Abstract

Adenosine acts as a cytoprotective modulator in response to stress to an organ or tissue. Although short-lived in the circulation, it can activate four sub-types of G protein-coupled adenosine receptors (ARs): A1, A2A, A2B, and A3. The alkylxanthines caffeine and theophylline are the prototypical antagonists of ARs, and their stimulant actions occur primarily through this mechanism. For each of the four AR subtypes, selective agonists and antagonists have been introduced and used to develop new therapeutic drug concepts. ARs are notable among the GPCR family in the number and variety of agonist therapeutic candidates that have been proposed. The selective and potent synthetic AR agonists, which are typically much longer lasting in the body than adenosine, have potential therapeutic applications based on their anti-inflammatory (A2A and A3), cardioprotective (preconditioning by A1 and A3 and postconditioning by A2B), cerebroprotective (A1 and A3), and antinociceptive (A1) properties. Potent and selective AR antagonists display therapeutic potential as kidney protective (A1), antifibrotic (A2A), neuroprotective (A2A), and antiglaucoma (A3) agents. AR agonists for cardiac imaging and positron-emitting AR antagonists are in development for diagnostic applications. Allosteric modulators of A1 and A3 ARs have been described. In addition to the use of selective agonists/antagonists as pharmacological tools, mouse strains in which an AR has been genetically deleted have aided in developing novel drug concepts based on the modulation of ARs.

Keywords: Adenosine receptors, G protein-coupled receptors, Purines, Nucleosides, Imaging, Allosteric modulation, Agonists, Antagonists

1 Introduction

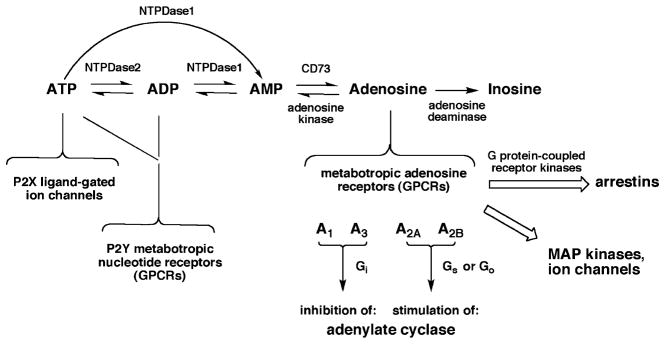

Extracellular adenosine acts as a cytoprotective modulator, under both physiological and pathophysiological conditions, in response to stress to an organ or tissue (Fredholm et al. 2001; Haskó et al. 2008; Jacobson and Gao 2006). This protective response might take the form of increased blood supply (vasodilation or angiogenesis) (Ryzhov et al. 2008), ischemic preconditioning (in the heart, brain, or skeletal muscle) (Akaiwa et al. 2006; Cohen and Downey 2008; Liang and Jacobson 1998; Zheng et al. 2007), and/or suppression of inflammation (activation and infiltration of inflammatory cells, production of cytokines and free radicals) (Chen et al. 2006b; Martin et al. 2006; Ohta and Sitkovsky 2001). Adenosine acts on cell surface receptors that are coupled to intracellular signaling cascades. There are four subtypes of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs); i.e., four distinct sequences of adenosine receptors (ARs) termed A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 (Fig. 1). The second messengers associated with the ARs are historically defined with respect to the adenylate cyclase system (Fredholm and Jacobson 2009). The A1 and A3 receptors inhibit the production of cyclic AMP through coupling to Gi. The A2A and A2B subtypes are coupled to Gs or Go to stimulate adenylate cyclase. Furthermore, the A2B subtype, which has the lowest affinity (Ki > 1 μM) of all the subtypes for native adenosine, is also coupled to Gq (Ryzhov et al. 2006). Adenosine has the highest affinity at the A1 and A2A ARs (Ki values in binding of 10–30 nM at the high affinity sites), and the affinity of adenosine at the A3AR is intermediate (ca. 1 μM at the rat A3AR) (Jacobson et al. 1995).

Fig. 1.

Interconversion of extracellular adenine nucleotides and adenosine and their associated signaling pathways. These molecules may originate from intracellular sources. For example, adenosine may cross the plasma membrane through an equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT)1. The four subtypes of adenosine receptors (ARs) are grouped according to effects on adenylate cyclase. Inosine at micromolar concentrations also activates the A3AR. Various extracellular nucleotides activate seven subtypes of P2X receptors and eight subtypes of P2Y, which are not specified here. The ARs and P2Y receptors are G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), while the P2X receptors are ionotropic receptors. The ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases NT-PDase1 and NTPDase2 are also known as CD39 (apyrase) and CD39L1, respectively. NTPDases3 and 8 (not shown) are also involved in breakdown of extracellular nucleotides

Effector mechanisms other than the adenylate cyclase and phospholipase C are associated with the stimulation of ARs. For example, adenosine action can activate phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), and extracellular receptor signal-induced kinase (ERK) (Schulte and Fredholm 2003). The indirect regulation by adenosine of MAPKs can have effects on differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis (Che et al. 2007; Fredholm et al. 2001; Jacobson and Gao 2006; Schulte and Fredholm 2003). Thus, the A3AR activates Akt to inhibit apoptosis. These actions may be initiated through the β, γ subunits of the G proteins, which can also lead to the coupling of ARs to ion channels. The influx of calcium ions or the efflux of potassium ions can be induced by the activation of the A1AR. The arrestin pathway, which has the dual role of signal transmission and downregulation of the receptor, is also activated by ARs (Klaasse et al. 2008; Penn et al. 2001). The A2AAR forms a tight complex with Gs by a process described as “restricted collision coupling” (Zezula and Freissmuth 2008). The A2AAR also binds to additional “accessory” proteins, such as alpha-actinin, ARNO, USP4 and translin-associated protein-X (Zezula and Freissmuth 2008).

Adenosine suppresses various cytotoxic processes, such as cytokine-induced apoptosis. In the brain, both neuronal and glial cell functions are regulated by adenosine (Björklund et al. 2008; Fredholm et al. 2005). Adenosine acts as a local modulator of the action of various other neurotransmitters, including bio-genic amines and excitatory amino acids. Adenosine attenuates the release of many stimulatory neurotransmitters and can counteract the excitotoxicity associated with excessive glutamate release in the brain. Adenosine can also modulate the interaction of neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, with their own receptors. In the periphery, adenosine has been shown to attenuate excessive inflammation, to promote wound healing, and to protect tissue against ischemic damage (Chen et al. 2006a; Haskó et al. 2008). In the cardiovascular system, adenosine promotes vasodilation, vascular integrity, and angiogenesis, and also counteracts the lethal effects of prolonged ischemia on cardiac myocytes and skeletal muscle (Cohen and Downey 2008; Zheng et al. 2007).

Therapeutic applications, both in the central nervous system and in the periphery, are being explored for selective AR agonists and antagonists. A large body of medicinal chemistry has been created around the four AR subtypes, such that selective agonists and antagonists are now available for each. These ligands have been used as pharmacological probes to introduce many new drug concepts. Mouse strains in which an AR has been genetically deleted (each of the subtypes has now been deleted) have also been useful in developing novel drug concepts based on the modulation of ARs (Fredholm et al. 2005).

Adenosine itself is short-lived in the circulation, which has allowed its clinical use in the treatment of paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia and in radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging (Cerqueira 2006). The many selective and potent synthetic AR agonists, which are typically much longer lasting in the body than adenosine, have been slower to enter a clinical pathway than adenosine. Recently, the first such synthetic adenosine agonist, Lexiscan (regadenoson, CV Therapeutics, Palo Alto, CA, USA), an A2AAR agonist, was approved for diagnostic use (Lieu et al. 2007).

Synthetic adenosine agonists have potential therapeutic applications based on their anti-inflammatory (A2A and A3) (Haskó et al. 2008; Ohta and Sitkovsky 2001), cardioprotective (preconditioning of the ischemic heart muscle by activation of the A1 and A3 ARs and its postconditioning by A2BAR activation) (Cohen and Downey 2008), cerebroprotective (A1 and A3) (Chen et al. 2006a; Knutsen et al. 1999; von Lubitz et al. 1994), and antinociceptive (A1) (Johansson et al. 2001) properties. Potent and selective AR antagonists display therapeutic potential as kidney protective (A1) (Gottlieb et al. 2002), antifibrotic (A2A) (Che et al. 2007), neuroprotective (A2A) (Yu et al. 2004), antiasthmatic (A2B) (Holgate 2005), and antiglaucoma (A3) (Yang et al. 2005) agents. A3AR agonists have been proposed for the treatment of a wide range of autoimmune inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, psoriasis, etc. (Guzman et al. 2006; Kolachala et al. 2008; Madi et al. 2007), and also for cardiac and brain ischemia. A1AR agonists are useful in preclinical models of cardiac arrythmia and ischemia and in pain. Adenosine agonists are also of interest for the treatment of sleep disorders (Porkka-Heiskanen et al. 1997). Activation of the A2BAR protects against vascular injury (Yang et al. 2008).

The alkylxanthines caffeine and theophylline are the prototypical antagonists of ARs, and their stimulant actions are produced primarily through blocking the depressant actions of adenosine through the A1 and A2A ARs (Fredholm and Jacobson 2009). Prior to the work of Rall, Daly, and other pioneers in the field, the stimulant actions of the alkylxanthines were thought to occur as a result of inhibition of phosphodiesterases. It is true that caffeine inhibits phosphodiesterases and has other actions, such as stimulation of calcium release, but these non-AR-mediated actions require higher concentrations of caffeine than are typically ingested in the human diet (Fredholm and Jacobson 2009).

The nonselective AR antagonist theophylline has been in use as an antiasthmatic drug (Holgate 2005), although its use is now limited as a result of side effects on the central nervous system and the renal system. Adenosine antagonists of various selectivities remain of interest as potential drugs for treating asthma (Wilson 2008). A large number of synthetic AR antagonists that are much more potent and selective than the prototypical alkylxanthines have been introduced, although none have yet been approved for clinical use. For example, AR antagonists have been proposed for neurodegenerative diseases (such as Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease) (Schwarzschild et al. 2006), although a well-advanced A2AAR antagonist KW6002 (Istradefylline) (8-[(E)-2-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)vinyl]-1,3-diethyl-7-methylpurine-2,6-dione, Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) was recently denied FDA approval for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease (LeWitt et al. 2008).

2 Sources and Fate of Extracellular Adenosine

Adenosine is not a classical neurotransmitter because it is not principally produced and released vesicularly in response to neuronal firing. Most tissues in the body and cells in culture release adenosine to the extracellular medium, from where it can feed back and act as an autocoid on the ARs present locally. The basal levels of extracellular adenosine have been estimated as roughly 100 nM in the heart and 20 nM in the brain, which would only partially activate the ARs present (Fredholm et al. 2005). In the case of severe ischemic stress, the levels can rapidly rise to the micro-molar range, which would cause a more intense and generalized activation of the four subtypes of ARs. Nevertheless, it is thought that the exogenous administration of highly potent and selective AR agonists in such cases of severe ischemic challenge might still provide additional benefit beyond that offered by the endogenous adenosine generated (Jacobson and Gao 2006; Yan et al. 2003).

Extracellular adenosine may arise from intracellular adenosine or from the breakdown of the adenine nucleotides, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP), outside the cell (Fig. 1). Adenosine, which is present in a higher concentration inside than outside the cell, does not freely diffuse across the cell membrane. There are nucleoside transporters, such as the equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT), ENT1, which bring it to the extracellular space. Extracellular nucleotides activate their own receptors, known as P2Y metabotropic and P2X inotropic receptors (Burnstock 2008). Extracellular nucleotides may also originate from cytosolic sources, including by vesicular release exocytosis, passage through channels, and cell lysis. Ectonucleotidases break down the adenine nucleotides in stages to produce free extracellular adenosine at the terminal step (Zimmermann 2000). For example, the extracellular enzyme ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (E-NTPDase1) converts ATP and adenosine diphosphate (ADP) to adenosine monophosphate (AMP). A related ectonucleotidase, E-NTPDase2, primarily hydrolyzes 5′-triphosphates to 5′-diphosphates. The final and critical step, with respect to AR activation, of conversion of AMP to adenosine is carried out by ecto-5′-nucleotidase, also known as CD73. Overexpression of CD73 has been proposed to protect organs under stress by the formation of cytoprotective adenosine (Beldi et al. 2008). The adenosine produced extracellularly is also subject to metabolic breakdown by adenosine deaminase to produce inosine or (re)phosphorylation by adenosine kinase to produce AMP. Therefore, when an organ is under stress there is a highly complex and time-dependent interplay of the activation of many receptors in the same vicinity. In addition to the direct activation of ARs by selective agonists or their blockade by selective antagonists, inhibition of the metabolic or transport pathways surrounding adenosine is also being explored for therapeutic purposes (McGaraughty et al. 2005).

3 Adenosine Receptor Structure

The ARs, as GPCRs, share the structural motif of a single polypeptide chain forming seven transmembrane helices (TMs), with the N-terminus being extracellular and the C-terminus being cytosolic (Costanzi et al. 2007). These helices, consisting of 25–30 amino acid residues each, are connected by six loops, i.e., three intracellular (IL) and three extracellular (EL) loops. The extracellular regions contain sites for posttranslational modifications, such as glycosylation. The A1 and A3 ARs also contain sites for palmitoylation in the C-terminal domain. The A2AAR has a long C-terminal segment of more than 120 amino acid residues, which is not required for coupling to Gs, but can serve as a binding site for “accessory” proteins (Zezula and Freissmuth 2008). The sequence identity between the human A1 and A3 ARs is 49%, and the human A2A and A2B ARs are 59% identical. Particular conserved residues point to specific functions. For example, there are two characteristic His residues in TMs 6 and 7 of the A1, A2A, and A2B ARs. In the A3AR, the His residue in TM6 is lacking but another His residue has appeared at a new location in TM3. All of these His residues have been indicated by mutagenesis to be important in the recognition and/or activation function of the receptor (Costanzi et al. 2007; Kim et al. 2003).

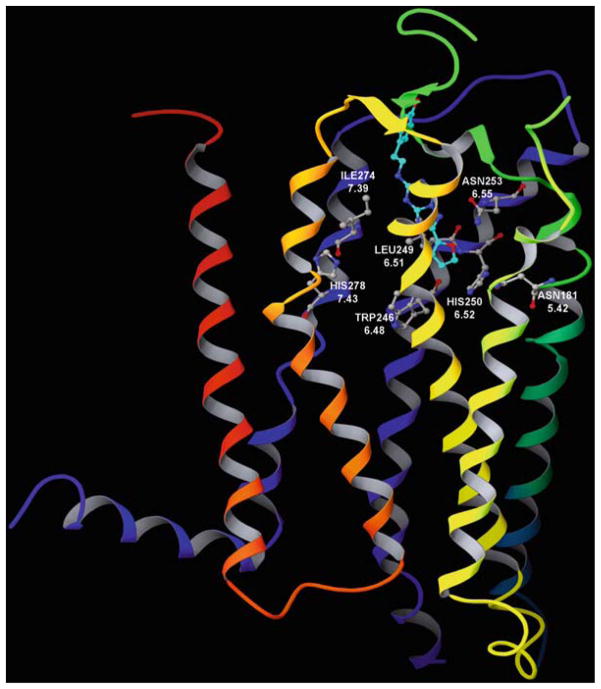

Recently, the human A2AAR joined the shortlist of GPCRs for which an X-ray crystallographic structure has been determined (Jaakola et al. 2008). The reported structure (Fig. 2) contained a bound high-affinity antagonist ligand, ZM241385 (4-2-[7-amino-2-(2-furyl)-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-yl-amino]ethylphenol), which is moderately selective for the A2AAR. Prior to this dramatic step in bringing ARs into the age of structural biology, homology modeling of the ARs, based on a rhodopsin template, was the principal means of AR structural prediction and was useful in interpreting mutagenesis data. The modeling has defined two subregions within the putative agonist binding site (Costanzi et al. 2007; Kim et al. 2003). This putative binding site is located within the barrel or cleft created by five of the seven TMs (excluding TM1 and TM2), approximately one-third of the distance across the membrane from the exofacial side. The ribose moiety of adenosine binds in a hydrophilic region defined by TMs 3 and 7, and the adenine moiety binds in a largely hydrophobic region surrounded by TMs 5 and 6. Thus, the region of adenosine in the binding site is approximately the same as the position of the retinal in rhodopsin. Even the importance of the Lys residue in TM7 of rhodopsin that forms the covalent association (Schiff base) with retinal is conserved by analogy in the ARs, i.e., with a His residue that occurs at the same position (7.43) in all of the ARs. The His residue is predicted by molecular modeling to associate with the ribose moiety of adenosine. Features of the putative binding site of adenosine have been reviewed recently (Costanzi et al. 2007). Different labs have not been in agreement on the precise placement of the adenosine moiety when docked in the receptor. However, the major modeling publications in this area have zeroed in on the same limited region of the receptor structure for coordination of adenosine. One can consider the modeling approach to provide insights that are subject to refinement over time, as more is learned from mutagenesis studies and the modeling templates and computational methods are refined (Ivanov et al. 2009). Many amino acid residues predicted by molecular modeling to be involved in the coordination of antagonists by the A2AAR were indeed in proximity to the bound ZM241385 in the X-ray structure, although the molecule was somewhat rotated from the orientation predicted in various docking models. These residues include Asn253 in TM6, which hydrogen bonds to the exocyclic NH of agonists and various antagonists in the AR models. The same residue was found to form a hydrogen bond with the exocyclic NH of ZM241385.

Fig. 2.

X-ray crystallographic structure of the human A2A adenosine receptor (AR), showing the bound antagonist ZM241385 (Jaakola et al. 2008). The structure of the A2AAR is colored by region: N-terminus and transmembrane helical (TM) domain 1 in orange, TM2 in ochre, TM3 in yellow, TM4 in green, TM5 in cyan, TM6 in blue, TM7 and C-terminus in purple. The p-hydroxyphenylethyl moiety of the antagonist ligand points toward the exofacial side of the receptor

Dimerization has been proposed to occur between ARs, leading to homo- or heterodimers (Franco et al. 2006). Dimerization between ARs and other receptors has also been proposed; for example, A1AR/D1 dopamine receptor dimers and A2AAR/D2 dopamine receptor dimers (Franco et al. 2006). Heterodimers of the A1AR with either P2Y1 or P2Y2 nucleotide receptors or with metabotropic glutamate receptors have been detected (Prinster et al. 2005). The pharmacological properties of these heterodimers may differ dramatically from the properties of each monomer alone. For example, the A1AR/P2Y1 dimers have been characterized pharmacologically and were found to be inhibited by known nucleotide antagonists but not activated by known nucleotide agonists of the P2Y1 receptor (Nakata et al. 2005). Dimers of A2A adenosine/D2 dopamine receptors are present in striatum and display a modified pharmacology relative to each of the individual subtypes. These receptor dimers are drug development targets for Parkinson’s disease (Schwarzschild et al. 2006).

4 Regulation of Adenosine Receptors

Similar to the function and regulation of other GPCRs, both activation and desensitization of the ARs occur after agonist binding. Interaction of the activated ARs with the G proteins leads to second messenger generation and classical physiological responses. Interaction of the activated ARs with G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) leads to their phosphorylation. Downregulation of ARs should be considered in both the basic pharmacological studies and with respect to the possible therapeutic application of agonists. AR responses desensitize rapidly, and this phenomenon is associated with receptor downregulation, internalization and degradation. The internalization and desensitization of ARs has been reviewed recently (Klaasse et al. 2008). Mutagenesis has been applied to analyze the molecular basis for the differences in the kinetics of the desensitization response displayed by various AR subtypes. The most rapid downregulation among the AR subtypes is generally seen with the A3AR, due to phosphorylation by GRKs. The A2AAR is only slowly desensitized and internalized as a result of agonist activation.

5 Adenosine Receptor Agonists and Antagonists in Preclinical and Clinical Trials

Potent and selective AR agonists and antagonists have been synthesized for all four AR subtypes, with selective A2BAR agonists being the most recently reported (Baraldi et al. 2009). Some of these ligands are selective for a single AR subtype, and others have mixed selectivity for several subtypes. Thus, numerous pharmacological tools for studying the ARs are available, and some of these compounds have advanced to clinical studies (Baraldi et al. 2008; Elzein and Zablocki 2008; Giorgi and Nieri 2008; Moro et al. 2006).

A general caveat in the design of selective agonists and antagonists is the frequent observation of a variation of affinity for a given compound at the same subtype in different species. There are many examples of marked species dependence of ligand affinity at the ARs (Jacobson and Gao 2006; Yang et al. 2005). Therefore, caution must be used in generalizing the selectivity of a given compound from one species to another. In general, one must be cognizant of potential species differences for both AR agonists and antagonists.

5.1 Adenosine Receptor Agonists

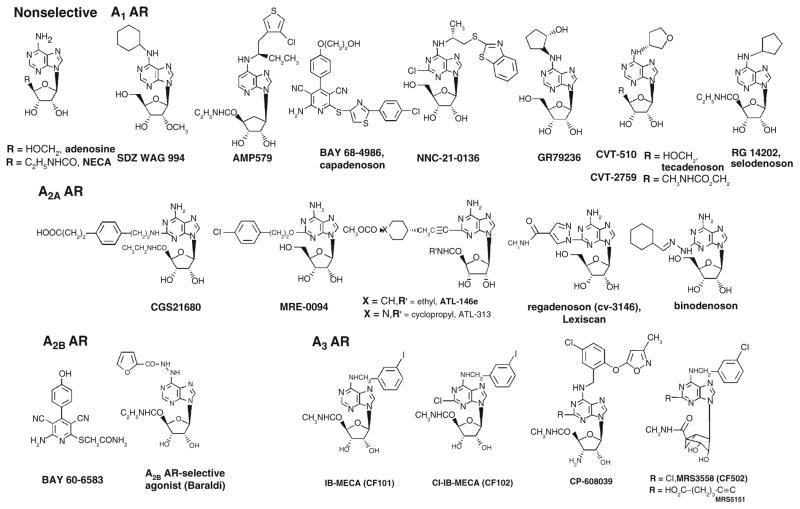

Nearly all AR agonists reported are adenosine derivatives. A noteworthy exception is the class of pyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile derivatives that fully activate ARs and that display varied selectivity at the AR subtypes (Beukers et al. 2004). One such compound is the A2BAR-selective agonist BAY 60–6583 (2-[6-amino-3,5-dicyano-4-[4-(cyclopropylmethoxy)phenyl]pyridin-2-ylsulfanyl]acetamide) (Cohen and Downey 2008; Eckle et al. 2007). Another AR agonist of nonnucleoside structure is BAY 68–4986 (Capadenoson), which is a selective A1AR agonist in clinical trials for the oral treatment of stable angina pectoris (Mittendorf and Wuppertal 2008). The structure–activity relationships (SARs) of adenosine derivatives as agonists of the ARs have been thoroughly probed (Jacobson and Gao 2006; Yan et al. 2003), and representative agonists are shown in Fig. 3. In general, substitution at the N6 position with certain alkyl, cycloalkyl, and arylalkyl groups increases selectivity for the A1AR. Substitution with an N 6-benzyl group or substituted benzyl group increases selectivity for the A3AR. Substitution at the 2 position, especially with ethers, secondary amines, and alkynes, often results in high selectivity for the A2AAR.

Fig. 3.

Structures of selected adenosine receptor (AR) agonists. Ki values in binding are available in references (Baraldi et al. 2008; Jacobson and Gao 2006; Yan et al. 2003)

All of the A1AR agonists shown in Fig. 3 contain a characteristic N6 modification. The singly substituted A1AR agonists NNC-21-0136 (2-chloro-N6-[(R)-[(2-benzothiazolyl)thio]-2-propyl]-adenosine) and GR79236 (N 6-[(1S, 2S)-2-hydroxycyclopentyl]adenosine) (Merkel et al. 1995) and the doubly substituted selodenoson have been clinical candidates. NNC-21-0136 was the result of a program to develop CNS-selective AR agonists for use in treating stroke and other neurodegenerative conditions (Knutsen et al. 1999). A1AR agonists are of interest for use in treating cardiac arrhythmias [for which adenosine itself, under the name Adenocard (Astellas Pharma, Inc., Tokyo, Japan), is in widespread use]. The A1AR agonist SDZ WAG94 (2′-O-methyl-N 6-cyclohexyladenosine) was under consideration for treatment of diabetes (Ishikawa et al. 1998). The AR agonist of mixed selectivity AMP579 ([1S-[1α, 2β, 3β, 4α(S*)]]-4-[7-[[1-[(3-chlorothien-2-yl)methyl]propyl]amino]-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyrid-3-yl] N-ethyl-2,3-dihydroxycyclopentanecarboxamide) has cardioprotective properties (Cohen and Downey 2008). The 2-substituted A2AAR agonists ATL-146e (4-{3-[6-amino-9-(5-ethylcarbamoyl-3,4-dihydroxy-tetrahydro-furan-2-yl)-9H-purin-2-yl]-prop-2-ynyl}-cyclohexanecarboxylic acid methyl ester), binodenoson (2-[{cyclohexylmethylene}hydrazino]adenosine, MRE-0470 or WRC-0470), and MRE0094 (2-[2-(4-chlorophenyl)ethoxy]adenosine) have been cardiovascular clinical candidates (Awad et al. 2006; Desai et al. 2005; Udelson et al. 2004). Several of the A2AAR agonists shown in Fig. 3 contain the 5′-uronamide modification, characteristic of NECA; others have the adenosine-like CH2OH group. Such agonists are of interest for use as vasodilatory agents in cardiac imaging [adenosine itself, under the name Adenoscan (Astellas Pharma, Inc., Tokyo, Japan), is in use for this purpose] and in suppressing inflammation (Cerqueira 2006). CVT-3146 (1-[6-amino-9-[(2R, 3R, 4S, 5R)-3,4-dihydroxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)oxolan-2-yl]purin-2-yl]-N-methylpyrazole-4-carboxamide, Lexiscan, regadenoson) is already approved for diagnostic imaging (Lieu et al. 2007).

All of the A3AR agonists shown in Fig. 3 contain the NECA-like 5′-uronamide modification and have nanomolar affinity at the receptor. CP-608,039 ((2S, 3S, 4R, 5R)-3-amino-5-{6-[5-chloro-2-(3-methylisoxazol-5-ylmethoxy)benzylamino]purin-9-yl-l-4-hydroxytetrahydrofuran-2-carboxylic acid methylamide) and its N 6-(2,5-dichlorobenzyl) analog CP-532,903 ((2S, 3S, 4R, 5R)-3-amino-5-{6-[2, 5-dichlorobenzylamino]purin- 9-yl-l-4-hydroxytetrahydrofuran-2-carboxylic acid methylamide) (Wan et al. 2008) (not shown) are selective A3 agonists that were developed for cardioprotection. CF101 (N 6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine, IB-MECA) is being studied by Can-Fite Biopharma (Petah-Tikva, Israel) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (Phase IIb), dry eye syndrome (Phase II) and psoriasis (Phase II) (http://clinicaltrials.gov). Can-Fite Biopharma is also developing the A3AR agonist CF102 (2-chloro-N 6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine, Cl-IB-MECA) for the treatment of liver conditions, including liver cancer, hepatitis infections and liver tissue regeneration (Bar-Yehuda et al. 2008; Madi et al. 2004). The North conformation of the ribose ring was found to be the preferred conformation at the A3AR, which accounts for the high potency and selectivity of the rigid analog MRS3558 ((1′ S, 2′ R, 3′ S, 4′ R, 5′ S)-4′-{2-chloro-6-[(3-chlorophenylmethyl)amino]purin-9-yl}-1-(methylaminocarbonyl)bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-2,3-diol) at the human and rat A3ARs (Ochaion et al. 2008). The bicyclic ring constrains the ribose-like moiety in the desired conformation. The recent generation agonist in the same chemical series MRS5151 ((1′ S, 2′ R, 3′ S, 4′ R, 5′ S)-4′-[6-(3-chlorobenzylamino)-2-(5-hydroxycarbonyl-1-pentynyl)-9-yl ]-2′, 3′-dihydroxybicyclo [3.1.0] hexane-1′-carboxylic acid N-methylamide) is designed to be A3AR selective in at least three different species, including mouse (Melman et al. 2008a).

Recently, macromolecular conjugates (e.g., dendrimers) of chemically functionalized AR agonists were introduced as potent polyvalent activators of the receptors that are qualitatively different in pharmacological characteristics in comparison to the monomeric agonists (Kim et al. 2008; Klutz et al. 2008). The feasibility of using dendrimer conjugates to bind to AR dimers was studied using a molecular modeling approach (Ivanov and Jacobson 2008).

5.2 Adenosine Receptor Antagonists

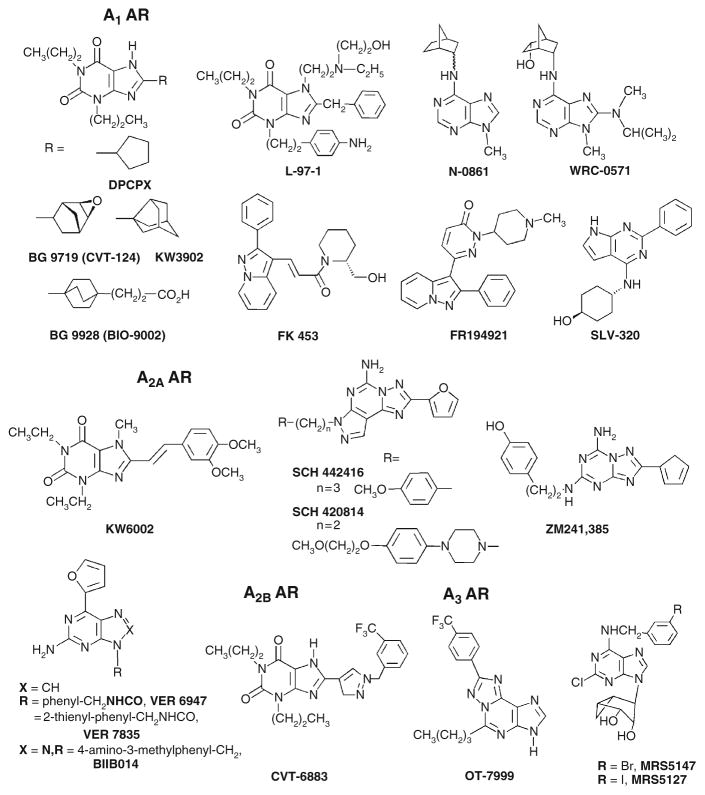

The newer and most selective AR antagonists are more chemically diverse than the classical 1,3-dialkylxanthines, which have been used pharmacologically as antagonists of the A1 and A2 ARs. A range of AR antagonists and their synthetic methods were recently reviewed (Baraldi et al. 2008; Moro et al. 2006).

Purine AR antagonists, including both xanthine and adenine derivatives, have provided a wide range of receptor subtype selectivity, depending on the substitution (Fig. 4). In general, modifications of the xanthine scaffold at the 8 position with aryl or cycloalkyl groups has led to high affinity and selectivity for the A1AR. Highly selective xanthine antagonists of the A1AR (e.g., the epoxide derivative BG 9719 (1,3-dipropyl-8-(2-(5,6-epoxy)norbornyl)xanthine) and the more water soluble BG9928 (3-[4-(2,6-dioxo-1,3-dipropyl-2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-1H-purin-8-yl)-bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-1-yl]-propionic acid, Biogen Idec, Cambridge, MA, USA), as well as KW3902 (8-(noradamantan-3-yl)-1,3-dipropylxanthine, Merck and Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA) have been (BG 9719) (Gottlieb et al. 2002) or are currently (BG9928 and KW3902) (Cotter et al. 2008; Dittrich et al. 2007; Givertz et al. 2007; Greenberg et al. 2007) in clinical trials for treatment of acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) with renal impairment. In dogs, both BG9719 and BG9928 have high affinity for both the A1AR and A2BAR (Auchampach et al. 2004) with A2B/A1 ratios of 21 and 24, respectively (Doggrell 2005). The selectivity of BG 9928 for the human A1AR compared to the human A2BAR is 12 (Kiesman et al. 2006). The 8-cyclopentyl derivative DPCPX (8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine), also known as CPX, which is selective for the A1AR in the rat with nanomolar affinity but less selective at the human AR subtypes, has been in clinical trials for cystic fibrosis through a non-AR-related mechanism (Arispe et al. 1998). The highly selective A1AR antagonist L-97-1 (3-[2-(4-aminophenyl)-ethyl]-8-benzyl-7-{2-ethyl - (2-hydroxy-ethyl)-amino]-ethyl}-1-propyl-3,7-dihydro-purine-2,6-dione, Endacea Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC, USA) is water soluble and in late preclinical development for the treatment of asthma (Wilson 2008). As in the cases of DPCPX, BG 9719, N-0861 ((±)-N 6-endonorbornan-2-yl-9-methyladenine), and others, a persistent problem in the development of A1AR antagonists is low aqueous solubility, e.g., high lipophilicity, corresponding low water solubility, and low bioavailability (Hess 2001); thus, A1AR antagonists, e.g., BG 9928 and L-97-1, with good water solubility are preferable clinical candidates. Moreover, a persistent problem in the use of xanthine derivatives as AR antagonists is their interaction at the A2BAR. Modification of xanthines at the 8 position with certain aryl groups has given rise to preclinical candidates that are selective for the A2BAR (e.g., CVT-6883, 3-ethyl-1-propyl-8-[1-(3-trifluoromethylbenzyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]-3,7-dihydropurine-2,6-dione, CV Therapeutics, Palo Alto, CA, USA) (Mustafa et al. 2007). Use of the adenine derivatives WRC-0571 (8-(N-methylisopropyl)amino-N 6-(5′-endohydroxy-endonorbornan-2-yl-9-methyladenine) as an inverse agonist at the A1AR provides A1AR selective antagonism without blocking the A2BAR (Martin et al. 1996). Nonxanthine antagonists of the A1AR have also been shown to have high receptor subtype selectivity, e.g., FK453 (Terai et al. 1995) and SLV 320 (4-[(2-phenyl-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-yl)amino]-trans-cyclohexanol, Solvay Pharmaceuticals SA, Brussels, Belgium) (Hocher et al. 2008). Moreover, various nonxanthine A1AR antagonists have been or are currently being explored for clinical applications (Jacobson and Gao 2006). For example, SLV 320 is in clinical trials as an intravenous treatment for ADHF with renal impairment (http://clinicaltrials.gov).

Fig. 4.

Structures of selected adenosine receptor (AR) antagonists. Ki values in binding are available in references (Baraldi et al. 2008; Jacobson and Gao 2006)

Modification of xanthines at the 8 position with alkenes (specifically styryl groups) has led to selectivity for the A2AAR. Such derivatives include the A2AAR antagonist KW6002 (istradefylline), which has been in clinical trials. Some 8-styrylxanthine derivatives, such as CSC (8-(3-chlorostyryl)caffeine), have been discovered to inhibit monoamine oxidase-B, as well as the A2AAR (Vlok et al. 2006). The triazolotriazine ZM241385 and the pyrazolotriazolopyrimidine SCH 442416 (5-amino-7-(3-(4-methoxy)phenylpropyl)-2-(2-furyl)pyrazolo[4,3-e]-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidine) are highly potent A2AAR antagonists (Moresco et al. 2005; Palmer et al. 1996). ZM241385 also binds to the human A2BAR with moderate affinity, and has been used as a radioligand at that subtype (Ji and Jacobson 1999). SCH 442416 displays > 23, 000-fold selectivity for the human A2AAR (Ki 0.048 nM) in comparison to human A1AR and an IC50 > 10 μM at the A2B and A3 ARs. A2AAR antagonists, such as the xanthine KW6002 and the nonxanthines SCH 442416, VER 6947 (2-amino-N-benzyl-6-(furan-2-yl)-9H-purine-9-carboxamide), and VER 7835 (2-amino-6-(furan-2-yl)-N-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-9H-purine-9-carboxamide), are of interest for use in treating Parkinson’s disease (Gillespie et al. 2008; LeWitt et al. 2008; Schwarzschild et al. 2006). The A2AAR antagonist BIIB014 (V2006) has begun Phase II clinical trials (Biogen Idec, Cambridge, MA, USA, in partnership with Vernalis, Cambridge, UK) for Parkinson’s disease (Jordan 2008).

Cyclized derivatives of xanthines, such as PSB-11 (8-ethyl-4-methyl-2-phenyl-(8R)-4,5,7,8-tetrahydro-1H imidazo[2.1-i]purin-5-one), are A3AR-selective, and similar compounds have been explored by Kyowa Hakko. Selective A3AR antagonists, such as the heterocyclic derivatives OT-7999 (5-n-butyl-8-(4-trifluoromethylphenyl)-3H-[1,2,4]triazolo-[5,1-i]purine), are being studied for the treatment of glaucoma (Okamura et al. 2004), and other such antagonists are under consideration for treatment of cancer, stroke, and inflammation (Gessi et al. 2008; Jacobson and Gao 2006). MRS5147 ((1′R, 2′R, 3′S, 4′R, 5′S)-4′-[2-chloro-6-(3-bromobenzylamino)-purine]-2′, 3′-O-dihydroxybicyclo-[3.1.0]hexane) and its 3-iodo analog MRS5127 are highly selective A3AR antagonists in both human and rat, based on a conformationally constrained ribose-like ring that is truncated at the 5′ position (Melman et al. 2008b). No selective A3AR antagonists have yet reached human trials. However, an antagonist of mixed A2B/A3AR selectivity in the class of 5-heterocycle-substituted aminothiazoles from Novartis (Horsham, UK), QAF 805 (Press et al. 2005), was in a Phase Ib clinical trial for the treatment of asthma. This antagonist failed to decrease sensitivity to the bronchoconstrictive effects of AMP in asthmatics (Pascoe et al. 2007).

5.3 Radioligands for In Vivo Imaging

With the established relevance of ARs to human disease states, it has been deemed useful to develop high-affinity imaging ligands for these receptors, for eventual diagnostic use in the CNS and in the periphery. Ligands for in vivo positron emission tomographic (PET) imaging of A1, A2A, and A3 ARs have been developed. For example, the xanthine [18F]CPFPX (8-cyclopentyl-1-propyl-3-(3-fluoropropyl)-xanthine, similar in structure to DPCPX) and the nonxanthine [11C]FR194921 (2-(1-methyl-4-piperidinyl)-6-(2-phenylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyridin-3-yl)-3(2H )-pyridazinone) have been developed as centrally-active PET tracers for imaging of the A1AR in the brain (Bauer et al. 2005). The first PET ligand for the A2AAR was [7-methyl-11C]-(E)-8-(3,4,5-trimethoxystyryl)-1,3,7-trimethylxanthine ([11C]TMSX) (Ishiwata et al. 2000). This is a caffeine analog related to the series of KW6002, introduced by the Kyowa Hakko. 5-Amino-7-(3-(4-[11C]methoxy)phenylpropyl)-2-(2-furyl)pyrazolo[4,3-e]-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidine ([11C]SCH442416) has recently been explored as a PET agent in the noninvasive in vivo imaging of the human A2AAR (Moresco et al. 2005). [11C]SCH442416 displays an extremely high affinity at the human A2AAR (Ki 0.048 nM). Recently, an A3AR PET ligand, [F-18]FE@SUPPY (5-(2-fluoroethyl) 2,4-diethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate), based on a series of pyridine A3AR antagonists, was introduced (Wadsak et al. 2008). Several nucleoside derivatives that bind with nanomolar affinity at the A3AR and that contain 76Br for PET imaging were recently reported, including the antagonist MRS5147 (Kiesewetter et al. 2008).

6 Allosteric Modulation of Adenosine Receptors

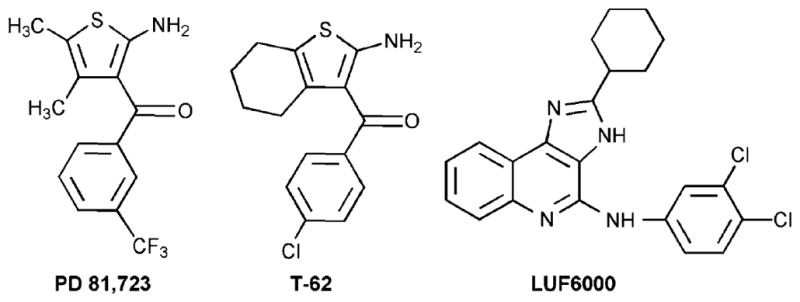

In addition to directly acting AR agonists and antagonists, allosteric modulators of A1 and A3 ARs have been introduced (Gao et al. 2005). Allosteric modulators have advantages over the directly acting (orthosteric) receptor ligands in that they would magnify the effect of the native adenosine released in response to stress at a specific site or tissue and, in theory, would not induce a biological effect in the absence of an agonist. Various allosteric enhancers of the activation of ARs by agonists are under consideration as clinical candidates. The benzoylthiophenes, represented by PD-81,723 (Fig. 5), were the first AR allosteric modulators to be identified. A structurally related benzoylthiophene derivative known as T-62 ((2-amino-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrobenzo[b]thiophen-3-yl)-(4-chlorophenyl)-methanone), which acts as a selective positive enhancer of the A1AR, like PD-81,723 (2-amino-4,5-dimethyl-3-thienyl-[3-trifluoromethylphenyl]methanone), had progressed toward clinical trials for neuropathic pain (Li et al. 2004). LUF6000 (N-(3,4-dichloro-phenyl)-2-cyclohexyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-4-amine) is a selective positive enhancer of the human A3AR (Gao et al. 2008).

Fig. 5.

Allosteric modulators of adenosine receptors (ARs)

7 Genetic Deletion of Adenosine Receptors

Deletion of each of the four AR subtypes has been carried out, and the resulting single-AR knockout (KO) mice are viable and not highly impaired in function (Fredholm et al. 2005; Yang et al. 2008). The pharmacological profile indicates that the analgesic effect of adenosine is mediated by the A1AR, and analgesia is lost in mice in which the A1AR has been genetically eliminated. Genetic KO of the A1AR in mice removes the discriminative-stimulus effects but not the arousal effect of caffeine and increases anxiety and hyperalgesia. Study of A2AAR KO mice reveals functional interaction between the spinal opioid receptors and peripheral ARs. A1AR KO mice demonstrate a decreased thermal pain threshold, whereas A2AAR null mice demonstrate an increased threshold to noxious heat stimulation, supporting an A1AR-mediated inhibitory and an A2AAR-mediated excitatory effect on pain transduction pathways. KO of the A2AAR eliminates the arousal effect of caffeine. Genetic KO of the A2AAR also suggests a link to increased anxiety and protected against damaging effects of ischemia and the striatal toxin 3-nitropropionic acid. Genetic KO of the A3AR leads to increased neuronal damage in a model of carbon monoxide-induced brain injury. Neutrophils lacking A3ARs show correct directionality but diminished speed of chemotaxis (Chen et al. 2006b). Although studies on A2BAR KO mice have been reported (Yang et al. 2008), the importance of A2BAR in the brain still awaits future investigation.

8 Conclusions

In conclusion, adenosine is released in response to organ stress or tissue damage and displays cytoprotective effects, in general, both in the brain and in the periphery. When excessive activity occurs in a given organ, adenosine acts as an endogenous quieting substance, to either reduce the energy demand or increase the energy supply to that organ. Nearly every cell type in the body expresses one or more of the AR subtypes, which indicates the central role of this feedback system in protecting organs and tissues and in tissue regeneration. Thus, a common theme to the therapeutic applications proposed for agonists is that adenosine acts as a cytoprotective modulator in response to stress to an organ or tissue.

Selective agonists and antagonists have been introduced and used to develop new therapeutic drug concepts. ARs are notable among the GPCR family in terms of the number and variety of agonist drug candidates that have been proposed. Thus, this has led to new experimental agents based on anti-inflammatory (A2A and A3), cardioprotective (preconditioning by A1 and A3 and postconditioning by A2B), cerebroprotective (A1 and A3), and antinociceptive (A1) effects. Potent and selective AR antagonists display therapeutic potential as kidney-protective (A1), antifibrotic (A2A), neuroprotective (A2A), and antiglaucoma (A3) agents. Adenosine agonists for cardiac imaging and positron-emitting adenosine antagonists are in development for diagnostic use. Allosteric modulation of A1 and A3 ARs has been demonstrated. In addition to selective agonists/antagonists, mouse strains in which an AR has been genetically deleted have been useful in developing novel drug concepts based on modulation of ARs.

Acknowledgments

Support from the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases is gratefully acknowledged. Dr. Andrei A. Ivanov, NIDDK, prepared the image shown in Fig. 2. Dr. Zhang-Guo Gao and Dr. Dale Kiesewetter are acknowledged for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- ADHF

Acute decompensated heart failure

- ADP

Adenosine diphosphate

- AMP

Adenosine 5′-monophosphate

- AMP579

[1S-[1α, 2β, 3β, 4α(S*)]]-4-[7-[[1-[(3-Chlorothien-2-yl)methyl] propyl]amino]-3H-imidazo[4,5-b]pyrid-3-yl]-N-ethyl 2,3-dihydroxycyclopentanecarboxamide

- AR

Adenosine receptor

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

- BAY 60–6583

2-[6-Amino-3,5-dicyano-4-[4-(cyclopropylmethoxy)phenyl] pyridin-2-ylsulfanyl]acetamide

- BAY 68–4986

6-Amino-2-(2-(4-chlorophenyl)thiazol-4-ylthio)-4-(4-(2-hydroxyethoxy)phenyl)-5-isocyanonicotinonitrile

- BG9719

1,3-Dipropyl-8-(2-(5,6-epoxy)norbornyl)xanthine

- BG9928

3-[4-(2,6-Dioxo-1,3-dipropyl-2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-1H-purin-8-yl)-bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-1-yl]-propionic acid

- BIIB014

3-(4-Amino-3-methylbenzyl)-7-(2-furyl)-3H-[1,2,3]triazolo [4,5-d]pyrimidine-5-amine (V2006)

- CD39

Apyrase

- CD73

Ecto-5′-nucleotidase

- CF101

N6-(3-Iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine (IB-MECA)

- CF102

2-Chloro-N 6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine (Cl-IB-MECA)

- CP-608,039

(2S, 3S, 4R, 5R)-3-Amino-5-{6-[5-chloro-2-(3-methylisoxazol-5-ylmethoxy)benzylamino]purin-9-yl-l-4-hydroxytetrahydrofuran-2-carboxylic acid methylamide

- CP-532,903

(2S, 3S, 4R, 5R)-3-Amino-5-{6-[2,5-dichlorobenzylamino]purin-9-yl-l-4-hydroxytetrahydrofuran-2-carboxylic acid methylamide

- CPFPX

8-Cyclopentyl-1-propyl-3-(3-fluoropropyl)-xanthine

- CVT-3146

1-[6-Amino-9-[(2R, 3R, 4S, 5R)-3,4-dihydroxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)oxolan-2-yl]purin-2-yl]-N-methylpyrazole-4-carboxamide

- CVT-6883

3-Ethyl-1-propyl-8-[1-(3-trifluoromethylbenzyl)-1H-pyrazol-4-yl]-3,7-dihydropurine-2,6-dione

- EL

Extracellular loop

- ENT

Equilibrative nucleoside transporter

- E-NTPDase

Ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase

- ERK

Extracellular receptor signal-induced kinase

- FK 453

(+)-(R)-(1-(E)-3-(2-Phenylpyrazolo(1,5-a)pyridin-3-yl)acryl)-2-piperidine ethanol

- FR194921

2-(1-Methyl-4-piperidinyl)-6-(2-phenylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyridin-3-yl)-3(2H )-pyridazinone

- GPCRs

G protein-coupled receptors

- GR79236

N 6-[(1S, 2S)-2-Hydroxycyclopentyl]adenosine

- GRKs

G-protein-coupled receptor kinases

- IL

Intracellular loop

- KW3902

8-(Noradamantan-3-yl)-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- KW6002

8-[(E)-2-(3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl)vinyl]-1,3-diethyl-7-methylpurine-2,6-dione

- L-97-1

3-[2-(4-Aminophenyl)-ethyl]-8-benzyl-7-{2-ethyl-(2-hydroxy-ethyl)-amino]-ethyl}-1-propyl-3,7-dihydro-purine-2,6-dione

- MAP

Mitogen-activated protein

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinases

- MRE0094

2-[2-(4-Chlorophenyl)ethoxy]adenosine

- MRE-0470

2-[{Cyclohexylmethylene}hydrazino]adenosine (WRC-0470, binodenoson)

- MRS5147

(1′R, 2′R, 3′S, 4′R, 5′S)-4′-[2-Chloro-6-(3-bromobenzylamino)-purine]-2′, 3′-O-dihydroxybicyclo-[3.1.0]hexane

- N-0861

(±)-N 6-Endonorbornan-2-yl-9-methyladenine

- NNC-21-0136

2-Chloro-N 6-[(R)-[(2-benzothiazolyl)thio]-2-propyl]-adenosine

- OT-7999

5-N-Butyl-8-(4-trifluoromethylphenyl)-3H-[1,2,4]triazolo-[5, 1-i]purine

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- PI3K

Phosphoinositide-3 kinase

- T-62

(2-Amino-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrobenzo[b]thiophen-3-yl)-(4-chlorophenyl)-methanone

- SLV-320

4-[(2-Phenyl-7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-yl)amino]-trans-cyclohexanol

- SDZ WAG94

N 6-Cyclohexyl-2′-O-methyl-adenosine

- TM

Transmembrane helix

- VER6947

2-Amino-N-benzyl-6-(furan-2-yl)-9H-purine-9-carboxamide

- VER7835

2-Amino-6-(furan-2-yl)-N-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)-9H-purine-9-carboxamide

- V2006

see BIIB014

- WRC-0571

8-(N-Methylisopropyl)amino-N 6-(5′-endohydroxy-endonorbornan-2-yl-9-methyladenine

- ZM241385

4-2-[7-Amino-2-(2-furyl)-1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-a][1,3,5]triazin-5-yl-amino]ethylphenol

References

- Akaiwa K, Akashi H, Harada H, Sakashita H, Hiromatsu S, Kano T, Aoyagi S. Moderate cerebral venous congestion induces rapid cerebral protection via adenosine A1 receptor activation. Brain Res. 2006;1122:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arispe N, Ma J, Jacobson KA, Pollard HB. Direct activation of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) channels by CPX and DAX. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5727–5734. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchampach JA, Jin X, Moore J, Wan TC, Kreckler LM, Ge ZD, Narayanan J, Whalley E, Kiesman W, Ticho B, Smits G, Gross GJ. Comparison of three different A1 adenosine receptor antagonists on infarct size and multiple cycle ischemic preconditioning in anesthetized dogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:846–856. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.057943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad AS, Huang L, Ye H, Duong ET, Bolton WK, Linden J, Okusa MD. Adenosine A2A receptor activation attenuates inflammation and injury in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F828–F837. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00310.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraldi PG, Tabrizi MA, Gessi S, Borea PA. Adenosine receptor antagonists: translating medicinal chemistry and pharmacology into clinical utility. Chem Rev. 2008;108:238–263. doi: 10.1021/cr0682195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraldi PG, Tabrizi MA, Fruttarolo F, Romagnoli R, Preti D. Recent improvements in the development of A2B adenosine receptor agonists. Purinergic Signal. 2009;4(4):287–303. doi: 10.1007/s11302-008-9097-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yehuda S, Stemmer SM, Madi L, Castel D, Ochaion A, Cohen S, Barer F, Zabutti A, Perez-Liz G, Del Valle L, Fishman P. The A3 adenosine receptor agonist CF102 induces apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma via de-regulation of the Wnt and NF-kappaB signal transduction pathways. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A, Langen KJ, Bidmon H, Holschbach MH, Weber S, Olsson RA, Coenen HH, Zilles K. 18F-CPFPX PET identifies changes in cerebral A1 adenosine receptor density caused by glioma invasion. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:450–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beldi G, Wu Y, Sun X, Imai M, Enjyoji K, Csizmadia E, Candinas D, Erb L, Robson SC. Regulated catalysis of extracellular nucleotides by vascular CD39/ENTPD1 is required for liver regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1751–1760. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukers MW, Chang LC, von Frijtag Drabbe Künzel JK, Mulder-Krieger T, Spanjersberg RF, Brussee J, IJzerman AP. New, non-adenosine, high-potency agonists for the human adenosine A2B receptor with an improved selectivity profile compared to the reference agonist N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3707–3709. doi: 10.1021/jm049947s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björklund O, Shang M, Tonazzini I, Daré E, Fredholm BB. Adenosine A1 and A3 receptors protect astrocytes from hypoxic damage. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;596:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling and disorders of the central nervous system. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:575–590. doi: 10.1038/nrd2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerqueira MD. Advances in pharmacologic agents in imaging: new A2A receptor agonists. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2006;8:119–122. doi: 10.1007/s11886-006-0022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che J, Chan ES, Cronstein BN. Adenosine A2A receptor occupancy stimulates collagen expression by hepatic stellate cells via pathways involving protein kinase A, Src, and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 signaling cascade or p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1626–1636. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.038760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GJ, Harvey BK, Shen H, Chou J, Victor A, Wang Y. Activation of adenosine A3 receptors reduces ischemic brain injury in rodents. J Neurosci Res. 2006a;84:1848–1855. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, Nizet V, Insel PA, Junger WG. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006b;314:1792–1795. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MV, Downey JM. Adenosine: trigger and mediator of cardioprotection. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103:203–215. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0687-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzi S, Ivanov AA, Tikhonova IG, Jacobson KA. Structure and function of G protein-coupled receptors studied using sequence analysis, molecular modeling, and receptor engineering: adenosine receptors. Front Drug Design Disc. 2007;3:63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cotter G, Dittrich HC, Weatherley BD, Bloomfield DM, O’Connor CM, Metra M, Massie BM PROTECT Steering Committee, Investigators, and Coordinators . The PROTECT pilot study: a randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-finding study of the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist rolofylline in patients with acute heart failure and renal impairment. J Cardiac Fail. 2008;14:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Victor-Vega C, Gadangi S, Montesinos MC, Chu CC, Cronstein B. Adenosine A2A receptor stimulation increases angiogenesis by down-regulating production of the antiangiogenic matrix protein thrombospondin 1. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:1406–1413. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.007807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich HC, Gupta DK, Hack TC, Dowling T, Callahan J, Thomson S. The effect of KW-3902, an adenosine A1 receptor antagonist, on renal function and renal plasma flow in ambulatory patients with heart failure and renal impairment. J Card Failure. 2007;13:609–617. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doggrell SA. BG-9928 (Biogen Idec) Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;6:962–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckle T, Krahn T, Grenz A, Köhler D, Mittelbronn M, Ledent C, Jacobson MA, Osswald H, Thompson LF, Unertl K, Eltzschig HK. Cardioprotection by ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) and A2B adenosine receptors. Circulation. 2007;115:1581–1590. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.669697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elzein E, Zablocki J. A1 adenosine receptor agonists and their potential therapeutic applications. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:1901–1910. doi: 10.1517/13543780802497284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco R, Casadó V, Mallol J, Ferrada C, Ferré S, Fuxe K, Cortés A, Ciruela F, Lluis C, Canela EI. The two-state dimer receptor model: a general model for receptor dimers. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1905–1912. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.020685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Jacobson KA. John W. Daly and the early characterization of adenosine receptors. Heterocycles. 2009;79:73–83. doi: 10.3987/COM-08-S(D)Memoire-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Chen JF, Masino SA, Vaugeois JM. Actions of adenosine at its receptors in the CNS: insights from knockouts and drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:385–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao ZG, Kim SK, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA. Allosteric modulation of the adenosine family of receptors. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2005;5:545–553. doi: 10.2174/1389557054023242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao ZG, Ye K, Göblyös A, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA. Flexible modulation of agonist efficacy at the human A3 adenosine receptor by an imidazoquinoline allosteric enhancer LUF6000 and its analogues. BMC Pharmacol. 2008;8:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-8-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessi S, Merighi S, Varani K, Leung E, Mac Lennan S, Borea PA. The A3 adenosine receptor: an enigmatic player in cell biology. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;117:123–140. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie RJ, Cliffe IA, Dawson CE, Dourish CT, Gaur S, Jordan AM, Knight AR, Lerpiniere J, Misra A, Pratt RM, Roffey J, Stratton GC, Upton R, Weiss SM, Williamson DS. Antagonists of the human adenosine A2A receptor. Part 3: Design and synthesis of pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidines, pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines and 6-arylpurines. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;18:2924–2929. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi I, Nieri P. Therapeutic potential of A1 adenosine receptor ligands: a survey of recent patent literature. Expert Opin Ther Patents. 2008;18:677–691. [Google Scholar]

- Givertz MM, Massie BM, Fields TK, Pearson LL, Dittrich HC. The effect of KW-3902, an adenosine A1-receptor antagonist, on diuresis and renal function in patients with acute decompensated heart failure and renal impairment or diuretic resistance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1551–1560. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb SS, Brater DC, Thomas I, Havranek E, Bourge R, Goldman S, Dyer F, Gomez M, Bennett D, Ticho B, Beckman E, Abraham WT. BG9719 (CVT-124), an A1 adenosine receptor antagonist, protects against the decline in renal function observed with diuretic therapy. Circulation. 2002;105:1348–1353. doi: 10.1161/hc1102.105264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg B, Ignatius T, Banish D, Goldman S, Havranek E, Massie BM, Zhu Y, Ticho B, Abraham WT. Effects of multiple oral doses of an A1 adenosine receptor antagonist, BG 9928, in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:600–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman J, Yu JG, Suntres Z, Bozarov A, Cooke H, Javed N, Auer H, Palatini J, Hassanain HH, Cardounel AJ, Javed A, Grants I, Wunderlich JE, Christofi FL. ADOA3R as a therapeutic target in experimental colitis: proof by validated high-density oligonucleotide microarray analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:766–789. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200608000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskó G, Linden J, Cronstein B, Pacher P. Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:759–770. doi: 10.1038/nrd2638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess S. Recent advances in adenosine receptor antagonist research. Expert Opin Ther Patents. 2001;11:1533–1561. [Google Scholar]

- Hocher B, Fischer Y, Witte K, Ziegler D. US Patent Appl 20080027082 Use of adenosine A1 antagonists in radiocontrast media induced nephropathy. 2008

- Holgate ST. The identification of the adenosine A2B receptor as a novel therapeutic target in asthma. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;145:1009–1015. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa J, Mitani H, Bandoh T, Kimura M, Totsuka T, Hayashi S. Hypoglycemic and hypotensive effects of 6-cyclohexyl-2′-O-methyl-adenosine, an adenosine A1 receptor agonist, in spontaneously hypertensive rat complicated with hyperglycemia. Diab Res Clin Pract. 1998;39:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(97)00116-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwata K, Noguchi J, Wakabayashi S, Shimada J, Ogi N, Nariai T, Tanaka A, Endo K, Suzuki F, Senda M. 11C-labeled KF18446: a potential central nervous system adenosine A2A receptor ligand. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:345–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov AA, Jacobson KA. Molecular modeling of a PAMAM-CGS21680 dendrimer bound to an A2A adenosine receptor homodimer. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:4312–4315. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.06.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov AA, Baak D, Jacobson KA. Evaluation of homology modeling of G protein-coupled receptors in light of the A2A adenosine receptor crystallographic structure. J Med Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1021/jm801533x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaakola VP, Griffith MT, Hanson MA, Cherezov V, Chien EYT, Lane JR, IJzerman JR, Stevens RC. The 2.6 Angstrom crystal structure of a human A2A adenosine receptor bound to an antagonist. Science. 2008;322(5905):1211–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.1164772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Disc. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Kim HO, Siddiqi SM, Olah ME, Stiles GL, von Lubitz DKJE. A3 adenosine receptors: design of selective ligands and therapeutic prospects. Drugs Future. 1995;20:689–699. doi: 10.1358/dof.1995.020.07.531583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji XD, Jacobson KA. Use of the triazolotriazine [3H]ZM 241385 as a radioligand at recombinant human A2B adenosine receptors. Drug Des Discov. 1999;16:217–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson B, Halldner L, Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA, Poelchen W, Giménez-Llort L, Escorihuela RM, Fernández-Teruel A, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Xu XJ, Hårdemark A, Betsholtz C, Herlenius E, Fredholm BB. Hyperalgesia, anxiety, and decreased hypoxic neuroprotection in mice lacking the adenosine A1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9407–9412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161292398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan AM. Science and serendipity: discovery of novel, orally bioavailable adenosine A2A antagonists for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Abstract MEDI-015, 236th ACS National Meeting; Philadelphia, PA. 17–21 Aug 2008.2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kiesewetter DO, Lang L, Ma Y, Bhattacharjee AK, Gao ZG, Joshi BV, Melman A, Castro S, Jacobson KA. Synthesis and characterization of [76Br]-labeled high affinity A3 adenosine receptor ligands for positron emission tomography. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;36:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesman WF, Zhao J, Conlon PR, Dowling JE, Petter RC, Lutterodt F, Jin X, Smits G, Fure M, Jayaraj A, Kim J, Sullivan GW, Linden J. Potent and orally bioavailable 8-bicyclo[2.2.2]octylxanthines as adenosine A1 receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2006;49:7119–7131. doi: 10.1021/jm0605381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Gao ZG, Van Rompaey P, Gross AS, Chen A, Van Calenbergh S, Jacobson KA. Modeling the adenosine receptors: comparison of binding domains of A2A agonist and antagonist. J Med Chem. 2003;46:4847–4859. doi: 10.1021/jm0300431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Hechler B, Klutz A, Gachet C, Jacobson KA. Toward multivalent signaling across G protein-coupled receptors from poly(amidoamine) dendrimers. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008;19:406–411. doi: 10.1021/bc700327u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaasse EC, IJzerman AP, de Grip WJ, Beukers MW. Internalization and desensitization of adenosine receptors. Purinergic Signal. 2008;4:21–37. doi: 10.1007/s11302-007-9086-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klutz AM, Gao ZG, Lloyd J, Shainberg A, Jacobson KA. Enhanced A3 adenosine receptor selectivity of multivalent nucleoside-dendrimer conjugates. J Nanobiotechnol. 2008;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-3155-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutsen LJ, Lau J, Petersen H, Thomsen C, Weis JU, Shalmi M, Judge ME, Hansen AJ, Sheardown MJ. N-Substituted adenosines as novel neuroprotective A1 agonists with diminished hypotensive effects. J Med Chem. 1999;42:3463–3477. doi: 10.1021/jm960682u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolachala VL, Bajaj R, Chalasani M, Sitaraman SV. Purinergic receptors in gastrointestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G401–G410. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00454.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeWitt PA, Guttman M, Tetrud JW, Tuite PJ, Mori A, Chaikin P, Sussman NM. Adenosine A2A receptor antagonist istradefylline (KW-6002) reduces “off” time in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomized, multicenter clinical trial (6002-US-005) Ann Neurol. 2008;63:295–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.21315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Bantel C, Conklin D, Childers SR, Eisenach JC. Repeated dosing with oral allosteric modulator of adenosine A1 receptor produces tolerance in rats with neuropathic pain. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:956–961. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200404000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang BT, Jacobson KA. A physiological role of the adenosine A3 receptor: sustained cardioprotection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6995–6999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieu HD, Shryock JC, von Mering GO, Gordi T, Blackburn B, Olmsted AW, Belardinelli L, Kerensky RA. Regadenoson, a selective A2A adenosine receptor agonist, causes dose-dependent increases in coronary blood flow velocity in humans. J Nucl Cardiol. 2007;14:514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.nuclcard.2007.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madi L, Ochaion A, Rath-Wolfson L, Bar-Yehuda S, Erlanger A, Ohana G, Harish A, Merimski O, Barer F, Fishman P. The A3 adenosine receptor is highly expressed in tumor versus normal cells: potential target for tumor growth inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4472–4479. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madi L, Cohen S, Ochayin A, Bar-Yehuda S, Barer F, Fishman P. Overexpression of A3 adenosine receptor in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in rheumatoid arthritis: involvement of nuclear factor-kappa B in mediating receptor level. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PL, Wysocki RJ, Jr, Barrett RJ, May JM, Linden J. Characterization of 8-(N-methylisopropyl)amino-N 6-(5′-endohydroxy-endonorbornyl)-9-methyladenine (WRC-0571), a highly potent and selective, non-xanthine antagonist of A1 adenosine receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:490–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L, Pingle SC, Hallam DM, Rybak LP, Ramkumar V. Activation of the adenosine A3 receptor in RAW 264.7 cells inhibits lipopolysaccharide-stimulated tumor necrosis factor-alpha release by reducing calcium-dependent activation of nuclear factor-kappaB and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:71–78. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaraughty S, Cowart M, Jarvis MF, Berman RF. Anticonvulsant and antinociceptive actions of novel adenosine kinase inhibitors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5:43–58. doi: 10.2174/1568026053386845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melman A, Gao ZG, Kumar D, Wan TC, Gizewski E, Auchampach JA, Jacobson KA. Design of (N )-methanocarba adenosine 5′-uronamides as species-independent A3 receptor-selective agonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008a;18:2813–2819. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melman A, Wang B, Joshi BV, Gao ZG, de Castro S, Heller CL, Kim SK, Jeong LS, Jacobson KA. Selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonists derived from nucleosides containing a bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane ring system. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008b;16:8546–8556. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkel LA, Hawkins ED, Colussi DJ, Greenland BD, Smits GJ, Perrone MH, Cox BF. Cardiovascular and antilipolytic effects of the adenosine agonist GR 79236. Pharmacology. 1995;51:224–236. doi: 10.1159/000139364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittendorf J, Wuppertal D. BAY 68–4986 (Capadenoson): the first non-purinergic adenosine A1 agonist for the oral treatment of stable angina pectoris. Fachgruppe Medizinische Chemie Annual Meeting; Regensburg, Germany. 2–5 March 2008; 2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moresco RM, Todde S, Belloli S, Simonelli P, Panzacchi A, Rigamonti M, Galli-Kienle M, Fazio F. In vivo imaging of adenosine A2A receptors in rat and primate brain using [11C]SCH442416. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imag. 2005;32:405–413. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro S, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA, Spalluto G. Progress in pursuit of therapeutic adenosine receptor antagonists. Med Res Rev. 2006;26:131–159. doi: 10.1002/med.20048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa SJ, Nadeem A, Fan M, Zhong H, Belardinelli L, Zeng D. Effect of a specific and selective A2B adenosine receptor antagonist on adenosine agonist AMP and allergen-induced airway responsiveness and cellular influx in a mouse model of asthma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320:1246–1251. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.112250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata H, Yoshioka K, Kamiya T, Tsuga H, Oyanagi K. Functions of heteromeric association between adenosine and P2Y receptors. J Mol Neurosci. 2005;26:233–238. doi: 10.1385/JMN:26:2-3:233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochaion A, Bar-Yehuda S, Cohen S, Amital H, Jacobson KA, Joshi BV, Gao ZG, Barer F, Zabutti A, Del Valle L, Perez-Liz G, Fishman P. The A3 adenosine receptor agonist CF502 inhibits the PI3K, PKB/Akt and NF-κB signaling pathways in synoviocytes from rheumatoid arthritis patients and in adjuvant induced arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;76:482–494. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta A, Sitkovsky M. Role of G-protein-coupled adenosine receptors in downregulation of inflammation and protection from tissue damage. Nature. 2001;41:916–920. doi: 10.1038/414916a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura T, Kurogi Y, Hashimoto K, Sato S, Nishikawa H, Kiryu K, Nagao Y. Structure–activity relationships of adenosine A3 receptor ligands: new potential therapy for the treatment of glaucoma. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:3775–3779. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.04.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer TM, Poucher SM, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. 125I-4-(2-[7-Amino-2-{furyl}{1,2,4} triazolo{2,3-a}{1,3,5}triazin-5-ylaminoethyl)phenol (125I-ZM241385), a high affinity antagonist radioligand selective for the A2A adenosine receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;48:970–974. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe SJ, Knight H, Woessner R. QAF805, an A2b/A3 adenosine receptor antagonist does not attenuate AMP challenge in subjects with asthma. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2007;175:A682. [Google Scholar]

- Penn RB, Pascual RM, Kim YM, Mundell SJ, Krymskaya VP, Panettieri RA, Jr, Benovic JL. Arrestin specificity for G protein-coupled receptors in human airway smooth muscle. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32648–32656. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104143200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porkka-Heiskanen T, Strecker RE, Thakkar M, Bjorkum AA, Greene RW, McCarley RW. Adenosine: a mediator of the sleep-inducing effects of prolonged wakefulness. Science. 1997;276:1265–1268. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5316.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press NJ, Taylor RJ, Fullerton JD, Tranter P, McCarthy C, Keller TH, Brown L, Cheung R, Christie J, Haberthuer S, Hatto JD, Keenan M, Mercer MK, Press NE, Sahri H, Tuffnell AR, Tweed M, Fozard JR. A new orally bioavailable dual adenosine A2B/A3 receptor antagonist with therapeutic potential. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:3081–3085. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinster SC, Hague C, Hall RA. Heterodimerization of G protein-coupled receptors: specificity and functional significance. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:289–298. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.3.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryzhov S, Goldstein AE, Biaggioni I, Feoktistov I. Cross-talk between G(s)- and G(q)-coupled pathways in regulation of interleukin-4 by A2B adenosine receptors in human mast cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:727–735. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.022780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryzhov S, Novitskiy SV, Zaynagetdinov R, Goldstein AE, Carbone DP, Biaggioni I, Dikov MM, Feoktistov I. Host A2B adenosine receptors promote carcinoma growth. Neoplasia. 2008;10:987–995. doi: 10.1593/neo.08478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte G, Fredholm BB. Signalling from adenosine receptors to mitogen-activated protein kinases. Cell Signal. 2003;15:813–827. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(03)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzschild MA, Agnati L, Fuxe K, Chen JF, Morelli M. Targeting adenosine A2A receptors in Parkinson’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:647–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terai T, Kita Y, Kusunoki T, Shimazaki T, Ando T, Horiai H, Akahane A, Shiokawa Y, Yoshida K. A novel non-xanthine adenosine A1 receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;279:217–225. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00165-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udelson JE, Heller GV, Wackers FJ, Chai A, Hinchman D, Coleman PS, Dilsizian V, DiCarli M, Hachamovitch R, Johnson JR, Barrett RJ, Gibbons RJ. Randomized, controlled dose-ranging study of the selective adenosine A2a receptor agonist binodenoson for pharmacological stress as an adjunct to myocardial perfusion imaging. Circulation. 2004;109:457–464. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114523.03312.7D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlok N, Malan SF, Castagnoli N, Jr, Bergh JJ, Petzer JP. Inhibition of monoamine oxidase B by analogues of the adenosine A2A receptor antagonist (E)-8-(3-chlorostyryl)caffeine (CSC) Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:3512–3521. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Lubitz DKJE, Lin RC, Popik P, Carter MF, Jacobson KA. Adenosine A3 receptor stimulation and cerebral ischemia. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;263:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90523-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsak W, Mien LK, Shanab K, Ettlinger DE, Haeusler D, Sindelar K, Lanzenberger RR, Spreitzer H, Viernstein H, Keppler BK, Dudczak R, Kletter K, Mitterhauser M. Preparation and first evaluation of [18F]FE@SUPPY: a new PET tracer for the adenosine A3 receptor. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan TC, Ge ZD, Tampo A, Mio Y, Bienengraeber MW, Tracey WR, Gross GJ, Kwok WM, Auchampach JA. The A3 adenosine receptor agonist CP-532,903 [N 6-(2,5-dichlorobenzyl)-3′-aminoadenosine-5′-N-methylcarboxamide] protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via the sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive potassium channel. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;324:234–243. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CN. Adenosine receptors and asthma in humans. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:475–486. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Burbiel JC, Maass A, Müller CE. Adenosine receptor agonists: from basic medicinal chemistry to clinical development. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2003;8:537–576. doi: 10.1517/14728214.8.2.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Avila MY, Peterson-Yantorno K, Coca-Prados M, Stone RA, Jacobson KA, Civan MM. The cross-species A3 adenosine-receptor antagonist MRS 1292 inhibits adenosine-triggered human nonpigmented ciliary epithelial cell fluid release and reduces mouse intraocular pressure. Curr Eye Res. 2005;30:747–754. doi: 10.1080/02713680590953147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D, Koupenova M, McCrann DJ, Kopeikina KJ, Kagan HM, Schreiber BM, Ravid K. The A2b adenosine receptor protects against vascular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:792–796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705563105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, Huang Z, Mariani J, Wang Y, Moskowitz M, Chen JF. Selective inactivation or reconstitution of adenosine A2A receptors in bone marrow cells reveals their significant contribution to the development of ischemic brain injury. Nat Med. 2004;10:1081–1087. doi: 10.1038/nm1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zezula J, Freissmuth M. The A2A-adenosine receptor: a GPCR with unique features? Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S184–S190. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Wang R, Zambraski E, Wu D, Jacobson KA, Liang BT. A novel protective action of adenosine A3 receptors: attenuation of skeletal muscle ischemia and reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:3685–3691. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00819.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann H. Extracellular metabolism of ATP and other nucleotides. Naunyn–Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362:299–309. doi: 10.1007/s002100000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]