Abstract

With growing interest in online assessment of substance abuse behaviors, there is a need to formally evaluate the validity of the data gathered. The current investigation evaluated the reliability and validity of anonymous, online reports of young adults’ marijuana use and related cognitions. Young adults age 18 to 25 who had smoked at least one cigarette in the past 30 days were recruited over 14 months to complete an anonymous online survey. Of 3106 eligible cases, 1617 (52%) completed the entire survey. Of those, 54% (n = 884) reported past-month marijuana use (65% male, 70% Caucasian, mean age was 20.4 years [SD = 2.0]). Prevalence of marijuana use was reported reliably across three similar items, and inter-item correlations ranged from fair to excellent for measures of marijuana dependence symptoms and thoughts about marijuana use. Marijuana use frequency demonstrated good construct validity through expected correlations with marijuana use constructs, and non-significant correlations with thoughts about tobacco use. Marijuana frequency distinguished among stages of change for marijuana use and goals for use, but not among gender, ethnicity, or employment groups. Marijuana use and thoughts about use differed by stage of change in the hypothesized directions. Self-reported marijuana use and associated cognitions reported anonymously online from young adults are generally reliable and valid. Online assessments of substance use broaden the reach of addictions research.

Keywords: marijuana, validity, reliability, Internet assessment, young adults

Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit substance among young adults in the United States, with past-month use rates estimated at 18.1% for those age 18-25 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010b). Past-month marijuana use increased from 2009 to 2010 among both adolescents (Johnston, 2011) and young adults (SAMHSA, 2010b) in the U.S. and rates are highest among young adults compared to any other age group. Young adulthood is one of the most important developmental stages to target to understand patterns and processes associated with marijuana use.

The Internet is increasingly used in survey research of substance use (Lord, Brevard, & Budman, 2011; Sumnall, Measham, Brandt, & Cole, in press), and is a promising medium to understand substance use including marijuana among young adults. Internet assessment offers a number of benefits over face-to-face interviews including broader reach; greater inclusion of low-incidence or “hidden” populations; rapid, convenient input by respondents; and reduced bias in response to sensitive, potentially stigmatizing topics including illicit substance use (Cantrell & Lupinacci, 2007; Hines, Douglas, & Mahmood, 2010; Rhodes, Bowie, & Hergenrather, 2003; Schonlau et al., 2004). These benefits are relevant for the assessment of marijuana use in American young adults, almost all of whom use the Internet (93% in a recent survey; Lenhart, Purcell, Smith, & Zickuhr, 2010). Young adults remain the age group most likely to go online and are less likely to present to traditional research settings for studies of health behavior than those in other age groups (Bost, 2005; Davies et al., 2000).

As with traditional paper and pencil measures, formal study is needed to evaluate whether online measures are psychometrically sound. Web-based reports of alcohol consumption among college students have demonstrated reliability and validity when compared to face-to-face interviews (Khadjesari et al., 2009; Miller et al., 2002) or mail surveys (McCabe, Boyd, Couper, Crawford, & D’Arcy, 2002; McCabe, Diez, Boyd, Nelson, & Weitzman, 2006), and they have also been used in evaluations of Internet-based interventions aimed at reducing alcohol intake and related harm (Cunningham, Humphreys, Koski-Jannes, & Cordingley, 2005; Cunningham, Humphreys, Kypri, & van Mierlo, 2006; Koski-Jannes, Cunningham, & Tolonen, 2009; Postel, de Haan, ter Huurne, Becker, & de Jong, 2010; White et al., 2010).

Previous work with college student samples has also demonstrated that online reports of marijuana use frequency are similar to those from samples recruited through the mail (McCabe et al., 2002) and marijuana use can be successfully assessed online over time (Fromme, Corbin, & Kruse, 2008; Lee, Neighbors, Hendershot, & Grossbard, 2009; Lee, Neighbors, Kilmer, & Larimer, 2010). However, little is known about the reliability and validity of online marijuana use from populations other than college students whose identity can usually be verified with enrollment statistics or student email addresses. One study assessed the prevalence of marijuana use in samples recruited both online and at a waterpipe café, although a formal test of validity was not conducted (Smith-Simone, Maziak, Ward, & Eissenberg, 2008). A comparison of marijuana and other substance use reports from online panelists recruited through a survey sampling company and a Dutch national panel surveyed with computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) found lower prevalence in the CAPI cohort compared to the online sample for all substances (weighted estimates of past-year marijuana use were 24.6 for the online sample and 11.4 for the CAPI sample among those ages 15-24), although the CAPI sample was more representative of the Dutch general population (Spijkerman, Knibbe, Knoops, Van De Mheen, & Van Den Eijnden, 2009).

In addition to prevalence and frequency of marijuana use, there is a need to validate online reports of common correlates of substance use that have not been previously adapted for use with marijuana. For example, core constructs in the Transtheoretical Model of behavior change (TTM; DiClemente et al., 1991; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983), including stage of change, decisional balance (the pros and cons of change), situational temptations to engage in a behavior, all of which have demonstrated associations with tobacco use and other health behaviors (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983; Prochaska et al., 1994; Ramo, Hall, & Prochaska, 2011), have yet to be validated as they relate to marijuana use. The thoughts about abstinence measure that assesses desire, perceived success, difficulty, and abstinence goals in relation to tobacco, alcohol, and opiate use also has not been adapted for use in study of marijuana behavior (Hall, Havassy, & Wasserman, 1990, 1991; Prochaska et al., 2004). Marijuana use may be different because it’s addictive potential is often questioned (Budney, 2006). It is important to determine if the relationships to substance use, stage of change, and other thoughts about use hold true in an online sample of young adult marijuana users.

Previous work in our research group demonstrated self-reported tobacco use and thoughts about using tobacco were generally reliable and valid as assessed in an anonymous online survey with young adult smokers throughout the U.S. (Ramo et al., 2011). The present study extended these findings in a separate, larger sample by examining the psychometric properties of marijuana use self-reported anonymously online by young adults who use both tobacco and marijuana. Measures evaluated included both commonly administered measures of marijuana use and cravings where psychometric properties have already been established in paper-and-pencil formats, as well as measures of tobacco and other substance use that were adapted specifically to assess marijuana use cognitions. Thus, this study provided an analysis of associations across multiple measures of marijuana-related constructs in young adults.

To assess reliability of self-reported marijuana use, we evaluated agreement among three single item measures assessing the prevalence of past 30-day marijuana use for the entire sample and by key demographic subgroups (i.e., gender, ethnicity, and age). We also evaluated agreement between two multi-item measures of marijuana use frequency. With multi-item measures, we evaluated internal-consistency reliability.

Construct validity and concurrent criterion validity were evaluated for past 30-day marijuana use frequency and stage of change for marijuana use. Construct validity is the extent to which a construct can be operationalized through demonstrating relations with constructs that should be similar (convergent validity) and non-relations with constructs that should be dissimilar (divergent validity). Concurrent criterion validity is a construct’s ability to distinguish between groups that it should be able to distinguish at the same point in time. Based on previous findings in the literature, we hypothesized the following:

Convergent validity: Frequency of past 30-day marijuana use would be associated with greater marijuana dependence symptoms (Adamson et al., 2010; Adamson & Sellman, 2003), craving (Heishman, Singleton, & Liguori, 2001), and temptations (Myers, Stice, & Wagner, 1999); lower desire to quit using marijuana; lower quitting-related efficacy; greater expected difficulty for quitting marijuana; more pros and fewer cons of using marijuana (Elliott, Carey, & Scott-Sheldon, 2011); and greater tobacco and marijuana interaction expectancies (Rohsenow, Colby, Martin, & Monti, 2005);

Divergent validity: Past 30-day marijuana use would be unrelated to thoughts about tobacco use (Ramo, Prochaska, & Myers, 2010);

Concurrent criterion validity for marijuana use: Frequency of past 30-day marijuana use would be greater among those in an earlier stage of change (precontemplation and contemplation) compared to those ready to change (preparation), and among those with a goal of non-abstinence compared to abstinence (DiClemente et al., 1991; Prochaska et al., 2004). Frequency was also expected to be greater among men than women and among those who were unemployed compared to employed (SAMHSA, 2010b). Although the data on ethnic differences in marijuana use frequency have been inconclusive, we also examined ethnicity as a correlate of marijuana use frequency among past month users, expecting that Asian-American young adults would have lower frequency than other ethnicities (Ellickson, Martino, & Collins, 2004; SAMHSA, 2004).

Validity for stage of change for marijuana use: Consistent with the TTM and prior research on tobacco use (Prochaska et al., 2004; Ramo et al., 2011), we hypothesized that participants’ marijuana use characteristics, desire to quit, expected success with quitting, anticipated difficulty with staying quit, abstinence goals, perceived pros and cons of smoking, temptation, and craving to use marijuana would vary as a function of stage of change. Finally, we explored whether nicotine and marijuana interaction expectancies would vary as a function of marijuana stage of change.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants were young adults between the ages of 18 and 25 who were English literate and reported smoking at least one cigarette in the past 30 days. This cross-sectional survey study used three Internet-based recruitment methods described in detail previously (Ramo, Hall, & Prochaska, 2010), including: 1) a paid advertisement campaign on Facebook that targeted only those identifying as age 18 to 25 years; 2) a free campaign on Craigslist; and 3) a paid advertising campaign through a survey sampling company that also targeted those 18 to 25 years. Internet-based advertisements invited young adults to participate in a 20-minute online survey with a chance to win a prize in a drawing (worth either $25 or $400). The goal of the main study upon which this study was based was to examine patterns of tobacco and marijuana use among young adults. Therefore, advertisements were targeted to tobacco smokers (e.g., picture of a pack of cigarettes) and/or both tobacco and marijuana use (e.g., picture of a pack of cigarettes and a marijuana plant). The campaign ran for 13 consecutive months, 2/28/10 - 4/4/11. Advertisements contained a hyperlink that directed potential participants to the study’s IRB-approved consent form that described the survey, the risks including loss of privacy and the study’s certificate of confidentiality to protect privacy, details of the raffle drawing, and study contact information. Following the consent form, verification questions based on those developed by Palmer and colleagues (2008) confirmed English literacy and understanding of the consent process. Questions covered the content of the study (e.g., “What is this study about?”) as well as ethical issues (e.g., “What are some of the possible risks associated with participating in this study? [select all that apply]”), and participants were required to answer all questions correctly before moving on the next page of the survey. Those who consented completed a brief screener to determine eligibility. Date of birth and age were asked multiple times throughout the survey to check for validity of responses. Reasons for exclusion included discrepancy in reported date of birth and age or multiple entries of either item, with either indicating they were either too young or too old to participate, or an entry that was found to be ineligible quickly followed by an entry from the same IP address that was found to be eligible (suggesting that the participant was changing data to enter the survey; n = 112); multiple survey entries with the same email address (n = 12); and inconsistency in reported recruitment method (e.g., participant reported s/he came from Craigslist, but entered through Facebook; n = 6). Surveys with invalid responses (e.g., every entry was the same across the entire survey; n = 10) also were excluded.

Computer Internet Protocol (IP) addresses were tracked, and only one entry was allowed from a single computer to prevent duplicate entries from the same person; however, multiple entries were allowed from the same Internet connection (dormitories, apartment buildings). The secure online survey had data encryption for added security protection. Participants wererequired to answer all questions before they could continue to the next page of the survey, but could quit the survey at any time.

At three pre-specified intervals throughout the survey recruitment process, raffle drawings were made for one of two $25 gift cards to national or online retailers and one $400 gift card to Apple stores, for a total of nine prizes over the 15-month duration of the study. Only those who had completed the survey, whose entries were deemed valid, and who had provided a valid email address were eligible for participation in the raffle drawing.

During the 14-month recruitment period, the online survey received more than 5658 hits, 5465 people gave online consent to determine eligibility to complete the survey, of which 3106 (57%) were eligible. Of the 3106 eligible cases, 1877 (60.4%) completed demographic information and 1617 (52%) completed the entire survey and were used for analysis in the present study. The vast majority (85%) were recruited from Facebook, 8% came from Craisglist, and 7% came from the survey sampling company. Compared to those who only completed demographic information (n = 260), those who completed the survey were more likely to be women (37% vs. 28%; χ2(2, N = 1877) = 9.5, p = .009), more likely to be multi-ethnic (15.6 vs. 8.1), less likely to be African-American (3.2% vs. 6.6%; χ2(4, N = 1875) = 17.0, p = .002), and were slightly older (20.5 years vs. 19.8 years; t(1875) = −5.2, p < .001). There were no significant differences in household income, employment/student status, region of residence, or subjective social status between those who left the survey early and those who completed.

Measures

The survey assessed basic sociodemographic variables, and participants’ residence was categorized according to the four U.S. Census Regions (U. S. Census Bureau, 2010). The MacArthur Scale of Subjective Social Status (SSS; Adler, Epel, Castellazzo, & Ickovics, 2000) presented a “social ladder” and asked individuals to place an “X” on the rung on which they feel they stand in the United States in terms of occupation, income, and social standing (range: 1 to 10). Table 1 details the marijuana measures administered. Past month marijuana use was assessed in three ways: 1) a screening item developed for the current study; 2) National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) items, which have demonstrated high agreement between self-report of past 30-day substance use and urine test results (89% for marijuana; Harrison, Martin, Enev, & Harrington, 2007); and 3) the Timeline Followback (TLFB), which presents a calendar and asks participants to retrospectively estimate their daily tobacco and marijuana consumption over 30 days prior to the assessment. Marijuana dependence symptoms were assessed initially with the Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test (CUDIT) and then switched to the recommended Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R). As scale total scores were slightly different for the two measures (see Table 1), CUDIT and CUDIT-R scores were converted to z-scores and pooled for all validity analyses. The Marijuana Craving Questionnaire – Short Form (MCQ-SF) assessed marijuana cravings. The temptations questionnaire for alcohol was adapted to assess temptations to use marijuana. We adapted the 3-item Stages of Change - Short Form for smoking to assess stage of change for marijuana use. The Thoughts about Abstinence measure, adapted for cognitions about marijuana, assessed desire to quit, abstinence self-efficacy, perceived difficulty of staying quit, and goal related to marijuana use. An adapted version of the 42-item Decisional Balance- Drug and Alcohol Use Scale assessed the pros and cons of marijuana use. Raw scores were converted to t-scores and summed for pro and con scales consistent with previous literature (Velicer, DiClemente, Prochaska, & Brandenberg, 1985). An adapted version of the Nicotine and Other Substances Interaction Questionnaire (NOSIE) assessed beliefs about the effects of smoking on marijuana use and the effect of marijuana use on smoking (interaction expectancies).

Table 1. Description of measures.

| Construct | Measure | Reference | Sample Item/Codinga | Number of items |

Rangeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marijuana Use | Screener | “Have you used ANY of the following substances in the past 30 days? (Y/N)” |

1 | 0-1 | |

| 2007 NSDUH items |

(RTI International, 2006) | “How long has it been since you last used marijuana?” (within the past 30 days; more than 30 days age but within the past 12 months; more than 12 months ago) |

1 | ||

| “During the past 30 days, what is your best estimate of the number of days you used marijuana or hashish during the past 30 days?” (All 30 days; 20 to 29 days; 10 to 19 days; 6 to 9 days; 3 to 5 days; 1 or 2 days; 0 days) |

1 | ||||

| Timeline Followback |

(Sobell & Sobell, 1996) | Days using marijuana in the past 30 | 1 | 0 - 30 | |

| Marijuana Dependence symptoms |

CUDIT | (Adamson & Sellman, 2003) | “How often during the past 6 months did you have a feeling of guilt or remorse after using cannabis?” (never; less than monthly; monthly; weekly; daily or almost daily) |

10 | 0-40 |

| CUDIT-R | (Adamson et al., 2010) | “How often in the past 6 months have you had a problem with your memory or concentration after using marijuana?” (never; less than monthly; monthly; weekly; daily or almost daily) |

8 | 0-32 | |

| Cravings/Temptations | MCQ-SF | (Heishman et al., 2001) | “I would feel more in control of things right now if I could smoke marijuana” (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) |

12 | 12-84 |

| Temptations questionnaire |

(Snow, Prochaska, & Rossi, 1994) | “When I am feeling depressed” (1 = Not at all tempted to 5 = Extremely tempted) |

30 | 30-150 | |

| Stage of Change for Marijuana Use |

Stages of Change-Short Form |

(DiClemente et al., 1991) | Precontemplation (>6 months); Contemplation (<6 months, >30 days); Preparation (≤30 days, past year quit attempt) |

1 | |

| Desire to quit marijuana Abstinence self-efficacy Perceived difficulty staying quit |

TAA – Marijuana |

(Hall et al., 1990) | 1 | 1-10 | |

| Abstinence Goal | No goal; total abstinence; something in between (“some change”) | ||||

| Pros and Cons of Marijuana Use |

Marijuana Decisional Balance |

(DiClemente, 1999) | Pro: “Using marijuana relaxes me” | 22 | 22-110 |

|

Con: “Using marijuana is bad for my health” (1 = “Not at all Important” to 5 =“Extremely Important”) |

22 | 22-110 | |||

| Tobacco and Marijuana Interaction Expectancies |

NOSIE- Marijuana |

(Rohsenow et al., 2005) | “I need a cigarette while I am using marijuana” (1=”Never” to 5=”Always” |

13 | 65 |

Note. NSDUH = National Survey of Drug use and Health; CUDIT = Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test; MCQ-SF = Marijuana Craving Questionnaire – Short Form; TAA = Thoughts About Abstinence; NOSIE = Nicotine and Other Substance Interaction Questionnaire; S-SCQ = Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Short form.

Coding is given for categorical variables, Sample items are given for continuous variables.

Ranges are not given for categorical variables.

Measures of thoughts about tobacco use were used for tests of divergent validity. The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Short form (S-SCQ; Myers, MacPherson, McCarthy, & Brown, 2003; Ramo et al., 2011) measured smoking-related outcome expectancies (Cronbach’s alpha = .90), the Smoking Temptation-Short form (Velicer, DiClemente, Rossi, & Prochaska, 1990) assessed temptations to smoke cigarettes (Cronbach’s alpha = .86), and the Smoking Decisional Balance (Velicer et al., 1985) assessed the pros (Cronbach’s alpha = .80) and cons (Cronbach’s alpha = .73) of smoking.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of those reporting at least one past-month day of marijuana use on the Timeline Followback (n = 884), non-users (n = 733) and the full sample (N = 1617) are presented in Table 2. Compared to those who had not used marijuana recently, past 30-day marijuana users were slightly younger (t(1615) = −3.40, p = .001), less likely to be Caucasian (χ2(4, N = 1617) = 12.88, p = .012), less likely to be employed (χ2(3, N = 1617) = 9.54, p = .023), and had a higher household income (χ2(6, N = 1617) = 17.76, p = .007).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of young adult smoking samples.

| Characteristic | Past 30-day Marijuana users (n = 884) |

Non-past 30-day Marijuana users (n = 733) |

Full sample (N = 1617) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | |||

| Female | 34.7 | 39.7 | 37.0 |

| Male | 64.9 | 59.8 | 62.6 |

| Transgender | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

| Age (M[SD])* | 20.4 (2.0) | 20.7 (2.1) | 20.5 (2.1) |

| Race/ethnicity (%)* | |||

| African-American/Black | 3.5 | 2.9 | 3.2 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 2.6 | 5.3 | 3.8 |

| Caucasian/White | 69.8 | 72.4 | 71.0 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 6.8 | 5.9 | 6.4 |

| Other | 17.3 | 13.5 | 15.6 |

| Employment status (%)* | |||

| Full-time | 26.7 | 33.6 | 29.8 |

| Part-time | 17.9 | 15.1 | 16.6 |

| Unemployed/Homemaker | 25.9 | 23.3 | 24.7 |

| Student | 29.5 | 28.0 | 28.8 |

| Education (M years [SD]) | 13.0 (1.7) | 13.0 (2.0) | 13.0 (1.8) |

| Annual family incomea (%)** | |||

| Less than $20,000 | 24.0 | 28.8 | 26.2 |

| $21,000 - $40,000 | 20.6 | 23.5 | 21.9 |

| $41,000 - $60,000 | 14.8 | 15.8 | 15.3 |

| $61,000 - $80,000 | 11.1 | 10.5 | 10.8 |

| $81,000 - $100,000 | 10.0 | 7.8 | 9.0 |

| Over $100,000 | 19.6 | 13.7 | 16.8 |

| Subjective social status (M[SD]) | 5.8 (1.9) | 5.8 (1.8) | 5.8 (1.9) |

| Region (%) | |||

| Northeast | 18.7 | 20.2 | 19.4 |

| Midwest | 24.9 | 26.9 | 25.8 |

| South | 27.9 | 26.3 | 27.2 |

| West | 28.5 | 26.6 | 27.6 |

Note. T-tests and chi-square tests evaluated differences between Past 30-day marijuana users and non-users on all sociodemographic characteristics.

Family income included parental income, if relevant.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Reliability

Reported Agreement in Marijuana Use

We compared prevalence estimates of past month marijuana use from three similar items: the study screening question, the NSDUH marijuana use question, and the TLFB for the full sample and demographic subgroups (gender, ethnicity, and age; Table 3). Kappa values were above .7 for almost all subgroups and the full sample, indicating high agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977). African-Americans reported higher rates of marijuana use on the NSDUH item (74%) than the other two items (58% and 60%) and had lower kappa values than other subgroups or the full sample (.46 and .64, respectively).

Table 3. Prevalence estimate and agreement among three items assessing prevalence of past 30-day marijuana use (N = 1617).

| Characteristic | Screener: “Have you used ANY of the following substances in the PAST MONTH (30 days): Marijuana (y/n)” |

NSDUH: How long has it been since you last used marijuana (% reporting “within the past 30 days”) |

TLFB: % reporting marijuana use at least once in the past 30 days |

Agreemen among itemts |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| kappaa | kappab | ||||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 52.8% | 61.1% | 51.3% | .86 | .86 |

| Male | 61.0% | 67.2% | 56.7% | .81 | .80 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| African- | 57.7% | 73.8% | 59.6% | .46 | .64 |

| American | |||||

| Asian/Pacific | 41.9% | 54.5% | 37.1% | .72 | .76 |

| Islander | |||||

| Caucasian | 57.7% | 64.0% | 53.7% | .83 | .83 |

| Hispanic/ Latino |

58.3% | 63.3% | 58.3% | .78 | .76 |

| Multiple/ other |

63.1% | 69.9% | 60.7% | .91 | .87 |

| Age group | |||||

| 18-21 | 60.4% | 68.2% | 57.5% | .81 | .84 |

| 22-25 | 52.6% | 57.6% | 48.4% | .85 | .78 |

| Total (%, n) | 57.9% (937) | 55.3% (895) | 54.7% (884) | .83 | .82 |

Note. NSDUH = National Survey on Drug Use and Health; TLFB = Timeline Followback.

kappa statistic reported for Screen and NSDUH items.

kappa statistic reported for Screen and TLFB items.

% is proportion of those reporting yes to item, within each category.

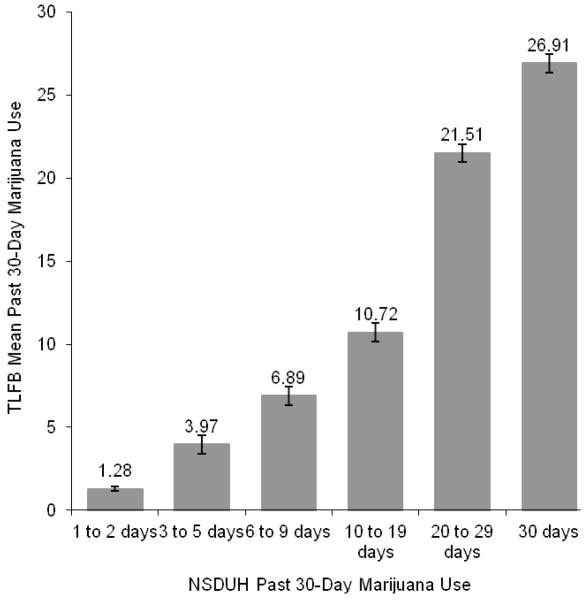

Two items assessed the number of days of marijuana use in the past 30-days: one continuous item (TLFB) and one ordinal item (NSDUH question). The correlation between these two items was high (r = .83, p = .001). Figure 1 displays the mean days of marijuana use reported on the continuous TLFB item by ordinal NSDUH categories.

Figure 1.

National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) past 30-day marijuana use item categories by mean days using marijuana on the Timeline Followback (TLFB). Standard errors are represented in the figure by the error bars attached to each column.

Inter-item Reliability of Multi-item Measures

Table 4 reports means, standard deviations, and inter-item correlations (Cronbach’s alpha) for multi-item measures. Almost all measures demonstrated good to excellent internal-consistency reliability based on classifications from Ciccetti (1994; Cronbach’s alpha ranges from .88 to .96 for full scales). The lowest internal consistency reliability was found for both versions of the CUDIT, α = .66 for the CUDIT-R and .76 for the CUDIT. Additionally, within the measures, most scales showed fair to excellent internal-consistency reliability (α > .70), with the exception of the Compulsivity scale of the MCQ (α = .67), and the “Tobacco increases marijuana use/urges” scales of the Marijuana NOSIE (α = .63).

Table 4. Reliability of marijuana measures and validity of marijuana stage of change: Interitem correlations (alpha), means, and standard deviation for marijuana measures and differences by stage of change among past month marijuana users (n = 884).

| Measures | α | Total Mean (SD) |

PCd (n = 683) |

C (n = 57) |

P (n = 69) |

F/ χ2 | p-value | Tukey HSD Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependence symptomsa | 0.08 (0.94) | −0.56 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 4.98 | .01 | PC < C | |

| CUDIT (n = 140) | .76 | 10.93 (6.65) | ||||||

| CUDIT-R (n = 679) | .66 | 11.93 (5.87) | ||||||

| Desire to quit (1-10) | --c | 2.46 (2.51) | 1.59 | 4.31 | 6.26 | 278.70 | .00 | PC < C < P |

| Quitting efficacy (1-10) | -- | 6.93 (3.50) | 6.62 | 7.77 | 8.32 | 8.63 | .00 | PC < P |

| Difficulty of quitting (1-10) | -- | 4.46 (3.32) | 4.61 | 4.67 | 3.45 | 3.51 | .03 | P < PC = C |

| Marijuana cravings (MCQ-SF) | .88 | 50.37 (16.48) | 44.19 | 39.76 | 39.80 | 2.88 | .06 | |

| Compulsivity | .67 | 6.61 (4.64) | 6.55 | 6.52 | 7.07 | 0.18 | .83 | |

| Emotionality | .77 | 13.01 (5.39) | 13.35 | 11.82 | 12.60 | 1.47 | .23 | |

| Expectancy | .71 | 15.07 (5.05) | 15.47 | 14.21 | 13.90 | 2.25 | .11 | |

| Purposefulness | .74 | 14.91 (4.74) | 15.38 | 13.73 | 13.30 | 4.66 | .01 | P < PC |

| Temptations: Marijuana | .96 | 88.77 (29.52) | 91.52 | 81.11 | 80.85 | 6.14 | .00 | P < PC |

| Decisional Balance: Marijuanab | .94 | |||||||

| Pros | .93 | 0.11 (0.97) | 0.14 | −0.06 | 0.10 | 1.01 | .36 | |

| Cons | .93 | −0.01 (0.98) | −.010 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 10.99 | .00 | PC < C = P |

| Interaction expectancies (NOSIE-MJ) | .88 | 30.06 (11.46) | 6.43 | 6.37 | 6.98 | 1.44 | .24 | |

| Marijuana increases tobacco use and urges | .90 | 13.47 (6.29) | 2.70 | 2.78 | 2.70 | 0.10 | .90 | |

| Smoking increases marijuana use and urges | .63 | 6.20 (3.01) | 2.07 | 1.93 | 2.14 | 0.62 | .54 | |

| Smoking to cope with marijuana urges | .93 | 10.34 (5.79) | 1.67 | 1.66 | 2.14 | 7.30 | .00 | PC = C < P |

Note. PC = precontemplation; C = contemplation; P = preparation; CUDIT = Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test; MCQ-SF = Marijuana Cravings Questionnaire, Short-Form; NOSIE-MJ = Nicotine and Other Substance Interaction Questionnaire – Marijuana.

CUDIT and CUDIT-R raw scores converted to z-scores.

Pro and Con raw scores converted to t-scores.

Cronbach’s alpha is not reported for 1-item measures.

Due to missing data, stage of change analyses are only available for 809 individuals.

Validity

Marijuana use

Construct validity (convergent and divergent validity) and concurrent criterion validity were evaluated for past 30-day marijuana use frequency. Due to very strong agreement among the three measures of marijuana prevalence (Table 3), the continuous item from the TLFB was used as a measure of past 30-day marijuana frequency. Only those survey respondents who indicated they used marijuana in the past month were included in these analyses (n = 884).

Construct validity

Greater past 30-day marijuana use was significantly associated with all hypothesized constructs including greater marijuana dependence symptoms (CUDIT/CUDIT-R (z-scores): r(817) = .36, p < .001), greater marijuana craving (r(817) = .43, p < .001), lower desire to quit using marijuana (r(817) = −.34, p < .001), lower expected success (r(817) = −.29, p < .001) and greater perceived difficulty with quitting marijuana use (r(817) = .30, p < .001), more temptations to use marijuana (r(793) = .46, p < .001), more pros and fewer cons associated with marijuana use (r(817) = .31, p < .001), and greater marijuana and tobacco interaction expectancies (r(817) = .20, p < .001).

In evaluations of divergent validity, as hypothesized, there was no significant correlation between past 30-day marijuana use and tobacco use expectancies (r(754) = .05, p = .168) or pros of smoking cigarettes (r(882) = −.01, p = .778). Although significantly correlated, relationships between past 30-day marijuana use and self-efficacy for quitting smoking (r(882) = .09, p = .006), or cons of smoking cigarettes (r(882) = −.10, p = .002) were both at or below r = .1, the cutoff for a weak association (Cohen, 1988, 1992).

Concurrent criterion validity

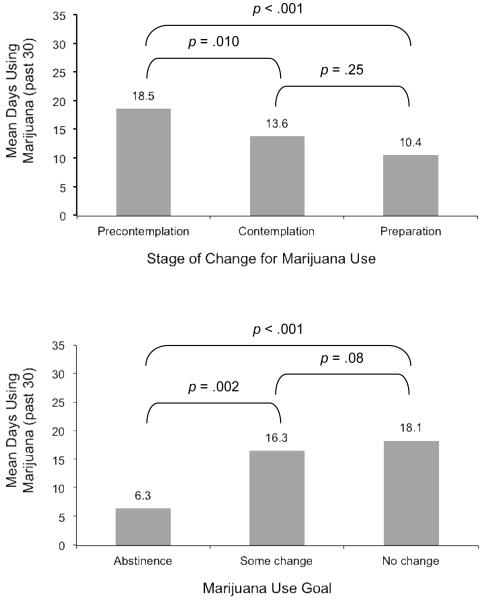

Among past 30-day marijuana users, frequency of past 30-day marijuana use did not distinguish participants based on gender, ethnicity, or employment/educational status. As hypothesized, past 30-day marijuana use distinguished among marijuana stage of change categories (F(2, 806) = 18.7, p = .001; Figure 2). Posthoc comparisons with Sidák type-I error corrections indicated that those in precontemplation smoked significantly more cigarettes than those in preparation (difference = 7.96, p < .001) or contemplation (difference = 4.57, p = .010), while those in contemplation and preparation did not differ significantly from each other (difference = 3.38, p = .25). Marijuana use frequency also distinguished among goals for marijuana use (F(2, 816) = 9.42, p = .001; Figure 2), such that those who had a goal of complete abstinence smoked fewer days in the past month compared to those who had no goal (difference = 11.79, p < .001) or a goal somewhere between no change and abstinence (difference = 9.99, p = .002). There was no difference in days using between those with no-goal and a goal between abstinence and no change (difference = 1.80, p = .08)

Figure 2.

Mean days using marijuana by a) marijuana stage of change (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation; n = 809) and b) marijuana abstinence goal (abstinence, middle, no change; n = 819).

Marijuana Stage of Change

A significant stage association was observed for abstinence goals (χ2(2, N = 753) = 59.2, p < .001). Precontemplators (52%) were most likely to report no goal compared to contemplators (35.4%) and those in preparation (19.4%). In contrast, only 0.5% of precontemplators, but 2% of contemplators, and 10% of those in preparation endorsed the goal of total abstinence. Table 4 reports the results of ANOVAs and Tukey HSD tests examining marijuana stage of change associations with marijuana use, thoughts about use and TTM constructs. Significant stage associations were observed for marijuana dependence symptoms, desire to quit, expectancy of abstinence success (efficacy), and cons of using marijuana, with precontemplators having the lowest values and those in preparation having the highest values. Significant associations were also observed for perceived difficulty of maintaining abstinence and temptations to use marijuana, with those in preparation having lowest values. Marijuana cravings were not significantly different across stages, although the Purposefulness scale of the MCQ showed significantly higher scores among precontemplators compared to the other two groups. There was not a significant stage association by pros for using marijuana. There were no significant overall differences in nicotine and marijuana interaction expectancies by stage, although those in preparation had higher expectations that smoking cigarettes would help cope with urges to use marijuana compared to those in precontemplation and contemplation.

Discussion

Overall, anonymous online reports of marijuana use and related cognitions among young adults demonstrated adequate reliability and validity with a few exceptions. We found strong relationships among items that assessed the prevalence and frequency of marijuana use, with the exception that African-American young adults showed lower inter-item agreement for prevalence of past 30-day marijuana use than other groups. African-American participants may have underreported marijuana use in the screening item at the beginning of the survey because they were concerned about reporting illegal behavior online. A history of misrepresentation in medical research (Harrison, 2001), coupled with disproportionately high incarceration rates among African-American men (e.g., Pettit & Western, 2004), could lead to mistrust of the substance abuse research setting, even in an anonymous environment. The ethnic differences in reliability of marijuana use found here suggest that anonymous online reports of substance use should include at least two items to accurately evaluate the validity of data, and be embedded in the middle or end of a survey rather than the beginning..

Internal consistency reliability for measures of marijuana cognitions was generally strong. However, marijuana dependence as measured by the CUDIT was less reliable than other measures. This contrasts with previous reports of reliability reports for the CUDIT and CUDIT-R that were each .91 in previous studies (Adamson et al., 2010; Adamson & Sellman, 2003), and could reflect ambivalence toward reporting some marijuana dependence symptoms in a community sample of young adults who may not see marijuana as an addictive substance. A the end of our survey, participants were given a chance to ask questions or make open-ended comments and more than a quarter of past-month marijuana users who chose to do so (28.4% of 331 comments) made a comment negating marijuana’s addiction potential (e.g., “marijuana is not addictive;” “marijuana does not kill, cigarettes do”) or specifically challenged the items assessing cannabis dependence (e.g., “The section about the marijuana use was a bit ridiculous….. Most marijuana smokers that are above the age of 18 are quite responsible in using it…..I don’t think anyone believes that people cannot function without the use of marijuana…”). Further research needs to evaluate the validity of the CUDIT measure in a community sample, as most of the work conducted to date has been with clinical samples of severe substance users (Adamson & Sellman, 2003). Future work could also include other validated screening measures of problematic marijuana use (e.g., Marijuana Screening Inventory; Alexander, 2003) or dependence symptoms (e.g., Marijuana Withdrawal Symptoms Checklist; Budney, Novy, & Hughes, 1999) for comparison.

There were some notable differences between findings reported here and epidemiological data gathered through household interviews. For example, reports of past 30-day marijuana use prevalence were higher in our sample (57%) compared to the 2009 NSDUH reports of past 30 day marijuana use among young adults age 18 to 25 who also used tobacco (34.6%; SAMHSA, 2010a). In addition, marijuana use frequency was not associated with socio-demographic characteristics found to relate to marijuana use in the NSDUH (SAMHSA, 2010b). This is likely reflective of the characteristics of our convenience sample recruited using online advertising and recruitment concentration in areas of the United States that have a relatively high prevalence of marijuana use (e.g., California). The sample obtained through these strategies likely differs from samples recruited through other online means or using other sampling techniques that may be more representative of young adult smokers (Chang & Krosnick, 2009). Further, demographic characteristics of young adult smokers recruited online vary by specific recruitment method (Ramo, Hall, et al., 2010), and social media website use differs by ethnicity and socioeconomic status (Lenhart et al., 2010). The present study made use of multiple recruitment strategies and targeted tobacco and marijuana users who may have a different sociodemographic profile than those who only use marijuana. Post-hoc analyses indicated that the three recruitment sources (Facebook, Craigslist, and SurveySampling International) recruited samples that differed by gender, age, ethnicity, employment status, annual family income, region of residence, and number of days using marijuana in the past 30, consistent with our prior online survey studies (Ramo, Hall, et al., 2010). Those who came from Craigslist used fewer days of marijuana per month than those who came from Facebook (12.9 days vs. 17.1 days, F(2, 880) = 4.00, p = .019. Follow-up analyses examined marijuana prevalence for the three marijuana use items and also agreement among these items by recruitment site. Craigslist demonstrated somewhat lower agreement among marijuana prevalence items (kappas: .68, .73) compared to Facebook (kappas: .84, .83) or Survey Sampling International (kappas: .81, .80), which is consistent with socio-demographic differences in reliability found in this study (e.g., there was a larger proportion of African-American participants recruited through Craigslist; Ramo, Hall, et al., 2010). Online research should consider how recruitment methods may affect both the representativeness of samples and reliability and validity of data gathered.

Construct and concurrent criterion validity were strong for stage of change and abstinence goals, which is consistent with previous tests of the Transtheoretical Model applied to tobacco use (Acton, Prochaska, Kaplan, Small, & Hall, 2001; Prochaska et al., 2004). Further, this model has been applied successfully to multiple health risk behaviors including alcohol and drug use (Heather, Hönekopp, & Smailes, 2009; Prochaska et al., 1994) and the present study is evidence that it can extend to marijuana use among young adults. Future work should test the central tenets of the TTM to demonstrate the full model validity over time in this population.

Relying on self-report, a study limitation is that respondents may not recall their behaviors accurately. However, this is true for face-to-face modes as well. We did not evaluate marijuana quantity of marijuana consumed, as the potency and route of administration of substances such as cannabis vary widely. Thus we can only draw conclusions about the reliability and validity of frequency reports only. Further, the cross-sectional study design limited an examination of test-retest reliability. We were unable to validate our marijuana use data with biological data due to concerns for anonymity, and the current design did not compare face-to-face to online reports of use. However, the comparisons between multiple measures of marijuana use information in our study suggest validity in reports. In addition, attrition was fairly high in that only 52% of the entire eligible sample completed the survey. However, this is consistent with other online survey studies with young adults (e.g., McCabe et al., 2002), and methods of tracking participants beyond what were employed here would have compromised a goal of the research to maintain participant anonymity. Finally, study results may not be generalizable to populations other than young adults who report recent tobacco and marijuana use.

The present study demonstrated the validity and reliability of marijuana use, dependence symptoms, stage of change, and other marijuana-related cognitions reported anonymously online in a national sample of young adults who use tobacco and marijuana. Given that the Internet is so broadly used for surveys of substance use behaviors, it is important to know that the Internet yields valid and reliable data from young people. Further, the consistency in hypothesized patterns among theoretical constructs of the Transtheoretical Model supports the use of stage-tailored interventions to this clinical population. Online stage-tailored interventions with young adults have shown promise in changing health behavior and moving participants toward the action stage of change (e.g., Milan & White, 2010). Findings here underscore the usefulness of these interventions to assist with smoking cessation for young people and support online assessment as a research tool. In addition to being a lower cost method of data collection, the privacy in which research participants can complete assessments may alone reduce social desirability bias from data collection with an interviewer, even in assessments that are not anonymous (e.g., longitudinal or intervention research). Future work should measure social desirability bias and directly compare data gathered confidentially online to data gathered anonymously and through other means (e.g., mail, in-person interviews to better evaluate this. As the Internet is increasingly used for survey research with young adults recruited from online settings other than college email lists (e.g., social networking websites, classified advertising spaces), issues of privacy and non-response bias make it important to evaluate the reliability and validity of online surveys as a research tool. As social media and other public online setting are sources for diverse samples of young adults, rather than limited to those enrolled in colleges, the validity and reliability of data from these sources will ensure this research has maximum impact.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the California Tobacco-Related Diseases Research Program (TRDRP; #18-FT-0055; D. Ramo, P.I). The preparation of this manuscript was supported by an institutional training grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; T32 DA007250; J. Sorenson, P.I.), the NIDA-funded San Francisco Treatment Research Center (P50 DA09253), a career development award from NIDA (K23 DA018691; J. Prochaska, P.I.), and a research project grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH083684, J. Prochaska, P.I.).

The authors wish to thank Sharon Hall for her consultation in the design of the parent study and mentoring of Dr. Ramo. We also thank all the participants in this study.

Footnotes

Danielle E. Ramo, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco. Howard Liu, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco. Judith J. Prochaska, Department of Psychiatry, University of California, San Francisco.

References

- Acton GS, Prochaska JJ, Kaplan AS, Small T, Hall SM. Depression and stages of change for smoking in psychiatric outpatients. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26(5):621–631. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00178-2. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(01)00178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson SJ, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Baker AL, Lewin TJ, Thornton L, Kelly BJ. An improved brief measure of cannabis misuse: The Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test-Revised (CUDIT-R) Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;110(1-2):137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.017. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson SJ, Sellman JD. A prototype screening instrument for cannabis use disorder: the Cannabis Use Disorders Identification Test (CUDIT) in an alcohol-dependent clinical sample. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2003;22:309–315. doi: 10.1080/0959523031000154454. doi: 10.1080/0959523031000154454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology. 2000;19:586–592. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander D. A marijuana screening inventory (experimental version): description and preliminary psychometric properties. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29(3):619–646. doi: 10.1081/ada-120023462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bost ML. A descriptive study of barriers to enrollment in a collegiate health assessment program. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2005;22(1):15–22. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2201_2. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ. Are specific dependence criteria necessary for different substances: how can research on cannabis inform this issue? Addiction. 2006;101(Suppl 1):125–133. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01582.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Novy PL, Hughes JR. Marijuana withdrawal among adults seeking treatment for marijuana dependence. Addiction. 1999;94(9):1311–1322. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94913114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell MA, Lupinacci P. Methodological issues in online data collection. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;60(5):544–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04448.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Krosnick JA. National Surveys Via Rdd Telephone Interviewing Versus the Internet: Comparing Sample Representativeness and Response Quality. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2009;73(4):641–678. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfp075. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(4):284–290. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Humphreys K, Koski-Jannes A, Cordingley J. Internet and paper self-help materials for problem drinking: is there an additive effect? Addict Behav. 2005;30(8):1517–1523. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.03.003. doi: S0306-4603(05)00057-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.03.003 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Humphreys K, Kypri K, van Mierlo T. Formative evaluation and three-month follow-up of an online personalized assessment feedback intervention for problem drinkers. J Med Internet Res. 2006;8(2):e5. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8.2.e5. doi: v8i2e5 [pii] 10.2196/jmir.8.2.e5 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J, McCrae BP, Frank J, Dochnahl A, Pickering T, Harrison B. Identifying male college students’ perceived health needs, barriers to seeking help, and recommendations to help men adopt healthier lifestyles. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48(6):259–267. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596267. doi: 10.1080/07448480009596267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, editor. Alcohol (and illegal drugs) decisional balance scale. Rockville: 1999. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 99-3354. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst S, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, Rossi JS. The process of smoking cessation: An analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(2):295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Martino SC, Collins RL. Marijuana use from adolescence to young adulthood: Multiple developmental trajectories and their associated outcomes. Health Psychology. 2004;23(3):299–307. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.299. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott JC, Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA. Development of a decisional balance scale for young adult marijuana use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25(1):90–100. doi: 10.1037/a0021743. doi: 10.1037/a0021743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin WR, Kruse MI. Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44(5):1497–1504. doi: 10.1037/a0012614. doi: 10.1037/a0012614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Havassy BE, Wasserman DA. Commitment to abstinence and acute stress in relapse to alcohol, opiates, and nicotine. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58(2):175–181. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.2.175. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.58.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Havassy BE, Wasserman DA. Effects of commitment to abstinence, positive moods, stress, and coping on relapse to cocaine use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(4):526–532. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.526. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LD, Martin SS, Enev T, Harrington D. Comparing drug testing and self-report of drug use among youths and young adults in the general population. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2007. DHHS Publication No. SMA 07-4249, Methodology Series M-7. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison RW. Impact of biomedical research on African Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2001;93(3 Suppl):6S–7S. Retrieved from http://nmanet.org/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Hönekopp J, Smailes D. Progressive stage transition does mean getting better: a further test of the Transtheoretical Model in recovery from alcohol problems. Addiction. 2009;104(6):949–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02578.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heishman SJ, Singleton EG, Liguori A. Marijuana Craving Questionnaire: Development and initial validation of a self-report instrument. Addiction. 2001;96(7):1023–1034. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.967102312.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.967102312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA, Douglas EM, Mahmood S. The Effects of Survey Administration on Disclosure Rates to Sensitive Items Among Men: A Comparison of an Internet Panel Sample with a RDD Telephone Sample. Comput Human Behav. 2010;26(6):1327–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.04.006. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings, 2010. Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Khadjesari Z, Murray E, Kalaitzaki E, White IR, McCambridge J, Godfrey C. Test-retest reliability of an online measure of past week alcohol consumption (the TOTAL), and comparison with face-to-face interview. Addict Behav. 2009;34(4):337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.010. doi: S0306-4603(08)00310-9 [pii] 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.010 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koski-Jannes A, Cunningham J, Tolonen K. Self-assessment of drinking on the Internet--3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44(3):301–305. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn124. doi: agn124 [pii] 10.1093/alcalc/agn124 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Neighbors C, Hendershot CS, Grossbard JR. Development and preliminary validation of a comprehensive marijuana motives questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70(2):279–287. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.279. Retrieved from http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Neighbors C, Kilmer JR, Larimer ME. A brief, web-based personalized feedback selective intervention for college student marijuana use: a randomized clinical trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(2):265–273. doi: 10.1037/a0018859. doi: 10.1037/a0018859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A, Purcell K, Smith A, Zickuhr K, Project PIAL. Social media and young adults. Pew Research Center; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lord S, Brevard J, Budman S. Connecting to young adults: an online social network survey of beliefs and attitudes associated with prescription opioid misuse among college students. Substance Use and Misuse. 2011;46(1):66–76. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521371. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Couper MP, Crawford S, D’Arcy H. Mode effects for collecting alcohol and other drug use data: Web and U.S. mail. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(6):755–761. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.755. Retrieved from http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, Diez A, Boyd CJ, Nelson TF, Weitzman ER. Comparing web and mail responses in a mixed mode survey in college alcohol use research. Addict Behav. 2006;31(9):1619–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.009. doi: S0306-4603(05)00302-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.009 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan JE, White AA. Impact of a stage-tailored, web-based intervention on folic acid-containing multivitamin use by college women. Am J Health Promot. 2010;24(6):388–395. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.071231143. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.071231143 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ET, Neal DJ, Roberts LJ, Baer JS, Cressler SO, Metrik J. Test-retest reliability of alcohol measures: Is there a difference between Internet-based assessment and traditional methods? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16(1):56–63. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.16.1.56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MG, MacPherson L, McCarthy DM, Brown SA. Constructing a short form of the Smoking Consequences Questionnaire with adolescents and young adults. Psychological Assessment. 2003;15(2):163–172. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.2.163. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.15.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MG, Stice E, Wagner EF. Cross-validation of the Temptation Coping Questionnaire: adolescent coping with temptations to use alcohol and illicit drugs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60(5):712–718. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.712. Retrieved from http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer BW, Cassidy EL, Dunn LB, Spira AP, Sheikh JI. Effective use of consent forms and interactive questions in the consent process. IRB; A Review of Human Subjects Research. 2008;30(2):8–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit B, Western B. Mass Imprisonment and the Life Course: Race and Class Inequality in U.S. Incarceration. American Sociological Review. 2004;69(2):151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Postel MG, de Haan HA, ter Huurne ED, Becker ES, de Jong CA. Effectiveness of a web-based intervention for problem drinkers and reasons for dropout: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(4):e68. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1642. doi: v12i4e68 [pii] 10.2196/jmir.1642 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JJ, Rossi JS, Redding CA, Rosen AB, Tsoh JY, Humfleet GL. Depressed smokers and stage of change: Implications for treatment interventions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76(2):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.017. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change for smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51(3):390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, Goldstein MG, Marcus BH, Rakowski W. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychology. 1994;13(1):39–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.39. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.13.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Reaching young adult smokers through the Internet: Comparison of three recruitment mechanisms. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(7):768–775. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq086. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Reliability and validity of self-reported smoking in an anonymous online survey with young adults. Health Psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0023443. Retrieved from doi:10.1037/a0023443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramo DE, Prochaska JJ, Myers MG. Intentions to quit smoking among youth in substance abuse treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;106(1):48–51. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.004. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Bowie DA, Hergenrather KC. Collecting behavioural data using the world wide web: considerations for researchers. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health. 2003;57(1):68–73. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.1.68. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohsenow DJ, Colby SM, Martin RA, Monti PM. Nicotine and other substance interaction expectancies questionnaire: Relationship of expectancies to substance use. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(4):629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.01.001. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RTI International . 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: CAI Specifications for Programming English Version. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville MD: 2006. Contract No. 283-2004-00022. [Google Scholar]

- Schonlau M, Zapert K, L.P. S, Sansad KH, Marcus SM, Adams J. A comparison between responses from a propensity-weighted web survey and an identical RDD survey. Social Science Computer Review. 2004;22(1):128–138. doi: 10.1177/0894439303256551. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Simone S, Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. samples. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(2):393–398. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825023. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow MG, Prochaska JO, Rossi JS. Process of change in alcoholics anonymous: Maintenance factors in long-term sobriety. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55(3):362–371. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.362. Retrieved from http://www.jsad.com/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A calendar method for assessing alcohol and drug use. Addiction Research Foundation; Toronto, Canada: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Spijkerman R, Knibbe R, Knoops K, Van De Mheen D, Van Den Eijnden R. The utility of online panel surveys versus computer-assisted interviews in obtaining substance-use prevalence estimates in the Netherlands. Addiction. 2009;104(10):1641–1645. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02642.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . The NSDUH Report: Daily Marijuana Users. SAMHSA; Rockville, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Detailed Data Table 6.9B - Types of illicit drug use in the past month among persons aged 18 to 25, by Past Month Cigarettes Use: Percentages, 2008 and 2009. 2010a from http://oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k9NSDUH/tabs/Sect6peTabs1to54.htm#Tab6.9B (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/61JD75glb)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume I. Summary of National Findings. Office of Applied Studies; Rockville, MD: 2010b. NSDUH Series H-38A, HHS Publication No. SMA 10-4856Findings. [Google Scholar]

- Sumnall HR, Measham F, Brandt SD, Cole JC. Salvia divinorum use and phenomenology: results from an online survey. Journal of Psychoparmacology. doi: 10.1177/0269881110385596. in press. doi: 10.1177/0269881110385596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census Bureau Census Regions and Division of the United States. 2010 Retrieved Februrary 4, 2010, from http://www.census.gov/geo/www/us_regdiv.pdf (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/61JDxeR2e)

- Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Brandenberg N. A decisional balance measure for assessing and predicting smoking status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;48(5):1279–1289. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.48.5.1279. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.48.5.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, DiClemente CC, Rossi JS, Prochaska JO. Relapse situations and self-efficacy: An integrative model. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15(3):271–283. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90070-e. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90070-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, Kavanagh D, Stallman H, Klein B, Kay-Lambkin F, Proudfoot J. Online alcohol interventions: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(5):e62. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1479. doi: v12i5e62 [pii] 10.2196/jmir.1479 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]