Abstract

The transcription factor AP-1 (activator protein-1) regulates a number of genes that drive tumor promotion and progression. While basal levels of AP-1 activity are important for normal cell proliferation and cell survival, overactivated AP-1–dependent gene expression stimulates inflammation, angiogenesis, invasion, and other events that propel carcinogenesis. We seek to discover genes targeted by carcinogenesis inhibitors that do not also inhibit cell proliferation or survival. Transgenic TAM67 (dominant-negative c-Jun) inhibits mouse skin tumorigenesis and tumor progression without inhibiting cell proliferation or induced hyperproliferation. Expression profiling of wild-type and K14-TAM67 mouse epidermis has revealed a number of functionally significant genes that are induced by tumor promoters in wild-type mice but not in those expressing the AP-1 blocker. The current study now identifies Wnt5a signaling as a new target of TAM67 when it inhibits DMBA/TPA-induced carcinogenesis. Wnt5a is required to maintain the tumor phenotype in tumorigenic mouse JB6 cells and Ras-transformed human squamous carcinoma HaCaT-II4 cells, as Wnt5a knockdown suppresses anchorage-independent and tumor xenograft growth. The oncogenic Wnt5a-mediated pathway signals through activation of the protein kinase PKCα and oncogenic transcription factor STAT3 phosphorylation and not through the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Similar to Wnt5a knockdown, inhibitors of PKCα blocked STAT3 activation in both mouse JB6 and human HaCaT-II4 tumor cells. Moreover, expression of STAT3-regulated genes FAS, MMP3, IRF1, and cyclin D1 was suppressed with Wnt5a knockdown. Treatment of mouse Wnt5a knockdown cells with a PKCα-specific activator rescued phosphorylation of STAT3. Thus, Wnt5a signaling is required for maintaining the tumor phenotype in squamous carcinoma cells, Wnt5a targeting by the AP-1 blockade contributes to inhibition of skin carcinogenesis, and the signaling pathway traverses PKCα and STAT3 activation. Coordinate overactivation of Wnt5a expression and STAT3 signaling is observed in human skin and colon cancers as well as glioblastoma.

Keywords: AP-1, PKC, STAT3, Wnt5a

Introduction

Overactivated transcription factor AP-1 (activator protein-1) is a major inducer of oncogenic gene expression in many cancers. The elevated AP-1 activation and its regulated target gene expression drive stages of tumor promotion and progression and are functionally important in maintaining the tumor phenotype. Although basal AP-1 expression suffices to regulate genes involved in normal physiological processes such as cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, and development, overactivation of AP-1 is required for oncogenesis.1

TAM67 (dominant-negative c-Jun), having a deleted N-terminal transactivation domain, inhibits AP-1 activation by dimerizing with Jun and Fos family proteins and rendering the complex with low activity.2 TAM67 inhibits transformation and invasion in cell culture3,4 and inhibits tumor promotion and tumor progression but not cell proliferation in multiple mouse models relevant to human carcinogenesis.5-7 These models include UVB-induced and human papillomavirus–enhanced skin carcinogenesis as well as oncogene-induced mammary8 and chemically induced lung9 carcinogenesis. Transgenic mice expressing TAM67 in the skin have proven to be a useful tool for identifying gene expression events that are important for tumorigenesis and tumor progression. Because nontoxic approaches are valuable for cancer prevention, we seek to discover genes targeted by carcinogenesis inhibitors that do not also inhibit cell proliferation or survival. The targets of TAM67 identified under conditions that inhibit carcinogenesis but not cell proliferation are candidates for contributing specifically to the carcinogenesis-suppressing activity of the AP-1 blocker. In contrast to the situation with c-Jun null mice that show embryonic lethal phenotypes,10 TAM67 transgenics are viable7 and show a relatively small number of alterations in gene expression.11

We have previously profiled the gene expression of TAM67 transgenic mouse skin and compared it to that of wild-type mice, both treated with a DMBA initiator followed by 6 hours of tumor promoter TPA (12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate) exposure.11,12 Among the early response genes whose induction is targeted by TAM67 are cyclooxygenase-2, osteopontin, matrix metalloproteinase-10, urokinase plasminogen activator, and sulfiredoxin when the AP-1 blockade specifically inhibits tumorigenesis in squamous epithelia. The targeted genes are associated with inflammation, invasion, and metastasis rather than cell proliferation or cell survival. In the current study, Wnt5a and fzd5 mRNA have emerged as late response targets from microarray profiling of 18 hours of TPA-treated TAM67 transgenic mouse epidermis compared to wild-type mice.

Secreted Wnt family ligands bind to membrane-spanning G protein–coupled receptors of the Frizzled family and activate numerous signaling pathways regulating cell polarity and organization of tissue pattern in embryonic development and maintenance.13,14 Wnt signaling pathways are classified into canonical and noncanonical based on TCF/ β-catenin dependency. On the canonical pathway, β-catenin is released from glycogen synthase kinase 3-β (GSK-3β) following GSK-3β degradation and is translocated into the nucleus. In the nucleus, β-catenin–containing complexes activate the transcription of target genes such as c-myc, Cox-2, cyclin D1, MMPs, VEGF, and Fra-1 downstream of Wnt signaling.13,15 Noncanonical Wnt pathways are TCF/ β-catenin independent. Wnt binding to fzd receptors signals to cell polarity and migration mediated by Disheveled and JNK and to cell migration and invasion through stimulated calcium flux and activation of calcium-dependent enzymes calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CAMKII), calpain, and PKC.16-20 Wnt can also signal in a β-catenin–independent fashion by binding to non-Frizzled receptors such as ROR2.21

While misregulation of the canonical pathway in cancer has been extensively studied,14 there is relatively little understanding of the roles and the mechanisms of noncanonical Wnt pathways in tumorigenesis. There are dichotomies in Wnt signaling not only with respect to β-catenin dependency but also in whether it functions as an oncogenic driver or a tumor suppressor. Overexpression of Wnt5a is associated with migration and invasiveness in several cancers including gastric and pancreatic as well as melanoma, yet it can promote β-catenin degradation in colorectal carcinogenesis, suggesting tumor suppressor activity.22-25

In this study, we demonstrate that Wnt5a expression is attenuated by TAM67 when the AP-1 blockade inhibits tumorigenesis and tumor progression in the mouse epidermis. In addition to its association with tumor induction and progression, Wnt5a expression is important for the maintenance of tumor phenotypes in mouse JB6 RT101 cells. Knockdown of Wnt5a not only suppresses tumor phenotypes but also inhibits phosphorylation of PKCα and of STAT3 at Tyr705. The Wnt5a signaling through PKC and STAT3 is observed in both transformed mouse epidermal cells and Ras-transformed human keratinocytes, and Wnt5a knockdown suppresses squamous carcinoma growth. Activation of STAT3 and overexpression of STAT3 target genes have been linked to multiple human cancers. In some cancers, including skin, colon, and glioblastoma, overactivation of Wnt5a expression occurs coordinately with activated STAT3 signaling.

Results

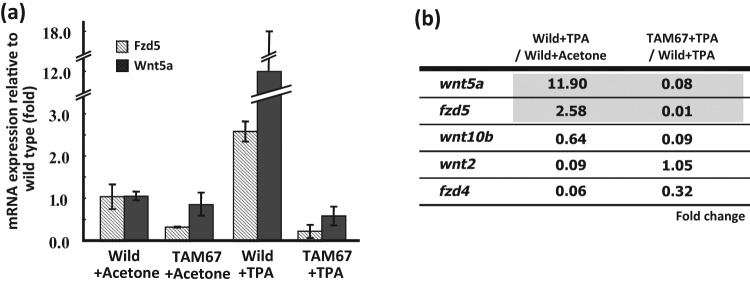

Wnt5a mRNA expression is induced by TPA in wild-type but not in TAM67 transgenic mouse epidermis

To verify differential mRNA expression seen in preliminary microarray or conventional RT-PCR, wild-type and TAM67 transgenic mouse epidermal RNAs were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR for TPA (18 hours)–induced Wnt5a and other fzd and Wnt family members. Although early response genes such as cyclooxygenase-2, ornithine decarboxylase, and sulfiredoxin are known to be important in the process of tumor promotion, so too are late response genes (i.e., 18 hours induced) such as the chromatin modifier HMGA1.11,12,26 The basal level of Wnt5a mRNA expression was unaffected in TAM67 transgenic mice compared with wild-type mice. TPA exposure (18 hours) induced Wnt5a by more than 12-fold and receptor fzd5 by 3-fold in wild-type mice. In contrast, the epidermally expressed TAM67 completely suppressed the TPA induction of both Wnt5a and fzd5 (Fig. 1A). Comparison with other Wnt and fzd family members Wnt10b and Wnt2, alternative ligands for the fzd5 receptor, and fzd4, an alternative receptor for Wnt5a,27,28 showed that none of the 3 was induced in the epidermis by TPA, while Wnt2 and fzd4 were substantially repressed by TPA (Fig. 1B). The repression of Wnt2 was completely counteracted and that of fzd4 was partially counteracted by TAM67. Thus, the mRNAs for Wnt5a and its receptor fzd5, unlike other family members measured, show the behavior expected for a TAM67 target gene operative in tumor promotion, namely up-regulation by the tumor promoter and counteraction by the AP-1 blockade.

Figure 1.

Wnt5a and fzd5 mRNAs are up-regulated by TPA and counteracted by TAM67 expression in the mouse epidermis. (A) Expression of Wnt5a and fzd5 mRNA was induced by TPA, and TPA-induced expression was repressed completely by TAM67 expression in the mouse epidermis. (B) Wnt10b, Wnt2, and fzd4 (other fzd/Wnt receptors or ligands) are regulated differently from Wnt5a and fzd5. The ratios of Wnt5a, fzd5, Wnt10b, Wnt2, and fzd4 mRNA were compared in the mouse epidermis 18 hours after TPA induction in wild-type (left) or K14-TAM67 transgenic mice (right). Full-thickness dorsal skin samples were harvested from wild-type and TAM67 transgenic mice treated with a single dose of acetone or TPA (10 nmol in 200 µL acetone) 2 weeks after DMBA (400 nmol per 200 µL acetone) initiation. RNA expression ratios in the mouse epidermis were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR with normalization by β2-microtubulin. Results were obtained with 2 independent experiments each in triplicate using 2 different samples. Gene expression ratios were compared with P value (<0.05) calculated by the Student t test. The epidermis was separated from the dermis by snap freezing in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in a guanidinium-based lysis solution of ToTALLY RNA kit (Ambion) as described in Materials and Methods.

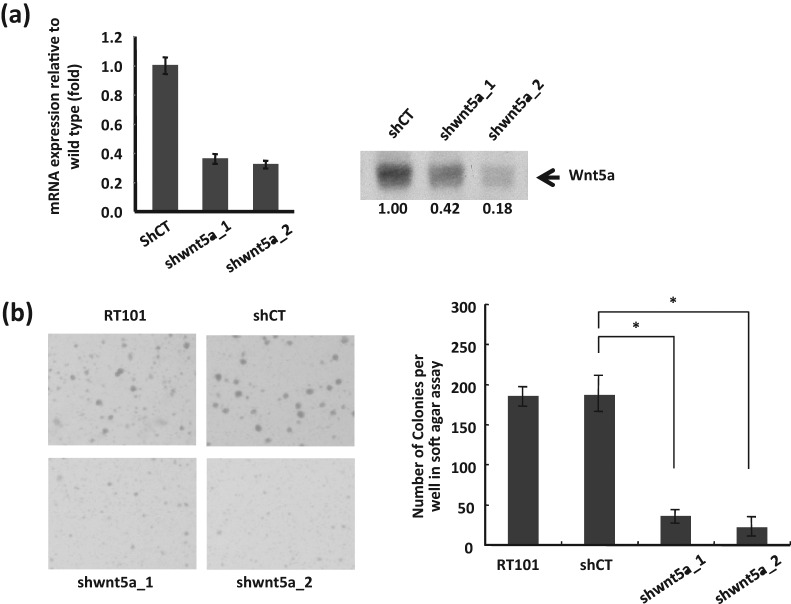

Tumor phenotype is suppressed by Wnt5a knockdown in mouse JB6 RT101 cells

To investigate whether Wnt5a signaling is required as an oncogenic regulator, we asked whether tumor phenotype would be suppressed by Wnt5a deficiency. We first attempted to assess the transformation response phenotype in JB6 mouse epidermal P+ (transformation sensitive) cells by assaying for the possible loss of TPA-induced transformation response with Wnt5a knockdown. However, because both basal and TPA-induced levels of Wnt5a were low in P+ cells (Suppl. Fig. S1), knockdown was not carried out. In contrast, JB6-transformed RT101 cells expressed a high level of Wnt5a. The JB6 RT101 epidermal tumor cells (also known as R6101) were generated from JB6 P+ Cl41 cells after repeated TPA exposure29 and exhibit growth under anchorage-independent conditions in the absence of tumor promoter induction30 as well as tumor growth following subcutaneous injection into nude mice.31 We assessed tumor phenotype by performing anchorage-independent growth assays using the RT101-transformed mouse JB6 cells down-regulated for Wnt5a by the expression of shWnt5a (Fig. 2A). JB6 RT101/Wnt5a knockdown clones were acquired by infection with lentivirus expressing mouse short hairpin (sh) to Wnt5a and compared with shRNA control as described in Materials and Methods. Quantification of Wnt5a mRNA was carried out by quantitative RT-PCR and of Wnt5a protein by immunoblot shown in Figure 2A. mRNA expression was decreased by about 65% in both clones, while Wnt5a protein expression was decreased by 58% and 82%, respectively, in the 2 clones. Due to the lack of antibody for fzd5 protein needed to assess knockdown efficiency, we did not pursue a detailed characterization of fzd5-deficient cells. Figure 2B shows that the 2 independently derived Wnt5a knockdown clones, shWnt5a-1 and shWnt5a-2, showed significantly decreased production of anchorage-independent colonies, with about an 80% to 90% decrease in colony number. This result suggests that Wnt5a signaling is required for maintaining the tumor phenotype in the JB6 RT101 mouse epidermal cells. Recombinant Wnt5a, when added to the soft agar assay, did not rescue colony formation (data not shown); thus, although Wnt5a knockdown was substantial, the possibility that indirect targets contribute, in addition to Wnt5a deficiency, cannot be excluded. Noteworthy however is that knockdown of Wnt5a receptor fzd5 also inhibited soft agar growth (Suppl. Fig. S2), providing independent support for a requirement for Wnt5a signaling to maintain the tumor phenotype in JB6 RT101 cells.

Figure 2.

Anchorage-independent growth is suppressed by knockdown of Wnt5a in mouse epidermal RT101 cells. (A) The efficiency of Wnt5a knockdown in RT101 cells was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR (left) and immunoblot (right) with antibody to Wnt5a. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with 2 independent experiments each in triplicate. (B) Inhibition of Wnt5a by shRNA suppressed anchorage-independent growth in shWnt5a clones 1 and 2. The results were obtained with 2 independent experiments each in triplicate. Determination of colony number and size is described in Materials and Methods. A representative image is shown in the left panel. *Total colony numbers per well were calculated and compared, with P value (<0.01) calculated by the Student t test as shown in the right panel (B).

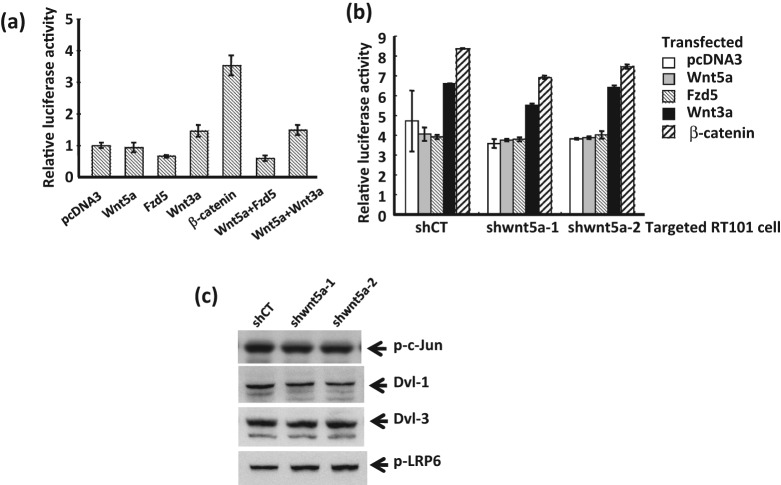

Wnt5a signaling in JB6 RT101 tumor cells is independent of TCF/β-catenin

A positive feedback loop has been observed in the case of at least 2 TAM67 targets, namely HMGA126 and sulfiredoxin.12 We therefore asked whether the signaling by this target of the AP-1 blocker might be functioning upstream of AP-1 in addition to downstream. Transient co-transfection of Wnt5a, fzd5, or both Wnt5a and fzd5 produced no stimulation of luciferase transcription from the 4× AP-1 promoter in JB6 RT101 cells (Suppl. Fig. S3), rendering a positive feedback loop unlikely. Although an autocrine loop appears not to occur in this context with JB6 cells, it may occur in other contexts such as the Wnt5a-Ror2-Rac1-Disheveled pathway described for fibroblast L cells.18

We next queried the possibility that the suppression of the tumor phenotype by Wnt5a knockdown in RT101 cells occurred through a TCF/β-catenin–dependent canonical pathway. Expression plasmids for Wnt5a or fzd5, and Wnt3a and β-catenin as controls, were transfected into RT101 cells along with the Super-TOP flash luciferase reporter containing multiple TCF/β-catenin binding sites. In Figure 3A, neither fzd5 nor Wnt5a induced TCF/β-catenin–dependent transcriptional activity in RT101 cells. In contrast, both Wnt3a, a known inducer of canonical Wnt signaling, and β-catenin overexpression increased transcriptional activity. Moreover, the inhibition of the β-catenin–dependent reporter seen with fzd5 and the induction seen with Wnt3a were not altered by co-expression of Wnt5a. To further confirm the lack of requirement of β-catenin for Wnt5a signaling in the mouse epidermal cells, shWnt5a RT101 cells were transfected as shown in Figure 3B. Measurement of transcription from the Super-TOP flash reporter revealed TCF/β-catenin signaling was not suppressed by knockdown of Wnt5a. Wnt3a and β-catenin stimulated transcription from the β-catenin–dependent promoter to a similar extent in shControl and shWnt5a cells. β-catenin expression was not changed by Wnt5a knockdown or overexpression in the RT101 cells (data not shown). Thus, Wnt5a, unlike Wnt3a, appears to exert no effect on the β-catenin–dependent canonical pathway in the transformed mouse epidermal JB6 RT101 cells. Because noncanonical Wnt5a signaling in some contexts activates Disheveled (Dvl) proteins, co-receptors LRP5/6 and Jun kinase (JNK),16,18,32 we assessed the possibility that Wnt5a might signal through these mediators. Figure 3C shows that knockdown of Wnt5a in mouse JB6 tumor cells produced little or no change in the expression of Dvl-1, Dvl-3, or LRP6 or in the activation of JNK as measured by Ser73 phospho–c-Jun formation. This appears to exclude a noncanonical pathway associated with cell polarity and migration as well as TCF/β-catenin–dependent pathways from mediating Wnt5a signaling in mouse epidermal JB6 RT101 tumor cells.

Figure 3.

Wnt5a does not regulate canonical (TCF/β-catenin dependent) signaling in mouse JB6 RT101–transformed cells. (A) fzd5 and Wnt5a do not induce TCF/β-catenin–dependent transcription activity in RT101 cells. TCF/β-catenin signal was measured in RT101 cells transiently overexpressing Wnt5a, fzd5, Wnt3a, and β-catenin each or a combination of Wnt5a with fzd5 or Wnt3a. (B) Knockdown of Wnt5a signal did not change β-catenin–mediated canonical signaling. Expression plasmids for Wnt3a or β-catenin were transfected into RT101 cells expressing shWnt5a or shControl separately. pcDNA-3 was used as control vector. TCF-dependent transcription activity in RT101 cells (A) or RT101 expressing shRNA target Wnt5a or shControl (B) was measured by Super-TOP flash. (C) Noncanonical signaling through Disheveled, JNK, or LRP6 is not targeted by Wnt5a knockdown. Endogenous protein expression was measured with whole cell extract of JB6-transformed RT101 cells expressing shRNA target Wnt5a or shControl by immunoblot analysis. Immunoblots were probed with antibodies for phospho–c-Jun, Dvl-1, Dvl-3, and phospho-LRP6.

STAT3 is activated in a Wnt5a-dependent fashion in mouse epidermal tumor cells

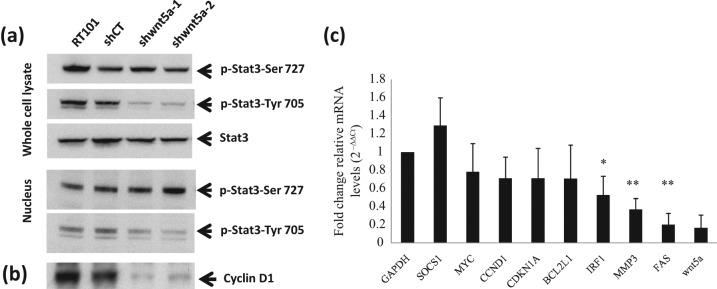

Wnt5a increases the invasion and metastasis of melanoma cells by activating signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3) phosphorylation at serine 727 and STAT3 transport into the nucleus, where it down-regulates the expression of melanoma differentiation antigens.33 STAT3 is also required for nonmelanoma skin carcinogenesis.34-36 As shown in Figure 4A, both of the 2 shWnt5a clones showed suppression of STAT3 phosphorylation, but at tyrosine 705, not at serine 727, as seen in melanoma. Phosphorylation of STAT3 at both Tyr705 and Ser727 is needed for maximal activation of it as a transcription factor.37,38 In contrast to Wnt5a knockdown, Wnt5a overexpression did not change the level of STAT3 phosphorylation (data not shown). We also examined the effect of Wnt5a deficiency on transcriptional targets of STAT3. The expression of cyclin D1, a well-known downstream target of STAT3, was repressed when measured at the protein level (Fig. 4B). Expression analysis of STAT3 target mRNAs by quantitative RT-PCR demonstrated the down-regulation of several targets, with 2-fold or greater inhibition of IRF1, MMP3, and FAS in shWnt5a cells (Fig. 4C). Thus, pTyr705-STAT3 appears to mediate an oncogenic signaling pathway downstream of Wnt5a in JB6 RT101 epidermal tumor cells.

Figure 4.

Wnt5a is required for activation of STAT3. (A) There is a significant decrease in phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705 in RT101 cells with knockdown of Wnt5a, but STAT3 phosphorylation at Ser727 is unchanged. (B) Expression of cyclin D1, a STAT3 target gene, in RT101 cells expressing shRNA targeting Wnt5a or shControl. Endogenous protein expression was measured with whole cell extract of RT101 cells expressing shRNA target Wnt5a or shControl by immunoblot analysis using antibodies for phospho-STAT3 at 705, phospho-STAT3 at 727, STAT3, and cyclin D1. Nuclear phosphorylated STAT3 expression was detected by using a nuclear fraction of shWnt5a clones. (C) STAT3-regulated gene expression decreased with Wnt5a knockdown. mRNA level was measured by quantitative RT-PCR from 2 independent experiments with shControl and shWnt5a-1 clones, and mean and standard deviation from 3 replicate RT-PCRs are shown. *P < 0.05. **P ≤ 0.001.

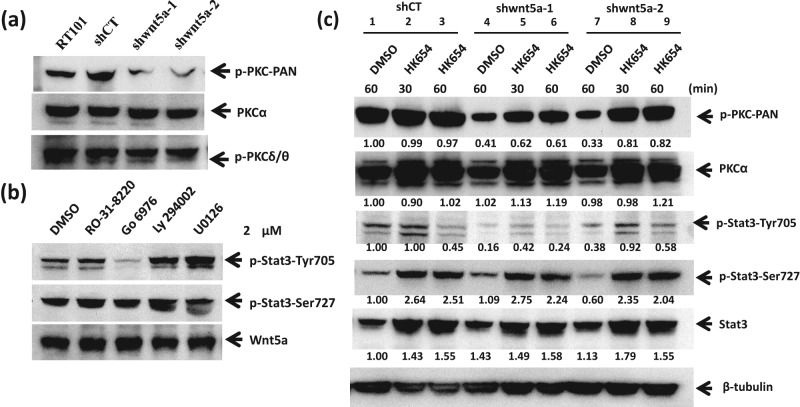

Phosphorylation of PKC is suppressed in the shRNA-targeted Wnt5a cells

Because Wnt5a has been shown in colorectal cancer cells to activate calcium-dependent PKCα, which activates RORα, an antagonist of canonical β-catenin signaling,39 and because PKC activation has been observed in melanoma cells overexpressing Wnt5a,40,41 we asked whether Wnt5a might also activate PKC in mouse epidermal tumor cells. Figure 5A shows substantial suppression of phospho-PKC in both Wnt5a knockdown cell lines. Figure 3B shows, however, that events downstream of Wnt5a deficiency did not lead to the stimulation of canonical β-catenin signaling, as the shWnt5a cells showed no increase in Super-TOP flash luciferase activity with or without co-transfection of Wnt3a or β-catenin. Thus, Wnt5a appears to activate the phosphorylation of PKC in addition to that of STAT3 without antagonizing β-catenin–dependent signaling in epidermal tumor cells.

Figure 5.

PKCα is required for STAT3 activation by Wnt5a signaling in RT101 cells. (A) Phosphorylation of PKC is decreased in RT101 cells by Wnt5a knockdown. Endogenous protein expression was measured with whole cell extracts of JB6-transformed RT101 cells expressing shRNA targeting Wnt5a or shControl by immunoblot analysis. (B) The decrease in phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705, but not Ser727, was attributable to decreased phosphorylation of PKCα. RT101 cells were treated with kinase inhibitors, RO-31-8220 (pan-PKC), Go 6976 (PKCα and β), Ly 294002 (PI3K), and U0126 (MEK1/2) at 2 µM for 24 hours. (C) Rescue of STAT3 phosphorylation by treatment of Wnt5a knockdown JB6 RT101 cells with a PKCα-specific activator HK654 (2 µM). Immunoblots were probed with antibodies for phospho-pan-PKC (A), PKCα (A, D), phospho-PKCδ/θ (A), phospho-STAT3 (Ser727 and Tyr705) (B-D), STAT3 (D), pPKCα (D), β-tubulin (D), and Wnt5a (B).

STAT3 phosphorylation at Tyr705 is dependent on PKCα

Because the phosphorylation of both STAT3 and PKC is attenuated by knockdown of Wnt5a, we asked whether all 3 events were on the same pathway in mouse RT101 epidermal tumor cells. Figure 5B shows that pan-PKC inhibitor RO-31-8220 (a staurosporine analog) and PKCα/β/γ-specific inhibitor Go 6976 suppressed the phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705 but not at Ser727, showing the same specificity as seen for Wnt5a deficiency. The PKCα/β/γ-specific inhibitor (Go 6976) suppressed STAT3-705 phosphorylation at concentrations as low as 0.5 µM, while the RO-31 compound required concentrations higher than 2 mM to block phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705 (data not shown). Because JB6 RT101 cells express PKCα, but not PKCβ or γ,42 we can conclude that Tyr705 phosphorylation of STAT3 is dependent on PKCα. The inhibition of PI3K by Ly 294002 or MEK1/2 by U0126, respectively, did not diminish the phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705 (Fig. 5B). In contrast to mouse epidermal RT101 tumor cells, HEK293, MCF7, and MDA-MB-231 cells exposed to PKCα inhibitor Go 6976 did not show altered phosphorylation of STAT3 (data not shown). If Wnt5a, PKCα, and STAT3 are operating on the same pathway, a PKC activator would be expected to reverse the suppression of phospho-STAT3 at Tyr705 seen in RT101 cells expressing shRNA targeting Wnt5a. Figure 5C shows the predicted rescue when shWnt5a cells were treated with PKCα-specific HK654.43 Densitometry analysis of the p-PKCα levels as well as of the total PKCα shows a shWnt5a-induced decrease in p-PKCα to 41% and 33% of control that is partially rescued to 62% and 81% by the PKCα activator, respectively. In contrast, there is no significant change in PKCα protein with shWnt5a or the PKCα activator. Exposure to the PKCα activator produced nearly complete restoration of p-STAT3-Tyr705 at 0.5 hours in clone 2 (compare lanes 1, 7, and 8) and partial rescue in clone 1 (compare lanes 1, 4, and 5). Thus, TAM67 target gene Wnt5a signals through PKCα and STAT3 to maintain the tumor cell phenotype in mouse epidermal tumor cells. Activation of the kinase putatively responsible for STAT3 phosphorylation, Jak2,37 was not detected by available phospho-specific antibodies in the JB6 RT101 tumor cells, but Jak2 protein was expressed equally in Wnt5a-deficient cells and controls (data not shown). Taken together, the data support a requirement for PKCα in the Wnt5a-mediated signaling to activate STAT3 in epidermal tumor cells.

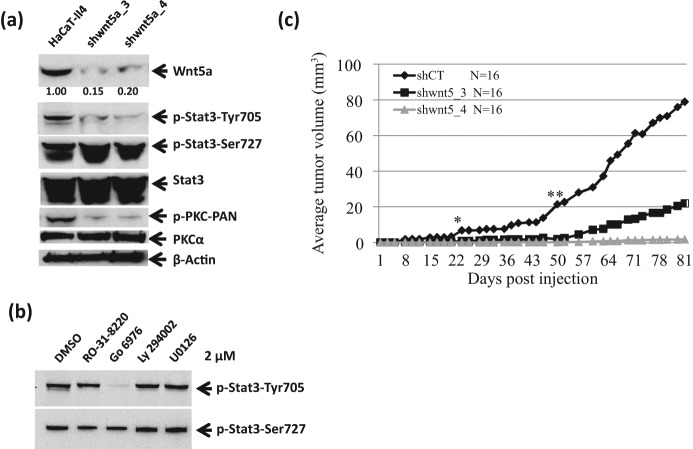

Wnt5a knockdown in human epidermal squamous carcinoma cells HaCaT-II4 suppresses the activation of PKC and STAT3

To extend the inquiry to human epidermal squamous carcinoma cells, we used Ha-RasV12–transformed immortalized HaCaT cells designated HaCaT-II4.44-46 As shown in Figure 6A, the HaCaT-II4 cells expressed high levels of Wnt5a and phospho-STAT3 phosphorylated at Tyr705. Knockdown of Wnt5a in the HaCaT-II4 cells decreased the levels of phospho-PKC and phospho-STAT3 at Tyr705 in 2 independent clones. Figure 6B demonstrates that PKC inhibitors suppress Tyr705 phosphorylation of STAT3. Because the Go 6976 inhibitor is specific for PKCα/β/γ, and because epidermal cells express only PKCα of those 3, we can conclude that PKCα is responsible. Thus, the Wnt5a to PKCα to STAT3-705 signaling is seen in human as well as mouse epidermal tumor cells.

Figure 6.

Wnt5a knockdown recapitulates suppression of PKC and STAT3 phosphorylation at Tyr705 as well as suppression of tumor phenotypes in human squamous carcinoma HaCaT-II4 cells. Phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705, not Ser727, and of PKCα decreases with knockdown of Wnt5a in Ras-transformed human keratinocyte HaCat-II4 cells. (B) The phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705 was decreased in transformed HaCaT-II4 cells by PKC inhibitor treatments. (C) Wnt5a deficiency suppresses tumor growth in xenografts. HaCaT-II4 cells transduced with control (diamonds) or 2 independent clones of Wnt5a shRNA, shWnt5a-3 (squares) and shWnt5a-4 (triangles), were injected subcutaneous into each flank of SCID mice. Mean tumor volume (mm3) for N of 16 for each group is shown. *P < 0.01. **P < 0.005 relative to control shRNA HaCaT-II4 cells.

Wnt5a deficiency suppresses tumor growth of human HaCaT-II4 cells

To determine whether squamous cell carcinoma growth required Wnt5a signaling, 2 million cells each of the HaCaT-II4/shControl and the 2 independent lines of HaCaT-II4/shWnt5a cells were injected subcutaneously into nude mice as shown in Figure 6C. Caliper measurements of tumor volume demonstrate the substantial suppression of tumor growth during a period of 81 days in response to the Wnt5a knockdown. Tumor growth in the Wnt5a knockdown became significantly different from the control by day 22 (P < 0.01). Average tumor volume per mouse at 81 days reached 78.8 mm3 for shControls in contrast to 21.9 (P < 0.0004) and 1.7 (P < 0.0009) mm3 for the Wnt5a knockdown cells. Thus, growth of human squamous cell carcinomas requires Wnt5a signaling.

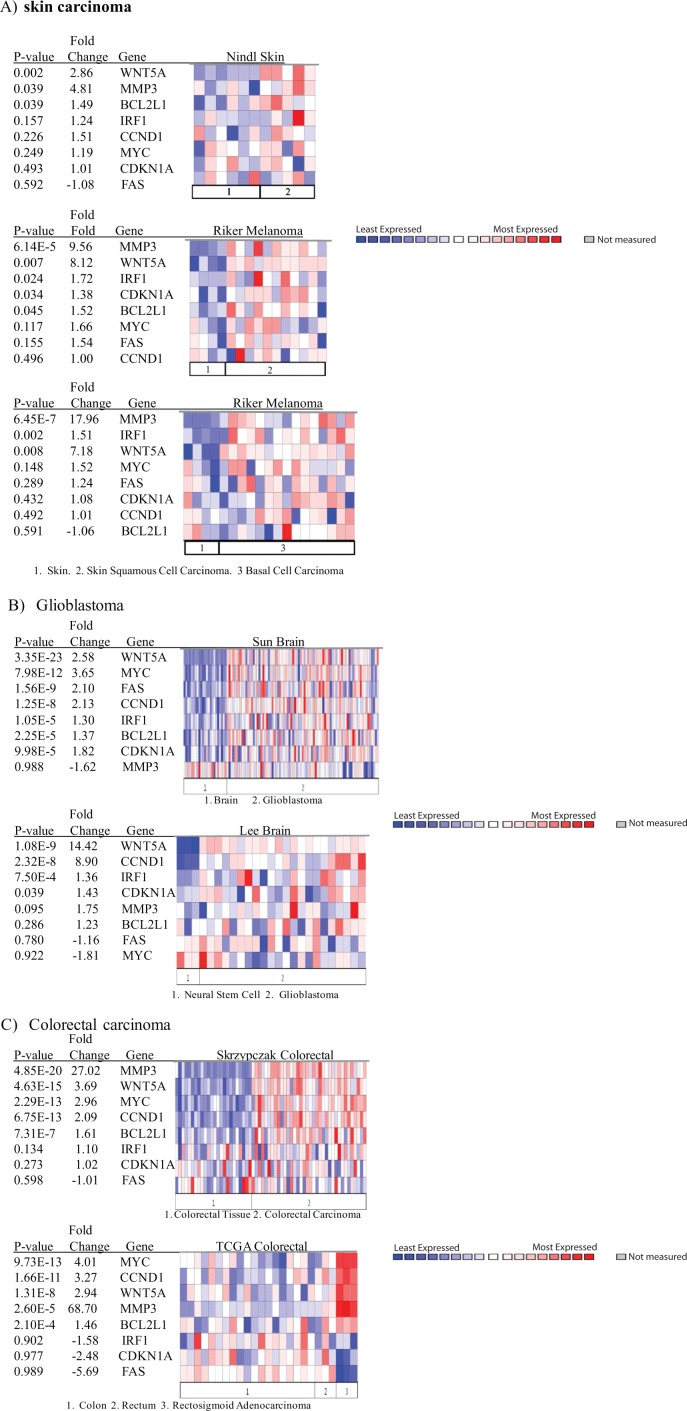

Wnt5a overexpression correlates with STAT3-regulated gene expression in human cancer

We queried the Oncomine database to investigate the relationship between Wnt5a expression and that of STAT3 transcriptional gene targets in human carcinomas. Specifically, we analyzed the expression of Wnt5a with the STAT3 target genes discovered by RT-PCR to be down-regulated in Wnt5a-deficient JB6-transformed cells (Fig. 4C). Using an analysis comparing cancer versus normal and specifically the Nindl et al. skin dataset for skin squamous cell carcinoma,47 we find that there is a strong correlation between the overexpression of Wnt5a and STAT3 target gene expression in skin squamous cell carcinoma versus normal skin (P = 0.002) (Fig. 7A). Similarly, using the Riker et al. melanoma dataset,48 there is a strong correlation between Wnt5a overexpression and STAT3 target genes for both squamous (P = 0.007) and basal (P = 0.008) cell carcinomas versus normal skin (Fig. 7B and 7C). Additionally, we determined the relationship in other cancer sites between Wnt5a overexpression and increases in the identified set of STAT3-regulated genes. Using stringent criteria that included all cancer versus normal analysis and a threshold P value = 1−6 for Wnt5a overexpression, we detected a total of 5 datasets that met these criteria. The cancers that contained a significant correlation with Wnt5a expression and STAT3 target genes include brain, colorectal, and lung cancers (data not shown) (Fig. 7B and 7C). Two of the 5 datasets included brain cancer datasets, Sun et al. brain dataset49 (P = 3.35−23) (Fig. 7B), which compares the normal brain to glioblastoma samples, and Lee et al. brain dataset50 (P = 1.08−9) (Fig. 7B), which compares neural stem cells to glioblastoma samples. In both datasets, there is a clear correlation between increased Wnt5a expression and STAT3-regulated genes. An additional carcinoma that significantly overexpressed Wnt5a and STAT3-regulated genes was colorectal carcinoma in which Oncomine detected 2 datasets that met our criteria. These included the Skrzypczak et al. colorectal dataset51 (P = 4.63−15) (Fig. 7C) and the TCGA colorectal dataset (P = 1.31−8) (Fig. 7C). Lastly, the Bhattacharjee et al. lung dataset52 (P = 2.16−7) (data not shown) demonstrated a significant increase in the overexpression of Wnt5a and STAT3-regulated genes as well. Thus, multiple human cancers show the up-regulation of STAT3-regulated gene expression when Wnt5a expression is elevated.

Figure 7.

Wnt5a overexpression correlates with STAT3-regulated gene expression in human cancer. The heat maps represent raw data from numerous studies comparing gene expression levels of Wnt5a and STAT3-regulated genes in normal and cancer tissues. The P values represent the Student t test comparing gene expression levels in normal and cancer samples. The fold change in expression and the gene name are provided as well. The genes that display an increase in the cancerous tissue are shown in red. The studies shown were conducted in (A) skin cancer by Nindl et al.47 and Riker et al.,48 (B) glioblastoma by Sun et al.49 and Lee et al.,50 and lastly, (C) colorectal carcinoma by Skrzypczak et al.51 and the TCGA set (unpublished data available on Oncomine). The skin analysis was performed using a criterion of P = 0.002 for Wnt5a overexpression. The analyses for glioblastoma and colorectal carcinoma were performed using a criterion with a threshold P = 1E-6 for Wnt5a overexpression. Oncomine was used for analysis.

Note: Colors are z-score normalized to depict relative values within rows. They cannot be used to compare values between rows.

Discussion

This study identifies Wnt5a as a functionally significant target of the AP-1 blocker TAM67 under conditions in which tumorigenesis and tumor progression are inhibited. TAM67 expression completely repressed TPA-induced Wnt5a expression in the mouse epidermis. The up-regulation with TPA and down-regulation by TAM67 distinguish Wnt5a as a target of TAM67 in contrast to other fzd or Wnt genes measured. Wnt5a joins other targets discovered, among them Cox-2, osteopontin, uPAR, MMP-10, HMGA1, and sulfiredoxin. Like these other early and late response targets of the AP-1 blocker, Wnt5a appears to contribute to oncogenic activities such as migration, invasion, and metastasis rather than cell proliferation or cell survival32,53,54 when measured in a carcinogenesis model.

Wnt5a functions in skin and epidermal cells as an oncogene rather than a tumor suppressor

Although in colon cancer, Wnt5a signaling can antagonize β-catenin signaling to function as a tumor suppressor,39 and it also functions as a tumor suppressor in breast cancer,55 in skin cancer models, Wnt5a signaling acts as an oncogenic driver. Moreover, Wnt5a signaling does not antagonize TCF/β-catenin signaling in either mouse or human epidermal tumor cells. Wnt5a is also associated with oncogenic activity in melanoma and pancreatic, gastric, prostate, and bone cancers.13,15,21,54

Wnt5a appears to regulate both early and later stages of carcinogenesis

Wnt5a deficiency suppresses the tumor phenotype in skin tumor cells, while overactivated Wnt5a signaling is associated with tumor progression in skin and other cancers.22,54,56 Wnt5a deficiency may function in inhibiting not only tumor progression but also tumor induction. Our analysis of JB6-transformed RT101 and Ha-RasV12–transformed HaCaT-II4 cells shows that Wnt5a knockdown suppressed the tumor phenotype as measured by anchorage-independent growth and tumor xenograft growth (Figs. 2B and 6C). The observation that Wnt5a is among the genes whose expression is down-regulated at stages preceding the development of papillomas and their conversion to carcinomas in the TAM67 mice suggests that Wnt5a may be important in driving tumorigenesis as well as tumor growth and tumor progression. Thus, Wnt5a might be targeted either for cancer prevention or cancer treatment in skin and certain other cancer sites.

Wnt5a receptors

ROR2 is an exclusive receptor for Wnt5a, while fzd2, 4, or 5 can signal by binding to Wnt5a or to other Wnt proteins. ROR2 signals only in a β-catenin–independent manner, while fzd5 can activate noncanonical or canonical pathways.56 ROR2 (receptor tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 2) has shown oncogenic activity in tumor promotion and progression. ROR2 stimulates invasion and metastasis in osteosarcoma by the interaction with Wnt5a and fzds on a noncanonical signaling pathway.21 The ROR2/fzd7 association mediates Wnt5a-induced activation of JNK, resulting in AP-1 transcriptional activation in fibroblasts.18,32 However, AP-1 activation by Wnt5a stimulation through kinases such as JNK was not observed in epidermal cell lines. In the case of normal skin and skin cancer, the operative receptor for Wnt5a is not known.

Wnt5a signals through STAT3 activation

Wnt5a signaling in the mouse and human epidermis and epidermal cells appears to proceed not through activating or inhibiting canonical signaling but instead proceeds through the activation of calcium-dependent PKCα to the activation of STAT3 at Tyr705 without change in Ser727 activation or total STAT3 expression. This contributes to the activation of tumor promotion and progression. Phosphorylation of Tyr705, along with that of Ser727, both residues residing in the transactivation domain, is important for the activation of STAT3 as a transcription factor, as it controls nuclear entry and DNA binding.38 STAT3 is known to be required for skin carcinogenesis, as its deficiency renders mice resistant to carcinogenesis induced by DMBA-TPA,34 and STAT3 overexpression in mice enhances UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis.35 STAT3 activates the transcription of a number of oncogenic mediators, among them cyclin D1, Bcl-XL, and c-Myc.57 IRF1, MMP3, and FAS mRNA expression and cyclin D1 protein expression are down-regulated by Wnt5a knockdown in transformed JB6 RT101 cells. Comparison of gene expression in multiple human cancers reveals that activation of Wnt5a expression appears to be coordinately up-regulated with that of STAT3-regulated genes in skin, brain, and colorectal cancers.47-52 Because STAT3 targets are also targets of other transcription factors, whether STAT3 prevails is context dependent. Although cyclin D1 expression was regulated by Wnt5a, cyclin D1 may play a different role in the maintenance of tumor cells than in the induction of tumors. Matthews et al.11 reported that DMBA-TPA–treated TAM67 expressing the mouse epidermis was not inhibited for cell proliferation or for expression of cyclin D1 or other proliferation-associated genes. As shown in Figure 7, cyclin D1 was moderately overexpressed in human skin carcinomas and substantially overexpressed in colon carcinomas, consistent with the possibility that it is needed for tumor growth but not tumorigenesis.

STAT3-Tyr705 phosphorylation is dependent on PKCα

PKC appears to be a required mediator of Wnt5a when it activates STAT3 and tumor progression in mouse and human epidermal cells. The PKC isotype responsive to Wnt5a knockdown appears to be PKCα in transformed JB6 RT101 cells. The JB6-transformed cells, along with transformation-sensitive and transformation-resistant JB6 variants, express abundant PKCα with undetectable expression of PKCβ and PKCγ.42 Also not observed was any change in PKCµ (data not shown) or PKCδ/θ activation. The major PKC isotype–mediating tumor promoter–induced signaling in mouse and human basal keratinocytes is PKCα.58 Activation of PKCα functions as a regulator to mediate cell migration and motility induced by Wnt5a signaling through a noncanonical pathway in melanoma cells.41 PKCα appears to be a required mediator of Wnt5a when it stimulates the activation of STAT3 by phosphorylation at Tyr705 and tumor progression in mouse and human epidermal cells. PKCα overexpression, unlike that of STAT3, does not enhance mouse skin carcinogenesis.59 PKCα activation is however required for tumor promotion by the proinflammatory cytokine TNFα.58 Other PKC isotypes have also been implicated in Wnt signaling. For example, in prostate cancer, Wnt5a appears to signal through novel PKCµ/PKD to activate JNK, AP-1, and AP-1 target MMP-1 to stimulate cancer progression.54 Although STAT3 activation appears to be dependent on PKCα in mouse and human epidermal tumor cells, Tyr705 would not be a direct substrate of PKC, a serine/threonine kinase. The kinase directly responsible for Tyr705 phosphorylation on the Wnt5a signaling pathway is putatively Jak2, an enzyme that is expressed in epidermal tumor cells. Alternatively, one or more protein tyrosine phosphatases, such as TC-PTP, SHP1, or SHP2, might dephosphorylate STAT3-Tyr705 more efficiently in the Wnt5a knockdown cells. Tyr705 is dephosphorylated in mouse keratinocytes exposed to UVB radiation.60

In summary, Wnt5a appears to be unique among Wnt family members in joining other targets of AP-1 blockade in mediating epidermal tumorigenesis, tumor growth, and tumor progression. The novel Wnt5a signaling through PKCα and STAT3-Tyr705 is observed in human squamous cell carcinoma cells as well as mouse epidermal tumor cells.

Materials and Methods

Inhibitors, activators, and cell lines

Ly 294002 and U0126 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), and pan-PKC inhibitor RO-31-8220 and PKCα/β/γ-specific inhibitor Go 6976 were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). PKCα-specific activator HK654 was provided by Victor Marquez (NCI, Frederick, MD). Mouse JB6-transformed RT101 (R6101) cells29 were maintained in Eagle’s Minimal Essential Medium (Whittaker Biosciences, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 4% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 25 µg/mL gentamycin and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Human keratinocyte Ha-RasV12–transformed HaCaT-II4 cells44 were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 25 µg/mL gentamycin and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

The transformed (Tx) JB6 RT101 cells are a well-characterized line derived from P+ JB6 clone 41 cells by repeated exposure to TPA as described.29 The original name was R6101 (see Figs. 3 and 4 and Table 1 in Colburn et al.29). After several passages, the R6101 cells spontaneously and stably transformed to an anchorage-independent and tumorigenic phenotype. The molecular and cellular characterizations of the transformed RT101 cells have been described30,31,61-63 as well as more recently by multiple investigators.12 Differential display of mRNA in P+, P−, and transformed RT101 cells identified several genes preferentially expressed in nontransformed cells (e.g., TIMP-3) and others with elevated expression in the transformed cells (e.g., Srx/Npn 1). Oncogenic proteins such as sulfiredoxin and osteopontin show elevated basal levels in transformed JB6 RT101 cells. The transformed JB6 cells have elevated AP-1 activity due not to Jun/Fos expression change but to differential AP-1 activation by MEK/ERK.64 JB6 cells show progressively increasing AP-1 activation (basal and tumor promoter induced) from P− to P+ to transformed.65,66

Transfection experiments and luciferase reporter assay

Transient transfection experiments were performed with FuGene 6 transfection reagent (Roche, Branchburg, NJ) according to the manufacturer’s manual. Luciferase assay was performed by the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI). All expression plasmids were kindly provided by Terry Yamaguchi (NCI), and Wnt5a, fzd5, Wnt3a, and β-catenin (ΔN) were transfected into JB6 RT101 cells or HaCaT-II4 cells (provided by G. Tim Bowden, University of Arizona) along with the Super-TOP flash reporter containing 6 times the TCF binding sites and pRL-TK as a control.

Immunoblot and cytoplasmic and nuclear preparation

RT101 cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (10 mmol/L Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1 mmol/L EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% deoxycholate, and protease inhibitor). Whole cell extracts were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the following antibodies: Wnt5a, phospho-c-Jun (Ser73), phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (phospho-STAT3; Tyr705 and Ser727), Dvl-1, Dvl-3, STAT3, phospho-LRP6, phospho-pan-PKC, phospho-PKCα, phospho-PKCδ/θ, and cyclin D1 were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared from RT101 cells by NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated by ToTALLY RNA kit (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, Austin, TX) from the mouse epidermis or RT101 cells expressing shRNA target Wnt5a, fzd5, or shControl according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Full-thickness dorsal skin was harvested after TPA or acetone treatment, and the epidermis was separated from the dermis as previously described.11 The first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of the isolated total RNA using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with oligonucleotide primers. cDNA was purified by QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s manual. Real-time PCR was done with iQ SYBR Green Supermix and iQ5Multicolor reverse transcription-PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Primers for endogenous mouse Wnt5a, Wnt2, Wnt10b, fzd5, and fzd4 were designed by the Primer 3 program.67 Mouse β-2 microglobulin (β2m) or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (mGAPDH) was used as a control. The sequences for RT-PCR are as follows: Wnt5a, F 5′-CACTTAGGGGTTGTTCTCTGA-3′, R 5′-ATATCAGGCACCATTAAACCA3′; Wnt2, F 5′-TT CCTCTGTGTTTTCCCAGATT-3′, R 5′-GTCACCAAGG ATGCTATCAACA-3′; Wnt10b, F 5′-GCTTCTCCAAACT CCTCCACTA-3′, R 5′-AAACCTTTCCTTTGGAGAGAC C-3′; fzd5, F 5′-catcttcaccctgctctacacg-3′, R 5′-TAC}TTGA GCATGAGCACCCAGT-3′; fzd4, F 5′-TTGTGCTATGTT GGGAACCA-3′, R 5′-GACCCCGATCTTGACCATTA-3′; β2m, F 5′-GAGAATGGGAAGCCGAACATAC-3′, R 5′-CATGTCTCGATCCCAGTAGACG-3′; mGAPDH, F 5′-C TCAACTACATGGTCTACATGTTCCA-3′, R 5′-CCATTC TCGGCCTTGACTGT-3′.

RT2 qPCR Primer Assay for Mouse sets for STAT3-regulated genes, Socs1 (PPM05151A-200), Myc (PPM029 24E-200), Bcl2l1 (PPM02920E-200), Ccnd1 (PPM0290 3E-200), Cdkn1a (PPM02901A-200), Irf1 (PPM03203B-200), Mmp3 (PPM03673A-200), and Fas (PPM03705A-200) were designed by SABiosciences (Qiagen).

Profiling of STAT3 targets

The Oncomine database, version 4.4 (http://www.oncomine.org), was queried to assess gene expression levels in normal and cancer tissues. Oncomine was used for analysis and visualization.

Knockdown of Wnt5a in JB6-transformed RT101 and Ras-transformed HaCaT-II4 cells

RT101 cells and HaCaT-II4 cells were infected with MISSION® shRNA Lentiviral Transduction Particles for Wnt5a, Non-Target shRNA control, or pLKO.1-puro control transduction particles (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and selected in medium containing 2 µg/mL puromycin.

Transformed phenotype assay

JB6-transformed RT101 and Ras-transformed HaCaT-II4 cells expressing shRNA targeted to Wnt5a or control were used to assess anchorage-independent growth by soft agar assay. Cells were incubated for 14 days on 0.4% agar medium over 0.6% agar in a 24-well plate. The total colonies per well were counted using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD) after samples were scanned by Gelcount, (Oxford Optronix Ltd., Oxford, UK). Colonies measuring 0.7 mm or greater in diameter were scored. Results are expressed as the number of cells per well forming colonies.

Xenograft growth of shWnt5a knockdown HaCaT-II4 cells

Female SCID mice were used in all studies and were obtained from the Animal Production Area (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). Mice were maintained in a dedicated specific pathogen-free environment and used at 6 weeks of age. Ten mice per group were injected subcutaneous into each flank with 2 × 106 HaCaT-II4 cells transduced with shWnt5a or control shRNA-expressing vectors. Tumor volume was measured 3 times a week using a caliper. Data were statistically compared using a paired t test. Animal care was provided in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health Publication No. 86-23 [1985]).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Terry Yamaguchi and Alan Perantoni for valuable comments on the project and the article. They also thank members of the Gene Regulation Section, Laboratory of Cancer Prevention, National Cancer Institute for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Supplementary material for this article is available on the Genes & Cancer website at http://ganc.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- 1. Shaulian E, Karin M. AP-1 in cell proliferation and survival. Oncogene. 2001;20:2390-400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown PH, Chen TK, Birrer MJ. Mechanism of action of a dominant-negative mutant of c-Jun. Oncogene. 1994;9:791-9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dong Z, Birrer MJ, Watts RG, Matrisian LM, Colburn NH. Blocking of tumor promoter-induced AP-1 activity inhibits induced transformation in JB6 mouse epidermal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:609-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dong Z, Crawford HC, Lavrovsky V, et al. A dominant negative mutant of Jun blocking 12-0-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced invasion in mouse keratinocytes. Mol Carcinog. 1997;19: 204-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cooper S, Young MR, Colburn N, Bowden GT. Expression of dominant negative c-jun inhibits UVB-induced squamous cell carcinoma number and size in an SKH-1 hairless mouse model. Mole Cancer Res. 2003;1:848-54 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Young MR, Farrell L, Lambert PF, Awasthi P, Colburn NH. Protection against human papillomavirus type 16-E7 oncogene-induced tumorigenesis by in vivo expression of dominant-negative c-jun. Mol Carcinog. 2002;34:72-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Young MR, Li JJ, Rincon M, et al. Transgenic mice demonstrate AP-1 (activator protein-1) transactivation is required for tumor promotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:9827-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shen Q, Uray IP, Li Y, et al. Targeting the AP-1 transcription factor for the prevention of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative mammary tumors. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;1:45-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tichelaar JW, Yan Y, Tan Q, et al. A dominant-negative c-jun mutant inhibits lung carcinogenesis in mice. Cancer Prev Res. 2010;3: 1148-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hilberg F, Aguzzi A, Howells N, Wagner EF. c-jun is essential for normal mouse development and hepatogenesis. Nature. 1993;365: 179-81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matthews CP, Birkholz AM, Baker AR, et al. Dominant-negative activator protein 1 (TAM67) targets cyclooxygenase-2 and osteopontin under conditions in which it specifically inhibits tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2430-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wei Q, Jiang H, Matthews CP, Colburn NH. Sulfiredoxin is an AP-1 target gene that is required for transformation and shows elevated expression in human skin malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19738-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gregorieff A, Clevers H. Wnt signaling in the intestinal epithelium: from endoderm to cancer. Genes Dev. 2005;19:877-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Polakis P. Wnt signaling and cancer. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1837-51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ilyas M. Wnt signalling and the mechanistic basis of tumour development. J Pathol. 2005;205:130-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Angers S, Moon RT. Proximal events in Wnt signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:468-77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuhl M, Sheldahl LC, Park M, Miller JR, Moon RT. The Wnt/Ca2+ pathway: a new vertebrate Wnt signaling pathway takes shape. Trends Genet. 2000;16:279-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nishita M, Itsukushima S, Nomachi A, et al. Ror2/Frizzled complex mediates Wnt5a-induced AP-1 activation by regulating Dishevelled polymerization. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:3610-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sheldahl LC, Park M, Malbon CC, Moon RT. Protein kinase C is differentially stimulated by Wnt and Frizzled homologs in a G-protein-dependent manner. Curr Biol. 1999;9:695-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sheldahl LC, Slusarski DC, Pandur P, Miller JR, Kuhl M, Moon RT. Dishevelled activates Ca2+ flux, PKC, and CamKII in vertebrate embryos. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:769-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Enomoto M, Hayakawa S, Itsukushima S, et al. Autonomous regulation of osteosarcoma cell invasiveness by Wnt5a/Ror2 signaling. Oncogene. 2009;28:3197-208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kurayoshi M, Oue N, Yamamoto H, et al. Expression of Wnt-5a is correlated with aggressiveness of gastric cancer by stimulating cell migration and invasion. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10439-48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pukrop T, Klemm F, Hagemann T, et al. Wnt 5a signaling is critical for macrophage-induced invasion of breast cancer cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5454-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ripka S, Konig A, Buchholz M, et al. WNT5A: target of CUTL1 and potent modulator of tumor cell migration and invasion in pancreatic cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1178-87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Topol L, Jiang X, Choi H, Garrett-Beal L, Carolan PJ, Yang Y. Wnt-5a inhibits the canonical Wnt pathway by promoting GSK-3-independent beta-catenin degradation. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:899-908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dhar A, Hu J, Reeves R, Resar LM, Colburn NH. Dominant-negative c-Jun (TAM67) target genes: HMGA1 is required for tumor promoter-induced transformation. Oncogene. 2004;23:4466-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen W, ten Berge D, Brown J, et al. Dishevelled 2 recruits beta-arrestin 2 to mediate Wnt5A-stimulated endocytosis of Frizzled 4. Science. 2003;301:1391-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. He F, Xiong W, Yu X, et al. Wnt5a regulates directional cell migration and cell proliferation via Ror2-mediated noncanonical pathway in mammalian palate development. Development. 2008;135:3871-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Colburn NH, Wendel EJ, Abruzzo G. Dissociation of mitogenesis and late-stage promotion of tumor cell phenotype by phorbol esters: mitogen-resistant variants are sensitive to promotion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:6912-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dong Z, Lavrovsky V, Colburn NH. Transformation reversion induced in JB6 RT101 cells by AP-1 inhibitors. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:749-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Takahashi K, Heine UI, Junker JL, Colburn NH, Rice JM. Role of cytoskeleton changes and expression of the H-ras oncogene during promotion of neoplastic transformation in mouse epidermal JB6 cells. Cancer Res. 1986;46:5923-32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nishita M, Enomoto M, Yamagata K, Minami Y. Cell/tissue-tropic functions of Wnt5a signaling in normal and cancer cells. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:346-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dissanayake SK, Olkhanud PB, O’Connell MP, et al. Wnt5A regulates expression of tumor-associated antigens in melanoma via changes in signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 phosphorylation. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10205-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chan KS, Sano S, Kiguchi K, et al. Disruption of Stat3 reveals a critical role in both the initiation and the promotion stages of epithelial carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:720-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim DJ, Angel JM, Sano S, DiGiovanni J. Constitutive activation and targeted disruption of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) in mouse epidermis reveal its critical role in UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2009;28:950-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sano S, Chan KS, Carbajal S, et al. Stat3 links activated keratinocytes and immunocytes required for development of psoriasis in a novel transgenic mouse model. Nat Med. 2005;11:43-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Darnell JE, Jr., Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264:1415-21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wen Z, Darnell JE., Jr. Mapping of Stat3 serine phosphorylation to a single residue (727) and evidence that serine phosphorylation has no influence on DNA binding of Stat1 and Stat3. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2062-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee JM, Kim IS, Kim H, et al. RORalpha attenuates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling by PKCalpha-dependent phosphorylation in colon cancer. Mol Cell. 2010;37:183-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dissanayake SK, Wade M, Johnson CE, et al. The Wnt5A/protein kinase C pathway mediates motility in melanoma cells via the inhibition of metastasis suppressors and initiation of an epithelial to mesenchymal transition. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17259-71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Weeraratna AT, Jiang Y, Hostetter G, et al. Wnt5a signaling directly affects cell motility and invasion of metastatic melanoma. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:279-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Singh N, Aggarwal S. The effect of active oxygen generated by xanthine/xanthine oxidase on genes and signal transduction in mouse epidermal JB6 cells. Int J Cancer. 1995;62:107-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Garcia-Bermejo ML, Leskow FC, Fujii T, et al. Diacylglycerol (DAG)-lactones, a new class of protein kinase C (PKC) agonists, induce apoptosis in LNCaP prostate cancer cells by selective activation of PKCalpha. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:645-55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Boukamp P, Stanbridge EJ, Foo DY, Cerutti PA, Fusenig NE. c-Ha-ras oncogene expression in immortalized human keratinocytes (HaCaT) alters growth potential in vivo but lacks correlation with malignancy. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2840-7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chen W, Borchers AH, Dong Z, Powell MB, Bowden GT. UVB irradiation-induced activator protein-1 activation correlates with increased c-fos gene expression in a human keratinocyte cell line. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32176-81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ren Q, Kari C, Quadros MR, et al. Malignant transformation of immortalized HaCaT keratinocytes through deregulated nuclear factor kappaB signaling. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5209-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nindl I, Dang C, Forschner T, et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma by microarray expression profiling. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Riker AI, Enkemann SA, Fodstad O, et al. The gene expression profiles of primary and metastatic melanoma yields a transition point of tumor progression and metastasis. BMC Med Genomics. 2008;1:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sun L, Hui AM, Su Q, et al. Neuronal and glioma-derived stem cell factor induces angiogenesis within the brain. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:287-300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lee J, Kotliarova S, Kotliarov Y, et al. Tumor stem cells derived from glioblastomas cultured in bFGF and EGF more closely mirror the phenotype and genotype of primary tumors than do serum-cultured cell lines. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:391-403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Skrzypczak M, Goryca K, Rubel T, et al. Modeling oncogenic signaling in colon tumors by multidirectional analyses of microarray data directed for maximization of analytical reliability. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bhattacharjee A, Richards WG, Staunton J, et al. Classification of human lung carcinomas by mRNA expression profiling reveals distinct adenocarcinoma subclasses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13790-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jenei V, Sherwood V, Howlin J, et al. A t-butyloxycarbonyl-modified Wnt5a-derived hexapeptide functions as a potent antagonist of Wnt5a-dependent melanoma cell invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:19473-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yamamoto H, Oue N, Sato A, et al. Wnt5a signaling is involved in the aggressiveness of prostate cancer and expression of metalloproteinase. Oncogene. 2010;29:2036-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jonsson M, Dejmek J, Bendahl PO, Andersson T. Loss of Wnt-5a protein is associated with early relapse in invasive ductal breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2002;62:409-16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. O’Connell MP, Fiori JL, Xu M, et al. The orphan tyrosine kinase receptor, ROR2, mediates Wnt5A signaling in metastatic melanoma. Oncogene. 2010;29:34-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Grivennikov SI, Karin M. Dangerous liaisons: STAT3 and NF-kappaB collaboration and crosstalk in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:11-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Arnott CH, Scott KA, Moore RJ, et al. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha mediates tumour promotion via a PKC alpha- and AP-1-dependent pathway. Oncogene. 2002;21:4728-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jansen AP, Dreckschmidt NE, Verwiebe EG, Wheeler DL, Oberley TD, Verma AK. Relation of the induction of epidermal ornithine decarboxylase and hyperplasia to the different skin tumor-promotion susceptibilities of protein kinase C alpha, -delta and -epsilon transgenic mice. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:635-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kim DJ, Tremblay ML, Digiovanni J. Protein tyrosine phosphatases, TC-PTP, SHP1, and SHP2, cooperate in rapid dephosphorylation of Stat3 in keratinocytes following UVB irradiation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Simek SL, Kligman D, Patel J, Colburn NH. Differential expression of an 80-kDa protein kinase C substrate in preneoplastic and neoplastic mouse JB6 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:7410-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sun Y, Hegamyer G, Colburn NH. Molecular cloning of five messenger RNAs differentially expressed in preneoplastic or neoplastic JB6 mouse epidermal cells: one is homologous to human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1139-44 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sun Y, Pommier Y, Colburn NH. Acquisition of a growth-inhibitory response to phorbol ester involves DNA damage. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1907-15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Huang C, Ma WY, Young MR, Colburn N, Dong Z. Shortage of mitogen-activated protein kinase is responsible for resistance to AP-1 transactivation and transformation in mouse JB6 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:156-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bernstein LR, Colburn NH. AP1/jun function is differentially induced in promotion-sensitive and resistant JB6 cells. Science. 1989;244: 566-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lavrovsky V, Dong Z, Ma WY, Colburn N. Drug-induced reversion of progression phenotype is accompanied by reversion of AP-1 phenotype in JB6 cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1996;32:234-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rozen S, Skaletsky HJ. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. In: Krawetz S, Misener S, editors. Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2000:365-386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]