly in students with higher levels of working memory capacity.

These results are in line with prior research on moderating effects of executive functions on implicit cognitive processes. Implicit cognition has been shown to be predictive of behavior in individuals with relatively low working memory capacity or attentional control (Grenard et al, manuscript under review; Payne, 2005). In addition, our findings are consistent with the findings of Tapert et al (2003) that explicit positive alcohol expectancies predicted alcohol use in substance use disorder adolescents with good verbal skills, whereas they did not in substance use disorder adolescents with poor verbal skills. Both findings indicate that alcohol expectancies may require deep processing in order for them to affect decision making and thus drinking. Finally, our results are in agreement with research that found dissociations between implicit and explicit cognitions. For instance, prior studies have shown that explicit cognitions predicted more deliberative behavior whereas implicit cognition predicted more spontaneous behavior (Asendorpf et al., 2002; Perugini, 2005). Our results are also congruent with the idea that implicit and explicit cognitions influence behavior through different pathways (e.g. Fazio and Towles-Schwen, 1999; Kahneman, 2003; Strack and Deutsch, 2004), which clearly has relevance for addictive behaviors (see Wiers and Stacy, 2006).

Given some limitations, these results should be interpreted with some caution. First, although we screened for schools with a high proportion of at-risk adolescents, we did not use a probability sampling strategy at an individual level and therefore we might not be able to generalize these results to other at-risk adolescent populations. In addition, we did not have the statistical power to adequately look at possible interactions with other background variables such as gender. It could be that for specific subgroups of at–risk adolescents the results would have been different.

Second, some authors question the validity of the IAT (e.g. Rothermund and Wentura, 2004; De Houwer, 2001). It has been proposed that participants performing the IAT may recode the stimuli based on other features than the associations the IAT intends to measure. Participants may sometimes select one ‘yes’- or ‘figure’-category and one ‘no’- or ‘ground’-category based on salience. This is referred to as the so-called figure-ground asymmetry (Rothermund and Wentura, 2004). This figure-ground asymmetry has been shown to sometimes influence IAT effects. However, in alcohol-IATs similar to the ones used here, this figure-ground asymmetry could only partly explain the results found for the negative associations and not at all for the positive and arousal associations (Houben and Wiers, 2006). Moreover, since we mixed conceptual and perceptual task characteristics within one test, we may have been able to provide some defense against possible recoding given the fact that not just one simple recoding strategy can be used. Since participants do not react just to one dimension of interest, the task may be less prone to response strategies the participants might want to employ (cf. De Houwer, 2003; Rinck and Becker, 2007). One could further argue that executive functions directly influence the estimates of associations provided by the IAT, for example through switch costs (Mierke and Klauer, 2003). However, we used the new scoring algorithm here (Greenwald et al., 2003), which provides an estimate of associations, while accounting for individual differences in switching capabilities (Greenwald et al., 2003; Mierke and Klauer, 2003). The hypothesis that the IAT results here are strongly influenced by the level of executive functions in this study is further unlikely given the lack of correlation between the IAT estimates of positive-arousal associations and working memory capacity. In addition, a similar pattern of results was found by Grenard et al. (manuscript under review) when using a different (not a reaction time task) and uncorrelated indirect measure of implicit alcohol-related cognitions (see Ames et al., 2007 for a direct comparison). Additionally, there is converging evidence from other research domains: Payne (2005) found a similar interaction between the IAT and executive control predicting the stereotyping behavior, and Hofmann et al (2007) found a similar interaction between appetitive associations assessed with a different variety of the IAT and experimentally manipulated levels of self regulatory control predicting eating behavior.

Third, since the IAT, SOPT and alcohol expectancy questionnaire were performed in a fixed sequence, it is possible that order effects may have played a role in the current results. However, this fixed sequence was chosen as the most optimal procedure to minimize method-related variance in a study focusing on individual differences (cf. Asendorpf et al., 2002).

Fourth, a possible limitation is that the follow-up period was relatively short. This places some restrictions on the prospective nature of this data. Further research is necessary to determine whether these interactions between alcohol-related cognition and working memory capacity are capable of predicting alcohol use in at-risk adolescents over longer time periods.

Finally, it must be noted that since the relationship between executive functions and alcohol use has been shown to be bidirectional it may be hard to disentangle the precise causal influences in the current pattern of results. For instance, it could well be that, due to prior drinking, working memory capacity is lowered and causes positive- arousal associations with alcohol to influence drinking behavior to a greater extent. This, in turn, could lead to heavier drinking and more alcohol-related problems. Yet, although prior research has shown that that poor executive functioning has been associated with more alcohol-related problems (e.g. Finn and Hall, 2004; Peterson et al., 1992; Tapert et al., 2002), in our sample the SOPT did not correlate significantly with the RAPI. This could be due to the fact that the average item score on the RAPI of .30 was not that high compared to a clinical sample (White and Labouvie, 1989). This is in line with prior studies that have shown that adolescents may experience the negative sedative effects of alcohol, which may serve to limit intake, less. Nevertheless these adolescents seem to be more sensitive than adults to alcohol-induced damage in structures that should restrict e.g. binge drinking (Spear, 2004). Additional research with longitudinal designs or more experimental designs are necessary to separate the bidirectional effects between executive functioning and alcohol use.

In sum, although these limitations should be taken into consideration when interpreting these results, this study does provide additional information for the role of alcohol-related cognitions in the development of (hazardous) drinking behavior. These results suggest that implicit and explicit alcohol-related cognitions influence drinking behavior through different pathways: adolescents with relatively good working memory capacity appear to make more “reasoned” drinking decisions, while adolescents with relatively poor working memory capacity appear to make more impulsive drinking decisions (cf. Strack & Deutsch, 2004). The obtained interaction effects, and especially the obtained dissociation in these effects, should be considered important given that interaction effects of continuous variables in field studies are often difficult to detect (McClelland and Judd, 1993). Because effect sizes are often attenuated in such analyses and thus notoriously difficult to uncover, McClelland and Judd (1993) concluded that it is more important to determine if an interaction effect exists than to focus on its effect size.

Thus, both the interaction between working memory capacity and implicit positive-arousal cognitions with alcohol and the interaction between working memory capacity and explicit positive-arousal cognitions could be taken into account when prevention and intervention methods are being developed. Different intervention methods might be effective for different subgroups of at-risk adolescents. On the one hand, at-risk adolescents with good working memory capacity might benefit from interventions that try to strengthen protective negative alcohol cognitions, such as a motivational interview, which appears feasible in at-risk adolescents (Grenard et al., 2007b). On the other hand, at-risk adolescents with poor working memory capacity might benefit from interventions that attempt to directly interfere with their automatic reactions, such as an attentional retraining (e.g. Wiers et al., 2006) or with interventions that aim at increasing their capacity to regulate impulses, such as a working memory training, as has been successfully used in children with ADHD (Klingberg et al., 2005). However, it should be noted that even if an increase in working memory capacity could also be achieved in high-risk adolescents, this does not replace the importance of motivation and goals: the adolescent still needs to be motivated or have a goal in mind to apply this executive control (Feldman-Barrett et al., 2004; Wiers et al, 2007). Future research is needed to indicate if and which methods can be included as proven effective components in intervention programs.

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the block sequence in the three Implicit Association Tests. AD = Attribute Discrimination, C = Combination, RAD= Reversed Attribute Discrimination, RC = Reversed Combination.

Table 4.

Means and Standard Deviations of Explicit Cognition, Implicit Cognition and Working Memory Capacity

| Low WMC (N= 48) |

High WMC (N = 33) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Expl Active | 4.18 (0.88) |

4.43 (1.07) |

| Expl Relaxed | 4.11 (1.01) |

3.94 (0.76) |

| Expl Miserable | 2.19 (0.96) |

2.29 (0.93) |

| IAT Active | 346.48 (229.57) |

387.13 (244.97) |

| IAT Relaxed | 303.12 (229.37) |

351.04 (232.50) |

| IAT Miserable | 397.68 (260.30) |

466.55 (286.44) |

| WMC | 27.94 (2.25) |

32.00 (1.15) |

Note. Expl Active = explicit positive-arousal alcohol cognitions on a 6-point Liker scale; Expl Relaxed = explicit positive-sedation alcohol cognitions on a 6-point Liker scale; Expl Miserable = explicit negative alcohol cognitions on a 6-point Liker scale; IAT Active = positive-arousal IAT score in ms; IAT Relaxed = positive-sedation IAT score in ms; IAT Miserable = negative IAT score in ms; WMC = working memory capacity expressed in total number of correct responses on three consecutive Self Order Pointing Tasks; Low WMC = participants who scored low on working memory capacity based on a median split; High WMC = participants who scored low on working memory capacity based on a median split.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Dutch Health Care Research Organization (ZON-Mw; 31000065) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; DA16094). The authors wish to thank Frans Feron and Femke van Lambaart for al their support on this project.

APPENDIX A

IAT picture stimuli

APPENDIX B

IAT word stimuli (Translated from Dutch)

| Positive Arousal stimuli (active word) | Neutral stimuli (neutral word) |

|---|---|

| excited | historical |

| energetic | apart |

| busy | steep |

| lively | wide |

| wild | compact |

| Positive Sedation stimuli (relaxed word) | Neutral stimuli (neutral word) |

| relaxed | normal |

| calm | blue |

| chill | flat |

| tranquil | central |

| comfortable | digital |

| Negative stimuli (miserable word) | Neutral stimuli (neutral word) |

| sad | daily |

| pain | square |

| sick | narrow |

| nauseous | common |

| miserable | totally |

Contributor Information

Carolien Thush, Department of Experimental Psychology, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands.

Reinout W. Wiers, Department of Experimental Psychology, Maastricht University, Maastricht, the Netherlands Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands and the Dutch Addiction Research Institute (IVO), Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

Susan L. Ames, Institute for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, USA

Jerry L. Grenard, Institute for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, USA

Steve Sussman, Institute for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, USA.

Alan W. Stacy, Institute for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, USA

References

- Ames SL, Grenard JL, Thush C, Sussman S, Wiers RW, Stacy AW. Comparison of indirect assessments of association as predictors of marijuana use among at-risk adolescents. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:204–218. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KG, Schweinsburg A, Paulus MP, Brown SA, Tapert S. Examining personality and alcohol expectancies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) with Adolescents. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:323–331. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asendorpf JB, Banse R, Mücke D. Double dissociation between implicit and explicit personality self-concept: The case of shy behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2002;83:380–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beringer J. Experimental Run Time System (ERTS), Version 3.18. Berisoft; Frankfurt, Germany: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bechara A. Decision making, impulse control and loss of willpower to resist drugs: A neurocognitive perspective. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1459–1463. doi: 10.1038/nn1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Tapert SF, Granholm E, Dellis DC. Neurocognitive functioning of adolescents: Effects of protracted alcohol use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Braun CJ, Hoplight B, Switzer RC, 3rd, Knapp DJ. Binge ethanol consumption causes differential brain damage in young adolescent rats compared with adult rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1712–1723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD, Clark DB, Beers SR, Soloff PH, Boring AM, Hall J, Kersh A, Keshavan MS. Hippocampal volume in adolescent-onset alcohol use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:737–744. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckel AW, Hesselbrock V, Bauer L. Relationship between alcohol-rleated expectancies and anterior brain functioningn in young men at risk for developing alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:476–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer J. A structural and process analysis of the Implicit Association Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;37:443–451. [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer J, Crombez G, Koster EHW, De Beul N. Implicit alcohol- related cognitions in clinical samples of heavy drinkers. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2004;35:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio RH, Towles-Schwen T. The MODE model of attitude-behavior processes. In: Chaiken S, Trope Y, editors. Dual Process Theories in Social Psychology. Guilford; New York: 1999. pp. 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Hall J. Cognitive ability and risk for alcoholism: Short-term memory capacity and intelligence moderate personality risk for alcohol problems. J Abnorm Psychol. 2004;113:569–581. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman-Barrett LF, Tugade MM, Engle RW. Individual differences in working memory capacity and dual-process theories of the mind. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:553–573. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MS, Darkes J. Alcohol expectancy multiaxial assessment: A memory network-based approach. Psychol Assessment. 2004;16:4–15. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychol Rev. 1995;102:4–27. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JLK. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:1464–1480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the implicit association test: 1. An improved scoring algorithm. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:197–216. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenard JL, Ames SL, Wiers RW, Thush C, Sussman S, Stacy AW. Working memory moderates the predictive effects of drug-related associations on substance use. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.3.426. manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenard JL, Ames SL, Wiers RW, Thush C, Stacy AW, Sussman S. Brief intervention for substance use among at-risk adolescents: A pilot study. J Adolesc Health. 2007b;40:188–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Rauch W, Gawronski B. And deplete us not into temptation: Automatic attitudes, dietary restraint, and self-regulatory resources as determinants of eating behavior. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2007;43:497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Houben K, Wiers RW. Assessing implicit alcohol associations with the Implicit Association Test: Fact or artifact? Addict Behav. 2006;31:1346–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jajodia A, Earleywine M. Measuring alcohol expectancies with the implicit association test. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17:126–133. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.2.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BT, Corbin W, Fromme K. A review of expectancy theory and alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2001;91:57–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BT, McMahon J. Alcohol motivations as outcome expectancies. In: Miller WR, Heather N, editors. Treating Addictive Behaviors, Applied Clinical Psychology. 2. Plenum Press; New York: 1998. pp. 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D. A perspective on judgment and choice. Am Psychol. 2003;58:697–720. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.9.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. The neural basis of addiction: A pathology of motivation and choice. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1403–1413. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MJ, Engle RW. The role of prefrontal cortex in working-memory capacity, executive attention, and general fluid intelligence: An individual-differences perspective. Psychon Bull Rev. 2002;9:637–671. doi: 10.3758/bf03196323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingberg T, Fernell E, Olesen PJ, Johnson M, Gustafsson P, Dahlstrom K, Gillberg CG, Forssberg H, Westerberg H. Computerized training of working memory in children with ADHD: A randomized clinical trial. J Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:177–186. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200502000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luria AR. The Role of Speech in the Regulation of Normal and Abnormal Behavior. Liveright Publications; New York: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland GH, Judd CM. Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychol Bull. 1993;114:376–390. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierke J, Klauer CJ. Method-specific variance in the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:1180–1192. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.6.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognit Psychol. 2000;41:49–100. doi: 10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfai T, Wood MD. Positive alcohol expectancies and drinking behavior: The influence of expectancy strength and memory accessibility. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15:60–67. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.15.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne BK. Conceptualizing control in social cognition: How executive functioning modulates the expression of automatic stereotyping. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;89:488–503. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perugini M. Predictive models of implicit and explicit attitudes. Br J Soc Psychol. 2005;44:29–45. doi: 10.1348/014466604X23491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JB, Finn PR, Pihl RO. Cognitive dysfunction and the inherited predisposition to alcoholism. J Stud Alcohol. 1992;53:154–160. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JB, Pihl RO, Higgins D, Lee A. NeuroCognitive Battery. Version 2.0. Deerfield Beach: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides M, Milner B. Deficits on subject-ordered tasks after frontal- and temporal-lobe lesions in man. Neuropsychologia. 1982;20:249–262. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(82)90100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinck M, Becker ES. Approach and avoidance in fear of spiders. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2007;38:105–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothermund K, Wentura D. Underlying processes in the Implicit Association Test (IAT): Dissociating salience from associations. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2004;133:139–165. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.133.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Wood MD, Wood PK, Raskin G. Alcohol outcome expectancies and alcohol use: A latent variable cross-lagged panel study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1996;105:561–574. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.105.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Self-report issues in alcohol-abuse: State of the art and future directions. Behav Assess. 1990;12:77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Adolescence and the trajectory of alcohol use: Introduction to part VI. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:202–205. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW. Memory activation and expectancy as prospective predictors of alcohol and marihuana use. J Abnorm Psychol. 1997;106:61–73. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW, Ames SL, Knowlton BJ. Neurologically plausible distinctions in cognition relevant to drug use etiology and prevention. Subst Use Misuse. 2004;39:1571–1623. doi: 10.1081/ja-200033204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW, Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Cognitive motivation and drug use: A 9-year longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:502–515. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack F, Deutsch R. Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. 2004;3:220–247. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Baratta BS, Abrantes BA, Brown SA. Attention dysfunction predicts substance involvement in community youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:680–686. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, McCarthy DM, Aarons GA, Schweinsburg AD, Brown SA. Influence of language abilities and alcohol expectancies on the persistence of heavy drinking in youth. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:313–321. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapert SF, Schweinsburg AD, Barlett VC, Brown SA, Frank LR, Brown GG, Meloy MJ. Blood oxygen level dependent response and spatial working memory in adolescents with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:1577–1586. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000141812.81234.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thush C, Wiers RW. Explicit and implicit alcohol-related cognitions and the prediction of current and future drinking in adolescents. Addict Behav. 2007;32:1367–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thush C, Wiers RW, Ames SL, Grenard JL, Sussman S, Stacy AW. Apples and oranges? Comparing indirect measures of alcohol-related cognition predicting alcohol use in at-risk adolescents. Psychol Addic Behav. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.587. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Longitudinal trends in problem drinking as measured by the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(5 Suppl 1):76A. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Bartholow BD, van den Wildenberg E, Thush C, Engels R, Sher KJ, Grenard JL, Ames SL, Stacy AW. Automatic and controlled processes and the development of addictive behaviors in adolescents: A review and a model. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86:263–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Cox WM, Field M, Fadardi JS, Palfai TP, Schoenmakers T, Stacy AW. The search for new ways to change implicit alcohol-related cognitions in heavy drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:320–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Stacy AW. Handbook of Implicit Cognition and Addiction. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, van Woerden N, Smulders FTY, De Jong PJ. Implicit and explicit alcohol-related cognitions in heavy and light drinkers. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:648–658. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.4.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SJ, Sayette MA, Fiez JA. Prefrontal responses to drug cues: A neurocognitive analysis. Nat Neurosci. 2004;1:211–214. doi: 10.1038/nn1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]