Abstract

Introduction

This research sought to extend knowledge about bystanders in bullying situations with a focus on the motivations that lead them to different responses. The 2 primary goals of this study were to investigate the reasons for children's decisions to help or not to help a victim when witnessing bullying, and to generate a grounded theory (or conceptual framework) of bystander motivation in bullying situations.

Methods

Thirty students ranging in age from 9 to 15 years (M = 11.9; SD = 1.7) from an elementary and middle school in the southeastern United States participated in this study. Open- ended, semi-structured interviews were used, and sessions ranged from 30 to 45 minutes. We conducted qualitative methodology and analyses to gain an in-depth understanding of children's perspectives and concerns when witnessing bullying.

Results

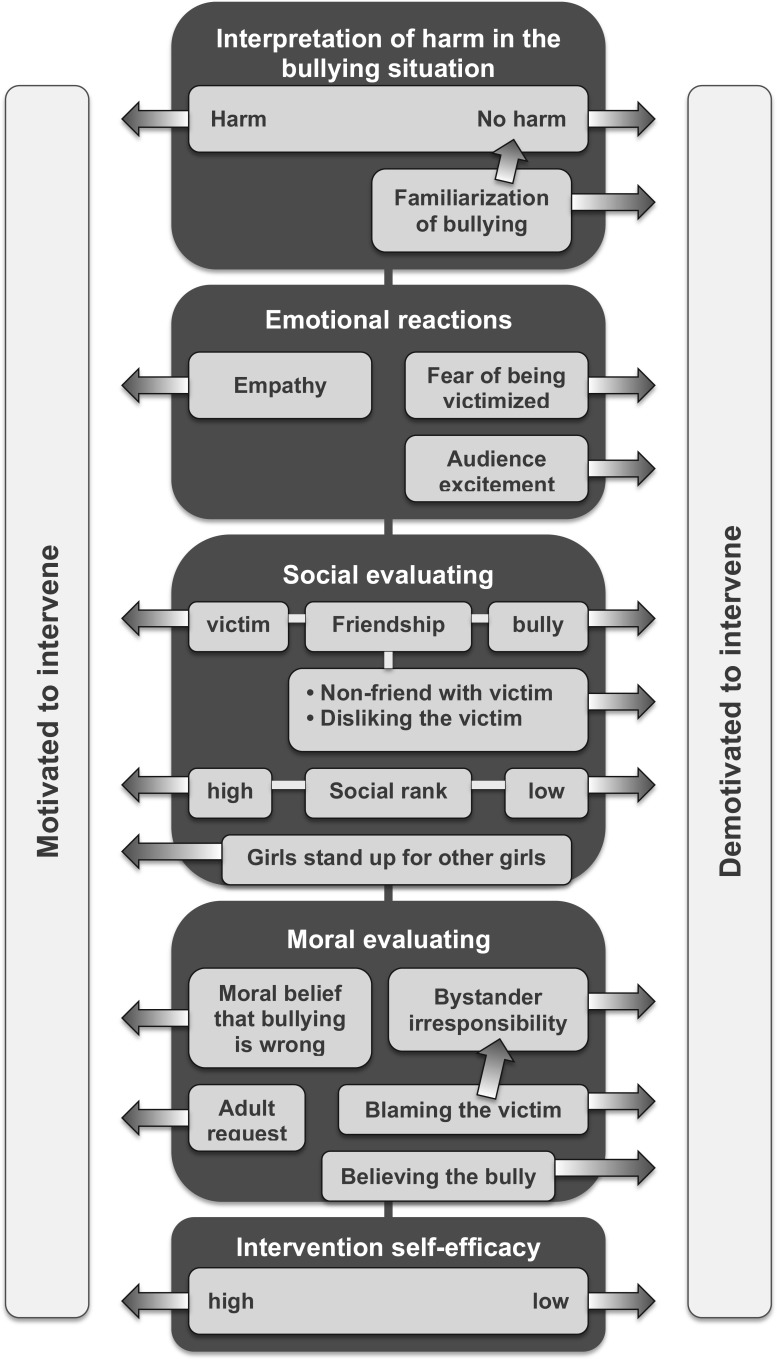

A key finding was a conceptual framework of bystander motivation to intervene in bullying situations suggesting that deciding whether to help or not help the victim in a bullying situation depends on how bystanders define and evaluate the situation, the social context, and their own agency. Qualitative analysis revealed 5 themes related to bystander motives and included: interpretation of harm in the bullying situation, emotional reactions, social evaluating, moral evaluating, and intervention self-efficacy.

Conclusion

Given the themes that emerged surrounding bystanders' motives to intervene or abstain from intervening, respondents reported 3 key elements that need to be confirmed in future research and that may have implications for future work on bullying prevention. These included: first, the potential importance of clear communication to children that adults expect bystanders to intervene when witnessing bullying; second, the potential of direct education about how bystanders can intervene to increase children's self-efficacy as defenders of those who are victims of bullying; and third, the assumption that it may be effective to encourage children's belief that bullying is morally wrong.

INTRODUCTION

Bullying involves repetitive aggression or harassment directed at victims who have less power than bullies.1 Bullying also includes bystanders who observe bullying and can assume a range of roles that include “reinforcers” (provide support to bullies), “outsiders” (remain uninvolved with bullying), and “defenders” (help or support the victim).2 The behaviors of bystanders can have important effects on their peers. Bullying has been found to be more frequent in schools where bystanders displayed behaviors that reinforce bullying, rather than engaging in behaviors that defend the victims, and observational studies have shown that bystanders more often act in ways that do not support victims.3–5

The motivational bases for bystanders' helping a victim of bullying have not attracted much research. Students with high empathy have been found to be more likely to take the defender role.6,7 Moral disengagement, defined as a set of socio-cognitive processes, such as moral justification of harassments/aggression, diffusion of responsibility, blaming the victim and dehumanization, through which people can disengage from humane acts and instead commit inhumane actions against other people, has been negatively associated with defending or helping the victim.8–10

Bandura's socio-cognitive theory11 of agency argues that self-efficacy for a particular activity or action (ie, their beliefs in their capacity to act successfully) is related to their motivation and behavior. In accordance with this theory, researchers have found that bystanders' beliefs in their social self-efficacy (ie self-efficacy for defending and perceived collective efficacy to stop peer aggression) were positively associated with defending behavior and negatively associated with passive behavior from bystanders.12–13 In addition, peer relations also appeared to matter. Bystanders were less likely to act as defenders when they had closer relationships with bullies and were more likely to act as defenders if they had closer relationships with victims.14While researchers have found that bystanders' behavior might be influenced by different motivations, research in this area is rare and has relied on quantitative methods.

Rationale for Study

Although prior research has added to the current knowledge of bystander behaviors and reactions to bullying, the quantitative methods used in these studies do “…not give children an opportunity to discuss their own understanding of bullying in their own voices”.15 A qualitative investigation of children's perspectives about bullying designed to have students discussing their experiences, thoughts and motives in their own words may enable discovery and development of relevant motivational concepts and hypotheses about their inter-relationships.16,17 Therefore, the aims of this study were to use qualitative methodology to investigate the motives reported by children for helping or not helping a victim when witnessing bullying and to generate a conceptual framework of bystander motivation in bullying situations.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were selected from 2 schools serving students from fourth through eighth grade in a southeastern urban school district in the United States (U.S.). The racial breakdown of the fourth and fifth grade school students was 39.9% African American, 54.8% Caucasian, and 5.2% Other. The racial composition of the middle school was 50.4% African American, 44.2% Caucasian, 3.4% Multiracial, and 2% Other. We identified 30 participants through school personnel recommendation, based on convenience and targeted sampling methods.17 School personnel were asked to identify students who represented various roles in bullying incidents, including bullies, victims, and/or bystanders. Parents were sent a consent form to sign if they agreed to have their child volunteer for the study. Students ranged in age from 9 to 15 years (M = 11.9; SD = 1.7). The participant sample was primarily Caucasian (73.3%), with 23.3% African American, and 3.3% identified as Other. The gender breakdown of students was 56.7% male and 43.3% female. Thirty percent of the participants were enrolled in the eighth grade, with 10% in seventh grade, 27% in sixth grade, 20% in fifth grade, and 13% in fourth grade.

Procedures and Instrumentation

All students signed assent forms prior to participation. The study procedures and instrumentation were approved by the university's institutional review board and the district's research office. Open-ended, semi-structured interviews were used and sessions ranged from 30 to 45 minutes. Interview questions addressed broad categories related to bullying with opportunities to query for additional information. All interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and then imported into the ATLAS.ti v4.1software program (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin Germany) for the purpose of data analysis.

Data Analysis

We used a deductive-inductive process to develop and refine the original coding scheme, establish inter-rater reliability, and analyze the data, consistent with established qualitative analysis procedures and grounded theory methods.16,18–20 We conducted further data analysis of the original code “bystander” in this study to develop a more in-depth coding scheme to examine bystander motivations. First, 2 research team members used a deductive coding process by analyzing data through the lens of existing literature. Second, inductive codes were developed in an attempt to represent codes from the students' perspectives that may not be represented in the literature. Third, the entire research team provided feedback on the codes and definitions. Fourth, based on the resulting coding scheme, all data were independently coded by 2 of the authors and disagreements were discussed until 100% consensus was reached. Finally, we employed a grounded theory approach to generate a conceptual framework to best represent the data.16

RESULTS

The qualitative analysis of the interview data generated a conceptual framework of bystander motivation to intervene in bullying situations. According to this framework, deciding whether to help or not help the victim in a bullying situation depends on how bystanders define and evaluate the situation, the social context, and their own agency (Figure 1). A set of motive domains emerged that may influence student motivation to intervene or not intervene in bullying situations: (a) interpretation of harm in the bullying situation, (b) emotional reactions, (c) social evaluating, (d) moral evaluating, and (e) intervention self-efficacy.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of bystander motivation to intervene in bullying situations.

Interpretation of Harm in the Bullying Situation

The degree to which bystanders perceived the bullying situation as harmful influenced their motivation to intervene. Situations in which bullying was seen as causing significant harm to the victim required intervention. For example, one student stated, “I mean, like, if it's out of hand, somebody might go and tell the teacher, but if it's something like really nothing, then nobody will tell on nobody. Nobody will be a snitch over something little, but if it's something big, you will tell.” In parallel, some students described times when bystanders chose not to intervene because the bullying was believed to cause limited harm and did not require action. One student explained, “So, if it's not something that's dangerous or just really mean, probably I would just leave it alone.”

A sub-construct of interpretation of harm in bullying situations was habituation to bullying, which is defined as a bystander's failure to intervene because bullying takes place often and students view it as a routine phenomenon. One student stated “The kid just did something embarrassing and the whole class just laughs at him. It's nothing big because you know it's not like they're being spiteful or anything, they're just kind of laughing. That could be something that everyone just thinks is normal … because everyone does it.”

Emotional Reactions

According to some students, bullying could evoke different emotional reactions from bystanders, and these emotional reactions (empathy, fear of being victimized, audience excitement) appeared to influence their decision-making process of intervening or non-intervening. For example, a bystander experiencing empathy may decide to intervene as a result of feeling badly for the victim. One student expressed this sentiment by saying, “My friends and I usually just stand up for that person even if we don't like them very much . . . because I feel really bad for them.”

Fear of being victimized was defined as not intervening due to fear of being a future target of the bully. One student stated that his peers “…usually don't tell anybody because they think the other person might beat them up or something or start picking on them.” Audience excitement referred to the joy, excitement, and desire to watch the bullying and included times when bystanders did not intervene and encouraged the bullying due to an interest in watching the bullying incident. One student described an example, “Two boys did get into a severe fight, and … one of them got a black eye, and one of them just got beat down, and they pretty much beat each other up pretty well, and there was this circle around them that was actually saying, ‘Fight! Fight! Fight! Fight!”

Social Evaluating

Social evaluating was coded when bystanders considered and evaluated social relationships and social positions (friendship, social rank, and gender differences) when witnessing bullying and before deciding whether or not to help. Friendship referred to the impact of the relationship between the bystander and the victim or bully on the bystander's decision about intervening. Whereas a close relationship with the victim was associated as a motive to help, a close relationship with the bully and no relationship with the victim were discussed as motives for not helping the victim. In addition, disliking the victim was identified as a reason not to intervene. One student said, “It kinda depends on the person [the victim]. Like, if they don't like the person, they might laugh. But if they're friends with them, then they try to, like, help them out or whatever.” Another student stated, “Most kids either will if their friend is bullying someone they'll either join in or not tell anybody, like pretend it's not there.” When asked what he would do when he saw someone being bullied, 1 student said, “If it's someone I don't know, I mean, I just sort of keep to myself.”

Considering and evaluating social rank described times when the bystander's motivation to help was influenced by a bully's position in the social hierarchy among peers. If the bully was a person whom others respected, then bystanders might be less motivated to intervene. A participant stated, “If someone who people respect and feel like they're higher than them or something is picking on someone, everyone's going to go on. But if it's someone who people think are lower than themselves [then they] are going to be like, ‘quit you don't really have room to talk.' I mean, and that's bad because nobody, none of these people who are higher, better, or whatever, should be bullying people who are lower or whatever.” However, if a bystander considered the bully as a person with a lower social rank, the social hierarchy would not inhibit intervention.

Some of the girls argued that girls stand up for other girls in bystander behavior. For example, certain girls chose to stand up for other girls when the bullying was perpetrated by a boy. One female student shared, “The girls are nice and they tell the boys to stop . . . like some of them are really strong and fast so they'll start chasing them and then I just start laughing my head off because the boys are running away from the girls.” Another student discussed how girls were more likely to come to her aid when she was being victimized, while boys more frequently joined in on the bullying, “A lot of the girls will come around and help me, but most of the boys will just make fun of me. I don't have many friends with the boys . . .”

Moral Evaluating

Moral evaluating refers to judging or evaluating the observed bullying act in terms of right or wrong, as well as evaluating and attributing responsibility. This concept included situations in which the bystander expressed a moral belief that bullying is wrong and should not occur. One bystander shared, “. . . the kid was looking all scared and everything because he thought he was going to get in trouble about what he said, and so I went and told the teacher because, I mean, it just really messed me up because he is a really smart kid, and he really didn't deserve getting picked on like that because he was helping most of the kids that were making fun of him.” A sub-construct of this concept is adult request where a child's motivation for intervening was due to an adult's request that they take action when they see bullying. One participant discussed this motivation, stating, “I know because I'm on the basketball team, our coaches like, ask us to like, try and help people and stop stuff like that because some people look up to us.”

Another sub-construct was bystander irresponsibility, referring to situations in which the bystander did not intervene because the bystander did not believe it was his or her moral responsibility to take action or that intervening was important (ie moral disengagement). When asked about witnessing bullying, 1 student stated, “I've seen it, but it's not my business.” Another student described her feelings when she observed bullying, saying, “I just don't mind. I just turn the other way, walk right by, don't listen.” Blaming the victim referred to times when the bystander did not intervene because he or she believed that the bullying was in some way the victim's fault. One participant described this code, saying, “They just like stare and maybe like one or two might jump in and try to stop it, but basically they all just stare. Maybe they agree with the person that the kid who's getting picked on deserved it.” Hence, blaming the victim justified bullying. Blaming the victim also was linked to the former concept bystander irresponsibility. According to some students, believing or spreading rumors created by the bully contributed to bystander lack of intervention, moral justification of the bullying, and greater likelihood that the bystander would join in on the bullying. One student shared, “They just watch the crowed and watch them bug you or tease the person, because . . . they heard the rumor about what happened, and they just tease him. They tease them because they think that the rumor that the bully said could be the truth.”

Intervention Self-Efficacy

Intervention self-efficacy referred to situations in which students selected a mode of intervention based on how effective they believed their actions would be (i.e., high level of intervention self-efficacy). One student chose to involve an adult because she did not feel that she could effectively handle a situation. “Tell a counselor or an adult because adults are stronger and more powerful and stuff because during that I don't think a normal fifth or fourth grader could handle holding back the two children that were fighting in the cafeteria because they were like, struggling and wiggling and kicking and throwing.” Low level or lack of intervention self-efficacy was mentioned infrequently and referred to times when a bystander was unable to intervene because he or she did not feel capable of doing so. One student described this sentiment, stating, “I really like to try, but I really couldn't do anything. I don't want to hurt anyone.”

DISCUSSION

The present study contributes to the bullying literature by providing a conceptual framework for bystander motivation to intervene in bullying situations, based on a systematic analysis of children's self-reported perspectives on bullying and bystander motives. While it is premature to reach conclusions about which elements in the framework are most important, the findings provide guidelines to conceptualize potentially influential factors in bystander motivation to defend victims that can inform future research and might enhance anti-bullying practices at school. Future research is needed to confirm the validity of this framework as depicted in Figure 1. One important component of the framework is bystanders' interpretation of harm in the bullying situation. If there is no perceived harm, there may be little motivation to help the victim. If this finding is confirmed, then there may be a need to for research to evaluate strategies designed to help children to identify and appropriately interpret harm in bullying situations, since high sensitivity in recognizing harm may be associated with the motivation to intervene.

Another important finding was the influence of emotional reactions. These findings suggested that an empathic reaction may motivate bystanders to intervene, which is congruent with previous researchers who found positive associations for empathy with helping the victim in bullying situations.6,7 The current study revealed additional emotional reactions that were associated with the motivation to not intervene: fear of being victimized and audience excitement. Additional research is needed to confirm these negative motivations. Future researchers also may seek to determine factors that moderate and mediate the impact of these motivational factors.

According to the framework that emerged in this investigation, a particularly important motivational factor was bystanders' efforts to socially evaluate bullying. Consistent with Oh and Hazler's study14, being a friend with the bully or a non-friend with the victim was linked to motivation not to intervene and being a friend with the victim was related to motivation to intervene. In addition, whereas having a higher social rank than the bully appeared to motivate intervening, having a lower social rank appeared to demotivate intervening. Hence, the findings indicated that peer relationships and peer social hierarchy may be important motivational factors. Research is needed to confirm and expand on these findings. In addition, future research on intervention may evaluate anti-bullying practices that are constructed based, in part, on these motivations.

Respondents indicated the potential importance of bystanders evaluating bullying on a moral basis. The belief that bullying is wrong and that teachers/adults want bystanders to intervene were reported as moral reasons that may motivate bystander intervention. Findings also revealed that moral evaluation can provide motivation not to intervene, which is consistent with Bandura's concept of moral disengagement.8 Finally, some respondents indicated that intervention self-efficacy might provide motivation to intervene and this supports prior resesarch.13 In sum, the findings demonstrated a complex interplay of possible motives and reasons that seem to influence children's motivation to intervene or not intervene as bystanders in bullying situations. All of these findings require future confirming research and depending on future findings, the motivational framework in Figure 1 provides suggestions that may be included in future research about efforts to promote bystander intervention.

LIMITATIONS

While the sample size compares favorably with other qualitative research, this study was limited to 1 urban school district in the southeastern U.S. which limits generalizability. Convenience and targeted sampling techniques were used and may have led to sampling bias (e.g., Caucasian students being overrepresented). However, based on the targeted criteria and exploratory nature of this study, the priority was to obtain a sample of students who had been involved in bullying incidents as bullies, victims, and/or bystanders. In addition, considering that bullying was the interview topic, social desirability bias was a possible threat in this study. To reduce this risk, the interviewers were instructed and trained to listen actively, take a non-judgmental approach, and use open follow-up questions. Future qualitative research is needed to test and validate the emergent framework to understand bystanders' motivations in bullying across various contexts and countries. Quantitative research also is necessary to test this conceptual model and to examine hypothetical interrelationships between the model's key concepts.

CONCLUSION

In order to increase the rate of intervention among bystanders, additional research is needed about 3 important components of the framework of motivations for intervention from bystanders: (1) teacher/adult expectations may add to children's motivations to help victims when bullying is witnessed; (2) bystander self-efficacy may enhance their motivation to attempt to defend victims of bullying; and (3) children's moral beliefs that bullying is wrong may increase the chances that bystanders will intervene in bullying situations. Simultaneously, motives associated with moral disengagement, such as bystander irresponsibility, blaming the victim, and uncritically believing the bully may decrease the likelihood of bystander intervention. Assuming that future research supports the importance of these motivations, subsequent research may be used to test the efficacy of preventive interventions designed to promote positive motivations while reducing negative motivations.

Footnotes

Supervising Section Editor: Abigail Hankin, MD, MPH

Reprints available through open access at http://escholarship.org/uc/uciem_westjem

Conflicts of Interest: By the WestJEM article submission agreement, all authors are required to disclose all affiliations, funding sources and financial or management relationships that could be perceived as potential sources of bias. The authors disclosed none. This work was funded through CDC Grant 5 R49 CE001494.

REFERENCES

- 1.Olweus D. Bullying at School. Malden, MA: Blackwell;; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salmivalli C, Lagerspetz K, Björkqvist K, et al. Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior. 1996;22:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kärnä A, Voeten M, Poskiparta E, et al. Vulnerable children in varying classroom contexts: bystanders' behaviors moderate the effects of risk factors on victimization. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2011;56:261–282. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig WM, Pepler DJ, Atlas R. Observations of bullying in the playground and in the classroom. School Psychology International. 2000;21:22–36. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawkins DL, Pepler DJ, Craig WM. Naturalistic observations of peer interventions in bullying. Social Development. 2001;10:512–527. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Correia I, Dalbert C. School bullying: belief in a personal just world of bullies, victims, and defenders. European Psychologist. 2008;13:248–254. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nickerson AB, Mele D, Princiotta D. Attachment and empathy as predictors of roles as defenders or outsiders in bullying interactions. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46:687–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandura A. Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 1999;3:193–209. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gini G. Social cognition and moral cognition in bullying: what's wrong? Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:528–539. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Obermann ML. Moral disengagement among bystanders to school bullying. Journal of School Violence. 2011;10:239–257. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman; (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gini G, Albiero P, Benelli B, et al. Determinants of adolescents' active defending and passive bystanding in bullying. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31:93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barchia K, Bussey K. Predictors of student defenders of peer aggression victims: empathy and social cognitive factors. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2011;35:289–297. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh I, Hazler RJ. Contributions of personal and situational factors to bystanders' reactions to school bullying. School Psychology International. 2009;30:291–310. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bosacki SL, Marini ZA, Dane AV. Voices from the classroom: pictorial and narrative representations of children's bullying experiences. Journal of Moral Education. 2006;35:231–245. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeCompte MD, Schensul JJ. Ethnographer's Toolkit, Book 1: Designing and Conducting Ethnographic Research. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press;; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varjas K, Meyers J, Bellmoff L, et al. Missing voices: fourth through eighth grade urban students' perceptions of bullying. Journal of School Violence. 2008;7:97–118. [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeCompte MD, Schensul JJ. Ethnographer's Toolkit, Book 5: Analyzing and Interpreting Ethnographic Data. Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press;; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage;; 1994. [Google Scholar]