Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

The aim of this study was to compare female sexual function after surgical treatment of anterior vaginal prolapse with either small intestine submucosa grafting or traditional colporrhaphy.

METHODS:

Subjects were randomly assigned, preoperatively, to the small intestine submucosa graft (n = 29) or traditional colporrhaphy (n = 27) treatment group. Postoperative outcomes were analyzed at 12 months. The Female Sexual Function Index questionnaire was used to assess sexual function. Data were compared with independent samples or a paired Student's t-test. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT00827528.

RESULTS:

In the small intestine submucosa group, the total mean Female Sexual Function Index score increased from 15.5±7.2 to 24.4±7.5 (p<0.001). In the traditional colporrhaphy group, the total mean Female Sexual Function Index score increased from 15.3±6.8 to 24.2±7.0 (p<0.001). Improvements were noted in the domains of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. There were no differences between the two groups at the 12-month follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS:

Small intestine submucosa repair and traditional colporrhaphy both improved sexual function postoperatively. However, no differences were observed between the two techniques.

Keywords: Sexual Function, Pelvic Organ Prolapse, SIS Graft

INTRODUCTION

Female Sexual Dysfunction (FSD) is multifactorial and involves physical, social, and psychological dimensions. FSD is defined as disorders of desire, arousal, orgasm, or pain that could cause emotional distress (1). Earlier studies have shown that this problem affects 39-53% of women in the general population (2-4). Women with pelvic floor disorders (PFDs), such as pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and stress urinary incontinence (SUI), commonly have problems related to sexual function (5-7).

More than 225,000 surgical procedures are performed for POP each year in the USA, and the estimated cost of these surgeries is over US $1 billion (8-10). The lifetime risk of prolapse surgery has been estimated to be approximately 11%, and 30% of patients undergo re-operation for recurrent prolapse (11). In the USA, approximately 150,000 surgeries are performed every year for cystocele and/or rectocele repairs (10,12). The anterior compartment is the most common site of recurrence, with failure rates as high as 40% (12).

Despite anatomical and functional improvements, Pauls et al. (13) showed that sexual function was unchanged after vaginal reconstructive surgery. They concluded that the lack of benefit may be attributable to postoperative dyspareunia. This is a controversial issue, as some authors have shown improvements (14,15) and others have not (16).

Despite the widespread use of mesh in surgery to correct prolapse, few safety and efficacy studies have been published. Therefore, the use of mesh during vaginal repair procedures remains controversial. Uncontrolled studies have reported significant problems associated with the use of mesh for vaginal repair (17). Previous studies are difficult to assess and compare for several reasons, namely the inconsistent use of primarily unvalidated, self-made questionnaires; the lack of a definition for sexual function and dysfunction; and the failure to assess impacts on quality of life (18).

The aim of this study was to assess sexual function using a validated sexual function questionnaire administered following vaginal surgery for anterior vaginal wall prolapse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We included pre- and post-menopausal women who were referred for vaginal surgery and who had at least stage II anterior vaginal wall prolapse (point Ba≥+1). Patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups: SIS graft or traditional anterior colporrhaphy.

Subjects were excluded if they had undergone pelvic radiotherapy or if they had pelvic sepsis, gynecologic cancer, vulvovaginal infections, a current history of smoking or alcoholism, any chronic disabling diseases, or hypertension.

All patients underwent a standard physical examination that included pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) (19). The examination included POP-Q in the gynecological position with an empty bladder. A Valsalva maneuver or cough demonstrated the maximum descent of the involved pelvic organ.

Preoperatively and at 12 months postoperatively, patients were asked to complete the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire (20), which was translated to Portuguese and validated for Brazilian women (21,22). The FSFI is used to investigate problems with sexual function in the previous four weeks. The FSFI is a comprehensive, 19-item tool that assesses six domains of sexual function, namely desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. The questionnaire provides a comprehensive assessment of baseline and postoperative changes. To calculate each domain score, the scores of the related items are added, and the result is multiplied by a coefficient. Within the domains, a score of zero indicates that the patient reported no sexual intercourse in the previous four weeks. Consequently, the maximum domain score is 6, and the lowest score is 0 for four domains and 0.8 and 1.2, respectively, for two domains. The total FSFI score is calculated by adding the mean scores of all six domains. Higher scores indicate better sexual function. Total FSFI scores range from a low of 2 to a high of 36. The FSFI is self-administered.

Multichannel urodynamics were performed on subjects who had urinary incontinence prior to the surgery. We used clinical patterns to evaluate menopausal status; namely, women who reported current and regular periods were defined as premenopausal, while women who reported more than 12 months of amenorrhea were defined as postmenopausal. We used methods and definitions from the International Continence Society subcommittee for the standardization of terminology (23).

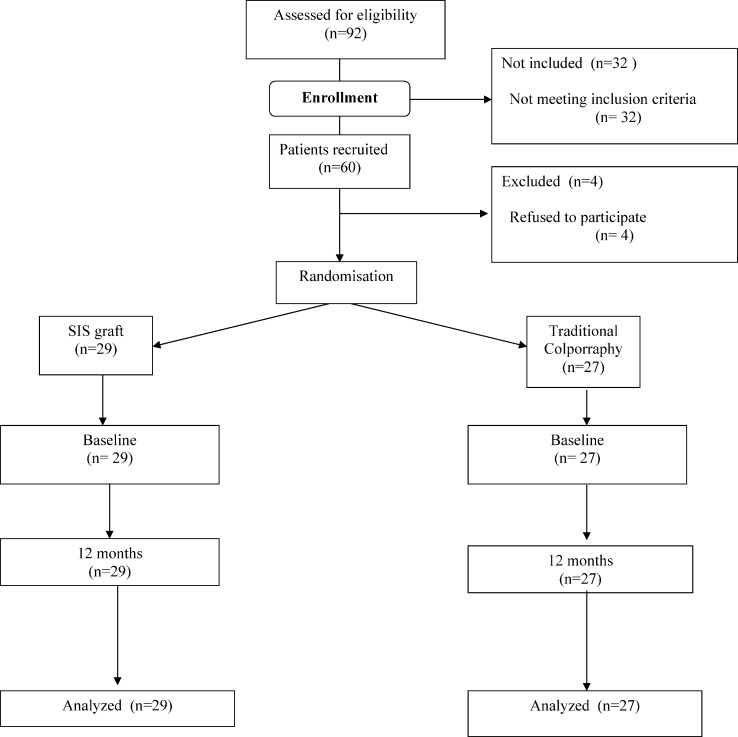

Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the progression of patients through the study. All eligible women who agreed to participate in the study and who provided written informed consent were enrolled. After they were enrolled by a physician investigator, subjects were assigned to the two treatment groups: SIS and traditional repair. One week before surgery, individuals were randomized by a computer-generated list that was prepared by the Biostatistics Center at the Federal University of São Paulo. The list was centrally maintained. There were no drop-outs in the follow-up, and the data were analyzed with an intention-to-treat analysis. The preoperative assessments were conducted by one investigator. After the surgery, the examiners were blinded to the surgical intervention that each subject received. The postoperative follow-ups were performed by three investigators who were also blinded to the group assignments.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient progression through the study.

This study was a prospective and randomized study that was approved by a local ethics committee and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00827528). The primary outcome was the anatomical success of the surgery, which was defined as the absence, at the 12-month follow-up, of POP-Q stage II or higher prolapse (point Ba). The secondary objective was to measure quality-of-life outcomes and sexual function. The two surgical techniques, the outcomes regarding anatomical cure, the P-QoL questionnaire and the complications have been previously reported (24). Similar to Pauls' (13) retrospective analysis, a sample size of 18 women in each group was chosen to detect a difference of 5 points in the FSFI score with 90% power.

All numerical data were expressed as the means±standard deviations. To detect preoperative intergroup differences, we used a Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and a chi-square test for categorical variables. Data were normally distributed, which enabled the use of an independent samples t-test to assess the postoperative difference between the two groups and a paired Student's t-test to assess the same group before and after the surgery. The level of significance was 0.05.

RESULTS

Preoperatively, the groups were homogeneous with respect to age, body mass index, parity, hormonal status, stage of anterior prolapse, previous surgery for prolapse, previous stress urinary incontinence and previous hysterectomy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline data. Values are presented as the means (±standard deviation) or the number of subjects (n).

| SIS (n = 29) | Traditional repair (n = 27) | p-value | |

| Age (y) | 53.8±9.7 | 56.3±13.0 | 0.42 |

| Parity | 4.3±1.8 | 4.0±2.1 | 0.68 |

| Body mass index | 27.3±4.9 | 27.5±4.5 | 0.89 |

| Hormonal status | |||

| Postmenopausal | 19 (65.5%) | 13 (48.2%) | |

| Premenopausal | 10 (34.5%) | 14 (51.8%) | 0.44 |

| POP-Q Stage | |||

| II | 9 (31.0%) | 13 (48.2%) | |

| III | 19 (65.5%) | 12 (44.4%) | |

| IV | 1 (3.5%) | 2 (7.4%) | 0.27 |

| Prior POP surgery | 7 (24.1%) | 7 (25.9%) | 0.87 |

| Prior SUI surgery | 5 (17.2%) | 3 (11.1%) | 0.78 |

| Prior hysterectomy | 3 (10.3%) | 1 (3.7%) | 0.65 |

POP-Q: pelvic organ prolapse quantification.

SUI: stress urinary incontinence.

Scores in the FSFI domains were also homogeneous preoperatively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Preoperative and postoperative FSFI scores of women who underwent SIS grafting or traditional anterior repair. Values are given as the means (± standard deviation).

| SIS graft | Traditional repair | p-value*) | |

| Desire | |||

| Pre-op | 2.5±1.2 | 2.6±1.1 | 0.38 |

| Post-op | 4.1±1.5 | 3.9±1.6 | 0.65 |

| p-value**) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Arousal | |||

| Pre-op | 2.7±0.9 | 2.8±0.7 | 0.48 |

| Post-op | 4.3±1.1 | 4.2±1.0 | 0.67 |

| p-value**) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Lubrication | |||

| Pre-op | 2.8±0.8 | 2.8±1.0 | 0.35 |

| Post-op | 4.1±1.0 | 4.2±1.0 | 0.88 |

| p-value**) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Orgasm | |||

| Pre-op | 2.3±1.2 | 2.2±1.1 | 0.55 |

| Post-op | 4.0±0.9 | 4.1±1.0 | 0.74 |

| p-value**) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Satisfaction | |||

| Pre-op | 2.1±0.9 | 2.0±0.8 | 0.25 |

| Post-op | 4.0±1.0 | 4.0±1.0 | 0.92 |

| p-value**) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Pain | |||

| Pre-op | 3.1±1.1 | 2.9±1.0 | 0.90 |

| Post-op | 3.9±1.1 | 3.8±1.2 | 0.85 |

| p-value**) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Total | |||

| Pre-op | 15.5±7.2 | 15.3±6.8 | 0.76 |

| Post-op | 24.4±7.5 | 24.2±7.0 | 0.65 |

| p-value**) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Independent samples t-test.

Paired Student's t-test.

There were 23 (79.3%) sexually active patients in the SIS group and 22 (81.4%) in the TC group. All of the patients were in heterosexual relationships.

At the 12-month follow-up, both groups had significantly improved sexual quality of life. In the SIS group, the total mean FSFI score increased from 15.5±7.2 to 24.9±7.5 (p<0.001). In the TC group, the total mean FSFI score increased from 15.3±6.8 to 24.2±7.0 (p<0.001). Statistically significant improvements were noted in all domains, including desire, arousal, vaginal lubrication, ability to achieve orgasm, sexual satisfaction, and pain. However, there were no differences between the groups (Table 2).

Women were also questioned, preoperatively and at 12 months, about dyspareunia. At the 12-month follow-up, 5 of the 29 (17.2%) patients in the SIS group and 4 of the 27 (14.8%) patients in the traditional repair group reported dyspareunia (p = 0.90). There were no infections or graft erosions that could have caused the dyspareunia.

DISCUSSION

FSD has become a popular research area because of its importance to quality of life. However, the routine identification of FSD is still lacking (25). Surgery for prolapse and urinary incontinence does not necessarily ensure optimal sexual function, and conflicting results have been reported (13-16).

Using the FSFI at 12 months after the operation, our results showed that SIS graft repair and traditional colphorraphy resulted in improvements in sexual quality of life; however, no differences were observed between the two techniques.

There are few studies on the sexual outcomes of anterior colporrhaphy compared with graft-augmented repair. Some authors have agreed that cystocele repair is not associated with dyspareunia or impaired sexual function, but this issue is controversial in the literature (26).

Anterior repair appears to have a negative effect on sexual function only when it is combined with another procedure. Colombo et al. assessed 23 women who had an anterior repair and found that 56% had mild-to-severe postoperative dyspareunia; however, the patients also had a posterior repair and perineorrhaphy (26,27).

Data from one trial suggested a reduction in dyspareunia, from 30% preoperatively to 22% postoperatively, in a comparison of three surgical techniques of anterior colporrhaphy (28). Another trial compared anterior colporrhaphy with and without porcine dermis inlay (Pelvicol). At the one-year follow-up, there were no differences in dyspareunia between the groups (29).

Graft anterior repair exposure has ranged from 0 to 30%; however, the data regarding dyspareunia and sexual dysfunction are insufficient (17). Jia et al. reported that 7.1-12.8% of patients had de novo dyspareunia after surgical repair of POP using graft augmentation (30). Foon et al. (31) concluded that erosions and dyspareunia were common adverse events in the surgical treatment of anterior vaginal wall prolapse with adjuvant materials.

In a cross-sectional study using the FSFI questionnaire, Najafabady et al. (32) assessed the prevalence and associated factors of anorgasmia among 1,200 reproductive-age Iranian women. Compared with the normal orgasm group, the authors found that 26.3% of the anorgasmic and most of the anorgasmic women were highly unsatisfied with their sexual relationship.

There were several limitations to the present study. The study was initially intended for a 12-month follow-up. A longer follow-up could potentially identify changes in sexual function and could demonstrate a possible degradation of SIS, which has been noted in previous SIS slings used for stress urinary incontinence. The sample size was calculated based on the primary objective of achieving an anatomical cure. The sample size may have been inadequate to detect small differences between the groups, and the power calculation was suboptimal, especially for the FSFI scores.

Although the surgical procedure was standardized, there may have been variations in the surgical technique that was employed by different surgeons. However, this would more closely represent expected outcomes in actual clinical practice compared with trials employing only one surgeon.

Another important matter is that the FSFI questionnaire that was utilized to assess the sexual function in women with PFDs has some limitations. The FSFI questionnaire is not specifically designed to assess changes in sexual health that are caused by PFDs. Therefore, it may not be sensitive to meaningful changes in sexual function in our population. Additionally, the questionnaires do not screen for sexual activity, which may underestimate the impact of PFDs on sexual function, as women with severe dysfunction may elect to become sexually inactive (18).

Rigorous RCTs are required to determine the comparative efficacy of grafts and their optimal place in clinical practice. Functional results are important as outcome measures of anatomical results in the assessment of pelvic floor surgery. Following pelvic floor surgery, sexual function assessment tools are needed to define clear outcomes for sexual function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Handle Cook for providing the SIS grafts.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, Derogatis L, Ferguson D, Fourcroy J, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: Definitions and classifications. J Urology. 2000;163(3):888–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mercer CH, Fenton KA, Johnson AM, Wellings K, Macdowall W, McManus S, et al. Sexual function problems and help seeking behaviour in Britain: national probability sample survey. Brit Med J. 2003;327(7412):426–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7412.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolosi A, Laumann EO, Glasser DB, Moreira ED, Paik A, Gingell C, et al. Sexual behavior and sexual dysfunctions after age 40: The global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Urology. 2004;64(5):991–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pauls RN, Segal JL, Silva WA, Kleeman SD, Karram MM. Sexual function in patients presenting to a urogynecology practice. Int Urogynecol J. 2006;17(6):576–80. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wehbe SA, Kellogg S, Whitmore K. Urogenital Complaints and Female Sexual Dysfunction (Part 2) (CME) J Sex Med. 2010;7(7):2305–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barber MD, Visco AG, Wyman JF, Fantl JA, Bump RG, Res CPW. Sexual function in women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(2):281–9. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01727-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salonia A, Zanni G, Nappi RE, Briganti A, Deho F, Fabbri F, et al. Sexual dysfunction is common in women with lower urinary tract symptoms and urinary incontinence: Results of a cross-sectional study. Eur Urol. 2004;45(5):642–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyles SH, Weber AM, Meyn L. Procedures for pelvic organ prolapse in the United States, 1979-1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(1):108–15. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Subak LL, Waetjen LE, van den Eeden S, Thom DH, Vittinghoff E, Brown JS. Cost of pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(4):646–51. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01472-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JS, Waetjen LE, Subak LL, Thom DH, Van Den Eeden S, Vittinghoff E. Pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States, 1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(4):712–6. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501–6. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyles SH, Edwards SR. Repair of the anterior vaginal compartment. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;48(3):682–90. doi: 10.1097/01.grf.0000171739.27555.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pauls RN, Silva WA, Rooney CM, Siddighi S, Kleeman SD, Dryfhout V, et al. Sexual function after vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(6):622 e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghezzi F, Serati M, Cromi A, Uccella S, Triacca P, Bolis P. Impact of tension-free vaginal tape on sexual function: results of a prospective study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17(1):54–9. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber AM, Walters MD, Piedmonte MR. Sexual function and vaginal anatomy in women before and after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182(6):1610–5. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.107436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helstrom L, Nilsson B. Impact of vaginal surgery on sexuality and quality of life in women with urinary incontinence or genital descensus. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica. 2005;84(1):79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maher C, Baessler K, Glazener CMA, Adams EJ, Hagen S. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women: A short version Cochrane review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2008;27(1):3–12. doi: 10.1002/nau.20542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pons ME. Sexual health in women with pelvic floor disorders: measuring the sexual activity and function with questionnaires-a summary. Int Urogynecol J. 2009;20:S65–S71. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0828-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bo K, Brubaker LP, DeLancey JOL, Klarskov P, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(1):10–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiel Rdo R, Dambros M, Palma PC, Thiel M, Riccetto CL, Ramos Mde F. [Translation into Portuguese, cross-national adaptation and validation of the Female Sexual Function Index] Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2008;30(10):504–10. doi: 10.1590/s0100-72032008001000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hentschel H, Alberton DL, Capp E, Goldim JR, Passos EP. Validação do Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) para uso em português. Rev HCPA. 2007;27(1):10–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haylen BT, de Ridder D, Freeman RM, Swift SE, Berghmans B, Lee J, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(1):5–26. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-0976-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feldner PC, Castro RA, Cipolotti LA, Delroy CA, Sartori MGF, Girao MJBC. Anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial of SIS graft versus traditional colporrhaphy. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(9):1057–63. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bekker M, Beck J, Putter H, van Driel M, Pelger R, Nijeholt ALA, et al. The Place of Female Sexual Dysfunction in the Urological Practice: Results of a Dutch Survey. J Sex Med. 2009;6(11):2979–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Achtari C, Dwyer PL. Sexual function and pelvic floor disorders. Best Pract Res Cl Ob. 2005;19(6):993–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colombo M, Vitobello D, Proietti F, Milani R. Randomised comparison of Burch colposuspension versus anterior colporrhaphy in women with stress urinary incontinence and anterior vaginal wall prolapse. Brit J Obstet Gynaec. 2000;107(4):544–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber AM, Walters MD, Piedmonte MR, Ballard LA. Anterior colporrhaphy: A randomized trial of three surgical techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185(6):1299–304. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.119081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meschia M, Pifarotti P, Bernasconi F, Magatti F, Riva D, Kocjancic E. Porcine skin collagen implants to prevent anterior vaginal wall prolapse recurrence: A multicenter, randomized study. J Urology. 2007;177(1):192–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia X, Glazener C, Mowatt G, MacLennan G, Bain C, Fraser C, et al. Efficacy and safety of using mesh or grafts in surgery for anterior and/or posterior vaginal wall prolapse: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bjog-Int J Obstet Gy. 2008;115(11):1350–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foon R, Toozs-Hobson P, Latthe PM. Adjuvant materials in anterior vaginal wall prolapse surgery: a systematic review of effectiveness and complications. Int Urogynecol J. 2008;19(12):1697–706. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0668-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Najafabady MT, Salmani Z, Abedi P. Prevalence and related factors for anorgasmia among reproductive aged women in Hesarak, Iran. Clinics. 2011;66(1):83–6. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000100015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]