Abstract

The propensity of canine distemper virus (CDV) to spread to the central nervous system is one of the primary features of distemper. Therefore, we developed a reverse genetics system based on the neurovirulent Snyder Hill (SH) strain of CDV (CDVSH) and show that this virus rapidly circumvents the blood-brain and blood-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) barriers to spread into the subarachnoid space to induce dramatic viral meningoencephalitis. The use of recombinant CDVSH (rCDVSH) expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) or red fluorescent protein (dTomato) facilitated the sensitive pathological assessment of routes of virus spread in vivo. Infection of ferrets with these viruses led to the full spectrum of clinical signs typically associated with distemper in dogs during a rapid, fatal disease course of approximately 2 weeks. Comparison with the ferret-adapted CDV5804P and the prototypic wild-type CDVR252 showed that hematogenous infection of the choroid plexus is not a significant route of virus spread into the CSF. Instead, viral spread into the subarachnoid space in rCDVSH-infected animals was triggered by infection of vascular endothelial cells and the hematogenous spread of virus-infected leukocytes from meningeal blood vessels into the subarachnoid space. This resulted in widespread infection of cells of the pia and arachnoid mater of the leptomeninges over large areas of the cerebral hemispheres. The ability to sensitively assess the in vivo spread of a neurovirulent strain of CDV provides a novel model system to study the mechanisms of virus spread into the CSF and the pathogenesis of acute viral meningitis.

INTRODUCTION

Canine distemper virus (CDV) exhibits a number of unique properties compared to other members of the Morbillivirus genus, including its propensity to jump species barriers (4, 22) and its ability to spread to the central nervous system (CNS) in a high percentage of infected animals (8). However, different CDV strains display various levels of neurovirulence, induce neurological sequelae at a range of time points, and target different regions of the CNS (41). Infection of dogs with wild-type strains such as Ohio R252 (CDVR252) and A75/17 results in a long-term progressive and focal demyelinating encephalitis, while the neuroadapted Snyder Hill (SH) strain (CDVSH) produces a rapid, acute, and fatal encephalitis. The specific molecular determinants underlying these profound differences in the induction of either acute or long-term CNS infection remain unknown. While it has been reported that the hemagglutinin (H) glycoprotein of neurovirulent strains such as A75/17 is more efficient at mediating neuronal infection, disease duration appears to be the critical factor governing the capacity of different CDV strains to spread to the CNS (9).

CDVSH is a highly neurovirulent strain that was generated from 35 serial intracerebral passages of a natural CDV isolate in dogs (20). Infection of dogs with CDVSH leads to an acute disease with a rapidly progressive polioencephalitis that is fatal in 50% of infected animals (41). Ferrets are naturally susceptible to this strain when infected by the respiratory route. Neurological signs are observed in all infected animals, and they succumb to the disease from 14 to 17 days postinfection (d.p.i.) (39). Since members of the Mustelidae family are naturally susceptible to CDV, ferrets constitute a tractable small-animal model for the study of distemper which augments the dog models that have historically been used to study this disease (30, 42). The ferret model enables different CDV strains to be differentiated on the basis of their neurovirulence. For instance, CDV5804 induces a mild systemic disease with no spread to the CNS (44), while CDVSH spreads to the CNS within 2 weeks (35). In contrast, CDVA75/17 produces a slowly developing disease, with extensive virus spread in the brain observed at 4 to 5 weeks postinfection.

A number of possible routes of virus spread from the periphery to the CNS have been suggested, such as hematogenous spread of virus-infected lymphocytes across the blood-brain barrier and virus spread along olfactory nerves within infected neurons from the nasal concha (5, 34, 40). Virus spread across the blood-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) barrier is also suggested to play a role due to the observation of infected meningeal and ependymal cells early in the disease process (3). However, model systems amenable to the study of the rapid spread of CDV into the CSF, and hence the subarachnoid space, have not been reported thus far.

Recombinant (r) neurotropic viruses expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) have proven to be invaluable tools for tracing pathways of virus infection within the CNS (1, 19) and have enabled the rapid and sensitive identification of infected CNS regions. We have previously used recombinant measles viruses (rMV) expressing fluorescent proteins in conjunction with macroscopic and microscopic imaging techniques in murine and macaque models to detect virus-infected cells in tissues of living animals (15, 18, 26). In this study, we report the construction of a full-length cDNA clone of CDVSH and extend our previous use of EGFP to investigate the utility of the red fluorescent protein dTomato (dTom) (37) to visualize virus infection in living animals and in tissues following necropsy.

It is important to investigate the utility of red fluorescent proteins for pathogenesis studies due to the longer wavelength of emitted light, which significantly enhances tissue penetrance (13). Moreover, expression of the fluorescent proteins from an additional transcription unit (ATU) rather than as fusion proteins has the significant advantage that the entire cytoplasm of the infected cells is flooded with the reporter proteins. This is especially important in studies which involve cells which have very small extensions or processes which interdigitate into the surrounding parenchyma. Such cells can be very difficult to detect using standard immunohistochemical (IHC) techniques, especially when the primary antibody used to detect the virus recognizes antigens which are highly localized in the cell. This is particularly the case when ribonucleocapsid-associated proteins are used, as they form punctate perinuclear intracytoplasmic inclusions (18). Comparison of ferrets infected with rCDVSH, CDVR252, or rCDV5804P, a recombinant ferret-adapted strain that induces a rapidly fatal acute disease course in vivo (44), confirmed the value and generality of the ferret as a small-animal model. Our studies allow dissection of the mechanisms involved in CDV-induced CNS disease and show that virus spread across the blood-brain and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers during an acute disease course results in the induction of a fatal meningoencephalitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Vero cells stably expressing the CDV receptor dog signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM; VerodogSLAM cells) were cultured as described previously (38). CDVR252 was originally isolated from cerebellar tissue from a naturally occurring case of demyelinating encephalitis in a dog (29) and was obtained as a spleen homogenate (10% [wt/vol] suspension) from an infected dog (kindly provided by Mike Oglesbee, Ohio State University), rCDV5804P is a ferret-adapted strain, the derivation of which has been described previously (44), and CDVSH was obtained from the ATCC (ATCC VR-1587). All nonrecombinant and recombinant CDV strains were propagated in VerodogSLAM cells. Stocks of fowlpox virus expressing T7 RNA polymerase (FP-T7), used for the recovery of recombinant CDVs, were generated in chicken embryo fibroblasts (10). Virus titers were determined by a 50% endpoint dilution assay and are expressed in 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50s)/ml. Growth kinetics of CDVSH, rCDVSHEGFP(6), rCDVSHdTom(6), rCDV5804P, and CDVR252 were assessed by infecting VerodogSLAM cells grown in 24-well trays in triplicate with each virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.001 for 1 h at 37°C. Following virus infection, cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline to remove input virus inoculum and incubated at 33°C prior to sample collection. Total virus (cell-associated and supernatant) was collected at 12-h intervals up to 96 h postinfection (h.p.i.), freeze-thawed at −80°C, and clarified by centrifugation. Virus titers, expressed as TCID50/ml, were obtained by endpoint dilution in VerodogSLAM cells.

RNA preparation and RT-PCR.

Total RNA was prepared from TRIzol LS (Invitrogen)-solubilized CDVSH. Amplicons encompassing the full-length CDVSH genome were obtained from six reverse transcription-PCRs (RT-PCRs) using CDV-specific oligonucleotides. Primers used in the amplification of the first and last fragments of the genome were extended to include the NotI restriction site and T7 polymerase promoter and the KasI restriction site, respectively. These unique restriction sites were used to clone the terminal CDV amplicons into the full-length plasmid designed to encode the CDVSH antigenome. Sequences of the oligonucleotide primers are available on request.

Construction of a full-length CDVSH plasmid.

RT-PCR products were cloned into pCR-Blunt II (Invitrogen), and at least three independent clones of each of the six amplicons were sequenced using gene-specific primers. Sequences were assembled and compared using DNA sequence analysis software (DNAStar), and the complete consensus genomic sequence was determined. Clones corresponding to the consensus sequences were used for all subsequent manipulations. Construction of the full-length plasmid encoding the antigenome of CDVSH was based on the plasmid backbone of pMuVJL2 (12), which contained KasI and NotI in the multiple-cloning site (MCS). Two complementary oligonucleotides, priCDVSH(NNSHS)+ (5′-GGC CGC ATA TAT CCA TGG ATA TAT CAT ATG ATA TAT ATT TAA ATA TAT ATA AGC TTA TAT ATA CTA GTA TAT ATG-3′) and priCDVSH(NNSHS)- (5′-GCG CCA TAT ATA CTA GTA TAT ATA AGC TTA TAT ATA TTT AAA TAT ATA TCA TAT GAT ATA TCC ATG GAT ATA TGC-3′), were annealed to produce an oligonucleotide linker containing NcoI, NdeI, SwaI, HindIII, and SpeI restriction sites (underlined) separated by 6-bp spacers with NotI- and KasI-compatible ends. This linker was ligated into NotI- and KasI-linearized pMuVJL2 to generate pCDV(NNSHS). The CDVSH antigenome was assembled by inserting the six RT-PCR amplicons, yielding pCDVSH. This plasmid was further modified to express EGFP or dTom from an ATU downstream of the H-gene open reading frame (position 6). Briefly, a 2,033-bp RsrII and SwaI fragment was amplified using a two-step overlap PCR. A PmeI restriction site was introduced into the sequence encoding the H-gene end (bp 8975 to 8982) of this fragment, and the amplicon was cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO to generate a plasmid designated pCDVSHSH-H-L(PmeI). A 705-bp sequence and a 720-bp sequence, encoding dTom and EGFP, respectively, were amplified using a forward primer extended with the CDV intergenic trinucleotide, phospho-(P) protein gene start, and the Kozak consensus sequence and a reverse primer containing additional H-gene end sequences. Both sets of primers contained PmeI restriction sites and the necessary 5′ and 3′ sequences from the dTom or EGFP open reading frames. The resulting PCR products were cloned into the PmeI site of pCDVSH-H-L(PmeI), which was subsequently digested with RsrII and SwaI restriction enzymes. The resulting DNA fragments were ligated into similarly digested pCDVSH to produce pCDVSHEGFP(6) and pCDVSHdTom(6). All plasmids were sequenced using a Perkin Elmer ABI Prism 310 genetic analyzer, and their integrity was confirmed by PCR and restriction enzyme digestion. Details of the oligonucleotide sequences and cloning strategies are available upon request.

Rescue of recombinant viruses from cDNA.

VerodogSLAM cells, grown to 70% confluence in 6-well plates, were infected with FP-T7 at an MOI of 1 for 45 min. The inoculum was removed, and helper plasmids expressing the MV nucleocapsid (N), phospho- (P), and large proteins of MV (kindly provided by Linda Rennick, Boston University) and the plasmid containing a copy of the full-length CDV antigenome (10 μg) were transfected into the cells over 24 h using Lipofectamine 2000 (Gibco-BRL, Invitrogen Technologies). Transfection mixtures were removed, growth medium was added, and cells were incubated for 24 h. Approximately 105 VerodogSLAM cells were added to each well, and monolayers were monitored for the appearance of a cytopathic effect, as evidenced by syncytium formation. Working stocks of the rCDVs were generated by passage in VerodogSLAM cells. Viruses were characterized by sequencing RT-PCR amplicons of the nucleocapsid (N), P, H, and large (L) genes, with amplification without reverse transcription used as a negative control. The identity of rCDVSH was confirmed by the presence of silent nucleotide changes which differ from the consensus at positions 8026, 12221, 12641, and 14693 (all A → G).

Assessment of neurovirulence of recombinant CDV.

A total of 22 male European, unvaccinated ferrets (Mustela putorius furo), all age 4 months or older, were used in these studies. Animals were inoculated intranasally (i.n.) or intratracheally (i.t.) with virus (104 to 105 TCID50s) and were examined daily for clinical signs of CDV infection. Animals were infected i.n. with 104 TCID50/ml of CDVR252 (n = 6), rCDV5804P (n = 4), or rCDVSHEGFP(6) (n = 3) in the animal facility of the Queens University Belfast (QUB) under an approved Home Office license. A more extensive description of clinical parameters in individual animals from the rCDV5804P-infected group has been reported previously (38). i.n. infection of animals with 105 TCID50s/ml of CDVSH (n = 3) was performed in the Experimental Biology Center at the INRS—Institut Armand-Frappier with approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Infection of ferrets (n = 6) with 105 TCID50s/ml of rCDVSHdTom(6), divided over the i.n. and i.t. routes, was performed at the Erasmus Medical Center with approval by the independent animal experimentation ethical review committee DCC in Driebergen, The Netherlands. Prior to infection, animals were bled and sera were tested for the absence of anti-CDV antibodies using a virus neutralization assay, thus ensuring that the animals would be susceptible to CDV infection (38). Animals were bled on the day of infection and weekly thereafter. Blood samples were processed, and the lymphocyte counts were determined. Upon observations of neurological signs indicative of virus spread to the CNS or a loss of 20% of initial body weight, animals were euthanized and gross and histopathology investigations were performed. Life expectancies between groups of animals were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared using a log rank test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS software, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Macroscopic detection of EGFP and dTom fluorescence and necropsy.

Macroscopic EGFP fluorescence was detected in infected ferrets using a custom-made light-emitting diode (LED) lamp and imaged as described previously (15). dTom fluorescence was monitored using a custom-made lamp containing six 5-volt LEDs (lambertian, green; peak emission, 520 to 550 nm; Luxeon Lumileds) mounted with D535/50 band-pass filters (Chroma). Orange or red goggles or camera filters (Sirchie) were used as emission filters. The color balance of images of macroscopic fluorescence was adjusted using analogous settings in the software Adobe Photoshop CS5. Animals were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of a lethal dose of barbiturates. Gross pathological evaluation was performed by external examination, evisceration, and collection of organ samples in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde for vibratome sectioning and in buffered formalin for microtome processing.

Analysis of vibratome- and microtome-cut tissue sections.

Vibratome-cut brain sections (100 μm) were prepared, counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), and mounted onto glass slides as described previously (26). Thin sections (7 μm) were prepared from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections and stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). CDV distribution in brain tissue was assessed indirectly using a monoclonal antibody which recognizes the N protein (1:3,000; VMRD). An Envision peroxidase system in a liquid 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate–chromogen system (Dako) was used to detect the primary antibody complexes and thus, indirectly, CDV. Dual-labeling indirect immunofluorescence was performed using monoclonal mouse anti-CDV N antibody, a polyclonal rabbit antibody to vimentin (1:200; Dako) or a polyclonal rabbit anti-EGFP antibody (1:500; Invitrogen), and a monoclonal mouse antibody to glial fibrillary acidic protein (1:200; Dako). Bound primary antibodies were detected with a mixture of anti-mouse Alexa 488 and anti-rabbit Alexa 568 (Invitrogen). Sections were counterstained with DAPI hard-set mounting medium (Vector). All indirect immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry experiments were controlled by omitting the primary antibody during staining of the appropriate tissue. Selected histological or immunohistochemically stained tissue sections were digitally scanned using an Aperio Scanscope T3 apparatus with a ×40 objective and were then displayed at a range of magnifications as described previously (25). Vibratome-cut or immunocytochemically stained sections were imaged using Leica TCS SP2 and SP5 microscopes (Leica Microsystems).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete consensus genomic sequence was placed in GenBank under accession number JN896987.

RESULTS

Construction and in vitro characterization of rCDVSH expressing green or red fluorescent proteins.

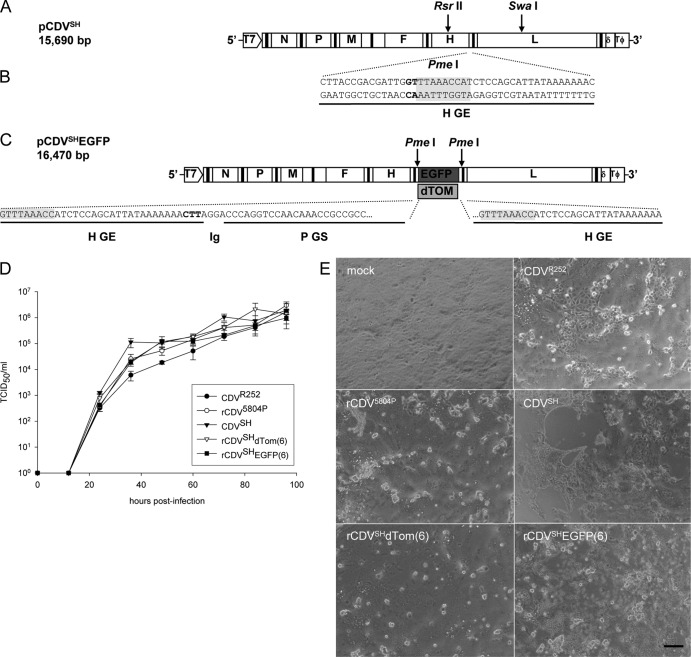

In order to study mechanisms contributing to the development of acute CNS disease, we developed a rescue system for CDVSH and compared the resulting rCDVs in the ferret model with the biological CDVSH, CDVR252, and rCDV5804P strains that have been reported to display different levels of neurovirulence in vivo. A full-length cDNA clone (pCDVSH) (Fig. 1A) was constructed on the basis of the consensus sequence obtained from a stock of virus which had been passaged once in canine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). The sequence of this strain differed by 2 amino acids (H V50I; L V1075I) from that reported previously (35). Following successful recovery of rCDVSH in VerodogSLAM cells (data not shown), two further constructs, pCDVSHEGFP(6) and pCDVSHdTom(6), were assembled by inserting the EGFP or dTom open reading frame in the sixth position of the genome between the H and L genes using a unique PmeI restriction site introduced into the 3′ untranslated region of the H gene (Fig. 1B). Upon rescue of these full-length cDNA clones (Fig. 1C) and amplification of recovered virus in VerodogSLAM cells, multistep growth curves were used to assess the growth kinetics of nonrecombinant and recombinant wild-type CDVs in VerodogSLAM cells (Fig. 1D). Although all viruses attained a similar maximum titer of approximately 106 TCID50s/ml by 96 h.p.i., the growth of CDVR252 in VerodogSLAM cells was significantly slower than that of rCDV5804P, CDVSH, rCDVSHEGFP(6), and rCDVSHdTom(6) at between 24 and 72 h.p.i. This was correlated with lower rates of virus cell-to-cell spread in comparison to those for the other viruses (Fig. 1E). Nonrecombinant and recombinant CDVSH-infected cell monolayers were totally fused at 72 h.p.i. and beginning to detach, while approximately 90% of rCDV5804P-infected cells were fused at this time point. In contrast, discrete syncytia were still visible in CDVR252-infected VerodogSLAM cells at 72 h.p.i., with approximately 50% of cells observed to be present within syncytia.

Fig 1.

Construction and characterization of recombinant CDVs. (A) Schematic representation of pCDVSH full-length infectious clone. A subclone containing the H-L gene boundary was produced following digestion of pCDVSH with RsrII and SwaI to facilitate the introduction of a unique PmeI site (B) as indicated by the gray shading. (C) An additional transcription unit containing EGFP or dTom was inserted at the H-L gene boundary using the unique PmeI site to produce the pCDVSHEGFP(6) and pCDVSHdTom(6) full-length clones. (D) Multistep growth curves of CDVR252, CDV5804P, CDVSH, rCDVSHdTom(6), and rCDVSHEGFP(6) in VerodogSLAM cells. Virus was harvested at 12-h intervals up to 96 h postinfection. Viral titers were determined as the number of TCID50/ml in an endpoint titration test. Measurements shown are averages of triplicates ± SE. (E) Phase-contrast photomicrographs taken at 72 h.p.i. of VerodogSLAM cells with Opti-MEM (mock), CDVR252, CDV5804P, CDVSH, rCDVSHdTom(6), and rCDVSHEGFP(6). Bar, 200 μm.

Recombinant CDVSH and CDV5804P induce a more acute disease course than CDVR252 in the ferret.

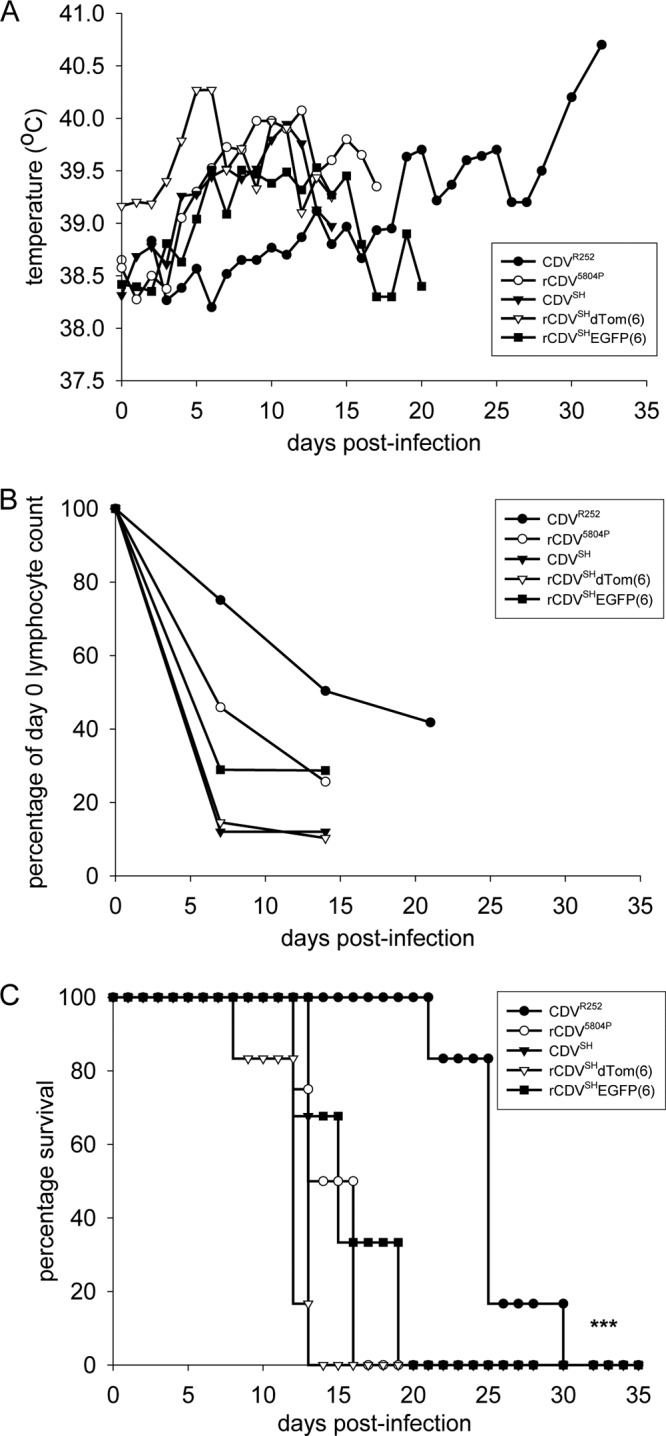

The pathogenesis induced by nonrecombinant and recombinant CDVSH in the ferret was compared to that induced by rCDV5804P and CDVR252 by infecting groups of ferrets i.n. to mirror the natural route of virus transmission. Animals in all groups developed a range of clinical signs characteristic of distemper, including ocular discharge and conjunctivitis, diarrhea, lethargy, and a decrease in body weight. Skin rash was apparent in only 2 out of 6 animals infected with CDVR252 but was present in all other CDV-infected ferrets from 9 to 11 d.p.i. onwards. While a rapid increase in body temperature was observed in the CDVSH-, rCDVSH-, and rCDV5804P-infected groups, fever was not observed in CDVR252-infected ferrets until 20 d.p.i. (Fig. 2A). Lymphopenia was a prominent feature in animals from all groups, but again, a difference was observed in CDVR252-infected ferrets, in which the reduction in the number of lymphocytes occurred at a lower rate (Fig. 2B). Virus was recovered from PBMCs isolated from infected animals at 7 d.p.i., and virus was isolated from urine and ocular, nasal, and throat swabs at necropsy (data not shown). All animals infected with CDVSH, rCDVSHEGFP(6), rCDVSHdTom(6), or rCDV5804P succumbed to the disease at between 14 and 20 d.p.i., apart from one rCDVSHdTom(6)-infected ferret that was euthanized on day 9 due to a severe respiratory infection (Fig. 2C). Minor differences in the time of death between the groups were not found to be statistically significant and most likely reflect differences in the amount of virus used to infect the different groups. In contrast, a more extended disease course of 32 days was observed in CDVR252-infected ferrets and was found to be significantly longer (P < 0.05) than that observed in rCDV5804P-, CDVSH-, rCDVSHEGFP(6)-, or rCDVSHdTom(6)-infected ferrets (Fig. 2C). Clinical signs indicative of virus spread to the CNS, such as seizures, were observed only in CDVSH- or CDVSHEGFP(6)-infected ferrets. Upon observation of these signs, the animals were euthanized.

Fig 2.

Course of disease in ferrets infected with nonrecombinant or recombinant CDV strains. (A) Body temperatures; (B) differential lymphocyte counts normalized for each animal to numbers of lymphocyte present at day 0; (C) survival curves. CDVR252, n = 6; rCDV5804P, n = 4; CDVSH, n = 3, rCDVSHdTom(6), n = 6; rCDVSHEGFP(6), n = 3. Data are shown as means per group. ***, the life expectancy of CDVR252-infected ferrets estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method was significantly greater (P < 0.05) than that of other ferret groups upon comparison using a log rank test.

Expression of EGFP and dTom from an ATU enhances the pathological assessment of rCDVSH-infected ferrets.

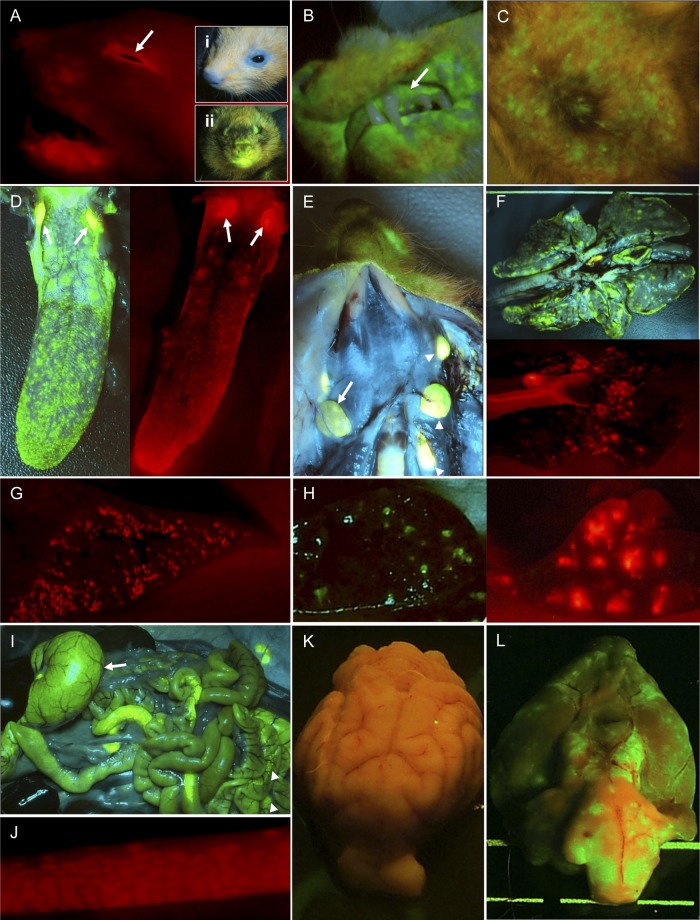

We have previously shown that macroscopic foci of fluorescence can be visualized in animals infected with an rMV expressing EGFP with high sensitivity (15). This technology was applied to rCDVSHEGFP(6)-infected ferrets to monitor virus spread in skin and mucosal surfaces and was extended to analyze the efficacy of the red fluorescent protein (dTom) as an alternative and possibly more sensitive macroscopic indicator of virus infection due to the longer wavelength of fluorescence emitted. Intense red fluorescence was visible on the head of rCDVSHdTom(6)-infected animals, with a prominent ring of fluorescence visible around the mucosal epithelium of the eye and extensive virus infection present along the jawline (Fig. 3A). While no fluorescence was detected in the skin of nonfluorescent CDVR252-infected ferrets, green fluorescence was consistently detected around the mouth and nose of rCDVSHEGFP(6)-infected ferrets (Fig. 3A, insets). Extensive EGFP expression in the gingiva (Fig. 3B) was apparent at 14 d.p.i. with concomitant infection of skin (Fig. 3C). The widespread skin involvement preceded the appearance of the severe skin rash. During the necropsies, the use of EGFP and dTom as markers of virus infection enabled precise and selective sampling of infected tissues for vibratome and histology processing. Such an approach provides tremendous advantages in terms of ensuring targeted pathological assessments, as it permits maximum coverage with minimal sampling due to the selection of prevalidated tissue blocks. The expression of EGFP or dTom from an ATU did not impede either the dissemination or the extent of virus infection, and high levels of EGFP and dTom expression, indicative of large numbers of CDV-infected cells, were visible in the tongue, tonsils (Fig. 3D), and other lymphoid tissues, including the spleen and Peyer's patches (Fig. 3H to J). The red fluorescence that localized within germinal centers, observed in a cross section through the spleen of an rCDVSHdTom(6)-infected animal, was observed to be more intense than the green fluorescence present in the spleen of an rCDVSHEGFP(6)-infected animal (Fig. 3H), confirming our hypothesis that this reporter protein might serve as a more sensitive indicator of infection due to the emission properties of the fluorescent protein. Virus infection was also evident in a number of peripheral tissues, including the salivary gland (Fig. 3E, arrow), all four lobes of the lung, with especially prominent infection along the periphery (Fig. 3F), and the liver (Fig. 3G). Macroscopic examination of a control brain from an animal infected with nonfluorescent CDVR252 did not show any evidence of macroscopic fluorescence at necropsy (Fig. 3K), whereas extensive infection was observed in the meninges over large areas of the brain surface from the olfactory bulb to the cerebellum of an rCDVSHEGFP(6)-infected animal (Fig. 3L).

Fig 3.

Detection of macroscopic fluorescence in tissues from rCDVSHEGFP(6) (green)- or rCDVSHdTom(6) (red)-infected ferrets. (A) Extensive virus infection of mucosal surface surrounding the eye (arrow), with infection also observed in the skin beneath the mouth. No green fluorescence is observed around the mouth or nose of a CDVR252-infected ferret (inset i), in contrast to the high levels of fluorescence observed around analogous regions of an rCDVSHEGFP(6)-infected ferret (inset ii). (B) Infection of the gingiva (arrow). (C) Infection of skin epidermis in the abdominal region. (D) Numerous discrete foci of infection were visible on the surface of the tongue, with prominent infection of adjacent lymphoid tissues and tonsils (arrows). (E) Infection of salivary gland (arrow) and lymph nodes (arrowheads). (F) Multiple large foci of infection were observed throughout all lobes of the lung, with virus infection observed at the edges of lung lobes. (G) Many foci of infection are visible in a cross section through the liver. (H) Virus-infected follicles visible in a cross section of the spleen are more intensely fluorescent in an rCDVSHdTom(6)-infected animal (right). (I) Infection of the stomach (arrow) and B cell follicles with Peyer's patches (arrowheads) in the gastrointestinal tract. (J) Multiple CDV-infected B cell follicles within a Peyer's patch in the ileum. (K) No fluorescence is visible in the leptomeninges of a CDVR252-infected ferret. (L) Extensive virus infection of the leptomeninges on the surface of the brain of an rCDVSHEGFP(6)-infected ferret.

Acute CDV infection leads to spread of virus into the subarachnoid space.

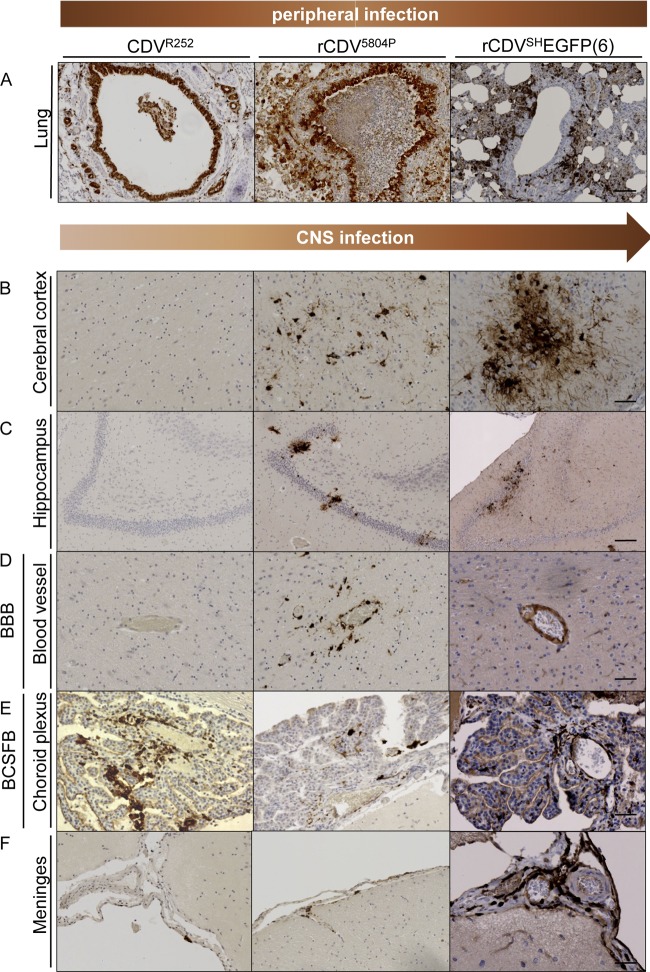

The distribution of rCDV5804P and rCDVSHEGFP(6) or rCDVSHdTom(6), all of which induced a rapidly fatal disease course, was examined in immunohistochemically stained tissues obtained from infected ferrets following euthanasia due to severe clinical signs and compared to the distribution of CDVR252, which produces a slower disease course in vivo, in tissues also taken at the disease endpoint. While lymphoid tissues were heavily infected in all animals (data not shown), dramatic differences in the extent of epithelial cell infection were observed. Infection of the entire bronchial epithelium was readily observed in the lungs of CDVR252- and rCDV5804P-infected animals, whereas infection of bronchial epithelial cells was focal in rCDVSH-infected lung tissue (Fig. 4A). This virus distribution was consistently observed in the epithelium of other tissues, including the trachea, esophagus, bladder, and the renal pelvis of the kidney (data not shown). Detailed examination of the brain parenchyma, including the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, of CDVR252-infected animals did not reveal any evidence for virus-infected neurons or glial cells (Fig. 4B and C). In contrast, small foci of infection were present in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus of rCDV5804P-infected ferrets, with larger foci evident in these regions in rCDVSH-infected brain tissue. Virus infection of endothelial cells surrounding blood vessels, the tight junctions of which comprise the blood-brain barrier within the brain parenchyma, was detected only in brain sections from rCDV5804P- and rCDVSH-infected animals (Fig. 4D).

Fig 4.

Comparative analysis of the distribution of different nonrecombinant or recombinant CDV strains in ferrets. Immunohistochemical analysis of CDVR252-infected (left column) (30 d.p.i.), rCDV5804P-infected (middle column) (15 d.p.i.), and rCDVSHEGFP-infected (right column) (17 d.p.i.) microtome-cut tissue sections. (A) All viruses spread extensively in the periphery, with prominent infection observed in bronchial epithelial cells lining the bronchus in the lung. (B to F) Differential virus infection of the brain was observed between wild-type CDV strains. Virus infection was analyzed in the cerebral cortex of the frontal lobe (B), hippocampus (C), cerebral blood vessels (blood-brain barrier [BBB]) (D), choroid plexus (blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier [BCSFB]) (E), and the meninges (F). No positive immunostaining was observed upon omission of the primary antibody during immunohistochemical staining of lung or brain sections. Bars, 100 μm (A and C) and 50 μm (B and D to F).

An alternative route of entry for CDV into the CNS is via the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier through the epithelial cells of the choroid plexus. Subsequent virus release into the CSF would enable virus spread to meningeal cell layers. To investigate this hypothesis, we examined the choroid plexus from all three CDV strains at terminal stages of the disease. Infection in the choroid plexus was present in all cases (Fig. 4E) and predominately involved infiltrating CDV-infected leukocytes. Infection of choroid plexus epithelial cells was rarely observed and when present involved only small numbers of cells (Fig. 4E). In contrast to widespread infection of the choroid plexus, extensive examination of ependymal cells lining the walls of ventricles revealed only small numbers of infected cells. Examination of meningeal cell layers revealed very isolated CDV-infected arachnoid cells in CDVR252-infected animals, focal areas of infection in rCDV5804P-infected tissue, but extensive infection of pia and arachnoid cells in rCDVSH-infected brain tissue (Fig. 4F).

Hematogenous spread of CDVSH into the cerebrospinal fluid leads to acute viral meningoencephalitis.

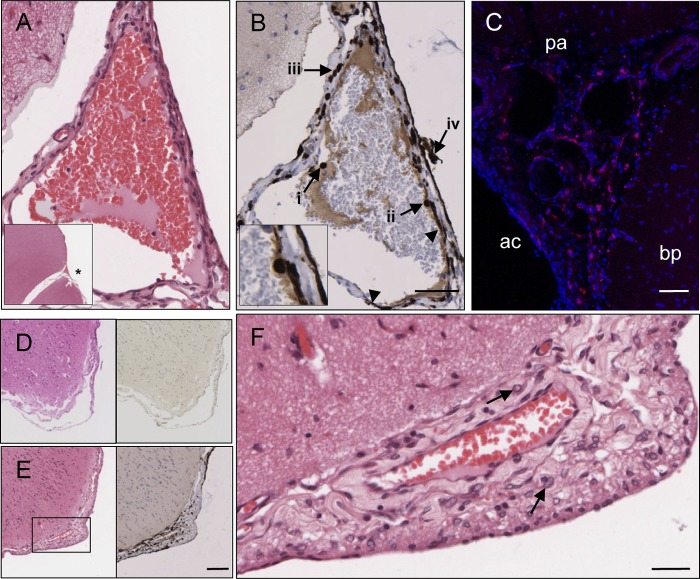

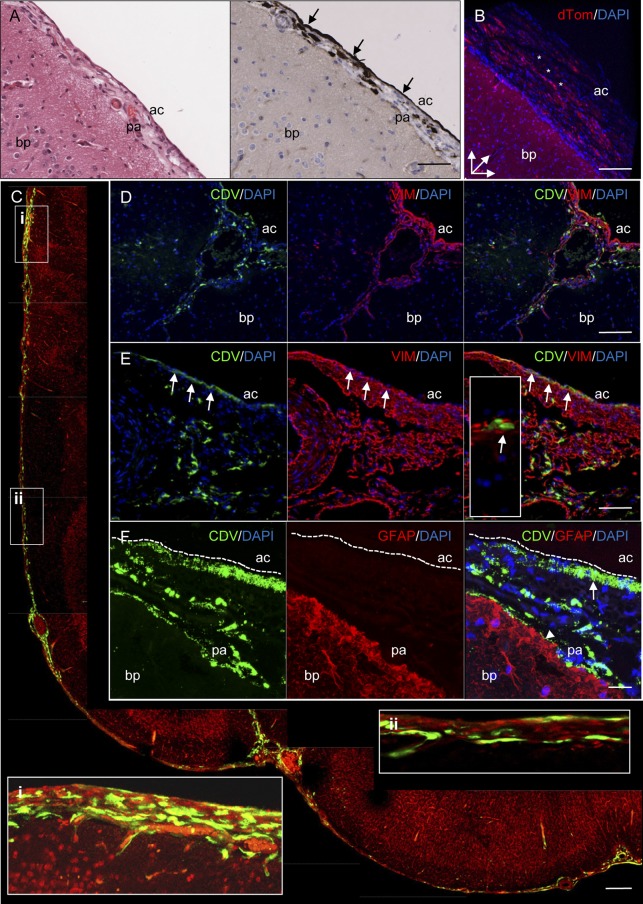

Microtome- and vibratome-cut brain sections were used to investigate the routes of virus spread from the periphery into the meningeal cell layers of rCDVSH-infected animals. Spread of virus was facilitated by dissemination of infected leukocytes from the blood across the blood-brain barrier, formed by endothelial cells in the wall of meningeal blood vessels and/or concomitant infection of endothelial cells (Fig. 5A and B), into the CSF. Infected leukocytes were present in all stages of transmigration from blood vessels into the CSF, including individual leukocytes in the lumen (Fig. 5B, arrow i), attached to the vessel wall (Fig. 5B, arrow ii), passing through the wall of a blood vessel (Fig. 5B, arrow iii), and in the subarachnoid space (Fig. 5B, arrow iv). In addition, CDV-infected endothelial cells were commonly observed in meningeal blood vessels (Fig. 5B, arrowheads). These data suggest that virus-infected endothelial cells and hematogenous spread of virus from meningeal blood vessels are the primary mechanism responsible for triggering the dramatic virus infection of the meninges. This was confirmed by analysis of a CSF sample obtained from an infected animal which revealed the presence of fluorescent virus-infected cells (data not shown). Analysis of 200-μm brain tissue sections revealed the presence of many CDV-infected leukocytes in the subarachnoid space (Fig. 5C). Entry of virus into the CSF also occurs at early time points, as isolated infected leukocytes and arachnoid cells were observed in the meninges of an rCDVSHdTom(6)-infected ferret that was euthanized at 9 d.p.i. (data not shown). Analysis of serial H&E- and IHC-stained sections of the meninges of infected animals showed that while no virus or inflammation was apparent in the meninges of CDVR252-infected animals (Fig. 5D), a multitude of virus-infected cells was observed concomitantly with a thickening of the meninges in rCDVSHEGFP(6)-infected animals (Fig. 5E). This increase in size of the leptomeninges was characterized by an influx of inflammatory cells, predominately mononuclear cells, and edema (Fig. 5F).

Fig 5.

Spread of wild-type CDV from leptomeningeal vasculature into the CSF. Brain sections from rCDVSHEGFP(6)-infected (A, B, E, and F) (17 d.p.i.), rCDVSHdTom(6)-infected (14 d.p.i.) (C), and CDVR252-infected (30 d.p.i.) ferrets were analyzed for endothelial cell infection and/or leukocyte trafficking across the walls of meningeal blood vessels in the subarachnoid space. (A and B) Serial H&E-stained (A) and immunohistochemically stained (B) sections of a meningeal blood vessel. The asterisk in the inset of panel A indicates the position of this blood vessel in relation to surrounding brain tissue. (B) Virus infection is visible in endothelial cells (arrowheads), with CDV-infected cells present within the lumen (arrow i), attached to the wall (arrow ii and inset), and transmigrating across the wall of the blood vessel (arrow iii) and in the adjacent subarachnoid space (arrow iv). Bar, 50 μm (A and B). (C) Numerous infected leukocytes present in the subarachnoid space of the meninges. bp, brain parenchyma; ac, arachnoid; pa, pia mater. Bar, 60 μm. (D) Serial H&E-stained (left) and CDV N immunohistochemically stained (right) sections showing an absence of inflammation and virus infection in the meninges in a CDVR252-infected animal. (E) Serial H&E-stained (left) and CDV N immunohistochemically stained (right) sections showing that thickening and inflammation of the meninges are associated with rCDVSHEGFP(6) infection. Bar, 100 μm (D and E). (F) Higher magnification of boxed area in panel D (H&E staining) showing infiltration of myeloid cells (arrows) into the subarachnoid space. Bar, 25 μm.

A high-resolution three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of a cross section through the outer cortex of an rCDVSHdTom(6)-infected ferret brain facilitated the visualization of interconnected virus-infected meningothelial cells in the arachnoid cell layers on the brain surface (Fig. 6B). Widespread infection of the leptomeninges by macroscopic imaging was confirmed by direct detection of EGFP fluorescence in 100-μm-thick vibratome-cut brain sections. In many of these sections, infection of interconnected cells was observed in the meninges surrounding large portions of the cerebral hemisphere (Fig. 6C). Further high-resolution confocal imaging demonstrated extensive infection of meningothelial cells with interdigitating cell processes and infiltrating leukocytes in both the pia mater and arachnoid in rCDVSHEGFP(6)-infected animals (Fig. 6C, insets). The identity of virus-infected cells observed in these cell layers was investigated using a polyclonal antibody against vimentin, a type III intermediate filament which is expressed in mesenchymally derived cells. Examination of brain sections dually labeled with antibodies against vimentin and CDV nucleoprotein showed that vimentin is a specific marker of cells present within the meninges rather than the brain parenchyma (Fig. 6D). The majority of these cells consisted of meningothelial cells present in the pia mater and arachnoid, with positive staining also observed in smaller numbers of endothelial cells surrounding meningeal blood vessels. Further analysis confirmed that CDV antigen is present within vimentin-positive meningothelial cells of the arachnoid along the surface of the brain (Fig. 6E), with interconnected virus-infected cells observed in this meningeal cell layer in the majority of brain sections. Analysis of dually labeled microtome-cut brain sections indicated that while extensive infection of cells in the pia mater and arachnoid was apparent, there was no cell-to-cell spread of CDV from the meningeal cells to the intimately associated glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive astrocytes constituting the glia limitans (Fig. 6F) that separates the meningeal cell layers from the underlying brain parenchyma.

Fig 6.

Detection of rCDVSHEGFP(6) (A and C to F) (17 d.p.i.) or rCDVSHdTom(6) (B) (14 d.p.i.) in the meninges by immunohistochemistry (A), direct detection of a fluorescent protein (B and C), or indirect immunofluorescence (D to F). (A) Serial H&E-stained (left) and immunohistochemically stained (right) sections of meninges showing infection of the arachnoid cell layer (arrows). Bar, 100 μm. (B) 3D confocal reconstruction of virus-infected arachnoid cells (red) (asterisks) on the surface of the brain. Bar, 125 μm. (C) Montage of individual confocal photomicrographs showing CDV infection (green) in meningeal cell layers in the frontal lobe of a vibratome-cut brain section. Inserts i and ii show higher-magnification images (rotated clockwise) of the indicated regions. Nuclei were visualized by propidium iodide. Bar, 200 μm. (D) Single-color and dual-immunofluorescence photomicrographs illustrating specificity of vimentin (VIM) immunostaining (red) for meningothelial cells of the pia mater and arachnoid and endothelial cells lining meningeal blood vessels. CDV-infected cells (green) colocalize with vimentin-positive cells in the meninges. Bar, 150 μm. (E) Colocalization of CDV antigen (green) and vimentin-positive meningothelial cells (red) within the arachnoid layer of the meninges (arrows). A higher magnification of CDV-infected meningothelial cells is shown in an inset. Bar, 75 μm. (F) Single-color and dual-immunofluorescence photomicrographs of extensive infection of the arachnoid (arrow) and pia mater (arrowhead). No colocalization was observed between CDV-infected cells (green) and GFAP-positive astrocytes (red) of the glia limitans. Bar, 20 μm. DAPI was used as a nuclear counterstain in panels B and C. bp, brain parenchyma; ac, arachnoid; pa, pia mater.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we generated an rCDVSH that causes a lethal, systemic infection in the ferret model to address the question of how the virus enters the CNS. We show that CDV strains inducing a rapid disease course spread across the blood-brain and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers into the subarachnoid space in the later stages of the disease, inducing a fatal meningoencephalitis. The ability to sensitively detect rCDVSH-infected tissues at necropsy through the detection of either green or red fluorescent proteins enhanced our ability to trace pathways of virus infection in the periphery and in the CNS and facilitated our understanding of how the virus spreads through meningeal cell layers at the single-cell level. Interestingly, differences as to the brightness and sensitivity of these two fluorescent proteins in peripheral and CNS-derived tissues were apparent. The red fluorescence observed in rCDVSHdTom(6)-infected tissues at necropsy was more intense than the green fluorescence emitted from tissues in which EGFP was expressed from the viral ATU. This can largely be attributed to the greater ability of dTom to penetrate through tissue due to the longer wavelength of light emitted by this protein in comparison to EGFP. This finding is highly relevant for virologists using vital, multimodal imaging technologies to address questions of virus spread in vivo or gene therapists who are engineering replicating viruses to target tumor cells or deliver foreign antigens in xenograft models. Conversely, EGFP proved to be a more sensitive indicator of virus infection within the brain parenchyma upon examination of vibratome-cut brain sections, as the high level of red autofluorescence emitted by neural tissue hindered the sensitivity of dTom in this particular application. Therefore, the choice of fluorescent protein to be used for macroscopic and microscopic imaging in tissues is dependent on the specific tissue(s) targeted by the virus in vivo.

A number of studies have reported histological indications of meningoencephalitis in CDV-infected animals. Pathological analysis of both natural and experimental CDV infections in dogs has shown evidence of extensive infiltration of mononuclear cells containing intranuclear inclusions and occasional syncytia in meningeal cell layers (14, 42). It has also been suggested that focal spread of CDV across the glia limitans from infected cells in the pia mater to neurons in the underlying brain parenchyma may provide an additional route of neuroinvasion in dogs (7, 8). Meningoencephalitis is also a feature of CDV infection of other species, with distemper inclusion bodies observed in the meninges of infected foxes (21) and histological evidence of meningoencephalitis reported in black-footed ferrets and a Siberian tiger (33, 45). While some morbilliviruses such as measles or rinderpest virus rarely spread to the CNS, meningoencephalitis has also been reported in seals and dolphins infected with phocine distemper and cetacean morbilliviruses, respectively (16, 17, 23). However, data on the distribution of morbillivirus antigen in the meninges of infected animals or routes of entry into the CSF are scarce.

Entry of CDV into the CNS is known to occur through multiple mechanisms. Infection of olfactory neurons lining the nasal cavity and subsequent spread along axons through the cribriform plate enable direct infection of neurons in the olfactory bulb, thus enabling the virus to bypass the blood-brain barrier (34). However, the widespread distribution of foci of infection throughout the brain parenchyma of CDV-infected animals is indicative of a prominent role for hematogenous spread via infected lymphocytes following viremia (6). Infiltration of CDV-infected leukocytes from blood vessels into the choroid plexus was a consistent feature in ferrets infected with all three strains utilized in this study, indicating the generality of our conclusions. While CDVR252-infected cells were readily detected in the choroid plexus, the dearth of infected cells in the meninges and brain parenchyma mirrors results reported in one previous study of this strain in this model (6). In addition, the relative paucity of infected epithelial cells in the choroid plexus proves that spread of virus across the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier via budding from infected epithelial cells is a minor factor contributing to the focal and extensive virus infection in the meninges of rCDV5804P- and rCDVSH-infected animals, respectively. Collectively, these data suggest that choroid plexus infection alone is insufficient to induce the meningoencephalitis observed in rCDVSH- and rCDV5804P-infected ferrets.

Hematogenous spread of virus-infected leukocytes from meningeal blood vessels into the CSF was a consistent and prominent finding in all rCDVSH-infected animals. All stages of the transmigration of leukocytes across meningeal blood vessels were readily visualized within the subarachnoid space. Concomitantly with virus spread from infected endothelial cells surrounding meningeal blood vessels, this resulted in extensive infection of meningothelial cells in the pia and arachnoid cell layers over a large proportion of the brain surface. Attempts to confirm the identity of infiltrating leukocyte populations observed in the meninges were hampered by the absence of antibodies cross-reactive for ferret leukocytes in formalin-fixed tissue sections. While endothelial cells surrounding pial microvessels are constituents of the blood-brain barrier, it is increasingly clear that important differences between vessels within the brain parenchyma and those present in the subarachnoid space exist. In contrast to cerebral vessels, pial microvessels are not ensheathed by astrocytes and display heterogeneity in the tightness of endothelial tight junctions (2). While this may facilitate migration of leukocytes into the subarachnoid space during routine immune surveillance, pial microvessels might also be more amenable than cerebral microvessels to the migration of rCDVSH-infected leukocytes.

Viral meningitis can occur as a serious complication of a number of common childhood infections, including varicella-zoster virus, enterovirus, and mumps virus (31, 36, 43), and in rare cases has also been a complication associated with measles (27, 32). The pathological consequences of extensive viral replication in meningeal cell layers have recently been demonstrated in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected mice (24). This study highlighted the role of myelomonocytic cells in mediating breakdown of the blood-brain barrier in infected animals following their recruitment by CD8+ T lymphocytes to sites of viral replication in the pia and arachnoid layer. Breakdown of the blood-brain barrier was demonstrated by leakage of Evans blue into the brain parenchyma. Interestingly, breakdown of this barrier in CDVSH-infected ferrets late in the disease has also been recently reported (35) and may facilitate CDV neuroinvasion. In addition, disruption of this barrier is known to cause seizures (28) and thus may contribute to the neurological signs that we report in infected animals in the later stages of the disease.

In summary, we have developed a reverse genetics system for a CDV strain which can be used to generate highly pathogenic neuroinvasive recombinant viruses. We have proved that the virus rapidly induces acute meningoencephalitis in ferrets and have shown that hematogenous spread of this highly lymphotropic virus is the key mechanism by which the virus accesses the CSF. This model sets the baseline for analysis of meningeal cell layers in infected animals that may highlight the role of inflammatory immunomodulators in mediating blood-brain barrier breakdown in the end stages of the disease and thus provide an excellent model system to dissect mechanisms contributing to the development of acute viral meningitis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff of the Tissue Core Technology Unit, QUB, Bert Rima and Ingrid Allen, QUB, and Brian Herron (consultant neuropathologist) for helpful discussions and Geert van Amerongen, Selma Yüksel, Joyce Verburgh, and the zoo technicians of the NVI in Bilthoven, The Netherlands, for technical assistance. We appreciate the assistance and helpful comments made by Dorian McGavern (Viral Immunology and Intravital Imaging Unit, NINDS, NIH) in reviewing some of the pathological slides.

This work was funded by the Northern Ireland Research and Development Office [ID-RRGC(9.1)].

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 2 May 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Ackermann A, Guelzow T, Staeheli P, Schneider U, Heimrich B. 2010. Visualizing viral dissemination in the mouse nervous system, using a green fluorescent protein-expressing Borna disease virus vector. J. Virol. 84:5438–5442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allt G, Lawrenson JG. 1997. Is the pial microvessel a good model for blood-brain barrier studies? Brain Res. Rev. 24:67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Appel M. 1969. Pathogenesis of canine distemper. Am. J. Vet. Res. 30:1167–1182 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Appel MJ, et al. 1991. Canine distemper virus infection and encephalitis in javelinas (collared peccaries). Arch. Virol. 119:147–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Axthelm MK, Krakowka S. 1987. Canine distemper virus: the early blood brain barrier lesion. Acta Neuropathol. 75:27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Axthelm MK, Krakowka S, Gorham JR. 1987. Canine distemper virus: in vivo virulence of in vitro-passaged persistent virus strains. Am. J. Vet. Res. 48:227–234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Baumgärtner W, Orvell C, Reinacher M. 1989. Naturally occurring canine distemper virus encephalitis: distribution and expression of viral polypeptides in nervous tissues. Acta Neuropathol. 78:504–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beineke A, Puff C, Seehusen F, Baumgärtner W. 2009. Pathogenesis and immunopathology of systemic and nervous canine distemper. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 127:1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bonami F, Rudd PA, von Messling V. 2007. Disease duration determines canine distemper virus neurovirulence. J. Virol. 81:12066–12070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Britton P, et al. 1996. Expression of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase in avian and mammalian cells by a recombinant fowlpox virus. J. Gen. Virol. 77:963–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reference deleted.

- 12. Chambers P, Rima BK, Duprex WP. 2009. Molecular differences between two Jeryl Lynn mumps virus vaccine component strains, JL5 and JL2. J. Gen. Virol. 90:2973–2981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deliolanis NC, et al. 2008. Performance of the red-shifted fluorescent proteins in deep-tissue molecular imaging applications. J. Biomed. Opt. 13:044008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Demonbreun WA. 1937. The histopathology of natural and experimental canine distemper. Am. J. Pathol. 13:187–212.9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Swart RL, et al. 2007. Predominant infection of CD150+ lymphocytes and dendritic cells during measles virus infection of macaques. PLoS Pathog. 3:e178 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Di Guardo G, et al. 2011. Morbilliviral encephalitis in a striped dolphin Stenella coeruleoalba calf from Italy. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 95:247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Duignan PJ, Sadove S, Saliki JT, Geraci JR. 1993. Phocine distemper in harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) from Long Island, New York. J. Wildl. Dis. 29:465–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Duprex WP, et al. 2000. In vitro and in vivo infection of neural cells by a recombinant measles virus expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein. J. Virol. 74:7972–7979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fragkoudis R, et al. 2009. Neurons and oligodendrocytes in the mouse brain differ in their ability to replicate Semliki Forest virus. J. Neurovirol. 15:57–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gillespie JH, Rickard CG. 1956. Encephalitis in dogs produced by distemper virus. Am. J. Vet. Res. 17:103–108 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Green R, Evans CA. 1939. A comparative study of distemper inclusions. Am. J. Epidemiol. 29:73–87 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Harder TC, et al. 1995. Phylogenetic evidence of canine distemper virus in Serengeti's lions. Vaccine 13:521–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jauniaux T, et al. 2001. Morbillivirus in common seals stranded on the coasts of Belgium and northern France during summer 1998. Vet. Rec. 148:587–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim JV, Kang SS, Dustin ML, McGavern DB. 2009. Myelomonocytic cell recruitment causes fatal CNS vascular injury during acute viral meningitis. Nature 457:191–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lemon K, Rima BK, McQuaid S, Allen IV, Duprex WP. 2007. The F gene of rodent brain-adapted mumps virus is a major determinant of neurovirulence. J. Virol. 81:8293–8302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ludlow M, Duprex WP, Cosby SL, Allen IV, McQuaid S. 2008. Advantages of using recombinant measles viruses expressing a fluorescent reporter gene with vibratome slice technology in experimental measles neuropathogenesis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 34:424–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Luzi P, Leoncini L, Valassina M, Federico A, Palma L. 1997. Chronic progressive leptomeningitis associated with measles virus. Lancet 350:338–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marchi N, et al. 2007. Seizure-promoting effect of blood-brain-barrier disruption. Epilepsia 48:732–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McCullough B, Krakowka S, Koestner A, Shadduck J. 1974. Demyelinating activity of canine distemper virus isolates in gnotobiotic dogs. J. Infect. Dis. 130:343–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Metzler AE, Higgins RJ, Krakowka S, Koestner A. 1980. Virulence of tissue culture-propagated canine distemper virus. Infect. Immun. 29:940–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mirand A, et al. 2008. Prospective identification of enteroviruses involved in meningitis in 2006 through direct genotyping in cerebrospinal fluid. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:87–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Purdham DR, Batty PF. 1974. A case of acute measles meningoencephalitis with virus isolation. J. Clin. Pathol. 27:994–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Quigley KS, et al. 2010. Morbillivirus infection in a wild Siberian tiger in the Russian Far East. J. Wildl. Dis. 46:1252–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rudd PA, Cattaneo R, von Messling V. 2006. Canine distemper virus uses both the anterograde and the hematogenous pathway for neuroinvasion. J. Virol. 80:9361–9370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rudd PA, Bastien-Hamel LE, von Messling V. 2010. Acute canine distemper encephalitis is associated with rapid neuronal loss and local immune activation. J. Gen. Virol. 91:980–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Saito H, et al. 1996. Isolation and characterization of mumps virus strains in a mumps outbreak with a high incidence of aseptic meningitis. Microbiol. Immunol. 40:271–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shaner NC, et al. 2004. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:1567–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Silin D, Lyubomska O, Ludlow M, Duprex WP, Rima BK. 2007. Development of a challenge-protective vaccine concept by modification of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase of canine distemper virus. J. Virol. 81:13649–13658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stephensen CB, et al. 1997. Canine distemper virus (CDV) infection of ferrets as a model for testing Morbillivirus vaccine strategies: NYVAC- and ALVAC-based CDV recombinants protect against symptomatic infection. J. Virol. 71:1506–1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Summers BA, Greisen HA, Appel MJG. 1978. Possible initiation of viral encephalomyelitis in dogs by migrating lymphocytes infected with distemper virus. Lancet ii:187–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Summers BA, Greisen HA, Appel MJG. 1984. Canine distemper encephalomyelitis: variation with virus strain. J. Comp. Pathol. 94:65–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Summers BA, Appel MJG. 1985. Syncytia formation: an aid in the diagnosis of canine distemper encephalomyelitis. J. Comp. Pathol. 95:425–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tavazzi E, et al. 2008. Varicella zoster virus meningo-encephalo-myelitis in an immunocompetent patient. Neurol. Sci. 29:279–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. von Messling V, Springfield C, Devaux P, Cattaneo R. 2003. A ferret model of canine distemper virus virulence and immunosuppression. J. Virol. 77:12579–12591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Williams ES, Thorne ET, Appel MJ, Belitsky DW. 1988. Canine distemper in black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes) from Wyoming. J. Wildl. Dis. 24:385–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]