Abstract

Large oro-facial defects consequences in serious functional as well as cosmetic deformities. Acceptable cosmetic results usually can be obtained with a facial prosthesis. This article describes prosthetic rehabilitation of a 35 year-old female having a left orbital defect with HTV silicone material. A modified technique to fabricate an acrylic substructure in heat-polymerizing polymethyl-methacrylate to support silicone facial prosthesis was illustrated. The resultant facial prosthesis was structurally durable and esthetically acceptable with satisfactory retention. This technique is advantageous as there is no need to fabricate the whole prosthesis again in case of damage of the silicone layer because the outer silicone layer can be removed and repacked on the substructure if the gypsum-mold is preserved.

Introduction

Loss of tissue, whether congenital or traumatic or resulting from malignancy or Radical surgery is accompanied by aesthetic and psychological effects. This loss is more pronounced when the affected part is the eye and all orbital contents, resulting in gross mutilation [1].

Replacement of the lost eye as soon as possible after healing from eye removal is necessary to promote physical and psychological healing for the patient and to improve social acceptance. Fabrication of an extraoral facial prosthesis challenges the artistic ability of the prosthodontist. A multidisciplinary management and team approach are essential in providing accurate and effective rehabilitation and follow up care for the patient [6].

This article describes a simplified method for fabrication of a silicone orbital prosthesis.

Case Report

A 35 year old woman reported to the Department of Prosthodontics, Government Dental College and Hospital, Ahmedabad with the chief complaint of facial disfigurement after surgical removal of eye and surrounding structure.

The patient gave history of enucleation of the eye one year back due to fungal infection (mucormycosis). Examination revealed a large, visible, healed surgical defect following surgery (Fig. 1). Also, the patient did not report of any pain or discomfort of the periorbital tissue.

Fig. 1.

Showing healed defect

Due to extensive size of the defect and patient's history of fungal infection, a treatment plan was formulated which consisted of fabrication of a custom silicone orbital prosthesis consisting of inner acrylic portion with an outer portion of silicone [4].

Technique

(1) Fabrication of acrylic portion of prosthesis: An impression of defect was made using heavy body polyvinyl-siloxane impression material. Conventional Prosthodontic protocols of boxing and pouring the impression with type III dental stone (Goldstone; Asian chemicals, Rajkot, Gujarat, India) was used to create a definitive cast. Cast was sectioned in 2 parts and wax pattern was made. This wax pattern was tried on patient and was flasked and processed in heat polymerized clear PMMA (Trevalon clear; Dentsply, New York, PA, USA) using conventional technique [9]. This acrylic portion was finished and polished.

(2) Making a facial moulage: Acrylic part was placed in the defect and impression of rest of the defect was made from irreversible hydrocolloid (Tropicalgin, Zhermack Inc. products, California). Vaseline was applied to eyebrows for easy separation of impression. A thin mix of alginate was applied to the skin with a round-ended mixing spatula in layers. A layer of gauge was placed on setting alginate and the impression is reinforced with fast setting plaster which is around 0.25 inch in thickness to provide adequate support to alginate impression and to avoid tearing and distortion on removal [2, 12, 13].

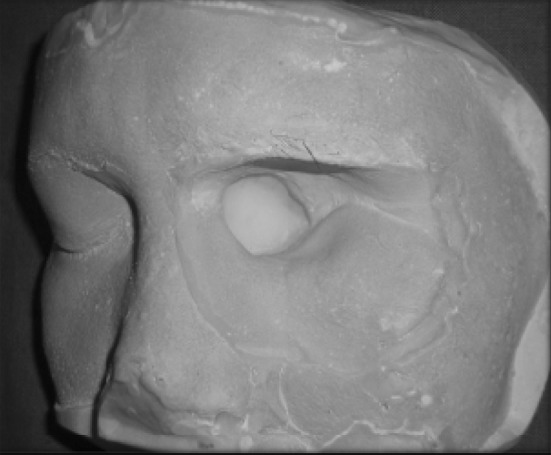

On setting, impression was carefully removed and poured with type III dental stone (Goldstone; Asian chemicals, Rajkot, Gujarat, India) to obtain a facial moulage (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Facial moulage

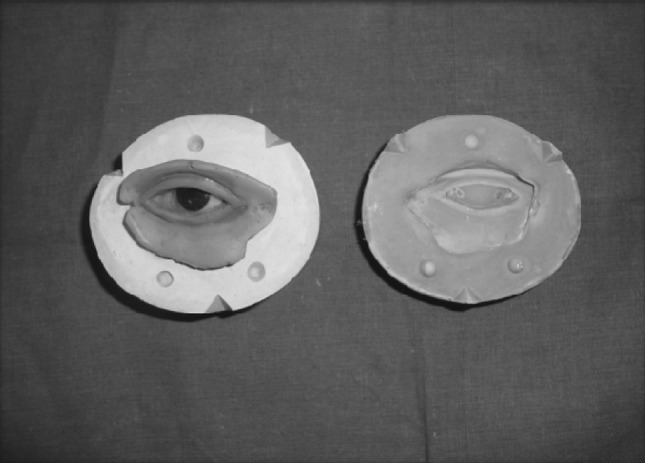

(3) Selection of stock acrylic eye shell: A commercially available stock acrylic eye shell was selected for the patient that closely approximates the colour, size and shape of the iris and sclera of unaffected natural eye [5]. It was modified by trimming and staining to match and resemble natural eye.

(4) Orientation of eye shell and fabrication of wax pattern: The stock ocular prosthesis was placed on the cast and the periphery was arbitrarily trimmed to match socket border extensions on the cast. Next, the ocular prosthesis was positioned to simulate the positioning of the right eye, with the patient focusing on the distant point directly ahead. A reference mark was place at the midline and a boleys gauge was used to verify the mediolateral placement. The pupils were used as reference points for evaluation. Correct mediolateral, antero-posterior and infero-superior positioning and central axis of the prosthesis were confirmed on patient's face [4]. After complete verification some amount of modelling wax was added on the tissue side of the prosthesis and final wax carving and contouring was done to simulate the patient's unaffected eye and surrounding tissues.

(5) Trial of wax pattern (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Wax pattern trial

(6) Dewaxing and investing: After finalizing the pattern, flasking and dewaxing were done in conventional manner [9]. Holes were created in acrylic portion for retention of silicone. The prosthesis was packed with room temperature vulcanizing (RTV) silicone (Cosmosil M 511 series material) and coloured using intrinsic stains selected according to patient's skin colour. The silicone was heated for 2 h at 90 °C in air circulating oven (Oaao Rock health care), deflasked, trimmed and cleaned (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Prosthesis after deflasking and cleaning

(7) Trial of The prosthesis and extrinsic staining: The prosthesis was trial fitted and extrinsically coloured with oil pigments thus completing the fabrication of extraoral section. The gypsum-mould was preserved for future re-packing in case of discoloration or damage of the overlying silicone layer [4].

(8) Finally the prosthesis is finished with the application of eyelash with the help of adhesive (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Final prosthesis

(9) The retention was achieved by engagement of orbital undercut with the acrylic portion. Additional retention was provided by means of eyeglass frame to support and camouflage the prosthesis (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Before and after prosthesis delivery

Discussion

The rehabilitation of the orbital defect is a complex task, and if reconstruction by plastic surgery is not possible or not desired by the patient, the defect can be rehabilitated by an orbital prosthesis, improving the aesthetics and instilling confidence to face the society with dignity.

Various methods of auxiliary retention for orbital prostheses include eyeglasses [3], engagement of hard and soft tissues undercuts [3, 7], magnets [3, 10], adhesives [3], combinations of the above [3, 7, 10], and osseointegrated implants [11]. Although osseointegrated implants may provide the most reliable prosthesis retention; additional surgeries, expenses, inadequate bone, and prior radiation to the area may contraindicate this type of treatment [11].

Several authors have reported different problems that compromise the serviceability of facial prostheses made of a combination of PMMA and silicone. These include degradation of the silicone properties, delamination of silicone from the PMMA base, reduced marginal integrity of the facial prosthesis, resulting in open margins, and poor simulation of facial expressions due to the rigidity and heavy-weight of the PMMA base [8]. This article describes the rehabilitation of an orbital defect with prosthesis, consisting of an acrylic inner portion due to patient's past medical history of fungal infection with a layer of silicone providing aesthetics and flexibility.

This technique is advantageous as there is no need to fabricate the whole prosthesis again in case of discoloration or damage of the silicone layer because the outer silicone layer can be removed and re-packed with the new silicone on the PMMA substructure if the mould is preserved [4].

Summary

The rehabilitation of orbital defect not only resulted in improved aesthetic, function and comfort to the patient but also contributed to physical and mental well being of the patient.

References

- 1.Joneja OP, Madan SK, Mehra MD, Dogra RN. Orbital prosthesis. J Prosthet Dent. 1976;36:306–311. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(76)90188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown KE. Fabrication of orbital prosthesis. J Prosthet Dent. 1969;22:592–607. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(69)90234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor T, editor. Clinical maxillofacial prosthetics. Illinois: Quintessence Publishing; 2000. pp. 233–276. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patil PG. Modified technique to fabricate a hollow light-weight facial prosthesis for lateral midfacial defect: a clinical report. J Adv Prosthodont. 2010;2:65–70. doi: 10.4047/jap.2010.2.3.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinha ND, Bhandari A, Gangadhar SA. Fabrication of custom ocular prosthesis using a graph grid. Pravara Med Rev. 2009;4(1):21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chalian VA, Drane JB, Standish SM. Maxillofacial prosthetics. Multidisciplinary practice. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1971. pp. 294–304. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beumer J, Curtis TA, Marunick MT. Maxillofacial rehabilitation: prosthodontic and surgical considerations. St. Louis: Ishiyaku EuroAmerica; 1996. pp. 377–453. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiat-amnuay S, Lemon JC, Wesley PJ. Technique for fabricating a lightweight, urethane-lined silicone orbital prosthesis. J Prosthet Dent. 2001;86:210–213. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2001.115876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrow RM, Rudd KD, Rhoads JE. Dental laboratory procedures complete dentures. 2. St. Louis: Mosby; 1986. pp. 312–338. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumbrigue HB, Fyler A. Minimizing prosthesis movement in a midfacial defect: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 1997;78:341–345. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(97)70040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arcuri MR, LaVelle WE, Fyler E, Jons R. Prosthetic complications of extraoral implants. J Prosthet Dent. 1993;69:289–292. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(93)90108-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhiman R, et al. Rehabilitation of a rhinocerebral mucormycosis patient. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2007;7:88–91. doi: 10.4103/0972-4052.34003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trakol M, Thomas J, Mark S, James C. A mould-making procedure for multiple orbital prostheses fabrication. J Prosthet Dent. 2003;90:97–100. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(03)00216-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]