Abstract

Adrenomedullin 2 (AM2) or intermedin is a member of the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP)/calcitonin family of peptides and was discovered in 2004. Unlike other members of this family, no unique receptor has yet been identified for it. It is extensively distributed throughout the body. It causes hypotension when given peripherally, but when given into the CNS, it increases blood pressure and causes sympathetic activation. It also increases prolactin release, is anti-diuretic and natriuretic and reduces food intake. Whilst its effects resemble those of AM, it is frequently more potent. Some characterization of AM2 has been done on molecularly defined receptors; the existing data suggest that it preferentially activates the AM2 receptor formed from calcitonin receptor-like receptor and receptor activity modifying protein 3. On this complex, its potency is generally equivalent to that of AM. There is no known receptor-activity where it is more potent than AM. In tissues and in animals it is frequently antagonised by CGRP and AM antagonists; however, situations exist in which an AM2 response is maintained even in the presence of supramaximal concentrations of these antagonists. Thus, there is a partial mismatch between the pharmacology seen in tissues and that on cloned receptors. The only AM2 antagonists are peptide fragments, and these have limited selectivity. It remains unclear as to whether novel AM2 receptors exist or whether the mismatch in pharmacology can be explained by factors such as metabolism.

LINKED ARTICLES

This article is part of a themed section on Secretin Family (Class B) G Protein-Coupled Receptors. To view the other articles in this section visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2012.166.issue-1

Keywords: calcitonin, CGRP, adrenomedullin, intermedin, amylin, calcitonin receptor-like receptor, RAMP, receptor activity-modifying protein, hypotension, prolactin

Introduction

The peptide known either as adrenomedullin 2 (AM2) or intermedin (IMD) was independently discovered by two groups in 2004 (Roh et al., 2004; Takei et al., 2004a). It is most closely related to AM. In fish it is one of a family of five AM-related peptides, but in mammals, there is currently only evidence for widespread expression of AM and AM2; in some mammals (such as ungulates and lower primates but not rodents or humans), the equivalent of fish AM5 is also found (Takei et al., 2008).

AM2/IMD sits within the wider calcitonin (CT) gene-related peptide (CGRP)/CT family of peptides, which also includes amylin. It is expressed in both peripheral tissues and in the CNS; its effects generally resemble those of AM, but it is sometimes more potent and appears to have some unique actions (Taylor and Samson, 2005; Hashimoto et al., 2007). This review considers the pharmacology of AM2/IMD, both on molecularly defined receptors and in native cells and tissues. It considers its specificity for known receptors belonging to the CGRP/CT peptide family and also evaluates the evidence that it may act on other receptors.

Distribution of AM2/IMD

The distribution of AM2/IMD in cells and tissues overlaps with AM. Compared with AM, AM2/IMD is less widely distributed in mammals (Taylor et al., 2005). Table 1 summarizes the distribution of AM2/IMD in organs and tissues of different species. Generally, this peptide is found in the brain, pituitary, heart, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, plasma (Roh et al., 2004; Takei et al., 2004a; Taylor et al. 2005; Takahashi et al., 2006), pancreas, lung, spleen, thymus and ovary (Takei et al., 2004b). Among these tissues, kidney, hypothalamus (Taylor et al., 2005; Takahashi et al., 2006) and stomach (Taylor et al., 2005) have the highest peptide content. AM2/IMD was shown to be co-localized with vasopressin in the paraventricular (Takahashi et al., 2006) and supraoptic nuclei of the human hypothalamus (Takahashi et al., 2011). Under normal conditions, AM2/IMD is not found at a high level in the heart. AM2/IMD mRNA is detected in neonatal cardiomyocytes but is absent (Pan et al., 2005) or sparse in adult myocardia in rat (Zhao et al., 2006) and mouse (Zeng et al., 2009). In the mouse, AM2/IMD is enriched in endothelial cells of coronary arteries and veins (Takei et al., 2004b). However, this does not seem to apply to the adult human heart (Takahashi et al., 2006).

Table 1.

Distribution of AM2/IMD in mammalian tissues

| Organs and tissues | Species | Techniques | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular system | |||

| Heart | Human | RT-PCR | Takahashi et al. (2006) |

| Left ventricles | Human | RIA | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Cardiomyocytes | Human | RIA | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Pericardial adipocytes | Human | RIA | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Vascular endothelial cells of pericardial veins | Human | RIA | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Vascular smooth muscle cells of coronary arteries | Human | ICC | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Myocardial cells | Human | ICC | Takahashi et al. (2006) |

| Heart | Rat | RIA | Taylor et al. (2005) |

| Endothelial cells of coronary vessels | Mouse | RT-PCR | Takei et al. (2004b) |

| CNS | |||

| Brain | Teleost fish | RT-PCR | Ogoshi et al. (2003) |

| Brain | Human | RT-PCR | Takahashi et al. (2006) |

| Brain | Human | RIA, HPLC | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Paraventricular supraoptic nuclei of hypothalamus | Human | ICC | Takahashi et al. (2006) |

| Paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of hypothalamus | Human | ICC | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Hypothalamus | Rat | RIA | Taylor et al. (2005) |

| Brainstem | Rat | RIA | Taylor et al. (2005) |

| Cerebellum | Rat | RIA | Taylor et al. (2005) |

| Endocrine glands | |||

| Anterior and posterior lobes of pituitary | Human | ICC | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Pituitary | Human | RIA | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Pituitary | Human | RT-PCR | Takahashi et al. (2006) |

| Anterior pituitary | |||

| Posterior pituitary | Rat | RIA | Taylor et al. (2005) |

| Pituitary | Rat | Northern blot | |

| Pituitary | Mouse | ICC | Roh et al. (2004) |

| Adrenal medulla | Human | RT-PCR, RIA, ICC | Morimoto et al. (2008) |

| Excretory system | |||

| Kidney | Human | RT-PCR | Takahashi et al. (2006) |

| Kidney | Human | RIA, HPLC | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Renal tubular cells | Human | ICC | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Renal tubular cells | Human | ICC | Takahashi et al. (2006) |

| Renal arterioles | Human | ICC | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Kidney | Rat | RIA | Taylor et al. (2005) |

| Kidney | Mouse | RT-PCR | Takei et al. (2004b) |

| Glomeruli and vasa recta | Mouse | RT-PCR | Takei et al. (2004b) |

| Gastrointestinal system | |||

| Gastrointestinal tract | Human | RT-PCR | Roh et al. (2004) |

| Stomach | Rat | RIA | Taylor et al. (2005) |

| Stomach | Rat | Northern blot | |

| Stomach | Mouse | ICC | Takei et al. (2004b) |

| Submaxillary gland, stomach, pancreas | Mouse | RT-PCR | Takei et al. (2004b) |

| Reproductive system | |||

| Ovary | Mouse | PCR | Takei et al. (2004b) |

| Respiratory system | |||

| Lung | Rat | RIA | Taylor et al. (2005) |

| Pulmonary endothelium | Mouse | ICC, RT-PCR | Pfeil et al. (2009) |

| Others | |||

| Lymphoid tissues | Mouse | RT-PCR | Takei et al. (2004b) |

| Plasma | Human | RIA, HPLC | Morimoto et al. (2007) |

| Plasma | Rat | RIA | Taylor et al. (2005) |

| Skin | Human | RT-PCR | Kindt et al. (2007) |

The sequence of AM2/IMD and its nomenclature

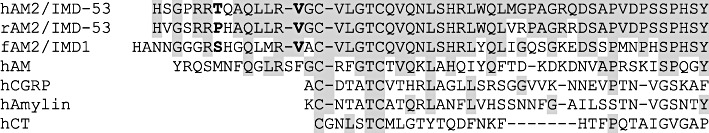

The amino acid sequences of various forms of AM2/IMD are shown in Figure 1. These are produced from a pre-pro hormone by cleavage between arginine residues at positions 93 and 94, to give a 53 amino acid version of AM2/IMD (Yang et al., 2005). There is further potential for processing at the N-terminus to generate 40 and 47 amino acid versions of the peptide (Roh et al., 2004). It is extremely important for researchers to specify which form they use in their studies. At this stage, it is difficult to ascertain which of these is the major peptide. Therefore, terms such as AM1-47 and AM1-40 are not correct if the N-terminally extended 53 amino acid is considered to be an active form of the peptide (Takahashi et al., 2011). Another important nomenclature issue relates to the use of the terms ‘AM2’ or ‘intermedin’. AM2 is based on sound phylogenetic reasoning and allows ready accommodation of other members of the AM family such as AM5; however, ‘intermedin’ remains in common use. Intermedin was the former name for α-melanocyte stimulating hormone. At the 7th International Symposium on the CGRP, Adrenomedullin, Amylin, Intermedin and Calcitonin (August 2010, Queenstown, New Zealand) the participants agreed that both terms should be used in the abstract of any paper; throughout this review, AM2/IMD has been adopted. To differentiate between the forms of AM2/IMD, in this review, AM2/IMD-53, AM2/IMD-47 and AM2/IMD-40 are used.

Figure 1.

The CT family of peptides. Sequences are human (h), rat (r), pufferfish (Fugu rubripes, f). Bold script on the AM2/IMD sequences indicates cleavage sites to produce 47 and 40 amino acid forms of the peptide. Shaded residues show identity compared to human AM2/IMD-53.

Known receptors for the CGRP/CT family of peptides

Given that AM2/IMD is a member of the CGRP/CT-family of peptides, it is logical to assume that it will produce at least some of its effects on their receptors. These are produced by the interaction of two GPCRs, the CT receptor and the calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CLR), with three receptor activity-modifying proteins (RAMPs). CLR with RAMP1 gives the CGRP receptor; with RAMP2 or RAMP3, it gives the AM1 or AM2 receptors. The nomenclature of the AM2 receptor does not relate to the ability of the peptide AM2/IMD to activate this receptor. This is a potential source of confusion in the field. The CT receptor by itself is the receptor for CT; with the three RAMPs, it produces three amylin receptors: AMY1, AMY2 and AMY3. The human CT receptor exists as two splice variants, distinguished as CT(a) and CT(b) receptors; in turn, this means that each amylin receptor exists as (a) or (b) forms (Poyner et al., 2002). Specific information relating to the ability of AM2/IMD to act upon CT peptide family receptors is discussed later in this review.

AM2/IMD antagonists

Very little work has been done to investigate the structure–activity relationship of AM2/IMD. It would be expected that it should follow the same themes as have been established for other members of this family, with agonist activation requiring the disulphide-bonded ring and subsequent truncation fragments acting as an antagonists, at least on stimulation of cAMP. AM2/IMD-4717–47 is an antagonist (Roh et al., 2004; Chauhan et al., 2007), although in some systems, its inhibition appears to be non-competitive (Kandilci et al., 2008), and it does not block all actions of AM2/IMD in vivo (White and Samson, 2007).

A number of novel antagonists have been produced by taking residues 22–30, 31–35 and 39–47 from AM2/IMD-47 and using them to replace the equivalent sections of AM22–52, the AM antagonist (Robinson et al., 2009). The insertion of residues 23–30 unexpectedly gave a peptide that was a higher affinity antagonist than the parent compound at AM1, AM2 and CGRP receptors. Residues 31–35 gave an antagonist that resembled the actions of AM22–52 on AM1 and CGRP receptors but which had a higher affinity on AM2 receptors. Insertion of 39–47 gave an antagonist that resembled AM22-52 at AM2 and CGRP receptors but with a slightly lower affinity at AM1 receptors. The ability of residues 22–30 to confer high affinity binding at CGRP receptors is interesting. In evolutionary terms, AM2/IMD is most closely related to AM with twice the number of identical residues compared to CGRP (Figure 1). However, in spite of this, at some receptors, it follows more closely CGRP potency than that of AM. It is possible thatresidues 22–30 are partly responsible for the CGRP-like properties of AM2/IMD. Equally, residues 31–35 may help give AM2/IMD its relatively high potency at AM2 receptors, although the mechanistic basis for both of these observations remains obscure.

Whilst the studies with chimeric peptides may ultimately lead to better AM2/IMD antagonists, currently, AM2/IMD-4717–47 is the only widely available compound, and it suffers from the problems of having at best a moderate affinity and limited selectivity. In this, it is not alone as none of the peptide antagonists at CGRP and AM receptors show particularly good discrimination between all of the receptors (Table 2). AM2/IMD-4717–47 has not been tested against individual receptor subtypes and so its selectivity is unknown. The lack of a good AM2/IMD antagonist is a major barrier to studying the physiological role of this peptide. Furthermore, identification of the cognate receptor for AM2/IMD is needed to develop a specific antagonist.

Table 2.

Affinities of antagonists on CLR/RAMP receptors

| Antagonist | CGRP | AM1 | AM2 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGRP8–37 | 9–10 | 6–7 | 6–7 | Poyner et al. (2002) |

| AM22–52 | ∼6 | 7–8 | 7–8 | |

| AM217–47 | ∼6 | ∼6 | ∼6 | Chauhan et al. (2007) |

For CGRP8–37 and AM22–52, pKi estimates are shown. For AM217–47, the value is the pA2 estimated from inhibition of AM2/IMD-mediated relaxation of the rat mesenteric artery; the receptor responsible for this effect is unknown.

The actions of AM2/IMD in mammals

The effective molecular forms of AM2/IMD

Several forms of AM2/IMD have been tested in animals. Roh et al. (2004) observed that i.p. injection of AM2/IMD-47 is more potent than AM2/IMD-40 in increasing the heart rate. AM2/IMD-53 was found to elevate blood pressure and heart rate further than AM2/IMD-47 following an i.c.v. injection. On the other hand, AM2/IMD-47 produces more prominent hypotension than AM2/IMD-53 after i.v. injection (Ren et al., 2006). Nevertheless, both of these peptides have been used to examine the pharmacological effects of AM2/IMD.

Cardiovascular effects of AM2/IMD

Peripheral administration of AM2/IMD decreases aortic resistance, improves heart performance and elevates coronary perfusion flow under physiological conditions (Pan et al., 2005; Dong et al., 2006). This peptide also strengthens the contractility of the left ventricle and increases the coronary perfusion flow and heart beats following ischemia/reperfusion injury (Yang et al., 2005). AM2/IMD has been shown to reduce the myocardial infarction size (Song et al., 2009; Zeng et al., 2009), hypertrophy in left ventricular cardiomyocytes and the production of cardiac fibrosis (Yang et al., 2009) under pathological conditions. On the other hand, AM2/IMD decreases arterial pressure (Chang et al., 2004; Roh et al., 2004; Takei et al., 2004b; Pan et al., 2005; Fujisawa et al., 2006; Abdelrahman and Pang, 2007). The hypotensive effect of AM2/IMD is attributed to its vasodilatory action as it does not alter mean circulatory filling pressure (Abdelrahman and Pang, 2006). This peptide essentially dilates the blood vessels in the renal (Fujisawa et al., 2004; 2006; Takei et al., 2004b), pulmonary (Burak Kandilci et al., 2006) and abdominal arteries (Jolly et al., 2009), improving blood flow in the visceral organs. However, central administration of AM2/IMD increases sympathetic activity (Hashimoto et al., 2007; Takahashi et al., 2011) and elevates blood pressure (Ren et al., 2006; Hashimoto et al., 2007; Takahashi et al., 2011). These results suggest that AM2/IMD is potentially an important regulatory factor in cardiovascular activity via central and peripheral actions. Furthermore, the level of AM2/IMD mRNA and protein is enhanced in the myocardium (Pan et al., 2005; Zeng et al., 2009), aorta and plasma (Zeng et al., 2009) in cardiac hypertrophy or heart infarction. It is an interesting possibility that the increased AM2/IMD may stimulate sensitive sympathetic visceral afferents to evoke reflex excitation of the cardiovascular system inducing angina and the referred pain.

Other effects of AM2/IMD

AM2/IMD may play a role in the regulation of prolactin release during reproduction in females. Both central (Taylor and Samson, 2005) and peripheral (Lin Chang et al., 2005) injections of AM2/IMD have been shown to increase blood prolactin levels. This peptide inhibits growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH)-stimulated growth hormone release from anterior pituitary (Taylor et al., 2006) and elevates the levels of oxytocin (Hashimoto et al., 2005; 2007; Taylor and Samson, 2005) and vasopressin in plasma (Taylor and Samson, 2005). In addition, AM2/IMD was found to induce anti-diuresis and anti-natriuresis (Takei et al., 2004b), decrease food (Roh et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2005) and water (Taylor et al., 2005) intake and inhibit gastric emptying activity (Roh et al., 2004). These studies suggest that AM2/IMD produces multiple actions and may be involved in controlling the homeostasis of growth and metabolism.

Comparison of the effects of AM2/IMD and AM

Many studies have reported that AM2/IMD is more potent than AM in both periphery and brain. Furthermore, AM2/IMD and AM may not always display identical effects in some physiological conditions. For example, AM2/IMD inhibits GHRH-stimulated release of growth hormone from rat anterior pituitary cell cultures, whereas AM does not (Taylor et al., 2006). Down-regulation of AM2/IMD expression was maintained in the remnant kidney of 5/6 nephrectomized rats (a model of chronic renal impairment), but AM expression was elevated in the later phase in these kidney tissues, suggesting that AM2/IMD has a distinct pathophysiological role.

The pharmacology of AM2/IMD on molecularly defined receptors

Introduction

AM2/IMD has been examined on CGRP, AM and AMY receptors, either on transfected cells (Chang et al., 2004; Roh et al., 2004; Takei et al., 2004a; Hay et al., 2005; Qi et al., 2008; 2011; Wunder et al., 2008) or on CGRP receptors endogenously expressed in human SK-N-MC and rat L6 cells (Chang et al., 2004; Roh et al., 2004). The results of these studies are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

pEC50 values or estimates for AM2/IMD and other peptides at CGRP, CT, AM and amylin (AMY) receptors

| Cell type | Ligand | CGRP receptor | AM1 receptor | AM2 receptor | CT receptor | AMY1(a) receptor | AMY2 receptor | AMY3(a) receptor | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cos 7 | AM2/IMD-47 | 8.24 ± 0.12 | 8.96 ± 0.17 | Qi et al. (2011) | |||||

| AM | 8.04 ± 0.15 | 9.76 ± 0.18 | |||||||

| CGRP | 9.84 ± 0.12 | 6.77 ± 0.17 | |||||||

| Cos 7 | AM2/IMD-40 | 8.71 ± 0.13 | 8.10 ± 0.04 | 8.69 ± 0.13 | 6.53 ± 0.45 | 8.07 ± 0.19 | 6.25 ± 0.26 | 7.12 ± 0.19 | Hay et al. (2005) |

| hAM | 6.73 ± 0.45 | 6.48 ± 0.28 | 6.89 ± 0.51 | ||||||

| hCGRP | 9.47 ± 0.19 | 6.39 ± 0.10 | 6.87 ± 0.13 | 6.80 ± 0.05 | 8.70 ± 0.17 | 7.24 ± 0.19 | 7.60 ± 0.17 | ||

| hCT | 8.99 ± 0.10 | 8.93 ± 0.09 | 8.02 ± 6.22 | ||||||

| Cos 7 | AM2/IMD-47 | 9.07 ± 0.07 | 10.1 ± 0.02 | Qi et al. (2008) | |||||

| AM | 8.27 ± 0.11 | 9.92 ± 0.06 | |||||||

| CGRP | 10.10 ± 0.11 | 7.36 ± 0.06 | |||||||

| HEK-293T | AM2/IMD-40 | 7.5 ? | 7.7 ? | 9.2 | Roh et al. (2004) | ||||

| AM | 8 | 8.8 | 8 | ||||||

| CGRP | 9.5 | 7.7? | 8 | ||||||

| L6 | AM2/IMD-40 | 8.2? | |||||||

| AM2/IMD-47 | 7.6? | ||||||||

| CGRP | 9.2 | ||||||||

| AM | 8 | ||||||||

| SK-N-MC | AM2/IMD-40 | 8.6 | |||||||

| AM2/IMD-47 | 7 ? | ||||||||

| CGRP | 9.3 | ||||||||

| AM | 7.7 | ||||||||

| Cos 7 | AM2/IMD | 7.9 | 7.5 | 8.9 | 6? | 8 | 6? | 7.2 | Takei et al. (2004) |

| AM | 8 | 9.9 | 9.7 | ||||||

| CGRP | 9.8 | 7.5? | 7.5 | ||||||

| hCT | 9 | 9 | 9.2 | 7.8 | |||||

| HEK-293T | AM2/IMD | 8 | 7.5 | 9 | Chang et al. (2004) | ||||

| CHO | AM2/IMD | 7.74 ± 0.09 | 8.27 ± 0.06- | Wunder et al. (2008) | |||||

| AM | 8.44 ± 0.03 | 9.45 ± 0.08 | |||||||

| CGRP | 9.50 ± 0.12 | 6.87 ± 0.08 |

Where the concentration–response curves are incomplete, a question mark has been placed next to the pEC50. *Partial agonist. Values without error bars have been estimated from published concentration–response curves.

An important issue to consider is whether the form of AM2/IMD makes any difference to its pharmacology because some differences in the biological activities of AM2/IMD-47 and AM2/IMD-40 have been reported, although their overall behaviour is broadly similar (Pan et al., 2005). In a direct comparison of AM2/IMD-47 and AM2/IMD-40 on the CGRP receptor of rat L6 cells, AM2/IMD-40 was more potent, although the difference was less clear on the CGRP receptor in human SK-N-MC cells. Furthermore, in binding experiments carried out on the two cell lines, there was little difference in their Ki values (Roh et al., 2004), although as noted below, the interpretation of these is not simple. The two forms have also been examined on Cos 7 cells transiently transfected with human CGRP and AM2 receptors, although not in parallel studies (Hay et al., 2005; Qi et al., 2008). There was little difference between their potencies, but given the variation in potency seen in transient transfections, little can be drawn from this. However, if there were differences in the potency between the two forms, this should have been reflected in their relative potency compared with CGRP. On both receptors, the potency relative to CGRP was very similar. At present, it seems that there is not a compelling case to assume that there are meaningful differences in the potencies of the two AM2/IMD forms at human receptors, at least when measuring cAMP, although further work is needed.

The receptor selectivity of AM2/IMD in functional studies

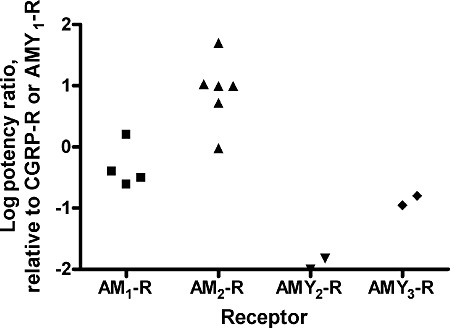

The data in Table 3 suggest that AM2/IMD shows selectivity between different receptor types. This has been re-plotted in Figure 2, to compare the potency of AM2/IMD on the AM1 and AM2 receptors relative to that for the CGRP receptor, or the AMY2 and AMY3(a) receptors relative to that for the AMY1(a) receptor. For the purposes of this table, no distinction has been made between the forms of AM2/IMD. It appears that AM2/IMD shows selectivity for the AM2 receptor, being around an order of magnitude more potent at that receptor than either the CGRP or AM1 receptors. Nevertheless, it is important to point out that due to the lack of quantification in some of the published studies, we can only estimate potencies in some cases. There are less data for the CT receptor-based receptors, but what there is suggests a potency order of AMY1(a)≥ AMY3(a) >> AMY2= CT(a). For the AMY2 receptor, there are only two studies that were performed in Cos 7 cells, where this receptor usually forms only poorly (Christopoulos et al., 1999; Hay et al., 2005), and there is insufficient evidence in the report to assess whether there was any formation of this entity or whether the AM2/IMD was simply acting on a CT receptor (Takei et al., 2004a).

Figure 2.

Potency ratios of AM2/IMD at CLR and CTR-based receptors. Log potency ratios were calculated from the data in Table 1. Points show the results of individual studies as indicated in Table 1. For the AM1 and AM2 receptors, the EC50 of AM2/IMD was compared with that at the CGRP receptor. For the AMY2 and AMY3 receptors, the EC50 of AM2/IMD was compared with that at the AMY1 receptor. No distinction has been made between AM2/IMD-40 and AM2/IMD-47; data from rat L6 have also been included with the human forms of the CGRP receptor.

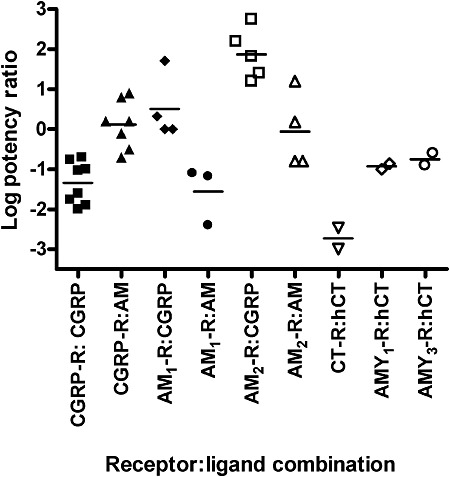

The relative potency of AM2/IMD compared to CGRP and AM depends on the receptor type (Table 2, Figure 3). At the CGRP receptor, AM2/IMD is at least an order of magnitude less potent than CGRP itself but is roughly equipotent with AM. At the AM1 receptor, it is typically a little less potent than CGRP but is two or more orders of magnitude less potent than AM. At the AM2 receptor, it is between 10- and 100-fold more potent than CGRP and is comparable with AM itself. There is again less data for amylin and CT receptors. Along with AM and CGRP, AM2/IMD has a very low potency at the CT receptor compared with CT itself. At the AMY1(a) and AMY3(a) receptors, it is around an order of magnitude less potent than CT. Taking the data as a whole, arguably the most interesting observation is that at the AM2 receptor, the potency of AM2/IMD approaches the potency of AM itself, the presumed endogenous ligand. It seems possible that this receptor may function physiologically as an AM2/IMD receptor. This is supported by recent data in rat and mouse AM2 receptors, where AM and AM2/IMD-47 are equipotent (DLH, unpubl. obs.).

Figure 3.

Agonist potency ratios for AM2/IMD on CGRP, AM and amylin receptors. Log potency ratios are defined as log [EC50 AM2/IMD ÷ EC50 agonist] and were calculated from the data in Table 1. Points show the results of individual studies as indicated in Table 1. For the CGRP and AM receptors, potency ratios have been calculated for CGRP and AM; for the CT and amylin receptors, the potency ratio for human calcitonin has been calculated. No distinction has been made between AM2/IMD-40 and AM2/IMD-47; data from rat L6 have also been included for the CGRP receptor.

The receptor selectivity of AM2/IMD in radioligand binding studies

Agonist potency ratios are an unsatisfactory way of investigating affinity of ligands at receptors as they reflect both binding and efficacy; the latter is very system dependent. Unfortunately, very few radioligand binding studies have been carried out with AM2/IMD. Nevertheless, data on AMY1(a) and AMY(3a) receptors confirm that the potency ratios seen at stimulating cAMP production are in line with affinities (Table 4) (Hay et al., 2005). For CGRP receptors, the situation is less clear cut. AM2/IMD has been investigated on rat L6 and human SK-N-MC cells using iodinated CGRP as the radioligand (Roh et al., 2004). This should measure binding just to CGRP receptors. However, in neither case does the binding profile of the receptors match what would be expected for a CGRP receptor, as there is little difference between the IC50 values for CGRP or AM. On L6 cells, both AM2/IMD-47 and AM2/IMD-40 have around a fivefold lower affinity than AM or CGRP; on SK-N-MC cells the differences appears less. Given the poor discrimination between CGRP and AM, it is difficult to know how to interpret these results.

Table 4.

Affinities of AM2/IMD and related peptides at AMY receptors

| Ligand | hAMY1(a) receptor | hAMY3(a) receptor |

|---|---|---|

| hCT | 6 | ≤6 |

| rAMY | 8.76 ± 0.06 | 8.60 ± 0.09 |

| hαCGRP | 8.00 ± 0.08 | 6.97 ± 0.55 |

| hAM | <6 | <6 |

| AM2/IMD-40 | 6.93 ± 0.69 | 6.21 ± 0.26 |

Receptors were expressed in Cos 7 values. The table shows pIC50 values for inhibition of 125I-rAMY binding on whole cells. The values are mean ± SEM for three independent experiments (Hay et al., 2005).

The pharmacology of AM2/IMD at fish receptors

One study has examined the pharmacology of AM2/IMD at puffer fish, Takifugu obscurus, receptors (Nag et al., 2006). This expresses orthologues of mammalian RAMP1, RAMP2 and RAMP3 (RAMP2 exists in two splice forms) as well as two extra RAMPs. This species also has three CLR orthologues. Fugu AM2/IMD showed almost 100-fold selectivity for CLR1/RAMP3 compared with the other RAMPs, although its potency at this receptor was little different from the AM1 or AM5 peptides. It was also a potent agonist at the CLR3/RAMP3 receptor. Here it was more potent than the AM5 peptide; there was little difference in potency compared to the AM1 peptide, but it may have had greater efficacy. Given the evidence that AM2/IMD appears to preferentially activate CLR/RAMP3 (the AM2 receptor) in humans, it is interesting this RAMP is also involved in its recognition in fish.

Conclusions

Overall, a number of themes are apparent from considering the pharmacology of AM2/IMD on defined receptors. There is clearly a need for further work, to properly define the specificity of these agents. In particular, there is a need for radioligand binding studies to allow pKi values to be measured. That said, the peptide does seem to show an interesting pharmacological profile and appears to have good activity at the AM2 receptor but with lower potency at the AM1 receptor. There is no known receptor where it is more potent than the likely endogenous ligand. The role of the N-terminal extensions of AM2/IMD is unclear. Whilst there is a solid body of work to indicate that these can influence the potency of the peptides, it is uncertain as to whether they do this by actions at the level of the receptors or whether they influence factors such as susceptibility to peptidases. This is particularly the case when considering the actions of these peptides in in vivo studies.

The receptor pharmacology of AM2/IMD in native cells and tissues

The data reviewed above clearly show that in recombinant systems, AM2/IMD can activate CGRP, AM1 and AM2 receptors. On moving into endogenous cells and tissues, it is important to determine which of these three receptors chiefly mediates the effects of the peptide, whether exogenously applied or released naturally and also to ascertain if there are any other receptors for these peptides. The data regarding receptors mediating AM2/IMD-induced pharmacological responses in native tissues and cells are variable.

The CGRP receptor antagonist CGRP8-37 (Chiba et al., 1989) and AM receptor antagonist AM22–52 (Hay et al., 2003) have been used to determine if AM2/IMD-induced responses are independent of CGRP or AM receptors (Table 5). Roh et al. (2004) reported that AM2/IMD-induced hypotension was blocked by CGRP8-37. Other studies show that AM22–52 or/and CGRP8–37 was equally effective in attenuating the effects induced by AM2/IMD and AM. These include peripheral vasodilatation in the renal and mesenteric arteries (Jolly et al., 2009), central increase in blood pressure and heart rate (Ren et al., 2006) and barrier-protective effect of AM2/IMD on pulmonary endothelial cells (Pfeil et al., 2009). These results suggest that CGRP or AM receptors mediate AM2/IMD-induced responses.

Table 5.

Studies of pharmacology of AM2/IMD in vivo and in animal tissues

| Antagonism | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AM2/IMD-induced response | Peptide | Species | CGRP8–37 | AM22–52 | AM217–47 | References |

| Reduction of arterial pressure | AM2/IMD-47, i.p. | Rat | + | + | Roh et al. (2004) | |

| AM2/IMD-47, i.p. | SHR | + | − | |||

| Increase of arterial pressure | AM2/IMD-47, i.c.v. | Rat | Partially | Taylor et al. (2005) | ||

| Increase of heart rate | Partially | |||||

| Reduction of arterial pressure | AM2/IMD-53, i.c.v. | Rat | + | + | Ren et al. (2006) | |

| Vasodilation of pulmonary artery | AM2/IMD-47, i.a. | Rat | + | Burak Kandilci et al. (2006) | ||

| Increase of heart rate | AM2/IMD-47, i.c.v. | Rat | − | |||

| Increase in plasma oxytocin | Partially | Partially | Hashimoto et al. (2007) | |||

| c-fos gene expression in the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei | Partially | Partially | ||||

| cAMP generation in spinal cord | AM2/IMD-47, p.f. | Rat | Partially | Partially | Owji et al. (2008) | |

| Increase of heart rate | AM2/IMD-53, i.v. | Rat | − | Jolly et al. (2009) | ||

| Reduction of arterial pressure | − | |||||

| Vasodilatation | ||||||

| Abdominal aorta | − | |||||

| Renal mesenteric artery | + | |||||

| cAMP generation in myocardium and aorta | AM2/IMD-53, p.f. | SHR | − | − | Zeng et al. (2009) | |

| Reduction of permeability of lung blood microvascular endothelial cells | AM2/IMD-47, p.f. | Human | + | Pfeil et al. (2009) | ||

p.f., perfusion; SHR, spontaneous hypertensive rat. +, antagonism; −, no antagonism; partially, partially antagonism; blank, not tested.

However, other studies have demonstrated that AM2/IMD may activate a distinct receptor besides the CGRP and AM receptors in native cells and tissues. Our (YH, RQ) laboratory characterized pharmacological response to AM2/IMD using dispersed rat embryonic spinal cultured cells. We observed that AM2/IMD-47 competed for specific [125I]-AM binding in a biphasic manner with pIC50s of 9.03 ± 0.22 and 6.45 ± 0.24 respectively. The fraction of high affinity site was 41 ± 5.0% of the total sites. However, AM followed a one component competition model (pIC50= 9.49 ± 0.17) under the same experimental conditions. These findings suggest that [125I]-AM binds to two different classes of sites or two affinity states of a single entity distinguishable by AM2/IMD-47 but not unlabelled AM. AM2/IMD-47 also demonstrated high affinity for specific [125I]-CGRP binding with a pIC50 (9.73 ± 0.06) close to rat αCGRP (9.99 ± 0.16), indicating that AM2/IMD-47 displays similar affinity for specific [125I]-CGRP binding to CGRP itself (Owji et al., 2008). These results suggest that AM2/IMD can recognize CGRP as well as AM receptors. Our observations are consistent with cell line data. However, we have further demonstrated that the AM2/IMD-47-induced increase in cAMP production in rat spinal cord cells is only partially antagonised by BIBN4096BS (non-peptide CGRP antagonist), hAM22–52 and CGRP8–37 individually. Even a combination of BIBN4096BS, hAM22–52 and the amylin receptor antagonist AC187 (Owji et al., 2008) did not fully inhibit the response, indicating that AM2/IMD could act at a distinct receptor besides CGRP, AM and AMY receptors. These results are supported by a few in vivo studies. It has been shown that AM2/IMD-induced activation of c-fos gene in the supraoptic and the paraventricular nuclei of hypothalamus and increased plasma oxytocin (Hashimoto et al., 2007) and cAMP generation in the myocardium and aorta (Zeng et al., 2009) can only be partially blocked by CGRP8–37 and AM22–52. On the other hand, the antagonists tested have only low affinity at rat AM receptors (Hay et al., 2002; 2003). Therefore, it is also possible that AM receptors make some contribution to the responses. Evidently, more work is needed to study the receptors mediating the actions of AM2/IMD.

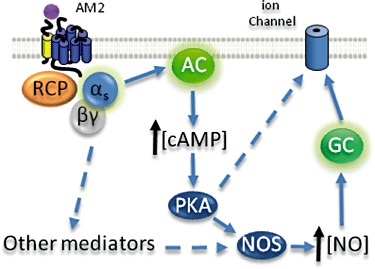

Signalling pathways

CLR belongs to the super-family of seven transmembrane GPCRs (Mittra and Bourreau, 2006). It undergoes conformational changes resulting in coupling to Gs, activation of adenylate cyclase and accumulation of intracellular cAMP when activated by an agonist (Shimekake et al., 1995). If AM2/IMD acts through CLR, it is also logical to assume that it will activate these signalling pathways. The pharmacological effects of AM2/IMD are believed to be attributed to the activation of cAMP/protein kinase A signalling pathway, but other pathways may also play a role (Figure 4). Perfusion with AM2/IMD in the heart increases cAMP content in the myocardium or aorta (Pan et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2005; Zeng et al., 2009), and the protein kinase A inhibitor H-89 abolishes AM2/IMD-induced inotropic effect (Dong et al., 2006). It has also been demonstrated that the activation of protein kinase C (Dong et al., 2006) and Akt/Glycogen synthase kinase-3β signalling pathways (Song et al., 2009) contributes to the cardiovascular action of AM2/IMD. In addition, the NO signalling pathway mediates some AM2/IMD-induced effects. This peptide was shown to increase NO content and NOS activity in isolated rat aortas (Yang et al., 2006). Treatment with the NOS inhibitor l-NAME reduces AM2/IMD-induced renal vasodilator response (Jolly et al., 2009). Where it has been examined, AM2/IMD produces vasodilation in an endothelial-dependent manner, by production of NO, activation of guanylate cyclase and opening of calcium-dependent large-conductance K+ channels (Kandilci et al., 2008) (Figure 4). However, since both AM and CGRP can also produce endothelial-independent vasodilation in the appropriate vascular beds, it is to be anticipated that AM2/IMD will also act in this way.

Figure 4.

Possible signalling pathways activated by AM2/IMD in vascular and endothelial tissue (Kandilci et al., 2008; Grossini et al., 2008). Presumably via CLR, AM2/IMD activates Gαs leading to modulation of ion channel activity via protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent or independent mechanisms. Broken arrows represent pathways that are incompletely understood. Note that for the purposes of this diagram, additional components of some pathways are not shown. AC, adenylate cyclase, GC, guanylate cyclase, RCP, receptor component protein.

Conclusion: the nature of the receptors for AM2/IMD

The fact that AM2/IMD displays overlapping distribution and shares certain similarities with AM implies that it has similar bioactivities. In the absence of selective antagonists, most studies have relied on addition of exogenous AM2/IMD to explore its potential role; this approach has obvious limitations. The physiological relevance of AM2/IMD and in particular the role it may play distinct from that of AM warrants further studies but these are likely to need additional pharmacological tools.

An important issue for ongoing AM2/IMD studies is that its receptors are not yet clearly identified. There is no doubt that AM2/IMD can act pharmacologically through the existing CGRP and AM receptors as well as AMY1 and AMY3 receptors. Of these known receptors, it seems to have its highest affinity at the AM2 receptor where some studies have suggested it may be equipotent with AM. This is worth considering as a candidate for a receptor through which AM2/IMD exerts its physiological effects, but further work is needed to investigate this.

There are also suggestions that AM2/IMD might activate receptors that are distinct from the CLR and CTR complexes, or are modified by additional accessory proteins. There are examples in intact tissues and in vivo where AM2/IMD appears more potent than AM or CGRP, a situation that cannot be easily reconciled with the profile of these peptides on cloned receptors. Here considerations such as the relative metabolic stability of AM2/IMD compared with AM and CGRP may influence potency, although this has been little explored. Some effects also are resistant to a combination of CGRP, AMY and AM receptor antagonists. No work has been done to explore whether AM2/IMD shows a different pattern of coupling to second messenger pathways compared with CGRP, AM or AMY; if this happens, it will further complicate the analysis of its actions. Therefore, further research is needed to identify the receptors that mediate the actions of AM2/IMD.

Acknowledgments

RQ's laboratory is supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Glossary

- AC187

acetyl-(Asn30,Tyr32)-calcitonin8-32

- AM

adrenomedullin

- BIBN4096BS 1-piperidinecarboxamide

N-[2-[[5-amino-1-[[4-(4-pyridinyl)-1-piperazinyl]carbonyl]pentyl]amino]-1-[(3,5-dibromo-4-hydroxyphenyl)methyl]-2-oxoethyl]-4-(1,4-dihydro-2-oxo-3(2H)-quinazolinyl)-, [R-(R*,S*)]

- CGRP

calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CLR

calcitonin receptor-like receptor

- CT

calcitonin

- ICC

immunocytochemistry

- IMD

intermedin

- RAMP

receptor-activity modifying protein

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase-PCR

Conflicts of interest

None to declare.

References

- Abdelrahman AM, Pang CC. Effect of intermedin/adrenomedullin-2 on venous tone in conscious rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2006;373:376–380. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0076-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelrahman AM, Pang CC. Vasodilator mechanism of intermedin/adrenomedullin-2 in anesthetized rats. Proc West Pharmacol Soc. 2007;50:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burak Kandilci H, Gumusel B, Wasserman A, Witriol N, Lippton H. Intermedin/adrenomedullin-2 dilates the rat pulmonary vascular bed: dependence on CGRP receptors and nitric oxide release. Peptides. 2006;27:1390–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CL, Roh J, Hsu SY. Intermedin, a novel calcitonin family peptide that exists in teleosts as well as in mammals: a comparison with other calcitonin/intermedin family peptides in vertebrates. Peptides. 2004;25:1633–1642. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan M, Ross GR, Yallampalli U, Yallampalli C. Adrenomedullin-2, a novel calcitonin/calcitonin-gene-related peptide family peptide, relaxes rat mesenteric artery: influence of pregnancy. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1727–1735. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba T, Yamaguchi A, Yamatani T, Nakamura A, Morishita T, Inui T, et al. Calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist human CGRP-(8-37) Am J Physiol. 1989;256:E331–E335. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1989.256.2.E331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos G, Perry KJ, Morfis M, Tilakaratne N, Gao Y, Fraser NJ, et al. Multiple amylin receptors arise from receptor activity-modifying protein interaction with the calcitonin receptor gene product. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:235–242. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.1.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong F, Taylor MM, Samson WK, Ren J. Intermedin (adrenomedullin-2) enhances cardiac contractile function via a protein kinase C- and protein kinase A-dependent pathway in murine ventricular myocytes. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:778–784. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01631.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa Y, Nagai Y, Miyatake A, Takei Y, Miura K, Shoukouji T, et al. Renal effects of a new member of adrenomedullin family, adrenomedullin2, in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;497:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa Y, Nagai Y, Miyatake A, Miura K, Shokoji T, Nishiyama A, et al. Roles of adrenomedullin 2 in regulating the cardiovascular and sympathetic nervous systems in conscious rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1120–H1127. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00461.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossini E, Molinari C, Mary DA, Uberti F, Caimmi PP, Vacca G. Intracoronary intermedin 1-47 augments cardiac perfusion and function in anesthetized pigs: role of calcitonin receptors and beta-adrenoreceptor-mediated nitric oxide release. J Appl Physiol. 2008;107:1037–1050. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00569.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Hyodo S, Kawasaki M, Mera T, Chen L, Soya A, et al. Centrally administered adrenomedullin 2 activates hypothalamic oxytocin-secreting neurons, causing elevated plasma oxytocin level in rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E753–E761. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00042.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H, Hyodo S, Kawasaki M, Shibata M, Saito T, Suzuki H, et al. Adrenomedullin 2 (AM2)/intermedin is a more potent activator of hypothalamic oxytocin-secreting neurons than AM possibly through an unidentified receptor in rats. Peptides. 2007;28:1104–1112. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DL, Howitt SG, Conner AC, Doods H, Schindler M, Poyner DR. A comparison of the actions of BIBN4096BS and CGRP(8-37) on CGRP and adrenomedullin receptors expressed on SK-N-MC, L6, Col 29 and Rat 2 cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;137:80–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DL, Howitt SG, Conner AC, Schindler M, Smith DM, Poyner DR. CL/RAMP2 and CL/RAMP3 produce pharmacologically distinct adrenomedullin receptors: a comparison of effects of adrenomedullin22-52, CGRP8-37 and BIBN4096BS. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;140:477–486. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DL, Christopoulos G, Christopoulos A, Poyner DR, Sexton PM. Pharmacological discrimination of calcitonin receptor: receptor activity-modifying protein complexes. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:1655–1665. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.008615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly L, March JE, Kemp PA, Bennett T, Gardiner SM. Mechanisms involved in the regional haemodynamic effects of intermedin (adrenomedullin 2) compared with adrenomedullin in conscious rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:1502–1513. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00306.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandilci HB, Gumusel B, Lippton H. Intermedin/adrenomedullin-2 (IMD/AM2) relaxes rat main pulmonary arterial rings via cGMP-dependent pathway: role of nitric oxide and large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels (BK(Ca) Peptides. 2008;29:1321–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindt F, Wiegand S, Loser C, Nilles M, Niemeier V, Hsu SY, et al. Intermedin: a skin peptide that is downregulated in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:605–613. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Chang C, Roh J, Park JI, Klein C, Cushman N, Haberberger RV, et al. Intermedin functions as a pituitary paracrine factor regulating prolactin release. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:2824–2838. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittra S, Bourreau JP. Gs and Gi coupling of adrenomedullin in adult rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H1842–H1847. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00388.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto R, Satoh F, Murakami O, Totsune K, Suzuki T, Sasano H, et al. Expression of adrenomedullin2/intermedin in human brain, heart, and kidney. Peptides. 2007;28:1095–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto R, Satoh F, Murakami O, Hirose T, Totsune K, Imai Y, et al. Expression of adrenomedullin 2/intermedin in human adrenal tumors and attached non-neoplastic adrenal tissues. J Endocrinol. 2008;198:175–183. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag K, Kato A, Nakada T, Hoshijima K, Mistry AC, Takei Y, et al. Molecular and functional characterization of adrenomedullin receptors in pufferfish. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R467–R478. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00507.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogoshi M, Inoue K, Takei Y. Identification of a novel adrenomedullin gene family in teleost fish. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311:1072–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owji AA, Chabot JG, Dumont Y, Quirion R. Adrenomedullin-2/intermedin induces cAMP accumulation in dissociated rat spinal cord cells: evidence for the existence of a distinct class of sites of action. J Mol Neurosci. 2008;35:355–361. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan CS, Yang JH, Cai DY, Zhao J, Gerns H, Yang J, et al. Cardiovascular effects of newly discovered peptide intermedin/ adrenomedullin 2. Peptides. 2005;26:1640–1646. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeil U, Aslam M, Paddenberg R, Quanz K, Chang CL, Park JI, et al. Intermedin/adrenomedullin-2 is a hypoxia-induced endothelial peptide that stabilizes pulmonary microvascular permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L837–L845. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90608.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poyner DR, Sexton PM, Marshall I, Smith DM, Quirion R, Born W, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXXII. The mammalian calcitonin gene-related peptides, adrenomedullin, amylin, and calcitonin receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:233–246. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi T, Christopoulos G, Bailey RJ, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM, Hay DL. Identification of N-terminal receptor activity-modifying protein residues important for calcitonin gene-related peptide, adrenomedullin, and amylin receptor function. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1059–1071. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.047142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi T, Ly K, Poyner DR, Christopoulos G, Sexton PM, Hay DL. Structure-function analysis of amino acid 74 of human RAMP1 and RAMP3 and its role in peptide interactions with adrenomedullin and calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors. Peptides. 2011;32:1060–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren YS, Yang JH, Zhang J, Pan CS, Yang J, Zhao J, et al. Intermedin 1-53 in central nervous system elevates arterial blood pressure in rats. Peptides. 2006;27:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson SD, Aitken JF, Bailey RJ, Poyner DR, Hay DL. Novel peptide antagonists of adrenomedullin and calcitonin gene-related peptide receptors; identification, pharmacological characterization and interactions with position 74 in RAMP1/3. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:513–521. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.156448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh J, Chang CL, Bhalla A, Klein C, Hsu SY. Intermedin is a calcitonin/calcitonin gene-related peptide family peptide acting through the calcitonin receptor-like receptor/receptor activitymodifying protein receptor complexes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7264–7274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimekake Y, Nagata K, Ohta S, Kambayashi Y, Teraoka H, Kitamura K, et al. Adrenomedullin stimulates two signal transduction pathways, cAMP accumulation and Ca2+ mobilization, in bovine aortic endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4412–4417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JQ, Teng X, Cai Y, Tang CS, Qi YF. Activation of Akt/GSK-3beta signaling pathway is involved in intermedin(1-53) protection against myocardial apoptosis induced by ischemia/reperfusion. Apoptosis. 2009;14:1299–1307. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0398-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Kikuchi K, Maruyama Y, Urabe T, Nakajima K, Sasano H, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of adrenomedullin 2/intermedin-like immunoreactivity in human hypothalamus, heart and kidney. Peptides. 2006;27:1383–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Morimoto R, Hirose T, Satoh F, Totsune K. Adrenomedullin 2/intermedin in the hypothalamo-pituitaryadrenal axis. J Mol Neurosci. 2011;43:182–192. doi: 10.1007/s12031-010-9413-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei Y, Hyodo S, Katafuchi T, Minamino N. Novel fish-derived adrenomedullin in mammals: structure and possible function. Peptides. 2004a;25:1643–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei Y, Inoue K, Ogoshi M, Kawahara T, Bannai H, Miyano S. Identification of novel adrenomedullin in mammals: a potent cardiovascular and renal regulator. FEBS Lett. 2004b;556:53–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei Y, Hashimoto H, Inoue K, Osaki T, Yoshizawa-Kumagaye K, Tsunemi M, et al. Central and peripheral cardiovascular actions of adrenomedullin 5, a novel member of the calcitonin gene-related peptide family, in mammals. J Endocrinol. 2008;197:391–400. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MM, Samson WK. Stress hormone secretion is altered by central administration of intermedin/adrenomedullin-2. Brain Res. 2005;1045:199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MM, Bagley SL, Samson WK. Intermedin/adrenomedullin-2 acts within central nervous system to elevate blood pressure and inhibit food and water intake. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R919–R927. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00744.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MM, Bagley SL, Samson WK. Intermedin/Adrenomedullin-2 inhibits growth hormone release from cultured, primary anterior pituitary cells. Endocrinology. 2006;147:859–864. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MM, Samson WK. Intermedin 17-47 does not function as a full intermedin antagonist within the central nervous system or pituitary. Peptides. 2007;28:2171–2178. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunder F, Rebmann A, Geerts A, Kalthof B. Pharmacological and kinetic characterization of adrenomedullin 1 and calcitonin gene-related peptide 1 receptor reporter cell lines. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1235–1243. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.042283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JH, Jia YX, Pan CS, Zhao J, Ouyang M, Yang J, et al. Effects of intermedin(1-53) on cardiac function and ischemia/reperfusion injury in isolated rat hearts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;327:713–719. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JH, Pan CS, Jia YX, Zhang J, Zhao J, Pang YZ, et al. Intermedin1–53 activates L-arginine/nitric oxide synthase/nitric oxide pathway in rat aortas. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:567–572. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JH, Cai Y, Duan XH, Ma CG, Wang X, Tang CS, et al. Intermedin 1–53 inhibits rat cardiac fibroblast activation induced by angiotensin II. Regul Pept. 2009;158:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, Yuan Y, Wang X, Wu HM, Fan L, Qi YF, et al. Upregulated expression of intermedin and its receptor in the myocardium and aorta in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Peptides. 2009;30:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Bell D, Smith LR, Zhao L, Devine AB, McHenry EM, et al. Differential expression of components of the cardiomyocyte adrenomedullin/intermedin receptor system following blood pressure reduction in nitric oxide-deficient hypertension. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:1269–1281. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]