Abstract

The highly conserved epidermal growth factor receptor (Egfr) pathway is required in all animals for normal development and homeostasis; consequently, aberrant Egfr signaling is implicated in a number of diseases. Genetic analysis of Drosophila melanogaster Egfr has contributed significantly to understanding this conserved pathway and led to the discovery of new components and targets. Here we used microarray analysis of third instar wing discs, in which Egfr signaling was perturbed, to identify new Egfr-responsive genes. Upregulated transcripts included five known targets, suggesting the approach was valid. We investigated the function of 29 previously uncharacterized genes, which had pronounced responses. The Egfr pathway is important for wing-vein patterning and using reverse genetic analysis we identified five genes that showed venation defects. Three of these genes are expressed in vein primordia and all showed transcriptional changes in response to altered Egfr activity consistent with being targets of the pathway. Genetic interactions with Egfr further linked two of the genes, Sulfated (Sulf1), an endosulfatase gene, and CG4096, an A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase with ThromboSpondin motifs (ADAMTS) gene, to the pathway. Sulf1 showed a strong genetic interaction with the neuregulin-like ligand vein (vn) and may influence binding of Vn to heparan-sulfated proteoglycans (HSPGs). How Drosophila Egfr activity is modulated by CG4096 is unknown, but interestingly vertebrate EGF ligands are regulated by a related ADAMTS protein. We suggest Sulf1 and CG4096 are negative feedback regulators of Egfr signaling that function in the extracellular space to influence ligand activity.

Keywords: Egfr, microarray, Drosophila, wing disc, Sulf1, CG4096, feedback regulation

THE epidermal growth factor receptor (Egfr) pathway is required for cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, and survival during development (reviewed for Drosophila in Shilo 2005). Drosophila Egfr is activated by four ligands: three in the TGF-α family, spitz (spi), gurken (grk), and keren (krn) and a neuregulin called vein (vn). The pathway is controlled by multiple regulatory mechanisms that can either dampen or amplify the signal. Components of these regulatory mechanisms include transcriptional targets of the signaling pathway and thus serve as negative and positive feedback loops (reviewed in Avraham and Yarden 2011). Negative feedback regulators include argos (aos) (Schweitzer et al. 1995; Golembo et al. 1996; Klein et al. 2004), sprouty (sty) (Casci et al. 1999), kekkon-1 (Ghiglione et al. 1999), MAPK Phosphatase 3 (Mkp3) (Kim et al. 2003; Gomez et al. 2005), mae (Vivekanand et al. 2004), and d-Cbl (Pai et al. 2000). Positive feedback regulators include the two Egfr activating ligands, vn (Wasserman and Freeman 1998; Golembo et al. 1999; Wessells et al. 1999; Wang et al. 2000) and spi (Wasserman and Freeman 1998), pointed (pnt) (Gabay et al. 1996), and a miRNA, miR7, which positively regulates the pathway by targeting the transcriptional repressor yan (Li and Carthew 2005). Here we provide genetic evidence for two new feedback controls, which both function as negative regulators of Egfr signaling in the wing imaginal disc.

The Drosophila wing has proved to be a good model system to study Egfr signaling because Egfr is required for specifying the stereotypical pattern of veins separated by interveins in this tissue. A prepattern of the veins is apparent in the mature third instar imaginal disc and can be visualized, for example, by rhomboid (rho) expression (Sturtevant et al. 1993). Rho is required to process the TGF-α ligands to an active form and flies mutant for both rho and the neuregulin-like ligand vn lack all veins (Sturtevant and Bier 1995; Urban et al. 2001, 2002). In contrast to the loss of vein phenotypes seen when Egfr signaling is reduced, excessive Egfr signaling leads to extra-vein phenotypes. In the third instar wing disc, vn is expressed along the anterior–posterior boundary in the central intervein territory, where it is required for specifying the flanking longitudinal veins (3 and 4), especially vein 4 (Simcox et al. 1996). vn expression is induced by Hedgehog signaling (Wessells et al. 1999), and indeed in addition to the Egfr pathway, the Hh, Dpp, Wingless, and Notch signaling pathways are required for positioning veins and determining their thickness (reviewed in Blair 2007).

There have been multiple genetic screens for venation mutants leading to the discovery of new components in these signaling pathways. Screening is facilitated because the wing, like the eye, is dispensable for viability and has a stereotypical pattern that can be easily scored for changes. Here, rather than conducting another genetic screen, we employed a microarray-based approach to first identify Egfr-responsive genes. We then tested the function of candidate target genes, using reverse genetics. With this approach we hoped to find novel genes that were targets of the pathway but that would not necessarily be discovered in genetic screens because they had either pleiotropic roles causing early death or only small phenotypic effects. We discovered five genes with venation defects and further genetic tests suggested that two of these, Sulfated (Sulf1) and CG4096, act as negative regulators of the Egfr pathway. The results provide more evidence for the elaborate controls that ensure precise regulation of signaling pathways. They also provide an example of genes that contribute a relatively fine control that when disrupted have only subtle effects. This work exemplifies the use of transcriptional profiling as a first line of screening, which can then be followed by reverse genetics to discover new genes in a given pathway.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila stocks

The following gene alleles and transgenes were used: vnL6, vnddd3, spi1, Egfr3F18, krn27, pntΔ88, Ras85De1B, UAS-vn1.1, UAS-Dcr-2, EgfrElp, 71B-GAL4, Act5C-GAL4, en-GAL4, sd-GAL4, tsh-GAL4, and vn-GAL4 (C. L. Austin, unpublished data). Most RNAi transgenes were from the KK or GD collections at the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC) (http://stockcenter.vdrc.at/control/main). CG31048RNAi was from the TRIP collection available at the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. Additional transgenes generated here are described below. GAL4-UAS crosses were carried out at 17°, 25°, and 29° to provide a range of GAL4 activity levels. Trangenes for Sulf1 were generated as part of this study and also obtained from Hiroshi Nakato: UAS-Sulf1, UAS-Sulf1-Golgi, and UAS-Sulf1-ER (Kleinschmit et al. 2010). The source of a Sulf1 transgene used in a given experiment is indicated in the text.

Microarray processing and analysis

RNA was extracted from third instar wing discs dissected from 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrACT and 71B-Gal4; UAS EgfrDN larvae, with ∼200 larvae for each genotype. RNA quality was preserved by placing dissected wing discs in groups of ∼10 directly into RLT buffer (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) on ice for subsequent RNA extractions. RNA samples were processed and hybridized to Drosophila Genome 1 Arrays (three arrays per genotype), using standard Affymetrix protocols at the Microarray Shared Resource of the Comprehensive Cancer Center at Ohio State University. The R environment (http://www.r-project.org) and BioConductor suite (Gentleman et al. 2004) (http://www.bioconductor.org) were used for all data analysis. Scanned image files were processed using the robust multiarray average (RMA) method (Bolstad et al. 2003) to normalize across data sets and to calculate expression values. Genes showing log2 expression values of ≥8.2 in either or both of the Egfr groups were retained for statistical analysis, as previous work (Butler et al. 2003) found the most reliable in situ hybridization results with genes expressed at these levels. Following this filtering, two-tailed t-tests were used to identify genes differentially expressed between the EgfrACT vs. EgfrDN groups. Differentially expressed transcripts were ranked by fold change to generate a working list for subsequent biological analyses.

In situ hybridization

RNA probes were generated by transcription of antisense RNA with T7 RNA polymerase (Roche) from plasmid templates with cDNA inserts from the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (DGRC) (https://dgrc.cgb.indiana.edu/) or from gene-specific PCR-generated templates. For PCR templates the 3′ primer for each gene had a T7 recognition sequence: GAATTTAATACGACTCACTATAGG. All hybridizations were carried out using a protocol involving proteinase K treatment of the tissues (Butler et al. 2003) or using a method with a higher hybridization temperature that does not include this step (Firth and Baker 2007).

Immunohistochemistry

Late third instar wing discs were stained for dpERK with rabbit anti-dpERK antibody (Cell Signaling) (Gabay et al. 1997), using methods described in Coppey et al. (2008). Primary antibody was used at 1:250 dilution and Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) was used at 1:1000 dilution for detection. Samples were mounted in VECTASHIELD (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and imaged using a Nikon C90i confocal microscope.

Transgenes

We generated transgenes for ectopic expression of Sulf1 and CG6234. All transgenes were cloned into pUAST and transgenic flies were generated using standard P-element transformation. Three or more lines were generated and examined for each gene. Sulf1, the Drosophila Gold Collection (DGC) cDNA clone SD04414 that was used to make this construct, lacks the first 315 bp of coding sequence. Genomic PCR was used to generate the missing sequence, which was combined by overlapping PCR with the cDNA clone to give the full coding sequence. CG6234, an XhoI fragment comprising the entire cDNA of the gene, was excised from the DGC cDNA LP04345 clone.

RT-PCR

S2 and S2-DER cells (Schweitzer et al. 1995) were treated for 7 h with CuSO4 at a final concentration of 700 µM to induce Egfr expression in the S2-DER cells. Controls were mock treated with saline. Cells were harvested and total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy kit (QIAGEN) with an in-column DNase I treatment. RNA (2 µg) from each sample was subjected to reverse transcription (RT), using an Omniscript RT kit (QIAGEN). A fraction (1/10th) of the RT reaction was used as template for PCR reactions with gene-specific primers (25 cycles). Ornithine decarboxylase antizyme (Oda), which is expressed at similar levels in all cells, was used as a standard for comparison. Primers for each gene were as follows:

Heparin binding assay

Assays for ligand binding to heparin were performed as previously described (Klein et al. 2004). S2-Vn (Schnepp et al. 1998), S2-sSpi::GFP, and S2-sSpi::His cells (T. L. Jacobsen, unpublished data) were treated for 7 hr with CuSO4 at a final concentration of 700 µM to induce gene expression. The conditioned medium (7 ml) from each culture was concentrated (sevenfold) using a 10-kDa cutoff spin filter (Amicon, Beverly, MA). One microliter of this concentrate was incubated with 100 µl of agarose beads covalently linked to heparin [preequilibrated with dilution buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.2)] and incubated overnight at 4°. The beads were washed five times using low-salt buffer (50 mM NaCl in dilution buffer). Bound proteins were eluted with 50 µl of high-salt buffer (900 mM NaCl in dilution buffer) and samples were analyzed using Western blotting and probing with affinity-purified α-Vn antibody (Schnepp et al. 1996) or α-Spi (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) (Schweitzer et al. 1995) followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Each “input” lane contained 1/100th of the total volume that was added to the beads for binding. Each “bound” lane contained one-fifth of the total eluate from the high-salt wash.

Results

Transcriptome analysis of wing discs identified known and candidate Egfr-responsive genes

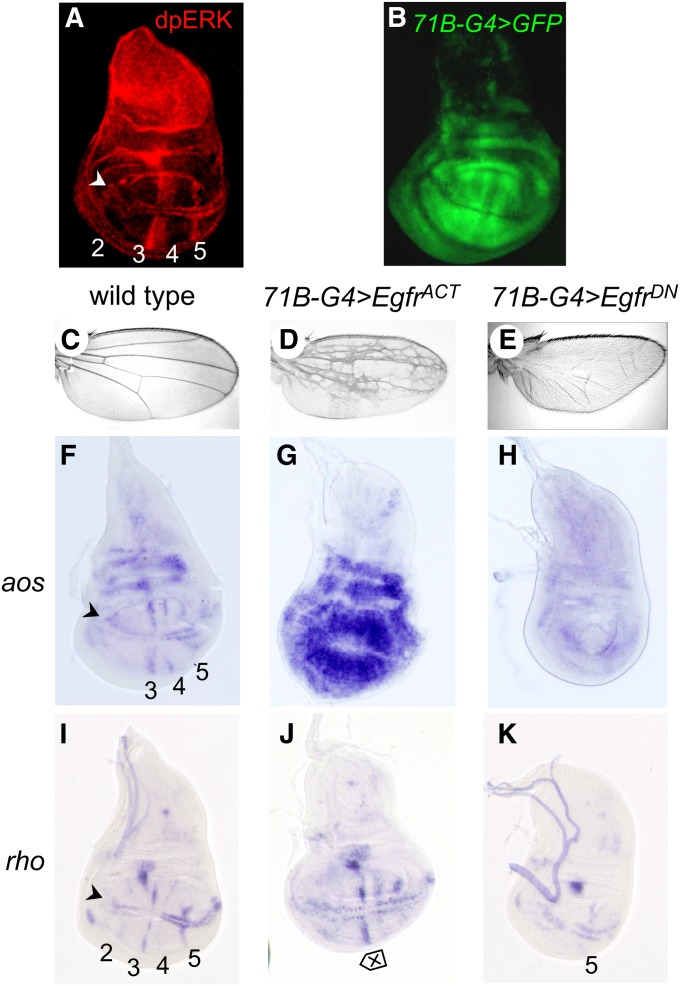

The 71B-GAL4 driver (Brand and Perrimon 1993) was used to induce expression of transgenes encoding either constitutively active (UAS-EgfrACT) (Queenan et al. 1997) or dominant negative (UAS-EgfrDN) (Buff et al. 1998) forms of Egfr in the wing disc (Figure 1, A–E). 71B-GAL4 is expressed throughout the wing pouch, with slight downregulation at the AP and DV boundaries (Figure 1B). This is broader than the normal domain of Egfr signaling in the wing pouch, which is limited to a series of stripes corresponding to the future veins and wing margin, as visualized by the pattern of dpErk expression (doubly phosphorylated Erk/MAPK; Figure 1A) (Gabay et al. 1997) or by the vein cell markers aos and rho (Figure 1, F and I). In response to altered signaling, the adult flies had vein-patterning defects; 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrACT flies had extra veins and 71B-Gal4; UAS EgfrDN flies had no veins (Figure 1, C–E).

Figure 1 .

Genotypes used in the microarray experiment. (A) Antibody (∝-dpErk) stain of third instar wing disc to show pattern of Erk/MAPK activation in longitudinal veins (2–5) and the wing margin (arrowhead). (B) 71B-GAL4; UAS-GFP third instar wing disc showing expression of GFP in the 71B pattern throughout most of the wing pouch and hinge regions of the disc. The expression is more extensive than that of dpErk (A). (C) Wild-type wing with stereotypical pattern of veins separated by intervein regions. (D) 71B-GAL4; UAS-EgfrACT wing displaying an extensive extra-vein pattern. (E) 71B-Gal4; UAS-EgfrDN wing displaying complete vein loss. (F–K) In situ hybridization with probes for indicated genes. (F–H) aos in wild type (F) showing expression in longitudinal veins (3–5) and the wing margin (arrowhead), 71B-GAL4; UAS-EgfrACT (G) showing expression throughout the wing pouch, and 71B-GAL4; UAS-EgfrDN (H) showing loss of expression in the wing pouch. (I–K) rho in wild type (I) showing expression in longitudinal veins (2–5) and the wing margin (arrowhead), 71B-GAL4; UAS-EgfrACT (J) showing slight expansion of vein width (double-headed arrow), and 71B-GAL4; UAS-EgfrDN (K) showing loss of expression in the wing pouch.

In addition to broad expression, we also chose 71B-GAL4 for this analysis because 71B-Gal4 expression is initiated at the early-late third instar. This ensures that the time between induction of the transgenes and harvesting at late-late third instar is only ∼48 hr (Wessells et al. 1999) (Supporting Information, Figure S1, A–C). The short time frame increases the likelihood that direct Egfr targets will be identified over genes that function farther downstream in the gene regulatory network. These latter genes would include those that are induced or repressed once cell-type reprogramming has occurred. Indeed, we found that aos, a known transcriptional target, was strongly and uniformly induced (Figure 1, F–H), whereas rho, a gene expressed in all cells of vein histotype, showed little induction by the time of harvesting (Figure 1, I–K).

Analysis of the microarray data identified a total of 162 transcripts that were expressed at significantly different levels (P ≤ 0.05) between the EgfrACT and EgfrDN samples. Table 1 shows the top 25 transcripts upregulated by EgfrACT, and Table 2 shows the top 25 transcripts upregulated by EgfrDN [the full set is shown in Table S1 and the primary data have been submitted to GEO (GSE34872)]. Eight of these genes were also identified in other studies that conducted whole-genome transcriptional analysis of the Egfr pathway or the Ras gene, which functions downstream of Egfr (Tables 1 and 2) (Asha et al. 2003; Jordan et al. 2005; Firth and Baker 2007). Five known target genes were also represented within the top group of 25 genes upregulated by Egfr: ventral veinless (vvl) (de Celis et al. 1995; Llimargas and Casanova 1997), sty (Hacohen et al. 1998; Casci et al. 1999), pnt (O’Neill et al. 1994; Gabay et al. 1996), MASK (Smith et al. 2002), and Mkp3 (Kim et al. 2003; Rintelen et al. 2003; Gomez et al. 2005). Finding differential expression of these known targets suggested that the experimental approach itself was sound and had the potential to identify novel targets.

Table 1. Genes upregulated in EgfrACT.

| Gene | Fold change | Molecular function (Egfr pathway?) | RNAi analysis | RNAi phenotype Act5C-GAL4 | Vein phenotype | Hit in Egfr/Ras microarray |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ImpE1 | 2.17 | Unknown | Yes | Lethal | ||

| vvl | 2 | POU domain TF (yes) | ||||

| sty | 1.87 | Unknown (yes) | ||||

| pnt | 1.82 | ETS TF (yes) | ||||

| CG34398 | 1.66 | Unknown | Yes | None | Vein loss (RNAi) | Firth and Baker (2007) |

| nyobe | 1.57 | PAN/Endoglin domains | Yes | Wings held out | ||

| MASK | 1.55 | RTK mediator (yes) | ||||

| Sulf1 | 1.53 | Endosulfatase | Yes | None | Vein loss (OE) | Firth and Baker (2007) |

| tou | 1.41 | Chromatin structure | ||||

| corto | 1.39 | Polycomb interactions | ||||

| qkr58E-1 | 1.38 | RNA binding | ||||

| bel | 1.37 | DEAD box helicase | Firth and Baker (2007) | |||

| Ect3 | 1.36 | β-Galactosidase | ||||

| CG5326 | 1.34 | Fatty acid elongation | Yes | None | ||

| salm | 1.33 | Zinc finger TF | ||||

| CG4096 | 1.32 | ADAMTS | Yes | Extra vein | Extra vein (RNAi) | Firth and Baker (2007) |

| pk | 1.32 | PET LIM domain | ||||

| Cypl | 1.31 | Isomerase | Yes | Young adult lethal | ||

| CG5800 | 1.3 | DEAD box helicase | Yes | Lethal | ||

| egg | 1.29 | Methyltransferase | ||||

| CG6234 | 1.29 | Unknown, predicted transmembrane | Yes | Lethal | Extra vein (OE) | |

| CG3857 | 1.28 | Unknown | Yes | Lethal | ||

| eIF5B | 1.27 | Translation initiation factor | ||||

| CG31048 | 1.27 | GEF | Yes | None | ||

| Mkp3 | 1.26 | MAPK phosphatase (yes) |

OE, overexpression; TF, transcription factor.

Table 2. Genes upregulated in EgfrDN.

| Gene | Fold change | Molecular function | RNAi analysis | RNAi phenotype Act5C-GAL4 | Vein phenotype | Hit in Egfr/Ras microarray |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG13053 | 2.75 | Unknown | Yes | None | ||

| CG4382 | 2.47 | Carboxylesterase | Yes | Extra veins | Extra vein (RNAi) | |

| CG31075 | 2.11 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | ||||

| Fbp2 | 2.1 | Short-chain dehydrogenase | ||||

| CG4778 | 1.95 | Chitin binding | Yes | None | ||

| CG11899 | 1.89 | Aminotransferase | Yes | None | ||

| CG9027 | 1.86 | Superoxide dismutase | Yes | None | Jordan et al. (2005) | |

| BM-40-SPARC | 1.83 | Calcium binding | ||||

| CG6448 | 1.72 | Dehydrogenase | Yes | None | ||

| Ance | 1.68 | Angiotensin converting enzyme | ||||

| GstE1 | 1.66 | Glutathione S-transferase | ||||

| Mgstl | 1.66 | Glutathione S-transferase | ||||

| CG10359 | 1.62 | Unknown | Yes | None | Asha et al. (2003) | |

| CG10200 | 1.61 | Unknown | Yes | Lethal | ||

| AnnX | 1.56 | Phospholipid binding | ||||

| CG7860 | 1.54 | Peptidase T2 | Yes | Lethal | ||

| CG17746 | 1.52 | Phosphatase | Yes | Lethal | ||

| Idgf4 | 1.52 | Growth factor | Yes | None | ||

| SP1029 | 1.5 | Peptidase | Yes | Low viability | Firth and Baker (2007) | |

| Cyp4e2 | 1.49 | Cytochrome p450 | Yes | Lethal | Firth and Baker (2007) | |

| CG9914 | 1.48 | Enoyl-coa hydratase | Yes | None | ||

| CG4210 | 1.47 | Acetyltransferase | Yes | None | ||

| CG9691 | 1.45 | Unknown | Yes | None | ||

| CG12643 | 1.45 | Unknown | Yes | None | ||

| Regucalcin | 1.43 | Calcium-mediated signaling | Yes | Lethal |

Functional analysis of the most differentially expressed genes using reverse genetics identifies genes with roles in vein patterning

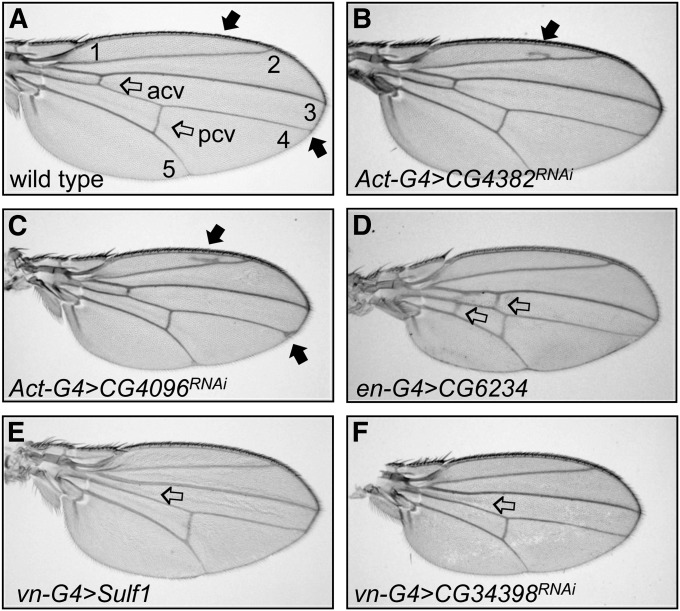

We used RNAi to test the function of 29 of the 50 most differentially expressed genes that were either poorly characterized or had unknown functions (Tables 1 and 2). When ubiquitously expressed using Act5C-GAL4 (Figure S1D), RNAi transgenes targeting 14/29 genes caused phenotypes—lethality (9), lower viability (2), and visible phenotypes (3) (Tables 1 and 2 and Table S2). Knockdown of CG4096 and CG4382 caused an extra-vein phenotype (Figure 2, B and C), which was of particular interest because abnormal vein phenotypes can indicate a function in the Egfr pathway.

Figure 2 .

Vein phenotypes displayed by Egfr-responsive genes. (A) Wild-type wing showing normal wing patterning with longitudinal veins (1–5) and crossveins (ACV and PCV, open arrows) and indicating other regions for comparison with experimental wings (solid arrows). (B) Act5C-GAL4; UAS-CG4382RNAi wing: a region of extra-vein material is present above L2 (solid arrow). (C) Act5C-GAL4; UAS-CG4096RNAi wing: a region of extra vein is present above L2 (solid arrow) and a delta of extra vein is present at the tip of L4 (solid arrow). (D) Act5C-GAL4; UAS-CG6234 wing: two additional crossveins are present (open arrows). (E) vn-GAL4; UAS-Sulf1 wing: the ACV is missing (open arrow). (F) vn-GAL4; UAS-CG34398RNAi wing: the ACV is missing (open arrow). All wings shown are female. In addition to vein defects, wings C–F are smaller than wild type.

To further test the 29 genes for vein phenotypes, including those for which ubiquitous RNAi was lethal, we used a number of tissue-specific GAL4 drivers to inhibit gene expression in a more restricted pattern (Table S2). Knockdown of CG4096 and CG4382 showed consistent extra-vein phenotypes and CG34398 showed a consistent loss of vein phenotype with a variety of GAL4 lines (Table 3 and Table S2). An additional 7 genes showed a loss of the anterior crossvein (ACV) when RNAi expression was driven with vn-GAL4 (Table S2). The ACV is very sensitive to Vn/Egfr signaling (Clifford and Schupbach 1989; Schnepp et al. 1996) and as vn-GAL4 is a loss-of-function allele in the vn ligand gene (C. L. Austin, unpublished observation), it may provide a sensitized genetic background for revealing genes functioning in the Egfr pathway. These 7 genes, therefore, warrant further analysis, but here we focused on the genes showing vein phenotypes that were apparent with drivers in addition to vn-GAL4.

Table 3. Genes showing vein phenotypes.

| Gene | RNAi-induced vein phenotype | OE-induced vein phenotype | Interaction with EgfrElp | Interaction with EGF ligand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG34398 | Loss | ND | None | ND |

| Sulf1 | None | Loss | Su (OE) | vn |

| CG4096 | Extra | ND | E (RNAi) | spi, krn, vn |

| CG6234 | None | Extra | None | ND |

| CG4382 | Extra | ND | None | ND |

OE, overexpression; ND, not determined; Su, Suppressor; E, Enhancer.

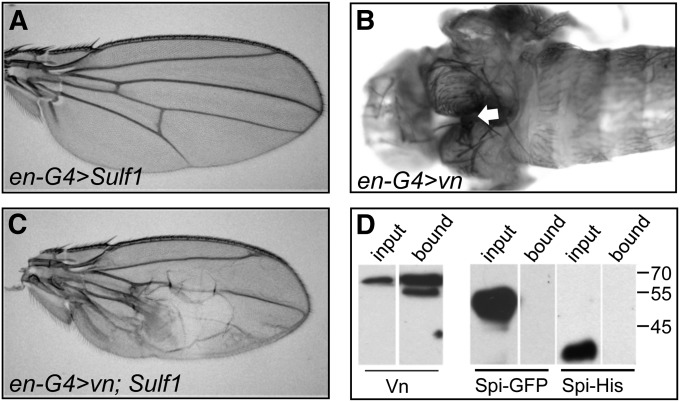

We also tested for phenotypic effects of overexpression of CG6234 and Sulf1, using cDNA transgenes. We analyzed these genes further because in situ analysis (see below) demonstrated that both genes were expressed in vein primordia, a major target tissue for Egfr signaling in the wing disc. Ectopic expression of CG6234 with multiple drivers resulted in an extra crossvein phenotype (Figure 2D, Table 3, and Table S2). Sulf1 causes a vein-loss phenotype when strongly overexpressed (Kleinschmit et al. 2010). Using en-GAL4 (Aza-Blanc et al. 1997) to misexpress the wild-type Sulf1 transgenes we generated (Figure 5A) or those of Kleinschmit et al. and growing the flies at 25° (or 29°) caused no vein-loss phenotype (Kleinschmit et al. 2010) (Figure S2A). However, an altered form of Sulf1 that is confined to the Golgi did cause a strong vein-loss phenotype consistent with a role for Sulf1 in vein patterning (Kleinschmit et al. 2010) (Figure S2C). The Golgi-tethered form also had a stronger effect on Wingless signaling (Kleinschmit et al. 2010), which suggests that retaining the enzyme in the Golgi may enhance its function. We also found loss of the ACV when Sulf1 was misexpressed with the vn-GAL4 driver, which likely provides a sensitized background because vn-GAL4 is a mutant allele (Table 3 and Figure 2E). Together these data are consistent with Sulf1 acting as a negative regulator of vein development.

Figure 5 .

Sulf1 interacts genetically with the Egfr ligand vn, which binds heparin. (A) en-GAL4; UAS-Sulf1 adult wing showing normal wing pattern. (B) en-GAL4; UAS-vn1.1 rare pharate adult with thoracic defect (arrow indicates cleft). (C) en-GAL4; UAS-vn1.1; UAS-Sulf1 adult wing with large posterior blister. (D) Western analysis of Vn, sSpi::GFP, or sSpi::HIS samples incubated with heparin-coated beads. “Input” lanes show starting material. “Bound” lanes show material eluted from beads in high salt. Only Vn bound to the beads (band in Vn-bound lane). Vn lanes were probed with α-Vn antibody and Spi::GFP and Spi::His lanes were probed with α-Spi antibody.

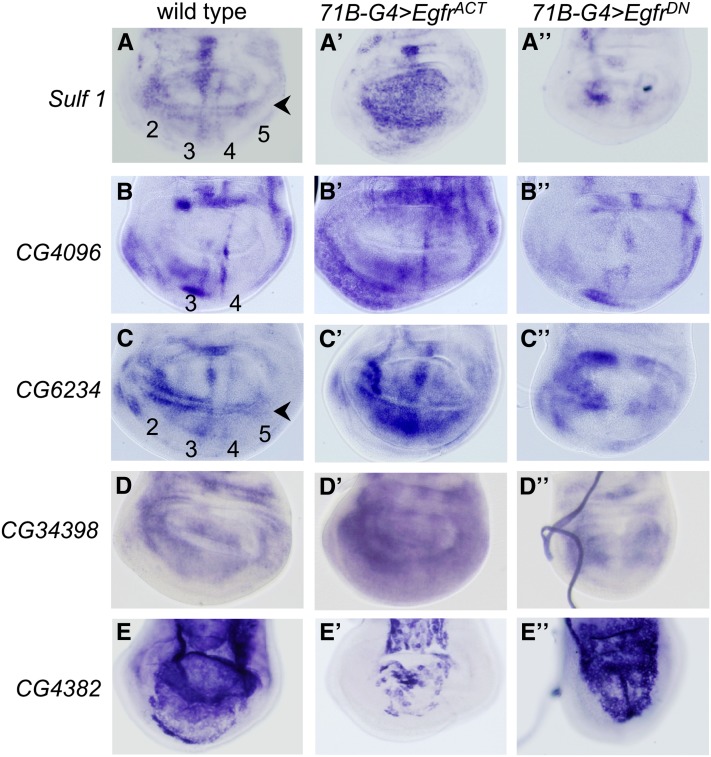

In situ hybridization confirms the response to Egfr signaling and identifies three genes expressed in vein primordia, an Egfr-signaling target tissue

The expression patterns of the three genes that showed venation defects with RNAi and two genes that showed venation defects following overexpression (Figure 2 and Table 3) were determined in wild-type wing discs and wing discs corresponding to the genotypes examined in the microarray analysis in which Egfr signaling was altered (Table 3 and Figure 3). The genes were expressed in a variety of patterns, and all showed changes in expression level or distribution, verifying the microarray data. The expression pattern and how it relates to the observed phenotypes for each of these five genes is discussed in the next sections.

Figure 3 .

Expression patterns displayed by Egfr-responsive genes. Shown is in situ hybridization to transcripts upregulated (A–D′′) or downregulated (E–E′′) by Egfr signaling. (A–A′′) Expression of Sulf1 in wild type (A) showing expression in longitudinal veins (2–5) and the wing margin (arrowhead), 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrACT (A′) showing expression throughout the wing pouch, and 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrDN (A′′) showing loss of expression in the wing pouch. (B–B′′) Expression of CG4096 in wild type (B) showing expression in longitudinal veins (3 and 4); 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrACT (B′) showing elevated expression in the pouch, pleura, and hinge; and 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrDN (B′′) showing some loss of expression in the pleura and hinge. (C–C′′) Expression of CG6234 in wild type (C) showing expression in longitudinal veins (2–5) and the wing margin (arrowhead), 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrACT (C′) showing expression throughout the wing pouch, and 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrDN (C′′) showing loss of expression in the wing pouch. (D–D′′) Expression of CG34398 in wild type (D) showing expression in broad domains in the disc, 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrACT (D′) showing elevated expression, and 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrDN (D′′) showing loss of expression in the central region of the disc. (E–E′′) Expression of CG4382 in wild type (E) showing expression in the peripodial membrane, 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrACT (E′) showing reduced expression in the peripodial membrane, and 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrDN (E′′) showing expression in the peripodial membrane.

Sulf1:

Sulf1 was expressed in all provein regions and was regulated by Egfr activity (Figure 3, A–A′′). Ectopic Egfr activity promoted expression throughout the wing pouch (Figure 3A′), whereas dominant negative Egfr greatly reduced expression in the central domain where 71B-GAL4 was expressed (Figure 3A′′). Sulf1 was also expressed robustly in S2 tissue-culture cells stably transfected with Egfr (S2-DER cells), which were induced to activate the Egfr pathway (Zak and Shilo 1990; Schweitzer et al. 1995) (Figure S3). Sequence analysis also shows the presence of ETS binding sites in the Sulf1 gene that could mediate signaling through Egfr signaling (Figure S4). ETS family transcription factors such as Pointed mediate Egfr/Ras/MAPK signaling (O’Neill et al. 1994). Induction by Egfr signaling has recently been shown to be important for the role of Sulf1 in the Hh signaling pathway (Wojcinski et al. 2011).

RNAi of Sulf1 had no effect and amorphic mutants also have only subtle phenotypes (Table 2) (Kleinschmit et al. 2010; You et al. 2011). Sulf1 overexpression, however, causes vein loss (Table 3 and Figure 2E) (Kleinschmit et al. 2010). In further genetic tests, we showed that Sulf1 behaves functionally as a negative regulator of Egfr signaling, most likely by modulating activity of the ligand Vn (see below).

CG4096:

CG4096 encodes an A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase with ThromboSpondin motifs (ADAMTS), a family of secreted enzymes with conserved domains conferring a variety of different functions (Porter et al. 2005). CG4096 is expressed in presumptive veins L3 and L4 (Figure 3B). Expression of CG4096 was more extensive in discs expressing EgfrACT (Figure 3B′); however, ectopic expression is not seen in the entire 71B-GAL4 expression domain. The specific expression of CG4096 in a subset of veins in wild type and its limited response to increased Egfr activity suggest that other factors may also be required for its expression. Also consistent with being a target of the pathway, CG4096 was expressed robustly in S2 tissue-culture cells stably transfected with Egfr (S2-DER cells), which were induced to activate the Egfr pathway (Zak and Shilo 1990; Schweitzer et al. 1995) (Figure S3). Sequence analysis also shows the presence of ETS binding sites in the CG4096 gene that could mediate signaling through Egfr signaling (Figure S4).

RNAi silencing of CG4096 gave a consistent extra-vein phenotype with an additional vein fragment above longitudinal vein 2 and some vein deltas (Figure 2C). These phenotypes are typical of elevated Egfr signaling and seen in flies with the hypermorphic EgfrElp allele (Figure 4B). The phenotype was not enhanced in flies coexpressing Dcr-2, which increases RNAi effects (CG4096dsRNA/UAS-Dcr-2; Act5C-GAL4, not shown) (Dietzl et al. 2007). Generating a null mutant, however, will be required to determine the full loss-of-function phenotype. In further genetic tests, we showed CG4096 behaves functionally as a negative regulator of Egfr signaling most likely by modulating ligand activity (see below).

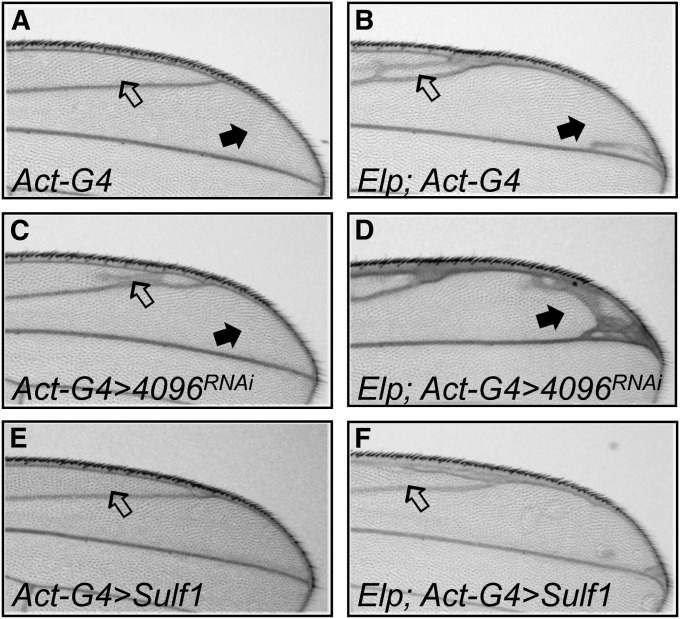

Figure 4 .

CG4096 and Sulf1 interact genetically with the hypermorphic EgfrElp allele. (A) Act5C-GAL4/+ showing the normal appearance of the distal-anterior portion of the wing blade (arrows indicate regions for comparison with other genotypes). (B) EgfrElp; Act5C-GAL4 wing with a region of extra-vein material above vein 2 (open arrow). (C) Act5C-GAL4; UAS-CG4096RNAi wing: a region of extra-vein material is present above vein 2 (open arrow). (D) EgfrElp; Act5C-GAL4; UAS-CG4096RNAi wing: there is an extensive region of extra-vein material not present in B or C) (solid arrow). (E) Act5C-GAL4; UAS-Sulf1 wing, exhibiting a normal pattern. (F) EgfrElp; Act5C-GAL4; UAS-Sulf1 wing showing suppression of the extra-vein material above vein 2. Compare with B (open arrow).

CG6234:

CG6234 is expressed in all provein regions (Figure 3C). Ectopic activity of Egfr elicits expression in the 71B-GAL4 pattern (Figure 3C′), and inhibition represses expression (Figure 3C′′). CG6234 is also known to be regulated by Wg signaling (Fang et al. 2006; Bhambhani et al. 2011). CG6234 encodes a protein with a predicted signal peptide, but the function of the CG6234 protein has not been elucidated (Table S3). Ubiquitous downregulation of CG6234 by RNAi caused lethality (Table 1), but no venation defects were seen using more specific drivers including vn-GAL4, which is likely to provide a sensitized background for observing vein defects (Table 3 and Table S2). Overexpression of CG6234, however, caused an ectopic crossvein phenotype inducing additional ACVs and/or posterior crossveins (PCVs) (Figure 2D, Table 3, and Table S2). This is distinct from that seen following widespread activation of the Egfr pathway, in which there is a more global extra-vein phenotype (Figure 1D). The crossveins form during pupal development and, while multiple pathways are involved, there is a major role for signaling by the bone morphogenetic pathway (BMP) (O’Connor et al. 2006). The ectopic crossvein phenotype seen after overexpression of CG6234 suggests that although the gene is strongly induced by Egfr signaling, it may function in the BMP pathway. Further molecular analysis is required to test this hypothesis.

CG34398:

CG34398 is an uncharacterized gene containing no known domains apart from predicted coiled-coil regions. There is an Anopheles gambiae ortholog for CG34398, but no clear vertebrate ortholog (Table S3). The gene is expressed broadly and exhibits increased expression in 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrACT discs and reduced expression in 71B-GAL4; UAS EgfrDN discs (Figure 3, D–D′′). Downregulation of CG34398 via RNAi resulted in the loss of the ACV and/or the PCV with a number of drivers including vn-GAL4 (Table 3, Table S2, and Figure 2F). Together these data suggest that CG34398 is a transcriptional target of the Egfr pathway and plays a positive role in vein patterning.

CG4382:

CG4382 encodes a glutathione S-transferase (Alias and Clark 2007). CG4382 showed robust expression in the peripodial membrane, which was strongly repressed by Egfr signaling in 71B-GAL4; UAS-EgfrACT individuals (Figure 3, E–E′′). The peripodial membrane is a second cell layer that overlays the disc proper (columnar epithelium). 71B-GAL is expressed in the peripodial membrane (Figure S1C) and, therefore, there may be direct inhibition of CG4382 expression in these cells. On the other hand, activation may occur via signaling from the columnar epithelium. RNAi against CG4382 using expression with multiple different GAL4 drivers resulted in an extra-vein phenotype (Figure 2B, Table 2, and Table S2). Together the data support the idea that CG4382 functions as a negative regulator of vein development, which is repressed by a high level of Egfr signaling. The expression of CG4382 in the peripodial membrane overlying the disc proper suggests that its function in venation appears to involve communication between two cell layers, as has been noted for patterning of the major regions of the wing disc (Baena-Lopez et al. 2003; Pallavi and Shashidhara 2003). Our results suggest the peripodial membrane may also have a more specific role in vein patterning.

Genetic interactions with EgfrElp link CG4096 and Sulf1 to the Egfr pathway

To test for a functional link between the candidate genes and the Egfr pathway, we looked for modification of the phenotype caused by a hypermorphic Egfr allele, EgfrElp. Candidate genes (CGX) were either silenced by RNAi (EgfrElp; Act5C-GAL4; UAS-CGXRNAi) or overexpressed (EgfrElp; Act5C-GAL4; UAS-CGX) in EgfrElp heterozygotes. EgfrElp flies have small eyes and an extra-vein phenotype due to constitutive signaling (Figure 4B). All 29 genes were tested although not all crosses yielded viable adults. Of the nine RNAi lines that were lethal with Act5C-GAL4 (Tables 1 and 2), we were able to examine all but two as pharate adults for gross defects and eye phenotypes (CG5800 and CG10200 died prior to this stage). From the 27 genes examined, 2 showed changes in the EgfrElp phenotype: downregulation of CG4096 by RNAi enhanced the extra-vein phenotype (Figure 4, A–D) and overexpression of Sulf1 caused suppression of the extra-vein phenotype (Figure 4, E and F). We did not detect any changes in eye phenotype. On the basis of the genetic interaction with Egfr we decided to examine Sulf1 and CG4096 in more detail.

Genetic interaction suggests Sulf1 modulates Vn activity

vn encodes a neuregulin-like ligand that activates Egfr in the wing (Schnepp et al. 1996). Phenotypes caused by misexpression of vn can be suppressed by coexpression of the inhibitor aos (Wessells et al. 1999). Misexpression of a vn transgene with en-GAL4 (en-GAL4; UAS-vn1.1) caused lethality mainly at the pupal stage with only 6% of animals surviving long enough to die as pharate adults with severe thoracic defects (Figure 5B). Remarkably, coexpression of Sulf1 rescued these individuals such that some survived to adulthood. We tested three independent lines of UAS-Sulf1 and found 14%, 20%, and 23% of the expected number of en-GAL4; UAS-vn1.1; UAS-Sulf1 individuals survived to become adults. (The expected number was based on the survival of sibs without the UAS-vn1.1 gene.) Survivors had extra wing veins and blisters in the posterior region, indicative of vn overactivity (Figure 5C). The rescue suggests that overexpression of Sulf1, which likely encodes a pathway inhibitor, compensated for overproduction of the ligand Vn. To eliminate the possibility that the rescue was nonspecific and due to a dilution of GAL4 levels caused by competition for binding when an additional UAS transgene was present, we also examined a control genotype (en-GAL4; UAS-vn1.1; UAS-GFP); these animals did not survive. Sulf1 overexpression was unable to rescue the lethality resulting from similar overexpression of the TGF-α ligand sspi (secreted spi). sSpi is a more potent ligand than Vn (Schnepp et al. 1998) and en-GAL4; UAS-sspi animals died as embryos. Due to the early lethality, this test may be too stringent to rule out an effect of Sulf1 on sSpi function.

At the biochemical level, the effects of Sulf1 on Vn may be an indirect consequence of the endosulfatase activity of Sulf1 (Dhoot et al. 2001), which modifies heparan sulfate (HS) chains by removing 6-O-sulfate groups. If the function of Vn is enhanced by binding to HS chains, specifically at 6-O-sulfate moieties, then the level of Sulf1 could modulate Vn activity by removing these binding sites. In keeping with this idea we found that Vn bound heparin (a highly sulfated glycosaminoglycan) in an in vitro assay (Figure 5D). The interaction may be limited to the ligand Vn, as we did not observe binding of sSpi to heparin (Figure 5D) (Klein et al. 2004).

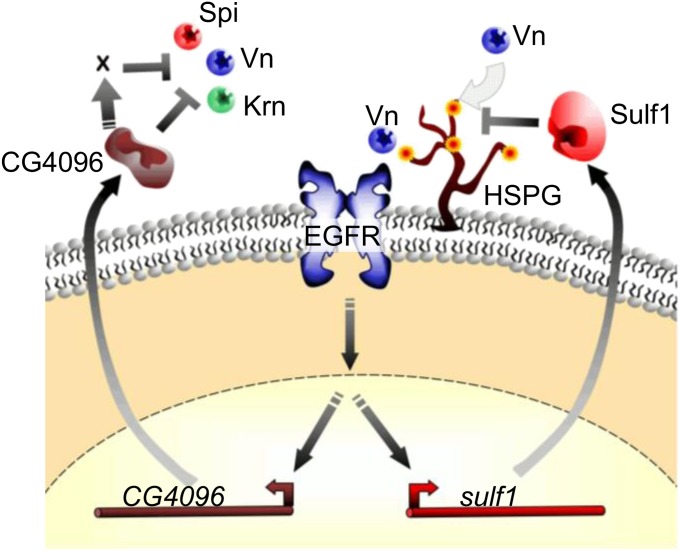

Genetic analysis suggests CG4096 modulates Egfr signaling at the level of ligand action

The extra-vein phenotype resulting from RNAi of CG4096 is consistent with the idea that it functions as a negative regulator of Egfr signaling. To test for genetic interactions between CG4096 and genes in the pathway, we determined whether reducing the dose of these genes suppressed the extra-vein phenotype (Act5C-GAL4; UAS-4096RNAi; geneX−/+). Reducing the dose of Egfr, pnt (a transcription factor that mediates Egfr signaling), or any single zygotically active ligand (spi, vn, or krn) had no significant effect on the extra-vein phenotype (Table 4). Reducing the dose of Ras85D suppressed the phenotype (Table 4). Ras85D is a dose-sensitive component in the Egfr pathway (Simon et al. 1991). We also tested all possible double combinations of the ligands. Two, spi; krn and krn, vn, showed a significant suppression of the extra-vein phenotype (Table 4). The suppression, however, was pronounced when the dose of three ligand genes was reduced simultaneously (Table 4). Both the predicted secreted nature of CG4096 and genetic evidence showing suppression at the level of the ligands support the hypothesis that CG4096 negatively regulates Egfr signaling by masking ligand activity either directly or indirectly (Figure 7).

Table 4. Suppression of Act5C-GAL4; UAS-CG4096RNAi extra-vein phenotype with lowered dose of EGF ligands.

| Heterozygous mutant allele(s) | Fraction of wings with extra vein (n) |

|---|---|

| None (control) | 0.91 (32) |

| Egfr3F18 | 0.98 (50) |

| Ras85De1B | 0.17 (66)** |

| pntΔ88 | 0.95 (42) |

| spi1 | 1.00 (26) |

| vn3 | 0.96 (28) |

| krn27 | 0.97 (62) |

| spi1; vnL6 | 0.91 (44) |

| spi1; krn27 | 0.59 (32)** |

| vnL6, krn27 | 0.82 (38)* |

| spi1; vnL6, krn27 | 0.17 (52)** |

P = 0.005, significantly different from control; **P < 0.0001, significantly different from control.

Figure 7 .

Working model for the function of Sulf1 and CG4096 in the Egfr pathway. A schematic of the Egfr pathway is shown with Vn binding to the receptor (the other ligands are also likely to be involved), which leads to activation of the pathway and expression of the Sulf1 and CG4096 genes. Sulf1 blocks binding of Vn to HSPG by removing 6-O sulfates. We hypothesize this is inhibitory because binding of Vn to HSPG facilitates interaction with the receptor. CG4096 negatively regulates the pathway by masking the EGF ligands by an unknown mechanism that may be direct or involve an additional factor (X). X could also be a ligand activator that CG4096 inhibits.

Discussion

Transcriptional profiling of Egfr signaling identified 162 genes that represent a typical genomic cross-section of molecular functions

We used a whole-genome microarray assay to detect transcripts that responded to changed activity of the Egfr pathway in the Drosophila wing disc. The Gene Ontology (GO) classifications of the 130 genes for which there was information in the GO database showed a distribution of molecular functions that closely mirrors the frequencies of each category in the whole genome (Table S1 and Figure S5). This is in contrast to a large-scale gain-of-function genetic screen for genes involved in vein patterning (Molnar et al. 2006), where the distribution of gene functions was biased toward recovering those encoding transcription factors and cell-signaling molecules (Molnar et al. 2006). The genes Molnar et al. recovered, which included 60% of known genes in the Egfr and other major signaling, were identified on the basis of their ability to cause a vein phenotype and this increased the recovery of control genes. Using reverse genetic analysis only 17% (5/29) of the genes we characterized as having robust transcriptional changes caused vein patterning defects (Tables 1–3). We did, however, discover two new feedback regulators as described in a following section.

Among the remaining 32 genes with nonannotated molecular functions, 21 (65%) are predicted to encode either secreted or transmembrane proteins (Table S3). This exceeds the frequency of such proteins in the whole genome where genes encoding secreted proteins compose 19% and genes encoding transmembrane proteins compose 3.4% of the genome (http://www.pantherdb.org). BLASTP analysis indicates that 26 of the 32 genes are conserved only in insects (17) or unique to Drosophilidae (9) (Table S3). We tested the function of 8 of these genes using RNAi and 5 showed wing defects (Table S1 and Table S3). As a group these 24 genes should be interesting to analyze because over half of those tested showed wing phenotypes, a large proportion are secreted, and they are unique to insects.

Genetic analysis of top candidates led to the discovery of two new negative feedback regulators of Egfr signaling

We analyzed 29 Egfr-responsive genes using RNAi. This allowed us to screen rapidly through the candidates. Additional characterization identified two genes, Sulf1 and CG4096, which behave genetically as negative regulators of Egfr signaling. The potential role of these genes in the Egfr pathway is discussed next.

Sulf1 is an enzyme that modifies HS. The binding of growth factors to HS chains attached to a protein backbone [heparin-sulfated proteoglycan (HSPG)] is important for regulating growth factor distribution, activity, and interaction with other molecules, including receptors (Sarrazin et al. 2011). HS chains are synthesized in the Golgi and then remodeled by enzymes including sulfatases that remove specific sulfate groups. These enzymes play important roles because the final sulfation pattern is a determinant of ligand binding. Products of the Sulfated genes (Sulfs) are endosulfatases that remove 6-O-sulfate groups from trisulfated glucosamine units (Shilatifard and Cummings 1994; Dhoot et al. 2001; Morimoto-Tomita et al. 2002; Ai et al. 2003, 2006). There are two vertebrate genes, Sulf1 and Sulf2, and a single Drosophila gene, Sulf1. The genetic characterization of the mouse and Drosophila genes has confirmed the ability of the Sulf genes to act as endosulfatases by showing that Sulf loss-of-function mutants accumulate trisulfated disaccharides (Lamanna et al. 2006; Kleinschmit et al. 2010).

Genetic analysis of Sulfs in vertebrates revealed that the genes have redundant biochemical functions and are not required for development, although double-mutant (Sulf1−/−; Sulf2−/−) mice died soon after birth with low body weight caused by a defect in innervation of the esophagus (Lamanna et al. 2006; Ai et al. 2007; Holst et al. 2007; Lum et al. 2007). In vertebrates, the Sulfs have been linked to multiple signaling pathways, including FGF, VEGF, WNT, BMP, HH, and EGF, and have also been found to be important in cancer (Lai et al. 2008; Rosen and Lemjabbar-Alaoui 2010). In Drosophila, Sulf1 mutants are adult viable and fertile, but have subtle phenotypes that demonstrate a role for the genes in Wg and Hh signaling (Kleinschmit et al. 2010; Wojcinski et al. 2011; You et al. 2011). Overexpression of Drosophila Sulf1 also suggests it has a role in FGF signaling (Kamimura et al. 2006). Here we provided the first evidence of a role for Sulf1 and HSPGs in EGF signaling in Drosophila.

We found Sulf1 is a target of Egfr signaling in the Drosophila wing, an observation also reported by Wojcinski et al. in their analysis of Sulf1 in Hh signaling (Wojcinski et al. 2011). We discovered that Sulf1 not only is induced by Egfr but also functions directly in the pathway as a negative feedback regulator to repress signaling. Overexpression of Sulf1 suppressed the EgfrElp phenotype (Figure 4, E and F) and rescued lethality caused by overexpression of vn (Figure 5, A–C). Ectopic expression of Sulf1 caused vein loss, which is characteristic of reduced Egfr activity, and coexpression of vn restored veins (Figure 2E and Figure S2, C and D) (Kleinschmit et al. 2010). This genetic evidence is consistent with Sulf1 modulating Vn activity and is supported by the observation that Vn binds heparin (Figure 5D).

On the basis of these results, we hypothesize that Sulf1 reduces Vn binding to HSPGs by removal of 6-O-sulfate moieties and hence affects it localization in the extracellular matrix (ECM) (Figure 7). Some vertebrate EGF ligands are known to bind HSPGs, including some neuregulins (NRGs) and heparin-binding EGF (Pankonin et al. 2005; Mahtouk et al. 2006; Iwamoto et al. 2010). The NRGs share structural similarity with Vn because both types of growth factors have an Ig domain in addition to the EGF domain (Schnepp et al. 1996). The Ig domain in NRG is required for binding to heparin, and sulfate groups including 6-O-sulfate groups play a role in the interaction (Li and Loeb 2001; Pankonin et al. 2005). The addition of a Drosophila EGF ligand to the collection of known ligands regulated by Sulf1 highlights the broad role HSPGs play in signaling pathways. It will be important to determine more about the Vn-HSPG interaction, including discovering which proteoglycan is involved.

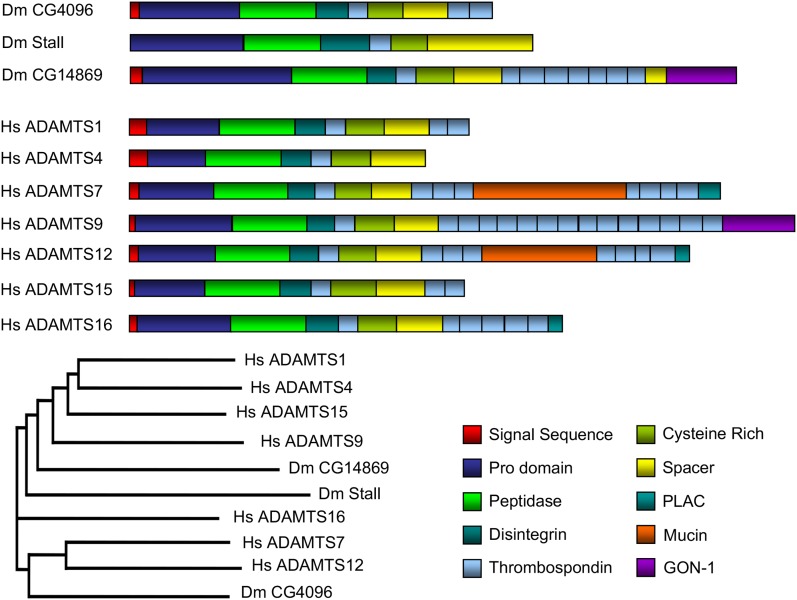

CG4096 contains predicted protein domains characteristic of an ADAMTS family member, including a zinc-dependent protease and three thrombospondin-like repeats (Figure 6). It is one of 3 genes in Drosophila belonging to the ADAMTS family (Figure 6) (Nicholson et al. 2005). Only one of these, stall, has been analyzed genetically and found to be involved in ovary development (Ozdowski et al. 2009). In mammals there are 19 ADAMTS genes with diverse biological roles in the ECM (reviewed in Porter et al. 2005; Apte 2009; Stanton et al. 2011). The genes have also been implicated in diseases including atherosclerosis, arthritis, and cancer (reviewed in Lin and Liu 2010; Salter et al. 2010; Le Goff and Cormier-Daire 2011; Wagstaff et al. 2011).

Figure 6 .

Domain architecture of CG4096 and other ADAMTS proteins. The three Drosophila (Dm) ADAMTS proteins are shown at the top. Seven of the 19 human (Hs) ADAMTS proteins that are most related by sequence or domain structure to the Drosophila proteins are shown below. CG4096 is phylogenetically closest to ADAMTS7/12, but lacks the mucin and PLAC domains. CG4096 has a domain structure most similar to ADAMTS1 and its subfamily of related proteins ADAMTS4/5/8/15. ADAMTS1, ADAMTS4, and ADAMTS15 are shown. CG14869 is similar to ADAMTS9 because both have a GON-1 domain. Stall is closest to ADAMTS16. Conserved functional domains are color coded. The longest isoform of each protein is shown. Domain analysis was performed using Pfam and the proteins are drawn to scale.

Sequence analysis places CG4096 closest to human ADAMTS7 and ADAMTS12 (Nicholson et al. 2005). But CG4096 does not possess a protease and a lacunin (PLAC) domain or a mucin domain, which are seen in mammalian genes (Figure 6) (Porter et al. 2005; Apte 2009). On the basis of domain architecture (predicted using Prodom), CG4096 most closely resembles ADAMTS1 and its subfamily of proteins, ADAMTS4/5/8/15. Of these, ADAMTS15 is most closely related to CG4096 by sequence (Figure 6) (Nicholson et al. 2005).

Metalloproteases in general are well characterized for their positive roles in cancer progression through the ability to degrade the ECM and facilitate metastasis. Evidence, however, is emerging that ADAMTS proteins can also function as tumor suppressors. ADAMTS1, ADAMTS12, and ADAMTS15 act as tumor suppressors in prostate, colon, and breast cancer (Porter et al. 2006; Moncada-Pazos et al. 2009; Viloria et al. 2009; El Hour et al. 2010; Molokwu et al. 2010). Our genetic evidence shows CG4096 has an inhibitory effect on Egfr activity. By extension to the role of Egfr/Ras in tumors this would be considered a tumor suppressor function. Interestingly, there is also a connection to the Egfr pathway in mammals where ADAMTS1 acts as an activator by promoting the shedding of heparin-binding EGF ligands (Liu et al. 2006, 2009; Ricciardelli et al. 2011). In contrast, and in keeping with the inhibitory function of CG4096, it has also been suggested that a self-cleaved product of ADAMTS1 could act as a repressor by sequestering ligands (Liu et al. 2006).

It is intriguing to note both the tumor suppressor function and the connection to Egfr signaling of some mammalian ADAMTS genes. With this in mind, CG4096 could function like the cleaved form of ADAMTS-1 to sequester the ligands and prevent them from binding the receptor (Figure 7). It is also possible the effect on ligands is indirect as ADAMTS proteins have many different ECM substrates (Figure 7). Further molecular and genetic analysis of CG4096 will be important to decipher its role in Drosophila. Any discoveries made in Drosophila are also likely to further the understanding of the ADAMTS family in other animals, including humans.

New feedback controls by genes that play small roles in the Egfr signaling pathway

The microarray screen described here allowed us to identify two secreted factors that are negative feedback regulators of the Egfr pathway. We propose that both Sulf1 and CG4096 fine-tune Egfr signaling in the extracellular phase of the signaling pathway by negatively regulating the interaction between ligands and the receptor (Figure 7). The identification of two new negative regulators of Egfr signaling highlights the importance of mechanisms that dampen signaling. Sulf1 mutants are viable with mild morphological changes (Kleinschmit et al. 2010; You et al. 2011), and reducing CG4096 function with RNAi has only subtle effects. Yet these small effects on a vital appendage like a wing could have profound consequences for flies in the wild. The ability to turn off a pathway is clearly critical for development and homeostasis and as a result multiple negative regulators exist. This raises the question of how many such controls are in place and what approaches can be used to find them. Given the genome-wide resources available for Drosophila, combining transcriptional profiling with reverse genetics is a highly tractable option that in our experience appears well suited to the discovery of genes with small effects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hiroshi Nakato for Sulf1 transgenic flies, the Bloomington Stock Center for multiple fly strains, Chiu-Wen Lin for the heparin binding assays, and Nicole Werner for conducting some fly crosses. The anti-sSpi antibody developed by B.-Z. Shilo was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by the Department of Biology, University of Iowa (Iowa City, IA). Our work was supported by an award from the National Science Foundation (IBN0920231 to A.S.) and a Pelotonia fellowship (to C.L.A.).

Footnotes

Communicating editor: I. K. Hariharan

Literature Cited

- Ai X., Do A. T., Lozynska O., Kusche-Gullberg M., Lindahl U., et al. , 2003. QSulf1 remodels the 6-O sulfation states of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans to promote Wnt signaling. J. Cell Biol. 162: 341–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai X., Do A. T., Kusche-Gullberg M., Lindahl U., Lu K., et al. , 2006. Substrate specificity and domain functions of extracellular heparan sulfate 6-O-endosulfatases, QSulf1 and QSulf2. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 4969–4976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai X., Kitazawa T., Do A. T., Kusche-Gullberg M., Labosky P. A., et al. , 2007. SULF1 and SULF2 regulate heparan sulfate-mediated GDNF signaling for esophageal innervation. Development 134: 3327–3338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alias Z., Clark A. G., 2007. Studies on the glutathione S-transferase proteome of adult Drosophila melanogaster: responsiveness to chemical challenge. Proteomics 7: 3618–3628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apte S. S., 2009. A disintegrin-like and metalloprotease (reprolysin-type) with thrombospondin type 1 motif (ADAMTS) superfamily: functions and mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 284: 31493–31497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asha H., Nagy I., Kovacs G., Stetson D., Ando I., et al. , 2003. Analysis of Ras-induced overproliferation in Drosophila hemocytes. Genetics 163: 203–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avraham R., Yarden Y., 2011. Feedback regulation of EGFR signalling: decision making by early and delayed loops. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12: 104–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aza-Blanc P., Ramirez-Weber F. A., Laget M. P., Schwartz C., Kornberg T. B., 1997. Proteolysis that is inhibited by hedgehog targets Cubitus interruptus protein to the nucleus and converts it to a repressor. Cell 89: 1043–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena-Lopez L. A., Pastor-Pareja J. C., Resino J., 2003. Wg and Egfr signalling antagonise the development of the peripodial epithelium in Drosophila wing discs. Development 130: 6497–6506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhambhani C., Chang J. L., Akey D. L., Cadigan K. M., 2011. The oligomeric state of CtBP determines its role as a transcriptional co-activator and co-repressor of Wingless targets. EMBO J. 30: 2031–2043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair S. S., 2007. Wing vein patterning in Drosophila and the analysis of intercellular signaling. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23: 293–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad B. M., Irizarry R. A., Astrand M., Speed T. P., 2003. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19: 185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A., Perrimon N., 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118: 401–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buff E., Carmena A., Gisselbrecht S., Jimenez F., Michelson A. M., 1998. Signalling by the Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor is required for the specification and diversification of embryonic muscle progenitors. Development 125: 2075–2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M. J., Jacobsen T. L., Cain D. M., Jarman M. G., Hubank M., et al. , 2003. Discovery of genes with highly restricted expression patterns in the Drosophila wing disc using DNA oligonucleotide microarrays. Development 130: 659–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casci T., Vinos J., Freeman M., 1999. Sprouty, an intracellular inhibitor of Ras signaling. Cell 96: 655–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford R. J., Schupbach T., 1989. Coordinately and differentially mutable activities of torpedo, the Drosophila melanogaster homolog of the vertebrate EGF receptor gene. Genetics 123: 771–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppey M., Boettiger A. N., Berezhkovskii A. M., Shvartsman S. Y., 2008. Nuclear trapping shapes the terminal gradient in the Drosophila embryo. Curr. Biol. 18: 915–919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Celis J. F., Llimargas M., Casanova J., 1995. Ventral veinless, the gene encoding the Cf1a transcription factor, links positional information and cell differentiation during embryonic and imaginal development in Drosophila melanogaster. Development 121: 3405–3416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhoot G. K., Gustafsson M. K., Ai X., Sun W., Standiford D. M., et al. , 2001. Regulation of Wnt signaling and embryo patterning by an extracellular sulfatase. Science 293: 1663–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzl G., Chen D., Schnorrer F., Su K. C., Barinova Y., et al. , 2007. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature 448: 151–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hour M., Moncada-Pazos A., Blacher S., Masset A., Cal S., et al. , 2010. Higher sensitivity of Adamts12-deficient mice to tumor growth and angiogenesis. Oncogene 29: 3025–3032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang M., Li J., Blauwkamp T., Bhambhani C., Campbell N., et al. , 2006. C-terminal-binding protein directly activates and represses Wnt transcriptional targets in Drosophila. EMBO J. 25: 2735–2745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth L. C., Baker N. E., 2007. Spitz from the retina regulates genes transcribed in the second mitotic wave, peripodial epithelium, glia and plasmatocytes of the Drosophila eye imaginal disc. Dev. Biol. 307: 521–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay L., Scholz H., Golembo M., Klaes A., Shilo B.-Z., et al. , 1996. EGF receptor signaling induces pointed P1 transcription and inactivates Yan protein in the Drosophila embryonic ventral ectoderm. Development 122: 3355–3362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay L., Seger R., Shilo B.-Z., 1997. In situ activation pattern of Drosophila EGF receptor pathway during development. Science 277: 1103–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman R. C., Carey V. J., Bates D. M., Bolstad B., Dettling M., et al. , 2004. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5: R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiglione C., Carraway K. L. r., Amundadottir L. T., Boswell R. E., Perrimon N., et al. , 1999. The transmembrane molecule kekkon 1 acts in a feedback loop to negatively regulate the activity of the Drosophila EGF receptor during oogenesis. Cell 96: 847–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golembo M., Schweitzer R., Freeman M., Shilo B.-Z., 1996. argos transcription is induced by the Drosophila EGF receptor pathway to form an inhibitory feedback loop. Development 122: 223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golembo M., Yarnitzky T., Volk T., Shilo B. Z., 1999. Vein expression is induced by the EGF receptor pathway to provide a positive feedback loop in patterning the Drosophila embryonic ventral ectoderm. Genes Dev. 13: 158–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez A. R., Lopez-Varea A., Molnar C., de la Calle-Mustienes E., Ruiz-Gomez M., et al. , 2005. Conserved cross-interactions in Drosophila and Xenopus between Ras/MAPK signaling and the dual-specificity phosphatase MKP3. Dev. Dyn. 232: 695–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacohen N., Kramer S., Sutherland D., Hiromi Y., Krasnow M. A., 1998. sprouty encodes a novel antagonist of FGF signaling that patterns apical branching of the Drosophila airways. Cell 92: 253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst C. R., Bou-Reslan H., Gore B. B., Wong K., Grant D., et al. , 2007. Secreted sulfatases Sulf1 and Sulf2 have overlapping yet essential roles in mouse neonatal survival. PLoS ONE 2: e575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto R., Mine N., Kawaguchi T., Minami S., Saeki K., et al. , 2010. HB-EGF function in cardiac valve development requires interaction with heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Development 137: 2205–2214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K. C., Hatfield S. D., Tworoger M., Ward E. J., Fischer K. A., et al. , 2005. Genome wide analysis of transcript levels after perturbation of the EGFR pathway in the Drosophila ovary. Dev. Dyn. 232: 709–724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura K., Koyama T., Habuchi H., Ueda R., Masu M., et al. , 2006. Specific and flexible roles of heparan sulfate modifications in Drosophila FGF signaling. J. Cell Biol. 174: 773–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. E., Kim S. H., Choi K. Y., 2003. Regulation of Drosophila MKP-3 by Drosophila ERK. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1010: 51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D. E., Nappi V. M., Reeves G. T., Shvartsman S. Y., Lemmon M. A., 2004. Argos inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor signalling by ligand sequestration. Nature 430: 1040–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinschmit A., Koyama T., Dejima K., Hayashi Y., Kamimura K., et al. , 2010. Drosophila heparan sulfate 6-O endosulfatase regulates Wingless morphogen gradient formation. Dev. Biol. 345: 204–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J. P., Sandhu D. S., Shire A. M., Roberts L. R., 2008. The tumor suppressor function of human sulfatase 1 (SULF1) in carcinogenesis. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 39: 149–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamanna W. C., Baldwin R. J., Padva M., Kalus I., Ten Dam G., et al. , 2006. Heparan sulfate 6-O-endosulfatases: discrete in vivo activities and functional co-operativity. Biochem. J. 400: 63–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Goff C., Cormier-Daire V., 2011. The ADAMTS(L) family and human genetic disorders. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20: R163–R167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Loeb J. A., 2001. Neuregulin-heparan-sulfate proteoglycan interactions produce sustained erbB receptor activation required for the induction of acetylcholine receptors in muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 38068–38075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Carthew R. W., 2005. A microRNA mediates EGF receptor signaling and promotes photoreceptor differentiation in the Drosophila eye. Cell 123: 1267–1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin E. A., Liu C. J., 2010. The role of ADAMTSs in arthritis. Protein Cell 1: 33–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. J., Xu Y., Yu Q., 2006. Full-length ADAMTS-1 and the ADAMTS-1 fragments display pro- and antimetastatic activity, respectively. Oncogene 25: 2452–2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llimargas M., Casanova J., 1997. Ventral veinless, a POU domain transcription factor, regulates different transduction pathways required for tracheal branching in Drosophila. Development 124: 3273–3281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Wang Q., Hu G., Van Poznak C., Fleisher M., et al. , 2009. ADAMTS1 and MMP1 proteolytically engage EGF-like ligands in an osteolytic signaling cascade for bone metastasis. Genes Dev. 23: 1882–1894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum D. H., Tan J., Rosen S. D., Werb Z., 2007. Gene trap disruption of the mouse heparan sulfate 6-O-endosulfatase gene, Sulf2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27: 678–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahtouk K., Cremer F. W., Reme T., Jourdan M., Baudard M., et al. , 2006. Heparan sulphate proteoglycans are essential for the myeloma cell growth activity of EGF-family ligands in multiple myeloma. Oncogene 25: 7180–7191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar C., Lopez-Varea A., Hernandez R., de Celis J. F., 2006. A gain-of-function screen identifying genes required for vein formation in the Drosophila melanogaster wing. Genetics 174: 1635–1659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molokwu C. N., Adeniji O. O., Chandrasekharan S., Hamdy F. C., Buttle D. J., 2010. Androgen regulates ADAMTS15 gene expression in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Invest. 28: 698–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncada-Pazos A., Obaya A. J., Fraga M. F., Viloria C. G., Capella G., et al. , 2009. The ADAMTS12 metalloprotease gene is epigenetically silenced in tumor cells and transcriptionally activated in the stroma during progression of colon cancer. J. Cell Sci. 122: 2906–2913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto-Tomita M., Uchimura K., Werb Z., Hemmerich S., Rosen S. D., 2002. Cloning and characterization of two extracellular heparin-degrading endosulfatases in mice and humans. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 49175–49185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson A. C., Malik S. B., Logsdon J. M., Jr, Van Meir E. G., 2005. Functional evolution of ADAMTS genes: evidence from analyses of phylogeny and gene organization. BMC Evol. Biol. 5: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor M. B., Umulis D., Othmer H. G., Blair S. S., 2006. Shaping BMP morphogen gradients in the Drosophila embryo and pupal wing. Development 133: 183–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill E. M., Rebay I., Tijan R., Rubin G. M., 1994. The activities of two Ets-related transcription factors required for Drosophila eye development are modulated by the Ras/MAPK pathway. Cell 78: 137–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozdowski E. F., Mowery Y. M., Cronmiller C., 2009. Stall encodes an ADAMTS metalloprotease and interacts genetically with Delta in Drosophila ovarian follicle formation. Genetics 183: 1027–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai L. M., Barcelo G., Schupbach T., 2000. D-cbl, a negative regulator of the Egfr pathway, is required for dorsoventral patterning in Drosophila oogenesis. Cell 103: 51–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallavi S. K., Shashidhara L. S., 2003. Egfr/Ras pathway mediates interactions between peripodial and disc proper cells in Drosophila wing discs. Development 130: 4931–4941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankonin M. S., Gallagher J. T., Loeb J. A., 2005. Specific structural features of heparan sulfate proteoglycans potentiate neuregulin-1 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 383–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter S., Clark I. M., Kevorkian L., Edwards D. R., 2005. The ADAMTS metalloproteinases. Biochem. J. 386: 15–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter S., Span P. N., Sweep F. C., Tjan-Heijnen V. C., Pennington C. J., et al. , 2006. ADAMTS8 and ADAMTS15 expression predicts survival in human breast carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 118: 1241–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queenan A. M., Ghabrial A., Schupbach T., 1997. Ectopic activation of torpedo/Egfr, a Drosophila receptor tyrosine kinase, dorsalizes both the eggshell and the embryo. Development 124: 3871–3880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardelli C., Frewin K. M., Tan Ide A., Williams E. D., Opeskin K., et al. , 2011. The ADAMTS1 protease gene is required for mammary tumor growth and metastasis. Am. J. Pathol. 179: 3075–3085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rintelen F., Hafen E., Nairz K., 2003. The Drosophila dual-specificity ERK phosphatase DMKP3 cooperates with the ERK tyrosine phosphatase PTP-ER. Development 130: 3479–3490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen S. D., Lemjabbar-Alaoui H., 2010. Sulf-2: an extracellular modulator of cell signaling and a cancer target candidate. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 14: 935–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter R. C., Ashlin T. G., Kwan A. P., Ramji D. P., 2010. ADAMTS proteases: Key roles in atherosclerosis? J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 88: 1203–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin S., Lamanna W. C., Esko J. D., 2011. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3: 1–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnepp B., Grumbling G., Donaldson T., Simcox A., 1996. Vein is a novel component in the Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor pathway with similarity to the neuregulins. Genes Dev. 10: 2302–2313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnepp B., Donaldson T., Grumbling G., Ostrowski S., Schweitzer R., et al. , 1998. EGF domain swap converts a Drosophila EGF-receptor activator into an inhibitor. Genes Dev. 12: 908–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R., Howes R., Smith R., Shilo B.-Z., Freeman M., 1995. Inhibition of Drosophila EGF receptor activation by the secreted protein Argos. Nature 376: 699–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilatifard A., Cummings R. D., 1994. Purification and characterization of N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfate sulfatase from bovine kidney: evidence for the presence of a novel endosulfatase activity. Biochemistry 33: 4273–4282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilo B. Z., 2005. Regulating the dynamics of EGF receptor signaling in space and time. Development 132: 4017–4027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simcox A. A., Grumbling G., Schnepp B., Bennington-Mathias C., Hersperger E., et al. , 1996. Molecular, phenotypic, and expression analysis of vein, a gene required for growth of the Drosophila wing disc. Dev. Biol. 177: 475–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M. A., Bowtell D. D., Dodson G. S., Laverty T. R., Rubin G. M., 1991. Ras1 and a putative guanine nucleotide exchange factor perform crucial steps in signaling by the sevenless protein tyrosine kinase. Cell 67: 701–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. K., Carroll P. M., Allard J. D., Simon M. A., 2002. MASK, a large ankyrin repeat and KH domain-containing protein involved in Drosophila receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Development 129: 71–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton H., Melrose J., Little C. B., Fosang A. J., 2011. Proteoglycan degradation by the ADAMTS family of proteinases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1812: 1616–1629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant M. A., Bier E., 1995. Analysis of the genetic hierarchy guiding wing vein development in Drosophila. Development 121: 785–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant M. A., Roark M., Bier E., 1993. The Drosophila rhomboid gene mediates the localized formation of wing veins and interacts genetically with components of the EGF-R signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 7: 961–973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban S., Lee J. R., Freeman M., 2001. Drosophila rhomboid-1 defines a family of putative intramembrane serine proteases. Cell 107: 173–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban S., Lee J. R., Freeman M., 2002. A family of Rhomboid intramembrane proteases activates all Drosophila membrane-tethered EGF ligands. EMBO J. 21: 4277–4286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viloria C. G., Obaya A. J., Moncada-Pazos A., Llamazares M., Astudillo A., et al. , 2009. Genetic inactivation of ADAMTS15 metalloprotease in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 69: 4926–4934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivekanand P., Tootle T. L., Rebay I., 2004. MAE, a dual regulator of the EGFR signaling pathway, is a target of the Ets transcription factors PNT and YAN. Mech. Dev. 121: 1469–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff L., Kelwick R., Decock J., Edwards D. R., 2011. The roles of ADAMTS metalloproteinases in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Front. Biosci. 16: 1861–1872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. H., Simcox A., Campbell G., 2000. Dual role for Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in early wing disc development. Genes Dev. 14: 2271–2276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman J. D., Freeman M., 1998. An autoregulatory cascade of EGF receptor signaling patterns the Drosophila egg. Cell 95: 355–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessells R. J., Grumbling G., Donaldson T., Wang S. H., Simcox A., 1999. Tissue-specific regulation of vein/EGF receptor signaling in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 216: 243–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcinski A., Nakato H., Soula C., Glise B., 2011. DSulfatase-1 fine-tunes Hedgehog patterning activity through a novel regulatory feedback loop. Dev. Biol. 358: 168–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You J., Belenkaya T., Lin X., 2011. Sulfated is a negative feedback regulator of wingless in Drosophila. Dev. Dyn. 240: 640–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zak N. B., Shilo B. Z., 1990. Biochemical properties of the Drosophila EGF receptor homolog (DER) protein. Oncogene 5: 1589–1593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.