Abstract

ibeA is a virulence factor found in some extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) strains from the B2 phylogenetic group and particularly in newborn meningitic and avian pathogenic strains. It was shown to be involved in the invasion process of the newborn meningitic strain RS218. In a previous work, we showed that in the avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC) strain BEN2908, isolated from a colibacillosis case, ibeA was rather involved in adhesion to eukaryotic cells by modulating type 1 fimbria synthesis (M. A. Cortes et al., Infect. Immun. 76:4129–4136, 2008). In this study, we demonstrate a new role for ibeA in oxidative stress resistance. We showed that an ibeA mutant of E. coli BEN2908 was more sensitive than its wild-type counterpart to H2O2 killing. This phenotype was also observed in a mutant deleted for the whole GimA genomic region carrying ibeA and might be linked to alterations in the expression of a subset of genes involved in the oxidative stress response. We also showed that RpoS expression was not altered by the ibeA deletion. Moreover, the transfer of an ibeA-expressing plasmid into an E. coli K-12 strain, expressing or not expressing type 1 fimbriae, rendered it more resistant to an H2O2 challenge. Altogether, these results show that ibeA by itself is able to confer increased H2O2 resistance to E. coli. This feature could partly explain the role played by ibeA in the virulence of pathogenic strains.

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli is a bacterial species found mainly in the gut of humans and warm-blooded animals (53). Besides commensals, a number of strains are responsible for intestinal or extraintestinal infections, the former being grouped under the acronym IPEC (for intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli) and the latter by the acronym ExPEC (for extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli) (31). In humans, ExPEC isolates are mainly isolated from cases of urinary tract infections, neonatal meningitis, and septicemia (49). E. coli strains isolated from avian species (called APEC, for avian pathogenic E. coli) are closely related to strains from the ExPEC group, in terms of both phylogeny and virulence gene profiles (18, 40, 48).

Such a diversity is due in part to the plasticity of the E. coli genome, which allows one to distinguish between a core genome that is present in all E. coli strains and a set of accessory genes that confer specific properties and that are found in only a fraction of E. coli strains (38, 54).

Some of these accessory genes provide the bacteria with specific properties that play roles in the different steps of the infectious process. Concerning APEC strains, studies have identified a few genes that are required for full virulence of the bacteria. Among these are the aerobactin iron capture system, the tsh gene, encoding a temperature-sensitive hemagglutinin, the phosphate transport (pst) system, and the vacuolating toxin-encoding gene vat (14, 15, 33, 45). Our laboratory has been searching for new virulence genes using different screening strategies (21, 47, 50). Based on the observation that APEC strains shared many properties with neonatal meningitis E. coli (NMEC) strains and on the identification of ibeA as a virulence gene of the neonatal meningitis strain RS218, we investigated the role of ibeA in the virulence of APEC (20, 27). In the prototypical neonatal meningitis E. coli strain RS218, inactivating ibeA caused a significant decrease in the invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells and decreased its ability to cause meningitis (27). In the APEC strain BEN2908, the deletion of ibeA led to a significant reduction of virulence (20). So far, the precise function of IbeA has remained elusive and controversial, as some authors suggest it could be an adhesin, while our studies have shown no such role in APEC strain BEN2908 (9, 59, 60).

In a previous study, we showed that ibeA was indeed involved in adhesion of strain BEN2908 to eukaryotic cells but only indirectly via the modulation of the synthesis of type 1 fimbriae (9). In fact, an ibeA mutant is less adhesive to human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs) than the wild-type BEN2908, and this feature is correlated with a decrease in type 1 fimbria expression (9). However, this observation is unlikely to explain the decrease in virulence for chickens of an ibeA mutant, as a derivative of strain BEN2908 lacking the entire type 1 fimbria operon is still virulent (39). We therefore concluded that the decreased expression of type 1 fimbriae could not solely explain the decreased virulence of the ibeA mutant. A correlate is that IbeA protein must be involved in other cellular processes that take part in bacterial virulence.

We previously observed that IbeA contains a putative FAD binding domain (E value, 6.8 e−06; http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/) and is predicted to be located in the cytoplasmic fraction of E. coli (9). A more recent search indicated that IbeA belongs to the Pfam12831 protein family, which are annotated as FAD-dependent oxidoreductases (E value, 3.06 e−83; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Moreover, IbeA is annotated as a putative dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase, a class of enzymes that are involved in oxidoreduction reactions. For instance, the E. coli dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase is an oxidoreductase that participates in electron transfer reactions within three multiproteic enzyme complexes: pyruvate dehydrogenase, 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, and the glycine cleavage system (Ecocyc.org). In addition, IbeA shares similarities with other oxidoreductases belonging to the FixC family, similarities that extend over the FAD binding domain into the first 150 amino acids of IbeA. Genes encoding proteins belonging to the FixC family have been studied in several nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Their exact functions still remain to be elucidated, but they are proposed to be involved in oxidoreductive reactions. For example, in Rhodospirillum rubrum, a FixC homologue would belong to a complex involved in electron transfer to nitrogenase, and a fixC mutant of this bacterium presents metabolic alterations reflecting an imbalance in its redox status (16). These data suggest that IbeA is involved in some sort of oxidoreductive reaction or regulation of the cellular redox status.

In this work, we further characterized IbeA by determining its subcellular localization and by investigating its contribution to oxidative stress resistance. Our results led us to suggest that IbeA is involved in H2O2 resistance in E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids are described in Table 1. E. coli strains were grown in LB-Lennox medium (35) or in M9 medium supplemented with 10 mM glucose as the carbon source and with trace salts (15 mg · liter−1 Na2EDTA · 2H2O, 4.5 mg · liter−1 ZnSO4 · 7H2O, 300 μg · liter−1 CoCl2 · 6H2O, 1 mg · liter−1 MnCl2 · 4H2O, 1 mg · liter−1 H2O, 1 mg · liter−1 H3BO3, 400 μg · liter−1 Na2MoO4 · 2H2O, 3 mg · liter−1 FeSO4 · 7H2O, 300 μg · liter−1 CuSO4 · 5H2O) and thiamine (0.1 g · liter−1) (M9sup medium).

Table 1.

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Designation | Relevant characteristic(s) or sequence | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | |||

| BEN2908 | Avian ExPEC O2:K1:H5 Nalr | 12 | |

| BEN2908 ΔibeA | 9 | ||

| BEN2908 ΔGimA | This study | ||

| MG1655 | F− λ− ilvG mutant rfb-50 rph-1 | E. coli Genetic Stock Center | |

| MG1655 Δfim | MG1655 ΔfimAICDFGH::cat | 32 | |

| AAEC198A | MG1655 fimA::lacZ | 3 | |

| Plasmids | |||

| pUC13 | Ampr, lacZα | 26 | |

| pUC23A | ibeA gene cloned in pUC13 | 26 | |

| pKD4 | Kanr, template plasmid | 10 | |

| pKD46 | Ampr, λ Red recombinase gene | 10 | |

| pCP20 | Cmr Ampr, yeast Flp recombinase gene, FLP | 10 | |

| pHSG575 | 51 | ||

| pSU315 | Kanr, influenza virus HA epitope | 56 | |

| Primers | |||

| ibeA::HA | MC1 | ACGGTACAGGAACGCTTACAGCAAAATGGCGTAAAAGTCTTTTTATCCGTATGATGTTCCTGAT | |

| MC2 | GACATAAAAACTGGGTTTTTCTTTCATAACTTTATTCCCTGCATATGAATATCCTCCTTAG | ||

| ibeA | MC3 | TGTCGAATTCAAATTGGTCGTACAACATTA | |

| MC5 | TAATGGATCCGCAGAACATGGAATTTTGAC | ||

| frr | PG 198 | GCGTAGAAGCGTTCAAAACC | |

| PG 199 | CAAGATCGGACGCCATAATC | ||

| katE | MF67 | AAGCGATTGAAGCAGGCGA | |

| MF68 | CGGATTACGATTGAGCACCA | ||

| osmC | MF71 | GCGGGAAGGGAACAGTATCTA | |

| MF72 | CATCGGCGGTGGTATCAATC | ||

| sodC | MF77 | ATCTGAAAGCATTACCTCCCG | |

| MF78 | TCGCCTTGCCGTCATTATTG | ||

| yfcG | MF81 | GAGGCGAGAACTACAGCATTG | |

| MF82 | CTATCCGAACGCTCATCACC | ||

| yjaA | MF83 | CTGGAAATGAATGAGGGCG | |

| MF84 | TGGATGTGGAACTGGCGATA | ||

| pqiA | MF73 | GTGAAACTGATGGCTTACGGC | |

| MF74 | TACAACAGGAGCACGAACGC | ||

| iscS | MF65 | CAGTTTATGACGATGGACGGA | |

| MF66 | TGGTGATGATGTGCTTGCC | ||

| sufA | MF79 | TTTATTGATGGCACGGAAGTCG | |

| MF80 | TTTCGCCACAGCCACATTCA | ||

| GimA mutant | MF93 | TAGGTCACAATTAGTGGGAGGCTCTGATTGCTGCTTTCAAGGCCGGAAGCCATTGTGTAGGCTGGAGCTG | |

| MF94 | TCAGGCCTTTGCTTCGTTGAAGCGCAGTAAACGGAAACCTGTAGAAGCATATGGTCCATATGAATATCCTCC | ||

| Upstream of GimA | MC52 | ACAGTGTTTTATCTTTGGCG | |

| Downstream of GimA | MC63 | ACCGGATGAATACCCGCATG | |

| Kanr cassette | PG328 | CGGCCACAGTCGATGAATCC |

Cells were first grown overnight in LB medium, harvested, and washed twice in M9sup medium before concentration to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 3. Cells were then inoculated in M9sup medium at a 60-fold dilution. E. coli strains were grown aerobically at 37°C; growth was monitored by determining the OD600. Ampicillin (100 μg · ml−1 for E. coli BEN2908 derivatives and 50 μg · ml−1 for other E. coli strains), kanamycin (50 μg · ml−1), and nalidixic acid (30 μg · ml−1) were used when necessary.

DNA techniques and strain constructions.

Restriction endonucleases (New England BioLabs) were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA fragments were purified from agarose gels by use of the Nucleospin Extract II purification kit (Macherey-Nagel).

Primers used in this study are described in Table 1. PCRs were performed with an Applied Biosystems model 9700 apparatus, using 1 U Taq DNA polymerase from New England BioLabs in 1× buffer, a 200 μM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 0.8 μM each primer, and 10 ng of chromosomal DNA in a 50-μl reaction volume. Cycling conditions were 1 cycle of 5 min at 95°C; 30 cycles of 10 s at 95°C, 10 s at 52°C, and 1 min/kb at 72°C; and a final extension of 5 min at 72°C. PCR products were separated in 1% agarose gels for 1 h at 10 V/cm of gel.

A derivative of strain BEN2908 carrying a C-terminal hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged ibeA gene was obtained using pSU315 and the method described by Uzzau et al. with primers MC1 and MC2 (56). From the strain obtained, the HA-tagged ibeA gene was then amplified using primers MC3 and MC5, and the PCR fragment was digested using EcoRI and BamHI and subcloned in pHSG575 cut with the same enzymes.

Deletion of the GimA genomic region was obtained as described by Datsenko and Wanner (10) using primers MF93 and MF94. The replacement of GimA by the Kanr cassette was confirmed by PCR using primers MC52 and PG328. The Kanr cassette was then removed using plasmid pCP20. The deletion of GimA was confirmed by PCR using primers MC52 and MC63.

Subcellular localization of IbeA protein.

Cells were grown in LB medium to an OD600 of 0.5. The periplasmic fraction was collected as described by Nossal and Heppel (41): bacteria from 1 ml of culture were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 30 μl of TSE buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.2, 5 mM EDTA, 20% sucrose) (41). The suspension was incubated for 10 min on ice and centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 × g, and pelleted bacteria were quickly resuspended in 30 μl of Thypo buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.2, 0.5 mM MgCl2). After 10 min on ice, bacteria were pelleted and the supernatant kept as the periplasmic fraction. Cytoplasmic and membrane fractions were then collected as described in reference 28: after osmotic shock, bacteria were resuspended in 50 μl of lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg · ml−1 lysozyme), frozen at −80°C for 5 min, and quickly thawed at 37°C for 5 min. Lysed bacteria were then centrifuged, the pellet was kept as the membrane fraction, and the supernatant was kept as the cytoplasmic fraction.

Western blot analysis.

Samples were loaded on an SDS-PAGE gel, blotted on a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and used for Western blot detection of either IbeA, RpoS, or the control proteins ß-galactosidase (cytoplasmic protein), OmpA (outer membrane protein), SecG (inner membrane protein), and MalE (periplasmic protein). Anti-HA antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) analysis.

Total RNA was extracted from 500 μl of bacterial liquid culture (OD600 of 0.45). Briefly, bacteria were mixed with 1 ml of RNAprotect bacterial reagent (Qiagen) by vortexing for 5 s. After a 5-min incubation at room temperature, the mix of bacteria and RNAprotect bacterial reagent was centrifuged for 10 min at 5,000 × g. The supernatant was removed and the pellet was stored for 1 night at −80°C. The next day, total RNA was extracted from the pellet using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. To avoid any contamination of the extracts by residual genomic DNA, an on-column DNase digestion was performed during RNA purification by using the RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen). The quality of the RNAs was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis, and a Nanodrop device was used for the determination of the ratios of absorbance at 260 and 280 nm and at 260 and 230 nm.

Quantitative RT-PCR was performed as described by Chouikha et al. (7). Briefly, gene-specific reverse transcription of RNAs was performed with Superscript RT III (Invitrogen), using primer PG 199 for frr (housekeeping gene), MF67 for katE, MF71 for osmC, MF77 for sodC, MF81 for yfcG, MF83 for yjaA, MF73 for pqiA, MF65 for iscS, and MF79 for sufA. Samples without RT were concurrently prepared and analyzed for the absence of contaminating genomic DNA. Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis was performed in an iCycler system (Bio-Rad) using Absolute quantitative PCR SYBR green mix (ABgene). Four microliters of cDNAs obtained as described above and diluted 10-fold in nuclease-free distilled water was used for qPCR. The PCR program consisted of 35 amplification/quantification cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min, with signal acquisition at the end of each cycle. Primers used for qPCR were PG198/PG199 for frr, MF67/MF68 for katE, MF71/MF72 for osmC, MF77/MF78 for sodC, MF81/MF82 for yfcG, MF83/MF84 for yjaA, MF73/MF74 for pqiA, MF65/MF66 for iscS, and MF79/MF80 for sufA. Equation 1 from Pfaffl was used to determine the expression ratios, using frr as a housekeeping gene standard (46).

Determination of cytoplasmic redox potential by fluorescence.

The plasmid pHOJ124, carrying an isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible gene encoding the yellow fluorescent protein rxYFP149202, was introduced into strains BEN2908 and BEN2908 ΔibeA (43). Cells then were grown until the mid-exponential growth phase in glucose-containing M9sup medium in the presence of 1 mM IPTG before fluorescence measurements were performed as described previously (43). Briefly, at an OD600 of 0.45, 900 μl of the culture was transferred to a prewarmed cuvette (30°C) and fluorescence monitored continuously at 525 nm, with excitation at 505 nm using a Quanta Master spectrofluorometer (PTI, NJ) equipped with a 75-W xenon lamp. After a stable baseline was obtained (denoted Finit), the oxidation state of rxYFP149202 was determined by reading the fluorescence after successive addition of 50 μl 3.6 mM 4-DPS (Fox; Sigma-Aldrich) and 100 μl 1 M dithiothreitol (Fred) to fully oxidize and reduce the protein, respectively. The fraction of oxidized rxYFP149202 was then calculated from the expression 1 − (Finit − Fox)/(Fred − Fox).

H2O2 resistance assay.

Cells were grown in glucose-containing M9sup medium for 4 h to an OD600 of 0.45, corresponding to the mid-exponential growth phase. H2O2 was added to the growth medium to a final concentration of 25 mM. Aliquots were collected over time and immediately diluted 10 times in M9sup medium supplemented with 10 U · ml−1 of bovine liver catalase (Sigma-Aldrich) to ensure the removal of H2O2. Survival analysis was performed by plating on LB agar serial dilutions in physiological water containing 10 U · ml−1 of bovine liver catalase.

Superoxide anion resistance assay.

Cells were grown in glucose-containing M9sup medium in the absence (negative control) or in the presence of 1 or 10 μM intracellular superoxide generator methyl viologen in the growth medium. The growth was monitored by determining the OD600.

Motility assays.

Motility of strains BEN2908 and BEN2908 ΔibeA was evaluated as described previously. Briefly, 5 μl of a log-phase culture was spotted onto a soft LB-agar plate (0.25% agar), and the plate was then incubated at 37°C for 5 h.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis of H2O2 sensitivity and quantification of gene expression were done by applying the Student's t test.

RESULTS

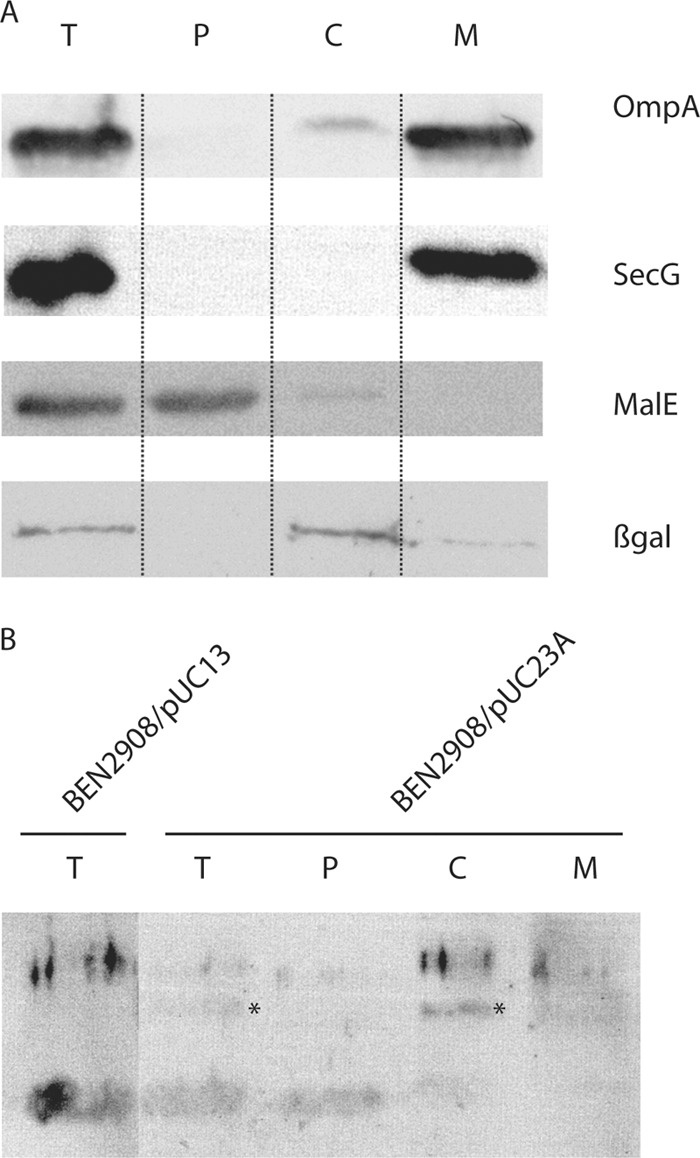

The IbeA protein is located in the cytoplasm of strain BEN2908.

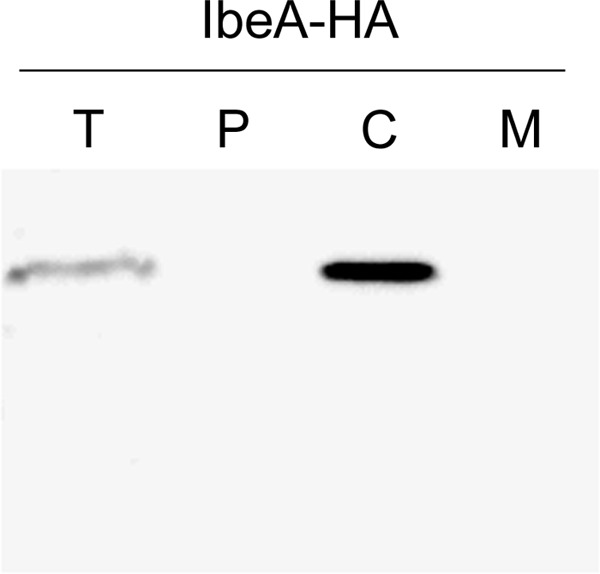

To confirm bioinformatic analysis, we decided to first investigate the precise localization of IbeA. Because the expression of IbeA was found to be very low, consistent with the low expression of the ibeA gene (7), the analysis was performed using strains transformed with plasmid pUC23A (or pUC13 as a control), which carries ibeA and most of the upstream sequence between ibeR and ibeA (26). It is therefore likely that ibeA is expressed under the control of its own promoter. Subcellular compartments corresponding to the cytoplasm, to the periplasm, and to the membranes (both outer and inner) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting. Proteins of known localization were used as controls: ß-galactosidase for the cytoplasmic compartment, MalE for the periplasmic fraction, SecG for the inner membrane, and OmpA for the outer membrane. Using the protocol described by Ishidate et al. for E. coli K-12 (28), the periplasmic fraction of strain BEN2908 cofractionated with cytoplasmic proteins while control membrane proteins fractionated in the membrane fraction as expected. In this case, IbeA was not recovered into the insoluble fraction containing membrane proteins but was instead collected into the soluble fraction containing both cytoplasmic and periplasmic proteins (data not shown). We then optimized the protocol by including an osmotic shock as a first step to recover periplasmic proteins before lysing bacteria (41). As indicated in Fig. 1A, all control proteins were found in their correct fraction. When these fractions were analyzed with an anti-IbeA antibody, IbeA was found to be located in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1B). Analysis of the culture supernatant indicated that IbeA was not released in the supernatant (data not shown). Because several unspecific bands were obtained with the IbeA antibody, additional experiments were performed. We decided to investigate the localization of an IbeA protein tagged with a C-terminal HA epitope. As indicated in Fig. 2, the IbeA-HA protein was also found in the cytoplasmic fraction. The possibility that the HA tag interfered with a potential membrane localization of IbeA is unlikely, since it has already been shown not to modify the secretion or the localization to the membrane of a number of other proteins (2, 19, 34). Altogether, these results are in agreement with the predicted localization of IbeA in the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli.

Fig 1.

Subcellular localization of the IbeA protein. (A) Subcellular compartments of strain BEN2908/pUC23A were obtained as indicated in Materials and Methods and separated on an SDS-PAGE gel. Control proteins OmpA (outer membrane), SecG (inner membrane), MalE (periplasm), and ß-galactosidase (cytoplasm) were detected to validate the fractionation protocol. T, total cell extract; P, periplasmic fraction; C, cytoplasmic fraction; M, membrane fraction. (B) The IbeA protein was detected by Western blotting using an anti-IbeA antibody. The band corresponding to IbeA is indicated by an asterisk.

Fig 2.

Subcellular localization of the IbeA-HA protein. Subcellular compartments of strain BEN2908/pHSG-ibeA::HA were separated as indicated in Materials and Methods and separated on an SDS-PAGE gel. The IbeA-HA protein was detected by Western blotting using an anti-HA antibody. T, total cell extract; P, periplasmic fraction; C, cytoplasmic fraction; M, membrane fraction.

BEN2908 ΔibeA is more sensitive to H2O2 killing.

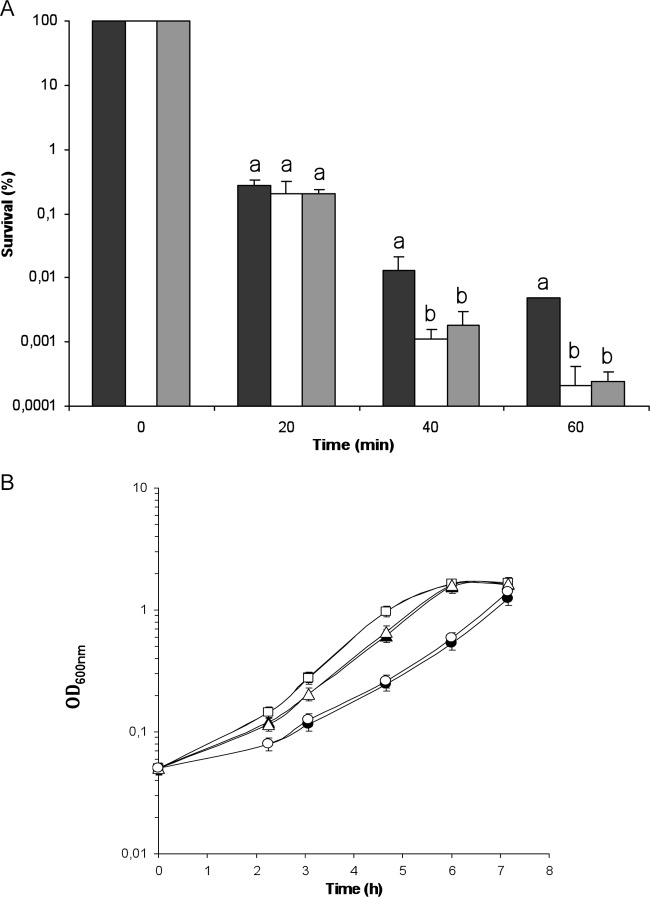

Sensitivity to 25 mM H2O2 was analyzed during exponential growth in wild-type BEN2908 and its ΔibeA derivative, which were grown in M9sup-glucose medium. Under these culture conditions, the growth levels of strains BEN2908 and BEN2908 ΔibeA were identical. Prior experiments had indicated that a concentration of 25 mM H2O2 was sufficient to kill bacteria but was low enough that the survival could be measured during a 1-h assay (29, 37). While the wild-type strain showed a progressive pattern of killing during H2O2 exposure, with a 4-log reduction of CFU after 40 min of exposure and a 4.5-log decrease in survival after 60 min, the ΔibeA mutant presented a much more dramatic phenotype (Fig. 3A). Indeed, from 40 min of H2O2 stress onwards, it presented a survival rate significantly lower than that of the wild-type strain, with a 1-log increased mortality. Sixty min after H2O2 addition, the survival difference reached 1.5 logs (Fig. 3A). These findings suggested that ibeA was involved in H2O2 resistance in E. coli BEN2908. We also investigated the sensitivity of BEN2908 and its ΔibeA mutant to another kind of oxidative stress, the intracellular generation of superoxide anions by methyl viologen. We monitored the growth of the two strains in M9sup-glucose medium in the absence (negative control) or in the presence of the oxidant. In the presence of 1 μM methyl viologen, the growth rate was slightly decreased in an equivalent manner for the two strains compared to the negative-control conditions. In the presence of a greater dose of methyl viologen (10 μM), the growth was further decreased, but still no difference was observable between BEN2908 and its ΔibeA mutant. Thus, it seemed that ibeA did not intervene in resistance to intracellular superoxide stress (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

Sensitivity to oxidants of BEN2908 and its ΔibeA and ΔGimA derivatives. (A) The bacteria were grown in glucose-containing M9sup medium until the mid-exponential phase of growth (OD600 of 0.45) and were challenged with 25 mM H2O2 added directly in the growth medium. The data are represented as percent survival relative to unstressed cells (t = 0 min). The results are the means from at least three independent experiments. Error bars show the standard deviations. Black bars, BEN2908 wild type; white bars, BEN2908 ΔibeA; gray bars, BEN2908 ΔGimA. For each time, statistically significant differences in survival rates (Student's t test; P < 0.05) are indicated by different letters (a and b). (B) The bacteria were grown in glucose-containing M9sup medium in the absence (squares) or in the presence of 1 μM (triangles) or 10 μM (circles) intracellular superoxide generator methyl viologen in the growth medium. The results are the means from at least three independent experiments. Error bars show the standard deviations. Black symbols, BEN2908 WT; white symbols, BEN2908 ΔibeA.

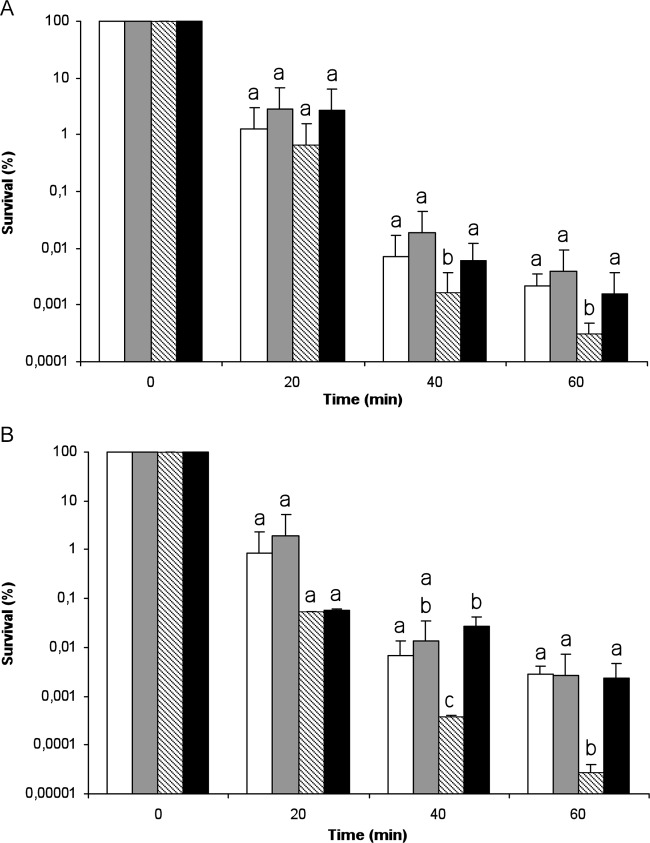

To check that the H2O2 sensitivity of the ΔibeA mutant was actually due to the deletion of ibeA, we analyzed as described above the H2O2 sensitivity of BEN2908 and its ΔibeA mutant complemented either with the pUC23A plasmid carrying ibeA (26) or with the empty vector pUC13. Results indicated that the ΔibeA mutant containing pUC23A presented the same pattern of killing as strain BEN2908 transformed either with pUC23A or pUC13, with no significant difference in survival rates (Fig. 4A). Thus, we concluded that expression of ibeA in trans from pUC23A restored the survival of strain BEN2908 ΔibeA to a level similar to that of the wild-type strain. Altogether, our results show that the deletion of ibeA is actually responsible for the lower resistance to H2O2 of the ΔibeA mutant (Fig. 4A).

Fig 4.

Sensitivity to H2O2 killing in strains carrying the pUC23A and pUC13 plasmids. Sensitivity to H2O2 of BEN2908 ΔibeA (A) or BEN2908 ΔGimA (B) carrying either the pUC13 vector or the ibeA+ pUC23A plasmid was compared to that of the wild-type strain BEN2908 carrying the same plasmids. Bacteria were treated with H2O2 as described in the legend for Fig. 3. The data are represented as percent survival relative to unstressed cells (t = 0 min). The results are the means from at least three independent experiments. Error bars show the standard deviations. For each time, statistically significant differences in survival rates (Student's t test; P < 0.05) are indicated by different letters (a and b). White bars, BEN2908/pUC13; gray bars, BEN2908/pUC23A; dashed bars, BEN2908 ΔibeA/pUC13 (A) or BEN2908 ΔGimA/pUC13 (B); black bars, BEN2908 ΔibeA/pUC23A (A) or BEN2908 ΔGimA/pUC23A (B). For each time, statistically significant differences in survival rates (Student's t test; P < 0.05) are indicated by different letters (a, b, and c).

Some E. coli genes involved in the oxidative stress response are downregulated in the ΔibeA mutant.

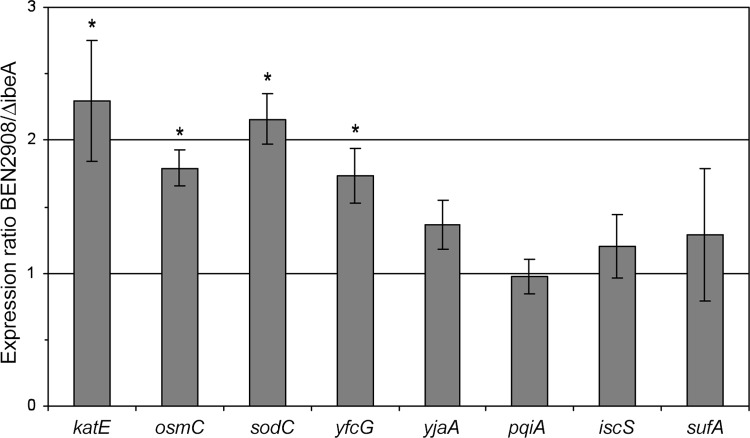

To identify metabolic defaults that could be responsible for the increased sensitivity to H2O2 of the ΔibeA mutant, we determined by real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis the level of transcripts of a range of genes involved in the oxidative stress response in E. coli during exponential growth in M9sup-glucose medium: katE, osmC, sodC, yfcG, yjaA, pqiA, iscS, and sufA (Fig. 5). These genes code for the monofunctional catalase hydroperoxidase II KatE, the osmotically inducible peroxidase OsmC, the periplasmic copper/zinc-dependent superoxide dismutase SodC, the disulfide bond reductase YfcG, the stress response protein YjaA, the paraquat-inducible protein PqiA, and two proteins involved in iron-sulfur cluster assembly and repair, the cysteine desulfurase IscS and the Fe-S transport protein SufA, respectively.

Fig 5.

Quantification of the expression of genes involved in the oxidative stress response. Expression of katE, osmC, sodC, yfcG, yjaA, pqiA, iscS, and sufA in BEN2908 wild-type and ΔibeA strains was measured by quantitative real-time PCR as described in Materials and Methods using the frr gene as a housekeeping gene standard. Results are ratios of relative expression in the BEN2908 wild type compared to expression in the ΔibeA mutant. Results are the means from at least three independent experiments. Error bars show the standard deviations. An asterisk indicates that the expression ratio of BEN2908 wild type to ΔibeA was significantly different from 1 (P < 0.05 by Student's t test).

Whereas the levels of transcripts of some genes, like yjaA, pqiA, iscS, and sufA, were not significantly affected by the deletion of ibeA, we found that the expression of katE, sodC, osmC, and yfcG was moderately reduced in the ibeA mutant (2.3-, 2.16-, 1.79-, and 1.73-fold, respectively) compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 5). We next performed these transcription analyses with strains carrying plasmid pUC13 (empty vector) or pUC23A (carrying ibeA). The presence of either plasmid did not modify the expression of genes which were downregulated in the ibeA mutant (data not shown). Furthermore, in the presence of both plasmids, the differences observed above between ibeA+ and ibeA mutant strains for katE, sodC, osmC, and yfcG were not detected. These results suggest that, during exponential growth, the expression of genes involved in oxidative stress resistance mechanisms is reduced in the ΔibeA mutant. However, the lack of complementation at the transcriptional level indicates that alterations other than these downregulations in gene expression also contribute to the decreased survival of the ibeA mutant against oxidative stress.

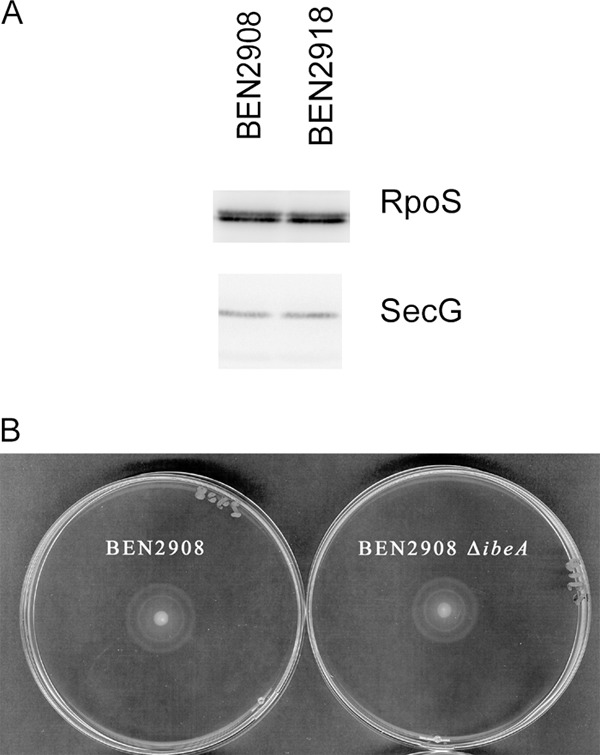

Alterations of RpoS expression are not responsible for the decreased resistance of strain BEN2908 ΔibeA.

RpoS has been described as a potential regulator for the expression of some of the genes described above. Regulation of gene expression by RpoS mainly involves variations in the cellular level of the RpoS protein (23, 58). We therefore analyzed whether the deletion of ibeA had any influence on the amount of RpoS present in the bacteria by Western blotting. Results indicate that the amount of RpoS is not disturbed by the deletion of ibeA (Fig. 6A). We used SecG as a control for the amount of protein loaded on the gel. In addition, we investigated whether deletion of ibeA had any influence on the motility of strain BEN2908, since RpoS has been shown to regulate the motility of E. coli strains by modulating the expression of the master regulator flhDC (13, 55). We therefore expected the motility to be modified in case the deletion of ibeA had had an effect on the cellular level of RpoS. Clearly, this was not the case. The motilities of strains BEN2908 and BEN2908 ΔibeA were identical (Fig. 6B).

Fig 6.

Influence of the ibeA deletion on cellular amount of RpoS and motility of strain BEN2908. (A) Bacteria were grown to mid-log phase as described for the H2O2 survival assays. The equivalent of 108 bacteria per well were loaded on an SDS-PAGE gel, and the amount of RpoS in bacteria was analyzed by Western blotting. (B) Five microliters of a mid-log-phase culture was spotted on an LB agar plate (0.25% agar) and incubated at 37°C for 5 h.

The deletion of ibeA does not disturb intracellular redox status.

Because of the reduced survival to the oxidative stress response of strain BEN2908 ΔibeA, we tried to determine if this phenotype could be linked to a disruption of the cellular redox potential of bacteria. To this end, we evaluated the proportion of cytoplasmic oxidized disulfide bonds by using an engineered fluorescent protein, rxYFP149202, as a probe for redox changes (43). In this protein, formation of a disulfide bond between a pair of redox-active cysteines is reversible and results in a >2-fold decrease in the intrinsic fluorescence. Thus, we introduced the plasmid pHOJ124, carrying the gene encoding this reporter protein under the control of an IPTG-inducible promoter, into BEN2908 wild type and ΔibeA. We then determined the rate of oxidized rxYFP149202 by spectrofluorimetry during mid-exponential growth in M9sup-glucose medium. The proportion of oxidized reporter was similar and very high in the two strains: 82.8% (±5%) and 81.7% (±4%) for BEN2908 wild type and ΔibeA, respectively. Thus, the deletion of ibeA does not seem to have any effect on intracellular redox status.

ibeA, independently of GimA, is sufficient to increase resistance to H2O2 in strain BEN2908.

When ibeA is present in an E. coli ExPEC strain, it is always located in the structure of the GimA genomic region (24). This suggests that ibeA acts in synergy with other genes belonging to GimA. Because GimA contains two other open reading frames (ORFs), cglE and cglD, also predicted to encode oxidoreductases, it could be that the increased sensitivity of the ΔibeA mutant to H2O2 results from an indirect effect of the deletion on the functioning of GimA.

To elucidate this, we constructed a derivative of strain BEN2908 in which the whole GimA sequence was deleted, and we analyzed its resistance to H2O2 in the manner described for Fig. 3A. The ΔGimA mutant presented exactly the same pattern of killing as the ΔibeA mutant, i.e., it showed an important loss of survival compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 3A). Thus, as was the case for the ΔibeA mutant, the ΔGimA mutant survival rate was 1 and 1.5 logs lower than that of BEN2908 after 40 and 60 min of stress exposure, respectively (Fig. 3A). These results showed that H2O2 stress resistance was actually a function performed by GimA.

The ΔGimA mutant was then transformed with either pUC13 or pUC23A, and the survival rates of these strains were monitored during an H2O2 challenge (Fig. 4B). As observed for the ΔibeA mutant, the ΔGimA mutant containing pUC13 showed increased sensitivity to H2O2 compared to BEN2908 strains transformed with either pUC13 or pUC23A. This difference in survival was significant from 40 min of H2O2 stress onwards and reached about 2 logs after 60 min of stress exposure (Fig. 4B). Thus, the expression of ibeA alone was able to complement the deleterious impact of GimA deletion on BEN2908 H2O2 stress resistance. Therefore, these results showed that ibeA alone, without any other GimA component, could improve BEN2908 H2O2 stress resistance.

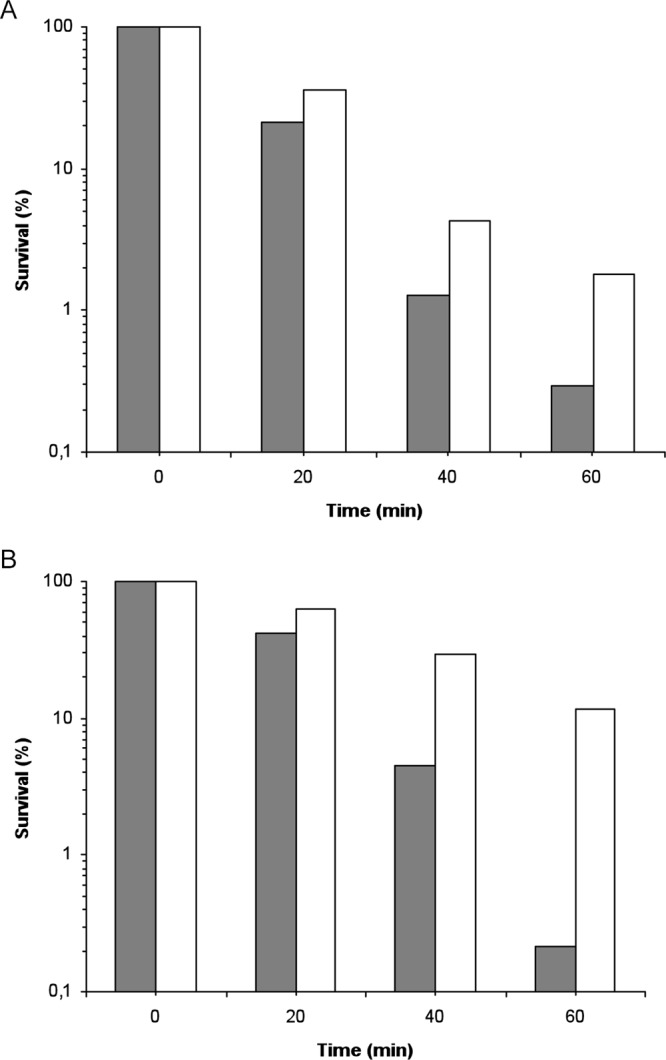

Heterologous expression of ibeA in E. coli K-12 increases its H2O2 stress resistance.

We then undertook to determine whether ibeA by itself could exert an effect on oxidative stress resistance in a commensal E. coli strain. The E. coli strain MG1655 was therefore transformed with either pUC13 or pUC23A, and the survival of the two strains was analyzed during an H2O2 challenge performed on mid-exponential-growth cultures as previously described. Despite a great variability in survival rates from one experiment to another, E. coli MG1655 containing pUC23A, and therefore expressing ibeA, always showed greater resistance to H2O2 killing than the same strain transformed with the empty vector pUC13. Data from a representative experiment are presented in Fig. 7A. In this experiment, E. coli MG1655 containing pUC23A presented 6-fold more CFU after 60 min of stress exposure and thus was significantly more resistant to H2O2 than its counterpart carrying the empty vector pUC13 (Fig. 7A). These results show that the ibeA gene can confer increased H2O2 resistance to a commensal E. coli K-12 strain and thus can exert this function in a nonpathogenic background.

Fig 7.

Increased resistance to H2O2 killing of strain E. coli K-12 MG1655 (A) or MG1655 Δfim (B) containing the ibeA gene in trans. E. coli K-12 strain MG1655 (A) or MG1655 Δfim (B) containing either the pUC13 vector (gray bars) or the pUC23A plasmid expressing the ibeA gene (white bars) was treated as described in the legend for Fig. 3. The data are represented as percent survival relative to unstressed cells (t = 0 min). For the two strains, the results are representative patterns of survival from at least three independent experiments.

We had previously shown that, in strain BEN2908, the expression of type 1 fimbriae was decreased in the BEN2908 ΔibeA mutant (9). It was therefore possible that the increased resistance observed when ibeA is expressed in trans in E. coli K-12 MG1655 is linked to a metabolic alteration due to a modification of type 1 fimbria expression. We investigated this possibility by repeating the H2O2 resistance assays with a derivative of strain MG1655 deleted of the fim operon. As with strain MG1655, the resistance to H2O2 was increased in strain MG1655 Δfim carrying ibeA compared to the same strain carrying the empty vector (Fig. 7B). In addition, we showed that expression of the fimA promoter was not modified in strain AAEC198A carrying a fimA::lacZ fusion in the presence of plasmids pUC13 or pUC23A: ß-galactosidase activity (in Miller units) was 201 (±46) and 176 (±35), respectively. We therefore concluded that the influence of the ibeA gene on H2O2 resistance was independent of the expression of type 1 fimbriae in strain E. coli K-12 MG1655.

DISCUSSION

Oxidative stress resistance as a new function for ibeA in E. coli.

In this work, we demonstrated that ibeA is involved in oxidative stress resistance of E. coli BEN2908. Indeed, we showed that a ΔibeA derivative of this strain was significantly more sensitive than its wild-type counterpart during an H2O2 challenge, and that the complementation of this mutant by a plasmid expressing ibeA restored wild-type resistance to H2O2 killing.

In ExPEC strains, ibeA belongs to a 20.3-kb genomic island called GimA (25). This island contains 14 genes in addition to ibeA, some of which are predicted to encode proteins involved in carbon source metabolism and stress resistance. ibeR, which belongs to the same operon as ibeA, was studied in the meningitic strain E. coli E44. In this strain, an ibeR mutant is more sensitive to various stresses, including H2O2 killing (6). Thus, it could be possible that IbeR, which is annotated as a transcriptional regulator, is responsible for ibeA induction and, thus, for increased oxidative stress resistance in ExPEC strains.

A recent study established that, when present in an ExPEC strain, GimA is always complete, except in some cases in which a 342-bp remnant is found (24). Thus, it can be supposed that ibeA interacts with other GimA components in an organized system. Among the other components of GimA, there are two other genes predicted to encode oxidoreductases: cglD, coding for a putative glycerol dehydrogenase, and cglE, encoding a protein sharing strong similarities with IbeA. It was thus possible that the deletion of ibeA led to an imbalance in oxidoreductase expression within GimA, which could have been responsible for the oxidative stress sensitivity phenotype. Such a possibility was ruled out by the observation that, first, a BEN2908 derivative deleted for the whole GimA genomic region presented the same increased sensitivity to H2O2 as the ΔibeA mutant and that, second, the expression of ibeA alone in a strain lacking the entire GimA island was able to restore survival after H2O2 stress to a level similar to that of the wild-type strain. As a consequence, the lower resistance to H2O2 killing of the ΔibeA mutant seemed to reflect a real function brought by the ibeA gene rather than an experimental artifact.

To reinforce these observations, we added ibeA in trans to the E. coli strains MG1655 and MG1655 Δfim that both lack GimA. The resulting strains presented significantly increased H2O2 stress resistance compared to their counterpart transformed with the empty vector. Taken as a whole, our data show that ibeA alone, without any other GimA components, is actually sufficient to confer increased H2O2 stress resistance to E. coli.

The oxidative stress response is altered in the ΔibeA mutant during exponential growth.

Although these results bring new light to the contribution of IbeA to E. coli physiology, the question of its exact function still remains. The analysis of conserved domains in IbeA revealed extended similarities, encompassing an FAD binding domain, to members of the FixC family that have been found in diverse species and are thought to contribute to electron transfer reactions (16, 17). We thus propose that IbeA protein is involved in some oxidoreductive mechanisms. This suggestion is corroborated by the cytoplasmic localization of the protein that we also demonstrated in this study by different subcellular localization experiments. This feature is in accordance with all of the predictions that we obtained in a previous work using several dedicated software programs (9). Nevertheless, it is in contradiction to previous studies assigning to IbeA a direct adhesive function (59, 60). To verify our hypothesis, it is now essential that the precise reaction mediated by IbeA be determined. For this purpose, we intend to overexpress and purify IbeA to characterize its in vitro activity in future experiments.

As ibeA is implicated in H2O2 stress resistance in BEN2908, we investigated, in the ΔibeA mutant, the possibility of expression alterations of several genes involved in the oxidative stress response of E. coli. Among the genes tested, we identified four that were moderately downregulated in the mutant compared to the wild-type strain during exponential growth in minimal medium: katE, sodC, osmC, and yfcG. During aerobic growth, E. coli produces sufficient H2O2 to create toxic levels of DNA damage via the Fenton reaction (44). KatE, the monofunctional catalase hydroperoxidase II, is implicated, in association with KatG and AhpCF, in E. coli H2O2 scavenging and detoxification (44). The osmotically inducible peroxidase OsmC is able to detoxify organic hydroperoxides and, to a much lesser extent, inorganic hydrogen peroxide (36). Thus, an E. coli osmC mutant is sensitive to exposure to hydrogen peroxide and tert-butylhydroperoxide (8). The periplasmic copper/zinc-dependent superoxide dismutase SodC is responsible for superoxide anion degradation. A mutation in the gene sodC also leads to an increased sensitivity to H2O2 in E. coli (22). Finally, the disulfide bond reductase YfcG has a glutathione (GSH)-conjugating activity as well as a GSH-dependent peroxidase activity, and a mutation in the yfcG gene decreases the resistance to H2O2 in E. coli (30). However, expression data obtained with strains containing the ibeA+ plasmid pUC23A or the empty vector pUC13 failed to demonstrate a complementation of these expression data. This suggests that alterations of expression of these four genes could only partly explain the sensitivity to H2O2 killing of the ΔibeA mutant. It is more likely that other properties of the ΔibeA mutant are responsible for alterations in oxidative defense mechanisms during the exponential growth which sensitize bacteria to a subsequent H2O2 stress exposure.

The four genes katE, sodC, osmC, and yfcG belong to the RpoS regulon in different E. coli strains (4, 22, 52, 57). More specifically, katE and yfcG were shown to be under the control of rpoS during E. coli exponential growth in glucose-containing M9 medium (57), i.e., under the experimental conditions used in this study, suggesting that RpoS-dependent stress response is at least partly affected in the ΔibeA mutant. Interestingly, Chi et al. proposed that IbeR was a functional equivalent of RpoS in E. coli E44 that presents a loss-of-function mutation in the rpoS gene (6). However, our results demonstrated that the cellular level of RpoS was not affected by the ibeA mutation, and that motility, a phenotype linked to RpoS, was not disturbed in the ibeA mutant. It is therefore unlikely that the increased sensitivity to H2O2 of the ibeA mutant is linked to a modification in RpoS levels.

The downregulation of genes involved in oxidative stress resistance in the ΔibeA mutant also suggests that the cellular redox state of this strain could be affected. Nevertheless, we were unable to show any difference between BEN2908 wild-type and ΔibeA mutant strains by performing a spectrofluorimetric analysis of the two strains transformed with pHOJ124 (43), a vector expressing a yellow fluorescent protein whose fluorescence intensity depends on the redox state of the cell.

How could the increased H2O2 sensitivity of the ΔibeA mutant affect BEN2908 virulence?

In this work, we showed that ibeA is implicated in H2O2 stress resistance of E. coli BEN2908. However, the exact contribution of this phenotype to the virulence of strain BEN2908 still has to be explored. During the infection process of colibacillosis, which is mainly a disease initiated in the respiratory tract, we can identify at least two steps during which the bacteria are exposed to an oxidative stress: the response of the host's immune system and the survival phase in the respiratory tract environment.

The first step corresponds to an oxidative burst produced by chicken macrophages and heterophils after bacteria phagocytosis (11, 42). This consists of a cocktail of several reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, including superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide, and nitric oxide, which has a biocidal action on bacteria (11, 42). Thus, bacteria's ability to resist this defense mechanism will influence their survival rate inside the host and thus have an effect on their pathogenic potential. To determine the effect of ibeA and GimA deletions on E. coli BEN2908 intramacrophage survival, we performed survival challenges in the macrophage cell lines RAW264.7 (murine) and HD11 (avian). We have never been able to show any intramacrophage survival differences between BEN2908 and BEN2908 ΔibeA, suggesting that ibeA and, more globally, GimA are not involved in this infection step (data not shown).

The second hypothesis that we considered, i.e., the involvement of ibeA in bacterial survival in the respiratory tract environment, cannot be easily addressed by any experimental procedure. Nevertheless, an experimental reproduction of colibacillosis in chicken previously performed in our laboratory suggested that ibeA was involved early in the infection of chickens by strain BEN2908 (20). The lung environment presents a high oxygen tension, which could lead to a higher rate of production of reactive oxygen species, including hydrogen peroxide. Thus, the ibeA gene of E. coli BEN2908 could be responsible for an increased resistance of the bacteria to these harsh living conditions, allowing them to survive well enough to cause the disease. Such a situation has already been described for the virulence gene phgA of Streptococcus pneumoniae, which is responsible for pneumonia. In this case, phgA is also involved in resistance to H2O2 killing, but the authors were unable to show any involvement of this gene in the survival of the phagocytic respiratory burst, suggesting rather that phgA takes part in oxidative stress resistance in the lung environment (5). Finally, it was shown that E. coli survival inside nonphagocytic epithelial cells also requires protection against oxidative damage, especially a high level of SodC (1). Thus, it is possible that the ΔibeA mutant, whose sodC gene is downregulated, is less able to survive within respiratory epithelial cells.

In conclusion, results of this work shed new light on the still ill-characterized exact function of IbeA. These results, together with sequence data and previous reports in the literature, let us hypothesize that IbeA is involved in an oxidoreduction reaction that could modify the behavior of the bacteria regarding expression of virulence genes or resistance to oxidative stress. The nature of the substrate on which IbeA would act remains to be identified and deserves further study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by the Era-NET PathoGenoMics European program (grant ANR-06-PATHO-002-01) and INRA.

Plasmids pUC13 and pUC23A and anti-IbeA antibody were kindly provided by S. H. Huang (Saban Research Institute of Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA). pHSG575 was kindly provided by A. Darfeuille-Michaud (Université d'Auvergne, Clermont-Ferrand, France). pHOJ124 was kindly provided by J. R. Winther (Carlsberg Research Centre, Valby, Denmark). Strain MG1655 Δfim was kindly provided by J. M. Ghigo (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France). Strain AAEC198A was kindly provided by I. Blomfield (University of Kent, United Kingdom). Anti-SecG antibody was kindly provided by K. Ito (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan), anti-MalE antibody by T. Silhavy (Princeton University, Princeton, NJ), anti-LamB by A. Pugsley (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France), anti-OmpA by R. Lloubès (Institut de Biologie Structurale et Microbiologie, Marseille, France), and anti-RpoS by R. Hengge (Institut für Biologie-Mikrobiologie FB Biologie, Chemie und Pharmazie, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 June 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Battistoni A, et al. 2000. Increased expression of periplasmic Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase enhances survival of Escherichia coli invasive strains within nonphagocytic cells. Infect. Immun. 68:30–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Biemans-Oldehinkel E, Sal-Man N, Deng W, Foster LJ, Finlay BB. 2011. Quantitative proteomic analysis reveals formation of an EscL-EscQ-EscN type III complex in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 193:5514–5519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blomfield IC, McClain MS, Princ JA, Calie PJ, Eisenstein BI. 1991. Type 1 fimbriation and fimE mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 173:5298–5307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bouvier J, et al. 1998. Interplay between global regulators of Escherichia coli: effect of RpoS, Lrp and H-NS on transcription of the gene osmC. Mol. Microbiol. 28:971–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown JS, Gilliland SM, Basavanna S, Holden DW. 2004. phgABC, a three-gene operon required for growth of Streptococcus pneumoniae in hyperosmotic medium and in vivo. Infect. Immun. 72:4579–4588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chi F, et al. 2009. Identification of IbeR as a stationary-phase regulator in meningitic Escherichia coli K1 that carries a loss-of-function mutation in rpoS. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2009:520283 doi:10.1155/2009/520283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chouikha I, Brée A, Moulin-Schouleur M, Gilot P, Germon P. 2008. Differential expression of iutA and ibeA in the early stages of infection by extra-intestinal pathogenic E. coli. Microbes Infect. 10:432–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Conter A, Gangneux C, Suzanne M, Gutierrez C. 2001. Survival of Escherichia coli during long-term starvation: effects of aeration, NaCl, and the rpoS and osmC gene products. Res. Microbiol. 152:17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cortes MA, et al. 2008. Inactivation of ibeA and ibeT results in decreased expression of type 1 fimbriae in the extra-intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli strain BEN2908. Infect. Immun. 76:4129–4136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Desmidt M, Van Nerom A, Haesebrouck F, Ducatelle R, Ysebaert MT. 1996. Oxygenation activity of chicken blood phagocytes as measured by luminol- and lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 53:303–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dho M, Lafont JP. 1982. Escherichia coli colonization of the trachea in poultry: comparison of virulent and avirulent strains in genotoxenic chickens. Avian Dis. 26:787–797 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dong T, Schellhorn HE. 2009. Control of RpoS in global gene expression of Escherichia coli in minimal media. Mol. Genet. Genomics 281:19–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dozois CM, Daigle F, Curtiss R., III 2003. Identification of pathogen-specific and conserved genes expressed in vivo by an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:247–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dozois CM, et al. 2000. Relationship between the Tsh autotransporter and pathogenicity of avian Escherichia coli and localization and analysis of the Tsh genetic region. Infect. Immun. 68:4145–4154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edgren T, Nordlund S. 2004. The fixABCX genes in Rhodospirillum rubrum encode a putative membrane complex participating in electron transfer to nitrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 186:2052–2060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eichler K, Buchet A, Bourgis F, Kleber HP, Mandrand-Berthelot MA. 1995. The fix Escherichia coli region contains four genes related to carnitine metabolism. J. Basic Microbiol. 35:217–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ewers C, et al. 2007. Avian pathogenic, uropathogenic, and newborn meningitis-causing Escherichia coli: how closely related are they? Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297:163–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gal-Mor O, Gibson DL, Baluta D, Vallance BA, Finlay BB. 2008. A novel secretion pathway of Salmonella enterica acts as an antivirulence modulator during salmonellosis. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000036 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Germon P, et al. 2005. ibeA, a virulence factor of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Microbiology 151:1179–1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Germon P, et al. 2007. tDNA locus polymorphism and ecto-chromosomal DNA insertion hot-spots are related to the phylogenetic group of Escherichia coli strains. Microbiology 153:826–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gort AS, Ferber DM, Imlay JA. 1999. The regulation and role of the periplasmic copper, zinc superoxide dismutase of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 32:179–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hengge R. 2009. Proteolysis of sigmaS (RpoS) and the general stress response in Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 160:667–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Homeier T, Semmler T, Wieler LH, Ewers C. 2010. The GimA locus of extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli: does reductive evolution correlate with habitat and pathotype? PLoS One 5:e10877 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Huang SH, et al. 2001. A novel genetic island of meningitic Escherichia coli K1 containing the ibeA invasion gene (GimA): functional annotation and carbon-source-regulated invasion of human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Funct. Integr. Genomics 1:312–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang SH, Wan ZS, Chen YH, Jong AY, Kim KS. 2001. Further characterization of Escherichia coli brain microvascular endothelial cell invasion gene ibeA by deletion, complementation, and protein expression. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1071–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Huang SH, et al. 1995. Escherichia coli invasion of brain microvascular endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo: molecular cloning and characterization of invasion gene ibe10. Infect. Immun. 63:4470–4475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ishidate K, et al. 1986. Isolation of differentiated membrane domains from Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium, including a fraction containing attachment sites between the inner and outer membranes and the murein skeleton of the cell envelope. J. Biol. Chem. 261:428–443 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jung IL, Kim IG. 2003. Transcription of ahpC, katG, and katE genes in Escherichia coli is regulated by polyamines: polyamine-deficient mutant sensitive to H2O2-induced oxidative damage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 301:915–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kanai T, Takahashi K, Inoue H. 2006. Three distinct-type glutathione S-transferases from Escherichia coli important for defense against oxidative stress. J. Biochem. 140:703–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. 2004. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:123–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Korea CG, Badouraly R, Prevost MC, Ghigo JM, Beloin C. 2010. Escherichia coli K-12 possesses multiple cryptic but functional chaperone-usher fimbriae with distinct surface specificities. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1957–1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lamarche MG, et al. 2005. Inactivation of the pst system reduces the virulence of an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli O78 strain. Infect. Immun. 73:4138–4145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee YH, Kim JH, Bang IS, Park YK. 2008. The membrane-bound transcriptional regulator CadC is activated by proteolytic cleavage in response to acid stress. J. Bacteriol. 190:5120–5126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lennox ES. 1955. Transduction of linked genetic characters of the host by bacteriophage P1. Virology 1:190–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lesniak J, Barton WA, Nikolov DB. 2003. Structural and functional features of the Escherichia coli hydroperoxide resistance protein OsmC. Protein Sci. 12:2838–2843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lindqvist A, Membrillo-Hernandez J, Poole RK, Cook GM. 2000. Roles of respiratory oxidases in protecting Escherichia coli K12 from oxidative stress. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 78:23–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lukjancenko O, Wassenaar TM, Ussery DW. 2010. Comparison of 61 sequenced Escherichia coli genomes. Microb. Ecol. 60:708–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marc D, Arné P, Brée A, Dho-Moulin M. 1998. Colonization ability and pathogenic properties of a fim− mutant of an avian strain of Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 149:473–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Moulin-Schouleur M, et al. 2007. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli of avian and human origin: link between phylogenetic relationships and common virulence patterns. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:3366–3376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nossal NG, Heppel LA. 1966. The release of enzymes by osmotic shock from Escherichia coli in exponential phase. J. Biol. Chem. 241:3055–3062 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ochs DL, Toth TE, Pyle RH, Siegel PB. 1988. Cellular defense of the avian respiratory system: effects of Pasteurella multocida on respiratory burst activity of avian respiratory tract phagocytes. Am. J. Vet. Res. 49:2081–2084 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ostergaard H, Henriksen A, Hansen FG, Winther JR. 2001. Shedding light on disulfide bond formation: engineering a redox switch in green fluorescent protein. EMBO J. 20:5853–5862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Park S, You X, Imlay JA. 2005. Substantial DNA damage from submicromolar intracellular hydrogen peroxide detected in Hpx− mutants of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9317–9322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Parreira VR, Gyles CL. 2003. A novel pathogenicity island integrated adjacent to the thrW tRNA gene of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli encodes a vacuolating autotransporter toxin. Infect. Immun. 71:5087–5096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Roche D, et al. 2010. ICEEc2, a new integrative and conjugative element belonging to the pKLC102/PAGI-2 family, identified in Escherichia coli strain BEN374. J. Bacteriol. 192:5026–5036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ron EZ. 2006. Host specificity of septicemic Escherichia coli: human and avian pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:28–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Russo TA, Johnson JR. 2006. Extraintestinal isolates of Escherichia coli: identification and prospects for vaccine development. Expert Rev. Vaccines 5:45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schouler C, Koffmann F, Amory C, Leroy-Setrin S, Moulin-Schouleur M. 2004. Genomic subtraction for the identification of putative new virulence factors of an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain of O2 serogroup. Microbiology 150:2973–2984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Takeshita S, Sato M, Toba M, Masahashi W, Hashimoto-Gotoh T. 1987. High-copy-number and low-copy-number plasmid vectors for lacZ alpha-complementation and chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene 61:63–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tanaka K, Handel K, Loewen PC, Takahashi H. 1997. Identification and analysis of the rpoS-dependent promoter of katE, encoding catalase HPII in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1352:161–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Tenaillon O, Skurnik D, Picard B, Denamur E. 2010. The population genetics of commensal Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8:207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Touchon M, et al. 2009. Organised genome dynamics in the Escherichia coli species results in highly diverse adaptive paths. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000344 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Uchiyama J, et al. 2010. Involvement of sigmaS accumulation in repression of the flhDC operon in acidic phospholipid-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli. Microbiology 156:1650–1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Uzzau S, Figueroa-Bossi N, Rubino S, Bossi L. 2001. Epitope tagging of chromosomal genes in Salmonella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:15264–15269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Vijayakumar SR, Kirchhof MG, Patten CL, Schellhorn HE. 2004. RpoS-regulated genes of Escherichia coli identified by random lacZ fusion mutagenesis. J. Bacteriol. 186:8499–8507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Visick JE, Clarke S. 1997. RpoS- and OxyR-independent induction of HPI catalase at stationary phase in Escherichia coli and identification of rpoS mutations in common laboratory strains. J. Bacteriol. 179:4158–4163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zou Y, He L, Huang SH. 2006. Identification of a surface protein on human brain microvascular endothelial cells as vimentin interacting with Escherichia coli invasion protein IbeA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 351:625–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zou Y, et al. 2007. PSF is an IbeA-binding protein contributing to meningitic Escherichia coli K1 invasion of human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 196:135–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]