Abstract

Ehrlichia chaffeensis is an obligately intracellular bacterium that exhibits tropism for mononuclear phagocytes and survives by evading host cell defense mechanisms. Recently, molecular interactions of E. chaffeensis tandem repeat proteins 47 and 120 (TRP47 and -120) and the eukaryotic host cell have been described. In this investigation, yeast two-hybrid analysis demonstrated that an E. chaffeensis type 1 secretion system substrate, TRP32, interacts with a diverse group of human proteins associated with major biological processes of the host cell, including protein synthesis, trafficking, degradation, immune signaling, cell signaling, iron metabolism, and apoptosis. Eight target proteins, including translation elongation factor 1 alpha 1 (EF1A1), deleted in azoospermia (DAZ)-associated protein 2 (DAZAP2), ferritin light polypeptide (FTL), CD63, CD14, proteasome subunit beta type 1 (PSMB1), ring finger and CCCH-type domain 1 (RC3H1), and tumor protein p53-inducible protein 11 (TP53I11) interacted with TRP32 as determined by coimmunoprecipitation assays, colocalization with TRP32 in HeLa and THP-1 cells, and/or RNA interference. Interactions between TRP32 and host targets localized to the E. chaffeensis morulae or in the host cell cytoplasm adjacent to morulae. Common or closely related interacting partners of E. chaffeensis TRP32, TRP47, and TRP120 demonstrate a molecular convergence on common cellular processes and molecular cross talk between Ehrlichia TRPs and host targets. These findings further support the role of TRPs as effectors that promote intracellular survival.

INTRODUCTION

Ehrlichia chaffeensis is an obligately intracellular bacterium causing human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (HME), an emerging human zoonosis (31). Ehrlichia have small genomes but are able to survive in mononuclear phagocytes, circumvent innate and adaptive host defense mechanisms, and replicate within membrane-bound cytoplasmic vacuoles, forming microcolonies (morulae) (12, 31). During infection, genes for numerous host cell processes are altered by Ehrlichia, including cell cycle and differentiation, immune response, membrane trafficking, lysosomal fusion, apoptosis, and signal transduction; however, the effector proteins involved in reprogramming the host cell have remained largely undefined (29, 34, 44).

Recently, E. chaffeensis tandem repeat proteins (TRPs) and ankyrin repeat proteins (Anks) were identified as effectors involved in complex strategies to modulate host cellular processes (23, 40, 45, 46). E. chaffeensis TRPs and Anks were initially identified and molecularly characterized as major immunoreactive proteins that elicit strong host antibody responses, including TRP32, TRP47, TRP75, TRP120, and Ank200 (7, 10, 24–26, 30). TRPs are type 1 secretion system (T1SS) substrates, and antibodies against linear epitopes in TRP32, TRP47, and TRP120 are protective against E. chaffeensis infection (17, 39). TRP32 is detected on both reticulate and dense-cored ehrlichiae, while TRP47 and TRP120 are expressed differentially on dense-cored ehrlichiae (10, 26, 33). Molecular pathogen-host interactions have been defined for TRP47 and TRP120, which interact with multiple host cell proteins associated with major biological processes, including transcription, translation, protein trafficking, and cell signaling (23, 40). Furthermore, TRP120 and Ank200 are translocated to the host cell nucleus and directly bind specific adenine- or G+C-rich motifs of numerous host genes associated with transcriptional regulation, signal transduction, and apoptosis (45, 46). However, the function and role of TRP32 in ehrlichial pathology are still unknown.

To better understand the role of ehrlichial TRPs in molecular host interactions and define ehrlichial effectors and molecular mechanisms involved in ehrlichial pathobiology, we used a yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) assay to identify molecular TRP32-host interactions. We determined that a single carboxyl-terminal domain of E. chaffeensis TRP32 interacts with a large group of eukaryotic proteins involved in multiple cellular processes and has molecular cross talk with the TRP120 network. Thus, similar to TRP47 and TRP120, TRP32 also appears to play important roles in ehrlichial molecular pathobiology through interactions with a diverse group of host cell proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and cultivation of E. chaffeensis.

Human cervical epithelial adenocarcinoma cells (HeLa) were propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT). Human monocytic leukemia cells (THP-1) were propagated in RPMI medium 1640 with l-glutamine and 25 mM HEPES buffer (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 2.5 g/liter d-(+)-glucose (Sigma), and 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone). E. chaffeensis (Arkansas strain) was cultivated in THP-1 cells as previously described (40).

Antibodies and siRNAs.

Rabbit or mouse anti-TRP32 antibodies have been described previously (24). Other antibodies used in this study were mouse anti-human CD14, CD63, ferritin light chain (FTL), α-tubulin, rabbit anti-human elongation factor 1 alpha 1 (EF1A1), and ring finger and CCCH-type domain 1 (RC3H1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse anti-DAZ (deleted in azoospermia)-associated protein 2 (DAZAP2), rabbit anti-proteasome subunit beta type 1 (PSMB1), and tumor protein p53-inducible protein 11 (TP53I11) (Sigma), and rabbit anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) and mouse anti-GAL4 DNA-binding domain (DNA-BD) tag (Clonetech, Mountain View, CA). All antibodies used for immunofluorescence were tested by the vendor to ensure the specificity and confirmed by Western immunoblotting, immunofluorescent microscopy, or both. All small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) used in this study, including human CD14, CD63, DAZAP2, EF1A1, control-A, and fluorescein-conjugated control-A siRNA, were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Yeast two-hybrid system.

Protein-protein interactions were identified using the Matchmaker Gold yeast two-hybrid system (Clontech) that included all yeast strains, yeast media and supplements, vectors, and the yeast transformation system.

E. chaffeensis TRP32 cloning, autoactivation test, and expression in yeast.

The coding region of TRP32 (GenBank accession number AF121232) and amino-terminal TRP32 (TRP32N; amino acids 1 to 17) were amplified by PCR from E. chaffeensis genomic DNA using forward (5′-GGCGAATTCATGTCACAATTCTCTGAAGA) and reverse (5′-GGCGTCGACCTCTAAACTACTTTCACTACAGTG for TRP32 and 5′-GGCGGATCCATCAAAAGGCATTTGTATATTAC for TRP32N) (restriction enzyme sites in boldface; Sigma-Genosys, Woodlands, TX) primers and cloned into the EcoRI-SalI/BamHI site of pGBKT7 vector containing the GAL4 DNA-BD.

A similar approach to that described above was used to clone tandem repeats (TRP32TR; amino acids 18 to 138) and carboxy-terminal (TRP32C; amino acids 135 to 198) TRP32 fragments into pGBKT7, except that an In-Fusion PCR cloning kit (Clontech) was used. The primers used for TRP32TR and TRP32C amplification from E. chaffeensis genomic DNA included the In-Fusion cloning leader sequence CATGGAGGCCGAATTC at the 5′ end of the forward primer and GCAGGTCGACGGATCC at the 5′ end of the reverse primer. Fragment-specific primer sequences (Sigma-Genosys) were as follows: TRP32TR (forward, 5′-TCTGATTCACATGAGCCTT, and reverse, 5′-TCCATATACTACATTTTTAGC) and TRP32C (forward, 5′-GTAGTATATGGACAAGACCATGTTAG, and reverse, 5′-CTCTAAACTACTTTCACTACAGTGATG).

To examine whether the bait (TRP32) autonomously activated (autoactivated) the reporter genes in yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) strain Y2HGold in the absence of a prey protein, Y2HGold cells were transformed with bait plasmid pGBKT7-TRP32, -TRP32N, -TRP32TR, or -TRP32C and plated on minimal synthetically defined (SD) medium without tryptophan (SD/−Trp); SD/−Trp medium supplemented with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-d-galactopyranoside (X-α-Gal) and aureobasidin A (SD/−Trp/X/A); and SD triple-dropout (TDO) medium (SD medium without Trp, histidine [His], and adenine [SD/−Trp/−His/−Ade]) supplemented with X-α-Gal (TDO/X).

The expression of bait protein TRP32C (GAL4 DNA-BD fused) in yeast was confirmed by Western immunoblotting using transformed yeast cell lysates probed with mouse anti-GAL4 DNA-BD antibody (1:2,000). Yeast protein extracts were prepared by the urea-sodium dodecyl sulfate method as described in Clontech's Yeast Protocols Handbook (7a).

Yeast two-hybrid assay.

The Matchmaker human bone marrow library (Clontech), a high-complexity cDNA library cloned into the yeast GAL4 activation domain (GAL4-AD) vector pGADT7-Rec and pretransformed into S. cerevisiae host strain Y187, was screened by yeast mating with bait strain Y2HGold containing pGBKT7-TRP32C according to the manufacturer's protocol. A positive control was created by mating Y2HGold containing pGBKT7-p53 (murine p53 protein) with Y187 containing pGADT7-T (simian virus 40 large T antigen), and Y2HGold containing pGBKT7-Lam (human nuclear lamin) was mated with Y187 containing pGADT7-T as a negative control. Positive clones expressing prey proteins interacting with TRP32C (bait) were selected on SD quadruple-dropout (QDO) medium (SD medium without Trp, leucine [Leu], His, and Ade [SD/−Trp/−Leu/−His/−Ade]) supplemented with X-α-Gal and aureobasidin A (QDO/X/A). Blue colonies of normal size were segregated three times on SD double-dropout (DDO) medium (SD medium without Trp and Leu [SD/−Leu/−Trp]) containing X-α-Gal (DDO/X), and the prey cDNA inserts were amplified by colony PCR and then sequenced in the UTMB Protein Chemistry Core Laboratory.

Confirmation of positive interactions by cotransformation.

The prey plasmids responsible for positive interactions were rescued from segregated colonies using an Easy yeast plasmid isolation kit (Clontech), transformed into Escherichia coli Fusion-Blue (Clontech), and reisolated. To distinguish positive from false-positive interactions, Y2HGold yeast cells were cotransformed with bait (pGBKT7-TRP32C) and prey plasmids or with empty pGBKT7 and the prey plasmids as controls. The positive interactions were confirmed by selection on QDO/X/A.

Cotransfection of mammalian cells and co-IP.

A Matchmaker chemiluminescent coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) system (Clontech) was used to confirm interactions between bait and prey proteins identified by Y2H in mammalian cells. Briefly, two mammalian expression vectors, pAcGFP1-C and pProLabel-C, which encode a fluorescent Aequorea coerulescens green fluorescent protein (AcGFP1) tag and an enzymatic ProLabel (PL; an ∼6-kDa fragment of β-galactosidase) tag, respectively, were used for generation of N-terminal AcGFP1-bait and PL-prey fusion proteins. The bait TRP32C was amplified from pGBK-TRP120 and cloned in-frame downstream of the AcGFP1 tag of pAcGFP1-C using In-Fusion PCR cloning, while the prey gene was amplified from pGADT7-prey and cloned in-frame downstream of the PL tag of pProLabel-C.

Plasmid pAcGFP1-C (control without insert) or pAcGFP1-TRP32C and pProLabel-prey were cotransfected into HeLa cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), and the expression of GFP was confirmed under an inverted fluorescence microscope (IX71; Olympus, Japan) 2 days posttransfection (p.t.). Then, interacting proteins were immunoprecipitated according to the manufacturer's protocol, and PL activity (in relative light units [RLUs]) was measured at different time intervals after the addition of substrate using a Veritas microplate luminometer (Turner Biosystems, Sunnyvale, CA). Statistical differences between experimental groups were assessed with the two-tailed Student's t test, and significance was indicated by a P value of <0.05.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Transfected (pAcGFP1-TRP32C or pAcGFP1-empty) HeLa cells (2 days p.t.) and uninfected or E. chaffeensis-infected THP-1 cells (3 days postinfection [p.i.]) were collected, and the indirect immunofluorescent-antibody assay was performed as previously described (23), except that anti-CD14, -CD63, -DAZAP2, -EF1A1, -FTL, -PSMB1, -RC3H1, or -TP53I11 antibodies (1:100) and anti-TRP32 antibody (1:10,000) were used.

RNA interference.

THP-1 cells (2 × 105/well on a 24-well plate) were transfected with 20 pmol human CD14, CD63, DAZAP2, or EF1A1 siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). A control-A siRNA consisting of a scrambled sequence was used as a negative control, and a fluorescein-conjugated control-A siRNA was used as a control to monitor transfection efficiency. At 1 day p.t., the cells were infected by cell-free E. chaffeensis at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ∼50. Then, the cells were collected at 1, 2, and 3 days p.i. and subjected to quantitative PCR (qPCR), reverse transcription (RT)-PCR, and Western blotting.

Quantification of E. chaffeensis.

Total DNA was extracted from E. chaffeensis-infected THP-1 cells with a DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The E. chaffeensis dsb gene was amplified with forward primer 5′-TTGCAAAATGATGTCTGAAGATATGAAACA and reverse primer 5′-GCTGCTCCACCAATAAATGTATCTCCTA (Sigma-Genosys) (9), and a standard plasmid, pBAD-dsb, was constructed by cloning the dsb gene using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). The plasmid copy number for the standards was calculated using the following formula: plasmid copy/μl = [(plasmid concentration g/μl)/(plasmid length in base pairs × 660)] × 6.022 × 1023. Real-time PCR was performed using iQ SYBR green supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and dsb primers in a Mastercycler EP Realplex2 S apparatus (Eppendorf, Germany). The thermal cycling protocol consisted of an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 2 min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 65°C for 30 s. The absolute E. chaffeensis dsb copy number in the cells was determined against the standard curve.

RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from THP-1 cells using Tri Reagent solution (Ambion, Austin, TX) and treated with Turbo DNase (Ambion) to remove contaminating genomic DNA according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then, cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) and PCR was performed using PCR HotMaster mix (5 PRIME, Germany) and human gene-specific primer pairs (Santa Cruz). The thermal cycling profile was as follows: 95°C for 3 min and 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, followed by a 72°C extension for 5 min and a 4°C hold.

Western immunoblotting.

The THP-1 cell lysates were prepared using CytoBuster protein extraction reagent (Novagen/EMD, Gibbstown, NJ), separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and transferred to nitrocellulose. Then, Western immunoblotting was performed as previously described (27), except that the human protein antibodies were diluted 1:100.

Statistics.

The statistical differences between experimental groups were assessed with the two-tailed Student's t test, and significance was indicated by a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

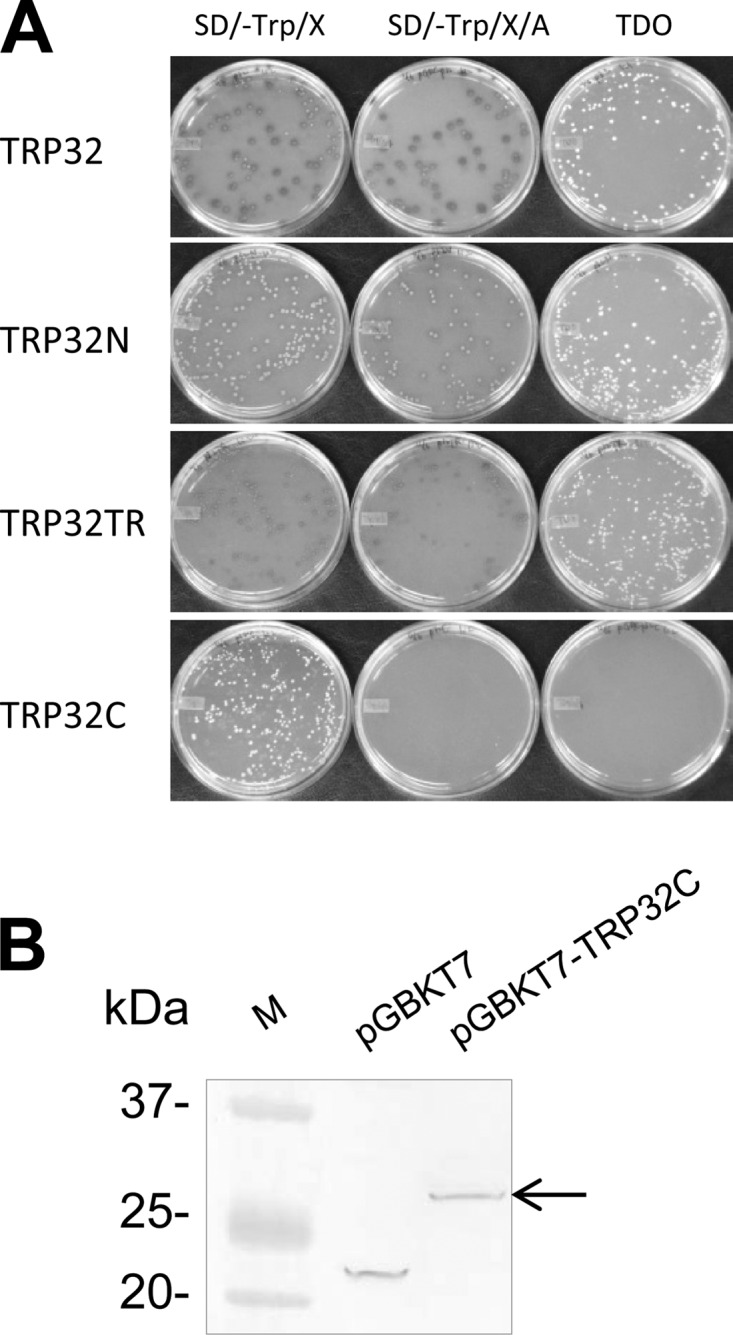

Validation of E. chaffeensis TRP32 regions for a yeast two-hybrid system.

E. chaffeensis TRP32 is a 198-amino acid, highly acidic (pI 3.8) protein containing four nearly identical 30-mer TRs flanked by N (17 amino acids) and C (61 amino acids) termini (26). Y2HGold cells were transformed with bait plasmid pGBKT7-TRP32, -TRP32N, -TRP32TR, or -TRP32C and plated. After 3 to 5 days of incubation, many colonies were observed on the SD/−Trp, SD/−Trp/X/A, and TDO/X plates of pGBKT7-TRP32-, -TRP32N-, or -TRP32TR-transformed yeast cells, indicating that TRP32, TRP32N, and TRP32TR could autoactivate all four reporter genes in yeast strain Y2HGold in the absence of a prey protein (Fig. 1A). Many colonies were also observed on the SD/−Trp plate of pGBKT7-TRP32C-transformed yeast cells, but no growth was observed on SD/−Trp/X/A and TDO/X plates, confirming a lack of autoactivation by TRP32C (Fig. 1A). To examine the toxicity of TRP32C in yeast cells, Y2HGold cells transformed with pGBKT7-empty or pGBKT7-TRP32C were grown in both solid and liquid media. No significant differences in yeast growth in solid or liquid medium containing bait and empty plasmids were observed, demonstrating that the bait was nontoxic to yeast.

Fig 1.

Autoactivation test of TRP32 domains and detection of TRP32C expression in yeast. (A) Yeast cells containing pGBKT7-TRP32, -TRP32N, -TRP32TR, or -TRP32C were screened and selected with SD/−Trp, SD/−Trp/X/A, and TDO medium. (B) Expression of GAL4 DNA-BD/TRP32C fusion protein in yeast (arrow) was determined by immunoblotting of yeast cell extracts transformed with pGBKT7 (empty vector) or pGBKT7-TRP32C using the anti-GAL4 DNA-BD antibody.

To confirm the GAL4 DNA-BD–TRP32C fusion protein expression in yeast, yeast proteins were extracted from Y2HGold cells transformed with pGBKT7-empty or pGBKT7-TRP32C, and the GAL4 DNA-BD tag only or GAL4 DNA-BD–TRP32C fusion protein was detected by Western immunoblotting with an anti-GAL4 DNA-BD monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1B). The fusion protein exhibited a molecular mass (∼29 kDa) consistent with that predicted (22 kDa of GAL4 DNA-BD tag plus 7 kDa of TRP32C) based on the amino acid sequence.

Analysis of E. chaffeensis TRP32C interactions with human proteins using a yeast two-hybrid system.

By yeast two-hybrid screening using yeast mating, ∼35% mating efficiency was achieved, and ∼37 million diploid clones were screened. In total, 42 yeast colonies with blue color and normal size were observed and selected from SD/−Trp/−Leu/−Ade/−His/X/A (QDO/X/A) plates for identification of potential positive clones that exhibited bait and prey protein-protein interactions. After segregating the colony three times, yeast colony PCR was performed, followed by DNA sequencing to eliminate the duplicate clones and identify interacting targets. Twenty-two different potentially interacting human proteins were identified, and the seven most abundant (>2) clones in order of frequency were translation elongation factor 1 alpha 1 (EF1A1), DAZ-associated protein 2 (DAZAP2), CD63, ferritin light polypeptide (FTL), immunoglobulin heavy constant alpha 1 (IGHA1), immunoglobulin heavy chain variable domain (IGHV), and transketolase (TKT) (Table 1). The target proteins were associated with major biological processes, including protein synthesis, intracellular trafficking and degradation, immune signaling, cell signaling, iron metabolism, glycometabolism, lipid metabolism, hematopoiesis, transmembrane transport, and apoptosis.

Table 1.

Summary of 22 human proteins that interact with E. chaffeensis TRP32 determined by yeast two-hybrid assay

| Category | Interacting human proteina | NCBI Gene ID | Abundanceb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein synthesis, degradation, and | Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 alpha 1 (EF1A1) | 1915 | 9 |

| intracellular trafficking | CD63 molecule (CD63) | 967 | 2 |

| Proteasome (prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type 1 (PSMB1) | 5689 | 1 | |

| Ring finger and CCCH-type domains 1 (RC3H1) | 149041 | 1 | |

| Elastase, neutrophil expressed (ELANE) | 1991 | 1 | |

| Coatomer subunit epsilon (COPE) | 11316 | 1 | |

| TBC1 domain family, member 10B (TBC1D10B) | 26000 | 1 | |

| Cell signaling | DAZ-associated protein 2 (DAZAP2) | 9802 | 5 |

| Immune signaling | Immunoglobulin heavy constant alpha 1 (IGHA1) | 3493 | 2 |

| Immunoglobulin heavy chain variable domain (IGHV) | 100132941 | 2 | |

| Immunoglobulin lambda-like polypeptide 5 (IGLL5) | 100423062 | 1 | |

| CD14 molecule (CD14) | 929 | 1 | |

| Iron metabolism, glycometabolism, | Ferritin, light polypeptide (FTL) | 2512 | 2 |

| and lipid metabolism | Transketolase (TKT) | 7086 | 2 |

| ST6 (alpha-N-acetyl-neuraminyl-2,3-beta-galactosyl-1,3)-N-acetylgalactosaminide alpha-2,6-sialyltransferase 4 (ST6GALNAC4) | 27090 | 1 | |

| Mitochondrial hydroxyacyl-coenzyme (CoA) A dehydrogenase (HADH) | 3033 | 1 | |

| Mitochondrial trans-2-enoyl-CoA reductase (MECR) | 51102 | 1 | |

| Hematopoiesis | Glucocorticoid-induced transcript 1 protein (GLCCI1) | 113263 | 1 |

| Hematopoietically expressed homeobox (HHEX) | 3087 | 1 | |

| Apoptosis | Tumor protein p53 inducible protein 11 (TP53I11) | 9537 | 1 |

| Transmembrane transport | Solute carrier family 43, member 3 (SLC43A3) | 29015 | 1 |

| Unknown | Selenium binding protein 1 (SELENBP1) | 8991 | 1 |

Selectively confirmed target proteins in this study are identified in boldface.

Number of yeast clones obtained by Y2H screening.

Confirmation of interactions by cotransformation and coimmunoprecipitation.

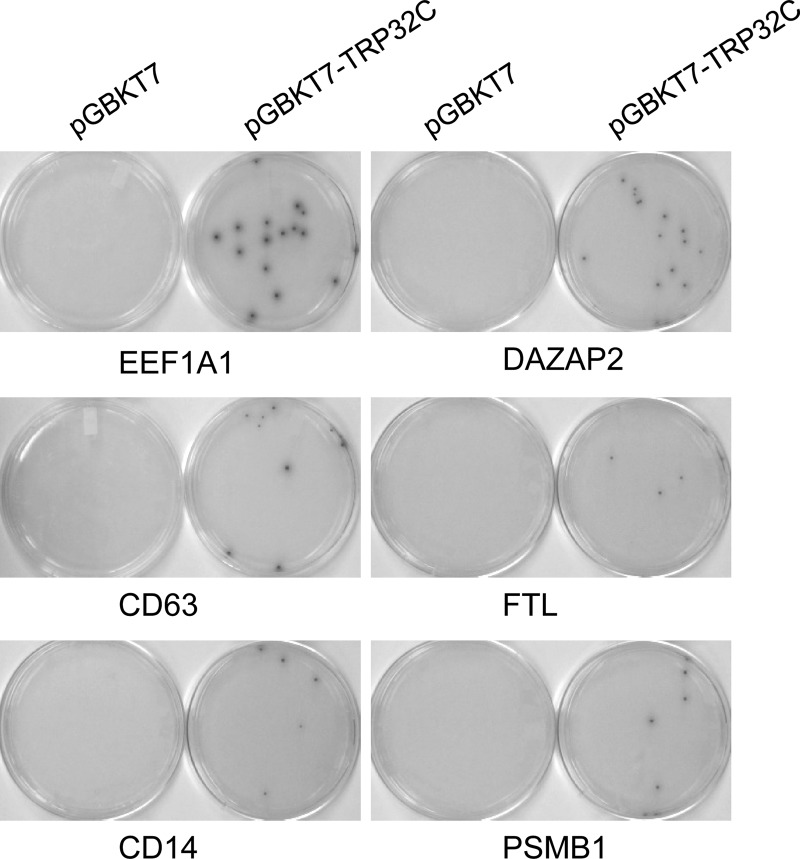

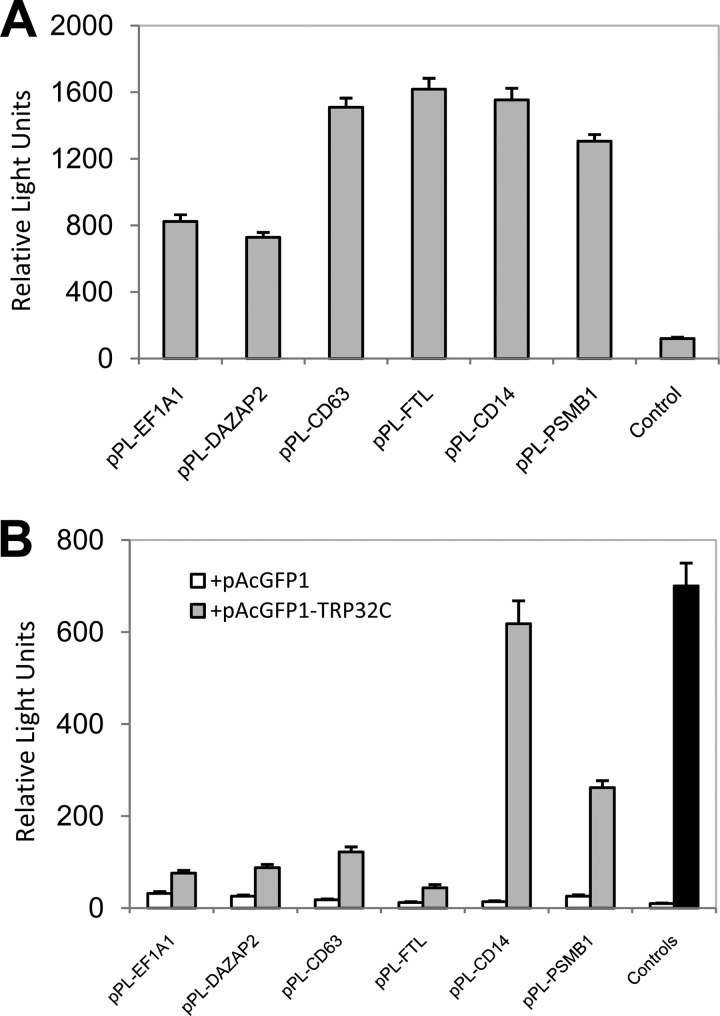

To confirm the true interactions, eight candidate preys of high priority for the Ehrlichia-host interaction study were selected from the above-described 22 clones, including EF1A1, DAZAP2, CD63, FTL, CD14, proteasome subunit beta type 1 (PSMB1), ring finger and CCCH-type domains 1 (RC3H1), and tumor protein p53-inducible protein 11 (TP53I11). Cotransformation assays were performed in yeast with bait and prey plasmids, and interactions in yeast were confirmed with all these prey proteins (Fig. 2, showing interactions of TRP32 with six prey proteins: EF1A1, DAZAP2, CD63, FTL, CD14, and PSMB1). In order to further examine the interaction of TRP32 with these prey proteins in mammalian cells by co-IP, eight prey genes were respectively cloned into the mammalian expression vector pProLabel-C and six proteins (EF1A1, DAZAP2, CD63, FTL, CD14, and PSMB1) were expressed and detected by PL chemiluminescence (Fig. 3A). Co-IP confirmed a direct interaction between TRP32C and all six expressed prey proteins. The relative strengths of the interactions between TRP32C and EF1A1, DAZAP2, CD63, FTL, CD14, and PSMB1 were 2.4, 3.4, 6.8, 3.7, 44.1, and 10.1 times higher than those of the respective controls (AcGFP1 without TRP32; P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). TRP32 interacted with each prey protein specifically and differentially, as demonstrated by high relative physical interaction values (from 618 RLU for CD14 to 44 RLU for FTL) (Fig. 3B). To confirm the specificity of the protein-protein interaction, HeLa cells were cotransfected with pAcGFP1-TRP32C and pProLabel-C, and co-IP was performed. The relatively low RLU value (12) indicated that there was no protein-protein interaction and demonstrated that the presence of a specific prey protein was required for TRP32-prey protein interaction (Fig. 3B). This experiment confirmed the Y2H results and also confirmed that TRP32C interacted most strongly with CD14, followed by PSMB1, CD63, DAZAP2, EF1A1, and FTL.

Fig 2.

Confirmation of positive interactions in yeast by cotransformation. Y2HGold yeast cells were cotransformed with the bait plasmid pGBKT7-TRP32C and one of the prey plasmids pGADT7-EF1A1, -DAZAP2, -CD63, -FTL, -CD14, and -PSMB1. As a control, pGBKT7 (empty vector) was used to cotransform with each prey plasmid. The positive interactions were confirmed by selection on QDO/X/A plates.

Fig 3.

E. chaffeensis TRP32 interactions with multiple human proteins detected by chemiluminescent coimmunoprecipitation. AcGFP1 (without insert) or AcGFP1-TRP32C was coexpressed with PL-EF1A1, -DAZAP2, -CD63, -FTL, -CD14, or -PSMB1 fusion protein in HeLa cells. A positive control (B, Controls, black bar) was performed by coexpressing AcGFP1-p53 (human tumor suppressor p53 protein) and PL-T (simian virus 40 large T antigen), while AcGFP1-TRP32C (B, Controls, white bar) was coexpressed with PL (without insert) as the negative control. ProLabel (PL) activity in relative light units was measured 1 h after the addition of substrate. The results were from three independent experiments, and the values are shown as means ± standard deviations. (A) Relative strengths of expression of six human proteins (EF1A1, DAZAP2, CD63, FTL, CD14, and PSMB1) were detected in HeLa cells by PL chemiluminescence activity. Control, pPL-C. (B) Relative strengths of interaction of AcGFP1-TRP32C with PL-EF1A1, -DAZAP2, -CD63, -FTL, -CD14, and -PSMB1 are shown. TRP32C, carboxyl-terminal TRP32.

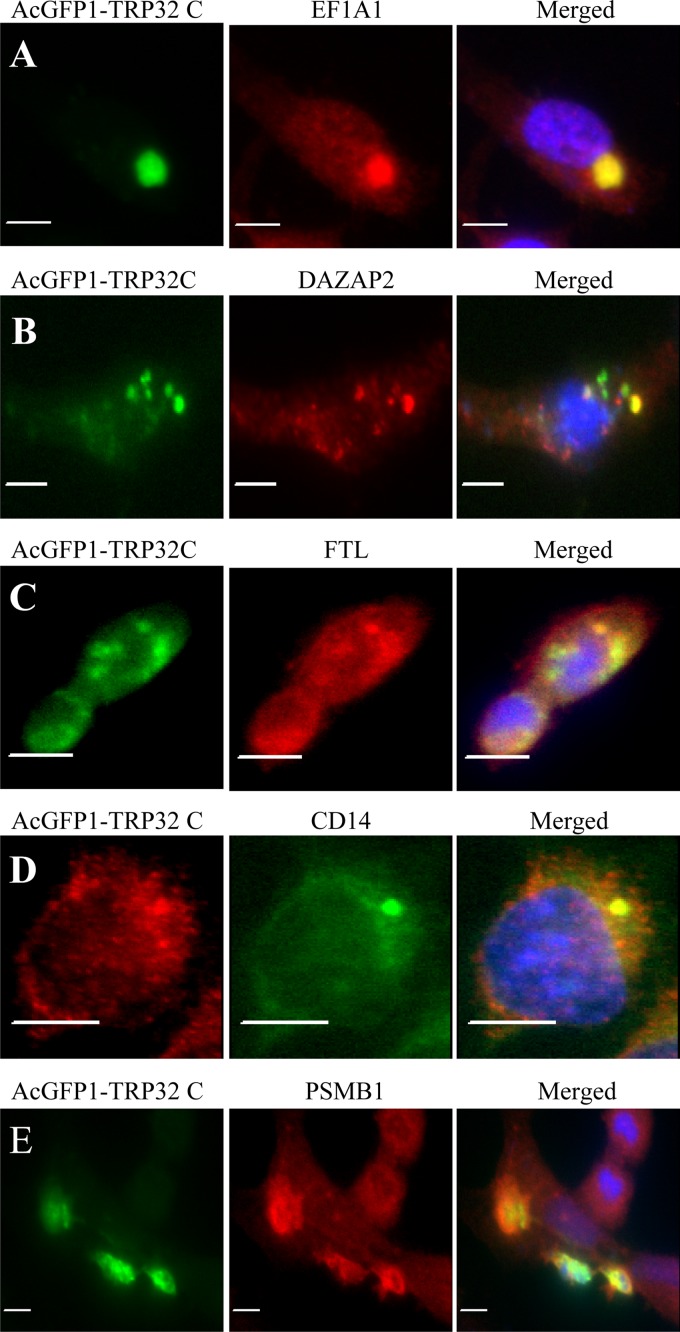

Recombinant E. chaffeensis TRP32C (AcGFP1-TRP32C) colocalizes with human target proteins in HeLa cells.

Interactions between TRP32C and the seven selected proteins EF1A1, DAZAP2, FTL, CD14, PSMB1, RC3H1, and TP53I11 were examined in mammalian cells (HeLa) transfected with TRP32C expression vector. CD63 is present on the cell surface as well as in late endosomes/lysosomes and was previously reported to be sensitive to detergent extraction after fixation with paraformaldehyde (18); therefore, interaction of TRP32C with CD63 in HeLa cells was not examined. Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that recombinant TRP32C colocalized with all seven host targets, but five proteins (EF1A1, DAZAP2, FTL, CD14, and PSMB1) exhibited the strongest colocalization (Fig. 4A to E). Recombinant E. chaffeensis TRP32C and host cell proteins exhibited both diffuse and punctate cytoplasmic colocalization in the cell (Fig. 4A to E).

Fig 4.

Colocalization of EF1A1, DAZAP2, FTL, CD14, and PSMB1 with AcGFP-TRP32C in HeLa cells. pAcGFP1-TRP32C-transfected HeLa cells (2 days posttransfection) were labeled and observed by fluorescence microscopy. (A to E) The AcGFP-TRP32C (green) and anti-EF1A1, -DAZAP2, -FTL, -CD14, and -PSMB1 (red) signals were merged with 4,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining of nuclei (blue). Bars, 10 μm.

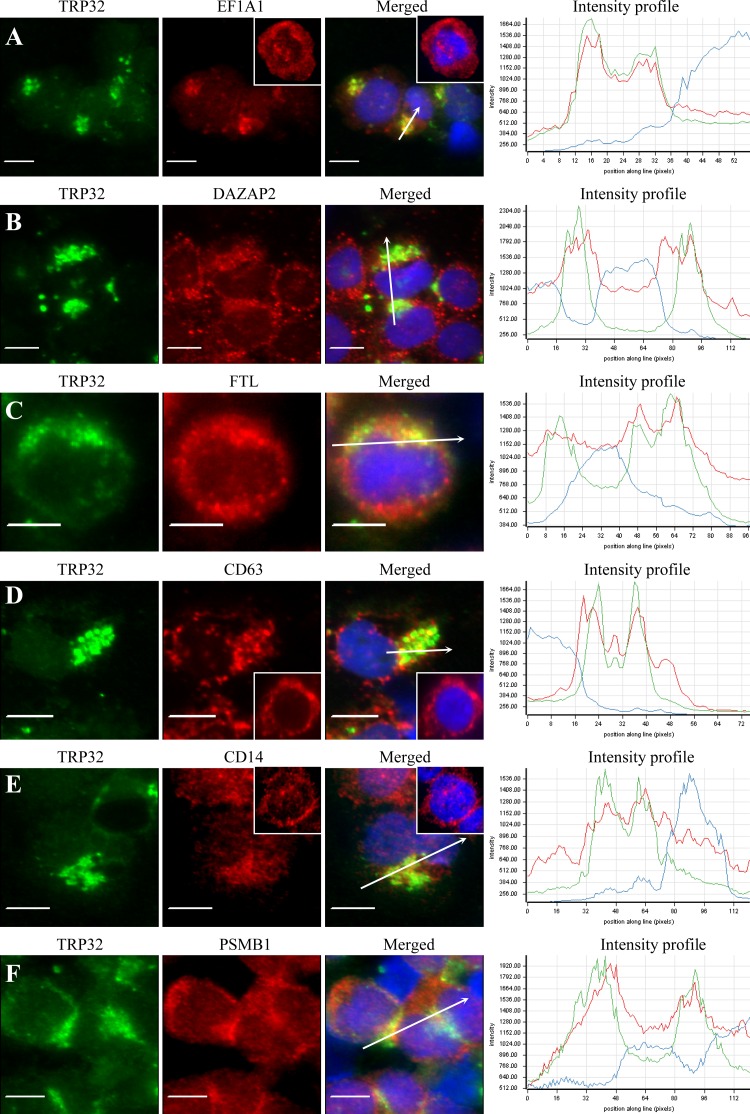

TRP32-expressing ehrlichiae colocalize with human target proteins in E. chaffeensis-infected THP-1 cells.

Consistent with our previous report (26), we observed that both dense-cored and reticulate E. chaffeensis cells reacted with anti-TRP32 antibody (data not shown), in contrast to anti-TRP47 and anti-TRP120 antibodies that reacted only with dense-cored ehrlichiae (10, 33). Consistent with the colocalization in HeLa cells, double-immunofluorescence labeling of E. chaffeensis-infected THP-1 cells revealed that eight identified host targets colocalized with morulae (green) that stained with anti-TRP32 antibody, but six proteins, EF1A1, DAZAP2, FTL, CD63, CD14, and PSMB1 (red), exhibited the strongest colocalization (Fig. 5A to F). Target proteins colocalized with the morulae or in the host cell cytoplasm adjacent to the morula membrane. To further examine the distribution and colocalization of host proteins with TRP32-expressing E. chaffeensis morulae, fluorescence intensity profiles across the colocalized regions in the fluorescence images were analyzed (Fig. 5A toF, right). The intensity analysis demonstrated that TRP32 (green curve), and EF1A1, DAZAP2, FTL, CD63, CD14, and PSMB1 (red curve) had consistent colocalization with morulae and revealed a similar pattern of elevated peaks across and adjacent to the morula profile. Redistribution of TRP32 target proteins in E. chaffeensis-infected cells compared to their distribution in uninfected cells was observed; for example, EF1A1, CD63, and CD14 were mostly associated with morulae in infected THP-1 cells (Fig. 5A, D, and E), while in uninfected THP-1 cells, EF1A1 and CD63 were diffusely distributed, mainly in the cytoplasm, and CD14 was mostly associated with cell membranes (Fig. 5A, D, and E, insets).

Fig 5.

Colocalization of EF1A1, DAZAP2, FTL, CD63, CD14, and PSMB1 with TRP32 in E. chaffeensis-infected THP-1 cells. (A to F) Fluorescence microscopy and intensity profiles of infected THP-1 cells stained with 4,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue, showing the nucleus), anti-TRP32 (green), and anti-EF1A1, -DAZAP2, -CD63, -FTL, -CD14, and -PSMB1 (red) show colocalization of E. chaffeensis TRP32-labeled morulae with EF1A1, DAZAP2, CD63, FTL, CD14, and PSMB1. The white arrows in the fluorescence image indicate the areas selected for fluorescence intensity profile analyses, which are displayed in graph form. The x axis shows the position along the line (pixels), and the y axis shows the fluorescence intensity. The insets (A, D, and E) show the distribution of EF1A1, CD63, and CD14 in uninfected THP-1 cells. Bar, 10 μm.

TRP32-host interactions are involved in E. chaffeensis infection.

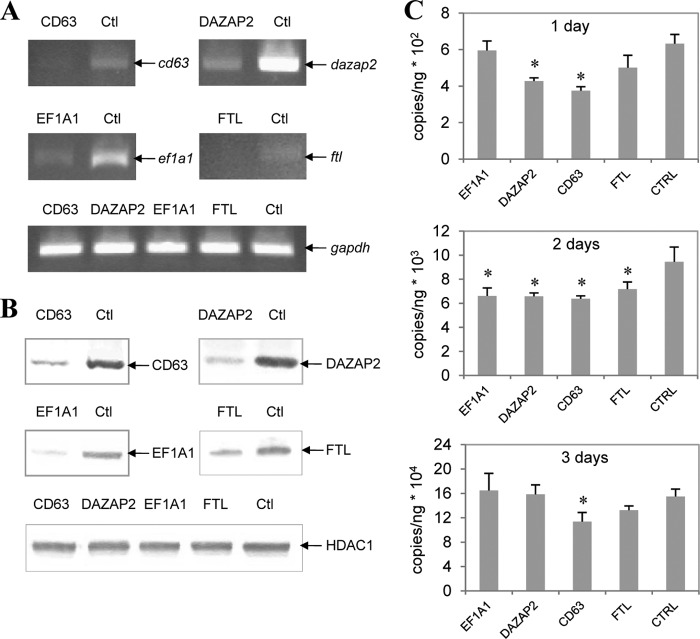

We further confirmed the role of TRP32-host protein interactions in the infection of E. chaffeensis by transfection of EF1A1, DAZAP2, CD63, or FTL siRNA into THP-1 cells. Both the mRNA and protein amounts of these targets were reduced in siRNA-transfected cells compared to their amounts in cells transfected with unrelated control siRNA (Fig. 6A and B). The decrease of target proteins inhibited E. chaffeensis infection (Fig. 6C), indicating that host proteins identified as TRP32 targets play a role in E. chaffeensis infection. The infection time course study showed that at 2 days p.i., the decrease of all four target proteins inhibited E. chaffeensis infection, while the decrease of CD63 and DAZAP2 inhibited infection at 1 day p.i. and the decrease of CD63 only still inhibited infection at 3 days p.i. (Fig. 6C).

Fig 6.

TRP32 interactions with host EF1A1, DAZAP2, CD63, and FTL are involved in E. chaffeensis infection. THP-1 cells were transfected with EF1A1, DAZAP2, CD63, FTL, or control siRNA and then infected with E. chaffeensis. (A and B) At 2 days p.i., RT-PCR and Western blotting were performed to compare the amounts of mRNA (A) and protein (B), respectively. (C) Bacterial numbers were determined by qPCR at 1, 2, and 3 days p.i. Results are from three independent experiments, and the values are means ± standard deviations (*, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Recently, we determined for the first time that ehrlichial TRP47, TRP120, and Ank200 are effector proteins that are involved in molecular interactions with multiple host proteins and/or chromatin (genes) associated with transcription and regulation, protein trafficking, and cell signaling (23, 40, 45, 46). These findings highlight the importance of defining and understanding interactions between intracellular bacteria and eukaryotes, the characteristics of bacterial effectors, and the complex mechanisms whereby pathogens modulate host cell processes. In this study, we demonstrated that TRP32, a recently reported T1SS substrate, is an effector protein involved in direct interactions with a diverse group of eukaryotic proteins, including the targets that are associated with TRP120, suggesting that similar to TRP47, TRP120, and Ank200, TRP32 is also a multifunctional protein involved in a complex molecular strategy to alter host cell processes. This study expands on our previous conclusion that an array of diverse interactions is occurring between ehrlichial effectors and host proteins in vivo and further indicates that ehrlichial effector proteins, such as TRP32, TRP47, TRP120, and Ank200, play important roles in ehrlichial modulation of host cells through protein-protein or protein-DNA interactions.

Some TRP32 eukaryotic target proteins, including EF1A1, DAZAP2, FTL, CD63, CD14, and PSMB1, were confirmed by coimmunoprecipitation, colocalization with TRP32 in HeLa/THP-1 cells, and RNA interference assays. Yeast two-hybrid assay revealed that the EF1A1 protein was the most frequently identified interacting partner with TRP32. EF1A1 is an isoform of the alpha subunit of the elongation factor-1 complex (EF1A), which is responsible for the enzymatic delivery of aminoacyl tRNAs to the ribosome. In eukaryotes, EF1A is highly conserved and the second most abundant protein after actin, constituting 1 to 2% of the total proteins in normal growing cells (8). However, EF1A is also one of the most important multifunctional eukaryotic proteins, which has numerous other functions besides its role in translation, including cytoskeletal remodeling, enzyme regulation, apoptosis, and oncogenesis (13). We previously identified EF1A1 as a potential interacting partner of E. chaffeensis TRP120 (23); therefore, both TRP32 and TRP120 may interact with EF1A1 in order to suppress the protein translation of the host cell and serve multiple functions to favor ehrlichial survival.

DAZAP2 was the second most frequently identified interacting partner with TRP32. DAZAP2 was originally identified as a highly conserved, small, proline-rich protein which interacts with the deleted in azoospermia (DAZ) and the DAZ-like (DAZL) proteins through the DAZ-like repeats (36). Subsequently, this protein was also found to interact with the transforming growth factor-beta signaling molecule SARA (Smad anchor for receptor activation), eukaryotic initiation factor 4G, and an E3 ubiquitinase that regulates its stability in splicing factor containing nuclear speckles (14, 15, 42). Thus, DAZAP2 may function in various biological and pathological processes, including spermatogenesis, cell signaling and transcription regulation, formation of stress granules during translation arrest, RNA splicing, and the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma (22). Interaction of TRP32 with DAZAP2 may play diverse roles in ehrlichial pathobiology in the host cell.

E. chaffeensis enters the monocyte through caveola-mediated endocytosis, residing and multiplying within a cytoplasmic vacuole that phenotypically resembles an early endosome and does not fuse with lysosomes, thus providing protection from nonoxidative and oxidative damage (34). However, how Ehrlichia modulates host cell vesicular trafficking to avoid lysosomal fusion remains unclear. The TRP32-CD63 interaction may play a role in this process. CD63 is a member of the tetraspanin family, which comprises a large superfamily of cell surface-associated membrane proteins characterized by four transmembrane domains (4). As the first characterized tetraspanin, CD63 is present in late endosomes and lysosomes as well as the cell surface, and recent studies suggest the existence of CD63 in caveola-mediated endocytosis and trafficking from the cell surface to endosomes/lysosomes (5, 32). As a regulator of protein trafficking of its interaction partners, most of the described CD63 functions take place at the cell surface, and no specific function of CD63 in endosomes/lysosomes has been described thus far (32). Through interacting with CD63, TRP32 may help ehrlichial internalization and prevent early endosomal maturation into late endosomes, thereby avoiding the late-endosome-lysosome pathway.

The replicative inclusions of E. chaffeensis accumulate transferrin receptors (TfRs) and have access to the labile iron pool (3). At the early stage of infection, E. chaffeensis is probably killed in human monocytes by depletion of cytoplasmically available iron derived from transferrin (2). The addition of Anaplasma phagocytophilum to neutrophils results in an increase in ferritin light chain (FTL) transcription and a concomitant rise in ferritin protein levels (6). These studies suggest that E. chaffeensis and A. phagocytophilum infections alter host cell iron acquisition and metabolism, yet the mechanisms involved are relatively unknown with the exception that an Ehrlichia ferric ion-binding protein has been identified and its iron binding properties determined (11). Our Y2H data identified E. chaffeensis TRP32 as an interacting partner of the host FTL. Ferritin is the major intracellular iron storage protein in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and therefore, TRP32 may recruit host FTL to stabilize the labile iron pool to maintain the ehrlichial replication.

CD14 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein preferentially expressed on the surfaces of monocytes/macrophages and was the first pattern recognition receptor (PRR) in the innate immune system to be described (37). It acts as a coreceptor (along with Toll-like receptor TLR4 and MD-2) for the binding of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the presence of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP) and other pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) to activate several downstream signaling pathways (1). E. chaffeensis infection causes downregulation of the expression of several pattern recognition receptors, such as CD14 and TLR4, and inhibits lipopolysaccharide activation of NF-κB, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (ERK1/2), and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) in host monocytes (20). Similarly, an early decrease in the expression of CD14 was observed in granulocytes infected by A. phagocytophilum (41). Thus, E. chaffeensis not only lacks major PAMPs, such as LPS, in order to avoid the activation of host cells, but also can actively block host cell activation. However, the ehrlichial effector protein involved in this process has not been found. TRP32 may play a key role through its interaction with CD14.

Among other TRP32-interacting proteins identified by Y2H, the identification of PSMB1 and RC3H1 was of significant interest. They were not the most frequently identified TRP32-interacting proteins, but they exhibited strong interactions in co-IP. PSMB1 is one of the beta subunits of the proteasome, which is a multicatalytic proteinase complex and is the major system responsible for degradation of intracellular proteins in a ubiquitin-dependent process in a nonlysosomal pathway (16, 35). By controlling the levels of key proteins, the proteosome regulates almost all of the cellular activities, including signal transduction, stress response, DNA replication and repair, transcription, cell cycle progression, immune response, and apoptosis (21). During the process of targeted protein degradation, ubiquitin is added to a target protein through the sequential action of at least three enzymes: an E1 activating enzyme, an E2 conjugating enzyme, and an E3 ligase (19). RC3H1, also known as roquin, is a highly conserved member of the RING type E3 ligase family. The RC3H1 protein is distinguished by the presence of a CCCH zinc finger found in RNA-binding proteins and by localization to cytosolic RNA granules implicated in regulating mRNA processing, stability, and translation (38). Such a function represents a unique method of E3 ligase-mediated control of protein expression that relies on posttranscriptional modification. RC3H1 deficiency results in upregulated mRNA expression of chemokine (C-XC motif) receptor 5 (CXCR5), CD100 chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5), programmed cell death 1 (PDCD1), and interleukin-21 (IL-21) (19). A previous study suggested that degradation of some host proteins by proteasomes is required for the inhibition of the apoptotic process in A. phagocytophilum-infected neutrophils (43). Thus, the interactions of PSMB1 and RC3H1 with TRP32 play important roles in ehrlichial manipulation of host and pathogen protein fates. Moreover, we previously reported that both TRP47 and TRP120 of E. chaffeensis strongly interact with polycomb group ring finger 5 (PCGF5) protein, a member of the polycomb group (PcG) proteins with a specialized ring finger motif characterized by a cysteine-rich Zn2+-binding domain, suggesting that host proteins with ring finger domains are important targets of ehrlichial effector proteins.

In addition to EF1A1, our data also identified some common or closely related interacting partners of E. chaffeensis TRP32, TRP47, and TRP120, including immunoglobulin loci IGHA1, IGHV, and immunoglobulin lambda-like polypeptide 5 (IGLL5) (Table 1). We previously identified immunoglobulin light chain lambda (IGL), immunoglobulin kappa constant (IGKC), and IGHA1 as interacting with TRP120 and IGLL1 as interacting with TRP47 (23, 40). Thus, it is more evident that TRPs interact directly with a wide variety of regions of human immunoglobulins. Although the role and significance of immunoglobulins and their interactions with ehrlichial TRPs in the macrophage are undetermined and require further study, the association of TRPs with the host immune system, as well as protein synthesis, suggests convergence on defined cellular networks by Ehrlichia effectors and an increased importance of overlapping or function-associated targets.

Other TRP32-interacting partners identified by Y2H but not confirmed include some host proteins involved in degradation and trafficking of intracellular proteins, glycometabolism, and lipid metabolism (Table 1). Since current and previous Y2H experience indicated that the majority of interacting protein candidates examined were involved in genuine interactions, we anticipate that many of the unconfirmed host targets identified in this study do interact with TRP32. Therefore, we anticipate that additional TRP32 functions associated with major host cell processes may be further defined from this group of Y2H targets.

Experiments using RNA interference indicated that the reduction of host target proteins of TRP32 inhibited E. chaffeensis infection; moreover, the inhibition could occur at different stages of infection for different targets. The reduction of CD63 appeared to inhibit Ehrlichia infection from the early to the late stage, perhaps because the interaction of TRP32 and CD63 could help ehrlichial internalization and prevent early endosomal maturation. The reduction of DAZAP2 also inhibited Ehrlichia infection from the early stage but lost inhibition at the late stage, and the reduction of EF1A1 and FTL inhibited infection only at the middle stage, suggesting that host proteins identified as TRP32 targets play different roles in E. chaffeensis infection. The reduction of a single target protein could not abolish the ehrlichial growth completely; therefore, further study is needed to understand the importance of each specific TRP32-host protein interaction in ehrlichial pathobiology.

Neither the full-length TRP32 nor any of three regions (17-amino-acid N terminus, 120-amino-acid TRs, or 61-amino-acid C terminus) had substantial homology with any known proteins or conserved domains (26). However, we previously identified a major immunoreactive 19-kDa protein (TRP19) in E. canis as the ortholog of E. chaffeensis TRP32, based on genomic and protein analysis (28). A remarkable feature of TRP32 and TRP19 is the homologous carboxy-terminal domain dominated by tyrosine and cysteine (CY-rich domain), suggesting that it is a functionally important conserved domain. The findings of the current study confirm the importance of TRP32C in molecular host-pathogen interactions. Moreover, our previous studies indicated the importance of all regions of TRP120 and TRP47 in the interactions with targets (23, 40); hence, TRP32N and TRP32TR could contribute to the interactions with the host as well as TRP32C, although they are not available for Y2H due to the autoactivation of reporter genes in yeast. It is likely that additional TRP32-interacting proteins exist but were not identified since the full-length TRP32 could not be used in this Y2H assay.

TRP32 is a secreted protein which can be detected extracellularly in the host cell and culture supernatants (26). TRP32 was predicted by the SecretomeP (version 2.0) server (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SecretomeP) to be secreted by a nonclassical and leaderless mechanism and recently was reported to be a T1SS substrate (39). Immunofluorescent microscopy demonstrated that interactions between TRP32 and host targets occurred either on ehrlichial morula or in the host cell cytoplasm adjacent to morula, which was consistent with our previous reports regarding interactions between TRP47/TRP120 and host targets (23, 40). The interactions between TRPs and host targets cause the redistribution of some host proteins to ehrlichial morulae or cytoplasm adjacent to the morulae in E. chaffeensis-infected cells, further indicating the profound effects of TRPs on host cell protein recruitment. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms underlying TRP-host molecular interactions and their importance in ehrlichial pathobiology and to identify other ehrlichial effector proteins and host cell targets in order to elucidate and define the molecular mechanisms that underlie Ehrlichia pathobiology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grants AI071145 and AI069270, and by funding from the Clayton Foundation for Research.

We thank David H. Walker for reviewing the manuscript and providing helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 30 April 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Arroyo-Espliguero R, Avanzas P, Jeffery S, Kaski JC. 2004. CD14 and Toll-like receptor 4: a link between infection and acute coronary events? Heart 90:983–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barnewall RE, Rikihisa Y. 1994. Abrogation of gamma interferon-induced inhibition of Ehrlichia chaffeensis infection in human monocytes with iron-transferrin. Infect. Immun. 62:4804–4810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barnewall RE, Rikihisa Y, Lee EH. 1997. Ehrlichia chaffeensis inclusions are early endosomes which selectively accumulate transferrin receptor. Infect. Immun. 65:1455–1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berditchevski F. 2001. Complexes of tetraspanins with integrins: more than meets the eye. J. Cell Sci. 114:4143–4151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Botos E, et al. 2008. Caveolin-1 is transported to multi-vesicular bodies after albumin-induced endocytosis of caveolae in HepG2 cells. J. Cell Mol. Med. 12:1632–1639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carlyon JA, Ryan D, Archer K, Fikrig E. 2005. Effects of Anaplasma phagocytophilum on host cell ferritin mRNA and protein levels. Infect. Immun. 73:7629–7636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen SM, Cullman LC, Walker DH. 1997. Western immunoblotting analysis of the antibody responses of patients with human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis to different strains of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia canis. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 4:731–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a. Clontech 2008. Yeast protocols handbook. Protocol Pt3024-1, version PR742227. Clontech Laboratories Inc., Palo Alto, CA [Google Scholar]

- 8. Condeelis J. 1995. Elongation factor 1 alpha, translation and the cytoskeleton. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20:169–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Doyle CK, et al. 2005. Detection of medically important Ehrlichia by quantitative multicolor TaqMan real-time polymerase chain reaction of the dsb gene. J. Mol. Diagn. 7:504–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Doyle CK, Nethery KA, Popov VL, McBride JW. 2006. Differentially expressed and secreted major immunoreactive protein orthologs of Ehrlichia canis and E. chaffeensis elicit early antibody responses to epitopes on glycosylated tandem repeats. Infect. Immun. 74:711–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doyle CK, Zhang X, Popov VL, McBride JW. 2005. An immunoreactive 38-kilodalton protein of Ehrlichia canis shares structural homology and iron-binding capacity with the ferric ion-binding protein family. Infect. Immun. 73:62–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dunning Hotopp JC, et al. 2006. Comparative genomics of emerging human ehrlichiosis agents. PLoS Genet. 2:e21 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0020021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ejiri S. 2002. Moonlighting functions of polypeptide elongation factor 1: from actin bundling to zinc finger protein R1-associated nuclear localization. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 66:1–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hamilton MH, Tcherepanova I, Huibregtse JM, McDonnell DP. 2001. Nuclear import/export of hRPF1/Nedd4 regulates the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of its nuclear substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 276:26324–26331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim JE, et al. 2008. Proline-rich transcript in brain protein induces stress granule formation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28:803–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kruger E, Kloetzel PM, Enenkel C. 2001. 20S proteasome biogenesis. Biochimie 83:289–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuriakose JA, Zhang X, Luo T, McBride JW. 29 May 2012. Molecular basis of antibody mediated immunity against Ehrlichia chaffeensis involves species-specific linear epitopes in tandem repeat proteins. Microbes Infect. 10.1016/j.micinf.2012.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. Latysheva N, et al. 2006. Syntenin-1 is a new component of tetraspanin-enriched microdomains: mechanisms and consequences of the interaction of syntenin-1 with CD63. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:7707–7718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lin AE, Mak TW. 2007. The role of E3 ligases in autoimmunity and the regulation of autoreactive T cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 19:665–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin M, Rikihisa Y. 2004. Ehrlichia chaffeensis downregulates surface Toll-like receptors 2/4, CD14 and transcription factors PU. 1 and inhibits lipopolysaccharide activation of NF-kappa B, ERK 1/2 and p38 MAPK in host monocytes. Cell Microbiol. 6:175–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu CH, Goldberg AL, Qiu XB. 2007. New insights into the role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in the regulation of apoptosis. Chang Gung Med. J. 30:469–479 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lukas J, et al. 2009. Dazap2 modulates transcription driven by the Wnt effector TCF-4. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:3007–3020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luo T, Kuriakose JA, Zhu B, Wakeel A, McBride JW. 2011. Ehrlichia chaffeensis TRP120 interacts with a diverse array of eukaryotic proteins involved in transcription, signaling, and cytoskeleton organization. Infect. Immun. 79:4382–4391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Luo T, Zhang X, McBride JW. 2009. Major species-specific antibody epitopes of the Ehrlichia chaffeensis p120 and E. canis p140 orthologs in surface-exposed tandem repeat regions. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:982–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Luo T, Zhang X, Nicholson WL, Zhu B, McBride JW. 2010. Molecular characterization of antibody epitopes of Ehrlichia chaffeensis ankyrin protein 200 and tandem repeat protein 47 and evaluation of synthetic immunodeterminants for serodiagnosis of human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 17:87–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luo T, Zhang X, Wakeel A, Popov VL, McBride JW. 2008. A variable-length PCR target protein of Ehrlichia chaffeensis contains major species-specific antibody epitopes in acidic serine-rich tandem repeats. Infect. Immun. 76:1572–1580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McBride JW, et al. 2003. Kinetics of antibody response to Ehrlichia canis immunoreactive proteins. Infect. Immun. 71:2516–2524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McBride JW, et al. 2007. Identification of a glycosylated Ehrlichia canis 19-kilodalton major immunoreactive protein with a species-specific serine-rich glycopeptide epitope. Infect. Immun. 75:74–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McBride JW, Walker DH. 2011. Molecular and cellular pathobiology of Ehrlichia infection: targets for new therapeutics and immunomodulation strategies. Expert. Rev. Mol. Med. 13:e3 doi:10.1017/S1462399410001730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McBride JW, Zhang X, Wakeel A, Kuriakose JA. 2011. Tyrosine-phosphorylated Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia canis tandem repeat orthologs contain a major continuous cross-reactive antibody epitope in lysine-rich repeats. Infect. Immun. 79:3178–3187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Paddock CD, Childs JE. 2003. Ehrlichia chaffeensis: a prototypical emerging pathogen. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 16:37–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pols MS, Klumperman J. 2009. Trafficking and function of the tetraspanin CD63. Exp. Cell Res. 315:1584–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Popov VL, Yu X, Walker DH. 2000. The 120 kDa outer membrane protein of Ehrlichia chaffeensis: preferential expression on dense-core cells and gene expression in Escherichia coli associated with attachment and entry. Microb. Pathog. 28:71–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rikihisa Y. 2010. Molecular events involved in cellular invasion by Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Vet. Parasitol. 167:155–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shang F, Taylor A. 2011. Ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and cellular responses to oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 51:5–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tsui S, et al. 2000. Identification of two novel proteins that interact with germ-cell-specific RNA-binding proteins DAZ and DAZL1. Genomics 65:266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vidal K, Donnet-Hughes A. 2008. CD14: a soluble pattern recognition receptor in milk. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 606:195–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vinuesa CG, et al. 2005. A RING-type ubiquitin ligase family member required to repress follicular helper T cells and autoimmunity. Nature 435:452–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wakeel A, den Dulk-Ras A, Hooykaas PJJ, McBride JW. 30 December 2011. Ehrlichia chaffeensis tandem repeat proteins and Ank200 are type 1 secretion system substrates related to the repeats-in-toxin exoprotein family. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 1:22 doi:10.3389/fcimb.2011.00022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wakeel A, Kuriakose JA, McBride JW. 2009. An Ehrlichia chaffeensis tandem repeat protein interacts with multiple host targets involved in cell signaling, transcriptional regulation, and vesicle trafficking. Infect. Immun. 77:1734–1745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Whist SK, Storset AK, Johansen GM, Larsen HJ. 2003. Modulation of leukocyte populations and immune responses in sheep experimentally infected with Anaplasma (formerly Ehrlichia) phagocytophilum. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 94:163–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Winkel A, et al. 2008. Wnt-ligand-dependent interaction of TAK1 (TGF-beta-activated kinase-1) with the receptor tyrosine kinase Ror2 modulates canonical Wnt-signalling. Cell. Signal. 20:2134–2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yoshiie K, Kim HY, Mott J, Rikihisa Y. 2000. Intracellular infection by the human granulocytic ehrlichiosis agent inhibits human neutrophil apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 68:1125–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang JZ, Sinha M, Luxon BA, Yu XJ. 2004. Survival strategy of obligately intracellular Ehrlichia chaffeensis: novel modulation of immune response and host cell cycles. Infect. Immun. 72:498–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhu B, et al. 2011. Ehrlichia chaffeensis TRP120 binds a G+C-rich motif in host cell DNA and exhibits eukaryotic transcriptional activator function. Infect. Immun. 79:4370–4381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhu B, et al. 2009. Nuclear translocated Ehrlichia chaffeensis ankyrin protein interacts with a specific adenine-rich motif of host promoter and intronic Alu elements. Infect. Immun. 77:4243–4255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]