Abstract

Between 2007 and 2009, oseltamivir resistance developed among seasonal influenza A/H1N1 (sH1N1) virus isolates at an exponential rate, without a corresponding increase in oseltamivir usage. We hypothesized that the oseltamivir-resistant neuraminidase (NA), in addition to being relatively insusceptible to the antiviral effect of oseltamivir, might confer an additional fitness advantage on these viruses by enhancing their transmission efficiency among humans. Here we demonstrate that an oseltamivir-resistant clinical isolate, an A/Brisbane/59/2007(H1N1)-like virus isolated in New York State in 2008, transmits more efficiently among guinea pigs than does a highly similar, contemporaneous oseltamivir-sensitive isolate. With reverse genetics reassortants and point mutants of the two clinical isolates, we further show that expression of the oseltamivir-resistant NA in the context of viral proteins from the oseltamivir-sensitive virus (a 7:1 reassortant) is sufficient to enhance transmissibility. In the guinea pig model, the NA is the critical determinant of transmission efficiency between oseltamivir-sensitive and -resistant Brisbane/59-like sH1N1 viruses, independent of concurrent drift mutations that occurred in other gene products. Our data suggest that the oseltamivir-resistant NA (specifically, one or both of the companion mutations, H275Y and D354G) may have allowed resistant Brisbane/59-like viruses to outtransmit sensitive isolates. These data provide in vivo evidence of an evolutionary mechanism that would explain the rapidity with which oseltamivir resistance achieved fixation among sH1N1 isolates in the human reservoir.

INTRODUCTION

In January 2008, Norwegian authorities reported to the World Health Organization a sharp increase in the prevalence of oseltamivir resistance among seasonal influenza A/H1N1 (sH1N1) virus isolates (55). Within 5 months, 25% of European isolates encoded a specific resistance mutation, a histidine-to-tyrosine substitution at position 275 of the viral neuraminidase (NA-H275Y) (53); by 2009, it was found in 96% of sH1N1 isolates worldwide (54). The United States witnessed a similar exponential rise, with 0.7% of isolates resistant in 2007, 10.9% in 2008, and 99.3% in 2009 (10, 11). The emergence of oseltamivir resistance coincided with the circulation of a new drift variant characterized by A/Brisbane/59/2007(H1N1), which subsequently replaced A/Solomon Islands/3/2006 as the sH1N1 vaccine strain (19).

The pervasiveness and persistence of the oseltamivir-resistant NA, essentially supplanting the oseltamivir-susceptible NA among sH1N1 viruses within 2 years, was entirely unexpected; prior data from both in vitro experiments (e.g., Fig. 1 in reference 1 and Fig. 1 in reference 25) and in vivo studies (reference 20, Fig. 2 and 3 in reference 25, and Fig. 2c in reference 57) suggested that the acquisition of the H275Y mutation in the sH1N1 NA came at some cost to viral fitness. In contrast, significant in vitro growth deficits were not seen in 2007-2008 resistant sH1N1 isolates, relative to their sensitive counterparts (2, 46). It has since been shown that permissive mutations found in the Brisbane/59 NA (including V234M, R222Q, and D344N) appear to compensate for deficient protein folding or stability in older H275Y-encoding sH1N1 strains (5) or to fine-tune enzymatic substrate affinity (14).

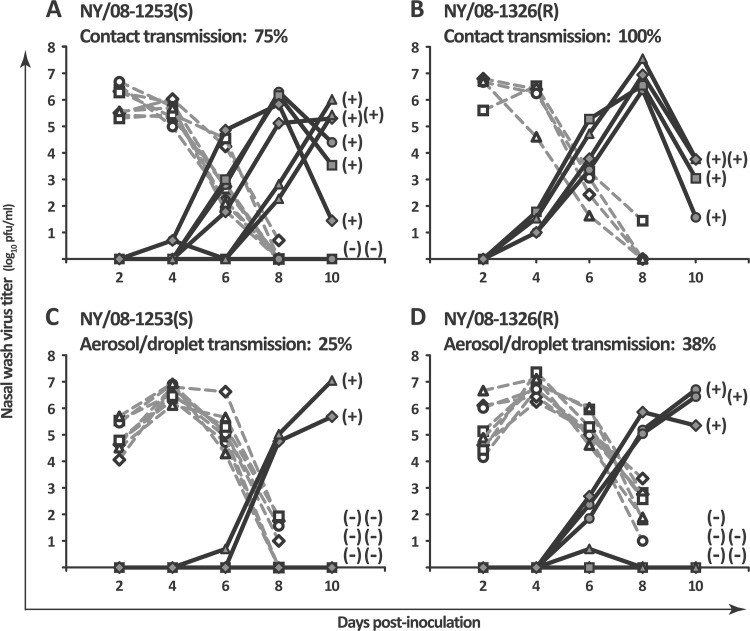

Fig 1.

The oseltamivir-resistant influenza A isolate NY/08-1326(R) was transmitted subtly but consistently more efficiently among guinea pigs than the oseltamivir-sensitive isolate NY/08-1253(S). (A and B) In a contact transmission model, the oseltamivir-sensitive clinical isolate NY/08-1253(S) was transmitted among 75% of guinea pigs (A), while the oseltamivir-resistant clinical isolate NY/08-1326(R) was transmitted among 100% of guinea pigs (B). (C and D) In an aerosol/droplet model at 5°C and 20% relative humidity, NY/08-1253(S) was transmitted among 25% of guinea pigs (C), while NY/08-1326(R) was transmitted among 38% of guinea pigs. Nasal wash virus titers are plotted as a function of day postinoculation. Each dotted line with open symbols represents the nasal wash titers of a virus-inoculated (donor) guinea pig, and each solid line with closed symbols represents the nasal wash titers of a virus-exposed (recipient) guinea pig. Seroconversion status (positive or negative) is shown next to the 10-dpi nasal wash titer of each exposed guinea pig.

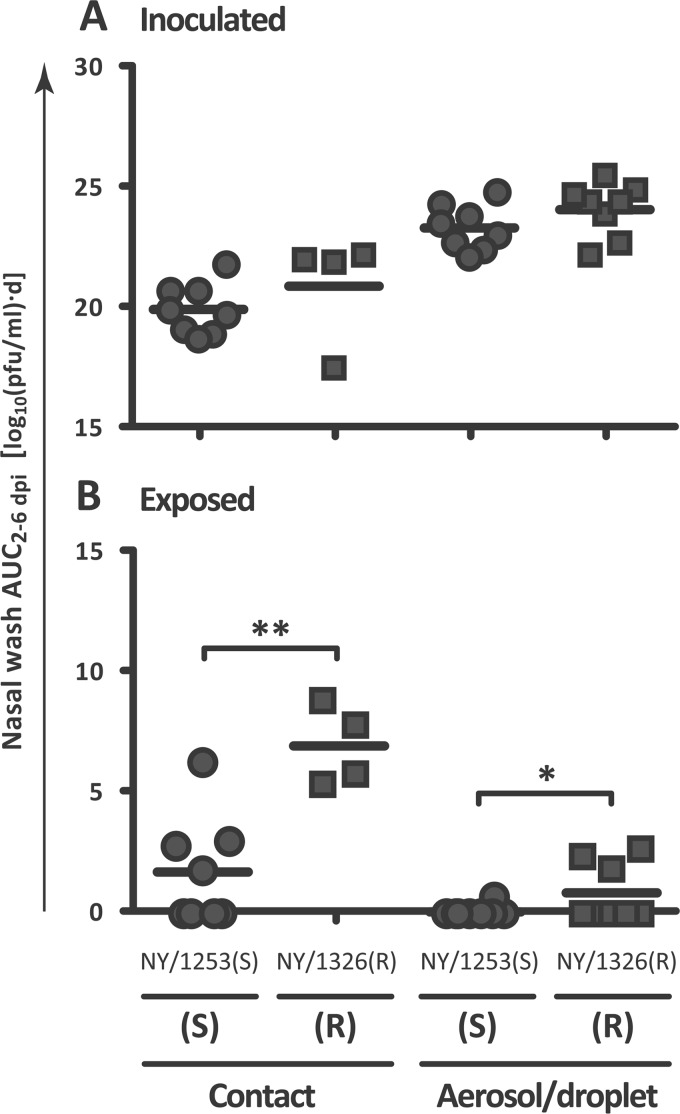

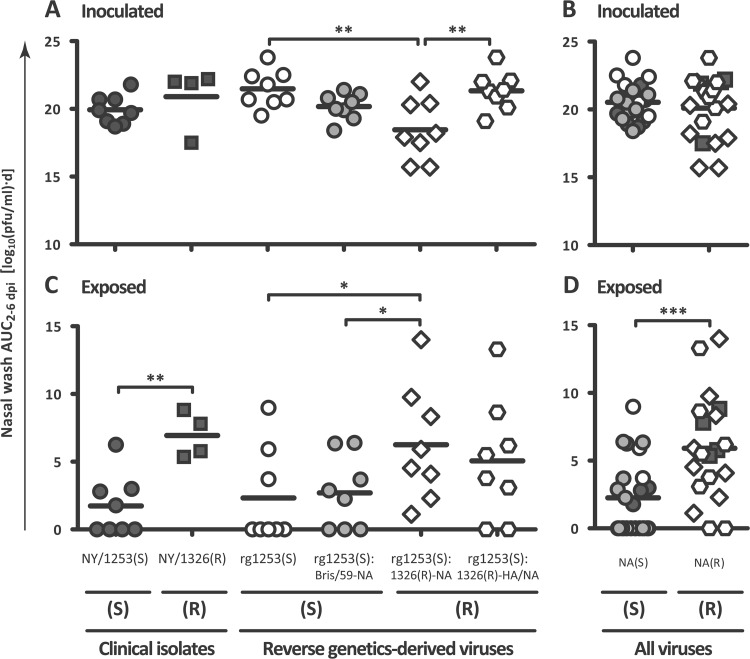

Fig 2.

In both contact and aerosol/droplet models, the oseltamivir-resistant isolate NY/08-1326(R) was transmitted more rapidly among guinea pigs than the oseltamivir-sensitive isolate NY/08-1253(S). The mean AUC2–6 dpi of guinea pigs inoculated with the oseltamivir-sensitive isolate NY/08-1253(S) (circular symbols) and those inoculated with the oseltamivir-resistant isolate NY/08-1326(R) (square symbols) were similar. (B) The mean nasal wash AUC2–6 dpi values for guinea pigs exposed to the sensitive isolate NY/08-1253(S) were significantly lower than the mean nasal wash AUC2–6 dpi values for guinea pigs exposed to the resistant isolate NY/08-1326(R). Horizontal lines denote the mean AUC2–6 dpi. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. S, oseltamivir sensitive; R, oseltamivir resistant.

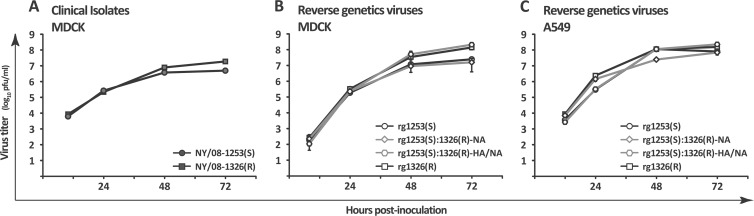

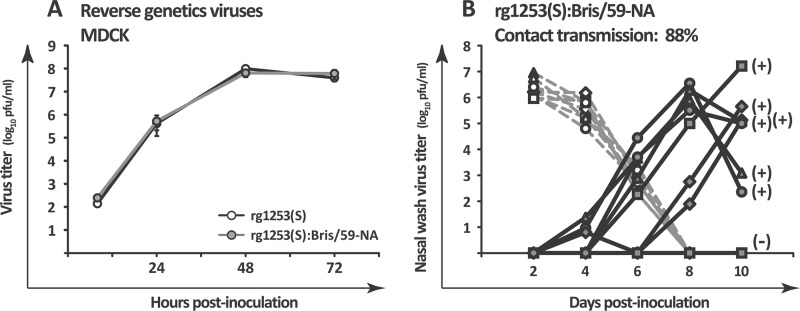

Fig 3.

Clinical isolates and reverse genetics viruses demonstrated similar in vitro growth kinetics. (A) In MDCK cells, the clinical isolates NY/08-1253(S) and NY/08-1326(R) displayed similar growth kinetics, but the oseltamivir-resistant isolate achieved a titer approximately 0.5 log higher by 72 hpi. (B) This growth pattern was reproduced by the reverse genetics clones rg1253(S) and rg1326(R). The 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA attained similar titers as rg1253(S), and the 6:2 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA attained similar titers as rg1326(R). (C) All four reverse genetics clones achieved similar 72-hpi titers in human lung epithelial (A549) cells. Cells were inoculated at an MOI of 0.01 and incubated at 33°C and 5% CO2. Error bars represent 1 SD.

The NA is an integral membrane-bound enzyme that cleaves the terminal sialic acid moieties of the cell surface glycoconjugates to which the viral hemagglutinin (HA) binds, allowing progeny virus to release efficiently from the host cell (39). The HA-NA balance—the “optimal interplay between these receptor-binding and receptor-destroying activities” (50)—is required for efficient virus replication. The receptor-binding activity of the Brisbane/59-like HA may have been better balanced by the receptor-destroying activity of the oseltamivir-resistant NA than by that of the sensitive NA (14, 36, 46, 58). However, the relative fitness and transmissibility of sH1N1 viruses might instead have been modulated by other viral genes. Phylogenetic analysis (56) and stochastic models (12) have suggested that the H275Y substitution could have occurred coincidentally with some other advantageous mutation(s) in the viral genome and simply “hitchhiked” to fixation along with them. To our knowledge, no in vivo data conclusively support either of these hypotheses.

To explain the speed with which resistance to oseltamivir achieved fixation among sH1N1 viruses, we hypothesized that the oseltamivir-resistant NA, independent of changes elsewhere in the genome, provided a fitness advantage to Brisbane/59-like sH1N1 viruses by enhancing their transmission efficiency. We therefore assessed the transmission phenotypes of contemporaneous oseltamivir-sensitive and -resistant sH1N1 clinical isolates and reverse genetics-derived reassortant and point mutant viruses in the guinea pig model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) and human lung epithelial (A549) cells were maintained in minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 100 units/ml of penicillin plus 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (1× P/S). Virus infections were performed in a low-serum medium consisting of Opti-MEM (Gibco) supplemented with 0.3% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.1% FBS, 1× P/S, and 1 μg/ml of tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone-treated trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Oseltamivir-sensitive human influenza virus [A/New York/08-1253/2008(H1N1); “NY/08-1253(S)”] and oseltamivir-resistant virus [A/New York/08-1326/2008(H1N1); “NY/08-1326(R)”] were provided as frozen aliquots from the Wadsworth Center of the New York State Department of Health after initial isolation and one subsequent passage in rhesus monkey kidney cells. Isolates were passaged in MDCK cells two [NY/08-1326(R)] or three [NY/08-1253(S)] more times to derive stocks with sufficient titers for experiments.

To clone the clinical isolates, total RNA was extracted from virus stocks with the QIAamp viral RNA minikit (Qiagen), and viral RNA (vRNA) was amplified by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) using universal influenza A virus primers (21), Transcriptor reverse transcriptase (Roche), and Pfu Ultra high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Stratagene/Agilent). RT-PCR amplicons were cloned into a vRNA expression plasmid, pPol1 (43), by homologous recombination in XL-10 Gold competent cells (Stratagene/Agilent), as previously described (51). As a genetic marker for the recombinant viruses, a BamHI restriction enzyme recognition site was inserted into both pPol1 NA plasmids by using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene/Agilent). A third NA vRNA expression plasmid, pPol1 Bris/59-NA, was similarly created by introducing two amino acid substitutions, S336N and M430L, into pPol1 1253 NA by site-directed mutagenesis. For three plasmids (pPol1 1253 HA, pPol1 1326 HA, and pPol1 1326 PB2), no single clone contained the consensus sequence, and so a consensus clone was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis of a nonconsensus clone. Primer sequences are available upon request. H1N1 numbering of amino acids is used throughout.

Reverse genetics viruses were rescued in a plasmid-based system (17, 38). In brief, eight pPol1-based vRNA expression plasmids carrying genes for the sH1N1 virus segments plus four pCAGGS-based protein expression plasmids carrying genes for the nucleoprotein and polymerase subunits of A/WSN/1933(H1N1) were transfected into 293T cells with Fugene 6 reagent (Roche), and transfectant viruses were amplified by coculture of 293T with MDCK cells. Coculture supernatants were plaque purified, and individual plaque clones were suspended in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 0.3% BSA (PBS+BSA). Reverse genetics virus stocks were grown in low-serum medium by inoculation of MDCK cells with 500 μl of plaque suspension. The sequences of all eight segments of each reverse genetics virus stock were confirmed by amplification of stock vRNA with the SuperScript III one-step RT-PCR system with Platinum Taq High Fidelity (Invitrogen).

In vitro growth kinetics.

MDCK or A549 cells were inoculated in duplicate (clinical isolates) or triplicate (reverse genetics clones) at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. Cells were incubated in low-serum medium at 33°C and 5% CO2 for 72 h postinoculation (hpi). Aliquots of cell supernatants were taken at 8 to 12, 24, 48, and 72 hpi and immediately frozen at −80°C. Virus titers were determined by plaque assay of 10-fold serial dilutions of thawed aliquots on MDCK cells.

Animals.

Five- to six-week-old female Hartley strain guinea pigs weighing 350 to 400 g were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Kingston, NY). Animals were allowed access to food and water ad libitum and kept on a 12-hour light-dark cycle. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Research Council, and the research protocol was approved by the Mount Sinai School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC protocol LA10-00169).

Contact and aerosol/droplet transmission experiments.

Transmission experiments were performed in contact and aerosol/droplet models as previously described (7, 31, 32). Experiments were carried out either under ambient conditions or in environmental chambers (model 6030; Caron); the temperature and relative humidity (RH) conditions under which each experiment was conducted are indicated below in Results. Donor animals were inoculated with 104 PFU of virus suspended in 300 μl of PBS with 0.3% BSA and 1× P/S (PBS+BSA+P/S), instilled intranasally. Nasal wash titers (reported as the log10 PFU/ml) were graphed as a function of the day postinoculation; for simplicity, nasal wash data for the two replicates performed in each transmission model with each virus were combined into a single graph. The area under the nasal wash curve between days 2 and 6 postinoculation (AUC2–6 dpi) was calculated from the nasal wash virus titers of each individual guinea pig, using GraphPad Prism5 software.

Quantification of viral titers in nasal washes and determination of transmission events.

Nasal wash samples were collected from inoculated and exposed animals at 2, 4, 6, and 8 dpi and from exposed animals only at 10 dpi. Nasal washing was performed as previously described (7), and nasal wash samples were frozen in aliquots at −80°C before analysis by plaque assay on MDCK cells at a starting dilution of 1:2. Plaques were visualized by immunostaining (35) with serum from NY/08-1253(S)-infected or NY/08-1326(R)-infected guinea pigs as a primary antibody.

For exposed guinea pigs with a positive nasal wash at the limit of detection (1 PFU per 100 ml of nasal wash recovered), a previously unthawed aliquot of nasal wash was retitrated by plaque assay and a transmission event was confirmed if the repeat titer also remained at or above the limit of detection. For exposed guinea pigs with a single low-positive nasal wash, followed immediately by a negative nasal wash 2 days later (thus yielding a solitary peak in the nasal wash titer curve at ≤1 log10 PFU/ml), the AUC of this isolated peak was not included in AUC analyses. Transmission events were further confirmed by testing for seroconversion in postexposure serum samples collected at ≥18 dpi, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as previously described (42).

Determination of Michaelis-Menten kinetic parameters Km and Vmax.

Enzyme kinetics assays were modified from protocols previously described (16, 23, 44–46). Assays were performed on whole-virus suspensions (16, 46) of virus stocks diluted in 33 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid hydrate (MES; Sigma-Aldrich) with 4 mM calcium chloride, pH 6.5 (MES buffer) (23). Enzymatic activities of the viral NAs were determined with the fluorogenic substrate 2′-(4-methylumbelliferyl)-α-d-N-acetylneuraminic acid (MUNANA; Sigma-Aldrich) (44) in MES buffer.

To normalize input virus, dilutions of virus stocks in a 96-well plate were incubated with 300 μM MUNANA at 37°C for 1 h (45, 46). Dilutions of purified Vibrio cholerae NA (Roche) were included on the same plate to create a standard curve. The reactions were stopped with 140 mM sodium hydroxide in 83% ethanol, and relative fluorescence units (RFU) of catalyzed substrate were measured on a Synergy 4 multimode microplate reader (BioTek) at excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 and 448 nm, respectively (23). For enzyme kinetics assays, virus stocks were diluted in MES buffer to an NA content equivalent to that of 100 μU of V. cholerae NA, as established by the standard curve. Normalized virus suspensions were also titrated by standard hemagglutination assay with 0.5% turkey red blood cells and by plaque assay to determine the virus titer, in hemagglutination units (HAU) and PFU, corresponding to an NA content equivalent to 100 μU of V. cholerae NA. Normalized virus suspensions were combined with 1.67-fold dilutions of MUNANA substrate (from 0 to 300 μM) in 96-well plates in a total volume of 100 μl. Fluorescence was measured on the Synergy 4 multimode microplate reader and recorded every 90 s for 40 min by the Gen5 software (BioTek). Reaction velocity curves were established by plotting time versus RFU, after subtracting background fluorescence in the no-MUNANA wells, using GraphPad Prism5. The linear portions of the velocity curves were determined by linear regression analysis of the data in GraphPad Prism5, and then the mean velocity corresponding to those reads (in RFU/s) was calculated for each MUNANA concentration by using the Gen5 software. Michaelis-Menten parameters Vmax and Km were calculated by plotting MUNANA concentration versus velocity and fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation by nonlinear regression in GraphPad Prism5. Each virus was assayed in three independent experiments, for a total of 5 measurements per virus, with 100 μU of V. cholerae NA included in each 96-well plate as an internal standard. Results are expressed as an average of all replicates ± the standard deviation (SD).

Quantification of oseltamivir resistance.

To derive the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of oseltamivir for the reverse genetics viruses, a MUNANA-based assay was employed, as previously described (23) but with minor modifications. Whole-virus suspensions of diluted virus stocks were combined with 10-fold dilutions of oseltamivir carboxylate (Toronto Research Chemicals, Inc.) in MES buffer at final concentrations of 0 to 10,000 nM. MUNANA was added at a final concentration of 100 μM, and the reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Substrate conversion was stopped with 140 mM sodium hydroxide in 83% ethanol, and RFUs of catalyzed MUNANA substrate were measured by using a microplate reader, as described above. The IC50 for each virus was determined by plotting RFUs, normalized to the fluorescence of no-oseltamivir wells, as a function of the log10 of the oseltamivir concentration. The data were fit to a dose-response curve by nonlinear regression within GraphPad Prism5. Each virus was assayed in two independent experiments, for a total of 5 measurements per virus. Results are expressed as an average of all replicates ± the SD.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical comparisons of the speed of virus clearance (from inoculated guinea pigs) or the speed of transmission (to exposed guinea pigs) were made by either analysis of variance (ANOVA; for multiple groups) or t test (for two groups) applied to the nasal wash titer or AUC2–6 dpi values from those groups. Comparisons among the nasal wash data from multiple groups of guinea pigs were made by one-way ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer posttesting. Comparisons between the nasal wash data from two groups of inoculated guinea pigs or from guinea pigs exposed to viruses with like oseltamivir susceptibility phenotypes were made by a two-tailed t test. Comparisons between the nasal wash data from guinea pigs exposed to viruses with different oseltamivir susceptibility phenotypes were made with a one-tailed t test. Statistical comparisons of the frequency of transmission events were assessed by using Fisher's exact test. All statistical calculations were performed in GraphPad Prism5.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Consensus sequences of the 16 vRNA segments of the clinical isolates have been deposited in GenBank (accession numbers JN582051 through JN582066).

RESULTS

Oseltamivir-sensitive and -resistant clinical isolates NY/08-1253(S) and NY/08-1326(R) demonstrate subtly dissimilar transmission phenotypes in guinea pigs.

The human influenza viruses A/New York/08-1253/2008(H1N1) [NY/08-1253(S)], encoding NA-H275, and A/New York/08-1326/2008(H1N1) [NY/08-1326(R)], encoding NA-H275Y, were both isolated in New York State in February 2008. Transmission experiments with the clinical isolates were performed using both contact and aerosol/droplet transmission models (Fig. 1).

Contact transmission experiments were performed in eight pairs of guinea pigs for NY/08-1253(S) and four pairs of guinea pigs for NY/08-1326(R), under ambient environmental conditions, between February and April 2009. In keeping with the conventions of the field, we use the term “contact” to describe the cocaging of inoculated and exposed experimental animals; however, all modes of transmission, by direct or indirect transfer of respiratory secretions or droplet sprays onto mucous membranes, or by inhalation of airborne droplets or droplet nuclei into the respiratory tract, are possible in this model, and the relative contribution of each mode to virus transmission overall cannot be determined. In the contact model, the oseltamivir-sensitive isolate NY/08-1253(S) was transmitted among 75% (6 of 8 pairs) of the guinea pigs, with transmission events occurring by 4 to 8 dpi (Fig. 1A), and the resistant isolate NY/08-1326(R) was transmitted among 100% (4 of 4 pairs) of guinea pigs, with all four transmission events occurring by 4 dpi (Fig. 1B).

Aerosol/droplet experiments were conducted in eight pairs of guinea pigs for each clinical isolate in environmental chambers set at 5°C and 20% RH between March and May 2009. In this model, contact between animals is precluded, and thus transmission must occur by airborne respiratory droplets or droplet nuclei. In the aerosol/droplet model, the sensitive isolate NY/08-1253(S) was transmitted among 25% (2 of 8 pairs) of guinea pigs, with transmission events occurring by 6 and 8 dpi (Fig. 1C), and the resistant isolate NY/08-1326(R) was transmitted among 38% (3 of 8 pairs) of guinea pigs, with all three transmission events occurring by 6 dpi (Fig. 1D). A fourth guinea pig exposed to NY/08-1326(R) had viable virus in her nasal wash at 6 dpi (Fig. 1D, solid lines with closed triangles), but she did not demonstrate persistent nasopharyngeal viral replication and did not seroconvert; this animal was not counted as a transmission event.

The AUC2–6 dpi quantifies the duration of peak virus shedding from inoculated guinea pigs. In these experiments, the mean nasal wash AUC2–6 dpi was not significantly different between oseltamivir-sensitive and -resistant isolates in either the contact model (P = 0.33) or the aerosol/droplet model (P = 0.16) (Fig. 2A). Under ambient environmental conditions, peak nasal wash titers in inoculated animals occurred between 2 and 4 dpi; however, at 5°C, nasal wash titers peaked later, and viral clearance was slower in inoculated animals, consistent with previous transmission experiments at low temperatures (31, 42).

To minimize stress on the guinea pigs, nasal washes in experiments such as these are performed every other day; thus, the exact day on which a transmission event occurs cannot be pinpointed. However, the nasal wash AUC2–6 dpi of exposed guinea pigs quantitatively estimates the rapidity with which transmission events occur. Faster transmission corresponds with higher early nasal wash titers and thus higher AUC2–6 dpi values. Consistent with more rapid transmission, the mean nasal wash AUC2–6 dpi of guinea pigs exposed to the oseltamivir-resistant virus NY/08-1326(R) was significantly higher than that of guinea pigs exposed to the oseltamivir-sensitive virus NY/08-1253(S) in both contact (P = 0.0011) and aerosol/droplet (P = 0.049) models (Fig. 2B).

Thus, the clinical isolates displayed similar growth kinetics in the nasopharynges of inoculated guinea pigs; however, in both contact and aerosol/droplet models, the oseltamivir-resistant virus NY/08-1326(R) transmitted subtly but consistently earlier and more often than did the sensitive isolate NY/08-1253(S), with faster transmission (as measured by the AUC2–6 dpi) achieving statistical significance. Therefore, to characterize these clinical isolates further and identify which viral gene(s) was influencing these transmission phenotypes, we cloned them into a reverse genetics system.

Oseltamivir-sensitive and -resistant clinical isolates NY/08-1253(S) and NY/08-1326(R) are highly synonymous at the amino acid level.

Three to seven plasmid clones of each vRNA segment were fully sequenced to establish a consensus. The clinical isolates differed at only 22 of 4,522 residues, for an overall sequence identity of 99.51% at the amino acid level (Table 1). Therefore, we first rescued four reverse genetics viruses: rg1253(S), a recombinant clone of NY/08-1253(S); rg1326(R), a recombinant clone of NY/08-1326(R); rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA, a 7:1 reassortant that encodes only the NA from NY/08-1326(R) in the backbone of NY/08-1253(S); and rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA, a 6:2 reassortant that expresses the HA and NA from NY/08-1326(R) and the six internal genes from NY/08-1253(S).

Table 1.

Summary of amino acid differences among the viruses assessed in these experiments in comparison to the reference strain, A/Brisbane/59/2007(H1N1)

| Strain | Viral protein and amino acid positiona |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NS1 |

M2 |

NA |

NP |

HA |

PA |

PB1 |

PB1-F2b |

PB2 |

||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | 111 | 88 | 275 | 336 | 354 | 430 | 357 | 433 | 176 | 202 | 203 | 206 | 358 | 353 | 336 | 642 | 6 | 30 | 41 | 109 | 157 | 286 | 340 | 411 | 453 | |

| A/Brisbane/59/2007(H1N1)c | A | V | D | H | N | D | L | K | T | N | G | N | A | T | R | I | N | D | L | H | I | K | S | R | V | P |

| rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA | V | V | G | H | N | D | L | R | T | S | G | D | A | I | K | V | N | G | L | H | V | K | S | K | V | P |

| A/NY/08-1253(S)/2008(H1N1) | V | V | G | H | S | D | M | R | T | S | G | D | A | I | K | V | N | G | L | H | V | K | S | K | V | P |

| rg1253(S) | V | V | G | H | S | D | M | R | T | S | G | D | A | I | K | V | N | G | L | H | V | K | S | K | V | P |

| rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA | V | V | G | Y | N | G | L | R | T | S | G | D | A | I | K | V | N | G | L | H | V | K | S | K | V | P |

| rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA | V | V | G | Y | N | G | L | R | T | N | V | N | T | T | K | V | N | G | L | H | V | K | S | K | V | P |

| A/NY/08-1326(R)/2008(H1N1) | V | M | D | Y | N | G | L | K | I | N | V | N | T | T | K | V | S | G | R | P | I | N | G | R | I | S |

| rg1326(R) | V | M | D | Y | N | G | L | K | I | N | V | N | T | T | K | V | S | G | R | P | I | N | G | R | I | S |

No amino acid differences were found in the NEP and M1 proteins. Amino acids shown in boldface indicate residues that differ from the reference strain, A/Brisbane/59/2007(H1N1).

These viruses encode a truncated PB1-F2 protein (57 amino acids).

Reverse genetics-derived virus clones and reassortants demonstrate in vitro growth kinetics similar to the clinical isolates.

Multicycle growth curves were performed in MDCK (Fig. 3A and B) and A549 (Fig. 3C) cells with the clinical isolates (Fig. 3A) and the reverse genetics viruses (Fig. 3B and C). Growth curves were determined at 33°C, which is representative of the temperature of the human nasopharynx (30). In MDCK cells, viruses expressing the HA encoded by the resistant virus (the clinical isolate NY/08-1326(R), its reverse genetics clone rg1326(R), and the 6:2 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA) achieved titers 0.5 to 1 log higher than those expressing the HA of the sensitive virus — NY/08-1253(S), its reverse genetics clone rg1253(S), and the 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA (Fig. 3A and B). However, in A549 cells, all reverse genetics viruses attained similar 72-h titers (Fig. 3C). Thus, the clinical isolates and their reverse genetics clones displayed similar multicycle growth kinetics in MDCK cells, but the HA-dependent growth phenotype observed in canine cells was not recapitulated in a human lung cell line.

Reverse genetics viruses encoding the oseltamivir-resistant NA are transmitted more efficiently among guinea pigs than is the oseltamivir-sensitive virus.

Because aerosol/droplet transmission was relatively inefficient with these viruses, experiments with the reverse genetics viruses were performed in the contact model, in which transmission can occur via direct and indirect contact, droplet spray, and/or short-range airborne respiratory droplets or aerosols. All experiments were conducted between January and May 2011 in environmental chambers set at 20°C and 20% RH, in order to standardize the replicates (Fig. 4).

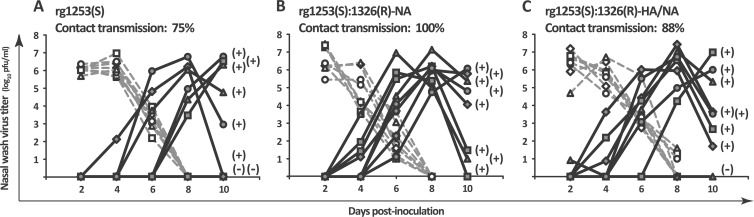

Fig 4.

Reverse genetics reassortants expressing the oseltamivir-resistant NA were transmitted more efficiently among guinea pigs than the oseltamivir-sensitive reverse genetics clone rg1253(S). (A) The oseltamivir-sensitive reverse genetics clone rg1253(S) was transmitted among 75% (6 of 8 pairs) of guinea pigs. (B) The 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA was transmitted among 100% (8 of 8 pairs) of guinea pigs. (C) The 6:2 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA was transmitted among 88% (7 of 8 pairs) of guinea pigs. Nasal wash virus titers are plotted as a function of day postinoculation. Each dotted line with open symbols represents the nasal wash titers of a virus-inoculated (donor) guinea pig, and each solid line with closed symbols represents the nasal wash titers of a virus-exposed (recipient) guinea pig. Seroconversion status (positive or negative) is shown next to the 10-dpi nasal wash titer of each exposed guinea pig.

The oseltamivir-sensitive reverse genetics clone rg1253(S) was transmitted among 75% (6 of 8 pairs) of guinea pigs, with transmission events occurring by days 4 (n = 1), 6 (n = 2), and 8 (n = 3) postinoculation (Fig. 4A). This transmission phenotype was similar to that of the clinical isolate NY/08-1253(S), which was also transmitted among 75% of guinea pigs in the contact model, with transmission events occurring by days 4 (n = 1), 6 (n = 3), and 8 (n = 2) postinoculation (Fig. 1A). In contrast, the 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA was transmitted among 100% (8 of 8 pairs) of guinea pigs, with transmission events occurring by days 4 (n = 4) and 6 (n = 4) postinoculation (Fig. 4B), and the 6:2 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA was transmitted among 88% (7 of 8 pairs) of guinea pigs, with transmission events occurring by days 4 (n = 3), 6 (n = 3), and 8 (n = 1) postinoculation (Fig. 4C). One guinea pig inoculated with the 6:2 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA demonstrated an atypical virus shedding pattern (Fig. 3C, dotted lines with open triangles); of note, this guinea pig was the only donor inoculated with either reassortant that failed to transmit virus to her cagemate during the exposure period. All transmission events identified by plaque assay of nasal washes were subsequently confirmed by postexposure seroconversion (Fig. 4).

The reverse genetics reassortant rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA is transmitted similarly to clinical isolate NY/08-1253(S) and reverse genetics clone rg1253(S).

Four amino acid differences distinguished the oseltamivir-sensitive NA of NY/08-1253(S) from the oseltamivir-resistant NA encoded by NY/08-1326(R). One change, H275Y, is the resistance mutation itself, while another, D354G, was consistently found in association with H275Y among Brisbane/59-like viruses (9, 36, 46, 56). The other two substitutions, S336 and M430 in NY/08-1253(S), versus N336 and L430 in NY/08-1326(R), were of unknown significance. To rule out an effect of either S336 or M430 on the transmission phenotype, we rescued a fifth virus, rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA, which expressed the oseltamivir-sensitive NA of the reference strain A/Brisbane/59/2007 in the backbone of NY/08-1253(S). As such, it differed from the oseltamivir-sensitive clone rg1253(S) by two point mutations (S336N and M430L) and from the oseltamivir-resistant 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA by the two companion substitutions typical of oseltamivir-resistant Brisbane/59-like sH1N1 viruses (H275Y and D354G) (Table 1).

In MDCK cells, the multicycle growth kinetics of the two oseltamivir-sensitive reverse genetics viruses, rg1253(S) and rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA, were not measurably different (Fig. 5A). We then assessed the transmission phenotype of the point mutant rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA in the contact transmission model. Experiments were conducted in eight pairs of guinea pigs in March 2012, in environmental chambers set at 20°C and 20% RH, identical to the conditions under which the three other reverse genetics viruses were evaluated.

Fig 5.

The oseltamivir-sensitive reverse genetics viruses rg1253(S) and rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA grew similarly in vitro and were transmitted similarly in vivo. (A) The reverse genetics viruses rg1253(S) and rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA, which differ by two residues in the viral NA (S336N and M430L), displayed comparable growth kinetics in MDCK cells. Cells were inoculated at an MOI of 0.01 and incubated at 33°C and 5% CO2. Error bars represent 1 SD. (B) The 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA was transmitted among 88% (7 of 8 pairs) of guinea pigs. Nasal wash virus titers are plotted as a function of day postinoculation. Each dotted line with open symbols represents the nasal wash titers of a virus-inoculated (donor) guinea pig, and each solid line with closed symbols represents the nasal wash titers of a virus-exposed (recipient) guinea pig. Seroconversion status (positive or negative) is shown next to the 10-dpi nasal wash titer of each exposed guinea pig.

The oseltamivir-sensitive reverse genetics clone rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA was transmitted among 88% (7 of 8 pairs) of guinea pigs, with transmission events occurring by days 4 (n = 2), 6 (n = 3), and 8 (n = 2) postinoculation (Fig. 5B). This transmission phenotype was similar to that of the wild-type clinical isolate NY/08-1253(S), which transmitted among 75% of guinea pigs, with transmission events occurring by days 4 (n = 1), 6 (n = 3), and 8 (n = 2) postinoculation (Fig. 1A), and to that of the reverse genetics clone rg1253(S), which was transmitted among 75% (6 of 8 pairs) of guinea pigs, with transmission events occurring by days 4 (n = 1), 6 (n = 2), and 8 (n = 3) postinoculation (Fig. 4A).

Viruses encoding the oseltamivir-resistant NA are transmitted significantly more rapidly among guinea pigs than are oseltamivir-sensitive viruses.

The mean AUC2–6 dpi of guinea pigs exposed to the oseltamivir-resistant clinical isolate NY/08-1326(R) was significantly higher, consistent with more rapid transmission, than that of guinea pigs exposed to the oseltamivir-sensitive clinical isolate NY/08-1253(S) (P = 0.0011) (Fig. 6C). Similarly, the mean AUC2–6 dpi of guinea pigs exposed to the oseltamivir-resistant 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA was significantly higher than that of guinea pigs exposed to the oseltamivir-sensitive reverse genetics viruses rg1253(S) (P = 0.032) and rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA (P = 0.032). There was also a trend toward more rapid transmission of the oseltamivir-resistant 6:2 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA. The mean AUC2–6 dpi of guinea pigs exposed to the resistant 6:2 reassortant was higher than that of guinea pigs exposed to the sensitive reverse genetics viruses rg1253(S) (P = 0.097) and rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA (P = 0.11); these differences approached but did not reach statistical significance.

Fig 6.

Viruses encoding the oseltamivir-resistant NA were transmitted more rapidly than viruses encoding the oseltamivir-sensitive NA. (A) The mean AUC2–6 dpi of guinea pigs inoculated with clinical isolates (dark gray symbols) and reverse genetics viruses (white or light gray symbols) were generally similar, with the exception of rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA, which was cleared significantly faster than either rg1253(S) or rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA. (B) The mean nasal wash AUC2–6 dpi of guinea pigs inoculated with viruses expressing the sensitive NA (circular symbols) was similar to that of animals inoculated with viruses expressing the resistant NA (square, diamond, and hexagon symbols). (C) The mean nasal wash AUC2–6 dpi values for guinea pigs exposed to NY/08-1253(S) was significantly lower than that of guinea pigs exposed to NY/08-1326(R), and the mean nasal wash AUC2–6 dpi values for guinea pigs exposed to rg1253(S) or rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA were significantly lower than that of guinea pigs exposed to rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA. (D) Transmission events in guinea pigs exposed to viruses expressing the sensitive NA occurred significantly more slowly, as measured by the AUC2–6 dpi, than did transmission events in those exposed to viruses expressing the resistant NA. Horizontal lines denote the mean AUC2–6 dpi. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. S, oseltamivir sensitive; R, oseltamivir resistant.

Differences in virus shedding from inoculated donor guinea pigs did not appear to influence speed of transmission to exposed recipient guinea pigs. Nasal wash titers at 2 dpi were not significantly different among guinea pigs inoculated with any of the six reverse genetics viruses (P = 0.27); however, nasopharyngeal titers of the oseltamivir-resistant 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA had fallen significantly farther, compared to the other 5 viruses, by 4 and 6 dpi (P = 0.026 and P = 0.018, respectively). Consistent with faster viral clearance, guinea pigs inoculated with the 7:1 reassortant also had significantly lower mean AUC2–6 dpi values than did guinea pigs inoculated with either rg1253(S) or rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA (P = 0.0051 by ANOVA) (Fig. 6A). Collectively, these data indicate that a greater magnitude and duration of virus shedding from inoculated guinea pigs did not correlate with faster transmission to exposed guinea pigs, as measured by the mean AUC2–6 dpi.

There was also no measurable difference in speed of transmission among viruses of like oseltamivir susceptibility phenotype. The three oseltamivir-sensitive viruses [the clinical isolate NY/08-1253(S), its reverse genetics clone rg1253(S), and the reassortant rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA] had comparable mean AUC2–6 dpi values (P = 0.79), as did the three oseltamivir-resistant viruses [the clinical isolate NY/08-1326(R), the 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA, and the 6:2 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA; P = 0.72]. Therefore, the infection and transmission phenotypes of all viruses were compared by pooling their AUC2–6 dpi values according to the NA that they expressed (Fig. 6B and D). The course of infection, as measured by the AUC2–6 dpi, in guinea pigs inoculated with the three viruses expressing the sensitive NA was similar to that of animals inoculated with viruses expressing the resistant NA (P = 0.44) (Fig. 6B). However, transmission events in animals exposed to viruses expressing the sensitive NA occurred more slowly, as reflected by significantly lower AUC2–6 dpi values, than did those in animals exposed to viruses expressing the resistant NA (P = 0.0004) (Fig. 6D).

The pooled contact transmission rate for the three oseltamivir-resistant viruses, NY/08-1326(R), rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA, and rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA, was 95% (19 transmission events among 20 guinea pig pairs). For the oseltamivir-sensitive viruses, NY/08-1253(S), rg1253(S), and rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA, the pooled contact transmission rate was 79% (19 transmission events among 24 guinea pig pairs), for a relative transmission frequency of 83% (95% confidence interval, 66 to 100%), which was narrowly nonsignificant.

Thus, as with the clinical isolates, the oseltamivir-sensitive reverse genetics viruses were transmitted significantly more slowly than their oseltamivir-resistant comparators, with a nonsignificant but consistent trend toward less frequent transmission as well. Coexpression of the HA and NA of NY/08-1326(R) did not improve transmissibility relative to expression the oseltamivir-resistant NA alone, nor did reversion of two nonconsensus residues in the NA of NY/08-1253(S) back to those in the NA of the reference strain Brisbane/59. These data suggest that the oseltamivir-resistant Brisbane/59-like NA (specifically, the NA residues H275Y with or without D354G) is sufficient to enhance transmission efficiency in the guinea pig model.

The oseltamivir-resistant NA demonstrated reduced affinity for the NA substrate analog MUNANA and for the NA inhibitor oseltamivir.

To place these isolates in the context of what is known about the enzymatic activity of oseltamivir-sensitive and -resistant Brisbane/59-like sH1N1 NAs, we performed MUNANA-based assays on the reverse genetics viruses to derive the Michaelis-Menten parameters Vmax and Km and the IC50 for oseltamivir (Table 2).

Table 2.

Enzymatic properties of the neuraminidases expressed by reverse genetics viruses

| Reverse genetics virus | NA sensitivity | Normalized titera |

Michaelis-Menten kinetics |

Oseltamivir inhibition |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFU | HAU | Km ± SD (μM) | Km relative to rg1253(S) | Vmax ± SD (RFU/s)b | Vmax relative to rg1253(S) | IC50 ± SD (nM) | IC50 relative to rg1253(S) | ||

| rg1253(S) | S | 106.0 | 32 | 22.7 ± 3.0 | 1 | 4.26 ± 0.15 | 1 | 1.46 ± 0.19 | 1 |

| rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA | S | 105.9 | 32 | 22.4 ± 4.0 | 0.99 | 4.60 ± 0.23 | 1.08 | 1.45 ± 0.17 | 0.99 |

| rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA | R | 106.0 | 32 | 41.6 ± 5.3 | 1.84 | 4.80 ± 0.20 | 1.13 | 518 ± 106 | 354 |

| rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA | R | 106.7 | 32 | 42.1 ± 8.0 | 1.86 | 4.33 ± 0.27 | 1.02 | 548 ± 50 | 375 |

| rg1326(R) | R | 106.6 | 32 | 40.7 ± 5.1 | 1.79 | 4.62 ± 0.19 | 1.08 | 577 ± 31 | 395 |

Whole-virus suspensions were normalized to an NA content equivalent to 100 μU of purified V. cholerae NA.

The maximum catalytic velocity (Vmax) is expressed in arbitrary units of relative fluorescence units per second.

As expected, the experimentally derived parameters for all three viruses expressing the resistant NA—rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA, rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA, and rg1326(R)—were similar, as were those for the two viruses expressing a sensitive NA, rg1253(S) and rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA. The Km values derived for the resistant NAs were approximately double those of the sensitive NAs, indicating that the resistant NA exhibits a weaker affinity for the MUNANA substrate. Similarly, the measured IC50 was 350- to 400-fold greater for the viruses expressing the resistant NA, reflecting weaker affinity for oseltamivir as well. However, the Vmax remained comparable among all NAs, representing preserved enzymatic activity despite the NA-H275Y and D354G substitutions. Virus dilutions normalized for equivalent NA content (100 μU of V. cholerae NA) had similar HAU titers, consistent with similar HA-to-NA expression ratios; however, surface HA and NA expression cannot be quantified precisely without virus-specific anti-HA and anti-NA antibodies, which do not exist for these viruses. The NA enzymatic functions of these two Brisbane/59-like viruses were all consistent with previous data obtained with contemporaneous sH1N1 isolates (9, 46, 56).

DISCUSSION

The guinea pig transmission experiments presented here support the hypothesis that the worldwide spread of oseltamivir-resistant Brisbane/59-like sH1N1 influenza viruses resulted from enhanced mammalian transmissibility attributable to the oseltamivir-resistant NA. In these experiments, we have demonstrated that an oseltamivir-sensitive Brisbane/59-like clinical isolate, NY/08-1253(S), was transmitted among guinea pigs significantly more slowly than an oseltamivir-resistant isolate, NY/08-1326(R), in both contact and aerosol/droplet models. Through reverse genetics reassortants and point mutants, we have determined that the NA substitutions H275Y, D354G, or a combination of the two are sufficient to confer the enhanced transmission efficiency demonstrated by the oseltamivir-resistant clinical isolate NY/08-1326(R) in the guinea pig model.

In the decade prior to the emergence of 2009 pandemic H1N1 (H1N1pdm09) viruses, sH1N1 viruses clustered into four antigenic clades, three of which are represented by former vaccine strains: the A/New Caledonia/20/1999-like clade 1; the A/Solomon Islands/3/2006-like clade 2A; the Brisbane/59-like clade 2B; the nonvaccine strain A/St. Petersburg/10/2007-like clade 2C (36). As the Solomon Islands-like (clade 2A) HA accumulated the drift mutations characteristic of the antigenically novel Brisbane/59-like (clade 2B) HA, the contemporaneous NA was simultaneously acquiring the permissive mutations (such as V234M, R222Q, and D344N) that have been proposed to temper the previously deleterious effects of the NA-H275Y mutation (5, 14, 36). However, through 2007 and 2008, Brisbane/59-like viruses continued to evolve, eventually separating into early (clade 2B-1) and late (clade 2B-2) viruses, which are distinguished by 8 characteristic amino acid substitutions in 5 viral proteins: NA (H275Y and D354G), HA (A206T), PB1 (N642S), PB1-F2 (L30R and H41P), and PB2 (V411I and P453S) (56). The clinical isolate NY/1253(S) encodes the 8 characteristic clade 2B-1 residues, while NY/1326(R) encodes the 8 substitutions that typify clade 2B-2.

Both HA-NA balance and genetic “hitchhiking” have been proposed as evolutionary mechanisms that would explain the rapid surge in prevalence undergone by oseltamivir-resistant Brisbane/59-like sH1N1 viruses. The “hitchhiking” hypothesis posits that the H275Y substitution arose coincidentally with some other advantageous mutation(s) in the viral genome; thus, the H275Y mutation did not necessarily confer a fitness advantage upon sH1N1 viruses, but rather became dominant by assorting with another gene(s) that did (12, 56). Our data suggest that the oseltamivir-resistant NA (inclusive of both H275Y and D354G substitutions) accounts for most, if not all, of the enhancement in transmission efficiency seen in these oseltamivir-resistant Brisbane/59-like viruses. There was no measurable difference between the reverse genetics 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA (derived from seven clade 2B-1-like segments) and the clinical isolate NY/08-1326(R) (entirely clade 2B-2-like) in terms of transmission frequency and speed. Our data cannot determine whether NA-D354G alone is an advantageous mutation, with which H275Y hitchhiked to prevalence; however, our experiments are consistent with the hypothesis that the oseltamivir-resistant clade 2B-2 NA (which is characterized by the H275Y and D354G substitutions together) did not need to hitchhike along with advantageous mutations in other genes, but rather conferred a transmission advantage by itself.

According to the HA-NA balance hypothesis, an H275Y-encoding NA, which has reduced affinity for its sialic acid substrate compared to NA-H275, may have provided a better functional match for the receptor-binding activity of the contemporaneous HA (14, 36, 46, 58). Typical of oseltamivir-sensitive clade 2B-1 viruses like Brisbane/59, the receptor binding domain of the NY/08-1253(S) HA encodes the residue A206, while that of the NY/08-1326(R) HA encodes A206T, similar to A/England/557/2007 and other clade 2B-2 viruses (14, 56). With the 6:2 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA, we have demonstrated that viruses with either the HA of NY/08-1253(S) (clade 2B-1) or that of NY/08-1326(R) (clade 2B-2) appear to transmit equally efficiently in the guinea pig model. Although there was one fewer transmission event with the 6:2 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-HA/NA compared to the 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA (88% versus 100%, respectively), abnormal virus shedding from one inoculated guinea pig likely affected transmission in that single pair. Regardless, the speed of transmission was not quantifiably different between the 7:1 and 6:2 reassortants. Our experiments indicate that, in guinea pigs, HA evolution between NY/08-1253(S) (clade 2B-1) and NY/08-1326(R) (clade 2B-2) seems not to have provided a measurable transmission advantage that might have encouraged selection of the oseltamivir-resistant NA.

To attribute enhanced transmissibility solely to the NA substitutions H275Y and/or D354G, we created the reverse genetics reassortant rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA. The oseltamivir-sensitive NA of NY/08-1253(S) contains two unique residues, S336 and M430, unlike the N336 and L430 residues found in most Brisbane/59-like NAs. The oseltamivir-sensitive 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA expresses the oseltamivir-sensitive NA of the reference strain Brisbane/59, including the consensus residues N336 and L430. It differs from the oseltamivir-sensitive clone rg1253(S) by two residues (S336N and M430L) and from the oseltamivir-resistant 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA by two residues (H275Y and D354G). The relatively slow transmission observed with rg1253(S) was also characteristic of the reassortant rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA, and their enzymatic parameters Km and Vmax and the oseltamivir IC50 were statistically indistinguishable. These data suggest that the N1 residues S/N-336 and M/L-430 affect neither NA enzymatic function nor speed of transmission in the guinea pig model. However, the oseltamivir-resistant 7:1 reassortant rg1253(S):1326(R)-NA was transmitted among guinea pigs significantly faster than either rg1253(S) or rg1253(S):Bris/59-NA, implicating the clade 2B-2-like substitutions H275Y and/or D354G in the relatively rapid transmission of oseltamivir-resistant Brisbane/59-like viruses in this model.

The H275Y substitution mediates oseltamivir resistance by altering the position of the catalytic residue glutamic acid (E)-276, which in turn reduces the affinity with which oseltamivir binds into the enzyme's active site (15). The D354G substitution was consistently found in association with H275Y among clade 2B-2 Brisbane/59-like viruses, appearing to have coevolved with it (9, 36, 46, 56). Interestingly, G354 was also characteristic of the NAs of A/New Caledonia/20/1999 (clade 1) and A/Solomon Islands/3/2006 (clade 2A), as well as later Brisbane/59-like clade 2B-2 oseltamivir-resistant NAs (36, 46, 56). Residue 354 is located on the opposite side of the NA monomer from the active site, at a physical remove from H275Y (46), and it does not appear to affect NA substrate affinity or catalytic activity (9, 46). Our experiments cannot yet distinguish whether NA-H275Y or -D354G (or both together) is responsible for the enhanced mammalian transmission efficiency of oseltamivir-resistant sH1N1 viruses in our model. However, from an evolutionary standpoint, the two mutations together are characteristic of the clade 2B-2 oseltamivir-resistant NA that achieved fixation (14, 36, 56, 58). Even without disentangling the individual effects of H275Y and D354G, our data support the hypothesis that the exponential increase in oseltamivir resistance observed among sH1N1 viruses between 2007 and 2009 can be explained by enhanced mammalian transmissibility of viruses encoding the oseltamivir-resistant NA.

Even incremental enhancements in transmission efficiency, such as those we have shown here in the guinea pig model, can result in dramatic increases in strain prevalence on a population level. Our data are consistent with, but do not discriminate between, stochastic models demonstrating that the rapid strain replacement observed among sH1N1 viruses can occur whether the resistance mutation itself (i.e., H275Y) provides a small transmission advantage or whether it arises coincidentally with a second mutation that confers a transmission advantage of similar magnitude (12). Improved mammalian transmissibility can also explain the emergence and persistence of oseltamivir-resistant sH1N1 viruses, even in the absence of widespread oseltamivir use. Prescription data from Europe, where resistant sH1N1 viruses first appeared, indicate that oseltamivir was not in wide use at the time (28, 36, 52); therefore, the majority of circulating Brisbane/59-like influenza virus strains were never exposed to oseltamivir and would have derived no selective advantage from decreased susceptibility to it. Our experiments support the notion that the oseltamivir-resistant phenotype is merely a coincidence, a by-product of NA evolution that, more importantly, subtly but measurably enhances viral fitness even in hosts not taking oseltamivir (14).

Mammalian transmission of influenza viruses is studied mainly in two animal models, the ferret and the guinea pig. Both are susceptible to infection by unadapted human influenza virus isolates and, like humans, they manifest a primarily upper respiratory tract infection and transmit virus to others of their species in both contact and noncontact models (6). Ferrets exhibit signs of influenza virus infection, such as anorexia, weight loss, lethargy, fever, sneezing, and rhinorrhea (33). Commercially available outbred Hartley guinea pigs, in contrast, display minimal to no signs of illness (6). However, a significant proportion of experimental human influenza virus infections are also asymptomatic (8, 22), and insufficient data exist to determine the extent to which human transmission of influenza viruses occurs in the absence of overt disease (40). While ferrets are the only mammal known to model both pathogenesis and efficient transmission of influenza viruses, the guinea pig model has the distinct advantages of lower costs and greater availability, enabling the performance of sufficient replicates to demonstrate statistically significant differences in transmission efficiency among viruses (13, 47–49). Ferret studies are often performed with 2 to 4 transmission pairs per virus or condition (3, 16, 18, 24, 26, 29, 34, 37, 41). For most researchers, the ferret is a cost-prohibitive model in which to confirm that the differences observed in a few animals are not simply a matter of chance. The guinea pig model is thus ideal for assessing viruses such as these, whose transmissibility is expected, a priori, to differ only slightly.

However, it is important also to note that guinea pigs and ferrets alike are models for human influenza, neither of which may independently or completely recapitulate the spectrum of influenza disease or virus spread among humans. In a recently published human challenge-transmission study (27), conceptually similar to transmission experiments performed in animal models, human “donors” were intranasally inoculated with influenza A/Wisconsin/67/2005(H3N2) and cohoused with naïve human “recipients,” with whom they took part in exposure events (such as watching television, playing games, and eating meals) for 30 h over 2 days. Only 7 of the 9 intranasally inoculated donors became infected; of those 7, only 4 developed symptoms consistent with an influenza-like illness and just one mounted a fever. Under experimental conditions in a small number of subjects, the human response to influenza virus inoculation ranged from symptomatic (like ferrets) to asymptomatic (like guinea pigs). Even in a cohousing scenario akin to a “contact” transmission model (although of shorter duration), the adjusted secondary attack rate among exposed human recipients was only 25%. In an aerosol/droplet transmission model among guinea pigs, we observed 25% and 38% transmission rates for NY/08-1253(S) and NY/08-1326(R), respectively, which paralleled the trends seen in the contact model. We assessed reverse genetics clones and reassortants exclusively in the contact model, maximizing our power to detect a statistically significant difference between oseltamivir-sensitive and -resistant viruses with the fewest animals possible. An aerosol/droplet transmission model, which both increases the physical distance between animals and precludes direct and indirect contact, clearly poses a more stringent transmission challenge. However, it may not a be a challenge that is more accurately reflective of influenza virus transmission in humans, among whom “the relative contribution of contact, droplet or airborne transmission of influenza viruses… remains unknown” (4).

In conclusion, expression of an oseltamivir-resistant NA in the context of other viral proteins from a Brisbane/59-like oseltamivir-sensitive influenza A virus is sufficient to enhance transmission efficiency in the guinea pig model. Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that the oseltamivir-resistant NA improved mammalian transmissibility, such that human sH1N1 viruses encoding the NA-H275Y+D354G substitutions may have been able to outtransmit those that did not. In our model, this transmission advantage was conferred by the oseltamivir-resistant NA alone, without need for compensatory mutations in the HA protein or elsewhere in the viral genome. Finally, enhanced transmissibility, such as we have shown in our experiments, can explain the rapidity with which oseltamivir resistance was able to achieve fixation among human sH1N1 isolates, even in the absence of widespread oseltamivir use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Kirsten St. George of the Laboratory of Viral Diseases of the Wadsworth Center of the New York State Department of Health for graciously providing the clinical isolates used in this work. We also thank Peter Palese, Samira Mubareka, Anice C. Lowen, and John Steel for many helpful discussions and Lily Ngai for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases-funded Center for Research on Influenza Pathogenesis (CRIP) (HHSN266200700010C). N.M.B. has been supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award for Physician-Scientist Research Training in the Pathogenesis of Viral Diseases (T32 AI007623) and is currently funded by a National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases Career Development Grant (K08 AI089940).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 24 April 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Baz M, Abed Y, Boivin G. 2007. Characterization of drug-resistant recombinant influenza A/H1N1 viruses selected in vitro with peramivir and zanamivir. Antiviral Res. 74:159–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baz M, Abed Y, Simon P, Hamelin ME, Boivin G. 2010. Effect of the neuraminidase mutation H274Y conferring resistance to oseltamivir on the replicative capacity and virulence of old and recent human influenza A(H1N1) viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 201:740–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Belser JA, et al. 2012. Influenza virus respiratory infection and transmission following ocular inoculation in ferrets. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002569 doi:10.1371/journal/ppat.1002569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Belser JA, Maines TR, Tumpey TM, Katz JM. 9 December 2010, posting date Influenza A virus transmission: contributing factors and clinical implications. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 12:e39 http://dx.di.org/10/1017/S146233994100001705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bloom JD, Gong LI, Baltimore D. 2010. Permissive secondary mutations enable the evolution of influenza oseltamivir resistance. Science 328:1272–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bouvier NM, Lowen AC. 2010. Animal models for influenza virus pathogenesis and transmission. Viruses 2:1530–1563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bouvier NM, Lowen AC, Palese P. 2008. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza A viruses are transmitted efficiently among guinea pigs by direct contact but not by aerosol. J. Virol. 82:10052–10058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carrat F, et al. 2008. Time lines of infection and disease in human influenza: a review of volunteer challenge studies. Am. J. Epidemiol. 167:775–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Casalegno JS, et al. 2010. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1N1) viruses in south of France, 2007/2009. Antiviral Res. 87:242–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009. 2008–2009 influenza season week 14 ending April 11, 2009. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/weeklyarchives2008-2009/weekly14.htm [Google Scholar]

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2008. Influenza activity—United States and worldwide, 2007–08 season. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 57:692–697 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chao DL, Bloom JD, Kochin BF, Antia R, Longini IM., Jr 2012. The global spread of drug-resistant influenza. J. R Soc. Interface 9:648–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chou YY, et al. 2011. The M segment of the 2009 new pandemic H1N1 influenza virus is critical for its high transmission efficiency in the guinea pig model. J. Virol. 85:11235–11241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Collins PJ, et al. 2009. Structural basis for oseltamivir resistance of influenza viruses. Vaccine 27:6317–6323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Collins PJ, et al. 2008. Crystal structures of oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus neuraminidase mutants. Nature 453:1258–1261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Duan S, et al. 2010. Oseltamivir-resistant pandemic H1N1/2009 influenza virus possesses lower transmissibility and fitness in ferrets. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001022 doi:10.1371/journal/ppat.1001022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fodor E, et al. 1999. Rescue of influenza A virus from recombinant DNA. J. Virol. 73:9679–9682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hamelin ME, et al. 2011. Reduced airborne transmission of oseltamivir-resistant pandemic A/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Antivir. Ther. 16:775–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hay AJ, et al. 2008. Report, WHO Influenza Centre, London: characteristics of human influenza AH1N1, AH3N2, and B viruses isolated September 2007 to February 2008. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.nimr.mrc.ac.uk/documents/about/interim_report_mar_2008.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20. Herlocher ML, et al. 2004. Influenza viruses resistant to the antiviral drug oseltamivir: transmission studies in ferrets. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1627–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hoffmann E, Stech J, Guan Y, Webster RG, Perez DR. 2001. Universal primer set for the full-length amplification of all influenza A viruses. Arch. Virol. 146:2275–2289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang Y, et al. 2011. Temporal dynamics of host molecular responses differentiate symptomatic and asymptomatic influenza A infection. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002234 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hurt A. 13 March 2007, posting date Fluorometric neuraminidase inhibition assay, standard operating procedure WHO-025. Neuraminidase Inhibitor Surveillance Network, London, United Kingdom: http://www.nisn.org/documents/A.Hurt_Protocol_for_NA_fluorescence.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24. Itoh Y, et al. 2009. In vitro and in vivo characterization of new swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses. Nature 460:1021–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ives JA, et al. 2002. The H274Y mutation in the influenza A/H1N1 neuraminidase active site following oseltamivir phosphate treatment leave virus severely compromised both in vitro and in vivo. Antiviral Res. 55:307–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jayaraman A, et al. 2011. A single base-pair change in 2009 H1N1 hemagglutinin increases human receptor affinity and leads to efficient airborne viral transmission in ferrets. PLoS One 6:e17616 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Killingley B, et al. 2012. Use of a human influenza challenge model to assess person-to-person transmission: proof-of-concept study. J. Infect. Dis. 205:35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kramarz P, Monnet D, Nicoll A, Yilmaz C, Ciancio B. 2009. Use of oseltamivir in 12 European countries between 2002 and 2007: lack of association with the appearance of oseltamivir-resistant influenza A(H1N1) viruses. Euro Surveill. 14:pii=19112. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId-19112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lakdawala SS, et al. 2011. Eurasian-origin gene segments contribute to the transmissibility, aerosol release, and morphology of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002443 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lindemann J, et al. 2004. A numerical simulation of intranasal air temperature during inspiration. Laryngoscope 114:1037–1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lowen AC, Mubareka S, Steel J, Palese P. 2007. Influenza virus transmission is dependent on relative humidity and temperature. PLoS Pathog. 3:1470–1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lowen AC, Mubareka S, Tumpey TM, Garcia-Sastre A, Palese P. 2006. The guinea pig as a transmission model for human influenza viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:9988–9992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maher JA, DeStefano J. 2004. The ferret: an animal model to study influenza virus. Lab. Anim. (NY) 33:50–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maines TR, et al. 2009. Transmission and pathogenesis of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses in ferrets and mice. Science 325:484–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matrosovich M, Matrosovich T, Garten W, Klenk HD. 2006. New low-viscosity overlay medium for viral plaque assays. Virol. J. 3:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Meijer A, et al. 2009. Oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus A (H1N1), Europe, 2007–08 season. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:552–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Munster VJ, et al. 2009. Pathogenesis and transmission of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza virus in ferrets. Science 325:481–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Neumann G, et al. 1999. Generation of influenza A viruses entirely from cloned cDNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:9345–9350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Palese P, Shaw ML. 2007. Orthomyxoviridae: the viruses and their replication, p 1647–1678 In Knipe DM, Howley PM. (ed), Fields virology, vol 2 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 40. Patrozou E, Mermel LA. 2009. Does influenza transmission occur from asymptomatic infection or prior to symptom onset? Public Health Rep. 124:193–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pearce MB, et al. 2012. Pathogenesis and transmission of swine origin A(H3N2)v influenza viruses in ferrets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109:3944–3949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pica N, Chou YY, Bouvier NM, Palese P. 2012. Transmission of influenza B viruses in the guinea pig. J. Virol. 86:4279–4287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pleschka S, et al. 1996. A plasmid-based reverse genetics system for influenza A virus. J. Virol. 70:4188–4192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Potier M, Mameli L, Belisle M, Dallaire L, Melancon SB. 1979. Fluorometric assay of neuraminidase with a sodium (4-methylumbelliferyl-alpha-D-N-acetylneuraminate) substrate. Anal. Biochem. 94:287–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rameix-Welti MA, et al. 2006. Natural variation can significantly alter the sensitivity of influenza A (H5N1) viruses to oseltamivir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3809–3815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rameix-Welti MA, Enouf V, Cuvelier F, Jeannin P, van der Werf S. 2008. Enzymatic properties of the neuraminidase of seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses provide insights for the emergence of natural resistance to oseltamivir. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000103 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Seibert CW, et al. 2010. Oseltamivir-resistant variants of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus are not attenuated in the guinea pig and ferret transmission models. J. Virol. 84:11219–11226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Seibert CW, Rahmat S, Krammer F, Palese P, Bouvier NM. 2012. Efficient transmission of pandemic H1N1 influenza viruses with high-level oseltamivir resistance. J. Virol. 86:5386–5389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Steel J, Lowen AC, Mubareka S, Palese P. 2009. Transmission of influenza virus in a mammalian host is increased by PB2 amino acids 627K or 627E/701N. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000252 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wagner R, Matrosovich M, Klenk HD. 2002. Functional balance between haemagglutinin and neuraminidase in influenza virus infections. Rev. Med. Virol. 12:159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang S, et al. 2008. Simplified recombinational approach for influenza A virus reverse genetics. J. Virol. Methods 151:74–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. World Health Organization 2008. Influenza A(H1N1) virus resistance to oseltamivir: last quarter 2007 to 5 May 2008. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/H1N1ResistanceWeb20080505.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 53. World Health Organization 2008. Influenza A(H1N1) virus resistance to oseltamivir: last quarter 2007 to 5 May 2008. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/H1N1ResistanceWeb20080505.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 54. World Health Organization 2009. Table 2 seasonal influenza A(H1N1) virus resistant to oseltamivir, last quarter 2008 to 31 March 2009. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/2008-9NHemiResistanceTable2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 55. World Health Organization 15 February 2008, posting date WHO/ECDC frequently asked questions for oseltamivir resistance. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/influenza/oseltamivir_faqs/en/index.html#whatis [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yang JR, et al. 2011. Reassortment and mutations associated with emergence and spread of oseltamivir-resistant seasonal influenza A/H1N1 viruses in 2005–2009. PLoS One 6:e18177 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yen HL, et al. 2007. Neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant recombinant A/Vietnam/1203/04 (H5N1) influenza viruses retain their replication efficiency and pathogenicity in vitro and in vivo. J. Virol. 81:12418–12426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zaraket H, et al. 2010. Genetic makeup of amantadine-resistant and oseltamivir-resistant human influenza A/H1N1 viruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1085–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]