Abstract

Cigarette smoking, nicotine replacement therapy, and smokeless tobacco use during pregnancy are associated with cognitive disabilities later in life in children exposed prenatally to nicotine. The disabilities include attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct disorder. However, the structural and neurochemical bases of these cognitive deficits remain unclear. Using a mouse model we show that prenatal nicotine exposure produces hyperactivity, selective decreases in cingulate cortical volume, and radial thickness, as well as decreased dopamine turnover in the frontal cortex. The hyperactivity occurs in both male and female offspring and peaks during the “active” or dark phase of the light/dark cycle. These features of the mouse model closely parallel the human ADHD phenotype, whether or not the ADHD is associated with prenatal nicotine exposure. A single oral, but not intraperitoneal, administration of a therapeutic equivalent dose (0.75 mg/kg) of methylphenidate decreases the hyperactivity and increases the dopamine turnover in the frontal cortex of the prenatally nicotine exposed mice, once again paralleling the therapeutic effects of this compound in ADHD subjects. Collectively, our data suggest that the prenatal nicotine exposure mouse model has striking parallels to the ADHD phenotype not only in behavioral, neuroanatomical, and neurochemical features, but also with respect to responsiveness of the behavioral phenotype to methylphenidate treatment. The behavioral, neurochemical, and anatomical biomarkers in the mouse model could be valuable for evaluating new therapies for ADHD and mechanistic investigations into its etiology.

Introduction

Prenatal exposure to nicotine can produce lifelong changes in the brain and behavior of the exposed individual (Slotkin et al., 1987; Ernst et al., 2001; Pauly et al., 2004; Wickström, 2007). Although cigarette smoking among pregnant women and women of childbearing age has declined in recent years, exposure to nicotine during pregnancy via nicotine replacement therapy, smokeless tobacco, as well as direct and secondhand cigarette smoke continues to be a serious problem all over the world (for review, see Wickström, 2007). Although cigarette smoke contains thousands of unique ingredients, many of which are harmful, the behavioral effects of cigarette smoke exposure appear to be mainly due to the actions of nicotine on the developing and mature brain (Slotkin et al., 1987; Navarro et al., 1989).

The principal direct effect of nicotine on the fetal brain is on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (Slotkin et al., 1987; Slotkin, 2004). Since cholinergic signaling regulates release of other neurotransmitters including dopamine (Chesselet, 1984), and since neurotransmitters regulate neurogenesis, neuronal migration, and differentiation (Crandall et al., 2007; Bhide, 2009), the consequences of fetal nicotine exposure extend well beyond cholinergic dysfunction (for review, see Wickström, 2007; Cornelius and Day, 2009). Specifically, previous studies indicated that nicotine exposure alters dopaminergic signaling in the fetal brain (Richardson and Tizabi, 1994), and dopaminergic signaling plays key roles in the regulation of fetal brain development (Bhide, 2009).

Cigarette smoking during pregnancy is associated with cognitive disabilities in the offspring including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct disorder (Milberger et al., 1996, 1998; Ernst et al., 2001; Fried and Watkinson, 2001; Cornelius and Day, 2009). However, other studies reported minor, if any, adverse cognitive consequences of maternal cigarette smoking for the exposed children (Thapar et al., 2009; Obel et al., 2011). Thus, the evidence in favor of deleterious consequences of prenatal nicotine exposure should be balanced against findings of minor or no such consequences.

We showed recently that children born to mothers who smoked cigarettes during pregnancy showed symptoms of ADHD that are indistinguishable from the ADHD symptoms due to other etiologies (Biederman et al., 2012). Our study in human subjects could not answer key questions such as whether prenatal nicotine exposure altered brain structure, neurotransmitter content, and behavior and whether such changes could be mitigated by methylphenidate (MPH), a stimulant compound with proven efficacy in treatment of ADHD. Here, we use a mouse model of prenatal nicotine exposure to address these unanswered questions and test the hypothesis that prenatal nicotine exposure produces alterations in locomotor activity, neurotransmitter content, and brain structure, and that these changes can be ameliorated by MPH treatment.

Our data show that prenatal nicotine exposure produces hyperactivity, decreases in cingulate cortical volume and radial thickness, and decreased dopamine turnover in the frontal cortex of mice. A single oral administration of therapeutic equivalent doses (0.75 mg/kg) of MPH decreases the hyperactivity and increases the dopamine turnover. Thus, our mouse model recapitulates the behavioral, neurochemical and anatomical changes and responsiveness to stimulant treatment associated with ADHD.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories and housed in our institutional animal facility on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights off at 7:00 P.M. and on at 7:00 A.M.). All of the experimental procedures described below were in full compliance with institutional and NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Prenatal nicotine exposure.

We administered nicotine in saccharin-flavored drinking water [0.05, 0.1, or 0.2 mg/ml (−)-nicotine dissolved in 2% saccharin; Sigma] to female C57BL/6 mice starting 3 weeks before mating and throughout pregnancy. The male breeders were not exposed to nicotine. Control groups included mice receiving 2% saccharin in drinking water or plain drinking water without additives. Thus, we created three prenatal exposure groups: prenatal nicotine plus saccharin exposure (PNE); prenatal saccharin exposure (SAC); and prenatal plain drinking water exposure (WATER). On the day of birth [postnatal day 0 (P0)], offspring in the PNE and SAC groups were cross-fostered to drug-naive nursing mothers. The offspring from the WATER group were not cross-fostered. The litter size was standardized to six to eight pups in each of the three groups of mice on P0. The offspring in each group were weighed every day from P3 to P42. We did not weigh the offspring on P0, P1, or P2 so as not to unduly disturb the mother or the litter.

In the experiments described below, we used not more than one male and one female offspring from any given litter to minimize the contribution of litter effects to the data. We used 10–12 liters of mice from each experimental group to achieve an n value of 8–12 for each type of analysis.

Administration of MPH.

Methylphenidate HCl (Sigma) was dissolved in saline (SAL), pH 7.4, and administered by oral gavage or intraperitoneal injection to P42 or P60 mice. The MPH doses used for the intraperitoneal administration were 0.75, 1.5, 3.5, or 7.5 mg/kg. The MPH dose used for oral gavage was 0.375 or 0.75 mg/kg. The gavage volume was kept constant at ∼10 μl/g body weight.

Analysis of spontaneous locomotor activity.

On the day of analysis, the mice (P42–P60) were removed from their home cages, where they had been housed in groups of three or four, and placed individually in the testing cages equipped with photobeam motion sensors (Photobeam Activity System; San Diego Instruments). Each instance in which consecutive breaks were recorded in adjacent photobeams (positioned 5.4 cm apart) was scored as an ambulatory event. Photobeam breaks were grouped into hourly activity measurements for statistical analysis. Since locomotor activity increased transiently immediately upon placement of the mice in the novel environment (i.e., test cage), we did not include in our analysis locomotor activity during the initial 2 h upon placement of the mouse in the testing chamber.

High-performance liquid chromatography.

Mice were decapitated, and the brains were removed from the skulls and cut into 500-μm-thick coronal slices using a brain slice matrix (Fisher Scientific). The frontal cortex and striatum were identified in the slices based on anatomical landmarks (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001), and samples of each region were collected as described previously (Balcioglu et al., 2009; Ren et al., 2011). For each brain region, samples from the right and left hemispheres from the same subject were pooled into a single sample for that subject. Each pooled sample was weighed immediately upon dissection. The tissue samples (at least 10 mg tissue per sample) were homogenized in 200 μl of extraction buffer (50 mm phosphoric acid, 0.1 mm EDTA, 50 μm methyl-DOPA (internal standard), and 1 μm 3,4 Dihydroxybenzylamine (DHBA, internal standard). The protein concentration in each sample was evaluated with BCA protein assay method. The samples were stored at −80°C until further analysis.

Tissue concentrations of dopamine (DA), serotonin (5-HT), and their metabolites, 3,4 dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) were analyzed using an isocratic method with electrochemical detection and a Varian Microsorb-MV reverse-phase column (150 × 4.6 mm, C18, 5 μm pore size). The mobile phase was based on the MD-TM mobile phase (ESA Biosciences; Dionex) and was composed of 75 mm sodium phosphate, 1.75 mm 1-octanesulfonate sodium salt, 100 μl/L triethylamine, 25 μm EDTA, and 10% acetonitrile. The flow rate was 0.6 ml/min and the injection volume of each sample was 15 μl. Detection was performed using a coulometric cell with an analytical potential of +225 mV. Data collection was performed by a CouloChem II detector and EZChrom Elite software.

Concentration of analysates was determined using a standard curve at the beginning of every run. DHBA was used as an internal standard to correct for minor variations between biological samples in each run. Concentrations (femtomoles per milligram protein) of dopamine, serotonin, and their metabolites were calculated by using the following formula: fmol/mg protein = μm * 15/loading μg protein * 1000.

Stereological estimation of regional brain volume.

Mice were anesthetized on P42 (ketamine, 50 mg/kg body weight; xylazine, 10 mg/kg body weight, i.p.) and perfused through the heart with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.2. The brains were removed and postfixed in the same fixative at 4°C overnight and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose at 4°C overnight. The cryoprotected brains were frozen in powdered dry ice and mounted on a sliding microtome stage, and coronal sections were cut at 50 μm thickness. Every section that contained the cingulate cortex and caudate–putamen was collected in rostral-to-caudal serial order in phosphate buffer (0.1 m, pH 7.2). Our preliminary studies established that analysis of every fourth section of the series provided accurate estimates of regional brain volume. Therefore, based on the roll of a die every fourth section of the series was chosen. The caudate–putamen was identified using anatomical landmarks [corpus callosum, external capsule, lateral ventricle, globus pallidus, and anterior commissure (Paxinos and Franklin, 2001; McCarthy et al., 2007)]. Cingulate cortex included Cg1 (cingulate cortex area 1) and Cg2 (cingulate cortex area 2). Stereo investigator software (MBF Bioscience) was used to estimate the volume of the different brain regions (see Table 2). The hardware for microscopic analysis consisted of a light microscope (Nikon E2000) connected to a cool CCD camera (Microfire; Optronics), motorized X–Y stage (Ludl Electronics Products), z-axis indicator (MT12 microcator; Heidenhain), and a computer running Stereo Investigator software (Microbrightfield). The Cavalieri method was used to evaluate the regional brain volumes (McCarthy et al., 2007, 2011).

Table 2.

Mean ± SEM values (mm3) of regional brain volumes in SAC and PNE mice

| SAC (mm3) | PNE (mm3) | % Change | Normalized by SAC (% hemispheric volume) | Hemisphere PNE (% hemispheric volume) | % Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemisphere | 60.47 ± 1.53 | 57.58 ± 1.24 | −4.8 | |||

| Cingulate cortex | 2.51 ± 0.25 | 1.91 ± 0.12 * | −23.9 | 4.11 ± 0.34 | 3.29 ± 0.16* | −19.8 |

| Striatum | 11.14 ± 0.39 | 10.50 ± 0.37 | −5.7 | 18.43 ± 0.45 | 18.20 ± 0.37 | −1.2 |

| Sensory-motor cortex | 20.76 ± 0.52 | 20.89 ± 0.42 | 0.6 | 34.34 ± 0.26 | 36.34 ± 0.68* | 5.8 |

| Corpus callosum | 3.06 ± 0.11 | 2.89 ± 0.09 | −5.5 | 5.05 ± 0.1 | 5.02 ± 0.13 | −0.5 |

| Lateral ventricles | 2.09 ± 0.122 | 2.25 ± 0.11 | 7.8 | 3.46 ± 0.21 | 3.9 ± 0.12 | 12.5 |

The mice were males and aged P42 (n = 11 for each SAC or PNE).

*p < 0.05 (Student's t test).

Measurement of the radial (length) and vertical (width) dimensions of the cingulate cortex.

In every section that was used for the stereological volumetric analysis of the cingulate cortex from six brains from each experimental group, we measured the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the gray matter of the cingulate cortex.

Data analysis.

Differences between experimental groups were analyzed for statistical significance by ANOVA whenever more than groups were being compared. For comparison of the effects of prenatal treatment (WATER, SAC, PNE) on male and female mice during lights-on and lights-off periods (prenatal treatment by gender by time), we used three-way ANOVA. In other cases involving more than two groups, two- or one-way ANOVA was used. When a significant difference (p < 0.05) was found by ANOVA, a multiple comparison post hoc test (Tukey–Kramer) was applied to identify groups differing significantly from each other. When only two experimental groups were compared, we used Student's t test.

Results

The effects of nicotine dose on survival and locomotor activity

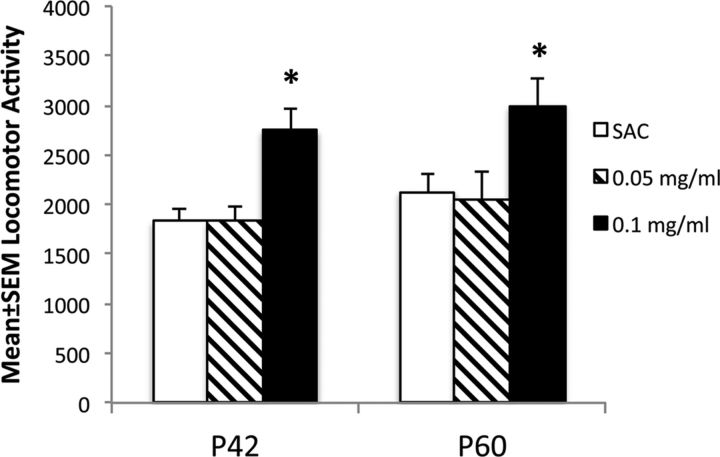

Although we used 0.05, 0.1, and 0.2 mg/ml nicotine in the PNE group, we found that mortality among offspring in the 0.2 mg/ml nicotine exposure group was so high that fewer than four pups survived in any given litter beyond the first postnatal week. Therefore, we did not continue using this dose of nicotine any further. To determine the lowest nicotine dose that produced changes in locomotor activity, we compared locomotor activity among three groups of male mice: SAC mice, the 0.05 mg/ml nicotine group, and the 0.1 mg/ml nicotine group (Fig. 1). The locomotor activity was analyzed over a 4 h period beginning at 8:00 A.M. We used P42 and P60 mice to determine whether any effects of the PNE were transient during the early postnatal period (i.e., at P42) or if they lasted into young adulthood (P60). ANOVA revealed significant effects of the PNE in both P42 and P60 groups (P42, F(2,27) = 10.8, p = 0.004; P60, F(2,27) = 4.78, p = 0.001). Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison tests showed that the activity in the 0.1 mg/ml group was significantly higher than that in the SAC group both at P42 (p < 0.001) and P60 (p < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference in locomotor activity between the 0.05 mg/ml nicotine group and the SAC group. Since the 0.05 mg/ml nicotine group did not show significant changes in locomotor activity, and since the 0.2 mg/ml nicotine exposure group showed high newborn mortality, the 0.1 mg/ml nicotine exposure represented the lowest effective nicotine dose in our model. Therefore, we used this nicotine dose in the remaining studies, and in the description below PNE refers to 0.1 mg/ml nicotine exposure.

Figure 1.

The effects of two different doses (0.05 and 0.1 mg/ml drinking water) of prenatal nicotine treatment on spontaneous locomotor activity were compared to the effects of prenatal treatment with saccharin vehicle alone (SAC, 2% in drinking water) in male mice at P42 and P60. Locomotor activity was analyzed for a 4 h period beginning at 08:00 A.M. (n = 8–13 for each group). *p < 0.05.

Body weight

We compared body weights of offspring in each of the three experimental groups daily from P3 to P42. ANOVA revealed significant effects of the prenatal treatment on body weight measurements on P3 [mean ± SEM body weight, PNE, 2.48 ± 0.07 g; SAC, 2.76 ± 0.08 g; WATER, 2.76 ± 0.06 g; F(2,87) = 4.536, p < 0.05]. A multiple comparison test revealed that the offspring in the PNE group weighed significantly less than the offspring in the SAC group. However, there was no significant difference in the body weight among the three groups at any of the subsequent postnatal time points. No significant difference was found between the plain drinking water and saccharin alone groups of mice at any time during the interval P3 to P42.

Spontaneous locomotor activity

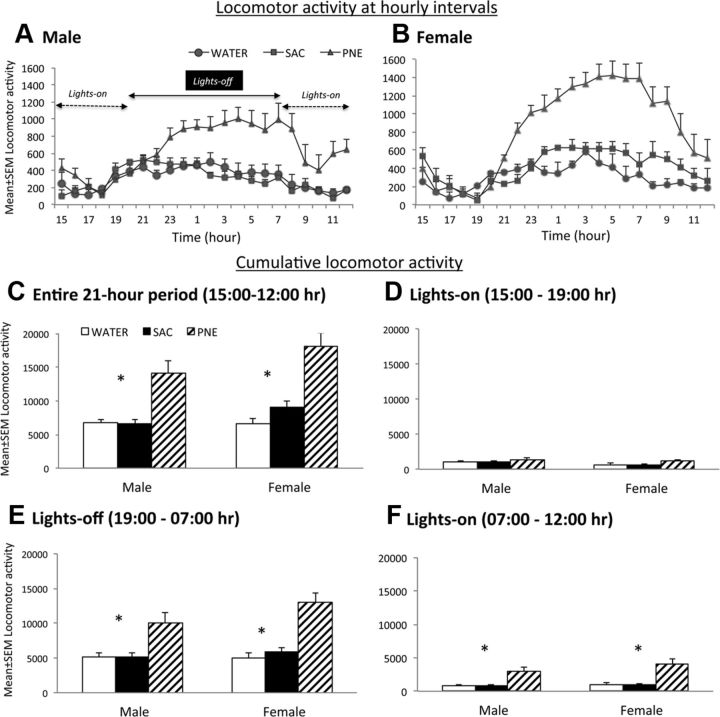

Next we performed a detailed comparison of spontaneous locomotor activity among the WATER, SAC, and PNE experimental groups. The activity was analyzed over a 21 h period beginning at 3:00 P.M. and ending at 12:00 P.M. the following day. The activity was measured at hourly intervals (Fig. 2A,B) separately in males and females in each of the three experimental groups (WATER, SAC, and PNE). The distribution of hourly locomotor activity data (Fig. 2A,B) in male and female mice showed that in both cases, the mice in the PNE group were more active than the mice in the SAC and WATER groups during the lights-off period (7:00 P.M. to 7:00 A.M.) compared to the lights-on periods from 3:00 P.M. to 7:00 A.M. and 7:00 A.M. to 12:00 P.M.. Moreover, the activity levels during the lights-on period were different immediately following the lights-off period and immediately preceding the lights-off period. In other words, the activity levels were not uniform throughout the lights-on period. Therefore, we analyzed the data separately for each of the following three sessions (Fig. 2D–F): 3:00 to 7:00 P.M. (lights on, immediately preceding the lights-off period), 7:00 P.M. to 7:00 A.M. (lights off), and 7:00 A.M. to 12:00 P.M. (lights on, immediately following the lights-off period). Thus, we partitioned the locomotor activity into a single lights-off period separated by the two lights-on periods. In each of the three sessions, separate analyses were performed for male and female mice.

Figure 2.

Locomotor activity was analyzed over a 21 h period between 3:00 and 12:00 P.M. in male and female mice aged P42–P56 from the PNE, SAC, and WATER groups. The lights-off period was from 7:00 P.M. to 7:00 A.M. A–F, Hourly (A, B) or cumulative (C–F) locomotor activity measurements are shown. Both male (A) and female (B) mice in the PNE group showed significantly higher locomotor activity compared to their counterparts in the SAC and WATER groups throughout the 21 h period of observation (A–C). Activity between the SAC and WATER groups was not significantly different. When the activity was analyzed separately for the two lights-on and one lights-off sessions (C–E), PNE group showed significant increases during the lights-off period (E) and during the lights-on period immediately following (F) but not preceding (D) the lights-off period. There were no significant differences between SAC and WATER groups nor between male and female mice within any given prenatal treatment group. ANOVA and multiple comparison tests were used to test statistical significance of the experimental effects (male, n = 10–15; female, n = 10–15).

To determine whether prenatal treatment (PNE, SAC, WATER) produced differential effects based on gender (male, female) and time of day (3:00 to 7:00 P.M., 7:00 P.M. to 7:00 A.M., and 7:00 A.M. to 12:00 P.M.), we performed a three-way ANOVA. The analysis focused on three main effects (prenatal treatment, gender, and time), three two-way interactions (prenatal treatment by gender, prenatal treatment by time, and gender by time), and one three-way interaction (gender by prenatal treatment by time). Although the three-way interaction was not significant (F(4, 228) = 1.088, p = 0.36), we found statistically significant main effects of prenatal treatment (F(2, 228) = 38.36, p < 0.0001) and time (F(2, 228) = 163.57, p < 0.0001), and a statistically significant two-way interaction between prenatal treatment and time (F(4, 228) = 13.244, p < 0.0001). The main effects of gender were not statistically significant (F(1, 228) = 5.90, p = 0.06). Pairwise comparisons revealed that male and female mice in the PNE group showed significantly higher locomotor activity compared to their counterparts in the SAC and WATER groups (for each comparison, p < 0.05). There was no significant difference between SAC and WATER groups for either males or females. The male and female mice in the PNE group showed significantly higher locomotor activity compared to their counterparts in the SAC and WATER groups for the 7:00 P.M. to 7:00 A.M. lights-off period, and the 7:00 A.M. to 12:00 P.M. lights-on period (for each comparison, p < 0.05). However, there were no significant differences in either male or female mice among the three prenatal treatment groups during the 3:00 to 7:00 P.M. lights-on period. Thus, PNE produced significant increases in spontaneous locomotor activity in male and female mice during the lights-off period (7:00 P.M. to 7:00 A.M.) and during the lights-on period immediately following the lights-off period (7:00 A.M. to 12:00 P.M.).

Since the male and female mice in the SAC group did not show significant differences in locomotor activity compared to the male and female mice in the WATER group in the analyses above, to minimize the numbers of mice subjected to experimental procedures, we did not create the WATER group for further analysis. Therefore, only the PNE and SAC groups were used in the analyses discussed hereafter.

Effects of MPH on spontaneous locomotor activity

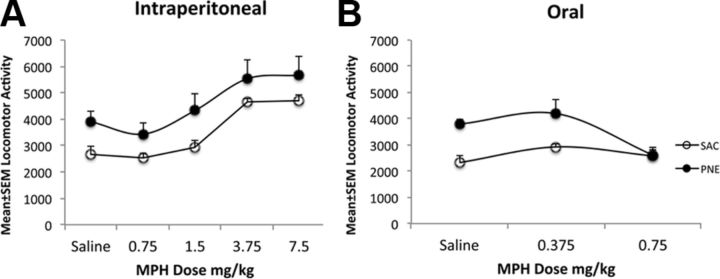

In an initial series of studies, we sought to establish a dose and route of MPH administration that influenced the hyperactivity observed in the PNE group of mice. We showed in a previous paper (Balcioglu et al., 2009) that 0.75 mg/kg MPH administered orally produced serum and brain levels of MPH that were comparable to the levels seen in human subjects given oral therapeutic doses of MPH. Therefore, we used 0.75 mg/kg MPH via the oral route of administration. For comparison, we also included 0.375 mg/kg oral dose. Since the route of MPH administration can influence its effects (Patrick and Markowitz, 1997; Gerasimov et al., 2000; Kuczenski and Segal, 2002, 2005), we also used intraperitoneal route of administration at doses of 0.75, 1.5, 3.5, or 7.5 mg/kg MPH. The analysis was performed over a 4 h period beginning at 08:00 h. Since the PNE-induced hyperactivity was comparable between male and female mice (Fig. 2), and since our limited resources did not permit us to use both the sexes in every experiment, only male mice were used in this preliminary study. The mice were placed in the testing apparatus at 8:00 A.M., a convenient time point for the experiments and also because the locomotor activity in the PNE group was significantly higher than that in the SAC or WATER groups at this time point (Fig. 2). MPH or saline was administered 1 h later, at 9:00 A.M., and the locomotor activity was recorded from 9:00 A.M. to 12:00 P.M. (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

A, B, The effects of intraperitoneal (A) or oral (B) administration of saline or MPH on locomotor activity in 42-d-old male mice in the SAC and PNE groups. Locomotor activity was recorded for 4 h. Mice in the PNE group showed significantly increased activity compared to their counterparts in the SAC group when saline was administered to both the groups either intraperitoneally (A) or orally (B). Intraperitoneal MPH did not produce significant changes in the locomotor activity in PNE group at any of the five doses (A). However, it increased locomotor activity in the SAC group at 3.75 and 7.5 mg/kg doses (A). Oral MPH administration did not affect locomotor activity in the SAC group at either dose (B). However, 0.75 mg/kg MPH significantly decreased locomotor activity in the PNE group. ANOVA and multiple comparison tests were used to test statistical significance of the experimental effects (n = 6 for each group).

As expected, locomotor activity in the PNE group of mice was higher than that in the SAC group upon saline administration, whether the saline was administered intraperitoneally (Fig. 3A) or orally (Fig. 3B). ANOVA revealed that the intraperitoneal MPH administration produced significant overall effects on locomotor activity in both the PNE and SAC groups (PNE, F(4, 19) = 3.32, p = 0.03; SAC, F(4, 25) = 22.0, p = 0.0001). A Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test revealed significant differences between each of 0, 0.75, and 1.5 mg/kg MPH versus each of 3.75 and 7.5 mg/kg MPH in the SAC group (p < 0.001 for each pairwise comparison). However, there was no significant difference between any given pair of doses in the PNE group. Thus, intraperitoneal MPH administration did not produce any effect on locomotor activity in the PNE group at any of the doses tested, whereas it increased locomotor activity at doses higher than 3.75 mg/kg in the SAC group.

ANOVA of the data on the effects of oral administration of MPH revealed that the drug administration produced significant effects on locomotor activity in the PNE group of mice (F(2, 13) = 6.51, p = 0.01), but not in the SAC group. Pairwise comparison test revealed that within the PNE group, there was no significant difference between saline and 0.375 mg/kg MPH. However, there were significant differences between saline and 0.75 mg/kg MPH as well as between 0.375 and 0.75 mg/kg MPH. Thus, 0.75 but not 0.375 mg/kg MPH produced significant decreases in locomotor activity in the PNE group whereas neither dose of MPH produced significant changes in locomotor activity in the SAC group.

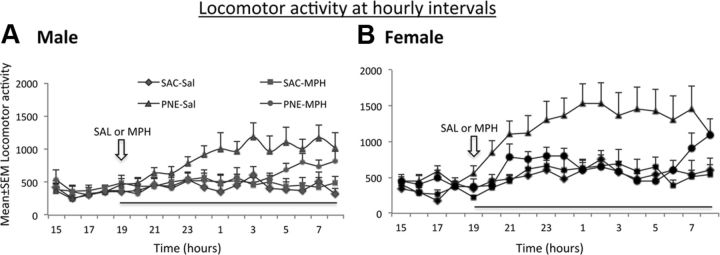

Since oral but not intraperitoneal administration of 0.75 mg/kg MPH decreased the locomotor activity in the PNE group of mice to baseline levels, and since most common therapeutic administration of MPH for the treatment of ADHD is oral, we examined in further detail the effects of oral MPH on locomotor activity over a 12 h lights-off period. The data from male and female mice in the PNE and SAC groups were analyzed separately (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

A, B, The effects of a single oral dose (0.75 mg/kg) of MPH on locomotor activity in 42-d-old mice from the PNE and SAC exposure groups. The analysis was performed separately for male (A) and female (B) mice over a period of 12 h during the lights-off period. MPH or SAL was gavaged at 7:00 P.M. (open arrows) and locomotor activity was recorded for a 12 h period (7:00 P.M. to 7:00 A.M.) from the time of MPH or saline administration until the lights were turned on. When saline was administered, both male (A) and female (B) mice in the PNE group showed significantly higher activity compared to their counterparts in the SAC group. MPH produced significant decreases in locomotor activity in both male and female mice in the PNE group such that the activity in the MPH–PNE group was not significantly different than that in the SAL–SAC group. MPH did not produce significant changes in locomotor activity in the SAC group of male or female mice. ANOVA and multiple comparison tests were used to test statistical significance of the experimental effects (female, n = 12 for each group; male, n = 8–11).

The mice were placed in the test apparatus at 1:00 P.M., and locomotor activity was recorded starting 2 h later, at 3:00 P.M., to give sufficient time for the mice to acclimatize. A single dose of MPH was administered at 19:00 h, a time point when the lights are turned off and locomotor activity in both the groups of mice tends to increase (Fig. 2A,B). The locomotor activity was monitored continuously during the entire lights-off period from 7:00 P.M. to 7:00 A.M. (Fig. 4) and analyzed at hourly intervals (Fig. 4A,B).

The cumulative locomotor activity over the entire 12:00 P.M. period (Fig. 4) was significantly influenced by the prenatal treatment and MPH administration in both the males and females (ANOVA males, F(3, 34) = 7.02, p < 0.001; females, F(3, 46) = 6.28, p < 0.001). Multiple comparison tests showed significant increases in baseline locomotor activity (i.e., even with saline administration) in the PNE group compared to SAC group in males and females, as expected. The MPH administration decreased the locomotor activity in the PNE group such that there was no significant difference between PNE–MPH and SAC–saline groups of males or females. Interestingly, MPH did not produce significant effects on locomotor activity in the SAC group in either the males or the females (p > 0.05).

The decrease in locomotor activity produced by the MPH administration was evident between 8:00 P.M. and 3:00 A.M. (i.e., ∼8 h after MPH administration) in the males, and between 7:00 P.M. and 7:00 A.M. (i.e., ∼12 h after MPH administration) in the females (Fig. 4A,B). By ∼7:00 A.M., the activity levels of MPH administered PNE group of mice began approaching the levels of saline treated PNE group in both males and females, indicating a waning of the effects of the single dose of MPH.

Dopamine and serotonin turnover

We measured the concentrations of dopamine, serotonin, DOPAC, and 5-HIAA in the frontal cortex and striatum of P42 mice from the PNE and SAC groups. Only male mice were used in these analyses. The baseline dopamine concentration in the frontal cortex was significantly higher in the PNE group compared to the SAC group (Table 1; t = 2.94, df = 29, p < 0.01). The concentration of DOPAC was not significantly different between the two groups (Table 1; t = 0.48, df = 29, p > 0.05). The dopamine turnover rate (DOPAC/DA) was significantly reduced (by ∼100%) in the PNE group compared to the SAC group (Table 1; t = 2.75, df = 30, p < 0.05). There were no statistically significant differences between the PNE and SAC groups with regard to serotonin or 5-HIAA concentrations, or serotonin turnover (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mean ± SEM values (femtomoles per milligram protein) of tissue concentrations of DA, DOPAC, 5-HT, and 5-HIAA and the turnover rates (DOPAC/DA and 5-HIAA/5-HT) in SAC or PNE mice and following saline (SAL) or methylphenidate (MPH) administration in the frontal cortex of the PNE mice

| DA | DOPAC | DOPAC/DA | 5-HT | 5-HIAA | 5-HIAA/5-HT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frontal cortexa | ||||||

| SAC | 57.9 ± 19.01 | 127.58 ± 36.13 | 2.29 ± 0.38 | 361.35 ± 61.57 | 168.54 ± 46.14 | 0.35 ± 0.07 |

| PNE | 187.7 ± 38.8** | 148.96 ± 25.85 | 1.09 ± 0.3* | 387.83 ± 46.69 | 289.66 ± 77.52 | 0.62 ± 0.14 |

| Striatuma | ||||||

| SAC | 2559.31 ± 611.92 | 254.56 ± 69.34 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 313.86 ± 62.19 | 188.63 ± 63.86 | 0.48 ± 0.13 |

| PNE | 3388.86 ± 618.03 | 258.34 ± 57.68 | 0.06 ± 0.01* | 386.78 ± 44.16 | 236.37 ± 45.75 | 0.57 ± 0.1 |

| PNEb | ||||||

| SAL | 197.31 ± 40.24 | 144.05 ± 27.13 | 0.83 ± 0.15 | 391.55 ± 50.98 | 295.05 ± 84.71 | 0.62 ± 0.15 |

| MPH | 160.91 ± 62.76 | 230.04 ± 83.25 | 1.75 ± 0.29** | 296.31 ± 60.19 | 181.92 ± 74.78 | 0.45 ± 0.12 |

aBaseline tissue concentrations in the frontal cortex and the striatum (n = 16 for each SAC or PNE).

bTissue concentrations in the frontal cortex 1 h after oral gavage of SAL (n = 15) or 0.75 mg/kg MPH (n = 13).

*p < 0.05;

**p < 0.01.

The dopamine turnover was significantly reduced (by ∼50%) in the striatum of PNE mice compared to the SAC mice (Table 1; t = 3.0, df = 28, p < 0.05). However, neither the basal dopamine nor the DOPAC concentration was significantly different between the PNE and SAC groups of mice (Table 1). Striatal concentrations of serotonin and 5-HIAA or serotonin turnover were also not significantly different between the PNE and SAC mice (Table 1).

Next we examined the effects of saline versus MPH administration on dopamine, serotonin, DOPAC and 5-HIAA concentrations as well as dopamine and serotonin turnover in the frontal cortex of P42 male PNE mice (Table 1). Saline or MPH (0.75 mg/kg) was administered via oral gavage and 30 min later the mice were sacrificed for tissue collection. MPH did not significantly alter the concentration of dopamine or DOPAC in the PNE mice (Table 1; dopamine, t = 0.5, df = 20; DOPAC, t = 0.29, df = 25; in each case, p > 0.05). Nevertheless, the dopamine turnover rate was significantly increased by the MPH administration in the PNE mice (Table 1; t = 2.9, df = 26, p < 0.01). The MPH administration did not produce statistically significant differences in serotonin or 5-HIAA concentrations or serotonin turnover (Table 1).

Regional brain volume

We compared the volumes of different brain regions between PNE and SAC groups of male mice at P42 (Table 2). We found a significant reduction in the volume of the cingulate cortex in the PNE group of mice. Volume of no other brain region showed significant differences between the PNE and SAC groups. When the regional brain volumes were normalized against cerebral hemispheric volume (regional volume divided by hemispheric volume), the cingulate cortex showed significant reduction in the PNE group compared to the SAC group. (∼20%, t = 2.1, df = 20, p < 0.05; Table 2). On the other hand, the normalized volume of the sensory-motor cortex was significantly increased (∼6%, t = 2.7, df = 20, p < 0.05; Table 2) in the PNE group compared to the SAC group.

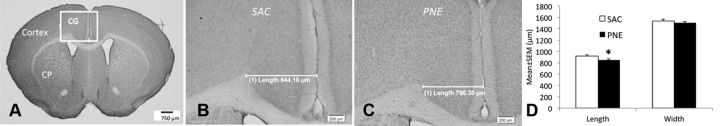

Dimensions of the cingulate cortex

The length (radial thickness) of the cingulate cortex was significantly reduced in the PNE group compared to that in the SAC group (Fig. 5; mean ± SEM, SAC, 919 ± 19 μm; PNE, 849 ± 20.0 μm; n = 6, t = 2.59; df = 10, p < 0.05), whereas the width was not significantly different between the two groups (mean ± SEM, SAC, 1539 ± 25 μm; PNE, 1504 ± 21 μm; n = 6, t = 1.05; df = 10, p > 0.05).

Figure 5.

A–C, Coronal sections of the forebrain from 42-d-old mice stained with cresyl violet. The boxed area in A shows the location of the cingulate cortex (CG). We analyzed the volume of the cingulate cortex using stereological methods in mice from the PNE and SAC exposure groups. In addition, the length (radial thickness) and width (height) of the cingulate cortex were analyzed in coronal sections representing its entire rostrocaudal extent. Representative micrographs are shown to illustrate reduced radial thickness (length) of the cingulate cortex in a mouse from the PNE group (C) compared to its counterpart from the SAC group (B). D, The decrease in length was statistically significant, whereas no statistically significant difference was found in the width between the PNE and SAC groups. *p < 0.05.

Discussion

We showed that PNE increases locomotor activity in male and female mice. PNE also increased the tissue content of dopamine and decreased the DOPAC-to-dopamine ratio (a measure of dopamine turnover) in the frontal cortex. PNE produced selective and significant decreases in cingulate cortex volume. A single oral administration of 0.75/mg MPH to mice in the PNE group significantly decreased locomotor activity to a level comparable to that in the SAC group. The MPH administration significantly increased tissue DOPAC-to-dopamine ratio, without altering the dopamine content, in the frontal cortex of the PNE group.

We used an oral nicotine exposure method because it does not involve the stresses associated with intraperitoneal injections or implantation of osmotic pumps (Rowell et al., 1983; Sparks and Pauly, 1999; Vaglenova et al., 2004; Paz et al., 2006). Moreover, nicotine delivery via drinking water produces changes in locomotor activity and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor activity that are comparable to those produced by nicotine exposure via nonoral routes (Sparks and Pauly, 1999). Since prenatal stress can alter behavior and CNS structure (Muhammad and Kolb, 2011b), the stress caused by intraperitoneal injections or implantation of osmotic pumps could introduce additional variability in the data. We began nicotine exposure of the dams 3 weeks before mating to ensure elevated serum nicotine levels at conception and tolerance of the nicotine treatment by the dams (Pauly et al., 2004).

The oral nicotine paradigm is sometimes criticized for not mimicking the peaks and valleys of plasma nicotine levels associated with cigarette smoking (Benowitz et al., 1982). Whereas it may be a valid criticism when modeling cigarette smoking in adults, whether the peaks and valleys also occur in the fetal blood and brain during maternal cigarette smoking remains unclear because of unusual nicotine pharmacokinetics in the fetus (for review, see Wickström, 2007). Furthermore, our PNE paradigm corresponds well to smokeless tobacco use by pregnant women, which is associated with sustained plasma nicotine concentrations (Benowitz et al., 1982; Hukkanen et al., 2005).

Our use of two control groups (SAC and WATER) permitted the evaluation of the effects of cross-fostering stress (Muhammad and Kolb, 2011a). Although we cross-fostered the PNE and SAC offspring, we did not cross-foster the WATER offspring. Yet there was no significant difference in body weight gain or locomotor activity (Fig. 2) between the WATER and SAC groups. Therefore, neither the saccharin treatment nor the cross-fostering stress contributed to the behavioral or body weight changes seen in the PNE group. The mice in the PNE group weighed significantly less than their counterparts in the SAC and WATER groups on P3, and, perhaps due to the cross-fostering paradigm, the body weights were not significantly different later in the postnatal period. Thus, volumetric changes in the brains of the PNE group (Table 2) were not confounded by body weight differences.

We were able to accomplish the principal objectives of our study, namely characterization of the effects of PNE on spontaneous locomotor activity, the ability of MPH to reduce it to baseline levels, and evaluation of the role of gender and circadian changes in PNE-induced locomotor activity. We found that PNE significantly elevated locomotor activity in both males and females. The peak activity occurred during the lights-off period of the circadian cycle, when the mice are naturally more “active.” ADHD also affects both males and females and the symptoms are evident during the active phase, which in humans is during the day.

A single MPH dose (0.75 mg/kg) administered orally reduced the locomotor activity to baseline levels in both males and females in the PNE group (Figs. 3B, 4). Also consistent with the effects of MPH in humans, the effect was transient, lasting for ∼10 h, after which the locomotor activity in the MPH-treated PNE mice began to increase. Interestingly, intraperitoneal administration of MPH produced remarkably different effects compared to the oral administration. First, 0.75 mg/kg intraperitoneal MPH did not produce significant effects on locomotor activity in the PNE group, whereas the same dose administered orally did. Second, intraperitoneal administration of 3.75 or 7.5 mg/kg MPH increased locomotor activity in SAC group of mice but did not affect the activity in the PNE group (Fig. 3). These data confirm that the route of MPH administration is an important factor in determining its behavioral effects (Patrick and Markowitz, 1997; Gerasimov et al., 2000; Kuczenski and Segal, 2002, 2005).

The 0.75 mg/kg MPH treatment, oral or intraperitoneal, did not affect locomotor activity in the SAC control group, suggesting that this dose of MPH had no effect on locomotor activity in “normal” mice. A number of earlier studies found that MPH increased locomotor activity in normal rodents. However, those studies used higher than 0.75 mg/kg MPH dose and administered it parenterally (Andersen et al., 2002; Bolaños et al., 2003; Brandon and Steiner, 2003; Carlezon et al., 2003; Russell et al., 2005; Sagvolden et al., 2005; Augustyniak et al., 2006). In the present study, also >3.75 mg/kg MPH administered intraperitoneally increased locomotor activity in the SAC mice, but it had no effect on the PNE mice. Thus, it appears that not only the dose and route of MPH administration but also the type of animal model (i.e., control vs PNE) can determine the effects of MPH on locomotor activity. Therefore, preclinical studies using ecologically valid animal models, clinically relevant dose and route of MPH administration stand the best chance of offering insights relevant to human ADHD.

Taken together, our findings underscore the cross-species similarities between the PNE mouse model and human ADHD, where the symptoms are evident only during the day, when the subjects are awake and active, both sexes are affected, and the effects of MPH are similar and transient, supporting the ecological validity of our preclinical model of ADHD.

A recent study (Schneider et al., 2011) examined the effects of prenatal nicotine exposure on attention and impulsivity in a rat model. The data show that both attention and impulsivity are affected by the prenatal nicotine exposure. Although we did not undertake these behavioral measurements, it is likely that attention and impulsivity are affected by the prenatal nicotine exposure in our mouse model also.

In other experiments, we examined neurochemical correlates of increased locomotor activity and its mitigation by MPH in the PNE group. We focused on frontal cortical dopamine because cortical hypodopaminergic state is considered a hallmark of ADHD and it is a therapeutic target of MPH (Kuczenski and Segal, 2001, 2005; Robbins, 2002; Seeman and Madras, 2002; Volkow et al., 2005; Arnsten, 2006). The tissue content of dopamine in the frontal cortex was elevated in the PNE group reflecting increased vesicular dopamine (intracellular stores) and/or extracellular (i.e., synaptically released) dopamine. Our methods cannot distinguish between the two compartments. The frontal cortical DOPAC-to-dopamine ratio was significantly decreased by the PNE. Since only extracellular dopamine is broken down into DOPAC, the decreased DOPAC-to-dopamine ratio could reflect reduced synaptic dopamine, i.e., a hypodopaminergic state akin to that in ADHD. MPH administration significantly increased the DOPAC-to-dopamine ratio, suggesting increased dopamine turnover, potentially due to increases in synaptic dopamine, which would be metabolized to DOPAC. Thus, PNE could have led to a frontal cortical hypodopaminergic state, which could have been offset by the MPH administration. While these data highlight the value of this PNE mouse model for ADHD research, we emphasize that a clearer understanding of the effects of PNE on dopamine release, turnover, and synaptic dopamine content requires further analysis using sophisticated techniques such as in vivo microdialysis.

In the final set of studies, we found that the volume of the cingulate cortex was decreased significantly (by ∼20%) in the PNE mice. Analysis of the length and width of the cingulate cortex revealed significant decreases in the length (radial thickness), suggesting, albeit indirectly, a decrease in the thickness of cortical layers. Whether the decrease in radial thickness reflects decreases in cell numbers, dendritic arbors, or axonal terminals remains to be examined. The cingulate cortex plays key roles in attention mechanisms (Bush et al., 1999; Bush, 2011), and the reduced cingulate volume in the PNE group of mice compares well to similar findings in ADHD subjects in our previous study (Makris et al., 2007; Makris et al., 2010). These observations raise the possibility that cingulate cortex volume may be a CNS structural biomarker of ADHD in human subjects and in our mouse model. Whether repeated MPH administration to the PNE group of mice can lead to a restoration of the cingulate cortical volume deficit (coupled with lasting downregulation of the hyperactivity) remains an open question with considerable translational significance for human ADHD. In the present study, we used only a single MPH administration, which produced only a transient reduction in hyperactivity, and did not permit us to address this issue.

In summary, the PNE mouse model described here captures the essential behavioral, neurochemical, and structural features of ADHD in humans, and behavioral and neurochemical responses to MPH treatment. This mouse model also offers valuable biomarkers for cellular and molecular studies of ADHD etiology and therapeutics.

Footnotes

This work was supported by United States Public Health Service Grants RO1DA020796, P30NS045776, and R21DA027358. We are grateful to Dr. Michael Schwarzschild for access to equipment and resources in his laboratory at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Thomas C. Burdett and Cody A. Desjardins in Dr. Schwarzschild's laboratory for assistance with high-performance liquid chromatography, Enric Navas Péres for help with histology and stereology, and the staff of the Massachusetts General Hospital's Center for Comparative Medicine for expert assistance with mouse colony management.

References

- Andersen SL, Arvanitogiannis A, Pliakas AM, LeBlanc C, Carlezon WA., Jr Altered responsiveness to cocaine in rats exposed to methylphenidate during development. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:13–14. doi: 10.1038/nn777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF. Stimulants: Therapeutic Actions in ADHD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2376–2383. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustyniak PN, Kourrich S, Rezazadeh SM, Stewart J, Arvanitogiannis A. Differential behavioral and neurochemical effects of cocaine after early exposure to methylphenidate in an animal model of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav Brain Res. 2006;167:379–382. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcioglu A, Ren JQ, McCarthy D, Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Bhide PG. Plasma and brain concentrations of oral therapeutic doses of methylphenidate and their impact on brain monoamine content in mice. Neuropharmacology. 2009;57:687–693. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Kuyt F, Jacob P., III Circadian blood nicotine concentrations during cigarette smoking. Clin Pharm Ther. 1982;32:758–764. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1982.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhide PG. Dopamine, cocaine and the development of cerebral cortical cytoarchitecture: a review of current concepts. Seminars Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Bhide PG, Woodworth KY, Faraone S. Does exposure to maternal smoking during pregnancy affect the clinical features of ADHD? Results from a controlled study. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2012;13:60–64. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.562243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolaños CA, Barrot M, Berton O, Wallace-Black D, Nestler EJ. Methylphenidate treatment during pre- and periadolescence alters behavioral responses to emotional stimuli at adulthood. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:1317–1329. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00570-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon CL, Steiner H. Repeated methylphenidate treatment in adolescent rats alters gene regulation in the striatum. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1584–1592. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G. Cingulate, frontal, and parietal cortical dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:1160–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, Frazier JA, Rauch SL, Seidman LJ, Whalen PJ, Jenike MA, Rosen BR, Biederman J. Anterior cingulate cortex dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder revealed by fMRI and the Counting Stroop. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1542–1552. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Mague SD, Andersen SL. Enduring behavioral effects of early exposure to methylphenidate in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:1330–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesselet MF. Presynaptic regulation of neurotransmitter release in the brain: facts and hypothesis. Neuroscience. 1984;12:347–375. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(84)90058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, Day NL. Developmental consequences of prenatal tobacco exposure. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22:121–125. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328326f6dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall JE, McCarthy DM, Araki KY, Sims JR, Ren JQ, Bhide PG. Dopamine receptor activation modulates GABA neuron migration from the basal forebrain to the cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3813–3822. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5124-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst M, Moolchan ET, Robinson ML. Behavioral and neural consequences of prenatal exposure to nicotine. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:630–641. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200106000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried PA, Watkinson B. Differential effects on facets of attention in adolescents prenatally exposed to cigarettes and marihuana. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2001;23:421–430. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerasimov MR, Franceschi M, Volkow ND, Gifford A, Gatley SJ, Marsteller D, Molina PE, Dewey SL. Comparison between intraperitoneal and oral methylphenidate administration: a microdialysis and locomotor activity study. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:51–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hukkanen J, Jacob P, 3rd, Benowitz NL. Metabolism and disposition kinetics of nicotine. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:79–115. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal DS. Locomotor effects of acute and repeated threshold doses of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relative roles of dopamine and norepinephrine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:876–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal DS. Exposure of adolescent rats to oral methylphenidate: preferential effects on extracellular norepinephrine and absence of sensitization and cross-sensitization to methamphetamine. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7264–7271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07264.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczenski R, Segal DS. Stimulant actions in rodents: implications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder treatment and potential substance abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1391–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris N, Biederman J, Valera EM, Bush G, Kaiser J, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS, Faraone SV, Seidman LJ. Cortical thinning of the attention and executive function networks in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:1364–1375. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris N, Seidman LJ, Valera EM, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS, Jr, Bush G, Crum K, Brown AB, Faraone SV. Anterior cingulate volumetric alterations in treatment-naive adults with ADHD: a pilot study. J Atten Disord. 2010;13:407–413. doi: 10.1177/1087054709351671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy DM, Zhang X, Darnell SB, Sangrey GR, Yanagawa Y, Sadri-Vakili G, Bhide PG. Cocaine alters BDNF expression and neuronal migration in the embryonic mouse forebrain. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13400–13411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2944-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy D, Lueras P, Bhide PG. Elevated dopamine levels during gestation produce region-specific decreases in neurogenesis and subtle deficits in neuronal numbers. Brain Res. 2007;1182:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Chen L, Jones J. Is maternal smoking during pregnancy a risk factor for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children? Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1138–1142. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.9.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Jones J. Further evidence of an association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: findings from a high-risk sample of siblings. J Clin Child Psychol. 1998;27:352–358. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2703_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad A, Kolb B. Maternal separation altered behavior and neuronal spine density without influencing amphetamine sensitization. Behav Brain Res. 2011a;223:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad A, Kolb B. Mild prenatal stress-modulated behavior and neuronal spine density without affecting amphetamine sensitization. Dev Neurosci. 2011b;33:85–98. doi: 10.1159/000324744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro HA, Seidler FJ, Schwartz RD, Baker FE, Dobbins SS, Slotkin TA. Prenatal exposure to nicotine impairs nervous system development at a dose which does not affect viability or growth. Brain Res Bull. 1989;23:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obel C, Olsen J, Henriksen TB, Rodriguez A, Jarvelin MR, Moilanen I, Parner E, Linnet KM, Taanila A, Ebeling H, Heiervang E, Gissler M. Is maternal smoking during pregnancy a risk factor for hyperkinetic disorder? Findings from a sibling design. International journal of epidemiology. 2011;40:338–345. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick KS, Markowitz JS. Pharmacology of methylphenidate, amphetamine enantiomers and pemoline in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Human Psychopharmacol. 1997;12:527–546. [Google Scholar]

- Pauly JR, Sparks JA, Hauser KF, Pauly TH. In utero nicotine exposure causes persistent, gender-dependant changes in locomotor activity and sensitivity to nicotine in C57Bl/6 mice. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2004;22:329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Ed 2. San Diego: Academic; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Paz R, Barsness B, Martenson T, Tanner D, Allan AM. Behavioral teratogenicity induced by nonforced maternal nicotine consumption. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;32:693–699. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren JQ, Jiang Y, Wang Z, McCarthy D, Rajadhyaksha AM, Tropea TF, Kosofsky BE, Bhide PG. Prenatal l-DOPA exposure produces lasting changes in brain dopamine content, cocaine-induced dopamine release and cocaine conditioned place preference. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson SA, Tizabi Y. Hyperactivity in the offspring of nicotine-treated rats: Role of the mesolimbic and nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathways. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;47:331–337. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW. ADHD and addiction. Nat Med. 2002;8:24–25. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell PP, Hurst HE, Marlowe C, Bennett BD. Oral administration of nicotine: its uptake and distribution after chronic administration to mice. J Pharmacol Methods. 1983;9:249–261. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(83)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell VA, Sagvolden T, Johansen EB. Animal models of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behav Brain Funct. 2005;1:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagvolden T, Russell VA, Aase H, Johansen EB, Farshbaf M. Rodent models of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1239–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T, Ilott N, Brolese G, Bizarro L, Asherson PJ, Stolerman IP. Prenatal exposure to nicotine impairs performance of the 5-choice serial reaction time task in adult rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1114–1125. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman P, Madras B. Methylphenidate elevates resting dopamine which lowers the impulse-triggered release of dopamine: a hypothesis. Behav Brain Res. 2002;130:79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00435-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA. Cholinergic systems in brain development and disruption by neurotoxicants: nicotine, environmental tobacco smoke, organophosphates. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;198:132–151. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Cho H, Whitmore WL. Effects of prenatal nicotine exposure on neuronal development: selective actions on central and peripheral catecholaminergic pathways. Brain Res Bull. 1987;18:601–611. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(87)90130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks JA, Pauly JR. Effects of continuous oral nicotine administration on brain nicotinic receptors and responsiveness to nicotine in C57Bl/6 mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;141:145–153. doi: 10.1007/s002130050818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thapar A, Rice F, Hay D, Boivin J, Langley K, van den Bree M, Rutter M, Harold G. Prenatal smoking might not cause attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence from a novel design. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66:722–727. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaglenova J, Birru S, Pandiella NM, Breese CR. An assessment of the long-term developmental and behavioral teratogenicity of prenatal nicotine exposure. Behav Brain Res. 2004;150:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Ding YS. Imaging the effects of methylphenidate on brain dopamine: new model on its therapeutic actions for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1410–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickström R. Effects of nicotine during pregnancy: human and experimental evidence. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2007;5:213–222. doi: 10.2174/157015907781695955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]