Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To determine if the effect of sertraline in the Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease Study – 2 (DIADS-2) differed in subgroups of patients defined by baseline depression criteria.

METHODS

DIADS-2 was a randomized, parallel, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial designed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sertraline (target dose of 100mg/day) for the treatment of depression in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. DIADS-2 enrolled 131 patients who met criteria for depression of Alzheimer’s disease (dAD). Analyses reported here examined if the effect of sertraline differed in various subgroups, including those meeting criteria for major depressive episode (MaD), minor depressive episode (MiD) and Alzheimer’s-associated affective disorder (AAAD) at baseline.

RESULTS

At baseline, 52 of 131 participants (39.7%) met criteria for MaD, 54 (41.2%) for MiD and 90 (68.7%) for AAAD. For the primary outcome of modified Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Clinical Global Impression of Change (mADCS-CGIC) scores at 12 weeks of follow-up, the odds of being at or better than a given mADCS-CGIC category did not significantly differ between the two treatment groups for those patients with MaD at baseline (ORsertraline = 0.66 [95% CI: 0.24, 1.82], p = 0.42); tests for interactions between treatment group and baseline depression diagnostic subgroup were not significant for MaD vs. MiD vs. neither (χ2 = 1.05 (2df), p = 0.59) or AAAD vs. no AAAD (χ2 = 0.06 (1df), p = 0.81).

CONCLUSIONS

There was no evidence that sertraline treatment was more efficacious in those patients meeting baseline criteria for MaD compared to MiD or to neither.

Trial registration

clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00086138

Keywords: Alzheimer’s dementia, sertraline, depression, randomized trial

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a devastating disease whose characteristic features are progressive neurodegeneration and deterioration of cognitive and functional abilities. Some form of neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) such as agitation, depression, apathy, delusions or hallucinations are almost universal in patients with AD (Lyketsos et al. 2002; Steinberg et al. 2008). In particular, depressive symptoms affect about 30–50% of people with AD (Lee and Lyketsos 2003). The typical presentation of depression in AD is different than in non-demented elderly with depression in that it is marked by more motivational and psychotic symptoms but less guilt, suicidal thoughts or reports of low self-esteem (Olin et al. 2002; Rosenberg et al. 2005). This has led to the proposal that depression in AD may represent a distinct syndrome, and to the question as to whether patients with AD will respond to antidepressant treatment. Pharmacotherapy studies of treatment of depression in AD, which have shown conflicting results (Lyketsos et al. 2000; Lyketsos et al. 2003; Magai et al. 2000; Petracca et al. 1996; Petracca et al. 2001; Reifler et al. 1989; Roth et al. 1996), have primarily focused on people that meet the criteria for major or minor depression (MaD and MiD, respectively) instead of the set depressive syndromes commonly seen in those with AD.

The Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease Study – 2 (DIADS-2) was designed to address the need for controlled studies of the efficacy and safety of anti-depressant treatment for depression in AD. DIADS-2 was a clinical trial of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) sertraline for the treatment of depression in persons with AD. In the primary results from the trial’s 12- and 24-week follow-up periods, sertraline was not found to be efficacious for the treatment of “depression in AD” (dAD). The rates of common SSRI adverse events and serious adverse events were higher in the group assigned to sertraline than in the group assigned to placebo (Rosenberg et al. 2010) (Weintraub D et al. 2010). In this paper, we explore the question of whether the effects of treatment differed in subgroups of patients who met various depressive criteria at baseline such as MaD, MiD, or Alzheimer Associated Affective Disorder (AAAD) (Lyketsos et al. 2001).

Methods

Study population

DIADS-2 was a 24-week, randomized, multicenter clinical trial with two parallel treatment groups assigned in a 1:1 ratio. The two treatment groups were: 1) sertraline (target dose 100 mg/day) + standardized psychosocial intervention and 2) placebo + standardized psychosocial intervention for the initial 12 weeks, with an option for responders to continue randomized study treatment for the final 12 weeks of the study. A primary caregiver accompanied patients to study visits to receive the psychosocial intervention and participate in study assessments. Patients, caregivers and all personnel at the clinical sites were masked to treatment assignment. DIADS-2 participants were recruited from memory clinics, geriatric psychiatry clinics, Veterans Administration geriatric clinics, community outreach, and Alzheimer Research Center pools and registries at 5 clinical sites: Johns Hopkins School of Medicine (Baltimore, MD), University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (Philadelphia, PA), Medical University of South Carolina (Charleston, SC), University of Rochester School of Medicine (Rochester, NY), and University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine (Los Angeles, CA). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of each clinical site and of the Coordinating Center at Johns Hopkins.

Patients were diagnosed with AD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association 2000) and had a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al. 1975) score of 10–26 inclusive. Patients also met the criteria for depression of AD (dAD) as defined by an NIMH working group, the “Olin Criteria” (Olin et al. 2002), and operationalized by the DIADS-2 investigators (Rosenberg et al. 2005).

Scheduled clinic visits occurred at baseline, and at 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks after baseline. At week 12, patients whose mood symptoms were rated as having not improved on the modified Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Clinical Global Impression of Change (mADCS-CGIC) (described below) had the option of tapering off of study medication and advancing to the treatment of their doctor’s choice. For the remainder of the participants, randomized study treatment ended at week 24. All patients followed the same schedule of study assessments regardless of when they terminated treatment. Patients were unmasked to treatment assignment at week 24. A detailed description of the DIADS-2 design including all eligibility criteria has been published (Martin et al. 2006).

Baseline assessment of depression criteria

The patients enrolled in DIADS-2 all met the criteria for dAD, but were also assessed for MaD, MiD and AAAD since it was thought a priori that the treatment effect may depend on specific depression criteria. Planned subgroups analyses based on baseline depression criteria were specified in the DIADS-2 protocol and design paper (Martin et al. 2006). Depression was rated at baseline by a research clinician; the clinician recorded whether or not the patient met the diagnostic criteria for MaD episode by DSM-IV criteria, MiD episode if meeting 3 or 4 of the MaD depressive symptoms (including either anhedonia or dysphoria), or for AAAD using the Cache County criteria (Lyketsos et al. 2001). MaD and MiD are mutually exclusive diagnoses but an AAAD diagnosis can, but does not necessarily, overlap MaD or MiD. Appendix 1 shows the detailed definition of each depression criteria. Each patient’s history of depression diagnoses, the duration of the current depressive episode, the presence of agitation, delusions and hallucinations as rated by a score greater than zero on the respective domains of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (Cummings, 1994), and the severity of depression as rated by the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (Alexopoulos et al. 1988) were also assessed at baseline. The severity of depression at baseline was categorized as more severe (CSDD > 12) versus less severe (CSDD ≤ 12).

Appendix 1.

Depression criteria

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| dAD |

|

| MaD |

|

| MiD |

|

| AAAD |

|

dAD, depression in Alzheimer’s disease; MaD, Major Depressive episode; MiD, minor Depressive episode; AAAD, Alzheimer’s-Associated Affective Disorder

Outcome assessment

Mood was assessed at each in-person follow-up visit (weeks 2, 4 and every 4 weeks thereafter until week 24). Clinicians, using input from the caregivers, rated a patient’s change in depressive symptoms from baseline using the modified Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Clinical Global Impression of Change (mADCS-CGIC), which is an adaptation of the ADCS-CGIC (Schneider et al. 1997) that incorporates a global rating of mood symptoms. The mADCS-CGIC is a seven-point scale ranging from 7 = “much worse” to 4 = “no change,” to 1 = “much better”. The clinician also rated the severity of depression using the CSDD, a 19-item scale with a range from 0 to 38 measuring depression severity using input from both the caregiver and the patient. Remission of depression was defined by a combination of mADCS-CGIC score ≤2 and CSDD score ≤6.

Analysis

The statistical analysis for the overall treatment effect for the mADCS-CGIC, CSDD, and remission outcomes have been described in detail previously (Rosenberg et al. 2010; Weintraub D et al. 2010). Briefly, all analyses were performed according to the patients’ original treatment assignment (intention-to-treat; regardless of changes in treatment status at week 12). Missing mood outcome data were imputed using the method of multiple imputation (Rubin 1996a; Rubin 1996b).

The comparison of the two treatment groups at weeks 12 and 24 of ratings on the mood domain of the mADCS-CGIC was performed with proportional odds logistic regression. CSDD scores over the 24 weeks were compared using mixed effects models, allowing a random intercept and slope for each patient. The CSDD scores were skewed to the right so a square-root transformation of the scores was used as the outcome in the regression models. Polynomial terms were used to model the trajectory of CSDD scores over time. To test for different rates of change in CSDD over time in the treatment groups, a likelihood ratio test was used to compare a model allowing the changes over time to differ by treatment group to a model that did not allow the changes over time to differ by treatment group. The medians of the CSDD scores at weeks 12 and 24 were also compared. The standard errors of medians were calculated by bootstrapping. The proportion of patients in each treatment group whose depression remitted at weeks 12 and 24 was compared using logistic regression.

We formally tested for subgroup effects in the logistic regression models by adding interaction terms for subgroup-by-treatment. We tested for subgroup effects in the mixed models by adding interactions terms for subgroup-by-treatment-by-time.

Tests for interaction were performed for the following pre-specified baseline subgroups: MaD vs no MaD, MaD vs MiD vs neither, AAAD vs no AAAD. Tests for interaction were also performed for the following exploratory baseline subgroups: depression severity (CSDD > 12 vs CSDD ≤ 12), history of MaD diagnosis vs no history, presence versus absence of agitation, delusions, or hallucinations as assessed by the NPI, and duration of the current depressive episode.

Statistical analyses and graphics were performed using R version 2.9.1 (R Development Core Team 2009). No adjustments for multiple testing were made to the p-values, but the number of tests for interactions that were performed is listed in the results section.

Results

131 patients were randomized in DIADS-2, 67 to sertraline and 64 to placebo. The median age of the patients at baseline was 79 years, and approximately half (54%) were female; 67% were non-Hispanic white, 21% were African-American, and 11% were Hispanic/Latino. The median MMSE score was 20 (1st, 3rd quartiles: 16, 24), reflecting mild-to-moderate severity of dementia.

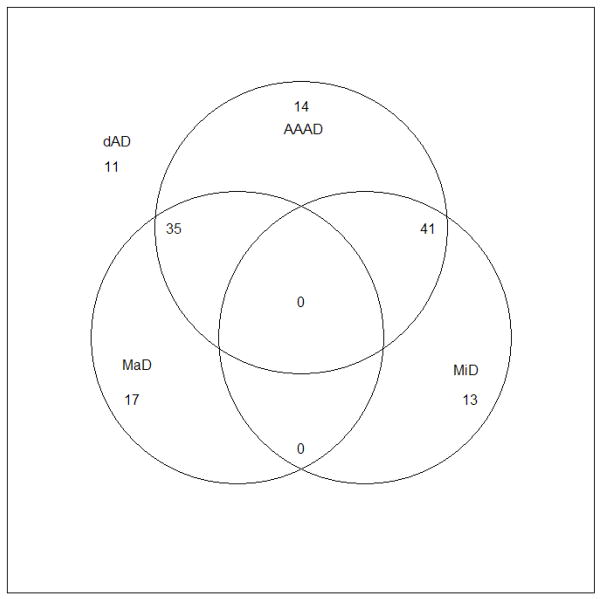

The number of patients meeting various depression and related criteria of interest were well balanced between treatment groups at baseline and the corresponding CSDD score in each group is shown in Table 1. All patients met criteria for dAD at baseline. 52 (39.7%) patients met criteria for MaD at baseline, 26 from each treatment group. An additional 54 (41.2%) patients met criteria for MiD at baseline, 28 (41.8%) in the sertraline group and 26 (40.6%) in the placebo group. More than two-thirds of patients met criteria for AAAD at baseline, 47 (70.2%) in sertraline group and 43 (67.2%) in placebo group. 25 (19.1%) patients met enrollment criteria for dAD at baseline but did not meet criteria for either MaD or MiD; 11 of these did not meet criteria for MaD, MiD or AAAD. The overlap between the various depression criteria is shown in Figure 1. The median length of the current episode of depression at baseline was 49 weeks (interquartile range: 20 – 80). On the NPI, just over half (57.3%) of patients exhibited some symptoms of agitation at baseline (i.e., had a scale score ≥ 0); approximately one-third (34.4%) demonstrated delusional thinking, and 9.2% were experiencing hallucinations.

Table 1.

Number (%) of patients meeting various mood syndrome criteria at baseline and corresponding baseline median CSDD scores

| Criteria | Total | Sertraline | Placebo | Median CSDD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MaD | 52 (39.7) | 26 (38.8) | 26 (40.6) | 18.5 |

| MiD | 54 (41.2) | 28 (41.8) | 26 (40.6) | 12 |

| Neither MaD nor MiD | 25 (19.1) | 13 (19.4) | 12 (18.8) | 9 |

| AAAD | 90 (68.7) | 47 (70.2) | 43 (67.2) | 14 |

| CSDD > 12 | 71 (54.2) | 37 (55.2) | 34 (53.1) | 17 |

| NPI agitation scale > 0 | 75 (57.3) | 42 (62.7) | 33 (51.6) | 14 |

| NPI delusion scale > 0 | 45 (34.4) | 24 (35.8) | 21 (32.8) | 17 |

| NPI hallucination scale > 0 | 12 (9.2) | 7 (10.5) | 5 (7.8) | 17 |

MaD, Major Depressive episode; MiD, minor Depressive episode; AAAD, Alzheimer’s-Associated Affective Disorder; CSDD, Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory

Figure 1.

Venn diagram showing overlap of depression criteria at baseline

The test statistics and p-values for a subset of the tests for interaction are shown in Table 2. In total, 45 tests of interaction were performed (5 outcomes by 9 subgroups). We observed one significant interaction, likely a chance occurrence, in the subgroup defined by the presence of agitation symptoms at baseline for the longitudinal CSDD outcome, and a borderline significant interaction in the subgroup meeting criteria for AAAD at baseline for the remission outcome.

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses* – tests for interaction

| Outcome | Baseline Subgroups | Test statistic** for interaction | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGIC at week 12 | MaD vs. no MaD | χ2 = 0.63 (1df) | 0.43 |

| MaD vs. MiD vs. neither | χ2 = 1.05 (2df) | 0.59 | |

| AAAD vs. no AAAD | χ2 = 0.06 (1df) | 0.81 | |

| CSDD ≤ 12 vs. CSDD > 12 | χ2 = 1.23 (1df) | 0.27 | |

| NPI agitation vs. no NPI agitation | χ2 = 0.25 (1df) | 0.62 | |

| CGIC at week 24 | MaD vs. no MaD | χ2 = 0.22 (1df) | 0.64 |

| MaD vs. MiD vs. neither | χ2 = 0.51 (2df) | 0.77 | |

| AAAD vs. no AAAD | χ2 = 0.33 (1df) | 0.56 | |

| CSDD ≤ 12 vs. CSDD > 12 | χ2 = 0.67 (1df) | 0.41 | |

| NPI agitation vs. no NPI agitation | χ2 = 0.10 (1df) | 0.75 | |

| Remission at week 12 | MaD vs. no MaD | χ2 = 0.06 (1df) | 0.81 |

| MaD vs. MiD vs. neither | χ2 = 0.90 (2df) | 0.64 | |

| AAAD vs. no AAAD | χ2 = 3.55 (1df) | 0.06 | |

| CSDD ≤ 12 vs. CSDD > 12 | χ2 = 1.41 (1df) | 0.23 | |

| NPI agitation vs. no NPI agitation | χ2 = 0.82 (1df) | 0.37 | |

| Remission at week 24 | MaD vs. no MaD | χ2 = 1.31 (1df) | 0.25 |

| MaD vs. MiD vs. neither | χ2 = 2.24 (2df) | 0.33 | |

| AAAD vs. no AAAD | χ2 = 0.85 (1df) | 0.57 | |

| CSDD ≤ 12 vs. CSDD > 12 | χ2 = 1.64 (1df) | 0.20 | |

| NPI agitation vs. no NPI agitation | χ2 = 1.48 (1df) | 0.22 | |

| CSDD, all 24 weeks | MaD vs. no MaD | χ2 = 3.29 (3df) | 0.35 |

| MaD vs. MiD vs. neither | χ2 = 4.73 (6df) | 0.58 | |

| AAAD vs. no AAAD | χ2 = 3.69 (3df) | 0.30 | |

| CSDD ≤ 12 vs. CSDD > 12 | χ2 = 2.60 (3df) | 0.46 | |

| NPI agitation vs. no NPI agitation | χ2 = 9.06 (3df) | 0.03 |

MaD, Major Depressive episode; MiD, minor Depressive episode; AAAD, Alzheimer’s-Associated Affective Disorder; CSDD, Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory.

Subgroup analyses were also performed for the following baseline subgroups that are not included in the table: NPI delusions, NPI hallucinations, history of MaD, and duration of depressive episode. All p-values were greater than 0.10.

The Wald χ2 test statistic was used in the logistic models when one term was being tested. The likelihood ratio χ2 test statistic was used in models when two or more terms were simultaneously being tested (e.g., MaD vs. MiD vs. neither and the treatment-by-subgroup-by-time effects in the longitudinal CSDD models).

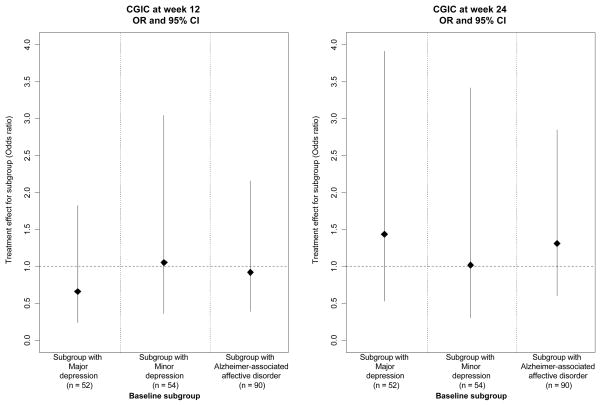

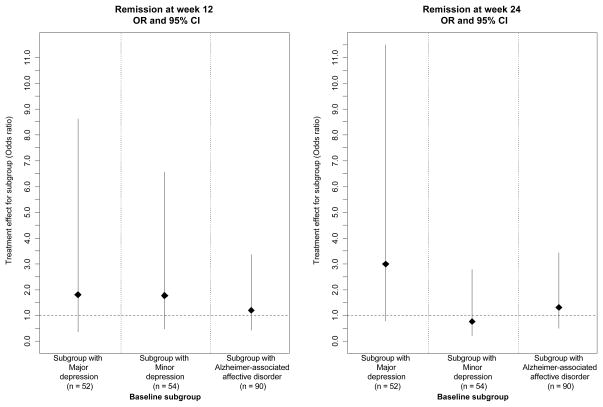

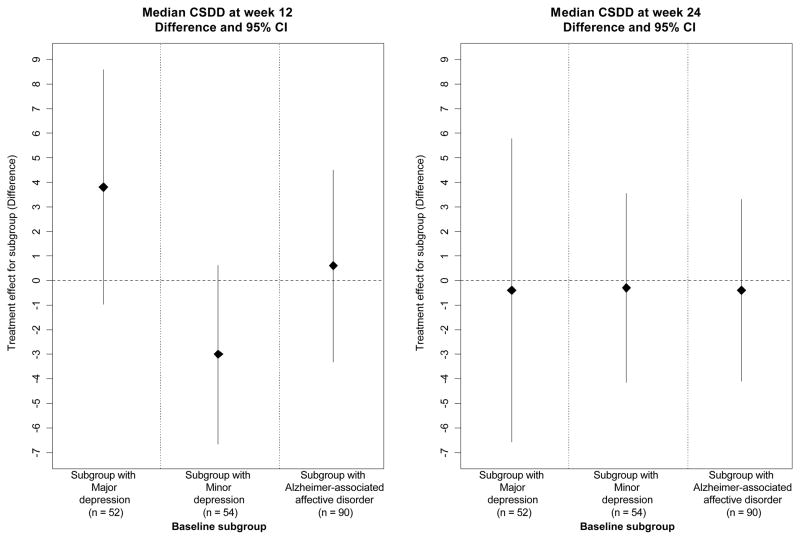

To visually show the magnitude and variability of the treatment effect estimates (sertraline vs placebo) in the various subgroups, we plotted the effect estimates for the subgroups in Figures 2–4. Figure 2 shows the treatment effect for the primary outcome of mADCS-CGIC in the pre-specified subgroups defined by baseline depression criteria. Figures 3 and 4 show the treatment effect for the secondary mood outcomes of CSDD scores and remission. Sertraline was not superior to placebo in patients who met the criteria for MaD at baseline for mADCS-CGIC ratings at 12 weeks (ORsertraline = 0.66 [95% CI: 0.24, 1.82], p = 0.42), mADCS-CGIC ratings at 24 weeks (ORsertraline = 1.44 [95% CI: 0.53, 3.91], p = 0.48), or median CSDD scores at both 12 (difference = 3.8 [95% CI: −0.96, 8.56], p = 0.12) and 24 weeks (difference = −0.4 [95% CI: −6.57, 5.77], p = 0.90). Additionally, no difference was found between the treatment groups in the proportion of patients in remission at weeks 12 (ORsertraline = 1.80 [95% CI: 0.38, 8.63], p = 0.46) or 24 (ORsertraline = 2.99 [95% CI: 0.78, 11.49], p = 0.11) for the subgroup with MaD at baseline. There were also no differences between the treatment groups for any of these outcomes in the subgroups defined by MiD at baseline or AAAD at baseline; the treatment effect estimates and confidence intervals in these baseline subgroups are also shown in Figures 2–4.

Figure 2.

Treatment effect estimates (sertraline vs. placebo) for mADCS-CGIC in subgroups of patients meeting depression criteria at baseline (Odds ratio* [OR] and 95% CI)

*OR is the odds ratios (calculated using proportional odds logistic regression) of being at or better than a given mADCS-CGIC category for sertraline vs. placebo.

Figure 4.

Treatment effect estimates (sertraline vs. placebo) for remission* in subgroups of patients meeting depression criteria at baseline (Odds ratio** [OR] and 95% CI)

* Remission of depression was defined as mADCS-CGIC score ≤2 and CSDD score ≤6.

**OR was calculated using logistic regression.

Figure 3.

Treatment effect estimates (sertraline vs. placebo) for CSDD in subgroups of patients meeting depression criteria at baseline (difference and 95% CI in median CSDD*)

*Confidence intervals for medians calculated using bootstrapping.

Discussion

The aim of this analysis was to determine whether the treatment effect of sertraline differed by baseline depression criteria and if the overall null results from DIADS-2 could have been due to the fact that we allowed less symptomatic patients in the trial. Specifically, we tested for treatment-by-subgroup interactions for the pre-specified subgroups of interest, MaD vs no MaD, MaD vs MiD vs neither, and AAAD vs no AAAD, as well as other potentially important subgroups defined by baseline depression severity (CSDD > 12, length of depressive episode, history of MDE diagnosis) and the presence of specific neuropsychiatric symptoms (agitation, delusions, and hallucinations).

We found no evidence that the treatment effect of sertraline was larger in the MaD or AAAD group or those groups with higher baseline CSDD scores. One would expect to see slightly more than two significant results at the 0.05 level by chance with 45 tests. Of the 45 tests for interaction performed, only one was significant at the 0.05 level and another was borderline significant at the 0.05 level. In both cases, the treatment effect was larger in those patients with less severe symptoms than in those with more severe symptoms. Specifically, the differences in the changes over time in the CSDD scores were more favorable for the sertraline group in patients without baseline agitation. Similarly, the odds ratio of remission at week 12 for sertraline vs. placebo was higher in those patients without AAAD at baseline.

These null findings are not likely solely due to a lack of power. While it is true that tests for interactions have reduced power to detect differences, in this case the subgroup effects did not seem to be either clinically significant or consistent with the a priori hypothesis that the sertraline treatment effect would be greater in those with MaD or more severe baseline depressive symptoms. Assuming this is a valid estimate of the subgroup effect, a larger sample and more power would not alter the fact that there does not seem to be a greater effect in those with more symptoms at baseline.

A recent meta-analysis (Fournier et al. 2010) of data from six randomized, placebo-controlled trials (718 patients) of antidepressants approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of major or minor depressive disorder in people of mixed ages indicated that the efficacy of antidepressant medication for treatment of depression varies by symptom severity. The magnitude of the benefit of antidepressant medications over placebo was nonexistent or negligible among depressed patients with mild, moderate, and even severe baseline symptoms. However the benefit of medications over placebo was substantial for patients with very severe depression.

Another meta-analysis of ten randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials (2,377 patients) in outpatients 60 years and older with nonpsychotic, unipolar major depression of second-generation antidepressants in late-life major depression has also been performed (Nelson et al. 2008). The authors reported that antidepressants were more effective than placebo in elderly depressed individuals although effects were modest since the estimated antidepressant-placebo differences were only 1.4 points on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D). Drug – placebo differences of this magnitude are not clinically meaningful according to the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) criterion of clinical significance (i.e., 3 point difference in HAM-D scores) (National Institute for Clinical Excellence 2004).

Conclusions

We find no evidence that the treatment effect of sertraline was larger in depressed AD patients with MaD compared to MiD, or neither at baseline or in patients with more severe depressive symptoms compared to less severe symptoms at baseline. The null results of DIADS-2 were not due to a dilution of the treatment effect due to the addition of patients with less severe depression.

Key points.

Sertraline was found to be no better than placebo for the treatment of depression in patients with ‘depression of Alzheimer’s disease’.

Sertraline was also found to be no better than placebo for the treatment of depression for subgroups of patients meeting criteria for major depression compared to minor depression, and compared to neither major or minor depression, or for depression with more severe symptoms compared to less severe.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support

Grant funding:

National Institute of Mental Health, 1U01MH066136, 1U01MH068014, 1U01MH066174, 1U01MH066175, 1U01MH066176, 1U01MH066177; NIMH scientific collaborators participated on the trial’s Steering Committee

Drug:

Sertraline and matching placebo provided by Pfizer, Inc.; Pfizer did not participate in the design or conduct of the trial; Manisha Hong, PharmD at Johns Hopkins Hospital Investigational Drug Service packaged and shipped drug

Steering Committee (responsibilities: study design and conduct)

Resource center representatives (voting):

Constantine Lyketsos, MD, MHS (study chair), Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore

Barbara Martin, PhD (coordinating center former director), Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore

George Niederehe, PhD (scientific collaborator), National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda

Clinic directors (voting):

Paul Rosenberg, MD, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore

Jacobo Mintzer, MD, PhD, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston

Daniel Weintraub, MD, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia

Anton Porsteinsson, MD, University of Rochester School of Medicine, Rochester

Lon Schneider, MD, University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles

Other non-voting members:

Anne Shanklin Casper, MA, CCRP, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore

Lea Drye, PhD, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore

Crystal Evans, MS, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore

Curtis Meinert, PhD, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore

Cynthia Munro, PhD, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore

Peter Rabins, MD, MPH, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore

Research group

Resource centers (responsibilities: study administration):

Chairman’s Office, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore:

Constantine Lyketsos, MD, MHS, chairman

Crystal Evans, MS, coordinator

Cynthia Munro, PhD, study neuropsychologist

Peter Rabins, MD, MPH

Krissi Boehmer, BA

Adrian Mosely, MSW

Dimitrios Avramopoulos, MD, PhD

Coordinating Center, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore:

Curtis Meinert, PhD, director

Barbara Martin, PhD, former director

Lea Drye, PhD, epidemiologist

Constantine Frangakis, PhD, biostatistician

Anne Shanklin Casper, MA, CCRP, coordinator

Vijay Vaidya, MPH

Jill Meinert

Project Office, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda:

George Niederehe, PhD, scientific collaborator

Jovier Evans, PhD, project officer

Joanna Chisar, RN

Louise Ritz, MBA

Elizabeth Zachariah, MS

Clinics (responsibilities: data collection):

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore:

Paul Rosenberg, MD, director

Ann Morrison, RN, PhD, coordinator

Crystal Evans, MS

Pramit Rastogi, MD, MPH

Krissi Boehner, BS

Chiadi Onyike, MD

Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston

Jacobo Mintzer, MD, PhD, director

Crystal Longmire, PhD, coordinator

Warachal E. Faison, MD

Martie Hatchell, RN

Marilyn Stuckey, RN

University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia

Daniel Weintraub, MD, director

Ira Katz, MD, PhD, former director

Trisha Stump, RN, coordinator

Joel Streim, MD

Suzanne DiFilippo, RN

Kate O’Neill

University of Rochester School of Medicine, Rochester

Anton Porsteinsson, MD, director

Bonnie Goldstein, RN, coordinator

Jeanne LaFountain, RN

Colleen McCallum, MSW

Laura Jakimovich, MNS

Kim Martin, RN

Margaret McGrath, RN

Kelly Cosman, MS

University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, Los Angeles:

Lon Schneider, MD, director

Sonia Pawluczyk, MD

Karen Dagerman, MS

Randall Sanabria

Liberty Teodoro, RN

Yanli Wang, MS

Ju Zhang

Liberty Teodoro

Footnotes

- These disclosures refer to the period between 7/1/02 and 10/31/08, and include any anticipated conflicts through 12/31/09, according to the DIADS-2 Conflict of Interest Policy (available upon request from the study PI).

- Barbara Martin is involved in another trial for which Pfizer donated a different drug.

- Paul Rosenberg has served as a consultant for Forest regarding the drug memantine, and has received research funds from Pfizer and Merck in amounts greater than $10,000.

- Jacobo Mintzer has received research support from Abbot to study donepezil and divalproex sodium, from AstraZeneca to study quetiapine, from BMS to study aripiprazole, from Eli Lilly to study olanzapine, from Forest to study both citalopram and memantine, from Janssen to study galantamine and risperidone, and from Pfizer to study donepezil and memantine; Dr. Mintzer also has been a consultant, paid directly or indirectly, for AstraZeneca, BMS, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, Forest, and Aventis. He also has been an unpaid consultant for Targacept and has participated in Speaker’s Bureaus for Janssen, Forest, and Pfizer.

- Daniel Weintraub has received research support from Boehringer Ingelheim; Dr. Weintraub also has been a paid consultant for Acadia Pharmaceuticals, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Osmotica Pharmaceutical, BrainCells Inc., EMD Serono, and Sanofi Aventis, and has participated on a Speaker’s Bureau for Pfizer.

- Anton Porsteinsson is involved in research sponsored by Pfizer to study donepezil and PF04494700, Eli Lilly to study atomoxetine, a gamma-secretase inhibitor and a beta amyloid antibody, Wyeth to study a beta amyloid antibody, GSK to study a PPAR inhibitor and Forest to study memantine and neramexane; Dr. Porsteinsson has been a paid consultant and participated on a Speaker’s Bureau for Pfizer and Forest.

- Lon S. Schneider is involved in research sponsored by Pfizer, the manufacturer of sertraline and other drugs used to treat mood disorders; Dr. Schneider has been a paid consultant for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson and Johnson, Lundbeck, Merck, and Wyeth, manufacturers of antidepressants or drugs used to treat mood disorders.

- Constantine Frangakis has no conflict of interests.

- Lea Drye has no conflict of interests.

- Peter Rabins has participated on Speaker’s Bureaus for Wyeth, Eli Lilly, and Pfizer.

- Cynthia Munro has no conflict of interests.

- Curtis Meinert is involved in another trial for which Pfizer donated a different drug; Dr. Meinert owns shares of GSK stock.

- Constantine Lyketsos was involved in another trial for which Pfizer donated a different drug; he also was involved in research sponsored by Forest to study escitalopram and citalopram and Pfizer to study sertraline and donepezil; Dr. Lyketsos served as a consultant for Organon, Eisai, GSK, Lilly, Wyeth, and Pfizer.

Reference List

- 1.Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475–1483. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinberg M, Shao H, Zandi P, Lyketsos CG, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Norton MC, Breitner JC, Steffens DC, Tschanz JT. Point and 5-year period prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia: the Cache County Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(2):170–177. doi: 10.1002/gps.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee HB, Lyketsos CG. Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: heterogeneity and related issues. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(3):353–362. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00543-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg PB, Onyike CU, Katz IR, Porsteinsson AP, Mintzer JE, Schneider LS, Rabins PV, Meinert CL, Martin BK, Lyketsos CG. Clinical application of operationalized criteria for ‘Depression of Alzheimer’s Disease’. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(2):119–127. doi: 10.1002/gps.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olin JT, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Schneider LS, Lebowitz BD. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease: rationale and background. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10 (2):129–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roth M, Mountjoy CQ, Amrein R. Moclobemide in elderly patients with cognitive decline and depression: an international double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168(2):149–157. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reifler BV, Teri L, Raskind M, Veith R, Barnes R, White E, McLean P. Double-blind trial of imipramine in Alzheimer’s disease patients with and without depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146(1):45–49. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyketsos CG, Sheppard JM, Steele CD, Kopunek S, Steinberg M, Baker AS, Brandt J, Rabins PV. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of sertraline in the treatment of depression complicating Alzheimer’s disease: initial results from the Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(10):1686–1689. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Magai C, Kennedy G, Cohen CI, Gomberg D. A controlled clinical trial of sertraline in the treatment of depression in nursing home patients with late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;8(1):66–74. doi: 10.1097/00019442-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petracca G, Teson A, Chemerinski E, Leiguarda R, Starkstein SE. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of clomipramine in depressed patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;8(3):270–275. doi: 10.1176/jnp.8.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petracca GM, Chemerinski E, Starkstein SE. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluoxetine in depressed patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2001;13(2):233–240. doi: 10.1017/s104161020100761x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyketsos CG, DelCampo L, Steinberg M, Miles Q, Steele CD, Munro C, Baker AS, Sheppard JM, Frangakis C, Brandt J, Rabins PV. Treating depression in Alzheimer disease: efficacy and safety of sertraline therapy, and the benefits of depression reduction: the DIADS. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):737–746. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberg PB, Drye LT, Martin BK, Frangakis C, Mintzer JE, Weintraub D, Porsteinsson AP, Schneider LS, Rabins PV, Munro CA, Meinert CL, Lyketsos CG. Sertraline for the treatment of depression in Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):136–145. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181c796eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weintraub D, Rosenberg PB, Drye LT, et al. Sertraline for the treatment of depression in Alzheimer’s disease: Week-24 outcomes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(4):332–340. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cc0333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyketsos CG, Breitner JC, Rabins PV. An evidence-based proposal for the classification of neuropsychiatric disturbance in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(11):1037–1042. doi: 10.1002/gps.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:196–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin BK, Frangakis CE, Rosenberg PB, Mintzer JE, Katz IR, Porsteinsson AP, Schneider LS, Rabins PV, Munro CA, Meinert CL, Niederehe G, Lyketsos CG. Design of Depression in Alzheimer’s Disease Study-2. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):920–930. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000240977.71305.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, Shamoian CA. Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23(3):271–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schneider LS, Olin JT, Doody RS, Clark CM, Morris JC, Reisberg B, Schmitt FA, Grundman M, Thomas RG, Ferris SH. Validity and reliability of the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Clinical Global Impression of Change. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(Suppl 2):S22–S32. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199700112-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1996a. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. J Am Stat Assoc. 1996b;91:473–489. [Google Scholar]

- 23.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Dimidjian S, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Fawcett J. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;303(1):47–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson JC, Delucchi K, Schneider LS. Efficacy of second generation antidepressants in late-life depression: a meta-analysis of the evidence. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(7):558–567. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181693288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Clinical practice guideline. 23. National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2004. Depression: management of depression in primary and secondary care. [Google Scholar]