Abstract

Background

To investigate the extent of methamphetamine and other drug use among American Indians (AI) in the Four Corners region, we developed collaborations with Southwestern tribal entities and treatment programs in and around New Mexico.

Methods

(1) We held nine focus groups, mostly with Southwest AI participants (N=81) from three diverse New Mexico communities to understand community members, treatment providers, and clients/relatives views on methamphetamine (2) We conducted a telephone survey of staff (N=100) from agencies across New Mexico to assess perceptions of methamphetamine use among people working with AI populations. (3) We collected and analyzed self-reported drug use data from 300 AI clients/relatives who completed the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) in the context of treatment at three diverse addiction treatment programs.

Results

Each focus group offered a unique perspective about the effect of drugs and alcohol on each respective community. Though data from the phone surveys and ASIs suggested concerning rates of methamphetamine use, with women more adversely affected by substance use in general, alcohol was identified as the biggest substance use problem for AI populations in the Southwest.

Conclusions

There appears to be agreement that methamphetamine use is a significant problem in these communities, but that alcohol is much more prevalent and problematic. There was less agreement about what should be done to prevent and treat methamphetamine use. Future research should attend to regional and tribal differences due to variability in drug use patterns, and should focus on identifying and improving dissemination of effective substance use interventions.

Keywords: American Indian, Tribal Based Participatory Research, Methamphetamine, Substance Use, Addiction Severity Index, Phone Survey, Qualitative, Focus Group, Protective Factors, Southwest

Introduction

Methamphetamine use has been endemic in the Western United States and Hawaii for two decades, and use appears to be increasing in the Midwest and East Coast. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) suggests that about 5% of the population 12 years of age and older report lifetime use of methamphetamine; use in the prior year is about 0.5% (NSDUH Appendix C). Methamphetamine prevalence is much higher in the Western US (1.2% in the past year) compared to use in the Midwest and South (0.5%) and the Northeast (0.1%) (Office of Applied Studies, 2007). Between 2002 and 2005, New Mexico ranked in the top 10 states for methamphetamine use, both for the entire population over 12 years of age and for the high risk group of young adults between 18 and 25, with past year use rates in excess of 1% and 3%, respectively (Office of Applied Studies, 2006).

Regarding race/ethnicity, methamphetamine use was originally thought to be concentrated among White males in the U.S. In 2005, Whites comprised the greatest percentage of clients admitted to substance abuse treatment primarily for methamphetamine (71%) with Hispanics next (18%) and other races at 8% and African American at 3% (Office of Applied Studies, 2005). However, when U.S. patterns of use are examined within racial/ethnic categories, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander reported the highest use rates in the past year at 2.2%, with American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) at 1.7%, Whites at .7%, and Hispanic or Latino at .5%. Asians and African Americans report the lowest rates (0.2% and 0.1% respectively, Office of Applied Studies, 2006). Taken together, these epidemiological findings suggest a discrepancy between the racial/ethnic groups reporting the highest use of methamphetamine and those receiving treatment for methamphetamine.

There is very little published literature regarding the use and effects of methamphetamine in most tribal communities and much of this information available is anecdotal (Young & Joe, 2009). In the published research examining rates of substance use among specific AI/AN regions (e.g., among American Indians in Los Angeles County) methamphetamine use appears to be high among American Indians/Alaskan Natives in these regions and has become a serious concern for many AI/AN communities (Spear, Crevecoeur, Rawson & Clark, 2007). More generally, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health Report notes elevated rates of substance use among AI/AN compared with persons from other racial/ethnic groups (Office of Applied Studies. 2007). Analysis of cross-sectional data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (N=14,332; 18–26-year-olds) showed that 12.8% of Native American youth had used methamphetamine in the past year (compared to 3.3% White, 0.6% African American, 1.9% Hispanic, and 1.8% Asian) (Iritani, Hallfors et al., 2007). An analysis of NSDUH data for 2002–2006 by state revealed large differences in methamphetamine use among AI/ANs compared to non-AI/ANs (Colliver. 2007). Overall past-year rates of methamphetamine use for the country were 1.4% for AI/AN, vs. 0.6% for all others. However, while some states showed much higher rates of methamphetamine use among AI/AN compared to other races (e.g., 4.7% vs. 0.9% for all others in Montana, p < .01), New Mexico and Arizona actually showed similar rates of Methamphetamine use among AI/AN than those found in non-Natives (0.4% vs. 1.1%, 1.1 vs. 1.3%, respectively, differences not statistically significant). Anecdotal reports from around the Southwest suggest that rates of methamphetamine use and associated problems of increased crime, family and child welfare, employment, psychiatric and religious and spiritual problems vary markedly from community to community (Abbott, 2008; Barlow et al., 2010). For example, high rates of use are reported by addiction treatment providers in Farmington, NM, and the White River Apache reservation in Arizona, while relatively low rates are reported in the Gallup, NM area. These data underscore the vast variability among tribes in substance use patterns.

Although there are epidemiological data regarding substance use among AI/AN populations, researchers have also established that rates of alcohol and illicit drug use among AI/AN vary by tribe, gender, and age group, making it difficult to get an accurate estimate of the actual extent of the problem of substance abuse within this population group (May & Gossage, 2001). Given this dearth of published research on the prevalence of methamphetamine use and related problems in specific AI/AN communities, in 2008 the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network (CTN) provided supplements to five of its research sites to begin a dialog with tribes in their areas and to collect preliminary data concerning the impact of methamphetamine and other drugs on these communities. These voices and perceptions provide information not found in the literature that can inform us about beliefs regarding causes of methamphetamine and other drug use as well as availability, extent of the problem, and recommendations for intervention. Community and tribal perceptions can then guide educational efforts where needed and intervention efforts toward more evidence based practice. The paucity of research regarding rates and effects of methamphetamine in specific AI populations, coupled with media reports highlighting extreme cases of methamphetamine use and negative consequences, led to a need to obtain a broader empirical view of the problem. In working with their community partners, each Node developed somewhat different methods and strategies. Here we describe the project conducted at the Southwest Node, based at the University of New Mexico Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions, in collaboration with community partners in the Four Corners region, particularly on and around the Navajo Nation. This study employed mixed methods to provide multiple perspectives on the prevalence of methamphetamine use and related issues in American Indian communities and agencies serving American Indians in the Four Corners region of the American Southwest. Specific aims of the study were as follows:

To conduct focus groups in collaboration with Southwestern American Indian communities--meeting with community leaders, substance abuse clients/relatives*1, and substance abuse treatment providers--to develop qualitative descriptions of perceptions about methamphetamine use, how much of a problem methamphetamine use is, and recommended interventions for methamphetamine abuse and dependence.

To conduct a structured telephone survey of addiction treatment agencies, schools and criminal justice facilities in American Indian communities throughout New Mexico and the Four Corners region, with content including estimates of methamphetamine use, correlates, and consequences in the communities served by the agencies.

To assess the prevalence of methamphetamine use, other substance use, and co-occurring problems in treatment-seeking American Indians by analyzing Addiction Severity Index interviews with American Indians seeking treatment for substance use at American Indian treatment programs in the Southwest.

General Methods

Participatory research is essential when working with minority groups including American Indians and Alaska Natives (Wallerstein & Duran, 2006). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) or Tribally-Based Participatory Research (TBPR) emphasizes the value of an alliance between investigators and communities in the design and completion of studies that address health promotion and health disparities (Thomas, Rosa, Forcehimes & Donovan, in press). Effective collaboration leads to studies that address research questions of high importance to the community, promotes community participation, enhances the interpretation of results, and facilitates the dissemination and adoption of study findings. We conducted this study using CBPR approach. Briefly, we sought partners from various AI communities (Gallup, Farmington, Zuni, Mescalero Apache, Albuquerque). We worked with community partners at the Na’Nizhoozhi Center, Inc. (NCI) in Gallup to plan the study, develop the instruments, help facilitate the focus groups, interpret these data, review scientific presentations, write this manuscript and disseminate our findings. Much of the study (Specific Aims 1 and 2) was designed to get input directly from community members and treatment providers. All procedures were approved by two IRBs: the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board (NNHRRB) and the UNM Human Research Review Committee. The NNHRRB reviewed and approved this manuscript and all other scientific presentations resulting from this project, reviewed quarterly and annual progress reports, and required an extensive dissemination plan that we have nearly completed. As an additional protection to confidentiality, a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from NIDA.

Navajo teachings include four tenets that helped guide the implementation of this study and are inconsistent with drug use. The first is Ádééhániih-Thoughts and concerns of self. Navajo culture teaches that Ádééhániih is an important development to self identity and appropriate self observation. The second teaching is Ádáhodílzin-Respect and Reverence. Navajo culture educates that Ádáhodílzin is necessary when on the path of attaining knowledge. Ádáhodílzin practice requires remaining ethical and proper within appropriate family values, which applies to the ethical conduct of research. The third is Ádaa Hááh Hasin- Limits, referring to safe and unsafe practices of knowledge, boundaries and competence. In this practice of Ádaa Hááh Hasin, attained knowledge must be respected and handled with care and competence. The findings from this study were handled with care by working with our community partners under the guidance of the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board. Finally, the fourth is K’éhodiindzin-Kinship practice. Navajo culture is founded in the active kinship practice known as K’éhodiindzin. Navajo people who practice K’éhodiindzin understand the importance of health, thus our focus on strengths and next steps for the betterment of American Indian people. A commitment to these Navajo teachings is meant to prevent destructive behaviors such as substance abuse and to help those who are recovering from substance abuse problems.

Study 1: Focus Groups

Method

Two facilitators, one of whom is an Alaska Native (K.V.), led a total of nine focus groups in three communities (Albuquerque, Farmington and Gallup). In each city, three separate focus groups were conducted with community members, addiction treatment professionals, and addiction treatment clients/relatives. Each session included five to 10 participants. In order to protect confidentiality, participants provided only verbal informed consent and we did not collect demographic information. A Navajo speaker was present for the groups held in Gallup and Farmington, and we sought input from tribal partners when clarification was needed about Navajo terms used during the focus groups. In collaboration with our American Indian research partners, we developed an interview guide comprising 13 questions that facilitators read aloud to structure the process. Questions probed the role of methamphetamine and other substance use (including alcohol) in the tribal communities, possible causes of methamphetamine use, the availability and helpfulness of treatment and other forms of help, and ideas about what is needed to address the problem more effectively.

Focus groups were transcribed and double checked by having a second research assistant review the audio recording, read through the transcription, and flag any discrepancies. These discrepancies were then individually discussed and reconciled. Following transcription, separate documents were created to capture various themes. Analyses of the transcripts were completed by the facilitators, transcribing research assistants, and tribal partners. These individuals independently reviewed the transcripts and suggested thematic categories. These independently-generated categories were then compared and combined via a consensus process. We categorized obvious themes related to methamphetamine and other drug use; e.g., prevalence and epidemiology, adverse individual consequences, adverse community consequences, individual and environmental reasons for methamphetamine use, available resources to combat methamphetamine use, desired resources, and proposed methods to combat methamphetamine use. Because there was substantial overlap in answers between many of the questions, qualitative analyses were completed for six of the 13 questions.

Results

Between June, 2009 and October, 2009 nine focus groups with a total of 81 participants were conducted in three cities in New Mexico. The major themes by site (Gallup, Farmington and Albuquerque), by type of group (treatment provider, client/relative, community member), and by question are discussed using portions of the participants’ answers for illustrative purposes.

Overall and site-specific themes

Across the three sites, there was agreement that alcohol is the most significant problem affecting communities and that prescription drug use appears to be on the rise and is a source of increasing concern. Most Gallup and Albuquerque respondents felt that methamphetamine was not a huge issue for American Indians in their communities. Farmington participants, on the other hand, reported experiencing much more of a problem with methamphetamine than other areas, and focus group participants believed these higher rates were due to local occupational demands such as working in the oil fields.

The focus group participants in Gallup demonstrated the strongest sense of pride in the community, but Gallup groups also indicated a lack of available resources compared to larger cities like Albuquerque. In Gallup, there was a strong emphasis on the incorporation of traditional practices of living and healing as a key to prevention of substance use which was a prevention effort voiced much less in the other two cities. In Albuquerque, focus group participants were often off-task when discussing specific American Indian problems, possibly due to less AI representation in these groups (as noted by the focus group facilitators). Another consistency across the Albuquerque groups was that they were aware (in contrast to Gallup) of the many resources available in the larger city, but believed that communication “wasn’t like a nice small town” and that it was difficult for people to know about and access addiction treatment in such a large city. Participants felt that big cities made people feel more disconnected in general and that people (especially AIs) have difficulty navigating where to go for addiction treatment. In Farmington, methamphetamine use had directly impacted the majority of the focus group participants, and many shared specific examples of the effects of methamphetamine and other drug use in their families. Another interesting finding across the groups was the level of misinformation evident in the participant’s responses. For example, several participants reported that methamphetamine could be made from simple household products, e.g., “You can just get RAID and spray it on a metal screen and stick a battery cable to it. Bam! There you go. You’ve got crystal meth.” Apart from these site differences, there was significant overlap in responses to specific questions across the sites. For this reason, we discuss the responses to specific focus group questions below by highlighting differences and similarities across treatment group, and mention site differences only when noteworthy.

Treatment providers

Most addiction treatment providers seemed to be in agreement that in order to be effective, treatment should have an element of confrontation and should make clients/relatives “overcome denial” and “educate them about what a mess they’ve made of their lives.” The treatment providers seemed unsure of the specific signs of methamphetamine use, particularly when asked to differentiate between a methamphetamine user and a user of a different stimulant. When asked about effective methods to decrease substance use, providers believed that community involvement and control of ingredients were crucial. Surprisingly, despite many of these treatment providers working in tribal community settings, most advocated Western-based treatment practices, and it was only after prompting from the facilitators of “what about traditional healing practices?” that providers responded with comments such as, “oh…I guess that might be good.”

Clients/Relatives

The main theme in the client/relative group was that intrinsic motivation was the key to recovery from drugs and alcohol. As one client stated, ““You have to change yourself…if you want it…inside out.” Most clients/relatives scoffed at the use of the scare tactics such as the “meth mouth” billboards and commercials, saying those techniques were a “waste of money”. The clients/relatives in each group offered very detailed descriptions of the signs of a methamphetamine user. One client/relative said, “you’ll see the trademark black stains on fingers and clothes [from the meth pipe]”. Many of the clients/relatives felt that effective treatments were those that focused on tradition and spirituality. There were also strong opinions in the groups that clients/relatives preferred working with providers who had a shared experience of recovery.

Community members

Community members’ ideas seemed to be largely based on media influence. In many of their responses to the questions, there was clear integration of billboards, television commercials, TV programs and radio advertisements. Community members frequently began their responses with the source of their information, e.g., “It was in the newspaper not too long ago that…” and many of their beliefs about what methamphetamine is and seemed obviously tied to the media attention given to this substance. The community members were in strong support of advertisements and billboards that had shock value and felt that stiffer penalties for drug users were needed. Punishment over rehabilitation was promoted, with participants suggesting stiffer penalties such as “zero tolerance…like DWI”.

Themes from specific questions

“How much of a problem?” Participants across the communities felt that methamphetamine was more of a problem when it was first introduced to the communities. As one participant stated, “the newness has worn off.” Methamphetamine seemed to be the drug of choice for jobs requiring long shifts and for people unable to afford more expensive drugs. Perceived rates of methamphetamine use were low in Gallup and Albuquerque, but Farmington participants felt that their city was “affected more than other regions by far”.

“Where is it coming from?” The beliefs regarding the source of methamphetamine production differed significantly by type of group The community members believed that methamphetamine was trafficked from Mexico, making comments such as “I don’t believe in the last five years we’ve had a lab here…” and “there’s too much police presence in these areas.” And “…they can’t get a hold of the stuff to make it from here…because this is a small area…” The treatment providers were less aware of or willing to accept local production. According to clients/relatives, however, the source of methamphetamine was much more proximal, and most participants felt that it was both made and distributed to the communities by locals. One participant reported that “On the [reservation], there was this grandma and she was probably…in her seventies. She was making it and selling it. She had her granddaughters transporting it to people here and there.”

“How would you know if someone was on methamphetamine compared to another stimulant?” As mentioned above, the stark contrast between responses from the treatment providers and clients/relatives was particularly intriguing for this question. Providers briefly discussed the topic, although many responses were simply “I don’t know.” Clients/relatives were animated in their responses to this question and had a great deal of information to share, often interrupting each other to give another detail, “yeah, yeah, and there’s also the hygiene…there’s a particular smell that you just know!” The community members responded only with what seemed to be rote recall of information portrayed on TV and in public service announcements, commenting on poor dental health, lots of cleaning, and trading sex to get the drugs.

“What should be done for prevention?” Re-integration into one’s culture and traditions was a theme heard across groups. As one person stated, “…involving youth in the traditional practices..[and] drumming…dancing…learning the respect of elders…and seeing it as part of their life.” Educational and confrontational approaches were strongly promoted by treatment providers, with comments stated such as “if someone hasn’t hit bottom, push them.” Clients/relatives stressed the value of finding something that, to them, was more important than the drug use, e.g., “…but then I just look at my daughter and just…that look in her face, I never want to see that expression on her face again.” Clients/relatives didn’t believe in punishment, saying, “…”look at jail. They still sneak it in. Nothing really to do. Unless you want it to be different.” Another client said, “I don’t care how many medicine men you go to. I don’t care how many ceremonies you go to. I don’t care how much Native American church you partake of that medicine…Nothing’s going to help you until you’re ready.” The community members advocated education, including “before and after pictures” of the effects of methamphetamine use and using programs such as scared straight and “smarter police” able to enforce the laws and punish those who choose to break them.

“What are the most effective treatment methods?” The responses to this question surprised us because of the absence of AI traditional practices included in the responses in the Gallup and Albuquerque groups. Though some responded after some prompting, others didn’t seem to endorse this approach at all, instead advocating a Western medicine-based approach. The exception to this was in the Farmington community and client/relative groups, where there were more positive endorsements of religious/spiritually-based traditional treatment. Many participants in these two groups gave specific examples of how these approaches helped their family members and themselves. Surprisingly, treatment providers did not seem to share this opinion. The facilitator asked the treatment provider group, “Are there other sorts of spiritual or religious traditions helping methamphetamine and other drug use problems?” and one provider responded, “This is one where we have no ideas.”

“What are the community strengths?” The strengths identified by the focus group participants varied by site and group, but all answers seemed to fall in fairly distinct categories including resources, community support and involvement, and availability of activities. Strengths that were noted included having strong ties to one’s family or partner and a continued incorporation of traditional practices and spirituality or religious beliefs. As one person stated, “it’s the nature of our culture to be accepting and loving, and to stay as a family and work together, then the fact that we teach family members how [to] reinforce that with loved ones that are trying to recover is a strength.” Across all nine groups, the discussion of strengths transitioned into a discussion of community needs. Many participants indicated that resources needed in their community included more employment opportunities, better access to treatment and rehabilitation, more communities interested in engaging in a neighborhood watch program, more effective law enforcement, and a large increase in the number of available activities, including youth programs, sports and games, and the increased availability of chapter houses in the community. The groups all seemed in support of activities that they believed would provide an effective alternative to drug and alcohol use.

Study 2: Telephone Surveys

Method

A list was constructed of over 200 criminal justice settings (police departments and jails), schools, addiction treatment programs, and medical facilities in 26 counties in the Four Corners region. Each agency contacted for a telephone survey was first notified of the study intent and a request was made for permission to conduct the survey at that agency. This permission was obtained from the school board overseeing each high school; the hospital Board of Directors and/or Administration; the Sheriff, Chief of Police, or director of the Department of Public Safety overseeing each law enforcement agency; the director of each treatment agency; or the director of the Navajo Nation Department of Behavioral Health and the Navajo Area Indian Health Board. Once permission was obtained, interviewers asked each agency contact to recommend the best staff member to complete the survey. The interviewer suggested that the recommended personnel member be actively involved in the treatment of the American Indian clientele at their agency, or that they be in a supervisory position, with a good sense of substance use trends among their American Indian clients.

Using a structured interview developed for this study, agency personnel (N=100) of 100 different agencies were asked to answer survey questions over the phone regarding their perceptions of methamphetamine use, correlates, and consequences. The telephone surveys were conducted by five different research staff involved in the project. Efforts were made to contact all agencies we had permission to contact. Research assistants attempted to reach each site contact on the list several times until the goal of 100 surveys was achieved. In order to maintain confidentiality, written informed consent was not obtained, and no names or other identifying information were associated with surveys. Prior to completing the survey, the interviewer confirmed that the agency served a significant number of AIs, and that the individual completing the survey had enough experience to have an informed opinion concerning substance use in the AI population they served. The survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete. Participants were told that they could terminate participation at any time. Questions were read aloud and included a mix of quantitative and qualitative items, using both Likert-type questions regarding the severity of methamphetamine use and open-ended questions such as “describe some of the problems you have seen related to methamphetamine use in your community,” as a way to broaden response sets.

Survey data were transferred into an SPSS R database for analysis. Descriptive statistics and rankings of methamphetamine relative to other substances were computed. Severity of methamphetamine problems among the regions surveyed was also contrasted. Non-parametric methods were used due to the distributional characteristics of the scales.

Results

Telephone survey participants (N=100, 50% female) included 54% White, 22% Hispanic 10% American Indian, and 14% other or missing. We divided the counties into six similarly sized groups: (Group 1, n = 22) San Juan, (Utah), Coconino, Apache, Navajo, (Group 2, n = 15) Montezuma, La Plata, Archuleta, (Group 3, n = 14) San Juan (NM), Rio Arriba, Los Alamos, Santa Fe, Sandoval, (Group 4, n = 12) Taos, Colfax, Union, Guadalupe, (Group 5, n = 13) Socorro, Lincoln, Otero, Chavex, Lea and (Group 6, n = 24) McKinley, Cibola, Valencia, & Bernalillo. Regarding agency types, 13 surveys were completed at medical agencies, 23 at police departments or jails, 28 at schools and 36 at treatment agencies. Although all of the agencies surveyed served significant numbers of American Indians, only 10% of the staff members surveyed were self-identified as American Indian.

Ranking of substances by community problem severity

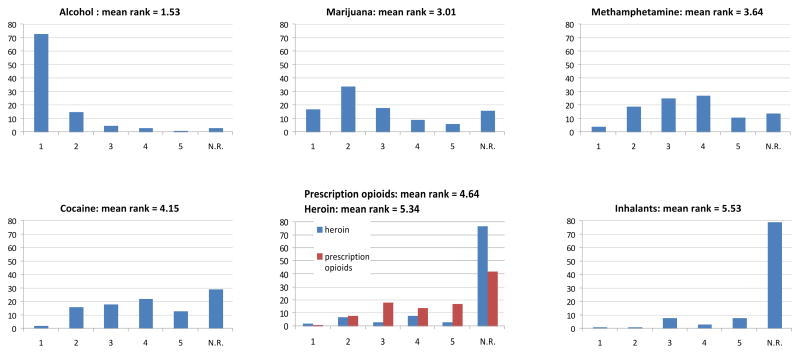

Participants were asked to rank the five most problematic substances for American Indians in their communities. Most respondents (73%) identified alcohol as the number one problem substance, followed by marijuana (17%), methamphetamine (4%), cocaine (2%), heroin (2%), prescription opioids, (1%), and inhalants (1%). The highest ranked substance other than alcohol and methamphetamine was most commonly marijuana (59%), followed by cocaine (15%), prescription opioids (14%), heroin (7%), and inhalants (5%). Rankings are shown in Figure 1. These ranks were significantly different from each other (Friedman’s two-way analysis of variance by ranks, (χ2(6)= 286.289, p < .0005). Alcohol ranked higher than each other substance in pairwise comparisons (Wilcoxon signed ranks test, all p < .0005). Marijuana ranked significantly higher than methamphetamine (Z = −.2497, p = .013), and methamphetamine ranked higher than cocaine (Z = −2.062. p = .039), prescription opioids (Z = −4.484, p < .0005), heroin (Z = −6.325, p < .0005), and inhalants (Z = −6.894, p < .0005). Among American Indian respondents, all rated alcohol as the biggest problem in their community.

Figure 1.

Problem severity rankings by substance per telephone survey

Regional variability

Six additional items were included in the survey to quantify problems in the community related to methamphetamine: problem severity, increase during the past five years, increase during the past year, local production, effect on violent crime, and availability. We compared ratings for these questions among the six county groups in order to detect any differences by region in the perception of problems related to methamphetamine (Kruskal-Wallis test). Two of the six items showed significant regional variability. Perceptions of local methamphetamine production and methamphetamine-related violent crime varied significantly by region (p = .012, p = .048, respectively). Although these differences would not survive protection for multiple comparisons, some of the observed effect sizes were large, e.g., d = 1.39 between region 2 (high) and region 4 (low) with respect to perceived local methamphetamine production, d = .97 between region 1 (high) and region 3 (low) with respect to perceived methamphetamine-related violent crime.

Study 3: ASI Data Collection

Method

The Addiction Severity Index (McLellan, Alterman, et. al., 1992) interview data were collected from 300 clients/relatives across three sites: Na’Nizhoozhi Center, Inc. (NCI), in Gallup, NM, Totah Behavioral Health, in Farmington, NM, and San Juan County Alternative Sentencing Division (SJCASD), in Farmington, NM. All sites serve AI clientele, although the two tribal-based programs serve a much larger proportion (approximately 99% at NCI, 96% at Totah, 23% at SJCASD). Additional approvals to collect ASI data were obtained from each agency including Presbyterian Medical Services, which is the parent organization of Totah. Each of these programs used slightly different forms of the ASI, all available only in paper format. All of these versions are quite similar and contain identical questions concerning quantity and frequency of substance use. Therefore a common database was constructed that was compatible with all three ASI versions, and data from the ASIs were entered by hand into the electronic database. These ASIs had been completed for clinical purposes prior to this study, during the intake to treatment for each site’s clients. In an effort to collect ASI data only for AI patients, the research assistant responsible for data collection set aside any file with an ethnicity other than AI. The research assistant worked through the files alphabetically until a total of 100 ASIs were collected from each agency. At each site, the research assistant was able to complete ASI data collection for 95–100% of all active or recently active, clients/relatives to reach the total of 100 ASIs for each site. Data collection for the study involved only the entry of anonymized archival information from each site into the common database. The ASI is a widely-used standardized instrument that yields composite scores in seven domains including medical, employment, alcohol, drug, legal, psychiatric, and family (scores range from zero to one, with higher scores indicating greater problem severity). Because there were some omissions in items used to compute certain composite measures, computation of the affected composite measures (medical, alcohol, drug, and psychiatric at Totah; psychiatric at NCI) was adjusted so that these measures would adhere to the standard scaling (McGahan, Griffith, Parente, & McLellan, 2004). ASI data were transferred to an SPSS R database for analysis. Amphetamine use as reported in the ASI (which includes both methamphetamine and other amphetamines) was used as a proxy for methamphetamine use. Standard composite scores were computed. Multivariate analysis of variance was used to test for differences in ASI composite scores across gender, age group, and site, using rates of use of methamphetamine and alcohol over the previous 30 days as covariates.

Results

Only files identified as AI were included; no other data are available on the racioethnic backgrounds of these participants. A majority of the 300 participants were male (58.2%). The mean age was 34.2, SD 10.95 years. Because age followed a bimodal distribution with peaks at 24 and 44 years, age was analyzed by group (“younger” = 18–32, “older” = 33–68). The mean years of education was 11.6 (SD 1.4). Most participants (93.1%) reported at least 10 years of education, while 2/3 (66.7%) reported 12 or more years of education. Descriptive statistics revealed that 21.4% of participants reported some lifetime amphetamine use, with 3.7% reporting amphetamine use in the previous 30 days (see Table 1). Three participants reported amphetamine as their primary problem substance, while alcohol was reported as the major problem substance by 67.0% of respondents (see Table 2).

Table 1.

Number and percentage of participants reporting any use of a substance in the previous 30 days and over lifetime per ASI

| Substance | Previous 30 | Lifetime | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Alcohol | 115 | 38.3 | 276 | 92.3 |

| Alcohol to intoxication | 99 | 33.0 | 255 | 85 |

| Heroin | 3 | 1.0 | 9 | 3.0 |

| Methadone | 2 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.7 |

| Opiates | 5 | 1.7 | 4 | 1.3 |

| Barbiturates | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.7 |

| Sedatives | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 1.0 |

| Cocaine | 9 | 3.0 | 41 | 13.7 |

| Amphetamine | 11 | 3.7 | 64 | 21.4 |

| Marijuana | 38 | 12.7 | 159 | 53.2 |

| Hallucinogen | 2 | 0.7 | 14 | 4.7 |

| Inhalant | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 2.3 |

| More than one drug | 22 | 7.3 | 92 | 30.8 |

Table 2.

Self-reported major problem substance reported by number and percentage of participants per ASI

| Substance | f | % |

|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 38 | 20.2 |

| Alcohol to intoxication | 126 | 67.0 |

| Amphetamine | 3 | 1.6 |

| Cannabis | 4 | 2.1 |

| Alcohol +Drugs | 11 | 5.9 |

| Drugs -Alcohol | 5 | 2.7 |

| Total | 188 | 100 |

Note: Major problem substance is the substance identified during the interview as the major problem (item D14). Total frequency does not equal 300 because this item is not collected in the ASI Lite that was used with 112 participants at the San Juan County Alternative Sentencing Division site.

Average ASI composite scores for each site and in the aggregate are reported in Table 4; higher scores indicate greater severity. Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) results revealed no significant interactions of Gender×Site (F(14, 558) = .816, p = .652), Gender×Age (F(7, 278) = .859, p = .539), Age×Site (F(14, 558)=1.25, p = .234), or Gender×Age×Site (F(14, 558) = .914, p = .543), but did demonstrate significant main effects for Gender (F(7, 278) = 2.352, p = .024), Age (F(7, 278) = 5.213, p < .001), and Site (F(14, 558) = 14.0, p < .001), indicating significant group differences on the linear composite of ASI scores. Amphetamine and alcohol use rates were both significant covariates. Univariate follow-up procedures used a Holm-Bonferroni correction (Holm, 1979) to reduce the probability of a Type I error, with an α of .05 for each follow-up. Each p value that survived this correction is indicated with an asterisk (*). These indicated that the main effect of Gender was driven primarily by the Drug (F(1, 284) = 10.919, p = .001*), Psychiatric (F(1, 284) = 5.548, p =.019), and Family (F(1, 284) = 1.889, p = .17) composites, with greater severity for females in all three measures. The main effect of Age was driven by the Medical (F(1, 284) = 12.043 p = .001*), Drug (F(1, 284) =6.040, p = .015), Legal (F(1, 284) = 4.538, p = .034), and Psychiatric (F(1, 284) = 10.857, p = .001*) composites, with higher Medical and Psychiatric severity in the older group and a non-significant trend toward higher Drug and Legal severity in the younger group. The main effect of Site was found in Alcohol (F(1, 284) = 6.567, p = .002*) Drug (F(1, 284) = 9.069, p < .001*), Legal (F(1, 284) = 51.672, p < .001*), Psychiatric (F(1, 284) = 9.163, p < .001*) and Family (F(1, 284) = 11.063, p < .001*) composites, such that NCI and San Juan County Alternative Sentencing Division were higher on the Alcohol, Drug, Legal, and Family composites than was Totah, and NCI was higher than Totah and San Juan County Alternative Sentencing Division on the Psychiatric composite indicating greater comorbidity. While the Employment composite score was quite high across sites (m = .8556, sd = .214), follow-up tests did not indicate differences on this measure for Gender, Age, or Site, nor an effect for either covariate.

An exploratory analysis was conducted to compare ASI composite scores from participants reporting any lifetime use of amphetamine (n=64) to those from participants reporting use of any other substance (n=234). MANOVA revealed a significant multivariate main effect of amphetamine use (F(7, 290) = 6.205, p < .001). Univariate follow-up tests suggested that this effect was driven by the Drug (F(1, 296) = 27.481, p < .001*), Legal (F(1, 296) = 14.160, p < .001*), and Family (F(1, 296) = 13.774, p < .001*) composite scores, with greater severity for amphetamine users in all three areas. Site, Age, and Gender were not included in this analysis, as this would have involved extremely small cell sizes (e.g., three male meth users over the age of 33 at one site, one female meth user under 32 years old at another), introducing substantial uncertainty into any results.

Discussion

This mixed method study of methamphetamine use among Southwest AI communities elucidated the extent and perceptions of the methamphetamine problem in the Four Corners region and collected recommendations from clients/relatives, patients, and community members regarding what needs to be done to effectively prevent and treat methamphetamine and other drug use. Phone survey, ASI and focus group data offered qualitative and quantitative methods to examine the extent of the methamphetamine problem in the Four Corners region. The focus group results gave detailed information on what community members, treatment providers and clients/relatives recommended as ways to address substance use problems. American Indian traditions and culture were highlighted as strengths of these communities especially in terms of prevention. We discuss contributions from each method of investigation and conclude with an overall summary and future directions.

Extent of the Problem

It was clear from the phone surveys, ASI data and focus groups that methamphetamine is a significant problem among Southwest native communities and also that alcohol is still the most prevalent and significant substance use problem.

Telephone Surveys

The telephone surveys present convincing evidence that alcohol is perceived as the most problematic substance by far for American Indians in the Four Corners region of the Southwest. Marijuana ranked second, followed by methamphetamine, cocaine, opioids, and inhalants. Interestingly, most national surveys of the general population similarly report alcohol and marijuana use as the substances highest in prevalence. However, in contrast to our findings, a national survey reported methamphetamine use as much lower in prevalence than other drugs such as prescription opiates, cocaine, hallucinogens and tranquilizers (SAMHSA, 2003–2005 NSDUH). Furthermore, prevalence rates of drug use in a Southwest tribe indicated that stimulants rank 5th for men and 6th for women among drug classes other than alcohol (Mitchell, Beals, Novins, et al., 2003). These findings suggest that methamphetamine use is a significant concern. The findings also suggest the possibility of regional differences, with more severe problems in some areas of the Four Corners region. Similar to other drug use patterns, there is bound to be great variability in prevalence of methamphetamine use among tribes, which this study was not designed to address.

ASIs

Clients/relatives who complete the ASI are expected to have more severe drug and alcohol problems than the general population because they are presenting for substance abuse treatment and some are in an alternative sentencing program for methamphetamine-related offenses. The analyses of ASI data present a similar pattern to the phone survey data with regard to alcohol and marijuana being the most prevalent. Despite high self-reported rates of lifetime and past month amphetamine use (21.4% and 3.7%, respectively compared to US norms of 5% lifetime and .5% past year (Office of Applied Studies, 2007), most participants in the present study reported alcohol, not amphetamine, as the primary problem substance in their lives. While this offers a cross-sectional snapshot of AI amphetamine and other drug use, this does not give a clear picture of substance use over time and in comparison to other ethnic groups. Fortunately, New Mexico’s managed care organization for behavioral health mandates the ASI for all clients presenting for addiction treatment. This rich database will allow future comparisons of our AI data by ethnic groups and regions. Analyses revealed significant effects of age, gender and site on ASI composite scores, highlighting the unique challenges faced at AI treatment sites within the same region. Interestingly, older age was associated with higher medical and psychiatric severity whereas younger age was associated with a trend toward higher drug and legal severity scores. The observed gender differences suggest a special burden for females in these treatment settings, who, across all three treatment sites, reported more severe family, psychiatric, and drug-related problems. Higher severity on the family composite may be related to increased awareness of family problems and more distress related to them or due to increased family responsibilities for women, such that drug use impacts the family more severely for women than for men. This distress may exacerbate the reported drug and psychiatric problems. This hypothesis should be explored further in future controlled studies. In addition, participants at all sites reported significant employment problems, an ongoing challenge that has been previously reported by our research group (Foley et al., 2010). Finally, those who reported any lifetime amphetamine use (~20%) appeared to experience increased severity in drug, legal, and family domains than those who reported no use of amphetamines probably contributing to tribal and community concerns about methamphetamine use. In general, our results suggest that methamphetamine treatment at AI sites must be customized to meet the unique needs of these communities, and that concomitant treatment for alcohol use should be considered whenever possible.

Focus Groups

Findings from the focus groups suggested several points of consensus among the focus group participants. One was that alcohol was the most prevalent and significant substance use problem affecting their communities and that prescription drug use was an emerging concern. Similarly, most participants reported methamphetamine use to be more problematic about five years prior to the date of these focus groups. In 2005 the Navajo Nation government passed legislation to outlaw methamphetamine use, possession, distribution and manufacture. The tribe also established an award-winning methamphetamine task force to educate community members about methamphetamine (Lynch, 2007). Such proactive leadership along with effective, unified federal and local law enforcement to close down local production of methamphetamine, may have contributed to the perception that methamphetamine use has declined over the past 5 years. Finally, many participants touched on the theme of using methamphetamine for jobs requiring long hours such as for the oil companies, which is similar to previous findings with long-distance truck drivers (McCartt, Rohrbaugh, Hammer & Fuller, 2000; Williamson, 2007).

Addressing the Problem

The answers to what should be done to prevent or treat people with methamphetamine problems were revealed by the focus group aim of this study. The answers to what should be done varied significantly by type of focus group, and each group of participants held opinions that deviated significantly from the best available scientific evidence. Community members were dedicated to prevention efforts, even those that included scare tactics, which are not effective (e.g., DARE program, Ennett, Tobler, Ringwalt, & Flewelling, 1994). Community members also emphasized zero tolerance laws and increased punishment, despite the inefficacy of this controversial strategy in the “war on drugs” (Benson, Sebastian, & Rasmussen, 2001). Clients/relatives felt strongly that no intervention would be helpful until the individual was ready to change or wanted to change. Although client motivation is crucial to initiating and maintaining abstinence or reduction in substance use, there is ample evidence that counselors and other treatment providers play an important role in helping clients/relatives increase motivation and make decisions to change (i.e., Miller & Rollnick, 2002; Moyers, Martin, Houck, Christopher, & Tonigan, 2009). There appears to be a need for more education regarding effective treatment approaches for substance use disorders for the treatment providers who felt that confrontational techniques were the most appropriate way to treat those who suffer from a methamphetamine addiction. Unfortunately, there is a common misperception (certainly not limited to AI treatment settings) that confrontation is a necessary component to helping clients overcoming denial and beginning recovery. In fact, clinical trials have demonstrated that confrontational therapies generally lead to poor outcomes (Miller, & Wilbourne, 2002; Miller, Wilbourne & Hettema, 2003). To the contrary, it is actually counselor empathy, or ability to understand the client’s perspective, that is related to better alcohol treatment outcomes (Miller & Baca, 1983; Miller, Taylor & West, 1980; Valle, 1981).

Community and cultural strengths

Focusing on community strengths generated energy and pride after talking about methamphetamine and other substance use during the focus groups. A great strength among minority groups in general and AI in particular is the value and support of families and communities. Family members help each other out and stay together contributing to prevention of and interventions for those with substance use problems. One of the most frightening aspects of methamphetamine appears to be its potential to undermine traditional family structures and values, as exemplified in the infamous Gallup, NM case of “grandma meth” in which three generations in one family became involved in and convicted of the manufacturing and distribution of methamphetamines. Due to the shock value of this low base rate phenomenon, media stories such as this one tend to perpetuate negative stereotypes about AI and may distort the true extent of the problem.

In terms of the benefits of culture and AI traditions in dealing with substance abuse problems, consensus arose for prevention efforts with mixed opinions regarding treatment. Across the focus groups, a clear theme of integrating one’s culture and traditions in order to prevent substance use problems such as methamphetamine emerged. However, when asked about treatment recommendations, the three types of focus groups differed. Clients/relatives advocated for the use of treatments focused on tradition and spirituality; providers seemed to endorse a Western medicine-based approach; community members tended to push stricter drug laws and scared straight tactics except for the Farmington group who promoted culture and religious/spiritual based treatment. It is not clear why the treatment providers were less sure about using AI traditional healing for substance use problems, especially when two of the three agencies offer such services on site. Training programs for counselors often do not emphasize spirituality and religion (Verhagen & Cox, 2010). It is also possible that, these treatment providers may hold different spiritual or religious beliefs, or not consider spirituality/religion as an important part of recovery (Goldfarb, Galanter, McDowell, Lifshutz, & Dermatis, 1996). Finally, historically, AI, along with other indigenous people, were persecuted for practicing traditional spirituality. Speaking about AI traditions may still feel uncomfortable and certain spiritual traditions are sacred and not meant to be shared with outsiders (Hodge & Limb, 2010).

Due to the enormity of burden and negative consequences experienced by the communities, families and individuals abusing or dependent upon methamphetamine, efforts to find effective prevention and treatment interventions are crucial. Both contingency management and cognitive behavioral therapy were effective in reducing stimulant use in stimulant dependent adults (Rawson, McCann, Flammino, Shoptaw, Miotto, Rieber, & Ling, 2006), however no studies exist to report on effectiveness with AI/AN populations. Treatment providers could use more training in academic and continuing education programs regarding the effects of methamphetamine and the effectiveness of empathy over confrontational approaches. Given client/relatives preference for traditional healing, treatment providers might benefit from increased knowledge of the use of traditional healing practices in the treatment program. Even if methamphetamine use is on the decline, community members, treatment providers, policy makers and funding agencies should remain vigilant and work to improve prevention and treatment efforts for AI and all races to help reduce the suffering associated with methamphetamine abuse and dependence.

Limitations

Results of this study must be interpreted with caution due to limitations including convenience sampling, limited sample size, use of a survey instrument that has not been validated, and reliance on participant perceptions rather than objective measures of the problems surveyed. Due to the retrospective nature of the ASI data collection there were variations in the ASI version used across sites; follow-up studies should standardize this measure across participating sites. In addition, this study set out to examine perceptions and prevalence of methamphetamine among one racial group, AI, in the one region, the Southwest. Therefore, these findings are not meant to be generalizable to other tribes or to the general AI population in the US. Rather, given intertribal variation, future studies should examine specific tribes and regions to gain the actual severity of problems in that region as well as examine the effectiveness of specific treatments in AI treatment settings. This study did not include an examination of perceptions and rates of use among other racial/ethnic groups. Another limitation is that the ASI queries amphetamine use as the broader drug class, rather than asking specifically about methamphetamine use. Methamphetamine is a form of amphetamine that is structurally and functionally similar; yet methamphetamine is a more potent stimulant with a longer duration of action. While it is likely that most methamphetamine users would know that methamphetamine use would fall under the amphetamine category, it is possible this could have been confusing to some clients/relatives completing the ASI. Since there was no way to tease out methamphetamine use from other amphetamine use, it is possible that these ASI data overestimated methamphetamine use. Unfortunately, even though the telephone surveys focused on methamphetamine use among AIs, AIs only comprised 10% of the telephone survey respondents. Future studies would benefit by increasing the percentage of AIs represented in such a survey.

Overall Summary

The mixed methods approach of using focus groups, telephone surveys and ASIs from the Four Corners region of the Southwest suggests that prevalence and problems related to methamphetamine are on the decline from their worst point about five years ago. The data from telephone surveys and ASIs indicated that alcohol ranked as the most prevalent and problematic substance, with marijuana next followed by methamphetamine. Local variability in degree of methamphetamine use underscores the importance of identifying the specific localities or tribes that are most severely affected by methamphetamine, and directing prevention and intervention efforts to where they are most needed. Although this study identified cultural strengths that might be incorporated into future treatment and prevention interventions, it also identified some misperceptions about addiction, prevention, and treatment that are not unique to AI, but which provide possible targets for educational interventions. Much more work is needed to implement and test culturally appropriate prevention and treatment interventions for methamphetamine and other drug use (including alcohol) in Indian Country. Fortunately, as part of the process required for effective CBPR, the University has made strong connections with treatment programs in the Four Corners region, and, on a larger scale, all sites participating in this CTN protocol have made connections with tribes across the US. These collaborations and strong working relationships created a platform that will allow for future CTN research examining the effectiveness of specific treatments for AI/ANs.

Table 3.

ASI composite scores by site

| Composite | NCI* Mean (SD) |

Totah Mean (SD) |

San Juan Mean (SD) |

Aggregate Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | 0.188 (.274) | 0.124 (.292) | 0.122 (.261) | 0.144 (0.276) |

| Employment | 0.846 (.202) | 0.881 (.201) | 0.846 (.232) | 0.857 (0.213) |

| Alcohol | 0.262 (.198) | 0.168 (.238) | 0.217 (.195) | 0.216 (0.213) |

| Drug | 0.043 (.087) | 0.008 (.046) | 0.045 (.086) | 0.033 (0.078) |

| Legal | 0.200 (.155) | 0.050 (.087) | 0.259 (.144) | 0.176 (0.159) |

| Psych | 0.250 (.259) | 0.153 (.197) | 0.119 (.177) | 0.172 (0.219) |

| Family | 0.190 (.187) | 0.084 (.109) | 0.153 (.175) | 0.144 (0.167) |

NOTE: NCI: Na’Nizhoozhi Center, Inc.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIDA’s Clinical Trials Network Grant U10DA15833. We are grateful for the support of the Navajo Nation Human Research Review Board.

Footnotes

In many Navajo addiction treatment programs, clients are referred to as “relatives” to acknowledge the unity between the person and the counselor, as well as in keeping with the Dine’ K’e (the clanship system) that all Navajos are related. Throughout this paper, the term “client/relative” is used to describe participants in this study.

References

- Abbott PJ. Comorbid alcohol/other drug abuse and psychiatric disorders in adult American Indian and Alaska Natives: A critique. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2008;26(3):275–293. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow A, Mullany BC, Neault N, Davis Y, Billy T, Hastings R, Coho-Mescal V, et al. Examining correlates of methamphetamine and other drug use in pregnant American Indian adolescents. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center. 2010;17(1):1–24. doi: 10.5820/aian.1701.2010.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson BL, Leburn IS, Rasmussen DW. The impact of drug enforcement on crime: An investigation of the opportunity cost of police resources. Journal of Drug Issues. 2001;31:989–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Colliver JD. Methamphetamine Abuse in American Indian and Alaska Native Populations. Sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bethesda, MD: 2007. Methamphetamine Use among American Indians/Alaska Natives: Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Tobler NS, Ringwalt CL, Flewelling RL. How effective is drug abuse resistance education? A meta-analysis of Project DARE outcome evaluations. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1394–1401. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.9.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley K, Pallas D, Forcehimes AA, Houck J, Bogenschutz MMP, Keyser-Marcus L, Svikis D. Effect of Job Skills training on employment and job seeking behaviors in an American Indian substance abuse treatment sample. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2010;33:181–192. doi: 10.3233/JVR-2010-0526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb LM, Galanter M, McDowell D, Lifshutz H, Dermatis H. Medical student and patient attitudes toward religion and spirituality in the recovery process. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1996;22:549–561. doi: 10.3109/00952999609001680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge DR, Limb GE. Conducting spiritual assessments with Native Americans: Enhancing cultural competency in social work practice courses. Journal of Social Work Education. 2010;46:265–284. [Google Scholar]

- Holm S. A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics. 1979;6(2):65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Iritani BJ, Hallfords DD, Bauer DJ. Crystal methamphetamine use among young adults in the USA. Addiction. 2007;102:1102–1113. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch PD. Methamphetamine on the Navajo Nation. for the Navajo Area Indian Health Service Office of Planning and Evaluation, Department of Public Health, University of New Mexico; Albuquerque, New Mexico: 2007. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP. New data on the epidemiology of adult drinking and substance use among American Indians of the northern states: Male and female data on prevalence, patterns, and consequences. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center. 2001;10(2):1–26. doi: 10.5820/aian.1002.2001.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCartt AT, Rohrbaugh JW, Hammer MC, Fuller SZ. Factors assoicated with falling asleep at the wheel among long-distance truck drivers. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2000;32:493–504. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(99)00067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Alterman AI, et al. A new measure of substance abuse treatment. Initial studies of the treatment services review. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1992;180(2):101–110. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGahan PL, Griffith JA, Parente R, McLellan AT. Addiction Severity Index Composite Scores Manual. Philadelphia, PA: Treatment Research Institute; 2004. Available from http://www.tresearch.org/resources/instruments.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Baca LM. Two-year follow-up of bibliotherapy and therapist-directed controlled drinking training for problem drinkers. Behavior Therapy. 1983;14:441–448. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Taylor CA, West JC. Focused versus broad spectrum behavior therapy for problem drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1980;48:590–601. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.48.5.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Wilbourne PL. Mesa Grande: a methodological analysis of clinical trials of treatments for alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2002;97:265–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Wilbourne PL, Hettema J. What works? A summary of alcohol treatment outcome research. In: Hester RK, Miller WR, editors. Handbook of alcoholism treatment approaches: Effective alternatives. 3. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2003. pp. 13–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CM, Beals J, Novins DK, Spicer P AI-SUPERPFP Team . Drug use among two American Indian populations: prevalence of lifetime use and DSM-IV substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:29–41. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00253-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, Tonigan JS. From in-session behaviors to drinking outcomes: A causal chain for motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:1113–1124. doi: 10.1037/a0017189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH report: Alcohol dependence or abuse. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2003, 2004, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH report: State estimates of past year methamphetamine use. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH report: Methamphetamine use. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH report: Substance use and substance use disorders among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies. The DASIS Report: Primary Methamphetamine/Amphetamine Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment: 2005. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson R, McCann MJ, Flammino F, Shoptaw S, Miotto K, Rieber C, Ling W. A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches for stimulant-dependent individuals. Addiction. 2006;101:267–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear S, Crevecoeur DA, Rawson RA, Clark R. The rise in methamphetamine use among American Indians in Los Angeles county. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center. 2007;14(2):1–15. doi: 10.5820/aian.1402.2007.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LR, Rosa C, Forcehimes AA, Donovan DM. Research partnerships between academic institutions and American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes and organizations: Effective strategies and lessons learned in a multi-site CTN study. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.596976. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valle SK. Interpersonal functioning of alcoholism counselors, treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1981;42:783–790. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1981.42.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen PJ, Cox JL. Multicultural education and training in religion and spirituality. In: Verhagen PJ, van Praag HM, López-Ibor JJ Jr, Cox J, Moussaoui D, editors. Religion and psychiatry: Beyond boundaries. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 587–613. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice. 2006;7(3):312–323. doi: 10.1177/1524839906289376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson A. Predictors of psychostimulant use by long-distance truck drivers. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;166:1320–1326. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RS, Joe JR. Some Thoughts About the Epidemiology of Alcohol and Drug Use Among American Indian/Alaska Native Populations. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2009;8(3):223–241. doi: 10.1080/15332640903110443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]