Abstract

Large conductance Ca21-activated K1 (BKCa) channels are abundantly expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells. Activation of BKCa channels leads to hyperpolarization of cell membrane, which in turn counteracts vasoconstriction. Therefore, BKCa channels have an important role in regulation of vascular tone and blood pressure. The activity of BKCa channels is subject to modulation by various factors. Furthermore, the function of BKCa channels are altered in both physiological and pathophysiological conditions, such as pregnancy, hypertension and diabetes, which has dramatic impacts on vascular tone and hemodynamics. Consequently, compounds and genetic manipulation that alter activity and expression of the channel might be of therapeutic interest.

Keywords: BKCa channel, vascular tone, regulation, cardiovascular dysfunctions, therapeutics

Ca21-activated K1 (KCa) channels have an important role in cell excitability by sensing and reacting to changes in intracellular Ca21 concentrations. Based on their conductance the KCa family is divided into small-conductance (SKCa, ~4–14 pS), intermediate-conductance (IKCa, ~32–39 pS) and large-conductance (BKCa, ~200–300 pS) channels. Whereas BKCa channels are activated by membrane depolarization and/or Ca21 binding to the channel, SKCa and IKCa channels are voltage-insensitive and stimulated by Ca21 binding to calmodulin constitutively bound to the channels [1]. SKCa, IKCa and BKCa channels are all present in vasculature with preferential expression of BKCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and SKCa and IKCa channels in endothelial cells [2–4]. All these channels contribute significantly but differently to the regulation of vascular tone. Activation of BKCa channels in VSMCs enables K1 efflux, resulting in membrane hyperpolarization. By contrast, activation of SKCa and IKCa channels indirectly triggers hyperpolarization of VSMCs through endothelium-dependent mechanisms involving generation of nitric oxide (NO) in the endothelium and endothelium-mediated hyperpolarization of VSMCs [2,5]. The hyperpolarization of VSMCs conferred by the endothelium possibly involves electrical coupling between the endothelium and VSMCs through myoendothelial gap junctions and/or activation of inwardly rectifying K1 (Kir) channels as the result of accumulation of K1 in the intercellular space owing to the activity of SKCa and IKCa channels in endothelial cells. As a result of VSMC hyperpolarization, the voltage-gated Ca21 channel (Cav) is closed, leading to a reduction of intracellular Ca21 concentrations and subsequent vasodilation. In this article we focus on the function and regulation of BKCa channels in VSMCs, and the readers are referred to excellent reviews on the roles of SKCa and IKCa channels in the regulation of vascular function [2,3,5].

Overview on BKCa

BKCa channels are implicated in a variety of physiological functions ranging from regulating tone of vascular beds to modulating release of hormones and neurotransmitters [6]. BKCa channels are a tetramer formed by pore-forming α-subunits along with accessory β-subunits, activated by membrane depolarization and/or an increase in intracellular Ca21 [7]. The α-subunit, ubiquitously expressed in mammalian tissues, is encoded by a single gene (KCNMA1) with various spliced isoforms. Four distinct genes have been identified for β-subunits (KCNMB1–4), and expression of β-subunits is tissue-specific [8]. The α-subunit contains a transmembrane domain sensing membrane potential and conducting ion and a cytoplasmic domain sensing Ca21. The β-subunits consist of two transmembrane domains (TM1 and TM2) with a large extracellular loop. The α-subunit transmembrane domain is comprised of seven membrane-spanning segments (S0–S6), which contribute to voltage-sensing (S1–S4) and pore-forming (S5–S6) [9]. The cytoplasmic domain of α-subunit comprises two regulator of K1 conductance (RCK) domains, and it is believed that Ca21-sensing is achieved through two high affinity Ca21 binding sites located in both RCK1 and RCK2 [10].

Disulfide cross-linking studies revealed the locations of β-subunit in BKCa channels: TM1 next to S1 and to S2 and TM2 close to S0 [11]. Theoretically, α– and β-subunits of BKCa channels could co-assemble in a 1:1 stoichiometry. However, studies carried out in native tissues and heterologous expressing systems revealed that the population of BKCa channels is not homogenous [12,13]. Fractions of the BKCa channel can exist with less than four β-subunits [14]. Lines of evidence suggest that stoichiometry of α– to β-subunits of the BKCa channel is dynamic. Expression of β1-subunit is selectively up- or downregulated in VSMCs without affecting α-subunit expression under various physiological and pathophysiological conditions and hormone stimulation, leading to enhanced or depressed BKCa channel activity [15–17]. BKCa channels undergo extensive alternative splicing, and splice variants displays different biophysical properties, such as voltage sensitivity, Ca21 sensitivity and kinetics [18,19]. Channel protein trafficking [19,20], expression [21] and phosphorylation [19,22] also vary among splice variants. The association of β-subunits to α-subunit further expands the diversity of BKCa channel properties. Sensitivity of the channel to voltage and Ca21 was increased by the β1, β2 and β4 subunits but not by β3 subunit [23–25]. Pharmacological profiles of BKCa channels are also altered by β-subunits. BKCa channels formed by α and β4 subunits are resistant to iberiotoxin [25].

BKCa channels in VSMCs and their physiological roles

Expression and physiological roles of BKCa channels in VSMCs

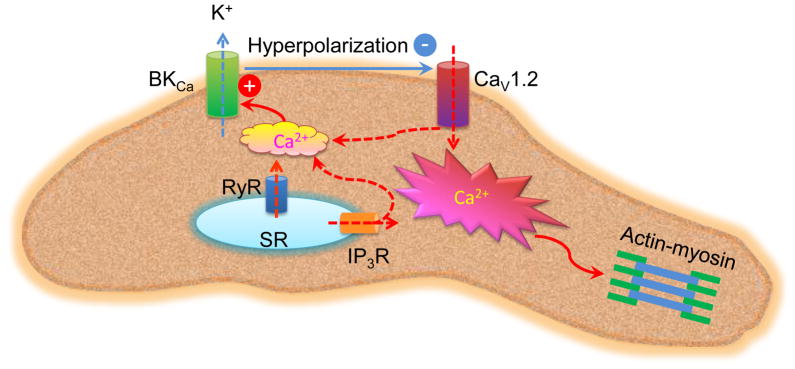

BKCa channels are expressed in virtually all VSMCs, and both α– and β-subunits of the BKCa channel have been cloned [26–28]. The predominant β-subunit in VSMCs is β1-subunit [29,30]. Low levels of β2 and β4 transcripts are detected in VSMCs and their expression at protein level is undetectable or negligible [31,32]. In VSMCs, BKCa channels are primarily activated by an elevation of intracellular Ca21 concentration ([Ca21]i) due to spontaneous [33] or agonist-stimulated [34] Ca21 release from intracellular stores. In addition, Ca21 influx through L-type voltage-gated Ca21 channel (CaV1.2) also stimulates BKCa channel activity (Figure 1) [35]. Activities of BKCa channels contribute substantially to regulation of vascular function owing to its large single channel conductance (200–300 pS) and high protein expression [36,37]. The opening of the BKCa channel enables K1 efflux, leading membrane hyperpolarization. This membrane potential change closes CaV1.2, which in turn reduces [Ca21]i and induces vasorelaxation. By contrast, closing of the BKCa channel causes membrane depolarization which opens CaV1.2, resulting in an increase in [Ca21]i and consequent vasoconstriction. In general, BKCa channels in VSMCs participates in setting resting membrane potential, regulating vascular tone and functioning as a compensatory mechanism to buffer vasoconstriction.

Figure 1. Sources of Ca21 in activation of BKCa channels in VSMCs.

The major cause for activation of BKCa channels in VSMCs is an increase in intracellular Ca21 concentrations in the vicinity of BKCa channel (Ca21 microdomain). Such a localized increase in Ca21 could be achieved by spontaneous or agonist-stimulated Ca21 release from intracellular stores through RyR or IP3R on SR and Ca21 influx through L-type CaV1.2. Activation of BKCa channels enables K1 efflux due to the K1 electrochemical gradient, resulting in hyperpolarization of the myocyte membrane and subsequent closure of CaV1.2.

Abbreviations: BKCA: Large-conductance Ca21-activated K1; CaV1.2: voltage-gated Ca21 channel; IP3R: inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor; RyR: ryanodine receptor; SR: sarcoplasmic reticulum; VSMCs: vascular smooth muscle cells.

Vascular tone is the major determinant of resistance to blood flow through the circulation, and has a crucial role in both regulating blood pressure and distributing blood flow within the tissues and organs. In resistant arteries blockade of the BKCa channel with inhibitors of BKCa channel depolarized the membrane of VSMCs, leading to vasoconstriction [38]. In addition, the blockade of the BKCa channel enhanced vasoconstriction induced by vasoconstrictors [39]. By contrast, activation of BKCa channels with channel opener NS1619 caused membrane hyperpolarization, resulting in vasodilation and/or reduced vasoconstriction [40,41]. The importance of BKCa channels in VSMCs is further demonstrated by targeted deletion of genes of BKCa channel. VSMCs from the BKCa α-subunit null mice exhibited loss of spontaneous transient outward currents (STOCs) and more depolarized membrane potential, which accounted for the increased systemic blood pressure [42]. BKCa channels in VSMCs deprived of the β1 subunit also displayed decreased channel activity which was associated with reduced Ca21 sensitivity and impaired coupling between Ca21 sparks and BKCa channel activity, leading to elevated systemic blood pressure in the transgenic mice [29,43]. An aorta from β1 subunit knockout mice exhibited a heightened contractile response to norepinephrine [43]. These observations further support a negative feedback mechanism of BKCa channels in limiting excessive vasoconstriction. However, the significance of β1 subunit in regulating blood pressure is challenged by a recent observation that β1-subunit knockout mice are not hypertensive [44].

BKCa channels as the target of vasoconstrictors and vasodilators

BKCa channels also have an important role in both vasodilation and vasoconstriction induced by vasoactive substances. In general, vasodilators activate BKCa channels, whereas vasoconstrictors inhibit the channels. BKCa channels in VSMCs are the major mediator of vasodilators. Activity of the channels was enhanced by isoproterenol [45,46], bradykinin [47], calcitonin gene related peptide [48], and prostaglandin E2 [49]. Accordingly, suppressing BKCa channel activity with tetraethylammonium (TEA) impaired vasorelaxation in response to isoproterenol [45]. By contrast, vasoconstriction induced by 5-hydroxytrypteamine [50], phenylephrine [50], angiotensin II [50–52], endothelin-1 [51], thromboxane A2 [53], and 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) [54] was accompanied by an inhibition of BKCa channel activity.

Regulation of BKCa channel activity in VSMCs

Phosphorylation

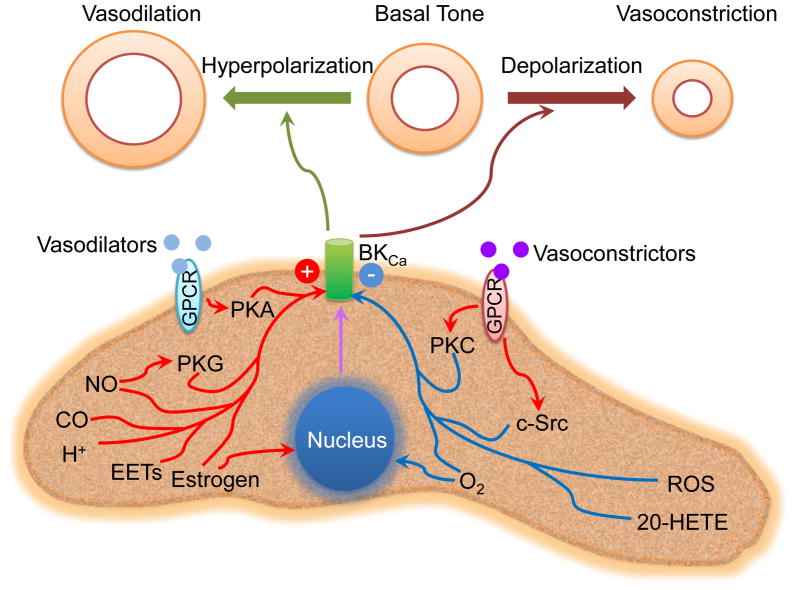

A variety of phosphorylation sites have been identified in cytoplasmic domain of BKCa channel α-subunit [55]. BKCa channels in VSMCs is regulated by various protein kinases, including cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA), cyclic GMP dependent protein kinase G (PKG), diacylglycerol and/or Ca21-dependent protein kinase C (PKC), and tyrosine kinase c-Src. Depending on the particular protein kinase involved, phosphorylation of BKCa channels could lead to altered Ca21- and voltage-sensitivity [55], which in turn increases or decreases channel activity. In general, BKCa channel activity in VSMCs was stimulated by PKA [48,56] and PKG [57,58] but inhibited by PKC [59,60] and c-Src [50]. However, excitatory effects of PKC and c-Src on BKCa channel were also observed. Activation of PKC increased BKCa channel activity in rat pulmonary arterial myocytes [61]. In addition, c-Src was found to enhance BKCa channel activity in a heterologous expression system [62]. Interestingly, complex cross-talks exist among protein kinases in modulating BKCa channel activity. In coronary and pulmonary arterial myocytes, cAMP was found to cross-activate BKCa channel through PKG [46,63]. In addition, PKG mediated PKC-stimulated BKCa channel in rat pulmonary arterial myocytes [61]. Furthermore, cAMP-induced activation of BKCa channel in coronary and pulmonary arterial myocytes was inhibited by PKC [59,64]. Whether these cross-talks occur in vivo has yet to be determined. A variety of vasoactive substances exerted their actions involving phosphorylation of BKCa channel (Figure 2). For example, vasoconstriction induced by 20-HETE, 5-hydroxytryptamine, angiotensin II, and phenylephrine involved inhibition of the BKCa channel by PKC and c-Src [50,52,54]. By contrast, vasodilation induced by isoproterenol and NO required activation of the BKCa channel by PKA and PKG, respectively [46,57].

Figure 2. Regulation of BKCa channels in VSMCs.

BKCa channels in VSMCs are a regulatory target of vasodilators and vasoconstrictors throughGPCRs. These vasoactive agents alter BKCa channel activity through phosphorylation of the channel by activation of protein kinases. Generally, BKCa channel activity is enhanced by activation of PKA or PKG, but depressed by activation of PKC and c-Src. In addition, BKCa activity is modulated by a variety of factors involving both non-genomic and genomic mechanisms. An elevation and/or generation of NO, CO, H1, EETs and estrogen stimulates BKCa channel activity, whereas an increase production of 20-HETE and ROS and a decrease in pO2 inhibit BKCa channel function. However, exceptions do exist. As a result, activation of BKCa channels hyperpolarizes the myocyte membrane leading to vasodilation, whereas inhibition of BKCa channel causes depolarization of the membrane resulting in vasoconstriction.

Abbreviations: BKCA: Large-conductance Ca21-activated K1; CO: carbon monoxide; EETS: epoxyeicosatrienoic acids; GPCR: G-protein coupled receptors; 20-HETE: 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; NO: nitric oxide; pO2: oxygen partial pressure; PKA: protein kinase A; PKC: protein kinase C; ROS: reactive oxygen species; VSMCs: vascular smooth muscle cells.

Steroid hormones

Accumulating evidence has also implicated steroid hormones as important physiological and pathophysiological regulators of cardiovascular functions [65]. These hormones have been shown to alter vascular function in part by regulating BKCa channel activity in VSMCs through both genomic and non-genomic mechanisms.

Acute administration of 17-β-estradiol resulted in vasorelaxation and/or vasodilation which could be inhibited by blockade of BKCa channel [66,67]. Electrophysiological techniques[RE1] revealed stimulation of BKCa channel activity by estrogen and xenoestrogens in various vascular beds, such as coronary artery [68–70], cerebral artery [71], uterine artery [72]. Enhanced BKCa channel activity by acute estrogen exposure did not involve changes in channel expression [73]. A variety of non-genomic mechanisms have been implicated in acute vascular responses exerted by estrogen. At pharmacological (micromolar) concentrations, estrogen exerted its stimulatory action through interacting with β1 subunit [74]. Estrogen at physiological concentrations could stimulate generation of NO in VSMCs; and NO in turn enhanced BKCa channel activity through the cGMP-PKG signaling pathway [68,72]. Estrogen could also enhance BKCa channel activity in VSMCs in part through increasing NO release from endothelial cells [66]. Furthermore, a recent study revealed that activation of the G-protein coupled estrogen receptor stimulated BKCa channel activity in coronary arterial myocytes independent of NO-cGMP-PKG pathway, leading to vasorelaxation [70]. Acute administration of estrogen increased coronary blood flow [75]. Major portion of vasodilation of coronary artery and subsequent increased blood flow induced by estrogen were conferred by activation of BKCa channel. Thus, estrogen-induced vasodilation likely has a role in reducing both myocardial infarct size and ventricular arrhythmias.

Chronic exposure to estrogen also alters BKCa channel function in VSMCs. Estrogen responsive sequences have been identified in the promoters of mouse α-subunit gene, and estrogen strongly stimulated mSlo promoter activity through activation of estrogen receptor α (ERα) [76]. However, in contrast to genomic upregulation of mSlo transcription, stimulation of hSlo gene expression by estrogen involved a nongenomic PI3K signaling pathway and other mechanisms [77]. In ovariectomized nonpregnant sheep, prolonged exposure to 17β-estradiol increased expression of β1, but not α-subunit in uterine artery [73]. Similarly, chronic treatment of nonpregnant ovine uterine arteries with physiologically relevant concentrations of 17β-estradiol in an ex vivo tissue culture system augmented BKCa channel activity, which was accompanied by increased protein expression of β1 subunit [17]. By contrast, similar treatment of ovariectomized guinea pig increased expression of α but not β1, subunit in aorta [78], suggesting species- and/or tissue-dependent upregulation of BKCa channels by estrogen. However, a 48-hour exposure of cultured human coronary arterial myocytes to a pharmacological concentration of 17β-estradiol led to downregulation of BKCa channels [79].

Acute progesterone exposure also induced vasorelaxation and/or vasodilation of coronary artery through endothelium-independent, nongenomic mechanism [80]. Activity of BKCa channel in coronary artery was significantly enhanced by progesterone [81]. Testosterone-induced vasorelaxation was sensitive to blockade by BKCa channel blockers [82,83]. BKCa channel activity was stimulated by testosterone in coronary artery [82]. A recent study revealed that hydrogen sulfide (H2S) was involved in the vasodilatory effect of testosterone [84]. It is likely that activation of BKCa channels by this gasotransmitter leads to vasodilation induced by testosterone.

Chronic treatment of rat aorta with glucocorticoids, such as corticosterone and 11-dehydrocorticosterone resulted in enhanced contractile response to phenylephrine and angiotensin II [85]. A later study demonstrated that expression of α-subunit in cultured rat aortic myocytes was decreased after chronic exposure to glucocorticoids [86], which in part accounted for the enhanced contractile response induced by glucocorticoids. The enhanced vasoactivity by glucocorticoids could attribute to occurrence of hypertension during clinical application of glucocorticoids [87]. In addition, a 24-hour treatment of cultured VSMCs with aldosterone decreased expression of BKCa channels [88].

Redox and ROS

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), generated in vascular cells including endothelial and smooth muscle cells, exert both physiological and pathophysiological impacts on vascular function by altering intracellular reduction and/or oxidation (redox) status [89]. One of the ROS targets in blood vessels is BKCa channels in VSMCs. The activity of BKCa channels in VSMCs was stimulated by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) [90,91], which in turn could hyperpolarize cell membrane leading to vasodilation. Indeed, H2O2 caused vasorelaxation and/or vasodilation which was attenuated by BKCa channel blockers [90,92[RE2]]. H2O2 could directly bind to the channel to modify BKCa channel activity [90]. In addition, activation of BKCa channels by H2O2 also involved PLA2-arachidonic acid signaling pathway and metabolites of lipoxygenase [91]. BKCa channel activity in pulmonary arterial myocytes was stimulated by oxidizing agents, such as 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) and oxidized glutathione (GSSG), where it was inhibited by reducing agents, such as dithiothreitol (DTT), reduced glutathione (GSH;) and NADH [93]. By contrast, the opposite was observed for heterologously expressed BKCa channels [94,95]. Peroxynitrite (OONO−), an oxidant formed by the reaction of NO and superoxide, contracted cerebral artery [96]. Furthermore, OONO− inhibited BKCa channels in cerebral and coronary arterial myocytes [97,98]. The impaired BKCa channel activity by OONO− could depolarize the cell membrane, resulting in vasoconstriction.

Excessive generation of ROS has been observed in a variety of physiological and pathophysiological conditions, such as aging, diabetes, hypoxia, and hypertension [89]. Therefore, alternation of BKCa channel function by ROS might contribute to the development of cardiovascular dysfunctions associated with those conditions. Indeed, oxidation of cysteine residues was found to be a contributing factor in altered BKCa function of VSMCs in diabetes [95].

Gases (NO and CO)

In circulatory system, NO is primarily synthesized by nitric oxide synthase (NOS) in the endothelium, which diffuses to VSMCs once released [99]. The interaction of NO with VSMCs causes hyperpolarization and vasorelaxation [100]. BKCa channels have been implicated in the action of NO in VSMCs. Vasorelaxation and/or vasodilation induced by NO was attenuated by blockade of BKCa channel [66,101]. NO stimulated the BKCa channel activity in various vascular beds [101–103]. Two types of modulation of BKCa channel by NO have been reported: (i) PKG-dependent [58,66,101] and (ii) direct interaction of NO with the channel protein [102,103]. The direct modulation possibly involved nitrosylation of sulfhydryl groups in BKCa channels [102,104]. Furthermore, knockdown of β-subunit with antisense abolished the stimulatory effect of NO [104], implicating β-subunit as a mediator of NO.

Carbon monoxide (CO) is generated in both endothelial cells and VSMCs through metabolism of heme by heme oxygenase (HO) [105]. As similar to NO, CO also functions as a vasodilator, and inhibition of BKCa channels ablated CO’s vasorelaxant effect [106,107]. Furthermore, BKCa channel activity in VSMCs was stimulated by CO [108,109]. Ca21 sensitivity was increased [109], due to an enhanced coupling Ca21 sparks to BKCa channels [110]. The modulation of BKCa channels by CO is independent of β-subunit [104] and does not involve PKG [108]. Several potential sites in α-subunit for CO interaction have been identified: (i) extracellular histidine residues [111], (ii) H365, D367 and H394 in RCK1 [112]; and (iii) H911 in RCK2 [113]. Considering the role of RCK1 and RCK2 in regulating Ca21 affinity, it is not surprising that the contact of CO with residues within these two domains increase Ca21 sensitivity. BKCa channel activity appears to be under a constant control of endogenously generated CO. Inhibition of HO depressed BKCa channel activity in renal artery, which could be reversed by exogenous CO [114].

Arachidonic acid and its metabolites

Arachidonic acid and its metabolites, such as 20-HETE[RE3] and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) are potent vasoactive substances and have important roles in regulation of vascular function. Whereas 20-HETE is a vasoconstrictor, arachidonic acids and EETs are vasodilators [115]. In isolated VSMCs, arachidonic acid activated BKCa channels [116,117]. Moreover, arachidonic acid-induced vasorelaxation was attenuated by blockade of BKCa channels [118], suggesting involvement of BKCa channels in vasoactive action of arachidonic acid. BKCa channel activity was enhanced by EETs [119]. EETs increased sensitivity of BKCa channels to Ca21 and voltage. The enhanced BKCa channel activity could account for the vasodilatory response induced by EETs since the vasodilation was reduced by BKCa channel blockers [120].

By contrast, BKCa channel activity in VSMCs was inhibited by 20-HETE [54,121]. The inhibition of BKCa channels by 20-HETE was mediated by PKC [54]. As a result, vasoconstriction induced by 20-HETE was absent after blockade of BKCa channels [121]. In renal artery, both activation of BKCa channels and vasodilation induced by NO was largely due to depressed formation of 20-HETE by NO [122]. Decreased generation of 20-HETE during exposure to acute hypoxia and subsequently reduced inhibition of BKCa channel activity also accounted for hypoxia-induced vasodilation of pulmonary artery [123].

pH

The pH in VSMCs fluctuates, and a change in intracellular proton [H1]i concentration could have an impact on vascular tone [124]. In general, acidification leads to vasorelaxation, whereas alkalization results in enhanced vasoconstriction [124]. Interestingly, BKCa channel activity in cultured coronary [125] and rabbit basilar [126] arterial myocytes was stimulated by increasing H1 concentration. Those observations suggest that activation of BKCa channels by H1 could contribute to acidosis-induced vasorelaxation. A mutagenesis study revealed that H1 exerted its action by interacting with His365 and His394 in addition to Asp367, a residue participating high-affinity Ca21 sensing, in the RCK1 domain [127]. However, inhibitory effect of acidosis on BKCa channels was reported in human internal mammary [128] and rat tail [129] arterial myocytes. The physiological relevance of acidosis-induced BKCa channel inhibition is not clear.

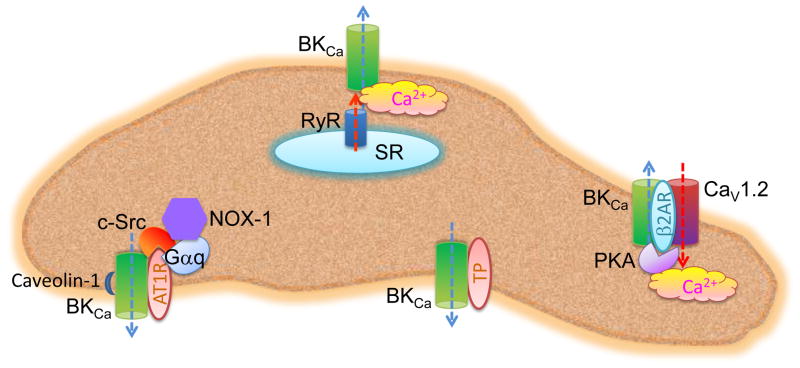

Macromolecular signaling complex: a new form of BKCa channel regulation

Formation of macromolecular complexes by signaling molecules has a crucial role in cellular signaling, which enables rapid, specific and local regulation [130]. BKCa channels in VSMCs have been reported to form macromolecular complexes with various signaling components, including receptors, ion channels, enzymes, anchoring proteins and heme (Figure 3). The association of these components to BKCa channels influences ion channel activation, phosphorylation and location.

Figure 3. Regulation of BKCa channels by forming macromolecular complexes in VSMCs.

BKCa channels in VSMCs could form macromolecular complexes with other signaling components including GPCRs, ion channels, enzyems, G proteins, and anchor proteins. The association of Ca21-permeable channels (CaV1.2 and RyR) and BKCa channel enables creation of a high concentration of Ca21 in the vicinity of BKCa channels (Ca21 microdomain). The formation of GPCR-BKCa channel complex permits direct modulation of the channel by thromboxane A2 receptor (TP) or indirect modulation by β2AR-associated PKA or AT1R-associated c-Src. The inclusion of nonpnagocytic NAD(P)H oxidases (NOX-1) in the AT1R-BKCa complex provide addition modulation of BKCa channels by ROS, which might have a role in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular dysfunction in patients with diabetes.

Abbreviations: AT1R: angiotensin II type 1 receptor β2AR: β2-adrenergic receptor; GPCR: G-protein coupled receptors; PKA: protein kinase A; ROS: reactive oxygen species; VSMCs: vascular smooth muscle cells.

BKCa channels were found to associate with a variety of ion channels that mediate Ca21 influx across plasma membrane and Ca21 release from intracellular Ca21 stores. BKCa channels and CaV1.2 formed a complex in rat aorta and in cultured human VSMCs; and β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) functioned as a scaffold to enable the physical association of these two channels [131]. The association of BKCa channels with transient receptor potential canonical 1 (TRPC1), a Ca21-permeable cation channel mediating store-operated Ca21 entry was observed in cultured rat aortic myocytes [132]. BKCa channels were also found to form a complex with ryanodine receptor (RyR) in myocytes of vas deferens and bladder [133] and trachea [134]. Activation of BKCa channels requires a [Ca21]i concentration of ≥10 μM [135]. Opening of Ca21-permeable channels in the complex leads to Ca21 influx across the plasma membrane or release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca21 store, which could create high local concentrations of Ca21 (Ca21 microdomains) [136]. Physically associating BKCa channels with those Ca21-permeable channels ensures that BKCa channels are in close proximity to the Ca21 microdomains, enabling rapid and specific activation. Consistently, both Ca21 influx mediated by CaV1.2 [35,137] and TRPC1 [132], and Ca21 release mediated by RyR [137] activated BKCa channels in smooth muscle cells. Although type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphated receptor (IP3R) and BKCa channels were associated in cerebral arterial myocytes, activation of IP3R-stimulated BKCa channel activity was independent of Ca21 release from sarcoplasmic reticulum store [138].

Some G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) also associate with BKCa channels to form signaling complexes. BKCa channels and thromboxane A2 receptor (TP) were found to form a complex in myocytes of human coronary artery and rat aorta [139]. Activation of TP led to a G protein-independent trans-inhibition of BKCa channels, involving interaction between first intracellular loop and C terminus TP and voltage-sensing conduction cassette of BKCa channels. A macromolecular complex containing BKCa channels, CaV1.2, β2AR, A-kinase-anchoring protein (AKAP79/150) was described in rat aorta and bladder in addition to in cultured human VSMCs [131]. The third intracellular loop of β2AR was involved in BKCa channel-β2AR interaction. To achieve full functional regulation of BKCa channels, possibly involving phosphorylation mediated by PKA, co-localization of β2AR, BKCa channel, and AKAP79 is required. A recent study demonstrated existence of a macromolecular complex containing BKCa channels, angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R), Gαq/11, nonphagocytic NAD(P)H oxidases (NOX-1), and c-Src kinases (c-Src) in the caveolae of rat aortic myocytes [52]. Angiotensin II stimulated activity of NOX-1 leading to generation of ROS, which subsequently inhibited BKCa channel activity. Furthermore, physical association between BKCa channels and AT1R was enhanced in the vasculature of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, resulting in heightened AT1R-mediated oxidative modification and impaired BKCa channel function.

Formation of kinase-ion channel complex permits fine control of phosphorylation state of the channel. Association of BKCa channels and c-Src has been demonstrated in myocytes of human coronary artery [50] and rat aorta [52]. Such a c-Src-BKCa channel complex arrangement may facilitate tyrosine phosphorylation of BKCa channels and subsequent channel inhibition stimulated by angiotensin II, 5-hydroxytriptamine, and phenylephrine. Direct evidence for association of other kinases to BKCa channels in VSMCs is lacking. However, the observations of participation of AKAP79 in formation of β2AR-BKCa channel complex and requirement of AKAP79 in activation of β2AR-stimuated BKCa channel activity [131] suggest that PKA is likely to be a component of the macromolecular complex. In mouse cardiac myocytes, PKA was a signaling component of a macromolecular complex which also included caveolin-3, CaV1.2, β2-AR, G-protein αs, adenylyl cyclase, and protein phosphatase 2a [140].

BKCa channels contain two caveolin-binding motifs in its cytoplasmic domain. Association between caveolin-1 and BKCa channels was observed in rat aortic myocytes [52,141]. By forming such a complex, caveolin-1 has an important role in both targeting BKCa channels to caveolin-rich caveolae and reducing cell surface expression of the channel [141]. BKCa channel-mediated vasodilation was increased in gracilis muscle arterioles from caveolin-1 knockout mice [142]. By contrast, expression of caveolin-1 was dramatically increased in aorta from streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, which was accompanied by impaired BKCa channel function [52]. It is not surprising that genetic ablation of caveolin-1 gene resulted in increased current density of BKCa channel in cerebral arterial myocytes [143] and protected vascular BKCa channel function in diabetes [52].

Heme could inhibit BKCa channel activity in VSMCs activity through binding to a heme binding site located between two RCKs; and binding of CO to heme relieved the inhibitory effect [144]. In addition, HO catalyzed metabolism of heme to produce CO in the presence of O2 [145]. HO-2 and BKCa channels formed a complex in carotid body and HO-2 acted as an O2 sensor to regulate BKCa channel activity [146]. The generation of CO by HO-2 bound to BKCa channel could provide a rapid and specific modulation of the channel. Although HO-2 and BKCa channel could form a complex in pulmonary artery, hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction was not altered in HO-2-deficient or BKCa-deficient mice [147]. Thus, this mechanism did not contribute to modulation of BKCa channels in VSMCs during exposure to hypoxia.

BKCa channel function in physiological conditions

Development and aging

Aging and development are accompanied by complex changes of vascular structure and function. Development alteres the contribution of BKCa and voltage-gated K1 (KV) channels to setting resting membrane potential in pulmonary arterial myocytes. [RE4]Whereas BKCa currents predominate in ovine fetal myocytes, KV currents became the major player in adult myocytes [148]. The expression of BKCa and KV channels followed the same pattern [149,150]. By contrast, BKCa activity in systemic vasculature increased during development. The human adult aortic myocytes exhibited a higher BKCa current density and longer open duration than in the fetal cells [151]. Similarly, activity of BKCa channels is progressively upregulated in rat aortic myocytes after birth [152].

Vasorelaxation was attenuated with the advance of age [153]. Correspondingly, activity of BKCa channels in VSMCs significantly decreased during aging [154,155]. Electrophysiological studies revealed that compared with young F344 rats, current density of BKCa channel in coronary arterial myocytes significantly decreased in the old rats [156–158]. Accordingly, expression of α– and β-subunits was decreased. Dramatic reduction in BKCa channel expression was also observed in aged human coronary artery [156]. Vasoconstriction of coronary artery induced by iberiotoxin in the old rat was also blunted compared with the young rat [156,157], suggesting a significantly decrease in the contribution of BKCa channels in regulation of vascular tone. Therefore, downregulated BKCa channel activity and expression likely have important roles in an increased risk of coronary spasm and myocardial ischemia in the elderly. The protein levels of BKCa α-subunit were also downregulated with age in arterioles from rat skeletal muscles [159]. However, BKCa channel function and expression remained unchanged in the cerebral artery [160].

Pregnancy and ovarian cycle

Uterine blood flow increases substantially during pregnancy to meet metabolic requirements for the growth and survival of the fetus. Pregnancy was associated with decreased myogenic tone of ovine uterine artery, which was abolished by blockade of BKCa channels [17]. Moreover, a significant portion of the increased uterine blood flow was attenuated by intra-arterial infusion of TEA [161,162]. Therefore, enhanced BKCa channel function has an important role in the adaptive changes of uterine circulation. Electrophysiological studies confirmed this notion by demonstrating enhanced BKCa channel activity in uterine arterial myocytes during pregnancy [17]. RT-PCR and Western blot revealed a significant increased expression of β1 subunit in this vascular bed [17,31]. The increased β1 subunit expression enhanced Ca21-sensitivity and BKCa channel activity, which in turn led to decreased vascular tone and increased blood flow. Considering increased eNOs[RE5] expression and activity [163,164] and increased cGMP and PKG in uterine artery during pregnancy [31], it is likely that modulation of BKCa channel activity by augmented NO-cGMP-PKG signaling pathway could provide additional regulation on uterine vasoreactivity.

Uterine blood flow also increases during follicular phase of the ovarian cycle [165]. Coincidentally, expression of BKCa channels, β1, but not α-subunit was also increased in addition to upregulated cGMP-PKG signal pathway. This increased uterine blood flow could be mimicked by administrating 17β-estradiol systemically or directly in the uterine circulation in ovariectomized nonpregnant ewes, and large portion of it was mediated by 17β-estradiol-stimulated activation of BKCa channels in uterine arterial myocytes [72].

Pulmonary circulation adjustment at birth

Fetal pulmonary vasculature remains constricted in utero. At birth, resistance in the pulmonary vasculature decreases, leading to vasodilation and perfusion of the lung. Pulmonary vasodilation induced by increasing fetal oxygen tension in acutely instrumented fetal sheep was blocked by BKCa channel blockers [166], suggesting the involvement of activated BKCa channels. [RE6]Electrophysiological recording confirmed this notion. BKCa channel activity in fetal ovine and rabbit pulmonary arterial myocytes was increased by elevating oxygen partial pressure (pO2) [166,167]. The enhanced BKCa channel function in turn caused membrane hyperpolarization.

Fetal pulmonary arterial myocytes cultured under hypoxic condition or under normoxic environment in the presence of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) mimetic deferoxamine resulted in increased expression of both α and β1 subunit transcripts [168]. HIF-1 is the main transcription factor sensing changes in pO2, and putative HIF-1α-responsive sequences are present on the 5′ sequence of the gene of β1 subunit [169]. This upregulation of BKCa channel expression was proposed to prepare pulmonary vasculature to respond to perinatal vasodilator stimuli [170].

Exercise

In exercise-trained rats, acetylcholine-induced vasorelaxation of rat mesenteric artery and aorta was enhanced, which was partially suppressed by BKCa channel blockers [171]. Moreover, exercise training enhanced BKCa channel blocker-induced contraction of coronary artery from Yucatan miniature swine [172]. BKCa channel current density was increased in coronary and aortic myocytes of exercise-trained rats and swine [158,173]. The enhanced BKCa channel activity was largely due to increased Ca21- and voltage-sensitivity [173]. Furthermore, exercise can have a beneficial role in improving cardiovascular function in aging and dislipidemia. In the rat model, aging caused a reduction of BKCa current density in coronary artery, which was accompanied by reduced expression of both α and β1 subunits [158]. Both depressed functional and molecular expression of BKCa channel could be partially reversed by exercise training. Diabetic dyslipidemia decreased STOCs mediated by BKCa channel in swine coronary myocytes [174]. The reduced BKCa channel function subsequently increased coronary tone. Exercise training effectively prevented both increased vascular tone and impaired BKCa channel function.

BKCa channel function in pathological conditions

Hypertension

Hypertension is the most prevalent risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, such as stroke and myocardial infarction. Considering the role of BKCa channels in regulating membrane potential and vascular tone, it is reasonable to rationalize that dysfunctional BKCa channels[RE7] in VSMCs could contribute to development of hypertension. Gene knockout studies demonstrated that targeted gene deletion of both α and β1 subunits resulted in increased vascular tone and elevated blood pressure [29,42,43]. Conversely, a genetic polymorphism inβ1 subunit of human BKCa channel (E65K), a gain-of-function mutation, was associated with a low prevalence of diastolic hypertension [175]. Some hypertension models also implicated BKCa channels in pathogenesis of hypertension. BKCa channel function in rat mesenteric artery was depressed in Nω-nitro-L-arginine-induced hypertension [176]. This impaired BKCa function was attributed to reduced expression of α subunit [177]. Rats chronically infused with angiotensin II demonstrate[RE8]d raised systolic blood pressure, and iberiotoxin-induced constriction of cerebral artery was attenuated [178]. Consistent with this observation, expression of β1, but not α, subunit in cerebral arterial myocytes was profoundly decreased, and the coupling of Ca21 sparks to BKCa channels was impaired. Similarly, expression of β1 subunit was depressed in cerebral artery of spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) [15]. However, selective loss of β1 subunit might not be sufficient to cause hypertension. A recent study suggests that β1 subunit null mice were not hypertensive based on continuous 24-hour blood pressure measurements [44]. In contrast to the findings in angiotensin II- and Nω-nitro-L-arginine-induced hypertensive rats, other experimental data suggest that vascular BKCa channel function was upregulated in both spontaneously hypertensive and deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt hypertensive rats. Enhanced vasoconstriction induced by BKCa channel blockers [179–181] and heightened BKCa channel activity [179,182,183] was observed in various blood vessels. In line with these findings, expression of α or β1 subunits was elevated [181–183]. The upregulated BKCa channel function was suggested to represent a compensatory mechanism to limit excessive vasoconstriction in hypertension [182].

Diabetes

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes cause vascular dysfunction. Myogenic tone was increased in cerebral arteries from streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetic rats [184] and mice [185] and type 2 diabetic BBZDR/Wor rats [186] and mesenteric artery from type 2 diabetic C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice [187]. In both type 1 and type 2 diabetes, vasoreactivity mediated by BKCa channels was impaired. Compared with non-diabetic animals, augmentation of agonist-induced vasoconstriction in mesenteric artery by iberiotoxin was lost, and membrane hyperpolarization by NS 1619 was decreased in Zucker Diabetic Fatty (ZDF) rats [188]. Vasoconstriction of cerebral artery induced by blockade of BKCa channels was attenuated in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats [185,189]. Similarly, vasodilation by BKCa channel opener BMS-191011 was absent in retinal artery of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats [190]. Therefore, capability of BKCa channels to oppose vasoconstriction is weakened in both types of diabetes. Electrophysiological experiments demonstrated that BKCa function was impaired in both type 1 [52,185,189] and type 2 [191,192] diabetic VSMCs. It appears that diabetes specifically targets theβ1 subunit of the BKCa channel. The expression of β1, but not α subunit was reduced in type 1 [185,193,194] and insulin-resistant and/or type 2 diabetes [189,192]. Considering the role of β1 subunit in regulating BKCa activity, it is not surprising that impaired BKCa channel function was associated with reduced Ca21 and voltage sensitivity [185,189,192,193]. The coupling of Ca21 sparks to BKCa channel was also impaired [185]. Diabetes was associated with enhanced production of ROS in VSMCs [195]. ROS acted as potent inhibitors of BKCa channels and produced a response similar to deletion of the β1 subunit [196]. Rotenone, a mitochondrial electron transport chain inhibitors, partially reversed generation of H2O2 and restored BKCa function in cerebral artery from streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice [195]. Hyperglycemia has an important role in development of BKCa channel dysfunction in diabetic patients. In the recombinant system, culturing HEK 293 cells expressing hSlo[RE9] in high glucose enhanced superoxide dismutase and suppressed catalase (CAT) expression, leading to increased production of ROS, which in turn inhibited channel function through interacting C911 located in the cytoplasmic domain of BKCa channels [95]. The actions of high glucose was mimicked by H2O2 and restored by CAT gene transfer. Functional studies also demonstrated that impaired BKCa channel-mediated vasodilation could be restored by superoxide dismutase and CAT treatment [197]. Long-term exposure cultured human coronary arterial myocytes to high glucose also led to downregulation of β1, but not α subunit through ubiquitination [194]. Attenuation of CO-induced vasorelaxation of tail artery from streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats was accompanied by a decreased sensitivity of BKCa channel to CO, which was mimicked by chronic exposure of the cultured VSMCs to high glucose [198]. A recent study revealed that BKCa channels, AT1R, caveolin-1 and c-Src are co-localized in caveolae of VSMCs, and upregulation of caveolin-1 expression in streptozotocin-induced rats with diabetes promote stronger association between BKCa channel and AT1R, leading to enhanced inhibition of BKCa channel by angiotensin pathway [52].

Hypoxia

BKCa channels could function as a chemosensor to detect changes in pO2 [199]. Modulation of BKCa channel activity in VSMCs by oxygen is crucial in regulating tissue perfusion and regional blood flow. Hypoxia is caused by a variety of physiological and pathophysiological conditions, such as ischemia, residence at high altitude and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BKCa channels contribute differently to hypoxic responses depending on the nature of hypoxia (acute or chronic) and vascular beds (pulmonary or systemic).

In general, acute hypoxia causes pulmonary vessels to constrict and systemic vessels to dilate to maintain adequate O2 delivery [199]. Altered BKCa channel activity in part accounts for the vascular responses induced by acute hypoxia. Acute hypoxia inhibited BKCa channel activity in pulmonary arterial myocytes [200,201], whereas it enhanced BKCa function in myocytes of cerebral and pial arteries [123,202]. Several potential mechanisms can account for the inhibitory effect of acute hypoxia in pulmonary myocytes. Acute hypoxia could alter the cytosolic redox state, which in turn inhibited BKCa channel activity in pulmonary myocytes [93]. In addition, a decrease in pO2 could directly exert its action on BKCa channels. In a recombinant system, acute hypoxia has been shown to reversibly inhibit BKCa channels activity through a decreased Ca21-sensitivity that was independent of soluble cytosolic factors [203].

Hemeoxygenase-2 (HO-2) and BKCa channels could form a complex in heterologous expressing system and HO-2 was proposed to function as an O2 sensor in carotid body [146]. Hypoxia exerts its inhibitory action on BKCa channel by reducing generation of CO, a BKCa channel activator, due to decreased supply of HO-2 substrate O2. However, targeted deletion of HO-2 nor BKCa channel genes failed to alter acute and chronic vascular responses to alveolar hypoxia in the lung [147]. The enhanced BKCa channel activity in cerebral artery likely involves altered generation of ROS and 20-HETE [123]. Generation of ROS in cerebral arterial myocytes was increased during exposure to acute hypoxia. In addition, hypoxia-stimulated BKCa channel activity was abrogated by a superoxide dismutase mimic. Furthermore, hypoxia caused a dramatic decrease endogenous 20-HETE level [RE10]which led to removal of the inhibitory effect of 20-HETE on BKCa channels [123]. These findings suggest that both redox modulation of BKCa channels by ROS and alleviation of 20-HETE inhibitory effect contribute to hypoxia simulated-BKCa function in cerebral artery. By contrast, acute hypoxia was observed to inhibit BKCa channel activity in cerebral artery by uncoupling Ca21 sparks to BKCa channel [204]. However, the physiological impact of hypoxia-mediated inhibition on BKCa channel in cerebral artery remains unclear since acute hypoxia causes cerebral vasodilation.

Chronic hypoxia depressed BKCa channel activity in rat and human pulmonary artery [205,206]. Although KV is the predominant K1 channel in regulating resting membrane potential in adult pulmonary arterial myocytes [148], depressed BKCa channel activity during prolonged exposure to hypoxia could also contribute to pulmonary vasoconstriction, leading to pulmonary hypertension. BKCa channel function in systemic vasculature is also altered by chronic hypoxia. Relaxation mediated by BKCa channel in both adult and fetal sheep cerebral arteries was impaired by long-term high altitude hypoxia [207]. Cultured rat basilar arterial myocytes displayed reduced BKCa channel activity after chronic exposure to hypoxia [208]. The reduced BKCa channel activity was associated with decreased Ca21- and voltage-sensitivity of the channel [205]. Chronic hypoxia also depressed BKCa channel activation stimulated by PKA and PKG [205,209]. In addition to post-translational modification of the channel, chronic hypoxia also alters BKCa channel expression. In response to chronic hypoxia expression of α subunit was reduced in rat pulmonary artery [210]. Expression of β1 subunit was also decreased in cultured myocytes from rat aorta, rat basilar artery and human mammary artery after prolonged hypoxia treatment [208].

Ischemia presents a hypoxic insult to tissues and organs. BKCa channel activity and vasorelaxation mediated by BKCa channels were depressed following ischemia for 1 hour in porcine coronary myocytes [211]. However, vasorelaxation of human coronary artery induced by BKCa channel opener NS 1619 was not affected after cardiopulmonary bypass, and expression of both α and β1 subunits remain unchanged [212]. In addition, BKCa channel function in cerebral artery was largely not affected by ischemia [213].

Shock

Vascular BKCa channels have been proposed to contribute to development of endotoxic and hemorrhagic shock [214]. VSMC membrane became hyperpolarized in both endotoxic and hemorrhagic shock rats [16,215]. In addition, both types of shock were associated with vascular hyporeactivity to norepinephrine. BKCa channel blockers partially reversed both membrane hyperpolarization and attenuated vasoconstriction induced by norepinephrine. Similarly, impaired vascular reactivity to norepinephrine was restored by BKCa channel blockers in human brachial artery during endotoxiemia [216]. Those findings implicate BKCa channels in the development of hypotension. Further evidence came from electrophysiological experiments, which demonstrated that endotoxin lipopolysaccharide increased BKCa channel activity in cerebral arterial myocytes [217]. BKCa channel activity was also increased in mesenteric artery from hemorrhagic shock animals [16]. The elevation of BKCa activity was the result of increased expression of β1 subunit and enhanced coupling of Ca21 sparks to BKCa channel.

Other cardiovascular dysfunctions

Both myogenic tone and membrane depolarization of cerebral artery increase after subarachnoid hemorrhage [218,219]. It was found that blockade of BKCa channel caused constriction of cerebral artery from control, but not subarachnoid hemorrhage animals. In addition, both Ca21 sparks and STOCs were reduced [220]. Those findings imply impaired BKCa channel function in cerebral artery following subarachnoid hemorrhage. However, functional properties and expression of BKCa channels remained unaltered in cerebral artery from several models of subarachnoid hemorrhage [218,220]. Cirrhosis upregulated BKCa channel α-subunit expression in rat mesenteric artery and enhanced BKCa channel-mediated vasodilation [221]. BKCa channel activity was reduced in rabbit and porcine coronary arterial myocytes during left ventricular hypertrophy [222,223]. The impaired BKCa channel function was not due to alternation of BKCa channel expression, but conferred by reduced Ca21-sensitivity of the channel.

BKCa channel as a therapeutic target of cardiovascular dysfunction

As mentioned above, BKCa channels play an important role in the regulation of membrane potential of VSMCs which in turn controls vascular tone; and various physiological and pathophysiological conditions, including hypertension, shock, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, which are associated with altered BKCa channel function in VSMCs. Therefore, BKCa channels constitute a major target for treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Several strategies are potentially useful in combating these cardiovascular dysfunctions.

The most common and convenient approach is pharmacological manipulation. A variety of compounds have been developed to either activate or inhibit BKCa channels [224]. Hypoactivity of BKCa channels could be boosted by BKCa channel openers, whereas hyperactivity of the channel might be suppressed by BKCa channel blockers. The prototype BKCa channel opener benzimidazolones, such as NS 1619 and NS 004 interact with α-subunit to enhance channel function [225]. However, their clinical use is hampered by low efficacy and lack of selectivity. In fact, clinical trials involving other BKCa channel openers, such as NS 8, BMS204352 and TA1702 have been discontinued [224]. The BKCa channel α-subunit is ubiquitously expressed whereas β1 subunit is predominantly expressed in smooth muscle cells [29,30,226]. Therefore, development of molecules that selectively target the β1 subunit would be favorable for treating cardiovascular diseases associated with altered BKCa channel function in VSMCs. The studies by Dopico and colleagues are encouraging; and the authors reported that cholane-derived steroid lithocholate stimulated BKCa channel activity by selectively interacting with β1 but not β2–4 subunits [227]. Thus, lithocholate could serve as a template for developing subunit-selective BKCa channel openers.

By contrast, a local delivery of a BKCa channel gene could provide an alternative treatment for impaired BKCa channel activity. Intracorporal microinjection of naked BKCa channel gene (pcDNA-hSlo) enhanced erectile function [228]. Preliminary results from a human clinical trial were promising and showed safety and efficacy [229]. Recently, work from the same group demonstrated the effectiveness of smooth muscle-specific gene transfer with the human BKCachannel in atherosclerotic cynomolgus monkeys using a vector containing smooth muscle α-actin promoter [230]. Therefore, tissue-specific delivery of BKCa channel gene together with application BKCa channel modulators could provide an efficient treatment of BKCa channel-related cardiovascular dysfunctions.

Altered BKCa channel function could also be corrected indirectly. Endothelium of blood vessels is the sources of a variety of vasodilators, such as NO, prostacyclin, and cytochrome P-450 metabolites EETs [231]. Drugs that increase production of those molecules would then heighten BKCa channel activity in VSMCs. Furthermore, delivery of cytochrome P-450 epoxygenase gene into VSMCs increased 14,15-EET release and subsequently enhanced BKCa channel activity [232]. This approach could provide another possibility for managing dysfunction of BKCa channel in VSMCs.

Concluding remarks

In summary, BKCa channels have been implicated in setting resting membrane potential and regulating vascular tone. Vascular responses exerted by various vasoactive substances involve activation or inhibition of BKCa channel in VSMCs. In addition, BKCa channels in VSMCs are subjected to a variety of modulations involving genomic and non-genomic mechanisms. Furthermore, alterations of BKCa channels in VSMCs have been documented in both physiological and pathophysiological conditions, such as aging and/or development, pregnancy, hypertension, diabetes, and hypoxia. However, precise mechanisms underlying the altered functional and molecular expression of BKCa channel in VSMCs remains to be elucidated in future studies. Information obtained from these studies will expand our understanding of physiological and pathophysiological roles of BKCa channels in cardiovascular adaptation and dysfunctions, and facilitate translating the knowledge into design of effective therapeutics. Effective manipulation of BKCa channel activity by development of subunit-specific BKCa channel modulators and tissue-specific gene delivering techniques will be key to the treatment of cardiovascular diseases associated with altered expression and activity of BKCa channels in VSMCs.

Highlights.

BKCa channels are abundantly expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells

BKCa channels participate in regulation of vascular tone and blood pressure

BKCa channels are a key player in both cardiovascular adaption and dysfunctions

Developing therapeutics is crucial to treat diseases due to BKCa channel alterations

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants HL89012 (LZ), HL110125 (LZ), and HD31226 (LZ). We apologize to those authors whose excellent studies covered by the scope of this review were unable to be cited due to space restriction.

Biographies

Dr Zhang is professor of Pharmacology and Physiology at Loma Linda University School of Medicine. He was the President of the Western Pharmacology Society in the USA in 2008. He has been members in the various study sections of grant review for US National Institutes of Health and American Heart Association for more than 15 years. Dr Zhang is the author/coauthor of over 480 scientific articles, book chapters and abstracts. His research interests focus on the molecular mechanisms in the uteroplacental circulation and developmental programming of adult cardiovascular disease.

Dr Hu received his PhD degree in Pharmacology from Iowa State University in 1994. He did his postdoctoral training at the Center for Perinatal Biology at Loma Linda University and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The focus of his work has been the regulation of ion channels including voltage-gated ion channels in smooth muscle and ligand-gated ion channels in the central nervous system.

Footnotes

Teaser Sentence: BKCa channels in VSMCs are key players in both cardiovascular adaption and dysfunctions during physiological and pathophysiological conditions and constitutes a potential therapeutic target for cardiovascular disorders associated with altered BKCa channel activity.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wei AD, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. LII Nomenclature and molecular relationships of calcium-activated potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:463–472. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feletou M. Calcium-activated potassium channels and endothelial dysfunction: therapeutic options? Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:545–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tharp DL, Bowles DK. The intermediate-conductance Ca21-activated K1 channel (KCa3.1) in vascular disease. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2009;7:1–11. doi: 10.2174/187152509787047649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill MA, et al. Large conductance, Ca21-activated K1 channels (BKCa) and arteriolar myogenic signaling. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2033–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kohler R, et al. Vascular KCa-channels as therapeutic targets in hypertension and restenosis disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:143–155. doi: 10.1517/14728220903540257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latorre R, et al. Allosteric interactions and the modular nature of the voltage- and Ca21-activated (BK) channel. J Physiol. 2010;588:3141–3148. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salkoff L, et al. High-conductance potassium channels of the SLO family. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:921–931. doi: 10.1038/nrn1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee US, Cui J. BK channel activation: structural and functional insights. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:415–423. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma Z, et al. Role of charged residues in the S1–S4 voltage sensor of BK channels. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:309–328. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia XM, et al. Multiple regulatory sites in large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Nature. 2002;418:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature00956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu G, et al. Locations of the beta1 transmembrane helices in the BK potassium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10727–10732. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805212105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka Y, et al. Molecular constituents of maxi KCa channels in human coronary smooth muscle: predominant α 1β subunit complexes. J Physiol. 1997;502:545–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.545bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding JP, et al. Inactivating BK channels in rat chromaffin cells may arise from heteromultimeric assembly of distinct inactivation-competent and noninactivating subunits. Biophys J. 1998;74:268–289. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77785-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang YW, et al. Consequences of the stoichiometry of Slo1 α and auxiliary β subunits on functional properties of large-conductance Ca21-activated K1 channels. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1550–1561. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01550.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amberg GC, Santana LF. Downregulation of the BK channel β1 subunit in genetic hypertension. Circ Res. 2003;93:965–971. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000100068.43006.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao G, et al. Hypersensitivity of BKCa to Ca21 sparks underlies hyporeactivity of arterial smooth muscle in shock. Circ Res. 2007;101:493–502. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.157271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu XQ, et al. Pregnancy upregulates large-conductance Ca21-activated K1 channel activity and attenuates myogenic tone in uterine arteries. Hypertension. 2011;58:1132–1139. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.179952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie J, McCobb DP. Control of alternative splicing of potassium channels by stress hormones. Science. 1998;280:443–446. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L, et al. Functionally diverse complement of large conductance calcium- and voltage-activated potassium channel (BK) α-subunits generated from a single site of splicing. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33599–33609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chiu YH, et al. Dominant-negative regulation of cell surface expression by a pentapeptide motif at the extreme COOH terminus of an Slo1 calcium-activated potassium channel splice variant. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;77:497–507. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.061929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu N, et al. Alternative splicing of Slo channel gene programmed by estrogen, progesterone and pregnancy. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4856–4860. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.07.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian L, et al. Alternative splicing switches potassium channel sensitivity to protein phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7717–7720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dworetzky SI, et al. Phenotypic alteration of a human BK (hSlo) channel by hSlobeta subunit coexpression: changes in blocker sensitivity, activation/relaxation and inactivation kinetics, and protein kinase A modulation. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4543–4550. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-15-04543.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cox DH, Aldrich RW. Role of the β1 subunit in large-conductance Ca21-activated K1 channel gating energetics. Mechanisms of enhanced Ca21 sensitivity. J Gen Physiol. 2000;116:411–432. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lippiat JD, et al. Properties of BKCa channels formed by bicistronic expression of hSlo α and β1–4 subunits in HEK293 cells. J Membr Biol. 2003;192:141–148. doi: 10.1007/s00232-002-1070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knaus HG, et al. Primary sequence and immunological characterization of beta-subunit of high conductance Ca21-activated K1 channel from smooth muscle. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17274–17278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knaus HG, et al. Subunit composition of the high conductance calcium-activated potassium channel from smooth muscle, a representative of the mSlo and slowpoke family of potassium channels. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3921–3924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCobb DP, et al. A human calcium-activated potassium channel gene expressed in vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H767–H777. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.3.H767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brenner R, et al. Vasoregulation by the β1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature. 2000;407:870–876. doi: 10.1038/35038011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanaka Y, et al. β1-subunit of MaxiK channel in smooth muscle: a key molecule which tunes muscle mechanical activity. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;94:339–347. doi: 10.1254/jphs.94.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenfeld CR, et al. Pregnancy modifies the large conductance Ca21-activated K1 channel and cGMP-dependent signaling pathway in uterine vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H1878–H1887. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01185.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wulf H, et al. Molecular investigations of BKCa channels and the modulatory β-subunits in porcine basilar and middle cerebral arteries. J Mol Histol. 2009;40:87–97. doi: 10.1007/s10735-009-9216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perez GJ, et al. Micromolar Ca21 from sparks activates Ca21-sensitive K1 channels in rat cerebral artery smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1769–C1775. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.6.C1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganitkevich V, Isenberg G. Isolated guinea pig coronary smooth muscle cells. Acetylcholine induces hyperpolarization due to sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release activating potassium channels. Circ Res. 1990;67:525–528. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.2.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guia A, et al. Local Ca21 entry through L-type Ca21 channels activates Ca21-dependent K1 channels in rabbit coronary myocytes. Circ Res. 1999;84:1032–1042. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.9.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C799–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jackson WF. Potassium channels in the peripheral microcirculation. Microcirculation. 2005;12:113–127. doi: 10.1080/10739680590896072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial tone by activation of calcium- dependent potassium channels. Science. 1992;256:532–535. doi: 10.1126/science.1373909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hill CE, et al. Role of maxi-K1 channels in endothelin-induced vasoconstriction of mesenteric and submucosal arterioles. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G1087–G1093. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.5.G1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fallet RW, et al. Influence of Ca21-activated K1 channels on rat renal arteriolar responses to depolarizing agonists. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F583–F591. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.4.F583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gschwend S, et al. Coronary myogenic constriction antagonizes EDHF-mediated dilation: role of KCa channels. Hypertension. 2003;41:912–918. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000063883.83470.7B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sausbier M, et al. Elevated blood pressure linked to primary hyperaldosteronism and impaired vasodilation in BK channel-deficient mice. Circulation. 2005;112:60–68. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000156448.74296.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pluger S, et al. Mice with disrupted BK channel β1 subunit gene feature abnormal Ca21 spark/STOC coupling and elevated blood pressure. Circ Res. 2000;87:E53–E60. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu H, et al. Large-conductance Ca21-activated K1 channel β1-subunit knockout mice are not hypertensive. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H476–H485. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00975.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahn DS, et al. Activation of Ca21-activated K1 channels by beta agonist in rabbit coronary smooth muscle cells. Yonsei Med J. 1995;36:232–242. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1995.36.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White RE, et al. cAMP-dependent vasodilators cross-activate the cGMP-dependent protein kinase to stimulate BKCa channel activity in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2000;86:897–905. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.8.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayabuchi Y, et al. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor activates Ca21-activated K1 channels in porcine coronary artery smooth muscle cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998;32:642–649. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199810000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miyoshi H, Nakaya Y. Calcitonin gene-related peptide activates the K1 channels of vascular smooth muscle cells via adenylate cyclase. Basic Res Cardiol. 1995;90:332–336. doi: 10.1007/BF00797911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhu S, et al. PGE2 action in human coronary artery smooth muscle: role of potassium channels and signaling cross-talk. J Vasc Res. 2002;39:477–488. doi: 10.1159/000067201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alioua A, et al. Coupling of c-Src to large conductance voltage- and Ca21-activated K1 channels as a new mechanism of agonist-induced vasoconstriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14560–14565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222348099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Minami K, et al. Protein kinase C-independent inhibition of the Ca21-activated K1 channel by angiotensin II and endothelin-1. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;49:1051–1056. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)98500-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lu T, et al. Regulation of coronary arterial BK channels by caveolae-mediated angiotensin II signaling in diabetes mellitus. Circ Res. 2010;106:1164–1173. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scornik FS, Toro L. U46619, a thromboxane A2 agonist, inhibits KCa channel activity from pig coronary artery. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C708–C713. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.3.C708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lange A, et al. 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-induced vasoconstriction and inhibition of potassium current in cerebral vascular smooth muscle is dependent on activation of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27345–27352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan J, et al. Profiling the phospho-status of the BKCa channel α subunit in rat brain reveals unexpected patterns and complexity. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2188–2198. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800063-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sadoshima J, et al. Cyclic AMP modulates Ca-activated K channel in cultured smooth muscle cells of rat aortas. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:H754–H759. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.255.4.H754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams DL, Jr, et al. Guanosine 5′-monophosphate modulates gating of high-conductance Ca21-activated K1 channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9360–9364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peng W, et al. Regulation of Ca21-activated K1 channels in pulmonary vascular smooth muscle cells: role of nitric oxide. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:1264–1272. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.3.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Minami K, et al. Protein kinase C inhibits the Ca21-activated K1 channel of cultured porcine coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;190:263–269. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schubert R, et al. Protein kinase C reduces the KCa current of rat tail artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:C648–C658. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.276.3.C648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barman SA, et al. PKC activates BKCa channels in rat pulmonary arterial smooth muscle via cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L1275–L1281. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00259.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ling S, et al. Enhanced activity of a large conductance, calcium-sensitive K1 channel in the presence of Src tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30683–30689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barman SA, et al. cAMP activates BKCa channels in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle via cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L1004–L1011. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00295.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barman SA, et al. Protein kinase C inhibits BKCa channel activity in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L149–L155. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00207.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Feldman RD, Gros R. Rapid vascular effects of steroids - a question of balance? Can J Cardiol. 2010;26(Suppl A):22A–26A. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(10)71057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wellman GC, et al. Gender differences in coronary artery diameter involve estrogen, nitric oxide, and Ca21-dependent K1 channels. Circ Res. 1996;79:1024–1030. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.5.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tep-areenan P, et al. Mechanisms of vasorelaxation to 17β-oestradiol in rat arteries. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;476:139–149. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)02152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.White RE, et al. Estrogen relaxes coronary arteries by opening BKCa channels through a cGMP-dependent mechanism. Circ Res. 1995;77:936–942. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Han G, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha mediates acute potassium channel stimulation in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:1025–1030. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.093542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yu X, et al. Activation of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor induces endothelium-independent relaxation of coronary artery smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E882–E888. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00037.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang HT, et al. Daidzein relaxes rat cerebral basilar artery via activation of large-conductance Ca21-activated K1 channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;630:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rosenfeld CR, et al. Calcium-activated potassium channels and nitric oxide coregulate estrogen-induced vasodilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H319–H328. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.1.H319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nagar D, et al. Estrogen regulatesβ1-subunit expression in Ca21-activated K1 channels in arteries from reproductive tissues. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1417–H1427. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01174.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Valverde MA, et al. Acute activation of Maxi-K channels (hSlo) by estradiol binding to the beta subunit. Science. 1999;285:1929–1931. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5435.1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Node K, et al. Amelioration of ischemia- and reperfusion-induced myocardial injury by 17β-estradiol: role of nitric oxide and calcium-activated potassium channels. Circulation. 1997;96:1953–1963. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.6.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kundu P, et al. Regulation of mouse Slo gene expression: multiple promoters, transcription start sites, and genomic action of estrogen. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27478–27492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704777200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Danesh SM, et al. Distinct transcriptional regulation of human large conductance voltage- and calcium-activated K1 channel gene (hSlo1) by activated estrogen receptor alpha and c-Src tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:31064–31071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.235457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jamali K, et al. Effect of 17β-estradiol on mRNA expression of large- conductance, voltage-dependent, and calcium-activated potassium channel α and β subunits in guinea pig. Endocrine. 2003;20:227–237. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:20:3:227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Korovkina VP, et al. Estradiol binding to maxi-K channels induces their down- regulation via proteasomal degradation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1217–1223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jiang CW, et al. Progesterone induces endothelium-independent relaxation of rabbit coronary artery in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;211:163–167. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90524-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Au AL, et al. Activation of iberiotoxin-sensitive, Ca21-activated K1 channels of porcine isolated left anterior descending coronary artery by diosgenin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;502:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Deenadayalu VP, et al. Testosterone relaxes coronary arteries by opening the large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channel. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1720–H1727. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.4.H1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tep-areenan P, et al. Testosterone-induced vasorelaxation in the rat mesenteric arterial bed is mediated predominantly via potassium channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;135:735–740. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bucci M, et al. Hydrogen sulphide is involved in testosterone vascular effect. Eur Urol. 2009;56:378–383. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brem AS, et al. 11βOH-progesterone affects vascular glucocorticoid metabolism and contractile response. Hypertension. 1997;30:449–454. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brem AS, et al. Glucocorticoids inhibit the expression of calcium-dependent potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle. Mol Genet Metab. 1999;67:53–57. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1999.2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Baum M, Moe OW. Glucocorticoid-mediated hypertension: does the vascular smooth muscle hold all the answers? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1251–1253. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008040410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ambroisine ML, et al. Aldosterone-induced coronary dysfunction in transgenic mice involves the calcium-activated potassium (BKCa) channels of vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 2007;116:2435–2443. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.722009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wolin MS. Reactive oxygen species and the control of vascular function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296:H539–H549. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01167.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hayabuchi Y, et al. Hydrogen peroxide-induced vascular relaxation in porcine coronary arteries is mediated by Ca21-activated K1 channels. Heart Vessels. 1998;13:9–17. doi: 10.1007/BF02750638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]