Abstract

Members of the Roseobacter lineage of marine bacteria are prolific surface colonizers in marine coastal environments, and antimicrobial secondary metabolite production has been hypothesized to provide a competitive advantage to colonizing roseobacters. Here, we report that the roseobacter Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I produces the blue pigment indigoidine via a nonribosomal peptide synthase (NRPS)-based biosynthetic pathway encoded by a novel series of genetically linked genes: igiBCDFE. A Tn5-based random mutagenesis library of Y4I showed a perfect correlation between indigoidine production by the Phaeobacter strain and inhibition of Vibrio fischeri on agar plates, revealing a previously unrecognized bioactivity of this molecule. In addition, igiD null mutants (igiD encoding the indigoidine NRPS) were more resistant to hydrogen peroxide, less motile, and faster to colonize an artificial surface than the wild-type strain. Collectively, these data provide evidence for pleiotropic effects of indigoidine production in this strain. Gene expression assays support phenotypic observations and demonstrate that igiD gene expression is upregulated during growth on surfaces. Furthermore, competitive cocultures of V. fischeri and Y4I show that the production of indigoidine by Y4I significantly inhibits colonization of V. fischeri on surfaces. This study is the first to characterize a secondary metabolite produced by an NRPS in roseobacters.

INTRODUCTION

The Roseobacter clade is a widely distributed, abundant, and biogeochemically active lineage of marine Alphaproteobacteria comprised of multiple genera, including Phaeobacter, Ruegeria, Loktanella, and Citreicella (12, 20). Roseobacter abundance and activity are often greatest in coastal marine environments and in association with phytoplankton blooms (7, 12, 20, 39, 58). The dominance of roseobacters under these conditions has been attributed, in part, to their ability to quickly colonize and out-compete other organisms for surface niches, including the surfaces of higher-order eukaryotes, such as phytoplankton and vascular plants (5, 19, 20, 46, 50, 52, 53). In addition to cell density-dependent regulatory mechanisms and morphological features, the production and secretion of bioactive metabolites are predicted to contribute to the colonization success of roseobacters (4, 10, 18, 26, 37). Our understanding of the chemical diversity and biological function of Roseobacter secondary metabolites, however, is limited.

Some of the earliest indications that Roseobacter representatives produce antimicrobial molecules are from studies seeking to identify probiotic bacteria for aquaculture. Hjelm et al. (2004) identified roseobacters that were antagonistic against fish larval bacterial pathogens and Phaeobacter gallaeciensis was demonstrated to have probiotic effects on scallop larvae (30a). The genetic underpinnings as well as structural and biological characterization of secondary metabolite production in roseobacters have been most extensively studied in strains that produce the antimicrobial compound tropodithietic acid (TDA). TDA has an unusual seven-member aromatic tropolone ring backbone, and its production has been demonstrated to be growth condition dependent (8, 9, 18, 23). TDA has been shown to inhibit the growth of pathogenic Vibrio species and aid in the competitive surface colonization of strains capable of its production (18, 44). The ability to synthesize TDA has been demonstrated in several Roseobacter genera, including Ruegeria and Phaeobacter species, and is a valuable model for Roseobacter secondary metabolite production. Genomic investigations, however, have shown that most sequenced roseobacters lack the characterized TDA biosynthesis pathway (39). Moreover, roseobacters are collectively known to synthesize a myriad of secondary metabolites of undefined function (6, 7, 10, 12, 34, 58).

Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I of the Roseobacter lineage was isolated from pulp mill effluent in the coastal southern United States; the strain produces a dark blue, water-insoluble pigment when grown on agar plates containing a complex medium (13). The production of this pigment has not previously been reported in characterized Phaeobacter daeponensis strains, which share 99% identity of the 16S rRNA gene with Y4I; however, Phaeobacter sp. strain Y3F, which was isolated alongside Y4I, and isolates of Phaeobacter caeruleus have been reported to be blue on complex media (11, 57, 62). Y4I has been characterized with respect to its ability to catabolize aromatic compounds (11, 13), and its genome sequence is available, providing additional insight into the metabolic potential of this strain (39). Preliminary studies have shown that Y4I suppresses the growth of representative marine bacteria such as Vibrio fischeri, Vibrio anguillarum, and Ruegeria lacuscaerulensis on agar plates (53), yet it does not have the required genes for TDA biosynthesis (39). Here, we identify the genes that encode the biosynthetic machinery that synthesizes the blue pigment and characterize biological roles of this metabolite not previously reported in roseobacters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions and media.

Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I was isolated from an indulin enrichment of coastal seawater as reported previously (13, 53). Unless otherwise noted, the following culture conditions were used: Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I was maintained in YTSS broth (per liter, 2.5 g of yeast extract, 4 g of tryptone, 15 g of sea salts [Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO]) at 30°C, with shaking. YTSS agar (1.5%) plates were used for streaking to isolation and were also incubated at 30°C. Escherichia coli EA145, which is auxotrophic for 2,4-diaminopimelic acid (DAP), was maintained in YTSS liquid with 1 mM DAP (Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium) at 30°C with shaking (24). V. fischeri ES114 (ATCC 700601), kindly provided by Eric Stabb (University of Georgia), was maintained on YTSS broth at 23°C with shaking.

Generation of transposon mutant library.

A random mini-Tn5 transposon library of Y4I was generated by conjugal transfer of plasmid pRL27::mini-Tn5-Kmr-oriR6K from E. coli EA145 using previously described methods (35). Briefly, liquid mating mixtures of donor and recipient cells were prepared with 200 μl of early-log-phase cells (optical density at 540 nm [OD540] of ≈0.35) and combined in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes. The cell mixture was pelleted by centrifugation and suspended in 15 μl of fresh YTSS broth. The mating mixture was spotted onto YTSS agar with 1 mM DAP and incubated at 30°C overnight. With the use of a sterile toothpick, the microbial biomass was removed and suspended in 1 ml of fresh YTSS broth. The suspension was plated on YTSS agar with kanamycin (25 μg/ml) and incubated at 30°C overnight. Kanamycin-resistant (Kmr) colonies were patched to fresh selective medium, and the library was drawn from those plates. Unless otherwise stated, all subsequent growth of Tn5 mutants was done in YTSS agar containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin.

Screen for V. fischeri inhibition.

To screen for suppression of V. fischeri, the mini-Tn5 mutant library was inoculated into 96-well plates (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ) containing YTSS broth, without antibiotic. The stability of the Kmr marker in the absence of antibiotic selection was demonstrated for randomly selected mutants (data not shown). Mid-exponential-phase V. fischeri ES114 was spread to lawn density on 22-cm by 22-cm YTSS agar plates. A 96-pin replicator (Nunc 250520; Rochester, NY) was used to spot 1 μl of broth culture from each well of the mini-Tn5 library onto the ES114 lawn. The plates were incubated at 23°C and scored after 24 h. The presence of a zone of clearing was considered indicative of inhibition.

Arbitrary PCR and DNA sequencing of mini-Tn5 transposon mutants.

Arbitrary PCR was used to localize Tn5 chromosomal insertion sites in selected mutants using a previously described method (42). Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted from overnight cultures of the selected mutants using a DNeasy Mini-Prep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and 100 ng was used for the subsequent amplifications. The transposon-specific forward primer TNPR13Out (5′-CAG CAA CAC CTT CTT CAC GA-3′) and the tagged reverse primer ARB1 (5′-GGC CAC GCG TCG ACT AGT ACN NNN NNN NNN GAT AT-3′) were used to amplify DNA upstream of the 5′ end of the insertion. The reverse primer TNPR17Out (5′-AAC AAG CCA GGG ATG TAA CG-3′) and the forward primer ARB6 (5′-GGC CAC GCG TCG ACT AGT ACN NNN NNN NNN ACG CC-3′) were used to amplify downstream of the 5′ end of the insertion. The initial amplification cycles consisted of a denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min and five cycles of 30 s of denaturation at 94°C, 30 s of annealing at 30°C, and a 1-min extension at 72°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s of denaturation at 94°C, 30 s of annealing at 45°C, and a 1-min extension at 72°C, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The products of the initial amplification were used in the subsequent nested amplification step. The forward primer TNPR13Nest (5′-CTA GAG TCG ACC TGC AGG CAT-3′) and the ARB2 reverse primer (5′-GGC CAC GCG TCG ACT AGT AC-3′) were used to remove nonspecific amplification of the upstream PCR. TNPR17Nest (5′-CTG ACA TGG GGG GGT ACC-3′) and ARB2 were used to clean the downstream amplification. The PCR for the nested amplification consisted of a denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s of denaturation at 94°C, 30 s of annealing at 30°C, and a 1-min extension at 72°C, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

The products of the arbitrary amplification reactions were sequenced by fluorescent dye-terminator cycle sequencing at the University of Tennessee Molecular Biology Resource Facility. Homology searches (BLASTX) were conducted using the NCBI online server. The locations of transposon insertions were then manually mapped to the published draft genome of Y4I (GenBank accession number ABXF00000000).

Purification and analysis of the blue pigment.

Extraction and purification of the blue pigment were performed following methods outlined in Takahashi et al. (55). Briefly, ∼103 CFU/ml broth culture of a clpA::Tn5 mutant was spread on YTSS agar plates and incubated at 30°C until large, darkly pigmented colonies formed (∼48 h). The colonies were removed from plates using cell scrapers (Corning, Corning, NY), and cellular biomass was placed in a 50-ml conical tube (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The mass of the collected cells was recorded, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added at 1 ml 10 mg−1 of cells. The tube was placed on ice, and the cells were lysed using a Microson Ultrasonic Cell Disrupter XL 2000 (Qsonica, Newtown, CT) with four cycles of 5 s of burst and 5 s of rest. The output power was set at 8 W. The cellular debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and recentrifuged. This was repeated until no cellular pellet could be seen. The supernatant was passaged through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter. The pigment was precipitated by addition of sterile Milli-Q water at five times the volume of the DMSO. This solution was then ultracentrifuged at 50,000 × g for 1 h using a Sorvall WX Ultra 80 (Thermo Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ) at 23°C. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was washed with sterile Milli-Q water. The pellet was dried using a Savant SpeedVac SC110 (Thermo Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ).

The lyophilized pigment was solubilized in DMSO and diluted 1:10 for UV/visible light (Vis) absorbance measurements using a Beckman Coulter DU 800 spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). A high-resolution mass spectrum of the lyophilized pigment was measured on an AccuTOF mass spectrometer (JEOL, Peabody, MA) using a DART (direct analysis in real time) ion source in positive ion mode. The 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrum was recorded on a Varian INOVA 500 MHz spectrometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) using the blue pigment dissolved in deuterated DMSO.

Motility assay.

Swimming motility was assessed using 0.35% agar–10% YTSS plates (per liter: 0.25 g of yeast extract, 0.4 g of tryptone, 15 g of sea salts, and 3.5 g of agar) as described previously (1, 2). Ten microliters of stationary-phase cultures (OD540 of ∼1.5) was spotted onto the motility plates and incubated at 30°C and scored after 24 h by measuring the diameter of the swim circle.

Surface colonization assay.

Surface colonization was measured in 96-well vacuum-gas plasma-treated polystyrene plates (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with 20% YTSS broth (per liter, 0.5 g of yeast extract, 0.8 g of tryptone, 15 g of sea salts). YTSS at 20% was used to minimize flocculation by some of the mini-Tn5 mutants (data not shown). The Y4I variants were inoculated in triplicate at a concentration of ∼1 × 106 CFU/ml. A sterile 4-mm glass bead (Walter Stern, Post Washington, NY) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated under stationary conditions at 27°C. Samples were taken at 2, 4, 6, 10, 12, 14, 24, 48, and 72 h postinoculation. Attached cells were removed from the beads by a modified version of the method of Leriche and Carpentier (36) that has been used previously for roseobacters (18, 36). At each time point, three beads were removed and placed in glass screw-top vials with 940 μl of YTSS broth and 60 μl of 10% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (Fischer Scientific, Pittsburg, PA). Samples were ultrasonicated at 40 kHz in a water bath sonicator (Branson, Danbury, CT) for 6 min and vortexed for 30 s. Samples were then serially diluted and plated for CFU counts. The addition of Tween 20 was to limit cell clumping evident under phase-contrast microscopy of early trials. Preliminary experiments using the wild-type and igiD::Tn5 strains showed no significant loss of viability due to the treatment (data not shown).

Coculture competition assays.

For broth culture assays, 50 μl of stationary-phase wild-type or mutant cultures of Y4I (∼5 × 109 CFU/ml) was inoculated into 10 ml of YTSS broth lacking antibiotic with 50 μl of overnight V. fischeri culture (∼5 × 109 CFU/ml) in triplicate. V. fischeri and Y4I variant monoculture control cultures were prepared and run in parallel. The cultures were incubated for 20 h at 27°C due to the similar growth rates of both strains at that temperature (data not shown). Aliquots were removed and serially diluted for CFU counts. Plates were incubated at 34°C, a prohibitive temperature for V. fischeri, for Y4I viable counts and at 20°C for V. fischeri viable counts. The two strains can be differentiated at 20°C because of the delayed emergence of visible Y4I colonies relative to V. fischeri at this temperature. In order to address the question of whether a density advantage is necessary to see evidence for a competitive interaction between the Y4I variants and V. fischeri, competition assays were also performed in which the initial concentration of V. fischeri was 104 CFU/ml and that of Y4I was 106 CFU/ml.

For competition assays on surfaces, overnight broth cultures of the Y4I strains and V. fischeri were diluted to ∼1 × 106 CFU/ml in 20% YTSS broth and added to 96-well plates with glass beads. Monocultures of each strain were used as no-competition controls. All competitions and controls were performed in triplicate. The cocultures were incubated for 24 h at 27°C in 20% YTSS broth and then ultrasonicated to liberate the cells for CFU counts, as described above.

Assessment of HOOH sensitivity.

Strains were exposed to hydrogen peroxide in broth using a method similar to that previously reported for Dickeya dadantii (48). Stationary-phase Y4I broth cultures (∼109 CFU/ml) were exposed to 250 mM hydrogen peroxide in YTSS broth, which has been shown in the lab to be inhibitory to the wild type (data not shown). The strains were exposed in 1-ml aliquots for 10 and 60 min at 30°C, with shaking. The cultures were then serially diluted and plated for CFU counts. All experiments were done in triplicate.

Peroxide resistance was also monitored in surface-attached cells by exposing biofilms on glass beads to 75 mM hydrogen peroxide, a concentration experimentally determined to be inhibitory to wild-type Y4I biofilms (data not shown). Wild-type Y4I biofilms were grown on glass beads for 24 h in 20% YTSS broth, as described above. Biofilms of the igiD mutant were incubated for 4 h to ensure comparable numbers of cells per bead (∼5 × 105 CFU/bead). The beads were then removed from the growth medium and exposed to 75 mM hydrogen peroxide in 20% YTSS broth for an immediate exposure and for 2-, 5-, 10-, 15-, 30-, and 60-min incubations. The immediate exposure involved a transfer to and immediate removal from the hydrogen peroxide solution. Biofilms were then removed as described earlier and serially diluted for CFU plate counts. CFU counts were compared to a no-hydrogen peroxide control. All experiments were done in biological and technical triplicate.

RNA extraction.

RNA was extracted from colonies grown on agar plates, cells grown in broth cultures, flocking cells from broth cultures, and biofilms grown on polycarbonate. Collected cells were briefly centrifuged at 5,000 × g to pellet. The supernatant was removed, and the cells were resuspended in 200 μl of RNAlater RNA stabilization reagent (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). The RNA was extracted using a Qiagen RNeasy Mini-Kit. After extraction of the RNA, DNA was removed using a Turbo DNA-free Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Samples were checked for the presence of DNA by PCR after DNase treatment to ensure purity.

Reverse transcription and quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR).

The resulting RNA sample was converted to cDNA using Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase and random hexamers (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). A mixture of 0.5 μl of the random primers (500 ng/μl), 1.0 μl of a deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) mix (10 mM), and 10.5 μl of the RNA sample (6 ng/μl) were heated to 65°C for 5 min and then chilled on ice. Four microliters of 5× First Strand Buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 375 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2), 2 μl of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, and 1 μl of RNase Out (Invitrogen) were then added. The solution was mixed and incubated at 37°C for 2 min. One microliter of M-MLV reverse transcriptase (200 units/μl) was added to the solution and incubated for 10 min at 25°C, followed by 50 min at 37°C. The enzyme was inactivated by heating for 15 min at 70°C.

RT-qPCR assays were used to measure gene expression of indigoidine biosynthesis genes as well as reference genes. Three reference genes (map, rpoC, and alaS) were selected using previously described criteria (40). Primers were designed for the three reference genes, and the indigoidine biosynthesis nonribosomal peptide synthase ([NRPS] igiD) using the Primer3 online software tool (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/) and the Y4I genome sequence (NCBI reference sequence NZ_ABXF00000000.1). All primer sets were tested on genomic Y4I DNA and yielded a single band of the expected size. Primers for the RT-qPCR are as follows: for igiD, 5′-GGT CAG AAA GGA CGC GTC GCG G-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGC GCG CGA TGC CGA GCT GAT C-3′ (reverse); map, 5′-GTG TTC CAC GCC CCG CCC AAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCC GGC CGG TGA CAG GGT GAA-3′ (reverse); rpoC, 5′ CGG CGC TGA AGC GAT CCG TGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCG GAC GGT TGC CCG ATT CCA-3′ (reverse); and alaS, 5′-GCT GTG GGC GGA GGG GCA ATG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCC GAT CGA ACC GCC GGT GAC-3′ (reverse). Optimum qPCR amplification conditions for each primer set were determined by performing control runs using various concentrations of forward and reverse primer (from 100 to 1500 nM) and a set genomic DNA concentration of 2.5 × 105 genomes per reaction mixture. The primer concentration that gave the lowest threshold cycle (CT) value and had the highest efficiency was chosen as the optimum concentration for the following reactions. All primer sets yielded a product between 160 and 240 bp. The PCR was done in a Bio-Rad DNA Engine Opticon 2 real-time PCR detector (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with SYBR green PCR reagents (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reaction mixtures of 25 μl were prepared in 0.2-ml skirted 96-well qPCR plates (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) with 12.5 μl of SYBR green Pre-Mix 2X, 7.5 μl of distilled H2O (dH2O), 1.25 μl of forward primer, 1.25 μl of reverse primer, and 2.5 μl of the sample cDNA. Plates were subjected to thermocycling at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 65°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 15 s, with a final step at 72°C for 5 min. Melting curves were generated after each assay to verify the specificity of the amplification by heating the samples from 50°C to 100°C at 1°C/s and taking fluorescence measurements every 1.0°C. These melt curves consistently showed a single peak indicating high specificity of the primer sets.

Statistical analyses.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) mean separations were done using Tukey's honestly significant difference test in SigmaPlot, version 11.0 (Systat Software, Inc., Chicago, IL). RT-qPCR data analysis and the normalized relative transcript quantity were calculated using the qBASE method, which permits the use of multiple reference genes to guarantee reference gene stability as well as the use of biological replicates to guarantee experiment reproducibility (29). These data were normalized to the three reference genes and relative to late-exponential broth cultures of the wild type.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The antagonistic behavior of Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I is correlated with pigmentation.

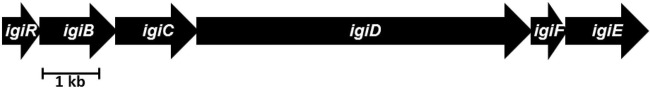

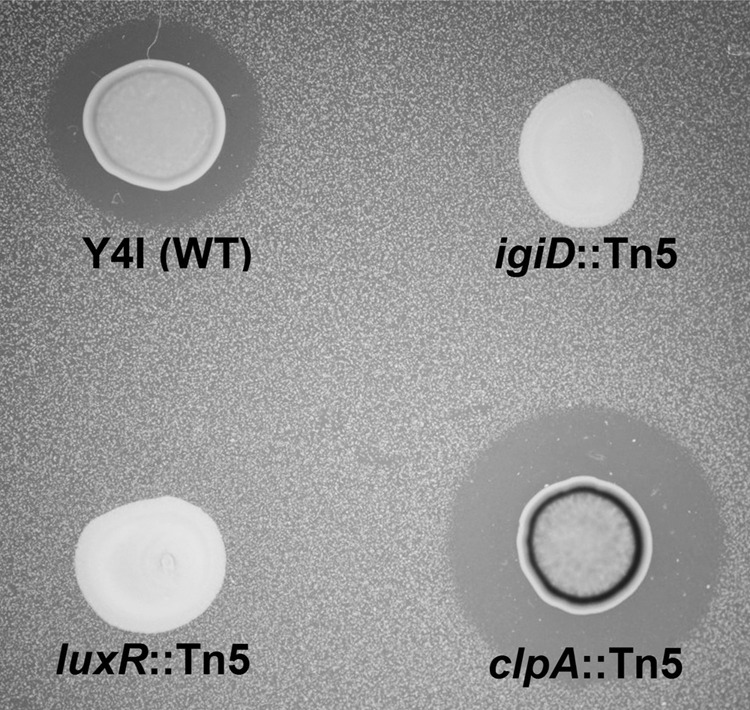

As some secondary metabolites in roseobacters have been found to be antimicrobial in nature (10, 38), we sought to determine if the previously reported antagonistic behavior of Y4I toward Vibrio fischeri (53) was correlated with the production of a blue pigment characteristic of Y4I growth on complex agar medium (Fig. 1). To that end, we generated a 6,048-member mini-Tn5 random transposon mutant library of Y4I and screened for mutants with alterations in the V. fischeri inhibition phenotype. Forty-five Tn5 mutants were unable to inhibit V. fischeri. A direct correlation was observed between lack of pigmentation and failure to inhibit the growth of V. fischeri in plate assays. Five hyperpigmented mutants were also isolated and demonstrated enhanced inhibition of V. fischeri (Fig. 1). The insertion site of the mini-Tn5 cassette was determined for all 50 of these mutants using arbitrary PCR. Twelve nonpigmented mutants had transposon insertions in either a gene predicted to encode a nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), annotated as an indigoidine synthase (igiD), or two adjacent genes, designated igiB and igiC, that form a putative operon with igiD and three additional genes (Table 1, Fig. 2). Among the eight igiD mutants, four independent insertion sites were represented. Two independent mutants were obtained for both igiB and igiC. The randomly inserted mini-Tn5 cassette has been shown previously to allow readthrough to downstream genes (35), suggesting that igiB, igiC, and igiD are all necessary for pigmentation in this strain. Polar effects, however, cannot be ruled out, and additional studies are required to determine this conclusively. Other nonpigmented mutants were found to have transposon insertions in each of two luxRI-like quorum-sensing systems annotated in the Y4I genome, suggesting that quorum sensing is involved in pigment production. The remaining 28 nonpigmented mutants were localized to genes encoding poorly characterized transcriptional and response regulators, methyltransferases, and hypothetical proteins (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The five hyperpigmented mutants that showed enhanced V. fischeri inhibition all had insertional disruptions in a gene encoding the universal regulatory chaperone protein ClpA. Within those five mutants, three independent insertion sites were represented. In E. coli, ClpA has been shown to be involved in the degradation of abnormal and regulatory proteins, suggesting that an insertion in clpA may enhance pigment production due to alterations in gene regulation (25, 32). Representative igiD::Tn5 and clpA::Tn5 mutants were selected for further phenotypic characterizations described below; none of these mutants displayed growth abnormalities in broth cultures.

Fig 1.

Qualitative screen for V. fischeri inhibition by Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I. The wild type (WT) and Tn5 insertional mutants are shown on a lawn of V. fischeri. igiD encodes the indigoidine NRPS, clpA encodes a regulatory protein protease, and luxR encodes a regulatory protein involved in quorum sensing.

Table 1.

Representative Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I Tn5 insertional mutants

| Interrupted gene (GenBank locus tag) | Position of mini-Tn5 cassettea | Pigmentationb | V. fischeri inhibitionb |

|---|---|---|---|

| igiB (RBY4I_1554) | 586 (1) | − | − |

| 606 (1) | − | − | |

| igiC (RBY4I_3713) | 362 (1) | − | − |

| 498 (1) | − | − | |

| igiD (RBY4I_2890) | 595 (2) | − | − |

| 1692 (2) | − | − | |

| 2968 (2) | − | − | |

| 2496 (2) | − | − | |

| luxR (RBY4I_1689) | 269 (1) | − | − |

| 373 (1) | − | − | |

| luxI (RBY4I_3631) | NA (0) | NA | NA |

| luxR (RBY4I_1027) | 429 (1) | − | − |

| 154 (1) | − | − | |

| luxI (RBY4I_3464) | 373 (1) | − | − |

| clpA (RBY4I_3424) | 443 (3) | ++ | ++ |

| 446 (1) | ++ | ++ | |

| 447 (1) | ++ | ++ |

Nucleotide position within the designated gene; the number of individual mutants isolated with an insertion at that position are indicated in parentheses.

Pigmentation and inhibition scores are relative to the wild type as determined by plate assays: −, no pigmentation and no inhibition; ++ enhanced pigmentation and inhibition. NA, not applicable; no mutants with insertions in the gene were found in the library.

Fig 2.

Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I indigoidine biosynthesis operon. The organization of the genes within the operon (RBY4I_313, RBY4I_1554, RBY4I_3713, RBY4I_2890, RBY4I_618, and RBY4I_1719) was obtained from the published genome sequence. The genes are represented by page arrows, which indicate orientation and are shown to scale. Gene product names are given in Table 2.

Pigment characterization.

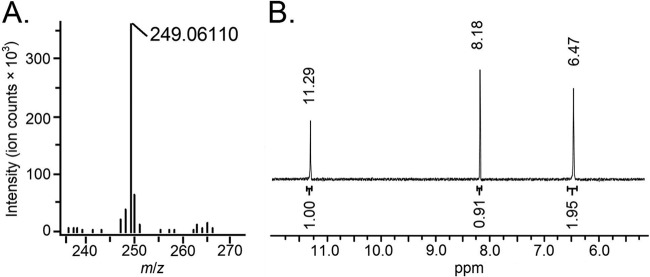

Identification of interrupted genes in the nonpigmented mutants suggested that the blue compound produced by Y4I was indigoidine, a bicyclic 3,3′-bipyridyl molecule synthesized by the cyclization of two glutamine molecules (55). This was further confirmed by analysis of the purified pigment. The absorbance spectrum of the purified compound in DMSO has a peak at 612 nm, which has been previously reported as the absorbance maximum of indigoidine (33). Profiles of the Y4I variant show that absorbance at this wavelength for the clpA::Tn5 mutant is approximately five times higher than that of the wild-type strain (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis yielded a [M+H]+ peak at 249.06110 m/z (Fig. 3A), which is consistent with the chemical formula C10H9N4O4 for indigoidine with an ionizing proton (21). The 1H-NMR spectra contained three singlets at 11.29, 8.18, and 6.47 ppm that had relative integrations of 1, 1, and 2 protons, respectively (Fig. 3B). These chemical shifts, splitting patterns, and integrations are consistent with those expected for the —NH, —CH, and —NH2 bonds of indigoidine, respectively, and are identical to previously published reports (55).

Fig 3.

Chemical analyses of purified pigment. (A) Mass spectrum analysis by high-resolution MS-DART. The peak m/z at 249.06110 is consistent with protonated indigoidine (C10H9N4O4). (B) 1H-NMR spectrum shows peaks at 11.29 (NH), 8.18 (CH), and 6.47 (NH2), which is consistent with the published spectrum of indigoidine (55).

Genes encoding indigoidine biosynthesis.

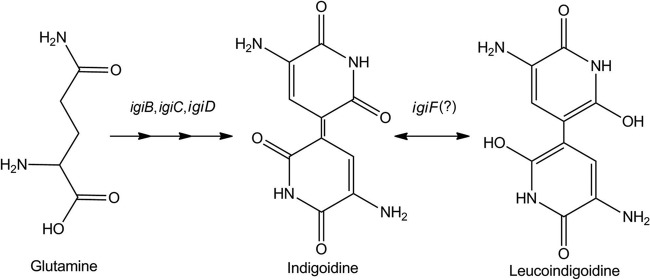

Indigoidine is synthesized by an NRPS encoded by a gene typically annotated as either igiD or indC (Fig. 4 and Table 2) (48, 55). Previous studies of the chemistry of indigoidine focused on its redox activity and deep blue pigmentation for use as a possible redox state sensor or industrial dye (21, 30, 33, 54). Its biological role as a secondary metabolite, however, remains poorly characterized. Indigoidine is found in two redox states, an oxidized blue form which is insoluble in water and a reduced colorless form which is water soluble and historically referred to as leucoindigoidine (21, 30, 33, 47, 54). It is currently hypothesized that indigoidine is synthesized in the oxidized form and that subsequent reduction is biologically mediated (48, 55), possibly by the oxalocrotonate tautomerase encoded by igiF (Table 2 and Fig. 3) though this has not been experimentally confirmed. Given the solubility issues of the oxidized compound, it is anticipated that the reduced state is the biologically relevant form for the inferred antimicrobial properties. This is supported by assays performed with the isolated oxidized compound in either a lyophilized state or solubilized in DMSO (data not shown). Unfortunately, reduction of purified indigoidine requires a strong acid, with reoxidation occurring readily under nonreducing conditions (21, 54). These features prevent biological assays with the isolated compound in a reduced state. Thus, it could be argued that indigoidine needs to be in the appropriate biological context in order to function as predicted and that this is an important area for future investigation.

Fig 4.

Proposed mechanism of indigoidine biosynthesis by Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I. (Indigoidine and leucoindigoidine structures are derived from references 48 and 55).

Table 2.

Comparison of genes in indigoidine biosynthesis operons

| Y4I operon | Annotation | Homolog in Gammaproteobacteria or Streptomyces operona | % Amino acid identity to V. indigofera operon | % Amino acid identity to Dickeya dadantii 3937 operon |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAd | DNA binding transcriptional regulator | pecS | 39c | 100 |

| NA | Membrane bound transcriptional regulator | pecM | 44c | 100 |

| NA | Pseudouridine-5'-phosphate glycosidase family | indA | 0 | 100 |

| NA | Phosphoglycolate phosphatase | indB | 0 | 100 |

| igiR | tetR family regulator | NA | 40 | NA |

| igiAb | 4′-Phosphopantetheinyl transferase | NA | 40 | NA |

| igiB | 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase family | NA | 54 | NA |

| igiC | Glutamate racemase | NA | 58 | NA |

| igiD | Indigoidine synthase | indC | 54 | 49 |

| igiF | 4-Oxalocrotonate tautomerase | NA | NA | NA |

| igiE | Major facilitator family transporter | NA | 58 | NA |

The Gammaproteobacteria included in this table are D. dadantii, Serratia proteamaculans, and Photorhabdus asymbiotica (NC_014500.1, NC_009832.1, and NC_012962.1, respectively). Streptomyces included in this table are S. albus and S. lavendulae (NZ_ABYC00000000.1 and AB240063, respectively).

In Y4I, igiA is not located in the indigoidine biosynthesis operon but is found in a different area of the chromosome.

pecS and pecM are hypothesized to be required for indigoidine biosynthesis in V. indigofera (AF088857.1) but are found together in a different area of the chromosome from the igi operon.

NA. not applicable; no homolog of the gene was found in the respective organism.

Indigoidine biosynthesis genes have been identified in a phylogenetically diverse group of microbes, including Alpha-, Beta-, and Gammaproteobacteria, as well as several Streptomyces species (14, 21, 30, 48, 55). The biosynthesis operon of Y4I shares the most homology with putative indigoidine biosynthesis genes from the betaproteobacterium Vogesella indigofera (AF088856) that are deposited in GenBank but are not described in the literature (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The single common gene present in all characterized indigoidine-producing strains is the aforementioned NRPS-like indigoidine synthase, designated either igiD or indC. Sequence similarity alone indicates that the IgiD of Y4I and the IndC of the plant pathogen Dickeya dadantii 3937 (formally Erwinia chrysanthemi) are functionally homologous, sharing 50% identity and 63% similarity across the 1,314 residues of the sequence. Genes adjacent to the gene encoding the NRPS likely serve to modify either the substrate or product or to produce cofactors necessary for indigoidine synthesis; these modifiers typically differ between lineages (Table 2).

Phenotypic characterization of indigoidine mutants.

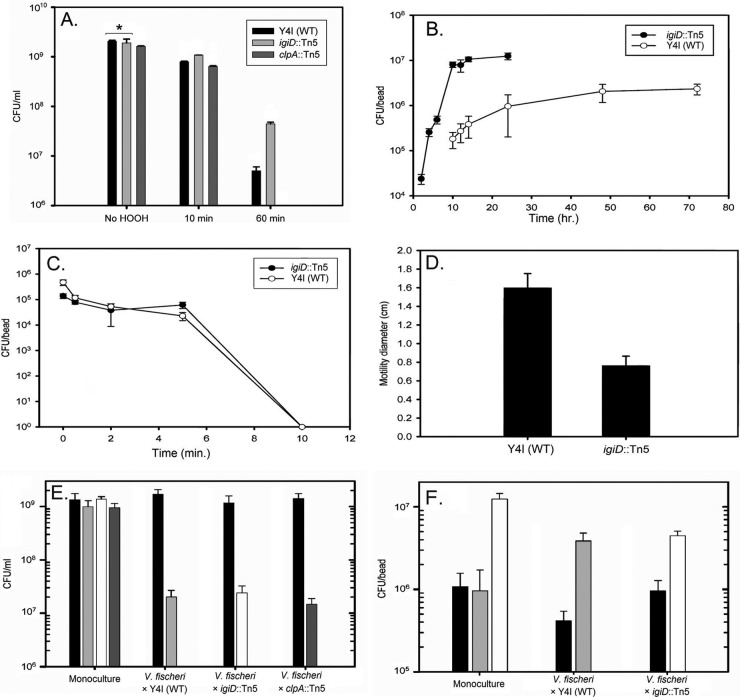

It has been suggested that indigoidine provides protection to D. dadantii through the neutralization of reactive oxygen species generated by the plant during bacterial infection (48). As this was the only reported biological role for indigoidine to date, we sought to address whether a similar protection was afforded to Y4I. Thus, hydrogen peroxide resistance of the wild type and the igiD::Tn5 and clpA::Tn5 mutants was assayed. Surprisingly, both the wild type and the clpA::Tn5 mutant were much more sensitive to hydrogen peroxide exposure than the igiD::Tn5 mutant (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5A). Given the broad range of regulatory proteins predicted to be affected by ClpA mutations, it is unclear whether the clpA::Tn5 strain has enhanced susceptibility due to overproduction of indigoidine or an unrelated physiological change. Therefore, the clpA::Tn5 mutant was omitted from further assays, with the exception of the competition assays in broth, where constitutive indigoidine production could be evaluated.

Fig 5.

Phenotypic characterization of Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I and mutants with alterations in indigoidine biosynthesis. (A) Viable cell counts of planktonic Y4I variants after exposure to 250 mM hydrogen peroxide for 0 (No HOOH), 10, and 60 min. The asterisk denotes cell counts that are the same (P < 0.001); all others are statistically different from each other (P ≤ 0.05). (B) Viable counts of wild-type (WT) Y4I and the igiD::Tn5 strain as they colonize a glass surface over time. (C) Viable cell counts of attached Y4I (WT) and the igiD::Tn5 strain after exposure to 75 mM hydrogen peroxide from 0 to 10 min. (D) Diameter of swim zone of Y4I (WT) and igiD::Tn5 strains on soft-agar motility plates. Viable counts of competitions between planktonic Y4I variants and V. fischeri in broth culture (E) and in biofilms (F) are shown. Black bars, V. fischeri, light gray bars, Y4I (WT); white bars, igiD::Tn5; dark gray bars, clpA::Tn5. Error bars represent the standard deviation of biological and technical triplicates.

Given that Y4I has been demonstrated to form prolific biofilms (53) and that indigoidine production in this strain is most visually apparent when cells are grown on agar surfaces, sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide was also assayed on cells grown in biofilms. Interestingly, while there was no difference in the growth rate of the wild type and the igiD::Tn5 mutant in broth cultures, differences were seen in the rates of surface colonization. The igiD::Tn5 mutant colonized surfaces significantly earlier and to a higher cellular density than the wild type (Fig. 5B) (P < 0.001). Due to the difference in colonization density and rate, biofilms were allowed to develop for a period of time that allowed for comparable cellular densities between the wild type and the mutant (wild type, 24 h; igiD::Tn5 mutant, 4 h). Under these conditions, there was no significant difference in hydrogen peroxide sensitivity between the strains (Fig. 5C). The discrepancy between broth culture and biofilms is likely due to the poor penetration of reactive oxygen in biofilms, limiting cellular exposure (16, 17). Moreover, the innate resistance of Y4I to hydrogen peroxide exposure is considerably higher than that of D. dadantii (>150 mM hydrogen peroxide [data not shown] versus ∼10 mM [48], respectively). Thus, it may be the inherent differences in sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide that influence the role, or lack thereof, of indigoidine as a protectant in these two organisms.

The difference in the rates of surface colonization evident between the wild type and the igiD::Tn5 mutant was unexpected, yet intriguing. Given that flagella are essential for surface colonization in many proteobacteria (28, 41), the igiD::Tn5 mutant was assayed for defects in motility. Motility of the igiD::Tn5 mutant was inhibited in soft-agar assays relative to that of the wild type (Fig. 5D) (P < 0.001), but the mutant showed signs of swimming when viewed microscopically. Twitching and swarming motilities of the mutant showed no significant difference in comparison to those of the wild type (data not shown). Collectively, the motility and colonization assays suggest that basal indigoidine production contributes to swimming motility and the surface attachment rate of Y4I. In this way, indigoidine biology may share features with that of a structurally similar group of redox-active, nitrogen-containing heterocyclic secondary metabolites known as phenazines (43). In pseudomonads, alterations in motility, surface attachment, and biofilm formation have all been associated with defects in phenazine production (41, 43, 45, 59). Similarly, indigoidine may play a role as an intracellular signaling molecule. This is not unprecedented as secondary metabolites in other roseobacters have been shown to have signaling properties. For example, in Ruegeria (formerly Silicibacter) sp. strain TM1040, TDA is an autoinducer of the genes necessary for biosynthesis and transport (22).

Regulation of indigoidine biosynthesis.

Previous studies have demonstrated that indigoidine biosynthesis is under transcriptional regulation and that its production is influenced by environmental factors, including growth medium (30, 33, 47, 54, 55). Among the organisms that produce indigoidine, however, the characterized mechanisms of regulation and the conditions that favor indigoidine biosynthesis are quite varied. In Streptomyces lavendulae, the induction of indigoidine production is evident only upon addition of a synthetic analog of lactone-based quorum-sensing molecules, γ-nonalactone (55). In the plant pathogen D. dadantii, expression of the indigoidine biosynthesis gene cluster is mediated by the PecS-PecM transcriptional regulatory system, which similarly controls the production and secretion of extracellular pectinases and cellulases that are required for invasion of the plant host (47, 48). Interestingly, in both S. lavendulae and D. dadantii, discovery of indigoidine biosynthesis was serendipitous as neither strain produces the metabolite when grown under standard laboratory conditions. This is not the case for Y4I, where blue colonies on agar plates are diagnostic of the strain and pigmentation is not evident in aerated broth cultures, except where there is biofilm formation at the liquid-air interface on the wall of the growth vessel. Thus, the regulation of indigoidine biosynthesis in Y4I is in response to different stimuli than those characterized for S. lavendulae and D. dadantii and more consistent with conditions described to induce TDA production in Ruegeria and Phaeobacter strains (4, 22, 23).

Indigoidine production in Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I is associated with growth on surfaces.

The antagonistic behavior exhibited by Y4I against V. fischeri on agar plates was not evident when strains were inoculated in broth cocultures at equal starting densities (Fig. 5E) nor when the Y4I strains had an initial 100-fold density advantage (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Viable counts of V. fischeri following coculture with Y4I or either mutant in broth showed no significant inhibition of V. fischeri versus controls lacking Y4I strains (P > 0.200). In fact, all three Y4I variants were significantly outcompeted nearly 100-fold by V. fischeri (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5E) when the cultures were seeded at equal initial cell densities. The inability of the hyper-indigoidine-producing strain (clpA::Tn5) to inhibit V. fischeri in broth cultures, even when provided a density advantage, suggests that the production of indigoidine does not provide a competitive advantage when cells are growing planktonically. This result could be due to the redox state of indigoidine in agitated broth cultures, which was oxidized and visually evident by the blue pigment in cocultures containing the clpA::Tn5 strain. An alternative explanation is that V. fischeri susceptibility to indigoidine is growth condition dependent.

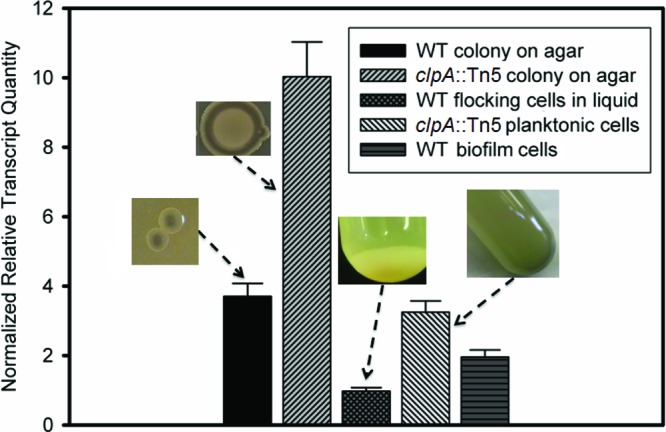

The gene expression data presented for the wild-type strain show upregulation of igiD when the strain grows as colonies on agar surfaces and in biofilms compared to growth in broth cultures (Fig. 6). The hyperpigmented clpA::Tn5 mutant showed the highest levels of igiD gene expression. In all cases, phenotypic observations of pigmentation support the gene expression data (Fig. 6). Low levels of igiD gene expression in high-density (∼109 CFU/ml) broth cultures and flocs of cells in wild-type Y4I suggest that high cellular densities alone are insufficient to induce indigoidine production. Tn5 mutants with insertions in either of the two LuxIR quorum-sensing systems present in Y4I, however, also lack indigoidine production, suggesting a role for both systems in its biosynthesis (Table 1).

Fig 6.

igiD gene expression of Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I (wild type [WT]) and the clpA::Tn5 mutant under different culture conditions. Expression levels are normalized to three reference genes and relative to late-exponential (16.5 h) wild-type planktonic cells. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. Images show the phenotype of each strain in the culture condition measured.

Given the evidence for upregulation of indigoidine biosynthesis in biofilms, we investigated whether indigoidine production by wild-type Y4I could inhibit the colonization of V. fischeri in biofilms. Monoculture controls of V. fischeri biofilms were compared to coculture biofilms with wild-type Y4I and the igiD::Tn5 mutant. While both Y4I strains were able to inhibit V. fischeri colonization, the wild type inhibited its colonization by 57% ± 14% more than the indigoidine null mutant (P = 0.002). In fact, wild-type Y4I was able to colonize surfaces to a greater extent in the presence of V. fischeri than alone. Conversely, the igiD mutant was impaired in surface colonization when grown with V. fischeri (Fig. 5F). These data provide evidence that indigoidine biosynthesis of surface-attached Y4I cells may provide a significant advantage in the colonization of environmental niches. Biofilms are made of densely packed microcolonies that contain multiple microenvironments (16, 17). Such environments could act to increase the local concentration of indigoidine to levels that would be inhibitory to the growth or attachment of competing organisms.

Regulatory hierarchies are common and complex in bacteria. In multiple species, the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites is primarily controlled by quorum sensing, but environmental factors such as temperature, pH, and nutritional requirements can supersede cell density-dependent regulation (3, 15, 43, 49, 60). As igiD gene expression is elevated in Y4I colonies and biofilms, we hypothesize that both surface attachment and high cell densities are required for indigoidine production: after a surface niche is colonized and quorum is reached, indigoidine biosynthesis is upregulated to suppress the colonization of competing organisms. Studies in TDA-producing Phaeobacter strains have shown biosynthesis occurring at measureable levels in shaking and stagnant broth cultures and on agar plates (22, 44). This is the first report of antimicrobial production by a Roseobacter in response to surface colonization; however, several studies with unclassified marine isolates have shown similar results (31, 56, 61). Furthermore, particle-associated representatives of the Roseobacter clade have been previously demonstrated to be >10 times more likely to produce antimicrobial compounds than free-living members (37).

Antagonistic behavior is widespread throughout the Roseobacter clade and is thought to be due to the synthesis of antimicrobial secondary metabolites, which have been hypothesized to contribute to the success of these organisms in natural systems (6, 8, 10, 12, 26, 27, 37, 38, 44, 51, 58). With the exception of TDA, little is known of the structural and biological nature of these secondary metabolites. We show here that indigoidine production by Phaeobacter sp. strain Y4I is directly related to the inhibition of the model marine bacterium V. fischeri. Moreover, we show that indigoidine biosynthesis is upregulated during growth on a surface and that its production provides a significant advantage to Y4I in competitive surface colonization. Preliminary investigations in our lab have shown that indigoidine-producing strains of Y4I are also able to suppress the growth of V. anguillarum, R. lacuscaerulensis, and Candida albicans, suggesting that indigoidine may act on multiple competing species in the environment (data not shown). The full spectrum of organisms that indigoidine is effective against is not yet realized but may be quite broad. Similarly, the physiological roles of indigoidine production by Phaeobacter spp. likely extend beyond those reported here and might be expected to provide the organism with a competitive advantage in the varied environmental niches it encounters.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Eric Stabb (University of Georgia) for providing us with the Vibrio fischeri strain used in this study. We are also grateful to Mohammad Moniruzzaman for photodocumentation assistance.

Work in our laboratory is supported by the National Science Foundation (OCE-1061352 to A.B.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 May 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler J. 1966. Chemotaxis in bacteria. Science 153:708–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler J. 1973. Method for measuring chemotaxis and use of method to determine optimum conditions for chemotaxis by Escherichia coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 74:77–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnard AML, et al. 2007. Quorum sensing, virulence and secondary metabolite production in plant soft-rotting bacteria. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 362:1165–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger M, Neumann A, Schulz S, Simon M, Brinkhoff T. 2011. Tropodithietic acid production in Phaeobacter gallaeciensis is regulated by N-acyl homoserine lactone-mediated quorum sensing. J. Bacteriol. 193:6576–6585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boettcher KJ, Barber BJ, Singer JT. 2000. Additional evidence that juvenile oyster disease is caused by a member of the Roseobacter group and colonization of nonaffected animals by Stappia stellulata-like strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3924–3930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinkhoff T, et al. 2004. Antibiotic production by a Roseobacter clade-affiliated species from the German Wadden Sea and its antagonistic effects on indigenous isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2560–2565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinkhoff T, Giebel H-A, Simon M. 2008. Diversity, ecology, and genomics of the Roseobacter clade: a short overview. Arch. Microbiol. 189:531–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruhn JB, Gram L, Belas R. 2007. Production of antibacterial compounds and biofilm formation by Roseobacter species are influenced by culture conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:442–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruhn JB, Haagensen JAJ, Bagge-Ravn D, Gram L. 2006. Culture conditions of Roseobacter strain 27-4 affect its attachment and biofilm formation as quantified by real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3011–3015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruhn JB, et al. 2005. Ecology, inhibitory activity, and morphogenesis of a marine antagonistic bacterium belonging to the Roseobacter clade. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:7263–7270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buchan A, Collier LS, Neidle EL, Moran MA. 2000. Key aromatic-ring-cleaving enzyme, protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase, in the ecologically important marine Roseobacter lineage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4662–4672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchan A, Gonzalez JM, Moran MA. 2005. Overview of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5665–5677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buchan A, Neidle EL, Moran MA. 2004. Diverse organization of genes of the beta-ketoadipate pathway in members of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1658–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatterjee AK, Brown MA. 1981. Chromosomal location of the gene (idg) that specifies production of the blue pigment indigoidine in Erwinia chrysanthemi. Curr. Microbiol. 6:269–273 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chin-A-Woeng TFC, Bloemberg GV, Lugtenberg BJJ. 2003. Phenazines and their role in biocontrol by Pseudomonas bacteria. New Phytol. 157:503–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costerton JW, et al. 1987. Bacterial biofilms in nature and disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 41:435–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D'Alvise PW, Melchiorsen J, Porsby CH, Nielsen KF, Gram L. 2010. Inactivation of Vibrio anguillarum by attached and planktonic Roseobacter cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:2366–2370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dang HY, Li TG, Chen MN, Huang GQ. 2008. Cross-ocean distribution of Rhodobacterales bacteria as primary surface colonizers in temperate coastal marine waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:52–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dang HY, Lovell CR. 2000. Bacterial primary colonization and early succession on surfaces in marine waters as determined by amplified rRNA gene restriction analysis and sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:467–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elazari-Volcani 1939. On Pseudomonas indigofera (Voges) Migula and its pigment. Arch. Mikrobiol. 10:343–358 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geng H, Belas R. 2010. Expression of tropodithietic acid biosynthesis is controlled by a novel autoinducer. J. Bacteriol. 192:4377–4387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geng HF, Bruhn JB, Nielsen KF, Gram L, Belas R. 2008. Genetic dissection of tropodithietic acid biosynthesis by marine roseobacters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:1535–1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gherbi H, et al. 2008. From the Cover: SymRK defines a common genetic basis for plant root endosymbioses with arbuscular mycorrhiza fungi, rhizobia, and Frankiabacteria. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 105:4928–4932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottesman S, et al. 1990. Conservation of the regulatory subunit for the Clp ATP-dependent protease in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:3513–3517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gram L, Melchiorsen J, Bruhn JB. 2010. Antibacterial activity of marine culturable bacteria collected from a global sampling of ocean surface waters and surface swabs of marine organisms. Mar. Biotechnol. 12:439–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grossart HP, Schlingloff A, Bernhard M, Simon M, Brinkhoff T. 2004. Antagonistic activity of bacteria isolated from organic aggregates of the German Wadden Sea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 47:387–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harshey RM. 2003. Bacterial motility on a surface: many ways to a common goal. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:249–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellemans J, Mortier G, De Paepe A, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. 2007. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol. 8:R19 doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heumann W, Young D, Gottlich C. 1968. Leucoindigoidine formation by an Arthrobacter species and its oxidation to indigoidine by other micro-organisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 156:429–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.Hjelm M, et al. 2004. Selection and identification of autochthonous potential probiotic bacteria from turbot larvae (Scophthalmus maximus) rearing units. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 27:360–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivanova EP, et al. 1998. Impact of conditions of cultivation and adsorption on antimicrobial activity of marine bacteria. Mar. Biol. 130:545–551 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katayama Y, et al. 1988. The two-component, ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli: purification, cloning, and mutational analysis of the ATP-binding component. J. Biol. Chem. 263:15226–15236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuhn R, Starr MP, Kuhn DA, Bauer H, Knackmus HJ. 1965. Indigoidine and other bacterial pigments related to 3,3′-bipyridyl. Arch. Mikrobiol. 51:71–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lafay B, et al. 1995. Roseobacter algicola sp. nov, a new marine bacterium isolated from the phycosphere of the toxin-producing dinoflagellate Prorocentrum lima. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:290–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larsen RA, Wilson MM, Guss AM, Metcalf WW. 2002. Genetic analysis of pigment biosynthesis in Xanthobacter autotrophicus Py2 using a new, highly efficient transposon mutagenesis system that is functional in a wide variety of bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 178:193–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leriche V, Carpentier B. 1995. Viable but nonculturable Salmonella typhumurium in single-species and binary-species biofilms in response to chlorine treatment. J. Food Prot. 58:1186–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long RA, Azam F. 2001. Antagonistic interactions among marine pelagic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4975–4983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martens T, et al. 2007. Bacteria of the Roseobacter clade show potential for secondary metabolite production. Microb. Ecol. 54:31–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newton RJ, et al. 2010. Genome characteristics of a generalist marine bacterial lineage. ISME J. 4:784–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nieto PA, Covarrubias PC, Jedlicki E, Holmes DS, Quatrini R. 2009. Selection and evaluation of reference genes for improved interrogation of microbial transcriptomes: case study with the extremophile Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. BMC Mol. Biol. 10:63 doi:10.1186/1471-2199-10-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Toole G, Kaplan HB, Kolter R. 2000. Biofilm formation as microbial development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54:49–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Toole GA, et al. 1999. Genetic approaches to the study of biofilms. Methods Enzymol. 310:91–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pierson LS, Pierson EA. 2010. Metabolism and function of phenazines in bacteria: impacts on the behavior of bacteria in the environment and biotechnological processes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 86:1659–1670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Porsby CH, Nielsen KF, Gram L. 2008. Phaeobacter and Ruegeria species of the Roseobacter clade colonize separate niches in a Danish turbot (Scophthalmus maximus)-rearing farm and antagonize Vibrio anguillarum under different growth conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7356–7364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramos I, Dietrich LEP, Price-Whelan A, Newman DK. 2010. Phenazines affect biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in similar ways at various scales. Res. Microbiol. 161:187–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rao D, Webb JS, Kjelleberg S. 2006. Microbial colonization and competition on the marine alga Ulva australis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5547–5555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reverchon S, Nasser W, Robert-Baudouy J. 1994. pecS: a locus controlling pectinase, cellulase and blue pigment production in Erwinia chrysanthemi. Mol. Microbiol. 11:1127–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reverchon S, Rouanet C, Expert D, Nasser W. 2002. Characterization of indigoidine biosynthetic genes in Erwinia chrysanthemi and role of this blue pigment in pathogenicity. J. Bacteriol. 184:654–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruiz B, et al. 2010. Production of microbial secondary metabolites: regulation by the carbon source. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 36:146–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruiz-Ponte C, Cilia V, Lambert C, Nicolas JL. 1998. Roseobacter gallaeciensis sp. nov., a new marine bacterium isolated from rearings and collectors of the scallop Pecten maximus. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:537–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rypien KL, Ward JR, Azam F. 2010. Antagonistic interactions among coral-associated bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 12:28–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seyedsayamdost MR, Case RJ, Kolter R, Clardy J. 2011. The Jekyll-and-Hyde chemistry of Phaeobacter gallaeciensis. Nat. Chem. 3:331–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slightom RN, Buchan A. 2009. Surface colonization by marine Roseobacters: integrating genotype and phenotype. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:6027–6037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Starr MP, Cosens G, Knackmuss H-J. 1966. Formation of the blue pigment indigoidine by phytopathogenic Erwinia. Appl. Microbiol. 14:870–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takahashi H, et al. 2007. Cloning and characterization of a Streptomyces single module type non-ribosomal peptide synthetase catalyzing a blue pigment synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 282:9073–9081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trischman JA, Oeffner RE, de Luna MG, Kazaoka M. 2004. Competitive induction and enhancement of indole and a diketopiperazine in marine bacteria. Mar. Biotechnol. 6:215–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vandecandelaere I, Segaert E, Mollica A, Faimali M, Vandamme P. 2009. Phaeobacter caeruleus sp. nov., a blue-coloured, colony-forming bacterium isolated from a marine electroactive biofilm. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 59:1209–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wagner-Döbler I, Bibel H. 2006. Environmental biology of the marine Roseobacter lineage. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60:255–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y, et al. 2011. Phenazine-1-carboxylic acid promotes bacterial biofilm development via ferrous iron acquisition. J. Bacteriol. 193:3606–3617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williamson NR, Fineran PC, Leeper FJ, Salmond GPC. 2006. The biosynthesis and regulation of bacterial prodiginines. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4:887–899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan L, Boyd KG, Grant Burgess J. 2002. Surface attachment induced production of antimicrobial compounds by marine epiphytic bacteria using modified roller bottle cultivation. Mar. Biotechnol. 4:356–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoon J-H, Kang S-J, Lee S-Y, Oh T-K. 2007. Phaeobacter daeponensis sp. nov., isolated from a tidal flat of the Yellow Sea in Korea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57:856–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.