Abstract

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a strong risk factor for lung cancer. Published studies regarding variations of genes encoding glutathione metabolism, DNA repair, and inflammatory response pathways in susceptibility to COPD were inconclusive.

We evaluated 470 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from 56 genes of these 3 pathways in 620 cases and 893 controls to identify susceptibility markers for COPD risk, using existing resources. We assessed SNP- and gene-level effects adjusting for sex, age, and smoking status. Differential genetic effects on disease risk with and without lung cancer were also assessed; cumulative risk models were established.

Twenty-one SNPs were found to be significantly associated with risk of COPD (P<0.01); gene-based analyses confirmed 2 genes (GCLC and GSS) and identified 3 additional (GSTO2, ERCC1, and RRM1). Carrying 12 high-risk alleles may increase risk by 2.7-fold; 8 SNPs altered COPD risk with lung cancer 3.1-fold, and 4 SNPs altered the risk without lung cancer 2.3-fold.

Our findings indicate that multiple genetic variations in the 3 selected pathways contribute to COPD risk through GCLC, GSS, GSTO2, ERCC1, and RRM1 genes. Functional studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms of these genes in the development of COPD, lung cancer, or both.

Keywords: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Glutathione Metabolism Pathway, DNA Repair Pathway, Inflammatory Response Pathway

Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD including emphysema and/or chronic bronchitis), characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible, has been a major and independent risk factor for lung cancer (1-3). Although cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for COPD, very similar to lung cancer, only a minority of smokers develops the disease (4), indicating additional risk factors being involved. It is important to identify the role of genetic susceptibility (5), particularly the common and disparate effects on the risk of COPD with and without lung cancer. Evidence for genetic susceptibility in COPD risk has been derived from family studies (6-8). A well-established genetic predictor for COPD is α1-antitrypsin deficiency status (9), with 1–2% of COPD patients having inherited α1-antitrypsin deficiency (10). Genomic variations of genes participating in the toxin metabolism, DNA repair, and inflammatory response pathways have been implicated in the pathogenesis of COPD (2, 11-18). Genes in the glutathione pathway are highly polymorphic and many are correlated with enzyme activities of the pathway and may alter susceptibility in individuals exposed to hazardous environments, such as cigarette smoking (19). The DNA repair system plays a critical role in protecting the genome from insults caused by hazardous environments (2). Polymorphisms in DNA repair genes, which affect the normal protein activity, may alter the efficiency of DNA repair processes and lead to genetic instability and increased COPD risk (12, 20). Persistent inflammatory responses to environmental exposures, including microbial agents, may have a role in COPD pathogenesis through a complex network of signaling molecules (21). Genetic variants in the inflammatory response pathway may perturb the balance of the network and lead to COPD.

Common etiologic and pathogenetic pathways leading to COPD and lung cancer have been well accepted (1, 2, 22, 23) and is a pressing challenge in understanding the biological mechanisms linking the two diseases. The importance of identifying genetic markers is at least three-fold: linking DNA sequence change to functional alterations, leading to more in-depth mechanistic investigations, and easy-access DNA to test in practice. Although numerous candidate gene and pathway based studies exist on lung cancer and COPD risks, only a few have considered both phenotypes (24-28). Four genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified candidate genes and genomic loci for lung cancer at chromosomes 5p15.33, 15q25.1, 6p21.33, and 13q31.3; three GWAS on COPD risk or lung function pointed to 2q35, 4q22, 4q24, 4q31, 5q33, 6p21, and 15q23 (29-35). Three of the four GWAS on lung cancer were primarily performed in smokers but none considered COPD. Moreover, results from the candidate gene approach provided further evidence that COPD should be considered when linking genetic markers to lung cancer risk (5, 22, 23). In our study, we comprehensively explored the potential genetic effects of the glutathione (GSH) metabolism, DNA repair, and inflammatory response pathways on COPD risk by using haplotype tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (htSNPs or SNPs) using multi-level analytic strategies in a relatively large set of United States’ white cases and controls with European ancestry. Importantly, we evaluated the common and unique genetic variations in risk of COPD with and without lung cancer.

Methods and Materials

Study Subjects

As a part of the Mayo Clinic Epidemiology and Genetics of Lung Cancer Program, initiated in 1997, all patients with pathologically diagnosed primary lung cancer, with or without COPD, have been prospectively recruited (9). Community residents, with or without COPD were identified and enrolled within the same time period of cases’ recruitment, having had a general medical examination and a leftover blood sample from routine clinical tests (36). There are two sets of COPD cases. The first set is lung cancer cases with COPD, and the second set is community residents with COPD. Never smokers were defined as having smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes during their lifetimes (cigar or pipe smokers were excluded from the never smokers). Former smokers were defined as having quit smoking six months or longer before the date of diagnosis (cases) or enrollment (controls).

The diagnosis of COPD was based on symptoms (cough, sputum production, and/or dyspnea) and spirometry, confirming non-reversible airflow limitation (3, 37). We extracted medical record information on all subjects who had a confirmed diagnosis of COPD prior to lung cancer diagnosis (COPD with lung cancer) and gathered information by study questionnaires from enrolled community residents who reported a physician-diagnosed history of COPD (COPD without lung cancer). The control group was comprised of community residents who had neither COPD history nor lung cancer (9, 33). To minimize ethnic background heterogeneity, we restricted our analysis to the U.S. European descendents. In total, 620 COPD cases and 893 controls were included in this study. Of the COPD cases, 432 developed lung cancer after suffering from COPD, and 188 were free of lung cancer.

SNP Selection and Genotyping

We selected 56 genes, 29 from the GSH metabolic pathway (19), 20 from the DNA repair pathway, and 7 from the inflammatory response pathway following a review of the literature that reported an association with lung cancer. HapMap htSNPs were selected based on HapMap data of 60 unrelated Caucasian (CEU) subjects (Release 22/Phase II on NCBI B36) using Haploview (http://www.broad.mit.edu /mpg/haploview). Four hundred seventy htSNPs, 267 from GSH, 152 from DNA repair, and 51 from inflammation pathways, were genotyped in Mayo Clinic's Technology Center Genotyping Shared Resource of the using a custom-designed Illumina GoldenGate 480-SNP panel. Quality assessment was conducted in multiple steps as described previously(16). Excluded were SNPs with a call rate less than 95%, Hardy-Weinberg P-values less than 0.0001, or a minor allele frequency less than 0.01.

Statistical Analysis

We first performed unconditional logistic regression analysis adjusting for age, sex, and smoking status under additive, dominant, and recessive genetic models. We then performed a Fisher's combination test of P-values that were assumed independent (38, 39). This test follows a Chi-squared (χ2) distribution with a degree of freedom equal to 2-fold the number of haplotype tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (htSNPs) within the gene, assuming linkage disequilibrium between the SNPs is less than 0.2 (40). We also performed stratified analyses by subjects’ lung cancer status. To determine the cumulative effects of the statistically significant htSNPs on COPD risk, we modeled total number of risk alleles as a categorical variable and a continuous variable (41). All tests were two-tailed, and the significance threshold was set at less than 0.01. We chose not to take conventional multiple comparison approaches that treats all SNPs are independent of each other. All analyses were carried out using SAS, Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and R software.

Results

SNP-based analysis results

Among the 470 htSNPs selected for genotyping, 405 passed quality assessment and were used in the analyses (see Supplementary Appendix, Table E1). Table 1 provides demographic and clinical characteristics of the COPD cases and controls; age, sex, smoking status, and pack-years were found significantly different (P < 0.01). Since smoking status and pack-years are surrogate to each other, we included only smoking status, age, and sex in further multivariable logistic regression models.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinic Characteristics

| Characteristics | Number of COPD Cases (%) |

Number of Controls (%) (Without COPD and Lung Cancer) N=893 | P-valuea | P-valueb | P-valuec | P-valued | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Lung Cancer N=432 | Without Lung Cancer N=188 | Total N=620 | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 240(55.56%) | 82(43.62%) | 322(51.94%) | 348(38.97%) | 0.008 | <0.001 | 0.271 | <0.001 |

| Female | 192(44.44%) | 106(56.38%) | 298(48.06%) | 545(61.03%) | ||||

| Age± SD (year) | 66.99± 8.54 | 67.27± 9.67 | 67.08± 8.89 | 64.97± 9.97 | 0.731 | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| Smoking Status | ||||||||

| Never | 31(7.18%) | 29(15.43%) | 60(9.67%) | 564(63.16%) | ||||

| Former | 217(50.23%) | 94(50.00%) | 311(50.16%) | 195(21.84%) | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Current | 184(42.59%) | 65(34.57%) | 249(40.16%) | 134(15.01%) | ||||

| Pack-years | ||||||||

| 0 & never smoker | 31 (7.18%) | 33 (17.55%) | 64 (10.32%) | 570 (63.83%) | ||||

| 1-20 | 29 (6.71%) | 15 (7.98%) | 44 (7.10%) | 32 (3.58%) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 21-40 | 75 (17.36%) | 43 (22.87%) | 118 (19.03%) | 121 (13.55%) | ||||

| > 40 | 297 (68.75%) | 97 (51.60%) | 394 (63.55%) | 170 (19.04%) | ||||

P-value for the comparison between COPD cases with lung cancer and COPD cases without lung cancer.

P-value for the comparison between COPD cases with lung cancer and controls.

P-value for the comparison between COPD cases without lung cancer and controls.

P-value for the comparison between all COPD cases and controls.

Among the 405 SNPs, 21 SNPs in 12 genes were found to be significant; 13 of the 21 SNPs are from 7 genes in GSH pathway (ABCC1, ABCC2, ABCC3, ABCC4, GCLC, GSS, and GSTP1), 7 from 4 genes in the DNA repair pathway (ERCC2, MSH3, PARP, and XPA), and 1 from the PTGS2 gene in the inflammatory response pathway (Table 2). The detailed SNP-based association results under the additive, dominant, and recessive genetic models using the complete dataset and the stratified dataset for lung cancer status are described in the Supplementary Appendix, Tables E2-E3.

Table 2.

Significant Results in Single SNP Analysis Adjusting for Clinical Variables

| Pathway | Gene | RS ID | Most Significant Results in Three Genetic Models: Odds Ratio (99% Confidence Interval) and P-Value |

Minimum P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Case-Control Dataset | COPD Patients without Lung Cancer and Healthy Control Dataset | COPD Patients with Lung Cancer and Healthy Control Dataset | ||||

| GSH | ABCC1 | rs16967755 | 1.51(1.08 -2.10) | 1.50(0.95 -2.38) | 1.45(1.00 -2.10) | 1.60×10-3 |

| 1.60×10-3 | 2.36×10-2 | 1.01×10-2 | ||||

| GSH | ABCC4 | rs7324283 | 1.90(1.07 -3.37) | 2.40(1.17 -4.91) | 1.58(0.83 -3.04) | 1.60×10-3 |

| 3.93×10-3 | 1.60×10-3 | 6.88×10-2 | ||||

| GSH | GCLC | rs12524550 | 2.42(1.11 -5.28) | 2.60(0.92 -7.34) | 2.11(0.91 -4.90) | 3.54×10-3 |

| 3.54×10-3 | 1.79×10-2 | 2.28×10-2 | ||||

| GSH | GCLC | rs2100375 | 0.75(0.58 -.97) | 0.33(0.10 -1.04) | 0.78(0.58 -1.03) | 3.66×10-3 |

| 3.66×10-3 | 1.25×10-2 | 2.29×10-2 | ||||

| GSH | ABCC3 | rs8075406 | 0.70(0.50 -.97) | 0.65(0.41 -1.02) | 0.70(0.48 -1.01) | 4.88×10-3 |

| 4.88×10-3 | 1.45×10-2 | 1.17×10-2 | ||||

| GSH | ABCC4 | rs1729786 | 1.61(1.01 -2.56) | 1.43(1.03 -2.00) | 1.59(0.94 -2.70) | 5.67×10-3 |

| 8.91×10-3 | 5.67×10-3 | 2.29×10-2 | ||||

| GSH | GCLC | rs542914 | 0.78(0.62 -.99) | 0.80(0.58 -1.11) | 0.78(0.60 -1.02) | 6.26×10-3 |

| 6.26×10-3 | 7.70×10-2 | 1.68×10-2 | ||||

| GSH | GCLC | rs4712035 | 1.37(1.01 -1.86) | 1.38(0.86 -2.21) | 1.36(0.97 -1.90) | 7.01×10-3 |

| 7.01×10-3 | 8.41×10-2 | 1.76×10-2 | ||||

| GSH | GSTP1 | rs1138272 | 0.64(0.41 -1.00) | 0.76(0.42 -1.36) | 0.60(0.36 -.99) | 8.19×10-3 |

| 9.80×10-3 | 2.20×10-1 | 8.19×10-3 | ||||

| GSH | ABCC2 | rs717620 | 1.28(0.96 -1.72) | 1.87(0.57 -6.12) | 1.39(1.01 -1.94) | 8.80×10-3 |

| 2.77×10-2 | 1.74×10-1 | 8.80×10-3 | ||||

| GSH | GSS | rs6088659 | 0.29(0.09 -.99) | 0.39(0.07 -2.06) | 0.23(0.05 -1.01) | 9.22×10-3 |

| 9.22×10-3 | 1.47×10-1 | 1.06×10-2 | ||||

| GSH | ABCC2 | rs2756109 | 0.79(0.62 -1.00) | 0.69(0.43 -1.11) | 0.80(0.61 -1.04) | 9.34×10-3 |

| 9.34×10-3 | 4.35×10-2 | 2.55×10-2 | ||||

| GSH | ABCC1 | rs215100 | 0.65(0.38 -1.12) | 0.65(0.30 -1.41) | 0.76(0.58 -1.00) | 9.69×10-3 |

| 3.99×10-2 | 1.52×10-1 | 9.69×10-3 | ||||

| DNA | MSH3 | rs12513549 | 4.04(0.72 -22.80) | 8.68(1.36 -55.26) | 1.35(0.89 -2.05) | 2.63×10-3 |

| 3.75×10-2 | 2.63×10-3 | 6.64×10-2 | ||||

| DNA | XPA | rs1800975 | 0.85(0.62 -1.18) | 0.60(0.38 -.94) | 0.99(0.69 -1.42) | 3.33×10-3 |

| 2.05×10-1 | 3.33×10-3 | 9.26×10-1 | ||||

| DNA | PARP | rs11842915 | 1.26(0.93 -1.69) | 1.53(1.02 -2.28) | 1.14(0.77 -1.68) | 6.43×10-3 |

| 4.79×10-2 | 6.43×10-3 | 3.81×10-1 | ||||

| DNA | ×10RCC2 | rs3916874 | 1.31(1.01 -1.70) | 1.56(1.00 -2.46) | 1.28(0.96 -1.71) | 7.40×10-3 |

| 7.40×10-3 | 1.08×10-2 | 2.63×10-2 | ||||

| DNA | MSH3 | rs33013 | 0.72(0.52 -1.00) | 0.80(0.51 -1.26) | 0.69(0.48 -.99) | 8.42×10-3 |

| 1.01×10-2 | 2.11×10-1 | 8.42×10-3 | ||||

| DNA | MSH3 | rs12522132 | 2.17(0.58 -8.09) | 4.49(1.03 -19.52) | 1.22(0.83 -1.82) | 8.54×10-3 |

| 1.31×10-1 | 8.54×10-3 | 1.86×10-1 | ||||

| DNA | MSH3 | rs2897298 | 2.28(0.62 -8.32) | 4.48(1.03 -19.47) | 1.21(0.81 -1.79) | 8.58×10-3 |

| 1.03×10-1 | 8.58×10-3 | 2.17×10-1 | ||||

| Inflammation | PTGS2 | rs689470 | 2.26(0.96 -5.36) | 3.02(1.05 -8.71) | 1.96(0.72 -5.32) | 7.03×10-3 |

| 1.47×10-2 | 7.03×10-3 | 8.41×10-2 | ||||

Twelve htSNPs from 8 genes (ABCC1, ABCC2, ABCC3, ABCC4, GCLC, GSTP1, GSS, and ERCC2) showed significant associations with COPD in the whole dataset (0.0016<p<0.0098); four htSNPs from four genes (ABCC1, ABCC2, GSTP1, and MSH3) were significant (0.00819<p<0.00969) in the subset of COPD with lung cancer; and eight htSNPs from five genes (ABCC4, PARP, MSH3, XPA, and PTGS2) were significant in the subset of COPD without lung cancer, (0.00858<p<0.0016). Specifically, two htSNPs from the ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 4 (ABCC4) gene were significant in both the whole dataset and the subset of COPD without lung cancer; and one htSNP from the glutathione S-transferase pi 1(GSTP1) gene was strongly associated with COPD in both the whole dataset and the subset of COPD with lung cancer.

Gene-based analysis results

Although included in this study were all 56 htSNPs selected from the HapMap data of CEU subjects, only 52 genes with more than one htSNP each could be tested in the gene-based association analyses. Five of the 52 genes were found to be significantly associated with COPD (GCLC, GSS, GSTO2, ERCC1, and RRM1), as shown in Table 3. Glutamate-cysteine catalytic subunit (GCLC) from the GSH metabolism pathway showed a very strong association with COPD in all three data sets (P<0.001); Glutathione s-transferase omega 2 (GSTO2) was significant in both the whole dataset and the subset of COPD with lung cancer (P = 0.003 and 0.001, respectively); Glutathione synthetase (GSS) and excision repair cross-complimenting rodent repair deficiency complementation group 1(ERCC1) were significant in the subset of COPD without lung cancer (P = 0.0001 and 0.008, respectively); and ribonucleotide reductase M1 (RRM1) was only associated with COPD in the combined dataset (P<0.01).

Table 3.

Significant Results Adjusting for Clinical Variables in Gene-Based Analysis

| Pathway | Gene | Number of SNPs Tested | Minimum P Value in Three Genetic Models |

Minimum P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Case-Control Dataset | COPD Patients without Lung Cancer and Healthy Control Dataset | COPD Patients with Lung Cancer and Healthy Control Dataset | ||||

| GSH | GCLC | 13 | 4.04×10-7 | 1.81×10-4 | 7.16×10-4 | 4.04×10-7 |

| GSH | GSS | 7 | 3.61×10-2 | 1.14×10-4 | 1.75×10-2 | 1.14×10-4 |

| GSH | GSTO2 | 6 | 3.30×10-3 | 5.05×10-1 | 1.06×10-3 | 1.06×10-3 |

| DNA | ×IORCC1 | 5 | 5.26×10-1 | 8.11×10-3 | 8.28×10-1 | 8.11×10-3 |

| DNA | RRM1 | 6 | 9.66×10-3 | 2.09×10-2 | 8.71×10-2 | 9.66×10-3 |

Cumulative risk assessment

Table 4 presents the estimated cumulative risk for multiple independent high-risk htSNPs is presented: there are 24 maximum high-risk alleles. Overall, regardless of lung cancer status, individuals carrying 10 to 12 high-risk alleles had a 62% increased risk of developing COPD compared to individuals who carried less than 10 high-risk alleles (OR=1.62, 99% CI= 1.06-2.49, P=0.004); those carrying more than 12 high-risk alleles had a nearly 3-fold increased risk compared to individuals carrying less than 10 high-risk alleles (OR=2.73, 99% CI= 1.72-4.34, P<0.001). The per-allele risk assessment demonstrated that, on average, each risk allele contributed a 21% increased risk of developing COPD (OR=1.21, 99% CI=1.12-1.30, P<0.001). The estimated cumulative effect of the number of high-risk alleles for COPD, separately with or without lung cancer, are also presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Cumulative Risk Prediction Model for COPD Based on Multiple Independent High Risk HtSNP Combination

| Number of Risk Alleles | Number of COPD Cases | Number of Healthy Controls | OR | S×10 | Z | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Whole Case-Control Dataset(12 risk htSNPs included) | ||||||

| First Level: [0,9] | 99 | 219 | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Second Level: [10,12] | 280 | 424 | 1.62 | 0.17 | 2.91 | 3.60×10-3 |

| Third Level: [13,24] | 241 | 250 | 2.73 | 0.18 | 5.61 | 2.07×10-8 |

| Per-allele risk (trend test) | 1.21 | 0.03 | 6.71 | 1.95×10-11 | ||

| 2. COPD Patients without Lung Cancer and Healthy Control Dataset (8 risk htSNPs included) | ||||||

| First Level: [0,2] | 30 | 247 | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Second Level: [3,5] | 108 | 496 | 1.67 | 0.24 | 2.19 | 2.83×10-2 |

| Third Level: [6,16] | 50 | 150 | 3.08 | 0.28 | 4.08 | 4.60×10-5 |

| Per-allele risk (trend test) | 1.25 | 0.05 | 4.76 | 1.94×10-6 | ||

| 3. COPD Patients with Lung Cancer and Healthy Control Dataset (4 risk htSNPs included) | ||||||

| First Level: [0,4] | 124 | 324 | 1.00(reference) | |||

| Second Level: [5,6] | 264 | 509 | 1.89 | 0.15 | 4.19 | 2.81×10-5 |

| Third Level: [7,8] | 44 | 60 | 2.32 | 0.27 | 3.10 | 1.94×10-3 |

| Per-allele risk (trend test) | 1.30 | 0.06 | 4.44 | 9.16×10-6 | ||

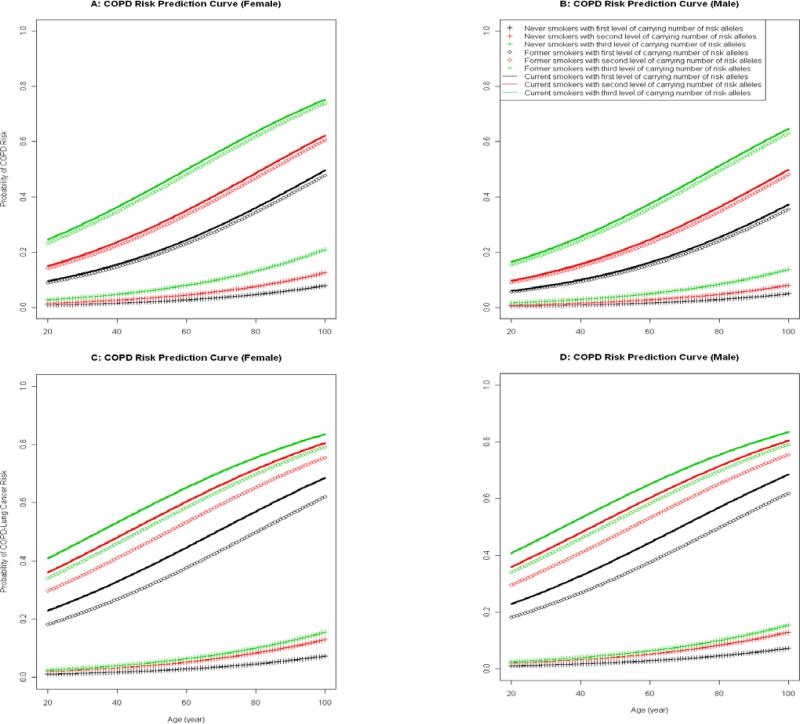

Figure 1 illustrates models for predicting the risk (or probability of developing) COPD in different strata by sex and smoking status, with and without lung cancer by age. Panels A and B show prediction curves of COPD risk for females and males without lung cancer, and panels C and D for females and males with lung cancer, respectively.

Figure.

Predicting Risk of COPD with and without Lung Cancer:

A: COPD Risk Prediction Curve (Female)

B: COPD Risk Prediction Curve (Male)

C: COPD Risk Prediction Curve (Female)

D: COPD Risk Prediction Curve (Male)

Discussion

We systematically evaluated associations of COPD risk with a full range of known polymorphisms in the glutathione metabolism, DNA repair, and inflammatory response pathways. We found that 21 SNPs in 12 genes (ABCC1, ABCC2, ABCC3, ABCC4, GCLC, GSTP1, GSS, ERCC2, MSH3, XPA, PARP, and PTGS2) were significantly associated with risk of COPD after adjusting for age, sex, and smoking status; 13 of the 21 SNPs were from 7 genes in the GSH metabolic pathway, 7 SNPs from 4 genes in the DNA repair pathway, and one from an inflammatory response gene. After stratifying COPD cases into subgroups with and without lung cancer, 4 htSNPs from 3 genes were significant in COPD with lung cancer, and 8 htSNPs from 5 genes were significant in COPD without lung cancer. These findings indicate that COPD and lung cancer share common susceptibility genes (i.e., ABCC4, and PTGS2), as well as hold independent susceptibility genes, i.e., ABCC1, ABCC2, GSTP1, and MSH3; the maximal sample size in the whole study dataset had improved statistic power to detect susceptibility loci for COPD, which could not be found in either sub-dataset.

Through a 52-gene based analysis using Fisher's combination test, 2 genes, GCLC and GSS, remained significant; an additional three genes, GSTO2, ERCC1, and RRM1, were also found to be strongly associated with COPD. The gene-based approach jointly considered all common variations of tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms (tagSNPs) within a candidate gene to capture all of the potential risk-conferring variations of the given gene, which improved the robustness of an identified association. However, the finding that a significant association was observed only from the SNP-based test but was not in the whole gene-based analysis for several genes (ABCC1, ABCC2, ABCC3, ABCC4, GSTP1, ERCC2, MSH3, XPA, PARP, and PTGS2) does not rule out their involvement in the etiology of COPD. Consistent with findings from other studies, our stratified analyses indicated that COPD and lung cancer have shared and independent susceptibility genes, which could serve as evidence for uncovering the common and unique mechanisms between COPD and lung cancer(2, 25, 26, 42-44) .

GSH holds an important role in protecting lung epithelial cells from injury and inflammation following a variety of insults, and is the most abundant antioxidant expressed in the lung resulting from the GSH metabolism pathway. GCLC, GSS, and GSTO2 are genes dominating the synthesis, modification, and activation of GSH. GCLC, the γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase heavy subunit controlling the important rate-limiting step in GSH synthesis (45). Multiple genetic variants in the GCLC gene may induce a different level of GSH production, altering the antioxidant capacity of airway cells and leading to increased susceptibility to COPD and/or lung cancer. Four of the 13 tested htSNPs in the GCLC gene showed significant associations with COPD and, the gene-based analysis found even a stronger association, indicating that multiple independent GCLC variants multiplicatively confer risk to COPD.

Glutathione synthetase (GSS), the key enzyme for GSH synthesis, plays an important role in defending the lung cell against reactive oxygen species (46, 47). The COPD-associated htSNP, rs6088659, is located in intron 1 of the GSS gene, which may be in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) with an alternative splicing variant, causing differential alternative splicing of the GSS gene. Glutathione S-transferase omega 2 (GSTO2) is a new yet important member of the gene superfamily of multifunctional enzymes that catalyze the conjugation of GSH with electrophilic substrates (48). Variation in GSTO2 may affect the catalytic activity of the rate-limiting step in arsenic biotransformation in humans (49). We detected a strong association of the GSTO2 gene with COPD with lung cancer, indicating that GSTO2 may be critical for developing cancer among COPD patients.

The excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair deficiency complementation group 1 gene (ERCC1) and ribonucleotide reductase M1 (RRM1) are two important genes in the DNA repair pathway. ERCC1, a structure-specific DNA repair endonuclease responsible for the 5' incision, has a key role in the removal of adducts from genomic DNA (50, 51). RRM1, a gene encoding the regulatory subunit of ribonucleotide reductase, influences cell survival and is an inhibitor of cell proliferation and suppresses cell migration and invasion by reducing the phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (52, 53). The expression levels of RRM1 and ERCC1 are significantly correlated (51, 53), and we found that ERCC1 was significantly associated with COPD without lung cancer and that RRM1 showed significance with all COPD, implying that ERCC1 may have a more important role in COPD etiology than in lung cancer etiology; whereas, RRM1 may affect both COPD and lung cancer susceptibility.

To appreciate the cumulative effects of multiple variants in different genes, we constructed a series of cumulative risk prediction models for COPD based on multiple high-risk htSNP combinations, serving as a translational portal of our study findings into potential clinical, basic science, and public health applications: first is risk prediction for COPD without or COPD with lung cancer; second is evidence for unique and common genes in COPD with and without further developing lung cancer, and third is relative importance of genetic versus environmental risk factors in developing COPD, with or without lung cancer. Noted is the impact of current and former smoking status, where the risk of COPD without lung cancer is lower in former smokers than in current smokers, the risk of COPD with lung cancer is virtually the same between the two smoking groups. This finding reiterates the benefits of smoking cessation in reducing COPD risk, which may also reduce the lung cancer risk.

Strengths of this study are summarized as follows: (1) Sample size is reasonably large from a single institution with a relatively recent patient population. (2) Phenotype of COPD is reliable, with diagnosis verified by medical records. (3) Gene and SNP selections are comprehensive, current or based on previously reported disease associations. Full htSNPs within each of these genes were used for capturing the genetic variation information. (4) Statistical analyses are comprehensive. Genetic association tests and replications should take place at the gene level because genes are the functional unit of the human genome; the positions, sequence, and function of genes are highly consistent across diverse human populations. In addition, gene-based replication implies that each population will be studied using their own allele frequencies and LD structure and should therefore overcome many of the problems of non-replication due to population differences in genetic structure. (5) A COPD risk prediction model was constructed to demonstrate the utilities of genetic markers and clinic information to achieve the goal of translational medicine. Finally, cross-validations between prediction models developed by independent research teams, e.g. Young et al, would accelerate this goal (44).

One disadvantage of using the existing resources as in our study design, specifically when involving a defined population or community is the incomplete diagnostic data for virtually any diseases, particularly for diseases that could be undiagnosed or underdiagnosed due to a lack of significant and specific symptoms. One exception is the clinical definition of chronic bronchitis, which requires mainly patients’ report on the presence of cough and sputum production for at least three months and for two consecutive years (37). Recognizing the low reliability of self-reported physician-diagnosed chronic bronchitis (54), we explicitly required in our study an answer to the clinical diagnosis of this disease from individuals who reported a physician-diagnosed chronic bronchitis. The specific question is, “Have you had an episode of cough and sputum production lasting 3 or more months for two consecutive years?” With regard to emphysema and lung cancer, our team recently published a study (55) demonstrating that clinical assessment, i.e., relying on either medical records or subjects-reported physician-diagnosed emphysema, has a fairly low sensitivity yet high specificity on detecting anatomic emphysema compared to that characterized by CT. Two implications to the current study are (1) underdiagnosing emphysema has been inevitable unless adequate resolution CT-scans were radiologically evaluated for the purpose of such specific diagnosis, and (2) as a consequence, most studies that attempted to estimate the burden of emphysema could only estimate the “physician-diagnosed” emphysema. Therefore, we had decided not to use the CT-scan-diagnosed emphysema or PFT (pulmonary function test) values that were available for virtually all subjects with lung cancer but only available for selected subjects without lung cancer, regardless of COPD phenotypes.

We acknowledge three additional limitations that need to be addressed in future studies: First, the limited sample size of the never smoker subgroup prohibited us to conduct stratified analyses by smoking status. Second, the number of COPD cases without lung cancer is small and therefore subject to chance findings. Third, because this is a systematic replication study of previously reported candidate or risk-bearing pathways, we did not use the convergent Bonferroni correction method for correction of multiple comparisons but used a stringent P-value threshold of 0.01. Considering the deficiency of our study design, we emphasized that our results are preliminary and calling for more rigorously-designed validation studies.

In summary, our results provide additional evidence supporting associations of COPD with variations in GCLC, GSS, GSTO2, ERCC1, and RRM1 genes using individual htSNPs and combinational multi-locus analyses, confirming that genetic variations in the glutathione metabolic and DNA repair pathways indeed contribute to COPD risk in an U.S. European Ancestry population. Future studies should take systems genomic approaches to identify causative genetic variants, characterizing their functions, and assessing their common and unique relationship with COPD as well as lung cancer. The high-risk alleles identified may be used for risk prediction, early diagnosis, and proactive prevention of COPD as well as lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Susan Ernst, M.A., for her technical assistance with the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by U.S. National Cancer Institute grants, RO3 CA77118, RO1 CA80127, and RO1 CA84354, and Mayo Foundation Funds.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ABCC1

ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 1

- ABCC2

ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 2

- ABCC3

ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 3

- ABCC4

ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 4

- CEU

Caucasian

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- ERCC1

Excision repair cross-complimenting rodent repair deficiency complementation group 1

- ERCC2

Excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 2

- GCLC

Glutamate-cysteine catalytic subunit

- GSH

Glutathione

- GSS

Glutathione synthetase

- GSTO2

Glutathione s-transferase omega 2

- GSTP1

Glutathione S-transferase pi 1

- GWAS

Genome-wide association study

- htSNPs

Haplotype tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms

- LD

Linkage disequilibrium

- MSH3

MutS homolog 3

- PARP

Poly-(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PTGS2

Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2

- RRM1

Ribonucleotide reductase M1

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- tagSNP

Tagging single nucleotide polymorphism

- χ2

Chi-squared

- XPA

Xeroderma pigmentosum, complementation group A

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Yang IA, Relan V, Wright CM, Davidson MR, Sriram KB, Savarimuthu Francis SM, et al. Common pathogenic mechanisms and pathways in the development of COPD and lung cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15:439–56. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.555400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rooney C, Sethi T. The epithelial cell and lung cancer: the link between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer. Respiration. 2011;81:89–104. doi: 10.1159/000323946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celli BR, MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:932–46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laniado-Laborin R. Smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Parallel epidemics of the 21st century. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:209–24. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6010209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Christmas T, Black PN, Metcalf P, Gamble GD. COPD prevalence is increased in lung cancer, independent of age, sex and smoking history. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:380–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00144208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redline S, Tishler PV, Rosner B, Lewitter FI, Vandenburgh M, Weiss ST, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic similarities in pulmonary function among family members of adult monozygotic and dizygotic twins. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:827–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silverman EK. Genetic Epidemiology of COPD. Chest. 2002;121:1S–6S. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.3_suppl.1s-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandford AJ, Silverman EK. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 1: Susceptibility factors for COPD the genotype-environment interaction. Thorax. 2002;57:736–41. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.8.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang P, Sun Z, Krowka MJ, Aubry MC, Bamlet WR, Wampfler JA, et al. Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency Carriers, Tobacco Smoke, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and Lung Cancer Risk. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1097–103. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.10.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lieberman J, WInter B, Sastre A. Alpha 1-Antitrypsin Pi-Types in 965 COPD Patients. Chest. 1986;89(3):370–3. doi: 10.1378/chest.89.3.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brody JS, Spira A. State of the art. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inflammation, and lung cancer. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2006;3:535–7. doi: 10.1513/pats.200603-089MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang SF, Xu YJ, Xie JG, Zhang ZX. hOGG1 Ser326Cys and XRCC1 Arg399Gln polymorphisms associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chin Med J (Engl) 2009;122:960–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siedlinski M, Postma DS, van Diemen CC, Blokstra A, Smit HA, Boezen HM. Lung function loss, smoking, vitamin C intake, and polymorphisms of the glutamatecysteine ligase genes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:13–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1749OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zidzik J, Slaba E, Joppa P, Kluchova Z, Dorkova Z, Skyba P, et al. Glutathione S-transferase and microsomal epoxide hydrolase gene polymorphisms and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Slovak population. Croatian medical journal. 2008;49:182–91. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2008.2.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen M, Vermeulen R, Chapman RS, Berndt SI, He X, Chanock S, et al. A report of cytokine polymorphisms and COPD risk in Xuan Wei, China. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2008;211:352–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang P, Li Y, Jiang R, Cunningham JM, Li Y, Zhang F, et al. A rigorous and comprehensive validation: Common genetic variations and lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:240–4. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vibhuti A, Arif E, Mishra A, Deepak D, Singh B, Rahman I, et al. CYP1A1, CYP1A2 and CYBA gene polymorphisms associated with oxidative stress in COPD. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:474–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Punturieri A, Szabo E, Croxton TL, Shapiro SD, Dubinett SM. Lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: needs and opportunities for integrated research. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:554–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang P, Ebbert JO, Sun Z, Weinshilboum RM. A Role of the Glutathione Metabolic Pathway in Lung Cancer Treatment and Prognosis: A Review. J Clin Oncol. 2005;24:1761–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samara K, Zervou M, Siafakas NM, Tzortzaki EG. Microsatellite DNA instability in benign lung diseases. Respir Med. 2006;100:202–11. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanbaeva DG, Dentener MA, Creutzberg EC, Wouters EF. Systemic inflammation in COPD: is genetic susceptibility a key factor? COPD. 2006;3:51–61. doi: 10.1080/15412550500493436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Hay BA, Epton MJ, Black PN, Gamble GD. Lung cancer gene associated with COPD: triple whammy or possible confounding effect? Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1158–64. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00093908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young RP, Whittington CF, Hopkins RJ, Hay BA, Epton MJ, Black PN, et al. Chromosome 4q31 locus in COPD is also associated with lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:1375–82. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00033310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang F, Todd NW, Li R, Zhang H, Fang H, Stass SA. A panel of sputum-based genomic marker for early detection of lung cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:1571–8. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parimon T, Chien JW, Bryson CL, McDonell MB, Udris EM, Au DH. Inhaled corticosteroids and risk of lung cancer among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:712–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1125OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saccone NL, Culverhouse RC, Schwantes-An TH, Cannon DS, Chen X, Cichon S, et al. Multiple independent loci at chromosome 15q25.1 affect smoking quantity: a meta-analysis and comparison with lung cancer and COPD. PLoS genetics. 2010:6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakhdar R, Denden S, Mouhamed MH, Chalgoum A, Leban N, Knani J, et al. Correlation of EPHX1, GSTP1, GSTM1, and GSTT1 genetic polymorphisms with antioxidative stress markers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Exp Lung Res. 2011;37:195–204. doi: 10.3109/01902148.2010.535093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boelens MC, Gustafson AM, Postma DS, Kok K, van der Vries G, van der Vlies P, et al. A chronic obstructive pulmonary disease related signature in squamous cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2011;72:177–83. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hung RJ, McKay JD, Gaborieau V, Boffetta P, Hashibe M, Zaridze D, et al. A susceptibility locus for lung cancer maps to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes on 15q25. Nature. 2008;452:633–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKay JD, Hung RJ, Gaborieau V, Boffetta P, Chabrier A, Byrnes G, et al. Lung cancer susceptibility locus at 5p15.33. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1404–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amos CI, Wu X, Broderick P, Gorlov IP, Gu J, Eisen T, et al. Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat Genet. 2008;40:616–22. doi: 10.1038/ng.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho MH, Boutaoui N, Klanderman BJ, Sylvia JS, Ziniti JP, Hersh CP, et al. Variants in FAM13A are associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42:200–2. doi: 10.1038/ng.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Sheu CC, Ye Y, de Andrade M, Wang L, Chang SC, et al. Genetic variants and risk of lung cancer in never smokers: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:321–30. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70042-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pillai SG, Ge D, Zhu G, Kong X, Shianna KV, Need AC, et al. A genome-wide association study in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): identification of two major susceptibility loci. PLoS genetics. 2009;5:e1000421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hancock DB, Eijgelsheim M, Wilk JB, Gharib SA, Loehr LR, Marciante KD, et al. Meta-analyses of genome-wide association studies identify multiple loci associated with pulmonary function. Nat Genet. 2010;42:45–52. doi: 10.1038/ng.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taniguchi K, Yang P, Jett J, Bass E, Meyer R, Wang Y, et al. Polymorphisms in the Promoter Region of the Neutrophil Elastase Gene Are Associated with Lung Cancer Development. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1115–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Thoracic Society Lung Function Testing: Selection of Reference Values and Interpretative Strategies. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1202–18. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng G, Luo L, Siu H, Zhu Y, Hu P, Hong S, et al. Gene and pathway-based second-wave analysis of genome-wide association studies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chapman J, Whittaker J. Analysis of multiple SNPs in a candidate gene or region. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;32:560–6. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zaykin DV, Zhivotovsky LA, Czika W, Shao S, Wolfinger RD. Combining p-values in large-scale genomics experiments. Pharmaceutical statistics. 2007;6:217–26. doi: 10.1002/pst.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang JJ. Distribution of Fisher's combination statistic when the tests are dependent. J Statist Comput Simul. 2009 DOI: 10.1080/00949650802412607. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357:539–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Workman ML, Winkelman C. Genetic influences in common respiratory disorders. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;20:171–89, vi. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Hay BA, Epton MJ, Mills GD, Black PN, et al. A gene-based risk score for lung cancer susceptibility in smokers and ex-smokers. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:515–24. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2008.077107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahman I, van Schadewijk AA, Hiemstra PS, Stolk J, van Krieken JH, MacNee W, et al. Localization of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase messenger rna expression in lungs of smokers and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:920–5. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00179-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rahman I, Smith CA, Lawson MF, Harrison DJ, MacNee W. Induction of gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase by cigarette smoke is associated with AP-1 in human alveolar epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;396:21–5. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He Z, Li B, Yu L, Liu Q, Zhong N, Ran P. Suppression of oxidant-induced glutathione synthesis by erythromycin in human bronchial epithelial cells. Respiration. 2008;75:202–9. doi: 10.1159/000111569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uchida M, Sugaya M, Kanamaru T, Hisatomi H. Alternative RNA splicing in expression of the glutathione synthetase gene in human cells. Molecular biology reports. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitbread AK, Masoumi A, Tetlow N, Schmuck E, Coggan M, Board PG. Characterization of the omega class of glutathione transferases. Methods Enzymol. 2005;401:78–99. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)01005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yanbaeva DG, Wouters EF, Dentener MA, Spruit MA, Reynaert NL. Association of glutathione-S-transferase omega haplotypes with susceptibility to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Free Radic Res. 2009:1–6. doi: 10.1080/10715760903038440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niedernhofer LJ, Odijk H, Budzowska M, van Drunen E, Maas A, Theil AF, et al. The structure-specific endonuclease Ercc1-Xpf is required to resolve DNA interstrand cross-link-induced double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5776–87. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5776-5787.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ceppi P, Volante M, Novello S, Rapa I, Danenberg KD, Danenberg PV, et al. ERCC1 and RRM1 gene expressions but not EGFR are predictive of shorter survival in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with cisplatin and gemcitabine. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1818–25. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gautam A, Li ZR, Bepler G. RRM1-induced metastasis suppression through PTEN-regulated pathways. Oncogene. 2003;22:2135–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bobadilla A, Guerra S, Sherrill D, R. B. How accurate is the self-reported diagnosis of chronic bronchitis? Chest. 2002;122:1234–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.4.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Y, Krowka MJ, Qi Y, Katzmann JA, Song Y, Mandrekar SJ, et al. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency carriers, serum alpha 1-antitrypsin concentration, and non-small cell lung cancer survival. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:291–5. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820213fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.