Abstract

We investigate the density of non-contract (private) physicians in a two-tiered health care system, i.e., one with co-existing public and private health care providers. In particular, we analyze how the densities of private and public suppliers of outpatient health care (general practitioners and specialists) are related to each other. Using a panel of 121 Austrian districts between 2002 and 2008, we apply a Hausman–Taylor estimator, which allows to treat each of these densities as endogenous. We find that the density of non-contract specialists is positively associated with the density of non-contract general practitioners, but not significantly related to the density of contract general practitioners. We also observe a negative relationship between the densities of non-contract and contract general practitioners and the ones of non-contract and contract specialists, indicating competitive forces between the private and the public sector of the outpatient health care provision in Austria. Our results contribute to the ongoing debate on the role of non-contract physicians for health care provision in Austria.

Keywords: Competition in health care markets, Physician location, Panel econometrics

1. Introduction

In many countries, disparities in the distribution of health care capacities are a major concern for health care policy at least for two reasons. First, health care services are typically associated with categorical goods, implying the often held claim that every citizen should have equal access to an agreed minimum standard of health care. Second, a maldistribution of health care capacities may cause inefficiencies. In particular, an over-provision of health care capacities in socioeconomic attractive areas might lead to supplier induced demand [17]. Concerns about such disparities apply to nearly all facilities of health care provision, and especially to outpatient care. There is a vivid and ongoing discussion in health sciences, particularly in health economics, whether market based physician location policies cause the mentioned maldistribution, and to which extent the state should regulate or stipulate entry to regional physician markets (see, e.g., [5,12,13,15,16,29–31,33,36]).

There are two broad lines of research explaining spatial differences in physician densities. The first strand of literature primarily focuses on the individual location decision. The ‘prior contact theory’, for instance, stresses that physicians are more likely to practice near and in locations where they received their medical education or hold an affiliation to a hospital (see, e.g., [14,24]). Other authors, focusing on interviews of physicians, emphasize that individual characteristics of physicians, such as the family background, play a decisive role in the decision where to locate a practice (see, e.g., [22,25–28]). Further, there is an eminent line of research in industrial organization focusing on the individual market entry and exit decisions of physicians and its impact on competition in the health care sector (see, e.g., [1,7–10,35]).

The second line of research addresses directly the spatial distribution of physician densities and tries to identify factors explaining differences in the physician workforce over urban and rural areas. Obviously, physician densities reflect not only entry decisions but also migration and market exits of physicians. The resulting disparities are typically explained by demand-driven factors, like a region's demographic, socioeconomic and technological background, as well as the specific characteristics of a region's health care system (i.e., the availability of health care facilities acting as substitutes or complements to the outpatient physician workforce), including the corresponding legal environment which is important for a patient's access to health care (e.g., differences in cost sharing schedules between regions). This translates into a (reduced form) framework where the physician density at a given location is regressed on a set of a region's demographic, geographical, socioeconomic and institutional variables (see, e.g., [6,23,30,31]).

This paper contributes to the research on regional disparities in physician density and is, thereby, related to the second strand of literature mentioned above. Rather than treating the physician workforce as a homogeneous group, as in previous papers on this field of research, we focus on location decisions of physicians acting in two-tiered health care systems. For this purpose, we refer to the Austrian health care system, where physicians with and without a contract with the public social insurance system co-exist (henceforth, we refer to the former ones as contract and to the latter ones as non-contract physicians). While market entry for contract physicians is strongly regulated by public agencies, non-contract physicians are free to choose a location. They are also less restricted in pricing policies and service provision. For these reasons, we restrict our attention to the location decisions of non-contract physicians. Further, we distinguish between general practitioners (GPs) and specialists (SPs), leaving with four different types of physicians: non-contract and contract general practitioners (PGPs and CGPs) as well as non-contract and contract specialists (PSPs and CSPs). To study how the corresponding physician densities are related to each other, we exploit information from 121 Austrian districts over the time period 2002–2008. We estimate the local density of one type of non-contract physicians (PGPs or PSPs) as a function of the densities of contract physicians (CGPs and CSPs) and the remaining density of non-contract physicians, among other factors such as a region's hospital facilities, educational level or aggregate income. This, in turn, allows to draw conclusions about the existence and intensity of competition between these types of physicians in a two-tiered health care system. Our results generally suggest competitive forces between contract and non-contract physicians, which, together with the observation that the number of non-contract physicians increased sharply relative to the one of contract physicians in recent years, might also contribute to the ongoing debate about the role of non-contract physicians for health care provision in Austria.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the institutional background of the Austrian health care system, giving particular emphasis on health care provision of non-contract and contract physicians. From this, we elaborate three testable hypotheses regarding the relationship between non-contract and contract physicians. Section 3 provides a brief overview over the data, works out the econometric framework to analyze interrelations between densities of different types of physicians, and discusses our empirical findings. Finally, Section 4 concludes.

2. Institutional background and main hypotheses

From a demand and financing perspective, the public health insurance system represents the first tier of outpatient care in the Austrian health care system. Membership in this system is obligatory not only for wage earners in the public and the private sector, but also for self-employed persons (including farmers). Individuals with family ties to obligatory insured persons and without own coverage obtain free health coverage. Overall, the public health insurance covers around 98.5 percent of the whole population, excluding only marginal groups from public health insurance. It is mainly financed by income related contributions. Private health insurance and out-of-pocket payments constitute the second tier of the Austrian health care system. Roughly 35 percent of the population has signed contracts with private sickness funds, which predominantly offer additional coverage to the first tier services and/or improve the possibility to choose a provider within the system.

Health care services are supplied by contracted physicians and by their non-contracted counterparts. Both groups are self-employed and are mainly working in single practices (see [21, p. 118]). The spatial distribution of contract physicians is based on a location plan agreed between the public health insurance system and the Chamber of Physicians. It specifies the regional distribution of the physician workforce derived from the basic health needs of the relevant population. It also has to ensure a sufficient provision of medical services based on the existing state of medical standards. A contract physician's contract relies on bilateral agreements negotiated between the relevant (regional or federal) Chamber of Physicians and the Federal Association of Social Security Institutions on behalf of the sickness funds. It determines important dimensions of physician services, such as the practice style (e.g., office hours, treatment guidelines or restrictions of additional occupations) or the physician payment scheme. The assignment of a contract is based on criteria like waiting time or professional experience. Once concluded, the contract is not limited in time.

Contract physicians generate income from fee-for-service and lump-sum payments. The latter can be claimed for initial contacts and for the provision of basic services. The share of lump-sum payments to total physician earnings varies widely over different fields of specialization. At an aggregate level, it amounts to about 68 percent for CGPs and around 34 percent for CSPs [37]. The fee-for-service component of remuneration includes earning caps, inducing decreasing marginal revenues per patient and treatment. Contract physicians are also allowed to earn extra money by providing additional services beyond the contract (e.g., school services). The scale of these activities, however, is strictly regulated by the physician contract (e.g., via upper limits of working time in such occupations).

In contrast to contract physicians, their private counterparts are free to choose their practice location. Their remuneration is mainly based on a fee-for-service system. The corresponding fees are agreed between the physician and the patients, albeit there exists a recommendation for the physician pricing policy by the Chamber of Physicians. Further, they are allowed to earn extra money without any restrictions (e.g., by working in a private or public hospital).

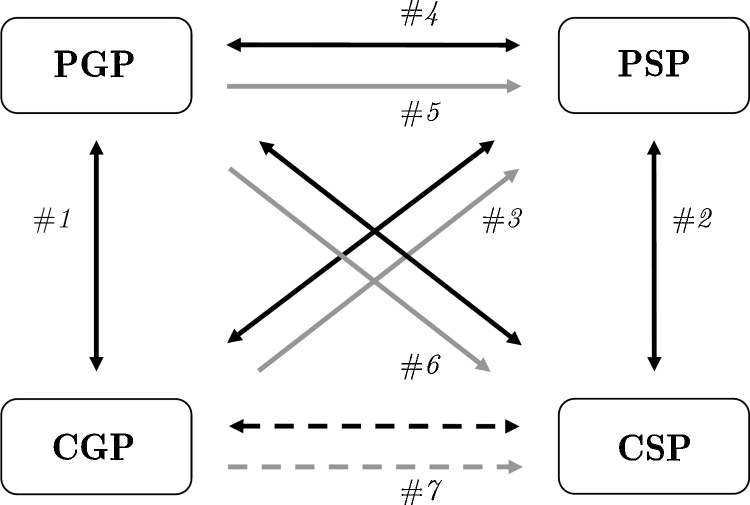

Patients with public health insurance coverage are basically free to consult a contract or a non-contract physician,1 but the incurred costs are considerably different. While the utilization of public outpatient health care is based on a benefit-in-kind scheme with only negligible cost-sharing elements,2 treatment costs in the private sector (i) have to be paid out-of-pocket, (ii) are born by the private health insurances, and/or (iii) by the public health insurance. The latter only reimburses parts of a non-contract physician's invoice. The maximum amount refunded is fixed at 80 percent of the amount a contract physician would receive, but only if the non-contract physician's services are included in the public benefit catalogue. Further, since prices of such services are usually well above the ones of contract physicians, the cost sharing rate is much higher than 20 percent in most cases.3 Therefore, we would expect that services of non-contract physicians are only demanded if the additional costs are at least covered by the expected benefits (e.g., shorter waiting times or higher treatment quality; see [32], for a more general approach on private health care demand; Samhaber [34] provides empirical evidence from Austria on different motives to contact non-contract physicians). In this case, contract and non-contract physicians are competing for more or less the same population of patients, especially when providing very similar health services. Consequently, services of non-contract and contract physicians can be viewed as substitutes, suggesting a negative relationship between the corresponding physician densities (in the following, we refer to this as ‘competition effect’). This competitive relationship between physicians is summarized in the solid dark arrows of Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Competition and referral between non-contract and contract physicians. Notes: Competition between physicians is represented by the dark arrows, referrals from one type of physicians to other ones are indicated by the gray shaded arrows. Dashed arrows indicate relationships between physicians that are not addressed in the empirical analysis below.

The competition effect implies that non-contract and contract physicians of the same type provide substitutive services, so that we would expect that PSPs and PGPs tend to avoid markets with a higher number of CSPs and CGPs, respectively. This is captured in #1 and #2 of Fig. 1. Our first hypothesis with regard to the relationship between non-contract and contract physicians is as follows:

Hypothesis 1

The density of PGPs (PSPs) should be negatively related to the density of CGPs (CSPs).

On the other hand, patients typically use to visit a CGP first when demanding health care services.4 Therefore, CGPs are able to influence patient flows to other physicians via their referral behavior, indicated as gray shaded arrows in Fig. 1. Although referrals are not obligatory, they enable contract physicians to alleviate treatment maximizing strategies intended to compensate for decreasing returns per patient and treatment, resulting from the above mentioned remuneration scheme. From this, it is generally plausible to assume a positive relationship between the density of CGPs and PSPs (henceforth ‘referral effect’, #3 in Fig. 1). It should be noticed, however, that referrals from the public to the private sector are rather unusual in Austria. CGPs usually refer to CSPs (#7 in the figure), and thus, we do not expect that PSPs benefit strongly from a CGP located in the same area.5 Therefore, we are able to derive a second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

Since PSPs and CGPs partly provide the same services and referrals from the public to the private sector are uncommon, the density of PSPs should be negatively associated with the density of CGPs.

By way of contrast, the referral effect should be stronger for PGPs if treatments are cumbersome or time consuming [35]. Then, the density of PSPs would be higher in locations with a higher PGP density, and vice versa (i.e., PGPs benefit from presence of PSPs as they create referral opportunities, see #5 in Fig. 1).6 Further, non-contract physicians are more exposed to competition as they are not ‘protected’ by a physician location plan. Baumgardner [4] has shown that physicians tend to cooperate or build up networks under such conditions, which might be especially the case between non-contract GPs and SPs. Although the substitutive effect might also play a role between PGPs and PSPs (#4 in the figure), we would presume that it is outweighed by a relatively strong impact of referral and network effects. This leads to our final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

Due to referrals, the density of PSPs should be positively related to the density of PGPs. Further, since PGPs benefit from cooperation with PSPs if treatments are cumbersome or time consuming, the impact of PSP density on the density of PGPs should be positive.

Notice that also CSPs benefit from referrals of CGPs (#7 in Fig. 1) and, to a lesser extent, of PGPs (arrow #6). However, as the location of contract physicians follows a fixed location plan by the Austrian public health insurance, it is reasonable to assume that the densities of CGPs and CSPs are not seriously influenced by private resources of outpatient health care. After all, our description of the Austrian health care system shows that the density of each particular type of physicians is affected by the density of the other types of physicians. Below, we propose a specific empirical framework to address these interrelations.

3. Empirical analysis

3.1. Data and descriptives

To test the above mentioned interrelations among non-contract and contract physicians empirically, we employ a data set from 121 Austrian districts between 2002 and 2008.7 Data from physicians and their specialties are available from Göschl CD MED, Handbuch für die Sanitätsberufe Österreichs (years 2002–2008). As shown in Table 1, our sample includes 14,569 (non-contract and contract) physicians, on average. Over the whole sample period, about 56 percent of all self-employed physicians have signed a contract with the public health insurance system, approximately 48 percent of them are CSPs. The share of PSPs is somewhat higher (around 70 percent) in the group of non-contract physicians. Further, we can see a substantial increase (about 27 percent) in non-contract physicians over the course of the years, which is the result of increased medical graduates and stable capacity plans for contract physicians. Finally, we also observe enough variation for the number of non-contract physicians over time (the average annual change is around five percent for non-contract physicians, but much lower for contract physicians), rendering panel data (fixed effects) estimation possible.

Table 1.

Non-contract and contract physicians in Austria.

| Year | Number of physicians |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSP | PGP | CSP | CGP | Sum | |

| 2002 | 3675 | 1560 | 3940 | 4289 | 13,464 |

| 2003 | 4013 | 1730 | 3924 | 4258 | 13,925 |

| 2004 | 4200 | 1792 | 3925 | 4261 | 14,178 |

| 2005 | 4612 | 2015 | 3932 | 4246 | 14,805 |

| 2006 | 4875 | 2046 | 3925 | 4217 | 15,063 |

| 2007 | 5025 | 2088 | 3918 | 4194 | 15,225 |

| 2008 | 5139 | 2115 | 3896 | 4165 | 15,315 |

| Average | 4506 | 1907 | 3923 | 4233 | 14,569 |

| Change 2002–2008 (in percent) | 28.49 | 26.24 | −1.12 | −2.98 | 12.09 |

| Average annual change (in percent) | 5.79 | 5.30 | −0.19 | −0.49 | 2.18 |

PSP, non-contract specialist; PGP, non-contract general practitioner; CSP, contract specialist; CGP, contract general practitioner.

Based on the physicians’ locations, we are able to calculate the number of physicians per district and specialty. In addition, we use information on regional supply and demand for health services, in our case a district's aggregate income, its average educational level (measured by an index between zero and five)8, living area capturing transport and time cost to consult a physician, and the facilities of private and public inpatient care as measured by a district's total number of beds in private and public hospitals (the corresponding data sources are listed in the Appendix).

Table 2 provides a descriptive overview of the dataset, including means, standard deviations as well as minimum and maximum values of our variables from the empirical analysis below. Overall, our sample includes 847 observations, i.e., 121 districts over seven years. On average, we observe 37 (around 32) PSPs (CSPs) in a district, with a minimum of zero (one) and a maximum of 275 (227) physicians. The corresponding figures for GPs are lower, with mean values of around 16 (PGPs) and 35 (CGPs). The block on the right-hand-side of Table 2 shows that the average density of PSPs, defined as the number of PSPs in a district over the population size in 1000 inhabitants, is 0.68. The maximum is around 10.1. For contract specialists, we observe a mean (maximum) value of 0.54 (4.39), and for CGPs we have a similar mean value of 0.53 (0.76). Only for PGPs we have a relatively small representation in our sample (see Table 1), translating in a much lower density of 0.27 (the maximum entry is 2.87).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics (847 observations).

| Variable | Absolute number |

Densitiesc |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. dev. | Min. | Max. | Mean | Std. dev. | Min. | Max. | |

| Number of PSP | 37.24 | 47.46 | 0.00 | 274.00 | 0.68 | 1.16 | 0.00 | 10.14 |

| Number of PGP | 15.75 | 15.05 | 0.00 | 93.00 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.00 | 2.87 |

| Number of CSP | 32.42 | 33.13 | 0.00 | 227.00 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 4.39 |

| Number of CGP | 34.98 | 20.58 | 1.00 | 161.00 | 0.53 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.76 |

| Private hospital bedsa | 1.23 | 2.11 | 0.00 | 15.72 | 1.77 | 2.63 | 0.00 | 13.38 |

| Public hospital bedsa | 4.00 | 5.77 | 0.00 | 36.05 | 6.11 | 7.77 | 0.00 | 53.87 |

| Average incomeb | 17.41 | 2.23 | 14.70 | 28.51 | – | – | – | – |

| Education | 1.70 | 0.25 | 1.43 | 2.65 | – | – | – | – |

| Living area (100 km2) | 2.69 | 2.37 | 0.01 | 11.09 | – | – | – | – |

Number of hospital beds in a district, in 100.

Income in 1000 Euro per person.

Calculated as the total number of physicians/hospital beds in a district over 1000 inhabitants.

PSP, non-contract specialist; PGP, non-contract general practitioner; CSP, contract specialist; CGP, contract general practitioner.

Average annual income (net of taxes), measured by a district's total income to population size, amounts to about 17,400 Euro (the minimum is about 14,700 Euro and the maximum amounts to 28,500 Euro). The largest district in our sample is around 1100 km2, with an average value of 270 km2. Further, we observe an average of around 123 (400) hospital beds in the private (public) inpatient sector. The corresponding maxima lie around 1572 and 3605 beds.9

Table 3 summarizes the distribution of physicians over general practitioners and 14 specialties; the upper table block refers to the number of non-contract, and the lower one to the number of contract physicians within a district. For example, we can see that there are, on average, about 16 GPs within a district; the corresponding maximum is 93. Within the group of non-contract physicians, the main specializations are represented by internists (around 22.5 percent of all specialists), surgeons (21.7 percent), neurologists (14.3 percent) and gynecologists (12.7 percent). These are also the largest specializations among contract physicians. There, our sample includes about 17.4 percent internists, 8.7 percent surgeons, 12.5 percent neurologists and 14.3 percent gynecologists. Looking at the maximum entries, we observe some specializations with rather low representations in both groups of physicians, which is especially the case for lung doctors, urologists, laboratory diagnostics and radiologists. In the empirical analysis below, we account for the composition of specializations by (i) analyzing the whole group of SPs and (ii) by focusing on specializations with relatively strong representations in our sample of non-contract physicians, i.e., internists, surgeons, neurologists and gynecologists.

Table 3.

Non-contract and contract physicians per specialty.

| Mean | Std. dev. | Min. | Max. | Hosp.a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-contract physicians | |||||

| General practitioners | 15.76 | 15.04 | 0 | 93 | 11.63 |

| Specialists | 37.24 | 47.46 | 0 | 274 | 51.37 |

| Ophthalmologists | 1.42 | 2.68 | 0 | 17 | 56.73 |

| Dermatologists | 1.47 | 2.51 | 0 | 16 | 43.50 |

| Gynecologists | 4.71 | 5.04 | 0 | 29 | 57.02 |

| Otolaryngologist | 1.13 | 1.88 | 0 | 14 | 63.19 |

| Pediatricians | 1.75 | 2.44 | 0 | 13 | 45.50 |

| Lung doctors | 0.46 | 1.03 | 0 | 7 | 60.00 |

| Neurologists | 5.33 | 8.07 | 0 | 41 | 45.41 |

| Orthopedists | 2.24 | 3.01 | 0 | 20 | 52.98 |

| Urologists | 0.96 | 1.56 | 0 | 8 | 53.72 |

| Laboratory diagnostics | 0.40 | 0.88 | 0 | 6 | 61.70 |

| Radiologists | 0.93 | 1.52 | 0 | 11 | 49.55 |

| Surgeons | 8.07 | 12.27 | 0 | 81 | 67.64 |

| Internists | 8.38 | 10.82 | 0 | 70 | 58.00 |

| Other specialists | 2.50 | 3.70 | 0 | 31 | 54.84 |

| Contract physicians | |||||

| General practitioners | 34.98 | 20.58 | 1 | 161 | 7.89 |

| Specialists | 32.42 | 33.13 | 0 | 227 | 19.66 |

| Ophthalmologists | 3.08 | 3.03 | 0 | 23 | 24.60 |

| Dermatologists | 2.32 | 2.47 | 0 | 17 | 26.41 |

| Gynecologists | 4.64 | 5.00 | 0 | 38 | 20.00 |

| Otolaryngologist | 2.03 | 2.14 | 0 | 16 | 40.73 |

| Pediatricians | 2.58 | 2.60 | 0 | 20 | 18.71 |

| Lung doctors | 1.25 | 1.46 | 0 | 10 | 18.95 |

| Neurologists | 4.04 | 4.21 | 0 | 32 | 37.30 |

| Orthopedists | 2.31 | 2.53 | 0 | 13 | 33.81 |

| Urologists | 3.53 | 3.63 | 0 | 21 | 36.47 |

| Laboratory diagnostics | 0.39 | 0.75 | 0 | 5 | 72.92 |

| Radiologists | 1.81 | 1.75 | 0 | 10 | 44.69 |

| Surgeons | 2.82 | 3.83 | 0 | 22 | 48.26 |

| Internists | 5.64 | 6.27 | 0 | 46 | 29.84 |

| Other specialists | 0.89 | 1.56 | 0 | 10 | 45.37 |

Share of physicians working in public and private hospitals.

The last column of Table 3 reports the share of physicians working in a public or private hospital in addition to the activities in their practices. In this regard, we can see that there are large differences between GPs and SPs on the one hand, and between non-contract and contract specialists on the other one. On average, more than 50 percent of all non-contract specialists take up such outside activities, a share that varies between 18 (pediatricians) and 68 percent (surgeons). Obviously, hospital facilities might be viewed as an opportunity to provide additional services and, therefore, a way to increase income. From this, we would expect that it is attractive to locate the practice near a hospital. In the empirical analysis below, we explicitly account for this reasoning using the number of hospital beds within a district as a control variable to explain physician density.

Table 4 describes how (non-contract and contract) SPs and GPs are distributed over the Austrian districts. For example, we can see that there are seven districts in Austria with less than five PSPs located within the district. The lion's share of the Austrian districts sustain more than five and less than 25 non-contract physicians, especially in the group of PSPs. With regard to contract physicians, we observe the main group of representation in the classes of more than 5 and less than 25 and of more than 25 and less than 50 physicians. Generally, we have relatively few districts with a low representation in our sample, so that it seems enough variation over districts rendering regression analysis possible.

Table 4.

Number of physicians per district (year 2008).

| Number of physicians | PSP | PGP | CSP | CGP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 5 | 7 | 19 | 13 | 2 |

| More than 5 and less than 25 | 56 | 79 | 54 | 39 |

| More than 25 and less than 50 | 30 | 18 | 32 | 61 |

| More than 50 | 28 | 5 | 22 | 19 |

| Sum | 121 | 121 | 121 | 121 |

PSP, non-contract specialist; PGP, non-contract general practitioner; CSP, contract specialist; CGP, contract general practitioner.

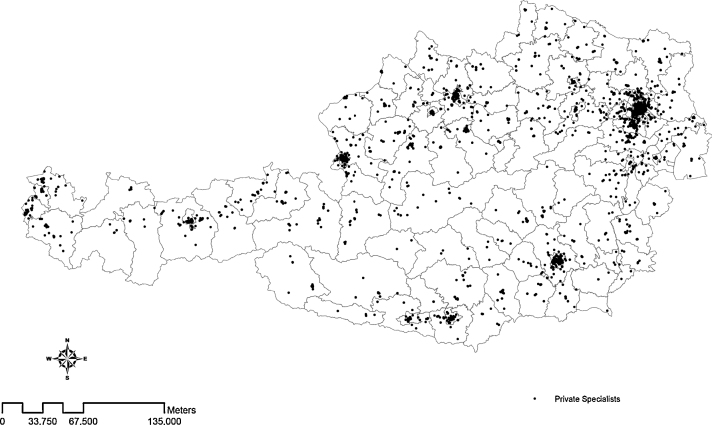

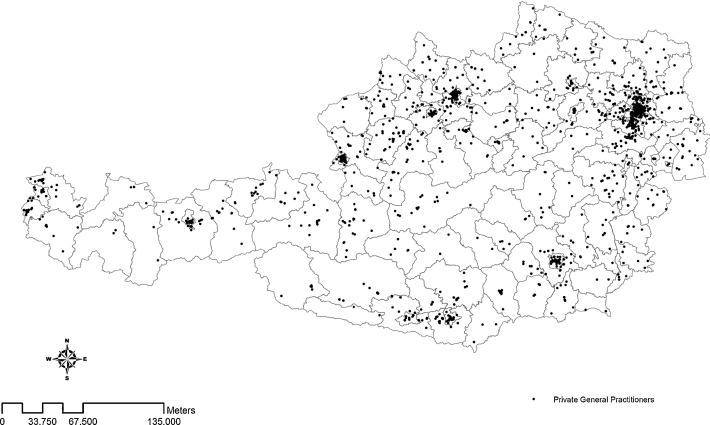

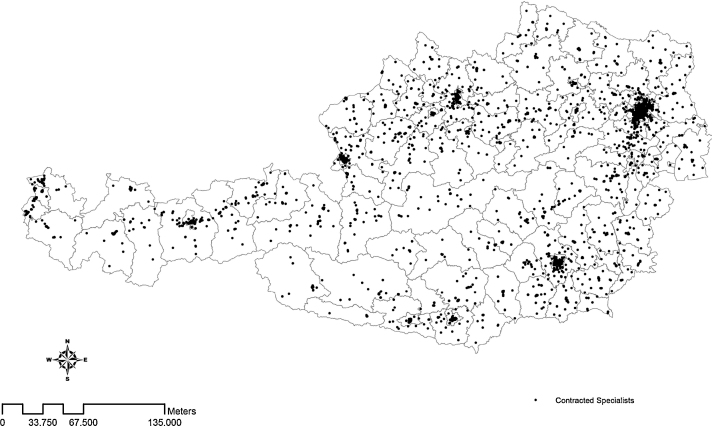

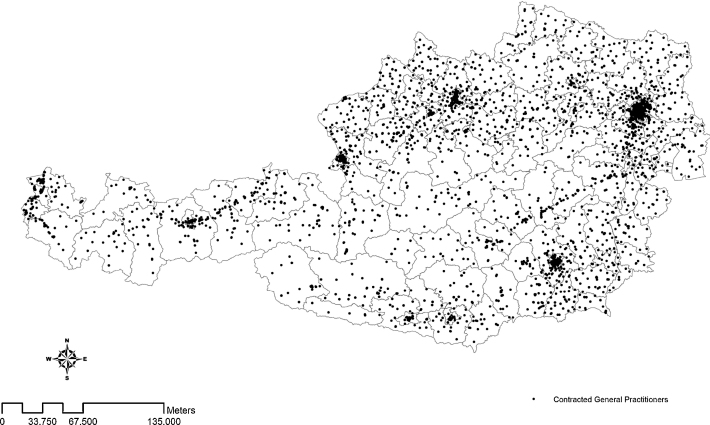

Finally, we provide four figures in Appendix depicting the spatial distribution of PSPs (Fig. 2), PGPs (Fig. 3), CSPs (Fig. 4) and CGPs (Fig. 5), where the borders represent the districts as our observational units (all entries in the figures relate to 2005). Each entry in these figures indicates a physician's location. Comparing the figures for (non-contract and contract) SPs with the ones of GPs we can see that the former are more located in agglomerations (i.e., the larger cities), while the latter are more uniformly distributed over both rural and urban areas. This pattern is less pronounced for non-contract physicians.

Fig. 2.

Spatial distribution of non-contract specialists.

Fig. 3.

Spatial distribution of non-contract general practitioners.

Fig. 4.

Spatial distribution of contract specialists.

Fig. 5.

Spatial distribution of contract general practitioners.

3.2. Specification and estimation

We are interested to explain the densities of (i) PSPs and (ii) PGPs as a function of (contract and the remaining non-contract) physicians and other demand- and supply-related covariates of a district. Our sample includes 121 Austrian districts over seven years, so that we can rely on a balanced panel. We estimate two separate regressions, which read as

| (1) |

| (2) |

where i indicates the ith district, i = 1, …, n. t is a time index, t = 1, …, T. PSP, CSP, PGP and CGP represent time-variant densities of non-contract and contract specialists as well as non-contract and contract general practitioners. As mentioned above, physician density is measured as the number of a group of physicians within a district per 1000 inhabitants. Xi contains a matrix of independent variables including a district's availability of hospital beds in the public and private sector, average income, an index of its educational level (see footnote 8), and living area. Living area and the number of beds in private and public hospitals are time invariant as well as all of the remaining variables in X as they refer to the year 2001 (the year where the actual population census has been carried out). λi and μi represent unobserved i-specific effects, νit and ɛit are idiosyncratic error terms.

From the discussion of Fig. 1 it is obvious that the right-hand-side densities of non-contract physicians are probably endogenous. Further, we should also account for endogeneity of (time-invariant) density of hospital beds in the private sector. For instance, it might be true that the PSP density in Eq. (1) is influenced by a district's PGP density, but causation might also run in the opposite direction if the presence of PSPs raises a district's attractiveness for PGPs due to increased referral opportunities. Similarly, it is reasonable that private hospitals are located in areas where the availability of non-contract physicians is high. Such endogeneity issues also apply to Eq. (2). We assume that these interrelations are i-specific, so that the density of PGPs is correlated with λi in Eq. (1) and orthogonal to νit, and the one of PSPs is correlated with μi and orthogonal to ɛit in Eq. (2). Further, we assume that the right-hand-side densities of both contract physicians and public hospital beds are exogenous, which might be justified by the fact that they are determined by the physician capacity and hospital plans.

Applying a fixed effects (FE) estimator under these conditions would remove the time invariant Xi-variables, but still provides consistent estimates of α1 and β1 as well as of α2, α3, β2 and β3 (see, e.g., [18, p. 337]). To estimate the parameters δ and γ, we apply a random effects model as developed by Hausman and Taylor [19]. They propose to assess the effects of time-invariant variables in panels by generalized least squares (GLS) applying an instrumental variable estimator to treat possibly endogenous regressors. In our case, this approach is useful to address the potential endogeneity of the right-hand-side densities of non-contract physicians and private hospital beds. Basically, the HT-estimator starts with the consistent FE-estimates, takes the within residuals of this regression, say , and, in a second step, regresses on Xi using the time-variant exogenous variables as instruments (in our case, the densities of contract physicians). From this, we obtain estimates of and , which, along with the estimates of the αs and βs from the within regression, can be used to estimate the variance components () and () in Eq. (1) [Eq. (2)]. The estimated variance components can be used to apply a GLS transformation on each variable in the model.10 Denoting the GLS transform of each variable with ‘*’, we finally obtain the HT-estimator from the regressions

| (3) |

using the within average , and the level of the time-invariant but exogenous Xi-variables as instruments, where y ∈ {PGP, CSP, CGP}. Similarly, the HT-estimator of Eq. (2) is exploited from

| (4) |

using , and the level of the time-invariant but exogenous Xi-variables as instruments, where z ∈ {PSP, CSP, CGP}. According to Amemiya and MaCurdy [2], we further assume that λi (μi) are uncorrelated with the right-hand-side variables in Eq. (1) [Eq. (2)], imposing a stricter requirement on the instruments than the original HT-estimator.

To test the HT-model against its FE counterpart we apply a Sargan test on over-identification [20, p. 227]. The corresponding test statistic is distributed as χ2 with T times the number of exogenous time-varying variables minus the number of endogenous time-invariant variables as degrees of freedom. If the test statistic is insignificant, the model is consistent and more efficient than its fixed effects counterpart. If not, one should prefer the FE-estimates. Finally, we take the logarithm of all variables in our empirical models to account for the fact that especially the dependent variables (densities of PSPs and PGPs) are not normally distributed but log-normally. We further tested the linear against the logarithmic model applying a J-test as proposed by Davidson and MacKinnon [11], indicating that the logarithmic specification outperforms the one without logarithms.11

3.3. Estimation results

Table 5 summarizes our estimation results. The Sargan test in the last line of the table is insignificant for both specifications, indicating that our instruments are valid and, therefore, the HT-estimates should be preferred over the ones of the FE-model (not reported in the table). With regard to the time-invariant covariates, we observe insignificant effects of private hospital beds, which might be explained by the fact that this variable is not varying over time and not much over districts. The density of public hospital beds is significantly positive for PSPs and significantly negative for PGPs, suggesting that PSPs (PGPs) tend to seek (avoid) markets with public inpatient facilities. One explanation might be that services of specialists are typically close substitutes to the one of inpatient facilities (and especially their outdoor ambulances), which is not necessarily the case for GPs. Education enters positively, but is insignificant in the PGP equation. Income and living area exhibit insignificant effects in both the PSP and PGP equations. Generally, one should interpret the corresponding (negative and positive) parameter estimates cautiously as there is a close correlation between both variables.

Table 5.

Estimation results.

| PSP | PGP | |

|---|---|---|

| Density of PSP | – | 0.371*** |

| (0.038) | ||

| Density of PGP | 0.679*** | – |

| (0.118) | ||

| Density of CSP | −0.036 | −0.060 |

| (0.167) | (0.091) | |

| Density of CGP | −0.376 | −0.396*** |

| (0.254) | (0.127) | |

| Density of private hospital bedsa | −0.017 | 0.003 |

| (0.077) | (0.025) | |

| Density of public hospital bedsa | 0.070*** | −0.022** |

| (0.026) | (0.010) | |

| Average incomea | 0.340 | −0.181 |

| (0.327) | (0.191) | |

| Educationa | 1.656** | 0.342 |

| (0.591) | (0.255) | |

| Living areaa | 0.010 | −0.011 |

| (0.028) | (0.012) | |

| Observations | 847 | 847 |

| R2 | 0.880 | 0.787 |

| Overidentification: χ2(13) | 13.953 | 10.727 |

| Endogenous regressor | PGP | PSP |

PSP, non-contract specialist; PGP, non-contract general practitioner; CSP, contract specialist; CGP, contract general practitioner. Bootstrapped standard errors in parentheses (50 replications).

Variables are time-invariant.

* Significance at 10 percent level.

Significance at 5 percent level.

Significance at 1 percent level.

Regarding our relationship of interest, we are not able to confirm the competition effect between CSPs and PSPs (Hypothesis 1), as the density of CSPs does not appear significant in the PSP equation. However, this might be due to the choice of the dependent variable, as the effects between different specialties might cancel out each other, leading to a non-significant coefficient for CPSs. For instance, it is reasonable that otolaryngologists or gynecologists do not compete with dermatologists in a region. Below, we account for this measurement issue distinguishing between different specialties in our regressions. In contrast, Hypothesis 1 is confirmed for PGPs, where we observe a significantly negative impact of CGP density, indicating a dominance of the competition effect over the referral effect.

With respect to Hypothesis 2, we find an insignificant negative impact of CGP density on the density of PSPs, indicating that the competition effect more or less compensates the referral effect for this type of physicians. Thus, CGPs appear to be substitutes rather than complements to non-contract specialists. One obvious explanation might be that CGPs act as profit maximizers and prefer longer treatment processes instead of referring to PSPs. As mentioned above, this is due to the institutional design of the Austrian health care system, where GPs are able to refer to a specialist when necessary, although it is not compulsory in most cases. Further, the negative coefficient might reflect that CGPs prefer CSPs rather than PSPs when referring to a specialist.

By way of contrast, we find support for referrals from PGPs to PSPs, entering positively in the PSP equation. This lend support to Hypothesis 3 as it seems that non-contract physicians (GPs and SPs) closely collaborate with each other and to some extent build up networks within their districts. Similarly, the coefficient of PSP density in the equation for PGPs is also positive and significant, implying a certain degree of network and cooperation effects, which might be the result of referrals among non-contract physicians (Hypothesis 3). Similar to the PSP equation, we find no significant relationship between the densities of CSPs and PGPs.

In sum, our estimation results from Table 5 might be interpreted that PSPs and PGPs tend to establish networks or cooperations within their districts. The density of CGPs enters significantly negative in the PGP-equation, indicating competition effects especially with PGPs and a relatively low importance of referrals to PSPs. For CSPs, we are not able to identify any significant effects on the densities of PGPs and PSPs. It should be noticed that the latter include a wide variety of very different specialities (see Table 3), which might explain the insignificant impact of CSPs, as discussed above. We account for this by re-estimating Eq. (2) separately for the four largest groups of specialities reported in Table 3 (i.e., internal specialists, surgeons, neurologists and gynecologists), including the corresponding densities of CSPs as the right-hand-side variable, among the other ones in Eq. (2). The estimation results from this exercise are reported in Table 6. Again, we rely on the HT-estimates, which can be justified by the insignificant Sargan test statistics reported in the bottom line of the table.

Table 6.

Estimation results for specific specializations.

| Variable | Physician density |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSPS | PSPN | PSPG | PSPI | |

| Density of PGP | 0.164*** | 0.150*** | 0.134*** | 0.164*** |

| (0.050) | (0.056) | (0.044) | (0.039) | |

| Density of CSPa | −0.473 | −0.300* | −0.555** | −0.469** |

| (0.468) | (0.183) | (0.199) | (0.166) | |

| Density of CGP | −0.322* | 0.054 | −0.056 | −0.200** |

| (0.168) | (0.085) | (0.137) | (0.092) | |

| Density of private hospital beds | 0.010 | 0.096* | 0.067* | −0.020 |

| (0.043) | (0.050) | (0.038) | (0.050) | |

| Density of public hospital beds | 0.021* | −0.003 | 0.014 | 0.015 |

| (0.012) | (0.014) | (0.014) | (0.016) | |

| Average income | 0.132 | 0.354 | 0.314 | −0.143 |

| (0.198) | (0.244) | (0.202) | (0.265) | |

| Education | 0.671* | 0.280 | 0.104 | 1.290*** |

| (0.362) | (0.302) | (0.286) | (0.290) | |

| Living area | −0.002 | −0.030** | −0.017 | 0.002 |

| (0.007) | (0.013) | (0.012) | (0.009) | |

| Observations | 847 | 847 | 847 | 847 |

| R2 | 0.706 | 0.755 | 0.572 | 0.716 |

| Overidentification: χ2(13) | 14.556 | 9.465 | 9.597 | 17.500 |

Contract physician with identical specialty as the corresponding dependent variable.

PSPS, non-contract surgeons; PSPN, non-contract neurologist; PSPG, non-contract gynecologists; PSPI, non-contract internists. Intercept not reported. Bootstrapped standard errors in parentheses (50 replications).

Significance at 10 percent level.

Significance at 5 percent level.

Significance at 1 percent level.

Comparing the estimation results of Table 6 with the ones of Table 5, we firstly observe positive parameter estimates for the density of PGPs, which seems to confirm the above mentioned cooperation and network effects between non-contract physicians according to Hypothesis 3. Further, and in line with Hypothesis 2, we find negative effects of CGP density again, indicating competition between PSPs and CGPs. The exceptions are neurologists and gynecologists with insignificant parameter estimates, but significantly positive estimates for private facilities of inpatient care. This is not surprising as patients usually do not visit a GP when demanding services from these specialities. Most importantly however, we now find a significantly negative impact of CSP densities on the ones of non-contract specialists in three out of four regressions (the exception is non-contract surgeons in column 1 of Table 6), indicating that there is competition between non-contract and contract specialists within the same specialization. This result is consistent with Hypothesis 1 and, to some extent, it also confirms Atella and Deb [3], who find a substitutive individual health care utilization between contract and non-contract physicians using Italian data.

Overall, our estimation results suggest that referrals from CGPs to PSPs are obviously not strong enough to compensate competition forces between contract and non-contract physicians, which are inherently present in the two-tiered Austrian health care system. In contrast, we find a more pronounced referral behavior for PGPs, indicating cooperation and network effects within non-contract physicians. Further, our results reveal that location decisions of PSPs are negatively associated with the density of CSPs (at least within the same specialty), suggesting that the market for outpatient health care of specialists reacts to competitive forces.

4. Conclusions

This paper assesses location decisions of physicians as measured by physician densities at the regional level. We extend the previous research relying on a two-tiered health care system with co-existing public (contracted) and private health care providers. Using data from 121 Austrian districts between 2002 and 2008 we focus on four groups of physicians: contract general practitioners and specialists as well as their private counterparts. The latter are almost free to set prices for their services and, apart from that, are not restricted in their location choices. Therefore, we estimate the densities of (i) non-contract specialists and (ii) non-contract general practitioners as a function of the densities of contract general practitioners and specialists and the remaining density of non-contract physicians, along with other control variables such as the availability of private and public inpatient facilities within a district. Some of these variables are potentially endogenous, others are time-invariant (e.g., the availability of hospitals), suggesting to apply a Hausman–Taylor framework for panel data in our application.

Our findings might be summarized as follows. First, we find a positive association between the densities of non-contract general practitioners and non-contract specialists, indicating a relatively strong referral effect between these groups of physicians. One reason might be strong collaboration or even the existence of medical networks among non-contract physicians. Second, we observe a negative impact of the density of contracted specialists on the one of non-contract physicians, indicating relatively strong competition forces among these physicians. Finally, we observe a negative impact of the density of contract general practitioners on non-contract general practitioners, and an insignificant effect on non-contract specialists. While the former result might be explained by competition among (contract and non-contract) general practitioners, the latter might be a result of the referral behavior of contract general practitioners, who tend to prefer contract physicians when referring to specialists.

This paper contributes to the ongoing debate on the role of non-contract physicians in the two-tiered Austrian health care system in general, and as a provider of care for clients of the public insurance system in particular. To date, private (non-contract) resources of outpatient care are not included in the physician capacity plans of the public health insurance system. While non-contract physicians to some extent enlarge the consumer choice for publicly funded outpatient care, private treatments usually also involve substantial cost sharing. Thus, this enlargement effect is particularly relevant for high income patients. Furthermore, we observe a marked increase in the number of non-contract physicians (PSPs and PGPs) over the course of the years, while the number of contract physicians strictly follows the capacity plans, and therefore, remained nearly constant over the same time period. Given the high number of medical graduates from medical universities, the relevance of the private health care sector will increase further in the near future.

From a health policy perspective, the positive relationship between different non-contract physician categories is ambiguous. On the one hand, it could reflect the existence of efficient referral systems. But on the other hand, the expanding number of private physicians could also indicate an increase of supplier induced demand, which could adversely influence the macroeconomic stability of the outpatient sector as a whole. The negative relationship between non-contract and contract physicians – signaling a substitution effect – could lead to the interpretation that the private sector to some extent is an alternative to the public sector. Given the existing institutional design, this empirical pattern could imply that either (i) the current capacity plans are not sufficient for their specified goal of equity in the form of an area-wide health care provision and/or (ii) that both the increase in the number and the positive relationship between the different types of non-contract physicians indicate a possible increase of supplier induced demand with negative effects on service quality and the financial accountability of the system in general.

While our results might stimulate further research on location decisions of physicians, we would be cautious to derive too far-reaching policy recommendations from our analysis. The paper primarily focuses on spatial differences in non-contract physician density. Obviously, these differences reflect varieties in the (expected) demand for physician services, but we would need more information on the actual utilization patterns of both contract and non-contract physicians to propose possible changes in the institutional design of outpatient care. Thus, further analysis seems necessary based on more detailed information of utilization numbers, patients’ motives to visit a non-contract physician (e.g., quality, waiting time, and distance), and the interaction of different physician categories. Such an analysis is beyond the scope of our paper. In addition, the necessary data to study such issues is not available so far. As non-contract physicians are hardly regulated in Austria, they constitute somewhat a ‘black box’ even for the public health insurance, which (at least in part) pays for their services. Thus, our findings also suggest to establish a reporting system for non-contract physicians to analyze interdependencies between different types of physicians further.

Footnotes

Patients are also allowed to visit ambulatory care facilities of the public sickness funds. These facilities are especially important in dental care (exemptions are the provinces of Vienna and Styria, where ambulatory care facilities offer a broader range of services). In the empirical analysis below, we do not include dentists and, therefore, also leave out ambulatory facilities.

This is essentially the case for the sickness funds which are organized on territorial principles (Gebietskrankenkassen), basically covering employees in the private sector and roughly including 80 percent of the Austrian population. The corresponding regulatory framework of sickness funds for farmers, self employed and civil servants is somewhat different (especially with regard to the above mentioned cost-sharing elements).

Rough calculations for the period 2000–2004 show that the cost sharing percentage of the submitted physician bills amounts to about 40–70 percent, with huge differences among specialties. Public insurance officials argue that only 50 percent of the public insured patients submit their physician bill for reimbursement. Thus, we presume that the overall percentage of cost-sharing to utilize non-contract physician services is even higher than the share mentioned above. In addition, our data show that the public health insurance system spends around 10 percent of its expenditure for outpatient care to reimburse the costs of non-contract physicians. Finally, the costs of non-contract physicians are not reimbursed if the patient further contacts a contract physician of the same type within the same accounting period.

Apart from this practical experience, it has to be mentioned that the gatekeeping role of GPs is relatively weak in Austria, not only for non-contract but also for contract physicians. Referral is only compulsory for some very specific outpatient services (especially X-rays and other diagnostic procedures such as computer tomography or magnetic resonance) and for hospital stays [21]. In addition, hospitals also run outdoor departments (ambulances). Access to these ambulances does not require referrals from GPs or specialists.

Interestingly, the literature on the physicians’ referral behavior is relatively scarce. One exception is Atella and Deb [3], who analyze doctor visits in Italy at the individual level. Among other things, they observe that contract and non-contract specialist visits are negatively affected by primary care physician visits, indicating a competitive relationship between primary care physicians and specialists. However, the corresponding coefficient on non-contract specialists is much higher than the one on contract specialists, which, in turn, seems to confirm our observation from Austria that CGPs typically prefer CSPs over PSPs when referring to specialists.

Similarly, Atella and Deb [3] find that visits to primary care physicians, contract specialists and non-contract specialists are all positively related to unobserved heterogeneity. While we are not able to draw such a conclusion due to a lack of individual data, this result also suggests a positive relationship among non-contract physicians, as they will tend to locate in attractive markets where the demand for health care is high, i.e., where people are already consuming a high amount of health care services.

At the sub-national level, Austria is organized in nine federal states, 121 regional districts (including 23 districts of Vienna) and 2357 local jurisdictions (communities and cities).

A correlation matrix reveals that there is a close relationship between all suppliers of the health care system, which is not surprising given the above-mentioned interrelations among contract and non-contract physicians and hospital facilities. The corresponding figures are available from the authors upon request.

Denoting each variable in our model with , the GLS transform is given by , where in Eq. (1)[18, p. 338]. Similar applies to Eq. (2).

Below, we do not report the results of FE-estimation and also the ones without logarithms for the sake of brevity. They are available from the authors upon request.

Appendix A. Data sources

-

•

Data on physician location is taken from CD-MED. Handbuch für die Sanitätsberufe Österreichs. Wien: Verlag Dieter Göschl; 2002–2008.

-

•

Information on the number of hospital beds in public and private hospitals is covered in BMG. Krankenanstaltenverzeichnis Österreich. Wien: Bundesministerium für Gesundheit; 2008.

-

•

Data on a district's population, educational level and living area is compiled in Statistik Austria. Volkszählung, Wien (Austrian Population Census); 2002.

-

•

Region's income is calculated from Statistik Austria. Integrierte Statistik der Lohn- und Einkommensteuer. Wien; 2004–2006.

References

- 1.Abraham J.M., Gaynor M., Vogt W.B. Entry and competition in local hospital markets. Journal of Industrial Economics. 2007;55:265–288. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amemiya T., MaCurdy T.E. Instrumental-variable estimation of an error-components model. Econometrica. 1986;54:869–880. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atella V., Deb P. Are primary care physicians, public and private sector specialists substitutes or complements? Evidence from a simultaneous equations model for count data. Journal of Health Economics. 2008;27:770–785. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumgardner J.R. Physicians’ services and the division of labor across local markets. Journal of Political Economy. 1988;96:948–982. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolduc D., Fortin B., Fournier M.-A. The effect of incentive policies on the practice location of doctors: a multinomial probit analysis. Journal of Labor Economics. 1996;14:703–732. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brasure M., Stearn S.C., Norton E.C., Ricketts T., III Competitive behavior in local physician markets. Medical Care Research and Review. 1999;56:395–414. doi: 10.1177/107755879905600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bresnahan T.F., Reiss P.C. Do entry conditions vary across markets? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 1988;99:977–1009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bresnahan T.F., Reiss P.C. Entry in monopoly markets. Review of Economic Studies. 1990;57:531–553. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bresnahan T.F., Reiss P.C. Entry and competition in concentrated markets. Journal of Political Economy. 1991;3:833–882. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capps C., Dranove D., Lindrooth R.C. Hospital closure and economic efficiency. Journal of Health Economics. 2009;29:87–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson R., MacKinnon J.G. Oxford University Press; New York: 1993. Estimation and inference in econometrics. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis K., Marshall R. New developments in the market for rural health care. In: Scheffler R.M., editor. Research in health economics. JAI Press; Greenwich: 1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Detsky A.S. Ballinger Publishing Company; Cambridge, MA: 1978. The economic foundations of national health policy. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Earickson RJ. The spatial behavior of hospital patients. Department of Geography Research Paper No. 124. University of Chicago; 1970.

- 15.Foster S.A., Gorr W.L. Federal health care policy and geographic diffusion of physicians: a macro-scale analysis. Policy Sciences. 1992;25:134–177. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fruen M.A., Cantwell J.R. Geographic distribution of physicians: past trends and future influences. Inquiry. 1982;19:44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaynor M., Haas-Wilson D. Change, consolidation, and competition in health care markets. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1999;13:141–164. doi: 10.1257/jep.13.1.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greene W.H. 6th ed. Pearson-Prentice-Hall; Upper Seattle River, NJ: 2008. Econometric analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hausmann J.A., Taylor W.E. Panel data and unobservable individual effects. Econometrica. 1981;47:455–473. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi F. Princeton University Press; Princeton: 2000. Econometrics. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmarcher M.M., Rack H.M. Austria, health system review. Health Systems in Transition. 2006;8:1–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hurley J.E. Physician’ choices of specialty, location, and mode – a reexamination within an interdependent decision framework. Journal of Human Resources. 1989;26:47–70. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang J.H., Begun J.W. Dynamics of change in local physician supply: an ecological perspective. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;54:1525–1541. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaplan R.S., Leinhardt S. Determinants of physician office location. Medical Care. 1973;11:406–415. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kristiansen I.S., Forde O.H. Medical specialists’ choice of location: the role of geographical attachment in Norway. Social Science and Medicine. 1992;34:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90067-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonardson G., Lapierre R., Hollingsworth D. Factors predictive of physician location. Journal of Medical Education. 1985;60:37–43. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin G., Rosenthal T., Horwitz M. Physician location survey: self-reported and census-defined rural/urban locations. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;44:1761–1766. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00378-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrisey M.A., Kletke P.R., Marder W.D. The role of local hospitals in physician location decisions. Inquiry. 1991;28:7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newhouse J.P., Williams A.P., Bennet B.W., Schwartz W.B. Does the geographical distribution of physicians reflect market failure? Bell Journal of Economics. 1982;13:493–505. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nocera S, Wanzenried G. On the dynamics of physician density: theory and empirical evidence for Switzerland. Diskussionsschriften der University of Bern No. 02-08. University of Bern; 2002.

- 31.Noether M. The growing supply of physicians: has the market become more competitive? Journal of Labor Economics. 1986;4:503–537. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Propper C. The demand for private health care in the UK. Journal of Health Economics. 2000;19:855–876. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(00)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenthal M.B., Zslavsky A., Newhouse J.P. The geographic distribution of physicians revisited. Health Services Research. 2005;40:1931–1952. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00440.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samhaber I. Motivation zum Wahlarztbesuch unter besonderer Berücksichtigung von Gender Aspekten – Eine empirische Studie. Unpublished thesis. Linz; 2003.

- 35.Schaumans C., Verboven F. Entry and regulation: evidence from health care professions. RAND Journal of Economics. 2008;39:949–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-2171.2008.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheffler R.M., Yoder S.G., Weisfeld N., Ruby G. Physicians and new health practitioners: issues for the 1980. Inquiry. 1979;16:195–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Theurl E., Winner H. The male–female gap in physician earnings: evidence from a public health insurance system. Health Economics. 2010;20:1184–1200. doi: 10.1002/hec.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]