Abstract

Objective: Social support is an important element of family medicine within a primary care setting, delivered by general practitioners and practice nurses in addition to usual clinical care. The aim of the study was to explore general practitioner’s, practice nurse’s and people with type 2 diabetes’ views, experiences and perspectives of the importance of social support in caring for people with type 2 diabetes and their role in providing social support.

Methods: Interviews with general practitioners (n=10) and focus groups with practice nurses (n=10) and people with diabetes (n=9). All data were audio-recorded, fully transcribed and thematically analysed using qualitative content analysis by Mayring.

Results: All participants emphasized the importance of the concept of social support and its impacts on well-being of people with type 2 diabetes. Social support is perceived helpful for people with diabetes in order to improve diabetes control and give support for changes in lifestyle habits (physical activity and dietary changes). General practitioners identified a lack of information about facilities in the community like sports or self-help groups. Practice nurses emphasized that they need more training, such as in dietary counselling.

Conclusions: Social support given by general practitioners and practice nurses plays a crucial role for people with type 2 diabetes and is an additional component of social care. However there is a need for an increased awareness by general practitioners and practice nurses about the influence social support could have on the individual’s diabetes management.

Keywords: social support, type 2 diabetes, qualitative approach, primary health care

Abstract

Zielsetzung: Soziale Unterstützung stellt ein wichtiges und ergänzendes Element in der hausärztlichen Versorgung dar. In der vorliegende Studie wurden die Einstellungen zu und Erfahrungen mit sozialer Unterstützung sowie deren Bedeutung im hausärztlichen Setting von Allgemeinärzten, Medizinischen Fachangestellten (MFA) und Patienten mit Diabetes mellitus Typ 2 erfasst.

Methodik: Es wurden Interviews mit Allgemeinärzten (n=10) sowie Fokusgruppen mit MFAs (n=10) und Patienten mit Diabetes mellitus Typ 2 (n=9) durchgeführt. Die Daten wurden aufgezeichnet, transkribiert und thematisch unter Verwendung der qualitativen Inhaltsanalyse nach Mayring analysiert.

Ergebnisse: Alle Teilnehmer betonen die Relevanz des Konzepts der sozialen Unterstützung und vor allem den daraus resultierenden Einfluss auf das Wohlbefinden von Patienten mit Diabetes mellitus Typ 2. Soziale Unterstützung wird von den befragten Patienten als hilfreiches Konzept empfunden, um die eigenen Werte zu verbessern und um Lebensstilveränderungen umzusetzen (körperliche Aktivität oder Ernährungsumstellung). Allgemeinärzte nehmen ihrerseits einen Mangel an Informationen über kommunale Angebote wie zum Beispiel Sportkurse oder auch Selbsthilfegruppen wahr. MFAs wünschen sich mehr Fortbildungsmöglichkeiten, um in der Praxis zum Beispiel Ernährungsberatung durchführen zu können.

Fazit: Soziale Unterstützung durch Praxisteams in der hausärztlichen Versorgung spielt eine wichtige Rolle für Patienten mit Diabetes mellitus Typ 2. Allerdings sollten sich sowohl Allgemeinärzte als auch MFAs noch mehr darüber bewusst werden, welchen Einfluss und Nutzen soziale Unterstützung auf das individuelle Diabetesmanagement haben kann.

Introduction

Social support is an important element of family medicine within a primary care setting, delivered by general practitioners and practice nurses in addition to usual clinical care. Moreover, it is one core element within the definition of family medicine published by the German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians [1]. For many patients with chronic, severe or unstable conditions, their chosen primary care team is only one participant in the delivery of their care as other institutions, such as in-patient or community care settings act as a network of care providers. Social support refers to support given to an individual as part of a social network. It plays a key role in holistic and patient centred approaches to primary care such as the Chronic Care Model, Year of Care, and Medical Home [2], [3], [4]. Social support should be derived from different sources. Social care consists of different elements, including emotional-, esteem- and network support [5] or tangible-, emotional- or informational support [6]. An overview of the theoretical background to this concept has been described by Berkman et al. [7]. There are two main complementary but different definitions of social support. First, structural support refers to support through a social network like family members, community members or the primary care team [7]. Second, functional support such as emotional or informational support enhances the well-being of patients [7]. A current approach of social support emphasizes the multidimensionality of this concept and made a distinction between perceived available social support and actually received social support [8]. Both aspects are subjective interpretations. Furthermore, four components are relevant if considering the concept of social support: need for support, mobilization of support, protective buffering and actually provided social support [8]. Beside these different approaches good social support has been found to have positive effects on patients’ well-being [6], [7]. However, negative effects of social support like criticism, disappointment or overinvolvement are also described [9].

Several studies have shown the beneficial effect of social support in patients with chronic illness, especially in relation to health status or health outcomes [10], [11], [12]. However, “positive health outcomes are achieved only when the people affected as well as their families, community supporters, and healthcare teams are informed, motivated, prepared, and willing to work together” [10]. For example, several studies have shown positive effects on mortality and psychosocial stress in people with type 2 diabetes [11], [12].

Practice nurses increasingly deliver important aspects of care for people with diabetes [13], [14]. In people with type 2 diabetes with poor glycaemic control, regular telephone monitoring can improve medical outcomes like A1C and self-care activities [13]. These elements form part of the therapeutic relationship between patients and clinicians, which also includes personal support and information sharing. These can fit into elements of self-care management [15]. The core focus of social support given by primary care teams relates to lifestyle advice about physical activity, nutrition behaviour or changing lifestyle behaviours [16]. However the primary care team should also be aware of other sources, such as sports and leisure facilities, within the community [17] beyond the care delivered in the practice.

In summary, the role, importance and impact of general practitioners and practice nurses within the network of social support needs to be defined as an important element to support care of patients with chronic diseases. More information is needed how primary care teams understand the concept of social support for patient’s care and counselling.

It is important to evaluate the understanding of the concept of social support for primary care in consideration of the subjective motives, attitudes and needs of primary care teams and patients. A qualitative approach provided to get a deeper insight in these different subjective viewpoints. Therefore, the aim of the study was to explore general practitioner’s, practice nurse’s and people with type 2 diabetes’ views, experiences and perspectives of the importance of social support in caring for people with type 2 diabetes and their role in providing social support. To include the different subjective viewpoints of all participants a qualitative study was chosen.

Methods

Interviews with general practitioners (GP), and two focus groups with practice nurses and people with type 2 diabetes respectively were performed regarding to the criteria for qualitative studies [18]. The study design was chosen to allow an intensive analysis of subjective motives, attitudes and needs of participants. Qualitative methods can supply a greater depth of information about a particular research setting and permit the generation of hypotheses for further research with quantitative methods. To increase the understanding of subjective motives, attitudes and needs a triangulation of qualitative methods was used. An integration of focus groups and individual interview data was obtained. This approach – the combination of individual interviews and focus groups – might be useful for identification of the individual and contextual circumstances and enhances data richness [19]. An additional strength of the qualitative approach for this study is the chance to obtain a more realistic view on experiences and perspectives of the importance of social support in caring for people with type 2 diabetes and the role of GPs and practice nurses in providing this kind of support. All quotations have been chosen on grounds of representativeness.

Recruitment and sample

Practising GPs with a work experience of at least 5 years were recruited from a quality circle in the surrounding area of Stuttgart (Germany). Quality circles were based on meetings in small groups of physicians to improve performance in patient care. From the addressed quality circle all 10 GPs participated on the study. The practice nurses were recruited from the same practices as the participating GPs. Thereby, each practice nurse was from a different practice. All 10 practices nurses were addressed by GP. We had no influence on the selection of the practice nurses. People with type 2 diabetes were eligible for the focus group if they had sufficient knowledge of the German language, were more than 18 years old and had a poor glycaemic control, indicated by glycated haemoglobin (HbA1C) >7.5%. Patients were randomly selected from the computer files of participating practices. Therefore, we had no influence on the selection of patients. During a consultation in the practice the GP asked these patients whether they would be willing to participate in one focus group. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

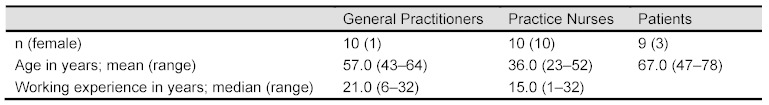

A sample of 10 GPs, 10 practice nurses and 9 people with type 2 diabetes was recruited. The mean age (range) of GPs, practice nurses and patients was 57 (43–64), 36 (23–52) and 67 (47–78) years, respectively (Table 1 (Tab. 1)). Work experience among general practitioners ranged from 6-32 years with a median of 21.0 years and from 1–32 years (median: 15.0) among practice nurses, respectively. No more quantitative information of participants was evaluated.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study sample.

Design and data collection

Interviews and focus groups were conducted from March to June 2008. Practice nurses and patients received a reimbursement of 50 € for participation in the focus groups. Practice nurses’ and patients’ focus groups took place in the practice of one participating GP. For the focus groups the sample of participating practice nurses and patients were each divided into two groups according to time preferences. All together four focus groups met at any one time. Each GP was interviewed once in his or her own practice. Focus groups and interviews were conducted by the first author. Individual appointments for the interviews and focus groups were arranged by telephone. On average, GP interviews lasted 60 minutes and focus groups lasted 90 minutes. The first, the sixth and the seventh author, constructed the semi-structured guidelines for the interviews and the focus groups. In order to ensure comparability between groups, we asked the same questions to all of them, interviews and focus groups:

What does social support in a primary care setting mean to you?

Which are the main barriers and problems in offering social support?

What could be important for diabetes patients to get more social support in primary care settings?

The aims of the study were explained to each participant. The interviewer ensured that each aspect of these questions was explained sufficiently, so that no questions or misunderstandings remained.

Data analysis

The 10 interviews and four focus groups were recorded digitally, fully transcribed and analysed separately by the first and last author with ATLAS.ti-Software [20]. Key issues were identified, summarized, labelled as codes and sorted into main and sub-categories based on the qualitative content analysis by P. Mayring [21] through the first and last author. Qualitative content analysis means an inductive development of categories and a deductive application of categories [21]. According to the rules of the qualitative content analysis the categories were developed near to the original material. A quotation was used to illustrate each of the categories [22]. The same approaches of analyses were done for interviews and focus groups, respectively. The first and the last author independently reviewed transcripts and developed categories to confirm that the codes were comprehensive and reproducible. The categorising system was consequently modified and disagreements during the process were discussed until a consensus was achieved. However, no inter-rater reliability was determined. The codes were clearly defined and linked with representative examples from the original text. The quotations cited here were translated by the first author from German into English and cross-checked by the last author.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Heidelberg (Germany); approval number S-031/2008.

Results

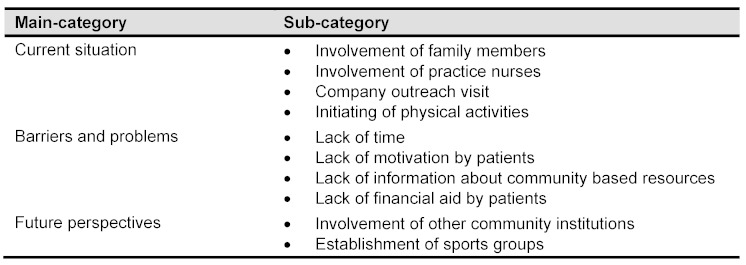

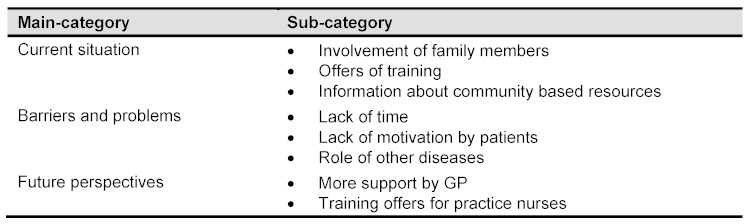

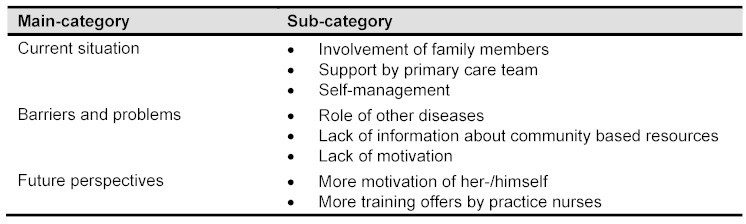

Analyses of the interviews and focus groups identified three main categories of social support: “current situation”, “barriers and problems”, “future perspectives”. For the corresponding sub-categories of general practitioners (GP) see Table 2 (Tab. 2), for practice nurses (PN) see Table 3 (Tab. 3), and for patients (P) see Table 4 (Tab. 4) respectively.

Table 2. Social support – perspective of GPs.

Table 3. Social support – perspective of practice nurses.

Table 4. Social support – perspective of patients.

Current situation

The following sub-categories were defined for the main category “current situation”.

The current level of social support offered by doctors and the importance associated with it differed within the group of GPs. Lots of activities were already being done by GPs such as inviting patients to a physical activity group or offering of nutritional education.

The majority of GPs stated that for most patients family members are the essential source of social support and as such they attempt to integrate family members in to patient care. Furthermore, GPs emphasized the role of practice nurses in supporting elderly people with type 2 diabetes. Moreover for patients, practice nurses are important sources for social support.

Well, I believe that the practice nurses are good for these patients because they often work for many years in the practice and have developed an intensive relationship with the patients. (GP06, male)

Regarding the workplace conditions of people with diabetes two GPs try to inform the company physician about the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and associated problems.

Sometimes I contacted the company physician at the patients’ workplace. If a patient is shift working, I asked, for example, to change the workplace because the meal time of this patient is irregular or something like that. (GP02, male)

Four out of the 10 GPs had initiated a sports or walking group for their patients generally. The initiating of physical activities was perceived as a special form of social support and was an optional activity done by the GP.

I manage a sports group which I established five years ago. It is a huge success. (GP09, male)

Most of the practice nurses reported that they play an important role in the provision of social support to patients. Besides offering regular and ongoing care to patients, nurses often invited the patients’ family members (wives or husbands) to join consultations. The involvement of family members is one main aspect of supporting these people.

Often we invite the wives of patients with diabetes because they are responsible for the diet. (PN05, female)

Nurses reported offering education to people with diabetes and providing information to patients about community based resources; for example, a weekly special service for people with diabetes. This is a special offer in one primary care practice for people with diabetes.

Well, on Tuesday we have a special day for people with diabetes. We measure blood pressure and glucose and look after the values. They have the possibility to ask us more questions. (PN05, female)

All participating patients demanded and accepted different levels of social support. The majority reported that they receive support from their families, others by their primary care team. Many patients said that their spouse or other family members are their primary source of social support; for example, in reminding them to take their tablets or cooking healthy meals.

My wife makes sure, that I take my tablets regularly. (P05, male)

The second source of social support identified by patients was their GP or practice nurse.

I’m alone. My wife is dead. I have my physician and I have to take care of my own. (P04, male)

The practice nurse of the general practitioner helps me to inject myself. (P05, male)

Two out of the 9 patients stated that they do not need social support from anybody, including family members, because they can manage their disease alone.

Well, I handle my illness alone. I do not stress my husband. (P07, female)

Barriers and problems

The following sub-categories were defined for the main category “barriers and problems”. GPs identified two main barriers for providing social support to patients. Firstly, a lack of time within normal consultations and secondly a lack of motivation by patients were mentioned.

I do not have enough time. (GP 05, male)

When I visit a patient with diabetes at home and I find him in front of the television with chocolate, I’m frustrated. (GP03, male)

The majority of GPs also acknowledged that they did not know enough about community based resources in their area.

There are two or three sports groups for seniors but not for diabetes people. But I do not know exactly because I do not live in this place. (GP01, female)

Another barrier identified by GPs was the inability of patients to pay for recommended activities that provide social support such as to work out at a gym. Patients should be aware of their own reflexivity. Promoting this process could be seen as social support. Therefore ideas recommended by GPs could not be carried out by patients even if they were motivated to do so.

Well, I believe they need social support because often the patient argues that they do not have money to buy fruit or vegetable regularly. (GP03, male)

Practice nurses identified the same problems and barriers for giving social support to patients as the GPs in the study, focusing on time constraints and perceived deficits in patient motivation which were regarded as frustrating.

The focus is not on the patient now. I have more work which refers to paperwork than to patients. (PN01, female)

It seems to be, that people with diabetes sometimes are not motivated enough to change their own lifestyle.

Sometimes I am frustrated. For many years, I said to the patients that they must change their nutrition, but nothing has happened. (PN05, female)

In addition, practice nurses described problems with some patients regarding physical activity due to chronic and often multiple conditions.

Well, the elderly persons are not able to change it. They have osteoarthritis or other hip troubles which are problematic for participating in sports groups. (PN01, female)

Therefore, recommendations and information made by practice nurses in terms of social support, like participation in sports groups could not be realized easily by patients.

Patients identified two main barriers for social support. First, chronically ill people have often more than one disease.

I can not move anymore because I have problems with my musculoskeletal system. (P07, female)

The patients echoed some of the statements of the nurses, e.g. that their comorbidities make any engagement within community based resources like sports groups problematical. Some patients also stated that information about local community resources was often unavailable.

I have never heard about community based resources. (P02, female)

Some patients have no interest in community based resources. Finally, some patients had the attitude that the GP is the only person who can support them.

Future perspectives

The following sub-categories were defined for the main category “future perspectives”. Statements about the future role and importance of social support in primary care differed between the three groups. The GPs argued that the involvement of other community institutions other than general practice staff is more important in supporting elderly people with diabetes. However, one GP stated that he would try to establish a sports group.

I will try to establish a sports group particular for multimorbid patients not just for diabetes or coronary patients. (GP07, male)

All the practice nurses stated that they needed more support from the GP and more training for this group of patients.

I need more training for treating these patients. (PN01, female)

Four out of the nine patients recognized their lack of self motivation and argued that they need more counselling about nutrition or physical activity, preferably in small group sessions.

Well, there are so many people there. It will be better for me in small groups because the conversation could be more personal and it will be easier to contact the counsellor. (P09, male)

Discussion

The results of this qualitative study point out that social care and social support are relevant aspects to support the care of people with chronic conditions. There are a number of activities which are already carried out by GPs and practice nurses regarding social support but barriers could prohibit optimal care; barriers include the workload of GPs and practice nurses, and the lack of motivation or resources by patients on their own. Practice nurses were often found to be a main source of integrating family members in the treatment of these people. This echoes the fact that teaching, counselling and education form a key role of nursing care [23]. Furthermore, an additional offer is mentioned by one practice nurse which was called ‘special day for people with diabetes’. This concept means more than medical care but also that practice nurses could be more involved in offering care and support by these people to achieve an improved self-management [24].

Furthermore, advice and education given in general practice, are important components of diabetes management [25]. From the results of this study it may be assumed that GPs and practice nurses do advise people with diabetes to increase their exercise and improve their diet. However, patients do not always adhere to lifestyle advice to change their diet or physical activity habits. The fact that social support is not generally regarded as being education and treatment, but rather does occur during these activities needs more emphasis within GP training.

Recommended levels of physical activity are important for improving outcomes [26], [27], such as mortality, in people with diabetes [28] as well as blood glucose levels [27]. This suggests the need for people with type 2 diabetes to be offered social support in the form of education and training to change their lifestyle behaviours. Furthermore, it could be assumed that they need assistance in improving their knowledge of existing community based activities related to their disease and advice about how to access these activities best. As a consequence these people might achieve a better diabetes control.

Berkman et al. [7] emphasized in their theoretical concept of social support that emotional support in addition to network support makes an important contribution to a person’s well-being. Primary care providers play an important role in encouraging patients to improve their quality of life and well-being. Results from a cross-sectional survey confirmed the importance of psychosocial strategies and the positive effect on patient’s care [29]. In our study participants stated that the availability of helpful social support is an important essential element of social care. This includes more than support from family and friends. Social care means support from the GP and practice nurse as well as from the community, training centres or other institutions. GPs should treat patients with a holistic approach like specified in Chronic Care Model, Medical Home or Year of Care [2], [3], [4]. This comprises knowing the patient and his social background, having a relationship over time and offering social support in terms of social care [30].

However, the effectiveness of social support depends on patients’ motivation and the possibility of self-management. Self-care, any activity with the intention of improving health, treating or preventing diseases, provides a significant health resource for people with chronic conditions [31]. Some people with diabetes in our sample stated that they do not need any social support. One reason therefore could be that their level of self-management is sufficient for their own needs. Further research is needed to identify how diabetes care is able to meet the individual demand of the level of social support. Different studies showed the positive impact of self-care on patients’ well-being [32]. In terms of self-motivation from the patients’ point of view, patients need support from the GPs and also from practice nurses. GPs as well as practice nurses are able to give social support as an additional aspect of social care, supported by community based resources and the lack about the state of knowledge by themselves. However, this is an additional element which is given by the primary care team. Therefore, people with chronic conditions need support from other institutions in the community like sports clubs or self help groups as a kind of social contact [17]. However, there is no evidence whether community activities improve diabetes control. GPs and practice nurses need more information about where to send patients to and which community based programs or other sources of social support were established within their area. Furthermore, GPs and practice nurses should be motivated by themselves to update their level of information regularly.

According to the demographic trend the prevalence of diabetes and other chronic conditions is increasing in Germany as well as in all industrialized countries; improving quality of care for these conditions is a major challenge for health care systems throughout the world. GPs play a crucial role in conducting and coordinating care for patients. The integration of community based resources within diabetes care is one core element of the Chronic Care Model and a main element within coordination of care [2], [33]. Equally the Medical Home approach and the Year of Care Model consider for individual care and coordination of different elements of care that medical providers work together within a health care team [2], [3]. The intended purpose of these three holistic care approaches is the optimization of patients’ well-being, quality of life and the efficient use of healthcare resources. According to the results of this study it could be assumed that GPs are aware of the importance of social support and the use of community resources, but are also aware of deficits and barriers.

Social support is an important aspect in primary care settings. The qualitative statements showed that there is a need for focussing on the association between social support as a kind of social care and primary care team members as specific persons in practising social care which should be reviewed by quantitative methods. However, it is important to consider several aspects within care as improving quality of life and controlling risk for severe complications if the aim is an individualized care of people with diabetes [16], [34].

The “three-in-one” design allows the consideration of different viewpoints including beside the primary care team also the perspective of people with type 2 diabetes. The patients’ perspective is often missing in studies about the importance of social support, so the qualitative approach of this study makes a worthwhile contribution to develop further research questions.

Study limitations

The findings of the current study must be viewed under the specific quality criteria in qualitative research. Some limitations have to be considered, when interpreting the results. The study was undertaken in only one region of Germany and only included GPs that were participants in one quality circle, which may have resulted in selection bias of superior motivation within our sample. As usual in qualitative studies the sample size is not intended to achieve representativity. However the data suggests the importance of social support in diabetes care and contributes to the development of hypotheses for further quantitative research, as representative studies should be used to distinguish the actual needs. Furthermore, we collected no information about the financial situation of the patients. Therefore, a selection bias concerning the 50 € reimbursement could not be excluded. The results of this qualitative study are not generalizable but are important for the generation of ideas and hypotheses as it is the purpose of qualitative research in general. We used a triangulation of qualitative methods which includes an additional challenge in interpretation of the data. However, this is a good opportunity to achieve a more comprehensive view of subjective knowledge and attitude to the concept of social support.

Conclusions and relevance to clinical practice

This current study accentuates the importance and role of social support in primary care settings by GPs and practice nurses. Furthermore, the perspective of people with type 2 diabetes was evaluated and showed also that not all of them need social support. Further research is needed to answer the question which kind of patients do not like social support at all and if these patients have a sufficient self-management so that social support is not needed from the physicians’ point of view too. This leads to a deeper understanding of patients needs. Social support is a core component of high quality chronic disease management to improve patient outcomes. The main barriers and problems in offering social support are a lack of information, motivation by patients and primary care staff, and a lack of time for primary care providers. Further research will be needed to determine how to overcome these barriers and problems. GPs should treat patients from a holistic approach and should therefore know about important parts of their patients’ social life. This knowledge might have essential impact on the improvement of diabetes management with respect to concepts of care offered by the GPs and the well-being of the patients. An essential source of social support regarding elements of teaching, counselling and education is the involvement of practice nurses. Moreover, the cooperation within primary care teams and furthermore the cooperation with further health care providers might be useful for an improvement of the health status of people with type 2 diabetes. This study represents a foundation for further research concerning the definition and implementation of social support within chronic illness care.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the physicians and practice nurses who participated in this study.

Funding

This study was founded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (approval number 01GX0746).

References

- 1.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin (DEGAM) Fachdefinition. DEGAM; 2012. [cited 2012 March 14]. Available from: http://www.degam.de/index.php?id=303. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002 Oct 9;288(14):1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenthal TC. The medical home: growing evidence to support a new approach to primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008 Sep-Oct;21(5):427–440. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070287. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.School for Health at Durham University. Year of Care: Online Resources. [cited 2011 August 2]. Available from: http://www.researchoption.co.uk/hostpage.aspx?hid=XNTkJg+sSUx7eiD2fZGXTA==&pd=G2ZvQDa+p3cSSRBaJRv/LA==

- 5.Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med. 1976 Sep-Oct;38(5):300–314. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaefer C, Coyne JC, Lazarus RS. The health-related functions of social support. J Behav Med. 1981 Dec;4(4):381–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00846149. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00846149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000 Sep;51(6):843–857. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schulz U, Schwarzer R. Soziale Unterstützung bei der Krankheitsbewältigung: Die Berliner Social Support Skalen (BSSS) Diagnostica. 2003;49:73–82. doi: 10.1026//0012-1924.49.2.73. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1026//0012-1924.49.2.73. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laireiter AR, Fuchs M, Pichler ME. Negative Soziale Unterstützung bei der Bewältigung von Lebensbelastungen. [Negative social support in the adaption to life stress: a conceptual and empirical analysis]. Zeitschrift für Gesundheitspsychologie. 2007;15(2):43–56. doi: 10.1026/0943-8149.15.2.43. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1026/0943-8149.15.2.43. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pruitt S, Epping-Jordan JA. Preparing a global healthcare workforce for the challenge of chronic conditions. Diabetes Voice. 2008;53:38–41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Norris SL, Gregg EW, Beckles G. Social support and mortality among older persons with diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2007 Mar-Apr;33(2):273–281. doi: 10.1177/0145721707299265. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0145721707299265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herpertz S, Johann B, Lichtblau K, Stadtbäumer M, Kocnar M, Krämer-Paust R, Paust R, Heinemann H, Senf W. Patienten mit Diabetes mellitus: psychosoziale Belastung und Inanspruchnahme von psychosozialen Angeboten. Eine multizentrische Studie. [Patients with diabetes mellitus: psychosocial stress and use of psychosocial support: a multicenter study]. Med Klin (Munich) 2000 Jul 15;95(7):369–377. doi: 10.1007/s000630050014. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s000630050014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor CB, Miller NH, Reilly KR, Greenwald G, Cunning D, Deeter A, Abascal L. Evaluation of a nurse-care management system to improve outcomes in patients with complicated diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003 Apr;26(4):1058–1063. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1058. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.4.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dale J, Caramlau I, Docherty A, Sturt J, Hearnshaw H. Telecare motivational interviewing for diabetes patient education and support: a randomised controlled trial based in primary care comparing nurse and peer supporter delivery. Trials. 2007;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-18. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorne SE, Paterson BL. Health care professional support for self-care management in chronic illness: insights from diabetes research. Patient Educ Couns. 2001 Jan;42(1):81–90. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(00)00095-1. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(00)00095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saatci E, Tahmiscioglu G, Bozdemir N, Akpinar E, Ozcan S, Kurdak H. The well-being and treatment satisfaction of diabetic patients in primary care. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:67. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-67. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boelter R, Natanzon I, Miksch A, Joos S, Rosemann T, Szecsenyi J, Goetz K. Kommunale Ressourcen als ein Element des „Chronic care Modells“. Eine qualitative Studie mit Hausärzten. [Communal resources as one element of the chronic care model. A qualitative study with general practitioners]. Praev Gesundheitsf. 2009;4(1):35–40. doi: 10.1007/s11553-008-0151-z. (Ger). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11553-008-0151-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007 Dec;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambert SD, Loiselle CG. Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. J Adv Nurs. 2008 Apr;62(2):228–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04559.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muhr T. ATLAS.ti 5.0 – the Knowledge Workbench Scientific Software. 2nd ed. Berlin: Scientific Software Development; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayring P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken [Qualitative content analysis. Basics and techniques] Weinheim: Beltz; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krippendorff K. Content analysis. An introduction to its methodology. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mattila E, Leino K, Paavilainen E, ?stedt-Kurki P. Nursing intervention studies on patients and family members: a systematic literature review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2009;23(3):611–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00652.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwall LL, Danielson E, Ohrn I. The meaning of a consultation with the diabetes nurse specialist. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010 Jun;24(2):341–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00726.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nield L, Summerbell CD, Hooper L, Whittaker V, Moore H. Dietary advice for the prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD005102. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005102.pub2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005102.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirk A, Mutrie N, MacIntyre P, Fisher M. Increasing physical activity in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003 Apr;26(4):1186–1192. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1186. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.4.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green AJ, Bazata DD, Fox KM, Grandy S. Health-related behaviours of people with diabetes and those with cardiometabolic risk factors: results from SHIELD. Int J Clin Pract. 2007 Nov;61(11):1791–1797. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01588.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Shaw J. Global and societal implications of the diabetes epidemic. Nature. 2001 Dec 13;414(6865):782–787. doi: 10.1038/414782a. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/414782a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Siminerio LM. Physician and nurse use of psychosocial strategies in diabetes care: results of the cross-national Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) study. Diabetes Care. 2006 Jun;29(6):1256–1262. doi: 10.2337/dc05-2444. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2337/dc05-2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu C, Phillips WR, Sherman KJ, Hawkes R, Cherkin DC. Healing in primary care: a vision shared by patients, physicians, nurses, and clinical staff. Ann Fam Med. 2008 Jul-Aug;6(4):307–314. doi: 10.1370/afm.838. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1370/afm.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Høy B, Wagner L, Hall EO. Self-care as a health resource of elders: an integrative review of the concept. Scand J Caring Sci. 2007 Dec;21(4):456–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00491.x. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Dam HA, van der Horst F, van den Borne B, Ryckman R, Crebolder H. Provider-patient interaction in diabetes care: effects on patient self-care and outcomes. A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2003 Sep;51(1):17–28. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00122-2. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(02)00122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Epping-Jordan JE, Pruitt SD, Bengoa R, Wagner EH. Improving the quality of health care for chronic conditions. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004 Aug;13(4):299–305. doi: 10.1136/qhc.13.4.299. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/qhc.13.4.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miksch A, Hermann K, Rölz A, Joos S, Szecsenyi J, Ose D, Rosemann T. Additional impact of concomitant hypertension and osteoarthritis on quality of life among patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care in Germany – a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009 Feb 27;7:19. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-19. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]