Abstract

Patterns of waves, patches, and peaks of actin are observed experimentally in many living cells. Models of this phenomenon have been based on the interplay between filamentous actin (F-actin) and its nucleation promoting factors (NPF’s) such as Arp2/3 complex. Here we present an alternative biologically-motivated model for F-actin-NPF interaction based on properties of GTPases acting as NPFs. The model is a natural extension of a previous mathematical mini-model of small GTPases that generates a static cell polarization. GTPases (such as Cdc42, Rac) are known to promote actin nucleation, and to have active membrane-bound and inactive cytosolic forms. Like others, we assume that F-actin negative feedback shapes the observed patterns by suppressing the trailing edge of NPF-generated wave-fronts (hence localizing the activity spatially). We find that our NPF-actin model generates a rich set of behaviours, spanning a transition from static polarization to single pulses, reflecting waves, wave trains, and oscillations localized at the cell edge. The model is developed with simplicity in mind to investigate the interaction between NPF kinetics and negative feedback (weak vs strong for example), explain distinct types of pattern initiation mechanisms, patterns formed, and parameter regimes corresponding to such behaviours. It is shown that weak actin feedback yields static patterning, moderate feedback yields dynamical behaviour such as travelling waves, and strong feedback can lead to wave trains or total suppression of patterning. We use a novel nonlinear bifurcation analysis to explore the parameter space of this model and predict its behaviour with simulations validating those results.

Keywords: Actin waves, wave-pinning, refractory variable, nucleation promoting factors

1. Introduction

The nucleation and growth of the actin cytoskeleton is highly regulated in eukaryotic cells. Signalling networks and their downstream effectors control the nucleation, polymerization, severing, and depolymerization of filamentous actin (F-actin). Among such signalling agents are small GTPases, with Cdc42 and Rac known to be central regulators of the actin cytoskeleton and other cell functions [1]. Complex interactions between regulatory networks and F-actin give rise to spontaneous spatio-temporal patterns such as moving spots and spatially localized waves, observed in Dictyostelium [2, 3], neutrophils [4], fibroblasts [5], and other cell types. Recent studies using total internal reflection microscopy (TIRF) and improved fluorescent labels [6, 7, 8, 9] have implicated nucleation promoting factors (NPFs) such as Hem1 and the Arp2/3 complex in their formation. Whether F-actin waves have a functional significance is unclear, but it has been speculated that they are related to the cell’s exploration of its environment [4, 10], phagocytosis [11], and/or edge protrusion [12]. The roles of small GTPases in shaping F-actin is also universally recognized [1, 13, 14, 15], and we base our view of NPF’s on their properties.

This paper is aimed at elucidating the roles of NPF activation and F-actin negative feedback (weak vs strong) in the development of dynamic patterns. We are motivated by two related biophysical systems. 1) Small GTPases (such as Cdc42, Rac) are known to promote actin growth and are good candidates for NPF’s [14]. At the same time, a variety of experimental observations have provided evidence for feedback from F-actin to upstream signalling complexes, whether via the PI3K pathway [16, 17, 18] which links phosphoinositide crosstalk with small GTPases [19, 20], or by reciprocal interactions of cytoskeletal proteins with integrins and the resultant signalling events (See [21, 22] for a review.) Previous theoretical models [23, 24, 25], reviewed in [26], consider polarization as a standing wave of biochemical activity. In one such GTPase model, denoted ‘wave pinning’ [25, 27], a sufficiently large stimulus produces a travelling wave that stalls, leaving a polarized state. We investigate how embedding this GTPase module in a circuit that includes F-actin feedback leads to dynamic wave-like patterns. 2) Our second motivation is to contribute to previous theoretical analyses of actin waves [4, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32], reviewed in [33] by slightly changing the focus away from detailed, more complex treatment of actin. Most previous actin-waves models include either length or angular distributions of actin or even model individual filaments [30]. We remove this complexity and instead and instead systematically probe the effects of the interactions between NPF’s and F-actin. The resulting model is analytically tractable and displays rich dynamic behaviour, including static polarization, single waves that traverse the domain, persistent reflecting waves, wave trains, and oscillations localized at the cell edge. Our model suggests that NPF/F-actin interactions alone are capable of producing rich dynamic patterning.

2. The models

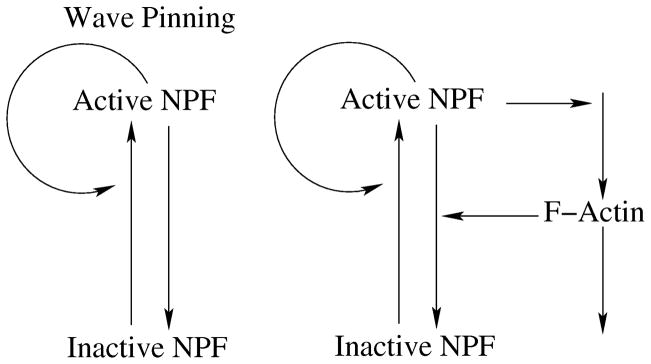

In the models discussed below, the NPF has two forms, an active membrane bound form (A), and an inactive cytosolic form (I), as shown in Fig. 1. Definitions and values of parameters are provided in Appendix B, and Table 1. We consider a 1D spatial domain where x is position along a “cell diameter” and t is time. This model could describe a two-dimensional square cell, whose protein concentrations are constant in one direction [30]. Balance equations of the form

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams of models discussed in this paper. Left: The pure NPF system is based on the wave-pinning model of Mori et al. [25]. Right: NPF/refractory actin system with a constant pool of G-actin G.

| (1a) |

| (1b) |

along with no flux boundary conditions are used to describe the NPFs. The active form A (resp. inactive form I) is taken to be membrane bound (resp. cytosolic). Note that the total amount of A + I is conserved by (1). A (resp. I) is assumed slow (resp. fast) diffusing so that DA ≪ DI. A simplified set of ‘wave pinning’ kinetics [25]

| (2) |

motivated by previous work on GTPases as NPFs [25], are used to describe cycling between these two forms, Fig. 1. Briefly, k0 is a basal activation rate, the Hill function represents autocatalytic positive feedback of A, and δ is an NPF inactivation rate. These terms are motivated biologically from known and hypothesized GTPase properties in [34, 35, 36, 25].

Our model differs from those of others [4, 28, 29, 32] in several ways. In [4], the NPF is identified with Hem1, assumed to autoactivate from a fixed inactive pool. Iglesias et al. [32] propose an excitable FitzHugh Nagumo type wave generator with additional components to account for features such as persistence and polarity. In [28], the NPFs also interconvert between active and inactive forms (with conserved total amount). Their kinetics are based on quadratic interaction terms (implying at most two steady states), whereas in our Eqn. (2) the Hill function saturating positive feedback term means that up to three A steady states exist for fixed I. This distinction is an essential feature of our model that leads to a type of wave behaviour not present in [28]. Whitelam et al. [29] take an altogether different approach and propose a model based on F-actin auto activation and degradation by another biochemical factor, not an NPF based model.

We embed these NPF kinetics in a circuit where the active NPF promotes F-actin (F) growth, which in turn feeds back to inhibit NPF activation, as shown in Fig. 1. F-actin is modelled by

| (3a) |

where h is a function of other variables (see below). The NPF kinetics (1a), (1b) are modified to include negative feedback from F

| (3b) |

A Hill coefficient n ≥ 2 is essential for wave-pinning behaviour. While n = 2 works, the relevant parameter regime for patterns is quite narrow, a problem that is corrected by using n = 3. The parameters s1, s2 set the relative weighting of basal NPF inactivation and F-actin-mediated NPF inactivation rates. δ sets the overall timescale of NPF degredation. Note that the pure NPF ‘wave-pinning’ scenario corresponds to s1 = 1, s2 = 0. The longer refractory timescale (in relation to the NPF timescale) on which the actin kinetics occur is defined by τ = 1/ε. Note that we do not include actin filament angular or length distributions.

It is assumed that F is nucleated from a constant (non-depleting) pool of monomeric G-actin (G), whose level affects only the rate constant kn. We thus take the function h to be

| (4) |

We assume that DA ≪ DI and that F is non-diffusive. Note that our calculations (not shown) indicate that taking F to be diffusive with DF ≈ DA does not appreciably affect the results. Substantially larger diffusion rates for F will however prevent waves from forming. Equations governing A, I, F are supplemented with no flux (homogeneous Neumann) boundary conditions and simulated numerically using the algorithm discussed in Appendix D.

As we wish to focus on the role of feedback, we concentrate on the parameters s1, s2, k0. The first two describe properties of feedback from actin to NPF’s, which is of primary interest here. The third (k0), represents a basal NPF activation rate and is known to be a key parameter for determining the sensitivity of the NPF model to perturbations. We map the parameter space with respect to these parameters and outline the stability of spatially uniform steady state solutions to both small and large perturbations. In order to provide context, we compare properties of the model to two well-studied pattern forming systems: the FitzHugh Nagumo model [37] and the wave pinning model [25]. Aside from this discussion, further details are provided in the Appendix.

Motivation for our models stems from the FitzHugh-Nagumo (FN) system (Appendix A) where a bistable wave-generating component produces a moving front and a second refractory component suppresses the trailing edge to create a localized travelling wave or pulse (Fig. 2). The formation of that wave stems from the (cubic) reaction kinetics. Large amplitude limit cycles arise in the spatially-independent model leading to oscillation between high and low activity; diffusion simply causes these regions to propagate in space, as a localized travelling wave. (The limit cycle stems from a sub-critical Hopf bifurcation, i.e. oscillations appear suddenly with finite amplitude as a parameter is varied [38].) Our model builds on this general structure but with reaction kinetics that produce different stability properties and long term dynamics.

Figure 2.

The FitzHugh Nagumo model provides motivation for our representation of F-actin and nucleation promoting factor (NPF) system. A wave-generator induces a travelling wave-front, which separates high and low states. A refractory variable suppresses the high trailing edge of the wave on a longer timescale, leading to a spatially localized wave.

In place of the bistable wave generator used in the FN model, our model uses the ‘wave pinning’ NPF model consisting of Eqs. (1), (2). As a stand alone model (i.e., no F feedback), it exhibits distinct regimes: (1) A classical ‘Turing regime’ where a uniform steady state is unstable to small spatially heterogeneous perturbations. (2) A ‘wave pinning regime’ where the uniform steady state is stable to all small perturbations, but unstable to perturbations beyond some threshold amplitude. Such perturbations initiate a travelling wave of A that propagates into the domain, thereby depleting I, and causing the wave front to slow down and eventually stall in the domain interior (under appropriate conditions). This module serves as the wave initiator in our model.

3. Results

We now describe the behaviours predicted by our model, focusing on how patterns are generated and their long term dynamics. We discuss the effects of two model elements on pattern forming regimes: (1) NPF conservation, (2) feedback between NPFs and F-actin. We show the negative feedback produces oscillatory behaviour which produces several type of localized travelling waves. These can arise either from an instability or from a distinct property, which we refer to as excitability, related to the wave pinning regime in the NPF model. On long timescales, we find distinct wave propagation regimes that contrast with dynamics of the FN system and correspond to different cellular behaviours. We first describe these behaviours, determined using numerical simulations, then apply a nonlinear perturbation analysis to understand the structure of the parameter space that gives rise to them.

3.1. Spatiotemporal dynamics

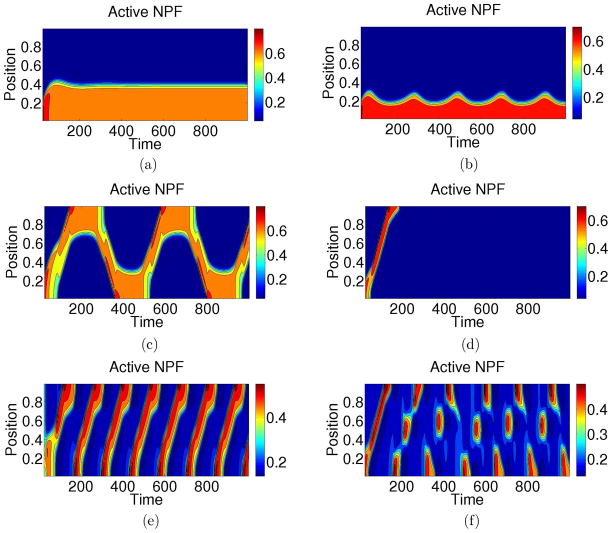

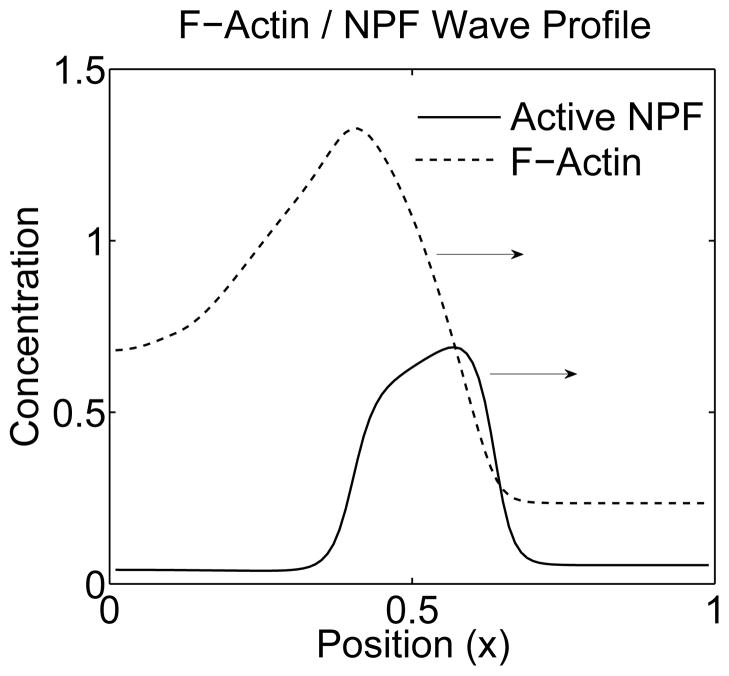

We simulated our model for a range of parameter values. Here we describe the long time behaviour of patterns that result in various parameter regimes. Representative results for A(x, t) are shown in Fig. 3 as intensity plots of A in the (x, t) plane (‘kymographs’). In each of these cases, patterning is induced with a localized perturbation of A at the x = 0 margin of the domain. A similar behaviour for F is observed, with a time delay in all cases. For example, in Fig. 4 we show a typical set of profiles for NPF and F-actin corresponding to the behaviour shown in panel (d) of Fig. 3. The NPF is relatively localized, and leads at the front. The F-actin profile follows, with a broader trailing edge. Note that the width of the trailing edge is modulated by ε.

Figure 3.

Simulations of our NPF/F-actin model, (Eqs. (1), (3b), (3a), (4) with a local perturbation at x = 0 used to initiate patterning. Parameter sets are drawn from Fig. 5 with remaining parameters in Table D1. For example, panel a is simulated with the parameter set labelled ‘a’ in that figure. Panels a – d are computed at fixed k0 with s2 varied. As s2 is increased patterns go from stable boundary localized (a), to oscillating boundary localized (b), to reflecting waves (c), to a single terminating wave (d), to no patterning. Panel e shows a wave train and panel f a more exotic pattern.

Figure 4.

Snapshot of the localized travelling wave profile of F and A from Fig. 3d at time T = 95. The wave of NPF leads, and is followed by a wave of F-actin. The F-actin suppresses the trailing edge of the NPF wave, producing a localized profile.

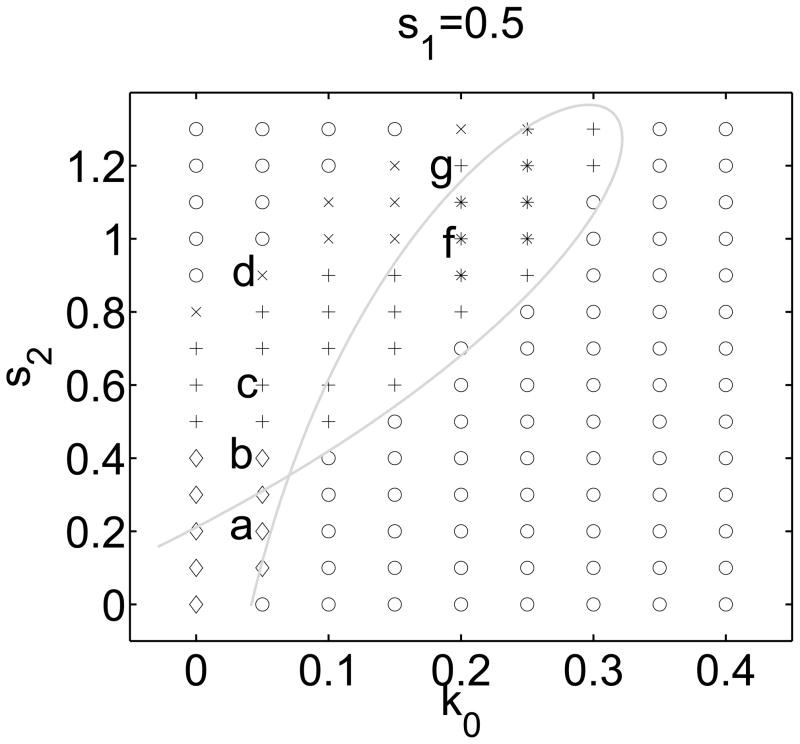

We find that the primary (in)activation parameters influencing the dynamic behavior of the system are k0, s1, and s2. Fig. 5 depicts a representative (k0, s2) slice of the parameter space, subdivided into regimes based on long term evolution of patterns. Holding other parameters constant (Table 1), we ran full PDE simulations for (k0, s2) grid values displayed in Fig. 5 and used an automated algorithm to classify the qualitative behaviour (Appendix D). Labelled points correspond to the panels in Fig. 3, demonstrating simulation results in different regimes. The grey bifurcation curve will be discussed shortly.

Figure 5.

The k0, s2 parameter plane, showing regimes of distinct patterning for our NPF/F-actin model (Eqs. (1), (3b), (3a), (4)), as determined by full simulations of the PDE model. Here, s1 = .5, ε = .1, and all other parameters as in SM Table 1. Initial conditions: HSS with a raised region of A (local perturbation) superimposed at the x = 0 boundary. Letters (a–f) correspond to patterns shown in the corresponding panels of Fig 3. Symbols: ○ - no patterning, ⋄ - boundary localized pattern, + -persistent reflecting wave, x - single terminating wave, * - persistent wave trains. The gray curve shows a two parameter continuation of the Hopf bifurcations in the LPA bifurcation plot of Fig. 6(b). The closed loop that forms represents an approximate boundary of a region where an oscillatory instability exists for the PDE system.

Fig. 5 and the associated kymographs in Fig. 3 show five primary patterning regimes (a–e) and several other exotic patterns that appear near borders between regimes, for example (f). Consider first the parameter sets in Fig. 3(a–d). These are computed with a fixed value of k0 and increasing values of s2 to show the role of increasing F-actin feedback s2. For low values of s2, the local perturbation of activity at x = 0 leads to a pattern that localizes at the boundary and remains there. This is similar to the s2 = 0 wave pinning case. As s2 is increased, we observe a transition regime, in which the region of activity begins to oscillate near the boundary (b) before it actually manages to separate when the feedback strength is larger (c). In that case, a localized travelling wave traverses the domain. Upon reaching the opposite boundary, the active region resides there for a period of time before separating and crossing the domain again. We refer to this as ‘reflecting wave’ behaviour. At yet higher values of s2 (d), once the wave arrives at the opposite boundary, it is suppressed. At even higher feedback strengths, regions of high activity never form. This progression shows that an appropriate level of feedback is essential: too little, and waves never propagate, too much and activity is simply suppressed.

Fig. 3e shows a fifth type of behaviour. Here, a wave of activity traverses the domain and in its wake, the refractory F level falls low enough that a new wave of activity can form. This leads to a ‘wave train’. Fig. 5 shows that this behaviour exists at higher values of the basal NPF activation rate k0 than for the reflecting waves. In this regime, if the domain size is increased, multiple waves coexist in time with a fixed separation distance determined by system parameters. Aside from the above five primary regimes, additional exotic patterns such as those shown in Fig. 3f are found in small regions at the boundaries of the primary regions. The full range of such exotic behaviour is beyond our scope here, and as these occur in limited parameter regions, our classification algorithm has not been designed to identify these details.

Fig. 5 confirms that a balance between k0 (NPF activation) and s2 (F-actin mediated NPF inactivation) is required for patterning. The upper left corner (high F feedback and low NPF activation) and the bottom right corner (low F feedback and high NPF activation) both correspond to no patterning, with a region of dynamic patterning inbetween. Another feature of interest is a band separating regimes of absent versus persistent patterning (indicated by the symbols ×). This shows that the transition between these regimes is not abrupt. We constructed similar parameter planes for several values of s1. These have similar structure, shifted due to increased basal inactivation for larger s1.

3.2. Bifurcation analysis of a local approximation

We now develop a novel bifurcation technique to map the parameter space of this model and detect the minimal stimuli needed to trigger patterning from a uniform state. For simplicity, the patterns in Fig. 3 are initiated with a (sufficiently large) perturbation of activity at the boundary x = 0. However in some regimes, such a perturbation is not necessary and instability causes patterns to grow spontaneously from noise, even at very low level. Traditionally, linear stability analysis (LSA) is used to look at stability properties of a homogeneous (spatially uniform) steady state solution (HSS). Such analysis can reveal Turing-type instabilities, but cannot ascertain whether larger amplitude perturbations grow or decay outside of these unstable regions. Furthermore, it becomes more challenging for models consisting of several variables, such as the one we propose.

Here we utilize a novel approximation to perform a nonlinear stability analysis of our model. To do so, we exploit the fast and slow diffusion scales to approximate the evolution of localized perturbations. This method, denoted ‘local perturbation analysis’ (LPA), and invented by Mareé and Grieneisen [39], uses a set of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to approximate the partial differential equations (PDEs) by taking the limits Dfast → ∞ and Dslow → 0 where I, G and A, F are assumed to be fast and slow diffusing respectively. The resulting system of ODEs (Appendix C) describes the initial growth or decay of a localized perturbation (of arbitrarily small width) applied to the HSS. An analysis of this system then provides an approximate bifurcation structure for the PDE system. This method is capable of detecting the presence of limit cycle oscillations (stemming from Hopf bifurcations in a well-mixed system) as well as spatial properties such as Turing instabilities, threshold responses such as wave pinning [25], and other dynamics. While it is a powerful method for determining where patterning can occur and due to what mechanism, it does not predict long term dynamics. We thus connect this analysis to the full PDE simulations described in above. Details of the approximating ODEs for the LPA are provided in Appendix C with a more extensive description in [40, 41].

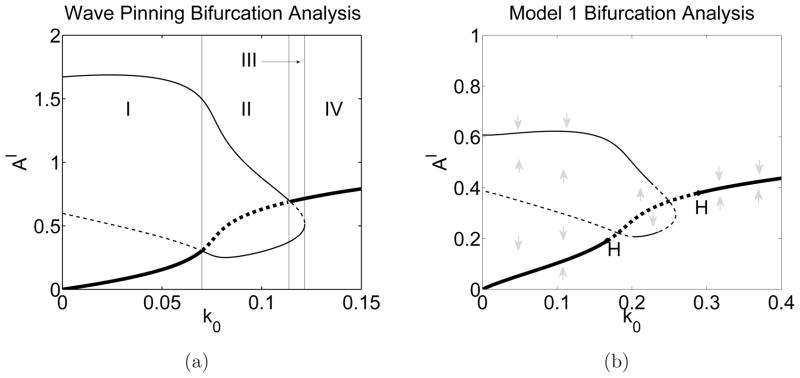

In Fig. 6, we show the LPA bifurcation plots for (a) the NPF (wave-pinning) model alone (Eqs 1–2), and compare it to a similar plot in (b) for our NPF/F-actin model to contrast the differences and understand the effect of F-actin feedback. The bifurcation parameter is k0, and the vertical axis is the amplitude of a localized perturbation of NPF activity (Aℓ).

Figure 6.

Nonlinear bifurcation analysis. Panel (a) the wave pinning model (Equations (1), (2)). Panel (b) our NPF/F-actin model, (Eqs. (1), (3b), (3a), (4)). Thick lines: HSS of the well-mixed system; thin lines: additional local states in the local perturbation system. Solid lines: stable states; dashed lines: unstable states. Panel (a) Three patterning regions are observed: I, III - wave pinning excitable response requiring a positive (resp. negative) valued perturbation, II - unstable response. In Region IV, the well mixed state is stable to all perturbations. Parameters used are γ = K = δ = 1 with the conserved quantity A + I = 2.27, taken from [25]. Panel (b) Structure similar to panel (a) but with two new Hopf bifurcations (H). These result from F-actin feedback. Between these, there is an oscillatory instability leading to wave dynamics. Parameters: s1 = 0.7, s2 = 0.7, τ = 0.1, and others as in SM Table 1. Gray arrows indicate the stability of branches.

We first explain the interpretation of panel (a): (1) the thick branch emanating from (0,0) and crossing the diagram represents the stability of the HSS to simple noise (solid line for stable and dashed for unstable HSS). The thin looped branch represents stability of the HSS to the localized perturbation as follows. In region I, the HSS is stable with respect to small perturbations (both uniform and spatially nonuniform). The thin dashed line in this region indicates a threshold. A localized NPF perturbation below this level will decay back to the HSS. Once this threshold is breached, the perturbation will jump to the stable thin branch indicating the formation of a pattern, (‘wave pinning’ in particular, in region I). This is the threshold-dependent (i.e. “excitable”) pattern-formation. The threshold diminishes as k0 approaches the boundary of region II where a bifurcation occurs. In that region, the HSS is unstable with respect to arbitrarily small spatial perturbations, indicative of a classical Turing instability. In region III, the HSS is again stable to noise, but excitable by a sufficiently large negative valued local perturbation. In Region IV, the HSS is stable to all perturbations, regardless of amplitude or sign. Thus, the results of LPA reveal two significant ‘excitable’ pattern forming regimes, I and III, and an unstable regime, II.

Comparing panels (a) and (b) of Fig. 6, we find common features. The shapes of the diagrams are similar, sharing regions that we recognize as excitable, and those we called unstable. A key difference is the appearance of a pair of Hopf bifurcations (labelled H), associated with oscillatory behaviour in panel (b). This new feature stems from F-actin negative feedback to the NPF module (absent in Fig. 6a). A two parameter bifurcation analysis with parameters k0 and s2, is shown as the grey curve in Fig. 5. Here we are primarily concerned with the loop portion of that curve since it partitions parameter space into regions of instability (inside the loop) and excitability (outside).

To connect this stability discussion to the long-term behaviours described above, consider first the boundary-localized patterns of Fig. 3(a,b). These patterns appear only in the excitable region; the limit cycle oscillations that appear inside the loop are inconsistent with static spatial patterns. Similarly, the single wave solution of Fig. 3d occurs only in the excitable regime. This is not surprising since both patterns have a stable character that is inconsistent with an oscillatory instability. The wave train solution in Fig. 3e, on the other hand, only occurs inside the unstable loop. The reflecting wave solution in Fig. 3c occurs in both regimes. Exotic patterns such as Fig. 3f appear near the edge of this loop. The consistency of the LPA results with the PDE simulation results confirms the relevance of the LPA to understanding long-term dynamic behavior.

3.3. Insights from model studies

In summary of our NPF/F-actin model, intermediate levels of refractory feedback are required to induce dynamic patterning. Too little feedback leads to stable patterns akin to those seen in pure NPF (wave-pinning) model. As feedback is progressively increased, static patterns start to oscillate, then become travelling waves; further feedback kills the waves as they arrive at boundaries, and finally leads to loss of all patterning by strong damping of all perturbations. It was also found that in different regimes, the waves that result take the form of either wave trains or reflecting waves.

We point out a few substantive differences between the mathematical structure of our model and that of the FitzHugh-Nagumo model. The FN waves are driven by oscillations of the reaction kinetics and diffusion simply converts those oscillations to travelling waves. Thus, unstable regimes lead to persistent wave trains and excitable regimes lead to single travelling waves that leave the stable HSS in their wake. The reaction kinetics in our NPF/F-actin model exhibit no such inherent oscillatory kinetics, and the resulting waves are, instead, driven by a combination of the wave pinning structure in the NPF module, which is intimately tied to diffusion, and refractory feedback. This difference leads to distinct behaviours such as reflecting waves, boundary localization, and the presence of persistent dynamics in excitable regimes not observed in the FN model.

4. Discussion

As shown in this paper, a small extension of a minimal model for Rho-GTPase (wave-pinning) dynamics [25] to include feedback from F-actin leads to a variety of novel spatiotemporal dynamics. The general structure of our NPF/F-actin model was motivated by two systems, the FitzHugh Nagumo (FN) model for impulse propagation in neurons and the ‘wave pinning’ model for small GTPases in eukaryotic cells, chosen here to represent a nucleation promoting factor (NPF). It was shown that the NPF triggers initial pattern formation and refractory F-actin produces spatially localized travelling waves. The resulting model exhibits a rich collection of dynamics including static polarization and boundary localized patterns, single waves, reflecting waves, wave trains, and more exotic patterns. The identification of NPFs with small GTPases is one hypothesis that distinguishes our model from other current models. This idea is based on extensive evidence for actin assembly downstream of Cdc42, Rac, and Rho [14, 42, 13], and on experimental observations that actin feedback affects PI3K-mediated pathways [18, 19, 16], and integrin signalling [22, 21] that are, in turn, known to affect small GTPases. However, many of our results would hold equally well for interpretations of A, I as forms of other actin-promoting factors with membrane bound and free cytosolic forms that interconvert rapidly.

To gain a better understanding of the parameter space and modes of pattern formation, we analyzed these systems with a novel nonlinear stability analysis that considers stability of homogeneous steady states with respect to localized perturbations. This analysis revealed the presence of two stability regimes, ‘excitable’ and unstable with the transition between them occuring at a PDE-variant of a Hopf bifurcation. In the first, only perturbations whose magnitude exceeds a threshold can trigger a pattern, whereas in the second, patterns arise from arbitrarily small noise. Combining these results with simulations, we connected the long term behaviour of patterns to these stability regimes. We found that wave trains are instability driven, reflecting waves occur in both regimes, and both transient wave and boundary localized patterns are present in excitable regimes. We subsequently suggested observed actin patterning phenomena to which these behaviours relate.

These systems are distinct from other current “actin waves” models [4, 28, 29, 32] both in structure and in richness of behaviours. The models in [4, 28] are designed around NPF models with unstable HSS’s and do not exhibit excitable behaviour. The model in Whitelam et al. [29] is structurally distinct hypothesizing that a biochemical inhibitor is responsible for patterning as opposed to an NPF. Being a direct extension of FN, it also likely does not account for persistent patterning outside of unstable regimes, a key requirement for stable systems that show persistent responses to transient stimuli. Our model thus suggests a mechanism for actin patterning that is substantially different from previous work on the topic and exhibits a broader range of behaviours.

While our model is simplified for maximal insight (and therefore not a detailed description of cellular events), it is tempting to draw connections between the dynamics predicted by our model and phenomena that are observed experimentally. The static boundary-localized pattern observed in Fig. 3a is indicative of a static polarization associated with chemotaxis where the NPF and F-actin co-localize at the front of a lamellipodium. The oscillating boundary pattern in Fig. 3b is reminiscent of experiments [43] in which the leading edge of the lamellipodium was found to oscillate. This oscillating state was induced by constitutive activation of the Rho GTPase Rac1, supporting the assumption that Rho GTPases are relevant to the dynamic behaviors found here. The travelling wave patterns in Figures 3(c–e) are similar to actin wave patterns observed in [2, 3, 4, 5, 7], for example. Developing a broad based conceptual framework for interpreting experimental observations and transitions between different dynamical behaviours is a key goal of this work.

Our model is a minimal representation of actin-NPF dynamics. In one sense, it is simpler than other current models, as we made no attempt to represent actin filament length or orientation that others consider [28, 31, 29, 30]. The absence of these details here indicates that, at least from the perspective of pattern dynamics and richness, the model structure is as important as biophysical details of F-actin. From a biophysical perspective, it is important to determine whether or not the feedbacks proposed here occur and are relevant to the formation of dynamic actin structures, and if so, what factors mediate that feedback. From a theoretical perspective, it is important to gain a more complete understanding of the propagation of these patterns and their connection to stability regimes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grant R01 GM086882 (to AEC and LEK) and an NSERC discovery grant (to LEK).

Appendix A. The FitzHugh Nagumo Model

The FitzHugh-Nagumo (FN) model [37], depicted in Fig. 2 is given by the equations

| (A.1a) |

where f is the cubic

| (A.1b) |

Originally meant as a caricature of impulse propagation in axons, v is identified with a fast-changing membrane voltage and w represents a more slowly varying property of ion channels. For sufficiently large γ, a wave of v propagates, increasing w in its wake. On a slightly longer timescale, increased w causes v to decrease leading to an impulse.

In this system, wave formation is driven almost exclusively by the reaction kinetics independent of any diffusive effects. A sub-critical Hopf bifurcation arises as γ is varied, leading to large amplitude limit cycle oscillations where v oscillates between two stable branches of the bistable kinetics for v. Further, the FN system demonstrates two behaviours. (1) Instability of the HSS gives rise to persistent oscillations in the reaction kinetics and persistent wave behaviour in the PDEs. (2) The HSS is stable and a large perturbation can give rise to a single wave which decays back to the HSS.

We point these properties out to contrast them to those of our model. The wave generating NPF reaction kinetics for our model do not exhibit limit cycle oscillations. Our wave generating NPF variable A, which is akin to v, is monostable. Instead, a distinct ‘wave pinning’ property that we describe next gives rise to waves. This distinction leads to the behaviours discussed in the main text.

Appendix B. Wave Pinning

The NPF module was motivated by the “wave-pinning” model for polarization of small GTPases [34, 35, 36, 25, 44], proposed as a mechanism for breaking symmetry and generating polarized patterns in cells. The WP model (Fig. 1a) is described by Equations (1), (2). Under the assumption DA ≪ DI, this model exhibits two basic pattern forming regimes: a classical Turing regime and a wave pinning regime, depicted in Fig. 6a. In the Turing regime, a single steady state of the well mixed kinetics is linearly stable but unstable to heterogeneous noise. In the wave pinning regime, a single steady state exists and is both linearly and Turing stable. Thus the well mixed kinetics alone do not suggest any pattern forming behaviour as is the case in the FN model. In this regime however, sufficiently large perturbations can initiate a travelling wave of high activity. As this wave propagates into the domain, it depletes the background inactive form I causing the wave to slow down, and in appropriate parameter regions, stall in the interior. Where bistability serves to initiate waves in the FN model, this mechanism serves as the primary wave generating component in our model. See [25, 27] for further exposition of wave pinning.

Appendix C. Nonlinear bifurcation analysis

The bifurcation analysis discussed in this paper is based on a nonlinear analysis that determines the stability of a homogeneous steady state (HSS) with respect to localized perturbations. The method, called the ‘Local Perturbation Analysis’ (LPA) was first introduced in [39] and more extensively developed in [40, 41]. We briefly describe it here. Consider a system of reaction diffusion (RD) equations with fast diffusing (u) and slow diffusing (v) variables

| (C.1) |

| (C.2) |

Here Dv ≫ Du and x ∈ Rd. (We identify u with active NPF, A, and actin F; v represents the fast diffusing NPF, I.) For simplicity, in this exposition we consider one slow and one fast diffusing variable. However, the method can be extended to consider families of slow (respectively fast) variables so that u, v are vectors.

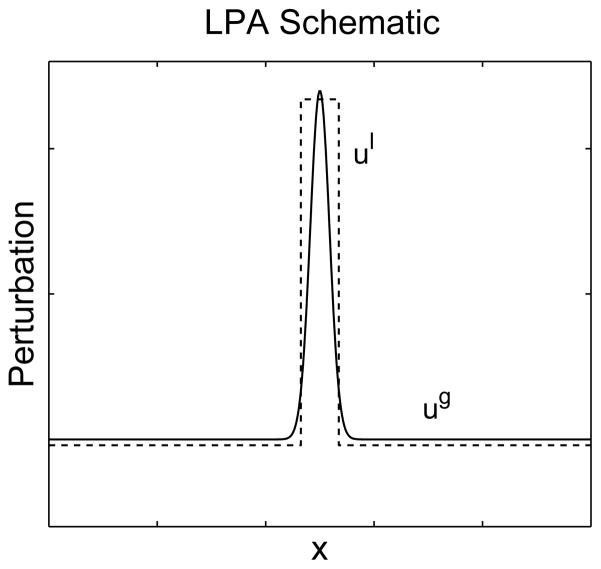

Consider the limit Dv → ∞. In this limit, the fast variable has only a global, homogeneous behaviour due to the very large diffusive length scale. Further, take the limit Du → 0 so that the slow variable has a purely local behaviour. Now apply a local perturbation to the slow variable u (Fig. 7). Then to a good approximation, u has a purely local behaviour (ul) near the perturbation, and a uniform global level (ug) elsewhere, which do not interact through diffusion when Du → 0. In contrast, v is purely global (vg) since in the limit Dv → ∞, spatial inhomogeneities are smoothed out immediately. The system of RD-eqs (C.1) can now be approximated by a set of ODE’s

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the local perturbation of u on which the ‘Local Perturbation Analysis’ (LPA) approximation is based. In the limit Du ≪ Dv, u takes on a local behaviour ul near the perturbation and ug globally. The fast diffusing variable v (not depicted) takes on a uniform global level, vg as any inhomogeneities are quickly smoothed out. The dashed line depicts the idealized local perturbation in the LPA diffusion limit, and the solid line is its realistic counterpart, where small but finite diffusion of u causes a slight outwards spread.

| (C.3) |

This approximation holds for some time until the perturbation is no longer localized.

ODEs have an advantage that automated bifurcation techniques can be applied, using one of several available software packages. (PDEs are still largely managed on a case-by-case basis.) As described in the main text, the bifurcation analysis of this reduced approximation provides information about the initial growth or decay of a localized perturbation in the RD system. A primary benefit of this method is that the applied local perturbation is of arbitrary height whereas other stability methods only consider small perturbations and cannot detect threshold behaviour. When the diffusion disparity in (C.1) is moderately large, the approximation leads to predictions about parameter dependence and types of pattern-forming instabilities that closely match the simulated behaviour of the full RD system. The approximation does not provide direct information about long term dynamics of the pattern; for this reason, full simulations of the PDEs are still needed. However, having this tool to map out relevant parameter regimes, and to see how changes in the structure of the model affect its overall behaviour proves enormously useful.

We demonstrate this analysis for the wave pinning system in Appendix B. We identify A and I as the slow and fast diffusing quantities. The reduced system of ODEs describing the stability of this system are

| (C.4) |

| (C.5) |

| (C.6) |

Conservation of these forms under the assumption that Al is confined to a local spatial region implies that Ag + Ig = T where T is the total conserved amount of material. The system then reduces to

| (C.7) |

| (C.8) |

A bifurcation analysis of this system using k0 as the bifurcation parameter produces Fig. 6a. The thick branch of states represents the HSS where no inhomogeneity is present (Al = Ag). The thin branches represent patterned states where Ag ≠ = Al.

Appendix D. Simulation Methods

All numerical simulations of the full system of RD-eqs were carried out with an implicit-diffusion explicit-reaction numerical scheme coded in MatLab (MathWorks). In all cases homogeneous Neumann boundary conditions were applied and 100 grid points were used. In Figs. 3,5, a pulse of A was applied to the left 5% of the domain to induce patterning, but a similar pulse in any other location would suffice. Similarly, perturbations in the form of a gradient also induce pattern but with different response thresholds. Bifurcation diagrams were produced using MatCont [45], a numerical continuation package designed in MatLab.

An automated algorithm was developed in MatLab to analyze the spatio-temporal pattern resulting from full RD simulations. Computed spatial profiles at time intervals ΔT = 5 were stored for each simulation. The maximum value, minimum value, and their spatial locations for A were found at each time. From this, the velocity of the maximum point was computed. These data were used to produce three properties of the solution.

Table D1.

Parameters used for our model. Typical units would be μM (concentration) μm (distance), and sec (time). NPF parameters are modified from [25] and actin parameters are chosen to illustrate a range of interesting dynamical behaviours.

| Parameter Name | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| k0 | 0 – 1 | Time−1 |

| γ | 1 | Time−1 |

| A0 | 0.4 | [concentration] |

| δ | 1 | Time−1 |

| s1 | 0 – 2 | Unitless |

| s2 | 0 – 2 | Unitless |

| F0 | 0.5 | [concentration] |

| kn | 1 | Unitless |

| ks | 0.25 | Unitless |

| TNPF | 1 | [concentration]×length |

| ε | 0.1 | Time−1 |

| L | 1 | Length |

| DA, DI | 10−3/3, 10−1/3 | Length2 Time−1 |

If |max(A) − min(A)| < η = 0.05 for all T > 500, the pattern is classified as transient. Otherwise it is called persistent.

If the location of the maximum is biased toward one domain boundary for all T > 500, the pattern is classified as boundary localized. Otherwise it is classified as dynamic.

If the maximum point moves in the same direction (i.e. its velocity has a fixed sign) for more than 2/3 of the time, the wave is classified as unidirectional. Otherwise it is classified as reflecting.

These criteria can be used to classify the following regular patterns demonstrated in Fig. 3: 1) no pattern, 2) boundary localized, 3) single terminating wave 4) persistent reflecting wave, 5) wave train. More exotic patterns such as Fig. 3f that were not the focus of this investigation can be misclassified by this algorithm.

References

- 1.Mackay Deborah JG, Hall Alan. Rho GTPases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(33):20685–20688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.20685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vicker MG. F-actin assembly in dictyostelium cell locomotion and shape oscillations propagates as a self-organized reaction-diffusion wave. FEBS Lett. 2002;510:5–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vicker MG. Eukaryotic cell locomoation depends on the propagation of self-organized reaction-diffusion waves and oscillations of actin filament assembly. J Expt Cell Res. 2002;275:54–66. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiner OD, Marganski WA, Wu LF, Altschuler SJ, Kirschner MW. An actin-based wave generator organizes cell motility. PLoS biology. 2007;5(9):e221, 2053–2063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millius Arthur, Dandekar Sheel N, Houk Andrew R, Weiner Orion D. Neutrophils establish rapid and robust wave complex polarity in an actin-dependent fashion. Current Biology. 2009;19:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bretschneider T, Diez S, Anderson K, Heuser J, Clarke M, Mueller-Taubenberger A, Koehler J, Gerisch G. Dynamic actin patterns and arp2/3 assembly at the substrate-attached surface of motile cells. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerisch G, Bretschneider T, Müller-Taubenberger A, Simmeth E, Ecke M, Diez S, Anderson K. Mobile actin clusters and traveling waves in cells recovering from actin depolymerization. Biophysical journal. 2004;87(5):3493–3503. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bretschneider T, Anderson K, Ecke M, Müller-Taubenberger A, Schroth-Diez B, Ishikawa-Ankerhold HC, Gerisch G. The three-dimensional dynamics of actin waves, a model of cytoskeletal self-organization. Biophysical journal. 2009;96(7):2888–2900. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiong Y, Huang CH, Iglesias PA, Devreotes PN. Cells navigate with a local-excitation, global-inhibition-biased excitable network. Proc Natl Acad Sciences. 2010;107:17079–17086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011271107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroth-Diez B, Gerwig S, Ecke M, Hegerl R, Diez S, Gerisch G. Propagating waves separate two states of actin organization in living cells. HFSP journal. 2009;3(6):412–427. doi: 10.2976/1.3239407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerisch G. Self-organizing waves that simulate phagocytic cup structures. PMC Biophysics. 2010;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1757-5036-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Driscoll Meghan K, McCann Colin, Kopace Rael, Homan Tess, Fourkas John T, Parent Carole, Losert Wolfgang. Cell shape dynamics: From waves to migration. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8(3):e1002392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ridley AJ. Rho GTPases and actin dynamics in membrane protrusions and vesicle trafficking. Trends in cell biology. 2006;16(10):522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998;279(5350):509–514. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sit Soon-Tuck, Manser Ed. Rho GTPases and their role in organizing the actin cytoskeleton. Journal of Cell Science. 2011;124(5):679–683. doi: 10.1242/jcs.064964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu J, Wang F, Van Keymeulen A, Herzmark P, Straight A, Kelly K, Takuwa Y, Sugimoto N, Mitchison T, Bourne HR. Divergent signals and cytoskeletal assemblies regulate self-organizing polarity in neutrophils. Cell. 2003;114(2):201–214. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00555-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasaki AT, Chun C, Takeda K, Firtel RA. Localized Ras signaling at the leading edge regulates PI3K, cell polarity, and directional cell movement. The Journal of cell biology. 2004;167(3):505–518. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasaki AT, Janetopoulos C, Lee S, Charest PG, Takeda K, Sundheimer LW, Meili R, Devreotes PN, Firtel RA. G protein–independent Ras/PI3K/F-actin circuit regulates basic cell motility. The Journal of cell biology. 2007;178(2):185–191. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiner OD, Neilsen PO, Prestwich GD, Kirschner MW, Cantley LC, Bourne HR, et al. A PtdInsP3-and Rho GTPase-mediated positive feedback loop regulates neutrophil polarity. Nature cell biology. 2002;4(7):509–513. doi: 10.1038/ncb811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang F, Herzmark P, Weiner OD, Srinivasan S, Servant G, Bourne HR, et al. Lipid products of pi (3) ks maintain persistent cell polarity and directed motility in neutrophils. Nature cell biology. 2002;4(7):513–518. doi: 10.1038/ncb810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calderwood DA, Shattil SJ, Ginsberg MH. Integrins and actin filaments: reciprocal regulation of cell adhesion and signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(30):22607–22610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R900037199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abram CL, Lowell CA. The ins and outs of leukocyte integrin signaling. Annual review of immunology. 2009;27:339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otsuji Mikiya, Ishihara Shuji, Co Carl, Kaibuchi Kozo, Mochizuki Atsushi, Kuroda Shinya. A mass conserved reaction–diffusion system captures properties of cell polarity. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3(6):e108. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goryachev Andrew B, Pokhilko Alexandra V. Dynamics of Cdc42 network embodies a turing-type mechanism of yeast cell polarity. FEBS Letters. 2008;582(10):1437–1443. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mori Y, Jilkine A, Edelstein-Keshet L. Wave-pinning and cell polarity from a bistable reaction-diffusion system. Biophysical Journal. 2008;94(9):3684–3697. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.120824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jilkine Alexandra, Edelstein-Keshet Leah. A comparison of mathematical models for polarization of single eukaryotic cells in response to guided cues. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7(4):e1001121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mori Y, Jilkine A, Edelstein-Keshet L. Asymptotic and bifurcation analysis of wave-pinning in a reaction-diffusion model for cell polarization. SIAM J Applied Math. 2011;71:1401–1427. doi: 10.1137/10079118X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doubrovinski K, Kruse K. Cytoskeletal waves in the absence of molecular motors. Europhysics Letters. 2008;83:18003p1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Whitelam S, Bretschneider T, Burroughs NJ. Transformation from spots to waves in a model of actin pattern formation. Physical review letters. 2009;102(19):198103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.198103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carlsson AE. Dendritic actin filament nucleation causes traveling waves and patches. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;104:228102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.228102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doubrovinski K, Kruse K. Cell motility resulting from spontaneous polymerization waves. Physical Review Letters. 2011;107(25):258103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.258103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iglesias PA, Devreotes PN. Biased excitable networks: how cells direct motion in response to gradients. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2012;24(2):245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carlsson AE. Actin dynamics: from nanoscale to microscale. Annual review of biophysics. 2010;39:91–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maree Athanasius FM, Jilkine Alexandra, Dawes Adriana, Grieneisen Veronica A, Edelstein-Keshet L. Polarization and movement of keratocytes: A multiscale modelling approach. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 2006;68:1169–1211. doi: 10.1007/s11538-006-9131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jilkine Alexandra, Maree Athanasius FM, Edelstein-Keshet Leah. Mathematical model for spatial segregation of the Rho-Family GTPases based on inhibitory crosstalk. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 2007;69:1943–1978. doi: 10.1007/s11538-007-9200-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dawes Adriana T, Edelstein-Keshet Leah. Phosphoinositides and rho proteins spatially regulate actin polymerization to initiate and maintain directed movement in a one-dimensional model of a motile cell. Miophysical Journal. 2007;92(3):744–768. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.090514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.FitzHugh R. Mathematical models of excitation and propagation in nerve. Vol. 1. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1969. pp. 1–85. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strogatz SH. Nonlinear dynamics and chaos: With applications to physics, biology, chemistry, and engineering. Westview Pr; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grieneisen Veronica. PhD thesis. University of Utrecht; 2009. Dynamics of Auxin Patterning in Plant Morphogenesis. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmes William R. The local perturbation analysis: a method for detecting spatio-temporal pattern forming capabilities in fast-slow reaction diffusion systems. Royal Society Interface. 2012 In Preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holmes William R. A local nonlinear stability analysis for reaction diffusion systems. SIAM Journal of Appl Math. 2012 In Preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pollard TD, Borisy GG. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 2003;112(4):453–465. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Machacek M, Danuser G. Morphodynamic profiling of protrusion phenotypes. Biophysical Journal. 2006;90(4):1439–1452. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.070383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goehring Nathan W, Trong Philipp Khuc, Bois Justin S, Chowdhury Debanjan, Nicola Ernesto M, Hyman Anthony A, Grill Stephan W. Polarization of PAR proteins by advective triggering of a pattern-forming system. Science. 2011;334(6059):1137–1141. doi: 10.1126/science.1208619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dhooge A, Govaerts W, Kuznetsov Yu A. Matcont: A Matlab package for numerical bifurcation analysis of ODEs. ACM TOMS. 2003;29:141–164. [Google Scholar]