Abstract

Taste phenotypes have long been studied in relation to alcohol intake, dependence, and family history, with contradictory findings. However, on balance – with appropriate caveats about populations tested, outcomes measured and psychophysical methods used – an association between variation in taste responsiveness and some alcohol behaviors is supported. Recent work suggests super-tasting (operationalized via propylthiouracil (PROP) bitterness) not only associates with heightened response but also with more acute discrimination between stimuli. Here, we explore relationships between food and beverage adventurousness and taste phenotype. A convenience sample of wine drinkers (n=330) were recruited in Ontario and phenotyped for PROP bitterness via filter paper disk. They also filled out a short questionnaire regarding willingness to try new foods, alcoholic beverages and wines as well as level of wine involvement, which was used to classify them as a wine expert (n=110) or wine consumer (n=220). In univariate logisitic models, food adventurousness predicted trying new wines and beverages but not expertise. Likewise, wine expertise predicted willingness to try new wines and beverages but not foods. In separate multivariate logistic models, willingness to try new wines and beverages was predicted by expertise and food adventurousness but not PROP. However, mean PROP bitterness was higher among wine experts than wine consumers, and the conditional distribution functions differed between experts and consumers. In contrast, PROP means and distributions did not differ with food adventurousness. These data suggest individuals may self-select for specific professions based on sensory ability (i.e., an active gene-environment correlation) but phenotype does not explain willingness to try new stimuli.

Keywords: taste genetics, PROP, propylthiouracil, super tasters, food adventurousness, wine adventurousness

1. Introduction

The perception of taste and flavor are important factors affecting the liking of food and beverages, and consequently, purchase decisions. An understanding of individual differences in orosensation is therefore of considerable interest to food and beverage producers, including the wine industry, as these differences may represent important product development and marketing opportunities from market segmentation based on ‘taste’ types or responsiveness (Pickering and Cullen 2008). Genetic variation is a major determinant of individual differences in orosensation, and may be the most important influence on food and beverage behaviour (Garcia-Bailo et al. 2009). Responsiveness to the bitterant 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) has been widely adopted as a marker of genetic variation in taste. Individuals have traditionally been classified as PROP non-tasters (those for whom PROP elicits no or slight bitterness), PROP medium-tasters (those for whom PROP is mildly bitter) or PROP super-tasters (those for whom PROP is intensely bitter). Differential bitterness of PROP associates with variation in the TAS2R38 gene, but these polymorphisms do not adequately explain supertasting (see Hayes et al. 2008).

Importantly, heightened responsiveness to PROP is associated with heightened responsiveness to sensations typically elicited by alcoholic beverages such as burn (Duffy et al. 2004b, Prescott and Swain-Campbell 2000), sourness from carbonation (Prescott et al. 2004), astringency in red wine (Pickering et al. 2004), and bitterness in scotch (Lanier et al. 2005) and beer (Intranuovo and Powers 1998, Lanier et al. 2005), as well as self-reported intake (Duffy et al. 2004a, Duffy et al. 2004b), which appears to be mediated via differences in the endogenous sensory properties of these beverages (Lanier et al. 2005). Also, several recent studies show that those who experience PROP as being intensely bitter (i.e., super-tasters) not only experience heightened overall oral sensation, but may also be more acute tasters, with the ability to discriminate smaller differences between oral stimuli (Hayes et al. 2010, Lee et al. 2008, Pickering et al. 2004, Prescott et al. 2004). These data are consistent with the unpublished report that chefs find PROP to be more bitter than controls (Bartoshuk et al. 2004a).

Personality factors are often ignored or marginalized in taste phenotype research, yet one variable that likely moderates ingestive behaviors is willingness to try new food and beverages. This willingness varies across individuals and is often conceptualized as food ‘adventurousness’ or ‘neophobia’. Differences in food adventurousness is one possible explanation for contradictory findings on the significance of PROP phenotypes to real world food/beverage preference, liking and/or intake. For instance, Tepper and students speculated previous studies may have overestimated the influence of PROP responsiveness on rejection of strong-tasting foods by not distinguishing individuals by food adventurousness (Ullrich et al. 2004). They reported that PROP tasters who were more food adventurous liked strong alcohol, hot sauce, chili peppers, other pungent condiments, and bitter fruits and vegetables more than tasters who were less food adventurous. Food neophobia (Logue and Smith 1986) and sensation seeking (Rozin 1990) have previously been linked with different food and/or beverage preferences amongst individuals. Compared with many other foods/beverages, wine can be viewed as a product for which there is a high level of perceived risk in consumers’ minds, given its social cachet, varied nature and complexity (Lacey et al. 2009). Arguably, this may attach greater importance to individual adventurousness and ‘expert’ endorsements in mediating consumer preference and purchase decisions.

Purchase decisions for wine consumers are influenced by wine experts or authority figures, particularly wine writers, wine judges and trained wine retail staff, who help remove some of the perceived risk involved in purchasing wine by providing guidance to consumers regarding quality, taste profile and relative value. Thus, an interesting consideration is the extent of concordance in taste phenotype, and particularly PROP, distributions between these wine experts and the ‘typical’ wine consumers for whom they are making quality judgments and purchase recommendations. A related consideration is that of the taste phenotype distributions of winemakers – a sub-set of wine experts – relative to wine consumers, given the important role of the winemaker’s own palate and attendant taste ‘sensitivities’ in designing the final product. Here, we explore the relationship between food and beverage adventurousness and taste phenotype (PROP bitterness) among a cohort of wine drinkers that includes both regular consumers and wine experts.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Individuals of legal drinking age were surveyed at a range of locations around the Niagara Peninsula. This included: local LCBO (Liquor Control Board of Ontario) stores (government owned wine and spirits shops in Ontario), staff, faculty and students at Brock University, Niagara Peninsula wineries, and wine events on and off the Brock campus. The Brock University Ethics Board approved all procedures. Participants were given the opportunity to ask any questions pertaining to the study and their involvement before providing written informed consent. As an incentive, participants were entered in a random drawing for one $200 book voucher.

2.2. Questionnaire

Participants who reported consuming alcohol beverages were asked to complete a brief questionnaire. Demographic data (age, sex, and ethnicity) were collected, along with food and beverage adventurousness, and wine involvement (presented below). Measures of intake and liking of a variety of alcoholic beverages were also obtained and will be reported fully elsewhere.

2.3. Propylthiouracil phenotyping

Propylthiouracil response was determined after the method of Zhao et al (2003) using filter paper disks impregnated with 50 mmol/l PROP. Participants placed the disk on their tongues, allowing it to moisten with saliva. They then rated the perceived bitterness of PROP using the generalized labeled magnitude scale (gLMS) (Bartoshuk et al. 2004b). A candy was then provided to participants to help alleviate any lingering bitterness.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC). Relationships between trying new wines, beverages, foods and expertise were compared with univariate and multivariate logistic regression. Group mean bitterness of PROP was compared using t-tests, and the distribution of bitter response (kernel density estimates) was compared via proc kde using the default bandwidth selection options (the Sheather Jones Plug In (SJPI) method). Here, PROP bitterness was treated as a continuous trait. That is, we did not trichotomize individuals into groups of non-, medium- and super-tasters using a priori cutoffs, as such a binning approach is largely a statistical convenience to allow for the use of ANOVA models in analysis. Binning does not reflect the continuous nature of PROP bitterness and costs power (see Hayes and Duffy 2007 for a discussion).

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Participants (n=330) were asked to indicate their wine involvement by endorsing the items in Table 1, and were allowed to check as many items as were applicable (259 endorsed 1 item, 61 endorsed 2 and 10 endorsed 3). Among the 51 individuals who indicated they were ‘another type of wine professional’, 11 were amateur winemakers, 10 were winery workers, 9 were wine merchants, and 5 were winery owners. For the present analyses, we classified individuals as wine experts if they were professional winemakers, wine writers, LCBO consultants, wine judges, or some other type of wine professional (n=110). All other participants were classified as non-experts (n=220).

Table 1.

Self Identified Characteristics of Participants

| Descriptor [check all that apply] | No. Endorsements |

|---|---|

| I drink wine only on rare occasions | 14 |

| I drink wine occasionally | 255 |

| I am a professional winemaker | 22 |

| I am a wine writer | 3 |

| I am an LCBO Product Consultant | 21 |

| I am another type of wine professional | 51 |

| I serve or have served as a judge of commercial wine at wine show(s) | 34 |

| None of the above | – |

3.2. Food Adventurousness, Wine Expertise and Trying New Beverages

Participants indicated how often they try unfamiliar foods, and unfamiliar alcohol beverages using a 4 point Likert scale: ‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘some of the time’, and ‘most of the time’. After being asked about their involvement with wine (see Table 1), they were also asked “how often do you try wines that you haven’t tried before?”, with the same response categories as above. Like Ullrich et al. (2004), we collapsed across response categories to dichotomize individuals into high or low groups, although we used a different cutoff, collapsing the first 3 categories in ‘some of the time or less’ for comparison to ‘most of the time’. To maintain consistency, we used the same cutoff across all three questions. For wine adventurousness, 165 individuals fell in the low group versus 163 in the high group. For unfamiliar alcohol drinks, the low group contained 254 individuals versus 76 individuals in the high group. For food, the low group had 219 individuals compared to 111 in the high group.

The odds of trying new wines and unfamiliar alcoholic beverages were significantly greater in those individuals who exhibited more food adventurousness (e.g. endorsed trying unfamiliar foods most of the time). Conversely, food adventurousness did not predict wine expertise (Table 2). As expected, the odds of wine experts trying new wines and unfamiliar alcoholic beverages were also greater, and again, no association was seen between wine expertise and willingness to try unfamiliar foods.

Table 2.

Summary of Univariate Logistic Regression Models

| Outcome | Predictor | Odds Ratio | 95% Wald CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tries New Wines | Food Adventurousness | 2.29 | 1.56–3.36 | 0.0001 |

| Tries Unfamiliar Alcoholic Beverages | Food Adventurousness | 5.67 | 3.34–9.63 | 0.0001 |

| Wine Expertise | Food Adventurousness | 0.84 | 0.58–1.23 | 0.37 |

| Tries New Wines | Wine Expert | 4.18 | 2.54–6.90 | 0.0001 |

| Tries Unfamiliar Alcoholic Beverages | Wine Expert | 2.59 | 1.53–4.38 | 0.0004 |

| Food Adventurousness | Wine Expert | 1.04 | 0.64–1.69 | 0.87 |

Because frequency of trying new wines and unfamiliar alcoholic beverages both associated with frequency of trying new foods, we then tested whether wine experts were more willing to try new wines or drinks when controlling for differences in food adventurousness using multivariate logistic regression (Table 3). In the multivariate analysis, greater food adventurousness and wine expertise made independent contributions to the willingness to try new wines and unfamiliar alcoholic beverages. Propylthiouracil bitterness did not. The relative influence of each predictor differed by outcome measure. Regarding willing to try new wines, wine expertise played a larger role than food adventurousness whereas the reverse was true for willingness to try new alcoholic drinks (i.e., food adventurousness mattered more than wine expertise).

Table 3.

Summary of Multivariate Logistic Regression

| beta | SE | Odds Ratio | 95% Wald CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV: Tries New Wines | ||||

| Wine Expert | 1.50 | 0.27 | 4.47 | 2.65–7.54 |

| Food Adventurousness | 0.87 | 0.21 | 2.40 | 1.60–3.61 |

| PROP Bitterness | 0 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.99–1.01 |

| DV: Tries Unfamiliar Alcoholic Beverages | ||||

| Wine Expert | 1.11 | 0.30 | 3.06 | 1.69–5.54 |

| Food Adventurousness | 1.83 | 0.29 | 6.21 | 3.55–10.86 |

| PROP Bitterness | 0 | 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.99–1.01 |

3.3. PROP bitterness, wine expertise, and food adventurousness

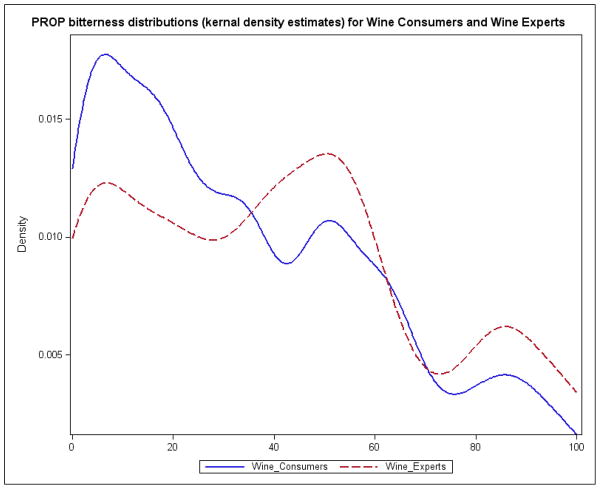

When comparing group means, there was a significant effect for PROP bitterness [t(328) = 2.16, p = 0.03], with experts experiencing higher bitterness than non-experts. Plots of the bitterness probability distribution functions confirm and extend this finding (Figure 1). For both experts and non-experts, the smoothed bitterness distributions were trimodal. These three modes are roughly analogous to the non-, medium- and super-taster groupings commonly used in the field. Here we reuse the same nomenclature for comparability with prior work and ease of discussion while noting that PROP bitterness is a continuous trait and a priori classification cutoffs were not applied here. Notably, the conditional distribution functions indicate wine experts were underrepresented among the non-tasters and over represented among both the medium and super-tasters.

Figure 1.

Differences in PROP distribution across wine expertise. The distributions shown are Kernel Density Estimates (KDE) for Wine Experts and Wine Consumers (see section 3.1 of the text and Table 1 for how expertise was determined.) Frequency is on the y-axis and PROP bitterness is on the x-axis. Both distributions were trimodal, roughly corresponding to the non-, medium- and super-taster groupings classically used in the field.

In contrast to the wine expert-wine consumer difference noted above, the mean PROP bitterness did not differ with food adventurousness [t(327) = 0.26, p = 0.8].

4. Discussion

In this field-based study of adults who consume wine, taste phenotype (PROP bitterness) varied systematically with wine expertise. Previously, it has been suggested in a review that super-tasters are over represented among culinary school students, chefs and other food experts (Bartoshuk et al. 2004a). Here, we show wine experts experienced greater PROP bitterness than wine consumers, and more interestingly, the distribution of bitterness was skewed toward experts being overrepresented among medium and super-tasters, and underrepresented among non-tasters. Also, we found food adventurousness and expertise, but not taste phenotype, were related to willingness to try new wines and alcoholic beverages, Finally, the present study took pains to treat PROP bitterness as a continuous trait (see Hayes and Duffy 2007 for a discussion) – yet even when it was modeled without any binning based on a priori cut-points, the distributions were trimodal, roughly analogous to the non-, medium- and super-taster labels classically used in the field. A preliminary analysis of the alcoholic beverage liking data collected here suggests a more narrow range of products – almost exclusively wine - define the preference ‘matrix’ of wine experts than is the case for wine consumers. Future work will examine the possible interaction between PROP responsiveness and wine expertise on alcoholic beverage liking and intake.

Recent work indicates those who taste PROP bitterness more intensely may not only experience heightened intensity across multiple orosensory qualities (e.g., Bajec and Pickering 2008, Hayes et al. 2008), but also may have a more acute sense of taste. Specifically, individuals who report greater PROP bitterness show greater discrimination ability within a forced choice paradigm (Prescott et al. 2004), larger changes in intensity and liking across a concentration series (Hayes et al. 2010), and show finer discrimination of the mouthfeel qualities elicited by red wine (Pickering and Gordon 2006). Together, these lines of evidence support the idea that individuals may self-select for certain professions (or interests) based on some degree of innate taste advantage. Indeed, we recently found “foodies” (individuals who gave higher affective ratings to food than nonfood items compared to others) were more likely to be super-tasters (Minski et al. 2010).

Present work and the Minski finding may be initial evidence of an active gene-environment correlation (rGE) for taste. Within the behavioral genetic taxonomy established by Plomin and colleagues, active rGE occurs when genetically influenced behavior leads an individual to create, seek or select an environment that matches their genotype (see Rutter and Silberg, 2002), thus enhancing expression of a phenotype. Thus, we postulate that individuals who have greater native ability to discriminate between foods and beverages preferentially select for professions (chefs, wine experts) where this enhanced ability provides some competitive advantage. Superior innate ability would not, in and of itself, constitute a substitute for expertise developed over time, as an individual would also need to first have the desire to learn about wine and then to develop their ability to communicate those sensations to others. That is, the shift in the ‘basic-object level’ (see Solomon 1991) from describing a wine as a dry vs sweet white wine to describing it as a Kabinett vs a Trockenbeerenauslese Riesling depends on learning, not physiology. Still, Kirkmeyer and Tepper (2003) reported that PROP super-tasters use more terms to describe dairy products in free-choice-profiling, consistent with the idea that experts’ language use may reflect a more nuanced appreciation of the physical world (see Solomon 1990). Although seductive, additional data is needed to confirm the rGE hypothesis.

The above speculation hinges on the premise that perception of the orosensory sensations elicited by wine do, in fact, vary with PROP responsiveness. In studies that have used the accepted supra-threshold methods (as opposed to threshold-based phenotyping methods) to characterize individuals, this proposition is supported by the findings of Pickering et al (2004) and Pickering et al. (2006). Similarly, the sensations elicited from beer and blended scotch whisky also associate with PROP responsiveness (Lanier et al. 2005). Pickering et al (2010) failed to find an association between PROP responsiveness and sensations elicited by white and red wines. However, this null result may be due to their use of pectin as an inter-stimulus rinse, as pectin can bind proteins and polymorphisms in the salivary protein gustin may account for the different taste responsiveness between PROP phenotypes (Padiglia et al. 2010). Also, it is important to note that all 330 individuals in the present study were already wine drinkers, regardless of level of expertise. Thus, present data do not contradict the taste phenotype alcohol protection hypothesis found in the addiction and psychophysics literature. That is, there may be plenty of individuals in the population who experience heightened PROP bitterness and never acquire a taste for alcohol (the ‘tastes too strong’ protection hypothesis), but because our sample was recruited at wine events, those individuals would not be included in the dataset. Instead, our data indicate that heightened bitterness and taste acuity may encourage people to become wine experts once they are already wine consumers. Clearly, learning and opportunity also play a role in this process.

Regarding willingness to try new wines, expertise was more important than food adventurousness, while the reverse was true for willingness to try new alcoholic drinks. This makes intuitive sense, as experts must try new wines for professional reasons, whereas willingness to try other beverages may be more similar to their typical eating behavior. In contrast, mean bitterness did not differ with food adventurousness, nor was PROP response significant in the multivariate logistic regression models. This suggests taste phenotype does not influence willingness to try new foods, drinks or wines, at least in this sample.

5. Conclusion

The finding that wine experts are more likely to be super- or medium- tasters than other wine consumers may suggest a possible discordance in judgments of quality and value between the two groups. Wine consumers may wish to apply additional caution in adopting wine expert endorsements or recommendations – assessment of wine quality is dependent on both experience (and resulting expectancies) and liking, which is associated with taste responsiveness; both of these appear to vary between wine authority figures and wine consumers.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Discovery Grant to GJP) and the National Institute of Health grants DC010904 and AA07459 (support for JEH). Lynda Van Zuiden, Valerie Higenell and Martha Bajec, Brock University, are warmly thanked for their assistance with data collection. We also thank David DiBattista, and Gail Higenell, Brock University, and Isabelle Lesschaeve, Vineland Research and Innovation Centre, for their advice and assistance. Finally, the authors thank the study participants for their time and participation.

Literature Cited

- Bajec MR, Pickering GJ. Thermal taste, PROP responsiveness, and perception of oral sensations. Physiol Behav. 2008;95(4):581–590. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM, V, Duffy B, Chapo AK, Fast K, Yiee JH, Hoffman HJ, Ko CW, Snyder DJ. From psychophysics to the clinic: missteps and advances. Food Qual Pref. 2004a;15(7–8):617–632. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM, V, Duffy B, Green BG, Hoffman HJ, Ko CW, Lucchina LA, Marks LE, Snyder DJ, Weiffenbach JM. Valid across-group comparisons with labeled scales: the gLMS versus magnitude matching. Physiol Behav. 2004b;82(1):109–14. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartoshuk LM, V, Duffy B, Miller IJ. PTC/PROP tasting: anatomy, psychophysics, and sex effects. Physiol Behav. 1994;56(6):1165–71. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90361-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy VB, Davidson AC, Kidd JR, Kidd KK, Speed WC, Pakstis AJ, Reed DR, Snyder DJ, Bartoshuk LM. Bitter receptor gene (TAS2R38), 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) bitterness and alcohol intake. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004a;28(11):1629–37. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000145789.55183.D4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy VB, Peterson J, Bartoshuk LM. Associations between taste genetics, oral sensations and alcohol intake. Physiol Behav. 2004b;82(2–3):435–445. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Bailo B, Toguri C, Eny KM, El-Sohemy A. Genetic variation in taste and its influence on food selection. Omics. 2009;13:69–80. doi: 10.1089/omi.2008.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JE, Bartoshuk LM, Kidd JK, Duffy VB. Supertasting and PROP Bitterness Depends on More Than the TAS2R38 Gene. Chem Senses. 2008;33(3):255–265. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjm084. Epub 21 January 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JE, Duffy VB. Revisiting sugar-fat mixtures: sweetness and creaminess vary with phenotypic markers of oral sensation. Chem Senses. 2007;32(3):225–36. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjl050. First published January 4, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes JE, Sullivan BS, Duffy VB. Explaining variability in sodium intake through oral sensory phenotype, salt sensation and liking. Physiol Behav. 2010;100(4):369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intranuovo LR, Powers AS. The perceived bitterness of beer and 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) taste sensitivity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;855:813–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkmeyer SV, Tepper BJ. Understanding creaminess perception of dairy products using free-choice profiling and genetic responsivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil. Chem Senses. 2003;28(6):527–36. doi: 10.1093/chemse/28.6.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey S, Bruwer J, Li E. The role of perceived risk in wine purchase decisions in restaurants. International Journal of Wine Bus Res. 2009;21(2):99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lanier SA, Hayes JE, Duffy VB. Sweet and bitter tastes of alcoholic beverages mediate alcohol intake in of-age undergraduates. Physiol Behav. 2005;83(5):821–831. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YM, Prescott J, Kim KO. PROP taster status and the rejection of foods with added tastants. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2008;17(5):1066–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Logue AW, Smith ME. Predictors of food preferences in adult humans. Appetite. 1986;7(2):109–25. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6663(86)80012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minski KR, Bartoshuk LM, Hayes JE, Hoffman HJ, Rawal S, Duffy VB. NIH Toolbox: Proposed Food Liking Survey [abstract] Chem Senses. 2010;35(7):A21. [Google Scholar]

- Padiglia A, Zonza A, Atzori E, Chillotti C, Calo C, Tepper BJ, Barbarossa IT. Sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil is associated with gustin (carbonic anhydrase VI) gene polymorphism, salivary zinc, and body mass index in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(3):539–45. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering GJ, Cullen CW. The Influence of Taste Sensitivity and Adventurousness on Generation Y’s Liking Scores for Sparkling Wine. Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference of the Academy of Wine Business Research; Siena, Italy. July 17–19, 2008; 2008. (CD) [Google Scholar]

- Pickering GJ, Bartolini JA, Bajec MR. Perception of Beer Flavour Associates with Thermal Taster Status. J Inst Brew. 2010a;116(3):239–244. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering GJ, Gordon R. Perception Of Mouthfeel Sensations Elicited By Red Wine Are Associated With Sensitivity To 6-N-Propylthiouracil. J Sens Stud. 2006;21:249–265. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering GJ, Moyes A, Bajec MR, Decourville N. Thermal taster status associates with oral sensations elicited by wine. Austr J Grape Wine Res. 2010b;16(2):361–367. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering GJ, Simunkova K, DiBattista D. Intensity of taste and astringency sensations elicited by red wines is associated with sensitivity to PROP (6-n-propylthiouracil) Food Qual Pref. 2004;15(2):147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott J, Soo J, Campbell H, Roberts C. Responses of PROP taster groups to variations in sensory qualities within foods and beverages. Physiol Behav. 2004;82(2–3):459–69. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott J, Swain-Campbell N. Responses to Repeated Oral Irritation by Capsaicin, Cinnamaldehyde and Ethanol in PROP Tasters and Non-tasters. Chem Senses. 2000;25:239–246. doi: 10.1093/chemse/25.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P. Getting to like the burn of chili pepper: Biological, psychological and cultural perspectives. In: Green BG, Mason JR, Kare MR, editors. Chem Senses. Vol. 2. New York: Dekker; 1990. pp. 231–269. Irritation. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Silberg J. Gene-environment interplay in relation to emotional and behavioral disturbance. Ann Rev Psych. 2002;53:463–490. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon GE. Psychology of novice and expert wine talk. Am J Psych. 1990;103(4):495. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon GEA. Language and Categorization in Wine Expertise. In: Lawless HT, Klein BP, editors. Sensory Science Theory and Applications in Foods. M. Dekker; New York: 1991. pp. 269–294. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich NV, Touger-Decker R, O’Sullivan-Maillet J, Tepper BJ. PROP taster status and self-perceived food adventurousness influence food preferences. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(4):543–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Kirkmeyer SV, Tepper BJ. A paper screenig test to assess genetic taste sensitivity to 6-n-propylthiouracil. Physiol Behav. 2003;78(4–5):625–33. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]