Abstract

The development of therapeutics against biothreats requires that we understand the pathogenesis of the disease in relevant animal models. The rabbit model of inhalational anthrax is an important tool in the assessment of potential therapeutics against Bacillus anthracis. We investigated the roles of B. anthracis capsule and toxins in the pathogenesis of inhalational anthrax in rabbits by comparing infection with the Ames strain versus isogenic mutants with deletions of the genes for the capsule operon (capBCADE), lethal factor (lef), edema factor (cya), or protective antigen (pagA). The absence of capsule or protective antigen (PA) resulted in complete avirulence, while the presence of either edema toxin or lethal toxin plus capsule resulted in lethality. The absence of toxin did not influence the ability of B. anthracis to traffic to draining lymph nodes, but systemic dissemination required the presence of at least one of the toxins. Histopathology studies demonstrated minimal differences among lethal wild-type and single toxin mutant strains. When rabbits were coinfected with the Ames strain and the PA− mutant strain, the toxin produced by the Ames strain was not able to promote dissemination of the PA− mutant, suggesting that toxigenic action occurs in close proximity to secreting bacteria. Taken together, these findings suggest that a major role for toxins in the pathogenesis of anthrax is to enable the organism to overcome innate host effector mechanisms locally and that much of the damage during the later stages of infection is due to the interactions of the host with the massive bacterial burden.

INTRODUCTION

Bacillus anthracis, the etiological agent of anthrax, is a Gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium. Spores can be found in soil, and anthrax is primarily a disease of herbivores. Human infection may occur upon exposure to spores via the cutaneous, gastrointestinal, or respiratory routes, but naturally acquired infections in humans generally occur due to exposure to contaminated animal products and result in cutaneous anthrax, which can be easily recognized and effectively treated (27). In contrast, weaponized B. anthracis spores are optimal for aerosol delivery, and a high fatality rate is associated with inhalational exposure, as illustrated by the outbreak in Svedlosk, Russia, in 1979 and the 2001 attacks through the U.S. Postal system (2, 27). For this reason, B. anthracis is listed as a category A priority agent, and the events of recent years have emphasized the need to develop better vaccines and new therapeutics against this potential biothreat. Because the natural incidence of anthrax in humans is very low, and human studies are not feasible or ethical, we must rely on animal models for evaluation of potential vaccines and therapeutics. However, in order to make a strong link between the protection afforded by new vaccines or therapeutics tested in animal models and human efficacy, it is essential that we fully understand the pathogenesis of anthrax and the role of potential therapeutic target(s) in the animal models utilized.

Although infection is initiated after exposure to spores of B. anthracis, the spores germinate once they reach a supportive growth environment in the body, and hematogenous spread of the vegetative bacilli results in a rapidly fatal bacteremia and/or toxemia that is difficult to diagnose early and treat effectively. Production of an antiphagocytic, poly-gamma-d-glutamic acid (γDPGA) capsule (40), and two toxins by the vegetative bacilli are considered the major virulence factors primarily responsible for the symptoms and pathogenesis of anthrax (48). These virulence factors are encoded on two different plasmids in B. anthracis, with the capsule genes encoded on pX02, and the toxin genes encoded on pX01 (21, 42). There are three toxin components that combine to yield the two toxins of B. anthracis, such that the combination of protective antigen (PA) with lethal factor (LF) forms lethal toxin (LT), and PA with edema factor (EF) forms edema toxin (ET). PA is the toxin component responsible for transporting EF and LF into the cytosol of host cells. Upon protease cleavage of PA to its active form, it is able to bind ubiquitously expressed receptors on host cells (7, 15, 67) and heptamerize to form a prepore structure to which one to three molecules of LF and/or EF can bind (46, 49, 50). The toxin complex is then internalized into the cell, followed by a pH-induced conformational change in PA that allows the translocation of EF and LF into the cytosol (1, 4, 45, 79). LF is a zinc metalloprotease that can cleave several mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MAPKK) family members and thus can interfere with numerous signaling pathways (3, 10, 13, 56, 73). EF is a calmodulin-dependent adenylate cyclase which can elevate intracellular levels of cyclic AMP and induce edema (34, 64).

The development of therapeutics and vaccines against anthrax have targeted both the capsule and toxins of B. anthracis. Although the γDPGA capsule is relatively nonimmunogenic (55, 75), recent immunization strategies have been successful in inducing anti-γDPGA antibody responses (30, 61, 66, 74), and passive immunization with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) specific for the capsule of B. anthracis protected mice against a lethal pulmonary spore challenge with the fully virulent Ames strain of B. anthracis (9, 33). However, the predominant strategy for designing vaccines against inhalation anthrax has focused on the toxins and utilizing PA as the primary antigen. The anthrax vaccine currently approved for humans (AVA [anthrax vaccine absorbed]) is derived from a cell-free culture filtrate of an acapsular, attenuated strain of B. anthracis, and immunization of humans results in production of anti-PA antibodies (6, 69, 70). Furthermore, vaccination with AVA has been shown to protect against infection with B. anthracis in animal models (17, 58). The two types of animals deemed most reliable by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for evaluation of anthrax anti-toxin vaccines are nonhuman primates (NHPs) and rabbits; although, due to the limitations of testing in NHPs, the rabbit model is often the first choice for initial assessment of potential therapeutics against anthrax. The pathological changes in both NHPs and rabbits following aerosol exposure to B. anthracis spores resembles that associated with human inhalation anthrax (20, 72, 80). Vaccination with AVA or rPA was protective against an aerosol exposure to spores in both NHP and New Zealand White (NZW) rabbits, and the development of anti-PA antibodies correlated with protection (17, 25, 28, 43, 44, 58, 76). However, because PA is required for both toxins to function, it is unclear whether the protective effect of anti-PA antibody is primarily due to the neutralization of LT and/or ET. Studies examining the effects of pure LT and/or ET directly on cells in vitro, or injection of pure toxin in animals have revealed several potential mechanisms by which LF and EF may exert their toxic effects, including immunomodulatory effects on cells of the immune system, induction of apoptosis, and direct tissue damage (11, 14, 18, 23, 31, 47, 53, 54, 59, 62, 71). Nevertheless, the pathophysiological roles and relative importance of the individual toxins produced during an infection with B. anthracis remains uncertain. This knowledge is particularly important with regard to new therapeutic and vaccine strategies being developed that target the individual toxins or a combination of toxin components (26, 35, 60).

In the present study, we utilized the genetically complete, fully virulent Ames strain of B. anthracis and isogenic mutants to compare the relative importance of the capsule and individual toxins in the pathogenesis of pulmonary anthrax in the NZW rabbit model. Our findings indicate that the capsule and both ET and LT contribute to the lethality of anthrax in rabbits, but the presence of a capsule and only one toxin is sufficient to allow the organism to successfully proliferate and spread systemically. However, the presence of a toxin-producing bacteria did not enable a non-toxin-producing mutant to thrive in the host. Instead, the toxin seems to function in a proximal fashion to allow individual bacteria to overcome host defenses and survive. These results have important implications with regard to strategies for the development and evaluation of future potential vaccines against B. anthracis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of B. anthracis spores or vegetative cell cultures.

The Ames strain of B. anthracis was provided by USAMRIID, Frederick, MD. Ames mutant strains; UTA1 (EF−), UTA2 (LF−), or UTA3 (PA−) were prepared by replacing coding sequences of the toxin genes, cya, lef, and pagA, respectively, with an omega-kanamycin resistance cassette into the Ames strain, using CP51-mediated transduction, as previously described (5, 24). The mutations were confirmed using PCR, and the toxin-negative phenotypes were confirmed using Western blot analysis of supernatants from cultures grown under conditions to promote toxin synthesis. The Ames-derived cap-null strain (UTA8 [ΔcapBCADE]) was similarly constructed using an omega-spectinomycin resistance cassette, as previously described (36). Spore stocks were prepared in phage assay broth as previously described (8, 24), and kanamycin (Sigma; 50 μg/ml) or spectinomycin (100 μg/ml) was added to phage assay media for preparation of UTA mutant spore stocks. The extent of sporulation was assessed by phase-contrast microscopy. Final spore preparations were heated at 68°C for 40 min to kill any remaining vegetative cells and then washed and resuspended in Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS; Gibco), titered, divided into aliquots, and frozen at −80°C. All spores preparations were confirmed to be 100% spores after quantitative plating of aliquots before and after being heated to 68°C for 40 min. Inoculums were prepared by thawing a stock vial to room temperature and diluting it in DPBS to the desired concentration. Vegetative cultures were prepared as previously described (8, 24), and the parent and mutant strains were shown to have similar growth rates under these growth conditions. Briefly, a B. anthracis spore stock was used to streak a nutrient broth yeast agar plate supplemented with 0.8% sodium bicarbonate (NBY-NaHCO3) plus kanamycin (50 μg/ml) when appropriate and incubated at 5% CO2, 37°C for 24 h. Next, two to three colonies were inoculated into 15 ml of Luria-Bertani (LB) broth containing 0.5% glycerol (and antibiotics as appropriate) and shaken at 200 rpm overnight, and then an aliquot of the overnight culture was added to NBY-NaHCO3 broth at an initial optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 and shaken at 200 rpm in 10% CO2 in a 37°C incubator to a final OD600 of 1.2 to give a known concentration. The presence of capsule was confirmed by microscopic visualization using India ink staining. An aliquot was then washed three times with DPBS and diluted to a final desired inoculum concentration in DPBS.

Inoculation of rabbits with B. anthracis. (i) Pulmonary inoculation of spores via bronchoscopy.

The use of bronchoscopy was chosen to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of the dose delivered into the lung between animals infected with wild-type (WT) or mutant strains and between experiments, as well as to exclude the confounding effects of spore uptake in the complex turbinate structure of the rabbit nasal cavity. Female NZW rabbits (3.0 to 3.5 kg) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Oxford, MI) or in early studies from Myrtles Rabbitry (Thompsons Station, TN), and the animals were allowed at least 7 days to acclimate prior to use in studies. For challenge with B. anthracis spores, the rabbits were first anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine and then challenged with either WT-Ames or UTA mutant strain spores delivered directly into the lung by using a specialty fiberscope with a 1.2-mm (3.6 Fr) working channel (fiber-optic, flexible ureteroscope; Karl Storz Veterinary Endoscopy). Each inoculum was prepared from an aliquot of frozen spore stock that was thawed and diluted in DPBS. The bronchoscope was filled with the inoculum through an attached syringe, and then the inoculum was slowly ejected (1 ml/rabbit) from the bronchoscope directly above the bifurcation of the lung as visualized on a color video monitor. Initial studies showed that the number of organisms present in the lung at 4 h postchallenge was consistent with the number of organisms in 1 ml of the inoculum, indicating efficient inoculum delivery into the lung (four experiments; n = 3 rabbits/experiment; P > 0.1 [inoculum versus 4-h total lung CFU]). Preliminary studies were also conducted to examine the distribution of Ames spores in the lung after inoculation via bronchoscopy in which animals were euthanized within 4 h of spore instillation, and each lung lobe (i.e., the right cranial, right caudal, right middle, right accessory, left cranial, and left caudal lobes) was separately dissected, homogenized in 2 ml of PBS, and plated for CFU. The results showed that spores inoculated via bronchoscopy were distributed into all lung lobes regardless of size or location (average range, 104 to 4 × 105 CFU/lobe; n = 2). In addition, the right and left halves of the lung were also assessed separately from rabbits at 24 or 48 h postinfection in initial studies (two experiments; n = six rabbits; two/time point) with similar results. Assessment of total lung bacterial burdens was thus utilized in subsequent studies. For each experiment, the inoculum concentration was determined by quantitative serial plating onto sheep blood agar plates (Remel) in duplicate of inoculum samples obtained from the bronchoscope both before and after administration to rabbits. Plates were incubated overnight to determine the average number of CFU, and the results are expressed as the CFU ± the standard deviation (SD). Comparison plating of the inoculum samples from before and after administration through the bronchoscope showed >99% retention of inoculum concentration. In addition, it was confirmed that each inoculum consisted of spores and not vegetative organisms by comparing the average number of CFU before and after an aliquot of the postchallenge inoculum sample was heated at 68°C for 40 min. Appropriate antibiotic resistance of mutant spore inocula was also confirmed by culturing on LB plates containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml) or spectinomycin (100 μg/ml). For coinfection studies using a combination of WT and UTA3 (PA−) strains, inocula were plated on agar plates with or without kanamycin (50 μg/ml) to distinguish the number of PA− (kanamycin-resistant) organisms from WT organisms. After challenge, the rabbits were monitored, and clinical signs scored at least twice daily postinfection. The mean time to death (MTD) of 2.7 days for animals infected with a lethal dose of Ames strain spores by bronchoscope was similar to what has previously been reported for rabbits after aerosol exposure to spores at 100 times the 50% lethal dose (100 LD50) (78, 80). Studies also confirmed that immunization with AVA provided 100% protection in this model against a lethal pulmonary spore challenge in rabbits (68) and up to the highest dose tested of 8 × 108 Ames spores/rabbit equivalent to 8 × 104 LD50.

(ii) Intravenous injection of vegetative bacilli.

Rabbits were sedated with acepromazine (1 mg/kg, given subcutaneously) and placed in a restrainer. The ear was sterilely prepped, and then the inoculum was injected (0.5 ml/rabbit) intravenously (i.v.) into the marginal ear vein using a syringe with a 25-gauge needle. The final CFU/ml of inoculum was determined by serial dilution and plating in duplicate onto sheep blood agar plates (Remel) and/or on LB plates containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml). All work was conducted in an ABSL-3/SA lab at UNMHSC, and all animal protocols were approved by the UNMHSC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Organ bacterial burden determination.

Rabbits were euthanized at various times postinfection with Sleepaway, and lung-associated lymph nodes (LALN) and individual organs were harvested and placed in DPBS for CFU determination. With regard to the liver, the whole liver was first weighed, and then a midsection was dissected, weighed, and placed in 3 ml of DPBS for CFU determination. Organs were immediately homogenized, and homogenates were then serially diluted and plated onto blood agar plates using an Autoplate 4000 (Spiral Biotech). Colony counts were recorded using an automated counter/scanner system (Q-Count; Spiral Biotek). To enumerate the number of heat-resistant spores present in organ homogenates, diluted samples were plated before and after heating at 68°C for 40 min. For coinfection studies using a combination of WT and PA− strains, aliquots of organ homogenates were plated on agar plates both with or without kanamycin (50 μg/ml) to distinguish the number of PA− (kanamycin resistant) organisms from WT organisms.

Vinblastine treatment.

Rabbits were injected i.v. into the marginal ear vein with injectable vinblastine sulfate (APP Pharmaceuticals) at a dose of 0.75 mg/kg (19, 65) 1 day prior to a pulmonary challenge with B. anthracis, UTA3 (PA−) spores. Blood samples were collected into EDTA-coated collection tubes and analyzed using a veterinary Forcyte hematology system (Oxford Science, Inc.), which included a complete blood count, platelet counts, hematocrit, and white blood cell counts and differentials. Initial studies were conducted to determine the optimal time course for heterophil depletion by monitoring daily changes in cell numbers in individual rabbits before and after vinblastine treatment up to 14 days posttreatment. For B. anthracis spore challenge studies, blood was collected from individual animals prior to organ harvest on day 3 postinfection to confirm cell depletion compared to untreated animals.

Histopathology studies.

Whole organs or a portion of organs were collected, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, processed and embedded in paraffin. Lungs were inflated with 10% buffered saline at time of harvest. Sectioned tissues (∼5 μm in thickness) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and slides were analyzed by a veterinary pathologist.

Statistics.

Comparison of the survival curves between different groups were statistically evaluated by Kaplan-Meier and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) analysis (Prism, version 4.0; GraphPad, San Diego, CA). The LD50 was determined by using both probit and logistic regression analysis with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The data for single comparisons were analyzed by using a Student unpaired t test. Comparison of heated and unheated lung bacterial burdens in the same group of animals was analyzed by paired t test. Comparisons of bacterial burdens between strains were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance using the Newman-Keuls multiple-comparison post hoc test or the Dunnet's test for comparisons with the WT strain.

RESULTS

The presence of a capsule in combination with either LT or ET is sufficient to induce lethality following a pulmonary spore challenge in rabbits.

To investigate the role of individual virulence factors in the pathogenesis of anthrax in rabbits, we utilized isogenic mutants on the Ames background in which either the cap operon (capBCADE) or individual toxin genes—lef (LF), cya (EF), or pagA (PA)—had been deleted. The 50% lethal dose (LD50) for the WT Ames strain of B. anthracis delivered directly into the lung was found to be ∼104 spores/rabbit (Table 1), and 100% lethality was consistently observed at 100 LD50 (106 WT spores/rabbit) with the rabbits succumbing to disease by day 3 (MTD, 2.7 days). However, no deaths occurred following a pulmonary exposure to the cap-null, toxin-positive strain (Cap−) at the maximum dose tested of 109 spores/rabbit, which was equivalent to 105 LD50 for the WT strain. Similarly, the toxin-negative mutant (PA−) was completely avirulent at 109 spores/rabbit. The mutants producing only one toxin also showed a decrease in virulence with a >2-log increase in the LD50 for each strain compared to the WT strain. However, the expression of either lethal toxin or edema toxin alone by B. anthracis mutants was found to be sufficient to cause death, with 84 and 100% lethality observed following infection with 109 spores/rabbit for the LF− and EF− mutants, respectively.

Table 1.

LD50 values for Ames and isogenic mutant strains following pulmonary delivery of spores in NZW rabbitsa

| Strain | Genotype | Mean LD50 ± SE (log10)b |

|---|---|---|

| Ames | WT | 3.98 ± 0.19 |

| UTA1 (EF−) | Δcya | 6.37 ± 0.59 |

| UTA2 (LF−) | Δlef | 6.47 ± 0.66 |

| UTA3 (PA−) | ΔpagAR | >9.0 |

| UTA8 (Cap−) | ΔcapBCADE | >9.0 |

Groups of rabbits were challenged with B. anthracis spores of the Ames (WT), UTA1 (EF−), UTA2 (LF−), UTA3 (PA−), or UTA8 (Cap−) strain at doses ranging between 103 and 109 spores/rabbit for the WT, EF−, and LF− strains (n = 4 to 6 rabbits/dose/strain × two to three experiments/dose/strain) and between 106 and 109 spores/rabbit for the PA− and Cap− strains (n = 3 to 6 rabbits/dose/strain × one to two experiments/dose/strain). The rabbits were monitored twice daily for survival and clinical observations over the course of infection.

The LD50 was determined using probit analysis (95% CI). Similar results were obtained using logistic regression analysis.

Toxins are not required for B. anthracis to reach the LALN and proliferate.

Next, to determine whether the observed differences in virulence between the B. anthracis strains reflected a difference in the ability of the organisms to spread systemically, the early kinetics of bacterial dissemination were compared following a pulmonary spore challenge with 106 spores/rabbit of the WT or the mutant strains. Bacterial burdens were assessed in the lungs, draining lung-associated lymph nodes (LALN), and spleens as a measure of systemic dissemination. Systemic dissemination was also assessed in the blood in early studies, but the results indicated that splenic bacterial burdens provided a more sensitive readout of bacteremia. Higher levels of bacteria were consistently detected in the spleen compared to the blood, and no bacteria were detectable in blood samples from 31% of the rabbits with readily detectable splenic burdens. The presence of bacteria in the spleen also consistently correlated with similar levels of bacteria present in the liver and kidneys (data not shown). Thus, assessment of splenic bacterial burdens was utilized as a measure of systemic bacteremia in subsequent studies.

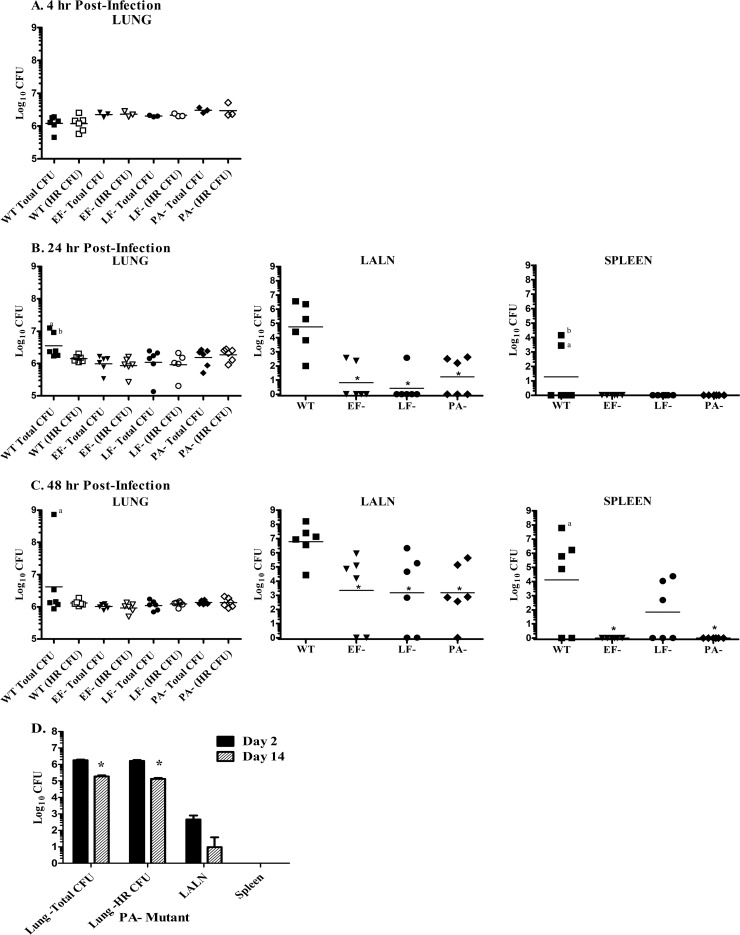

At 4 h after a pulmonary spore challenge with either the WT, EF−, LF−, or PA− strain of B. anthracis, the number of organisms detected in the lungs of infected rabbits was similar to the inoculum levels for every strain of B. anthracis, and all organisms were heat resistant, indicating that no germination had yet occurred (Fig. 1A). Bacteria could also be quantitatively enumerated (between 60 and 2,000 CFU) in LALN at 4 h postchallenge from 2/6, 2/6, 1/6, and 0/6 animals infected with the WT, LF−, EF−, and PA− strains, respectively, and bacteria were detectable in broth cultures prepared from LALN homogenates from infected rabbits for all strains of B. anthracis (WT, 6/6; EF−, 4/6; LF−, 3/6; and PA−, 5/6 rabbits). However, no organisms were detected in the spleens of any animals tested at 4 h postchallenge (data not shown). By 24 h postchallenge, 100% of the rabbits infected with WT spores had bacteria in their LALN (range, 102 to 4 × 106 CFU/LALN), and 2/6 rabbits also had bacteria present in their spleens (Fig. 1B). In contrast, fewer numbers of rabbits infected with the toxin mutants had bacteria present in their LALN and at significantly lower levels (range, 0 to 400 CFU/LALN) than seen in WT-infected rabbits (P < 0.001). Also, no bacteria were detected in the spleens of the rabbits infected with the toxin mutants at 24 h. At 48 h postchallenge, measurable bacterial burdens were found in LALN of all WT-infected rabbits and in ≥70% of the rabbits infected with the B. anthracis toxin mutants, although the bacterial burdens in the toxin mutant-infected rabbits were still significantly (P < 0.05) lower than those observed in the LALN from WT-infected rabbits (Fig. 1C). Dissemination to the spleen was observed in 66% (4/6) of the WT-infected rabbits and in 50% (3/6) of the rabbits infected with the LF− mutant at 48 h postinfection but was not detected in rabbits infected with the EF− or PA− mutants. Bacteria were still undetectable in the spleens of rabbits 2 weeks after challenge with the PA− mutant (Fig. 1D). Instead, a significant decrease in the lung bacterial burden was observed (P < 0.001). Similarly, no bacteria were detected in spleens harvested at 2 weeks postchallenge from animals infected with the toxin-producing, Cap− strain (data not shown). Analysis of the lung bacterial burdens in infected animals at 24 and 48 h postchallenge revealed that the lung heat-resistant spore levels remained similar to inoculum levels at all time points examined. On the other hand, the majority of organisms in the LALN were heat sensitive, with only a low level (range, 0 to 400 CFU/animal/strain) of heat-resistant organisms found in the LALN. Furthermore, all splenic CFU were found to be heat sensitive, indicating that only vegetative organisms were present in the spleen. Overall, an increase in total lung bacterial burden was observed only in WT-infected animals with high levels of bacteria present in their spleens, suggesting that germination did not occur in the airways and that the increased number of organisms detected in the lungs resulted from the hematogenous spread of vegetative organisms in these animals.

Fig 1.

Both ET and LT are required for rapid systemic dissemination. Rabbits (Rb) were inoculated via the pulmonary route with an average of (1.5 ± 0.3) × 106 (WT), (1.2 ± 0.1) × 106 (EF−), (1.6 ± 0.3) × 106 (LF−), or (1.9 ± 0.5) × 106 (PA−) B. anthracis spores. (A) Analysis of lung bacterial burdens at 4 h postchallenge (n = 6 Rb/WT strain or 3 Rb/EF−, LF, or PA− strain). No significant difference was detected between total and heat-resistant (HR) CFU for any strain (P > 0.5), and no bacteria were detectable in spleens at 4 h postchallenge. (B and C) Analysis of lung, LALN, and spleen bacterial burdens at 24 h (B) and 48 h (C) postchallenge (n = 6 Rb/strain/time point). Lung dilution samples were also plated for CFU after heating at 68°C for 40 min to determine the number of HR spores present (one heated lung sample from an LF− strain-infected Rb was lost at 24 h postchallenge). The superscript “a” and “b” denote spleens and lungs, respectively, from the same rabbit. *, Organ bacterial burdens were significantly different from those in WT-infected rabbits (P < 0.05). (D) Bacterial burdens on day 2 (n = 3) and day 14 (n = 5) after pulmonary challenge with PA− mutant spores. Lung bacterial burdens were significantly different between day 2 and day 14 postinfection (*, P < 0.0001).

Either ET and/or LT are required for survival of vegetative bacilli systemically.

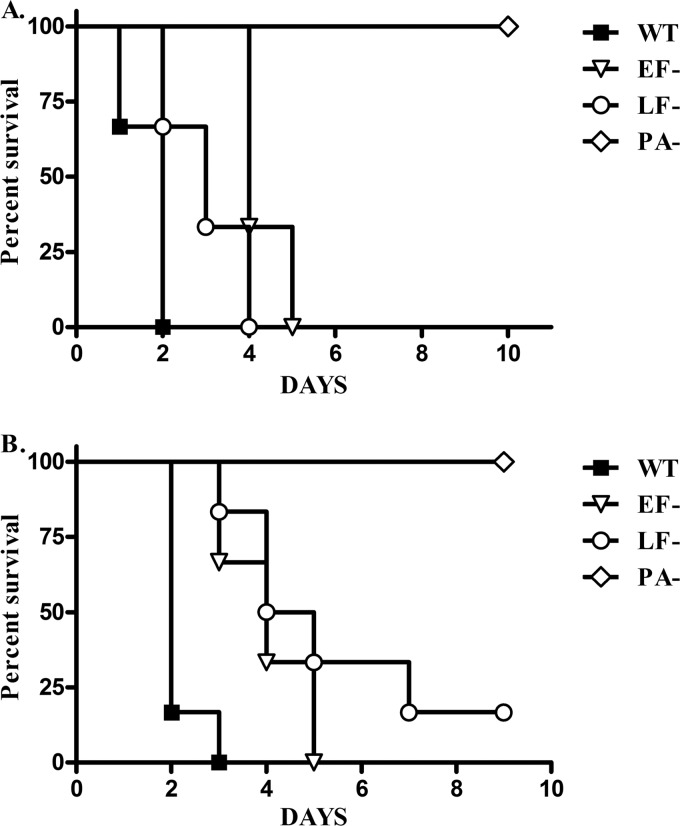

We next sought to determine whether the decreased rate of death for the single toxin mutants simply reflected the delay in dissemination from the LALN compared to WT organisms or whether there was also a difference in the ability of the host to control the bacilli once they became systemic. To test this, rabbits were challenged i.v. with equivalent doses of fully capsulated, vegetative organisms of the WT, EF−, LF−, or PA− strains (Fig. 2). Infection with the single toxin mutants (EF− or LF−) was 80 to 100% lethal, although there was a delay in time to death compared to rabbits infected with the WT strain (average MTD was 1.9 days [WT], 4.2 days [EF−], and 3.8 days [LF−]). In contrast, 100% of the rabbits infected with the PA− strain survived infection, and no bacteria were detectable in the spleens of survivors (data not shown). Further evaluation of lung and splenic bacterial burdens following an i.v. challenge with vegetative bacilli revealed that, although the levels of bacteria present in the lungs and spleens were similar for the different B. anthracis strains at 2 h postchallenge, there were significant differences observed between the strains by 24 h postinfection (Fig. 3). The burdens observed in rabbits infected with the LF− and EF− mutant at 24 h postchallenge remained statistically similar to the levels detected at 2 h postchallenge, whereas a significant increase in bacterial burdens was seen in rabbits infected with the WT strain. In contrast, a significant decrease in bacterial burden was observed in rabbits infected with the toxin-negative (PA−) strain by 24 h postinjection, with no bacteria detectable in four of six rabbits.

Fig 2.

ET and/or LT are required for virulence after an i.v. inoculation of rabbits with vegetative organisms. Survival after i.v. infection with fully capsulated, vegetative bacilli was assessed. (A) Rabbits were infected with 1.9 × 105 WT, 2.5 × 105 EF−, 2.7 × 105 LF−, or 2.9 × 105 PA− vegetative organisms/Rb (n = 3 Rb/strain). (B) Rabbits were infected with 1.3 × 105 WT, 2.2 × 105 EF−, 2.1 × 105 LF−, or 2.0 × 105 PA− organisms/Rb (n = 6 Rb/strain). At the end of the study, no bacteria were detectable in the spleens from rabbits infected with the PA− strain. Significant differences in survival curves were observed for rabbits infected with PA− versus WT, EF−, or LF− strains (P < 0.001) and WT versus EF− or LF− (P < 0.05) but not between rabbits infected with and LF− versus EF− strains (P = 0.23).

Fig 3.

Capsulated, toxin-negative B. anthracis bacilli are rapidly cleared by host. Bacterial burdens in the lungs and spleens at 2 and 24 h after an i.v. infection with capsulated, B. anthracis WT (A), LF− (B), EF− (C), or PA− (D) strains were determined. Each experiment was performed twice (n = 3 Rb/strain/time point/experiment). Average inocula: WT, 1.4 × 105 CFU/Rb; EF−, 3.1 × 105 CFU/Rb; LF−, 3.2 × 105 CFU/Rb; PA−, 2.0 × 105 CFU/Rb. Significant differences in bacterial burdens between 2 and 24 h postinfection are indicated (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001). No difference was observed between time points for rabbits infected with the EF− and LF− strains (P > 0.05). Significant differences were detected for 24-h bacterial burdens in rabbits infected with WT or PA− strains compared to rabbits infected with EF− and LF− strains (P < 0.05).

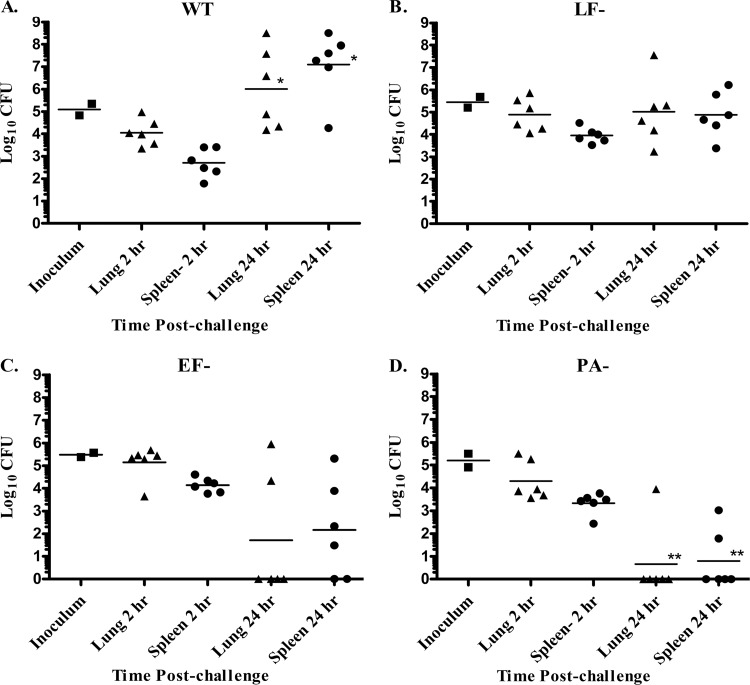

End-organ histopathology is similar after infection with WT or toxin mutant strains of B. anthracis.

All rabbits infected bronchoscopically with a lethal dose of the WT Ames strain exhibited typical histopathologic lesions associated with inhalational anthrax as previously reported in rabbits (78, 80). Briefly, bacilli were detected in vessels of all tissues examined, frequently embedded in fibrin. In the lungs, the alveolar capillaries were distended with fibrin or blood and bacilli, with occasional foci of edema, fibrin exudation, and hemorrhage into alveoli or interstitial connective tissues. The draining lymph nodes exhibited fibrinoheterophilic to necrohemorrhagic inflammation with abundant bacilli in the subcapsular, trabecular, and medullary sinuses, and the adjacent mediastinal connective tissue and fat frequently exhibited edema, hemorrhage, and bacilli. The splenic red pulp exhibited similar fibrinoheterophilic to necrohemorrhagic inflammation with abundant bacilli. Bacilli were also detected in the hepatic sinusoids, along with widespread necrotic cell debris; in the renal glomeruli; and in the meninges, with variable fibrin exudation, edema, and hemorrhage. Lymphocyte necrosis and depletion was evident in the LALN, spleen, thymus, and lymphoid tissue of the sacculus rotundus and cecal appendix. These findings are also similar to what has been described in human anthrax cases (22).

Next, we wanted to compare the effects of having two versus one toxin on the resulting organ histopathology after a lethal infection with the WT, EF−, or LF− strains. Because the lethal pulmonary challenge doses between WT and toxin mutant strains were different, organ histopathology was examined following an i.v. challenge using equivalent doses of vegetative organisms of either the WT or toxin mutant strains. Postmortem examination of organs, including the lungs, heart, brain, liver, kidney, spleen, and lymphoid tissues (LALN, cecal appendix, and sacculus rotundus), following a lethal i.v. challenge with WT organisms again revealed typical histopathologic lesions, as seen following inhalational exposure with a lethal dose of WT organisms. Similar findings were also identified upon examination of organs from animals that died after i.v. inoculation with the single toxin mutants, but no abnormalities were observed in the PA− mutant-infected rabbits sacrificed at day 19 postinfection (Fig. 4). Overall, no discernible differences were observed in the histopathologic pattern that distinguished rabbits infected with the B. anthracis WT strain from those infected with the EF− or LF− mutants.

Fig 4.

Terminal microscopic lesions in the lungs, spleens, livers, and cecal appendices were similar for rabbits challenged i.v. with lethal doses of vegetative Ames strain or either of the single toxin deletion mutants. (A) Lungs. The lungs of rabbits succumbing to WT, EF−, and LF− strains had alveolar septal walls (arrowheads) that were distended by fibrin and protein-rich fluid, which frequently exuded into alveoli (arrows). The lungs of rabbits challenged i.v. with the PA− strain were normal. (B) Spleen. The splenic red pulp (arrows) of the rabbits succumbing to WT, EF−, and LF− strains were necrotic, and fibrin was frequently deposited in red pulp sinuses. The splenic white pulp (arrowheads) of the rabbits succumbing to WT, EF−, and LF− strains exhibited necrosis and depletion of lymphocytes. The spleens of rabbits challenged with the PA− strain were normal. (C) Liver. The hepatic sinusoids of rabbits succumbing to WT, EF−, and LF− strains contained necrotic cell debris and heterophils, and there were small foci of hepatic necrosis (arrows) and loss of hepatocytes. The livers of rabbits challenged with the PA− strain were normal. (D) Cecal appendix. The cecal appendices of rabbits succumbing to WT, EF−, and LF− strains exhibited mucosal edema with necrosis and depletion of lymphoid tissue (arrowheads) and replacement by edema, fibrin, and/or hemorrhage. The cecal appendices of the PA− rabbits were normal. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used.

Depletion of phagocytes decreases host resistance to toxin-negative B. anthracis mutants.

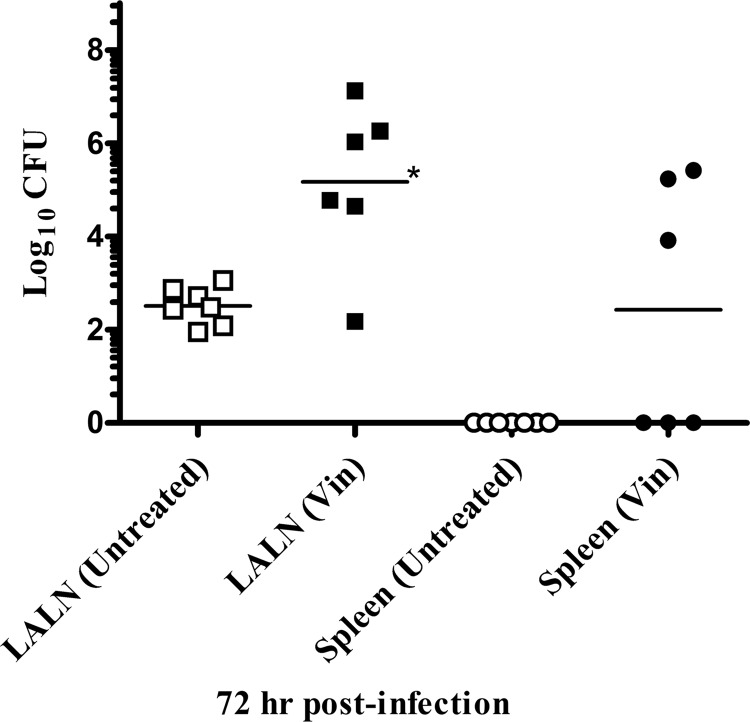

The lack of detectable bacteria in the lung and spleen 24 h after an i.v. challenge with the PA− mutant suggested that the host innate defenses were able to effectively clear this organism. Previous in vitro studies have shown that human neutrophils were able to phagocytize and kill B. anthracis (41). To investigate whether these effector cells played a role in the clearance of the PA− mutants in vivo, the chemotherapy drug, vinblastine, was utilized to deplete rabbit heterophils (the rabbit equivalent of human neutrophils). A dose of vinblastine was chosen that temporarily, but significantly reduced the heterophil levels starting between 48 and 72 h after vinblastine treatment, with an average of 93% reduction in heterophil levels by 96 h after vinblastine treatment compared to untreated rabbits. The monocyte levels also showed some decrease but remained within normal ranges. Rabbits were treated with vinblastine 1 day prior to a pulmonary challenge with the PA− mutant at a dose of 106 spores/rabbit, and then the organ bacterial burdens were assessed over time. The results revealed a significant increase in bacterial levels in the LALN of vinblastine-treated compared to untreated rabbits by 48 h postchallenge (P < 0.05; data not shown). By 72 h postchallenge (96 h after vinblastine treatment), there was a further increase in the LALN bacterial burdens in vinblastine-treated animals, as well as evidence of systemic dissemination with bacteria detected in the spleens of three of six vinblastine-treated rabbits compared to none of the seven untreated animals (Fig. 5). No significant differences were detected in lung spore numbers between treated and untreated rabbits or between heated and unheated lung samples (data not shown).

Fig 5.

Depletion of heterophils decreases host resistance to toxin-negative B. anthracis mutant. The bacterial burdens in the LALN and spleens 72 h after a pulmonary inoculation with PA− mutant spores in untreated rabbits and rabbits that had received a 0.75-mg/kg dose of vinblastine (Vin) i.v. 1 day prior to challenge were determined. An average 93% decrease (range, 92 to 96%) in heterophil levels was observed at the time of harvest in vinblastine-treated rabbits. The experiment was performed twice (average of 2.5 × 106 spores/Rb; n = 3 to 4 Rb/group/time point/experiment). One vinblastine-treated rabbit died prior to 72 h harvest. The LALN CFU levels were significantly different between untreated and vinblastine-treated rabbits (P < 0.005).

The presence of the toxin-producing WT strain of B. anthracis does not increase survival or dissemination of a toxin-deficient strain in the host.

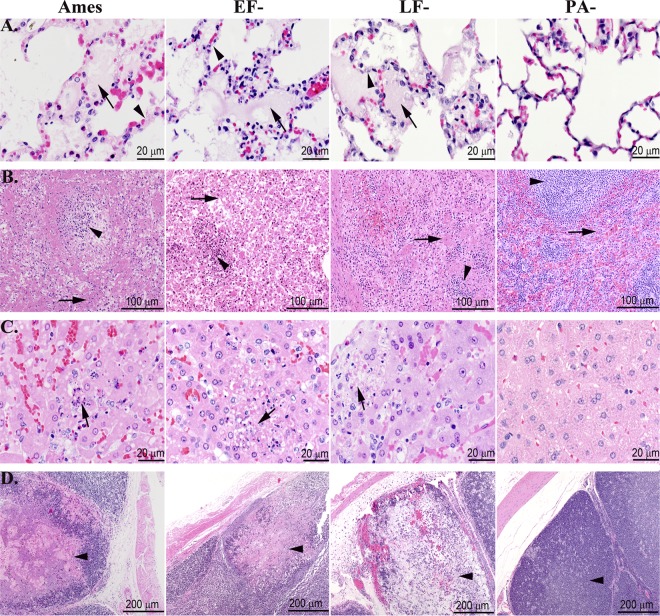

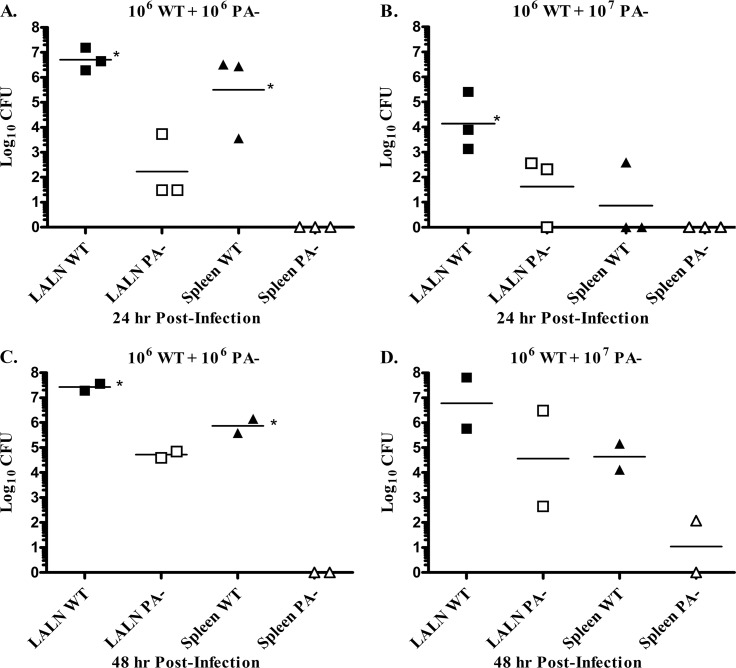

Finally, we investigated whether the production of toxin in vivo would sufficiently disable host defenses to allow the proliferation and systemic spread of a toxin-negative organism. To address this question, rabbits were coinfected via the pulmonary route with WT strain spores and an equal dose of the toxin-negative (PA−) strain spores, and then the numbers of WT organisms versus the kanamycin-resistant PA− mutant were assessed in organs over time. Differences were detected by 24 h postchallenge, with significantly greater numbers of WT organisms present in the LALN compared to PA− organisms (Fig. 6A). In addition, only WT organisms were found in the spleens of all rabbits. A similar pattern was observed when animals were coinfected with 10-fold more PA− organisms than WT organisms, although fewer organisms overall were detected in the LALN at 24 h postinfection when using a 10:1 PA−/WT ratio compared to a 1:1 ratio. Again, only WT organisms were detected in the spleen of one rabbit with evidence of systemic dissemination (Fig. 6B). In a second experiment, bacterial burdens were assessed at 48 h postinfection (Fig. 6C and D). Again, the level of WT organisms was higher than PA− organisms in all infected rabbits, and only WT organisms were present in the spleens, except in one rabbit infected at the 10:1 PA−/WT ratio with concurrently >1,000-fold higher WT splenic burdens (Fig. 6D). In all cases, the number of heat-resistant organisms present in the lungs remained at inoculum levels as previously observed (P > 0.05 [inoculum versus lung heat-resistant CFU]), and an increase in total lung CFU was observed only in rabbits with evidence of splenic bacterial burdens (data not shown).

Fig 6.

The presence of the toxin-producing WT strain of B. anthracis does not increase the survival of a toxin-deficient strain after a pulmonary spore challenge. Bacterial burdens in the LALN and spleen were analyzed at 24 h after a pulmonary challenge with 1.8 × 106 WT plus 1.5 × 106 PA− spores/Rb (A) or 0.9 × 106 WT plus 1.4 × 107 PA− spores/Rb (B) (n = 3 Rb/group) or at 48 h after a pulmonary challenge with 0.9 × 106 WT plus 1.4 × 106 PA− spores/Rb (C) or 0.9 × 106 WT plus 1.5 × 107 PA− spores/Rb (D). (Three Rb/group were infected, but two Rb died prior to harvest.) PA− organisms were distinguished from WT organisms by plating on agar plates with or without kanamycin. Significant differences were observed between WT and PA− bacterial burdens in the LALN or spleen (*, P < 0.05).

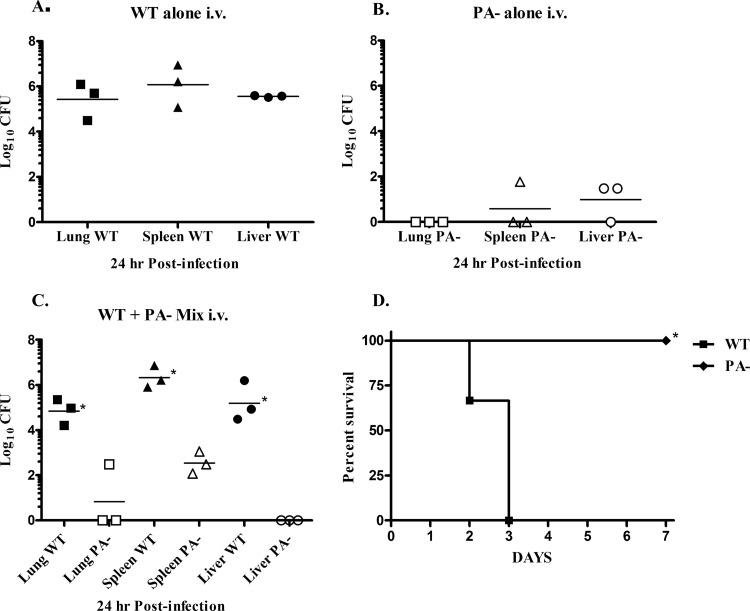

Because the differences observed upon coinfection with the WT and the PA− strain could reflect host control in the LALN rather than the ability of the PA− mutants to thrive once they reached the bloodstream, experiments were conducted in which rabbits were coinfected i.v. with equal numbers of WT and PA− vegetative bacilli, and then the organ bacterial burdens were examined at 24 h postchallenge (Fig. 7A to C). Although the numbers of WT and PA− organisms injected were similar, few toxin-deficient (PA−) organisms remained by 24 h postinfection. In contrast, a significant increase in the number of WT organisms was evident. Furthermore, the organ bacterial burdens observed in rabbits injected with a mixture of both B. anthracis strains was similar to the levels observed in rabbits infected in parallel with only WT or PA− organisms alone. In parallel, an additional group of rabbits infected with either WT or PA− organisms alone were monitored for survival. All rabbits infected with the WT organisms were dead by day 3 of infection, whereas no deaths occurred in animals infected with the PA− organism (Fig. 7D).

Fig 7.

The presence of the toxin-producing WT strain of B. anthracis does not increase survival of a toxin-deficient strain after an i.v. challenge with vegetative bacilli. Analysis of the bacterial burdens in the lungs, spleen, and liver was performed at 24 h after an i.v. challenge with 1.3 × 104 WT CFU/Rb (A), 0.9 × 104 PA− CFU/Rb (B), or 1.3 × 104 WT plus 0.9 × 104 PA− CFU/Rb (C) (n = 3 Rb/group). PA− organisms were distinguished from WT organisms by plating on agar plates with or without kanamycin. Significant differences between WT and PA− organ bacterial burdens were observed (*, P < 0.05). (D) Survival of rabbits after an i.v. challenge with 1.3 × 104 WT compared to 0.9 × 104 PA− CFU/Rb (n = 3 Rb/group) was significantly different (*, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we utilized the genetically complete, fully virulent Ames strain of B. anthracis and isogenic mutants to examine the role of individual virulence factors in the pathogenesis of inhalational anthrax in NZW rabbits. The results of these studies confirmed that both the capsule and the toxins were required for full virulence of B. anthracis in rabbits. As expected, 100% survival was observed in rabbits exposed to a pulmonary spore challenge as high as 109 spores of an acapsular, toxin-producing Ames mutant that was at a dose equivalent to 105 LD50 of the WT strain. Similarly, no deaths were observed after infection with 109 spores of the isogenic mutant lacking PA, which possessed a capsule, but no active toxin. Interestingly, we found that both edema toxin and lethal toxin significantly contributed to the virulence of B. anthracis in rabbits. Removal of one toxin did reduce virulence, resulting in a >2-log increase in the LD50 for either the EF- or LF- negative mutants compared to the WT strain. Importantly, however, the presence of either lethal toxin or edema toxin alone was sufficient to cause lethality in NZW rabbits.

The presence of a capsule and both toxins appeared to be critical for optimal proliferation and systemic dissemination of the organism following germination in the LALN. Although the lung was the initial site of infection, it was not the site of active germination of the spores. The numbers of heat-resistant spores in the lung remained constant over time, whereas heat-sensitive organisms were only detected in animals that also had bacteria present in their spleens, suggesting that the increased lung burden in these animals was due to the hematogenous spread of the organism following systemic dissemination. Similar findings have been described in murine anthrax models (24, 37, 39). Likewise, exposure to B. anthracis spores via the respiratory route in humans does not result in bronchopneumonia, but instead mediastinal lymphadenopathy is prevalent, with prominent hemorrhage and edema in the mediastinal lymph nodes, and evidence of bacteremia and various manifestations of hematogenous spread observed in all fatal cases (2, 22). In contrast to the lung, the majority of organisms in the LALN were heat sensitive, suggesting that the LALN was the primary site of germination. Notably, both the WT and mutant strains were detectable in the rabbit LALN as early as 4 h postinfection, including the toxin-negative (PA−) organisms, which increased in numbers at a rate similar to that observed for the single toxin mutants within the first 48 h of infection. Thus, as shown in mice (38), toxin production was not needed for spores to reach the LALN or germinate in rabbits. Instead, the striking difference observed between the rabbits infected with WT versus the mutant strains was the rapid increase in WT bacterial numbers in the LALN and earlier systemic dissemination. Systemic dissemination was also observed in rabbits infected with the LF− mutants by 48 h postchallenge. This was not unexpected, since an infection dose of 106 spores was approximately the LD50 for both the LF− and EF− mutants, and the lower splenic bacterial burdens observed in rabbits infected with the LF− mutant were consistent with the longer MTD observed in rabbits that died after infection with the single toxin mutants at this dose of spores compared to those infected with the WT strain. No systemic dissemination was detected following a pulmonary challenge with 106 spores of the mutants lacking either a capsule or both toxins (PA−). Furthermore, the results of the i.v. inoculation studies utilizing a defined number of vegetative organisms suggests that, even if some toxin-negative organisms were to gain access to the bloodstream, they would be effectively handled by host defenses, as evidenced by the significant clearance of the PA− mutant by 24 h after i.v. challenge. In contrast, the presence of only one toxin enabled the vegetative bacilli to persist following an i.v. inoculation, although the fully virulent WT strain producing both toxins had the greatest survival advantage with infection resulting in a more rapid bacterial expansion and subsequent death of the host compared to an infection with mutants producing only one toxin. Thus, we hypothesize that the production of both toxins enabled the WT organisms to effectively overcome host defenses, first in the LALN and then systemically, while host defenses were able to slow the proliferation and subsequent spread of organisms producing only one toxin, and effectively prevent systemic spread of organisms that lacked both toxins or a capsule. Such a function of toxin(s) may also help explain the protective effect of passive treatment with anti-PA MAbs in preventing widespread dissemination in infected animals (51, 57). Interestingly, the postmortem organ histopathology following an i.v. challenge with equivalent numbers of either the WT or single toxin mutants was similar regardless of whether the organisms produced both toxins, only LT, or only ET. Our results are consistent with previous reports showing that detection of circulating PA levels correlated with bacteremia (32) but that toxin concentrations did not correlate with time to death (52). Taken together, these findings suggest that a major role for toxins in the pathogenesis of anthrax is to enable the organism to overcome innate host defenses and that the death of the host corresponded with the timing of bacteremia and the degree of organ bacterial burdens rather than due to a systemic toxemia.

Because anthrax is such an acute infection, there is not enough time for the host to develop an adaptive immune response before succumbing to the disease. Instead, host defenses must rely on innate effector cells, particularly phagocytes. Previous studies found that bacteremia in rabbits with inhalational anthrax correlated with an increased number of heterophils in the blood following bacteremia (78), and numerous heterophils were observed histologically in the vicinity of bacilli in both LALN and spleen at early time points during infection (80; data not shown). However, although a heterophilic response could explain clearance of the PA− mutant, it was not enough to provide protection against the fully virulent WT Ames strain in vivo. In vitro studies have shown that both recombinant LT and ET can impair macrophage and neutrophil functions and the production of proinflammatory cytokines (11, 14, 54, 62). Such an immunomodulatory effect of LT and/or ET on heterophils and monocytes may explain the ability of the toxin-producing organisms to overcome innate host defenses in the rabbit. This hypothesis is supported by our finding that the toxin-negative mutant was able to thrive in rabbits depleted of heterophils, with evidence of higher bacterial burdens in the LALN and a significantly increased incidence of systemic dissemination.

The fact that the WT organisms were able to more quickly overwhelm host defenses compared to the single-toxin-producing mutants suggests that there was an additive and/or synergistic effect of having both toxins present. Surprisingly, the toxin(s) appeared to have a limited range of function. Rather than inducing a widespread immunomodulatory effect or toxemia, coinfection with WT and PA− spores did not enable the toxin-negative mutant to persist and expand in the host. Although dissemination of both strains to the LALN occurred by 24 h postinfection in all rabbits coinfected with WT and PA− mutants, only WT organisms were detected systemically, even when a ratio of 10:1 PA− to WT spores were inoculated into the lung. Interestingly, at the 10:1 inoculation ratio, lower numbers of WT organisms were observed, both in the LALN and systemically, than at the 1:1 infection dose. Thus, dissemination of spores to the draining lymph nodes likely represents a stochastic event resulting in fewer WT organisms reaching the LALN at a 10:1 (PA−/WT) ratio. By 48 h after coinfection with WT plus PA− spores, the number of PA− organisms had further expanded in the LALN to levels observed when inoculated alone. However, only the WT organisms were able to effectively spread systemically. This finding was further confirmed in studies in which rabbits were inoculated i.v. with equivalent numbers of WT and PA− vegetative organisms. Even in the presence of equal numbers of toxin-producing vegetative organisms following an i.v. coinfection of WT and PA− strains, the host was able to effectively clear the PA− organisms. Furthermore, the bacterial levels of fully vegetative WT and PA− organisms observed 24 h after i.v. coinfection were similar to the levels observed when rabbits were infected with either the WT or PA− strain alone, suggesting that survival of B. anthracis bacilli was dependent on the ability of each individual organism to produce toxin(s) in order to evade elimination by host effector cells. Our results are consistent with previous reports showing that high plasma levels of toxin are not detected until right before death (32). Instead, the localized effect of toxins may be explained by the recent findings that toxins in blood were associated with capsule (16) and can be packaged as extracellular vesicles which would allow the bacteria to disperse concentrated toxin complexes to act within their immediate vicinity or upon uptake in host phagocytes (63).

The findings in these studies emphasize the need to understand and compare the roles of individual virulence factors in the pathogenesis of anthrax in different mammalian host species in order to facilitate rational strategies for testing potential therapeutics against anthrax and to correctly interpret the results of efficacy studies. For example, evaluation of antitoxin therapeutics would need to utilize animal models in which toxin functions as an important virulence factor. This would include rabbit and NHP models. In immunocompetent mice, the elimination of one or both toxins genes has no impact on the LD50 of the virulent Ames strain (24). Instead, the capsule of B. anthracis is the overwhelmingly dominant virulence factor in mice (12). An alternative mouse model to evaluate antitoxin therapeutics would be to use the complement C5-deficient, A/J or DBA/2, mouse strains. These mouse strains are protected against inhalational anthrax by vaccination with rPA or AVA (77, 81), and lethal toxin was shown to be required for systemic bacterial dissemination and death (38). However, these models require using the acapsular, avirulent Sterne strain of B. anthracis. Thus, depending on the experimental question, evaluation of certain types of therapeutics may be more relevant utilizing a rabbit model with regard to potential treatment strategies for humans. The results of the current studies suggest that, while antitoxin therapeutics against PA would be effective in a rabbit model, therapeutics focused on LT alone would not provide adequate protection in rabbits. On the other hand, NHP would likely serve as a suitable model for LT-targeted therapeutics based on our ongoing studies with these mutants in NHP (unpublished data). Overall, the pathogenesis of anthrax in different species, particularly inhalational anthrax is complex. Anthrax, whether acquired naturally or due to the intentional dissemination of spores, results from infection with the bacterium, B. anthracis, and a critical role of the toxins is to enable B. anthracis organisms to bypass host defenses and disseminate. It is the combination of toxin production in the context of the whole organism, rather than the acquisition of toxins alone that lead to the death of the host. This function of B. anthracis toxins must be considered when designing future vaccines and therapeutics to protect against inhalational anthrax.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support for this study was provided by NIAID grants P01 AI056295 and AI33537.

We thank Lucy Berliba, Quiteria Jacquez, Tara Hendry-Hofer, and Rhonda Garlick for their excellent technical assistance in the performance of these studies and Ronald Schrader for assistance with the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 23 April 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Abrami L, Lindsay M, Parton RG, Leppla SH, van der Goot FG. 2004. Membrane insertion of anthrax protective antigen and cytoplasmic delivery of lethal factor occur at different stages of the endocytic pathway. J. Cell Biol. 166:645–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abramova FA, Grinberg LM, Yampolskaya OV, Walker DH. 1993. Pathology of inhalational anthrax in 42 cases from the Sverdlovsk outbreak of 1979. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:2291–2294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Batty S, Chow EM, Kassam A, Der SD, Mogridge J. 2006. Inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling by Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin causes destabilization of interleukin-8 mRNA. Cell Microbiol. 8:130–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blaustein RO, Koehler TM, Collier RJ, Finkelstein A. 1989. Anthrax toxin: channel-forming activity of protective antigen in planar phospholipid bilayers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:2209–2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bourgogne A, Drysdale M, Hilsenbeck SG, Peterson SN, Koehler TM. 2003. Global effects of virulence gene regulators in a Bacillus anthracis strain with both virulence plasmids. Infect. Immun. 71:2736–2743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brachman PS, et al. 1962. Field evaluation of a human anthrax vaccine. Am. J. Public Health Nations Health 52:632–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bradley KA, Mogridge J, Mourez M, Collier RJ, Young JA. 2001. Identification of the cellular receptor for anthrax toxin. Nature 414:225–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chand HS, et al. 2009. Discriminating virulence mechanisms among Bacillus anthracis strains by using a murine subcutaneous infection model. Infect. Immun. 77:429–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen Z, et al. Pre- and postexposure protection against virulent anthrax infection in mice by humanized monoclonal antibodies to Bacillus anthracis capsule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108:739–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chopra AP, Boone SA, Liang X, Duesbery NS. 2003. Anthrax lethal factor proteolysis and inactivation of MAPK kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 278:9402–9406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crawford MA, Aylott CV, Bourdeau RW, Bokoch GM. 2006. Bacillus anthracis toxins inhibit human neutrophil NADPH oxidase activity. J. Immunol. 176:7557–7565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Drysdale M, et al. 2005. Capsule synthesis by Bacillus anthracis is required for dissemination in murine inhalation anthrax. EMBO J. 24:221–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Duesbery NS, et al. 1998. Proteolytic inactivation of MAP-kinase-kinase by anthrax lethal factor. Science 280:734–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Erwin JL, et al. 2001. Macrophage-derived cell lines do not express proinflammatory cytokines after exposure to Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin. Infect. Immun. 69:1175–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Escuyer V, Collier RJ. 1991. Anthrax protective antigen interacts with a specific receptor on the surface of CHO-K1 cells. Infect. Immun. 59:3381–3386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ezzell JW, et al. 2009. Association of Bacillus anthracis capsule with lethal toxin during experimental infection. Infect. Immun. 77:749–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fellows PF, et al. 2001. Efficacy of a human anthrax vaccine in guinea pigs, rabbits, and rhesus macaques against challenge by Bacillus anthracis isolates of diverse geographical origin. Vaccine 19:3241–3247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Firoved AM, et al. 2005. Bacillus anthracis edema toxin causes extensive tissue lesions and rapid lethality in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 167:1309–1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Frevert CW, et al. 2002. Tissue-specific mechanisms control the retention of IL-8 in lungs and skin. J. Immunol. 168:3550–3556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fritz DL, et al. 1995. Pathology of experimental inhalation anthrax in the rhesus monkey. Lab. Invest. 73:691–702 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Green BD, Battisti L, Koehler TM, Thorne CB, Ivins BE. 1985. Demonstration of a capsule plasmid in Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 49:291–297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guarner J, et al. 2003. Pathology and pathogenesis of bioterrorism-related inhalational anthrax. Am. J. Pathol. 163:701–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hahn AC, Lyons CR, Lipscomb MF. 2008. Effect of Bacillus anthracis virulence factors on human dendritic cell activation. Hum. Immunol. 69:552–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heninger S, et al. 2006. Toxin-deficient mutants of Bacillus anthracis are lethal in a murine model for pulmonary anthrax. Infect. Immun. 74:6067–6074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hepler RW, et al. 2006. A recombinant 63-kDa form of Bacillus anthracis protective antigen produced in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae provides protection in rabbit and primate inhalational challenge models of anthrax infection. Vaccine 24:1501–1514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hermanson G, et al. 2004. A cationic lipid-formulated plasmid DNA vaccine confers sustained antibody-mediated protection against aerosolized anthrax spores. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:13601–13606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Inglesby TV, et al. 2002. Anthrax as a biological weapon, 2002: updated recommendations for management. JAMA 287:2236–2252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ivins BE, et al. 1998. Comparative efficacy of experimental anthrax vaccine candidates against inhalation anthrax in rhesus macaques. Vaccine 16:1141–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reference deleted.

- 30. Joyce J, et al. 2006. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of Bacillus anthracis poly-gamma-d-glutamic acid capsule covalently coupled to a protein carrier using a novel triazine-based conjugation strategy. J. Biol. Chem. 281:4831–4843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kirby JE. 2004. Anthrax lethal toxin induces human endothelial cell apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 72:430–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kobiler D, et al. 2006. Protective antigen as a correlative marker for anthrax in animal models. Infect. Immun. 74:5871–5876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kozel TR, et al. 2004. MAbs to Bacillus anthracis capsular antigen for immunoprotection in anthrax and detection of antigenemia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:5042–5047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Leppla SH. 1982. Anthrax toxin edema factor: a bacterial adenylate cyclase that increases cyclic AMP concentrations of eukaryotic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 79:3162–3166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li Q, et al. 2009. Anthrax LFn-PA hybrid antigens: biochemistry, immunogenicity, and protection against lethal Ames spore challenge in rabbits. Open Vaccine J. 2:92–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lisanby MW, et al. 2008. Cathelicidin administration protects mice from Bacillus anthracis spore challenge. J. Immunol. 181:4989–5000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Loving CL, Kennett M, Lee GM, Grippe VK, Merkel TJ. 2007. Murine aerosol challenge model of anthrax. Infect. Immun. 75:2689–2698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Loving CL, et al. 2009. Role of anthrax toxins in dissemination, disease progression, and induction of protective adaptive immunity in the mouse aerosol challenge model. Infect. Immun. 77:255–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lyons CR, et al. 2004. Murine model of pulmonary anthrax: kinetics of dissemination, histopathology, and mouse strain susceptibility. Infect. Immun. 72:4801–4809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Makino S, Uchida I, Terakado N, Sasakawa C, Yoshikawa M. 1989. Molecular characterization and protein analysis of the cap region, which is essential for encapsulation in Bacillus anthracis. J. Bacteriol. 171:722–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mayer-Scholl A, et al. 2005. Human neutrophils kill Bacillus anthracis. PLoS Pathog. 1:e23 c17 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0010023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mikesell P, Ivins BE, Ristroph JD, Dreier TM. 1983. Evidence for plasmid-mediated toxin production in Bacillus anthracis. Infect. Immun. 39:371–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mikszta JA, et al. 2006. Microneedle-based intradermal delivery of the anthrax recombinant protective antigen vaccine. Infect. Immun. 74:6806–6810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mikszta JA, et al. 2005. Protective immunization against inhalational anthrax: a comparison of minimally invasive delivery platforms. J. Infect. Dis. 191:278–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Milne JC, Collier RJ. 1993. pH-dependent permeabilization of the plasma membrane of mammalian cells by anthrax protective antigen. Mol. Microbiol. 10:647–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Milne JC, Furlong D, Hanna PC, Wall JS, Collier RJ. 1994. Anthrax protective antigen forms oligomers during intoxication of mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269:20607–20612 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Moayeri M, Haines D, Young HA, Leppla SH. 2003. Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin induces TNF-alpha-independent hypoxia-mediated toxicity in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 112:670–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Moayeri M, Leppla SH. 2009. Cellular and systemic effects of anthrax lethal toxin and edema toxin. Mol. Aspects Med. 30:439–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mogridge J, Cunningham K, Collier RJ. 2002. Stoichiometry of anthrax toxin complexes. Biochemistry 41:1079–1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mogridge J, Cunningham K, Lacy DB, Mourez M, Collier RJ. 2002. The lethal and edema factors of anthrax toxin bind only to oligomeric forms of the protective antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:7045–7048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mohamed N, et al. 2005. A high-affinity monoclonal antibody to anthrax protective antigen passively protects rabbits before and after aerosolized Bacillus anthracis spore challenge. Infect. Immun. 73:795–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Molin FD, et al. 2008. Ratio of lethal and edema factors in rabbit systemic anthrax. Toxicon 52:824–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Muehlbauer SM, et al. 2007. Anthrax lethal toxin kills macrophages in a strain-specific manner by apoptosis or caspase-1-mediated necrosis. Cell Cycle 6:758–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. O'Brien J, Friedlander A, Dreier T, Ezzell J, Leppla S. 1985. Effects of anthrax toxin components on human neutrophils. Infect. Immun. 47:306–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ostroff G, Axelrod DR, Bovarnick M. 1958. Antigenicity of polymers of glutamyl peptide on humans. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 99:345–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pellizzari R, Guidi-Rontani C, Vitale G, Mock M, Montecucco C. 2000. Lethal factor of Bacillus anthracis cleaves the N terminus of MAPKKs: analysis of the intracellular consequences in macrophages. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290:421–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Peterson JW, et al. 2007. Human monoclonal antibody AVP-21D9 to protective antigen reduces dissemination of the Bacillus anthracis Ames strain from the lungs in a rabbit model. Infect. Immun. 75:3414–3424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pitt ML, et al. 2001. In vitro correlate of immunity in a rabbit model of inhalational anthrax. Vaccine 19:4768–4773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Popov SG, et al. 2002. Lethal toxin of Bacillus anthracis causes apoptosis of macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 293:349–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Price BM, et al. 2001. Protection against anthrax lethal toxin challenge by genetic immunization with a plasmid encoding the lethal factor protein. Infect. Immun. 69:4509–4515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rhie GE, et al. 2003. A dually active anthrax vaccine that confers protection against both bacilli and toxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:10925–10930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ribot WJ, et al. 2006. Anthrax lethal toxin impairs innate immune functions of alveolar macrophages and facilitates Bacillus anthracis survival. Infect. Immun. 74:5029–5034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rivera J, et al. Bacillus anthracis produces membrane-derived vesicles containing biologically active toxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:19002–19007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Robertson DL, Tippetts MT, Leppla SH. 1988. Nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus anthracis edema factor gene (cya): a calmodulin-dependent adenylate cyclase. Gene 73:363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rosenshein MS, Price TH, Dale DC. 1979. Neutropenia, inflammation, and the kinetics of transfused neutrophils in rabbits. J. Clin. Invest. 64:580–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Schneerson R, et al. 2003. Poly(gamma-d-glutamic acid) protein conjugates induce IgG antibodies in mice to the capsule of Bacillus anthracis: a potential addition to the anthrax vaccine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:8945–8950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Scobie HM, Rainey GJ, Bradley KA, Young JA. 2003. Human capillary morphogenesis protein 2 functions as an anthrax toxin receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:5170–5174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Skoble J, et al. 2009. Killed but metabolically active Bacillus anthracis vaccines induce broad and protective immunity against anthrax. Infect. Immun. 77:1649–1663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Spencer RC. 2003. Bacillus anthracis. J. Clin. Pathol. 56:182–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Taft SC, Weiss AA. 2008. Neutralizing activity of vaccine-induced antibodies to two Bacillus anthracis toxin components, lethal factor and edema factor. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15:71–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Tournier JN, et al. 2005. Anthrax edema toxin cooperates with lethal toxin to impair cytokine secretion during infection of dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 174:4934–4941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vasconcelos D, et al. 2003. Pathology of inhalation anthrax in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Lab. Invest. 83:1201–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Vitale G, Bernardi L, Napolitani G, Mock M, Montecucco C. 2000. Susceptibility of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase family members to proteolysis by anthrax lethal factor. Biochem. J. 352 Pt. 3:739–745 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wang TT, Fellows PF, Leighton TJ, Lucas AH. 2004. Induction of opsonic antibodies to the gamma-d-glutamic acid capsule of Bacillus anthracis by immunization with a synthetic peptide-carrier protein conjugate. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 40:231–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wang TT, Lucas AH. 2004. The capsule of Bacillus anthracis behaves as a thymus-independent type 2 antigen. Infect. Immun. 72:5460–5463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Weiss S, et al. 2006. Immunological correlates for protection against intranasal challenge of Bacillus anthracis spores conferred by a protective antigen-based vaccine in rabbits. Infect. Immun. 74:394–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Welkos SL, Friedlander AM. 1988. Comparative safety and efficacy against Bacillus anthracis of protective antigen and live vaccines in mice. Microb. Pathog. 5:127–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Yee SB, Hatkin JM, Dyer DN, Orr SA, Pitt ML. 2010. Aerosolized Bacillus anthracis infection in New Zealand White rabbits: natural history and intravenous levofloxacin treatment. Comp. Med. 60:461–468 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Young JA, Collier RJ. 2007. Anthrax toxin: receptor binding, internalization, pore formation, and translocation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76:243–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Zaucha GM, Pitt LM, Estep J, Ivins BE, Friedlander AM. 1998. The pathology of experimental anthrax in rabbits exposed by inhalation and subcutaneous inoculation. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 122:982–992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zeng M, Xu Q, Pichichero ME. 2007. Protection against anthrax by needle-free mucosal immunization with human anthrax vaccine. Vaccine 25:3588–3594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]