Abstract

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a halophilic bacterium that is widely distributed in water resources. The bacterium causes lethal food-borne diseases and poses a serious threat to human and animal health all over the world. The major pathogenic factor of V. parahaemolyticus is thermolabile hemolysin (TLH), encoded by the tlh gene, but its toxicity mechanisms are unknown. A high-affinity antibody that can neutralize TLH activity effectively is not available. In this study, we successfully expressed and purified the TLH antigen and discovered a high-affinity antibody to TLH, named scFv-LA3, by phage display screening. Cytotoxicity analysis showed that scFv-LA3 has strong neutralization effects on TLH-induced cell toxicity.

INTRODUCTION

Vibrio parahaemolyticus, a Gram-negative motile bacterium that inhabits marine and estuarine environments throughout the world (7, 23, 36), is a major food-borne pathogen that causes life-threatening diseases in humans through the consumption of raw or undercooked seafood (5, 21, 34). V. parahaemolyticus infection can also occur through open wounds. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported cases of death resulting from wound infections by V. parahaemolyticus in 2005 (15). Given the harmful effects and prevalence of V. parahaemolyticus, it is very important to investigate its pathogenesis.

It is well known that V. parahaemolyticus contains many different kinds of toxins, such as thermostable direct hemolysin (TDH), TDH-related hemolysin (TRH), and some noncharacterized proteins. TDH is considered one of the major virulence factors of V. parahaemolyticus, and its function has been well characterized and discussed (25). TRH is another hemolysin of V. parahaemolyticus that can also lyse red blood cells, and it has high sequence homology with TDH (24, 42). However, identifying the pathogenic serovars of V. parahaemolyticus by use of only these two toxins is not sufficiently accurate, as other hemolysins may take part in the pathogenicity of V. parahaemolyticus. Thermolabile hemolysin (TLH), a toxin encoded by the tlh gene of V. parahaemolyticus and present in almost every clinical and environmental V. parahaemolyticus strain (14, 37), has been suggested as a promising target for pathogen detection (30, 35, 44). Although TLH has hemolytic activity and can lyse red blood cells, its cytotoxic and biochemical mechanisms of action are still not clearly understood (3, 26, 31). Since TLH may be as important as TDH and TRH (6), it is necessary to investigate its function during the process of infection.

Single-chain variable-fragment (scFv) antibody generation is a versatile technology for generating antibodies that are specific for a given antigen (40). It has also been used for selective molecular targeting in cancer research for conditions such as lymphatic invasion vessels, colon cancer, and hepatocarcinoma (27, 29, 33, 43). Furthermore, scFv antibody generation has been used extensively to generate ligands for detecting pathogenic germs in vitro and in vivo (8, 22, 38, 39). Compared to polyclonal antibodies or hybridoma technology, scFv antibodies can easily be manipulated genetically to improve their specificity and affinity, reducing production costs. In addition, they can be fused with molecular markers for immunological detection of pathogenic bacteria (10, 28). scFv antibody generation has also been used extensively in vitro and in animal models to generate ligands and to detect pathogenic germs (8, 22, 38, 39). It has the power to mimic the features of immune diversity and selection, and it is possible to synthesize scFv antibodies in virtually unlimited quantities. Combining scFv antibody generation with selection panning strategies provides a useful tool that allows the selection of antibodies against specific antigens. Using this tool, we have been able to characterize the binding properties of single-chain antibodies and to investigate their potential use as diagnostic tools or therapeutic agents (12, 13).

In the present study, we successfully used phage display screening technology to discover an scFv antibody, named scFv-LA3, that can inhibit the cytotoxicity of TLH. The results demonstrate that phage display technology is a feasible method for generating a specific and high-affinity antibody that could protect against pathogen infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

V. parahaemolyticus strain XM01 (tlh+ tdh+) was generously provided by Xuanxian Peng (Xiamen University, China). V. parahaemolyticus strains CGMCC 1.1615 and CGMCC 1.1616 were purchased from the Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Beijing, China). Other strains were stored in our lab. HeLa, Changliver, and RAW264.7 cells were purchased from the cell bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). BALB/c mice were purchased from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center, and all animal work was performed according to relevant national and international guidelines. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University. DNA restriction enzymes, mRNA isolation kits, and reverse transcription kits were purchased from Promega. Taq DNA polymerase and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from TaKaRa (Dalian, China). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG was purchased from Boster Biological Technology Co. (Wuhan, China). Ampicillins, kanamycin sulfate, bovine serum albumin (BSA), and isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. All oligonucleotides listed in Table 1 and all other reagents used were of analytical reagent grade.

Table 1.

Primer sequences for amplification of the VH, VL, scFv, and tlh genes

| Primer | Direction of primer | Target | Sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|---|---|

| VH1BACK | Upstream | VH | AGG TSM ARC TGC AGS AGT CWG G |

| VH1FOR | Downstream | TGA GGA GAC GGT GAC GGT GGT CCC TTG GCC CC | |

| vk2back | Upstream | VL | GAC ATT GAG CTC ACC CAG TCT CCA |

| MJk1FONX | Downstream | CCG TTT GAT TTC CAG CCT GGT GCC | |

| MJk2FONX | Downstream | CCG TTT TAT TTC CAG CCT GGT GCC | |

| MJk4FONX | Downstream | CCG TTT TAT TTC CAA CCT TGT GCC | |

| MJk5FONX | Downstream | CCG TTT CAG CTC CAG CCT GGT GCC | |

| LINBACK | Upstream | Linker | GGG ACC ACG GTC ACC GTC TCC TCA |

| LINKFOR | Downstream | TGG AGA CTG GGT GAG CTCAAT GTC | |

| VH1BACKsfi | Upstream | scFv | GTC CTC GCA ACT GCG GCC CAG CCG GCC ATG GCC CAG GTS MAR CTG CAG SAG TCW GG |

| JK1NOT10 | Downstream | GAG TCA TTC TCC GGC CGC CCG TTT GAT TTC CAG CTT GGT GCC | |

| JK2NOT10 | Downstream | GAG TCA TTC TGC GGC CGC CCG TTT TAT TTC CAG CTT GGT CCC | |

| JK4NOT10 | Downstream | GAG TCA TTC TGC GGC CGC CCG TTT TAT TTC CAA CTT TGT CCC | |

| JK5NOT10 | Downstream | GAG TCA TTC TGC GGC CGC CCG TTT CAG CTC CAG CTT GGT CCC | |

| Tlh1 | Upstream | tlh | CTG GGA TCC ATG ATG AAA AA |

| Tlh2 | Downstream | CAG AAG CTT GAA ACG GTA CTC |

Expression and purification of recombinant TLH antigen.

The V. parahaemolyticus genome was used as a template to amplify the tlh gene. Primers with BamHI and HindIII restriction enzyme sites were designed for cloning the tlh gene into the pET32a(+) and pET28a(+) vectors, and the identity of the cloned tlh amplicon was verified by sequencing. For protein expression, the recombinant plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 by electroporation, and a single colony from the selection plate was inoculated into 5 ml LB liquid medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin or 50 μg/ml kanamycin. The culture was incubated overnight with shaking at 37°C and then transferred to a larger scale in LB medium (500 μl of culture was transferred to 50 ml of fresh LB). Expression of the target protein was induced by adding 1 mM IPTG when the culture reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8. Cells were grown for an additional 6 h at 28°C and then harvested by centrifugation. Protein purification was performed using Ni2+ affinity chromatography. Expressed and purified proteins were visualized by SDS-PAGE using 12% (vol/vol) polyacrylamide gels, and protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay.

Cell culture and cytotoxicity analysis.

HeLa, Changliver, and RAW264.7 cells were used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of TLH with typical MTT [3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide] and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) methods (1, 41). Briefly, cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin in 96-well plates (triplicate wells) and were adjusted to a final concentration of 106 cells/ml. The purified recombinant TLH protein was sterilized by filtration with a 0.22-μm filter, and TLH proteins of different concentrations (100 μl/well) were added to the wells. BSA was used as a negative control. Plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 h. MTT solution was added to the mixture at a 1:10 ratio (by volume) and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for a further 4 h. Viable cells were evaluated by measuring the conversion of soluble MTT to insoluble blue formazan crystals (41). For FACS analysis, cells were incubated as described above, and test cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated annexin and propidium iodide (PI) (1).

Immunoassay.

Purified TLH was used to immunize four BALB/c mice (100 μg/mouse) four times, at intervals of 20 days, and serum titers were measured by indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Blood from both control and immunized mice was sampled 7 days after the third immunization. Once high serum titers were obtained, animals were sacrificed 5 days after the last immunization, and spleens were collected for immunological assays. Total mRNA was extracted from isolated spleens by use of TRIzol (Promega Biotech).

Construction of a phage-displayed anti-TLH scFv antibody library.

First-strand cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) with reverse transcriptase and random hexadeoxyribonucleotide primers, using the isolated mRNA as a template. The coding sequences for the variable regions of the heavy chain (VH) and light chain (VL) were then amplified from first-strand cDNA through primary PCR amplification. To construct an scFv antibody fragment, a special 93-bp DNA encoding a (Gly4Ser)3 protein sequence was designed as a linker connecting the VH and VL fragments and was also amplified by PCR. The assembly reaction was performed by gene splicing by overlap extension-PCR (SOE-PCR) at a molecular ratio of VH to VL to linker DNA of approximately 3:3:1. Another round of PCR was performed to add SfiI and NotI restriction sites to either end of the scFv antibody fragment for subsequent cloning into the phage plasmid vector pCANTAB-5. The product was then ligated with a precut vector and transformed into E. coli TG1 competent cells by electroporation. To count colonies, 100 μl of diluted transformed cells or untransformed negative-control cells was plated onto SOB-AG plates (SOB medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 2% glucose) and incubated at 30°C overnight. The helper phage M13KO7 was used to rescue the recombinant phagemid. All clones were transferred to a separate tube for phage rescue, and recombinant phage scFv antibody clones were obtained by collecting the supernatants by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C).

Panning of the phage display library.

A 96-well microtiter plate was coated with diluted antigen (2.5 μg/ml) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (100 μl/well) and incubated at 4°C overnight. The plate was then washed three times with PBS and blocked with PBSM (PBS containing 4% nonfat milk). An uncoated (containing only PBS), PBSM-blocked well was set as a control at the same time. To enhance panning efficiency, recombinant phage was precipitated from solution by use of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-NaCl to remove any soluble antibodies that might react with the TLH antigen. The recombinant phage was then diluted and added to a pretreated plate (100 μl/well). After incubation at 37°C for 2 h, the plate was washed 20 times with PBS and then 20 times with PBST (PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20) to remove unbound phage. Phage which reacted with TLH was eluted with 10 ml triethylamine followed by 10 ml of Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) to neutralize the reaction. Eluted phage was used to infect log-phase E. coli TG1 cells, and 10 μl of infected E. coli cells was plated at a 10× serial dilution onto SOB-AG plates for screening of individual colonies.

Screening of clones with binding specificity from enriched clones.

Enriched clones were individually transformed and cultured in a tube with M13KO7 for rescue. To test the specific binding activity by phage ELISA, a 96-well plate was coated with purified TLH antigen at 5 μg/ml in PBS (100 μl/well), followed by blocking with PBSM and subsequent washing. Phage dissolved in PBSM was added to the plate and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. After washing with PBST and PBS, the bound phage was detected with an anti-M13 antibody conjugated to HRP at a 1:4,000 dilution. 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (100 μg/ml) was then used for color development, and the reaction was stopped after 30 min by addition of 2 M H2SO4. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a microplate reader. Binding activity was evaluated by the ratio of values for the sample and the negative control (S/N ratio). An S/N ratio of 2 was used as the cutoff value to indicate positive clones. Specificity analysis of selected anti-TLH clones, such as scFv-LA3, was also performed as described above.

Analysis of anti-TLH scFv-LA3 specificity.

Phage ELISA was performed to determine the specificity of the anti-TLH scFv-LA3 clone. BSA and associated V. parahaemolyticus antigens (TDH, TLH, and YscF) were used to coat 96-well plates in triplicate (5 μg/ml; 100 μl/well). After blocking with PBSM, secreted recombinant phage particles were added to the reaction wells and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The specificity of the scFv-LA3 clone was detected with the anti-M13 HRP-conjugated antibody. The enzyme reaction was then performed with TMB as a substrate, and color development was terminated with 2 M H2SO4 for 30 min. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

Bioinformatics analysis of the scFv gene.

Homology of the sequence of the scFv gene with known murine genes from the GenBank/EMBL and V-Quest databases was determined using BLAST. The scFv-LA3 clone sequence was analyzed using V-Quest IMGT (International ImMunoGeneTics Information System [http://www.imgt.org]) to identify the germ line origin of the VH and VL regions (32).

Soluble expression and affinity determination.

To express the anti-TLH antibody, log-phase HB2151 cells were infected with a positive scFv-LA3 clone and grown in 2× YT-AG medium (YT medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 2% glucose) at 37°C overnight. The culture was then diluted at a ratio of 1:100 in 100 ml fresh 2× YT medium containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin and grown at 37°C until the OD600 reached 0.8. IPTG (1 mM) was added to induce the expression of the scFv clone, and the culture was incubated at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm for 6 h before centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 20 min. To extract the expressed soluble antibody, cell culture pellets were resuspended in 10 ml ice-cold PPB buffer (0.2 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 0.5 mM EDTA; 0.5 M sucrose) and incubated on ice for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 20 min (4°C). The supernatant was carefully discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 2 ml MgSO4 (5 mM) and incubated at 25°C for 10 min. Cell debris was pelleted as described above, and the supernatant was analyzed by ELISA and SDS-PAGE for the presence of soluble antibody. The affinity constant (Kaff) of the scFv clone against TLH was determined using the equation Kaff = (n − 1)/(n[Ab2] − [Ab1]) as described previously (11), where [Ab1] and [Ab2] represent the respective scFv antibody concentrations required to achieve 50% of the maximum absorbance between two different concentrations of coated antigen ([Ag1] = n[Ag2]) and n is the dilution factor between the concentrations of antigen used.

Western blotting.

To further confirm the interactions between scFv-LA3 and the TLH antigen, Western blotting was performed as described by Singh et al. (32), with minor modifications. Briefly, the purified TLH antigen or the total protein of V. parahaemolyticus or another associated bacterium was transferred from an SDS-PAGE gel onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane, and the membrane was treated with soluble scFv antibody by use of a standard protocol. After washing and blocking, the membrane was subsequently incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-E-tag antibody. Signals were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL).

Neutralization of TLH cytotoxicity by scFv antibody.

To evaluate the neutralization ability of the selected scFv-LA3 clone for TLH, HeLa, Changliver, and RAW264.7 cells were treated with TLH for MTT or FACS analysis using standard methods, with minor modifications. Briefly, cells were cultured as described above. TLH (10 μg/ml or 5 μg/ml) and a dilution series of the scFv-LA3 antibody (1010 CFU/ml; 100 ml/well) were added to cells, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 24 h in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. Cells were stained with FITC-conjugated annexin and PI for FACS analysis. Cell viability was determined using the MTT method according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RESULTS

Expression and purification of recombinant TLH antigen.

We used two different expression vectors, pET32a(+) and pET28a(+), to obtain a high yield of TLH. The pET32a(+) vector expressed the N terminus of TLH fused to thioredoxin (TRX) in order to enhance the solubility of expressed TLH. pET28a(+) contained a 6×His tag for protein purification purposes. Protein expression and purification results showed that TLH was highly expressed (Fig. 1). The fusion protein encoded by the pET32a(+) vector was used as an immunogen to immunize BALB/c mice for titer detection, while TLH derived from the pET28a(+) vector was used for cytotoxicity and ELISA analyses.

Fig 1.

Expression of recombinant TLH in E. coli. SDS-PAGE analysis was performed with recombinant TLH expressed by plasmids pET32a(+) (A) and pET28a(+) (B). Lanes: M, protein molecular mass markers; 1, negative control (empty vector); 2, total cell lysate; 3, TLH purified using a Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni2+-NTA) column.

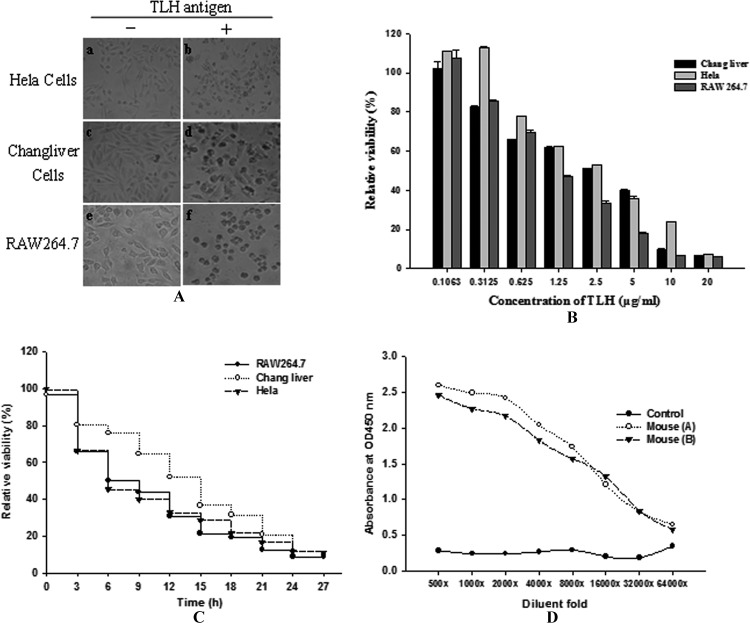

Induction of cytotoxicity and immunization of mice with TLH.

HeLa cells, Changliver cells, and RAW 264.7 macrophages were treated with different concentrations of TLH (0.1 to 20 μg/ml) purified after expression with the pET28a(+) vector. Cells were observed under a microscope after 24 h to evaluate morphological changes, edge atrophy, and cell viability. As shown in Fig. 2A, all three types of cells exhibited signs of severe cytotoxicity, such as round cells, edge atrophy, and cell death, when treated with 2 μg/ml of TLH, and effects were dose and time dependent (Fig. 2B and C). The 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) for HeLa cells, Changliver cells, and RAW 264.7 macrophages were 4.25 μg/ml, 4.75 μg/ml, and 3.99 μg/ml, respectively.

Fig 2.

TLH induces cytotoxicity in cultured cells. (A) HeLa cells (a and b), Changliver cells (c and d), and RAW264.7 cells (e and f) were treated with or without 20 μg/ml TLH. Cell morphology was observed under a microscope and photographed after 24 h. Magnification, ×100. (B) Dose-response analysis of TLH-mediated cytotoxicity. HeLa, Changliver, and RAW264.7 cells were exposed to different concentrations of TLH for 24 h, and cell viability was determined using the MTT assay. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD) for three separate experiments. (C) Time course of TLH-mediated cytotoxicity. HeLa, Changliver, and RAW264.7 cells were incubated with 20 μg/ml of TLH for the indicated times. Cell growth was determined using the MTT assay. (D) Serum titer assay. ELISA was used to determine the serum titer after four immunizations. The serum titer was evaluated by the S/N ratio (signal ≥1.0); the cutoff value for a positive clone was an S/N ratio of ≧2.

To generate an antibody specific to TLH, four female BALB/c mice were immunized with the TLH protein purified from pET32a(+) expression. Mouse serum titers were determined by ELISA (Fig. 2D). Two of the immunized mice had the same anti-TLH titer (1:16,000), indicating that a high-titer anti-TLH antibody was obtained by immunization.

Phage library construction and screening of specific scFvs.

The VH and VL gene fragments encoding the anti-TLH antibody generated from immunized mice were amplified by RT-PCR after isolation of total mRNA from TLH-immunized mouse spleen cells. The 340-bp and 325-bp products were joined by adding a (Gly4Ser)3 linker peptide (∼750 bp in total) (Fig. 3B). An initial phage-displayed scFv antibody library with a size of 3 × 1010 CFU/ml was constructed. The input and output of the library are shown in Fig. 3C. About 3 × 1010 CFU/ml phage clones were used in each panning round, and after the third round, the eluted phage clones were kept at a level of approximately 1 × 106 CFU/ml. To estimate the size of the final library containing potential positive clones more accurately, 54 clones from the eluted phage were selected randomly and identified by PCR and restriction enzyme digestion. Since more than 90% of the recombination clones were positive, we estimated the size of the final recombinant phage-displayed antibody library to be approximately 3 × 106 CFU/ml (Fig. 3C). After six rounds of panning, four scFv antibody clones showing strong binding to the TLH antigen were isolated from the library. The clone with the highest binding activity, scFv-LA3, was selected for further analysis (Fig. 3D).

Fig 3.

Construction of an anti-TLH scFv antibody library. (A) PCR analysis of VH and VL. Lane 1, VH gene (∼340 bp); lane 2, VL gene (∼325 bp); lane M, DL-2000 DNA marker. (B) Amplified fragment of the scFv gene. Lane M, DL-2000 DNA marker; lanes 1 and 2, amplified scFv gene (∼750 bp). (C) Selection of phage scFv antibody library by panning. In each round of panning, the number of input phage was kept constant, at 3.0 × 1010 CFU/ml, and phage that did not bind TLH was removed by washing. The number of phage was counted after each panning round. After three panning rounds, the number of eluted phage was kept constant at 3.0 × 106 CFU/ml. (D) ELISA analysis of the binding activities of four different anti-TLH scFv antibody clones. The graph shows the relationship between OD450 values and TLH concentrations.

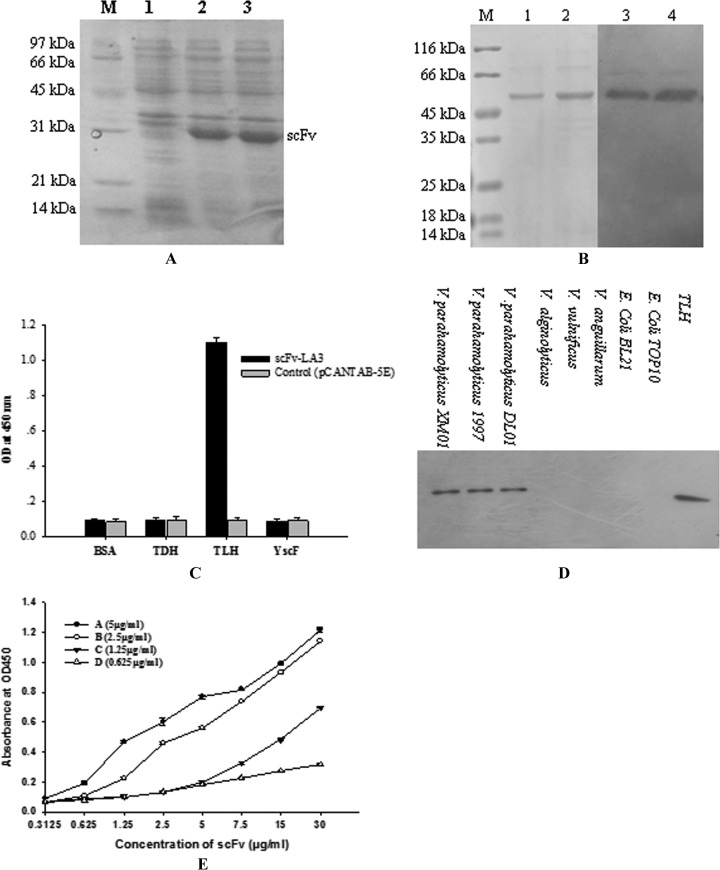

Bioinformatics and biochemical characterization of scFv-LA3.

The scFv-LA3 clone is 735 nucleotides long and encodes 245 amino acids, including a flexible (Gly4Ser)3 linker between VH and VL (Fig. 4A). The three complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of VH and VL were determined according to the method of Kabat et al. (19). Sequence alignment with other mouse germ line genes by use of all available bioinformatics sources (GenBank, RefSeq Nucleotides, EMBL, DDBJ, and PDB databases) confirmed that the VH and VL sequences of scFv-LA3 are mouse antibody variable region genes. Figure 4B and C show IMGT “collier de perle” (pearl necklace) graphical two-dimensional (2-D) representations of scFv-LA3. We expressed the scFv-LA3 antibody in soluble form in infected E. coli HB2151 cells to further characterize its biochemical properties. scFv-LA3 was expressed as an ∼30-kDa protein (Fig. 5A), and its affinity constant for TLH (determined by ELISA) was 5.39 × 108 M−1 (Fig. 5E). scFv-LA3 was found to be specific to TLH; there was no cross binding to any other antigen-associated proteins such as TDH or YscF (Fig. 5B and C). In addition, the Western blotting results derived from Fig. 5D show that the scFv-LA3 antibody is active against Vibrio cells possessing TLH. These results indicate that scFv-LA3 recognizes TLH specifically and can be used as an antibody reagent to detect TLH.

Fig 4.

Molecular characterization of scFv-LA3 clone. (A) Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the scFv-LA3 fragment. Complementarity-determining regions are underlined. (B and C) IMGT collier de perle graphical 2-dimensional representations of the VH (B) and VL (C) regions of scFv-LA3. Asterisks indicate differences between scFv-LA3 and mouse germ line genes. Hydrophobic amino acids (those with positive hydropathy index values, i.e., I, V, L, F, C, M, and A) and tryptophan (W) are shown with gray circles. All proline (P) residues are also shown in gray circles. The CDR IMGT sequences are delimited by amino acids shown in squares (anchor positions), which belong to the neighboring framework region (FR-IMGT). Dotted circles correspond to missing positions according to the IMGT unique numbering. Residues at positions 23, 41, 89, 104, and 118 are conserved.

Fig 5.

Characterization of scFv-LA3. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of expressed scFv-LA3. Lane M, protein marker; lane 1, negative control (empty vector); lanes 2 and 3, expression product of scFv-LA3. (B) Western blot analysis of the binding activity of scFv-LA3 toward the TLH antigen. (Left) SDS-PAGE results for Ni2+-NTA-purified TLH. Lane M, protein molecular mass markers; lanes 1 and 2, purified TLH. (Right) Western blotting results. Lanes 3 and 4, TLH band at 47 kDa bound by scFv-LA3. The bound anti-TLH scFv-LA3 clone was detected using an anti-E-tag HRP-conjugated antibody. (C) scFv-LA3 specifically binds the TLH antigen. *, P < 0.05. BSA and associated antigen proteins (TDH, TLH, and YscF) of Vibrio parahaemolyticus were used to coat 96-well plates in triplicate (5 μg/ml; 100 μl/well). Secreted recombinant phage particles were added to the reaction wells and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Specificity of the scFv-LA3 clone was determined using an anti-M13 HRP-conjugated antibody. (D) Western blotting. The total proteins isolated from tlh-positive and tlh-negative bacterial strains were transferred to a PVDF membrane, and bound anti-TLH scFv-LA3 was detected using an anti-E-tag HRP-conjugated antibody. (E) Binding of scFv-LA3 to different concentrations of TLH antigen as determined by ELISA. The four TLH concentrations were 5 μg/ml (A), 2.5 μg/ml (B), 1.25 μg/ml (C), and 0.625 μg/ml (D).

scFv-LA3 inhibits TLH-induced cytotoxicity.

As shown above, TLH was lethal to several types of cells, and ∼80% to 90% of these cells died when exposed to 10 μg/ml TLH. To test its potential neutralizing effects, scFv-LA3 was added to cells together with TLH. As shown in Fig. 6A and B, scFv-LA3 protected cells from TLH-induced cytotoxicity, in a dose- and time-dependent manner. At the highest dose (∼106 CFU/ml), MTT assays demonstrated that the cytotoxic effects of TLH on cells could be neutralized by scFv-LA3, while the BSA control did not show any protective effects. FACS results also showed that the scFv-LA3 antibody inhibited the cytotoxicity of the TLH antigen and enhanced the viability of cells (Fig. 6C). Taken together, our results demonstrate that scFv-LA3 strongly counteracts TLH-induced cytotoxicity and is a promising candidate for antibody therapy against V. parahaemolyticus infection.

Fig 6.

Neutralizing activity of scFv-LA3. (A) The neutralizing activity of scFv-LA3 for TLH-induced cell toxicity is dose dependent. HeLa, Changliver, and RAW264.7 cells were cultured in triplicate in 96-well flat-bottom plates and treated with 10 μg/ml of TLH, with or without various dilutions of phage scFv-LA3. Cell growth was evaluated using the MTT assay. (B) Time course of scFv-LA3 neutralization. HeLa, Changliver, and RAW264.7 cells were cultured in triplicate in 96-well flat-bottom plates and then treated with 10 μg/ml of TLH and the same concentration of phage scFv-LA3 (1010 CFU/ml) for different lengths of time (at intervals of 3 h) for up to 27 h. Cell growth was evaluated using the MTT assay. Data are presented as means ± SD for three independent experiments. (C) FACS analysis. Changliver and RAW264.7 cells were cultured in triplicate in 6-well flat-bottom plates and treated with 5 μg/ml of TLH and the same concentration of phage scFv-LA3 (1010 CFU/ml). Cells were incubated for 24 h and stained with FITC-conjugated annexin and propidium iodide.

DISCUSSION

Recombinant phage antibodies generated by phage display technology have been used widely to produce powerful reagents for therapeutic and diagnostic purposes (16, 20). Compared to traditional methods that produce antibodies from hybridoma cells, phage display technology exhibits many advantages. First, phage display solves several problems associated with using hybridoma cells, such as a lack of specificity, low antibody titers (32), the need for large-scale culture, and instability of cell lines. Second, it is efficient and has the power to mimic the features of immune diversity and selection (2, 17). Third, phage-displayed antibodies can be manipulated genetically, and the specificity and affinity of each antibody for specific antigens can be enhanced greatly and improved by mutating and rearranging antibody coding genes (4, 9). Finally, the phage ELISA detection method has made phage displays one of the most remarkable technologies for detection of pathogenic bacteria (18, 32, 40).

The assembly of the scFv antibody gene was an important step for scFv antibody library construction. To effectively improve the situation, the molecular ratio of VH, VL, and linker DNAs was adjusted to 3:3:1 to reduce the formation of nonspecific DNA bands and to increase the productivity of scFv antibodies. After a long period of exploration, we finally amplified a better scFv band by PCR. In addition, the linker DNA, containing 93 bp encoding the amino acid linker (Gly4Ser)3, provided sufficient space and allowed suitable flexibility for the VH and VL subunits to interact. It is possible that flexible linkers such as (Gly4Ser)3 improve the folding between the VH and VL subunits and enhance the affinity of scFv antibodies.

In the process of biopanning, we selected four single clones that showed strong binding effects on the TLH antigen, but the scFv-LA3 clone had the highest binding activity. This outcome was attributed to the difference in scFv CDR sequence and the amino acid variation of the antibody scaffold. In addition, in the same case, the fusion expression with PIII tends to interfere with the proper folding of the scFv antibody, and this may also be an important factor affecting the binding activity of scFv antibodies. However, the detailed mechanism of this variation in binding activity needs to be investigated further.

In conclusion, we used phage display technology as a tool to screen for a specific antibody, and the ELISA results show that scFv-LA3 has high binding activity toward TLH. In addition, scFv-LA3 inhibits TLH-induced cytotoxicity and has a protective effect in multiple types of TLH-infected cells. The above results demonstrate that phage display technology is a useful tool for selecting an antibody against a specific antigen. In addition, this tool can be effective at generating therapeutic agents in defense of disease provoked by a pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Xuanxian Peng (Xiamen University, China) for the gift of V. parahaemolyticus strains and Shuhong Luo (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) for helpful discussions and suggestions. We thank Lijun Bi and Fleming Joy (Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for actively revising and editing the manuscript. We thank Bing Wang (Dalian Fisheries University, China) for technical discussions and the gift of Vibrio spp.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 30700535 and 31172297), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (grant NCET-10-0010), the Fujian Fund for Distinguished Young Scientists (grant 2009J06008), the National Agricultural Achievements Transformation Fund (grant 2011GB2C400012), and the Fok Ying Tong Education Foundation (grant 111032).

Rongzhi Wang, Shihua Wang, and Wenxiong Lin conceived and designed the experiments; Rongzhi Wang, Sui Fang, Dinglong Wu, and Junwei Lian performed the experiments; Rongzhi Wang, Jue Fan, and Shihua Wang analyzed the data; and Rongzhi Wang, Yanfeng Zhang, and Shihua Wang wrote the paper.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 May 2012

REFERENCES

- 1.Asano R, et al. 2011. Cytotoxic enhancement of a bispecific diabody by format conversion to tandem single-chain variable fragment (taFv). J. Biol. Chem. 286: 1812–1818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barderas R, et al. 2006. A fast mutagenesis procedure to recover soluble and functional scFvs containing amber stop codons from synthetic and semisynthetic antibody libraries. J. Microbiol. Methods 312: 182–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bej AK, et al. 1999. Detection of total and hemolysin-producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus in shellfish using multiplex PCR amplification of tl, tdh and trh. J. Microbiol. Methods 36: 215–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boder ET, Midelfort KS, Wittrup KD. 2000. Directed evolution of antibody fragments with monovalent femtomolar antigen-binding affinity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97: 10701–10705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bresee JS, Widdowson MA, Monroe SS, Glass RI. 2002. Foodborne viral gastroenteritis: challenges and opportunities. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35: 748–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broberg CA, Calder TJ, Orth K. 2011. Vibrio parahaemolyticus cell biology and pathogenicity determinants. Microbes Infect. 13: 992–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burdette DL, Yarbrough ML, Orvedahl A, Gilpin CJ, Orth K. 2008. Vibrio parahaemolyticus orchestrates a multifaceted host cell infection by induction of autophagy, cell rounding, and then cell lysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105: 12497–12502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cattepoel S, Hanenberg M, Kulic L, Nitsch RM. 2011. Chronic intranasal treatment with an anti-Aβ30-42 scFv antibody ameliorates amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One 6: e18296 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cesaro-Tadic S, et al. 2003. Turnover-based in vitro selection and evolution of biocatalysts from a fully synthetic antibody library. Nat. Biotechnol. 21: 679–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coia G, Hudson PJ, Irving RA. 2001. Protein affinity maturation in vivo using E. coli mutator cells. J. Immunol. Methods 251: 187–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai H, et al. 2003. Construction and characterization of a novel recombinant single-chain variable fragment antibody against white spot syndrome virus from shrimp. J. Immunol. Methods 279: 267–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doppalapudi VR, et al. 2010. Chemical generation of bispecific antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107: 22611–22616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenhardt SU, et al. 2007. Generation of activation-specific human anti-alpha M beta 2 single-chain antibodies as potential diagnostic tools and therapeutic agents. Blood 109: 3521–3528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellison RK, Malnati E, DePaola A, Bowers Rodrick GE. 2001. Populations of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in retail oysters from Florida using two methods. J. Food Prot. 174: 682–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelthaler D, et al. 2005. Vibrio illnesses after Hurricane Katrina—multiple states, August-September 2005. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 54: 928–931 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer R, Emans N. 2000. Molecular farming of pharmaceutical proteins. Transgenic Res. 9: 279–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hmila I, et al. 2008. VHH, bivalent domains and chimeric heavy chain-only antibodies with high neutralizing efficacy for scorpion toxin AahI. Mol. Immunol. 45: 3847–3856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoogenboom HR. 2005. Selecting and screening recombinant antibody libraries. Nat. Biotechnol. 23: 1105–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kabat EA, Wu T, Gottesman KS, Foeller C. 1991. Sequences of proteins of immunological interest. Diane Publishing Co., 5th ed US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanter G, et al. 2007. Cell-free production of scFv fusion proteins: an efficient approach for personalized lymphoma vaccines. Blood 109: 3393–3399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawatsu K, Ishibashi M, Tsukamoto T. 2006. Development and evaluation of a rapid, simple, and sensitive immunochromatographic assay to detect thermostable direct hemolysin produced by Vibrio parahaemolyticus in enrichment cultures of stool specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44: 1821–1827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krag DN, et al. 2006. Selection of tumor-binding ligands in cancer patients with phage display libraries. Cancer Res. 66: 7724–7733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liverman ADB, et al. 2007. Arp2/3-independent assembly of actin by Vibrio type III effector VopL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104: 17117–17122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lynch T, et al. 2005. Vibrio parahaemolyticus disruption of epithelial cell tight junctions occurs independently of toxin production. Infect. Immun. 73: 1275–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuda S, et al. 2010. Association of Vibrio parahaemolyticus thermostable direct hemolysin with lipid rafts is essential for cytotoxicity but not hemolytic activity. Infect. Immun. 78: 603–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers ML, Panicker G, Bej AK. 2003. PCR detection of a newly emerged pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus O3:K6 pathogen in pure cultures and seeded waters from the Gulf of Mexico. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69: 2194–2200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rinderknecht M, Villa A, Ballmer-Hofer K, Neri D, Detmar M. 2010. Phage-derived fully human monoclonal antibody fragments to human vascular endothelial growth factor-C block its interaction with VEGF receptor-2 and 3. PLoS One 5: e11941 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothe A, et al. 2007. Selection of human anti-CD28 scFvs from a T-NHL related scFv library using ribosome display. J. Biotechnol. 130: 448–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakai K, et al. 2010. Isolation and characterization of antibodies against three consecutive Tn-antigen clusters from a phage library displaying human single-chain variable fragments. J. Biochem. 147: 809–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakata J, et al. 2012. Production and characterization of a monoclonal antibody against recombinant thermolabile hemolysin and its application to screen for Vibrio parahaemolyticus contamination in raw seafood. Food Control 23: 171–176 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shinoda S, et al. 1991. Purification and characterization of a lecithin-dependent haemolysin from Escherichia coli transformed by a Vibrio parahaemolyticus gene. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137: 2705–2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh PK, et al. 2010. Construction of a single-chain variable-fragment antibody against the superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin B. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76: 8184–8191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sommaruga S, et al. 2011. Highly efficient production of anti-HER2 scFv antibody variant for targeting breast cancer cells. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 91: 613–621 doi:10.1007/s00253-011-3306-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su YC, Liu C. 2007. Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a concern of seafood safety. Food Microbiol. 24: 549–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taniguchi H, et al. 1990. Cloning and characterization of a gene encoding a new thermostable hemolysin from Vibrio parahaemolyticus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 67: 339–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vora GJ, et al. 2005. Microarray-based detection of genetic heterogeneity, antimicrobial resistance, and the viable but nonculturable state in human pathogenic Vibrio spp. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102: 19109–19114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang RZ, et al. 2011. Detection and identification of Vibrio parahaemolyticus by multiplex PCR and DNA-DNA hybridization on a microarray. J. Genet. Genomics 38: 129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang SH, et al. 2007. Detection of deoxynivalenol based on a single chain fragment variable (scFv) of the antideoxynivalenol antibody. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 272: 214–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang SH, Du XY, Lin L, Huang YM, Wang ZH. 2008. Zearalenone (ZEN) detection by a single chain fragment variable (scFv) antibody. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24: 1681–1685 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang SH, et al. 2006. Construction of single chain variable fragment (ScFv) and BiscFv-alkaline phosphatase fusion protein for detection of Bacillus anthracis. Anal. Chem. 78: 997–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong ASL, et al. 2011. Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation of endophilin B1 is required for induced autophagy in models of Parkinson's disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 13: 568–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu Z, Nybom P, Magnusson KE. 2000. Distinct effects of Vibrio cholerae haemagglutinin/protease on the structure and localization of the tight junction-associated proteins occludin and ZO-1. Cell. Microbiol. 2: 11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang G, Liu Y, Hu H. 2010. Preparation and cytotoxicity effect of anti-hepatocellular carcinoma scFv immunoliposome on hepatocarcinoma cell in vitro. Eur. J. Inflamm. 8: 75–82 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao YG, Tang XQ, Zhan WB. 2011. Cloning, expression, and hemolysis of tdh, trh and tlh genes of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Ocean. Univ. China 10: 275–279 [Google Scholar]