Abstract

Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain TCE1 is capable of metabolically reducing tetra- and trichloroethenes by organohalide respiration. A previous study revealed that the pce gene cluster responsible for this process is located on an active composite transposon, Tn-Dha1. In the present work, we investigated the effects on the stability of the transposon during successive subcultivations of strain TCE1 in a medium depleted of tetrachloroethene. At the physiological level, an increased fitness of the population was observed after 9 successive transfers and was correlated with a decrease in the level of production of the PceA enzyme. The latter observation was a result of the gradual loss of the pce genes in the population of strain TCE1 and not of a regulation mechanism, as was postulated previously for a similar phenomenon described for Sulfurospirillum multivorans. A detailed molecular analysis of genetic rearrangements occurring around Tn-Dha1 showed two independent but concomitant events, namely, the transposition of the first insertion sequence, ISDha1-a, and homologous recombination across identical copies of ISDha1 flanking the transposon. A new model is proposed for the genetic heterogeneity around Tn-Dha1 in D. hafniense strain TCE1, along with some considerations for the cleavage mechanism mediated by the transposase TnpA1 encoded by ISDha1.

INTRODUCTION

Organohalide respiration (OHR) is a bacterial metabolic process that couples the reduction of organic halogenated compounds to energy conservation in a number of phylogenetically diverse anaerobic bacteria (2, 7). OHR bacteria can be classified according to two metabolic strategies: some are restricted to OHR for growth (members of the genera Dehalobacter and Dehalococcoides), while others are metabolically versatile (Desulfitobacterium and Sulfurospirillum) (see reference 13 for a recent review). The catalytic key enzyme in OHR is the reductive dehalogenase (RdhA), displaying conserved features, such as a Tat (twin-arginine translocation) (21) signal peptide, two FeS clusters, and the presence of a corrinoid cofactor at the active site (2). All rdhA genes identified in general databases are systematically accompanied by a second open reading frame (ORF), rdhB, which has a conserved secondary structure made of two or three transmembrane α-helices and was proposed previously to play a role in the anchoring of RdhA at the cytoplasmic membrane (16).

A highly conserved four-gene cluster was isolated a few years ago in our laboratory from the metabolically versatile Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain TCE1 and from Dehalobacter restrictus, which displays a restricted energy metabolism. This gene cluster (pceABCT) encodes the key enzyme PceA in tetrachloroethene (PCE) respiration (12). A clear composite transposon (Tn) structure (Tn-Dha1) was identified, flanking the pce gene cluster in the former organism, indicating some genomic plasticity. Tn-Dha1 is composed of two identical insertion sequences (ISs) (ISDha1, belonging to the IS256 family) surrounding the pce gene cluster and two additional ORFs. Indirect indications for circular IS and Tn intermediates have been obtained, suggesting an active transposition of Tn-Dha1 in strain TCE1. The pceA promoter sequence has been found to be strong and partially encoded in the right inverted repeat (IR) (IRR) of the first IS copy (ISDha1-a) (12). The presence of rdh genes on mobile genetic elements was later shown to be a common feature of many rdh gene clusters, as in the cases of similar transposons in other Desulfitobacterium isolates (3, 14) and as in the genomes of Dehalococcoides isolates, where rdh genes are part of highly plastic regions (15, 20, 22). Futagami and coworkers previously described the occurrence of genetic rearrangements in D. hafniense strain Y51 leading to partial deletions of a similar pce transposon and, consequently, to nondechlorinating mutants (3, 4). Individual clones have been obtained with two major deletion patterns, one with the excision of one IS copy and the other one as a result of homologous recombination across the two IS copies (3, 4).

A recent proteomic study performed in our laboratory on D. hafniense strain TCE1 delivered an unforeseen high level of the PceA protein when strain TCE1 was cultivated on PCE compared to fumarate as the electron acceptor, despite seemingly constitutive pceA gene expression (18). This observation was revealed to be the result of a dramatic decrease in the pceA gene copy number within the bacterial population upon prolonged subcultivation with fumarate as the electron acceptor, in the absence of PCE.

In the present study, we aimed at a thorough description of the structure of Tn-Dha1 and similar transposons and at a better understanding of the molecular events underlying the heterogeneity of the strain TCE1 population around Tn-Dha1 and the pce gene cluster. For this purpose, we used an approach inspired by a recent study on the reductive dehalogenase of Sulfurospirillum multivorans (8). Starting from a culture routinely cultivated on PCE, we transferred strain TCE1 into a medium containing fumarate and successively transferred the culture 30 times in the absence of PCE. The fate of Tn-Dha1 was monitored throughout at the molecular level, which allowed the establishment of a new model of the genetic rearrangements responsible for the heterogeneity in the population of D. hafniense strain TCE1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain TCE1 (DSM 12704) (5) was cultivated in rubber-stopper-sealed serum glass bottles under anaerobic conditions at 30°C. The medium was prepared as described previously (18). Lactate (45 mM) was used as the electron donor, and either PCE (2 M stock solution in hexadecane, corresponding to a continuous supply of 0.4 mM in the aqueous phase) or fumarate (20 mM) was used as the terminal electron acceptor.

Cell harvest and sample preparation.

Cells from successive culture transfers were routinely harvested after 2 or 3 days of cultivation. The optical density (OD) was recorded at 600 nm, and cells of culture volumes of 25 and 50 ml were collected for DNA and protein extraction, respectively, by 10 min of centrifugation at 4°C and at 4,800 × g. Cells were washed in 1 ml of cold 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) and pelleted again by 2 min of centrifugation at 6,500 × g. Pellets were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until processing. Total DNA was extracted with the Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The DNA concentration was measured with a NanoDrop apparatus (NanoDrop ND-1000).

Oligonucleotides and DNA amplification.

Oligonucleotides were designed by using Primer 3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3) and ordered at Microsynth (Switzerland). Oligonucleotides used in this study were reported previously (12, 18), except for IS9f (5′-ACTTTGCCGTCTTCAAGCG-3′) and R2r (5′-TGGGCAGAAATCCACTAAGC-3′) (Fig. 1A; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). Genomic DNA was amplified by PCR in a thermocycler (Biometra) by mixing 6.65 μl of double-distilled water (ddH2O), 1 μl of 10× PCR buffer S (Peqlab), 0.3 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) at 2.5 mM, 0.5 μl of 10 μM primer, and 0.05 μl of Taq polymerase at 5 U/μl (Peqlab). One microliter of DNA at 0.1 ng/μl was added as the template. The PCR program was designed as follows: 5 min of initial denaturation at 95°C; 30 cycles of amplification with each cycle, including 30 s of denaturation at 95°C, 40 s of primer annealing at 55°C, and 90 s of elongation at 72°C; and a final elongation step for 10 min at 72°C, which was added at the end. PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis or with a Bioanalyzer instrument (Agilent Technologies). When necessary, PCR products were purified with the Montage PCR purification kit (Millipore), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

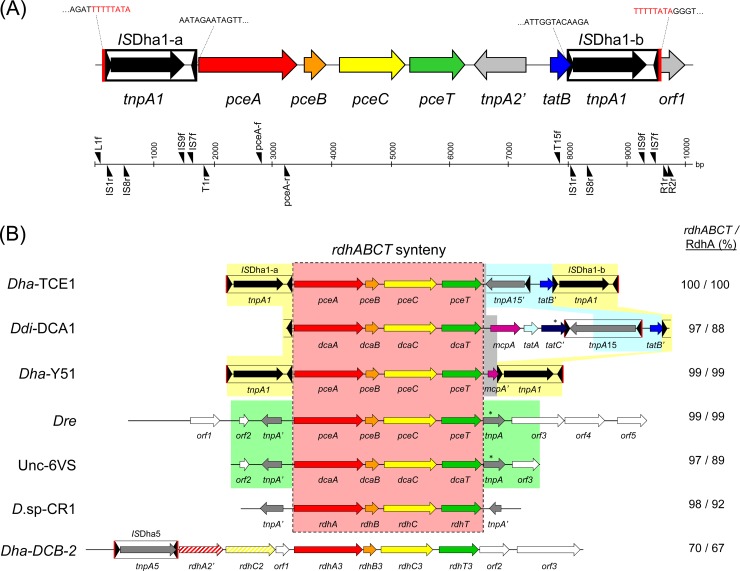

Fig 1.

Genetic map of Tn-Dha1 from D. hafniense strain TCE1 and related genetic structures. (A) Tn-Dha1 contains 6 ORFs, including the conserved pceABCT gene cluster, and is flanked by two identical copies of the insertion sequence ISDha1. Above the map are the sequences of each IS site (with Tn-Dha1 direct repeats in red). The scale (base pairs) and the primers used in this study are depicted below. (B) The Tn-Dha1 transposon isolated from D. hafniense strain TCE1 compared to 6 other related genetic structures for which the 4-gene cluster rdhABCT (red box) displays 97 to 99% sequence identity at the DNA level. In addition, a gene cluster from D. hafniense strain DCB-2, which shares 70% identity, is given. Depicted in yellow shading are additional conserved structures of the composite transposon present in D. hafniense strains TCE1 and Y51 and in D. dichloroeliminans strain DCA1. In D. hafniense TCE1, a short fragment of 115 bp directly downstream of pceT is conserved in both D. dichloroeliminans DCA1 and D. hafniense Y51, while this sequence is extended (400 bp) between D. dichloroeliminans DCA1 and D. hafniense Y51, including the 3′ end of the mcpA gene (gray shading). The remaining sequence of the D. hafniense TCE1 transposon was found to be completely conserved, with an extended region present in the D. dichloroeliminans DCA1 transposon (blue shading). The analysis of the latter allowed the definition of a new insertion sequence (ISDha15, deposited in ISFinder [http://www-is.biotoul.fr/]). The green shading highlights the full conservation of the gene cluster in Dehalobacter restrictus and the cluster present in a uncultured metagenomic DNA isolated from a 1,2-dichloroethane (1,2-DCA)-contaminated site (Unc-6VS). Red vertical bars around ISs indicate the presence of direct repeats. Stars above genes represent single mutations interrupting the corresponding open reading frames. Sequence homologies of the rdhABCT gene cluster (DNA level) and the reductive dehalogenase (protein level) are compared to D. hafniense strain TCE1. Dha-TCE1, Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain TCE1 (12); Ddi-DCA1, Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1 (14); Dha-Y51, Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain Y51 (4); Dre, Dehalobacter restrictus strain PER-K23 (12); Unc-6VS, uncultured metagenomic DNA (14); D.sp-CR1, Desulfitobacterium sp. strain CR1 (GenBank accession number AB301952); Dha-DCB-2, Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain DCB-2 (9).

DNA sequencing.

Sequencing reactions were performed in an in-house facility with the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems), according methods reported previously (17). Samples were run on an ABI Prism 3130 genetic analyzer, and the sequences were analyzed with the DNAStar software package.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis.

For the immunological detection of PceA, strain TCE1 cells were resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), according to the rule of 1 ml per g of biomass (wet weight). Cell suspensions were boiled in 2× loading buffer and run on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and Western blots as described previously (11). Purified anti-PceA antibodies (A. Duret, unpublished data) were diluted 1:20 in a 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-Tween 20 (0.1%) (PBS-T) solution for immunological detection. PceA proteins were finally detected with a goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugate (Bio-Rad) at a dilution of 1:3,000 in PBS-T. HRP activity was revealed colorimetrically with 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole, as previously described (24).

RESULTS

For Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain TCE1, a composite transposon containing the pceABCT gene cluster was described previously (Tn-Dha1) (Fig. 1A) (12). A new, detailed analysis of the conserved rdhABCT gene cluster present in various Desulfitobacterium strains and in Dehalobacter restrictus confirmed the very high level of sequence identity (Fig. 1B, red-shaded box). Moreover, the dcaABCT gene cluster identified in the draft genome of Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1 (14) is also surrounded by a transposon structure. Synteny analysis revealed further sequence conservation between the region downstream of pceT in Tn-Dha1 of D. hafniense TCE1 and a portion of the corresponding region in the D. dichloroeliminans DCA1 transposon (Fig. 1B, blue shading). Although the overall pceABCT gene cluster of D. hafniense TCE1 and the overall dcaABCT gene cluster of D. dichloroeliminans DCA1 share 97% sequence identity at the DNA level, only 88% identity is conserved between the amino acid sequences of the corresponding reductive dehalogenases (PceA versus DcaA).

Evolution of the D. hafniense strain TCE1 population upon cultivation in the absence of PCE.

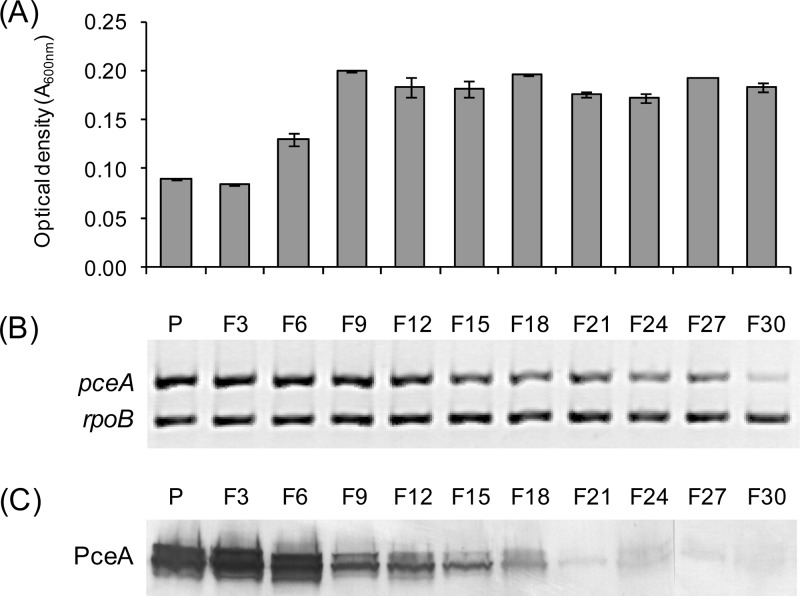

Indications for an active transposon in D. hafniense strain TCE1 were obtained previously (12). In addition, we have recently demonstrated that the reductive dehalogenase PceA disappeared from the proteome of strain TCE1 when it was cultivated for prolonged periods in the absence of PCE (18). In order to assess the role of Tn-Dha1 in the decrease of the pceA gene copy number in strain TCE1, a culture routinely cultivated with PCE as the electron acceptor (culture “P,” as indicated in Fig. 2 to 4) was successively transferred into a liquid medium where fumarate replaced PCE (cultures “F#,” with # indicating the transfer number). Samples for analyses of growth, DNA, and protein were taken after 48 h of cultivation. Surprisingly, the cell density of 2-day-old cultures nearly doubled between transfers F3 and F9, indicating a gradual increase in the fitness of strain TCE1 in the absence of PCE (Fig. 2A). PCR amplification of the pceA gene (compared to rpoB as an internal reference) performed on total DNA taken from the transfer series confirmed previously reported observations (18), i.e., the decrease of the pceA copy number within the strain TCE1 population (Fig. 2B). Western blot analysis of the same transfer series revealed a significant drop in the PceA protein concentration between transfers F6 and F9, which correlated well with the gain in fitness (Fig. 2C). In addition, both pceA transcripts and PceA enzymatic activity confirmed the same trend observed during subcultivation in the absence of PCE (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Fig 2.

Physiological and molecular effects of successive transfers of D. hafniense strain TCE1 in the absence of PCE. Starting from a culture routinely growing with PCE as the electron acceptor (P culture), strain TCE1 was successively transferred 30 times in a medium devoid of PCE. Fumarate was used instead as the electron acceptor (F cultures). (A) Optical densities (absorbance measured at 600 nm) of the successive cultures after 48 h of cultivation. (B) Duplex PCR amplification of fragments of both the pceA (476 bp) and rpoB (289 bp) genes with DNA samples extracted from successive cultures in the absence of PCE. (C) Western blot analysis of the PceA protein (unprocessed [upper] and processed [lower] forms) of total protein samples taken from the same culture series. All experiments were done from duplicate cultures, but only one replicate is depicted for panels B and C.

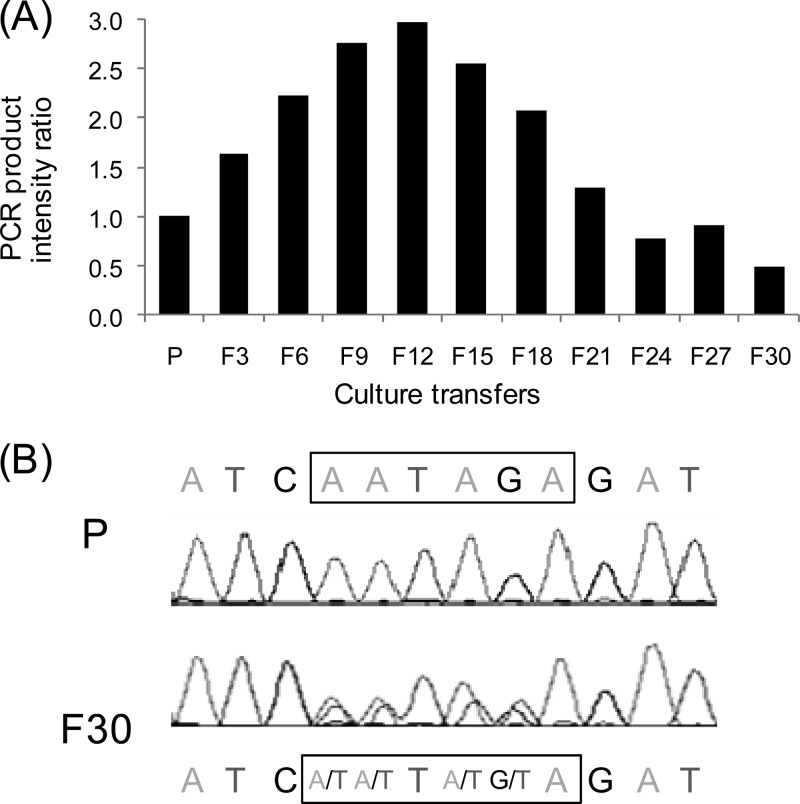

Fig 4.

Evolution of ISDha1 intervening sequences during subcultivation in the absence of PCE. Intervening sequences from ISDha1 excision events were amplified with outward-directed primers targeting ISDha1 in total DNA samples from the subcultivation series. (A) The overall intervening sequences were obtained by PCR with primers IS1r and IS7f. The PCR products were analyzed and quantified by using a Bioanalyzer instrument, and data were normalized with the product obtained from the culture routinely cultivated on PCE (P). (B) Spherograms from the sequencing of ISDha1 junctions using primers IS8r and IS9f. Three conserved positions surrounding the evolving intervening sequence (indicated by the box) are also given. An extended color version of this figure is available in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material.

Differential transposition behavior of ISDha1 copies in the strain TCE1 population.

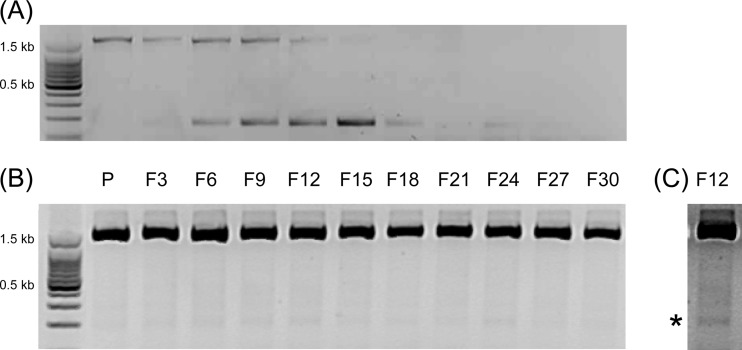

Since the promoter of the pceA gene is partially embedded in the right inverted repeat of ISDha1-a (12), we investigated the stability of ISDha1 copies during subcultivation in the absence of PCE. IS copies were amplified from DNA of the strain TCE1 population by using primers L1f/T1r for ISDha1-a (Fig. 3A) and T15f/R1r for ISDha1-b (Fig. 3B). The ISDha1 copy directly upstream of pceA is readily excised from the transposon structure, as shown by the decrease of the 1,750-bp fragment (including the 1,570-bp-long IS) from culture transfers F6 to F15 along with the increase of the remaining excision site peaking in transfer F15. The second copy (ISDha1-b) did not show any trend over the culture transfers. However, a lower weak band was also visible, which, when confirmed by sequencing, suggested some excision of ISDha1-b (Fig. 3C, indicated by the star).

Fig 3.

Evolution of both ISDha1 copies during subcultivation in the absence of PCE. Direct flanking regions of ISDha1 copies were amplified with total DNA extracted from successive cultures of strain TCE1 in the absence of PCE in the medium (as explained in the legend of Fig. 2). (A and B) The ISDha1-a insertion site was amplified with primers L1f and T1r, resulting in two alternative PCR products (A), while mostly one band was obtained for the insertion site of ISDha1-b with primers T15f and R1r (B). (C) An additional weak band (indicated by the star) was observed, as illustrated for the F12 sample.

Analysis of ISDha1 circular intermediates during subcultivation in the absence of PCE.

ISDha1 belongs to the IS256 family, which has been reported to circularize upon transposition (10, 19). In a previous study, indications were already obtained for circular intermediates of ISDha1 where genomic tandem IS copies could be excluded (12). Here the use of outward-oriented primer pair IS1r/IS7f allowed the amplification of the junction of ISDha1 circles, where both inverted repeats are joined via a short 6-nucleotide stretch, the so-called intervening sequence. The quantification of endpoint PCR products targeting the ISDha1 junction during the subcultivation of strain TCE1 revealed a bell-shaped pattern with a maximum in culture transfer F12 with a 3-fold increase compared to a culture routinely cultivated on PCE (Fig. 4A). PCR products obtained with primer pair IS8r/IS9f from total DNA samples during subcultivation were then directly sequenced, from which the raw data around the intervening sequence are presented in Fig. 4B (see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Here, clearly, only the 6-nucleotide intervening sequence evolved, while the flanking inverted repeats were fully conserved. The intervening sequence in routine cultures on PCE seemed to be exclusively AATAGA; however, a new sequence was increasingly observed during subcultivation on fumarate and was likely to be TTTTTA (Fig. 4B; see also Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

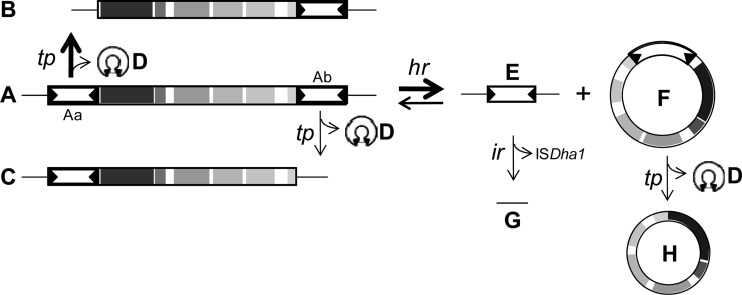

Identification of insertion/excision sites of ISDha1-dependent genetic rearrangements.

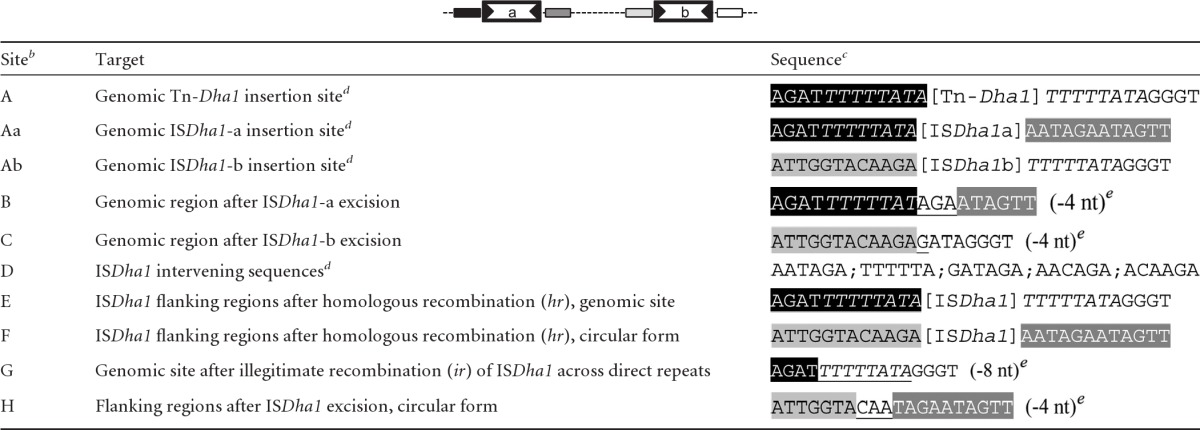

In order to better understand the nature of the genetic rearrangements occurring around Tn-Dha1 in strain TCE1, DNA samples were selected for the cloning and sequencing of the different genomic and circular forms of Tn-Dha1. The excision sites after the transposition of both ISDha1-a and -b copies (sites B and C, respectively) (Table 1) clearly showed a constant loss of 4 nucleotides from the direct flanking regions of the respective IS copies. A comparison of the genomic insertion site of ISDha1-a (site Aa, AGATTTTTTATA-[IS]-AATAGAATAGTT) with the remaining flanking regions after transposition (site B, AGATTTTTTATAGAATAGTT) (Table 1) indicated that TnpA1 introduces staggered breaks in the DNA, as the intervening sequence in circular ISDha1 is made of 6 nucleotides, while only 4 nucleotides are missing at the excision site. PCR amplification with primers L1f and R1r located outside the Tn-Dha1 structure produced two fragments of 1,692 and 114 bp (sites E and G, respectively) (Table 1). The 1,692-bp-long fragment contains a full copy of ISDha1 (1,570 bp) and could be attributed only to homologous recombination across both IS copies of Tn-Dha1, as no loss of nucleotides was observed at the excision site. Indications for a circular recombination intermediate were obtained previously (12) and were confirmed here by PCR amplification with outward-oriented primer pair T1r/T15f (site F) (Table 1). The second short fragment of 114 bp obtained with primers L1f and R1r consisted of the junction of the genomic flanking regions of Tn-Dha1, with 8 (and not 4) nucleotides missing, which correspond to one copy of the direct repeats surrounding Tn-Dha1 (site G, TTTTTATA) (Table 1). In comparison with the circular intermediate of homologous recombination (site F) (Table 1), a second PCR product of 257 bp was obtained with primer pair T1r/T15f, lacking the full IS copy and 4 additional nucleotides (site H) (Table 1), suggesting that the remaining copy of ISDha1 in the circular intermediate was excised by transposition.

Table 1.

Diversity of insertion/excision sites of Tn-Dha1 and ISDha1 copiesa

The diagram at the top depicts the overall Tn-Dha1 structure.

The same letter code is used in Fig. 5.

Tn-Dha1 and ISDha1 sequences are indicated in brackets; direct repeats are italicized; black, dark gray, light gray, and white boxes indicate specific regions around Tn-Dha1 and ISDha1 copies. Nucleotides (nt) coming from either the left or the right flanking site after ISDha1 excision or illegitimate recombination are underlined.

Data taken from reference 12.

Numbers of nucleotides missing from the direct flanking regions of ISDha1 excision are listed in parentheses.

DISCUSSION

Evolution and functional divergence of the conserved rdhABCT gene cluster in Firmicutes.

The pceABCT gene cluster of D. hafniense strain TCE1 was the first cluster of a series isolated from several Desulfitobacterium species and from Dehalobacter restrictus sharing a very high degree of sequence identity. Among them, two major groups can be easily distinguished by the presence or absence of the transposon structure. Our new sequence analysis of these clusters revealed a common rdhABCT synteny that starts exactly at the first nucleotide after the last base of the ISDha1 right inverted repeat and ends about 20 nucleotides after the stop codon of the corresponding rdhT sequence. While it looks very likely that the insertion of ISDha1 is responsible for the genetic heterogeneity at the 5′ end of the rdh clusters, several additional rearrangements must have occurred around the 3′ end. A new insertion sequence (ISDha15, deposited in ISfinder [23]) was also identified in D. dichloroeliminans strain DCA1. ISDha15 belongs to the IS1634 family, shows 80% identity to ISDha9, harbors a unique open reading frame corresponding to a transposase of 526 amino acids, and is likely to duplicate 5 bp upon insertion. Interestingly, ISDha15 seems to have been inserted within and probably inactivated a tatACB operon in D. dichloroeliminans, predicted to encode the components of the twin-arginine translocation machinery. The identified tatB gene is conserved in Tn-Dha1 of D. hafniense strain TCE1, where it was previously misannotated as tatA (12). Confronting the available biochemical data of some reductive dehalogenases (RdhA) produced by these rdh gene clusters together with the identity level of their respective sequence (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), an evolutionary hypothesis implying horizontal gene transfer between Dehalobacter and Desulfitobacterium isolates prior to the substrate divergence of the rdhA gene product could be formulated. Indeed, while the minimal overall sequence identity among the rdh gene clusters is 97%, PceA from D. hafniense strain TCE1 and DcaA from D. dichloroeliminans share only 88% amino acid sequence identity. This strongly suggests that both sequences could have been derived from a common ancestor and then have diverged toward two distinct substrates, PCE and 1,2-dichloroethane (1,2-DCA), respectively, a phenomenon which was postulated previously (14).

Heterogeneity of the D. hafniense strain TCE1 population around transposon Tn-Dha1.

The physiological as well as the molecular patterns observed upon the repeated subcultivation of strain TCE1 in the absence of PCE revealed that the bacterial population became highly heterogeneous with respect to the transposon structure throughout the experiment. The decrease in the level of PceA protein produced (between transfers F3 and F9) and the more progressive diminution of the pceA gene copy number within the strain TCE1 population can be explained by two apparently independent but concomitant genetic events. On the one hand, the transposition of ISDha1-a disrupted the strong constitutive promoter of pceA (12) and gave rise to the interruption of pceA expression. This was clearly correlated with an increase in the growth rate of the population (also between the F3 and F9 subcultures), suggesting that the buildup of active PceA represents a significant energy cost to strain TCE1 and that under conditions of high culture transfer frequencies, cells that are not producing PceA are positively selected. On the other hand, the homologous recombination of Tn-Dha1 across the identical copies of the insertion sequence led to a progressive loss of the entire pce gene cluster within the population. Both genetic rearrangements that take place within the strain TCE1 population can be considered here to be examples of adaptive mutations that are selected in the absence of PCE as the substrate but which would be detrimental in its presence (antagonistic pleiotropy [25]). We have shown previously that the subpopulation of strain TCE1 containing the pce genes could be reselected with an amendment of PCE in the culture medium (18).

Different adaptation processes for the same outcome.

By following the experimental approach employed previously by John and coworkers for Sulfurospirillum multivorans (8), our study highlights a completely different mechanism by which D. hafniense strain TCE1 stopped the production of PceA in the prolonged absence of its substrate, PCE. The direct genetic environments of the pce gene cluster in strain TCE1 already suggested that pceA was strongly and constitutively expressed by the promoter embedded in the vicinal insertion sequence. The disruption of the pceA promoter led to a decrease of the gene expression level. In contrast, in S. multivorans, this phenomenon could not be explained at the genetic level. The detailed molecular analysis of the genetic rearrangements occurring in the dynamic population of D. hafniense strain TCE1 sheds a new light on similar events, which were observed previously in two studies of D. hafniense strain Y51 (3, 4). The transposition activity of ISDesp1 in strain Y51 and homologous recombination across ISDesp1 and ISDesp2 have been detected in a few isolated clones harboring small and large deletions within the transposon TnDesp (3). Our study confirmed that both Desulfitobacterium isolates evolved following a similar adaptive mechanism, which is clearly different from what happened in Sulfurospirillum.

New model for Tn-Dha1-meditated genetic rearrangements occurring in D. hafniense strain TCE1.

The molecular analysis presented above (and summarized in Table 1) led us to reconsider the model of transposition of Tn-Dha1 that was established previously (12) (Fig. 5). First, evidence was given here that individual ISDha1 copies were excised by the action of the transposase TnpA1. The apparent higher transposition rate of ISDha1-a than that of ISDha1-b during subcultivation in the absence of PCE probably has no molecular explanation but was rather the result of a selection of a subpopulation of strain TCE1 that grew faster. Although it was not physically isolated, a circular transposition intermediate containing both IS copies (∼9.5 kb) was proposed previously to occur in strain TCE1 (see Fig. 6B in reference 12). The observed ∼8-kb circular intermediate harboring a single IS copy was previously thought to originate from the 9.5-kb intermediate by transposition. This phenomenon was ruled out in the present study. Indeed, the homologous recombination across identical IS copies (homologous recombination of form A resulting in forms E and F) (Fig. 5) explains the lack of missing nucleotides around the remaining genomic IS copy (form E). In addition, an event of illegitimate recombination was suspected after the sequencing of the short PCR product obtained with primers targeting the flanking regions of Tn-Dha1 (form G) (Table 1 and Fig. 5). In the case of a transposition event of the entire Tn-Dha1 transposon, only 4 nucleotides would be missing at the excision site. In contrast, 8 nucleotides were found to be missing in form G, corresponding to one copy of the Tn-Dha1 direct repeat (TTTTTATA). This indicates that a recombination took place here across the direct repeats, a phenomenon which was reported previously for IS256 and explained by the transposase-independent mechanism of replicational slippage (1, 6).

Fig 5.

Model for genetic rearrangements occurring around Tn-Dha1 in D. hafniense strain TCE1. A combination of transposition (tp) and homologous recombination (hr) or illegitimate recombination (ir) events leads to a variety of genetic structures issued from Tn-Dha1. (A) Genomic integrated complete form of Tn-Dha1; (B) genomic form after transposition of ISDha1-a (Fig. 3A); (C) genomic form after transposition of ISDha1-b (Fig. 3B); (D) circular forms after ISDha1 excision events (including the intervening sequence); (E) single ISDha1 copy remaining after homologous recombination of Tn-Dha1 across the insertion sequences; (F) circular form of Tn-Dha1 after homologous recombination; (G) remaining insertion site after illegitimate recombination of ISDha1 across Tn-Dha1 direct repeats; (H) circular form after transposition of ISDha1 from form F. The same letter code is used in Table 1.

Cleavage patterns of the ISDha1-encoded transposase.

The sequencing of intervening sequences produced during the transposition of ISDha1 copies and of the remaining flanking regions at the excision sites revealed that during transposition, a 6-bp intervening sequence is formed, as observed previously, while 4 bp is systematically missing at the excision sites. This clearly indicates that TnpA1 creates staggered breaks at the inverted repeats of ISDha1 that are filled up to a 6-bp intervening sequence upon the rejoining of the IR ends in the circular intermediates. This observation allowed us to distinguish between TnpA1-mediated transposition (as in forms B, C, and H) (Fig. 5) and the illegitimate recombination likely to occur across the direct repeats between forms E and G (Fig. 5). No unique TnpA1 cleavage pattern in IR regions could be derived from the results obtained here. However, a detailed evaluation of all possible cleavage patterns (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) suggested one common cleavage mode, at 5′-NG↓ATAGA-3′ within the upper strand and 3′-N↑CTATCT-5′ in the lower strand of the left IR (IRL) (underlined) and at 5′-ACTATCNNNNN↓N-3′ in the upper strand of the right IR and 3′-TGATAGNNNNNN↑N-5′ (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). This cleavage pattern reasonably fits with the contrasting data obtained previously for IS256, where Prudhomme and coworkers identified a rather oriented attack of the IRL on the IRR (19), while both IRs have been shown to attack a few base pairs outside the opposite IR (10). In ISDha1, however, a 6-bp intervening sequence was systematically observed upon transposition, while a variety of lengths has been reported for IS256 (10, 19). Further molecular investigation needs to be done to fully understand the transposition mechanism mediated by TnpA1.

Conclusions.

Our study describes the molecular details of the genetic rearrangements occurring around the pce gene cluster in D. hafniense strain TCE1 in the absence of PCE and highlights the very opportunistic nature of Desulfitobacterium toward the organohalide respiration of PCE, as this capability is rapidly lost when not needed. The drastic elimination of pce genes or the transcription thereof also suggests that these isolates have not yet fully evolved toward a dedicated metabolism of organohalide respiration and that Desulfitobacterium isolates harboring the pce transposon could have acquired it by horizontal gene transfer from obligate OHR bacteria such as Dehalobacter restrictus.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A.D. was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation grants 3100A0-108197 and 3100A0-120627.

We declare that we have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 22 June 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ehrlich SD, et al. 1993. Mechanisms of illegitimate recombination. Gene 135: 161–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Futagami T, Goto M, Furukawa K. 2008. Biochemical and genetic bases of dehalorespiration. Chem. Rec. 8: 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Futagami T, Tsuboi Y, Suyama A, Goto M, Furukawa K. 2006. Emergence of two types of nondechlorinating variants in the tetrachloroethene-halorespiring Desulfitobacterium sp. strain Y51. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 70: 720–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Futagami T, Yamaguchi T, Nakayama S, Goto M, Furukawa K. 2006. Effects of chloromethanes on growth of and deletion of the pce gene cluster in dehalorespiring Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain Y51. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72: 5998–6003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gerritse J, et al. 1999. Influence of different electron donors and acceptors on dehalorespiration of tetrachloroethene by Desulfitobacterium frappieri TCE1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65: 5212–5221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hennig S, Ziebuhr W. 2008. A transposase-independent mechanism gives rise to precise excision of IS256 from insertion sites in Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Bacteriol. 190: 1488–1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holliger C, Regeard C, Diekert G. 2003. Dehalogenation by anaerobic bacteria, p 115–157 In Häggblom MM, Bossert IB. (ed), Dehalogenation: microbial processes and environmental applications. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- 8. John M, et al. 2009. Retentive memory of bacteria: long-term regulation of dehalorespiration in Sulfurospirillum multivorans. J. Bacteriol. 191: 1650–1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim SH, et al. 2012. Genome sequence of Desulfitobacterium hafniense DCB-2, a Gram-positive anaerobe capable of dehalogenation and metal reduction. BMC Microbiol. 12: 21 doi:10.1186/1471-2180-12-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Loessner I, Dietrich K, Dittrich D, Hacker J, Ziebuhr W. 2002. Transposase-dependent formation of circular IS256 derivatives in Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 184: 4709–4714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maillard J, Genevaux P, Holliger C. 2011. Redundancy and specificity of multiple trigger factor chaperones in Desulfitobacteria. Microbiology 157: 2410–2421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maillard J, Regeard C, Holliger C. 2005. Isolation and characterization of Tn-Dha1, a transposon containing the tetrachloroethene reductive dehalogenase of Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain TCE1. Environ. Microbiol. 7: 107–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maphosa F, de Vos WM, Smidt H. 2010. Exploiting the ecogenomics toolbox for environmental diagnostics of organohalide-respiring bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 28: 308–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marzorati M, et al. 2007. A novel reductive dehalogenase, identified in a contaminated groundwater enrichment culture and in Desulfitobacterium dichloroeliminans strain DCA1, is linked to dehalogenation of 1,2-dichloroethane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73: 2990–2999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McMurdie PJ, et al. 2009. Localized plasticity in the streamlined genomes of vinyl chloride respiring Dehalococcoides. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000714 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Neumann A, Wohlfarth G, Diekert G. 1998. Tetrachloroethene dehalogenase from Dehalospirillum multivorans: cloning, sequencing of the encoding genes, and expression of the pceA gene in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 180: 4140–4145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Platt AR, Woodhall RW, George AL., Jr 2007. Improved DNA sequencing quality and efficiency using an optimized fast cycle sequencing protocol. Biotechniques 43: 58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prat L, Maillard J, Grimaud R, Holliger C. 2011. Physiological adaptation of Desulfitobacterium hafniense strain TCE1 to tetrachloroethene respiration. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77: 3853–3859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prudhomme M, Turlan C, Claverys JP, Chandler M. 2002. Diversity of Tn4001 transposition products: the flanking IS256 elements can form tandem dimers and IS circles. J. Bacteriol. 184: 433–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Regeard C, Maillard J, Dufraigne C, Deschavanne P, Holliger C. 2005. Indications for acquisition of reductive dehalogenase genes through horizontal gene transfer by Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71: 2955–2961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sargent F. 2007. The twin-arginine transport system: moving folded proteins across membranes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35: 835–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Seshadri R, et al. 2005. Genome sequence of the PCE-dechlorinating bacterium Dehalococcoides ethenogenes. Science 307: 105–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Siguier P, Perochon J, Lestrade L, Mahillon J, Chandler M. 2006. ISfinder: the reference centre for bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 34: D32–D36 doi:10.1093/nar/gkj014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Walker JM. 1988. New protein techniques, vol 3. Humana Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zinser ER, Schneider D, Blot M, Kolter R. 2003. Bacterial evolution through the selective loss of beneficial genes. Trade-offs in expression involving two loci. Genetics 164: 1271–1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.