Abstract

The role of the two-component system (TCS) CBO0366/CBO0365 in the cold shock response and growth of the mesophilic Clostridium botulinum ATCC 3502 at 15°C was demonstrated by induced expression of the TCS genes upon cold shock and impaired growth of the TCS mutants at 15°C.

TEXT

High and low temperatures are used to control the growth and toxigenesis of harmful bacteria in foods. While high temperatures are prone to kill the bacteria, low temperatures often retard bacterial growth without killing them. Bacteria have developed strategies to sense and adapt to low temperatures. While the cellular mechanisms explaining cold shock tolerance and growth of the model organisms Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis at the lower end of their growth temperature ranges have been widely explored (1–6, 8–11, 16, 17, 26, 31, 32, 38), there are scarce reports on such mechanisms for the notorious food pathogen Clostridium botulinum (36).

Two-component signal transduction systems are central to bacterial sensing and adaptation to environmental changes (25, 27, 30). The two-component system (TCS) histidine kinase senses environmental stimuli with a sensor domain in its N terminus and sends the signal, through autophosphorylation of a histidine residue in its C-terminal transmitter domain, to the TCS response regulator. An aspartate residue in the receiver domain of the response regulator further transmits the phosphoryl group to the C-terminal output domain of the response regulator. Response regulators possess DNA-binding activity, ultimately resulting in a specific response in target gene expression. TCSs in bacteria are differentially specialized to respond to a wide variety of chemical and physical stimuli, including pH, osmolarity, oxidative stress, and temperature. TCSs associated with a response to low temperature in other bacteria include the DesK/DesR in B. subtilis (1–3, 6), CheA/CheY in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (31), CorS/CorR in Pseudomonas syringae (37), and Fp1516/Fp1517 in Flavobacterium psychrophilum (23). In addition, the LisK/LisR, Lmo1173/Lmo1172, and Lmo1061/Lmo1060 systems were linked to the cold shock response but not to long-term growth of Listeria monocytogenes at low temperature (12). The role(s) of TCSs in the cold shock response or adaptation of C. botulinum to low growth temperatures is unknown. Here we show that the TCS CBO0366/CBO0365 (39) is involved with the cold shock response and growth of the model strain C. botulinum ATCC 3502 at 15°C, a temperature close to this strain's minimum growth temperature (24).

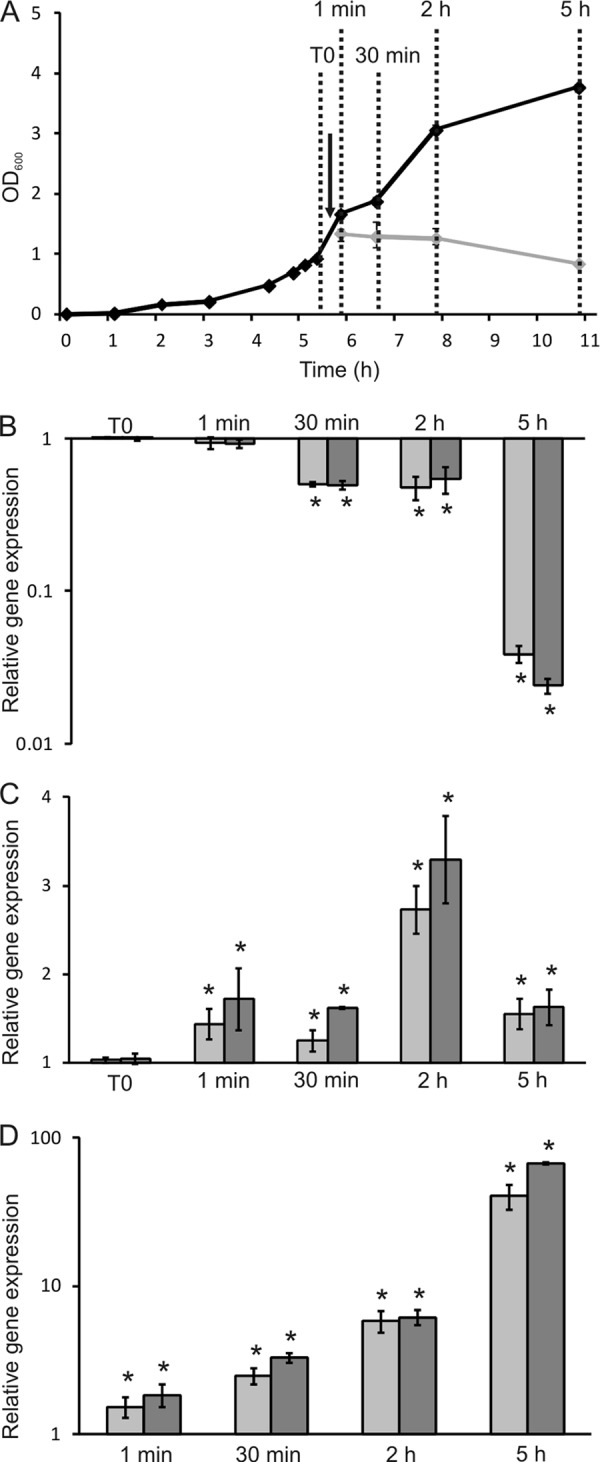

To study the involvement of the TCS CBO0366/CBO0365 in the cold shock response, the relative mRNA levels of cbo0365 and cbo0366 in ATCC 3502 cultures (Table 1) were measured via quantitative reverse transcription-PCR(qRT-PCR) (31, 35) immediately before (T0) and 1 min, 30 min, 2 h, and 5 h after a temperature downshift from 37°C to 15°C with the primers presented in Table 2. A non-cold-shocked culture served as a control (Fig. 1A). In the non-cold-shocked culture at 37°C, the relative mRNA levels of cbo0365 and cbo0366 were significantly downregulated (expression ratios, 0.2 to 0.02; P < 0.05) in late-log and stationary growth phases in relation to the early logarithmic phase (T0) (Fig. 1B). In the cold-shocked culture, however, the relative mRNA levels of cbo0365 and cbo0366 were 1.2- to 3.3-fold induced (P < 0.05) at all time points in relation to T0 (Fig. 1C), suggesting that the gene upregulation was specifically linked to the cold shock response instead of being a stationary-phase event. When calibrated to the non-cold-shocked cultures, up to 40- and 67-fold higher relative cbo0365 and cbo0366 transcript levels, respectively, were measured in the cold-shocked culture (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that a cold shock response and the immediate acclimation of ATCC 3502 to low temperature, as depicted by the growth lag of the cold-shocked culture (Fig. 1A), involve induced expression of the TCS genes cbo0365 and cbo0366. While constitutive expression and delicately balanced control through a phosphorelay system have been reported for most TCSs under normal growth conditions (18, 19, 24, 30), induced TCS expression under cold stress conditions has been reported for B. subtilis and the psychrotrophic Y. pseudotuberculosis (4, 31).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant properties | Sourcea (reference) |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial strains | ||

| C. botulinum ATCC 3502 | Wild type | ATCC (34) |

| C. botulinum ATCC 3502 cbo0365::intron-erm | Insertion deletion in cbo0365 | This study |

| C. botulinum ATCC 3502 cbo0366::intron-erm | Insertion deletion in cbo0366 | This study |

| E. coli TOP10 | Electrocompetence | Invitrogen, Paisley, UK |

| E. coli CA434 | Conjugation donor | UNOTT (33) |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMTL82153 | pBP1 g-positive replicon, catP, ColE1 g-negative replicon, tra, fdx promoter | UNOTT (22) |

| pMTL82153-cbo0366 | pMTL82153 with cbo0366 under transcriptional control of fdx promoter | This study |

| pMTL007 | ClosTron plasmid, catP, intron with ermB RAM | UNOTT (21) |

| pMTL007-cbo0365-48s | Derived from pMTL007 by retargeting to cbo0365 | This study |

| pMTL007-cbo0366-267s | Derived from pMTL007 by retargeting to cbo0366 | This study |

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; UNOTT, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Usec | Binding site in ATCC 3502 genomeb |

|---|---|---|---|

| cbo0365-f | AATGATGCCTAAGATGGATGGT | qRT-PCR | 424216–424237 |

| cbo0365-r | TCTGCACCTGTGGTTAATCCT | qRT-PCR | 424324–424344c |

| cbo0366-f | GGCATACCAAGAGCAGAAACCA | qRT-PCR | 425289–425310 |

| cbo0366-r | ATTTGCAGCAAGCCCTTTGA | qRT-PCR | 425421–425440c |

| 16S rrn-f | TTGTCGTCAGCTCGTGTCGT | qRT-PCR | 10290–10309 |

| 16S rrn-r | CCTGGACATAAGGGGCATGA | qRT-PCR | 10431–10450c |

| cbo0366-f-NdeI | NNNNNNCATATGAAACCTTTCAAATATATA | Construction of overexpression plasmid for cbo0366 | 424779–424796 |

| cbo0366-r-NheI | NNNNNNGCTAGCTTATTCATCCTCTGCCATAA | Construction of overexpression plasmid for cbo0366 | 426235–426254c |

| EBS Universal | CGAAATTAGAAACTTGCGTTCAGTAAAC | Retargeting of pMTL007, control for correct mutation site in cbo0365 and cbo0366 | NA |

| cbo0365-IBS | AAAAAAGCTTATAATTATCCTTAAAAGACATCAGAGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTG | Construction of pMTL007-cbo0365-48s | NA |

| cbo0365-EBS1d | CAGATTGTACAAATGTGGTGATAACAGATAAGTCATCAGAGATAACTTACCTTTCTTTGT | Construction of pMTL007-cbo0365-48s | NA |

| cbo0365-EBS2 | TGAACGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGGTTTCTTTCCGATAGAGGAAAGTGTCT | Construction of pMTL007-cbo0365-48s | NA |

| cbo0365M-f | TTGTTGATGATGAAAAAGAAATCA | Control of pMTL007-cbo0365-48s | 424074–424097 |

| cbo0366-IBS | AAAAAAGCTTATAATTATCCTTAACTATCCAAGAAGTGCGCCCAGATAGGGTG | Construction of pMTL007-cbo0366-267s | NA |

| cbo0366-EBS1d | CAGATTGTACAAATGTGGTGATAACAGATAAGTCCAAGAACTTAACTTACCTTTCTTTGT | Construction of pMTL007-cbo0366-267s | NA |

| cbo0366-EBS2 | TGAACGCAAGTTTCTAATTTCGATTATAGTTCGATAGAGGAAAGTGTCT | Construction of pMTL007-cbo0366-267s | NA |

| cbo0366M-f | TTTTTAATGGCTATTATGACCTTTATT | Control of pMTL007-cbo0366-267s | 424866–424892 |

Underlined portions of sequences indicate the restriction endonuclease site.

Based on EMBL accession number AM412317 (positions are shown according to base pair number). c, complement strand; NA, not applicable.

48s and 267s represent mutations between bases 48 and 49 and between bases 267 and 268, respectively, in the sense orientation.

Fig 1.

Relative expression levels of cbo0365 and cbo0366 in ATCC 3502 induced at 15°C. (A) ATCC 3502 was grown at 37°C, exposed to a temperature downshift (cold shock [gray curve]) at 15°C at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.5, and sampled for qRT-PCR analysis before cold shock (T0) and 1 min, 30 min, 2 h, and 5 h after cold shock. A non-cold-shocked culture (black curve) served as a control. (B) Relative expression levels of cbo0365 (light gray) and cbo0366 (dark gray) in non-cold-shocked cultures calibrated at T0. (C) Relative expression levels of cbo0365 (light gray) and cbo0366 (dark gray) in cold-shocked cultures calibrated at T0. (D) Relative expression levels of cbo0365 (light gray) and cbo0366 (dark gray) in cold-shocked cultures calibrated to non-cold-shocked cultures at the corresponding time points. The normalization reference was 16S rrn. *, P < 0.05 (one-way analysis of variance). Error bars indicate standard deviations of three replicates.

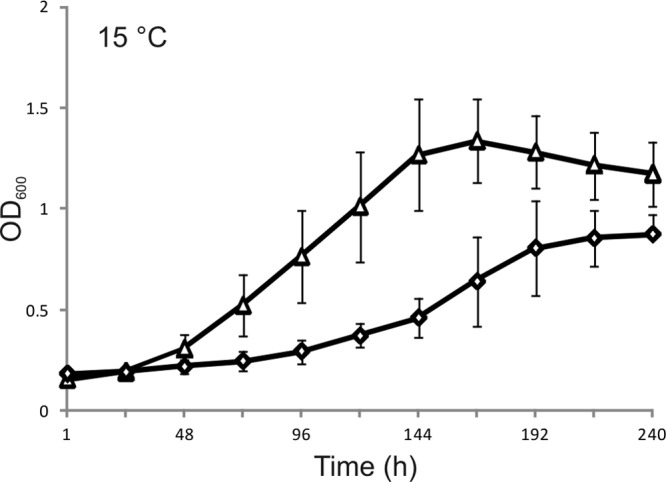

The role of induced cbo0366 expression in the growth of ATCC 3502 at 15°C was further confirmed by introducing pMTL82153-cbo0366, containing the coding sequence of cbo0366 under transcriptional control of the fdx promoter (22), into ATCC 3502 and comparing its ability to grow at 15°C to that of a control strain carrying pMTL82153. The strain harboring pMTL82153-cbo0366 showed enhanced growth over the strain with the empty vector (Fig. 2), suggesting that fdx-mediated overexpression of cbo0366 may have assisted ATCC 3502 to grow at cold temperature.

Fig 2.

Overexpression of cbo0366 improves growth of ATCC 3502 at cold temperatures. ATCC 3502 harboring pMTL82153-cbo0366 (white triangles) or empty pMTL82153 (white diamonds) was grown in tryptose-peptone-glucose-yeast extract (TPGY) medium at 15°C. Error bars indicate standard deviations of three replicates.

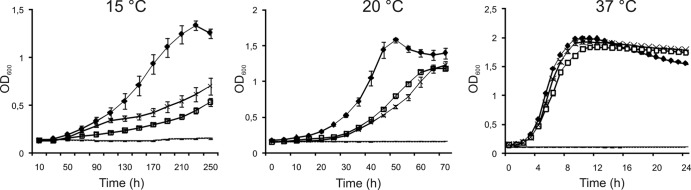

To study the role of intact CBO0366/CBO0365 in adapted growth of ATCC 3502 at low growth temperatures, we constructed cbo0365 or cbo0366 single insertional knockout mutants (the strains and plasmids used are presented in Table 1, and the primers are listed in Table 2) as described previously (13, 20–22, 35, 36) and compared the abilities of these mutants to grow at 37°C, 20°C, and 15°C to the wild-type ATCC 3502 as described previously (24, 35) with 24-hour, 3-day, and 11-day follow-up periods. Both cbo0365 and cbo0366 knockout mutants exhibited markedly impaired growth at 15°C and 20°C in relation to the wild-type culture. At 37°C, all strains showed similar growth curves (Fig. 3). The results suggest that a functional CBO0366/CBO0365 is required for efficient growth of ATCC 3502 at low temperature but not at its optimum temperature. Our previous report on the role of the cold shock protein-encoding genes, showing a cold-sensitive phenotype for a cspB mutant but not for a cspA mutant (36), verified that the mutation procedure itself is not responsible for the cold-sensitive phenotype.

Fig 3.

Growth of cbo0365 and cbo0366 mutants under cold temperatures is impaired compared to ATCC 3502. ATCC 3502 wild type (black diamonds) and cbo0365 (open squares) and cbo0366 (multiplication symbols) mutants were grown in tryptose-peptone-glucose-yeast extract (TPGY) medium at 15°C, 20°C, and 37°C. Results for a negative-control sample (fresh TPGY) are marked with a dashed line. Error bars indicate standard deviations of three replicates.

As with many cold-responsive TCSs reported (7, 12, 23, 31), the stimulus sensed by the CBO0366 kinase remains to be characterized. The cold-responsive DesK of B. subtilis and Hik33 of Synechocystis sp. have been shown to respond to cell membrane fluidity and thickness (1–3, 6, 14, 28) and to control desaturation of the fatty acid chains in cell membrane phospholipids, maintaining elasticity of cell membranes in the cold (2, 28). Temperature-dependent alteration of the cell membrane fatty acid composition has been reported for the psychrotrophic group II C. botulinum (15), but its regulation is unknown.

While the results demonstrate that the cold shock response and acclimation of ATCC 3502 at low temperature involves induced expression of the CBO0366/CBO0365 genes and that the CBO0366/CBO0365 system is required for efficient growth at 15°C, future work is required to unravel the function of this TCS and the role of its downstream events in the cold tolerance of ATCC 3502.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was performed in the Centre of Excellence in Microbial Food Safety Research and funded by the Academy of Finland (118602, 141140, 1115133, and 1120180), Finnish Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, the ABS Graduate School, and the Walter Ehrström Foundation.

Jere Lindén, Sofia Väärikkälä, Hanna Korpunen, Kirsi Ristkari, Esa Penttinen, and Heimo Tasanen are thanked for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 1 June 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Aguilar PS, Cronan JE, Jr, de Mendoza D. 1998. A Bacillus subtilis gene induced by cold shock encodes a membrane phospholipid desaturase. J. Bacteriol. 180:2194–2200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aguilar PS, Hernandez-Arriaga AM, Cybulski LE, Erazo AC, de Mendoza D. 2001. Molecular basis of thermosensing: a two-component signal transduction thermometer in Bacillus subtilis. EMBO J. 20:1681–1691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aguilar PS, Lopez P, de Mendoza D. 1999. Transcriptional control of the low-temperature-inducible des gene, encoding the Δ5 desaturase of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 181:7028–7033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beckering CL, Steil L, Weber MH, Völker U, Marahiel MA. 2002. Genomewide transcriptional analysis of the cold shock response in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 184:6395–6402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beranová J, Jemioła-Rzemińska M, Elhottová D, Strzałka K, Konopásek I. 2008. Metabolic control of the membrane fluidity in Bacillus subtilis during cold adaptation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778:445–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beranová J, Mansilla MC, de Mendoza D, Elhottová D, Konopásek I. 2010. Differences in cold adaptation of Bacillus subtilis under anaerobic and aerobic conditions. J. Bacteriol. 192:4164–4171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Braun Y, et al. 2008. Component and protein domain exchange analysis of a thermoresponsive, two-component regulatory system of Pseudomonas syringae. Microbiology 154:2700–2708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brigulla M, et al. 2003. Chill induction of the SigB-dependent general stress response in Bacillus subtilis and its contribution to low-temperature adaptation. J. Bacteriol. 185:4305–4314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brillard J, Jéhanno, et al. 2010. Identification of Bacillus cereus genes specifically expressed during growth at low temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:2562–2573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Broussolle V, et al. 2010. Insertional mutagenesis reveals genes involved in Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579 growth at low temperature. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 306:177–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Budde I, Steil L, Scharf C, Völker U, Bremer E. 2006. Adaptation of Bacillus subtilis to growth at low temperature: a combined transcriptomic and proteomic appraisal. Microbiology 152:831–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chan YC, et al. 2008. Contributions of two-component regulatory systems, alternative sigma factors, and negative regulators to Listeria monocytogenes cold adaptation and cold growth. J. Food Prot. 71:420–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cooksley CM, et al. 2010. Regulation of neurotoxin production and sporulation by a putative agrBD signaling system in proteolytic Clostridium botulinum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:4448–4460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cybulski LE, Martín M, Mansilla MC, Fernández A, de Mendoza D. 2010. Membrane thickness cue for cold sensing in a bacterium. Curr. Biol. 20:1539–1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evans RI, McClure PJ, Gould GW, Russell NJ. 1998. The effect of growth temperature on the phospholipid and fatty acyl compositions of non-proteolytic Clostridium botulinum. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 40:159–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fang L, Jiang W, Bae W, Inouye M. 1997. Promoter-independent cold-shock induction of cspA and its derepression at 37°C by mRNA stabilization. Mol. Microbiol. 23:355–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graumann P, Schröder K, Schmid R, Marahiel MA. 1996. Cold shock stress-induced proteins in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 178:4611–4619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Halfmann A, et al. 2011. Activity of the two-component regulatory system CiaRH in Streptococcus pneumoniae R6. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20:96–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haydel SE, Clark-Curtiss JE. 2004. Global expression analysis of two-component system regulator genes during Mycobacterium tuberculosis growth in human macrophages. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 236:341–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heap JT, et al. 2010. The ClosTron: mutagenesis in Clostridium refined and streamlined. J. Microbiol. Methods 80:49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heap JT, Pennington OJ, Cartman ST, Carter GP, Minton NP. 2007. The ClosTron: a universal gene knock-out system for the genus Clostridium. J. Microbiol. Methods 70:452–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heap JT, Pennington OJ, Cartman ST, Minton NP. 2009. A modular system for Clostridium shuttle plasmids. J. Microbiol. Methods 78:79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hesami S, Metcalf DS, Lumsden JS, Macinnes JI. 2011. Identification of cold temperature regulated genes in Flavobacterium psychrophilum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:1593–1600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hinderink K, Lindström M, Korkeala H. 2009. Group I Clostridium botulinum strains show significant variation in growth at low and high temperatures. J. Food Prot. 72:375–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hoch JA. 2000. Two-component and phosphorelay signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:165–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hunger K, Beckering CL, Marahiel M. 2004. Genetic evidence for the temperature-sensing ability of the membrane domain of the Bacillus subtilis histidine kinase DesK. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 230:41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Igo MM, Slauch JM, Silhavy TJ. 1990. Signal transduction in bacteria: kinases that control gene expression. New Biol. 2:5–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Inaba M, et al. 2003. Gene-engineered rigidification of membrane lipids enhances the cold inducibility of gene expression in Synechocystis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:12191–12198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lindström M, Kiviniemi K, Korkeala H. 2006. Hazard and control of group II (non-proteolytic) Clostridium botulinum in modern food processing. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 108:92–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mitrophanov AY, Groisman EA. 2008. Signal integration in bacterial two-component regulatory systems. Genes Dev. 22:2601–2611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Palonen E, Lindström M, Karttunen R, Somervuo P, Korkeala H. 2011. Expression of signal transduction system encoding genes of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis IP32953 at 28°C and 3°C. PLoS One 6:e25063 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Palonen E, Lindström M, Korkeala H. 2010. Adaptation of enteropathogenic Yersinia to low growth temperature. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 36:54–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Purdy D, et al. 2002. Conjugative transfer of clostridial shuttle vectors from Escherichia coli to Clostridium difficile through circumvention of the restriction barrier. Mol. Microbiol. 46:439–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sebaihia M, et al. 2007. Genome sequence of a proteolytic (group I) Clostridium botulinum strain Hall A and comparative analysis of the clostridial genomes. Genome Res. 17:1082–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Selby K, et al. 2011. Important role of class I heat shock genes hrcA and dnaK in the heat shock response and the response to pH and NaCl stress of group I Clostridium botulinum strain ATCC 3502. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:2823–2830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Söderholm H, et al. 2011. cspB encodes a major cold shock protein in Clostridium botulinum ATCC 3502. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 146:23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ullrich M, Peñaloza-Vázquez A, Bailey AM, Bender CL. 1995. A modified two-component regulatory system is involved in temperature-dependent biosynthesis of the Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxin coronatine. J. Bacteriol. 177:6160–6169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wiegeshoff F, Beckering CL, Debarbouille M, Marahiel MA. 2006. Sigma L is important for cold shock adaptation of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 188:3130–3133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wörner K, Szurmant H, Chiang C, Hoch JA. 2006. Phosphorylation and functional analysis of the sporulation initiation factor Spo0A from Clostridium botulinum. Mol. Microbiol. 59:1000–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]