Abstract

In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the catabolite repression control (Crc) protein repressed the formation of the blue pigment pyocyanin in response to a preferred carbon source (succinate) by interacting with phzM mRNA, which encodes a key enzyme in pyocyanin biosynthesis. Crc bound to an extended imperfect recognition sequence that was interrupted by the AUG translation initiation codon.

TEXT

Pyocyanin (PYO), the characteristic blue pigment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, is a redox-active phenazine compound (21) which contributes to the virulence of P. aeruginosa as an opportunistic pathogen and has antibiotic activity against a range of bacteria and fungi. High cell population densities and suboptimal nutrient conditions favor the production of PYO (2, 7, 15, 23). As a typical secondary metabolite, PYO is not essential for growth in vitro but can confer a selective advantage to the producer in the environment (23). At the end of growth on glucose, P. aeruginosa excretes pyruvate (28). Thereafter, in stationary phase, the bacteria can reutilize pyruvate by fermentation in a process that improves their long-term survival (4). PYO appears to be required for pyruvate excretion and lowers the intracellular NADH/NAD+ ratio, suggesting that PYO regulates primary metabolism during a late growth phase (24). Conversely, primary metabolism regulates PYO synthesis. Like others (13, 22), we have observed that a crc mutant lacking carbon catabolite repression control overproduces PYO (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

In Pseudomonas species, preferred carbon sources, such as tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates, cause catabolite repression of degradative pathways for less-preferred substrates (3, 25, 27). Unlike enteric bacteria and Bacillus spp., pseudomonads essentially use a posttranscriptional mechanism to cause catabolite repression of genes involved in the utilization of less-favorable carbon sources, as follows. In the presence of TCA cycle compounds, the activity of the CbrA/CbrB two-component system, which senses the nutritional status, appears to be inhibited (12). The CbrB response regulator, assisted by the alternative sigma factor RpoN, drives the expression of the small RNA (sRNA) CrcZ (1). Thus, P. aeruginosa exhibits high CrcZ concentrations when growing on less-preferred carbon sources (25). CrcZ sequesters the RNA-binding protein Crc (3) and thereby prevents Crc-mediated translational repression of genes involved in the degradation of less-favorable substrates (1, 25, 26, 27). The Crc protein (subunit size, 28.5 kDa) is a global regulator whose structure has not yet been elucidated. Crc recognizes an A-rich ribonucleotide sequence, which we have termed the CA motif (consensus AAnAAnAA, where n is preferentially C or U) and which is typically located near the ribosome binding sites of target mRNAs (17, 18, 19, 26). In Pseudomonas putida, but not in P. aeruginosa, CrcZ is assisted by CrcY, a second Crc-binding sRNA (20).

The CbrA/B-CrcZ-Crc regulatory cascade regulates pyocyanin formation.

To assess carbon catabolite repression of PYO biosynthesis in P. aeruginosa, we initially used a qualitative test on agar plates containing either a minimal medium termed FD (5) or a complex pigment production medium (PPM) (11). Both growth media stimulate phenazine production (5, 11) and were amended with 40 mM succinate, which is known to cause strong catabolite repression in P. aeruginosa (3, 26). On both media, a crc deletion mutant overproduced PYO in comparison with the PYO levels from the wild-type P. aeruginosa PAO1 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In contrast, crcZ, cbrB, and rpoN mutants (Table 1) all produced little PYO (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), suggesting that the CbrA/B-CrcZ-Crc regulatory pathway accounts for the observed differences in pigmentation. Catabolite repression of PYO formation by succinate was confirmed in liquid FD medium; the addition of succinate improved growth yields of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 wild type by about 20% but resulted in a 4-fold reduction of pyocyanin levels at the end of exponential growth (ca. 3 × 109 cells/ml) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s)a | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa strains | ||

| PAO1 | Wild type | ATCC 15692 |

| PAO6358 | ΔrpoN | 9 |

| PAO6673 | Δcrc | 26 |

| PAO6679 | ΔcrcZ | 26 |

| PAO6711 | ΔcbrB | 26 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pME6015 | pVS1-p15A Escherichia coli-Pseudomonas shuttle vector for translational ′lacZ fusions; Tcr | 8 |

| pME9670 | pMMB67HE with crc-His6; Ap/Cbr | 26 |

| pME10011 | phzM′-′lacZ translational fusion: a 695-bp EcoRI-PstI PCR fragment including the first 6 phzM codons was obtained with primers PM9F/PM6R and cloned into pME6015; Tcr | This study |

| pME10012 | pME10011 derivative carrying a mutated upstream CA motif (ΔCA1) obtained with primers PM9F/PM6RL; Tcr | This study |

| pME10013 | pME10011 derivative carrying mutated upstream and downstream CA motifs (ΔCA2) obtained with primers PM9F/PMUD; Tcr | This study |

| pME10014 | pME10011 derivative carrying improved CA motif (ΔCA+) obtained with primers PM9F/PMGA; Tcr | This study |

Ap/Cbr, ampicillin/carbenicillin resistance; Gmr, gentamicin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance.

Translation of phzM is under Crc control.

PYO biosynthesis proceeds in several steps from chorismic acid to phenazine-1-carboxylic acid (PCA), a redox-active yellow pigment with antibiotic properties (15, 23). Like PYO, PCA can facilitate iron uptake by reducing Fe(III) to Fe(II) under reducing conditions (30). The phzABCDEFG operon, which encodes the enzymes of the PYO biosynthetic pathway, including a 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate synthase, has two functional copies in P. aeruginosa. PCA is converted to PYO by the PhzM methyltransferase and subsequently by the PhzS monooxygenase. The single phzM and phzS genes are located upstream and downstream, respectively, of the phzABCDEFG1 operon (14). To find out which steps of the PYO pathway were subject to catabolite repression, we grew the wild type and the crc mutant in liquid PPM amended with succinate and determined PCA and PYO levels in culture supernatants during the transition from exponential growth to stationary phase (ca. 5 × 109 cells/ml) by methods previously described (6, 31). PCA levels were elevated about 1.5-fold in the crc mutant PAO6673 from levels in the wild-type PAO1 and the complemented crc mutant (Table 2). This mild catabolite repression effect was not investigated further. PYO levels were strongly elevated in the crc mutant from those of the wild type and the complemented crc mutant (Table 2). The resulting dramatic shift in the PYO/PCA ratio suggested that the PCA-to-PYO conversion was particularly sensitive to catabolite repression. As the phzM translation initiation region contains a potential CA motif, whereas the phzS gene does not, we included a translational phzM′-′lacZ fusion construct (pME10011) (Table 1) in all strains. In the crcZ, cbrB, and rpoN mutants, the PYO concentration was below detection (Table 2). A ca. 9-fold difference in phzM expression was observed between the low levels in the crcZ, cbrB, and rpoN mutants and the high level in the crc mutant, while an intermediate level was found in the wild type (Table 2). Thus, phzM mRNA appeared to be a target for repression by the Crc protein.

Table 2.

PCA and PYO concentrations in culture supernatants of the wild-type strain PAO1 and mutants affected in carbon catabolite repression controla

| Strainb (genotype) | Cell population density (OD600)c | Concn (μM) ofd: |

PYO/PCA ratio | phzM′-′lacZ expression (Miller units)e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | PYO | ||||

| PAO1 (WT) | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 53 ± 4 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.02 | 276 ± 36 |

| 8.4 ± 0.1 | 78 ± 7 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.01 | 335 ± 31 | |

| PAO6673 (crc) | 6.1 ± 0.1 | 72 ± 12 | 26 ± 4 | 0.36 | 1,391 ± 62 |

| 7.9 ± 0.1 | 103 ± 22 | 26 ± 3 | 0.26 | 1,550 ± 71 | |

| PAO6673/pME9670 (crc complemented) | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 102 ± 9 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.01 | 319 ± 29 |

| 8.3 ± 0.1 | 70 ± 6 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.03 | 384 ± 36 | |

| PAO6679 (crcZ) | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 74 ± 3 | <0.1 | <0.01 | 171 ± 8 |

| 7.6 ± 0.6 | 70 ± 5 | <0.1 | <0.01 | 176 ± 12 | |

| PAO6358 (rpoN) | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 62 ± 5 | <0.1 | <0.01 | 169 ± 15 |

| 6.7 ± 0.4 | 70 ± 5 | <0.1 | <0.01 | 181 ± 16 | |

| PAO6711 (cbrB) | 6.3 ± 0.4 | 59 ± 5 | <0.1 | <0.01 | 188 ± 19 |

| 7.7 ± 0.6 | 55 ± 5 | <0.1 | <0.01 | 160 ± 16 | |

Values are the means and standard deviations (SDs) for triplicate cultures sampled at two time points.

All strains contained plasmid pME10011 (phzM′-′lacZ) and were grown in PPM (22 g tryptone and 5 g KNO3 in 1 liter, pH 7.0) amended with 40 mM succinate. WT, wild type.

OD600, optical density at 600 nm. An OD600 of 1.0 corresponds to ca. 0.6 × 109 CFU/ml.

PCA was extracted from culture supernatants at pH 4 as described previously (6). PYO was extracted at neutral pH with chloroform and then reextracted with 0.1 M HCl as described previously (31).

β-Galactosidase activities specified by pME10011 (in Miller units) were measured by the Miller method (16).

The effects of succinate (a good carbon source), glucose (an intermediate carbon source), and mannitol (a less-preferred carbon source) on the CbrA/B-CrcZ-Crc regulatory cascade have previously been assessed in P. aeruginosa with amiE mRNA (encoding aliphatic amidase) as a target (26). We now repeated this experiment with a translational phzM′-′lacZ fusion as the target in strain PAO1 and found the same regulatory pattern: catabolite repression was strong with succinate, intermediate with glucose, and weak with mannitol (Table 3). Consequently, the PYO/PCA ratio was low with succinate, intermediate with glucose, and high with mannitol (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects of different carbon sources on PCA and PYO production and phzM expressiona

| Supplement to PPMb | Cell population density (OD600) | Concn (μM) ofc: |

PYO/PCA ratio | phzM′-′lacZ expression (Miller units)d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | PYO | ||||

| Succinate | 5.6 ± 0.4 | 36 ± 4 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.03 | 270 ± 28 |

| 7.3 ± 0.7 | 50 ± 5 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.02 | 378 ± 42 | |

| Glucose | 6.0 ± 0.6 | 61 ± 6 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 0.09 | 669 ± 70 |

| 8.4 ± 0.7 | 81 ± 9 | 7.1 ± 0.7 | 0.09 | 880 ± 91 | |

| Mannitol | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 88 ± 9 | 17.3 ± 1.8 | 0.19 | 903 ± 84 |

| 7.8 ± 0.9 | 105 ± 11 | 21.0 ± 2.0 | 0.20 | 1,330 ± 126 | |

Values are the means and standard deviations (SD) for triplicate cultures sampled at two time points.

Strain PAO1 carrying plasmid pME10011 (phzM′-′lacZ) was grown in PPM amended with the listed supplements at 40 mM.

PCA was extracted from culture supernatants at pH 4 as described previously (6). PYO was extracted at neutral pH with chloroform and then reextracted with 0.1 M HCl as described previously (31).

β-Galactosidase activities specified by pME10011 (in Miller units) were measured by the Miller method (16).

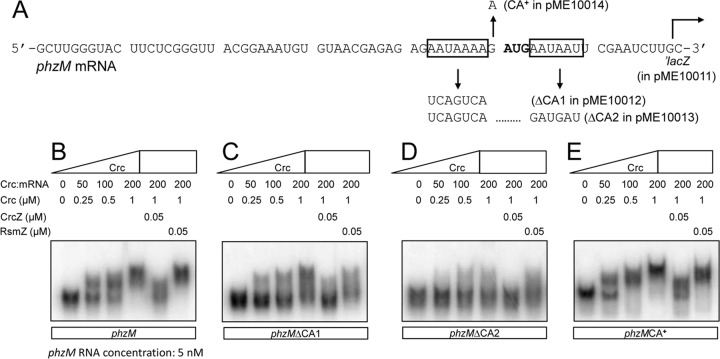

The postulated CA motif of phzM is not contiguous and instead is interrupted by the AUG start codon (Fig. 1A). Thus, instead of an optimal AAnAAnAA motif, there is an extended but imperfect recognition sequence (AAUAAAAGAUGAAUAA; nucleotides deviating from those of an extended consensus are underlined). Interestingly, this mRNA sequence was a good target for the Crc protein, as revealed by two Crc-mRNA complexes in an electrophoretic mobility assay (Fig. 1B). The addition of competing CrcZ sRNA prevented the formation of these complexes, whereas the unrelated RsmZ sRNA (10) had no effect (Fig. 1B). When the upstream part of the CA motif was mutated (designated ΔCA1), only a partial band shift was seen for the highest Crc concentration used (Fig. 1C). When both the upstream and the downstream parts of the CA motif were mutated (designated ΔCA2), Crc hardly interacted with phzM mRNA anymore (Fig. 1D). In contrast, a G-to-A point mutation that created an upstream AAUAAAAA sequence (designated CA+) slightly improved the affinity of phzM mRNA for Crc, as can best be seen from the band shifts with a 100-fold molar excess of Crc over phzM mRNA (Fig. 1B and E). A previous study (26) using amiE mRNA, which contains a conserved Crc-binding site upstream of the AUG start codon, revealed an affinity for Crc that was similar to that of the wild-type phzM transcript. In conclusion, the imperfect Crc recognition sequence in phzM mRNA, which is interrupted by the AUG start codon, still allows effective Crc binding and reflects the structural flexibility that an mRNA target can exhibit toward its protein ligand. This observation also highlights current difficulties in predicting Crc recognition sites solely by sequence inspection.

Fig 1.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay of the Crc-phzM mRNA interaction. (A) The relevant part of the nucleotide sequence of the phzM mRNA is shown. The start codon is highlighted in boldface, and the split CA motif is indicated by two boxes. The mutations shown are followed by designations of the corresponding plasmid constructs. The site of the translational ′lacZ fusion is indicated by an arrow. (B to E) Mobility shift assays, Crc purification, and RNA labeling procedures with [γ-32P]ATP were performed as previously described (25). Increasing amounts of Crc protein (as indicated) were added to 5 nM 5′-end-labeled phzM (B), phzMΔCA1 (C), phzMΔCA2 (D), or phzMCA+ (E) mRNA. The phzM wild-type and mutant mRNAs are truncated and consist of the first 288 nucleotides (nt) of the transcript. RNAs were transcribed in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase (Epicentre) and PCR fragments as templates, amplified with T7MF as the forward primer and PM6R (phzM), PM6RL (phzMΔCA1), PMUD (phzMΔCA2), or PMGA (phzMCA+) as the reverse primer (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Nonlabeled CrcZ or RsmZ RNA was added at 100 nM to show that CrcZ, but not the unrelated RsmZ sRNA, can remove Crc from phzM mRNA.

We then measured the effects of the modified CA motifs on the expression of the translational phzM′-′lacZ fusion in vivo (Table 4). The β-galactosidase activities were in agreement with the results of the Crc-binding assays; in particular, the ΔCA2 mutations abolished regulation by CrcZ and Crc entirely (Table 4). With these experiments, we have confirmed that the CbrAB-CrcZ-Crc cascade regulates PYO expression at the level of phzM mRNA.

Table 4.

Catabolite repression of phzM translational expression: effects of mutations in the CA motif of the phzM translation initiation region

| Plasmid | Straina | Cell population density (OD600)b | phzM′-′lacZ expression (Miller units)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| pME10011 (wild-type phzM′-′lacZ) | PAO1 (wild type) | 6.8 ± 0.4 | 428 ± 39 |

| PAO6673 (Δcrc) | 7.0 ± 0.5 | 2,227 ± 150 | |

| PAO6679 (ΔcrcZ) | 6.6 ± 0.2 | 267 ± 22 | |

| pME10012 (CA1 motif mutated) | PAO1 (wild type) | 6.4 ± 0.3 | 171 ± 16 |

| PAO6673 (Δcrc) | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 293 ± 13 | |

| PAO6679 (ΔcrcZ) | 6.3 ± 0.4 | 214 ± 20 | |

| pME10013 (CA1 and CA2 motifs mutated) | PAO1 (wild type) | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 221 ± 20 |

| PAO6673 (Δcrc) | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 219 ± 20 | |

| PAO6679 (ΔcrcZ) | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 222 ± 19 | |

| pME10014 (improved CA1 motif) | PAO1 (wild type) | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 320 ± 27 |

| PAO6673 (Δcrc) | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 680 ± 60 | |

| PAO6679 (ΔcrcZ) | 7.0 ± 0.4 | 60 ± 5 |

Strains were grown in PPM amended with 40 mM succinate.

β-Galactosidase values are means and standard deviation (SD) for triplicate cultures.

In conclusion, preferred carbon sources, such as succinate, are used by P. aeruginosa for efficient energy generation and rapid growth. Under these conditions, it makes sense to repress the formation of pyocyanin, whose physiological functions are displayed predominantly during restricted growth and in the stationary phase (23). To what extent PCA, which continues to be produced under catabolite repression conditions, can functionally replace PYO remains to be seen. Interestingly, the inhibitory action of honey on PYO formation in P. aeruginosa can at least partially be ascribed to catabolite repression exerted by sugar molecules (29).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Sino-Swiss Science and Technology Cooperation Program (SSSTC) and Shanghai Jiaotong University for Exchange PhD Students grants (to J.H.), the Swiss National Science Foundation, the National Key Basic Research Program (973 Program, no. 2009CB118906) of the People's Republic of China, and the Hertha-Firnberg Program (research fellowship T448-B20 from the Austrian Science Fund to E.S.) for support.

We thank Karine Lapouge and Cornelia Reimmann for stimulating discussion and for help in this project.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 4 May 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdou L, Chou H-T, Haas D, Lu C-D. 2011. Promoter recognition and activation by the global response regulator CbrB in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 193: 2784–2792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Britigan BE, Rasmussen GT, Cox CD. 1997. Augmentation of oxidant injury to human pulmonary epithelial cells by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa siderophore pyochelin. Infect. Immun. 65: 1071–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collier DN, Hager PW, Phibbs PV., Jr 1996. Catabolite repression control in the pseudomonads. Res. Microbiol. 147: 551–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eschbach M, et al. 2004. Long-term anaerobic survival of the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa via pyruvate fermentation. J. Bacteriol. 186: 4596–4604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank LH, DeMoss RD. 1959. On the biosynthesis of pyocyanine. J. Bacteriol. 77: 776–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ge Y, Huang X, Wang S, Zhang X, Xu Y. 2004. Phenazine-1-carboxylic acid is negatively regulated and pyoluteorin positively regulated by gacA in Pseudomonas sp. M18. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 237: 41–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassan HM, Fridovich I. 1980. Mechanism of the antibiotic action of pyocyanine. J. Bacteriol. 141: 156–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heeb S, Blumer C, Haas D. 2002. Regulatory RNA as mediator in GacA/RsmA-dependent global control of exoproduct formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0. J. Bacteriol. 184: 1046–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heurlier K, Dénervaud V, Pessi G, Reimmann C, Haas D. 2003. Negative control of quorum sensing by RpoN (σ54) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 185: 2227–2235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heurlier K, et al. 2004. Positive control of swarming, rhamnolipid synthesis, and lipase production by the posttranscriptional RsmA/RsmZ system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 186: 2936–2945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang J, et al. 2009. Temperature-dependent expression of phzM and its regulatory genes lasI and ptsP in rhizosphere isolate Pseudomonas sp. strain M18. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75: 6568–6580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Itoh Y, Nishijyo T, Nakada Y. 2007. Histidine catabolism and catabolic regulation, p 371–395 In Ramos J-L, Filloux A. (ed), Pseudomonas—a model system in biology, vol 5 Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linares JF, et al. 2010. The global regulator Crc modulates metabolism, susceptibility to antibiotics and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Microbiol. 12: 3196–3212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mavrodi DV, et al. 2001. Functional analysis of genes for biosynthesis of pyocyanin and phenazine-1-carboxamide from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 183: 6454–6465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mavrodi DV, Blankenfeldt W, Thomashow LS. 2006. Phenazine compounds in fluorescent Pseudomonas spp. biosynthesis and regulation. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44: 417–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreno R, Ruiz-Manzano A, Yuste L, Rojo F. 2007. The Pseudomonas putida Crc global regulator is an RNA binding protein that inhibits translation of the AlkS transcriptional regulator. Mol. Microbiol. 64: 665–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moreno R, Marzi S, Romby P, Rojo F. 2009. The Crc global regulator binds to an unpaired A-rich motif at the Pseudomonas putida alkS mRNA coding sequence and inhibits translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 37: 7678–7690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno R, Fonseca P, Rojo F. 2010. The Crc global regulator inhibits the Pseudomonas putida pWW0 toluene/xylene assimilation pathway by repressing translation of regulatory and structural genes. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 24412–24419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno R, Fonseca P, Rojo F. 2012. Two small RNAs, CrcY and CrcZ, act in concert to sequester the Crc global regulator in Pseudomonas putida, modulating catabolite repression. Mol. Microbiol. 83: 24–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison MA, Seo ET, Howie JK, Sawyer DT. 1978. Flavin model systems. 1. The electrochemistry of 1-hydroxyphenazine and pyocyanine in aprotic solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 100: 207–211 [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Toole GA, Gibbs KA, Hager PW, Phibbs PV, Jr, Kolter R. 2000. The global carbon metabolism regulator Crc is a component of a signal transduction pathway required for biofilm development by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 182: 425–431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price-Whelan A, Dietrich LE, Newman DK. 2006. Rethinking ‘secondary’ metabolism: physiological roles for phenazine antibiotics. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2: 71–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Price-Whelan A, Dietrich LE, Newman DK. 2007. Pyocyanin alters redox homeostasis and carbon flux through central metabolic pathways in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 189: 6372–6381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rojo F. 2010. Carbon catabolite repression in Pseudomonas: optimizing metabolic versatility and the interaction with the environment. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35: 753–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonnleitner E, Abdou L, Haas D. 2009. Small RNA as global regulator of carbon catabolite repression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106: 21866–21871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonnleitner E, Haas D. 2011. Small RNAs as regulators of primary and secondary metabolism in Pseudomonas species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 91: 63–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Von Tigerstrom M, Campbell JJR. 1966. The accumulation of α-ketoglutarate by suspensions of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can. J. Microbiol. 12: 1005–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang R, Starkey M, Hazan R, Rahme LG. 2012. Honey's ability to counter bacterial infections arises from both bactericidal compounds and QS inhibition. Frontiers Microbiol. 3: 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, et al. 2011. Phenazine-1-carboxylic acid promotes bacterial biofilm development via ferrous iron acquisition. J. Bacteriol. 193: 3606–3617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu H, et al. 2005. Influence of ptsP gene on pyocyanin production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 253: 103–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.