INTRODUCTION

Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) syndrome accounts for 10%–20% of the cases of ACTH-dependent Cushing's syndrome (1). Ectopic ACTH secretion typically results from an occult, slow-growing bronchial carcinoid tumor. The diagnosis of these relatively small tumors can be difficult with conventional imaging procedures, such as computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (2). Herein, we present a case of ectopic ACTH syndrome arising from a bronchial carcinoid tumor that was diagnosed with somatostatin receptor scintigraphy (SRS).

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 25-year-old Caucasian woman was admitted for oligomenorrhea and hirsutism. A physical examination revealed central obesity, a “buffalo hump”, acne, and severe hirsutism (Ferriman-Gallwey score of 18). After overnight dexamethasone suppression testing (DST), her serum cortisol level was 14.4 µg/dL. She was hospitalized with a presumptive diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome.

Her diurnal cortisol secretion rhythm was found to be impaired; her serum cortisol level at midnight was 27.1 µg/dL. Low-dose DST was also consistent with this diagnosis, with an unsuppressed serum cortisol level of 4.2 µg/dL. Her basal ACTH and cortisol levels were 67 pg/mL and 15.2 µg/dL, respectively.

With a refined presumptive diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing's syndrome, we performed overnight high-dose DST with 8 mg dexamethasone. Her serum cortisol level was 10 µg/dL, revealing a lack of suppression. An MRI revealed a 3-mm microadenoma of the hypophysis. However, inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS) revealed no substantial gradient in ACTH levels between the center and the periphery (Table 1). Thus, a diagnosis of ectopic Cushing's syndrome was proposed.

Table 1.

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) levels in the inferior petrosal sinus before and after the infusion of corticotropin-releasing hormone.

| ACTH Level (pg/mL) | |||

| Periphery | Right | Left | |

| Time before infusion | |||

| 5 minutes | 141 | 163 | 151 |

| 2 minutes | 144 | 159 | 164 |

| Time after infusion | |||

| 2 minutes | 148 | 160 | 151 |

| 5 minutes | 149 | 166 | 181 |

| 10 minutes | 160 | 175 | 172 |

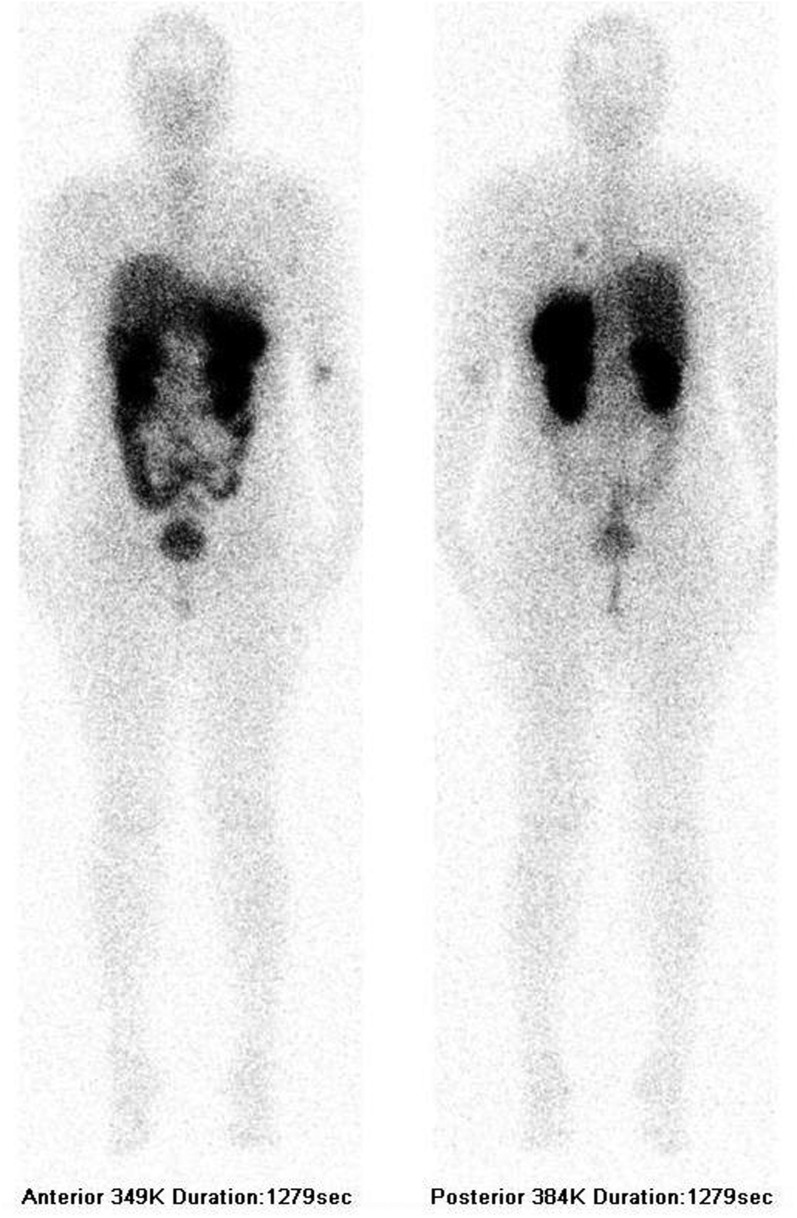

Upon CT of the thorax and abdomen, we noted a contrast-enhancing small lesion at the left posterobasal segment (Figure 1). No involvement was present upon positron emission tomography (PET). SRS revealed a lesion at the left posterobasal segment consistent with the thorax CT, suggesting a bronchial carcinoid tumor (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Computerized tomography of the bronchial carcinoid.

Figure 2.

Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy of the bronchial carcinoid.

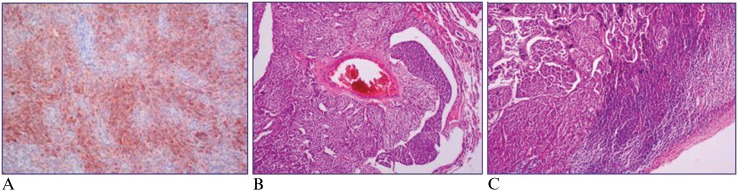

The patient underwent segmentectomy. An immunohistochemical evaluation revealed positive staining for chromogranin, synaptophysin, and ACTH (Figure 3). Two weeks after surgery, cortisol was suppressed upon low-dose DST (serum cortisol level, 0.2 µg/dL). After four months of follow up, she had lost 15 kg, her menstrual periods had become regular, and her acne and hirsutism had regressed significantly.

Figure 3.

A) ACTH staining of bronchial cells. B) Vascular invasion by tumor cells. C) Lymphoid invasion by tumor cells.

DISCUSSION

Ectopic ACTH syndrome represents a minority of all cases of Cushing's syndrome (1,2). High-dose DST can be used to discriminate ectopic ACTH syndrome from classic Cushing's disease; a suppression of more than 50% of the basal cortisol level can be observed in more than 80% of patients with Cushing's disease (3). However, the diagnostic utility of high-dose DST is limited, and this test is not recommended when IPSS is available (3). In our patient, although cortisol suppression could be compatible with a diagnosis of ectopic ACTH syndrome, she also had a microadenoma in the hypophysis. Because adenomas are incidentally discovered in up to 10% of the normal population, IPSS is advised for patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing's syndrome and a hypophyseal adenoma smaller than 6 mm, particularly when test results conflict (4).

IPSS can demonstrate the ratio of the ACTH level in the central sinus relative to the peripheral sinus. A central/peripheral ratio of 2 before the administration of corticotropin-releasing hormone and a ratio of ≥3 after its administration strongly suggests Cushing's disease (5). However, although a positive result is highly suggestive of Cushing's disease, false-negative results might be more common than previously appreciated (2%–4%). In cases of a negative response, clinicians should perform a careful search for an ectopic source (6). In our patient, although she had a pituitary microadenoma (3 mm), the results of high-dose DST and IPSS were consistent with ectopic ACTH syndrome.

The source of ectopic ACTH secretion should be established after diagnosis because the excision of an ACTH-producing tumor can be curative (2,7). The most likely site of ACTH-producing tumors is the thorax, and these tumors are frequently bronchial carcinoid tumors. Locating these tumors can be challenging; they are relatively small and slow-growing, and conventional imaging studies, such as CT and MRI, identify the tumor in only 50% of cases (2,4,7). The tumor can remain occult long after the diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome (4).

Functional imaging studies, such as PET and SRS, are complementary imaging tools for revealing the presence of carcinoids (6). SRS might be superior to PET in detecting bronchial carcinoids. Although PET can detect highly active proliferative tumors, bronchial carcinoids usually have a low proliferation index and are slow growing, quite small lesions (7,8). However, the success of SRS depends only on the presence of somatostatin receptors, which have been identified on many cells of neuroendocrine origin (8). The radiolabelled somatostatin analog octreotide can bind to somatostatin receptors 2 and 5 with high affinity (8). Bronchial carcinoids express both receptors. Nevertheless, these tumors may show heterogeneity in the degree of somatostatin receptor expression (8).

The diagnostic sensitivity of SRS is approximately 25%–73% for the detection of an ectopic source of ACTH secretion (9). Ilias and colleagues reported that the sensitivity of SRS is only approximately 49%, and it is insufficient for lesions that are not present on CT or MRI (1). Zemskova and colleagues reported a 57% sensitivity and a 79% positive predictive value for SRS for detecting ectopic ACTH-producing tumors (7).

The use of a single imaging tool may not be sufficient to diagnose ectopic ACTH-secreting tumors; conventional and functional imaging studies should be used in combination when needed (2),. In our case, the ectopic lesion was shown on CT but not on PET. SRS confirmed the lesion shown on CT, and the tumor was extracted. Suppression by DST revealed biochemical recruitment, and ACTH staining of the excised tissue confirmed the ectopic tumor postoperatively.

In conclusion, in cases of ectopic ACTH syndrome, the exact location of the lesion is needed for a curative approach. Conventional imaging studies may not always show the lesion. The use of somatostatin receptor scintigraphy in addition to conventional imaging may help localize lesions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

English language editing of this manuscript was performed by Patricia French from Left Lane Communications (Chapel Hill, NC, USA) and funded by Sanofi-Aventis (İstanbul, Turkey).

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ilias I, Torpy DJ, Pacak K, Mullen N, Wesley RA, Nieman LK. Cushing's syndrome due to ectopic corticotropin secretion: twenty years' experience at the National Institutes of Health. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4955–62. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tani Y, Sugiyama T, Hirooka S, Izumiyama H, Hirata Y. Ectopic ACTH syndrome caused by bronchial carcinoid tumor indistinguishable from Cushing's disease. Endocr J. 2010;57(8):679–86. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k10e-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Newell-Price J, Grossman AB. Differential diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;51(8):1199–206. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302007000800005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boscaro M, Arnaldi G. Approach to the patient with possible Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(9):3121–31. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lad SP, Patil CG, Laws ER, Jr, Katznelson L. The role of inferior petrosal sinus sampling in the diagnostic localization of Cushing's disease. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23:E2. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.23.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isidori AM, Lenzi A. Ectopic ACTH syndrome. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;51(8):1217–25. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302007000800007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zemskova MS, Gundabolu B, Sinaii N, Chen CC, Carrasquillo JA, Whatley M, Chowdhury I, Gharib AM, Nieman LK. Utility of various functional and anatomic imaging modalities for detection of ectopic adrenocorticotropin-secreting tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(3):1207–19. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pacak K, Ilias I, Chen CC, Carrasquillo JA, Whatley M, Nieman LK. The role of [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and [(111)In]-diethylenetriaminepentaacetate-D-Phe-pentetreotide scintigraphy in the localization of ectopic adrenocorticotropin-secreting tumors causing Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(5):2214–21. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doi M, Sugiyama T, Izumiyama H, Yoshimoto T, Hirata Y. Clinical features and management of ectopic ACTH syndrome at a single institute in Japan. Endocr J. 2010;57(12):1061–9. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k10e-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]