Abstract

LigI from Sphingomonas paucimobilis catalyzes the reversible hydrolysis of 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylate (PDC) to 4-oxalomesaconate (OMA) and 4-carboxy-2-hydroxymuconate (CHM) in the degradation of lignin. This protein is a member of the amidohydrolase superfamily of enzymes. The protein was expressed in E. coli and then purified to homogeneity. The purified recombinant enzyme does not contain bound metal ions and the addition of metal chelators or divalent metal ions to the assay mixtures does not affect the rate of product formation. This is the first enzyme from the amidohydrolase superfamily that does not require a divalent metal ion for catalytic activity. The kinetic constants for the hydrolysis of PDC are 340 s−1 and 9.8 × 106 M−1s−1 for the values of kcat, and kcat/Km respectively. The pH dependence on the kinetic constants suggests that a single active site residue must be deprotonated for the hydrolysis of PDC. The site of nucleophilic attack was determined by conducting the hydrolysis of PDC in 18O-labeled water and subsequent 13C NMR analysis. The crystal structures of wild-type LigI and the D248A mutant in the presence of the reaction product were determined to a resolution of 1.9 Å. The C-8 and C-11 carboxylate groups of PDC are coordinated within the active site via ion pair interactions with Arg-130 and Arg-124, respectively. The hydrolytic water molecule is activated by a proton transfer to Asp-248. The carbonyl group of the lactone substrate is activated by electrostatic interactions with His-180, His-31 and His-33.

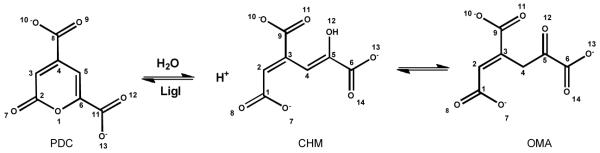

Lignin is the most abundant aromatic biomolecule found in nature. This compound and associated degradation products have implications for the production of biofuels and in the manufacture of adhesives and polyesters (1). The enzyme 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylate lactonase (LigI) plays an important role in the metabolism of lignin-derived aromatic compounds. In the syringate degradation pathway, lignin and tannin-derived compounds containing syringyl moieties are metabolized. Alternatively, lignin-derived compounds containing guaiacyl moieties are metabolized via the protocatechuate 4,5-cleavage pathway (2). LigI catalyzes the reversible hydrolysis of 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylate (PDC) to a mixture of 4-carboxy-2-hydroxymuconate (CHM) and 4-oxalomesaconate (OMA) as shown in Scheme 1 (2-3). Amino acid sequence alignments have identified LigI from Sphingomonas paucimobilis as a member of the amidohydrolase superfamily (AHS).

Scheme 1.

The amidohydrolase superfamily was first identified by Sander and Holm from recognition of the structural and sequence similarities of urease, phosphotriesterase and adenosine deaminase (4). Since the discovery of the AHS, more than 23,000 proteins have been classified as members of this superfamily. Members of this superfamily catalyze a diverse set of chemical reactions including the hydrolysis of amide or ester bonds, deamination of nucleic acids, decarboxylation, isomerization and hydration reactions (5). Proteins in the AHS possess a distorted (β/α)8-TIM barrel structural fold which typically houses an active site containing 1-3 divalent metal ions. The active site metal ions are ligated to the protein through interactions with residues that originate from the C-terminal ends of β-strands that form the core of the β-barrel. The mononuclear metal centers are formed through ligation with a pair of histidine residues in an HxH motif from β-strand 1, a histidine from β-strand 5 and an aspartate from β-strand 8. Proteins with binuclear metal centers coordinate two divalent cations through ligation with the HxH motif from β-strand 1, a carboxylated lysine (or glutamate) from β-strand 3 or 4, two histidine residues from the ends of β-strands 5 and 6 and an aspartate from β-strand 8. The carboxylated lysine functions as a bridge between the two divalent cations.

In contrast, LigI does not appear to be a metalloenzyme. There is no obvious residue that could bridge a binuclear metal center at the C-termini of β-strands 3 or 4. In addition, the conserved histidine found at the C-terminal end of β-strand 5 in nearly all members of the AHS is replaced with a tyrosine in LigI (5). These observations suggest that LigI will have an active site that is significantly different from the structurally characterized members of the amidohydrolase superfamily.

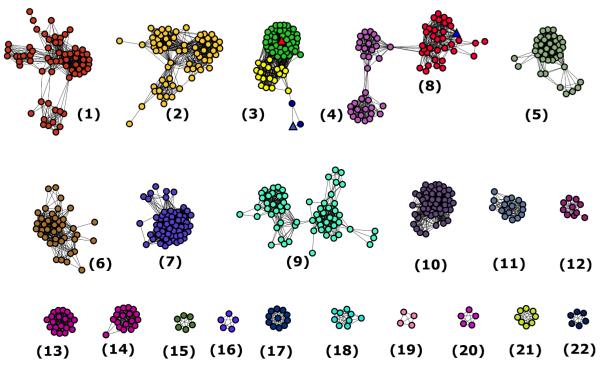

The AHS has been divided into 24 clusters of orthologous groups (COG) by NCBI (6). LigI is one of three partially characterized enzymes within cog3618, along with 4-sulfomuconolactonase (4-SML) and L-rhamnono-1,4-lactonase (7, 8). All three of these enzymes catalyze the hydrolytic cleavage of lactones. A sequence similarity network for cog3618 is presented in Figure 1 (9, 10). The experimentally verified examples of LigI and 4-SML are found in Group 3 of cog3618; these two proteins share ~38% sequence identity. The L-rhamnono-1,4-lactonase is found in Group 8 of cog3618 and shares ~20% sequence identity with LigI.

Figure 1.

Cytoscape generated sequence similarity network of cog3618 at a BLAST E-value cut-off of 10−70. Nodes represent proteins within cog3618 connected to other proteins with an E-value cutoff of less than 10−70 by lines. The stringency value of 10−70 was arbitrarily chosen based on what appears to be the presence of smaller isofunctional groups. The triangle shaped nodes colored red and blue in Group 3 repsresent LigI from S. paucimobilis and 4-SML from A. tumefaciens, respectively. Circular nodes colored green in Group 3 are annotated here as LigI, based on conservation of active site residues of LigI from S. paucimobilis. Nodes colored blue in Group 3 are predicted to be 4-SML enzymes. The yellow nodes in Group 3 are unannotated. The triangle shaped node colored blue in Group 8 is L-rhamnono-1,4-lactonase from Azotobacter vinelandii. The rest of the proteins are of unknown function.

Relatively little is known about the mechanism of action for LigI (2, 11). Previously determined values of kcat for the forward and reverse reactions vary from 110 - 270 s−1. The Km for PDC hydrolysis is ~70 μM and the Michaelis constant for CHM/OMA during lactone synthesis is ~35 μM. Previous published reports suggested that the addition of divalent metal ions to the assays provides either no rate enhancement or is inhibitory (11). Here, we report the crystal structure of LigI in the presence and absence of the product bound in the active site. The catalytic mechanism for the hydrolysis of PDC was elucidated using pH-rate profiles, and active site directed mutants.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Materials

All chemicals and buffers were purchased from Sigma Aldrich unless otherwise specified. The synthesis of 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylate was conducted according to published procedures (2). All buffers, except for Tris-HCl, were titrated to the stated pH with NaOH.

Expression and Purification of LigI from S. paucimobilis

The gene for Sphingomonas paucimobilis LigI (NYSGXRC-10053d, UniProt O87170) was synthesized by back translation and codon optimization for E. coli expression (Codon Devices, Inc.). The gene was cloned into a custom TOPO-isomerase vector, pSGX3(BC), supplied by Invitrogen. The forward primer was ACCAATGATGAACGTATTCTGAGC and the reverse primer was CCATTTCCTCGCTCCAATACAATC. The clone encoded Met-Ser-Leu followed by the PCR product and Glu-Gly-His6. Miniprep DNA was transformed into BL21(DE3)-Codon+RIL expression cells (Stratagene), expressed, and made into a 30% glycerol stock for large-scale fermentation.

The expression clones were cultured using High Yield selenomethionine (SeMet) medium (Orion Enterprises, Inc., Northbrook, IL). 50 mL overnight cultures in 250 mL baffled flasks were grown at 37 °C from a frozen glycerol stock for 16 hours. Overnight cultures were transferred to 2-L baffled shake flasks containing 1 L HY-SeMet medium (100 μg/mL kanamycin and 30 μg/mL chloramphenicol) and grown to OD600 ~ 1.0. SeMet was added for labeling at 90 mg/L, followed by IPTG addition to a final concentration of 0.4 mM. Cells were further grown at 22 °C for 21 hours, then harvested using standard centrifugation for 10 minutes at 39,000 x g and frozen at −80 °C. Non-SeMet-labeled protein was expressed in ZYP autoinduction medium (12).

Cells were lysed in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, 25 mM imidazole, and 0.1% Tween20 by sonication. The cellular debris was removed by centrifugation for 30 minutes (39,800 x g). The supernatant solution was collected and incubated with 10 mL of a 50% slurry of Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) for 30 minutes with gentle stirring. The sample was then poured into a drip column and washed with 50 mL of wash buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 25 mM imidazole) to remove unbound proteins. The protein of interest was eluted using 25 mL of elution buffer (wash buffer with 500 mM imidazole). Protein-containing fractions were pooled and further purified by gel filtration chromatography with a GE Healthcare HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 prep grade column pre-equilibrated with gel filtration buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 5 mM DTT). Fractions containing the protein of interest were combined and concentrated by centrifugation in an Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter unit. The final yield and concentration was 62 mg (8.6 mg/mL) of protein per liter of media. Electrospray mass spectroscopy (ESI-MS) was used to obtain an accurate mass of the purified protein and confirm selenomethionine labeling (34,372 Da with 11 SeMet and no N-terminal methionine). The native, unlabeled protein had a molecular weight of 33,858 Da (lacking the N-terminal methionine). The expression plasmid is available through the PSI Material Repository (dnasu.asu.org) as SpCD00298136 (NYSGXRC clone ID 10053d1BCt7p1). Associated experimental information including the DNA sequence is available in the Protein Expression Purification Crystallization Database (PepcDB.pdb.org) as TargetID “NYSGXRC-10053d”.

Construction of Mutant Enzymes

All single site mutants of LigI were prepared according to the recommendations of the QuikChange PCR procedures manual. Protein expression and purification procedures were performed with slight modifications as described above for wild-type LigI.

Crystallization and Structure Determination

The concentrations of wild-type LigI, D248A, and D248N for crystallization were 17, 15 and 10 mg mL−1 in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, respectively. The substrate, PDC, was added to a concentration of 1.0 mM to each mutant protein prior to crystallization. Diffraction quality crystals were grown using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method by mixing 1 μL of protein and 1 μL of reservoir solution and equilibrating the samples against the corresponding reservoir solution. The compositions of the reservoir solutions were as follows: wild-type LigI - 30% PEG 4000, 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.5, 0.2 magnesium chloride; D248A - 30% PEG 4000, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 0.2 M sodium acetate, or 25% PEG 3350, 0.1 M Bis-Tris, pH 6.5, 0.2 M sodium chloride; D248N - 30% peg4000, 0.1 M sodium-acetate pH 4.6, 0.2 M ammonium acetate.

X-ray Data Collection and Crystallographic Refinement

Crystals of LigI with overall dimensions 0.15 × 0.15 × 0.15 mm3 were mounted in cryo-loops directly from the crystallization droplet and flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. For D248A (pH 6.5) 20% glycerol was added as a cryo-protectant to the droplets before freezing. Diffraction data were collected on a Quantum 315 CCD detector (Area Detector Systems Corporation, Poway, CA) with 1.075 or 0.979 Å wavelength radiation on the X29A beamline (National Synchrotron Light Source, Brookhaven National Laboratory, NY). Intensities were integrated using the HKL2000 program and reduced to amplitudes using the TRUNCATE program (see Table 1)(13, 14). The structure of native LigI was determined using SeMet SAD method with the programs SHELX (15, 16) and wARP (17). The structures of the mutant proteins were determined by the molecular replacement method with the program PHASER (18). Model building and refinement were performed with the programs COOT and REFMAC (14, 19). The quality of the final structures was verified with composite omit maps, and stereochemistry was checked with the programs WHATCHECK (20) and PROCHEK (21). LSQKAB and SSM algorithms were used for structural superpositions (14, 22). Structural figures were prepared using UCSF Chimera (23).

Table I.

Data collection and refinement statistics for the LigI crystal structures.

| LigI native, pH 8.5 |

LigI-D248A substrate, pH 8.5 |

LigI-D248A substrate, pH 6.5 |

LigI-D248N substrate, pH 4.6 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDB entry | 4D8L | 4DI8 | 4DI9 | 4DIA |

| Data Collection | ||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.979 | 1.075 | 0.979 | 1.075 |

| Space group | P21 21 21 | P21 | C2 | P21 21 21 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å) | a = 52.10 | a = 74.35 | a = 73.55 | a = 52.27 |

| b = 73.17 | b = 52.13 | b = 50.95 | b = 54.06 | |

| c = 82.75 | c = 76.54 | c = 73.35 | c = 96.52 | |

| α=β=γ=90° | α=γ=90° | α=γ=90° | α=β=γ=90° | |

| β=93.7° | β=91.9 | |||

| Resolution range ( Å ) | 2.0-20.0 | 1.8-20.0 | 1.35-20.0 | 2.0-20.0 |

| Observed reflections | 61,399 | 193,893 | 192,591 | 138,757 |

| Unique reflections | 35,073 | 53,622 | 56,051 | 20,448 |

| Completeness ( % ) a | 84.2(61.8) | 99.8(98.7) | 90.6(46.6) | 98.1(99.9) |

| I/σI | 11.3(3.5) | 18.2(3.1) | 11.7(3.5) | 9.2(3.0) |

| R-merge ( I ) b | 0.057(0.273) | 0.073(0.332) | 0.057(0.554) | 0.080(0.581) |

| Structure Refinement | ||||

| Rcryst ( % ) c | 0.174 | 0.157 | 0.161 | 0.181 |

| Rfree ( % ) c | 0.229 | 0.187 | 0.183 | 0.225 |

| Protein nonhydrogen atoms | 2316 | 4706 | 2339 | 2262 |

| Water molecules | 235 | 646 | 425 | 123 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 33.7 | 17.2 | 16.0 | 34.5 |

|

RMS Deviations from

Ideal value |

||||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.028 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.010 |

| Angles (°) | 2.38 | 1.23 | 1.28 | 1.23 |

| Torsion angles (°) | 20.1 | 13.1 | 13.8 | 15.1 |

Values in parentheses indicate statistics for the high resolution bin.

Rmerge = ΣΣ j∣Ij(hkl) − <I(hkl)>∣/ ΣΣ j∣<I(hkl)>∣, where Ij is the intensity measurement for reflection j and <I> is the mean intensity over j reflections.

Rcryst/(Rfree) = Σ ∣∣Fo(hkl)∣ − ∣Fc(hkl)∣∣/ Σ ∣Fo(hkl)∣, where Fo and Fc are observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

No σ-cutoff was applied. 5% of the reflections were excluded from refinement and used to calculate Rfree.

Enzymatic Synthesis of 4-Oxalomesaconate

OMA was synthesized enzymatically from PDC using LigI as a catalyst. The reaction was carried out in 50 mM CHES, pH 10, with 6.0 mM PDC and 10 μM LigI in a volume of 5.0 mL. The reaction was monitored spectrophotometrically at 312 nm until the reaction was complete. The enzyme was removed by passage through a VWR Centrifugal Filter with a molecular weight cutoff of 3 KDa.

Measurement of Lactonase Activity

The forward and reverse reactions catalyzed by LigI were followed spectrophotometrically with a SpectraMax-340 UV–visible spectrophotometer using a differential extinction coefficient of Δε312 = 6248 M−1 cm−1 at 312 nm (2, 3). Standard assay conditions for the hydrolysis of PDC included 50 mM BICINE, pH 8.25, varying concentrations of PDC (0-300 μM) and LigI in a final volume of 250 μL at 30 °C. For the reverse reaction, standard assay conditions included 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, and variable concentrations of OMA (0-300 μM) and LigI in a final volume of 250 μL at 30 °C. The kinetic constants were calculated from a fit of the initial velocity data to equation 1 using the non-linear least squares fitting program in SigmaPlot 9.0, where v is the initial velocity, Et is the total enzyme concentration, kcat is the turnover number, [A] is the substrate concentration, and Km is the Michaelis constant. The apparent inhibition constants were determined from a fit of the data to equation 2.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Measurement of Equilibrium Constant

The equilibrium constant for the reaction catalyzed by LigI was measured over the pH range 6.0-9.5 at 0.25 pH unit intervals using MES (pH 6.0 - 6.75), HEPES (pH 7.0 - 8.0), BICINE (pH 8.2 - 9.0), and CHES (pH 9.0 - 9.5) to control the pH. In these measurements, LigI was incubated with 250 μM PDC in a final volume of 250 μL until the reaction reach equilibrium. The fractional concentrations of OMA and PDC at each pH were determined from the absorbance at 312 nm using a differential extinction coefficient of 6248 M−1 cm−1. The equilibrium constant was calculated from a fit of the data to equation 3 where y is equal to the mole fraction of PDC at equilibrium.

| (3) |

pH-Rate Profiles

The pH dependence of the kinetic constants, kcat and kcat/Km, was measured over the pH range 6.5 - 9.75 at 0.25 pH unit intervals. The buffers used for the pH rate profiles were MES (pH 6.0 - 6.75), HEPES (pH 7.0 - 8.0), BICINE (pH 8.25 - 9.0) and CHES (pH 9.0 - 9.75). The final pH values were recorded after the completion of the assay. The profiles for the pH dependence of kcat and kcat/Km for lactone hydrolysis and synthesis were fit to equations 4 and 5, respectively, where c is the maximum value for either kcat or kcat/Km, and Ka and Kb are the ionization constants for the groups that must be unprotonated and protonated for catalytic activity, respectively.

| (4) |

| (5) |

Metal Analysis

The metal content of LigI, substrates and buffers was determined with an Elan DRC II ICP-MS as previously described (24). Protein samples for ICP-MS analysis were digested with HNO3 and then refluxed for 30 minutes (25). All buffers were passed through a column of Chelex 100 (Biorad) to remove trace metal contamination. EDTA, 1,1-phenanthroline, dipicolinic acid or 2,2′-bipyridine (1.0 mM) was incubated with 1.0 μM LigI in 50 mM buffer at pH values ranging from 6 to 10 to remove divalent metal ions from LigI. The buffers for these experiments included CHES (pH 6.0), HEPES (pH 7.0), BICINE (pH 8.0) or CHES (pH 9.0 and 10.0). The effect of added divalent cations (as the chloride salts) on the catalytic activity of LigI was determined by adding Mn 2+, Zn 2+, Co2+, Cu2+ or Ni2+ (0 – 500 μM) directly to the assay mixtures. LigI (1.0 μM) was also incubated with 50 – 500 molar equivalents of these divalent cations for 24 hours at 4 °C in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, and then assayed for catalytic activity.

NMR Analysis of OMA and CHM

The tautomeric distribution of OMA and CHM in solution was determined as a function of pH using Hetero Nuclear Multiple Bond Correlation (HMBC) NMR spectroscopy with a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz with an H-C-N cryoprobe using WATERGATE solvent suppression.

Hydrolysis of PDC in H218O

The site of the hydrolysis of PDC by LigI was determined using NMR spectroscopy in 18O-labeled water. The reaction was carried out in 100 mM carbonate, pH 9.9, with 10 mM PDC using 10 μM LigI in a final volume of 1.0 mL for 1 hour in 50% 18O-water. At the conclusion of the reaction LigI was removed from the reaction mixture using a 3 KDa cutoff VWR Centrifugal Filter. D2O was added and the 13C NMR spectrum of the product was obtained.

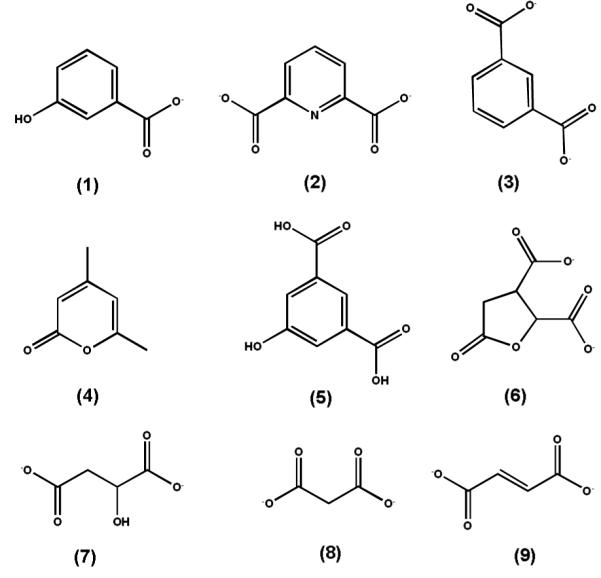

Identification of Inhibitors

Selected compounds (Scheme 2) were evaluated as potential inhibitors of LigI based on structural similarities to PDC, OMA, or CHM. The inhibition assays contained 100 μM PDC, varying concentrations of inhibitor (0 - 500 μM), 50 mM BICINE, pH 8.25, and LigI in a final volume of 250 μL at 30°C.

Scheme 2.

Sequence Similarity Networks

All protein sequences available in NCBI that are designated as belonging to cog3618 were obtained by a simple search using the query “cog3618”. Protein sequences were then subjected to an all-by-all BLAST using the NCBI stand-alone BLAST program at specific stringency E-values (10−10, 10−20, 10−30, 10−40, 10−50, 10−60, and 10−70). At a stringency value of 10−70 many of the groups clustered into smaller (and perhaps isofunctional) groups that were given an arbitrary identifying number.

RESULTS

Purification and Properties of LigI from S. paucimobilis

2-Pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid lactonase from S. paucimobilis was cloned, expressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity. The purified LigI did not contain significant amounts of zinc, manganese, iron, copper, cobalt or nickel (<0.04 equivalents per monomer) when analyzed by ICP-MS. The addition of chelating agents directly to the assay solutions did not affect the rate of PDC hydrolysis. The purified LigI was further incubated with EDTA, 1,10-phenanthroline, dipicolinic acid and 2,2′-bipyridine at pH values from 6 - 10 in an attempt to remove tightly bound metals, but the addition of these potent chelators did not change the catalytic activity of LigI. The addition of Mn2+, Zn2+, Co2+, Cu2+ or Ni2+ directly to the assay solutions had no effect on the catalytic activity of LigI. Therefore, LigI does not appear to require a divalent cation for enzymatic activity.

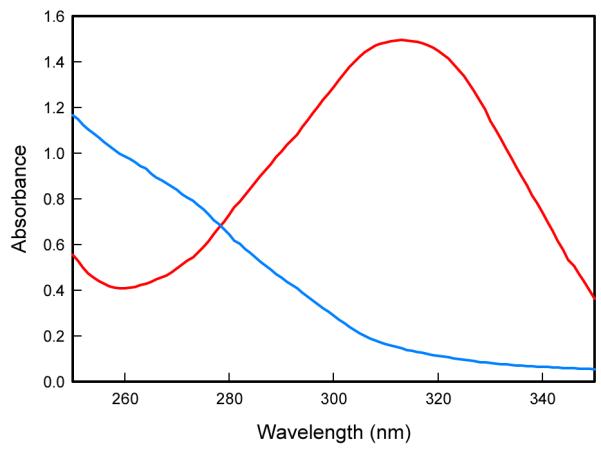

The change in absorbance when PDC is converted to OMA at pH 10.0 is presented in Figure 2. There is an absorption maximum for PDC at 312 nm that is lost upon conversion to OMA. The kinetic constants for the hydrolysis of PDC to OMA/CHM were determined at pH 8.25 to be 342 ± 25 s−1, 48 ± 11 μM and (7.5 ± 1.0) × 106 M−1 s−1 for kcat, Km and kcat/Km, respectively. The kinetic constants in the reverse reaction for the synthesis of PDC from OMA/CHM at pH 8.25 were 116 ± 6 s−1, 18 ± 4 μM and (4.9 ± 0.7) × 106 M−1 s−1 for kcat, Km and kcat/Km respectively.

Figure 2.

UV-visible absorbance spectrum of 0.3 mM PDC (red) and the hydrolysis product after the addition of LigI (blue) at pH 10. The maximum absorbance change is at 312 nm with a differential extinction coefficient, Δε, of 6248 M−1 cm−1.

NMR Spectra for OMA and CHM

The product of the enzymatic reaction existed in two forms depending on the pH. At pH 10, the keto form (OMA) was predominant as shown by the presence of singlet peaks at 6.58 δ (1 H, H-2) and 3.92 δ (2 H, H2-4) in the proton NMR spectrum. The carbon spectrum showed peaks for carbonyl carbons at 202.0 (C-5), 175.1 (C-1), 175.0 (C-6), and 168.6 (C-9) δ, vinyl carbons at 136.9 and 132.8 δ, and an aliphatic carbon at 39.8 δ (C-4). A DEPT experiment indicated that the carbon at 132.8 δ had a single proton attached (C-2) while the carbon producing the peak at 39.8 δ had two attached protons (C-4). The vinyl carbon peak at 136.9 δ is therefore due to C-3. An HMBC experiment showed long range couplings from the proton peak at 3.92 δ to the two vinyl carbons and carbonyl carbons at 202.0 and 175.0 δ. The proton peak at 6.58 δ showed cross peaks to the carbonyl carbon at 175.0 δ, the vinyl carbon at 136.9 δ, and the aliphatic carbon at 39.8 δ. These data indicated that the peak at 175.0 δ correlating to both proton peaks was C-9. Due to chemical shift considerations, the peak at 168.6 δ is due to C-6, indicating that the peak at 175.1 δ comes from C-1.

At pH 6, the enol form (CHM) was predominant. Its proton spectrum consisted of two doublets at 7.19 δ (H-2) and 6.70 δ (H-4) with a coupling constant of 1.3 Hz. The carbon spectrum showed carbonyl carbon peaks at 170.4, 165.5, and 165.4 δ, and vinyl peaks at 153.9, 152.7, 116.4 and 108.1 δ. A DEPT experiment indicated the carbons at 116.4 and 108.1 δ each had a single attached proton. An HSQC experiment showed that the proton at 7.19 δ was attached to the carbon at 116.4 δ (C-2), and the proton at 6.70 δ was attached to the carbon at 108.1 δ (C-4). The HMBC experiment indicated the proton at 7.19 δ had long range couplings to the carbonyl carbons at 170.4 (C-1) and 165.4 δ (C-6), and a vinyl carbon at 153.9 δ (C-3). The peak at 6.70 δ correlated to the carbonyl at 165.5 δ (C-6) and a vinyl carbon at 152.7 δ (C-5). Relative amounts of the two forms at given pH values as estimated by protonated vinyl carbon peak heights were 100% OMA, 0% CHM (pH 10); 90% OMA, 10 % CHM (pH 9); 55% OMA, 45% CHM (pH 8); 5% OMA, 95% CHM (pH 7); and 2% OMA, 98% CHM (pH 6).

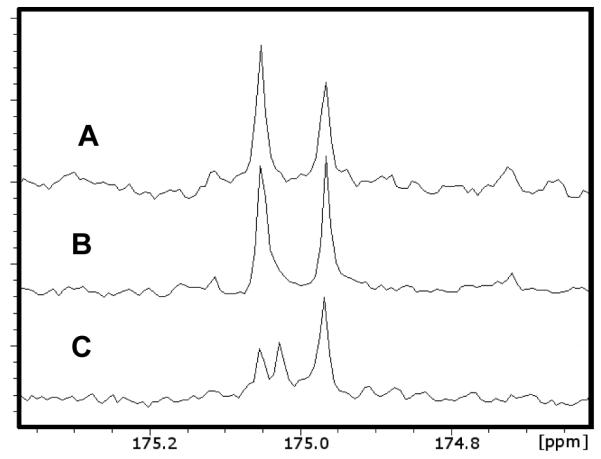

Hydrolysis of PDC in 18O-Water

The regiochemistry for the attack of water on PDC has not previously been determined. Water could attack C-2 with cleavage of the C-2/O-1 bond. Alternatively, water could attack C-6 with cleavage of the C-6/O-1 bond. The enzymatic reaction was conducted in 50% 18O-water to determine the electrophilic center of PDC that reacts with water. If water attacks C-2 then the C-1 carboxylate group of OMA will be labeled with 18O, whereas if the attack occurs on C-6 then the C-5 carbonyl group of OMA will be labeled. Shown in Figure 3A is the 13C-NMR spectrum of the C-1 carboxylate of the product when the enzymatic reaction was conducted in unlabeled water at pH 9.9. The C-1 carboxylate of OMA appears at 175.04 ppm and is a single resonance that is adjacent to the resonance for the C-9 carboxylate at 174.96 ppm. When the reaction was conducted in 18O-water, the C-1 carboxylate of OMA appears as two distinct resonances with a separation of ~0.03 ppm, reflecting the small chemical shift difference for OMA with a single 18O-label (Figure 3C). There was no change in the resonance for the C-1 carboxylate when 18O-water was added to OMA after removal of the enzyme (Figure 3B). Therefore, under the conditions of these experiments the attack by water/hydroxide occurs directly at C-2 of PDC.

Figure 3.

(A) NMR spectrum of OMA in water at pH 9.0. (B) NMR spectrum of OMA incubated in 50% 18O water at pH 9.0. (C) NMR spectrum of OMA produced enzymatically from PDC in 18O water at pH 9.0.

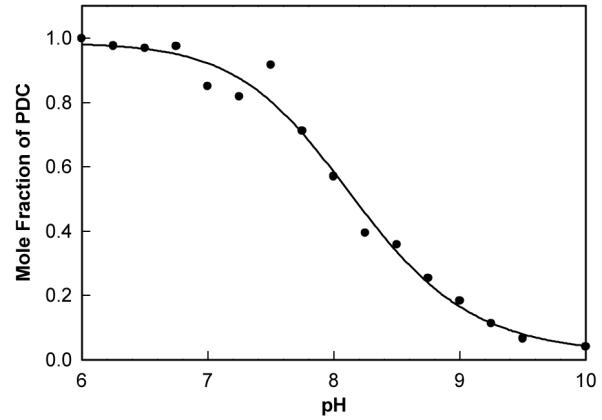

pH-Independent Equilibrium Constant

The reaction catalyzed by LigI is reversible and the equilibrium concentrations of PDC and OMA/CHM are dependent on the solution pH. The equilibrium constant for this reaction was determined by allowing the hydrolysis reaction to come to completion at pH values ranging from 6 - 10. The concentration of PDC was determined from the change in absorbance at 312 nm and the results are presented in Figure 4. The equilibrium constant, from a fit of the data to equation 2, was determined to be 5.7 × 10−9 M−1. At pH 8.25 the relative concentrations of PDC and the hydrolysis products are thus equal to one another. The Haldane relationship for this reaction at this pH value is presented in equation 6. Substitution of the kcat/Km values for the substrate and product determined at pH 8.25 gives an apparent equilibrium constant of 1.5, which is reasonably close to the experimentally determined value of 1.0.

| (6) |

Figure 4.

Effect of pH on the equilibrium concentrations of PDC and OMA/CHM. The line represents a fit of the data to equation 3. The equilibrium constant for the reaction illustrated in Scheme 1 is 5.7 × 10−9 M−1.

Identification of Inhibitors

Nine compounds (see Scheme 2) were tested as potential inhibitors of LigI as a probe of the structural requirements for ligand binding. Of the compounds tested, only pyridine-2,4-dicarboxylic acid (2) and 5-hydroxyisophthalic acid (5) inhibited the hydrolysis of PDC. The apparent inhibition constants for pyridine-2,4-dicarboxylic acid and 5-hydroxyisophthalic acid are 75 ± 2 μM and 40 ± 3 μM, respectively, from fits of the data to equation 2.

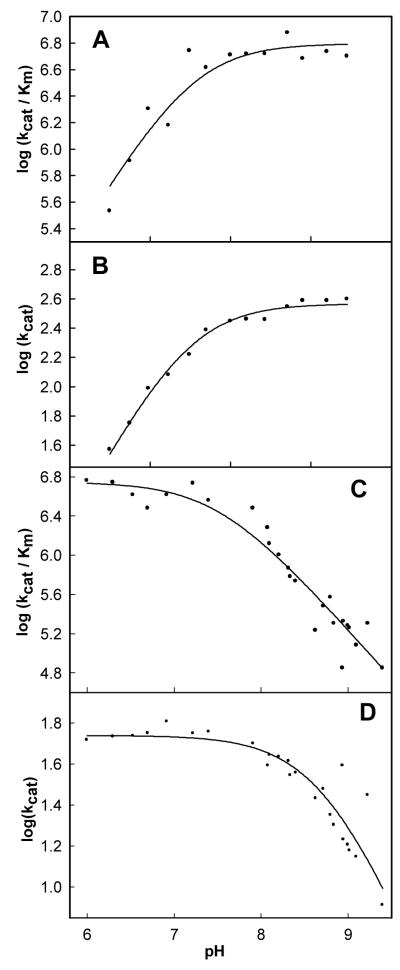

pH-Rate Profiles

Kinetic constants for the hydrolysis and synthesis of PDC by LigI were measured as a function of pH to identify potential active site residues whose involvement in catalysis is dependent on the state of protonation. The profiles for the forward and reverse reactions are presented in Figure 5. The kinetic pKa values for the hydrolysis of PDC are 7.5 ± 0.1 for kcat and kcat/Km. The kinetic pKa values for the condensation of OMA are 8.6 ± 0.1 and 7.5 ± 0.1 for kcat and kcat/Km respectively.

Figure 5.

pH-rate profiles for the enzymatic hydrolysis and synthesis of PDC. (A) pH-rate profile for log (kcat/Km) for the hydrolysis of PDC. (B) pH-rate profile for log (kcat) for the hydrolysis of PDC. The lines for plots A and B represent the fit of the data to equation 4. (C) pH-rate profile for log (kcat/Km) for the synthesis of PDC. (D) pH-rate profile for log (kcat) for the synthesis of PDC. The lines for plots C and D represent the fit of the data to equation 5.

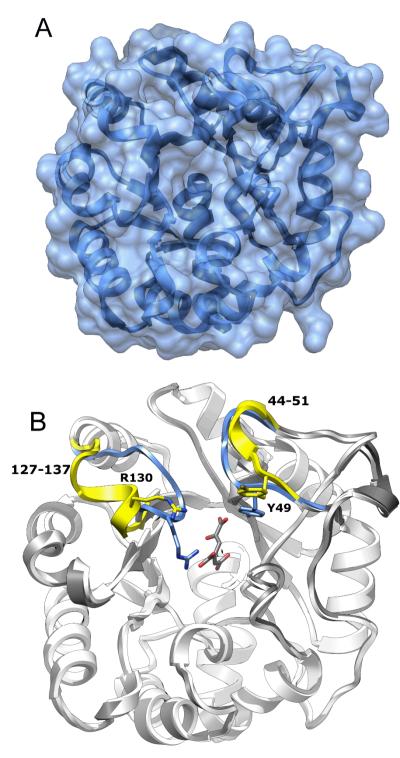

Structure of Wild-Type LigI

The crystal structure of native LigI was determined by single anomalous dispersion (SAD) at 2.0 Å resolution. The model contains protein residues Leu-3 to Glu-296, and 225 water molecules, most of which are well defined in the electron density map. The protein has a distorted TIM-barrel fold, and the wide opening on one end of the barrel suggests the entrance to the active site (Figure 6A). The closest structural homolog in the PDB is a putative 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylate lactonase from Pseudomonas putida ( PDB ID: 2FFI, RMSD 2.8 Å) with a sequence identity of 31%.

Figure 6.

Structure of native LigI and the D248A mutant. (A) Native LigI. The narrow crevice on the top of the solvent accessible surface corresponds to the active site entrance. (B) View of CHM-bound D248A LigI (white) superimposed onto the wild-type apo-form of LigI (gray). The two loops, Phe-127 to Lys-137 and Ser-44 to Pro-51, that exhibit a change in conformation upon substrate binding, are color coded to the following format: Native LigI (apo) is yellow and CHM-bound D248A is blue.

Structure of D248A Mutant

To reveal the structural details of LigI interactions with substrate, the inactive mutant D248A was produced and co-crystallized with the substrate. Diffraction data were collected for the complex at pH 6.5 and 8.5 (Table 1). In both structures the ligand is well defined in the corresponding electron density maps. Substrate binding results in closure of the active site and large-scale rearrangement of two loops: Phe-127 to Lys-137, and to a lesser extent Ser-44 to Pro-51 (Figure 6B). As a result of this structural rearrangement, the first loop transforms from an α-helical conformation to a coiled conformation, and the guanidinium group of Arg-130 moves by 6.1 Å to directly contact the substrate C-8 carboxylic group and to close the entrance of the active site. The phenolic side chain of Tyr-49 moves 14.4 Å to be in direct contact with the C-11 carboxylate of PDC.

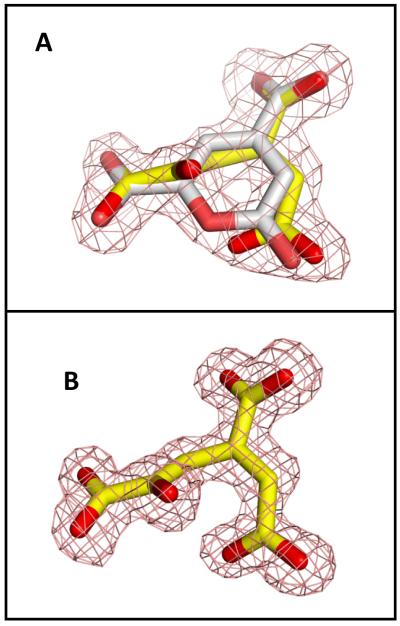

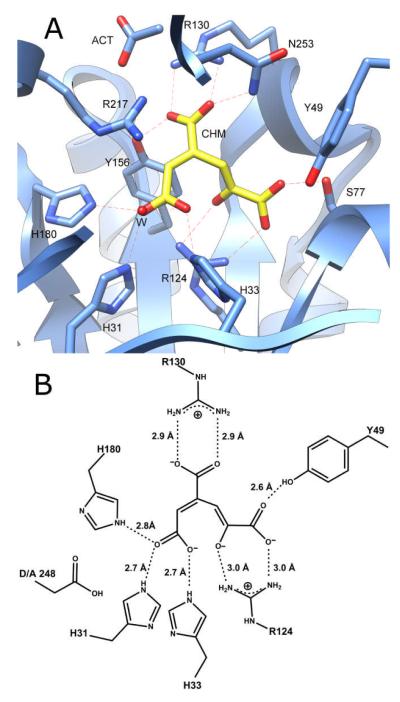

At pH 8.5, an almost equal mixture of the substrate and product was observed in the active site. The presence of the product can be explained by residual catalytic activity or spontaneous hydrolysis of the substrate in solution. Interestingly, at pH 6.5 only CHM is present in the active site. The electron densities for the bound substrate/product ligands in the active site of LigI at pH 8.5 and 6.5 are shown in Figures 7A and 7B, respectively. PDC forms multiple interactions in the active site: the C-4 carboxylate forms four hydrogen bonds with Arg-130, Asn-253, and Tyr-156; the C-6 carboxylate forms four hydrogen bonds with Arg-124, Tyr-49, Ser-77; and the C-2 carbonyl group forms four hydrogen bonds with His-31, His-180, and a water molecule. CHM occupies a similar position as the substrate and makes multiple interactions: the C-9 carboxylate forms four hydrogen bonds with Arg-130, Asn-253, and Tyr-156; the C-6 carboxylate forms four hydrogen bonds with Arg-124, Tyr-49, Ser-77; and the remaining carboxylate group (C-1) forms four hydrogen bonds with His-31, His-180, His-33, and a water molecule. The C-5 hydroxyl group of the product forms two hydrogen bonds with Arg-124. Nearby, Arg-217 forms hydrogen bonds with acetate and another water molecule (Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Refined electron density (2FoFc, contoured at 1σ) of the ligand in the active site of LigI. (A) Presence of about equimolar amount of substrate (PDC, white) and product (CHM, yellow) at pH 8.5; (B) Presence of product only (CHM, yellow) at pH 6.5.

Figure 8.

(A) CHM bound in the active site of the D248A mutant of LigI at pH 6.5. No PDC was detected at this pH. (B) Active site structure of D248A with CHM in the active site.

Structure of D248N Mutant

The structure of the D248N mutant was determined from crystals grown at pH 4.6 in the presence of the purified product PDC. The refined electron density did not show the presence of either substrate or product in the active site. This can be explained by the reduced affinity of the active site towards substrate/product under very acidic conditions. The structure of the D248N mutant is very similar to the structure of ligand-free wild-type LigI (RMSD 0.42 Å), and the conformations of Asn-248 in the mutant enzyme and Asp-248 in the wild-type enzyme are identical.

Mutagenesis of LigI

Residues in LigI that align with the prototypical metal coordinating residues in the AHS were mutated. These residues included the following: His-31 and His-33 from the C-terminal end of β-strand 1, His-180 from the end of β-strand 6 and Asp-248 from the end of β-strand 8. Additional active site residues that were mutated included: Tyr-156, Arg-124, Tyr-49, Arg-130, Arg-217, and Arg-183. Tyr-156 from the end of β-strand 5 replaces the conserved histidine residue that coordinates a divalent cation in those members of the AHS with either a mononuclear or binuclear metal center. Arg-124 from the end of β-strand 4 is positioned to occupy the space filled by the residue that bridges the two divalent cations in those members of the AHS with a binuclear metal center. Tyr-49, Arg-130, and Arg-183 are in the active site and interact with the substrate/product. The kinetic constants for these mutants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Catalytic constants for Wild-Type LigI and Various Mutants for PDC hydrolysis.a

| enzyme | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 342 ± 25 | 48 ± 11 | (7.1 ± 1) × 106 |

| D248A | 0.0013 ± 0.0001 | 116 ± 18 | (1.6 ± 0.2) × 101 |

| D248N | 0.023 ± 0.001 | 66 ± 13 | (2.0 ± 0.34) × 10 2 |

| R124M | 0.020 ± 0.001 | 90 ± 15 | (2.0 ± 0.22) × 102 |

| R130M | 5.0 ± 0.4 | 465 ± 104 | (1.1 ± 0.7) ×104 |

| H31N | 0.40 ± 0.04 | 720 ± 122 | (5.0 ± 0.37) × 102 |

| R217M | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 67 ± 10 | (6.3 ± 0.4) × 103 |

| H180A | 8.0 ± 0.9 | 214 ± 44 | (3.7 ± 0.4) ×104 |

| H180C | 32 ± 4 | 41 ± 7 | (7.8 ± 0.5) × 105 |

| H33N | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 89 ± 20 | (4.1 ± 0.6) × 104 |

| Y49F | 26 ± 2 | 217 ± 41 | (1.2 ± 0.02) × 105 |

| Y156F | 8.7 ± 0.3 | 238 ± 19 | (3.7 ± 0.02) × 104 |

| R183M | 196 ± 6 | 64 ± 6 | (3.0 ± 0.02) × 106 |

Standard assay conditions for the hydrolysis of PDC included 50 mM BICINE, pH 8.25, at 30 °C.

DISCUSSION

Potential Role of Divalent Metal Ions

Although all well-characterized amidohydrolases require 1-3 divalent metal ions for catalytic activity, LigI and other members of cog3618 exhibit active site differences from other amidohydrolase superfamily members that argue they are not metallo-enzymes. We were unable to detect bound metal ions via ICP-MS in the samples of recombinant LigI prepared for this investigation. In addition, metal ion chelators had no effect on the catalytic activity of LigI and the addition of divalent cations to enzymatic assays had no effect on reactions rates. Therefore, we conclude that LigI from Sphingomonas paucimobilis does not require a divalent cation for catalytic activity and does not bind divalent metals to any significant extent. To the best of our knowledge this work provides the first documented example of an enzyme from the AHS that does not require a divalent cation to bind in the active site for catalytic activity. It will be of mechanistic interest to determine whether or not other proteins of unknown function within cog 3618 require divalent cations for catalytic activity.

The Active Site of LigI

Nearly all members of the AHS have a constellation of five amino acid residues that are conserved within the active site and required for metal ion binding and/or proton transfers (5). These residues include two histidine residues from the end of β-strand 1, two additional histidine residues from the ends of β-strands 5 and 6, and a conserved aspartate residue from the end of β-strand 8. In LigI the three histidine residues (H31, H33, and H180) from the ends of β-strands 1 and 6 are conserved in addition to the aspartate (D248) from the end of β-strand 8. The histidine from the end of β-strand 5 is absent. Since LigI does not require the binding of divalent cations for the expression of catalytic activity, the functional role of these conserved residues must be different then they are for the rest of the amidohydrolase superfamily.

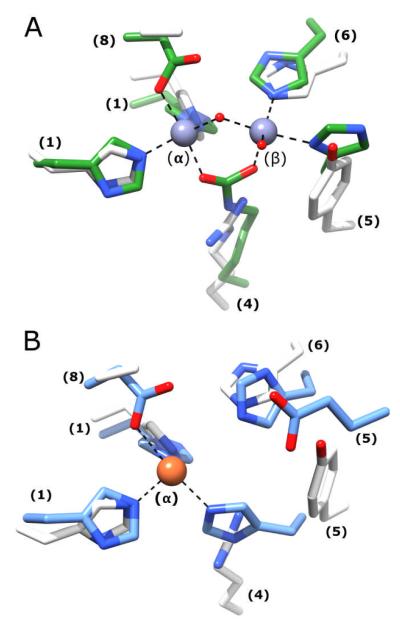

A structural alignment of the active site of LigI and phosphotriesterase (PTE), an enzyme with a prototypical binuclear metal active site, is presented in Figure 9A. The HxH motif from β-strand 1, the histidine from β-strand 6 and the aspartate from β-strand 8 of LigI align well with the corresponding residues in PTE. In addition, Tyr-156 from β-strand 5 of LigI aligns with the conserved histidine from β-strand 5 of PTE and Arg-124 from β-strand 4 of LigI aligns with the carboxylated lysine from β-strand 4 of PTE. In PTE the carboxylated lysine serves to bridge the two divalent cations. The active site of LigI is overlaid with the active site of cytosine deaminase (CDA), a mononuclear metal active site in Figure 9B. The HxH motif from β-strand 1, the histidine from β-strand 6 and the aspartate from β-strand 8 of LigI align reasonably well with the corresponding residues of CDA. However, Tyr-156 from LigI does not align with the conserved histidine from β-strand 5 of CDA. The inability of LigI to bind a divalent metal appears to stem from the presence of the positively charged Arg-124 in the active site

Figure 9.

(A) The active site of D248A LigI is structurally aligned with the binuclear metal center of phosphotriesterase (PTE). The active site is color-coded to the following format: PTE, PDB code: 1hzy (green) and D248A LigI active site is shown in white. (B)The active site of D248A LigI is structurally aligned with the mononuclear metal center found in the active site of cytosine deaminase. The active sites are color-coded to the following format: CDA, PDB code: 1k70 (blue) and D248A LigI active site is shown in white. Numbers in parentheses indicate the β- strand origin of each residue.

Role of Conserved Residues and Mechanism of Action

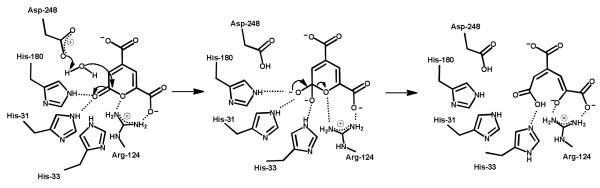

A working model for the hydrolysis of PDC by LigI is presented in Scheme 3. In this mechanism some of the conserved AHS active site residues, which normally participate in metal coordination, have different catalytic roles in the function of this protein. The four residues in question are His-31, His-33, His-180 and Asp-248. The binding of PDC is facilitated by ion pair interactions between Arg-130 and Arg-124 with the C-8 and C-11 carboxylates, respectively. There is an additional electrostatic interaction between Tyr-49 and the C-11 carboxylate. The lactone carbonyl group of the substrate is polarized by electrostatic interactions with the three conserved histidine residues: His-31, His-33, and His-180. Asp-248 is positioned in the active site to deprotonate an active site water molecule for nucleophillic attack on the C-2 carbonyl group of the substrate. The orientation of Asp-248 allows for the attack on the re-face of PDC, which is consistent with the relative orientation of attack determined previously for other members of the amidohydrolase superfamily (26). After formation of the tetrahedral intermediate the C-2/O-1 bond is cleaved with support of the electrostatic interaction of the guanidino group of Arg-124.

Scheme 3.

Further support for the proposed mechanism of action comes from our structure with substrate/product ligands bound to the enzyme and the catalytic properties of selected LigI mutants. The importance of D248 is confirmed by the nearly complete absence of activity for the D248A and D248N mutants. These mutants are reduced in activity by 4-5 orders of magnitude (for either kcat or kcat/Km). Of the three conserved histidine residues in the active site, the mutation of His-31 results in the greatest loss of catalytic power. Mutation of this residue to asparagine reduces kcat/Km by more than four orders of magnitude. Mutation of either His-33 or His-180 reduces this kinetic constant by approximately two orders of magnitude. The mutation of Tyr-49 to phenylalanine reduces kcat/Km about 60-fold and mutation of Arg-124 reduces kcat/Km by a factor of ~30,000. The pH rate profiles are consistent with an active site residue that must be deprotonated for catalytic activity. This residue is most likely assigned to either Asp-248 or to His-31. Tyr-156 is 2.5 Å away from the C-8 carboxylate oxygen and 3.6 Å away from C-2.

Additional LigI Sequences

Candidate LigI sequences were obtained from the NCBI protein data base through a BLAST search with LigI from S. paucimobilis as the query sequence. The candidate sequences had to meet a minimum E value cutoff of 10−70 to be considered for further analysis. All protein sequences were aligned to that of the experimentally verified LigI from S. paucimobilis. Sequences were considered to be LigI if they conserve the following active site residues: His-31, His-33, Tyr-49, Arg-124, Arg-130, Tyr-156, His-180 and Asp-248. The 66 sequences that conform to the specific conserved residues are now postulated to be LigI proteins and are shown as green nodes in group 3 of Figure 1 and are listed in Table S1.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Rafael Toro for his help with crystallization; and to the X29 beamline staff for their help with diffraction data collection.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the NIH (GM 71790 and GM 74945) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (A-840). The X-ray coordinates and structure factors for LigI have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank: 4D8L, 4DI8, 4DI9, and 4DIA.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT The X-ray coordinates and structure factors for LigI have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank: 4D8L, 4DI8, 4DI9, and 4DIA).

Supporting Information. Supplemental Table S1 provides a list of bacterial proteins predicted to catalyze the same reaction as LigI. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hishida M, Shikinaka K, Katayama Y, Kajita S, Masai E, Nakamura M, Otsuka Y, Ohara S, Shigehara K. Polyesters of 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid (PDC) as bio-based plastics exhibiting strong adhering properties. Polymer Journal. 2009;41:297–302. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kersten PJ, Dagley S, Whittaker JW, Arciero DM, Lipscomb JD. 2-Pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid, a catabolite of gallic acids in Pseudomonas species. Journal of Bacteriology. 1982;152:1154–1162. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.3.1154-1162.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maruyama K. Purification and properties of 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylate hydrolase. Journal of Biochemistry. 1983;93:557–565. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holm L, Sander C. An Evolutionary Treasure: Unification of a Broad Set of Amidohydrolases Related to Urease. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet. 1997;28:72–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seibert CM, Raushel FM. Structural and Catalytic Diversity within the Amidohydrolase Superfamily. Biochemistry. 2005;44:6383–6391. doi: 10.1021/bi047326v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tatusov RL, Natale DA, Garkavtsev IV, Tatusova TA, Shankavaram UT, Rao BS, Kiryutin B, Galperin MY, Fedorova ND, Koonin EV. The COG Database: New Developments in Phylogenetic Classification of Proteins from Complete Genomes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2001;29:22–28. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halak S, Basta T, Buerger S, Contzen M, Wray V, Pieper DH. 4-Sulfomuconolactone hydrolases from Hydrogenophaga intermedia S1 and Agrobacterium radiobacter S2. Journal of Bacteriology. 2007;189:6998–7006. doi: 10.1128/JB.00611-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe S, Saimura M, Makino K. Eukaryotic and bacterial gene clusters related to an alternative pathway of nonphosphorylated L-rhamnose metabolism. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:20372–20382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL, Ideker T. Cytoscape 2.8: new features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:431–432. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atkinson HJ, Morris JH, Ferrin TE, Babbitt PC. Using sequence similarity networks for visualization of relationships across diverse protein superfamilies. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masai E, Shinohara S, Hara H, Nishikawa S, Katayama Y, Fukuda M. Genetic and Biochemical Characterization of a 2-pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic Acid Hydrolase Involved in the Protocatecuate 4,5-Cleavage Pathway of Sphingomonas paucimobilis SKY-6. Journal of Bacteriology. 1999;181:55–62. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.55-62.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Studier FW. Protein production by auto-induction in high density shaking cultures. Protein Expr. Purif. 2005;41:207–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otwinowski ZM, Minor W. Processing of x-ray Diffraction data collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The CCP4 Suite: Programs for Protein Crystallography. Acta Cryst. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheldrick GM. Macromolecular phasing with SHELXE. Z. Kristallogr. 2002;217:644–650. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM. Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Cryst. 2002;58:1772–1779. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langer G, Cohen SX, Lamzin VS, Perrakis A. Automated macromolecular model building for X-ray crystallography using ARP/wARP version 7. Nature Protocols. 2008;3:1171–1179. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storoni LC, McCoy AJ, Read RJ. Likelihood-enhanced fast rotation functions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:432–438. doi: 10.1107/S0907444903028956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooft RW, Vriend G, Sander C, Abola EE. Errors in protein structures. Nature. 1996;381:272. doi: 10.1038/381272a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laskowski RA, Moss DS, Thornton JM. Main-chain bond lengths and bond angles in protein structures. J Mol Biol. 1993;231:1049–1067. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2256–2268. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904026460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall RS, Xiang DF, Xu C, Raushel FM. N-Acetyl-D-glucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase: substrate activation via a single divalent metal ion. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7942–7952. doi: 10.1021/bi700543x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamat SS, Bagaria A, Kumaran D, Hampton GP, Fan H, Sali A, Sauder JM, Burley SK, Lindahl PA, Swaminathan S, Raushel FM. Catalytic mechanism and three-dimensional structure of adenine deaminase. Biochemistry. 2011;50:1917–1927. doi: 10.1021/bi101788n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiang DF, Kolb P, Fedorov AA, Meier MM, Fedorov LV, Nguyen TT, Sterner R, Almo SC, Shoichet BK, Raushel FM. Functional annotation and three-dimensional structure of Dr0930 from Deinococcus radiodurans, a close relative of phosphotriesterase in the amidohydrolase superfamily. Biochemistry. 48:2237–2247. doi: 10.1021/bi802274f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.