Abstract

Streptococcus pyogenes Rgg is a transcriptional regulator that interacts with the cofactor LacD.1 to control growth phase-dependent expression of genes, including speB, which encodes a secreted cysteine protease. LacD.1 is thought to interact with Rgg when glycolytic intermediates are abundant in a manner that prevents Rgg-mediated activation of speB expression via binding to the promoter region. When the intermediates diminish, LacD.1 dissociates from Rgg and binds to the speB promoter to activate expression. The purpose of this study was to determine if Rgg bound to chromatin during the exponential phase of growth and, if so, to identify the binding sites. Rgg bound to 62 chromosomal sites, as determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with DNA microarrays. Thirty-eight were within noncoding DNA, including sites upstream of the genes encoding the M protein (M49), serum opacity factor (SOF), fibronectin-binding protein (SfbX49), and a prophage-encoded superantigen, SpeH. Each of these sites contained a promoter that was regulated by Rgg, as determined with transcriptional fusion assays. Purified Rgg also bound to the promoter regions of emm49, sof, and sfbX49 in vitro. Results obtained with a lacD.1 mutant showed that both LacD.1 and Rgg were necessary for the repression of emm49, sof, sfbX49, and speH expression. Overall, the results indicated that the DNA binding specificity of Rgg is responsive to environmental changes in a LacD.1-dependent manner and that Rgg and LacD.1 directly control virulence gene expression in the exponential phase of growth.

INTRODUCTION

Streptococcus pyogenes is the causative agent of human diseases ranging in severity from impetigo and pharyngitis to life-threatening infections such as necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (23, 24). Pathogenesis involves a variety of virulence factors, many of which are localized to the bacterial cell wall or secreted into the extracellular environment (23, 24). The expression of these virulence factors during the infectious process is dynamic, which is important in sustaining colonization and contributes to the wide variety of clinical manifestations associated with infection (23, 24, 29, 34, 41).

A convenient approach to study the control of gene expression in response to changing environmental conditions is to assess expression during different stages of growth with batch cultures (13, 14, 25, 26, 32, 33). The exponential phase of growth is thought to approximate, albeit imperfectly, the initial stages of bacterial colonization when catabolic substrates are likely to be readily available, catabolic end product accumulation is low, and the population density of the pathogen is low (34). Consistent with this interpretation, the exponential phase is associated with the expression of several established virulence factors involved in adherence and avoidance of innate immunity. These include the M protein, which binds to the CD46 receptor on mammalian cells and inhibits phagocytosis (56), a streptococcal fibronectin-binding protein (SfbX49), which mediates adherence by binding to fibronectin (30), and serum opacity factor (SOF), which both opacifies human serum (22) and binds to fibronectin to promote adherence (28, 47). In contrast, the post-exponential phase is thought to be more representative of later, potentially invasive stages of infection, which are characterized by the diminished availability of catabolic substrates, an accumulation of metabolic end products, and high bacterial density. This phase of growth is associated with the expression of hydrolytic enzymes (29, 34), including streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B (SpeB), which is a secreted cysteine protease that degrades or cleaves a variety of bacterial and host proteins (11). Although obviously a gross oversimplification, the study of growth phase-associated changes in gene expression has proven useful in developing a better understanding of the conditions under which virulence factors are expressed, in making predictions about their functions, and in identifying how transcriptional regulatory proteins respond to environmental changes (4, 13, 14, 25, 26, 32, 33).

The S. pyogenes genome encodes more than 60 transcriptional regulatory proteins, which together control genome-wide patterns of expression. Typically, the proteins bind to DNA in operator regions to influence transcription (8). Rgg (also known as RopB) is a transcriptional regulator which is encoded by some species of low-G+C Gram-positive bacteria, including S. pyogenes (15, 37, 45, 50, 53, 58). Rgg proteins have a helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif in the amino terminus and various carboxyl-terminal domains, including a tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR), which is likely to mediate binding to peptide pheromone (27). The regulators often control the expression of adjacent genes (45, 51, 53). For example, in S. pyogenes, Rgg activates expression of the adjacent speB gene and represses its own expression and that of the other adjacent gene, spd, which encodes a secreted nuclease known as streptodornase (Spd), or mitogenic factor-1. Secreted nucleases are important in facilitating escape of the pathogen from neutrophil extracellular entrapment (9).

Rgg of S. pyogenes is an important regulator of growth phase-associated changes in gene expression (13, 14). In strain NZ131, rgg is expressed in both the exponential and post-exponential phases of growth, although expression is higher in the latter (18). Despite being expressed in both, the targets of Rgg regulation vary considerably between the phases of growth (14, 26). Loughman and Caparon showed that during the exponential phase of growth, an Rgg coregulator, LacD.1, senses the glycolytic intermediates glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone, resulting in a LacD.1 conformation that favors binding to Rgg (36). When bound to LacD.1, Rgg is unable to bind to the speB promoter to activate transcription (36). In contrast, during the post-exponential phase of growth, the levels of glycolytic intermediates decrease, resulting in a change in the conformation of LacD.1 and dissociation from Rgg. Rgg can then bind to the promoter region of speB to activate transcription (36). We previously showed that Rgg binds to the speB promoter only during the post-exponential phase of growth, consistent with the model described by Loughman and Caparon (2, 36).

The function of a regulon is often investigated by comparing patterns of expression between strains with and without a functional regulator (obtained by directed mutagenesis), based on the premise that commonly regulated genes are likely to have related functions. Inactivation of rgg in strain NZ131 (a serotype M49 strain isolated from a patient with poststreptococcal acute glomerulonephritis) alters the expression of 293 and 588 genes in the exponential and post-exponential phases of growth, respectively (26), hindering functional predictions. To address this issue, we recently identified the DNA binding profile of Rgg during the post-exponential phase of growth by using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) coupled to DNA microarrays (ChIP-chip) as an initial step to identify genes that are directly regulated by Rgg (2). Rgg bound to 35 noncoding DNA regions, 70% of which were adjacent to genes previously reported to be regulated by Rgg. The results showed that Rgg directly regulates the expression of several secreted virulence genes and, surprisingly, directly controls the expression of genes encoded within temperate bacteriophages.

The aim of the current study was to determine if Rgg bound to chromatin in the exponential phase of growth and, if so, to identify the binding sites and determine if they differ from those in the post-exponential phase of growth. The results showed that Rgg binds to distinctly different sites during the exponential phase of growth than during the post-exponential phase. Moreover, the results support the idea that Rgg directly regulates important virulence-associated genes during both phases of growth in a LacD.1-dependent manner.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. S. pyogenes was grown at 37°C in Todd-Hewitt broth (Becton, Dickinson, Spark, MD) containing 0.2% (wt/vol) yeast extract (THY). Escherichia coli strain DH5α was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: carbenicillin at 100 μg/ml for E. coli, spectinomycin at 100 μg/ml for E. coli and S. pyogenes, erythromycin at 2.5 μg/ml for S. pyogenes, and kanamycin at 50 μg/ml for E. coli and 500 μg/ml for S. pyogenes.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | hsdR17 recA1 gyrA endA1 relA1 | Invitrogen |

| Rosetta 2(DE3) | F− ompT hsdSB(rB− mB−) gal dcm (DE3) pRARE2 (Chlr) | Novagen |

| S. pyogenes | ||

| NZ131 | M49 serotype | D. R. Martin, New Zealand |

| rgg mutant | NZ131 rgg mutant, Eryr | 15 |

| SA5 | NZ131 rgg mutant complemented with pSA3, Eryr Kanr | 2 |

| wt::luc | NZ131 transformed with pKSM720, Sptr | 2 |

| wt::Pemm49-luc | NZ131 transformed with pSA21, Sptr | This study |

| wt::Psof-luc | NZ131 transformed with pSA22, Sptr | This study |

| wt::PsfbX49luc | NZ131 transformed with pSA23, Sptr | This study |

| wt::PspeH-luc | NZ131 transformed with pSA24, Sptr | This study |

| rgg::luc | NZ131 rgg mutant transformed with pKSM720, Eryr Sptr | 2 |

| rgg::Pemm49-luc | NZ131 rgg mutant transformed with pSA21, Eryr Sptr | This study |

| rgg::Psof-luc | NZ131 rgg mutant transformed with pSA22, Eryr Sptr | This study |

| rgg::PsfbX49-luc | NZ131 rgg mutant transformed with pSA23, Eryr Sptr | This study |

| rgg::PspeH-luc | NZ131 rgg mutant transformed with pSA24, Eryr Sptr | This study |

| lacD.1 mutant | NZ131 lacD.1 mutant, Eryr | This study |

| SA6 | NZ131 lacD1 mutant complemented with pSA26, Eryr Kanr | This study |

| lacD.1::PspeH-luc | NZ131 lacD.1 mutant transformed with pSA24, Eryr Sptr | This study |

| SA6::PspeH-luc | NZ131 lacD.1 complemented strain (SA6) transformed with pSA24, Eryr Kanr Sptr | This study |

| lacD.1::Pemm49-luc | NZ131 lacD.1 mutant transformed with pSA21, Eryr Sptr | This study |

| SA6::Pemm49-luc | NZ131 lacD.1 complemented strain (SA6) transformed with pSA21, Eryr Kanr Sptr | This study |

| lacD.1::Psof-luc | NZ131 lacD.1 mutant transformed with pSA22, Eryr Sptr | This study |

| SA6::Psof-luc | NZ131 lacD.1 complemented strain (SA6) transformed with pSA22, Eryr Kanr Sptr | This study |

| lacD.1::PsfbX49-luc | NZ131 lacD.1 mutant transformed with pSA23, Eryr Sptr | This study |

| SA6::PsfbX49-luc | NZ131 lacD.1 complemented strain (SA6) transformed with pSA23, Eryr Kanr Sptr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pVA891-2 | Suicide cloning vector, Eryr | 40 |

| pVaLac | Shuttle vector defective for replication in S. pyogenes; Eryr | This study |

| pSA17 | Promoter region of emm49 cloned into pGEM-T vector, Ampr | This study |

| pSA18 | Promoter region of sof cloned into pGEM-T vector, Ampr | This study |

| pSA19 | Promoter region of sfbX49 cloned into pGEM-T vector, Ampr | This study |

| pSA20 | Promoter region of speH cloned into pGEM-T vector, Ampr | This study |

| pKSM720 | GAS replicating plasmid with firefly luciferase and RBS, Sptr | 33 |

| pSA21 | Noncoding region upstream of emm49 cloned into pKSM720, Sptr | This study |

| pSA22 | Noncoding region upstream of sof cloned into pKSM720, Sptr | This study |

| pSA23 | Noncoding region upstream of sfbX49 cloned into pKSM720, Sptr | This study |

| pSA24 | Noncoding region upstream of speH cloned into pKSM720, Sptr | This study |

| pMNN23 | Streptococcal expression plasmid containing rofA promoter, Kanr | 45 |

| pSA26 | lacD.1 open reading frame cloned into pMNN23 | This study |

Chlr, chloramphenicol resistant; Eryr, erythromycin resistant; Kanr, kanamycin resistant; Sptr, spectinomycin resistant; Ampr, ampicillin resistant; GAS, group A streptococcus; RBS, ribosome-binding site.

DNA cloning.

Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli by alkaline lysis using either the QIAprep Spin miniprep kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) or Maxi/Midi prep purification systems (Qiagen). DNA fragments were isolated from agarose gels using the SpinPrep gel DNA kit (Novagen, Madison, WI). PCR was done with GoTaq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI). DNA sequencing was done at Iowa State University (Ames, IA).

Construction of a lacD.1 mutant and complementation.

A 355-bp DNA region containing part of the lacD.1 open reading frame (ORF) was amplified by PCR using genomic DNA (gDNA) isolated from strain NZ131 (Table 1) as the template DNA with the primers LacFor and LacRev (Table 2). The DNA was digested with BclI and HindIII and ligated with similarly digested pVA891-2. A portion of the ligation mixture was used to transform E. coli, and the composition of the resulting plasmid, designated pVALac, was confirmed by PCR and DNA sequence analysis (data not shown). The chromosomal lacD.1 gene was inactivated by transforming NZ131 with pVALac. Insertional inactivation of lacD.1 was confirmed by using PCR.

Table 2.

Primers used in the study

| Primer | Sequencea (5′–3′) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| emm49fwd | AGTGATCGCATCTGCAGGCGT | This study |

| emm49rev | ACAGCCACAGCGACCGCTAC | This study |

| soffwd | CAGACGGCGCCAGAGGGTTGAG | This study |

| sofrev | TTCCGACGGAGACGAGCCCT | This study |

| speHfwd | AAATGATATCCGTCGGGAACCAGATAAAGC | This study |

| speHrev | GACAAACATATAATCATGCTGTAGATTTTC | This study |

| groEL2fwd | GCTACTCGACGTAACATTGTG | 2 |

| groEL2rev | GGAGCCTTCGTACCCAGCAT | 2 |

| emm49_BamHIfwd | GCGGATCCAGTGATCGCATCTGCAGGCGT | This study |

| emm49_XhoIrev | GCCTCGAGACAGCCACAGCGACCGCTAC | This study |

| sof_BamHIfwd | GCGGATCCCAGACGGCGCCAGAGGGTTG | This study |

| sof_XhoIrev | GCCTCGAGTTCCGACGGAGACGAGCCCT | This study |

| sfbx_BamHIfwd | GCGGATCCCTGGAGACAAACGTGAAGCATCC | This study |

| sfbx_XhoIrev | GCCTCGAGCGTCTAGTTCTTCTTTGACACG | This study |

| speH_BamHIfwd | GCGGATCCAAATGATATCCGTCGGGAACC | This study |

| speH_XhoIrev | GCCTCGAGGACAAACATATAATCATGC | This study |

| LacFor | CCACATGAGTACTATTGCTAAGCCGTT | This study |

| LacRev | ATGAGAGCTGCTTGATAGGATAAGGTTG | This study |

| LacD1_BglIIfwd | CTATGGAGATCTATGACAATCACAGCAAATAAAAG | This study |

| LacD1_PstIrev | GCTGCCTGCAGTTAGATTTTTTCCGTCCAAGGGC | This study |

Underlined nucleotides are restriction sites incorporated into the primer.

To complement the lacD.1 mutant strain, a 978-bp DNA region containing the lacD.1 open reading frame (ORF) was amplified by PCR using NZ131 gDNA (Table 1) as the template DNA and the primers LacD1BglIIfwd and LacD1_PstIrev (Table 2). The DNA was digested with BglII and PstII and ligated with similarly digested pMNN23 (Table 1). The resultant plasmid was designated pSA26, and its composition was verified by PCR and DNA sequence analysis (data not shown). pSA26 was used to transform NZ131, which was confirmed by PCR.

ChIP-chip.

A ChIP assay was used to identify the DNA binding sites of Rgg in the exponential phase of growth using a previously described experimental protocol (2). Briefly, overnight cultures of S. pyogenes strains rgg (15) and SA5 (encoding the Rgg-Myc fusion protein) (2) were inoculated into 40 ml of THY broth in 50-ml tubes to an A600 of 0.08. The cultures were grown to an A600 of approximately 0.35, which corresponds to the mid-exponential phase of growth. The culture was then treated with 1% formaldehyde (wt/vol), and the cross-linked chromatin was fragmented with sonication. DNA cross-linked to the Rgg-Myc fusion protein expressed by strain SA5 was immunoprecipitated with a monoclonal antibody to Myc (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reference (control) samples were similarly prepared from an NZ131 rgg mutant strain. Immunoprecipitated DNA was purified, labeled, and hybridized to custom-designed GeneChips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) representing the entire NZ131 genome according to the manufacturer's instructions. GeneChips were scanned using a GeneChip 3000 7G scanner (Affymetrix) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The data from three experiments were normalized and analyzed using the Probe Logarithmic Intensity Error Estimation (PLIER) algorithm in ArrayStar (DNAStar Inc., Madison, WI). The regions that showed enrichment of at least 2-fold in strain SA5 compared to the control in all three biological replicates were considered potential areas of the chromosome directly bound by Rgg.

Rgg binding motif assessment.

Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) version 4.3 was used to search for motifs in the coding and noncoding regions bound by Rgg in vivo. Searches were conducted with either the coding or the noncoding regions, or both, as the input sequence. The program was allowed to identify 6- to 50-bp motifs that occurred between 1 and 10 times per fragment on either strand of DNA. As a control, a similar number of coding and noncoding regions not predicted to be bound by Rgg was selected and a similar search was conducted using MEME. In addition, a similar strategy was used with Gapped Local Alignment of Motifs (GLAM2) version 4.6.

Transcription reporter assays.

To construct transcriptional fusions, pKSM720 (1), which encodes firefly luciferase, was used. The putative promoter regions of emm49, sof, sfbX49, and speH (designated Pemm49, Psof, PsfbX49, and PspeH, respectively), were amplified using NZ131 gDNA as the template DNA and one of the following primer pairs: emm49_BamHIfwd and emm49_XhoIrev, sof_BamHIfwd and sof_XhoIrev, sfbx_BamHIfwd and sfbx_XhoIrev, or speH_BamHIfwd and speH_XhoIrev (Table 2). The DNA fragments were gel purified, digested with BamHI and XhoI, and cloned into BglII and XhoI of pKSM720 (Table 1). The Pemm49, Psof, PsfbX49, and PspeH DNA fragments were cloned using BglII and XhoI sites of pKSM720 to create pSA21, pSA22, pSA23, and pSA24, respectively (Table 1). NZ131 was transformed with pKSM720, pSA21, pSA22, pSA23, and pSA24 by electroporation to create wt::luc, wt::Pemm49-luc, wt::Psof-luc, wt::PsfbX49-luc, and wt::PspeH-luc, respectively (Table 1). Similarly, the NZ131 strain lacking rgg was transformed with pKSM720, pSA21, pSA22, pSA23, and pSA24 to create rgg::luc, rgg::Pemm49-luc, rgg::Psof-luc, rgg::PsfbX49-luc, and rgg::PspeH-luc, respectively (Table 1). The strain lacking lacD.1 was transformed with pSA21, pSA22, pSA23, and pSA24 by electroporation to create lacD.1::Pemm49-luc, lacD.1::Psof-luc, lacD.1::PsfbX49-luc, and lacD.1::PspeH-luc, respectively (Table 1). Similarly, SA6 (a lacD.1 complemented strain) was transformed with pSA21, pSA22, pSA23, and pSA24 to create SA6::Pemm49-luc, SA6::Psof-luc, SA6::PsfbX49-luc, and SA6::PspeH-luc, respectively (Table 1). PCR was used to confirm the presence of the noncoding DNA and the luc gene in all the transformants. The S. pyogenes strains containing the transcriptional fusion plasmids were grown to the exponential (A600 of ∼0.35) phase of growth in THY broth, and luciferase activity was measured according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). Assays were done both with and without spectinomycin, and when not included, the maintenance of the plasmid was confirmed for each experiment by plating an aliquot of the culture on THY agar plates with or without spectinomycin and incubating the plates overnight.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA).

An Rgg-maltose-binding protein (MBP) fusion protein was expressed and purified as previously described (2). The putative promoter regions upstream of emm49, sof, sfbX49, and speH were amplified using NZ131 gDNA as the template DNA and the primer sets emm49fwd and emm49rev, soffwd and sofrev, sfbx_BamHIfwd and sfbx_XhoIrev, and speHfwd and speHrev, respectively (Table 2). The fragments, designated Pemm49, Psof, PsfbX49, and PspeH, were separated by gel electrophoresis, purified, and cloned into pGEM-T (Promega, Madison, WI) to create pSA17, pSA18, pSA19, and pSA20 (Table 1), respectively. A similarly sized fragment corresponding to an internal region of the groEL ORF was similarly prepared using groEL2fwd and groEL2rev (Table 2) and used as a nonspecific DNA control. The putative promoter fragments were then excised by digestion, gel purified, dephosphorylated, and end labeled with [γ32P] ATP using polynucleotide kinase. Various amounts of MBP-Rgg were incubated in 25 μl of binding buffer (25 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 0.1 mM EDTA, 75 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, and 0.5 μg/ml calf thymus DNA) at room temperature for 20 min. Competition experiments were conducted by including the cognate cold unradiolabeled probe prior to the addition of the protein. The reaction mixtures were separated on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel. The gels were dried, exposed to an Amersham Biosciences storage phosphor screen, and imaged with a Typhoon 9400 instrument (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

RESULTS

Identification of Rgg binding sites in vivo.

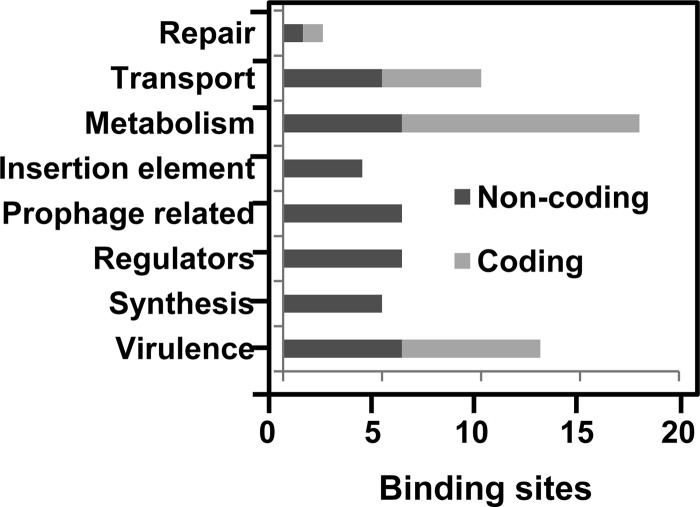

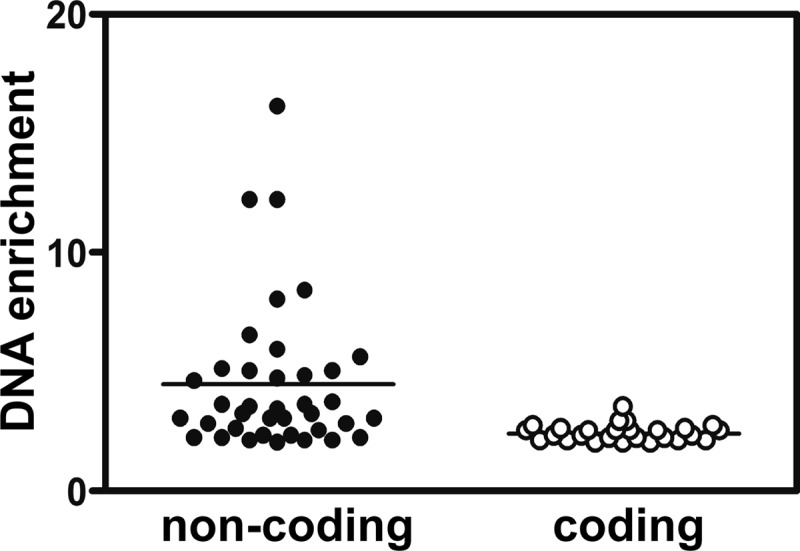

ChIP was used to enrich DNA bound by Rgg. To do so, an S. pyogenes strain expressing an Rgg-Myc fusion protein, referred to as SA5 (2), was grown to the mid-exponential phase and Rgg-bound DNA was immunoprecipitated with an antibody specific to the Myc epitope. An rgg mutant strain was used as a control for nonspecific precipitation of DNA. Immunoprecipitated DNA was purified, labeled, and hybridized to custom-designed Affymetrix GeneChips representing the entire NZ131 chromosome. Three independent experiments were conducted using both strains. Rgg bound to 62 regions in the chromosome (Table 3; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material), including 24 sites within coding DNA and 38 within noncoding DNA (Table 3; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). Only 14.7% of the chromosome is noncoding, and thus, binding was biased to noncoding DNA. In addition, the level of enrichment of noncoding DNA was significantly greater than that of coding DNA (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1). A total of 70% of the sites within noncoding DNA were adjacent to genes previously shown to be regulated by Rgg (Table 3) and encoding functions related to virulence, stress responses, and metabolism (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Noncoding DNA bound by Rgg in the exponential phase of growth

| Category and Spy49 no.a | Geneb | Description | ChIP-chip fold enrichmentc | Transcript fold change (rgg mutant/WT)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virulence associated | ||||

| 1671 | emm49 | Antiphagocytic M protein | 8.4 | 2 |

| 1334-1335 | – | Esterase | 3.0 | – |

| 1683 | sfbX49 | Fibronectin-binding protein | 2.1 | 5 |

| 1684 | sof | Serum opacity factor | 2.1 | 7 |

| 830 | sclB | Streptococcal collagen-like surface protein | 2.2 | 3 |

| 1651 | – | Fibronectin-binding protein | 2.0 | −3 |

| Synthesis | ||||

| 1557c | asp | Alkaline shock protein | 3.6 | 2 |

| 1183c | – | Peroxide resistance protein | 3.6 | – |

| 1428c | rpsF | 30S ribosomal protein S6 | 3.5 | −2 |

| 127 | – | Translation initiation inhibitor | 3.4 | – |

| 1163c | – | Cytoplasmic protein | 5.0 | 3 |

| Transcriptional regulators | ||||

| 1113c | – | Transcription factor | 5.6 | −2 |

| 862-863 | – | Two-component sensor histidine kinase | 3.2 | – |

| 1334-1335 | copY | Negative transcriptional regulator | 3.0 | – |

| 1533 | – | MerR family transcriptional regulator | 2.5 | – |

| 725-726 | – | LysR family transcriptional regulator | 2.2 | −3 |

| 1142 | – | Biotin repressor family transcriptional regulator | 2.1 | – |

| 380-381 | mtsR | Metal-dependent transcriptional regulator | 12.2 | 2 |

| 380-381 | mtsA | Metal ABC transporter substrate-binding lipoprotein precursor | 12.2 | – |

| Prophage related | ||||

| 790 | – | Cell wall hydrolase | 5.1 | ND |

| 1518 | – | Cro protein | 3.0 | ND |

| 1529 | – | Phage transcriptional repressor protein | 2.2 | ND |

| 792 | speH | Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin H | 2.3 | ND |

| Insertion element related | ||||

| 677c | – | Transposase | 6.5 | ND |

| 1032 | – | Transposase | 4.7 | ND |

| 166 | – | M protein trans-acting positive-regulator-like protein | 4.8 | ND |

| 1819c | – | Transposase | 4.6 | ND |

| Metabolism | ||||

| 1616c | – | Oxidoreductase | 5.0 | 7 |

| 457 | – | Glycosyl transferase | 3.7 | 4 |

| 201 | – | Carbonic anhydrase | 3.0 | −2 |

| 876-877 | – | GTP pyrophosphokinase | 2.8 | 3 |

| 1697 | pflD | Pyruvate formate lyase 3 | 2.3 | −2 |

| 725-726 | – | Rhodanese super family protein | 2.2 | – |

| Transport | ||||

| 548 | pepD | Dipeptidase A | 16.1 | 2 |

| 1661 | dppB | Dipeptide transport system permease protein DppB | 8.0 | – |

| 862-863 | – | l-Malate permease | 3.2 | 2 |

| 1140 | fdhC | Formate transporter | 2.6 | – |

| 876-877 | – | Chloride channel protein | 2.8 | 3 |

| Repair | ||||

| 1160c | phr | Deoxyribodipyrimidine photolyase | 5.9 | 3 |

Genes are categorized based on KEGG genome annotations. Spy49 numbers are the open reading frames based on the S. pyogenes strain NZ131 genome annotation (43). Contiguous genes likely to be cotranscribed are separated by a hyphen. Where a Spy49 number is underlined, the description is specific to the underlined Spy49 gene designation.

A dash indicates that the gene is not named.

ChIP-chip fold enrichment was calculated as a ratio of signal intensity between the SA5 and rgg mutant strains.

Fold changes in the transcript levels are from the previous study (26). A dash indicates that no change in the transcript level was observed. WT, wild type; ND, not determined.

Fig 1.

Noncoding DNA was enriched more than coding DNA. The level of DNA enrichment for each Rgg binding site was plotted, and the means were compared by using the Student t test. The difference was significant (P < 0.0001).

Fig 2.

Functions associated with noncoding and coding DNA regions bound by Rgg during the exponential phase of growth.

Rgg binds to noncoding DNA upstream of horizontally transmissible DNA.

Rgg bound upstream of three genes encoding transposases (Table 3). Two of these (spy49_1819c, which encodes a 328-amino-acid transposase, and spy49_1032, which encodes a 74-amino-acid transposase) were adjacent to each other and within a single insertion sequence element. The third (spy49_0677c, which encodes a 72-amino-acid transposase) was adjacent to a gene encoding an IgG endopeptidase known as MAC (35). In addition, Rgg bound to noncoding DNA upstream of a putative transcriptional regulator (Spy_0166) associated with a different transposon (Table 3).

Rgg bound to four unique sites within the noncoding DNA of two prophages designated ϕNZ131.2 and ϕNZ131.3 (Table 3). Two sites were within ϕNZ131.2, including one upstream of genes encoding a superantigen (streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin H [SpeH]) and a cell wall hydrolase (cwh). A previous report showed that inactivation of rgg altered speH transcript levels (17), suggesting that Rgg directly controls its expression (Table 3).

Similarly, Rgg bound to two sites within ϕNZ131.3 (Table 3). The first site was upstream of three ORFs that are likely to be cotranscribed. Binding was proximal to spy49_1518, which encodes a 62-amino-acid polypeptide with a helix-turn-helix motif and is similar to prophage-encoded transcriptional repressors. Thirty-two base pairs downstream of the spy49_1518 ORF is spy49_1517, which encodes a 242-amino-acid protein that is similar to bacteriophage P1 antirepressors. The third ORF in the putative operon (with a start codon 31 bp downstream of spy49_1517) is spy49_1518, which predicts a 62-amino-acid (7.4-kDa) polypeptide with a helix-turn-helix motif. Each of the three ORFs is preceded by a putative ribosome binding site. The second binding site within ϕNZ131.3 was upstream of spy49_1529, which encodes a 252-amino-acid bacteriophage transcriptional repressor and is likely to be cotranscribed with a gene encoding a superinfection immunity protein (Spy49_1530).

Rgg binds to noncoding DNA upstream of genes involved in metabolism and DNA repair.

In the presence of glucose, the major fermentation product of S. pyogenes is lactic acid. However, during aerobiosis, carbohydrate limitation, or the presence of carbohydrates other than glucose, there is a metabolic shift from homolactate to mixed-acid fermentation, which is mediated, in part, by pyruvate formate lyase (PFL) (44, 46). Rgg bound to DNA upstream of pfl (Table 3). Previously, rgg inactivation was associated with decreased pfl expression (14, 26), suggesting that Rgg directly activates transcription.

Rgg also bound to the noncoding DNA upstream of a gene encoding carbonic anhydrase (Table 3), which catalyzes the reversible hydration of CO2 to bicarbonate (HCO3−). Carbonic anhydrase is essential for the growth and survival of Streptococcus pneumoniae in an ambient air environment (10). A previous transcriptome analysis also showed changes in carbonic anhydrase transcripts between the wild type and the rgg mutant, suggesting that Rgg directly regulates its expression (26).

Deoxyribodipyrimidine photolyases remove pyrimidine dimers (59). Rgg bound to the noncoding region upstream of the photolyase for which transcript level changes were observed between the wild type and the rgg mutant (Table 3). Photolyases are important for Bacillus subtilis endospores to survive high doses of UV radiation and presumably are involved in DNA repair in S. pyogenes (52).

Rgg binds to noncoding DNA upstream of several virulence-associated genes.

Rgg bound to noncoding DNA upstream of genes encoding the antiphagocytic M protein (20, 21, 56), SOF (57), SfbX49 (30), and streptococcal collagen-like surface protein B (SclB) (19). Each gene product is localized to the cell surface and covalently attached to peptidoglycan, and each is thought to contribute to virulence (19, 20, 21, 29, 47, 57). Previous analyses showed that Rgg represses the expression of each of the genes (26), suggesting that the protein directly represses their expression. In addition, Rgg bound to noncoding DNA upstream of a gene (spy49_1335) encoding a protein with a type II secretion peptide and an esterase motif (Table 3); however, expression of spy49_1335 was similar between the wild-type NZ131 strain and the rgg mutant (26).

Rgg binds to noncoding DNA upstream of genes encoding transcriptional regulators.

In addition to binding proximally to transcriptional regulatory genes present within horizontally transmissible DNA, Rgg bound to noncoding DNA adjacent to six chromosomal genes encoding transcriptional regulators (Table 3). There were no detectable changes in the expression of four of these in an rgg mutant strain; however, expression of both spy49_725 and spy49_1113c was altered following inactivation of rgg (26) (Table 3). spy49_725 encodes a LysR family transcriptional regulator, which contributes to virulence, metabolism, and quorum sensing (38). spy49_1113c is a part of the CoiA-like family of proteins induced during competence, although S. pyogenes is not currently known as being naturally competent. In addition, 12 bp downstream of the Spy49_1113c ORF is a gene predicted to encode the oligopeptidase PepB (Spy49_1112c). The results indicate that the Rgg regulatory circuit interacts directly with other regulatory circuits, including those likely to be involved in quorum sensing and competence.

Rgg binds to promoter regions of emm49, sof, and sfbX49 in vitro.

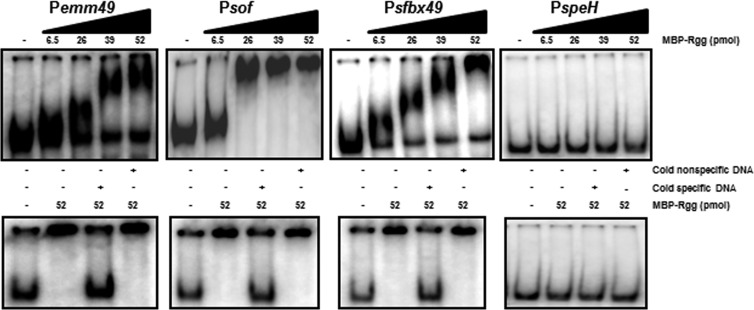

To determine if the Rgg binding sites identified by ChIP-chip analysis were also bound by purified Rgg in vitro, gel shift assays were used. The binding sites upstream of emm49, sof, sfbX49, and speH were selected for analysis because of their role in virulence. Moreover, emm49, sof, and sfbX49 are activated by the transcriptional regulator Mga (29), and thus, it was of interest to investigate the possibility that Mga and Rgg cooperatively regulate their expression. The DNA fragments bound by Rgg were amplified with PCR using chromosomal DNA as a template, end labeled with [γ32P] ATP, and incubated with various amounts of Rgg. Except for speH, Rgg bound specifically to all the targets in vitro, consistent with the ChIP-chip results (Fig. 3). We did not detect binding to PspeH in vitro.

Fig 3.

Gel shift assays of selected Rgg targets. Radiolabeled noncoding DNA (0.1 to 2 ng) upstream of emm49, sof, sfbX49, and speH was incubated with 0, 6.5, 26, 39, or 52 pmol of purified Rgg. Cold nonspecific DNA refers to the addition of unlabeled groEL DNA, and cold specific DNA refers to the addition of unlabeled competing DNA. A 250-fold excess of specific and nonspecific DNA was used in the control reactions.

The inability to detect Rgg binding to the promoter region of speH was surprising because in all other instances, the binding sites identified with ChIP also bound Rgg when assessed with gel shift assays (Fig. 3) (2). To investigate this further, we sought first to confirm the ChIP-chip results. To do so, additional ChIP samples were prepared from exponential-phase cultures and the amount of noncoding DNA upstream of speH was determined by quantitative PCR. The results showed an 8-fold enrichment of the region in SA5 compared to the negative control (data not shown), a finding which supported the conclusion that Rgg binds to noncoding DNA upstream of speH.

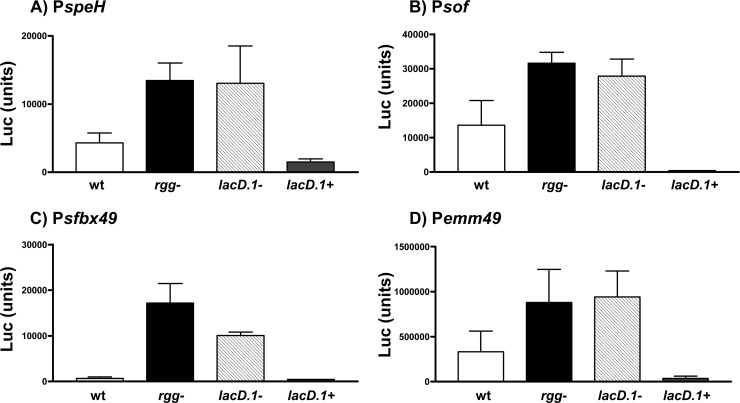

The Rgg binding sites identified with ChIP-chip contain a promoter regulated by both Rgg and LacD.1.

The lack of binding to PspeH in gel shift assays suggested that additional cellular factors required for binding were not present in the reconstituted gel shift assays. Based on previous work (36), one possibility was that Rgg was bound to LacD.1 and that this protein-protein complex was binding to the speH promoter. To test the hypothesis, and to determine if other Rgg binding sites identified contained a functional promoter regulated by Rgg, a transcriptional reporter fusion system was used. In addition to the speH promoter, we also analyzed promoters associated with emm49, sof, and sfbX49. Each DNA region was cloned adjacent to a firefly luciferase reporter gene, and the recombinant plasmids were used to transform wild-type NZ131, an rgg mutant strain, a lacD.1 mutant strain, and the complemented lacD.1 mutant (designated SA6) (Table 1). The transformants were grown to the exponential phase of growth, and promoter activity was measured by quantitating luciferase activity. The results showed that there is a functional promoter in each region of DNA bound by Rgg and that Rgg repressed the promoters associated with emm49, sof, sfbX49, and speH (Fig. 4), supporting the idea that Rgg directly regulates the expression of each of these genes by binding to the promoter regions.

Fig 4.

Repression of speH (A), sof (B), sfbX49 (C), and emm49 (D) was dependent on both Rgg and LacD.1. Firefly reporter fusion plasmids containing the DNA upstream of speH, sof, sfbX49, and emm49 were transformed into the wild type (wt), rgg mutant (rgg−), lacD.1 mutant (lacD.1−), and lacD.1 mutant complemented with the lacD.1 gene (lacD.1+). The strains were grown to the exponential phase of growth, and promoter activity was determined by measuring luciferase. The means and standard errors of the means from three independent experiments are shown.

In the case of PspeH, we speculate that an Rgg-LacD.1 complex may have greater affinity for binding to PspeH than Rgg alone, which may be why binding was detected with ChIP but not gel shift assays. We attempted to test this idea by using gel shift assays with purified Rgg and LacD.1; however, we have been unable to isolate soluble LacD.1 from E. coli (data not shown). Nonetheless, the combination of results obtained by ChIP-chip, ChIP-quantitative PCR (qPCR), and promoter activity assays indicates that Rgg directly regulates speH expression. Overall, the promoter activity assays show that both Rgg and LacD.1 were required for repression, suggesting that the two proteins work together to regulate gene expression in the exponential phase of growth (Fig. 4).

DISCUSSION

We identified 62 sites in the chromosome that were bound by Rgg during the exponential phase of growth. Among sites within noncoding DNA, 70% were adjacent to genes known to be regulated by Rgg, suggesting that Rgg directly controls gene transcription by binding proximally to the cognate promoters. Binding sites were identified both in the core genome and within horizontally acquired DNA, including transposons, insertion sequence elements, and prophages. We also discovered that Rgg binds upstream of important Mga-regulated virulence genes to repress their transcription, including the genes encoding the M protein and SpeH. Together with our previous analyses that identified binding sites in the post-exponential phase of growth, we have identified 125 Rgg binding sites, only two of which were bound by Rgg in both phases of growth. The results indicate that the binding specificity oscillates, presumably due to reversible binding to the regulatory cofactor LacD.1, in response to glycolytic flux. In this regard, we also showed that both LacD.1 and Rgg are required for repression of emm49, sof, sfbX49, and speH in the exponential phase of growth. Overall, these findings provide unique insights into the regulation of virulence-associated genes in S. pyogenes and the mechanisms whereby genome-wide patterns of expression change in response to physiologic signals.

Rgg binds to horizontally transmissible DNA.

Prophages, transposons, insertion sequences, and integrative conjugative elements contribute substantially to the genomic diversity associated with S. pyogenes (3, 6, 43). Previously, we showed that Rgg binds to the promoter region of a prophage-encoded integrase/excisionase (2) and that inactivation of rgg alters the frequency at which the prophage excised from the genome (26). In the current study, Rgg bound to noncoding DNA upstream of three genes encoding transposases (Table 3). Transposition is potentially mutagenic, which is presumably why the process is tightly regulated. Importantly, several bacterial factors known to regulate transposition in other microbes, such as the Lon protease, the integration host factor, and the regulators Lex and SigS (39), are not encoded in the genome of S. pyogenes. We speculate that Rgg may regulate transposition of certain insertion sequence elements and transposons in response to environmental signals. Transposition during periods of stress, such as during the post-exponential phase of growth, may create genetic diversity within the population by insertional mutagenesis, cis effects on the expression of genes adjacent to the element, or the gain/loss of regulatory and structural genes present on transposons. This is likely to accelerate pathogen adaptation. Clearly, additional information regarding the functional significance of Rgg interactions with horizontally transmitted DNA is needed.

The Rgg regulon is characterized by both inter- and intraserotypic variation (25). One possible explanation is that Rgg-mediated regulation of horizontally acquired genes is responsible for this variation. Rgg bound to noncoding DNA upstream of several genes within bacteriophages and transposons that encode not only structural genes, such as integrases/excisionases and transposases, but also transcriptional regulatory proteins. Some of the prophage-encoded regulators are in the Cro/cI family, similar to Rgg. It is of interest to determine if Rgg-mediated changes in the expression of these regulatory proteins, which are part of the pan-genome, influence genome-wide patterns of transcription. If so, this may account for the variation in the regulon among different clinical isolates possessing different horizontally transmissible DNA elements. Such plasticity in global regulatory circuits is likely to provide the pathogen with a means to adapt rapidly to changes in host-pathogen interactions and may contribute to the wide variety of clinical manifestations associated with S. pyogenes infection.

Rgg is a coregulator of virulence-associated genes controlled by Mga and MtsR.

Rgg and LacD.1 both contribute to the regulation of Mga-regulated genes, including emm49, which is typically expressed in the exponential phase of growth (29). Previously, inactivation of rgg was associated with an increase in the expression of the Mga-regulated proteins M49, SOF, and C5a peptidase; however, this was thought to be a secondary effect resulting from changes in the expression of other regulatory genes (17). Results from the current study show direct binding of Rgg to promoters of Mga-regulated genes. Rgg and Mga have opposing influences on expression, with Mga activating expression and Rgg repressing expression. Presumably, the two work in concert, along with LacD.1, to fine-tune expression levels in response to physiologic signals. Interestingly, both Rgg—via LacD.1—and Mga—via interaction with CcpA—respond to signals associated with carbohydrate availability (1).

The genes encoding Sof49 and SfbX49A are approximately 8.5 kb upstream of mga. The ORFs are adjacent, transcribed in the same orientation, and separated by 179 bp of intergenic DNA. Previously, the genes were shown to be cotranscribed in strain NZ131 by a promoter located upstream of sof (30). Here, we found that Rgg bound to DNA upstream of each ORF (Table 3 and Fig. 3). In addition, the results showed that the intergenic DNA also contains an active promoter that is repressed by both Rgg and LacD.1 (Fig. 4). Thus, sfbX49 can be both cotranscribed with sof and transcribed independently.

SOF, SfbX49, and M49 all bind to fibronectin or fibrinogen to mediate adherence or inhibit phagocytosis (21, 28, 47). Rgg is required for expression of the secreted cysteine protease SpeB (15, 37). SpeB substrates include fibronectin, fibrinogen, the M protein, and fibronectin-binding proteins localized to the surface of strain NZ131 (11, 16, 31, 49). Thus, in addition to repressing the transcription of the surface-localized gene products, Rgg also controls their expression posttranslationally via regulation of the SpeB protease.

The DNA sequence of the Mga binding site determined by McIver et al. in a serotype M6 isolate is 78% identical to the sequence of the Rgg binding region in the M49 strain used in the current study (42). The differences in binding sequences among isolates may influence the affinity of Mga and Rgg binding to target DNAs and thus influence expression in an isolate-specific manner.

Noncoding DNA upstream of mtsR was enriched approximately 12-fold in ChIP-chip samples (Table 3). Previous studies showed that Rgg represses mtsR transcription 2-fold (26). MtsR is a regulatory protein involved in several metabolic processes, including metal homeostasis (5, 7). MtsR also contributes to virulence as determined with zebrafish, murine, and nonhuman primate models of S. pyogenes invasive disease (5, 48). Moreover, a naturally occurring mtsR mutant is associated with a decreased propensity to cause necrotizing fasciitis in humans (48). The expression of the peptidyl-prolyl isomerase PrsA is greater in the mutant, decreasing the abundance of extracellular cysteine protease SpeB (48). Therefore, in addition to activating speB transcription, Rgg further controls extracellular SpeB production posttranslationally by influencing the expression of PrsA through changes in MtsR expression (48). Thus, Rgg both directly and indirectly influences virulence gene expression and is an important determinant in the outcome of infection.

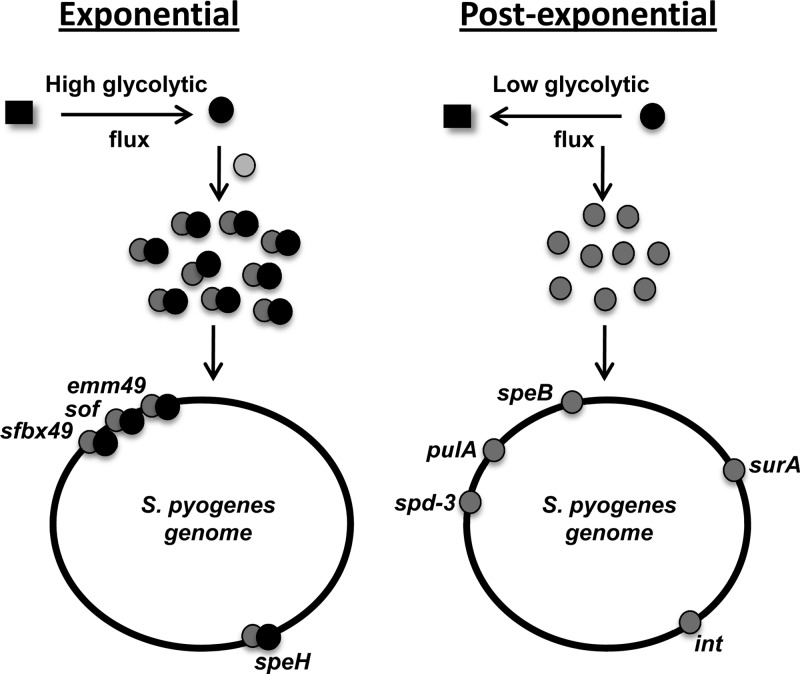

Growth phase-dependent regulation via LacD.1 modulation of Rgg binding specificity.

Loughman and Caparon (36) previously proposed a model of Rgg-mediated regulation of speB whereby during the exponential phase of growth, LacD.1 interacts with Rgg such that Rgg cannot bind to the speB promoter to activate expression. Previous results obtained with ChIP-qPCR confirmed that binding to the speB promoter region occurred only in the post-exponential phase of growth (2). Here, we tested the prediction that LacD.1 is involved in Rgg-mediated repression of emm49, sof49, sfbX49, and speH in the exponential phase of growth by using transcriptional reporter assays. The results showed that LacD.1 contributes to the regulation of these promoters, which are bound by Rgg both in vivo (Table 3) and, with the exception of speH, in vitro. The results suggest that LacD.1 and Rgg form a complex during the exponential phase of growth in response to the concentration of glycolytic intermediates, as previously proposed (36). Thus, LacD.1 binding to Rgg does not sequester Rgg from DNA binding but alters its binding specificity (Fig. 5).

Fig 5.

Growth phase modulation of Rgg binding specificity. In the exponential phase of growth, elevated glycolytic flux promotes a LacD.1 conformation (black circles) that forms a complex with Rgg (gray circles). Together, the proteins bind to Pemm49, PsfbX49, Psof, and PspeH to repress transcription. In the post-exponential phase of growth, decreased glycolytic flux causes a conformational change in LacD.1 that results in dissociation from Rgg and a change in the binding specificity of Rgg.

Paralogues of Rgg, designated Rgg2 and Rgg3, are involved in quorum sensing in S. pyogenes and bind to signaling peptides, which presumably influence the specificity of DNA binding (12). This signaling pathway was also shown to be important in regulating biofilm formation (12). In addition, Rgg binds to the secretion signal peptide derived from virulence factor protein, which alters its regulation of speB expression (55). Therefore, in addition to LacD.1, modulation of Rgg binding in response to catabolism is likely to be influenced by the accumulation of signaling peptides via quorum sensing.

Despite the identification of 125 Rgg binding sites, a conserved binding motif was not identified. While the reason for this is unclear, chromatin compaction and remodeling may influence Rgg binding to DNA. For example, the factor for inversion stimulation (FIS) protein changes the topology of the E. coli chromosome in a growth phase-dependent manner (54). Similar data are not available in S. pyogenes; however, the potential impact of differences in DNA topology in the exponential and post-exponential phases of growth may obscure identification of conserved sequence motifs.

In summary, the results showed that the genome-wide DNA binding characteristics of Rgg oscillate in a growth phase-dependent manner, probably through reversible binding to the coregulator LacD.1. Although Rgg bound to both coding and noncoding DNA, binding was markedly biased toward noncoding DNA and in many cases was specific to the promoter regions of known Rgg-regulated genes. The results identified, for the first time, a regulator of a bacteriophage superantigen and also showed that Rgg and LacD.1 work in concert to influence the expression of Mga-regulated genes. Overall, the results indicate that Rgg is an important regulator of virulence and horizontally acquired genes associated with prophages and insertion sequences and contribute to our general understanding of how the pathogen modulates genome-wide patterns of expression in response to changes in its environment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Adhar Manna, Alex Erkine, and Lisa Kuechenmeister for technical assistance and Heidi Senst for assistance constructing strains.

Funding was provided by the Mid-American Consortium on Gram-Positive Pathogens, the Sanford School of Medicine of the University of South Dakota and the University of Nebraska Medical Center, and by NIH grant 2 P20 RR016479 from the INBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 May 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Almengor AC, Kinkel TL, Day SJ, McIver KS. 2007. The catabolite control protein CcpA binds to Pmga and influences expression of the virulence regulator Mga in the group A streptococcus. J. Bacteriol. 189:8405–8416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anbalagan S, McShan WM, Dunman PM, Chaussee MS. 2011. Identification of Rgg binding sites in the Streptococcus pyogenes chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 193:4933–4942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Banks DJ, Beres SB, Musser JM. 2002. The fundamental contribution of phages to GAS evolution, genome diversification and strain emergence. Trends Microbiol. 10:515–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barnett TC, Bugrysheva JV, Scott JR. 2007. Role of mRNA stability in growth phase regulation of gene expression in the group A streptococcus. J. Bacteriol. 189:1866–1873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bates CS, Toukoki C, Neely MN, Eichenbaum Z. 2005. Characterization of MtsR, a new metal regulator in group A streptococcus, involved in iron acquisition and virulence. Infect. Immun. 73:5743–5753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beres SB, Musser JM. 2007. Contribution of exogenous genetic elements to the group A streptococcus metagenome. PLoS One 2:e800 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beres SB, et al. 2006. Molecular genetic anatomy of inter- and intraserotype variation in the human bacterial pathogen group A streptococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:7059–7064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borukhov S, Nudler E. 2003. RNA polymerase holoenzyme: structure, function and biological implications. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6:93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buchanan JT, et al. 2006. DNase expression allows the pathogen group A streptococcus to escape killing in neutrophil extracellular traps. Curr. Biol. 16:396–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burghout P, et al. 2010. Carbonic anhydrase is essential for Streptococcus pneumoniae growth in environmental ambient air. J. Bacteriol. 192:4054–4062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carroll RK, Musser JM. 2011. From transcription to activation: how group A streptococcus, the flesh-eating pathogen, regulates SpeB cysteine protease production. Mol. Microbiol. 81:588–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chang JC, LaSarre B, Jimenez JC, Aggarwal C, Federle MJ. 2011. Two group A streptococcal peptide pheromones act through opposing Rgg regulators to control biofilm development. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002190 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chaussee MA, Callegari EA, Chaussee MS. 2004. Rgg regulates growth phase-dependent expression of proteins associated with secondary metabolism and stress in Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 186:7091–7099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chaussee MA, Dmitriev AV, Callegari EA, Chaussee MS. 2008. Growth phase-associated changes in the transcriptome and proteome of Streptococcus pyogenes. Arch. Microbiol. 189:27–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chaussee MS, Ajdic D, Ferretti JJ. 1999. The rgg gene of Streptococcus pyogenes NZ131 positively influences extracellular SPE B production. Infect. Immun. 67:1715–1722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chaussee MS, Cole RL, van Putten JP. 2000. Streptococcal erythrogenic toxin B abrogates fibronectin-dependent internalization of Streptococcus pyogenes by cultured mammalian cells. Infect. Immun. 68:3226–3232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chaussee MS, et al. 2002. Rgg influences the expression of multiple regulatory loci to coregulate virulence factor expression in Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 70:762–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chaussee MS, Watson RO, Smoot JC, Musser JM. 2001. Identification of Rgg-regulated exoproteins of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Immun. 69:822–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen SM, et al. 2010. Streptococcal collagen-like surface protein 1 promotes adhesion to the respiratory epithelial cell. BMC Microbiol. 10:320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Courtney HS, Bronze MS, Dale JB, Hasty DL. 1994. Analysis of the role of M24 protein in group A streptococcal adhesion and colonization by use of omega-interposon mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 62:4868–4873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Courtney HS, Hasty DL, Dale JB. 2006. Anti-phagocytic mechanisms of Streptococcus pyogenes: binding of fibrinogen to M-related protein. Mol. Microbiol. 59:936–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Courtney HS, Zhang YM, Frank MW, Rock CO. 2006. Serum opacity factor, a streptococcal virulence factor that binds to apolipoproteins A-I and A-II and disrupts high density lipoprotein structure. J. Biol. Chem. 281:5515–5521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cunningham MW. 2000. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13:470–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cunningham MW. 2008. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections and their sequelae. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 609:29–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dmitriev AV, McDowell EJ, Chaussee MS. 2008. Inter- and intraserotypic variation in the Streptococcus pyogenes Rgg regulon. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 284:43–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dmitriev AV, et al. 2006. The Rgg regulator of Streptococcus pyogenes influences utilization of nonglucose carbohydrates, prophage induction, and expression of the NAD-glycohydrolase virulence operon. J. Bacteriol. 188:7230–7241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fontaine L, et al. 2010. A novel pheromone quorum-sensing system controls the development of natural competence in Streptococcus thermophilus and Streptococcus salivarius. J. Bacteriol. 192:1444–1454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gillen CM, et al. 2008. Opacity factor activity and epithelial cell binding by the serum opacity factor protein of Streptococcus pyogenes are functionally discrete. J. Biol. Chem. 283:6359–6366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hondorp ER, McIver KS. 2007. The Mga virulence regulon: infection where the grass is greener. Mol. Microbiol. 66:1056–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jeng A, et al. 2003. Molecular genetic analysis of a group A streptococcus operon encoding serum opacity factor and a novel fibronectin-binding protein, SfbX. J. Bacteriol. 185:1208–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kansal RG, Nizet V, Jeng A, Chuang WJ, Kotb M. 2003. Selective modulation of superantigen-induced responses by streptococcal cysteine protease. J. Infect. Dis. 187:398–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kietzman CC, Caparon MG. 2010. CcpA and LacD.1 affect temporal regulation of Streptococcus pyogenes virulence genes. Infect. Immun. 78:241–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kinkel TL, McIver KS. 2008. CcpA-mediated repression of streptolysin S expression and virulence in the group A streptococcus. Infect. Immun. 76:3451–3463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kreikemeyer B, McIver KS, Podbielski A. 2003. Virulence factor regulation and regulatory networks in Streptococcus pyogenes and their impact on pathogen-host interactions. Trends Microbiol. 11:224–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lei B, Mackie S, Lukomski S, Musser JM. 2000. Identification and immunogenicity of group A streptococcus culture supernatant proteins. Infect. Immun. 68:6807–6818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Loughman JA, Caparon MG. 2006. A novel adaptation of aldolase regulates virulence in Streptococcus pyogenes. EMBO J. 25:5414–5422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lyon WR, Gibson CM, Caparon MG. 1998. A role for trigger factor and an rgg-like regulator in the transcription, secretion and processing of the cysteine proteinase of Streptococcus pyogenes. EMBO J. 17:6263–6275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maddocks SE, Oyston PC. 2008. Structure and function of the LysR-type transcriptional regulator (LTTR) family proteins. Microbiology 154:3609–3623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mahillon J, Chandler M. 1998. Insertion sequences. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:725–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Malke H, Mechold U, Gase K, Gerlach D. 1994. Inactivation of the streptokinase gene prevents Streptococcus equisimilis H46A from acquiring cell-associated plasmin activity in the presence of plasminogen. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 116:107–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McIver KS. 2009. Stand-alone response regulators controlling global virulence networks in Streptococcus pyogenes. Contrib. Microbiol. 16:103–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McIver KS, Heath AS, Green BD, Scott JR. 1995. Specific binding of the activator Mga to promoter sequences of the emm and scpA genes in the group A streptococcus. J. Bacteriol. 177:6619–6624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McShan WM, et al. 2008. Genome sequence of a nephritogenic and highly transformable M49 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 190:7773–7785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Melchiorsen CR, et al. 2000. Synthesis and posttranslational regulation of pyruvate formate-lyase in Lactococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 182:4783–4788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Neely MN, Lyon WR, Runft DL, Caparon M. 2003. Role of RopB in growth phase expression of the SpeB cysteine protease of Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 185:5166–5174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Neijssel OM, Snoep JL, Teixeira de Mattos MJ. 1997. Regulation of energy source metabolism in streptococci. Soc. Appl. Bacteriol. Symp. Ser. 26:12S–19S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Oehmcke S, Podbielski A, Kreikemeyer B. 2004. Function of the fibronectin-binding serum opacity factor of Streptococcus pyogenes in adherence to epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 72:4302–4308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Olsen RJ, et al. 2010. Decreased necrotizing fasciitis capacity caused by a single nucleotide mutation that alters a multiple gene virulence axis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:888–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Raeder R, Woischnik M, Podbielski A, Boyle MD. 1998. A secreted streptococcal cysteine protease can cleave a surface-expressed M1 protein and alter the immunoglobulin binding properties. Res. Microbiol. 149:539–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rawlinson EL, Nes IF, Skaugen M. 2005. Identification of the DNA-binding site of the Rgg-like regulator LasX within the lactocin S promoter region. Microbiol. 151:813–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rawlinson EL, Nes IF, Skaugen M. 2002. LasX, a transcriptional regulator of the lactocin S biosynthetic genes in Lactobacillus sakei L45, acts both as an activator and a repressor. Biochimie 84:559–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rebeil R, Nicholson WL. 2001. The subunit structure and catalytic mechanism of the Bacillus subtilis DNA repair enzyme spore photoproduct lyase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:9038–9043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sanders JW, Venema G, Kok J, Leenhouts K. 1998. Identification of a sodium chloride-regulated promoter in Lactococcus lactis by single-copy chromosomal fusion with a reporter gene. Mol. Gen. Genet. 257:681–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Schneider R, et al. 2001. An architectural role of the Escherichia coli chromatin protein FIS in organising DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:5107–5114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Shelburne SA, III, et al. 2011. An N-terminal signal peptide of Vfr protein negatively influences RopB-dependent SpeB expression and attenuates virulence in Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 82:1481–1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Smeesters PR, McMillan DJ, Sriprakash KS. 2010. The streptococcal M protein: a highly versatile molecule. Trends Microbiol. 18:275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Timmer AM, et al. 2006. Serum opacity factor promotes group A streptococcal epithelial cell invasion and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 62:15–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vickerman MM, Sulavik MC, Clewell DB. 1995. Oral streptococci with genetic determinants similar to the glucosyltransferase regulatory gene, rgg. Infect. Immun. 63:4524–4527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Weber S. 2005. Light-driven enzymatic catalysis of DNA repair: a review of recent biophysical studies on photolyase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1707:1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.