Abstract

Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus is a bacterial parasite with an unusual lifestyle. It grows and reproduces in the periplasm of a host prey bacterium. The complete genome sequence of B. bacteriovorus has recently been reported. We have reanalyzed the transport proteins encoded within the B. bacteriovorus genome according to the current content of the transporter classification database (TCDB). A comprehensive analysis is given on the types and numbers of transport systems that B. bacteriovorus has. In this regard, the potential protein secretory capabilities of at least 4 types of inner membrane secretion systems and 5 types for outer membrane secretion are described. Surprisingly, B. bacteriovorus has a disproportionate percentage of cytoplasmic membrane channels and outer membrane porins. It has far more TonB/ExbBD-type systems and MotAB-type systems for energizing outer membrane transport and motility than does E. coli. Analysis of probable substrate specificities of its transporters provides clues to its metabolic preferences. Interesting examples of gene fusions and of potentially overlapping genes were also noted. Our analyses provide a comprehensive, detailed appreciation of the transport capabilities of B. bacteriovorus. They should serve as a guide for functional experimental analyses.

Keywords: Bacterial parasitism, transport, genome analyses, vectorial metabolism, protein secretion

Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus is a Gram-negative δ-proteobacterium that preys on other Gram-negative bacteria [1]. B. bacteriovorus penetrates the outer membrane of its prey and grows intraperiplasmically [2]. There it differentiates from the attack phase cell into the growth phase cell [1,3]. It loses its flagellum and initiates growth. At this point, B. bacteriovorus modifies the host cell peptidoglycan [4,5] and converts the host cell into a spherical structure called a bdelloplast in a process dependent on glycanase [2,6]. Not until 45 minutes after initiating the growth phase does DNA replication begin. During the following 2-3 hours, B. bacteriovorus causes extensive host cell damage and grows into a long coiled filament [7]. Late steps in the differentiation cycle can be completed outside of the host cell [8]. Although wild-type B. bacteriovorus is an obligate parasite, it can be mutated to grow in culture [9].

The B. bacteriovorus developmental cycle has been divided into eight phases according to morphological and physiological observations [7,10,11]: (1) The attack phase: B. bacteriovorus swims rapidly and collides with its prey, remaining reversibly attached for a short “recognition” period [12]. (2) Irreversible attachment: Active adhesion, possibly involving multiple fimbriae, occurs at the pole opposite the flagellum. (3) Invasion: B. bacteriovorus forms a “penetration pore” in the host cell outer membrane and cell wall [13]. Invasion may involve retractive fimbriae pulling the prey through the pore [11]. Pore formation is believed to occur when B. bacteriovorus locally secretes hydrolytic enzymes to degrade outer envelope constituents. Before entry into the periplasm, B. bacteriovorus frequently sheds its flagellum [10]. The pore is ultimately resealed by the host cell. (4) Macromolecular synthesis: B. bacteriovorus initiates macromolecular (RNA, protein, lipid, polysaccharide) synthesis. The first round of DNA synthesis occurs [2,14]. Since B. bacteriovorus can synthesize only 11 amino acids, protein synthesis depends on the uptake of host degradation products [11]. (5) Bdelloplast formation: The rod-shaped host cell rounds up into the spherical bdelloplast [2,15], and cell growth continues. (6) Septation: After formation of a single long snake-like cell, B. bacteriovorus synchronously undergoes septation, generating multiple progeny cells. (7) Flagellation: The progeny cells synthesize flagella while in the exhausted host bdelloplast. (8) Exit phase: B. bacteriovorus secretes novel hydrolytic enzymes that cause bdelloplast lysis. Release of the progeny attack cells is achieved [16]. This progression of developmental events may be initiated and regulated by a set of sensor kinase/response regulator systems and orchestrated by a sigma factor cascade similar in principle to that established for Bacillus sporulation [11,17,18].

Throughout most of the growth phase, prey cytoplasmic and integral membrane proteins are degraded, as are other host cell macromolecules [19,20]. There is evidence that B. bacteriovorus secretes proteins, possibly porins [21] but definitely many degradative enzymes [20]. Many of these appear in the host cell cytoplasm although the mechanisms by which they get there are unknown. Upon completion of growth, the single filamentous cell septates, giving rise to multiple motile cells, their numbers depending on the size of the prey cell [22]. Extensive signaling between the predator and prey bacteria seems to be operative [23,24]. B. bacteriovorus has the potential of being a therapeutic agent for treatment of Gram-negative bacterial infections [11,25,26,27].

In 2004, the genome sequence of B. bacteriovorus was published [11], allowing prediction of its physiology from its gene content. The single circular chromosome contains 3.8 Mbp and includes an estimated 3,600 coding regions. Only 55% of the deducted proteins were assigned a putative function based on homology searches. The rest were of unknown function. The transport systems predicted by annotation of the genome sequence were shown to fall in the classes of ABC-type transporters and MFS permeases or secondary carriers belonging to other transporter families. In this analysis, we are updating the list of transport systems according to the content of the January 2006 version of the transporter classification database (TCDB; http://www.tcdb.org/). We propose possible substrates and functions for some of these transporters.

B. bacteriovorus exhibits a number of properties that suggest the need for a most unusual complement of transport proteins. Several of its metabolic pathways may be incomplete, based on the available gene function annotations [11]. Neither oxidation nor fermentation of carbohydrates, organic acids or alcohols has been demonstrated [1,28]. Biochemically, this organism lacks the phosphoenolpyruvate-dependent sugar transporting phosphotransferase system (PTS) [19]. It seems to depend primarily on non-carbohydrate macromolecular metabolism for carbon and energy [1,29,30]. It secretes many macromolecular degradative enzymes including carbohydrases, proteases, nucleases and lipases [1,19,20]. Thus, it must have a tremendous capacity for protein secretion across both of its membranes [20]. It appears to grow largely at the expense of host cell proteins, nucleic acids, and membrane and cell wall constituents [1,31]. For example, up to 80% of degraded host nucleic acids is incorporated into B. bacteriovorus DNA [32]. However, this is just a fraction of the nucleotides required for growth, so B. bacteriovorus must be capable of making all of the nucleotides required for DNA synthesis. In fact, complete pathways for purine and pyrimidine biosynthesis are encoded within the genome [11].

Only a few molecular transport activities in B. bacteriovorus have been characterized, and even fewer transport proteins have been associated with these activities. The energy-dependent uptake of intact nucleotides (UMP and ATP) has been demonstrated [33,34]. Uptake of nucleotides appears to be a rare trait for a bacterium, but at least two such systems appear to exist in B. bacteriovorus. Neither has been characterized in molecular terms.

We have reanalyzed the complement of recognizable transporters encoded within the B. bacteriovorus genome 2 years after its original annotation, as a plethora of new sequences have been made publicly available during this time. The B. bacteriovorus genome analyses reported by Rendulic et al. [11] identified transporters as either permeases or ABC-type transporters. Here we present a systematic classification of the B. bacteriovorus transporters based on the TC system [35], which facilitates a more detailed understanding of transport function and evolution [36]. The methodology used has been described previously [37].

The genome of B. bacteriovorus reveals the presence of potential efflux pumps for hydrophobic and amphipathic drugs and organic solvents as well as potential uptake systems for amino acids, peptides and inorganic anions. The general secretory (Sec) system, the twin arginine targeting protein translocation system, and ABC-type protein secretion systems are also discussed. B. bacteriovorus encodes complete flagellar and fimbrial protein export systems and probably a type II main terminal branch (MTB; TC #3.A.15) for secretion of proteins across the outer membrane [38]. Several other protein export systems are described as well. These systems must account for the unusual parasitic lifestyle of this bacterium.

Results

Overview of Transporter Types

Table 1 presents an overall summary of the classes of transporters found in B. bacteriovorus. The 406 transport proteins make up 172 transport systems. 11.3% of the genes encode recognizable transport proteins, corresponding to established entries in TCDB. An additional 161 (4.5%) of its genes encode potential transporters that, however, do not give good hits in TCDB (see below). The total potential percent of transport protein encoding genes is therefore 15.8%. Since in most free-living bacteria, 10-15% of the genes encode transport proteins [39], B. bacteriovorus may contain an unusually large number of transporters especially considering the fact that the genomes of most intracellular parasites encode lower proportions of transport proteins [39]. The B. bacteriovorus genome encodes higher numbers of ABC-type transporters than most other bacterial genomes analyzed [11].

Table 1.

Overview of the Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus transporter analyses.

| TC Classa | Class Description | No. of Transport Proteinsb | TC Subclass | Subclass Description | No. of Transport Proteinsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Channels | 45 (29) | 1.A | α-type channels | 15 (12) |

| 1.B | β-barrel porins | 29 (16) | |||

| 1.C | Pore-forming toxins (proteins and peptides) | – | |||

| 1.D | Nonribosomally synthesized channels | – | |||

| 1.E | Holins | 1 (1) | |||

| 2. | Secondary carriers | 100 (70) | 2.A | Porters (uniporters, symporters, antiporters) | 73 (64) |

| 2.B | Nonribosomally synthesized porters | – | |||

| 2.C | Ion-gradient-driven energizers | 27 (6) | |||

| 3. | Primary active transporters | 227 (55) | 3.A | P-P-bond-hydrolysis-driven transporters | 202 (51) |

| 3.B | Decarboxylation-driven transporters | 4 (-) | |||

| 3.C | Methyltransfer-driven transporters | – | |||

| 3.D | Oxidoreduction-driven transporters | 21 (4) | |||

| 3.E | Light absorption-driven transporters | – | |||

| 4. | Group translocators | 0 | 4.A | Phosphotransfer-driven group translocators | - |

| 4.B | Nicotinamide ribonucleoside (NR) uptake permeases | - | |||

| 5. | Transmembrane electron carriers | 4 (2) | 5.A | Transmembrane 2-electron transfer carriers | 4 (2) |

| 5.B | Transmembrane 1-electron transfer carriers | – | |||

| 8. | Auxiliary transport proteins | 7 (-) | 8.A | Auxiliary transport proteins | 7 (-) |

| 9. | Poorly defined system | 23 (16) | 9.A | Recognized transporters of unknown biochemical mechanism | 4 (3) |

| 9.B | Putative uncharacterized transport proteins | 19 (13) | |||

| 9.C | Functionally characterized transporters lacking identified sequences | – | |||

| Total | 406 (172) | 406 (172) | |||

Transporter classes 6 & 7 have not been assigned in the TC system yet and therefore are absent from this table.

Numbers in parentheses represent the number of transport systems.

In most bacteria, approximately 3-8% of all the transport proteins encoded in the genome are channel-type transporters [39], B. bacteriovorus has a surprisingly large number of recognized channel proteins: 15 inner membrane channel proteins (3.7% of the total number of transport proteins) comprising 12 channels (7% of the transport systems), and 29 outer membrane porin-type channel-forming proteins (7.1% of the recognized transport proteins), corresponding to 16 systems, (9.3% of the transport systems). These numbers presumably reflect a need for rapid, low specificity uptake and export of ions and nutrients, consistent with the unusual lifestyle of B. bacteriovorus. Some of these channels may be expressed only at certain phases of the growth cycle (e.g., phase 4, see Introduction) or in response to specific stress conditions.

B. bacteriovorus has substantially more secondary carriers (70 systems, or 41% of the transport systems identified) than primary active transporters (55 systems, or 32%). The genome sequence gives no indication for group translocators of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS), confirming biochemical results of Romo et al. [19]. It has just two recognized transmembrane electron flow carrier, but 16 of its putative transporters fall into the TC class 9 category of poorly defined systems. Many (161) potential transport proteins (see below) have no counterpart in TCDB [35]. This is also an unusually large number for a bacterium with a genome of 3.8 Mbps. This observation may reflect a need for permeases of diverse function.

Transport Substrates

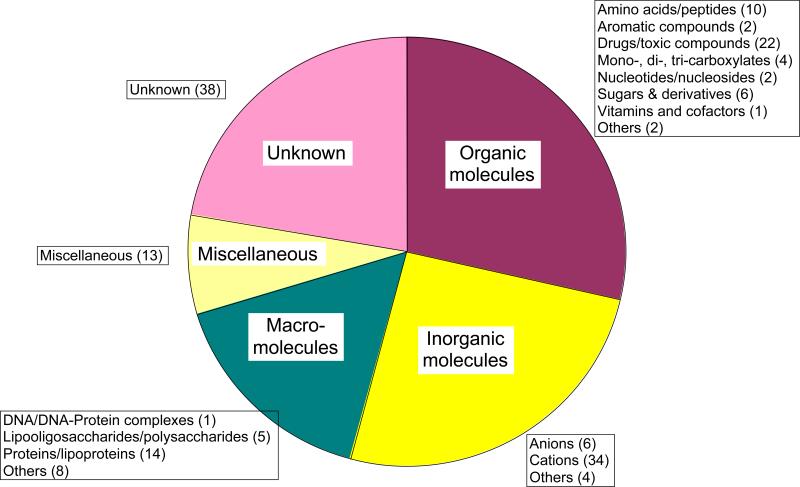

Figure 1 presents a breakdown of the transport systems according to substrate type. Forty-four (26%) of the recognized transporters are specific for inorganic molecules. Of these, the large majority transport cations (20%) while far fewer transport anions (3.5%). Nearly 2.5% are low specificity outer membrane porins.

Figure 1.

Pie chart of transporters in B. bacteriovorus according to predicted substrate specificity. Five different categories are shown. More detailed analyses, including numbers of systems found in each subcategory, specific for each substrate type are provided in the boxes adjacent to the five pieces of the pie. The chart is based on the data presented in Table 2 as discussed in detail in the text.

Small organic molecule transporters show a strong bias for drugs and toxic compounds, there being three times as many of these transporters as there are sugar or vitamin transporters. Systems specific for organic acids [40] are only half as plentiful as those for amino acids [14]. A few systems probably transport aromatic compounds and nucleosides. However, 22 transporters (13%) are drug/toxic compound efflux systems. This last percentage is comparable to, but on the high side relative to that found in many other bacteria.

Half of the macromolecular transporters are probably protein export systems, but lipid and polysaccharide exporters are also present. Nearly 30% of the identified transporters fall into the “miscellaneous” or “unknown” category. We suggest the probable substrates and transport mechanisms of several of these transporters. These results will be discussed in more detail below and on our website (http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/~msaier/supmat/Bba).

Distribution of Topological Types

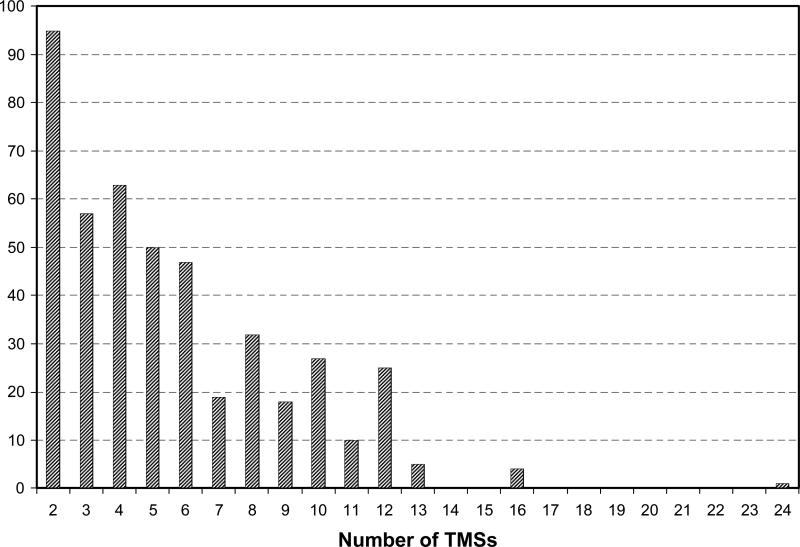

The TMHMM transmembrane helix prediction program [41,42] was used to predict the number of putative transmembrane segments (TMSs) in all the proteins encoded in the B. bacteriovorus genome. Of the 3587 recognized protein-encoding genes in B. bacteriovorus, 2736 (76%) are predicted to have 0 TMSs, and 849 (24%) are predicted to have 1 or more TMSs. Of the latter, 396 (11%) have only 1 TMS. Many of these will be secreted proteins such as periplasmic binding proteins, which require an N-terminal leader sequence to exit the cytoplasm via the general secretory (Sec) pathway. Remaining proteins with 2 or more TMSs (Fig. 2) include 453 proteins (13%), which have the greatest potential of being transporters. However, it should be noted some of these proteins are not involved in transport as discussed below. Further, only about half of the B. bacteriovorus proteins with 2 or more TMSs were classified into transporter families while a majority of the remainder were assigned as putative transporters with no functional information (see below). Of these, 152 (9.2%) have just 2 or 3 TMSs. Many of these are recognizable sensor histidine kinases, but those that function as transporters are likely to be oligomeric pore formers. No proteins with 3 or less TMSs per polypeptide chain have yet been identified that function as carriers [35,43]. Sixty-three proteins (1.8%) have 4 TMSs. These could be either carriers or channels. If carriers, they probably function as dimeric or tetrameric structures [44,45]. Proteins with 5 or more TMSs are likely to be secondary carriers or primary active transporters although some channel proteins are known to have 5 or more TMSs [46,47]. There are nearly equal numbers of predicted 5 and 6 TMS proteins (50 (1.4%) and 47 (1.3%), respectively) encoded within the B. bacteriovorus genome. Carriers of 5 or 6 TMSs generally function as dimers. Transmembrane proteins of 5 TMSs are mostly ABC transporters while those with 6 are primarily secondary carriers (see below). A total of 4.6% of the proteins in B. bacteriovorus have 4-9 TMSs; 7, 8 and 9 TMS carriers are also known [47]. Just 2% of the proteins have 10 or more TMSs. Of these, most are predicted to have 10 or 12 TMSs. As shown in Figure 2, large (≥10 TMSs) proteins with even numbers of TMSs predominate over those predicted to have odd numbers (77% even; 23% odd). We believe this has to do with the pathways taken for their evolutionary appearance [43]. The distribution of topological types is not strikingly different than from those of other bacteria [48,49]. The actual proportion of proteins with even numbers of TMSs may be even greater due to errors in topological prediction.

Figure 2.

Distribution of topological types of putative membrane proteins with 2-24 predicted TMSs. Number of proteins of a particular predicted topological structure is plotted on the X-axis versus the number of TMSs in that protein, plotted on the Y-axis. The plot illustrates the greater prevalence of proteins with even numbers of TMSs than odd numbers of TMSs with the sole exception of the putative 5 TMS protein. These 5 TMS proteins are common in secondary carriers and ATP-hydrolysis-driven uptake transporters of the ABC superfamily (see text). We believe this distribution reflects the evolutionary pathway taken for their appearance [43].

The five largest transmembrane proteins have 16 (4 proteins) and 24 (1 protein) TMSs. The 24 TMS protein (GI:42523740) is a member of the monovalent cation:proton antiporter-3 (CPA3) family (TC #2.A.63) and is a fusion of two previously recognized subunits of this multi-protein transporter complex [50,51]. Transporters of the CPA3 family include subunits that are homologous to subunits of the NADH dehydrogenase complex (TC #3.D.5). Of the four 16 TMS proteins, two (GI:42523556, GI:42523724) are of the CPA2 family (TC #2.A.37). Typical Na:H+ and K+:H+ antiporters of the CPA2 family have up to 14 TMSs (e.g., GmrA of Bacillus megaterium) [52]. The two B. bacteriovorus homologues proved to be fusion proteins where the integral membrane transporters are fused to soluble TrkA-like domains [53], and the two extra TMSs precede the TrkA domain, linking the transporter to this soluble regulatory domain.

The third 16 TMS protein (GI:42523211) is a member of the H+-translocating pyrophosphatase family (TC #3.A.10), most members of which have 16 TMSs [54]. Finally, the fourth 16 TMS protein (GI:42525209) is a homologue of subunit L of the proton-translocating NADH dehydrogenase complex which in other organisms has 16 TMSs.

Predicted Subcellular Localizations of B. bacteriovorus Proteins

We used the PSORTb program [55,56] to predict the subcellular localizations of the proteins in B. bacteriovorus. Of the assigned proteins, 860 proteins (23%) were predicted to be cytoplasmic, while 522 (14.1%) were predicted to be in the cytoplasmic membrane. Of the remaining, 56 (1.4%) may be in the periplasm, 100 (2.5%) may be in the outer membrane, and 31 (0.8%) may be extracellular. However, 2018 proteins (58%) could not be assigned a subcellular location using this program. It should be noted that the PSORTb program predicts slightly more proteins (14.1%) to be cytoplasmic membrane proteins than based merely on the number of proteins with 2 or more predicted transmembrane helices (13%) as noted above. The PSORTb program uses the HMMTOP algorithm to predict the number of transmembrane segments in a protein. Different prediction programs used to predict the topology and subcellular localization of proteins, often yield varying results [57].

Channels (TC #1.A)

As noted above, B. bacteriovorus has a large number of channel types. Three are homologous to known chloride channels of the ClC family (TC #1.A.11; Table 2). A fourth protein (GI:42524203) shows statistically significant sequence similarity to a central portion of an epithelial chloride channel (E-ClC, TC #1.A.13), but the rest of the protein does not resemble members of the E-ClC family. There is therefore no clear evidence that this protein functions in anion transport.

Table 2.

TC classification and functional predictions of putative transport proteins from Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus.

| TC Family | Family Name | Number of transport systemsa | Bba Protein ID | Size | # of TMSsb | Best blast-hit in TCDB and/or comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.A.11 | Chloride Channel (ClC) Family | 3 | 42523302 | 442 | 8 | EriC [E. coli] |

| 42523636 | 406 | 10 | MJ0305 [M. jannaschii] | |||

| 42523824 | 442 | 10 | EriC [E. coli] | |||

| 1.A.22 | Large Conductance Mechanosensitive Ion Channel (MscL) Family | 1 | 42521798 | 144 | 2 | MscL [E. coli] |

| 1.A.23 | Small Conductance Mechanosensitive Ion Channel (MscS) Family | 4 | 42521793 | 396 | 5 | KefA [E. coli] |

| 42523536 | 351 | 4 | MscMJLR-like [M. jannaschii] | |||

| 42524113 | 380 | 4 | MscMJLR [M. jannaschii] | |||

| 42524226 | 316 | 2 | KefA [E. coli] | |||

| 1.A.30.1 | H+- or Na+-translocating Bacterial Flagellar Motor (Mot) Family | 3 | 42521781 | 262 | 4 | MotA [B. subtilis] |

| 42521782 | 249 | 1 | MotS [B. subtilis] | |||

| 42524415 | 319 | 1 | MotS [B. subtilis] | |||

| 42524416 | 293 | 4 | PomA [V. alginolyticus] | |||

| 42524629 | 318 | 0 | MotB [E. coli] | |||

| 42524630 | 265 | 3 | MotA [E. coli] | |||

| 1.A.35 | CorA Metal Ion Transporter (MIT) Family | 1 | 42522589 | 308 | 2 | CorA [M. jannaschii] |

| 1.B.3 | Sugar Porin (SP) Family | 1 | 42522760 | 447 | 0 | LamB [E. coli] |

| 1.B.6 | OmpA-OmpF Porin (OOP) Family | 4 | 42521994 | 171 | 0 | OmpA [E. coli] |

| 42522454 | 368 | 0 | OmpATb-like [M. tuberculosis] | |||

| 42524036 | 440 | 0 | OmpATb-like [M. tuberculosis] | |||

| 42524180 | 214 | 0 | OmpATb [M. tuberculosis] | |||

| 1.B.10 | Nucleoside-specific Channel-forming Outer Membrane Porin (Tsx) Family | 2 | 42522254 | 269 | 0 | OmpK [V. parahaemolyticus] |

| 42524633 | 253 | 1 | OmpK-like | |||

| 1.B.14 | Outer Membrane Receptor (OMR) Family | 4 | 42522910 | 698 | 0 | FhuA [E. coli] |

| 42523077 | 709 | 0 | ViuA [V. cholerae] | |||

| 42524068 | 687 | 0 | FecA [E. coli] | |||

| 42524920 | 610 | 0 | BtuB [E. coli] | |||

| 1.B.17 | Outer Membrane Factor (OMF) Family | 42522293 | 426 | 1 | NodT2 [R. leguminosarum] [with 3.A.1.115] | |

| 42522458 | 434 | 0 | TolC [E. coli] [with 2.A.6.2] | |||

| 42522925 | 462 | 1 | ToxI-like [2.A.6.2] [B. glumae] | |||

| 42523285 | 485 | 0 | TolC-like | |||

| 42523393 | 437 | 0 | PrtF [E. coli] | |||

| 42523686 | 404 | 0 | TolC [E. coli] | |||

| 42524451 | 509 | 0 | VceC-like [V. cholerae] | |||

| 1.B.22 | Outer Bacterial Membrane Secretin (Secretin) Family | 42522439 | 726 | 0 | PilQ [P. aeruginosa] | |

| 42524863 | 222 | 0 | XcpQ [P. aeruginosa] | |||

| 1.B.33 | Outer Membrane Protein Insertion Porin (OmpIP) Family | 4 | 42521763 | 245 | 0 | YfiO [E. coli] ComL |

| 42523001 | 799 | 0 | YaeT [E. coli] | |||

| 42523064 | 573 | 0 | D15-like [H. influenzae] | |||

| 42523505 | 392 | 0 | YfgL [E. coli] | |||

| 42523581 | 803 | 1 | Imp [E. coli] | |||

| 42523924 | 929 | 0 | YaeT-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42524276 | 423 | 0 | YfgL-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42524950 | 392 | 0 | Omp85-like [N. meningitidis] | |||

| 1.B.x | Unclassified outer membrane protein | 1 | 42525165 | 216 | 1 | LolA-like OMP |

| 1.E.14 | LrgA Holin (LrgA Holin) Family | 1 | 42524812 | 129 | 4 | LrgA [S. aureus] |

| 2.A.1 | MFS Superfamily | |||||

| 2.A.1.2 | Drug:H+ Antiporter-1 (12 Spanner) (DHA1) Family | 6 | 42522009 | 396 | 12 | Bcr [E. coli] |

| 42522069 | 405 | 10 | TetA [E. coli] | |||

| 42522244 | 367 | 11 | TetA [E. coli] | |||

| 42522883 | 393 | 12 | YdeA [E. coli] | |||

| 42523627 | 412 | 12 | PbuE/YdhL [B. subtilis] | |||

| 42525027 | 397 | 12 | NepI [E. coli] | |||

| 2.A.1.4 | Organophosphate:Pi Antiporter (OPA) Family | 2 | 42523618 | 513 | 13 | UhpC [E. coli] |

| 42524319 | 497 | 12 | Hpt [C. pneumoniae] | |||

| 2.A.1.6 | Metabolite:H+ Symporter (MHS) Family | 1 | 42523790 | 454 | 12 | KgtP [E. coli] |

| 2.A.1.24 | Unknown Major Facilitator-1 (UMF1) Family | 1 | 42522938 | 392 | 11 | YCL038c [S. cerevisiae] |

| 2.A.1.25 | Peptide-Acetyl-Coenzyme A Transporter (PAT) Family | 1 | 42521955 | 447 | 12 | AmpG [E. coli] |

| 2.A.1.30 | Putative Abietane Diterpenoid Transporter (ADT) Family | 1 | 42523759 | 398 | 12 | DitE [P. abietaniphila] |

| 2.A.1.36 | Acriflavin-sensitivity (YnfM) Family | 2 | 42522279 | 394 | 9 | YnfM [E. coli] |

| 42524997 | 408 | 12 | YnfM [E. coli] | |||

| 2.A.1.x | Member of the MFS Superfamily | 3 | 42522316 | 405 | 10 | Putative MFS |

| 42523216 | 418 | 12 | Putative MFS | |||

| 42523082 | 395 | 10 | Putative MFS | |||

| 2.A.2 | Glycoside-Pentoside-Hexuronide (GPH): Cation Symporter Family | 1 | 42524653 | 422 | 10 | MelB [E. coli] |

| 2.A.3 | Amino Acid/Polyamine/Organocation (APC) Superfamily | |||||

| 2.A.3.6 | Archaeal/Bacterial Transporter (ABT) Family | 1 | 42523390 | 412 | 12 | Cat-1 [A. fulgidus] |

| 2.A.4 | Cation Diffusion Facilitator (CDF) Family | 2 | 42521983 | 345 | 6 | YiiP [E. coli] |

| 42523674 | 310 | 5 | CzcD [A. eutrophus] | |||

| 2.A.5 | Zinc (Zn2+)-Iron (Fe2+) Permease (ZIP) Family | 1 | 42524041 | 251 | 7 | ZupT [E. coli] |

| 2.A.6 | RND Superfamily | |||||

| 2.A.6.1 | Heavy Metal Efflux (HME) Family | 1 | 42523684 | 1010 | 9 | CzcA [A. eutrophus] |

| 2.A.6.2 | (Largely Gram-negative Bacterial) Hydrophobe/Amphiphile Efflux-1 (HAE1) Family | 6 | 42522459 | 1032 | 12 | MdtC/YegO [E. coli] |

| 42522562 | 1050 | 10 | MdtC/YegO [E. coli] | |||

| 42522687 | 1033 | 10 | MdtC/YegO [E. coli] | |||

| 42523244 | 1039 | 12 | MdtC/YegO [E. coli] | |||

| 42523286 | 1033 | 11 | MdtC/YegO [E. coli] | |||

| 42524450 | 1070 | 12 | MdtC/YegO [E. coli] | |||

| 2.A.6.7 | (Largely Archaeal Putative) Hydrophobe/Amphiphile Efflux-3 (HAE3) Family | 1 | 42523469 | 1013 | 13 | MJ1562 [M. jannaschii] |

| 2.A.7 | DMT Superfamily | |||||

| 2.A.7.1 | 4 TMS Small Multidrug Resistance (SMR) Family | 2 | 42523246 | 145 | 4 | EmrE [E. coli] |

| 42523933 | 131 | 4 | SugE [E. coli] | |||

| 2.A.7.3 | 10 TMS Drug/Metabolite Exporter (DME) Family | 3 | 42521888 | 295 | 10 | PecM [E. chrysanthemi] |

| 42522043 | 285 | 10 | RhtA [E. coli] | |||

| 42524639 | 298 | 10 | RhtA [E. coli] | |||

| 2.A.7.x | Member of the DMT Superfamily | 2 | 42523696 | 309 | 9 | Putative DMT |

| 42523878 | 311 | 10 | Putative DME [2.A.7.3] | |||

| 2.A.9 | Cytochrome Oxidase Biogenesis (Oxa1) Family | 1 | 42525232 | 539 | 5 | YidC [E. coli] |

| 2.A.17 | Proton-dependent Oligopeptide Transporter (POT) Family | 1 | 42523325 | 451 | 11 | DtpT [L. lactis] |

| 2.A.19 | Ca2+:Cation Antiporter (CaCA) Family | 1 | 42523602 | 371 | 10 | ChaA [E. coli] |

| 2.A.22 | Neurotransmitter:Sodium Symporter (NSS) Family | 1 | 42523422 | 455 | 11 | MJ1319 [M. jannaschii] |

| 2.A.27 | Glutamate:Na+ Symporter (ESS) Family | 1 | 42524043 | 394 | 12 | GltS [E. coli] |

| 2.A.35 | NhaC Na+:H+ Antiporter (NhaC) Family | 1 | 42521884 | 427 | 9 | MleN [B. subtilis] |

| 2.A.37 | Monovalent Cation:Proton Antiporter-2 (CPA2) Family | 5 | 42521965 | 294 | 10 | GrmA [B. subtilis] |

| 42522245 | 650 | 11 | KefC [E. coli] | |||

| 42523556 | 746 | 16 | MagA [Magnetospirillum]+TrkA_C | |||

| 42523635 | 388 | 10 | NhaS3-like [Synechocystis] | |||

| 42523724 | 739 | 16 | GrmA [B. megaterium]+TrkA_C | |||

| 42525048 | 192 | 0 | YheR [E. coli] | |||

| 2.A.46 | Benzoate:H+ Symporter (BenE) Family | 1 | 42521934 | 387 | 12 | BenE [A. calcoaceticus] |

| 2.A.47 | Divalent Anion:Na+ Symporter (DASS) Family | 2 | 42523367 | 488 | 11 | SodiTl [S. oleracea] |

| 42523612 | 612 | 10 | SdrP [Synechocystis] | |||

| 2.A.50 | Glycerol Uptake (GUP) Family | 1 | 42523167 | 470 | 9 | GUP1 [S. cerevisiae] |

| 2.A.51 | Chromate Ion Transporter (CHR) Family | 1 | 42523317 | 378 | 9 | SrpC [Synechococcus] |

| 2.A.58 | Phosphate:Na+ Symporter (PNaS) Family | 1 | 42523679 | 535 | 8 | YjbB [E. coli] |

| 2.A.63 | Monovalent Cation (K+ or Na+):Proton Antiporter-3 (CPA3) Family | 1 | 42523736 | 109 | 3 | MnhG [S. aureus] |

| DNA | NA | MnhF [S. aureus] | ||||

| 42523737 | 112 | 2 | MnhE [S. aureus] | |||

| 42523738 | 486 | 13 | MnhD [S. aureus] | |||

| 42523739 | 98 | 3 | MnhC [S. aureus] | |||

| 42523740 | 853 | 24 | MnhAB [S. aureus] | |||

| 2.A.64 | Twin Arginine Targeting (Tat) Family | 1 | 42523658 | 79 | 1 | TatE [E. coli] |

| 42523995 | 81 | 0 | TatA [E. coli] | |||

| 42525186 | 253 | 6 | TatC [E. coli] | |||

| 42525187 | 118 | 0 | TatB [E. coli] | |||

| 2.A.66 | MOP Superfamily | |||||

| 2.A.66.1 | Multi Antimicrobial Extrusion (MATE) Family | 1 | 42523788 | 404 | 11 | NorM [B. vietnamiensis] |

| 2.A.66.2 | Polysaccharide Transport (PST) Family | 1 | 42523185 | 422 | 12 | MTH347 [M. thermautotrophicus] |

| 2.A.66.4 | Mouse Virulence Factor (MVF) Family | 2 | 42523761 | 520 | 11 | MviN [S. typhimurium] |

| 42522981 | 523 | 12 | MviN [S. typhimurium] | |||

| 2.A.68 | p-Aminobenzoyl-glutamate Transporter (AbgT) Family | 2 | 42524987 | 514 | 12 | MtrF/AbgT |

| 42521870 | 454 | 10 | Putative AtoE | |||

| 2.A.72 | K+ Uptake Permease (KUP) Family | 1 | 42523474 | 669 | 12 | KUP [E. coli] |

| 2.A.85 | The Aromatic Acid Exporter (AraE) Family | 1 | 42524263 | 344 | 8 | YccS [E. coli] |

| 2.C.1 | TonB-ExbB-ExbD/TolA-TolQ-TolR (TonB) Family of Auxiliary Proteins for Energization of Outer Membrane Receptor (OMR)-mediated Active Transport | 6 | 42521812 | 461 | 0 | TolB [E. coli] |

| 42521813 | 286 | 1 | TonB-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42521814 | 138 | 1 | ExbD/TolR [E. coli] | |||

| 42521815 | 245 | 3 | TolQ [E. coli] | |||

| 42522010 | 316 | 1 | TonB-like ? | |||

| 42522032 | 165 | 1 | ExbD/TolR-like ? | |||

| 42522033 | 149 | 1 | ExbD-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42522034 | 248 | 3 | ExbB [E. coli] | |||

| 42522085 | 209 | 3 | TolQ [E. coli] | |||

| 42522086 | 134 | 1 | TolR-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42522223 | 168 | 0 | Pal [E. coli] | |||

| 42522225 | 223 | 0 | YbgF-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42522342 | 295 | 1 | TonB-like ? | |||

| 42522410 | 221 | 3 | TolQ [E. coli] | |||

| 42522411 | 158 | 1 | TolR [E. coli] | |||

| 42522990 | 167 | 1 | ExbD/TolR-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42522991 | 185 | 0 | TolR-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42522992 | 236 | 3 | TolQ-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42523572 | 224 | 1 | YbgF-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42523821 | 175 | 1 | ExbD/TolR-like ? | |||

| 42523822 | 151 | 1 | ExbD-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42523823 | 244 | 3 | ExbB [E. coli] | |||

| 42523907 | 175 | 0 | YbgF-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42524267 | 244 | 0 | TonB-like ? | |||

| 42524795 | 341 | 0 | TolB-like ? | |||

| 42524919 | 209 | 1 | TonB-like [E. coli] | |||

| 42525096 | 471 | 1 | TonB-like ? | |||

| 3.A.1 | ABC Superfamily c | |||||

| 3.A.1.1 | Carbohydrate Uptake Transporter-1 (CUT1) Family | 1 | 42522756 | 347 | 0 | [C] MalK |

| 42522757 | 272 | 6 | [M] MalG2 | |||

| 42522758 | 733 | 7 | [R+M] MalE1+MalF1 | |||

| 3.A.1.2 | Carbohydrate Uptake Transporter-2 (CUT2) Family | 1 | 42522051 | 291 | 8 | [M] |

| 42522052 | 342 | 8 | [M] FrcC-like [R. meliloti] | |||

| 42522053 | 494 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42522054 | 339 | 0 | [R] | |||

| 3.A.1.3 | Polar Amino Acid Uptake Transporter (PAAT) Family | 1 | 42522399 | 247 | 0 | BgtA [C] |

| 42522400 | 247 | 4 | BgtB_C [M] | |||

| 42522401 | 262 | 0 | BgtB_N [R] | |||

| 3.A.1.4 | Hydrophobic Amino Acid Uptake Transporter (HAAT) Family | 1 | 42524744 | 373 | 0 | LivK [R] |

| 42524745 | 300 | 8 | LivH [M] | |||

| 42524746 | 323 | 8 | LivM [M] | |||

| 42524747 | 270 | 0 | LivG [C] | |||

| 42524748 | 237 | 0 | LivF [C] | |||

| 3.A.1.5 | Peptide/Opine/Nickel Uptake Transporter (PepT) Family | 3 | 42521975 | 540 | 0 | DppE [R] |

| 42521976 | 343 | 6 | DppB [M] | |||

| 42521977 | 339 | 6 | DppC [M] | |||

| 42523449 | 487 | 0 | MppA [R] | |||

| 42523651 | 322 | 0 | OppD [C] | |||

| 42523652 | 329 | 0 | OppF [C] | |||

| 42523653 | 564 | 0 | OppA [R] | |||

| 42523654 | 323 | 6 | OppB [M] | |||

| 42523655 | 404 | 6 | OppC [M] | |||

| 42524127 | 274 | 6 | DppC [M] | |||

| 42524128 | 310 | 7 | DppB [M] | |||

| 3.A.1.7 | Phosphate Uptake Transporter (PhoT) Family | 1 | 42523158 | 333 | 0 | PstS-like [R] |

| 42523159 | 312 | 6 | PstC [M] | |||

| 42523160 | 305 | 8 | PstA [M] | |||

| 42523161 | 255 | 0 | PstB [C] | |||

| 3.A.1.9 | Phosphonate Uptake Transporter (PhnT) Family | 1 | 42524492 | 322 | 7 | PhnE [M] |

| 42524493 | 262 | 0 | PhnC [C] | |||

| 42524494 | 297 | 0 | PhnD [R] | |||

| 3.A.1.11 | Polyamine/Opine/Phosphonate Uptake Transporter (POPT) Family | 1 | 42522934 | 344 | 0 | PotD [R] |

| 42522935 | 292 | 0 | PotA [C] | |||

| 42522936 | 277 | 6 | PotB [M] | |||

| 42522937 | 277 | 6 | PotC [M] | |||

| 3.A.1.15 | Manganese/Zinc/Iron Chelate Uptake Transporter (MZT) Family (Similar to 3.A.1.12 and 3.A.1.16) | 1 | 42524734 | 291 | 0 | ZnuA [R] |

| 42524735 | 189 | 0 | ZnuC [C] | |||

| 42524736 | 270 | 7 | ZnuB [M] | |||

| 3.A.1.16 | Nitrate/Nitrite/Cyanate Uptake Transporter (NitT) Family | 1 | 42523495 | 310 | 0 | [R] |

| 42523496 | 253 | 5 | [M] CmpB-like [Synechococcus] | |||

| 42523497 | 266 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 3.A.1.17 | Taurine Uptake Transporter (TauT) Family (Similar to 3.A.1.12 and 3.A.1.16) | 1 | 42524162 | 266 | 0 | TauB [C] |

| 42524163 | 275 | 6 | TauC [M] | |||

| 42524164 | 333 | 1 | TauA [R] | |||

| 3.A.1.19 | Thiamin Uptake Transporter (ThiT) Family (Most similar to 3.A.1.10, 3.A.1.6 and 3.A.1.8 in that order) | 1 | 42522187 | 346 | 1 | ThiB [R] |

| 42522188 | 487 | 11 | ThiP [M] | |||

| 42522189 | 208 | 0 | ThiQ [C] | |||

| 3.A.1.102 | Lipooligosaccharide Exporter (LOSE) Family | 1 | 42521775 | 308 | 0 | NodI [C] |

| 42521776 | 262 | 6 | NodJ [M] | |||

| 3.A.1.106 | Lipid Exporter (LipidE) Family | 3 | 42521794 | 573 | 5 | MsbA [M+C] |

| 42523036 | 588 | 4 | MsbA [M+C] | |||

| 42524487 | 567 | 5 | MsbA [M+C] | |||

| 3.A.1.115 | Na+ Exporter (NatE) Family | 1 | 42523356 | 250 | 0 | [C] |

| 42523357 | 246 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42523358 | 368 | 6 | [M] NatB-like | |||

| 42523359 | 358 | 6 | [M] | |||

| 3.A.1.122 | Macrolide Exporter (MacB) Family | 1 | 42522295 | 650 | 4 | MacB [C+M] |

| 3.A.1.125 | Lipoprotein Translocase (LPT) Family | 2 | 42522999 | 405 | 4 | LolE [M] |

| 42523000 | 220 | 0 | LolD [C] | |||

| 42523263 | 416 | 4 | LolC [M] | |||

| 42524549 | 402 | 4 | LolE [M] | |||

| 42524550 | 231 | 0 | LolD [C] | |||

| 3.A.1.208 | Conjugate Transporter Family (ABCC) | 2 | 42523967 | 597 | 5 | AtMRP2_N [A. thaliana] |

| 42523968 | 620 | 6 | AtMRP2_C [A. thaliana] | |||

| 42524005 | 1228 | 10 | MRP3 [H. sapiens] | |||

| 3.A.1.x | Orphan members of the ABC Superfamily | 15 | 42521819 | 252 | 0 | [C] |

| 42521882 | 251 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3 ?] | |||

| 42521925 | 305 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42521962 | 221 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42521963 | 849 | 10 | [M] [duplicated LolE-like] | |||

| 42522096 | 254 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3; TcyA B. subtilis] | |||

| 42522111 | 273 | 1 | [R] [3.A.1.3; ArtJ E. coli] | |||

| 42522191 | 246 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3 ?] | |||

| 42522255 | 496 | 0 | [R] [duplicated 3.A.1.3 ?] | |||

| 42522275 | 274 | 1 | [R] [3.A.1.3; ArtJ-like E. coli] | |||

| 42522313 | 243 | 1 | [R] [3.A.1.3; ArgT-like E. coli] | |||

| 42522356 | 242 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3 ?] | |||

| 42522414 | 240 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42522416 | 274 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3; GlnH E. coli] | |||

| 42522431 | 296 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.9; PhnD E. coli] | |||

| 42522432 | 247 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42522433 | 253 | 6 | [M] [NosY-like] [PliI ?] | |||

| 42522485 | 252 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42522556 | 603 | 0 | [C+C] | |||

| 42522582 | 314 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42522583 | 257 | 6 | [M] ? | |||

| 42522584 | 511 | 4 | [M] [NA; ABC ?] | |||

| 42522612 | 292 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3 ?] | |||

| 42522628 | 330 | 0 | [r] [3.A.1.10; FutA1 Synechocystis] | |||

| 42522659 | 229 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42522660 | 421 | 3 | [M] [LolE-like] | |||

| 42522753 | 569 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42522767 | 245 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3; HisJ S. typhimurium] | |||

| 42522834 | 285 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3 ?] | |||

| 42522852 | 556 | 0 | [C+C] | |||

| 42522853 | 277 | 5 | [M] [NA; ABC ?] | |||

| 42522868 | 247 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3 ?] | |||

| 42522895 | 582 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.2+3; RbsB E. coli + HisJ S. typhimurium] | |||

| 42522931 | 543 | 0 | [C+C] | |||

| 42522945 | 254 | 1 | [R] [3.A.1.3; ArtJ-like E. coli] | |||

| 42523223 | 248 | 6 | [M] [3.A.1.105] | |||

| 42523224 | 287 | 0 | [C] [3.A.1.105] | |||

| 42523258 | 274 | 6 | [M] [9.B. 11; Tgd1 A. thaliana] | |||

| 42523259 | 236 | 0 | [C] [3.A.5 FtsE-like ATPase] | |||

| 42523260 | 317 | 1 | [R] [Ttg2C] | |||

| 42523261 | 261 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3 ?] | |||

| 42523262 | 265 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3 ?] | |||

| 42523274 | 247 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3; ArgT-like E. coli] | |||

| 42523464 | 237 | 1 | [R] [3.A.1.3 ?] | |||

| 42523514 | 246 | 1 | [R] [3.A.1.3; GlnH-like E. coli] | |||

| 42523547 | 600 | 1 | [R] [duplicated; 3.A.1.2 ?] | |||

| 42523561 | 257 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3; ArgT E. coli] | |||

| 42523595 | 257 | 6 | [M] [3.A.1.102] | |||

| 42523596 | 305 | 0 | [C] [3.A.1.102] | |||

| 42523831 | 267 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.13; ButF S. typhimurium] | |||

| 42523888 | 239 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3 ?] | |||

| 42524071 | 246 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3; CysX E. coli] | |||

| 42524132 | 347 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.2] | |||

| 42524161 | 149 | 4 | [M] [NA; ABC ?] | |||

| 42524193 | 260 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3; TcyA-like B. subtilis] | |||

| 42524262 | 287 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3] | |||

| 42524284 | 254 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3 ?] | |||

| 42524507 | 459 | 1 | [R] [Ttg2C] | |||

| 42524508 | 254 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42524509 | 275 | 5 | [M] [9.B.11; Tgd1 A. thaliana] | |||

| 42524523 | 264 | 4 | [M] [NA; ABC ?] | |||

| 42524770 | 262 | 5 | [M] [9.B.11; Tgd1 A. thaliana] | |||

| 42524771 | 248 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42524772 | 272 | 1 | [R] [Ttg2C] | |||

| 42524780 | 474 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3 ? + SLT] | |||

| 42524915 | 622 | 0 | [C+C] | |||

| 42524918 | 515 | 0 | [C+C] | |||

| 42524922 | 265 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.3; ArtI E. coli] | |||

| 42524935 | 276 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42524936 | 270 | 7 | [M] ? | |||

| 42524937 | 266 | 6 | [M] [NA; ABC ?] | |||

| 42524980 | 554 | 0 | [C+C] | |||

| 42525129 | 258 | 1 | [R] [Ttg2C] | |||

| 42525130 | 239 | 5 | [M] [9.B.11; Tgd1 A. thaliana] | |||

| 42525131 | 259 | 3 | [M] [9.B. 11; Tgd1 A. thaliana] | |||

| 42525132 | 243 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42525133 | 252 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42525140 | 237 | 0 | [C] | |||

| 42525141 | 786 | 9 | [M] ? | |||

| 42525194 | 556 | 0 | [R] [3.A.1.4; ? NatB Synechocystis] | |||

| 3.A.2 | H+ or Na+ translocating F-type, V-type and A-type ATPase (F-ATPase) Superfamily | 1 | 42521659 | 229 | 6 | F0-A |

| 42521660 | 105 | 2 | F0-C | |||

| 42525217 | 140 | 0 | F1-ε | |||

| 42525218 | 468 | 0 | F1-β | |||

| 42525219 | 295 | 0 | F1-γ | |||

| 42525220 | 507 | 0 | F1-α | |||

| 42525221 | 182 | 0 | F1-δ | |||

| 42525222 | 186 | 2 | F0-B | |||

| 42525223 | 144 | 1 | F0-B | |||

| 3.A.3 | P-type ATPase (P-ATPase) Superfamily | 5 | 42522486 | 825 | 9 | pMA1, Ca2+-ATPase |

| 42523248 | 141 | 2 | KdpA_N, K+-ATPase | |||

| 42523249 | 160 | 3 | KdpA_C, K+-ATPase | |||

| 42523682 | 724 | 8 | CopA, Cu2+-ATPase | |||

| 42523748 | 692 | 8 | CopB, Cu2+, Cu+, Ag+ ATPase | |||

| 42524029 | 798 | 8 | CopA, Cu2+-ATPase | |||

| 3.A.5 | General Secretory Pathway (Sec) Family | 1 | 42521801 | 220 | 0 | FtsE |

| 42521895 | 889 | 0 | SecA | |||

| 42522594 | 161 | 2 | SecG | |||

| 42522713 | 402 | 1 | FtsY | |||

| 42523591 | 450 | 0 | Ffh | |||

| 42523691 | 312 | 6 | SecF | |||

| 42523692 | 564 | 5 | SecD | |||

| 42523693 | 117 | 1 | YjaC | |||

| 42524357 | 442 | 10 | SecY | |||

| 42524389 | 125 | 3 | SecE | |||

| 3.A.6 | Type III (Virulence-related) Secretory Pathway (IIISP) Family | 1 | 42524690 | 699 | 7 | FlhA |

| 42524691 | 353 | 3 | FlhB | |||

| 42524692 | 259 | 7 | FliR | |||

| 42524693 | 90 | 2 | FliQ | |||

| 42524694 | 252 | 5 | FliP | |||

| 42524695 | 224 | 1 | FliO | |||

| 42524696 | 122 | 0 | FliN | |||

| 42524697 | 333 | 0 | FliM | |||

| 42524760 | 442 | 0 | FliI | |||

| 42524761 | 261 | 0 | FliH | |||

| 42524763 | 549 | 2 | FliF | |||

| 3.A.10 | H+ translocating Pyrophosphatase (H+PPase) Family | 1 | 42523211 | 688 | 16 | V-PPase [A. thaliana] |

| 3.A.12 | Septal DNA Translocator (S-DNA-T) Family | 1 | 42521689 | 797 | 5 | SpoIIIE of [B. subtilis] |

| 3.A.15 | Outer Membrane Protein Secreting Main Terminal Branch (MTB) Family | 2 | 42522434 | 259 | 6 | PilD |

| 42522813 | 190 | 1 | PilA | |||

| 42523016 | 566 | 0 | PilB | |||

| 42523017 | 347 | 0 | PilT | |||

| 42523018 | 405 | 3 | PilC | |||

| 42523092 | 411 | 0 | PulK ? | |||

| 42523093 | 294 | 1 | PulJ ? | |||

| 42523094 | 166 | 1 | PulI ? | |||

| 42523095 | 194 | 1 | FimT ? /PulH ? | |||

| 42523096 | 136 | 1 | PulG | |||

| 42523100 | 405 | 3 | PulF | |||

| 42523101 | 564 | 0 | PulE | |||

| 42523102 | 765 | 0 | PulD [1.B.22] | |||

| 42523103 | 304 | 1 | PulC | |||

| 42523986 | 289 | 1 | FimU ? | |||

| 42524677 | 433 | 0 | PilQ-like [1.B.22] | |||

| 42525175 | 367 | 0 | PilU/PilT-like | |||

| 3.B.1 (?) | Na+ transporting Carboxylic Acid Decarboxylase (NaT-DC) Family | 42524925 | 127 | 0 | Gamma [A. fermentans] | |

| 42524928 | 535 | 0 | Alpha [P. abyssi] | |||

| 42525181 | 522 | 0 | Alpha [V. parvula] | |||

| 42525183 | 175 | 0 | Gamma [P. abyssi] | |||

| 3.D.1 | Proton-translocating NADH Dehydrogenase (NDH) Family | 1 | 42524471 | 174 | 1 | Nqo9 |

| 42524472 | 504 | 0 | Nqo3 | |||

| 42524473 | 431 | 0 | Nqo1 | |||

| 42524474 | 159 | 0 | Nqo2 | |||

| 42524475 | 560 | 0 | Nqo5-Nqo4 | |||

| 42524476 | 187 | 0 | Nqo6 | |||

| 42525207 | 486 | 12 | Nqo14 | |||

| 42525208 | 517 | 13 | Nqo13 | |||

| 42525209 | 643 | 16 | Nqo12 | |||

| 42525210 | 107 | 3 | Nqo11 | |||

| 42525211 | 178 | 5 | Nqo10 | |||

| 42525212 | 385 | 8 | Nqo8 | |||

| 42525213 | 127 | 3 | Nqo7 | |||

| 3.D.4 | Proton-translocating Cytochrome Oxidase (COX) Superfamily | 3 | 42521909 | 318 | 2 | Cox2 |

| 42521910 | 535 | 12 | Cox1 | |||

| 42521911 | 221 | 5 | Cox3 | |||

| 42521912 | 112 | 3 | Cox4 | |||

| 42521913 | 292 | 8 | CoxX | |||

| 42524021 | 441 | 12 | Cox1-like | |||

| 42524022 | 215 | 0 | Cox2-like | |||

| 42524031 | 706 | 13 | CcoN-CcoO | |||

| 5.A.1 | Disulfide Bond Oxidoreductase D (DsbD) Family | 1 | 42524631 | 653 | 9 | DsbD [E. coli] |

| 5.A.3 | The Prokaryotic Molybdopterin-containing Oxidoreductase (PMO) Family | 1 | 42523112 | 1033 | 0 | DmsAB [H. salinarium] |

| 42523113 | 453 | 10 | DmsC [H. salinarium] | |||

| 42524233 | 151 | 1 | TorC_N [E. coli] | |||

| 8.A.1 | Membrane Fusion Protein (MFP) Family | 42522294 | 321 | 1 | MacA [for 3.A.1.122] | |

| 42523355 | 204 | 0 | MFP [for 3.A.1.115] | |||

| 42522395 | 582 | 1 | Probably with [NA SapB-like 9.B.20] | |||

| 42525142 | 297 | 1 | AcrA-like [for 3.A.1.x] | |||

| 8.A.21 | Epithelial Na+ Channel (ENaC) Family | 42523755 | 250 | 0 | Stomatin homolog [P. horikoshii] | |

| 42523756 | 424 | 5 | NfeD protease [P. horikoshii] | |||

| 42524093 | 307 | 1 | Stomatin homolog-like protein | |||

| 9.A.8 | Ferrous Iron Uptake (FeoB) Family | 1 | 42523346 | 76 | 0 | [FeoA] FeoB2_N [P. gingivalis] |

| 42523347 | 638 | 8 | FeoB [L. biflexa] | |||

| 9.A.19 | Mg2+ Transporter-E (MgtE) Family | 1 | 42523969 | 447 | 4 | MgtE [B. firmus] |

| 9.A.23 | Ferroportin (FP) Family | 1 | 42523494 | 440 | 8 | Fpn1 [M. musculus] Putative MFS? |

| 9.B.3 | Putative Bacterial Murein Precursor Exporter (MPE) Family | 2 | 42523896 | 374 | 9 | RodA [E. coli] |

| 42524580 | 380 | 9 | FtsW [E. coli] | |||

| 9.B.17 | Putative Fatty Acid Transporter (FAT) Family | 42521902 | 498 | 0 | FadD [E. coli] | |

| 42522110 | 562 | 0 | CaiC [E. coli] | |||

| 42522828 | 645 | 0 | CaiC [E. coli] | |||

| 42523290 | 554 | 0 | FadD [E. coli] | |||

| 42524534 | 593 | 0 | FadD [E. coli] | |||

| 42524536 | 805 | 0 | X+FadD [E. coli] | |||

| 9.B.22 | Putative Permease (PerM) Family | 2 | 42523616 | 345 | 7 | Yct2 [B. subtilis] |

| 42523150 | 371 | 8 | PerM-like ? [E. coli] | |||

| 9.B.26 | PF27 (PF27) Family | 2 | 42523213 | 90 | 2 | Y615-like [C-half] |

| 42524601 | 183 | 5 | Y615 [Synechocystis] | |||

| 9.B.27 | YdjX-Z (YdjX-Z) Family | 1 | 42521725 | 224 | 4 | YdjZ [E. coli] |

| 9.B.30 | Hly III (Hly III) Family | 2 | 42522243 | 215 | 7 | HlyIII [B. cereus] |

| 42525120 | 208 | 7 | HlyIII [B. cereus] | |||

| 9.B.37 | HlyC/CorC (HCC) Family | 2 | 42522543 | 346 | 3 | YrkA [B. subtilis] |

| 42523633 | 343 | 3 | YrkA [B. subtilis] | |||

| 9.B.53 ? | Unknown IT-6 (UIT6) Family | 1 | 42524007 | 429 | 12 | Putative transporter ? [L. interrogans] |

| 9.B.63 | 9 TMS Putative Metabolite Efflux (9-PME) Family | 1 | 42522953 | 325 | 8 | YeiH [E. coli] |

Proteins of certain families are known to function either as part of multi-component transport systems or are accessory proteins. Therefore this information is considered when calculating the number of transport systems.

The numbers of putative α-helical transmembrane segments (TMSs) were calculated using the TMHMM program. Unfortunately, in the case of outer membrane porins (TC #1.B), the numbers do not reflect the numbers of β-strands and therefore are of limited value.

The various protein components of ABC transporters are labeled as [M]: Integral membrane protein, [C]: Cytoplasmic ATP-hydrolyzing protein, and [R]: Extracytoplasmic (periplasmic) solute-binding receptor. Duplication of domains (e.g., [C+C]) or fusion of two or more protein domains (e.g., [R+M]) are also indicated.

B. bacteriovorus possesses five mechanosensitive channels, one of the MscL-type (TC #1.A.22) and four of the MscS-type (TC #1.A.23). Both types of channels are known to function in hypoosmotic stress adaptation [58]. Only one of these five channel proteins had been discussed previously [11] although the NCBI Genbank records do include annotations noting that these proteins are putative mechanosensitive ion channels.

As reported previously [11], B. bacteriovorus encodes 3 MotA and 3 MotB homologues (TC #1.A.30.1). These occur within three operons that each contains a single motA and a single motB gene. This observation is surprising since B. bacteriovorus encodes only a single flagellum. Possibly the three flagellar “torque generators” act on a single flagellum under different conditions. For example, for swimming vs. swarming motility as is the case of Bacillus subtilis [59,60]. However, these Mot proteins are distantly related to gliding motility genes in Myxococcus xanthus [61], and gliding motility may be a characteristic of B. bacteriovorus [11]. One or more of these MotAB pairs may therefore function to energize gliding motility rather than flagellar rotation.

Finally, B. bacteriovorus has a single divalent metal ion channel of the MIT or CorA family (TC #1.A.35). CorA family members can be specific for a single divalent cation or can allow entry of several [62]. This homologue may provide a primary mechanism for divalent cation (Mg2+, Co2+, etc.) uptake in this organism.

Outer Membrane Porins (TC #1.B)

B. bacteriovorus has a fair complement of outer membrane β-structured porins. These include a single member of the 16 TMS sugar porin family (TC #1.B.3), 4 paralogues of the 8 TMS OmpA-type porin family (TC #1.B.6) and two members of the 12 TMS Tsx nucleoside-specific porin family (TC #1.B.10). Four outer membrane receptors (TC #1.B.14) probably function in the energy-dependent uptake of Fe-siderophore complexes (3 systems) and vitamin B12 (1 system). There are also seven outer membrane factors (TC #1.B.17) that presumably function in conjunction with inner membrane efflux pumps. One of these resembles PtrF of E. coli and probably acts with an ABC-type protease exporter; a second most closely resembles NodT2 and may therefore catalyze oligosaccharide export; several others probably act with RND-type drug efflux pumps. TolC of E. coli can function with multiple transporters from different families, and three of the OMF family members in B. bacteriovorus proved most similar to TolC. Consequently, these proteins may be multifunctional. Surprisingly, we could identify only four membrane fusion proteins (MFP, TC #8.A.1) [63]. These proteins probably function with ABC- (3) and RND-type (1) drug exporters. All MFPs characterized to date function with a single efflux transporter, so at least 7 might be expected to be present. Since these proteins are sequence divergent, some MFPs encoded in the B. bacteriovorus genome may not have been identified by our current search and annotation techniques.

Two outer membrane secretins (TC #1.B.22) were found. One, a PilQ homologue, may function as a “porthole” in the export of type IV pilus subunits [64,65]. The other, an XcpQ homologue, is likely to serve as the porthole for a type II protein secretion system of the main terminal branch [66,67].

B. bacteriovorus has four homologues of E. coli YaeT (TC #1.B.33) and one homologue of E. coli Imp (OstA). It also has one homologue of YfiO and two of YfgL (none of NlpB) [68]. These E. coli proteins are known to function as a complex for the assembly and insertion of outer membrane macromolecules, proteins, lipids and/or lipopolysaccharides [68]. Other subunits of the E. coli complex may exist but have not yet been identified. One such candidate is encoded by a gene in an operon that also encodes several homologues of other constituents of the E. coli outer membrane biogenesis complex. It seems clear that B. bacteriovorus assembles its outer membrane as does E. coli. However, the presence of four YaeT homologues and two YfgL homologues suggests a level of complexity greater than observed for E. coli. There may be four distinct systems corresponding to the four YaeT homologues, and these may share the other components of these systems. Alternatively, more than one YaeT homologue may participate in the formation of a single complex. Interestingly, B. bacteriovorus has a LolA-like outer membrane protein that may function in lipoprotein export [11].

Finally B. bacteriovorus encodes a single holin of the LrgA family (TC #1.E.14), not discussed previously [11], although the Genbank record does contain annotation suggesting homology to the LrgA family. This protein is encoded by a gene that is downstream of and within the same operon as a putative autolysin, a murine hydrolase. It would seem that B. bacteriovorus encodes a chromosomal holin/autolysin system that may function in programmed cell death [69]. A penicillin-binding protein, possibly also involved in cell wall metabolism, is encoded within the same operon.

Secondary Carriers (TC #2.A)

B. bacteriovorus has substantial representation of transporters of the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS, TC #2.A.1). These include 6 drug exporters of the DHA1 family (TC #2.A.1.2) and two sequence divergent members of the OPA family (TC #2.A.1.4) that may function in sugar-phosphate:inorganic phosphate antiport. One member of the MFS (TC #2.A.1.6) shows greatest sequence similarity to the KgtP α-ketoglutarate uptake transporter of E. coli (see TCDB). Two more show greatest similarity with a putative acriflavine uptake transporter (TC # 2.A.1.36). Such systems probably have some other aromatic compounds as their natural substrates. One putative MFS transporter closely resembles the AmpG transporter of E. coli (TC #2.A.1.25) which takes up cell wall degradation products [70,71]. Three MFS members in B. bacteriovorus could not be assigned a substrate type due to their low BLAST scores with functionally characterized transporters. They may be members of uncharacterized families not yet in TCDB.

Some other families in TCDB have been shown to be distantly related to the MFS [72,73,74]. Of these, B. bacteriovorus has one member in the GPH family (TC #2.A.2) of glycoside permeases which might be a melibiose uptake system, and one member of the POT family (TC #2.A.17) of peptide uptake systems. The presence of these two transporters expands the limited repertoire of transporters B. bacteriovorus has for taking up sugars and amino acid derivatives. A single member of the APC superfamily (TC #2.A.3) of transporters for amino acids and their derivatives is present in B. bacteriovorus, fewer than in most bacteria with a genome of comparable size. This transporter is a member of the ABT family (TC #2.A.3.6) for which no functionally characterized members are available.

Two members of the Cation Diffusion Facilitator (CDF) family (TC #2.A.4) are also present. CDF carriers function in prokaryotes as heavy metal (Co2+, Cd2+, Zn2+, Ni2+, Cu2+ and Hg2+) efflux pumps probably using a Me2+/H+ antiport mechanism [75,76]. These pumps can exhibit broad or narrow specificities, so the two CDF carriers in B. bacteriovorus may be a broad and a narrow specificity system like the two proteins in TCDB (YiiP and CzcD, respectively) that they most closely resemble.

A single member of the ZIP family (TC #2.A.5) of heavy metal uptake carriers occurs in B. bacteriovorus. These carriers can be Zn2+-specific or broad specificity (Fe2+, Co2+, Mn2+, etc.) uptake systems. The B. bacteriovorus homologue most resembles ZupT, a broad specificity system of E. coli [77].

Three families within the RND superfamily (TC #2.A.6) are represented in B. bacteriovorus. The first family is the heavy metal efflux (HME) family (TC #2.A.6.1). The single B. bacteriovorus homologue in this family is most similar to the CzcA protein of Ralstonia eutropha, a Co2+, Zn2+, Cd2+ efflux system. The second family is the Hydrophobe/Amphiphile Exporter (HAE1) family of drug efflux pumps (TC #2.A.6.2). Six of these paralogues are present in B. bacteriovorus. All of them most closely resemble MdtC (YegO) of E. coli, a broad specificity drug/detergent/organic solvent/lipid exporter [78]. These systems might protect the parasite against defense mechanisms of the host bacterium. The last B. bacteriovorus RND homologue is a member of the mostly archaeal HAE3 family (TC #2.A.6.7) which is still poorly characterized.

Within the Drug/Metabolite Transporter (DMT) superfamily (TC #2.A.7) are two members of the SMR family (TC #2.A.7.1) of small multidrug resistance systems. One most closely resembles the E. coli EmrE broad specificity cationic drug exporter, while the other resembles the E. coli SugE narrow specificity cationic drug exporter [44,79]. Three members of the DME family (TC #2.A.7.3) are probably metabolite efflux pumps. Two of these most closely resemble the RhtA protein of E. coli which is a threonine/homoserine exporter that may also be able to accommodate other semipolar amino acids [80]. Two more distantly related putative 10 TMS members of the DMT superfamily could not be assigned membership to an established family within the DMT superfamily. They may be members of new families.

B. bacteriovorus encodes a single Ca2+:cation antiporter of the CaCA family (TC #2.A.19). All characterized members of this family function in Ca2+ extrusion from the cytoplasm using a monovalent cation antiport mechanism. Therefore, this is likely to be its function in B. bacteriovorus. Prokaryotic members of the NSS family (TC #2.A.22) are amino acid uptake systems, and the one from B. bacteriovorus most resembles the tryptophan uptake system of Symbiobacterium thermophilum, TnaT [81]. There is also a single member of the glutamate:sodium symporter (ESS) family (TC #2.A.27) represented in B. bacteriovorus, a protein resembling GltS of E. coli which transports both D- and L-glutamate as well as various glutamate derivatives.

B. bacteriovorus encodes within its genome many putative cation:proton antiporters, one of the NhaC family (TC #2.A.35). NhaC-type systems can function as Na+:H+ antiporters or malate • 2H+:lactate • Na+ antiporters [82,83]. Thus, members of this family may merely act as cation exchangers, but they may also be capable of electroneutral transport of organic anions.

Five members of the CPA2 family (TC #2.A.37) of monovalent cation transporters are encoded within the B. bacteriovorus genome, and they most closely match four different transporters in TCDB. Two resemble Bacillus GrmA, a spore germination protein of unknown transport specificity, which, however, closely resembles the GerN Na+/H+-K+ antiporter of Bacillus cereus; the second resembles the KefC glutathione-regulated K+ efflux protein of E. coli; the third looks like the MagA iron-regulated transporter of a magnetotactic bacterium; and the fourth is like NhaS3 of Synechocystis, a Na+:H+ antiporter. It seems likely that each of these B. bacteriovorus homologues will prove to catalyze a different reaction, but always acting on monovalent cations.

Two additional monovalent cation transporters are found within the B. bacteriovorus genome. The first is a multicomponent Na+ or K+:H+ antiporter of the CPA3 family (TC #2.A.63). All seven characteristic constituents of these systems were identified in B. bacteriovorus although only 6 had been annotated. One of them (GI:42523740) is a fusion protein of two previously recognized subunits of these systems. The system in B. bacteriovorus most closely resembles the Na+:H+ antiporter of the Gram-positive bacterium, Staphylococcus aureus, rather than the K+:H+ antiporter of the Gram-negative bacterium, Rhizobium meliloti [50,84]. It is therefore likely that the B. bacteriovorus homologue is a Na+:H+ antiporter. These complex Na+:H+ antiporters, with subunits homologous to subunits in NADH dehydrogenase, are possibly dependent on NADH2. Such a Na+:H+ antiporter has not been characterized in a Gram-negative bacterium before.

The K+ uptake (KUP) permease (TC #2.A.72) of E. coli may use a K+:H+ symport mechanism, allowing a 106-fold accumulation of K+ over the external medium [85,86]. This protein has an N-terminal 12 TMS topology (residues 1-450) followed by a hydrophilic domain of unknown function (residues 450-622). The same structure is observed for the B. bacteriovorus protein that it closely resembles. This suggests that the B. bacteriovorus homologue may function, and may be regulated, like the E. coli homologue.

Four members of the MOP superfamily (TC #2.A.66), from three different constituent families, were identified in B. bacteriovorus. One is probably an MDR efflux pump of the MATE family (TC #2.A.66.1) of drug:Na+ antiporters; the second is likely to be a polysaccharide exporter of the PST family (TC #2.A.66.2); and the third and fourth are members of the “Mouse Virulence family” (TC #2.A.66.4) with no functionally characterized member.

B. bacteriovorus encodes one or two members of each of several small solute carrier families. One resembles the BenE benzoate:H+ symporter of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus (TC #2.A.46) [87]; a second and third are members of the DASS family (TC #2.A.47) of divalent anion:Na+ symporters within the IT superfamily [88]; the fourth is a full-sized chromate/sulfate transporter of the CHR family (TC #2.A.51) [89,90,91,92]; the fifth is a putative phosphate:Na+ uptake symporter of the PNaS family (TC #2.A.58); the sixth is a member of the ArAE family (TC #2.A.85) which may export one or more aromatic acids [93] and functions with a Membrane Fusion Protein (TC #8.A.1) [94]; and the seventh and eighth are putative AbgT family (TC #2.A.68) homologues which might be peptide, p-aminobenzoyl-glutamate and/or drug uptake porters. One of these proteins (GI:42521870) had been annotated as a short chain fatty acid transporter like AtoE of E. coli (TC #2.A.73.1.1).

Two remaining pmf-dependent systems listed in Table 2 under the 2.A category of TCDB are involved in protein trafficking. One resembles the YidC protein of the Oxa1 family (TC #2.A.9). This protein probably catalyzes protein insertion into the cytoplasmic membrane [95]. The other is the Twin Arginine Targeting and Translocation (TAT) protein secretion system (TC #2.A.69) [96]. All bacteria with a Tat system have at least 1 TatC constituent and at least 1 TatA constituent. E. coli and B. bacteriovorus have three TatA homologues, TatA, TatB and TatE [96]. B. bacteriovorus has a single TatC as does E. coli, and it is encoded within a bicistronic operon that also encodes a TatB homologue. Unlike the gene arrangement in E. coli, TatA and TatE are both encoded elsewhere on the chromosome.

Outer Membrane Receptor (OMR) Energizers for Active Transport Across the Outer Membrane

Category 2.C.1 in TCDB includes a single family of multicomponent, pmf-dependent transporter energizers. Two such systems are present in E. coli, and at least three constituents show sequence similarity between these two systems. The TonB/ExbB/ExbD system shows sequences and functions similar to the TolA/TolQ/TolR system. The latter system has additional auxiliary proteins called Pal (a lipoprotein), TolB and YbgF. B. bacteriovorus encodes at least one complete TolA-type system with minimally one copy of each of the recognized E. coli auxiliary constituents (6 non-homologous proteins). However, encoded in this B. bacteriovorus genome are 6 TonB/TolA homologues, six ExbB/TolQ-like constituents, nine ExbD/TolR-like proteins, three YbgF homologues, two TolB homologues and one Pal lipoprotein. Operon analyses revealed that one set of TolA, TolB, TolQ, and TolR are encoded together in a single operon. Five separate TolQ/TolR pairs are encoded in five other distinct operons, and three of these also encode an extra ExbD/TolR-like homologue. Pal, TolB and YbgF homologues, present in 1, 2 and 3 copies, respectively (Table 2), are encoded at sites distant from each other and the other Tol genes, with the single exception noted above where a TolB homologue is encoded within an operon with TolA, TolQ and TolR homologues.

The operon structures were examined in the proximity of these genes. In brief, there are four OMR receptors in Bba; three are probably specific for complex iron; and one is specific for vitamin B12. Six TolQ/TolR homologues are present, but there are fewer TolB, Pal and YbgF homologues. It is probable that these last mentioned proteins either can function with multiple co-transcribed pairs of TolQR proteins or are not required. This might suggest that each OMR interacts with its own TolQ/R pair, any of which can use the same TolB/Pal/YbgF complex. It is interesting to recall that TolQ/R homologues (MotA/B homologues) may function in adventurous gliding motility in Myxococcus xanthus [61](see acc. #AAO22857). The possibility that B. bacteriovorus is capable of gliding motility using type four pili has not been demonstrated [11].

Primary Active Transporters – ABC Superfamily (TC #3.A.1)

The ABC superfamily of ATP-driven transporters is the largest transporter superfamily represented in the B. bacteriovorus genome. Fourteen potential uptake systems and 20 potential efflux systems were identified, and all of these systems appear to be complete, having all of the expected constituents. One maltose-type system of the CUT1 family (TC #3.A.1.1) and one ribose-type system of the CUT2 family (TC #3.A.1.2) were identified. In the former system, the MalE binding protein and the MalF protein constituent are fused in a single polypeptide chain derived from a single fused gene, an unusual arrangement. In the latter system, one cytoplasmic (C) ATP-hydrolyzing protein (RbsA), one periplasmic receptor (R) and two membrane (M) constituents were found. This arrangement resembles that of a minority of CUT-2 transporters. Others have a single membrane constituent and thus have only three constituents, one C, one M and one R. The E. coli ribose system has the equivalent four gene products, RsbABCD, where A is the cytoplasmic ATPase, B is the periplasmic receptor, and C and D are the channel-forming membrane proteins.

One system for uptake of polar amino acids (PAAT family, TC #3.A.1.3) and one system for uptake of hydrophobic amino acids (HAAT family, TC #3.A.1.4) were found. Both systems appear to be complete with three constituents in the PAAT family system (1R, 1C and 1M) and five in the HAAT family system (1R, 2Cs and 2Ms).

There is a complete oligopeptide uptake system (TC #3.A.1.5) like that in E. coli with two Rs, two Cs and two Ms. However, a strange situation is observed for the dipeptide (Dpp) system where there is a single receptor (R) and two pairs of membrane proteins (M) but no ATPase (C). Possibly these two systems use the sequence similar OppD and OppF to energize transport. Complete ABC uptake transporters specific for (1) phosphate (resembling PstABC/PstS of E. coli; 4 constituents; TC #3.A.1.7), (2) phosphonates (most like PhnCDE of E. coli; 3 constituents; TC #3.A.1.9), (3) polyamines (PotABCD of E. coli; 4 constituents; TC #3.A.1.11), (4) zinc (ZnuABC of E. coli; 3 constituents; TC #3.A.1.15), (5) inorganic anions (nitrate, nitrite, cyanide and bicarbonate; 3 constituents; TC #3.A.1.16), taurine (3 constituents; TC #3.A.1.17), and (6) thiamin (3 constituents; TC #3.A.1.19) were found.

ABC efflux systems include (1) a single system specific for lipooligosaccharides (2 constituents; TC #3.A.1.102), (2) three systems specific for lipids and/or drugs (one constituent each; TC #3.A.1.106), (3) either one 4-component or two 2-component Na+ exporter(s) (2 constituents each; TC #3.A.1.115), (4) a macrolide exporter (1 constituent; TC #3.A.1.122), (5) two probable lipoprotein exporters (2 or 3 constituents each; TC #3.A.1.125), and (6) two eukaryotic-like MDR pumps (TC #3.A.1.208), one resembling the plant AtMRP2 system and the other resembling the human MRP3 system. There are also about a dozen functionally unassigned ABC systems or orphan proteins. We have made functional predictions for some of these proteins when warranted (see Table 2). The Genbank records also include annotations of recognizable domains for many of these proteins.

Primary Active Transporters – Other Cation-transporting ATPases

B. bacteriovorus has one complete H+-translocating F-type ATPase (TC #3.A.2) and one H+-translocating pyrophosphatase (TC #3.A.10). Both enzymes can reversibly synthesize pyrophosphate bonds using the proton electrochemical gradient (the proton motive force, pmf) as the driving force. B. bacteriovorus also has five P-type ATPases (TC #3.A.3), one likely to be specific for Ca2+ (efflux), one for K+ (uptake), and three heavy metal systems that could be either uptake or efflux systems. No other cation-translocating ATPases appear to be encoded within the B. bacteriovorus genome.

Primary Active Transporters – ATP-dependent Protein Secretion Systems

As reported previously [11], B. bacteriovorus has a complete (11 component) general secretory (Sec) system (TC #3.A.5) including SecYEG, SecA, SecDF, FtsY and Ffh, YjaC, the 4.5 S RNA and FtsE. A very sequence-divergent FtsX was also identified (see below). B. bacteriovorus has a complete (11 component) flagellar protein export system (TC #3.A.6) [11] and possesses a single member of the septal DNA translocator (S-DNA-T) family (TC #3.A.12), essential for DNA translocation after septum formation in many bacteria. This protein may be required to complete DNA translocation after synchronous cell division of B. bacteriovorus snakes (phase 6 in the developmental cycle) (see Introduction).

B. bacteriovorus has protein constituents resembling those of two related types of outer membrane protein secretion systems (TC #3.A.15). One of these is the type II protein secretion system or main terminal branch (MTB), like the PulC-O,S system found in Klebsiella pneumoniae (14 constituents) [67], and the other is the pilin secretion/fimbrial assembly system like the PilA-EQTU FimTU system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (10 constituents) [97,98]. The system(s) found in B. bacteriovorus has(have) at least 13 constituents, 7 most closely resembling the Pul system, and 6 most closely resembling the Pil system. However, there are many other pil (pilus) and fim (fimbrium) genes present on the B. bacteriovorus chromosome. Rendulic et al. [11] suggested that these proteins comprise a single system, a Pil-type rather than an MTB-type system. If, as proposed, B. bacteriovorus has a type 4 pilus-driven system for passage through the host cell envelope, then the suggestion that it is a Pil-type system is valid. Indeed, Schwudke et al. [99] have shown that a pilus gene, flp1, shows increased expression in the attack phase of Bba, compared to the intracellular replication phase. However, it is known that B. bacteriovorus secretes many proteins across its two-membrane envelope, and consequently, a Pul-type system would be expected to be useful. The nine pul genes in B. bacteriovorus occur within two operons, and these are distant in sequence from any of the pil genes recognized using TC-BLAST [36]. Other pil annotated genes not listed in Table 2 are present in the B. bacteriovorus genome, but these genes are not homologous to genes encoding the proteins of the P. aeruginosa pil system in TCDB (TC #3.A.15.2.1). They also localized to regions of the chromosome distant from the two pil operons in B. bacteriovorus that encode five of the pil genes listed in Table 3. On a purely bioinformatic basis, it is difficult to distinguish the Pul-from the Pil-type systems with certainty. However, based on their degrees of sequence similarity, we propose that B. bacteriovorus has both a complete Pil biogenesis system and a functional Pul-type (type II) protein secretion system.

Table 3.

Unusual compositions of protein complexes in Bba.

| Complex | Component | # of Homologues in Bba | # of Homologues in E. coli |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Bacterial Motor Complexes | |||

| MotA | 3 | 1 | |

| MotB | 3 | 1 | |

| B. OMR Energizers | |||

| TolA/TonB | 6 | 2 | |

| TolQ/ExbB (like MotA) | 6 | 2 | |

| TolR/ExbD (like MotB) | 9 | 2 | |

| TolB | 2 | 1 | |

| Pal | 1 | 1 | |

| YbgF | 3 | 1 | |

| C. Outer Membrane Assembly Complex | |||

| YaeT | 4 | 2 | |

| OstA-L | 1 | 1 | |

| OstA-S | 0 | 1 | |

| YfgL | 2 | 1 | |

| OfiO | 1 | 1 | |

| NlpB | 0 | 1 |

Many prokaryotes have Na+-transporting organic acid decarboxylases (TC #3.B.1) which include α-, β- and γ-subunits [100,101]. B. bacteriovorus has two copies of both the α- and γ-subunits, but we could not identify a β-subunit. The β-subunit is the actual transporter, while α is the decarboxylase (often present without β), and γ, a Zn2+-binding protein of catalytic importance [102,103] is thought to be the linker connecting α and β. The absence of a recognizable β leaves the question open as to whether B. bacteriovorus can couple decarboxylation to Na+ expulsion.

Primary Active Transporters – Cation-translocating Electron Transfer Complexes

Many bacteria possess Na+-translocating NADH dehydrogenase complexes of 14 dissimilar subunits [104,105,106]. In B. bacteriovorus, 13 proteins comprise the NADH dehydrogenase (TC #3.D.1), encoded within two operons. One of the 13 proteins is a fusion protein (Nqo5-Nqo4). Thus, the system is complete and is presumed to be functional. B. bacteriovorus also has a complete proton pumping cytochrome oxidase complex (TC #3.D.4) with all five expected proteins (Cox1-4 and X) encoded within a single operon. Surprisingly, it also has several homologues of cytochrome oxidase subunits that map elsewhere on the chromosome. A Cox1-like homologue and a Cox2-like homologue are encoded within a single operon and show low sequence similarity to the Cox subunits. They have high sequence identity with the two subunits of nitric oxide reductases [107,108], and therefore presumably serve this function. These enzyme complexes may be capable of coupling proton export to electron flow [107].

Transmembrane Electron Flow Carriers (TC #5.A)

B. bacteriovorus possesses two transmembrane electron flow systems that can influence cellular energetics. One is disulfide bond oxidoreductase D (DsbD; TC #5.A.1) in which electrons from an electron donor such as NADH in the cytoplasm are transferred sequentially via thioredoxin reductase, thioredoxin and DsbD to a periplasmic disulfide-containing protein electron acceptor. Several such periplasmic proteins (DsbC, DsbE and DsbG) can be reduced via the DsbD pathway, and some of them can further reduce other disulfide-containing periplasmic proteins in Gram-negative bacteria [109]. The DsbD pathway in B. bacteriovorus undoubtedly facilitates proper folding of and disulfide bond formation in periplasmic proteins as is the case for E. coli [110,111].

The second transmembrane electron flow carrier is a single member of the Prokaryotic Molybdopterin-containing Oxidoreductase (PMO) family (TC #5.A.3), probably a dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) oxidoreductase. One large protein (1033 aas) is a DmsAB fusion protein including the equivalent of the α- and β-subunits while the other is a DmsC subunit (the γ-subunit) [112,113]. Both proteins show greatest sequence similarity with an archaeal enzyme in TCDB (Table 2).

(Putative) Transporters of Unknown Function or Mechanism

In the 9A category of incompletely characterized transporters, we find one FeoAB iron uptake system (TC #9.A.8), one MgtE magnesium uptake porter (TC #9.A.19), and one putative iron transporter of the Ferroportin family (TC #9.A.23), as reported previously [11]. Our preliminary analyses suggest that this last B. bacteriovorus protein may be distantly related to members of the Major Facilitator Superfamily in agreement with the Genbank annotation.

In the 9B series of putative permeases, we find two homologues of Bacterial Murein Precursor Exporters of the MPE family (TC #9.B.30) which are found in many, if not all, bacteria. These porters probably serve the function of exporting precursors essential for bacterial cell wall synthesis [114,115]. Members of the Putative Fatty Acid Transporter family (TC #9.B.17) are acyl CoA synthetases that may in some cases function in fatty acid uptake coupled to esterification with cytoplasmic coenzyme A [116,117,118,119].

B. bacteriovorus encodes four potential hemolysins that could function in host cell lysis or pore formation in the cytoplasmic membrane. The two members of the HlyIII family (TC #9.B.30) are homologous to the B. cereus hemolysin III [120,121]. The two members of the HlyC/CorC family (TC #9.B.37) include one protein believed to be a hemolysin [122] and one protein believed to be a component (CorB) of the Ca2+/Mg2+ uptake transporter [123]. All proteins that show homology with members of the 9B class are homologous to TC entries of unestablished functions (Table 2).

Updated annotations and distant homologues of established transporters

Table S1 on our website (http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/~msaier/supmat/Bba) lists the proteins originally annotated as ABC-type proteins (8) or permeases (10) for which we now suggest new annotations. In addition to identifying the proteins and providing the original annotations, this table presents the protein sizes and the predicted numbers of TMSs. In some cases where we suspected erroneous annotations, we noted that several homologues in the NCBI database also appeared to be annotated in the same way, thus providing an explanation for discrepancies noted in this analysis. This allowed us to identify erroneous annotations in the current databases as well as surprising examples of gene overlap in the B. bacteriovorus genome. These findings are described in our website (http://www.biology.ucsd.edu/~msaier/supmat/Bba).

Putative Transporters Lacking Functional Data or Close Homologues in TCDB

One hundred and nine putative transporters were identified on the basis of their predicted transmembrane α-helical topologies, PSORTb localizations, and operon associations (Table S2). Like some of the proteins mentioned in the previous section and on our website, some of the proteins included in Table S2 had been annotated as permease-like constituents, and these were also investigated. The results of these studies are presented on our website.

Discussion and overview