Abstract

Propionate is one of the major intermediary products in the anaerobic decomposition of organic matter in wetlands and paddy fields. Under methanogenic conditions, propionate is decomposed through syntrophic interaction between proton-reducing and propionate-oxidizing bacteria and H2-consuming methanogens. Temperature is an important environmental regulator; yet its effect on syntrophic propionate oxidation has been poorly understood. In the present study, we investigated the syntrophic oxidation of propionate in a rice field soil at 15°C and 30°C. [U-13C]propionate (99 atom%) was applied to anoxic soil slurries, and the bacteria and archaea assimilating 13C were traced by DNA-based stable isotope probing. Syntrophobacter spp., Pelotomaculum spp., and Smithella spp. were found significantly incorporating 13C into their nucleic acids after [13C]propionate incubation at 30°C. The activity of Smithella spp. increased in the later stage, and concurrently that of Syntrophomonas spp. increased. Aceticlastic Methanosaetaceae and hydrogenotrophic Methanomicrobiales and Methanocellales acted as methanogenic partners at 30°C. Syntrophic oxidation of propionate also occurred actively at 15°C. Syntrophobacter spp. were significantly labeled with 13C, whereas Pelotomaculum spp. were less active at this temperature. In addition, Methanomicrobiales, Methanocellales, and Methanosarcinaceae dominated the methanogenic community, while Methanosaetaceae decreased. Collectively, temperature markedly influenced the activity and community structure of syntrophic guilds degrading propionate in the rice field soil. Interestingly, Geobacter spp. and some other anaerobic organisms like Rhodocyclaceae, Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Thermomicrobia probably also assimilated propionate-derived 13C. The mechanisms for the involvement of these organisms remain unclear.

INTRODUCTION

Temperature is one of the most important factors influencing microbial activity in the environment. In paddy fields and wetlands, it has been well demonstrated that the increase of temperature in summer substantially increases CH4 production and emission (8, 40, 45). Culture-independent investigations reveal that not only the methanogenic activity but also the composition of methanogen community shifts when temperature changes (3). Our previous work revealed that Bacteroidetes and Chlorobi became abundant with time during the decomposition of plant residues at 15°C and 30°C, whereas Acidobacteria dominated at 45°C (32). Among the archaeal populations, Methanosarcinaceae and Methanosaetaceae were favored at 15°C and 30°C, respectively, whereas hydrogenotrophic Methanocellales and Methanobacteriales were selected at 45°C (29). This temperature-dependent differentiation of bacterial and archaeal communities may even result in a change of methanogenic pathway, i.e., from the prevalence of aceticlastic methanogenesis to hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, with the increase of temperature (3, 6, 7). Apparently, temperature influences strongly the structure and function of microbial communities in rice field soil.

The microbial community degrading organic residues in anoxic soil comprises primary fermenters, secondary fermenters, hydrogen-utilizing acetogens, and methanogens (5, 36, 46). The intermediary fatty acids and alcohols produced can accumulate up to 25 mM for acetate and 10 mM for propionate and butyrate during the degradation of plant residues (9, 32). These fatty acids are then degraded to less than 1 mM, reaching a quasi-steady state. Acetate is a direct substrate for many anaerobes including methanogens. The degradation of other fatty acids like propionate and butyrate, however, is thermodynamically difficult and can be carried out only through the syntrophic interaction between proton-reducing and fatty acid-oxidizing syntrophs and H2-consuming methanogens (34, 37, 42). A pioneering work on rice field soil revealed that all types of known syntrophs including Syntrophobacter spp., Pelotomaculum spp., and Smithella spp. were involved in syntrophic oxidation of propionate (23). However, very little is known on the effect of environmental factors like temperature on syntrophic interactions (27). Furthermore, a few recent studies revealed that not only known syntrophic bacteria but also novel species might be involved in the syntrophic degradation of fatty acids like acetate and butyrate in the rice field soils (18, 19, 33). Therefore, the ecology of syntrophs is still far from understood.

The objectives of the present study were to identify the syntrophs involved in the oxidation of propionate in a Chinese paddy field soil at 15°C and 30°C. These temperatures represent a low and middle temperature covering most periods of the rice growth season in the Yangtze River delta plain of China, where rice is widely cultivated. DNA-based stable isotope probing (SIP) was applied to identify the organisms assimilating propionate-derived C during its oxidation in soil. Our results revealed that syntrophic oxidation of propionate occurred at both temperatures, but the community structure of syntrophic guilds shifted depending on temperature.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Soil sample and anoxic incubation.

A soil sample was collected from the experimental farm field at the China National Rice Research Institute in Hangzhou, China (30°04′37″N, 119°54′37″E). The soil was a clay loam and had the following characteristics as measured by standard methods (28) (per kg of soil): pH 6.7, cation exchange capacity of 14.4 cmol, organic C of 24.2 g, and total N of 2.3 g. Soil was air dried and passed through 2-mm sieves to homogenize the sample. In Asian countries, irrigated rice fields are often subjected to dryness (drainage) during the maturing stage of rice plants, harvest time, and fallow period. Thus, air drying and reconstruction of anoxic conditions in the present experiment would not alter the basic properties of rice field soil. Three grams of soil sample were mixed with 3 ml of sterile anoxic water in 10-ml serum vials. The vials were sealed with sterile rubber septa, and the headspaces were flushed with pure N2 for 5 min. The vials were separated into two groups for separate incubations at 15°C and 30°C. To create the conditions for syntrophic interaction between propionate syntrophs and methanogens, soil slurries were preincubated (prior to addition of propionate) in the dark, one group at 15°C for 58 days and the other at 30°C for 34 days. This preincubation allowed the activation of the methanogenic microbial community and the reduction of alternative electron acceptors like iron(III) and sulfate in soil. [U-13C]propionate (99 atom%; Sigma-Aldrich) was added at 0, 18, 34, and 46 days (after the preincubation) for the incubation at 30°C and at 0 and 36 days for the incubation at 15°C (each time to a final concentration of 10 mM in soil slurries). A parallel set of incubation vials amended with nonlabeled propionate were prepared as controls. The incubations were carried out in triplicate.

Gas analysis.

After every 3 to 4 days, gases in the headspace were sampled for the analyses of total concentration and 13C/12C ratios of CH4 and CO2 according to methods described previously (19).

Nucleic acid extraction and gradient centrifugation.

Soil slurry samples were destructively sampled at days 34 and 60 from the incubation at 30°C and at days 36 and 69 from the incubation at 15°C. Soil slurries were mixed thoroughly and centrifuged at 3,800 × g for 15 min. The sedimented soil was used for extraction of microbial DNA according to a cell lysis protocol involving bead beating in the presence of TNS buffer (0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 M NaCl, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate [wt/vol]) and phosphate buffer (112.9 mM Na2HPO4, 7.12 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8.0) (29). DNA extracts were purified, quantified, and stored at −20°C following a procedure described previously (30, 31).

Density gradient centrifugation was performed following a previously described protocol (21, 31). Briefly, centrifugation medium was prepared by mixing 5.0 ml of 2.0 g ml−1 cesium trifluoroacetate (CsTFA) (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), 3.9 ml of gradient buffer (GB) (0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 8], 0.1 M KCl, 1 mM EDTA), and up to 2.5 μg of nucleic acid extracts. Prior to centrifugation, the average density of mixtures was determined by an AR200 digital refractometer (Reichert) and adjusted if necessary with small volumes of CsTFA solution or gradient buffer. Samples were transferred to 8.9-ml polyallomer UltraCrimp tubes and spun in a Ti90 vertical rotor (Beckman) at 177,000 × g at 20°C for >36 h, using a Beckman Optima 2-80XP ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Density gradient DNA was fractionated, and the buoyant density (BD) of each fraction was determined by refractometer (21, 24). DNA was precipitated from gradient fractions by isopropanol, and the pellets were resuspended in 30 μl elution buffer for subsequent community analyses.

Community analyses.

Bacterial and archaeal communities in density-resolved DNA were PCR amplified and analyzed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) and cloning and sequencing. PCR amplification used primer pairs Ba27f-FAM/Ba907r for bacteria and Ar109f/Ar934r for archaea (23, 24). For T-RFLP analysis, the Ba27f and Ar934r primers were labeled with 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM). PCR mixtures (50 μl) contained the following components: 1 μl of DNA template (in 1:10 dilution of original extracts), 5 μl of 10× buffers (TakaRa), 3 μl of 25 mM MgCl2 (TakaRa), 4 μl of 2.5 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) (TakaRa), 0.5 μl of each 50 μM primer (Sangon), and 2.5 U Taq DNA polymerase (TakaRa). The thermal profile for bacterial amplification was 1 min at 94°C; 28 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 45 s at 52.5°C, and 80 s at 72°C; and finally 10 min at 72°C. The thermal profile for archaeal amplification was 3 min at 94°C; 32 cycles of 60 s at 94°C, 45 s at 52°C, and 90 s at 72°C; and finally 5 min at 72°C. The PCR products were purified and digested by MspI (TaKaRa) for bacteria and TaqI (TaKaRa) for archaea. The digestion products were then size separated by the 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) following a protocol described previously (31, 32). For bacteria, the original electropherograms were presented, while for archaea the percent relative abundance of individual T-RFs was calculated relative to the total fluorescence intensity of all T-RFs. The data presented were from one replicate, although the incubation experiment was carried out in triplicate and the SIP procedure was performed in duplicate. Similar T-RFLP profiles were obtained from duplicates. However, we did not attempt to average the data because the DNA gradient density could vary slightly between samples.

Bacterial and archaeal clone libraries were constructed from representative DNA of “heavy” and “light” gradient fractions. PCR was performed as described above without FAM labeling. PCR products were purified and ligated into the pMD19-T vector (TaKaRa) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli cells, and the randomly selected clones were sequenced with an ABI 3730xl sequencer using BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing chemistry (Applied Biosystems) (29, 32). The sequence data were analyzed using the ARB software package (http://www.arb-home.de) (22). The 16S rRNA gene sequences were aligned and integrated into the ARB database. Some sequence data from the GenBank database were imported to include the closest matches in ARB database. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm as described previously (29, 32).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The partial 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers FM956116 to FM956389 for the bacterial sequences and FR865192 to FR865391 for the archaeal sequences.

RESULTS

Methane production from propionate oxidation.

Soil slurries were preincubated to reduce alternative electron acceptors, other than CO2. In the preincubation at 30°C, CH4 production increased rapidly from day 10 and reached a stable rate between day 23 and day 34 (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). This pattern of methanogenesis was consistent with our previous studies (43, 44) indicating that most of the electron acceptors other than CO2 were reduced in 10 days and CH4 production reached a quasi-steady state about 3 weeks after anaerobic incubation. Methane production in the preincubation at 15°C was slower, with cumulative CH4 production approximately 1 order of magnitude lower than at 30°C.

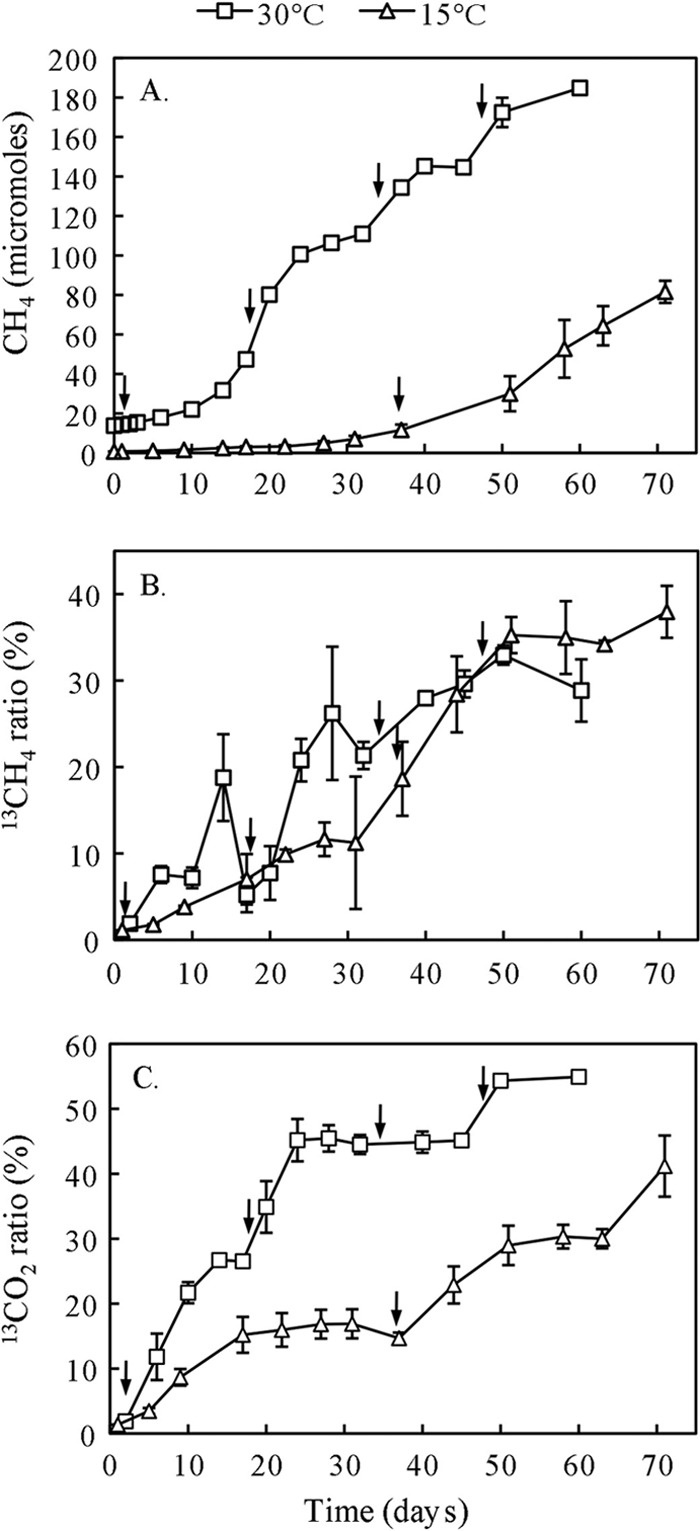

At the end of preincubation, propionate was added to a concentration of 10 mM in soil slurries. A new dosage of the same amount was added when the CH4 concentration stopped increasing or the 13C/12C ratio decreased. In total, propionate was added four times (at days 0, 18, 34, and 46) for the incubation at 30°C and twice (at days 0 and 36) for the incubation at 15°C. Each addition of propionate resulted in a rapid increase of CH4 production at 30°C (Fig. 1A). CH4 production, however, remained low at 15°C with an obvious increase observed only after the second addition of propionate.

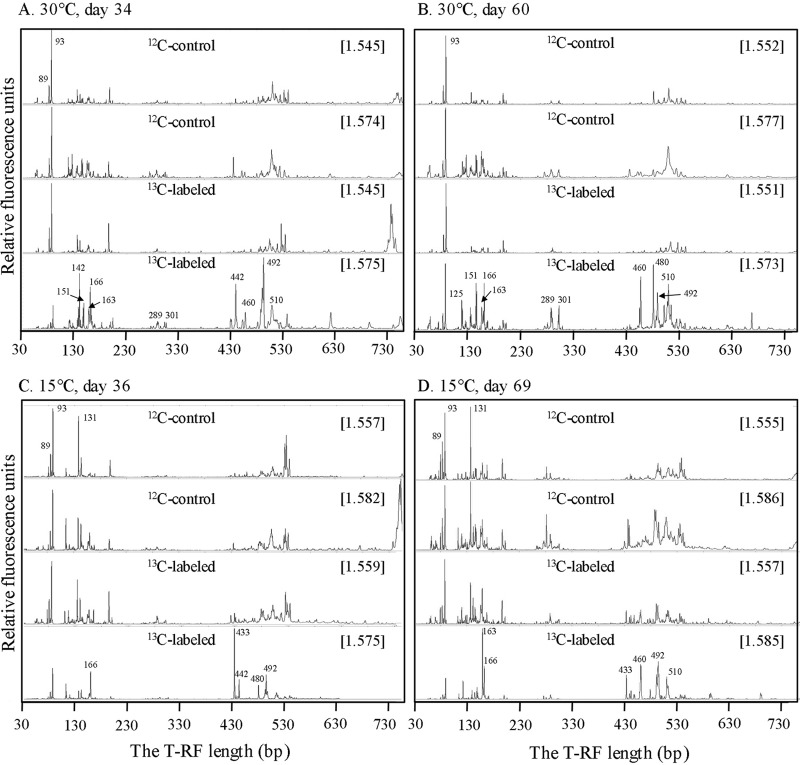

Fig 1.

Time course of CH4 (A), the 13C atom% of CH4 (B), and the 13C atom% of CO2 (C) during the syntrophic propionate oxidation in the rice field soil. The anaerobic incubations were carried out at 15°C and 30°C, respectively. Arrows indicate the time points of [13C]propionate addition. Data are means ± standard errors (n = 3).

The 13C atom% of CH4 increased rapidly after the addition of [13C]propionate both at 30°C and at 15°C (Fig. 1B). Despite a low production rate of CH4 at 15°C, the 13C atom% of CH4 was similar to that at 30°C, being about 30% at the end of incubation. The 13C atom% of CO2 also increased with time, reaching higher values at 30°C than 15°C (Fig. 1C). Based on the total concentration and 13C/12C ratio of CH4, the amounts of 13CH4 produced from propionate oxidation were estimated to be 58.8 μmol at 30°C and 30.8 μmol at 15°C, corresponding to 27% and 29% of the expected amounts from stoichiometric calculation.

T-RFLP fingerprints of density-resolved bacteria.

Comparative DNA-SIP was performed for the 13C-labeled samples and controls receiving propionate without 13C labeling. Density-resolved fractionation of total DNA of the labeled samples and nonlabeled controls displayed similar distribution patterns along buoyant density gradients (see Fig. S2 and S3 in the supplemental material). This similarity possibly indicated that (i) syntrophs were metabolically active but grew slowly and (ii) the incubation did not yield significant enrichment despite multiple applications of propionate, and hence the syntrophs and methanogens in combination occupied only a small proportion of total microbial biomass (or DNA) in the soil.

Nevertheless, differential 13C labeling of microbes was resolved by T-RFLP fingerprinting. T-RFLP patterns from the labeled treatments changed substantially with the buoyant density of DNA. Particularly, several T-RFs (depending on sample origins) were enriched in the heavy DNA gradient fractions (see Fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material). In contrast, T-RFLP patterns from the control soils did not differ significantly among BD fractions. This differential patterning of T-RFLP profiles suggested that a group of organisms had incorporated sufficient amounts of 13C into their nucleic acids, allowing the SIP-based detection.

Temperature and time of incubation influenced the T-RFLP pattern of the density-resolved DNA. For the incubation at 30°C, DNA collected at day 34 (Fig. 2A) showed eight T-RFs (here designated by their sizes, i.e., 142, 151, 163, 166, 442, 460, 492, and 510 bp) enriched in the heavy DNA fractions (BD, 1.575 g ml−1). The day 60 sample still showed the enrichment of 151, 163, 166, 460, 492, and 510 bp in the heavy fractions (BD, 1.573 g ml−1) (Fig. 2B), but the enrichment of 142 and 442 bp decreased, and that of 125 and 480 bp, which was absent at day 34, increased at day 60. In addition, enrichment of 289 and 301 bp substantially increased in the later stage. T-RFLP patterns of the lighter fractions were dominated by 93 and 89 bp and did not differ between day 34 and day 60 and from the nonlabeled control (Fig. 2A and B). For the incubation at 15°C, DNA retrieved at day 36 (Fig. 2C) showed the enrichment of 166, 433, 442, 480, and 492 bp in heavy fractions (BD, 1.575 g ml−1). At the later stage (day 69), 166 and 433 bp still remained enriched in heavy fractions (BD, 1.585 g ml−1) (Fig. 2D), but enrichment of 442 bp decreased, while that of 163, 460, and 510 bp markedly increased. The comparison between results at 30°C and 15°C indicated that enrichment of 142 and 151 bp decreased and that of 433 bp increased in the heavy fractions at 15°C. In consistency with 30°C samples, T-RFLP patterns of the nonlabeled controls at 15°C also did not change with BD fractions. However, 131 bp showed substantial increase at 15°C compared with 30°C (Fig. 2C and D).

Fig 2.

T-RFLP fingerprints of the bacterial 16S rRNA genes retrieved from the density-resolved DNA from incubations at 30°C on day 34 (A), 30°C on day 60 (B), 15°C on day 36 (C), and 15°C on day 69 (D). A light and a heavy representative gradient fractions are presented for each control and 13C-labeling treatment. The relative fluorescence units indicate the arbitrary fluorescence intensity in each electropherogram. The complete set of T-RFLP profiles along DNA density gradients can be found in the supplemental material (Fig. S4 and S5). The numbers close to the peaks denote the T-RF length. The CsTFA buoyant densities (g ml−1) of the DNA fractions are shown in brackets.

Clone libraries of density-resolved bacteria.

Four bacterial clone libraries were constructed from representative light and heavy DNA gradient fractions (Table 1). Analysis of 274 bacterial sequences indicated that the bacterial community in the soil comprised mainly Deltaproteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Thermomicrobia, Firmicutes, Betaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Chlorobi (Table 1). Other bacteria, from Gammaproteobacteria, Gemmatimonadales, Nitrospirae, Verrucomicrobia, Planctomycetes, and unclassified lineages, showed smaller abundances. The comparison between light and heavy clone libraries revealed that the light DNA was dominated by the sequences affiliated with Bacteroidetes, Acidobacteria, and Thermomicrobia, whereas the sequences related to Deltaproteobacteria (mainly Syntrophobacter, Geobacter, and Syntrophus), Firmicutes (mainly Pelotomaculum and Syntrophomonas), Betaproteobacteria (Rhodocyclaceae), and Chlorobi were enriched in the heavy clone libraries. The phylogenetic relationships for the sequences affiliated within the Deltaproteobacteria and Firmicutes are presented in Fig. 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 1.

Phylogenetic affiliations and numbers of bacterial 16S rRNA gene clones retrieved in libraries generated from density-resolved nucleic acids collected at different times from incubations at 15 and 30°C

| Phylogenetic group | No. of clones retrieved |

T-RF length(s) of clones (bp)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30°C, day 34, light gradient | 30°C, day 34, heavy gradient | 30°C, day 60, heavy gradient | 15°C, day 69, heavy gradient | ||

| Alphaproteobacteria | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | |

| Bradyrhizobiaceae | 3 | 152 | |||

| Rhodospirillaceae | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 150, 442, 457 |

| Caulobacterales | 1 | 148 | |||

| Rhizobiales | 1 | 160 | |||

| Unknown | 1 | 439 | |||

| Betaproteobacteria | 2 | 12 | 5 | 4 | |

| Burkholderiales | 2 | 1 | 483, 492 | ||

| Rhodocyclaceae | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 77, 430, 432, 480, 486, 492 |

| Nitrosomonadales | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 123 |

| Methylophilaceae | 1 | 114 | |||

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 65, 475 | ||

| Gammaproteobacteria | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Methylococcaceae | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 455, 457 |

| Xanthomonadales | 1 | 178 | |||

| Thiotrichales | 1 | 143 | |||

| Unknown | 1 | 498 | |||

| Deltaproteobacteria | 9 | 15 | 13 | 13 | |

| Desulfobacterales | 1 | 2 | 70, 82, 162 | ||

| Desulfuromonadales | 3 | 4 | 8 | 160, 161, 163, 507 | |

| Synthrophobacterales | 1 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 69, 129, 166, 499, 508, 509, 510 |

| Bdellovibrionales | 2 | 1 | 130, 684 | ||

| Myxococcales | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 78, 129, 133, 140 |

| Unknown | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 69, 209, 142, 143, 511 |

| Firmicutes | 1 | 6 | 11 | 6 | |

| Peptococcaceae | 3 | 1 | 3 | 150, 151, 155, 291 | |

| Syntrophomonadaceae | 6 | 1 | 288, 289, 290, 300, 301 | ||

| Other Firmicutes | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 82, 167, 305, 306, 290, 480, 559 |

| Verrucomicrobia | 1 | 2 | 1 | 67, 80, 169, 220 | |

| Acidobacteria | 10 | 10 | 11 | 6 | 142, diversec |

| Actinobacteria | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 67, 132, 133, 139, 142, 143, 163, 278 |

| Nitrospira | 1 | 2 | 2 | 152, 285, 291, 356 | |

| Thermomicrobia | 8 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 460, diverse |

| Bacteroidetes | 17 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 89, 93, diverse |

| Chlorobi | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 89, 492, diverse |

| Othersa | 10 | 10 | 6 | 7 | Diverse |

| Total | 70 | 82 | 69 | 53 | |

Others include OP10, OP5, WS3, Deinococcus-Thermus, OD1-OP11-WS6-TM, Gemmatimonadales, Planctomycetes, Spirochaetes, Fibrobacterales, OP8, and unclassified groups.

T-RFs listed are predicted from sequence data (in silico).

“Diverse” indicates that the phylogenetic group contains not only the indicated T-RFs but also several different ones.

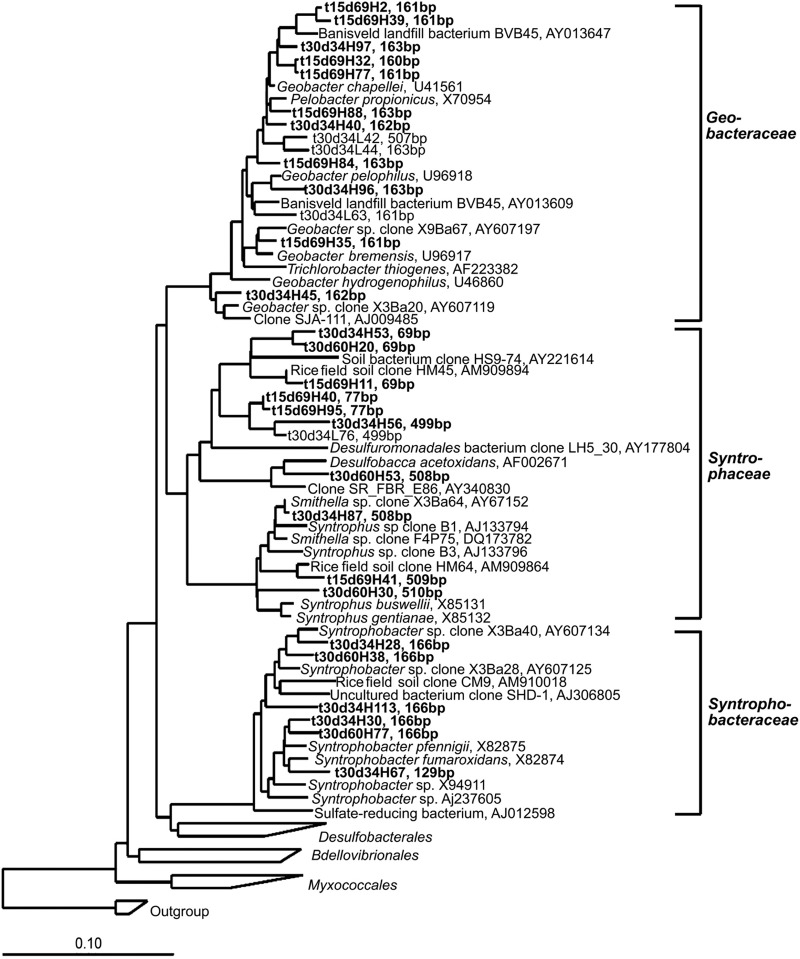

Fig 3.

Phylogenetic relationship of representative sequences affiliated to Deltaproteobacteria. The 16S rRNA gene clone libraries were generated from DNA gradient fractions of anoxic rice soil after incubation with [13C]propionate. The clone sequences from this study are shown in boldface and are named after the incubation temperature (t), sampling time (d), DNA gradient fraction (H for heavy and L for light) and the clone number. In silico T-RF sizes are shown after the clone names. The scale bar represents 10% sequence divergence, and GenBank accession numbers of reference sequences are indicated.

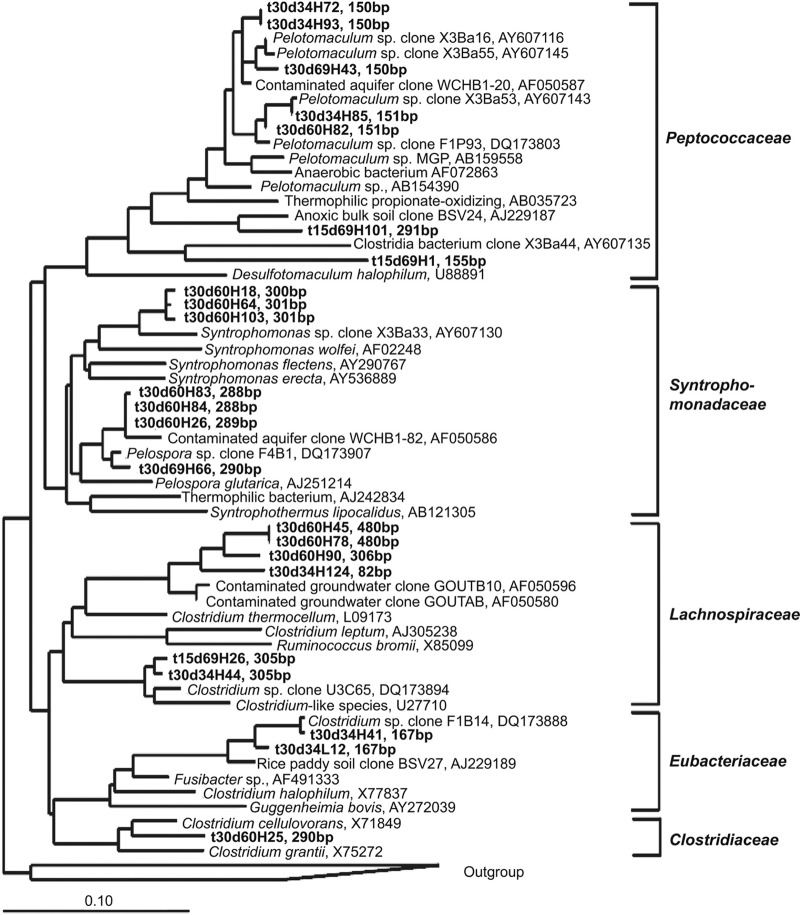

Fig 4.

Phylogenetic relationship of representative sequences affiliated to Firmicutes. Other information is explained in the legend to Fig. 3.

In silico analysis of clone sequences allows the assignments of the experimentally detected T-RFs as follows: 125 and 166 bp to Syntrophobacter spp., 151 bp to Pelotomaculum spp., 510 bp to Smithella spp., 163 bp to Geobacter spp., and 289 bp and 301 bp to Syntrophomonas spp. (Fig. 3 and 4). The dominant T-RFs in the nonlabeled samples were possibly related to Bacteroidetes (89 bp and 93 bp) and Actinobacteria (131 bp). A few T-RFs (142, 433, 442, 460, 480, and 492 bp) substantially increased in heavy gradients, but their assignment appeared complicated, with a particular T-RF being indicative of different bacterial lineages (Table 1). These T-RFs were probably affiliated with members of Acidobacteria and Actinobacteria (142 bp), Rhodocyclaceae (433, 480, and 492 bp), Rhodospirillaceae (442 bp), and Thermomicrobia (460 bp).

Analyses of density-resolved archaea.

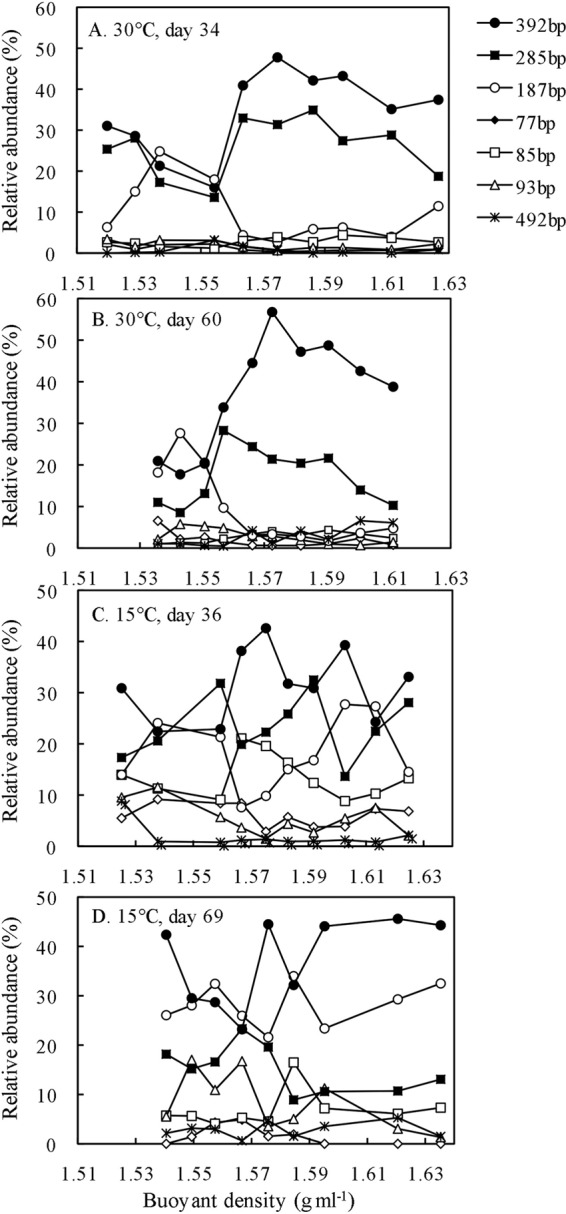

In the T-RFLP analyses of archaeal community, three T-RFs (187, 285, and 392 bp) were most abundant across T-RFLP profiles (see Fig. S6 and S7 in the supplemental material). Incubation time had no significant effect on T-RFLP patterns in incubations at 30°C (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). T-RFs of 285 and 392 bp were enriched in the heavy DNA fractions (BD > 1.564 g ml−1), whereas enrichment of 187 bp decreased after incubation of [13C]propionate (Fig. 5A and B). By comparison, T-RFLP patterns did not vary among BD gradients for the control soils at both dates (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). The relative abundance of a few T-RFs including 77, 85, 93, and 492 bp increased in incubations at 15°C (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). T-RFLP profiles at day 36 showed an inconsistent pattern with the increase of DNA buoyant density (Fig. 5C). T-RFLP profiles at day 69 revealed the predominance of 187 bp and 392 bp in heavy DNA gradients, while 285 bp decreased compared with 30°C (Fig. 5D). The control soils showed a shift from the dominance of 392 bp at day 36 to 187 bp at day 69 (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material).

Fig 5.

T-RFLP fingerprints of the archaeal 16S rRNA genes retrieved from density-resolved DNA from incubations with 13C-labeling treatment at 30°C on day 34 (A), 30°C on day 60 (B), 15°C on day 36 (C), and 15°C on day 69 (D). Shown is the relative abundance of individual T-RFs as a function of DNA buoyant density (g ml−1) in CsTFA. The complete set of T-RFLP profiles along DNA density gradients for control and 13C-labeling treatment can be found in Fig. S6 and S7 in the supplemental material.

Sequence analysis of 200 archaeal clones indicated that the archaeal community in the soil consisted of Methanosaetaceae, Methanomicrobiales, Methanocellales, uncultured Euryarchaeota, and Crenarchaeota (Table 2). Based on in silico analysis of archaeal sequences, the characteristic T-RFs can be assigned to Methanosaetaceae (285 bp), Methanobacteriales (93 bp), Methanomicrobiales and Methanocellales (392 bp), and Methanosarcinaceae and the uncultured Crenarchaeota lineages (187 bp). The T-RFs of 77 bp and 494 bp probably represented the uncultured Euryarchaeota lineages.

Table 2.

Phylogenetic affiliations and numbers of archaeal 16S rRNA gene clones retrieved in libraries generated from density-resolved nucleic acids collected at different time from the incubations at 15 and 30°C

| Phylogenetic group | Relative abundance (%) of clones |

T-RF length(s) of clones (bp)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30°C, day 34, light gradient | 30°C, day 34, heavy gradient | 30°C, day 60, heavy gradient | 15°C, day 36, heavy gradient | 15°C, day 69, heavy gradient | ||

| Methanosaeta | 13 | 19 | 12 | 7 | 1 | 285 |

| Methanosarcina | 1 | 2 | 187 | |||

| Methanomicrobiaceae | 2 | 21 | 16 | 4 | 8 | 392 |

| Methanobacteriaceae | 1 | 1 | 93 | |||

| Methanocellales | 2 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 392 |

| Euryarchaeota | 5 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 77, 494, and diverseb |

| Crenarchaeota | 20 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 6 | 74, 187 |

| Total | 43 | 52 | 42 | 33 | 30 | |

T-RFs listed are predicted from sequence data (in silico).

“Diverse” indicates that the phylogenetic group contains not only the indicated T-RFs but also several different ones.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we determined syntrophic oxidation of propionate in paddy field soil at 15°C and 30°C. Propionate (either 13C labeled or nonlabeled) was applied to a concentration of 10 mM in anaerobic soil, and the assimilation of 13C by microbes was traced by DNA-SIP. Rice field soil receives various organic materials in the forms of organic manure and plant residues. A concentration of propionate up to 10 mM can be found locally during anaerobic decomposition of organic material (9). However, during most of the period of quasi-steady state of methanogenesis, particularly without application of organic material, propionate concentration is typically less than 1 mM in rice field soil (44). Thus, we would indicate that our experiment represents the soil condition when organic material is applied. Caution might be taken when the results are extended to the steady-state condition with low propionate concentration.

The methane production rate was 1 order of magnitude lower at 15°C than 30°C, consistent with several previous studies (1, 6, 29). 13C-labeled CH4 was detected immediately after addition of [13C]propionate into soil slurries, indicating that propionate oxidation occurred actively and was closely coupled with CH4 production. Despite a low rate of total CH4 production at 15°C, 13C labeling of CH4 reached a level similar to the one achieved at 30°C, suggesting that the syntrophic oxidation of propionate was active as well at 15°C.

DNA-SIP revealed that Syntrophobacter spp. (indicated by T-RFs 125 bp and 166 bp), Pelotomaculum spp. (151 bp), Smithella spp. (510 bp), and Geobacter spp. (163 bp) incorporated the propionate-derived 13C into their nucleic acids during the incubation at 30°C. All these organisms except Geobacter spp. are known to syntrophically oxidize propionate under methanogenic conditions (17, 26). Using a similar SIP approach, Lueders and colleagues (23) have demonstrated the activity of these organisms. In their study, however, sufficient labeling was obtained only in one RNA gradient fraction after 7 weeks of [13C]propionate incubation. In the present study, we detected significant 13C labeling of DNA repeatedly over about 2 months of incubation, thus providing strong confirmation of the activity of these syntrophs in the rice field soil.

Smithella spp. were known to utilize a dismutation pathway in which propionate is first dismutated to acetate and butyrate and then degraded via β-oxidation (4, 20). The labeling of Smithella spp. (510 bp) relatively increased in the later stage (day 60) at 30°C (Fig. 2B). Correspondingly, Syntrophomonas spp. (289 bp and 301 bp) were enriched in the heavy gradient fractions at day 60. Syntrophomonas spp. have been identified as active syntrophic butyrate oxidizers in our previous study of the same soil (19). Possibly, a multiple trophic interaction between propionate- and butyrate-oxidizing syntrophs occurred during the degradation of propionate in soil.

Temperature is an important regulator influencing biochemical kinetics of microorganisms. For propionate syntrophs, temperature influences not only the biochemical activity but also the thermodynamics and the physical association between syntrophic partners. To overcome the thermodynamic barrier, syntrophic partners must stay in a close association for efficient interspecies electron transfer (14). The decrease of temperature from 30°C to 15°C corresponded to a free-energy reduction of 6.7 kJ mol−1 propionate and a decreased rate of H2-scavenging reaction (methanogenesis), both making the thermodynamic situation more severe. The literature shows that pure cultures of propionate syntrophs rarely show a minimum growth temperature of less than 20°C (10, 12, 13, 20, 39). In the present study, however, we discovered that the syntrophic propionate oxidation coupled to CH4 production occurred actively at 15°C in rice field soil, albeit at a lower rate than at 30°C. Previous studies on the degradation of organic residues also showed no accumulation of propionate at low temperature (32), indicating anaerobic oxidation. Thus, propionate syntrophs may have developed mechanisms to cope with low temperature in environment. However, mainly Syntrophobacter spp. (166 bp) and Smithella spp. (510 bp) remained active, while Pelotomaculum decreased at 15°C. These results indicate that propionate syntrophs may have different mechanisms of adaptation to temperature change. These mechanisms remain currently unclear.

In addition to known syntrophs, the nucleic acids of Geobacter spp. (163 bp) were significantly enriched with propionate-derived 13C, especially at 15°C. Geobacter spp. are widespread in anoxic sediments and soils and typically carry out the dissimilatory reduction of iron(III) coupled with oxidation of acetate and many other electron donors (25). Several possible mechanisms may explain the 13C labeling of Geobacter spp. First, the labeling of Geobacter spp. was due to their utilization of [13C]acetate produced from [13C]propionate. The low reduction rate of Fe(III) during the preincubation, especially at 15°C, probably made Fe(III) available for Geobacter spp. during the incubation with [13C]propionate. It was also possible that Geobacter spp. oxidized acetate by utilizing crystalline Fe(III) in the absence of soluble iron species under methanogenic conditions (11). Second, it was likely that Geobacter could have utilized propionate directly for the dissimilatory reduction of iron. A few pure cultures have showed growth with propionate as carbon and energy source (2). Third, the mechanism might involve extracellular electron transfer. It has been reported that direct electron transfer possibly occurs in the syntrophic interaction involving Geobacter spp. (16, 38). These novel findings imply that Geobacter spp. could play a vital role in the degradation of intermediate fatty acids in rice field soil, even if methanogens are simultaneously active.

Several T-RFs also increased substantially in the heavy DNA fractions but with complicated affiliations. The probable organisms included members of Rhodocyclaceae, Rhodospirillaceae, Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Thermomicrobia (Table 1). These organisms have never been shown to syntrophically oxidize fatty acids. Rhodocyclaceae have been demonstrated to reduce different substances like Fe(III), U(VI), nitrate, and perchlorate with acetate as the substrate under anaerobic conditions (41). It is possible that these organisms utilized propionate-derived C to reduce Fe(III) in the same manner as Geobacter spp. in rice field soil. The 13C labeling of other anaerobic organisms was probably due to the cross-feeding or unknown mechanisms.

Among archaea, Methanosaetaceae, Methanomicrobiales, and Methanocellales incorporated 13C into their DNA during the incubation at 30°C. Methanomicrobiales and Methanocellales remained active, whereas Methanosaetaceae decreased at 15°C, especially in the later stage. Methanosarcinaceae seemed to increase. These results differ from our previous study on the syntrophic oxidation of butyrate, in which Methanosarcinaceae served as a major methanogenic partner (19). It is currently unclear why different methanogens were selected during the oxidation of different fatty acids. The concentration of acetate can be a crucial factor for the activity of Methanosarcinaceae relative to Methanosaetaceae (15, 29). Oxidation of propionate probably produced a lower steady-state concentration of acetate than butyrate (34), hence favoring Methanosaetaceae over Methanosarcinaceae. In addition, the species-specific partnership may occur among syntrophic organisms. Recently, it was revealed that signaling-like communication occurs in the syntrophic interaction between Pelotomaculum thermopropionicum and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus (35). Such an interaction could promote the formation of partner-specific associations for the oxidation of different fatty acids in soil.

In conclusion, our study revealed that the syntrophic bacteria Syntrophobacter spp., Pelotomaculum spp., and Smithella spp. were involved in syntrophic propionate oxidation at 30°C, while both activity and syntrophic diversity possibly decreased at 15°C. In addition, Geobacter spp. and some other anaerobic organisms actively assimilated the propionate-derived 13C, especially at low temperature, probably due to complex mechanisms involving direct or indirect electron transfers derived from propionate. Methanomicrobiales, Methanocellales, and Methanosaetaceae acted as methanogen partners at 30°C. The activity of Methanosaetaceae, however, decreased at 15°C. Collectively, our study demonstrated a strong regulation of temperature on syntrophic interactions in rice field soil.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank three anonymous reviewers for constructive reviews of the manuscript.

This study was partly supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (grant no. 2011CB100505) and the Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 40830534 and 40625003).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 11 May 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chin KJ, Lukow T, Conrad R. 1999. Effect of temperature on structure and function of the methanogenic archaeal community in an anoxic rice field soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65: 2341– 2349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coates JD, Bhupathiraju VK, Achenbach LA, McLnerney MJ, Lovley DR. 2001. Geobacter hydrogenophilus, Geobacter chapellei and Geobacter grbiciae, three new, strictly anaerobic, dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducers. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51: 581– 588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conrad R, Klose M, Noll M. 2009. Functional and structural response of the methanogenic microbial community in rice field soil to temperature change. Environ. Microbiol. 11: 1844– 1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Bok FAM, Stams AJM, Dijkema C, Boone DR. 2001. Pathway of propionate oxidation by a syntrophic culture of Smithella propionica and Methanospirillum hungatei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67: 1800– 1804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drake HL, Horn MA, Wüst PK. 2009. Intermediary ecosystem metabolism as a main driver of methanogenesis in acidic wetland soil. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1: 307– 318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fey A, Chin KJ, Conrad R. 2001. Thermophilic methanogens in rice field soil. Environ. Microbiol. 3: 295– 303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fey A, Claus P, Conrad R. 2004. Temporal change of 13C-isotope signatures and methanogenic pathways in rice field soil incubated anoxically at different temperatures. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 68: 293– 306 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fumoto T, Kobayashi K, Li C, Yagi K, Hasegawa T. 2008. Revising a process-based biogeochemistry model (DNDC) to simulate methane emission from rice paddy fields under various residue management and fertilizer regimes. Glob. Change Biol. 14: 382– 402 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glissmann K, Conrad R. 2000. Fermentation pattern of methanogenic degradation of rice straw in anoxic paddy soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 31: 117– 126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harmsen HJM, et al. 1998. Syntrophobacter fumaroxidans sp. nov., a syntrophic propionate-degrading sulfate-reducing bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48: 1383– 1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hori T, Noll M, Igarashi Y, Friedrich MW, Conrad R. 2007. Identification of acetate-assimilating microorganisms under methanogenic conditions in anoxic rice field soil by comparative stable isotope probing of RNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73: 101– 109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imachi H, et al. 2002. Pelotomaculum thermopropionicum gen. nov., sp nov., an anaerobic, thermophilic, syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52: 1729– 1735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imachi H, et al. 2007. Pelotomaculum propionicicum sp. nov., an anaerobic, mesophilic, obligately syntrophic propionate-oxidizing bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57: 1487– 1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishii S, Kosaka T, Hori K, Hotta Y, Watanabe K. 2005. Coaggregation facilitates interspecies hydrogen transfer between Pelotomaculum thermopropionicum and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71: 7838– 7845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jetten MSM, Stams AJM, Zehnder AJB. 1992. Methanogenesis from acetate: a comparison of the acetate metabolism in Methanothrix soehngenii and Methanosarcina spp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 88: 181– 197 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kato S, Hashimoto K, Watanabe K. 2011. Methanogenesis facilitated by electric syntrophy via (semi)conductive iron-oxide minerals. Environ. Microbiol. [Epub ahead of print.] doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kosaka T, et al. 2008. The genome of Pelotomaculum thermopropionicum reveals niche-associated evolution in anaerobic microbiota. Genome Res. 18: 442– 448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu F, Conrad R. 2010. Thermoanaerobacteriaceae oxidize acetate in methanogenic rice field soil at 50 °C. Environ. Microbiol. 12: 2341– 2354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu P, Qiu Q, Lu Y. 2011. Syntrophomonadaceae-affiliated species as active butyrate-utilizing syntrophs in paddy field soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77: 3884– 3887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Balkwill DL, Aldrich HC, Drake GR, Boone DR. 1999. Characterization of the anaerobic propionate-degrading syntrophs Smithella propionica gen. nov., sp. nov. and Syntrophobacter wolinii. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49: 545– 556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu Y, Lueders T, Friedrich MW, Conrad R. 2005. Detecting active methanogenic populations on rice roots using stable isotope probing. Environ. Microbiol. 7: 326– 336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludwig W, et al. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32: 1363– 1371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lueders T, Pommerenke B, Friedrich MW. 2004. Stable-isotope probing of microorganisms thriving at thermodynamic limits: syntrophic propionate oxidation in flooded soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70: 5778– 5786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lueders T, Manefield M, Friedrich MW. 2004. Enhanced sensitivity of DNA- and rRNA-based stable isotope probing by fractionation and quantitative analysis of isopycnic centrifugation gradients. Environ. Microbiol. 6: 73– 78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahadevan R, Palsson BO, Lovley DR. 2011. In situ to in silico and back: elucidating the physiology and ecology of Geobacter spp. using genome-scale modelling. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9: 39– 50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller N, Worm P, Schink B, Stams AJM, Plugge CM. 2010. Syntrophic butyrate and propionate oxidation processes: from genomes to reaction mechanisms. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2: 489– 499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noll M, Klose M, Conrad R. 2010. Effect of temperature change on the composition of the bacterial and archaeal community potentially involved in the turnover of acetate and propionate in methanogenic rice field soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 73: 215– 225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page AL, Miller RH, Keeney DR. 1982. Methods of soil analysis. Part 2. Chemical and microbiological properties, 2nd ed American Society of Agronomy, Madison, WI [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng J, Lü Z, Rui J, Lu Y. 2008. Dynamics of the methanogenic archaeal community during plant residue decomposition in an anoxic rice field soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74: 2894– 2901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiu Q, Conrad R, Lu Y. 2009. Cross-feeding of methane carbon among bacteria on rice roots revealed by DNA-stable isotope probing. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1: 355– 361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiu Q, Noll M, Abraham WR, Lu Y, Conrad R. 2008. Applying stable isotope probing of phospholipid fatty acids and rRNA in a Chinese rice field to study activity and composition of the methanotrophic bacterial communities in situ. ISME J. 2: 602– 614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rui J, Peng J, Lu Y. 2009. Succession of bacterial populations during plant residue decomposition in rice field soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75: 4879– 4886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rui J, Qiu Q, Lu Y. 2011. Syntrophic acetate oxidation under thermophilic methanogenic condition in Chinese paddy field soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 77: 264– 273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schink B. 1997. Energetics of syntrophic cooperation in methanogenic degradation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61: 262– 280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimoyama T, Kato S, Ishii S, Watanabe K. 2009. Flagellum mediates symbiosis. Science 323: 1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stams AJM. 1994. Metabolic interactions between anaerobic bacteria in methanogenic environments. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 66: 271– 294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stams AJM, Plugge CM. 2009. Electron transfer in syntrophic communities of anaerobic bacteria and archaea. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7: 568– 577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Summers ZM, et al. 2010. Direct exchange of electrons within aggregates of an evolved syntrophic coculture of anaerobic bacteria. Science 330: 1413– 1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallrabenstein C, Hauschild E, Schink B. 1995. Syntrophobacter pfennigii sp. nov., new syntrophically propionate-oxidizing anaerobe growing in pure culture with propionate and sulfate. Arch. Microbiol. 164: 346– 352 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watanabe A, Yoshida M, Kimura M. 1998. Contribution of rice straw carbon to CH4 emission from rice paddies using 13C-enriched rice straw. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 103: 8237– 8242 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weelink SAB, et al. 2009. A strictly anaerobic betaproteobacterium Georgfuchsia toluolica gen. nov., sp. nov. degrades aromatic compounds with Fe(III), Mn(IV) or nitrate as an electron acceptor. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 70: 575– 585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao H, Conrad R. 2001. Thermodynamics of propionate degradation in anoxic paddy soil from different rice-growing regions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 33: 359– 364 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan Q, Lu Y. 2009. Response of methanogenic archaeal community to nitrate addition in rice field soil. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1: 362– 369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan Y, Conrad R, Lu Y. 2009. Responses of methanogenic archaeal community to oxygen exposure in rice field soil. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1: 347– 354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng F, et al. 2011. Effects of elevated ozone concentration on methane emission from a rice paddy in Yangtze River Delta, China. Glob. Change Biol. 17: 898– 910 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zinder SH. 1993. Physiological ecology of methanogens, p 128– 206 In Ferry JG. (ed), Methanogenesis: ecology, physiology, biochemistry and genetics. Chapman and Hall, New York, NY: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.