Abstract

The extracellular domain of matrix protein 2 (M2e) is conserved among influenza A viruses. The goal of this project is to develop enhanced influenza vaccines with broad protective efficacy using the M2e antigen. We designed a membrane-anchored fusion protein by replacing the hyperimmunogenic region of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium flagellin (FliC) with four repeats of M2e (4.M2e-tFliC) and fusing it to a membrane anchor from influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA). The fusion protein was incorporated into influenza virus M1-based virus-like particles (VLPs). These VLPs retained Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) agonist activity comparable to that of soluble FliC. Mice immunized with the VLPs by either intramuscular or intranasal immunization showed high levels of systemic M2-specific antibody responses compared to the responses to soluble 4.M2e protein. High mucosal antibody titers were also induced in intranasally immunized mice. All intranasally immunized mice survived lethal challenges with live virus, while intramuscularly immunized mice showed only partial protection, revealing better protection by the intranasal route. These results indicate that a combination of M2e antigens and TLR ligand adjuvants in VLPs has potential for development of a broadly protective influenza A virus vaccine.

INTRODUCTION

Influenza is one of the most important viral diseases in humans, with significant medical and economic burdens (23, 31). Vaccination is the most effective approach for prevention of influenza virus infection. However, the major limitations of the current influenza vaccines include the need to produce new vaccines every season and uncertainty in choice of the correct strains, as well as the fact that the vaccines are produced by a slow process requiring embryonated eggs. Because of these limitations, a broadly protective vaccine that is based on relatively conserved protein domains and egg-independent production would be a promising approach (6, 12, 14, 32).

Matrix protein 2 (M2) of influenza A viruses is a highly conserved transmembrane protein exhibiting pH-dependent proton transport activity (1). In human isolates of different subtypes, the extracellular domain (M2e) of M2 is completely conserved in its N-terminal 9 amino acids (aa) and has minor changes in the membrane-proximal region (25). However, because of its low copy number and small size compared to the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase spikes, M2e is poorly immunogenic (4, 42). Nevertheless, some M2e-based vaccine candidates protected immunized mice from low-dose lethal virus challenge (8, 10, 15, 16, 39, 42). Improved protection was also observed when an M2-based virus-like particle (VLP) antigen was used as a supplement to inactivated viral vaccines (36). Thus, M2e is considered a promising antigen for the development of a universal influenza vaccine.

The bacterial flagellins are the natural ligands of Toll-like receptor 5 (TLR5) (35) and can be used as adjuvant (16, 18). In most isolates of Salmonella, two genes encode flagellar antigens. fliC encodes the phase I flagellin FliC, and fljB encodes the phase II flagellin FljB (43), and they are coordinately expressed by a phase-variation mechanism (33). Both FliC and FljB share conserved N and C termini which form the flagellar filament backbone (22) and contain motifs recognized by TLR5. Previously, we have found that a membrane-anchored form of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium phase I flagellin (FliC) can be coincorporated into influenza VLPs as an adjuvant molecule (40). The variable central region of FliC has been found to be hyperimmunogenic and unnecessary for its TLR5 binding activity (35). In the present study, we designed a membrane-anchored fusion protein comprised of FliC with a repetitive M2e replacement of its central variable region and incorporated this into influenza virus M1-based VLPs. We further determined whether these VLPs induce broadly protective immunity in a mouse model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

Mice were sterile housed and treated according to Emory University guidelines, and all animal studies were approved by the Emory University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell lines and viruses.

Spodoptera frugiperda Sf9, Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK; ATCC PTA-6500), and RAW264.7 (ATCC TIB-71) cells were maintained as described previously (40). Mouse-adapted influenza A/PR/8/34 (A/PR8; H1N1) and A/Philippines/2/82 (A/Philippines; H3N2) viruses were prepared as described previously (28). The lethal dose inducing 50% mortality (LD50) of these strains was determined by infection of mice with serial virus dilutions and calculated by the method of Reed and Muench (29).

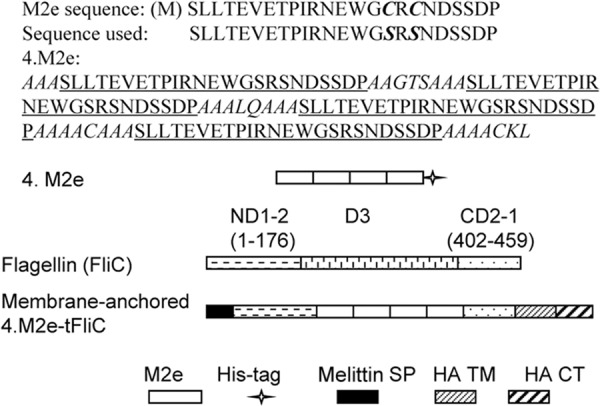

Construction of repetitive M2e (4.M2e) and a membrane-anchored 4.M2e-flagellin fusion protein (4.M2e-tFliC).

Four DNA fragments encoding individual repeats of a consensus M2e sequence (SLLTEVETPIRNEWGSRSNDSSDP) (30) and flexible linker sequences (Fig. 1) were produced by primer-extension PCR and ligated to generate the gene encoding 4.M2e. Two cysteines at sites 17 and 19 of M2e were replaced by serine residues (9), and a 6-histidine tag sequence was added in frame to facilitate the purification of the 4.M2e protein. To generate a gene encoding a fusion protein in which the variable region of FliC is replaced by 4.M2e, the DNA fragment encoding the variable region (aa 177 to 401 in FliC) was deleted from the S. Typhimurium FliC gene (40) and replaced by the 4.M2e-coding sequence. The sequences encoding an N-terminal signal peptide (SP) from honeybee melittin and a C-terminal membrane anchor from the A/PR8 influenza virus HA were added in frame (40) to generate the full-length gene encoding the membrane-anchored fusion protein (Fig. 1). The integrity of constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Fig 1.

Sequences and schematic diagram of constructs. The M2e sequence shown is the consensus of the human influenza A virus M2e sequence. In 4.M2e, four repetitive M2e regions (underlined) are located in a tandem. Sequences in italics are flexible linkers. A 6-histidine tag-encoding DNA was fused in frame. In the membrane-anchored 4.M2e-tFliC, the central immunogenic region of FliC (domain 3 [D3], aa 177 to 401) was replaced by the 4.M2e sequence. The melittin signal peptide (SP) was fused to the N terminus of 4.M2e-tFliC (N-terminal domains 1 and 2 [ND1-2] in FliC) to enable its ectodomain to reach the exocytic pathway and is removed in the mature protein by insect cell signal peptidase (44). The transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains (TM/CT) of A/PR8 virus HA were attached to the C terminus of the 4.M2e-tFliC (C-terminal domains 2 and 1 [CD2-1] in FliC).

Protein and VLP production.

Histidine-tagged recombinant 4.M2e was purified from an Escherichia coli protein expression system as described previously (34). Purified proteins migrated as one band by Coomassie blue staining and Western blotting and were dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and stored at −80°C. A recombinant baculovirus (rBV) expressing the membrane-anchored 4.M2e-tFliC was generated by using a Bac-to-Bac kit (Invitrogen). Recombinant BVs expressing membrane-anchored FliC and M1 were described previously (40). The 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs were produced by coinfection of Sf9 cells with rBVs expressing the membrane-anchored 4.M2e-tFliC and M1 at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of 6 and 3, respectively. The M2e content in 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs was 1.5% when normalized by Western blotting using purified 4.M2e as a standard. VLPs were concentrated from the supernatants of Sf9 cell culture and characterized by protein assay, Western blotting, sterility assay, and electron microscopy (EM), as described previously (40).

TLR5-specific bioactivity assay.

The TLR5-activating activities of the recombinant protein and VLPs were evaluated using a RAW264.7 cell-based assay (40). After a 24-h treatment, levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) production stimulated by proteins or VLPs in both TLR5-positive and -negative cell cultures in supernatants were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a TNF-α assay kit (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). TLR5 bioactivity was presented as the level of TNF-α production in TLR5-positive cells subtracted from that in TLR5-negative cells.

Immunization and challenge.

Groups of six inbred female BALB/c mice (from Charles River Laboratories) were immunized three times with 10 μg 4.M2e or 50 μg 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 (VLPs equal to 0.75 μg M2e) by either the intramuscular (i.m.) or intranasal (i.n.) route at 4-week intervals. Preimmune sera were collected at 1 week before prime immunization. Immune sera and lung lavage samples were collected at 4 weeks after the last immunization. Blood samples were collected by retro-orbital plexus puncture. For virus challenge, mice were lightly anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane, and 5 LD50s of mouse-adapted A/PR8 or A/Philippines virus (in 25 μl PBS) were administered into the mouse nostrils. Mouse body weight and survival were monitored daily for 15 days. Mice were sacrificed at day 4 postinfection to determine lung virus loads. Lung virus titers were determined as previously described (40).

Antibody responses.

M2e-specific serum IgG endpoint titers were determined by ELISA as described previously (28) using synthesized M2e peptide-coated 96-well ELISA plates (Nunc Life Technologies). Serum M2-specific antibody levels were also determined using cell surface ELISA (16). MDCK cells in 96-well culture plates (90% confluence) were infected with A/PR8 virus at an MOI of 1 (5 × 104 PFU). After 12 h of growth, the plates were washed and the cells were fixed with 0.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 30 min. After three washes with PBS, test sera were added to the wells in 80-fold dilutions and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Antibody binding to uninfected MDCK cells was subtracted as background. M2-specific antibody levels were presented as the value of the optical density at 450 nm (OD450).

At 4 weeks postimmunization, mouse lungs were collected and lavaged twice with 1 ml PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 per lung. The mucosal responses, expressed as endpoint titers of M2e-specific IgA and IgG, were determined in lung lavage fluid of immunized mice by ELISA, as previously described (28), using horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgA or IgG as developing antibodies.

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were repeated at least twice in this study. Comparisons of vaccinated groups were performed using a nonmatching two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni's posttest. Comparison of survival curves was performed using a log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. The analyses were done by using GraphPad Prism (version 5.00) software for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characterization of VLPs.

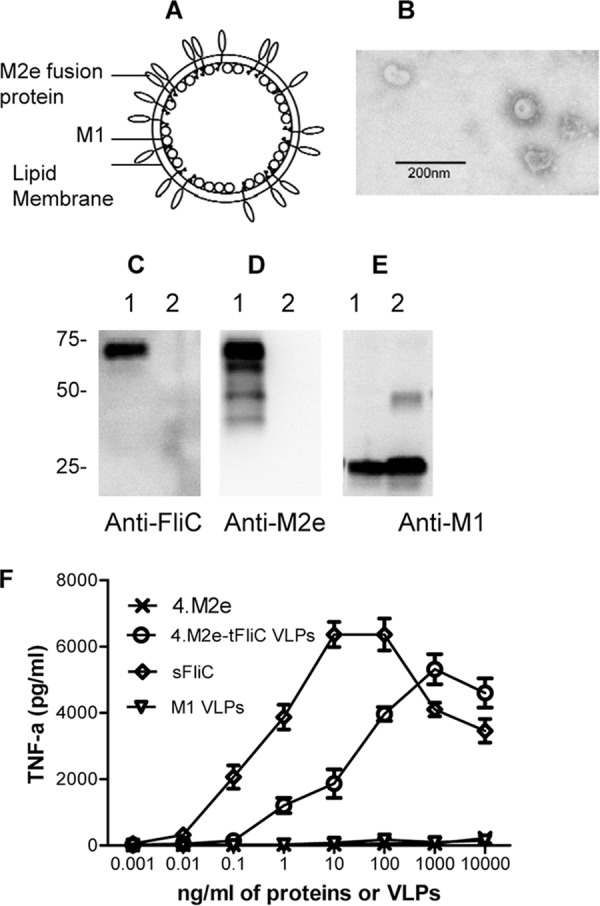

To improve the immunogenicity of M2e, the membrane-anchored 4.M2e-tFliC protein was incorporated into influenza virus M1 VLPs (Fig. 2A), and the incorporation was confirmed by Western blotting assays using either anti-FliC antibody (Fig. 2C, lane 1) or anti-M2e antibody (14C2; Fig. 2D, lane 1). The integrity of VLPs was confirmed by electron microscopy (Fig. 2B). We also produced VLPs containing M1 only (Fig. 2E, lane 2) as controls.

Fig 2.

Characterization of 4.M2e-tFliC VLPs. (A) Diagram of influenza virus 4.M2e-tFliC VLPs. The membrane-anchored form of the 4.M2e-tFliC is inserted into the lipid bilayer of the envelope. (B) Negative-stain EM of VLP. (C to E) Characterization of VLPs. VLP samples were applied to SDS-polyacrylamide gels, followed by Western blotting. Lanes 1, 4.M2e-tFliC VLPs; lanes 2, M1-only VLPs. Protein bands were detected by mouse anti-FliC antibody (FliC-1) (C), mouse anti-M2e antibody (14C2) (D), and anti-M1 antibody (GA2B; Abcam) (E). (F) TLR5 agonist activity of flagellin. The mouse macrophage cell line RAW264.7, which expresses TLR2 and TLR4 without TLR5, was used to determine the bioactivity of 4.M2e-tFliC VLPs. Soluble recombinant FliC (sFliC) was used as a positive control; M1-only VLPs and recombinant 4.M2e were used as negative controls. TLR5-expressing RAW264.7 cells were prepared by transfection with the vector pUNO-hTLR5 expressing the human TLR5, as described previously (40). Data represent means ± standard deviations (SDs) from triplicate repeats.

Because TLR5 is the known extracellular sensor of flagellin, we determined the ability of the membrane-anchored 4.M2e-tFliC in VLPs to function as a TLR5 ligand. As shown in Fig. 2F, 4.M2e-tFliC showed TLR5-specific bioactivity, inducing mouse macrophage cell line RAW264.7 to produce TNF-α over a concentration range of 0.01 ng to 1,000 ng/ml. The 50% effective concentration (the concentration which produces 50% of maximal activity [EC50]) of the 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs was 60 ng/ml, while that of the soluble flagellin was 0.8 ng/ml. Considering that the soluble FliC has a much lower molecular weight than the VLPs, their relative EC50 titers are within the expected ranges.

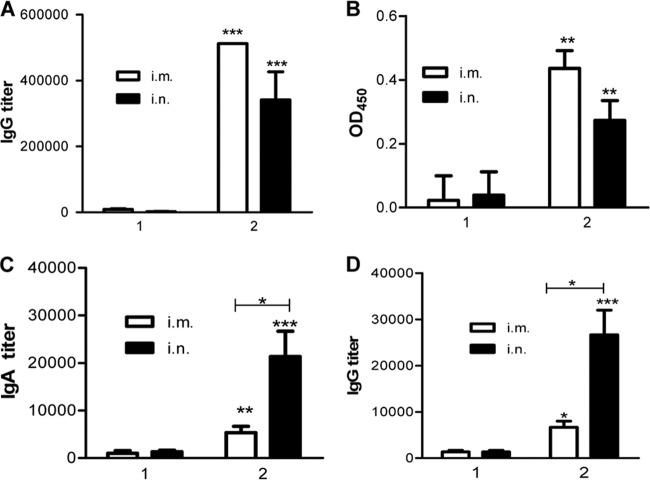

4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs induce high IgG responses.

To evaluate the potential of 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs to be universal influenza vaccines, the immune responses induced by either i.m. or i.n. immunization were compared. The result in Fig. 3A shows that the 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs trigger robust M2e-specific humoral responses in mice immunized i.m. or i.n. compared to those triggered by recombinant 4.M2e (P < 0.001), which induced only low titers of anti-M2e IgG. The serum IgG titers in i.m. and i.n. immunizations were 6.5 × 105 and 4.0 × 105, respectively.

Fig 3.

Antibody responses. (A) Serum IgG recognizing M2e in immunized mice. To determine serum M2e-specific IgG titers, ELISA plates were coated with 100 μl/well of synthesized M2e peptide (5 μg/ml; at the Emory University Biochemical Core Facility). (B) Endpoint titers of IgG recognizing native M2 protein. MDCK cells were infected with A/PR8 viruses at an MOI of 1. Uninfected cells were used as a control. At 12 h postinfection, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with 0.5% glutaraldehyde. Samples diluted 80-fold were applied to detect antibody binding, as described in Materials and Methods. Data depict the OD450 (mean ± SD) with infected cells, with the background of uninfected cells subtracted. Groups 1 and 2 represent mouse groups immunized with 4.M2e and 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs, respectively. (C) Lung lavage IgA. IgA endpoint titers were determined as described for the serum IgG endpoint titer in panel A, but the secondary antibody used was HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgA antibody. (D) Lung lavage IgG. Representative data are the geometric mean (GM) ± 95% confidence interval (CI) of six mice in each group at 4 weeks after the last immunization. Asterisks on the top of a bar present the statistical difference of the group to its counterpart in the M2e group. The statistical difference between other groups is labeled with a connecting line. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Although the 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs induced high levels of M2e-specific antibody responses, only antibodies capable of targeting native tetrameric M2 may confer protection (42). Influenza virus-infected MDCK cells express high levels of M2 on the cell membrane and can be used to determine M2-specific antibody binding (36). Therefore, we further evaluated antibody binding to native M2 protein by an MDCK cell-based ELISA. As shown in Fig. 3B, antibodies in immune sera recognized and bound M2 expressed on MDCK cell surfaces, as determined by ELISA. Sera from the 4.M2e peptide-immunized mice showed very low binding close to background. In contrast, 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs induced significantly higher M2-specific antibody responses (P < 0.01) by either i.m. or i.n. immunization. Comparatively, the i.m. route showed a trend to induce higher systemic immune responses than the i.n. route, although the difference between the i.m. and i.n. routes was not statistically significant (Fig. 3A and B). The levels of antibody binding to M2 on cell surfaces in all groups showed a pattern similar to the M2e-specific IgG ELISA titers, demonstrating that the M2e-specific antibodies confer M2 recognition and are correlated with binding to the native M2.

4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs induce strong mucosal immune responses.

The respiratory tract is the dominant site of influenza virus infection and replication, and effective mucosal antibody responses can prevent the initiation of viral infection in the respiratory tract (5). The results shown in Fig. 3 indicate that 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs induced higher titers of M2e-specific IgA (Fig. 3C) and IgG (Fig. 3D) in mouse lungs after i.n. immunization than 4.M2e did (P < 0.001) and the advantage of the i.n. immunization route in inducing mucosal immune responses (P < 0.05). These data demonstrate that flagellin is effective as a mucosal adjuvant when fused with M2e antigen in VLPs.

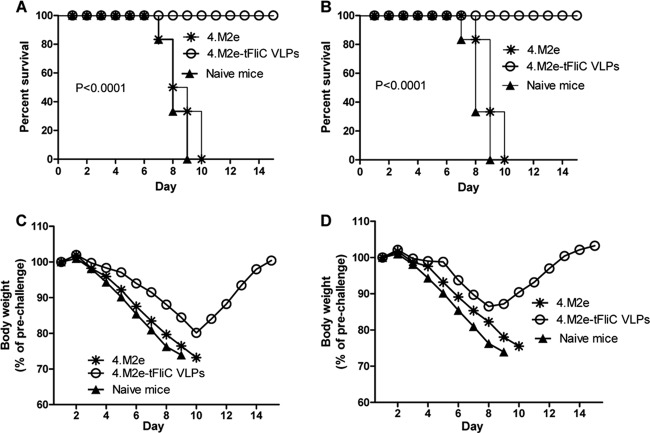

Breadth of protective efficacy.

To determine whether the above-described vaccine candidates confer enhanced protection against virus challenge, immunized mice were challenged i.n. with 5 LD50s (250 PFU) of mouse-adapted A/Philippines (H3N2) virus in which M2e has the same sequence as the consensus sequence used. As shown in Fig. 4, mice in both the i.m. and i.n. groups immunized with 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs completely survived the H3N2 virus challenges (Fig. 4A and B). However, mice in the i.n. group lost less body weight (11%; Fig. 4C) than mice in the i.m. group (18%, Fig. 4D). Mice immunized with 4.M2e protein, as well as the naive mice, reached their endpoints (25% body weight loss; Fig. 4) at day 7 to 10.

Fig 4.

A/Philippines (H3N2) live virus challenge. Four weeks after the last immunization, 6 mice of each group were infected i.n. with 5 LD50s of mouse-adapted A/Philippines viruses (250 PFU). Survival of mouse groups immunized i.m. (A) or i.n. (B) and body weight changes of i.m. (C) and i.n. (D) groups were monitored and recorded for 15 days to indicate the protective efficacy of the vaccines. In panels C and D, the data represent means of the body weight change (percentage of prechallenge body weight) of 6 mice in each group.

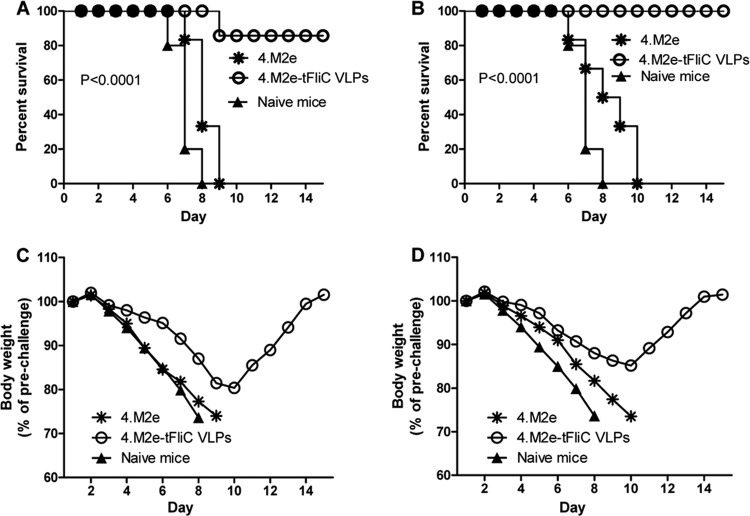

We further evaluated the protection against A/PR8 (H1N1) virus challenge induced by the above-described vaccine candidates. The M2e sequence of A/PR8 virus M2 has 1 aa different from the consensus sequence used, and no other human influenza virus shares this M2e sequence. We found that mice immunized i.m. with 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs partially survived A/PR8 virus challenge at a dose of 5 LD50s (5 of 6 mice; Fig. 5A) with a 19% body weight loss (Fig. 5C). In contrast, mice in the i.n. group completely survived the challenge (Fig. 5B) but lost 13% body weight (Fig. 5D). Mice in the 4.M2e protein group, as well as the naive mice, reached 25% weight loss endpoints. These results demonstrate that the M2e vaccines induced better protection against viruses having less of an amino acid difference in M2, consistent with our previous observations (36, 37).

Fig 5.

A/PR8 (H1N1) virus challenge. Four weeks after the last immunization, mice were infected i.n. with 5 LD50s of mouse-adapted A/PR8 virus (125 PFU). Survival of mouse groups immunized i.m. (A) or i.n. (B) and body weight changes of groups immunized i.m. (C) or i.n. (D) were monitored and recorded as described in the legend to Fig. 4.

A common feature of the above-described challenge results is that immunity induced by the i.n. route is more effective in providing protection against influenza virus infection. i.m. immunizations induced higher titers of serum M2-specific IgG responses than i.n. immunizations, as shown in Fig. 3, but the i.n. vaccination induced better protection, demonstrating the advantage of mucosal immunity in M2e-induced protection. These data demonstrate that the M2e-specific antibodies, in particular, the mucosal antibodies, correlate with protective efficacy.

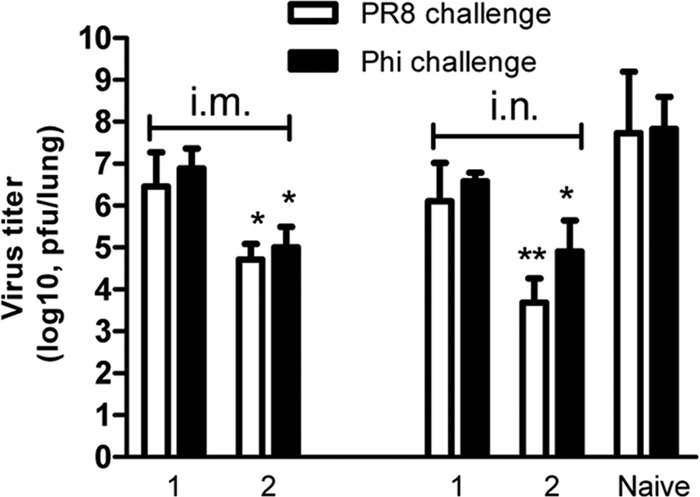

Because the M2e-specific antibodies do not neutralize the infectivity of influenza viruses but instead may exert their protective effect at the level of the infected cell (15, 17, 39, 42), we further evaluated the effect of 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs in decreasing viral replication in the lung. As shown in Fig. 6, all surviving groups have lung virus loads lower than 1 × 104 for the A/PR8 challenge virus or 1 × 105 for A/Philippines challenge virus. In the 4.M2e-tFliC VLP group, mice receiving i.n. immunization showed a 10-fold lower lung viral load than those receiving i.m. immunization with A/PR8 virus challenge and a 1.25-fold lower lung viral load with A/Philippines virus challenge. These results further demonstrate the advantage of mucosal immunization for protection against influenza.

Fig 6.

Lung viral load on day 4 postchallenge. Four weeks after the last immunization, three mice in each group were infected i.n. with 5 LD50s of mouse-adapted A/PR8 (H1N1) or A/Philippines (Phi; H3N2) virus. Mouse lungs were collected on day 4 postchallenge. Each lung was ground and cleared in 1 ml of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium. Virus titers of lung extracts were titrated using a standard plaque assay with MDCK cells. Lung viral titer was expressed as the number of PFU/lung. Data depict means ± SDs of three mice from each group. Groups 1 and 2 represent mouse groups immunized i.m. or i.n. with 4.M2e and 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs, respectively. Statistically significant differences between immunized groups and the naive group are indicated: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Because it is highly conserved in all A-type influenza viruses, M2e has been studied as a universal influenza vaccine (8, 10, 16, 26). Here we used a combined approach to target M2e for the development of such a vaccine. First, multiple copies of M2e (4.M2e) in our vaccine candidates increased the density of epitopes. Second, replacement of the highly immunogenic variable region of FliC with 4.M2e may endow M2e with high immunogenicity because the resulting 4.M2e-tFliC fusion protein retains the TLR5 ligand property of FliC. VLPs are advantageous as immunogens in inducing strong immune responses since they mimic the structures of viruses which the immune system has evolved to fight. The HA cytoplasmic domain contains signals guiding the envelope glycoprotein to assemble into VLPs (7). Previously, we have found that a fusion protein with an HA membrane anchor can be incorporated into M1 VLPs (40). The VLP approach enables M2e to be delivered in a particulate form and to be presented in its native external membrane microenvironment. Particulate repetitive epitopes are more effective antigens because of their increased epitope density (13, 20, 21). Several groups have also reported enhanced immune responses induced by physical repeats of M2e (11, 16). The potential of this approach has been demonstrated by inducing a high level of M2-specific immunity and complete protection against lethal live virus challenge, as shown in the present study.

As the natural ligand of TLR5, flagellin has been found to be an effective adjuvant. It has been used to enhance the immunogenicity of antigens in mixtures with antigens and the physical association as fusion proteins, and it has been coincorporated into the same particles with antigens (16, 24, 40). The replacement of the variable region of FliC with 4.M2e should not impair its innate TLR signaling because flagellins from different bacterial strains show significant differences in their variable regions (2, 35). A fusion protein composed of 4 repeating M2e peptides attached to the C terminus of the phase II flagellin (FljB) was reported to induce partial protection in mice against a lethal influenza virus infection with reduced clinical symptoms (16). Our results demonstrate that the membrane-anchored 4.M2e-tFliC in VLPs retains innate TLR5 signaling activity. As expected, these VLPs induced high levels of M2e-specific immune responses, in particular when they were given by i.n. immunization, in which complete protection against either A/PR8 or A/Philippines virus with little body weight loss was induced. These promising results are probably derived from the advantages of our approach: the physical association of the FliC TLR5 binding domains with 4.M2e and the replacement of the FliC hyperimmunogenic central region with 4.M2e. Also, these results are consistent with results reported in other studies which indicate that the TLR5 recognition domains of flagellin are not associated with the central variable region (2, 35) and that a variable region-truncated FliC is more effective as a mucosal adjuvant (27). Because the variable region of FliC is hyperimmunogenic, another advantage of the approach is that replacement of the variable region of FliC with M2e sequences minimizes antibody responses to FliC (27), although other work showed that induction of anti-FliC antibody is not a limitation for its adjuvant properties (3, 40).

Several different immunization routes have been used to deliver M2e-derived antigens for inducing protective immunity. i.n. immunization was reported to be an advantageous approach in inducing protective immunity compared to other routes (9). Our results also demonstrated that i.n. immunization with 4.M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs induces high systemic immune responses as well as strong mucosal immunity and confers more effective protection against live virus challenge, as demonstrated by the complete protection against challenge with H1N1- or H3N2-subtype viruses with minimal body weight loss. Also, virus replication in the lungs of immunized mice is restricted, as revealed by lower lung virus titers, although they are still higher than those in the lungs of mice immunized with HA-containing VLPs (40, 41). i.n. immunization stimulates the nasopharynx-associated lymphoreticular tissue and induces local mucosal immunity (19). Furthermore, the variable region-truncated flagellin has been reported to be more efficient as a mucosal adjuvant, as discussed above. These observations provide a basis for the finding that the M2e-tFliC/M1 VLPs induce enhanced mucosal immunity.

Because the M2-specific antibodies are not neutralizing and recent work demonstrated that M2 VLP antigens used in combination with the trivalent influenza vaccines or inactivated viral vaccines showed enhanced subtypic protection (36, 38), the approaches described here provide new alternatives for such combinations. Thus, a fusion protein containing a replacement of the variable region of FliC with repetitive M2e in VLPs is promising for further development of universal influenza A virus vaccines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants AI068003, AI093772, and AI087782 from the National Institutes of Health.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

We thank Erin-Joi Collins for her valuable assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 May 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Acharya R, et al. 2010. Structure and mechanism of proton transport through the transmembrane tetrameric M2 protein bundle of the influenza A virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:15075–15080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andersen-Nissen E, et al. 2005. Evasion of Toll-like receptor 5 by flagellated bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9247–9252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ben-Yedidia T, Arnon R. 1998. Effect of pre-existing carrier immunity on the efficacy of synthetic influenza vaccine. Immunol. Lett. 64:9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Black RA, Rota PA, Gorodkova N, Klenk HD, Kendal AP. 1993. Antibody response to the M2 protein of influenza A virus expressed in insect cells. J. Gen. Virol. 74(Pt 1):143–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brandtzaeg P. 2003. Role of mucosal immunity in influenza. Dev. Biol. (Basel) 115:39–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carrat F, Flahault A. 2007. Influenza vaccine: the challenge of antigenic drift. Vaccine 25:6852–6862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen BJ, Leser GP, Morita E, Lamb RA. 2007. Influenza virus hemagglutinin and neuraminidase, but not the matrix protein, are required for assembly and budding of plasmid-derived virus-like particles. J. Virol. 81:7111–7123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. De Filette M, et al. 2008. An influenza A vaccine based on tetrameric ectodomain of matrix protein 2. J. Biol. Chem. 283:11382–11387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. De Filette M, et al. 2005. Universal influenza A vaccine: optimization of M2-based constructs. Virology 337:149–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Denis J, et al. 2008. Development of a universal influenza A vaccine based on the M2e peptide fused to the papaya mosaic virus (PapMV) vaccine platform. Vaccine 26:3395–3403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eliasson DG, et al. 2008. CTA1-M2e-DD: a novel mucosal adjuvant targeted influenza vaccine. Vaccine 26:1243–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fan J, et al. 2004. Preclinical study of influenza virus A M2 peptide conjugate vaccines in mice, ferrets, and rhesus monkeys. Vaccine 22:2993–3003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fehr T, Skrastina D, Pumpens P, Zinkernagel RM. 1998. T cell-independent type I antibody response against B cell epitopes expressed repetitively on recombinant virus particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:9477–9481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gerhard W, Mozdzanowska K, Zharikova D. 2006. Prospects for universal influenza virus vaccine. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:569–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hughey PG, et al. 1995. Effects of antibody to the influenza A virus M2 protein on M2 surface expression and virus assembly. Virology 212:411–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huleatt JW, et al. 2008. Potent immunogenicity and efficacy of a universal influenza vaccine candidate comprising a recombinant fusion protein linking influenza M2e to the TLR5 ligand flagellin. Vaccine 26:201–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jegerlehner A, Schmitz N, Storni T, Bachmann MF. 2004. Influenza A vaccine based on the extracellular domain of M2: weak protection mediated via antibody-dependent NK cell activity. J. Immunol. 172:5598–5605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Le Moigne V, Robreau G, Mahana W. 2008. Flagellin as a good carrier and potent adjuvant for Th1 response: study of mice immune response to the p27 (Rv2108) Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen. Mol. Immunol. 45:2499–2507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liang B, Hyland L, Hou S. 2001. Nasal-associated lymphoid tissue is a site of long-term virus-specific antibody production following respiratory virus infection of mice. J. Virol. 75:5416–5420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu W, Chen YH. 2005. High epitope density in a single protein molecule significantly enhances antigenicity as well as immunogenicity: a novel strategy for modern vaccine development and a preliminary investigation about B cell discrimination of monomeric proteins. Eur. J. Immunol. 35:505–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu W, et al. 2004. High epitope density in a single recombinant protein molecule of the extracellular domain of influenza A virus M2 protein significantly enhances protective immunity. Vaccine 23:366–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McQuiston JR, et al. 2004. Sequencing and comparative analysis of flagellin genes fliC, fljB, and flpA from Salmonella. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1923–1932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meltzer MI, Bridges CB. 2003. Economic analysis of influenza vaccination and treatment. Ann. Intern. Med. 138:608–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mizel SB, et al. 2009. Flagellin-F1-V fusion protein is an effective plague vaccine in mice and two species of nonhuman primates. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:21–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mozdzanowska K, et al. 2003. Induction of influenza type A virus-specific resistance by immunization of mice with a synthetic multiple antigenic peptide vaccine that contains ectodomains of matrix protein 2. Vaccine 21:2616–2626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Neirynck S, et al. 1999. A universal influenza A vaccine based on the extracellular domain of the M2 protein. Nat. Med. 5:1157–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nempont C, et al. 2008. Deletion of flagellin's hypervariable region abrogates antibody-mediated neutralization and systemic activation of TLR5-dependent immunity. J. Immunol. 181:2036–2043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Quan FS, Huang C, Compans RW, Kang SM. 2007. Virus-like particle vaccine induces protective immunity against homologous and heterologous strains of influenza virus. J. Virol. 81:3514–3524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493–497 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schotsaert M, De Filette M, Fiers W, Saelens X. 2009. Universal M2 ectodomain-based influenza A vaccines: preclinical and clinical developments. Expert Rev. Vaccines 8:499–508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schultz-Cherry S, et al. 2000. Influenza virus (A/HK/156/97) hemagglutinin expressed by an alphavirus replicon system protects chickens against lethal infection with Hong Kong-origin H5N1 viruses. Virology 278:55–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schwartz B, et al. 2006. Universal influenza vaccination in the United States: are we ready? Report of a meeting. J. Infect. Dis. 194(Suppl. 2):S147–S154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Silverman M, Zieg J, Hilmen M, Simon M. 1979. Phase variation in Salmonella: genetic analysis of a recombinational switch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76:391–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Skountzou I, et al. 2010. Salmonella flagellins are potent adjuvants for intranasally administered whole inactivated influenza vaccine. Vaccine 28:4103–4112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smith KD, et al. 2003. Toll-like receptor 5 recognizes a conserved site on flagellin required for protofilament formation and bacterial motility. Nat. Immunol. 4:1247–1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Song JM, Van Rooijen N, Bozja J, Compans RW, Kang SM. 2011. Vaccination inducing broad and improved cross protection against multiple subtypes of influenza A virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:757–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Song JM, et al. 2011. Influenza virus-like particles containing M2 induce broadly cross protective immunity. PLoS One 6:e14538 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Talbot HK, et al. 2010. Immunopotentiation of trivalent influenza vaccine when given with VAX102, a recombinant influenza M2e vaccine fused to the TLR5 ligand flagellin. PLoS One 5:e14442 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Treanor JJ, Tierney EL, Zebedee SL, Lamb RA, Murphy BR. 1990. Passively transferred monoclonal antibody to the M2 protein inhibits influenza A virus replication in mice. J. Virol. 64:1375–1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang BZ, et al. 2008. Incorporation of membrane-anchored flagellin into influenza virus-like particles enhances the breadth of immune responses. J. Virol. 82:11813–11823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang BZ, et al. 2010. Intranasal immunization with influenza VLPs incorporating membrane-anchored flagellin induces strong heterosubtypic protection. PLoS One 5:e13972 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zebedee SL, Lamb RA. 1988. Influenza A virus M2 protein: monoclonal antibody restriction of virus growth and detection of M2 in virions. J. Virol. 62:2762–2772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zieg J, Silverman M, Hilmen M, Simon M. 1977. Recombinational switch for gene expression. Science 196:170–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zimmermann R, Mollay C. 1986. Import of honeybee prepromelittin into the endoplasmic reticulum. Requirements for membrane insertion, processing, and sequestration. J. Biol. Chem. 261:12889–12895 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]