Abstract

Background

Mechanisms of injury in trauma populations evolve over time as a result of system changes, prevention and safety activities, and shifts in population composition. Such changes have implications for reimbursement and resource utilization within all trauma centers. This study examines the evolution of trauma mechanisms at a regional Level I trauma center over 10 years to document the impact of these changes.

Methods

After IRB approval, the trauma registry was queried for total trauma admissions over 10 years. Data points of mechanism of injury, ISS, age, mortality, financial information, and discharge disposition were obtained. Statistical significance was determined by Chi square analysis.

Results

Total admissions increased steadily over the course of the 10 years studied. The percentage of motor vehicle crashes (MVC) decreased, while falls increased. Fall patients were older, with lower ISS and with longer length of stay. Mortality rates were higher, but statistically similar to those of the population as a whole. Fall patients were more frequently discharged to skilled nursing facilities. Federally supported Medicare programs increased steadily as a portion of payer mix.

Conclusions

Mechanism of injury within our regional Level I trauma center changed over time with MVC as a percentage of blunt trauma mechanisms decreasing as falls increased. Falls are now a leading mechanism for traumatic injury, even at tertiary referral systems, and will continue to rise in incidence as the population of America ages. This change has direct implications for reimbursement and resource utilization. Current scoring systems employed by trauma centers do not predict this trend well.

Keywords: Trauma systems, Elderly, Falls, Trauma Mechanisms, Resource utilization

Introduction

A study of the changes in trauma systems over time is a study of the changes in technology, living conditions, access to care, and epidemiology of the nation as a whole. As these factors change, they are reflected by the evolution of mechanisms of injury seen in trauma populations, the age of the population itself, the number of chronic conditions requiring interventions, and the resultant mortality and morbidity of trauma. Trauma or accidental injury is among the top five diagnoses of the public health cost burden in America; the estimated cost associated with both fatal and nonfatal injuries in the year 2000 was $406 billion dollars, a portion of which was due to lost productivity and direct expenditures due to rehabilitation [1].

Injury is currently the fourth leading cause of death in the United States in all age groups, accounting for over 182,000 deaths annually [2]. It is the leading cause of death among children, adolescents and young adults, and the fifth leading cause of death in individuals over 65 [2,3]. Interestingly, though injury causes fewer deaths in people over the age of 65 than other causes like cancer and cardiovascular disease, the rate of injury death is three times higher in this age group than any other [4]. In 2003, the elderly, defined as people with age greater than 65, comprised 12% of the US population but accounted for 25% of injury related deaths and 30% of injury related hospitalizations. As the “baby boomer” generation reaches the age of 65, the percentage of the US population represented by this age group is expected to increase from 12 to nearly 20% by 2030 [2]. As this population ages, so too will its impact on trauma admissions, reimbursement, patient care, and expenditures. In fact, it is expected to bankrupt the Medicare system.

The purpose of this study is to document changes in trauma mechanisms and demographics and the potential impact of these changes at a mature Level I Trauma Center over time. We hypothesized that changes in demographics, mechanism, and payer source have occurred, and that evaluating these trends would help us better understand the challenges facing the future of trauma care and to allow insight into development of strategies to improve delivery of that care.

Materials and methods

Approval for this study was obtained from the Graduate Medical School and the Institutional Review Board. The Trauma Registry of the American College of Surgeons (TRACS) was then reviewed for total trauma admissions from January 1998 through December 2008. Mechanism of injury, ISS, age, mortality, financial information, and discharge disposition were collected for each patient over this 10 year time period.

We specifically reviewed patients sustaining injuries from two major injury mechanisms: motor vehicle collisions and falls. Within these two data sets, we looked at age differences, ISS, mortality rates, payer source, and whether the patients were discharged to home or to a rehabilitation facility.

Chi square analysis was performed between data sets. There was no statistically significant difference between mortality rates in the falls group or the MVC group for any year (p ranges between 0 and 0.9). There was a numerically higher death rate in the falls group when compared to the MVC group.

Results

There were 36,166 patients admitted through Trauma Services at the University of Tennessee Medical Center between January 1998 and December 2008 (Table 1). Motor vehicle collisions remained the chief mechanism by which this patient population sustained injury throughout the ten year time period, although the percentage has gradually declined.

Table 1.

This table depicts the trends in admission rates, number of MVC admissions versus fall admissions, and the respective ages, injury severity scores, and death rates in each group

| Year | Total Admit | MVC | Age | ISS | Death | Falls | Age | ISS | Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 2752 | 1409 (51.2%) | 34.7 | 13.1 | 60 (4.3%) | 504 (18.3%) | 49.8 | 10 | 20 (4%) |

| 1999 | 2790 | 1512 (54.2%) | 35.2 | 14.3 | 85 (5.6%) | 423 (15.2%) | 51.8 | 11.2 | 18 (4.3%) |

| 2000 | 3302 | 1684 (51%) | 35.5 | 11.8 | 76 (4.5%) | 609 (18.4%) | 49.5 | 9.7 | 29 (4.8%) |

| 2001 | 3067 | 1526 (49.8%) | 35.3 | 10.4 | 72 (4.7%) | 587 (19.1%) | 49.2 | 9 | 28 (4.8%) |

| 2002 | 3089 | 1573 (50.9%) | 35.5 | 10.4 | 76 (4.8%) | 594 (19.2%) | 53.4 | 9.1 | 36 (6%) |

| 2003 | 3071 | 1496 (48.7%) | 36.4 | 11.3 | 52 (3.5%) | 584 (19%) | 53.6 | 9.4 | 31 (5.3%) |

| 2004 | 3425 | 1572 (45.9%) | 37.4 | 13.5 | 93 (5.9%) | 699 (20.4%) | 52 | 10.5 | 26 (3.7%) |

| 2005 | 3652 | 1587 (43.5%) | 37 | 13.1 | 36 (4%) | 804 (22%) | 54.5 | 10.7 | 36 (4.5%) |

| 2006 | 3710 | 1526 (41.1%) | 37.7 | 14.4 | 65 (4.3%) | 848 (22.9%) | 54.3 | 10.9 | 43 (5.1%) |

| 2007 | 3609 | 1361 (37.7%) | 36.7 | 15.2 | 36 (5.7%) | 866 (24%) | 54.3 | 10.8 | 36 (4.2%) |

| 2008 | 3699 | 1325(35.8%) | 38.8 | 14.5 | 56 (4.2%) | 997 (27%) | 56.2 | 10.7 | 47 (4.7%) |

Within the MVC population, the average age was 36.4. The average ISS was 12.9 and mortality was 5.15% for this group. In contrast to the MVC population, the fall population was older with a lower average ISS. The average age of patients within the fall group was 56.2 years and the average ISS was 10.2. Despite having a lower ISS, the average mortality rate of 5.2% within the fall cohort remained similar to that of the population as a whole, which was 4.7%.

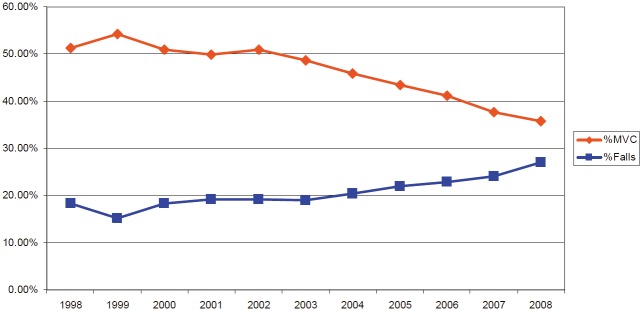

Looking at trends over the last ten years within our hospital, the overall fall population has aged and more falls are admitted than 10 years ago. In 2008, patients had a mean age of 56.2 years, while the average age in 1998 was 49.8. The actual number of falls has doubled in the course of this ten year time period. In addition, the percentage of falls is gradually increasing while the percentage of MVCs is gradually decreasing (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends in MVCs and Falls in trauma population (1998-2008). Trends over ten years in admissions from motor vehicle collisions versus falls; note the number of MVC admissions has steadily declined, while the number of fall admissions has steadily increased.

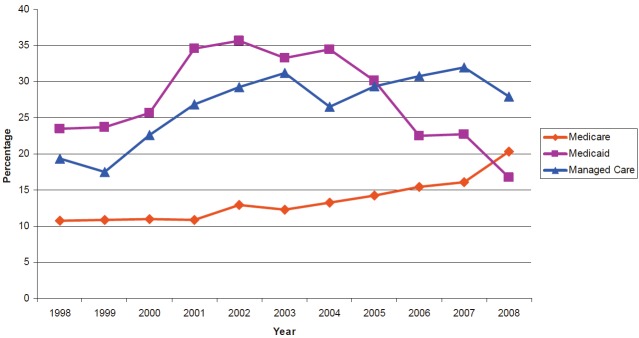

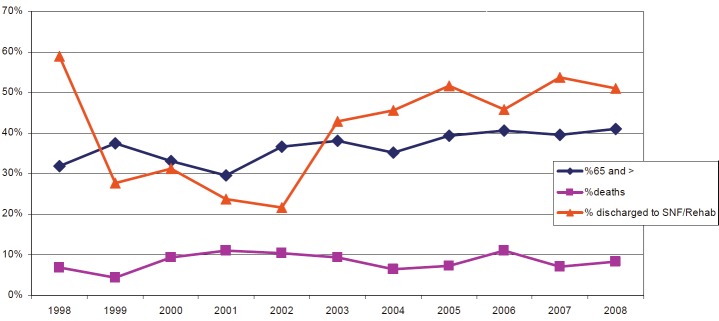

Trends in payer mix in the fall population are depicted in Figure 2 increased proportion of Medicare as a payer source was seen. The percentage of Medicare within this cohort represents about half of the patients, and a large percentage of these patients were discharged to a skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation center (Figure 3). No statistical significance was assigned to these trends; these numbers illustrate descriptive trends only.

Figure 2.

Overall trauma payer mix. Trends in payer source for the trauma population over ten years. Note the proportion of Medicare patients is gradually increasing.

Figure 3.

Trends in Falls 65 years old and older (1998-2008). Trends in fall patients with regard to death rates, age >65 years of age, and percentage discharged to a long term care facility. While age and the percentage of patientsdischarged to a facility increased, the death rate remained largely stable over ten years.

Discussion

A change in mechanism of injury patterns seen within a mature trauma center reflects social, political, and economic changes rather than changes in medical care. In the past, trauma systems were oriented to treating injuries for motor vehicle collisions and firearm wounds, which represented the two leading causes of fatal injury [2]. Historically, falls were the number one cause of nonfatal injury and were thought to be issues for suburban trauma centers only [2]. Falls currently account for 11% of all injury deaths and one third of all injury related hospital admissions5. Studies indicate that 2.2 million people yearly have a medically injurious fall [6]. It is estimated that 30% of adults age 65 and older fall each year [7]. One half of those who fall in one year will fall again, and factors predicting whether they fall repeatedly include increasing age, female sex, and poor baseline health status [3,6]. The number of falls is increasing in the elderly population; between 1970 and 1995 there was a 284% increase in the number of falls, and an 80% increase in mortality among falls [3,8].

The cost of falls in the trauma population is significant, especially among the elderly. 5% of falls will result in an extremity fracture, 11% result in more serious injury, and falls are the most common cause of traumatic brain injury in the elderly [3,9]. The direct cost of falls for people 65 and older exceeded $19 billion in 2000, and the annual direct and indirect cost are expected to reach $54.9 billion dollars by 2020 [2]. It is clear where these expenditures come from; 42% of falls require hospitalization, and 43% of those patients required discharge to a skilled nursing facility [7]. This translates to an estimated cost per fall patient of $2,039 [10]. These epidemiologic and cost trends are seen not only in the US, but in other developed nations including Singapore, the United Kingdom, and Finland [11-13].

Such trends have profound implications for health care systems as a whole. The percentage of elderly patients covered by Medicare or similar payer sources is much higher than that of the general population, and this raises concern as government reimbursement rates continue to drop. A double digit drop in physician payments has been averted by crisis driven congressional action in the last few years, however there continues to be a push from the federal government to reduce reimbursement rates. Additionally, Medicare reimbursement is already inadequate to meet the costs trauma care [14].

We are seeing a decreasing impact of motor vehicle collisions and increasing impact of falls on our system. This is a progression forced by changes in technology, population age, safety measures, and education. For example, people have become more aware of the importance of safety belts and legislation enforces their use. In addition, motor vehicles are engineered to withstand more kinetic energy and transmit less of this energy to the victims of collisions, thus reducing injury due to MVC. On the converse, many providers fail to recognize the impact of falls in their elderly patients, and therefore do not educate appropriately on how to prevent them. As lean body mass decreases in the elderly, muscle weakness and gait disturbances become more common. It is imperative that precautions are taken within the home to reduce obstacles, provide aids for navigation and ambulation up stairs and through tight spaces, and provide a means of assistance should a fall occur.

As the population of the country ages, so will the trauma populations of Level I and community trauma centers. This necessitates awareness of all stakeholders, but most importantly on the part of the legislators to allow continued financial support to meet these needs. It requires nurses and physicians to be aware of the changes in care patterns to the elderly to ensure they provide quality care for the best outcomes.

Falls among the elderly are an increasingly large portion of the trauma population. This trend is illustrated by our ten year review. In fact, the data from our institution in the year following this study revealed that the number of falls actually superseded that of MVCs. This is not unique to the United States as numerous global papers in the literature document similar findings. Despite a lower ISS within this group, mortality rates among elderly who fall are higher than the mortality rates of the trauma population as a whole. Current scoring systems, such as the Injury Severity Score, do not allow for chronic health problems, which may increase mortality and morbidity. In addition, the loss of independent activities of daily living as a result of the morbidity associated with their injuries drives a significant portion of this group into long term skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation center placement [14]. As the proportion of this population being insured by Medicare increases, this places an ever increasing financial burden on the entire health care system.

The magnitude of this problem is understated. Current practice in emergency departments fail to recognize risk factors, fail to emphasize these risk factors, fail to implement appropriate physical therapy programs, and fail to appropriately educate family members and patients [15]. Primary care physicians are likely not initiating fall reducing prevention programs. This contributes to an increasing number of readmissions for the same problem. Data shows that the early recognition of risk factors, education of trauma and emergency department staff, and implementation of fall prevention programs in the home and community of the patients reduced the risk of falling by eleven percent and at a modest cost [9,16].

The purpose of this study was to review the changing demographics of our trauma system and to add to the evidence that already exists to help spur health care policy directed toward addressing the economic burden this is placing on the health care system and to help implement more effective prevention programs within our community.

References

- 1.Finkelstein EA, Corso PS, Miller TR. The Incidence and Economic Burden of Injuries in the United States. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacKenzie EJ, Fowler CJ. Epidemiology. In: Feliciano DV, Moore EE, Mattox KL, editors. Trauma. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1996. pp. 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kannus P, Parkkari J, Koskinen S, Niemi S, Palvanen M, Jarvinen M, Vuori I. Fall-Induced Injuries and Deaths Among Older Adults. JAMA. 1999;281:1895–1899. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.20.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. interim projections by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin. http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/usinterimproj/. Accessed August 28, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC Cost of Falls Among Older Adults. http://www.cdc.gov/Homeand RecreationalSafety/Falls/fallcost.html. Accessed August 7, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shumway-Cook A, Ciol MA, Hoffman J, Dudgeon BJ, Yorkston K, Chan L. Falls in the Medicare population:incidence, associated factors, and impact on health care. Phys Ther. 2009;89(4):324–32. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander BH, Rivara FP, Wolf ME. The Cost and Frequency of Hospitalization for Fall-Related injuries in Older Adults. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1020–1023. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.7.1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorina Y, Hoyert D, Lentzner H, Goulding M. Aging Trends, No 6. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 2006. Trends in Causes of Death among Older Persons in the United States. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens JA, Corso PS, Finkelstein EA, Miller TR. The costs of fatal and non-fatal falls among older adults. Injury Prevention. 2006;12:290–295. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.011015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll NV, Slattum PW, Cox FM. The Cost of Falls Among the Community-Dwelling Elderly. JMCP. 2005;11:307–16. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.4.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeo YYC, Lee SK, Quek LS, Ooi SBS. A review of elderly injuries seen in a Singapore emergency department. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:278–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scuffham P, Chaplin S, Legood R. Incidence and costs of unintentional falls in older people in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:740–744. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.9.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kannus P, Parkkari J, Niemi S, Palvanen M. Fall-Induced Deaths Among Elderly People. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:422–424. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reed RL, Lawrence II, Luchette FA, Esposito TJ, Kerz KPC, Gamelli RL. Medicare’s Global Terrorism: Where is the Pay forPerformance? J Trama. 2008;64:374–383. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815f6f11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowland K, Maitra AK, Richardson DA, Hudson K, Woodhouse KW. The discharge of elderly patients from an accident and emergency department: functional changes and risk of readmission. Age Ageing. 1990;19:415–418. doi: 10.1093/ageing/19.6.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller E, Wightman E, Rumbolt K, McConnell S, Berg K, Devereaux M, Campbell F. Management of fall-related injuries in the elderly: A retrospective chart review of patients presenting to the emergency department of a community-based teaching hospital. Physiother Can. 2009;61:26–37. doi: 10.3138/physio.61.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]