Abstract

Objective The goal of this study is to identify individual, family/cultural, and illness-related protective factors that may minimize asthma morbidity in the context of multiple urban risks in a sample of inner-city children and families. Methods Participating families are from African-American (33), Latino (51) and non-Latino white (47) backgrounds. A total of 131 children with asthma (56% male), ages 6–13 years and their primary caregivers were included. Results Analyses supported the relationship between cumulative risks and asthma morbidity across children of the sample. Protective processes functioned differently by ethnic group. For example, Latino families exhibited higher levels of family connectedness, and this was associated with lower levels of functional limitation due to asthma, in the context of risks. Conclusions This study demonstrates the utility of examining multilevel protective processes that may guard against urban risks factors to decrease morbidity. Intervention programs for families from specific ethnic groups can be tailored to consider individual, family-based/cultural and illness-related supports that decrease stress and enhance aspects of asthma treatment.

Keywords: asthma outcomes, cultural factors, inner city, pediatric asthma, protective factors

Introduction

Ethnic Minority and Urban Children With Asthma: Considering Culture and Context

Asthma burden is more pronounced in ethnic minority children compared to non-Latino white (NLW) children (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007). Puerto Rican children experience higher asthma prevalence rates and greater risk for asthma morbidity compared to children of other Latino ethnic groups, and to children of African-American (AA) and NLW backgrounds, even after accounting for socioeconomic status (Lara, Akinbami, Flores, & Morgenstern, 2006). A growing body of work supports the multidetermined nature of asthma disparities (Canino et al., 2006). Among ethnic minority youth, those residing in urban settings display even higher levels of asthma morbidity (e.g., more asthma-related emergency department visits) (Rand et al., 2000). Stresses related to urban poverty increase asthma risk and include violence, family poverty, and racial discrimination (Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2007; Wright et al., 2004). Culturally relevant variables, such as acculturative stress, medication beliefs and concerns, and use of home remedies may also interfere with families’ implementation of asthma treatment strategies (Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2008; McQuaid, 2009).

Many studies addressing contributing factors to poor asthma outcomes among ethnic minority children tend to focus on a singular risk factor (e.g., ethnic minority status, low socioeconomic status, SES) and examine how the factor is associated with a specific asthma outcome. This approach may have limited utility (Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2007). First, disentangling the independent effects of these risk factors on asthma outcomes is challenging, given that they tend to be highly interrelated. Furthermore, this approach does not further understanding of what it is about living in an urban residence or being a member of an ethnic minority group that impacts health outcomes.

Multiple risk models may be better suited to capture the social realities of urban families’ lives. In contrast to additive indices that represent a simple summation of the number of risks experienced by families, a Cumulative Risk Index (CRI; Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2007; Everhart et al., 2008) accounts for both quantity and quality (i.e., severity) of numerous risk factors simultaneously. Our previous work has tested a CRI and its link with morbidity, by incorporating cultural (e.g., acculturative stress), sociocontextual (e.g., neighborhood stress), and asthma-specific risks (e.g., disease severity; see Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2007). The CRI was significantly related to more morbidity (ED visit in the past 12 months), even after accounting for poverty or severity.

Who is Doing Well and How? Protective Factors Associated with Optimal Asthma Outcomes

It is important, also, to study characteristics of urban children and families who are functioning well in the face of heightened risk. This strength-based approach involves the identification of protective factors associated with effective management of asthma, despite the presence of risks related to urban poverty and asthma (Koinis-Mitchell, Murdock, & McQuaid, 2004). Identifying protective factors offers modifiable targets for culturally tailored interventions that may meet the needs of specific ethnic groups by incorporating characteristics that families already utilize and draw upon to manage asthma successfully. It is first necessary to define resilience and this strength-based, theoretical approach, as the terms associated with this framework are often used inaccurately (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000).

Defining Resilience

Resilience is defined as a “a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity” (Luthar et al., 2000, p. 543). For resilience to be demonstrated, two conditions must be met: (a) the achievement of positive adaptation and (b) the presence of major assaults on the developmental process (Hauser, Allen, & Golden, 2007). Adversity is typically assessed through the identification of risk factors, such as poverty. Resilient-based outcomes (e.g., psychosocial competence) are facilitated via protective factors, for example high self esteem, that minimize the effect of one or more risk factors to contribute to a more optimal outcome (Luthar et al., 2000; Masten, 2001). Protective factors buffer risk effects, specifically under high conditions of risk. Finally, a resource factor is associated with an optimal outcome regardless of an individual’s exposure to risk. These terms are operationalized and tested according to specific criteria that are both empirically and theoretically derived, and confirmed through statistical approaches (e.g., Luthar et al., 2000).

Some research has sought to apply this framework to study urban and ethnic minority families who have children with asthma (Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2004; Koinis Mitchell & Murdock, 2005). A definition and conceptual model of asthma-related resilience for urban children has been described and tested (Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2004). This work has concentrated on testing the cumulative risk model and its association with asthma morbidity or has identified one protective factor (e.g., adaptability) associated with optimal asthma-related functioning. There is a paucity of pediatric research that applies a resilience-based approach to understand the multiple strengths that ethnic minority children and families utilize to manage illness effectively. Such approaches can also be applied to other chronic disease groups, where disparities in outcomes are often observed. Recent research including urban adolescents with sickle cell disease has shown that higher levels of self-esteem was associated with less depression and anxiety (Simon, Barakat, Patterson, & Dampier, 2009).

Multilevel Protective Factors: Individual-Level Factors

Protective factors that minimize asthma morbidity may occur across multiple levels including the individual level (e.g., child-related characteristic such as IQ), family/cultural level (e.g., ethnic identity), and may represent illness-specific processes (e.g., family management of asthma). The use of multidimensional models characterizing children and families’ attributes at different levels of functioning (Luthar et al., 2000) are needed, as some children and families may manifest competence in some domains, but exhibit problems in other areas. Many studies have identified child characteristics that may promote psychosocial competence (Luthar et al., 2000). Additional individual processes, such as measures of intelligence and attitudes toward school, may also relate to positive management behaviors of illness, such as asthma. For instance, children’s intelligence has been linked to accurate recognition of lung function (Fritz et al., 1996). Positive attitudes toward school may be associated with optimal health behaviors and indicative of greater flexibility to comply with treatment recommendations in school (Masten, 2001).

Family and Cultural-Level Processes

Few studies have focused on family or cultural-related processes, which protect children from experiencing morbidity. This is a critical limitation given current state of the art guidelines for asthma treatment still fall short in meeting the needs of different ethnic groups. Relying on children and families’ ethnic group status as a central way of describing cultural background provides little meaning about the family’s beliefs, characteristics or behaviors that may affect illness management. For example, although there is much heterogeneity within Latino subgroups, many families ascribe to an allocentric orientation, where a high value is placed on relationship building (Triandis, 2001). Family connectedness is a central dimension of family functioning and an aspect of family cohesion, reflecting a collectivistic family orientation (Gil & Vega, 1996; Olson, 2000). Given that asthma is managed in the context of the family (e.g., McQuaid, Walders, Kopel, Fritz, & Klinnert, 2005), developing strategies to enhance family connectedness with regard to specific treatment behaviors may help families feel more comfortable with managing asthma (e.g., caregivers can support children taking their medications), thereby decreasing asthma morbidity.

Furthermore, many children and families have much pride in maintaining aspects of their cultural background in their daily life and rituals. One aspect of ethnicity posited to be associated with optimal mental health is ethnic identity, or one’s subjective sense of ethnic group membership (Phinney & Alipuria, 1996). Associations between ethnic identity and more optimal child health behaviors have been shown. Among Mexican-American children, ethnic identity is associated with lower rates of high-risk health behaviors, such as drug and alcohol use (Love, Yin, Codina, & Zapata, 2006). It may be that a strong sense of ethnic identity is a proxy for maintaining an aspect of one’s heritage in daily life, which may contribute to better mental health (Alegria et al., 2004). For some families, this may be challenged by the pressure to acculturate to mainstream culture. It is unclear the extent to which ethnic identity may be associated with asthma morbidity. It is worthy of investigation given that many families manage asthma in the context of the acculturation process and negotiate the health care system in the Mainland United States.

Illness-specific Processes

Illness-specific protective processes that predict positive asthma outcomes may also inform strength-based, treatment approaches with children and families. Two potential processes that may be particular relevant for children with asthma include family asthma management and asthma self-efficacy. Family routines around asthma management predict asthma morbidity over and above measures of adherence alone (McQuaid et al., 2005). Family asthma management is also positively related to asthma self-efficacy, or one’s belief in the ability to effectively execute management behaviors (McQuaid et al., 2005). Higher levels of asthma self-efficacy may also predict asthma morbidity (Grus et al., 2001) and may be amenable to change with educational intervention (Guevara, 2003).

The Current Study

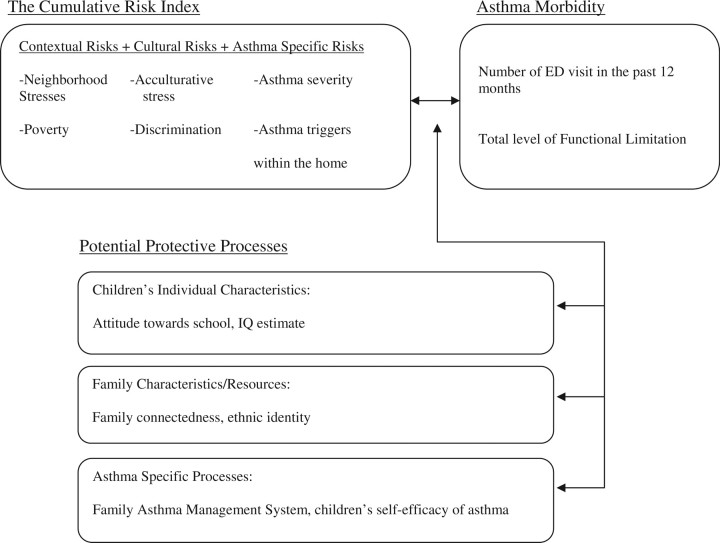

The current study identified multilevel protective factors associated with decreased asthma morbidity in children, in the context of multiple urban risks, using a resilience-based, conceptual model depicted in Figure 1. A CRI score was used to indicate the number and severity of risks urban families face (Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2007). We evaluated individual (e.g., IQ estimate, attitude toward school), family/cultural (e.g., family connectedness, ethnic identity) and illness-related (e.g., family asthma management, asthma self-efficacy) protective factors that may minimize asthma morbidity and buffer exposure to risks (Figure 1). We also identified whether these factors function as resource factors, as they may also be worthy of attention in urban children who face high risks (Luthar et al., 2000). Two indicators of asthma morbidity were used; ED visits due to asthma and asthma-related functional limitation (NHLBI, 2007). Each are indicative of poor asthma control; however, represent different aspects of asthma morbidity that are important to monitor and can affect a child’s overall health status.

Figure 1.

Risk and resilience-based model of asthma morbidity in children: identifying protective factors in urban children with asthma.

In comparison to our previous work, the current study includes a larger sample of urban children from three ethnic groups. In addition, multilevel protective factors potentially associated with asthma morbidity were tested in the context of cumulative risks associated with urban poverty and illness status. Associations were tested among families from Latino (Dominican and Puerto Rican), African-American, and NLW backgrounds. The inclusion of these processes was based on literature noting their relevance for children with asthma and children from specific ethnic minority backgrounds. We hypothesized that the individual and illness-related processes would exert a protective effect in their association with decreased morbidity, in the face of urban risk for all children, regardless of ethnic background. We expected that the cultural/family processes would exert a protective effect in African American and Latino children only, to decrease morbidity in the face of risks, given that these processes may be more salient for families from these ethnic backgrounds.

Method

Design and Procedure

The data reported herein are part of a larger study examining risk and resilience factors related to asthma outcomes in children (Everhart et al., 2011). Recruitment occurred in a hospital-based ambulatory pediatric clinic, community primary care clinics, a hospital-based asthma educational program, schools, and school-based community events. Caregivers of children with asthma signed a “consent to contact form” allowing study staff to contact them by telephone to screen for study eligibility. Families included in the study met the following eligibility criteria: child was between 6- and 13-years old, child’s legal guardian was willing to participate; parent ethnicity was self-identified as Latino, NLW, or AA; family resided in one of five selected urban zip codes; and child had physician-diagnosed asthma, breathing problems in the last 12 months, and was currently receiving treatment for asthma, as reported by parent. Exclusionary criteria included moderate to severe cognitive impairment as determined by school placement; exercise-induced asthma; and foster care placement. Of the 375 caregivers who indicated interest in the study by signing a “consent to contact” form, at screening, 35% were still interested and eligible to participate. The remaining families did not meet eligibility criteria, were unreachable due to disconnected numbers, or were not interested or unable to participate in the study. This resulted in a total of 149 enrollees, of which 59 were Latino, 49 were NLW and 41 were AA. Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of a children’s hospital in Providence, Rhode Island.

Data collection for the study occurred during two research visits within a 2-week time frame, either at a hospital-based research lab or in participants’ homes, based upon family preference. Children and their primary caregivers participated in separate, interview-based assessments. All research materials and procedures were translated into Spanish using standard procedures administered in our previous research (Canino & Bravo, 1994). Participants were offered the option of completing the research protocol in English or Spanish. All research assistants were fluent Spanish speakers, and the majority were native speakers. Monetary compensation was provided.

Measures

Participant Characteristics

Primary caregivers provided basic demographic information including the participating child’s age and gender, family income, and parent and child ethnicity. Poverty status was determined by dividing the family’s annual income by the Federal poverty threshold for a family of that size (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2005).

Asthma Control

Parents and children completed the Asthma Control Test (ACT; Nathan et al., 2004), a well-validated questionnaire of asthma-related impairment commonly used in the classification of asthma severity. For children below the age of 12 years, four items were completed by the child, and three additional items completed by the parent. Children 12- or 13-years old independently completed five items. Using standardized scoring procedures (Nathan et al., 2004) children were categorized as having “poor control” of their asthma or were classified as being in “good control” (Schatz et al., 2006).

Asthma Morbidity

Two well-established indicators of asthma morbidity outcomes were used; functional limitation due to asthma and whether or not the child experienced an ED visit in the past 12 months. The extent of functional limitation (e.g., frequency of asthma episodes, the level of impairment during an attack) due to the child’s asthma was assessed by the caregiver by six items from an established measure (Rosier et al., 1994). Parents also reported the number of ED visits their child had for asthma in the previous year. Responses options were “0” if the child had not been to the ED, or “1” if the child had one or more visits to the ED over the previous 12 months. This questionnaire has been widely used in studies with diverse, urban families (e.g., Canino et al., 2009; Esteban et al., 2009) and had good to excellent validity in US Latino, African American and NLW children with asthma has been demonstrated (McQuaid et al., 2005). Internal consistency has been good to excellent, with Cronbach’s α’s ranging from .72 to .92 (Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2007; Rosier et al., 1994).

Protective Factors: Individual-Level Protective Factors

IQ Estimate

An estimate of children’s intellectual functioning level was calculated using the Matrices subtest of the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test: Second Edition (KBIT-2; Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990), which assesses the child’s nonverbal flexibility and reasoning. No norms have been created for Latino children. A psychometric comparison indicated no differences between Latino and non-Latino white children (Hernández & Wilson, 1992).

Attitude Toward School

The 10-item “attitude towards school” subscale from the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992) was administered to children (Self-Report of Personality; SRP) to assess their overall opinion of the value of school as well as their level of ease with academic matters. The BASC yields T-scores and percentile ranks relative to a representative national norm group. The internal consistencies of these SRP scores have been assessed in a diverse sample (Cronbach’s α = .81 for this subscale for children; Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2004).

Family/Cultural-Level Protective Factors

Family Connectedness

One subscale of the Eco-cultural Family Interview (EFI; Weisner, 2002; Weisner, Coots, Bernheimer, & Nihira, 1997) assessed caregiver report of levels of family connectedness. The EFI is an open-ended, semi-structured interview that assesses family adaptation, family resources, and daily routines (such as meals, school, work, time together). Questions are organized into 10 domains (e.g., home environment, family connectedness, exposure to culturally consistent social networks). The EFI has been used in longitudinal and comparison studies of family functioning, and domains have demonstrated concurrent validity with AA and Latino samples (Weisner, 2002; Weisner et al., 1997). Trained research assistants administered and coded interviews according to the established guidelines. Reliability among interviewers was established and maintained via ongoing consensus meetings. Internal consistency for the family connectedness scale was somewhat low (Cronbach’s α = 0.5); however, the measure was retained because of the relevance of family connectedness as a potential protective factor for urban families.

Ethnic Identity

To assess ethnic identity, primary caregivers were asked, “How closely do you identify with other people from the same ethnic origin as yourself?” Respondents rated their self-perceived ethnic identity on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = very closely to 4 = not at all). This item was used in the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS; Alegria et al., 2004). Its validity has been demonstrated in research linking ethnic identity and cultural stress to mental health outcomes (e.g., Pérez, Fortuna, & Alegria, 2008).

Illness-Related Protective Factors

Family Asthma Management

The Family Asthma Management System Scale (FAMSS) consists of open-ended questions tapping eight domains of family asthma management (e.g., family’s response to asthma exacerbations). Parent and children are interviewed together by a research assistant, who codes the interview across each dimension according to standardized procedures (McQuaid et al., 2005). The FAMSS interview has demonstrated reliability and validity (McQuaid et al., 2005) and has been noted to be a well-established evidence-based assessment of family regimen adherence (Quittner et al., 2008). For this study, we used the FAMSS total score, a global indicator of the extent to which families have adaptive asthma management practices.

Asthma Self-Efficacy

Child asthma self-efficacy was assessed using the Asthma Self Efficacy Scale, a well-validated measure (Bursch, Schwankovsky, Gilbert, & Zeiger, 1999) assessing children’s perceived level of confidence in managing various situations relating to asthma management. The Attack Management subscale (the mean of six items) was selected for this study, which had fair internal consistency in our sample (α = .6).

Construction of the Multidimensional CRI

A CRI score was calculated for each case according to previously established procedures (Barocas, Seifer, & Sameroff, 1985; Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2007). A dichotomous code of 0 or 1 was statistically determined for each of six risk factors. Families whose scores fell in the top 25% of the sample for a given continuous variable were considered to be in the high-risk group and assigned a score of 1. The rest were coded as 0 (not high risk). Codes across the six risk variables were summed to create a CRI score for each family. The CRI captures three dimensions of risk with demonstrated significance to children’s asthma morbidity (Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2007).

Cultural Dimension: Perceived Discrimination

Experiences of perceived discrimination were collected through parent report of responses to nine items that assess daily experiences of discrimination in the previous year (Jackson & Williams, 1995). Internal consistency of the measure in English (Cronbach’s α = .82–.90) and Spanish (Cronbach’s α = .80–.91) is excellent.

Acculturative Stress

The level of stress associated with acculturative experiences such as migration and language barriers was assessed using the Cultural Stress Scale (CSS; Cervantes, Padilla, & Salgado de Snyder, 1991), which evaluates stress associated with acculturation in the previous 12 months. This measure was administered to AA and Latino parent participants, and has demonstrated moderate to high internal validity for English (Cronbach’s α = .94) and Spanish (Cronbach’s α = .90) versions in our previous work (Canino et al., 2009).

Contextual/Environmental Dimension: Poverty Threshold

Federal definition of the poverty line was used to develop an income-to-needs ratio (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997) providing a per capita index comparing parent-reported household income to the federal estimate of minimally required expenditures based upon family size (U.S. DHHS, 2005).

Neighborhood Stress

The Neighborhood Unsafety Scale (Resnick et al., 1997) provided an estimate of stress associated with the child’s residential context over the previous year. High to moderate internal consistency for the English and Spanish versions has been demonstrated (Canino et al., 2009).

Asthma-Specific Dimension: Controller Medication Use

Parent report of whether or not the child was prescribed a daily asthma controller medication was rated as a dichotomous variable as a proxy for persistent or intermittent status.

Second Hand Smoke

The FAMSS interview included questions regarding children’s exposure to secondhand smoke in the home (McQuaid et al., 2005).

Analysis Plan

To gain a better understanding of the relative magnitude of risks faced by families in our study, and the impact of these risks on asthma functioning, we explored the number of risks families qualified for, by ethnic group. Next, we evaluated whether specific individual, illness-related, and family/cultural processes functioned as protective factors in their association with asthma outcomes in the face of urban risks using a standard approach involving testing the moderating role of each process (Luthar et al., 2000). This approach allows for identification of both resource (i.e., as indicated by a main effect) and protective factors (i.e., as indicated by an interaction effect), each of which is worthy of consideration, given this is a high-risk sample, and even a relatively small decrease in asthma morbidity is useful to inform clinical intervention. Using hierarchical regression analyses, the separate contribution of each protective process (e.g., ethnic identity) on asthma outcomes (e.g., functional limitation or ED visit in the past 12 months) was tested. For models including ED visit in the past 12 months as an outcome, logistic regression analyses were employed. Specifically, the CRI was entered into the regression equation first, to control for level of risk. In the second step, the potential protective process (i.e., indicating a main effect or that the process was a “resource factor”) was entered, followed by the interaction term of the CRI and that protective factor in the third step. Lastly, we sought to examine in further depth where the significant interaction effect resided (e.g., did the levels of protective process differ for individuals under low, medium, or high levels of cumulative risk?) (Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2004; Luthar et al., 2002). Analyses were conducted for the overall sample and separately by ethnic group. Described in detail below are the results for analyses indicating statistically significant protective or resource effects.

A p-level of .05 was used for all statistical tests. Effect sizes for analyses of variance were expressed as partial omega squared  , which are interpreted as small (.01), medium (.06) or large (.14) (Cohen, 1988). Chi-square effect sizes are expressed as Cramer’s Phi (ϕc), the interpretation of which is akin to a point-biserial correlation. Odds ratios are presented for logistic regression, and R2-adjusted for multiple regression results.

, which are interpreted as small (.01), medium (.06) or large (.14) (Cohen, 1988). Chi-square effect sizes are expressed as Cramer’s Phi (ϕc), the interpretation of which is akin to a point-biserial correlation. Odds ratios are presented for logistic regression, and R2-adjusted for multiple regression results.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Of the 149 enrollees, 131 completed the protocol and relevant assessments. Characteristics of the children in this sample appear in Table I. A total of 69% of the caregivers preferred to have the interview conducted in English and 32% preferred the interview in Spanish. More than half of the Latino and African American families lived below the poverty threshold (61% and 58%, respectively) as compared to 28% of NLW participants (χ2 = 12.4, p < .001, ϕc = .31). There were no significant group differences on daily asthma controller medication use or other participant characteristics.

Table I.

Participant Characteristics

| Demographic and Asthma Variables | Entire Sample | Latino | African-American | Non- Latino white | Ethnic Group Differences | Effect Size*** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Participants (n) | 131 | 51 | 33 | 47 | – | – |

| Age in years, M (SD) | 9.8 (1.6) | 9.7 (10.5) | 9.2 (10.3) | 9.1 (10.1) | F(2,128) = 1.2 |

= .00 = .00 |

| Sex (% male) | 58.5 | 61 | 54.5 | 53 | χ2 = 0.6 | ϕc = .07 |

| Below poverty threshold (%) | 51.1 | 61 | 58 | 28 | χ2 = 12.4** | ϕc = .31 |

| On a daily controller medication* (%) | 67.9 | 69 | 61 | 72 | χ2 = 1.2 | ϕc = .10 |

| Percent with poorly controlled asthma (asthma Control Test) | 20.6 | 28 | 31 | 23 | χ2 = .5 | ϕc = .07 |

*Indicator of asthma severity.

**p < .01.

***Partial omega squared ( ) is interpreted as small (.01), medium (.06) or large (.14) (Cohen, 1988). Chi-square effect sizes are expressed as Cramer’s Phi (ϕc), the interpretation of which is akin to a point-biserial correlation.

) is interpreted as small (.01), medium (.06) or large (.14) (Cohen, 1988). Chi-square effect sizes are expressed as Cramer’s Phi (ϕc), the interpretation of which is akin to a point-biserial correlation.

Associations between participant characteristics and asthma outcomes were examined. Children living below the poverty line had higher functional limitation scores (M = 1.64, SD = 0.81) relative to those living above [M = 1.18, SD = 0.65; F (1,127) = 12.3, p < .001;  = .08]. Child age, gender, controller medication use, and neighborhood safety scores were not related to either morbidity outcome. Demographic characteristics, such as poverty threshold, which also differed across ethnic groups, as described above, were included in the CRI and thus was accounted for in the analyses. Ethnic and/or racial group membership was not included as a demographic factor as the analytic approach involved examining relationships stratified by ethnic group. Asthma functional limitation was highly correlated with ED visits (Spearman’s ρ = .41, p < .001).

= .08]. Child age, gender, controller medication use, and neighborhood safety scores were not related to either morbidity outcome. Demographic characteristics, such as poverty threshold, which also differed across ethnic groups, as described above, were included in the CRI and thus was accounted for in the analyses. Ethnic and/or racial group membership was not included as a demographic factor as the analytic approach involved examining relationships stratified by ethnic group. Asthma functional limitation was highly correlated with ED visits (Spearman’s ρ = .41, p < .001).

Cumulative Risks and Asthma Outcomes

An examination of the number of risks that families qualified for was undertaken. The modal value for African American families was three risks, for which 39% of AA families qualified. The modal value for Latino families (29%) was two risks, and for NLW families (32%) was one risk.

For the overall sample, cumulative risks were associated with more functional limitation (r = .25, p < 01), and risk for an ED visit in the past 12 months (r = .16, p < .05). Analyses by ethnic group indicated that for AA and NLW families, higher levels of risk were associated with higher functional limitation due to asthma (r = .33, p < .05; r = .38, p < .01, respectively). For Latino families, higher levels of risk were associated with an increased likelihood for an ED visit in the past 12 months (r = .36, p < .01).

Identification of Resource/Protective Factors: Individual-Level Factors

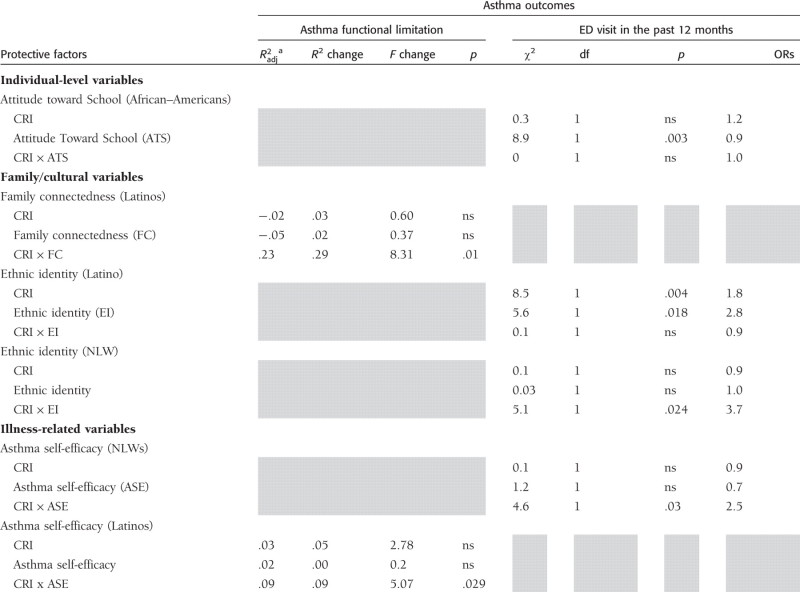

Results of regression models are presented in Table II. Contrary to our hypothesis, individual and illness-related processes exerted a protective or resource function for specific ethnic groups. We expected these processes to be important to children’s asthma outcomes, regardless of ethnic background. The potential resource and/or protective role of individual level processes, namely IQ estimate and attitudes toward school, were examined separately via hierarchical regression models including either asthma functional limitation or an ED visit in the past 12 months as the dependent outcome. Analyses revealed no effects for the sample as a whole, nor for the NLW and Latino subsamples. However, for the AA group, attitudes toward school emerged on the second step as a resource factor when considering ED visit in the past 12 months due to asthma (OR = 0.847, Wald = 5.19, p < .05; Table II). The interaction between CRI scores and attitudes toward school was not significant on the third step of this model.

Table II.

CRI, Protective Factors and ED Visit in the Past 12 and Functional Limitationa

|

Note. ASE=Asthma-Self Efficacy; ATS=Attitudes Toward School; EI=Ethnic Identity; FC=Family Connectedness; NLW=non-Latino white.

aModels with nonsignificant results are not shown.

Illness-Related Factors

In the analyses examining asthma self-efficacy and management of asthma within the family (Table II), neither process emerged as a protective or resource factor when considering either asthma outcome overall or within the AA group.

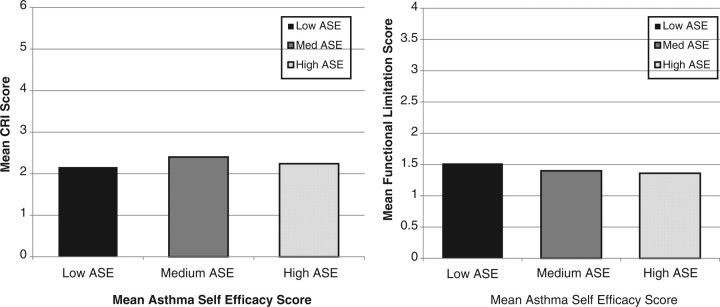

However, in the Latino group, children’s asthma management self-efficacy emerged as a potential protective factor in its association with asthma-related functional limitation. In the third step of the model, the interaction between cumulative risk and self-efficacy was significant ( = 09; β = − 1.7, t = −2.3, p < .05). Examining the nature of this interaction in further depth revealed that in the Latino group, the plot (Figure 2) reflecting mean CRI scores at low (n = 19), medium (n = 15), and high (n = 17) levels of asthma self-efficacy (ASE) showed the CRI scores were similar for families in the low (M = 2.16, SD = 1.54), middle (M = 2.40, SD = 1.55) and highest tertile groups (M = 2.24, SD = 1.56) [F (2,48) < 1.0]. Mean functional limitation scores within each ASE tertile (Figure 2) show that functional limitation scores for children in the low (M = 1.52, SD = 0.75) tertile of asthma self-efficacy were slightly higher as compared to the mean score in children in the middle (M = 1.4, SD = 0.81) and highest (M = 1.36, SD = 0.93) tertiles [F (2,48) < 1.0].

= 09; β = − 1.7, t = −2.3, p < .05). Examining the nature of this interaction in further depth revealed that in the Latino group, the plot (Figure 2) reflecting mean CRI scores at low (n = 19), medium (n = 15), and high (n = 17) levels of asthma self-efficacy (ASE) showed the CRI scores were similar for families in the low (M = 2.16, SD = 1.54), middle (M = 2.40, SD = 1.55) and highest tertile groups (M = 2.24, SD = 1.56) [F (2,48) < 1.0]. Mean functional limitation scores within each ASE tertile (Figure 2) show that functional limitation scores for children in the low (M = 1.52, SD = 0.75) tertile of asthma self-efficacy were slightly higher as compared to the mean score in children in the middle (M = 1.4, SD = 0.81) and highest (M = 1.36, SD = 0.93) tertiles [F (2,48) < 1.0].

Figure 2.

CRI and asthma functional limitation, by low, medium and high asthma self-efficacy groups (Latinos).

Asthma management self-efficacy emerged as a significant protective factor in the NLWs with reference to an ED visit in the past 12 months. In the third step, there appeared to be a unique effect of self-efficacy risk for an ED visit (OR = 2.52, Wald = 3.6, p < .05).

Family/Cultural Level Factors

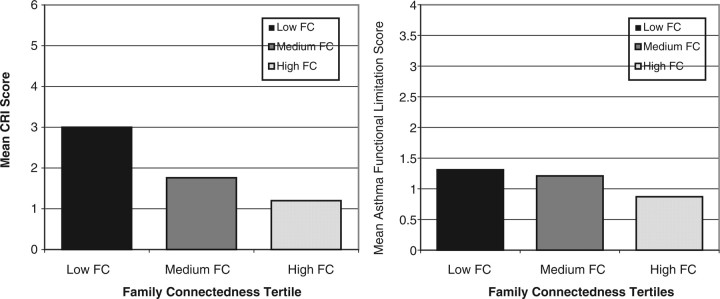

In the next set of analyses examining the role of family/cultural level processes (Table II), for Latinos, consistent with our hypothesis, the interaction between the CRI and family connectedness accounted for a significant portion of the variance in functional limitation ( = .23; β = −3.93, t = −2.9, p < .05).

= .23; β = −3.93, t = −2.9, p < .05).

A plot reflecting mean CRI scores at low (n = 9), medium (n = 18), and high (n = 5) levels of family connectedness (Figure 3) indicated that CRI scores were highest for Latino families in the lowest tertile on family connectedness (M = 3.0, SD = 1.22) and progressively lower for families in the middle (M = 1.78, SD = 1.00) and highest tertiles (M = 1.20, SD = 0.45) [F (2,28) = 6.15, p = .006;  = .2]. The mean functional limitation scores within each tertile indicate that scores for children in the low (M = 1.31, SD = 0.66) and middle (M = 1.21, SD = 0.72) tertiles of family connectedness were slightly higher as compared to the mean score in children in the highest family connectedness (M = 0.87, SD = 0.52) group [F (2,28) < 1.0].

= .2]. The mean functional limitation scores within each tertile indicate that scores for children in the low (M = 1.31, SD = 0.66) and middle (M = 1.21, SD = 0.72) tertiles of family connectedness were slightly higher as compared to the mean score in children in the highest family connectedness (M = 0.87, SD = 0.52) group [F (2,28) < 1.0].

Figure 3.

CRI and asthma functional limitation by family connectedness tertiles (Latinos).

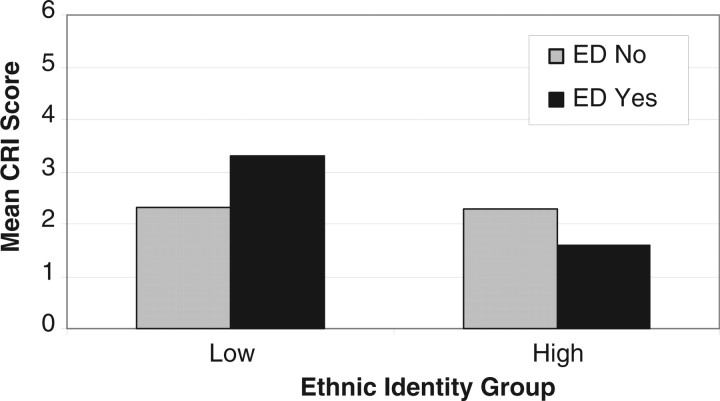

Furthermore, in the Latino group, ethnic identity emerged as a significant resource factor in the association with risk for an ED visit in the past 12 months in the past 12 months (OR = 2.8, Wald = 4.8, p < .05). The interaction between cumulative risk and ethnic identity in the third step was not significant.

Interestingly, ethnic identity emerged as a significant protective factor for NLWs, when considering risk for an ED visit in the past 12 months as the asthma outcome. In the third step, the interaction between the CRI and ethnic identity accounted for a significant portion of the variance in functional limitation (OR = 3.72, Wald = 3.9, p < .05). Graphical examination of the data suggest that the relationship between cumulative risk and ethnic identity is stronger in participants that had an asthma-related ED visit in the previous year versus those who had not (Figure 4). Ethnic identity was split into high (very closely related to others of same ethnicity) and low (somewhat to not at all closely identify) groups, then mean CRI scores for parent participants that had and had not been to the ED in the previous year were plotted within group. Across the two groups, mean CRI scores were the same for children that had not been to the ED (both means = 2.3) For participants who had been to the ED, mean CRI scores for children in the low identity group were higher than those with a stronger ethnic identity (M = 3.3 and 1.6, respectively) [F (1,9) = 10, p < .05].

Figure 4.

CRI and asthma-related ED visit in the past 12 months by high and low ethnic identity (NLW).

Additional Analyses

Given asthma control has been identified as an important indicator of asthma morbidity (NHLBI, 2007), we examined asthma control as an additional asthma outcome variable and found that for the most part, it was not associated with any of the resource and protective processes focused on in the current study. We did find that 21% of the children had poorly controlled asthma. Asthma control was also significantly associated with asthma functional limitation (Spearman’s ρ = −.37, p < .001) but not with ED visits in the previous 12 months (ρ = −.06, ns).

Discussion

Resilience-based approaches that have been utilized more often in the child development literature with respect to children’s psychosocial functioning can be applied to pediatric studies across illness groups. The current study applies a resilience-based approach to identify individual, illness-related, and family/cultural protective factors that may minimize asthma morbidity in the context of urban risks. Our findings focusing on the cumulative risks families face extend our previous work (Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2007), and suggest that risks related to urban poverty may differentially affect children’s asthma outcomes. Higher levels of cumulative risks were associated with more functional limitation for AA and NLW children. For Latino children, higher levels of risks increased the likelihood of children to experience an ED visit. Urban risks may exert a more proximal effect for some children in terms of illness-related impairment, while for other children and families, urban stress may be more likely to affect health care utilization (e.g., using the ED for primary care).

In terms of our analyses focused on identifying protective processes, even when controlling for cumulative risks, results suggested that some processes exerted a resource or protective function in the association with asthma morbidity. Urban children and families of this sample may access characteristics that can be utilized in the face of adversity to control asthma. Results showed more evidence of resource and protective factors by ethnic group (vs. the entire sample), although further study to replicate findings with larger samples is warranted.

In terms of the individual-based factors tested, for AA children in the sample, after controlling for cumulative risks, more positive attitudes toward school were associated with lower risk for experiencing an ED visit. It may be that these children had higher knowledge levels of asthma, or were more motivated to better care for their asthma.

When examining illness-specific processes, in the Latino group, children with higher levels of asthma self-efficacy tended to have lower levels of asthma-related functional limitation. An examination of the nature of this interaction suggests that despite facing the highest levels of poverty, Latino children in the sample may have used their confidence to manage asthma to limit the burden of illness on their daily activities. Surprisingly, more optimal levels of asthma management in the family context did not emerge as a resource or protective factor in its association with asthma functional limitation. It may be that inner city living presents obstacles (e.g., pests and mold in low income housing; limits to health care insurance) to positive asthma outcomes that are beyond the control of families, despite their best efforts.

When examining family and cultural processes, for the Latino group, higher levels of family connectedness exerted a protective function in the association with lower levels of asthma-related functional limitation. These preliminary findings suggest that family connections may be used to help support the management of asthma, in the context of daily stresses.

For the Latino group in our sample, caregivers’ report of a stronger ethnic identity was associated with a lower risk of experiencing an asthma ED visit in the past 12 months. Interestingly, in the NLW group, ethnic identity also had a protective effect on decreasing risk for an ED visit in the past 12 months. It may be that a strong sense of oneself in relation to one’s ethnicity is a proxy for pride in one’s culture and comfort level with being from a specific ethnic group in the context of the larger majority culture. It is possible that this may serve as a resource when managing stress related to asthma. The ethnic background of the caregivers in the NLW group was not known; however, caregivers may have been referring to their own cultural background when responding to this question on ethnic identity. This may provide preliminary evidence for the fact that some individuals regardless of ethnic background have a distinct culture and potentially use aspects of their cultural background to manage asthma. Finally, ethnic identity and family connectedness was not associated with minimal morbidity in the AA children of our sample, contrary to our hypothesis. Examination of the distribution of these data indicated a range of scores on these processes; however, it may be that the scores were not high enough to exert a “protective” effect on cumulative risks or high levels of morbidity.

Study Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Several limitations of this study should be considered and addressed in future research. Our sample size by ethnic group was small, which may have affected our ability to detect significant effects. The small sample size may have also contributed to the number of nonsignificant findings generated. In addition, multiple comparisons were made, and therefore, the clinical import of the results should be interpreted with caution. We acknowledge that we did not adjust for statistical bias introduced by multiple comparisons within each of the ethnic groups. Larger samples of urban children from specific African-American and Latino ethnic subgroups are needed in pediatric studies that apply strength-based approaches. Moreover, the cross-sectional design of this study poses limitations for testing important causal associations. We also acknowledge that there may be alternative explanations for study findings that were not included in this article. Furthermore, we did not assess directly whether differences in the caregiver’s choice to have the interview conducted in Spanish versus English affected the results of the study.

Additionally, we recognize that we did not use a traditional classification approach to asthma severity as recommended by established guidelines (National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, 2007). Rather, we relied on parent report of whether the child was prescribed a controller medication as a proxy of asthma severity. Furthermore, future studies testing resilience-based conceptual models with larger samples of urban children should utilize asthma control as an indicator of morbidity (NHLBI, 2007). It should also be noted that the participating families of this study were a convenience sample, which could have introduced sample bias on the study results. The classification approach for determining “risk status” in the construction of the CRI was sample dependent. Therefore, the “risk status” for children from different samples (rural vs. urban) may be different depending on the nature of risks faced. Lastly, our data were based on retrospective reports of asthma symptoms and ED utilization, which are subject to self-report bias and lack of precision.

As in our approach which considers the multiple urban risk factors families face, similar models including multiple protective processes may be developed and tested, given children and families may utilize and access many resources to manage asthma well. Furthermore, pediatric studies with larger urban samples that specify how risk and protective factors are defined and tested in the context of adversity are needed. These terms are often used without clear indication of how or why each process is considered a “risk” or a “protective” factor, and statistical support for the function of each process is not provided. Not all risks and protective factors will have a detrimental or buffering effect on all outcomes; therefore, a specific process found to be “protective” in enhancing a specific pediatric health outcome may not necessarily have the same effect on other health outcomes and with other pediatric populations.

The current study involves the inclusion of multilevel protective processes, particularly family and cultural-related processes and a strength-based, resilience approach. This is a departure from many pediatric studies including ethnic minority children, which tend to focus on risks related to poor health outcomes. Some resource and protective effects of specific processes in minimizing asthma morbidity were identified in the context of high levels of cumulative risks. Previous research has tended to consider one risk factor that families face (e.g., ethnic minority status) and has not considered protective factors that buffer exposure to multiple risks. Future research should test additional cultural protective processes not focused on in this research, such as the role of spirituality or the role of an alternative caregiver, which may be particularly helpful in coping with stress associated with managing a child’s chronic illness. These protective processes can be integrated into culturally tailored treatment approaches (e.g., using family connections and relationships for support in enhancing medication adherence; applying family-based vs. individualistic approaches to pediatric interventions) to enhance the pediatric health outcomes of specific ethnic groups.

Pediatric research that applies strength-based approaches provides an opportunity to describe the positive characteristics of high-risk families, and may demonstrate that despite facing some conditions that may be unalterable, there are many resources that can be utilized on a daily basis to manage illness effectively. Interventions that integrate family and cultural strengths that are commonly utilized (e.g., family connections) may enhance the comfort levels of participating families and may assist with decreasing stress associated with managing childhood illness in the context of daily stress.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (R03AI066260) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (R01 HD057220 to D.K.M).

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Alegria M, Vila D, Woo M, Canino G, Takeuchi D, Vera M, Febo V, Guarnaccia P, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Shrout P. Cultural relevance and equivalence in the NLAAS instrument: Integrating etic and emic in the development of cross-cultural measures for a psychiatric epidemiology and services study of Latinos. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(4):270–288. doi: 10.1002/mpr.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barocas R, Seifer R, Sameroff A J. Defining environmental risk: Multiple dimensions of pscyhological vulnerability. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1985;13(4):433–447. doi: 10.1007/BF00911218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursch B, Schwankovsky L, Gilbert J, Zeiger R. Construction and validation of four childhood asthma self-management scales: Parent barriers, child and parent self-efficacy, and parent belief in treatment efficacy. Journal of Asthma. 1999;36(1):115–128. doi: 10.3109/02770909909065155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Bravo M. The adaptation and testing of diagnostic and outcome measures for cross-cultural research. International Review of Psychiatry. 1994;6:281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Koinis-Mitchell D, Ortega A, McQuaid E, Fritz G, Alegria M. Asthma disparities in the prevalence, morbidity and treatment of Latino children. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;63(11):2926–2937. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, McQuaid E L, Alvarez M, Colon A, Esteban C, Febo V, Klein R B, Mitchell D K, Kopel S J, Montealegre F, Ortega A N, Rodriguez-Santana J, Seifer R, Fritz G K. Issues and methods in disparities research: The Rhode Island-Puerto Rico asthma center. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2009;44(9):899–908. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. 2007. Asthma Prevalence, Health Care Use and Mortality: United States, 2003-05. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/ashtma03-05/asthma03-05.htm.

- Cervantes R, Padilla A, Salgado de Snyder W. The Hispanic Stress Inventory: A culturally relevant approach to psychological assessment. Psychological Assessment. 1991;3:438–447. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan G J, Brooks-Gunn J. Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russel Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Esteban C A, Klein R B, McQuaid E L, Fritz G K, Seifer R, Kopel S J, Santana J R, Colon A, Alvarez M, Koinis-Mitchell D, Ortega A N, Martinez-Nieves B, Canino G. Conundrums in childhood asthma severity, control, and health care use: Puerto Rico versus Rhode Island. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2009;124(2):238–244.e235. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everhart R, Fiese B, Smyth J. A cumulative risk model predicting caregiver quality of life in pediatric asthma. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33(8):809–818. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everhart R, Kopel S, McQuaid E L, Salcedo L, York D, Potter C, Koinis-Mitchell D. Differences in environmental control and asthma outcomes among Latino, African American, and non-Latino White families. Pediatric Allergy, Immunology, and Pulmonology. 2011;24(3):165–169. doi: 10.1089/ped.2011.0081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz G, McQuaid E, Spirito A, Klein R. Symptom perception in pediatric asthma: Relationship to functional morbidity and psychological factors. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1033–1041. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199608000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil A, Vega W. Two different worlds: Acculturation stress and adaptation among Cuban and Nicaraguan families. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1996;13(3):435–456. [Google Scholar]

- Grus C L, Lopez-Hernandez C, Delameter A, Appelgate B, Brito A, Wurm G, Wanner A. Parental self-efficacy and morbidity in pediatric asthma. Journal of Asthma. 2001;(38):99–106. doi: 10.1081/jas-100000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara J P. Self-management education of children with asthma: A meta-analysis. LDI Issue Brief. 2003;9(3):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser S T, Allen J P, Golden E. Out of the woods: Tales of resilient teens. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández A E, Wilson V. A comparison of Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children: Reliability for Mexican-Americans and non-Hispanic Whites. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1992;14(3):394–397. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J, Williams D. Detroit Area Study, 1995: Social influence on health: Stress, racism, and health protective resources. 1995 University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman A, Kaufman N. The Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test: Educational Testing Service. 1990 [Google Scholar]

- Klinnert M, McQuaid E, Gavin L. Assessing the Family Asthma Management System. Journal of Asthma. 1997;34(1):77–88. doi: 10.3109/02770909709071206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koinis-Mitchell D, McQauid E L, Kopel S, Esteban C, Ortega A, Seifer R, Garcia-Coll C, Klein R, Cespedes E, Canino G, Fritz G K. Cultural-related, contextual, and asthma-specific risks associated with asthma morbidity in urban children. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2009;17:38–48. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9178-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koinis-Mitchell D, Adams S K, Murdock K K. Associations among risk factors, individual resources, and indices of school-related asthma morbidity in Urban, school-aged children: A pilot study. Journal of School Health. 2005;75(10):363–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koinis-Mitchell D, McQuaid E, Seifer R, Kopel S, Esteban C, Canino G, Garcia-Coll C, Klein R, Fritz G. Multiple urban and asthma-related risks and their association with asthma morbidity in children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(5):582–595. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koinis-Mitchell D, McQuaid E L, Friedman D, Colon A, Soto J, Rivera D V, Fritz G K, Canino G. Latino caregivers' beliefs about asthma: Causes, symptoms, and practices. Journal of Asthma. 2008;45(3):205–210. doi: 10.1080/02770900801890422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koinis-Mitchell D, Murdock K M, McQuaid E L. Risk and resilience in urban children with asthma: A conceptual model and exploratory study. Children's Health Care. 2004;33(4):275–298. [Google Scholar]

- Lara M, Akinbami L, Flores G, Morgenstern H. Heterogeneity of childhood asthma among Hispanic children: Puerto Rican children bear a disproportionate burden. Pediatrics. 2006;117:43–53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love A, Yin Z, Codina E, Zapata J. Ethnic identity and risky health behaviors in school-age Mexican-American children. Psychological Reports. 2006;98:735–744. doi: 10.2466/pr0.98.3.735-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S S, Brown P J. Maximizing resilience through diverse levels of inquiry: Prevailing paradigms, possibilities, and priorities for the future. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19(3):931–955. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407000454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar S S, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71(3):543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A S. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist. 2001;56(3):227–238. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid E, Walders N, Kopel S, Fritz G, Klinnert M. Pediatric asthma management in the family context: The family asthma management system scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:492–502. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid E L, Vasquez J, Canino G, Fritz G K, Ortega A N, Colon A, Klein R B, Kopel S J, Koinis-Mitchell D, Esteban C A, Seifer R. Beliefs and barriers to medication use in parents of Latino children with asthma. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2009;44:892–898. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan R A, Sorkness C A, Kosinski M, Schatz M, Li J T, Marcus P, Murray J J, Pendergraft T B. Development of the asthma control test: A survey for assessing asthma control. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 2004;113(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. 2007. Retrieved. from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthsumm.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Olson D H. Circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy. 2000;22:144–167. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J, Alipuria L. At the interface of cultures: Multi-ethnic/multiracial high school and college students. Journal of Social Psychology. 1996;136:139–158. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1996.9713988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quittner A L, Modi AC, Lemanek K, Landis C, Rapoff M. Evidence-Based Assessment of Adherence to Medical Treatments in Pediatric Psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:916–936. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand C S, Butz A M, Kolodner K, Huss K, Eggleston P, Malveaux F. Emergency department visits by urban African American children with asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2000;105(1 Pt 1):83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(00)90182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick M, Bearman P, Blum R, Bauman K, Harris K, Jones J, Tabor J, Beuhring T, Sieving R, Shew M, Ireland M, Bearinger L, Udry J. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings in the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(10):823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds C K, Kamphaus . The Behavior Assessment System for Children. Circle Pines, Minesota: American Guidance Service, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Rosier M J, Bishop J, Nolan T, Robertson C F, Carlin J B, Phelan P D. Measurement of functional severity of asthma in children. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1994;149(6):1434–1441. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.6.8004295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz M, Sorkness C A, Li J T, Marcus P, Murray J J, Nathan R A, Kosinski M, Pendergraft T B, Jhingran P. Asthma control test: Reliability, validity, and responsiveness in patients not previously followed by asthma specialists. Journal of clinical Immunology. 2006;117(3):549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon K, Barakat L P, Patterson C A, Dampier C. Symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescents with sickle cell disease: The role of intrapersonal characteristics and stress processing variables. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2009;40:317–330. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis H C. Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality. 2001;69(6):907–924. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.696169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The 2005 HHS Poverty Guidelines. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner T S. Ecocultural understanding of children's developmental pathways. Human Development. 2002;45(4):275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner T S, Coots L J, Bernheimer L P, Nihira K. The ecocultural family interview manual: Volume 1. Los Angeles, CA: University of California, Los Angeles; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wright R, Finn P, Contreras J, Cohen S, Wright R, Staudenmayer J, Wand M, Perkins D, Weiss S, Gold DR. Chronic caregiver stress and IgE expression, allergen-induced proliferation, and cytokine profiles in a birth cohort predisposed to atopy. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2004;113(6):1051–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]