Abstract

Background

The 'closing-in' phenomenon is defined as a tendency to close in on a model while copying it. This is one of several constructional apraxia observed in dementia, particularly in Alzheimer's disease (AD). The aim of this study was to investigate the usefulness of it in the differential diagnosis of AD and subcortical vascular dementia (SVD) and to clarify the factors associated with it.

Methods

We operationally defined and classified it into three types, namely overlap, adherent, and near type. We analyzed the incidence of it in patients with AD (n = 98) and SVD (n = 48).

Results

AD patients exhibited a significantly higher occurrence of it as compared to SVD patients. Among the different types of it, the overlap and adherent types occurred almost exclusively in AD patients. A discriminant analysis in AD subjects revealed that the scores obtained from the MMSE, CDR, Barthel index, and the Rey-Osterrieth complex figure test were correlated significantly with the occurrence of it. There was no statistical difference between the Q-EEG parameters of patients that exhibited the closing-in phenomenon and those that did not.

Conclusions

This study suggests that the closing-in phenomenon is phase- and AD-specific and might be a useful tool for the differential diagnosis of AD and SVD.

Background

Alzheimer's disease (AD) and vascular dementia (VD) are the most common causes of dementia. Accurate differential diagnosis is essential to initiate appropriate treatment and to provide information about the prognosis and factors that may affect the course of the illness [1-4]. However, VD is not a single illness; it is comprised of dementia due to large artery stroke, subcortical vascular (or small vessel) dementia (SVD), and other less frequently observed vascular lesions [5].

SVD affects the white matter and basal ganglia bilaterally and diffusely. It can lead to dementia that is characterized by impairment of behaviors, such as executive functioning, goal formation, initiation, planning, organizing, self maintenance, sequencing, and abstraction [6]. Whereas the cognitive impairments that follow a stroke tend to recede over time, SVD is often progressive and can be confused with AD. Stepwise deterioration and focal symptoms are not always symptoms of SVD [7]. Many previous neuropsychological studies comparing AD and VD have included multi-infarct patients or mixed groups of multi-infarct/SVD patients. Such heterogeneity in the definition of vascular dementia has contributed to conflicting neuropsychological test results in the differential diagnosis of dementia.

Although previous studies have revealed many aspects of the pathophysiology of AD, no specific biological markers for this disease have yet been detected. Therefore, the diagnosis of AD is primarily clinical and the disease cannot be diagnosed on the basis of laboratory findings alone. Moreover, diagnostic accuracy is lower in the early stages of AD, when the disease is often confused with other forms of dementia, particularly SVD [8,9]. The low level of diagnostic accuracy has stimulated a search for in vivo markers of AD, such as apolipoprotein E, that can be used to better differentiate AD from other forms of dementia.

However, none of the putative markers currently available show sufficient sensitivity or specificity. The lack of a generally acceptable in vivo marker for diagnosis of AD and the paramount importance of cognitive and behavioral symptoms in the clinical diagnosis of this disease have prompted some researchers to use neuropsychological methods to improve the discrimination of AD from other forms of dementia.

The abnormal behavioral patterns often observed in demented patients during the execution of visual-spatial tasks might be useful in differentiating AD from vascular forms of dementia. In 1935, Mayer Gross described the closing-in phenomenon, which is a tendency to close in on a model while performing a constructive task [10]. It is not clear whether the underlying pathophysiolgy is one manifestation of a larger disturbance, best interpreted as a difficulty in making an abstract copy from a concrete model through symbolization, or is simply a reflection of visuospatial dysfunction, but this unique phenomenon is recognized as one of the constructional apraxias often associated with AD. However, the contribution of the closing-in phenomenon to the differential diagnosis of dementia has remained uncertain, and the potential use of this test in diagnosing AD has not been explored in detail.

From a practical standpoint, investigations of the closing-in phenomenon are faced with the initial problem of clearly defining it, because there is a great deal of variety in the behavioral operations that are subsumed under the concept of the closing-in phenomenon. For example, Mayer Gross described a series of behaviors that were observed "in writing, drawing, in imitating finger postures, in copying mosaics"; these behaviors were collectively referred to as 'closing-in.' In the present study, we considered symptoms associated with the graphic aspect of the closing-in phenomenon, i.e., symptoms observed in subjects performing a graphic copying task. We defined the closing-in phenomenon as the tendency of a subject to make a copy of a model shape as close as possible to, or even within, the original as compared to younger control subjects.

The main purpose of this study was to perform a systematic comparison of the incidence and qualitative aspects of the closing-in phenomenon in AD and SVD patients (using current classifications of SVD and AD), and to evaluate the clinical value of this phenomenon in the differential diagnosis of AD and SVD.

Methods

Study population

The study was conducted between November 1998 and January 2003. Patients eligible for this study had a diagnosis of uncomplicated AD (n = 98) or SVD (n = 48). Two control groups of younger (n = 30) and older (n = 22) subjects without symptoms of dementia were enrolled. The diagnosis of AD was based on the criteria established by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA) [11]. SVD was diagnosed according to the criteria outlined by Erkinjuntti et al. (2000)[12]. AD and SVD patients also had to satisfy the criteria for dementia set out in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). Patients had mini-mental state examination (MMSE) [13] scores between 6 and 25 and a clinical dementia rating (CDR) of 1 (mild dementia), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe) [14]. Patients who had been taking cholinesterase inhibitors within one month of the commencement of the study were not included.

The following scales were quantified: the Barthel index [15], a scale for the activity of daily living; the geriatric depression scale (GDS) [16], a scale for depression; and the copying of the Rey-Osterrieth complex figure test (ROCFT) [17,18], a scale for constructional ability.

Demographic characteristics did not differ between AD and SVD patients. The mean ages for the AD and SVD groups were 76.92 and 76.75 years old, respectively. The mean CDR score, which reflects the severity of dementia, was not different between the AD and SVD patients (Table 1). In the AD group, the MMSE score and GDS were both significantly lower than in the SVD group, whereas the Barthel index was significantly higher in SVD than in AD patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of patients(mean ± standard deviation)

| Groups | Younger controls (N = 30) | Elderly controls (N = 22) | Alzheimer's disease (N = 98) | Small Vessel Dementia (N = 48) | P-value* |

| Sex (M : F) | 8:22 | 14 : 8 | 33 : 65 | 22 : 26 | NS |

| Age | 29.48 ± 5.90 | 67.30 ± 8.46 | 76.92 ± 8.03 | 76.75 ± 5.87 | NS |

| Age of onset | - | - | 73.27 ± 11.79 | 72.28 ± 12.61 | NS |

| Duration | - | - | 33.10 ± 23.10 | 26.30 ± 27.19 | NS |

| Education | 14.57 ± 0.98 | 10.43 ± 6.58 | 6.46 ± 5.47 | 6.96 ± 4.89 | NS |

| MMSE | 29.10 ± 1.21 | 28.12 ± 1.64 | 14.58 ± 5.67 | 16.58 ± 5.04 | 0.03 |

| Barthel index | 19.81 ± 0.21 | 19.11 ± 1.21 | 17.46 ± 4.53 | 11.26 ± 6.74 | 0.00 |

| CDR | - | - | 1.76 ± 0.76 | 1.77 ± 0.71 | NS |

| GDS | - | - | 16.37 ± 7.50 | 20.94 ± 4.97 | 0.04 |

*Statistical significance was tested between Alzheimer disease and Vascular dementia MMSE; Mini-Mental State Examination GDS; Geriatric Depression Scale CDR; Clinical Dementia Rating Scale

To exclude disorders other than AD and SVD, all patients underwent a full neurological examination, standard diagnostic laboratory tests, a neuropsychological investigation, and an MRI brain scan. In addition, quantitative electroencephalography (Q-EEG) was carried out to investigate electrophysiological changes in patients who exhibited the closing-in phenomenon.

Definition of the closing-in phenomenon

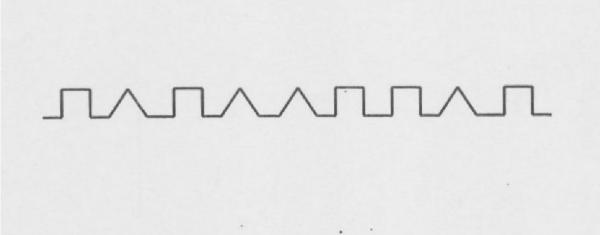

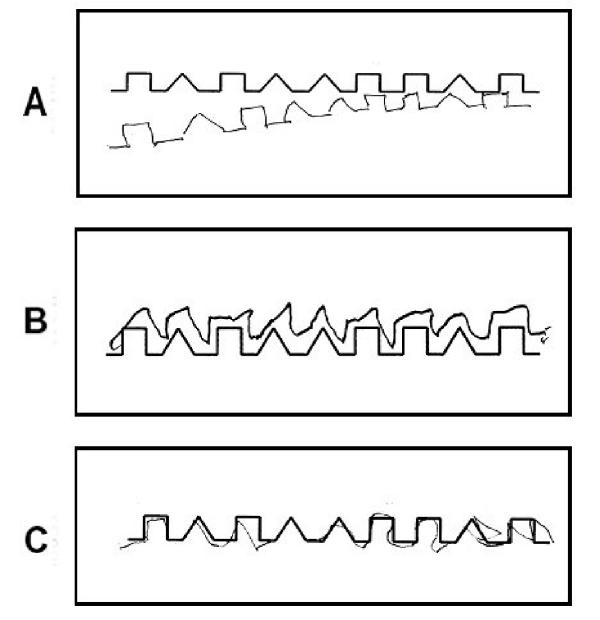

Though the closing-in phenomenon is also found ROCFT and MMSE double pentagon, the operational definition is very difficult, so the "Alternating Square and Triangle" task [19], simple and easy test to define this phenomenon, was chosen for operational definition. To define the closing-in phenomenon, the younger controls carried out a behavioral task in which they were required to copy shapes. A subject was asked by an examiner to draw a copy of a model shape below the original on A4 paper (Fig. 1), but was not provided with a suggested starting point. After completing this task, the distance between the starting and ending points between the original and copied shapes was analyzed statistically. Based on these observations, an analytical study allowed us to distinguish the following three different types of closing-in phenomena: (1) Overlap type – a tendency to overlap the lines of the model with the copy; (2) Adherent type – a tendency to make copies very close to, or adherent with, the model (difference > 3 standard deviations, as compared to copies made by younger controls; adherent type); (3) Near type – a tendency for the copy end point to be located close to the original model (distance between the starting point of the copy and the end point of the original model shape > 3 standard deviations, as compared to younger controls) (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

The "Alternating Square and Triangle" task in A4 paper

Figure 2.

Examples of subtypes of "closing-in" are shown, (A) near type (B) adherent type, (C) overlap type.

Spectral parameter analysis of Q-EEG

EEGs were carried out in a quiet room under continuous supervision. The conscious subjects were seated in a comfortable chair with their eyes closed. EEG traces were recorded from 20 electrodes located according to the 10–20 international system, with reference to linked mastoids, and stored on a computer (α-trace digital EEG, Best) for conventional visual inspection. The EEG was band pass-filtered at 1–64 Hz prior to digitizing, with a sampling rate of 128 Hz and a notch filter in each channel. Data were reviewed off-line. Fifteen 2-s epochs that were free of artifacts were selected for further processing. A spectral density function W (f) was calculated using fast Fourier transformation (FFT) [20]. The localized field power, which corresponds to the localized EEG amplitude (absolute and relative EEG power), was calculated for the following four frequency bands: 1–4 Hz (delta), 4–8 Hz (theta), 8–13 Hz (alpha) and 13–30 Hz (beta).

Final data values were normalized by logarithmic transformation. The locations of the generators for each frequency band were determined for the anterior (averaging power of F3, F4, F7, F8 leads), centrotemporal (averaging power of T4, C4 and T3, C3 leads), and posterior (averaging power of T6, P4, O2 and T5, P3, O1 leads) dimensions.

Diagnostic value and analysis of factors associated with the closing-in phenomenon

Based on our definition, the incidence of the closing-in phenomenon was obtained for each study group. The sensitivity and specificity of using closing-in for the differential diagnosis of AD and SVD were calculated. Finally, the factors associated with the closing-in phenomenon were analyzed in AD patients.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analyses, we used Student's t-test, the Chi-square test, one-way ANOVA, and discriminant analysis (SPSS ver. 8.0). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Incidence of the closing-in phenomenon

Although some patients were unable to complete the drawing task (deformed drawing group), the incidence of the closing-in phenomenon was significantly higher in the AD group than in the SVD group (p = 0.043). With the exception of one patient, the overlap and adherent type of closing-in were observed exclusively in AD patients. The sensitivity and specificity of the closing-in phenomenon in the AD groups were 51.9% (41/79 patients) and 71.1% (27/38), respectively (Table 2). The closing-in phenomenon occurred mostly in patients with dementia, but was not confined to the AD and SVD groups. For example, two of the elderly controls (subjects without dementia) exhibited the near type of closing-in phenomenon (9.1%, 2/22).

Table 2.

Frequency of "closing-in" phenomenon among study groups.

| Groups | Younger controls (N = 30) | Elderly control (N = 22) | Alzheimer's Disease* (N = 98) | Small Vessel Dementia* (N = 48) |

| Closing-in(-) | 30 | 20 | 38 | 27 |

| Closing-in(+) | ||||

| Overlap | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 |

| Adherent | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Near | 0 | 2 | 29 | 10 |

| Deformed drawing | 0 | 0 | 19 | 10 |

*Statistical significance was found between Alzheimer's disease and Small Vessel dementia(p-value; 0.043)

The associated factors of the closing-in phenomenon in AD patients

To clarify the factors associated with the closing-in phenomenon in AD patients, discriminant analysis was carried out. The MMSE score, Barthel index, CDR score, and ROCFT score were each found to be correlated significantly with the occurrence of the closing-in phenomenon. Other factors, including sex, education level, early onset, and GDS score were unrelated to the incidence of the closing-in phenomenon (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical differences between Alzheimer patients with "closing-in" and without "closing-in" phenomenon (mean ± standard deviation).

| Variables | Closing-in(-) (N = 38) | Closing-in(+) (N = 41) | Deformed (N = 19) | p-value* |

| Sex Male | 12 | 15 | 6 | 0.875 |

| Female | 26 | 26 | 13 | |

| Education(year) | 8.20 ± 5.17 | 7.39 ± 5.13 | 6.89 ± 5.35 | 0.240 |

| Age at onset ≤ 65 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 0.322 |

| >65 | 31 | 32 | 13 | |

| Apolipoprotein E 4 ≥ 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 0.827 |

| E 4 < 1 | 10 | 13 | 10 | |

| Symptom duration (month) | 31.2 ± 23.4 | 30.8 ± 23.0 | 42.4 ± 21.9 | 0.202 |

| MMSE** | 17.31 ± 5.03 | 14.83 ± 5.07 | 8.89 ± 3.80 | 0.000 |

| GDS | 15.64 ± 7.17 | 17.62 ± 7.67 | 13.85 ± 8.17 | 0.378 |

| Barthel index*** | 18.38 ± 4.42 | 17.89 ± 3.57 | 14.37 ± 5.66 | 0.008 |

| CDR*** | 1.49 ± 0.70 | 1.68 ± 0.70 | 2.42 ± 0.61 | 0.000 |

| ROCFT** | 18.13 ± 9.40 | 9.56 ± 9.01 | 1.90 ± 1.71 | 0.000 |

* Statistical test was done by discriminant function analysis ** Statistical significance was found among study groups ***Statistical significance was found between patients with "closing-in" and deformed. MMSE; Korean Mini-Mental State Examination GDS; geriatric depression scale CDR; clinical dementia rating scale ROCFT; Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test Apoprotein E allele was not checked in all cases.

Differences in the Q-EEG field power among AD patients

To quantify differences in the field power of AD associated with the closing-in phenomenon, Q-EEG data were recorded and analyzed. The delta spectral power tended to increase relative to the theta spectral power and decrease relative to the alpha and beta spectral powers in AD patients who exhibited the closing-in phenomenon, as compared to those AD patients that did not. However, none of these differences was statistically significant. The relative alpha spectral power was significantly lower in the deformed drawing group than in the other groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Relative spectral power of qEEG in Alzheimer disease with "closing-in" and without "closing-in" phenomenon.

| Closing-in(-) (N = 38) | Closing-in(+) (N = 41) | Deformed (N = 19) | p-value* | ||

| Anterior field | Delta | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 1.09 ± 0.16 | 1.05 ± 0.13 | 0.446 |

| Theta | 1.09 ± 0.12 | 1.11 ± 0.17 | 1.14 ± 0.13 | 0.591 | |

| Alpha** | 1.13 ± 0.12 | 1.10 ± 0.08 | 1.01 ± 0.08 | 0.009 | |

| Beta | 1.38 ± 0.08 | 1.36 ± 0.08 | 1.34 ± 0.07 | 0.317 | |

| Centrotemporal field | Delta | 0.95 ± 0.14 | 1.00 ± 0.17 | 1.01 ± 0.13 | 0.489 |

| Theta | 1.09 ± 0.13 | 1.11 ± 0.16 | 1.13 ± 0.13 | 0.672 | |

| Alpha** | 1.15 ± 0.12 | 1.12 ± 0.09 | 1.01 ± 0.08 | 0.004 | |

| Beta | 1.38 ± 0.07 | 1.36 ± 0.08 | 1.01 ± 0.08 | 0.545 | |

| Posterior field | Delta | 0.94 ± 0.14 | 0.98 ± 0.18 | 1.01 ± 0.14 | 0.446 |

| Theta | 1.10 ± 0.13 | 1.13 ± 0.15 | 1.14 ± 0.13 | 0.636 | |

| Alpha** | 1.20 ± 0.13 | 1.18 ± 0.12 | 1.03 ± 0.09 | 0.001 | |

| Beta | 1.37 ± 0.07 | 1.35 ± 0.08 | 1.34 ± 0.07 | 0.679 |

* One-way ANOVA test ** Statistical significance was found between deformed and other groups.

Discussion

Objects and patterns in space are interpreted according to the laws of perspective using higher cortical association systems. Thus, human behavior is influenced by spatial interpretation and lesions within the cortical systems that regulate such behavior lead to a disruption of spatial interpretation. Disruption of spatial interpretation is frequently observed in patients with AD and, therefore, understanding this phenomenon is important for understanding the clinical expression of dementia. In this regard, the closing-in phenomenon is particularly relevant for diagnostic purposes, because it is thought to be a dysfunction that is peculiar to AD.

The cause and anatomical origin of the closing-in phenomenon, and why this phenomenon is observed frequently in AD patients, are unclear. Mayer Gross stressed the value of this phenomenon as importantly supporting his interpretation of constructional apraxia, which he defined as a reduction in the optimal use of the hands in tasks carried out in "active space"; he also spoke of a fear of "empty space" [10]. Although a precise diagnosis of the patients examined by Gross cannot be made, all of the patients exhibited apraxia and three had focal neurological symptoms. Most of the patients in whom the closing-in phenomenon was observed also had dementia.

Gross suggested that patients find it increasingly difficulty to copy a model as cognitive dysfunction progresses. To cope with this problem, the patient tends to make copies that are very close or adherent to the model. If dementia is well advanced, the copy may overlap the model. Gross proposed that this phenomenon reflects the patient's fear of empty space. The closing-in phenomenon is potentially useful as a clinical tool for diagnosing AD; it is particularly valuable because it is straightforward, as compared to other tests that are used for the diagnosis of AD such as memory tests and assessments of other aspects of dementia. In addition, it has been demonstrated that the closing-in phenomenon constitutes a useful tool for making a differential diagnosis of AD, as it has low sensitivity (30%) and high specificity (97.5%) for AD [21,22]. Moreover, the closing-in phenomenon is more sensitive in detecting advanced as compared to mild AD [23].

In the present study, the closing-in phenomenon associated with AD did not have high sensitivity (51.9%, 41/79), suggesting that this phenomenon might be of limited value for the diagnosis of AD. However, this was contradicted by the observation that the closing-in phenomenon had high specificity (71.1%, 27/38), which suggests that this test might be useful for differential diagnosis between AD and SVD. A detailed analytical study of the closing-in phenomenon revealed that the near type was found not only in patients with dementia, but also in subjects without dementia. Nevertheless, overlap and the adherent type of closing-in phenomenon were found almost exclusively in AD patients (Table 2).

Although the closing-in phenomenon is regarded as a pathological symptom of AD that is not detected in elderly control subjects [22], we hypothesize that aging might be associated with an increase in the incidence of the closing-in phenomenon. This assertion is based on a comparison of data between elderly and younger control subjects (< 40 years old). Our results demonstrated that although the incidence is low (9.1%, 2/22), the near type of closing-in phenomenon occurs in some elderly subjects who do not exhibit any signs of dementia. This result confirms our hypothesis that the closing-in phenomenon is not only a pathological symptom of AD, but is also a physiological phenomenon that is related to the aging process. The main reason for the discrepancy between our results and those of previous studies may lie in differences between the experimental paradigms (the behavioral task), and in the definition and classification of the closing-in phenomenon. It is also possible that this discrepancy arose because the elderly control subjects examined in the present study were older than those included in the previous study (67.3 vs. 62.9 years) [22].

Interestingly, 2- to 3-year-old children exhibit a marked tendency towards the closing-in phenomenon, which decreases progressively with age, eventually becoming irrelevant after six years of age [23]. Therefore, in the various dissolution stages of dementia, the closing-in phenomenon might represent the re-emergence of a primitive 'magnetic reaction' pattern, much like the grasping pattern, sucking reflex, echolalia, and echopraxia, which are all functions supported by a neurological apparatus that is built in from birth [24,25]. These primitive forms of behavior, which are characterized by reflex actions that are prompt and regular, would seem to be a necessary preface to corresponding types of learning. In advanced dementia, these behaviors re-emerge, as the higher cortical centers become increasingly unable to inhibit such reflex behavior patterns [23]. Although such behavior patterns in children and demented adults are not identical, these findings suggest that evolutionary and dissolution behavior patterns might be similar [26].

Although the closing-in phenomenon has been well characterized as a physiological or pathological phenomenon that is closely related to age, the anatomical localization of this phenomenon is not yet certain. The observation that the closing-in phenomenon is more common in AD than in SVD patients suggests that anatomical localization is not confined to a prefrontal circuit (which is the primary anatomical lesion in SVD), but is instead more widespread. To clarify the factors that are associated with the closing-in phenomenon in AD, discriminant analysis was carried out; the results indicated that the MMSE score, Barthel index, CDR score, and the copying of ROCFT are significantly related with the closing-in phenomenon. As most of these factors do not provide a definitive anatomical localization but, rather, characterize a particular stage of the disease, their value for understanding anatomical pathology is limited. However, the copying of the ROCFT test, which requires visual memory, planning, and organizational skills, reflects the comprehensive function of the frontal and parietal lobes [27]. Therefore, the close association between the closing-in phenomenon and the ROCFT test suggests the involvement of these widespread anatomical locations.

The relative alpha spectral Q-EEG power was significantly lower in the deformed drawing group than in the other groups, in all fields. However, there were no significant changes in spectral power between groups that did and did not exhibit the closing-in phenomenon. Therefore, the Q-EEG data do not suggest any anatomical localization for the closing-in phenomenon.

In conclusion, the results of the present study indicate that the closing-in phenomenon is valuable in the differential diagnosis of AD. In addition, although this phenomenon is disease-specific, it is also a phase-specific marker that is predominant in moderately advanced dementia (Table 3). Anatomical localization of this phenomenon is uncertain, but might be related to widespread brain regions. Although they were not assessed precisely for the limited number of cases in the present study, the overlap and adherent subtypes of the closing-in phenomenon occurred almost exclusively in AD patients. Therefore, if these subclasses are included, the closing-in phenomenon is both a specific and sensitive tool for the differential diagnosis of AD and SVD, suggesting that further clinical study might yield promising results.

Competing interests

None declared.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

References

- Gorelick PB, Roman G, Mangone CA. Vascular dementia. In: Gorelick PB, Alter MA, editor. Handbook of Neuroepidemiology. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1994. pp. 197–214. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick PB. Stroke prevention. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:347–354. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540280029015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Friedhoff T, and the Donepezil Study Group The efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease: results of a US multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Dementia. 1996;7:293–303. doi: 10.1159/000106895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rösler M, Anand R, Cicin-Sain A, Gauthier S, Agid Y, Dal-Bianco P, Stahelin HB, Hartman R, Gharabawi M. Efficacy and safety of rivastigmine in patients with Alzheimer's disease: international randomized controlled study. BMJ. 1999;318:633–638. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7184.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb C, Meyer JS. Vascular dementia: still a debatable entity? J Neurol Sci. 1996;143:31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(96)00191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler JV, Hachinski V. Vascular cognitive impairment: a new approach to vascular dementia. Bailliere's Clin Neurol. 1995;4:357–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoni L, Garcia JH, Brown GG. Vascular pathology in three cases of progressive cognitive deterioration. J Neurol Sci. 1996;135:131–139. doi: 10.1016/0022-510X(95)00273-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien MD. Vascular dementia is underdiagnosed. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:797–798. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520310115025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukull WA, Larson EB, Reifler BV, Lampe TH, Yerby MS, Hughes JP. The validity of 3 clinical diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1990;40:1364–1369. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.9.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer GW. Some observations on apraxia. Proc R Soc Med. 1935;28:1203–1212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under Auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkinjuntti T, Inzitari D, Pantoni L, Wallin A, Scheltens P, Rockwood K, Roman GC, Chui H, Desmond DW. Research criteria for subcortical vascular dementia in clinical trials. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2000;59:23–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6781-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. 'Mini-mental state'. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney FT, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatry Res. 1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterrieth PA. Le test de copie d'une figure complexe. Arch de Psychologie. 1944;30:206–356. [Google Scholar]

- Stern RA, Singer EA, Duke LM. The Boston Qualitative Scoring System for the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure: description and interrater reliability. Clin Neuropsychologist. 1944;8:309–322. [Google Scholar]

- Luria AR. Human brain and psychological processes. New York, Harper and Row; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Bendat JS, Piersol AP. Random Data Analysis and Measurement Procedures. 2. New York: Wiley Interscience Press; 1986. pp. 121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gainotti G, Parlato V, Monteleone D, Carlomagno S. Neuropsychological markers of dementia on visual-spatial tasks: a comparison between Alzheimer's type and vascular forms of dementia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1992;14:239–252. doi: 10.1080/01688639208402826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainotti G, Marra C, Villa G, Parlato V, Chiarotti F. Sensitivity and specificity of some neuropsychological markers of Alzheimer dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1988;12:152–162. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainotti G. A quantitative study of the "closing-in" symptom in normal children and in brain-damaged patients. Neuropsychologia. 1972;10:429–436. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(72)90005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajuriaguerra J, de Muller M, Tissot R. A propos de quelques problemes poses par l'apraxie dans les demences. Encephale. 1960;49:375–401. doi: 10.1016/S0013-7006(10)70025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twitcbell TE. The automatic grasping responses of infants. Neuropsychologia. 1965;3:247–259. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(65)90027-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Franssen EH, Souren LE, Auer SR, Akram I, Kenowsky S. Evidence and mechanisms of retrogenesis in Alzheimer's and other dementias: management and treatment import. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2002;17:202–212. doi: 10.1177/153331750201700411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loring DW, Lee GP, Meador KJ. Revising the Rey-Osterrieth: Rating right hemisphere recall. Arch Clin Neuropsychology. 1988;3:239–247. doi: 10.1016/0887-6177(88)90017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]