Abstract

Objectives

Adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) among injection drug users (IDU) is often sub-optimal, yet little is known about changes in patterns of adherence since the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy in 1996. We sought to assess levels of optimal adherence to ART among IDU in a setting of free and universal HIV care.

Methods

Data was collected through a prospective cohort study of HIV-positive IDU in Vancouver, British Columbia. We calculated the proportion of individuals achieving at least 95% adherence in the year following initiation of ART from 1996 to 2009.

Results

Among 682 individuals who initiated ART, the median age was 37 (31–44) years with 248 (36.4%) female participants. The proportion achieving at least 95% adherence increased over time from 19.3% in 1996 to 65.9% in 2009 (Cochrane-Armitage test for trend: p < 0.001). In a logistic regression model examining factors associated with 95% adherence, initiation year was statistically significant (Odds Ratio = 1.08, 95% Confidence Interval: 1.03–1.13, p < 0.001 per year after 1996) after adjustment for a range of drug use variables and other potential confounders.

Conclusions

The proportion of IDU achieving at least 95% adherence during the first year of ART has consistently increased over a 13-year period. Although improved tolerability and convenience of modern ART regimens likely explain these positive trends, by the end of the study period a substantial proportion of IDU still had sub-optimal adherence demonstrating the need for additional adherence support strategies.

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, there have been remarkable advances in HIV treatment and care. In particular, antiretroviral therapy (ART) has resulted in dramatic reductions in morbidity and mortality for those living with HIV/AIDS (1, 2). However, HIV-positive injection drug users (IDU) have benefited less than other HIV-positive individuals from these advances largely due to reduced access and adherence to ART (3, 4). This is of particular concern given that, during the past two decades, the global HIV epidemic has transitioned from primarily a sexually driven epidemic to one in which syringe sharing among illicit IDU contributes to a significant proportion of infections (5). For instance, while IDU account for approximately 5% to 10% of HIV infections globally, this number increases to 30% outside of sub-Saharan Africa (6).

High levels of adherence are required to suppress levels of plasma HIV RNA (7), and incomplete adherence has been associated with virologic rebound and the emergence of antiretroviral resistance (8). The majority of research on adherence among IDU has focused on individual-level barriers including illicit drug use,(9) lower self-efficacy,(10, 11) and co-morbid psychiatric conditions;(12–14) however, longer term trends in adherence among IDU have not been well described. Thus, the present study evaluated long-term adherence patterns among IDU initiating ART between 1996 and 2009 in a setting of universal access to HIV care.

METHODS

Data for these analyses were collected through the AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate access to Survival Services (ACCESS), an ongoing community-recruited prospective cohort study of HIV-positive IDU which has been described in detail previously (15, 16). In brief, beginning in May 1996, participants were recruited through self-referral and street outreach from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, the local epicenter of drug-related transmission of HIV. At baseline and semi-annually, all HIV-positive participants provided blood samples and completed an interviewer-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire elicits demographic data as well as information about participants’ drug use, including information about type of drug, frequency of drug use, involvement in drug treatment and periods of abstinence. All participants provide informed consent and are remunerated $20 CDN for each study visit. The study is somewhat unique in that the province of British Columbia not only delivers all HIV care free of charge through the province’s universal healthcare system but also has a centralized HIV treatment registry. This allows for the confidential linkage of participant survey data to the Drug Treatment Program at the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS to a complete prospective profile of all HIV-related clinical monitoring and antiretroviral dispensation records. The Providence Health Care/University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board reviewed and approved the ACCESS study.

Participants were eligible for the present analysis if they initiated antiretroviral therapy between May 1996 and December 2009. The primary outcome in this study was adherence to antiretroviral therapy based on a previously-validated measure of prescription refill compliance (22, 23). Specifically, using data from the centralized ART dispensary, we defined adherence as the number of days for which ART was dispensed over the number of days an individual was eligible for ART in the year after ART was initiated. This calculation was restricted to each patient’s first year on therapy to limit the potential for reverse causation that could occur among patients who cease antiretroviral therapy after they have become too sick to take medication (17, 18). We have previously shown this measure of adherence to reliably predict both virological suppression (19–21) and mortality (22, 23). As in previous studies, adherence was dichotomized as ≥95% versus <95% (19, 21, 24). As an initial analysis, we calculated the proportion of individuals achieving at least 95% adherence to prescribed therapy in the year following initiation of ART during each year from 1996 to 2009 and used the Cochrane-Armitage test for trend to assess if rates of adherence changed over time.

We then examined factors independently associated with 95% adherence using logistic regression modeling and were specifically interested if year of ART initiation was associated with adherence after adjustment for potential confounders. We considered explanatory variables potentially associated with 95% adherence including: gender (female vs. male); age (<24 yrs. vs. ≥24 yrs.); ethnicity (Aboriginal ancestry vs. other); daily heroin injection (yes vs. no), daily cocaine injection (yes vs. no); daily crack cocaine smoking (yes vs. no); methadone use (yes vs. no); any other addiction treatment use (yes vs. no); and unstable housing (yes vs. no). Age was defined as a dichotomous variable according to the World Health Organization’s definition of a ‘young person’, using the upper age limit of 24 as the cut-off (25). All dichotomous behavioural variables referred to the six-month period prior to the interview. As in our previous work (26), we defined unstable housing as living in a single-room occupancy hotel, shelter or being homeless. Clinical variables included baseline HIV-1 RNA level (per log10copies/mL) and CD4 cell count (per 100 cells/mm3).

To estimate the independent relationship between calendar year and likelihood of 95% adherence to prescribed ART, we fit a multivariate logistic regression model using an a-priori defined protocol suggested by Greenland et al (27). First, we fit a full model including the primary explanatory variable and all secondary variables with p < 0.20 in univariate analyses. In a manual stepwise approach we fit a series of reduced models by removing one secondary explanatory variable, noting the change in the value of the coefficient for the primary explanatory variable. We then removed the secondary explanatory variable associated with the smallest absolute change in the primary explanatory coefficient. We continued this process until the maximum change from the full model exceeded 5%. This technique has been used in a number of studies to best estimate the relationship between an outcome of interest and a primary explanatory variable (28, 29). All statistical procedures were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). All p-values are two-sided.

Results

Between 1996 and 2009, 682 participants initiated ART and were eligible for the present analyses. Overall, the median age was 37 years (IQR: 31–44), 243 (36%) were Aboriginal and 248 (36%) were women.

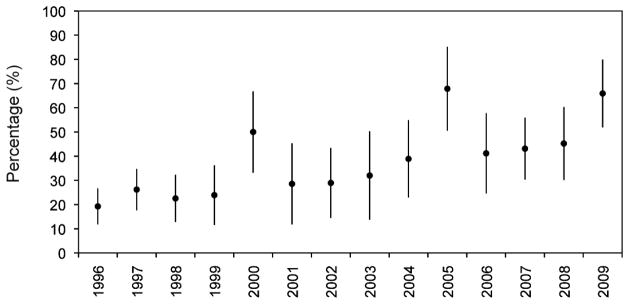

As shown in Figure 1, between 1996 and 2009 the proportion of individuals who achieved 95% adherence during the first year of ART increased from 19.3% in 1996 to 65.9% in 2009 (Cochrane-Armitage test for trend, p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Proportion of injection drug users with ≥95% antiretroviral adherence* from 1996 to 2009.

*Adherence defined based on prescription refill compliance.

As shown in Table 1, in univariate analyses, female participants (Odds Ratio (OR) = 0.62 [95% CI: 0.44–0.87]), individuals of Aboriginal ancestry (OR = 0.71 [95% CI: 0.51–0.99]), as well as daily cocaine injection (OR = 0.37 [95% CI: 0.24–0.56]), daily heroin injection (OR = 0.64 [95% CI: 0.42–0.97]) and baseline CD4 count (OR = 0.89 [95% CI: 0.81–0.97]) were associated with lower adherence to ART.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic, behavioural and clinical characteristics of 682 ACCESS participants stratified by at least 95% adherence to ART in first year

| Characteristic | < 95% adherence 450 (66.0%) | ≥95% adherence 232 (34.0%) | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ART initiation year | |||||

| Per year increase | 1999 (1997–2004) | 2003 (1998–2007) | 1.13 | 1.09–1.17 | < 0.001 |

| Gender1 | |||||

| Male | 270 (60.0) | 164 (70.7) | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 180 (40.0) | 68 (29.3) | 0.62 | 0.44–0.87 | 0.006 |

| Age1 | |||||

| < 24 years | 21 (4.7) | 3 (1.3) | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ 24 years | 429 (95.3) | 229 (98.7) | 3.74 | 1.10–12.66 | 0.034 |

| Aboriginal ancestry1 | |||||

| No | 278 (61.8) | 161 (69.4) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 172 (38.2) | 71 (30.6) | 0.71 | 0.51–0.99 | 0.050 |

| Heroin use2 | |||||

| < Daily | 347 (77.1) | 195 (84.1) | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ Daily | 103 (22.9) | 37 (15.9) | 0.64 | 0.42–0.97 | 0.034 |

| Cocaine use2 | |||||

| < Daily | 320 (71.1) | 202 (87.1) | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ Daily | 130 (28.9) | 30 (12.9) | 0.37 | 0.24–0.56 | < 0.001 |

| Crack cocaine use2 | |||||

| < Daily | 321 (71.3) | 172 (74.1) | 1.00 | ||

| ≥ Daily | 129 (28.7) | 60 (25.9) | 0.88 | 0.61–1.26 | 0.475 |

| Methadone use3 | |||||

| No | 276 (61.3) | 150 (64.7) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 174 (38.7) | 82 (35.3) | 0.87 | 0.62–1.21 | 0.396 |

| Unstable housing3 | |||||

| No | 155 (34.4) | 78 (33.6) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 295 (65.6) | 154 (66.4) | 1.04 | 0.74–1.45 | 0.830 |

| Plasma HIV RNA load | |||||

| Per log10 increase | 4.9 (4.4–5.1) | 4.9 (4.4–5.0) | 0.91 | 0.72–1.15 | 0.426 |

| CD4+ cell count | |||||

| Per 100 cells | 2.4 (1.4–3.7) | 1.9 (1.2–3.0) | 0.89 | 0.81–0.97 | 0.008 |

Time-varying, refers to the six month period prior to baseline

Time-varying, refers to current status

In the multivariate model, initiation year was significantly associated with the likelihood of achieving 95% adherence (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 1.08 [95% CI: 1.03–1.13] per year since 1996) after adjustment for female gender, Aboriginal ancestry, age at baseline, frequent cocaine use, frequent heroin use, receiving treatment for illicit drug or alcohol use and baseline CD4+ cell count.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, adherence to ART during the first year increased significantly from 19.3% in 1996 to 65.9% in 2009 among a community recruited cohort of HIV positive injection drug users. This trend remained significant even after adjustment for time-updated potential confounders including clinical variables, drug use patterns and use of addiction treatment. We also found that adherence among patients with lower CD4 counts increased, which may be related to increased symptoms experienced among participants with lower CD4 counts.

Many studies have found that injection drug use is associated with reduced adherence of ART (30–32). One meta-analysis demonstrated that studies with a lower proportion of IDU are more likely to report a greater proportion of study subjects who are ≥90% adherent to ART (33). However, Malta et al. recently demonstrated that IDU tend to be inappropriately assumed to be less adherent (34). Our study provides evidence to support improved adherence during the first year of ART among IDUs in recent years. Adherence among IDU likely increased due to a variety of variables including decreased toxicity with more modern ART regimens and decreased pill burden with simplified once-daily therapy (35–37).

Our study has some limitations. First, as no registries of IDU exist, recruiting a random sample of HIV-seropositive IDU is not possible. However, we used community-based techniques to recruit a range of HIV-seropositive IDU both in and out of clinical care. Second, our outcome of interest was based on pharmacy refill activity and might not perfectly reflect daily medication adherence. However, this measure has been used extensively in previous analyses and has been shown to robustly predict both virologic response and survival (19, 23, 38, 39).

In the present study, adherence to ART during the first year increased significantly over time among a community-recruited cohort of HIV positive injection drug users. This trend remained significant even after adjustment for time-updated measures of potential confounders including clinical variables, drug use patterns and use of addiction treatment. IDU in our cohort received free ART with integrated services which has been shown to improve adherence among HIV-positive IDU and our study demonstrates that this trend increased over time (40). Although improved tolerability and convenience of modern ART regimens likely explain these positive trends, by the end of the study period a substantial proportion of IDU still had sub-optimal adherence demonstrating the need additional adherence support strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff. We would specifically like to thank Deborah Graham, Tricia Collingham, Carmen Rock, Brandon Marshall, Caitlin Johnston, Steve Kain, Benita Yip, and Calvin Lai for their research and administrative assistance.

Role of Funding Source: The study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA021525) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-79297, RAA-79918). Drs. Kerr and Milloy are supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. None of the aforementioned organizations had any further role in study design, the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Statement: Dr. Montaner has received educational grants from, served as an ad hoc advisor to or spoken at various events sponsored by Abbott Laboratories, Agouron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., Borean Pharma AS, Bristol – Myers Squibb, DuPont Pharma, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann – La Roche, Immune Response Corporation, Incyte, Janssen – Ortho Inc., Kucera Pharmaceutical Company, Merck Frosst Laboratories, Pfizer Canada Inc., Sanofi Pasteur, Shire Biochem Inc., Tibotec Pharmaceuticals Ltd. and Trimeris Inc.

References

- 1.Hammer SM, Katzenstein DA, Hughes MD, et al. A Trial Comparing Nucleoside Monotherapy with Combination Therapy in HIV-Infected Adults with CD4 Cell Counts from 200 to 500 per Cubic Millimeter. NEJM. 1996;335:1081–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610103351501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer SM, Squires KE, Hughes MD, et al. A Controlled Trial of Two Nucleoside Analogues plus Indinavir in Persons with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and CD4 Cell Counts of 200 per Cubic Millimeter or Less. NEJM. 1997;337:725. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood E, Montaner JSG, Tyndall MW, Schechter MT, O'Shaughnessy MV, Hogg RS. Prevalence and Correlates of Untreated Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Infection among Persons Who Have Died in the Era of Modern Antiretroviral Therapy. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1164–70. doi: 10.1086/378703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce RD, Altice FL. Clinical care of the HIV-infected drug user. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:149–79. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karon JM, Fleming PL, Steketee RW, De Cock KM. HIV in the United States at the turn of the Century: an epidemic in transition. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1060–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathers B, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008;372:1733–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paterson DL, Sindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to Protease Inhibitor Therapy and Outcomes in Patients with HIV Infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deeks SG. Treatment of antiretroviral-drug-resistant HIV-1 infection. Lancet. 2003;362:2002–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein MD, Rich JD, Maksad J, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected methadone patients: effect of ongoing illicit drug use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2000;26:195–205. doi: 10.1081/ada-100100600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerr T, Palepu A, Barness G, et al. Psychosocial determinants of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users in Vancouver. AVT. 2004;9:407–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, Longshore D, Williams JK, et al. Substance Abuse and Medication Adherence Among HIV-Positive Women with Histories of Child Sexual Abuse. AIDS & Behavior. 2006;10:279–86. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9041-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnsten JH, Li X, Mizuno Y, et al. Factors associated with antiretroviral therapy adherence and medication errors among HIV-infected injection drug users. JAIDS. 2007;46 (Suppl 2):S64–S71. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815767d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrieri MP, Chesney MA, Spire B, et al. Failure to maintain adherence to HAART in a cohort of French HIV-positive injecting drug users. IJBM. 2003;10:1–14. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1001_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordillo V, del Amo J, Soriano V, Gonzalez-Lahoz J. Sociodemographic and psychological variables influencing adherence to antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 1999;13:1763–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199909100-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Joy R, et al. Antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes among HIV/HCV co-infected injection drug users: The role of methadone maintenance therapy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;84:188–94. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PGA, et al. Barriers to Use of Free Antiretroviral Therapy in Injection Drug Users. JAMA. 1998;280:547–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hogg RS, Heath K, Bangsberg D, et al. Intermittent use of triple combination therapy is predictive of mortality at baseline and after one year of follow-up. AIDS. 2002;16:1051–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.d'ArminioMonforte A, Lepri AC, Rezza G, et al. Insights into the reasons for discontinuation of the first highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) regimen in a cohort of antiretroviral naive patients. I.CO.N.A. Study Group. Italian Cohort of Antiretroviral-Naive Patients. AIDS. 2000;14:499–507. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003310-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood E, Montaner JSG, Yip B, et al. Adherence and plasma HIV RNA responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-1 infected injection drug users. CMAJ. 2003;169:656–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palepu A, Yip B, Miller C, et al. Factors associated with the response to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected patietns with and without a history of injection drug use. AIDS. 2001;15:423–4. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200102160-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Low-Beer S, Yip B, O'Shaughnessy MV, Hogg RS, Montaner JS. Adherence to triple therapy and viral load response. JAIDS. 2000;23:360–1. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200004010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, Harrigan PR, O'Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JSG. Effect of Medication Adherence on Survival of HIV-Infected Adults Who Start Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy When the CD4+ Cell Count Is 0.200 to 0.350×10[9] cells/L. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:810–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood E, Hogg RS, Lima VD, et al. Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy and Survival in HIV-Infected Injection Drug Users. JAMA. 2008;300:550–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogg RS, Heath K, Bangsberg D, et al. Intermittent use of triple-combination therapy is predictive of mortality at baseline and after 1 year of follow-up. AIDS. 2002;16:1051–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO. World Health Organization, Child and Adolescent Health. Vol. 2011. South-East Asia: WHO; [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, Harrigan PR, O'Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS. Effect of medication adherence on survival of HIV-infected adults who start highly active antiretroviral therapy when the CD4+ cell count is 0.200 to 0.350 x 10(9) cells/L. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:810–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maldonado G, Grenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138:923–36. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lima V, Fernandes K, Rachlis B, Druyts E, Montaner J, Hogg R. Migration adversely affects antiretroviral adherence in a population-based cohort of HIV/AIDS patients. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1044–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milloy M-J, Kerr T, Buxton J, et al. Dose-response effect of incarceration events on nonadherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1215–21. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bouhnik A-D, Chesney M, Carrieri P, et al. Nonadherence among HIV-infected injecting drug users: the impact of social instability. JAIDS. 2002;31:S149–S53. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200212153-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Celentano DD, Vlahov D, Cohn S, Shadle VM, Olugbenga O, Moore RD. Self-reported antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users. JAMA. 1998;280:544–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.6.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chesney MA. Factors affecting adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;2000:S171–S6. doi: 10.1086/313849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ortego C, Huedo-Medina T, Llorca J, et al. Adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART): a meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1381–96. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9942-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malta M, Magnanini MM, Strathdee SA, Bastos FI. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected drug users: a meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:731–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9489-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nachega JB, Mugavero MJ, Zeier M, Vitoria M, Gallant JE. Treatment simplifciation in HIV-infected adults as a strategy to prevent toxicity, improve adherence, quality of life and decrease healthcare costs. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2011;5:357–67. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S22771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atkinson MJ, Petrozzino JJ. An evidence-based review of treatment-related determinants of patients' nonadherence to HIV medications. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:903–14. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Portsmouth SD, Osorio J, McCormick K, Gazzard BG, Moyle GJ. Better maintained adherence on switchign from twice-daily to once-daily therapy for HIV: a 24-week randomized trial of treatment simplification using stavudine prolonged-release capsules. HIV Med. 2005;6:185–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2005.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krusi A, Milloy M-J, Kerr T, et al. Ongoing drug use and outcomes from highly active antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users in a Canadian setting. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:789–96. doi: 10.3851/IMP1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Low-Beer S, Yip B, O'Shaughnessy MV, Hogg RS, Montaner JSG. Adherence to triple therapy and viral load response. JAIDS. 2000;23:360–1. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200004010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malta M, Strathdee SA, Magnanini MM, Bastos FI. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome among drug users: a systematic review. Addiction. 2008;103:1242–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palepu A, Milloy M-J, Kerr T, Zhang R, Wood E. Homelessness and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among a cohort of HIV-infected injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2011;88:545–55. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9562-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tapp C, Milloy M-J, Kerr T, et al. Female gender predicts lower access and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a setting of free healthcare. BMC Infec Dis. 2011;11 doi: 10.1186/147-2334-11-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]