Abstract

Background:

Many academic medical centres have introduced strategies to assess the productivity of faculty as part of compensation schemes. We conducted a systematic review of the effects of such strategies on faculty productivity.

Methods:

We searched the MEDLINE, Healthstar, Embase and PsycInfo databases from their date of inception up to October 2011. We included studies that assessed academic productivity in clinical, research, teaching and administrative activities, as well as compensation, promotion processes and satisfaction.

Results:

Of 531 full-text articles assessed for eligibility, we included 9 articles reporting on eight studies. The introduction of strategies for assessing academic productivity as part of compensation schemes resulted in increases in clinical productivity (in six of six studies) in terms of clinical revenue, the work component of relative-value units (these units are nonmonetary standard units of measure used to indicate the value of services provided), patient satisfaction and other departmentally used standards. Increases in research productivity were noted (in five of six studies) in terms of funding and publications. There was no change in teaching productivity (in two of five studies) in terms of educational output. Such strategies also resulted in increases in compensation at both individual and group levels (in three studies), with two studies reporting a change in distribution of compensation in favour of junior faculty. None of the studies assessed effects on administrative productivity or promotion processes. The overall quality of evidence was low.

Interpretation:

Strategies introduced to assess productivity as part of a compensation scheme appeared to improve productivity in research activities and possibly improved clinical productivity, but they had no effect in the area of teaching. Compensation increased at both group and individual levels, particularly among junior faculty. Higher quality evidence about the benefits and harms of such assessment strategies is needed.

Academic productivity can be defined as a measurable output of a faculty member related to clinical, research, education or administrative activities. Achieving the best possible academic productivity is essential for academic medical centres to maintain or nurture recognition and good reputation.1 Furthermore, clinical productivity is essential for the survival of academic departments given the economic realities in medicine.2

Strategies for productivity assessment help in identifying highly productive faculty, determining areas for faculty and departmental improvement,3 and implementing processes for promotion and tenure.4 When coupled with reward schemes, these strategies may improve productivity and compensation at both individual and departmental levels. In the long-term, they may enhance the ability to recruit and retain high-quality faculty and achieve the academic mission of the department. However, these strategies may have some unintended effects such as using time dedicated to education to do more clinical work.3 In addition, they may be challenging to implement.3

We conducted a systematic review of the effects of strategies introduced in academic medical centres to assess faculty productivity, compensation, promotion processes and satisfaction.

Methods

We defined productivity as a measurable activity or a measurable output of an activity of a faculty member. The considered areas of activity were clinical, research, teaching and administration.

Literature search

We searched the following databases from their date of inception up to October 2011: MEDLINE, Healthstar, Embase and PsycInfo. The search strategies included no language or date restrictions (for details, see Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.111123/-/DC1). In addition, we screened the reference lists of included articles and relevant papers and used the “related article” feature in PubMed to identify additional studies. We contacted the authors of studies that described strategies but did not report on their effects, seeking any unpublished data. We also searched websites of academic institutions and contacted experts in the field as part of the scoping for this study.

Eligibility criteria

We included studies that evaluated faculty members in academic medical centres; assessed the effects of a productivity assessment strategy introduced as part of appointment, promotion, compensation or incentive schemes; and had either no active comparison or a comparison with the introduction of another productivity assessment strategy.

Our main outcome measure was the effect on productivity in at least one of four areas (clinical, research, teaching and administration) either at the individual (faculty) or group (department) level. Additional outcomes of interest were the effects on faculty compensation, promotion processes and satisfaction. We were also interested in other relevant academic, educational, clinical and financial outcomes as well as negative unintended consequences of the strategies.

We excluded reports if they described a productivity assessment strategy but not its effects on the outcomes of interest; if they described interventions not used as part of a productivity assessment strategy (e.g., pay for performance, evaluation of the quality of faculty teaching); and if the strategies were related to concepts such as benchmarking and faculty development. We did not include conference proceedings.

Data selection and abstraction

Pairs of two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of identified records for potential eligibility. We retrieved the full texts of citations judged to be potentially eligible by at least one reviewer. The groups of two reviewers then independently screened the full texts for eligibility and abstracted data using pilot-tested and standardized forms. They resolved their disagreements by discussion and, if necessary, with help from an arbiter. We contacted authors to verify our abstracted data.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the agreement between the reviewers for full-text screening using the kappa statistic. The studies used different outcome measurements and expressed results in various statistical formats, which precluded the conduct of meta-analyses. Thus, we summarized the results in narrative and tabular formats. We graded the quality of evidence using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach5 and assigned a grade of “high,” “moderate,” “low” or “very low.”

Results

Study selection

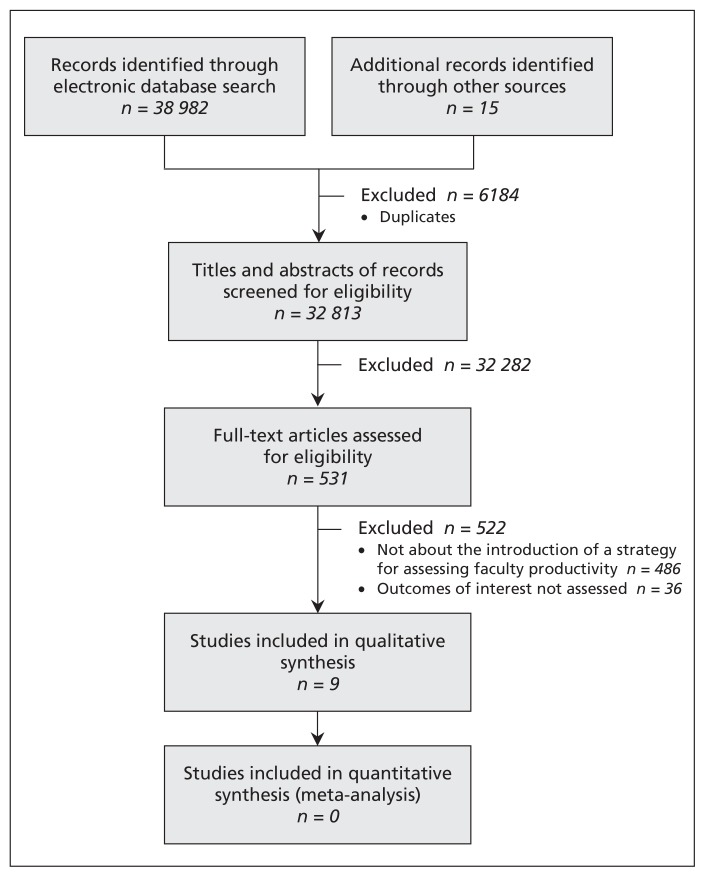

Figure 1 shows the selection of studies for our review. The nine eligible articles reported on eight studies that evaluated eight different productivity assessment strategies.3,6–13 Agreement between reviewers for study eligibility was high (κ value = 0.75). The authors of the eight studies verified our abstracted data. We learned that seven of the strategies are still in use either in their original form or in a modified version.6–13

Figure 1:

Selection of studies for the review.

Appendix 2 (available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.111123/-/DC1) summarizes 35 strategies described in 36 reports that we excluded for not reporting on their effects. Authors of nine of these reports responded to our emails, indicating they had no data available on the effects of their strategies.

Features of the strategies

Details of the eight productivity assessment strategies evaluated in the included studies are summarized in Table 1. The strategies were reported between 1999 and 2008.

Table 1:

Description of strategies for the assessment of productivity of faculty reported by included studies

| Study | Development of strategy | Areas of productivity assessed | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Research | Teaching | Administrative | ||

| Garson et al., 19993 | Faculty survey, metrics committee, faculty feedback and testing |

|

|

|

Service on state/national committees |

| Cramer et al., 20006 | Comprehensive literature search, consensus process with faculty |

|

|

RVU based on number and type of teaching activity, course directorship, curriculum design, teaching award | No specific assessment method reported; compensation based on exceptional effort and special projects rewarded by the chair from an annual discretionary managerial incentive pool (5% of budgeted incentive funds) |

| Sussman et al., 20017 | Not reported | wRVU based on Medicare/Medicaid coding for evaluation and management | Not reported |

|

Discretionary payment to primary care physicians (1% of productivity- derived salary) based on commitment to group activities (e.g., arranging CME for the group, leading medical management meetings) |

| Andreae et al., 20028 | Not reported | No specific assessment method reported; compensation for research effort negotiated with the chair or unit director | wRVU teaching credit based on reported hours spent supervising medical students | No specific assessment method reported; compensation for administrative effort negotiated with the chair or unit director | |

| Tarquinio et al., 20039 | Not reported |

|

|

Not reported | Additional RVU credits for important administrative responsibilities such as division compliance expert, course director or fellowship program director |

| Miller et al., 200510* | Consultation with many groups, including private practitioners |

|

No specific assessment method reported; instead of financial rewards, educators receive additional nonclinical time | No specific assessment method reported; incentives based on teaching evaluations | Not reported |

| Reich et al., 200811 | Chairperson advised by two committees to create valuations for activities |

|

Point valuation scheme and valuation by a departmental committee based on faculty-submitted quarterly reports of academic activities | Point valuation scheme and valuation by the chair based on semi-annual evaluation by residents and peers | Point valuation scheme and valuation by the chair based on administrative functions assumed |

| Schweitzer et al., 200712 and 200813 | Committee of faculty and administrators |

|

|

|

|

Note: CME = continuing medical education, CPT = Current Procedural Terminology, FTE = full-time equivalent, MGMA = Medical Group Management Association, NIH = National Institutes of Health, RVU = relative-value unit (a nonmonetary standard unit of measure used to indicate the value of services provided; for a specific service, the RVU is multiplied by a conversion factor [dollar amount by unit of RVU] to calculate the total dollar amount assigned to that service), wRVU = work component of the RVU14 (under the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the RVU has three components: work, practice expense and professional liability insurance).

Strategy also described in Feiner et al.15

The development process was described for three strategies and included literature review, faculty input and creation of a special committee.3,6,11 The need for staff support for managing productivity assessment was reported for four strategies.3,6,8,11 Four strategies were described as offering either web-based access9,11 or regular feedback to faculty.8,10

A variable number of the reports provided specific and reproducible descriptions of the strategies for assessing the four areas of productivity: clinical (eight studies3,6–11,13), research (six3,6,9–11,13), teaching (six3,6–8,11,13) and administrative (four3,9,11,13). The strategies used one or more methods for assessing the different areas of productivity, but the methods were not consistent across these strategies. The main measurement methods used were the relative-value unit (six studies3,6–9,11), a rating scale determined by departmentally based standards (one13) and billable hours (one10). (The relative-value unit is a nonmonetary standard unit of measure used to indicate the value of services provided; for a specific service, the unit is multiplied by a conversion factor to calculate the total dollar amount assigned to that service.)

Features of the studies

Details of the included studies are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. All of the studies were conducted in the United States. In terms of design, all of the studies were conducted at a single institution and were designed for different institutional levels: six at the department level (four in primary care6,7–9 and two in anesthesiology10,11), one at the school level (school of medicine3) and one at the level of academic centre (at the centre’s schools of medicine, nursing and dentistry13). All of the studies compared data collected before with data collected after the implementation of the assessment strategy. Six studies explicitly reported a retrospective approach to data collection.3,6,7,10,11,13 The authors of the two remaining studies confirmed that data collection was prospective.8,9 None of the studies included an active comparator.

Table 2:

Design of studies evaluating the effects of the productivity assessment strategies

| Study (setting) | Design | Population | Intervention | Risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garson et al.3 (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas) | Retrospective before–after comparison | 17 clinical science departments and 8 basic science departments; n (faculty) not reported |

|

|

| Cramer et al.6 (Department of Family Medicine, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York) | Retrospective before–after comparison | n (faculty) = 38–49 |

|

|

| Sussman et al.7 (Division of General Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts) | Retrospective before–after comparison | Employed academic primary care physicians; n (faculty) = 64 |

|

|

| Andreae et al.8 (Division of General Pediatrics, University of Michigan Health, Ann Arbor, Michigan) | Before–after comparison (data collection probably prospective) | n (faculty) = 35 |

|

|

| Tarquinio et al.9 (Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee) | Prospective before–after comparison | 12 clinical divisions; n (faculty) = 338 |

|

|

| Miller et al.10 (Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Care, University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, California) | Retrospective before–after comparison | Faculty with surgical and obstetric anesthesia responsibilities at three hospitals; n (faculty) = 58 |

|

|

| Reich et al.11 (Department of Anesthesiology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York) | Retrospective before–after comparison | n (faculty) not reported |

|

|

| Schweitzer et al.12,13 (Health Sciences Center schools of dentistry, nursing and medicine, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky) | Retrospective before–after comparison | n (faculty) not reported |

|

|

Table 3:

Effects of strategies on faculty productivity and compensation

| Study | Clinical productivity | Research productivity | Teaching productivity | Compensation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garson et al.3 |

|

|

Not assessed | Not assessed |

| Cramer et al.6 |

|

|

|

Not assessed |

| Sussman et al.7 |

|

Not assessed | Not assessed |

|

| Andreae et al.8 |

|

Not assessed |

|

|

| Tarquinio et al.9 |

|

|

|

|

| Miller et al.10 | Not assessed |

|

|

|

| Reich et al.11 |

|

|

|

|

| Schweitzer et al.12,13 | Not assessed | In the school of medicine:

|

Not assessed | Not assessed |

The study populations were either restricted to primary care physicians6–9 or anesthesiologists,10,11 or they were more inclusive (i.e., one or more schools).3,13 Five studies reported the number of participants: 338 faculty in one study,9 and a range from 35 to 64 faculty in the others.6–8,10

Of the eight studies, seven described the use of their productivity assessment as part of a compensation scheme.6–11,13 One of these seven studies reported the use of the assessment also as part of promotion and tenure standards.12

The numbers of studies assessing the outcomes of interest were as follows: clinical productivity (six3,6–9,11), research productivity (six3,6,9–12), teaching productivity (five6,8–11), administrative productivity (none), compensation (five7–11), promotion process (none) and other outcomes (two3,7).

Risk of bias and overall quality of evidence

All eight studies used historical controls, and six collected data retrospectively (Table 2).3,6,7,10,11,13 None of the studies used validated outcome measures. Many of the studies reported imbalanced co-interventions (e.g., training in billing,7,8,10 introduction of a new rank system9 or improvement in research infrastructure13 concomitant with the introduction of the intervention) or other confounding factors (e.g., better payer contract,7 concurrent increase in federal grant funding9). Although we could not formally assess it, publication bias was possible. Similarly, included studies did not report on all of the outcomes of interest, or they reported on one but not all relevant aspects of an outcome (e.g., they reported on clinical productivity at the individual level but not at the group level). This may, at least in part, have led to selective outcome reporting. Consequently, we judged the overall quality of the evidence to be low.

Effects of the strategies

The effects of the strategies are summarized in Table 3.

Clinical productivity

All six studies assessing clinical productivity reported an increase in productivity in terms of clinical revenue, the work component of relative-value units, patient satisfaction and other departmentally used standards.3,6–9,11 Three studies reported increased productivity at the group level;3,7,8 one of these studies reported a simultaneous increase in productivity at the individual level,8 one reported a decrease at the individual level,3 and one did not report on individual productivity.7 Two studies reported decreased group productivity and increased individual productivity,6,11 with one describing an increasing workload undertaken by a stable number of full-time equivalent faculty.11 One study reported increased individual productivity but did not report on group productivity.9

Research productivity

Five of the six studies assessing this outcome reported increased research productivity in terms of applications for funding,3 acquisition of funding,3,9,10,13 number of publications13 or some other measure.6 The sixth study reported that the rate of publication did not change after implementation of the strategy.11 Two studies evaluated research productivity based on a point-based system using either relative-value units6 or a scheme developed by a departmental committee.11

Teaching productivity

Of the five studies that assessed this outcome, two reported that the “educational output” was stable11 or that the number of student and resident sessions did not change.8 Two studies reported no change in student or resident evaluations,8,9 and one reported improvement in such evaluations.10 One study reported a 4% drop in a mean composite score for teaching.6 However, that same study suggested that faculty were more willing to participate in educational activities.

Compensation

One of the five studies that assessed this outcome reported an increase in compensation at the group level by 8%,8 another reported an increase at the individual level by 40%,11 and a third study reported a “slight” increase at both levels.7 Two studies reported a change in compensation distribution in favour of junior faculty10,11 (defined in one study as assistant professors10).

Other outcomes

One study reported improvement or no change in patient satisfaction.7 That study showed varying levels of satisfaction among faculty; satisfaction was associated with “understanding of the plan” and inversely associated with years of service.

Only one study provided some evidence about shifts in area of productivity: faculty who were not productive in their research work shifted to patient care.3 None of the eligible studies assessed effects on administrative productivity or promotion processes.

Interpretation

We found that strategies introduced to assess faculty productivity as part of a compensation scheme in academic medical centres appeared to improve productivity in research activities and possibly improved clinical productivity but had no effect in the area of teaching. Compensation increased at both the group and individual levels, particularly among junior faculty. None of the studies assessed effects on administrative productivity or promotion processes.

Despite the low level of quality of the evidence, the data suggest that the assessment of faculty productivity, when coupled with an appropriate compensation or incentive scheme, can lead to positive systemic cultural change and help to achieve a department’s mission.1 For example, one of the included studies reported that the strategy resulted in non-research faculty volunteering for more teaching and administrative responsibilities, which freed up research faculty to engage in scholarly pursuits.12

Assessment of productivity can have some negative unintended consequences. Faculty might assume that an item not being evaluated is less important.3 For example, not considering teaching productivity, or weighing it much lower than clinical productivity, may affect faculty who teach and hurt the mission of the department. The productivity assessment strategy and the compensation scheme should lead to proper relative compensation for the different areas. That approach would ensure their alignment with the mission of department and the goals of its chair.

Another unintended consequence may be driven by gaming the system, intentionally or not, to score high on the productivity assessment with disregard to quality (e.g., aiming to get good evaluations rather than provide good teaching). Clinical care and teaching are two areas vulnerable to such effects. Appropriate and validated measurement tools as well as an adequate culture are needed to help avoid these situations.

There are a number of challenges to assessing productivity (Box 1). The primary challenge is how to measure productivity. Indeed, clinical activities might not be equally intense (e.g., on-call time intensity might vary depending on the site), which makes availability a suboptimal measure.3 Similarly, reimbursement for clinical work may not be ideal because it can vary depending on the site (county v. private clinic). Also, it may be difficult to determine the equivalent values across areas of productivity (e.g., clinical v. research). The most common approach to achieving a fair assessment has been the use of relative-value units. Different approaches have been used to develop these units. Hilton and colleagues developed a base unit for each area of productivity (clinical, teaching, research and administration) and adjusted them so that the total points for the presumed productivity of a “top producer” in each of the areas would be equal.16 Cramer and colleagues proceeded by agreeing on a relative-value unit for clinical productivity (using a specific billing level) and then determined equal points for equal effort in the other areas by committee consensus.6 Others developed scales that focused on one area only, such as teaching.17

Box 1: Challenges to assessing productivity of faculty.

The best way to measure productivity is not clear

Faculty may have little or no control over their productivity because of factors such as clinic population, scheduling, staffing and nonclinical demands.6 Similarly, productivity in research activities may be affected by factors such as the availability of biostatistical and methodologic support.

Implementation of a productivity assessment strategy may be hampered by the lack of timely and accurate billing data; dedicated staff may be required for the collection, verification and analysis of data.3,6,8

In many cases productivity data are self-reported and may require regular auditing.6

Concerns about the fairness, accuracy and timeliness of the process may negatively affect faculty buy-in and need to be adequately addressed.6

The assessment of clinical productivity typically does not account for teamwork and may affect it negatively. As a result, some have advocated the assessment of productivity at the group level.7

Although strategies for assessing productivity can be used solely as evaluation tools (for both departments and faculty), they are most often used along with productivity-based compensation programs to reward and stimulate productivity. Typically, these programs place a percentage of income at risk (e.g., 20%)11 and reward productivity beyond the expected minimum (marginal productivity).18 Some have argued that an incentive system focused on specific goals is more effective than a productivity-based program.1

A number of factors can affect the success of productivity-based programs. Rewards should not be based on thresholds that reward only exceptionally productive faculty.6 At the same time, they need to be incremental to avoid hitting a “magic number” above which faculty loose incentive for being more productive.6 Ideally, reward schemes need to be aligned with and adjusted regularly to local and national trends for compensation,8 as well as to increases or decreases in departmental finances. The rewards should be valuable enough (in monetary value) to have an impact.18

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is our adherence to the high standards of conducting and reporting systematic reviews.19 In particular, we used a thorough process for selecting studies, abstracting data and verifying the results directly with the authors of the included studies.

The main limitation of our systematic review is inherent in the available evidence and the low methodologic quality of the studies and their poor reporting. Another limitation is the generalizability of the results. First, all of the results were from academic centres in the United States. Given different academic environments in other countries, the findings may not apply elsewhere. Second, the studies focused on primary care and anesthesiology, and therefore the results may not be applicable to other specialties.

Conclusion

Strategies introduced to assess faculty productivity as part of a compensation scheme appeared to improve research productivity and possibly improved clinical productivity but had no effect in the area of teaching. Compensation increased at both group and individual levels, particularly among junior faculty.

Departments planning on introducing a strategy to assess productivity need to carefully consider the associated challenges, the uncertain benefits and the potential unintended effects. Appendix 2 provides further examples of such strategies. For academic medical centres to make informed decisions about the future use of productivity assessment strategies, they will need higher quality evidence about the benefits and harms of those strategies. Although cluster randomized trials are conceptually feasible, they may not be practical. Large controlled observational or before–after studies with careful handling of confounding (through matching and adjustment) could provide higher quality evidence. Also, a central repository of strategies, processes and measurement tools would be ideal to assist academic leaders in designing their own programs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Neera Bhatnagar and Mr. Edward Leisner for their assistance in designing the search strategy. They also thank Ms. Ann Grifasi and Mr. Eric Zinnerstrom for their administrative assistance.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Elie Akl, Aymone Gurtner, Stefano Mattarocci, Manlio Mattioni, Joerg Meerpohl, Marco Paggi, Giulia Piaggio, Dany Raad and Rizwan Tahir acquired the data. Elie Akl and Holger Schünemann analyzed and interpreted the data. Elie Akl, Paola Muti and Holger Schünemann provided administrative, technical or material support and supervised the study. Paola Muti and Holger Schünemann obtained funding. Elie Akl drafted the manuscript. All of the authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Funding: This study was supported by internal funds from the Regina Elena National Cancer Institute in Rome. The institute had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review and approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Abouleish AE. Productivity-based compensations versus incentive plans. Anesth Analg 2008;107:1765–719020114 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashar B, Levine R, Magaziner J, et al. An association between paying physician-teachers for their teaching efforts and an improved educational experience for learners. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:1393–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garson A, Jr, Strifert KE, Beck JR, et al. The metrics process: Baylor’s development of a “report card” for faculty and departments. Acad Med 1999;74:861–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santilli SM. Current issues facing academic surgery departments: stakeholders’ views. Acad Med 2008;83:66–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction — GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:383–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer JS, Ramalingam S, Rosenthal TC, et al. Implementing a comprehensive relative-value–based incentive plan in an academic family medicine department. Acad Med 2000;75: 1159–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sussman AJ, Fairchild DG, Coblyn J, et al. Primary care compensation at an academic medical center: a model for the mixed-payer environment. Acad Med 2001;76:693–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreae MC, Freed GL. Using a productivity-based physician compensation program at an academic health center: a case study. Acad Med 2002;77:894–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarquinio GT, Dittus RS, Byrne DW, et al. Effects of performance-based compensation and faculty track on the clinical activity, research portfolio, and teaching mission of a large academic department of medicine. Acad Med 2003;78:690–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller RD, Cohen NH. The impact of productivity-based incentives on faculty salary-based compensation. Anesth Analg 2005; 101:195–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reich DL, Galati M, Krol M, et al. A mission-based productivity compensation model for an academic anesthesiology department. Anesth Analg 2008;107:1981–819020149 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schweitzer L, Eells TD. Post-tenure review at the University of Louisville School of Medicine: a faculty development and revitalization tool. Acad Med 2007;82:713–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schweitzer L, Sessler DI, Martin NC. The challenge for excellence at the University of Louisville: implementation and outcomes of research resource investments between 1996 and 2006. Acad Med 2008;83:560–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medical Group Management Association Physician compensation and production survey report: 1998 report based on 1997 data. Englewood (CO): The Association; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feiner JR, Miller RD, Hickey RF. Productivity versus availability as a measure of faculty clinical responsibility. Anesth Analg 2001;93:313–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilton C, Fisher W, Lopez A, et al. A relative-value–based system for calculating faculty productivity in teaching, research, administration, and patient care. Acad Med 1997;72:787–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bardes CL, Hayes JG. Are the teachers teaching? Measuring the educational activities of clinical faculty. Acad Med 1995;70:111–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lubarsky DA. Incentivize everything, incentivize nothing [editorial]. Anesth Analg 2005;100:490–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.