Abstract

Previous studies of mice have demonstrated that an orchestrated sequence of innate and adaptive immune responses is required to control West Nile virus (WNV) infection in peripheral and central nervous system (CNS) tissues. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL; also known as CD253) has been reported to inhibit infection with dengue virus, a closely related flavivirus, in cell culture. To determine the physiological function of TRAIL in the context of flavivirus infection, we compared the pathogenesis of WNV in wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice. Mice lacking TRAIL showed increased vulnerability and death after subcutaneous WNV infection. Although no difference in viral burden was detected in peripheral tissues, greater viral infection was detected in the brain and spinal cord at late times after infection, and this was associated with delayed viral clearance in the few surviving TRAIL−/− mice. While priming of adaptive B and T cell responses and trafficking of immune and antigen-specific cells to the brain were undistinguishable from those in normal mice, in TRAIL−/− mice, CD8+ T cells showed qualitative defects in the ability to clear WNV infection. Adoptive transfer of WNV-primed wild-type but not TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells to recipient CD8−/− mice efficiently limited infection in the brain and spinal cord, and analogous results were obtained when wild-type or TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells were added to WNV-infected primary cortical neuron cultures ex vivo. Collectively, our results suggest that TRAIL produced by CD8+ T cells contributes to disease resolution by helping to clear WNV infection from neurons in the central nervous system.

INTRODUCTION

West Nile virus (WNV) is a mosquito-transmitted neurotropic flavivirus that is genetically related to other viruses causing global human disease, including dengue virus (DENV), yellow fever virus, and Japanese and tick-borne encephalitis viruses. WNV cycles in nature between birds and Culex mosquitoes but can infect and cause severe neuroinvasive disease in other vertebrate animals, including humans (25). While the majority of human WNV infections are asymptomatic, a subset of individuals develop a systemic febrile illness, with a few progressing to meningitis, encephalitis, or an acute flaccid paralysis syndrome (32). Severe and symptomatic WNV infection occurs more frequently in the elderly or immunocompromised and in individuals homozygous for the CCR5Δ32 mutation (11, 18, 19, 24). Since 1999, in the United States, more than 30,000 cases of symptomatic WNV infection have been confirmed, although seroprevalence analysis estimates a much larger number of infections in the population (4). Currently, there is no approved therapy or vaccine for WNV infection in humans.

Studies of mice have helped to elucidate how the integrity of the innate and adaptive immune systems is required for resistance to WNV infection. Using mice with targeted deletions in individual immune response genes, significant and protective contributions from inflammatory cytokines (e.g., type I and II interferons [IFNs]), chemokines, complement, B cells, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have been observed (reviewed in references 7 and 27). In particular, receptor-ligand interactions of two members (tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]–TNF-α receptor and Fas-Fas ligand [Fas-FasL]) of the TNF superfamily of proteins are protective against WNV within the central nervous system (CNS). Antigen-specific CD8+ T cells use Fas ligand effector mechanisms to contain WNV infection in Fas-expressing neurons in the CNS (34), whereas TNF-α interaction with TNF receptor 1 (TNF-R1) protects against WNV infection by regulating migration of protective inflammatory cells into the brain during acute infection (38).

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (CD253 or TRAIL) is a 281-amino-acid type II transmembrane protein of the TNF superfamily. The C-terminal extracellular domain is cleaved by cell-associated proteases, resulting in a soluble TRAIL that forms a homotrimer and circulates in the bloodstream. Soluble or cell-associated human TRAIL binds to the death receptors DR4 (TRAIL-R1) and DR5 (TRAIL-R2) on tumor cells, resulting in recruitment of FADD (Fas-associated death domain), activation of caspase-8, and apoptosis of transformed cells. In addition, TRAIL also binds to decoy receptors DcR1 (TRAIL-R3) and DcR2 (TRAIL-R4), which either lack a cytoplasmic domain or contain a truncated one. TRAIL binding to DcR1 and DcR2 does not promote apoptosis but instead neutralizes TRAIL function (22) or promotes NF-κB activation and transcription of proinflammatory genes (13, 20). TRAIL binding to its receptors on nontumor cells commonly does not trigger apoptosis. Such regulation is controlled by the binding of the endogenous inhibitor of death receptor killing, i.e., cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein (c-FLIP), to the intracellular domain of TRAIL receptors (23) and by expression of the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) (26). Thus, the physiological role of TRAIL remains less well understood. TRAIL is induced as a consequence of type I and II IFN signaling in several cell types (14) and has been reported to have anti-inflammatory properties (30), which can mitigate excessive and maladaptive host immune responses in the brain (12). In mice, TRAIL binding to DR5 has been proposed to negatively regulate cellular innate immune responses (9).

TRAIL has also been suggested to have inhibitory functions against several viruses in vivo. Administration of a blocking but non-cell-depleting anti-TRAIL antibody to mice during influenza virus infection delayed virus clearance in the lung (15), and analogously, TRAIL−/− mice showed increased disease severity after influenza virus infection (2, 3). In addition, type I IFN signaling induced TRAIL expression in NK cells, which facilitated control of encephalomyocarditis virus in vivo (29). Some of the antiviral effects of TRAIL may be mediated by the decoy receptors DcR1 and DcR2, as DR5−/− mice show lower titers of murine cytomegalovirus in the spleen and higher levels of type I IFN (9). More recently, a role for TRAIL-dependent protection against flaviviruses was suggested (40). DENV infection induced TRAIL expression in blood-derived immune cells, primary myoblasts, and human endothelial cells, in a type I IFN-dependent manner, and exogenous recombinant TRAIL inhibited DENV infection in human myeloid cells through an apoptosis-independent mechanism.

To determine the physiological relevance of TRAIL in the context of infection by a flavivirus, we compared the virulence of WNV in wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice. We found that a deficiency of TRAIL was associated with an increased viral burden in the CNS, delayed clearance, and enhanced mortality, despite normal priming of adaptive B and T cell immune responses and trafficking to the brain. However, CD8+ T cells showed qualitative defects in the ability to clear WNV infection. Our experiments suggest that CD8+ T cells utilize TRAIL to control WNV infection in neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus.

The WNV strain (3000.0259) was isolated in New York in 2000 and passaged once in C6/36 Aedes albopictus cells to generate a stock virus as described previously (10).

Mouse experiments.

C57BL/6 wild-type inbred mice were obtained commercially (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME). Congenic, backcrossed TRAIL−/− mice were obtained from Jonathan Weiss (NIH, Bethesda, MD) and rederived prior to initiation of infection experiments. All mice were genotyped and bred under pathogen-free conditions in the animal facilities of the Washington University School of Medicine, and experiments were performed in accordance with and with approval of the Washington University animal study guidelines. Eight- to 10-week-old mice were inoculated with 101 and 102 PFU by the intracranial and subcutaneous routes, respectively.

Quantitation of tissue viral burden and viremia.

To determine the extent of viral spread in vivo, wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice were infected with WNV by subcutaneous (via footpad injection) or intracranial inoculation and euthanized at specific time points. Blood was collected by intracardiac puncture, and serum was isolated and stored aliquoted at −80°C. After extensive tissue perfusion with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C, organs were harvested and homogenized using a bead beater apparatus, and infectious virus was titrated by plaque assay on BHK21-15 cells (8). For measurement of infectious virus in serum, plaque assays were performed on Vero cells (35).

Measurement of WNV-specific antibodies.

To determine the levels of WNV-specific antibody, IgM and IgG were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with purified WNV E protein as described previously (21). The titer was defined as the serum dilution yielding an optical density at 450 nm equivalent to three times above the background of the assay. The titer of neutralizing antibody was determined by using a plaque reduction neutralization assay with BHK21-15 cells (36). Plaques were counted visually and plotted, and the plaque reduction neutralization titer for 50% inhibition (PRNT50) was calculated using GraphPad Prism software.

Analysis of splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

WNV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen were analyzed as described previously (34). Briefly, splenocytes were harvested from wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice on day 8 after infection. After lysis of erythrocytes in hypotonic solution, 106 cells were stimulated with 0.2 μg/ml of an immunodominant Db-restricted WNV-specific NS4B peptide (SSVWNATTAI) or anti-CD3 antibody (2C11) for 6 h at 37°C in the presence of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). Splenocytes were stained with anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 antibody (BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C. After being washed in PBS supplemented with 5% goat serum, cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized with saponin, and stained with anti-IFN-γ or anti-TNF-α antibody (BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C. After a final series of washes, cells were processed by flow cytometry, and the percentages of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells that expressed IFN-γ or TNF-α were determined using CellQuest (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo (Treestar) software. In separate experiments, splenocytes were stained at 4°C for 30 min with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-CD8 antibody (BD Biosciences) and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated Db-restricted NS4B peptide (SSVWNATTAI) tetramers (prepared by the NIH Tetramer Facility, Atlanta, GA). Uninfected mice were used as controls in all experiments. The number and percentage of CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the spleens of WNV-infected wild-type or TRAIL−/− mice were measured using a regulatory T cell staining kit (eBioscience). Samples were processed by multicolor flow cytometry on an LSR II flow cytometer (Becton, Dickinson and Company) and then analyzed with FlowJo software (Treestar).

CNS leukocytes.

Leukocytes were isolated from the brains of infected animals and quantified as described previously (36). Briefly, 8 days after subcutaneous infection with 102 PFU of WNV, brains were harvested after extensive perfusion with PBS, dispersed into single-cell suspensions, and digested with 0.05% collagenase D, 0.1 μg/ml trypsin inhibitor TLCK (Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone), 10 μg/ml DNase I (all from Sigma Chemical), and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, in Hanks' balanced salt solution for 1 h. Leukocytes were isolated by discontinuous Percoll gradient (70%-37%-30%) centrifugation for 30 min (850 × g at 4°C). After washing and counting, cells were stained for CD4, CD8, CD45, and CD11b by use of directly conjugated antibodies (BD Biosciences) for 30 min at 4°C and then fixed with PBS supplemented with 1% paraformaldehyde. In some experiments, isolated brain leukocytes were restimulated with Db-restricted NS4B peptide or anti-CD3 antibody for 6 h, and IFN-γ- and TNF-α-producing CD8+ T and CD4+ T cells were measured. Alternatively, brain leukocytes were incubated with the NS4B tetramer and anti-CD8 to detect WNV-specific CD8+ T cells. Samples were processed by multicolor flow cytometry on an LSR II flow cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo software.

Primary cell isolation and infection.

Primary cortical neurons were prepared from 15-day-old embryos as described previously (28). Cortical neurons were seeded in 24-well poly-d-lysine- and laminin-coated plates in neurobasal medium containing B27 and l-glutamine (Invitrogen) for 24 h. The medium was replaced, and neurons were cultured for three additional days prior to infection. Multistep virus growth analysis was performed with primary cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. Supernatants were harvested 6, 24, 48, and 72 h after infection and titrated by plaque assay on BHK21-15 cells as described previously (8). In some experiments, recombinant TRAIL (0.078 to 20 μg/ml; Enzo Life Sciences) was added 24 h before or 1 h after WNV infection.

Adoptive transfer of wild-type or TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells.

CD8+ T cells from WNV-infected mice were purified and transferred as described previously (37). Splenocytes were harvested from naïve or primed wild-type or TRAIL−/− mice on day 7 after WNV infection. CD8+ T cells were purified by positive selection using antibody-coated magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) and transferred into CD8−/− mice 1 day after WNV infection. In pilot experiments, we confirmed that equivalent numbers and percentages of wild-type (4.0% ± 1.6% of total lymphocytes) and TRAIL−/− (4.5% ± 1.5% of total lymphocytes) primed CD8+ T cells were present in the blood of separate recipient mice 2 days after adoptive transfer. For virological studies, recipient mice were sacrificed on day 10 after initial infection, and tissues were analyzed for viral burden by plaque assay.

Addition of CD8+ T cells to WNV-infected neurons.

Incubation of purified CD8+ T cells with WNV-infected neurons was performed as described previously (37). Cortical neurons were infected at an MOI of 0.001. One hour later, unbound virus was removed with four washes of warm medium. Subsequently, purified naïve or WNV-primed CD8+ T cells from wild-type or TRAIL−/− mice were added at an effector-to-target (E:T) ratio of 50:1. Supernatants were harvested 24 and 48 h after infection, and WNV production was measured by viral plaque assay. In some experiments, recombinant TRAIL (10 μg/ml), neutralizing anti-TRAIL antibody, or an isotype control rat IgG2a antibody (BioLegend) was added at the same time as the CD8+ T cells.

TRAIL, DR5, FasL, and granzyme B staining.

Brains were harvested from wild-type or TRAIL−/− mice on day 8 after infection. After isolation of leukocytes, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were stained for expression of TRAIL by use of a biotin-labeled anti-mouse CD253 (TRAIL) antibody (eBioscience), for expression of FasL by use of an anti-mouse CD95L antibody (Biolegend), and for expression of intracellular granzyme B by use of an anti-mouse granzyme B antibody (Invitrogen) for 30 min at 4°C. Data collection and analysis were performed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Cortical neurons were isolated as described previously (37) and infected with WNV (MOI of 0.001) for 1 h. One day later, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS at 4°C for 10 min. After several washes in PBS and blocking in 5% normal goat serum, neurons were stained with rabbit anti-mouse DR5 (10 μg/ml anti-TRAIL-R2; Millipore) for 1 h at room temperature. After rinsing in PBS supplemented with 0.05% Triton X-100, cells were also stained with WNV-immune rat serum (1:100 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. Fluorescence was detected after incubation with Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes)- and Cy3 (Jackson Laboratories)-conjugated secondary antibodies for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were visualized after counterstaining with ToPro3 (Molecular Probes), using a Zeiss 510 Meta LSM confocal microscope.

Data analysis.

All data were analyzed statistically using Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed by the log rank test. Differences in viral burdens in mice were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney test. Differences in viral infection in primary cell cultures and in numbers of T cells were analyzed by an unpaired t test.

RESULTS

TRAIL is required to protect mice from lethal WNV infection.

Previous in vitro studies suggested that addition of high doses (e.g., 5 to 20 μg/ml) of exogenous recombinant human TRAIL to cell cultures could inhibit infection with DENV, a related flavivirus (40). To assess directly the role of TRAIL in the context of WNV infection in vivo, we compared the survival rates of 8- to 9-week-old wild-type and congenic TRAIL−/− mice after subcutaneous infection with 102 PFU of a North American WNV isolate (New York, 2000). By day 8 after infection, all wild-type and deficient mice showed clinical signs of infection, including reduced activity, weight loss, and hair ruffling. However, survival rates of the TRAIL−/− mice were markedly lower (17% compared to 75%; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1A). Similarly, we observed a significant decrease in the mean time to death (11.9 ± 0.3 versus 13.1 ± 0.5 days; P < 0.04) in TRAIL−/− compared to wild-type mice. Thus, an absence of TRAIL results in a more severe phenotype after WNV infection, with a poorer clinical outcome.

Fig 1.

Survival and viral titer analysis of wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice infected with WNV. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Wild-type (n = 40) and TRAIL−/− (n = 29) mice were infected via the subcutaneous route with 102 PFU of WNV and monitored for mortality for 28 days. Survival differences were judged by the log rank test and were statistically significant (P < 0.0001). (B to E) Viremia and WNV tissue burdens in wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice. Infectious WNV levels in sera (B), spleens (C), brains (D), and spinal cords (E) of wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice were measured by viral plaque assay of samples harvested at the indicated time points. Data are expressed as log10 PFU per gram of tissue or ml of serum and reflect results for 8 to 13 mice per time point between days 2 and 10. For viral burden experiments, the horizontal bars represent the mean titers, the dotted lines represent the limits of sensitivity of viral detection, and asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice, determined by the Mann-Whitney test.

A deficiency of TRAIL results in enhanced WNV tissue burden, primarily in the central nervous system.

To begin to understand how an absence of TRAIL conferred increased susceptibility to WNV infection, we measured the levels of infectious virus in tissues. Wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice were infected by the subcutaneous route, and viral loads were analyzed on days 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 after infection.

(i) Peripheral tissues.

We observed no significant difference (P ≥ 0.3) in the kinetics and magnitude of WNV infection in serum or the spleen between wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice throughout the time course (Fig. 1B and C). Moreover, no infectious virus was detected in the liver in either wild-type or TRAIL−/− mice (data not shown). In comparison, infectious WNV was recovered from the kidney (3 of 10 mice) on day 4 for a subset of TRAIL−/− but not wild-type mice (data not shown). The kidney usually does not support WNV infection in wild-type C57BL/6 mice, whereas replication can be observed in congenic mice lacking aspects of cell intrinsic immunity (e.g., IFN-αβR−/−, IRF-7−/−, or IRF-3−/− mice [5, 6, 28]). Overall, TRAIL appears to have a limited role in controlling WNV infection in peripheral organs.

(ii) CNS tissues.

In the brain and spinal cord, similar levels of WNV (104 to 105 PFU/g) were detected in wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice through day 8 after infection. However, by day 10, significantly higher levels were measured in the brains (104.8 versus 103.5 PFU/g; P = 0.01) and spinal cords (104.9 versus 103.6 PFU/g; P = 0.01) of TRAIL−/− mice (Fig. 1D and 1E). These experiments suggest that TRAIL functions primarily to control WNV in CNS tissues.

TRAIL signaling does not directly control WNV replication in the CNS.

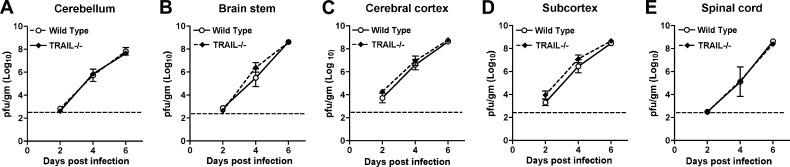

Based on the viral burden data obtained after subcutaneous infection, we hypothesized that a lack of TRAIL signaling in resident cells of the CNS might contribute to higher WNV titers in the brain through direct inhibitory effects on neuronal infection. To test this, wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice were infected with 101 PFU of WNV directly into the cerebral cortex via an intracranial route and monitored for local replication and dissemination. Viral burdens in the cerebral cortex, subcortical white matter, brain stem, cerebellum, and spinal cord were measured on days 2, 4, and 6 after infection (Fig. 2A to E). Somewhat surprisingly, no differences in viral burdens in the different CNS regions of wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice (P > 0.2) were observed at any time point. Similarly, we observed no difference in relative morbidity between wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice after intracranial WNV infection. These results suggest that TRAIL signaling within the CNS by resident cells does not directly control WNV infection.

Fig 2.

WNV burden in the CNS after intracranial infection. Wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice were infected with 101 PFU of WNV via the intracranial route. Different regions of the brain were harvested at the indicated time points. (A) Cerebellum; (B) brain stem; (C) cerebral cortex; (D) subcortex; (E) spinal cord. Tissue homogenates were analyzed for viral burden by plaque assay. Data are shown as PFU per gram of tissue for 5 to 8 mice per time point. The dotted line represents the limit of detection. None of the differences achieved statistical significance.

Adaptive immune responses in TRAIL−/− mice.

Since we observed elevated viral burdens in CNS tissues after subcutaneous but not intracranial infection, we speculated that TRAIL might modulate adaptive immune functions (B or T cells), which are required for efficient clearance of WNV from the brain (8, 17, 35, 39). To assess this, we measured the magnitude of the adaptive immune response to WNV infection at different time points after infection.

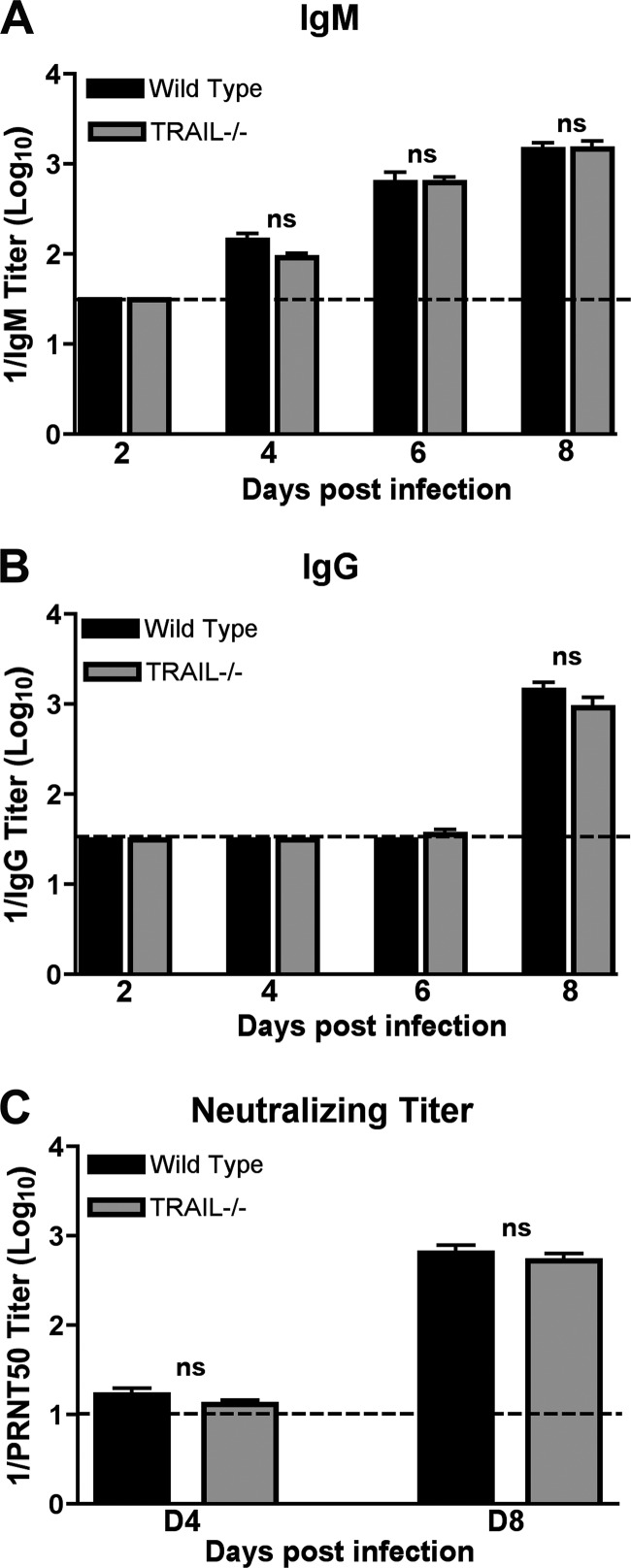

(i) Antibody response.

The kinetics and magnitude of anti-WNV IgM and IgG responses were virtually identical in wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice (P > 0.9) (Fig. 3A and B). Similarly, there was no difference in neutralizing titer for wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice at days 4 and 8 after infection (P > 0.4) (Fig. 3C). Thus, TRAIL is not required for the development of WNV-specific antibodies, and increased viral burdens in the brain and spinal cord were not due to an obvious defect in antibody production.

Fig 3.

WNV-specific antibody responses in wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice. Wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice were infected with WNV via the subcutaneous route, and serum was collected at the indicated time points. The development of WNV-specific IgM (A) or IgG (B) was determined by ELISA using purified WNV E protein. Data are averages for 5 mice at day 2 and 10 mice each at days 4 through 8. (C) Neutralizing antibody response. Neutralizing titers were determined by a PRNT assay. All samples were serially diluted in duplicate, and data are expressed as the reciprocal PRNT50, the antibody titer that reduced the plaque number by 50%. Data are averages for 10 mice per time point. ns, none of the differences achieved statistical significance.

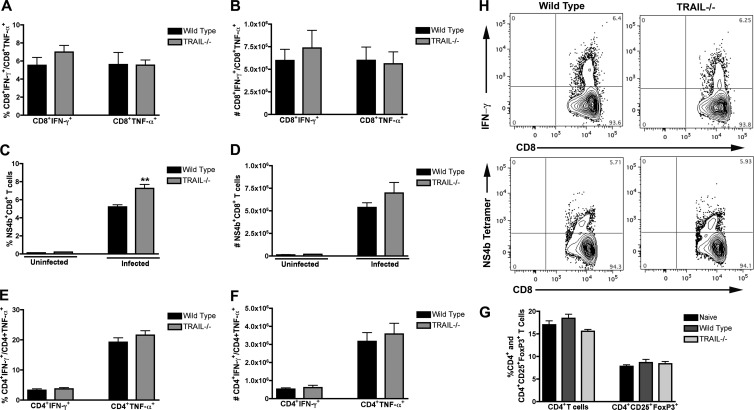

(ii) T cell response.

To evaluate a possible role of TRAIL in priming of WNV-specific T cells in the periphery, splenocytes from wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice were harvested at day 7 after infection and restimulated ex vivo with an immunodominant Db-restricted NS4B peptide or anti-CD3 antibody, and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were analyzed for the production of intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α by flow cytometry. We observed no significant differences (P > 0.2) in the percentages of IFN-γ+ or TNF-α+ CD8+ T cells from wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice after incubation with WNV-specific peptide (Fig. 4A and B). We did, however, detect a slight increase in the percentage (7% versus 5%; P < 0.002) but not number (P > 0.2) of NS4B tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells in TRAIL−/− mice (Fig. 4C and D). In contrast, no difference in the percentages or absolute numbers of CD4+ T cells producing IFN-γ and TNF-α was observed between wild-type mice and TRAIL−/− mice (P > 0.4) (Fig. 4E and F). Finally, we also did not observe a difference (P > 0.1) in the percentage or number of CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in WNV-infected wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice (Fig. 4G and data not shown). Overall, these experiments demonstrate that an absence of TRAIL does not affect induction of adaptive B and T cell responses after WNV infection.

Fig 4.

T cell responses in the spleens of wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice after WNV infection. (A to D) CD8+ T cells. WNV-infected splenocytes from wild-type or TRAIL−/− mice were harvested at day 7 and stimulated ex vivo for 6 h (A and B) with an immunodominant Db-restricted NS4B peptide. Cells were costained for CD8 and intracellular IFN-γ or TNF-α and processed by flow cytometry. Data are presented as percentages (A) or total numbers (B) of positive cells. The percentages (C) and total numbers (D) of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in uninfected or WNV-infected wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice were determined by binding to a Db-restricted NS4B tetramer. Asterisks indicate statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences between wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice. (E and F) CD4+ T cells. WNV-infected splenocytes from wild-type or TRAIL−/− mice were harvested at day 7 and stimulated ex vivo for 6 h with a stimulatory anti-CD3 antibody. Cells were costained for CD4 and intracellular IFN-γ or TNF-α and processed by flow cytometry. Data are presented as percentages (E) or total numbers (F) of positive cells. Data in panels A to F are representative for 6 to 10 mice from three independent experiments. In panels A, C, and E, the percentages of IFN-γ-, TNF-α-, and NS4B tetramer-positive cells represent the fractions of total gated CD8+ or CD4+ T cells. (G) Regulatory T cells. Splenocytes from WNV-infected wild-type (naïve or infected) and TRAIL−/− mice were harvested at day 7 and stained with antibodies to CD4, CD25, and FoxP3. Data are expressed as percentages of CD4+ T cells that stained positive for CD25 and FoxP3. Data were pooled for 6 mice from 2 independent experiments. (H) Flow cytometry profiles. Representative flow cytometry profiles of intracellular IFN-γ staining (upper panels) and NS4B tetramer staining (bottom panels) are shown for splenic CD8+ T cells from wild-type or TRAIL−/− mice at day 7 after WNV infection.

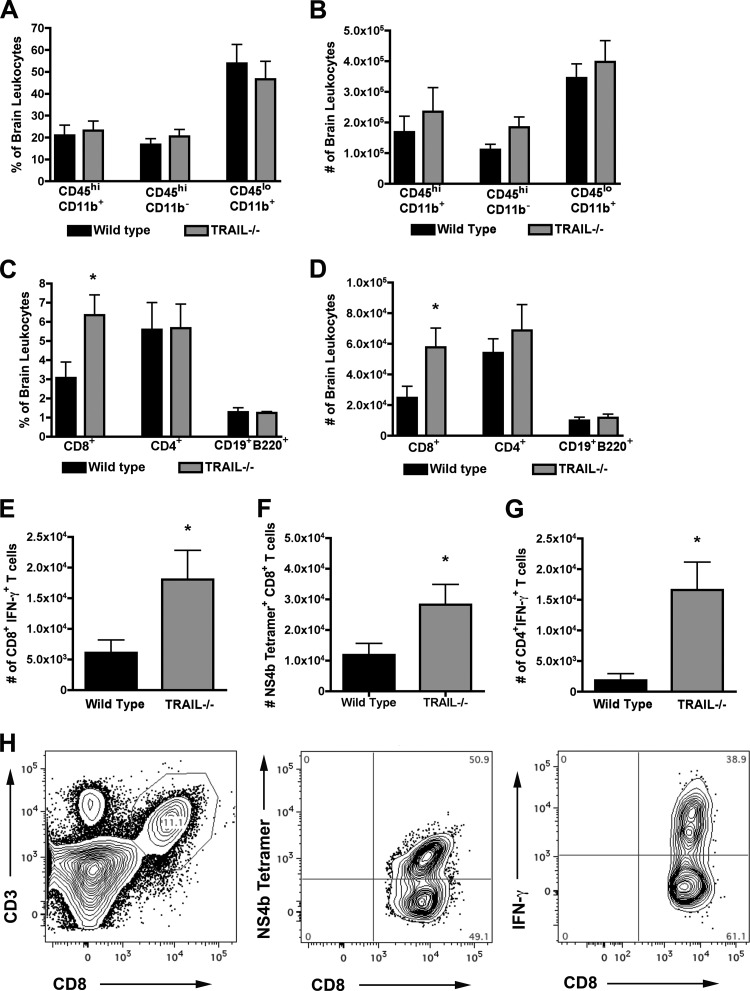

Trafficking of leukocytes to the brain is not impaired in TRAIL−/− mice.

Although peripheral T cell responses were unchanged in TRAIL−/− mice after WNV infection, we assessed whether the enhanced viral replication in the CNS of TRAIL−/− mice might be related to blunted activation of resident microglia or migration of protective macrophages and CD8+ T cells. To assess this, leukocytes were isolated from brains of wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice by gradient centrifugation on day 8 after infection and then were analyzed by flow cytometry. Notably, we failed to observe a difference in the percentage or number of activated CD11b+ CD45lo microglia or macrophages (CD11b+ CD45hi) (P > 0.4) (Fig. 5A and B). We did, however, find a higher percentage and larger number (P < 0.03) (Fig. 5C and D) of total CD8+ T cells in the brains of TRAIL−/− mice. This correlated with increased numbers of CD8+ T cells from TRAIL−/− mice that expressed IFN-γ (P < 0.04) (Fig. 5E) after WNV-specific peptide restimulation ex vivo or that stained directly with NS4B tetramers (P = 0.05) (Fig. 5F). For comparison, while similar percentages and numbers (P > 0.4) of CD4+ T cells and CD19+ B220+ B cells were observed, we measured larger numbers of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells after ex vivo restimulation from TRAIL−/− mice than from wild-type mice (P < 0.04) (Fig. 5G). Overall, these data show no clear deficiency in recruitment or activation of leukocytes in the brains of WNV-infected TRAIL−/− mice; in general, the higher levels of T cells observed were likely secondary to the increased viral burden.

Fig 5.

Accumulation of leukocytes in the CNS of WNV-infected wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice. Wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice were infected with 102 PFU of WNV by the subcutaneous route. Eight days later, brains were harvested and leukocytes were isolated by Percoll gradient centrifugation. (A and B) Percentages (A) and total numbers (B) of microglia (CD11b+ CD45lo) and macrophages (CD11b+ CD45hi). (C and D) Percentages (C) and total numbers (D) of CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD19+ B220+ B cells. (E and F) Number of WNV-specific CD8+ T cells in the brain as judged by NS4B peptide restimulation and intracellular IFN-γ staining (E) or NS4B tetramer staining (F). (G) Number of activated CD4+ T cells in the brain as judged after incubation with a stimulatory anti-CD3 antibody and intracellular IFN-γ staining. Data represent the averages for two independent experiments with 6 mice per group. Asterisks indicate statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences between wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice. (H) Representative flow cytometry profiles of CD3+ CD8+ T cells in the brains of TRAIL−/− mice (left) 8 days after WNV infection. Surface NS4B tetramer staining (middle) and intracellular IFN-γ staining after NS4B peptide restimulation ex vivo (right) are shown for brain CD8+ T cells.

Adoptive transfer of wild-type and TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells.

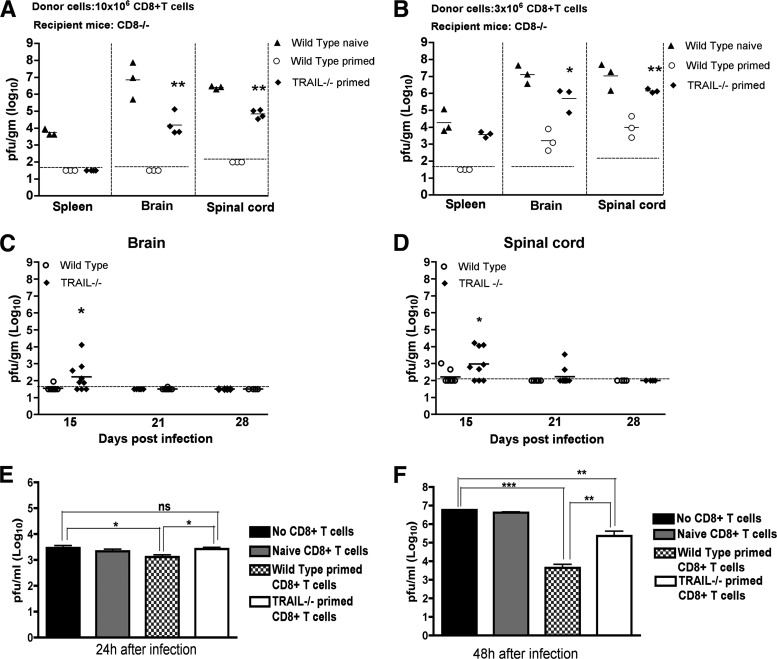

In addition to Fas-Fas ligand or perforin/granzyme cytolysis mechanisms, CD8+ T cells and NK cells can secrete TRAIL to lyse target cells (1, 3, 41). Since an absence of CD8+ T cells or their specific effector functions resulted in a failure to control WNV replication in the brain and spinal cord (34, 35, 37, 39), we hypothesized that a deficiency of TRAIL in CD8+ T cells could explain the enhanced viral replication in the CNS of TRAIL−/− mice. To evaluate this, we performed adoptive transfer studies. Primed CD8+ T cells were purified from the spleens of WNV-infected wild-type or TRAIL−/− mice on day 7 by positive selection using antibody-coated magnetic beads. We adoptively transferred 10 × 106 CD8+ T cells into congenic CD8−/− mice 1 day after WNV infection. Nine days later, we assessed the viral burdens in spleen and CNS tissues of recipient CD8−/− mice. Adoptive transfer of 10 × 106 naïve wild-type CD8+ T cells failed to control infection, as high levels of WNV were apparent in the spleens and CNS of recipient CD8−/− mice (Fig. 6A). Transfer of 10 × 106 WNV-primed wild-type CD8+ T cells, however, efficiently controlled infection, as no virus was detected in the target tissues. In contrast, while adoptive transfer of primed TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells cleared virus from the spleen, the cells failed to control WNV in the CNS, as recipient mice (4 of 4 mice) sustained infection (∼104 to 105 PFU/g). The viral burden in the CNS of CD8−/− mice receiving TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells was nonetheless lower than that in the CNS of mice receiving naïve wild-type cells (104.2 PFU/g versus 106.9 PFU/g; P = 0.01), confirming the existence of TRAIL-independent clearance mechanisms in CD8+ T cells.

Fig 6.

Role of TRAIL in CD8+ T cell-mediated control of WNV infection in the brain. (A and B) Viral yields in different tissues after adoptive transfer of WNV-primed CD8+ T cells. Donor CD8+ T cells (10 × 106 [A] or 3 × 106 [B]) were purified from naïve or WNV-primed wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice and transferred into recipient CD8−/− mice 1 day after infection. The spleens, brains, and spinal cords of recipient CD8−/− mice were harvested on day 10 after initial infection, and WNV was titrated by plaque assay. Data represent results from 3 or 4 mice in two independent experiments. The dotted lines represent the limits of sensitivity of the assay. (C and D) WNV persistence in CNS tissues. Wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice were infected with WNV, brains (C) and spinal cords (D) were harvested on days 15, 21, and 28 after infection, and viral yields were titrated by plaque assay. Results are for 4 to 9 mice per time point. (E and F) Control of WNV infection in primary neurons ex vivo after addition of primed CD8+ T cells. Cortical neurons were infected with WNV at an MOI of 0.001. After 1 h, purified naïve or WNV-primed CD8+ T cells from wild-type or TRAIL−/− mice were added at an E:T ratio of 50:1. After 24 h (E) or 48 h (F), supernatants were harvested and WNV production was measured by plaque assay. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005; and ***, P < 0.0001). ns, no significant difference.

To corroborate the role of TRAIL in CD8+ T cell-mediated clearance of WNV from the CNS, a smaller number (3 × 106) of primed CD8+ T cells was adoptively transferred (Fig. 6B). Nine days after transfer, WNV was not detected (<101.8 PFU/g) in the spleens of recipient CD8−/− mice that had received primed wild-type cells; however, infectious WNV was recovered from mice receiving primed TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells (∼103.4 PFU/g). Higher levels of WNV were also recovered from the CNS of CD8−/− mice receiving 3 × 106 primed CD8+ T cells from TRAIL−/− mice than from those of mice receiving primed CD8+ T cells from wild-type mice (103.6 versus 106.1 PFU/g; P < 0.02). Consistent with these findings, adoptive transfer of 3 × 106 WNV-primed, but not naïve, CD8+ T cells into recipient TRAIL−/− mice resulted in an improved survival rate (71% versus 20%; P = 0.05). Overall, the adoptive transfer experiments demonstrate that a deficiency of TRAIL in CD8+ T cells negatively impacts control of WNV in mice.

Delayed WNV clearance in the CNS of TRAIL−/− mice.

Given our adoptive transfer study results, we hypothesized that TRAIL is required in the CNS for efficient clearance by CD8+ T cells. Because prior studies showed that a deficiency of CD8+ T cell effector molecules (e.g., perforin or Fas ligand) caused WNV persistence in the CNS for several weeks (34, 37), we evaluated the impact of a TRAIL deficiency on the kinetics of viral clearance in the brain and spinal cord. Infectious virus was measured in the few surviving wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice on days 15, 21, and 28 after inoculation (Fig. 6C and D). Low levels (102 to 103 PFU/g) of infectious WNV were detected on day 15 in 12.5% (1 of 8 mice) and 25% (2 of 8 mice) of brains and spinal cords, respectively, of wild-type mice. No infectious virus was recovered from the CNS at 21 days or after in wild-type mice. In contrast, higher levels of WNV (102 to 106 PFU/g) were detected in the CNS (6 of 9 mice [67%]; P < 0.005) of TRAIL−/− mice on day 15. Moreover, on day 21, ∼10% (1 of 10 mice) and 20% (2 of 10 mice) of TRAIL−/− mice had detectable yet low levels (102 to 103 PFU/g) of infectious virus in the brain and spinal cord, respectively. By day 28, no infectious virus was recovered from the CNS of any TRAIL−/− mice. Thus, in the surviving mice, an absence of TRAIL resulted in somewhat delayed clearance of infectious WNV from the brain and spinal cord.

TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells are impaired in the ability to clear WNV from infected neurons.

To demonstrate directly that CD8+ T cells require TRAIL to control WNV infection of neurons, we used a viral clearance assay with primary cortical neurons (37). One hour after infection, bulk WNV-primed wild-type or TRAIL−/− splenic CD8+ T cells were added to neurons at an effector-to-target ratio of 50:1. At 24 and 48 h, the levels of infectious virus in the supernatants of neuronal cultures were titrated by plaque assay. As seen previously (34), we observed reduced (2 to ∼1,300-fold; P < 0.03) viral yields in supernatants from neurons incubated with wild-type primed compared to naïve or no CD8+ T cells at 24 and 48 h (Fig. 6E and F). In comparison, WNV-primed TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells restricted infection in neurons less efficiently, with no difference at 24 h (P > 0.7) and a smaller reduction (23-fold; P < 0.02) at 48 h. These experiments suggest that WNV-primed CD8+ T cells control neuronal infection in part through TRAIL-dependent mechanisms.

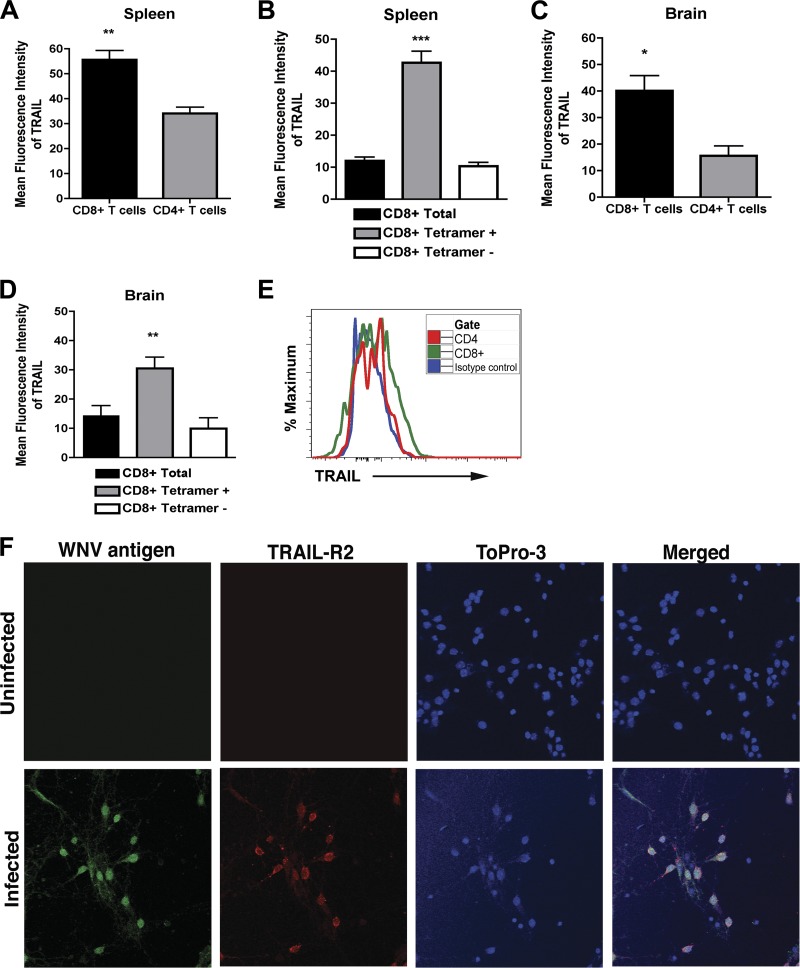

As additional confirmation, we assessed the surface expression of TRAIL on WNV-primed CD8+ T cells in the spleen and the brain. Wild-type mice were infected with 102 PFU by subcutaneous inoculation, and on day 8, splenocytes and brain leukocytes were harvested and stained with anti-TRAIL antibody. In the spleen, TRAIL was expressed at higher levels on CD8+ T cells than on CD4+ T cells (mean fluorescence intensity of 56 ± 4 for CD8+ T cells and 34 ± 2 for CD4+ T cells; P < 0.006) (Fig. 7A). Among total CD8+ T cells, higher levels (P < 0.0001) of TRAIL were measured on NS4B tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells (Fig. 7B). Analogous to data obtained from the spleen, higher levels of TRAIL were detected on CD8+ T cells isolated from the brain than on CD4+ T cells (mean fluorescence intensity of 40 ± 6 for CD8+ T cells and 16 ± 4 for CD4+ T cells; P < 0.02) (Fig. 7C and E), and more surface expression of TRAIL was measured on NS4B tetramer-positive than tetramer-negative CD8+ T cells (Fig. 7D). These data confirm that WNV-specific CD8+ T cells express TRAIL in leukocytes isolated from the spleen and the brain after WNV infection. Given that CD8+ T cells in the brain expressed TRAIL, we assessed whether WNV-infected neurons expressed its cognate ligand, DR5. In the absence of infection, cortical neurons showed no apparent DR5 expression (Fig. 7F, top panels). However, within 24 h, WNV infection resulted in efficient surface expression of DR5 (Fig. 7F, bottom panels). Thus, WNV infection rapidly induces DR5 expression on neurons, which could sensitize them to the inhibitory effects of TRAIL.

Fig 7.

CD8+ T cells express TRAIL. Splenocytes and brain leukocytes from WNV-infected wild-type mice were harvested at day 7 and stained for surface expression of TRAIL on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Data were analyzed by flow cytometry and are expressed as mean fluorescence intensities for the positive cells only. (A) TRAIL expression on total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the spleen. (B) TRAIL expression on NS4B tetramer-positive and tetramer-negative CD8+ T cells in the spleen. (C) TRAIL expression on total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the brain. (D) TRAIL expression on NS4B tetramer-positive and tetramer-negative CD8+ T cells in the brain. Data were pooled from four mice, and asterisks indicate differences that are statistically significant. (E) Representative flow cytometry profiles after staining with anti-TRAIL antibody on the surfaces of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the brains of mice infected with WNV. (F) DR5 expression on neurons. Neurons were left uninfected or infected with WNV (MOI of 0.001) for 24 h. Cells were harvested and stained for surface DR5 and intracellular WNV antigen, counterstained with ToPro3, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Representative data from multiple images are shown.

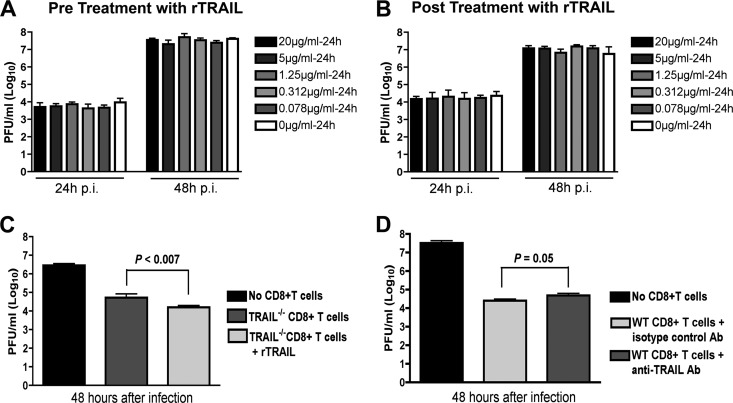

CD8+ T cells require TRAIL to optimally control WNV infection in neurons.

Our CD8+ T cell adoptive transfer and coincubation experiments with neurons strongly suggested an inhibitory effect of TRAIL on viral replication in neurons. However, they did not provide direct insight into the mechanism. We speculated that TRAIL might have a direct antiviral effect, as seen previously with the related flavivirus DENV (40). To address this possibility, we added increasing concentrations of recombinant TRAIL (0.078 to 20 μg/ml) 1 day prior to WNV infection (MOI of 0.001) of primary cortical neurons in the absence of CD8+ T cells. Supernatants were collected from neurons 24 and 48 h after infection, and virus burdens were analyzed by plaque assay. Notably, we observed no reduction in WNV yield with any dose of TRAIL added prior to infection (Fig. 8A). Even when experiments were repeated with addition of recombinant TRAIL immediately after infection, no direct antiviral effect of TRAIL was observed (Fig. 8B). Given these results, we suspected that the antiviral effect of TRAIL on WNV-infected neurons needed to occur in the context of CD8+ T cell-mediated clearance. Indeed, the addition of recombinant TRAIL to primed TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells reduced WNV infection in cortical neurons (Fig. 8C) (2.5-fold difference for cells with no TRAIL versus those with TRAIL; P < 0.007). Reciprocally, addition of a neutralizing anti-TRAIL antibody to wild-type primed CD8+ T cells also resulted in increased WNV infection of neurons (Fig. 8D) (3.2-fold difference for isotype control versus anti-TRAIL antibody; P = 0.05). Thus, TRAIL provides an antiviral signal to neurons, but only when CD8+ T cells are present.

Fig 8.

Mechanism by which TRAIL inhibits WNV infection in neurons. (A) Recombinant TRAIL does not have a direct antiviral effect on cortical neurons. Primary cortical neurons were treated with increasing doses (0.078 to 20 μg/ml) of recombinant TRAIL (rTRAIL) for 24 h prior to infection with WNV (MOI of 0.001). One hour later, free virus and TRAIL were removed by washing. Supernatants were harvested 24 and 48 h after infection and titrated by plaque assay. Results are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. (B) Postexposure addition of recombinant TRAIL does not confer an antiviral effect against WNV infection of cortical neurons. Neurons were infected with WNV (MOI of 0.001). One hour later, free virus was removed by extensive washing. Subsequently, increasing doses (0.078 to 20 μg/ml) of recombinant TRAIL were added, and supernatants were harvested 24 h later and titrated by plaque assay. Results are representative of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. None of the doses of recombinant TRAIL conferred a statistically significant antiviral effect. (C) Addition of recombinant TRAIL enhances the antiviral effect of primed TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells. Cortical neurons were infected with WNV at an MOI of 0.001. After 1 h, purified WNV-primed CD8+ T cells from TRAIL−/− mice were added at an E:T ratio of 50:1. At the same time, recombinant TRAIL (10 μg/ml) was added to some of the cell cultures. Supernatants were harvested 48 h later, and WNV production was measured by plaque assay. (D) Addition of neutralizing anti-TRAIL antibody decreases the antiviral effect of primed wild-type CD8+ T cells. Cortical neurons were infected with WNV at an MOI of 0.001. After 1 h, purified WNV-primed CD8+ T cells from wild-type mice were added at an E:T ratio of 50:1. At the same time, a neutralizing anti-TRAIL or isotype control antibody (10 μg/ml) was added to cells. Supernatants were harvested 48 h later, and WNV production was measured by plaque assay. Data in panels C and D were pooled from six replicate samples generated from independent experiments.

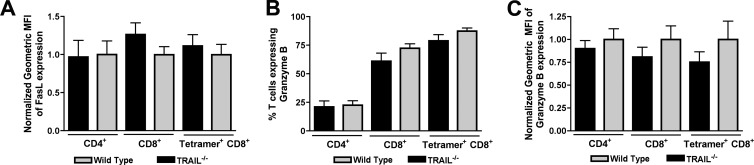

Because of the modest effects of exogenous TRAIL and anti-TRAIL antibodies on CD8+ T cell-mediated clearance of WNV infection in neurons, we speculated that TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells might have additional defects in their effector functions. Since prior studies had already established protective effects of cytolytic granules (perforin/granzyme) and cell death (FasL) pathways in T cell protection against WNV (34, 37), we assessed their relative expression in wild-type and TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells in the brain. Relative FasL expression was unchanged on the surfaces of TRAIL−/− CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the brain (P ≥ 0.2) (Fig. 9A). This result was also observed on WNV-specific NS4B tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells. Similarly, in the brain, granzyme B was expressed at similar levels (P > 0.2) in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and NS4B tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells (Fig. 9B and C). Thus, the functional defect of TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells in the context of clearance of WNV infection in the brain is not due to impaired expression of proteins associated with alternate cytolytic mechanisms.

Fig 9.

FasL and granzyme B expression on CD8+ T cells from the brains of WNV-infected wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice. Brain leukocytes from WNV-infected wild-type mice were harvested at day 8 and stained for surface expression of FasL and intracellular expression of granzyme B. Data were analyzed by flow cytometry, and all results are pooled data from two independent experiments. (A) FasL expression on total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and on NS4B tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells in the brain. Note that 100% of brain T cells expressed FasL on the surface. Data are expressed as normalized mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) of FasL-positive cells. (B and C) Granzyme B expression on total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and on NS4B tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells in the brain. Data are expressed as percentages of granzyme B-positive cells (B) and normalized mean fluorescence intensities of the granzyme B-positive cells (C). Data were pooled from nine mice, and none of the differences were statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

TRAIL has been implicated in the control of viral infections by several different mechanisms, including cytotoxic and direct antiviral effects. We initiated this study because primary human cell culture experiments showed that TRAIL was induced after DENV infection and that treatment of human myeloid cells with exogenous, recombinant TRAIL inhibited DENV infection through an apoptosis-independent mechanism (40). To address the physiological function of TRAIL in vivo in the context of infection by a flavivirus, we assessed WNV pathogenesis in wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice. Mice lacking TRAIL showed relatively normal levels of WNV infection in peripheral tissues but sustained elevated viral titers in the brain and spinal cord that were associated with delayed clearance and increased mortality compared to those of wild-type mice. No difference in WNV infection was observed in the brain and spinal cord after direct intracranial inoculation. While priming of adaptive B and T cell responses in the periphery and trafficking of immune and antigen-specific cells to the brain were normal in TRAIL−/− mice, CD8+ T cells showed qualitative defects in the ability to clear WNV infection. Adoptive transfer studies suggested that the increased susceptibility associated with TRAIL deficiency was due to defects in CD8+ T cell clearance mechanisms. Indeed, primed TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells controlled WNV infection less efficiently in primary neuronal cultures ex vivo.

Our experiments suggest that CD8+ T cells utilize TRAIL to control WNV pathogenesis and infection of neurons in the CNS. This conclusion is based on several experimental observations, including (i) increased viral burdens in the brain and spinal cord at day 10 but not day 6 or 8 after infection of TRAIL−/− mice, (ii) delayed clearance of WNV infection in the few surviving TRAIL−/− mice, (iii) less efficient clearance of infection in CD8−/− mice after adoptive transfer of WNV-primed TRAIL−/− compared to wild-type CD8+ T cells, and (iv) less efficient control of WNV infection in neurons ex vivo by primed TRAIL−/− compared to wild-type CD8+ T cells. This phenotype was not due to TRAIL-dependent effects on CD8+ T cell priming or trafficking, as equivalent percentages and numbers of polyfunctional antigen-specific CD8+ T cells were detected in WNV-infected TRAIL−/− and wild-type mice. Our results are consistent with recent studies with influenza virus which showed that a deficiency of TRAIL enhanced morbidity and viral replication through qualitatively decreased influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses in the lung (3).

Prior studies have shown that CD8+ T cells also utilize perforin and Fas ligand to clear WNV from infected neurons (34, 37). Analogous to our current studies with TRAIL−/− mice, perforin- and Fas ligand-deficient (gld) mice had elevated viral titers in the brain and spinal cord, resulting in increased mortality compared to that of wild-type mice, and in the few mice that survived infection, persistent WNV infection was detected for several weeks. However, there appears to be a functional hierarchy, as a deficiency of perforin or Fas ligand resulted in less efficient clearance of WNV infection in the spleen, whereas this phenotype was absent in TRAIL−/− mice. Thus, while CD8+ T cells utilize multiple effector molecules to clear WNV from neurons in the CNS, the viral burden and survival phenotypes in TRAIL−/− mice are subordinate compared to those observed previously in perforin−/− and gld mice.

Prior cell culture studies with DENV and HIV suggested that an antiviral effect of exogenous treatment of TRAIL occurs in the absence of apoptosis (33, 40). Although an analogous effect of recombinant TRAIL on WNV infection in cultured primary neurons was not observed, an inhibitory effect was seen in the context of a protective CD8+ T cell response. The lack of a direct antiviral effect of exogenous TRAIL against WNV is consistent with some of our in vivo results: (i) we observed no difference in viral burden in peripheral tissues after subcutaneous infection, and (ii) we failed to detect differences in viral replication in multiple CNS regions after direct intracranial inoculation of wild-type and TRAIL−/− mice. However, TRAIL did show an antiviral effect in the context of CD8+ T cell-mediated clearance of WNV infection in neurons. This observation was most apparent in reconstitution experiments showing that the addition of exogenous TRAIL to TRAIL−/− CD8+ T cells enhanced the antiviral effect against WNV in neurons. What is the precise mechanism by which TRAIL facilitates optimal CD8+ T cell-mediated control of WNV infection in neurons? While studies with transformed cells in culture showed that exogenous TRAIL sensitized respiratory syncytial virus- or human cytomegalovirus-infected cells to apoptosis (16, 31), an absence of TRAIL did not specifically affect cell death as judged by terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) of neurons in the brain or in culture (B. Shrestha and M. Diamond, unpublished data). Although further signaling analysis is warranted, our data are more consistent with a model in which TRAIL produced by CD8+ T cells provides a direct antiviral signal to neurons. Why did recombinant TRAIL alone fail to inhibit WNV infection directly in culture? We speculate that TRAIL derived by WNV-specific CD8+ T cells is necessary but not sufficient to confer the inhibitory effect and requires additional signals through other cytolytic pathways (e.g., Fas ligand-Fas or perforin/granzyme) to achieve an optimal inhibitory effect. Alternatively, activated WNV-specific effector CD8+ T cells secrete other cytokines (e.g., IFN-γ or TNF-α) which modulate expression of TRAIL ligands (e.g., DR4 and DR5) or signaling components in neurons to levels that are sufficient for functional consequences. WNV infection alone can induce DR5 expression on neuronal targets in culture and in vivo.

In summary, our study demonstrates that CD8+ T cells require TRAIL to optimally restrict WNV infection in the brain and spinal cord. Thus, CD8+ T cells utilize at least three separate effector mechanisms (TRAIL, Fas ligand, and perforin/granzyme) to control WNV infection and injury of neurons. For highly neurovirulent viruses (e.g., the New York strain of WNV), clearance mechanisms by effector CD8+ T cells appear to limit dissemination and disease and outweigh the possible pathological effects of immune-targeted neuronal injury. A more complete understanding of the effector mechanisms responsible for clearance of WNV infection may inform novel vaccine strategies to optimize CD8+ T cell-mediated immunity against highly virulent viruses that target neurons in the CNS.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 June 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Beraza N, et al. 2009. Hepatocyte-specific NEMO deletion promotes NK/NKT cell- and TRAIL-dependent liver damage. J. Exp. Med. 206:1727–1737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brincks EL, et al. 2011. The magnitude of the T cell response to a clinically significant dose of influenza virus is regulated by TRAIL. J. Immunol. 187:4581–4588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brincks EL, Katewa A, Kucaba TA, Griffith TS, Legge KL. 2008. CD8 T cells utilize TRAIL to control influenza virus infection. J. Immunol. 181:4918–4925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Busch MP, et al. 2006. West Nile virus infections projected from blood donor screening data, United States, 2003. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:395–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Daffis S, Samuel MA, Keller BC, Gale M, Jr, Diamond MS. 2007. Cell-specific IRF-3 responses protect against West Nile virus infection by interferon-dependent and independent mechanisms. PLoS Pathog. 3:e106 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Daffis S, et al. 2008. Interferon regulatory factor IRF-7 induces the antiviral alpha interferon response and protects against lethal West Nile virus infection. J. Virol. 82:8465–8475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Diamond MS, Mehlhop E, Oliphant T, Samuel MA. 2009. The host immunologic response to West Nile encephalitis virus. Front. Biosci. 14:3024–3034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Diamond MS, Shrestha B, Marri A, Mahan D, Engle M. 2003. B cells and antibody play critical roles in the immediate defense of disseminated infection by West Nile encephalitis virus. J. Virol. 77:2578–2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diehl GE, et al. 2004. TRAIL-R as a negative regulator of innate immune cell responses. Immunity 21:877–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ebel GD, Carricaburu J, Young D, Bernard KA, Kramer LD. 2004. Genetic and phenotypic variation of West Nile virus in New York, 2002–2003. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 71:493–500 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Glass WG, et al. 2006. CCR5 deficiency increases risk of symptomatic West Nile virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 203:35–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoffmann O, et al. 2007. TRAIL limits excessive host immune responses in bacterial meningitis. J. Clin. Invest. 117:2004–2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hu WH, Johnson H, Shu HB. 1999. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptors signal NF-kappaB and JNK activation and apoptosis through distinct pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 274:30603–30610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Indraccolo S, et al. 2007. Identification of genes selectively regulated by IFNs in endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 178:1122–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ishikawa E, Nakazawa M, Yoshinari M, Minami M. 2005. Role of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in immune response to influenza virus infection in mice. J. Virol. 79:7658–7663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kotelkin A, Prikhod'ko EA, Cohen JI, Collins PL, Bukreyev A. 2003. Respiratory syncytial virus infection sensitizes cells to apoptosis mediated by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. J. Virol. 77:9156–9172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lanteri MC, et al. 2009. Tregs control the development of symptomatic West Nile virus infection in humans and mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119:3266–3277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lim JK, et al. 2008. Genetic deficiency of chemokine receptor CCR5 is a strong risk factor for symptomatic West Nile virus infection: a meta-analysis of 4 cohorts in the US epidemic. J. Infect. Dis. 197:262–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lim JK, et al. 2010. CCR5 deficiency is a risk factor for early clinical manifestations of West Nile virus infection but not for viral transmission. J. Infect. Dis. 201:178–185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin Y, et al. 2000. The death domain kinase RIP is essential for TRAIL (Apo2L)-induced activation of IkappaB kinase and c-Jun N-terminal kinase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6638–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mehlhop E, Diamond MS. 2006. Protective immune responses against West Nile virus are primed by distinct complement activation pathways. J. Exp. Med. 203:1371–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Merino D, et al. 2006. Differential inhibition of TRAIL-mediated DR5-DISC formation by decoy receptors 1 and 2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:7046–7055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Micheau O. 2003. Cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein: an attractive therapeutic target? Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 7:559–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Murray K, et al. 2006. Risk factors for encephalitis and death from West Nile virus infection. Epidemiol. Infect. 134:1325–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Petersen LR, Marfin AA, Gubler DJ. 2003. West Nile virus. JAMA 290:524–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rigaud S, et al. 2006. XIAP deficiency in humans causes an X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome. Nature 444:110–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Samuel MA, Diamond MS. 2006. Pathogenesis of West Nile virus infection: a balance between virulence, innate and adaptive immunity, and viral evasion. J. Virol. 80:9349–9360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Samuel MA, Diamond MS. 2005. Type I IFN protects against lethal West Nile virus infection by restricting cellular tropism and enhancing neuronal survival. J. Virol. 79:13350–13361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sato K, et al. 2001. Antiviral response by natural killer cells through TRAIL gene induction by IFN-alpha/beta. Eur. J. Immunol. 31:3138–3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Secchiero P, et al. 2005. TRAIL counteracts the proadhesive activity of inflammatory cytokines in endothelial cells by down-modulating CCL8 and CXCL10 chemokine expression and release. Blood 105:3413–3419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sedger LM, et al. 1999. IFN-gamma mediates a novel antiviral activity through dynamic modulation of TRAIL and TRAIL receptor expression. J. Immunol. 163:920–926 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sejvar JJ, et al. 2006. West Nile virus-associated flaccid paralysis outcome. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12:514–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Shepard BD, et al. 2008. Beneficial effect of TRAIL on HIV burden, without detectable immune consequences. PLoS One 3:e3096 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shrestha B, Diamond MS. 2007. Fas ligand interactions contribute to CD8+ T cell-mediated control of West Nile virus infection in the central nervous system. J. Virol. 81:11749–11757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shrestha B, Diamond MS. 2004. The role of CD8+ T cells in the control of West Nile virus infection. J. Virol. 78:8312–8321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shrestha B, Ng T, Chu HJ, Noll M, Diamond MS. 2008. The relative contribution of antibody and CD8+ T cells to vaccine immunity against West Nile encephalitis virus. Vaccine 26:2020–2033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shrestha B, Samuel MA, Diamond MS. 2006. CD8+ T cells require perforin to clear West Nile virus from infected neurons. J. Virol. 80:119–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shrestha B, Zhang B, Purtha WE, Klein RS, Diamond MS. 2008. Tumor necrosis factor alpha protects against lethal West Nile virus infection by promoting trafficking of mononuclear leukocytes into the central nervous system. J. Virol. 82:8956–8964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang Y, Lobigs M, Lee E, Mullbacher A. 2003. CD8+ T cells mediate recovery and immunopathology in West Nile virus encephalitis. J. Virol. 77:13323–13334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Warke RV, et al. 2008. TRAIL is a novel antiviral protein against dengue virus. J. Virol. 82:555–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zamai L, et al. 1998. Natural killer (NK) cell-mediated cytotoxicity: differential use of TRAIL and Fas ligand by immature and mature primary human NK cells. J. Exp. Med. 188:2375–2380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]