Abstract

ClC-3 is a member of the ClC voltage-gated chloride (Cl−) channel superfamily. Recent studies have demonstrated the abundant expression and pleiotropy of ClC-3 in cardiac atrial and ventricular myocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. ClC-3 Cl− channels can be activated by increase in cell volume, direct stretch of β1-integrin through focal adhesion kinase and many active molecules or growth factors including angiotensin II and endothelin-1-mediated signaling pathways, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II and reactive oxygen species. ClC-3 may function as a key component of the volume-regulated Cl− channels, a superoxide anion transport and/or NADPH oxidase interaction partner, and a regulator of many other transporters. ClC-3 has been implicated in the regulation of electrical activity, cell volume, proliferation, differentiation, migration, apoptosis and intracellular pH. This review will highlight the major findings and recent advances in the study of ClC-3 Cl− channels in the cardiovascular system and discuss their important roles in cardiac and vascular remodeling during hypertension, myocardial hypertrophy, ischemia/reperfusion, and heart failure.

Keywords: ClC, chloride channels, heart disease, apoptosis, oxidative stress, remodeling, hypertension

Introduction

ClC-3 is a member of the ClC voltage-gated chloride (Cl−) channel gene superfamily1. In 1994, ClC-3 cDNA was first cloned from rat kidney by Kawasaki et al using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) cloning strategy2. ClC-3 is also abundantly expressed in brain3, lung, kidney4, heart5, 6, and vasculature7 of many species, including human4, 6, 8. Expression of the cloned rat ClC-3 yielded an outwardly-rectifying Cl− current in Xenopus oocytes2 and in somatic cell lines3, which was completely inhibited by activation of protein kinase C (PKC)2 or increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration3. The Cl− currents produced by expression of cardiac ClC-3 in mammalian cells are also outwardly-rectifying and inhibited by PKC and share many biophysical and pharmacological characteristics with the volume-regulated Cl− currents (ICl, vol) in cardiac myocytes5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, vascular smooth muscle cells7 and many other cell types14, 15, 16. ClC-3 Cl− channels can be activated also by direct stretch of β1-integrin through focal adhesion kinase and many active molecules or growth factors including angiotensin II (Ang II) and endothelin-1 mediated signaling pathways17, 18, 19, 20, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)21 and reactive oxygen species22, 23. In the past 15 years, accumulated experimental data has shown that ClC-3 proteins are expressed in sarcolemmal membranes and intracellular organelles of cardiac myocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells24, 25, 26, 27. Numerous studies have demonstrated the pleiotropy of ClC-3 in many cellular functions, including 1) as a key component of the volume-regulated Cl− channels (VRCCs) to strengthen the regulatory volume decrease (RVD) and protect cardiac myocytes from excessive increase in cell volume during hypoxia, ischemia, or hypertrophy; 2) as a regulator of the redox signaling pathway through interaction with NADPH oxidase (Nox) and/or as a superoxide anion (O2·−) transporter to improve myocyte viability against oxidative damage; 3) as an anti-apoptotic mechanism through regulation of cell volume and intracellular pH; and 4) as a regulator of other transport functions involved in the etiology of myocardial damage, heart failure, and hypertension (Figure 1).

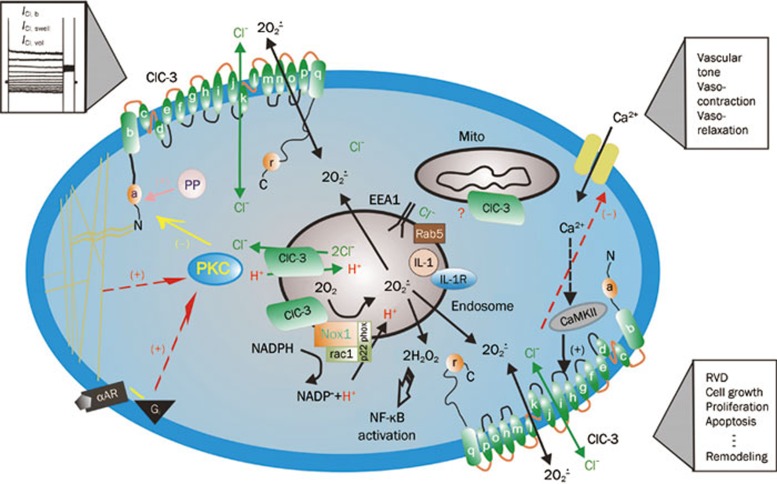

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of regulation and function of ClC-3 Cl− channels in cardiac myocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells. ClC-3, a member of voltage-gated ClC Cl− channel family, encodes Cl− channels in cardiac myocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells that are volume regulated (ICl, vol) and can be activated by cell swelling (ICl, swell) induced by exposure to hypotonic extracellular solutions or possibly membrane stretch. ICl, b is a basally activated ClC-3 Cl− current. Membrane topology model (α-helices a–r) for ClC-3 is modified from Dutzler et al100. ClC-3 proteins are expressed on both sarcolemmal membrane and intracellular organelles including mitochondria (mito) and endosomes. The proposed model of endosome ion flux and function of Nox1 and ClC-3 in the signaling endosome is modified from Miller Jr et al101. Binding of IL-1β or TNF-α to the cell membrane initiates endocytosis and formation of an early endosome (EEA1 and Rab5), which also contains NADPH oxidase subunits Nox1 and p22phox, in addition to ClC-3. Nox1 is electrogenic, moving electrons from intracellular NADPH through a redox chain within the enzyme into the endosome to reduce oxygen to superoxide. ClC-3 functions as a chloride-proton exchanger, required for charge neutralization of the electron flow generated by Nox1. The ROS generated by Nox1 result in NF-κB activation. Both ClC-3 and Nox1 are necessary for generation of endosomal ROS and subsequent NF-κB activation by IL-1β or TNF-α in VSMCs. PKC, protein kinase C; PP, serine-threonine protein phosphatases; α-AR, α-adrenergic receptor; Gi, heterodimeric inhibitory G protein; Nox: NADPH oxidase; CaMKII: Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II; (+) stimulation; (–) inhibition.

This review will highlight the major findings and recent advances in the study of ClC-3 Cl− channels in the cardiovascular system and discuss their important roles in cardiac and vascular remodeling during hypertension, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion, hypertrophy, and heart failure.

ClC-3 and VRCCs

Under osmotic, metabolic, and/or oxidative stress mammalian cells are able to precisely maintain their size through the regulated loss or gain of intracellular ions or other osmolytes to avoid excessive alterations of cell volume that may jeopardize structural integrity and a variety of cellular functions28, 29, 30, 31. Even under physiological conditions, volume constancy of any mammalian cell is challenged by the transport of osmotically active substances across the cell membrane and alterations in cellular osmolarity by metabolism28. Thus, the continued operation of cell volume regulatory mechanisms, such as activation of VRCCs, is required for cell volume homeostasis in many mammalian cells, including cardiac myocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)12, 24, 32, 33. Acute increase in cell volume (or cell swelling) initiates the regulatory volume decrease (RVD) process to bring the cells back to their initial volume, which is achieved by the opening of VRCCs and other channels and transporters mediating Cl-, K+, and taurine efflux that in turn drives water exit28.

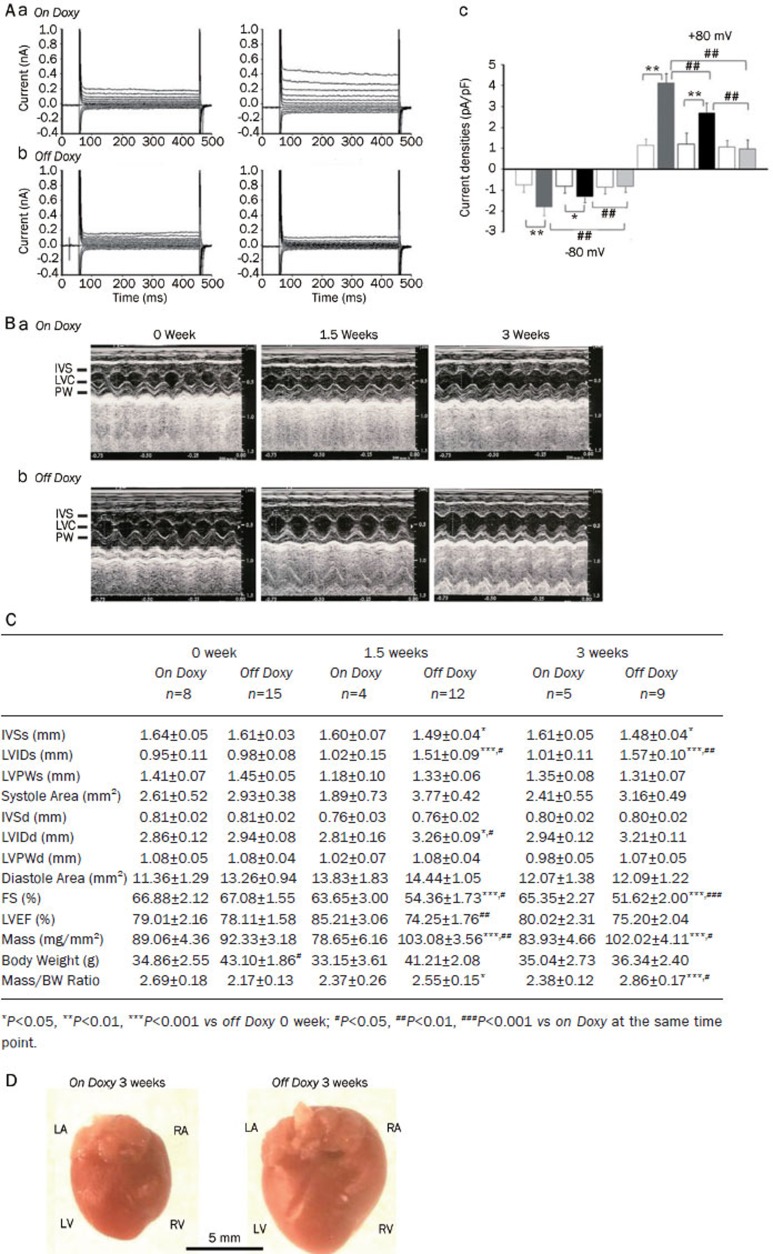

Although the exact identification of the protein(s) responsible for VRCCs has proven to be elusive, ClC-3 has been proposed to be the molecular correlate of the native VRCCs in cardiac myocytes5 and VSMCs7. But the role of ClC-3 as a constituent of native VRCCs became an issue of debate owing to inconsistent and conflicting data collected from some laboratories34, 35, 36. Specially, the presence of the native VRCCs in two different cell types from the global ClC-3 knockout (Clcn3−/−) mice35 casts considerable doubt on the role of ClC-3 as a molecular component of VRCCs. However, later additional experiments using Clcn3−/− mice revealed that the properties of native VRCCs in the Clcn3−/− heart were significantly altered and the expression of a variety of membrane proteins other than ClC-3 was also markedly changed, raising fundamental questions about the usefulness of the Clcn3−/− mouse model to assess ClC-3 function37. A series of recent independent studies from many laboratories further strongly corroborated the hypothesis that ClC-3 encoded a key component of the native VRCCs in a variety cell types ranging from normal cardiac myocytes to cancer cells16, 20, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46. Knockdown of ClC-3 by siRNA41, 42, 47, shRNA48, 49, and antisense20, 39, 43, 45 and intracellular dialysis of anti-ClC-3 antibody (Ab)16, 37, 38, 44, 45, 46 all consistently eliminated VRCC currents in many types of cells. A recent study using the inducible heart-specific ClC-3 knockout mouse found that a time-dependent inactivation of ClC-3 gene expression was correlated with an elimination of the endogenous VRCCs (Figure 2) and significantly compromised cardiac function (Figure 2)50. Therefore, ClC-3 remains a strong and viable candidate for VRCCs in the heart and may contribute to normal cardiac function.

Figure 2.

Effects of inducible heart-specific ClC-3 knockout on cardiac volume-regulated Cl− current (VRCC) and heart function. (A) Representative current traces in isotonic condition and under hypotonic challenge recorded in freshly isolated atrial myocytes from the inducible heart-specific ClC-3 knockout (doxyhsClC-3−/−) mice with doxycycline (on Doxy) in the diet (panel a), or after withdraw of doxycycline (off Doxy) from the diet for 3 weeks (panel b). (c) Summary of VRCC current densities in isotonic and hypotonic solutions, recorded at +80 mV and −80 mV. Open boxes, under isotonic conditions; filled boxes under hypotonic conditions; Grey boxes, on doxycycline; black boxes, off doxycycline 1.5 weeks; pale grey boxes, off doxycycline for 3 weeks. **P<0.01, hypotonic-induced VSOAC current densities compared to isotonic conditions. ##P<0.01, hypotonic-induced VSOAC current densities compared between on Doxy and 1.5 weeks off Doxy, and between 1.5 and 3 weeks off Doxy using ANOVA. (B) Representative M-mode echocardiography from on Doxy (a) and off Doxy (b) mice. (C) Time-dependent changes in M-mode echocardiogram of age-matched on Doxy or off Doxy for 1.5 and 3 weeks. (D) Comparison of hearts isolated from age-matched (11-week old) doxyhsClcn3−/− mice on Doxy or off Doxy for 3 weeks. Hearts were cleaned up blood and connective tissues and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. (Adapted from Xiong et al50).

VRCCs and ClC-3 in cardioprotection induced by ischemic preconditioning (IPC)

Ischemic preconditioning (IPC) is a phenomenon in which brief episodes of ischemia dramatically reduce myocardial infarction caused by a subsequent sustained ischemia51. IPC has an early phase (lasting 1–2 h) and a late phase or “second window” (lasting 24–72 h) of protection52. It has been reported that the block of ICl, swell in rabbit cardiac myocytes inhibits IPC by brief ischemia, hypo-osmotic stress53, 54 and adenosine receptor agonists55. These studies were solely based on the use of several Cl− channel blockers, such as anthracene-9-carboxylic acid (9-AC) and 4-acetamide-4′-isothiocyanatostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (SITS). These pharmacological tools lack specificity to a particular Cl− channel in the heart and may also act on other ion channels or transporters56, 57. Therefore the causal role of ICl, swell in IPC has been very difficult to be confirmed58. To specifically test whether the VRCCs are indeed involved in IPC, we have recently established in vitro and in vivo models of early IPC and late IPC in ClCn3−/− mice. Our preliminary results indicate that targeted inactivation of ClC-3 gene prevented protective effects of late IPC but not of early IPC, suggesting that ClC-3/VRCCs may contribute differently to early and late IPC59, 60. The underlying mechanisms for these differential effects are currently unknown. Recent reports, however, suggest that VRCCs and ClC-3 may play an important role in apoptosis61 and inflammation62. Cl− channel blockers DIDS and NPPB were as potent as a broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor in preventing apoptosis and elevation of caspase-3 activity and improved cardiac contractile function after ischemia and in vivo reperfusion63. Transgenic mice overexpressing Bcl-2 in the heart had significantly smaller infarct size and reduced apoptosis of myocytes after ischemia and reperfusion64. It has been shown that Bcl-2 induces up-regulation of ICl, vol by enhancing ClC-3 expression in human prostate cancer epithelial cells65. Cell shrinkage is an integral part of apoptosis, suggesting that ICl,vol and ClC-3 might be intimately linked to apoptotic events through regulation of cell volume homeostasis61, 65, 66.

VRCCs and ClC-3 in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure

Structural remodeling of myocardial hypertrophy and dilated cardiomyopathy involves oxidative stress and hypertrophic cell volume increase or dilated myocyte membrane stretch, which alters cell volume homeostasis and many cellular functions including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. ICl, swell is persistently activated in ventricular myocytes from a canine pacing-induced dilated cardiomyopathy model67. Using the perforated patch-clamp technique, Clemo et al found that, even in isotonic solutions, a large 9-AC-sensitive, outwardly rectifying Cl− current was recorded in failing cardiac myocytes but not in normal cardiac myocytes. Graded hypotonic cell swelling (60%–90% hypotonic) failed to activate additional current while graded hypertonic cell shrinkage caused an inhibition of the “basal” Cl− current in failing myocytes. Moreover, the maximum current density of the ICl, swell in failing myocytes was about 40% greater than that in osmotically swollen normal myocytes. Constitutive activation of ICl, swell is also observed in several other animal models of heart failure, such as a rabbit aortic regurgitation model of dilated cardiomyopathy68, a dog model of heart failure caused by myocardial infarction69, and a mouse model of myocardial hypertrophy by aorta binding70. In human atrial myocytes obtained from patients with right atrial enlargement and/or elevated left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, a tamoxifen sensitive ICl, swell was also found to be persistently activated67. Therefore, it is possible that persistent activation of ICl, swell is a common response of cardiac myocytes to hypertrophy or heart failure-induced remodeling.

The mechanism for persistent activation of ICl, swell in hypertrophied or failing cardiac myocytes is still not clear. Perhaps the increase in cell volume caused by hypertrophy and the stretch of cell membrane caused by dilation are both involved in the activation of ICl, swell. Alternatively, the persistent activation of ICl, swell may be caused by signaling cascades activated during hypertrophy independent of changes in cell length and volume, or both. ICl, swell could be activated by direct stretch of β1-integrin through focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and/or Src49. Mechanical stretch of myocytes also releases Ang II, which binds to AT1 receptors (AT1R) and stimulates FAK and Src in an autocrine-paracrine loop. A recent study by Browe and Baumgarten suggests that the stretch of β1-integrin in cardiac myocytes activates ICl, swell by activating AT1R and NADPH oxidase and, thereby, producing reactive oxygen species (ROS). In addition, a potent NADPH oxidase inhibitor, diphenyleneiodonium (DPI), and a structurally unrelated NADPH oxidase inhibitor, 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF), rapidly and completely blocked both background and stretch-activated Cl− currents in cardiac myocytes19. Therefore, NADPH oxidase may be intimately coupled to the channel responsible for ICl, vol, providing a second regulatory pathway for this channel through membrane stretch or oxidative stress19. This finding is very important for further understanding of the mechanism for hypertrophy activation of ICl, swell and ClC-3 channels and their relationship with hypertrophy and heart failure as it is very well known that Ang II plays a crucial role in myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure71. Interestingly, Miller and colleagues recently found that Cl− channel inhibitors and knockout of ClC-3 abolished cytokine-induced generation of ROS in endosomes and ROS-dependent NF-κB activation in vascular smooth muscle cells37, suggesting a potential close interaction between NADPH oxidase and ClC-3 (Figure 1). In human corneal keratocytes and human fetal lung fibroblasts ClC-3 knockdown by a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) significantly decreased VRCC and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)-activated Cl− current (ICl,LPA) in the presence of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) compared with controls, whereas ClC-3 overexpression resulted in increased ICl, LPA in the absence of TGF-β172. ClC-3 knockdown also resulted in a reduction of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) protein levels in the presence of TGF-β1, whereas ClC-3 overexpression increased α-SMA protein expression in the absence of TGF-β1. In addition, keratocytes transfected with ClC-3 shRNA had a significantly blunted regulatory volume decrease response following hyposmotic stimulation compared with controls. These data not only confirm that ClC-3 is important in VRCC function and cell volume regulation, but also provides new insight into the mechanism for the ClC-3-mediated fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition15.

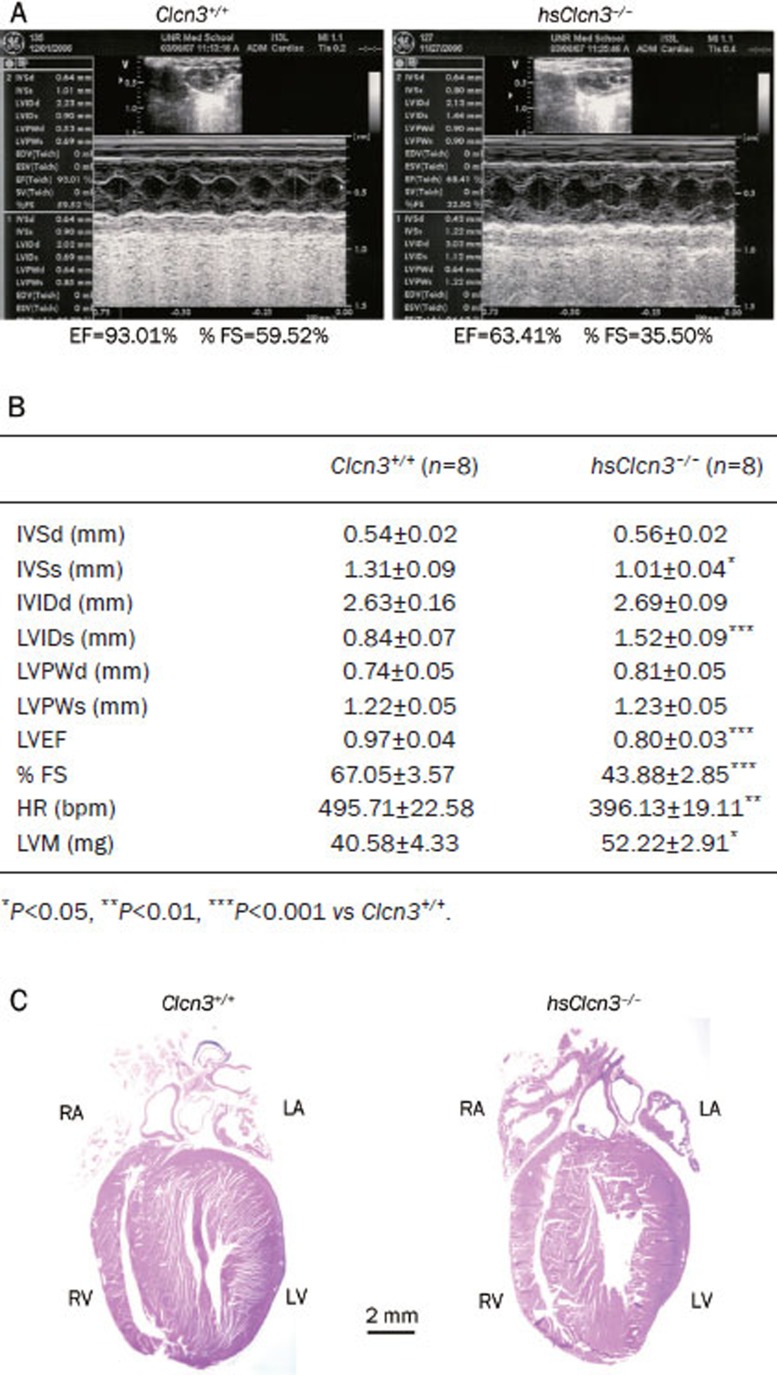

The functional and clinical significance of VRCCs in the hypertrophied and dilated heart is currently unknown. Using a mouse aortic binding model of myocardial hypertrophy, we have found that globally targeted disruption of ClC-3 gene (ClCn3−/−) accelerated the development of myocardial hypertrophy and the discompensatory process, suggesting that activation of ICl, vol might be important in the adaptive remodeling of the heart during pressure overload73. Interestingly, heart failure was found to be accompanied by a reduced ICl, vol density in rabbit cardiac myocytes43. Our recent studies on the conditional heart-specific ClC-3 knockout (hsClcn3−/−) mice (Figure 3) support the crucial functional role of ClC-3 channels in the adaptive remodeling of the heart against pressure overload72. As shown in Figure 3, echocardiography revealed marked signs of myocardial hypertrophy (a significant increase in left ventricular mass LVM) and heart failure (a significant increase in LVIDs and reduction in IVSs, LVEF, and %FS) in the hsClcn3−/− mice compared to their age-matched wild-type control mice (Figure 3B). In addition, both left and right atria were significantly enlarged (Figure 3C). These data strongly suggest that ClC-3 may play an important role in maintaining normal structure and function of the mammalian heart.

Figure 3.

Echocardiography of cardiac function of wild type and heart-specific ClC-3 knockout mice. (A) Representative M-mode echocardiography from wild-type (Clcn3+/+; left) and heart-specific ClC-3 knockout (hsClcn3−/−; right) mice. (B) Echocardiographic measurements in Clcn3+/+ and hsClcn3−/− mice. IVSd, interventricular septum thickness at the end of diastole; LVIDd, left ventricular (LV) dimension at the end of diastole; LVPWd, LV posterior wall thickness at the end of diastole; IVSs, interventricular septum thickness at the end of systole; LVIDs, LV dimension at the end of systole; LVPWs, LV posterior wall thickness at the end of systole; LVEP, calculated LV ejection fraction; %FS, LV fractional shortening; Estimated LV mass, LVM (mg)=1.05[(IVS+LVID+LVPW)3–(LVID)3], where 1.05 is the specific gravity of the myocardium. (C) Single longitudinal section (8 μm) of hearts to demonstrate all four heart chambers. Longitudinal were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Bar=2 mm) (Ye L and Duan DD. unpublished data).

VRCCs and ClC-3 in electrophysiology and electrical remodeling

Activation of VRCCs is expected to produce depolarization of the resting membrane potential and significant shortening of action potential duration (APD) because of its strong outwardly rectifying property5, 11, 24, 74, 75. The Cl− current through the VRCCs under basal or isotonic conditions is small10, 11, 76 but can be further activated by stretching of the cell membrane by inflation77 or direct mechanical stretch of membrane β1-integrin78 and/or cell swelling induced by exposure to hypoosmotic solutions5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13. The consequences of activation of ICl, vol are very complex. It may be detrimental, beneficial, or both simultaneous in different parts of the heart, depending on environmental influences.

Because cardiac myocytes swell during hypoxia and ischemia, and the washout of hyperosmotic extracellular fluid after reperfusion induces further cell swelling, activation of VRCCs may contribute to APD shortening and arrhythmias induced by hypoxia, ischemia and reperfusion79. Shortening of APD and, therefore, the effective refractory period (ERP) reduces the length of the conducting pathway needed to sustain reentry (wavelength). In principle, this favors the development of atrial fibrillation (AF) or ventricular fibrillation (VF), depending on the presence of multiple reentrant circuits or rotating spiral waves. Activation of ICl, vol may slow or enhance the conduction of early extrasystoles, depending on the timing. In guinea-pig heart, hypo-osmotic solution shortened APD and increased APD gradients between right and left ventricles. In burst stimulation-induced VF, exposure to hypo-osmotic solution increased VF frequencies, transforming complex fast Fourier transformation spectra to a single dominant high frequency on the left but not the right ventricle19. Perfusion with the VRCC blocker indanyloxyacetic acid-94 reversed organized VF to complex VF with lower frequencies, indicating that VRCC underlies the changes in VF dynamics. Consistent with this interpretation, ClC-3 channel protein expression is 27% greater on left than right ventricles, and computer simulations showed that insertion of ICl, vol transformed complex VF to a stable spiral. Therefore, activation of ICl, vol has a major impact on VF dynamics by transforming random multiple wavelets to a highly organized VF with a single dominant frequency.

In the case of myocardial hypertrophy and heart failure, ionic remodeling is one of the major features of pathophysiological changes80. Under these conditions, ICl, vol is constitutively active69. The persistent activation of ICl,vol may limit the APD prolongation and make it more difficult to elicit early after depolarization (EAD). Indeed, in myocytes from failing hearts, blocking ICl, vol by tamoxifen significantly prolonged APD and decreased the depolarizing current required to elicit EAD by about 50%. And hyper-osmotic cell shrinkage, which also inhibits ICl, vol, was almost equivalent to the effect of tamoxifen on APD and EAD in these myocytes79. It has been shown that mechanical stretching or dilation of the atrial myocardium is able to cause arrhythmias. Since ICl, vol was also found in sino-atrial (S-A) nodal cells, VRCCs may serve as a mediator of mechanotransduction and play a significant role in the pacemaker function if they act as the stretch-activated channels in these cells79, 81. Baumgarten's laboratory has recently demonstrated that ICl, vol in ventricular myocytes can be directly activated by mechanical stretch through selectively stretching β1-integrins with mAb-coated magnetic beads19, 79. Although it has been suggested that stretch and swelling activate the same anion channel in some non-cardiac cells, further study is needed to determine whether this is true in cardiac myocytes and VSMCs.

VRCC and ClC-3 in vasculature and hypertensive vascular remodeling

It has been demonstrated that VRCCs and ClC-3 are expressed in aortic and pulmonary VSMCs of human and several other speicies20, 82, 83 and have been implicated in a number of vital cellular functions including vascular myogenic tone, cell volume regulation, cell proliferation and apoptosis7, 26, 61, 84.

Membrane stretch or increases in transmural pressure cause contraction of vascular smooth muscle cells, ie, myogenic response85. Early studies revealed that the myogenic response was associated with membrane depolarization86. Ion channels sensitive to mechanical stimuli have been suggested to serve as the sensor element of the myogenic response of vascular smooth muscle. Mechano-sensitive Cl− channels and VRCCs have been observed in vascular smooth muscle cells7, 87 and a pressure-induced Cl− efflux was reported88. Activation of VRCCs and ClC-3 has been postulated to participate in the myogenic response7, 84, 86, 87, such as in the membrane depolarization and contraction mediated by activation of α1-adrenoceptors and vascular wall distension due to increased transmural pressure89. However, convincing functional evidence for the functional role of VRCCs or ClC-3 in myogenic response and myogenic tone is still lacking due to the lack of specific Cl− channel blockers90. Further study using the ClC-3 knockout or transgenic mice may provide more insights into the functional role of ClC-3 and VRCCs in the regulation of myogenic response to mechanical stretch.

Arterial VSMC proliferation is a key event in the development of hypertension-associated vascular disease83. Recent accumulating evidence suggests an important role of ClC-3 and VRCCs in the regulation of cell proliferation induced by numerous mitogenic factors61. The magnitude of VRCC currents in actively growing VSMCs is higher than in growth-arrested or differentiated VSMCs, suggesting that VRCCs may be important for VSMC proliferation91. Antisense oligonucleotide-mediated downregulation of ClC-3 dramatically inhibits cell proliferation of rat aortic VSMCs20. A recent study found that static pressure increased VRCCs and ClC-3 expression and promoted rat aortic VSMC proliferation and cell cycle progression83. Inhibition of VRCCs with pharmacological blockers (such as DIDS or the NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI) or knockdown of ClC-3 with ClC-3 antisense oligonucleotide transfection attenuated pressure evoked cell proliferation and cell cycle progression. Static pressure enhanced the production of ROS in aortic smooth muscle cells. DPI or apocynin pretreatment inhibited pressure-induced ROS production as well as cell proliferation. Furthermore, DPI or apocynin attenuated the pressure-induced upregulation of ClC-3 protein and VRCC current. These data suggest that VRCCs may play a critical role in static pressure-induced cell proliferation and cell cycle progression. Therefore, VRCCs may be of unique therapeutic importance for treatment of hypertension attendant vascular complications.

Cerebral resistance arteries undergo remodeling of the vascular walls during chronic hypertension, which is caused by the coordination of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, endothelial cell dysfunction, inflammation and fibrosis. A very recent study demonstrated that the expression of ClC-3 and VRCC activity were increased in basilar artery during hypertension and simvastatin, an inhibitor of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase widely used in clinics for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia, normalized the upregualtion of ClC-392. Furthermore, simvastatin ameliorated hypertension-caused cerebrovascular remodeling through inhibition of VRCCs and ClC-3 and cell proliferation92. These effects of simvastatin were abolished by pretreatment with mevalonate or geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate. In addition, Rho A inhibitor C3 exoenzyme and Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 both reduced cell proliferation and activation of VRCCs. ClC-3 overexpression decreased the suppressive effect of simvastatin on endothelin-1 and hypoosmolarity-induced cell proliferation. These results provided novel mechanistic insight into the beneficial effects of statins in the treatment of hypertension and stroke through an inhibition of ClC-3 and VRCC function.

ClC-3 and superoxide transport and interaction with NADPH oxidase

ROS has been implicated in cellular signaling processes as well as a cause of oxidative stress-induced cell proliferation93. One of the major sources of ROS in the heart and vasculature is through one or more isoforms of the phagocytic enzyme NADPH oxidase, a membrane-localized protein which generates the superoxide (O2·−) anion on the extracellular surface of the plasma membrane (Figure 1). As a charged and short lived anion, it is believed that O2·− flux is insufficient to initiate intracellular signaling due to the combination of poor permeability through the phospholipid bilayer94 and a rapid dismutation to its uncharged and more stable derivative, hydrogen peroxide95, 96. However, recent evidence has indicated discrete signaling roles for both O2 and H2O297.

In response to monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension the expression of ClCn3 gene was upregulated in rat pulmonary artery98. In canine cultured pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) incubated with inflammatory mediators Clcn3 gene was also upregulated98. Overexpression of ClC-3 in PASMCs enhanced viability of the cells against H2O2, thus suggesting that ClC-3 may improve the resistance of VSMCs to ROS in an environment of elevated inflammatory cytokines in hypertensive pulmonary arteries98. It was found that extracellular O2·−, but not H2O2, led to Ca2+ signaling and apoptosis in pulmonary endothelial cells99. This indicates that extracellular O2·− produced by NADPH oxidase or other sources either crosses the plasma membrane or modifies cell surface proteins to mediate cell signaling (Figure 1).

Recently, Hawkins et al studied the transmembrane flux of O2·− in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells17. Application of an extracellularbolus of O2·− resulted in rapid and concentration-dependent transient O2·−-sensitive fluorophore hydroethidine (HE) oxidation that was followed by a progressive and nonreversible increase in nuclear HE fluorescence. These fluorescence changes were inhibited by superoxide dismutase (SOD), and the Cl− channel blocker DIDS, and selective silencing of ClC-3 by treatment with siRNA. Extracellular O2·− triggered Ca2+ release, in turn triggered mitochondrial membrane potential alterations that were followed by mitochondrial O2·− production and cellular apoptosis. These “signaling” effects of O2·− were prevented by DIDS, by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin and by chelation of intracellular Ca2+. This study demonstrates that O2·− flux across the endothelial cell plasma membrane occurs through ClC-3 channels and induces intracellular Ca2+ release, which activates mitochondrial O2·− generation. These and other studies suggest that activation of ClC-3 may indeed play a role in cell proliferation, growth, volume regulation and apoptosis of VSMCs.

Conclusion

Regulation of ClC-3 functions in the cardiovascular system is emerging as a novel and important mechanism for the electrical and structural remodeling of the heart and vasculature. However, the integrated function of ClC-3 as a key component of VRCC and Nox1 and as a transport of superoxide needs to be further explored. Although specific gene targeting and transgenic approaches have been proven very powerful for specifically addressing the questions, it will be ideal if specific compounds for ClC-3 can be developed as pharmacological tools to answer these questions and to develop drugs targeting ClC-3 as novel therapeutic tools for the treatment of many cardiac and vascular diseases such as myocardial hypertrophy, ischemia, heart failure, and hypertension.

Acknowledgments

The research is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL63914 and HL106256), National Center of Research Resources (NCRR, P20RR15581), and American Diabetes Association Innovation Award (#07-8-IN-08).

References

- Jentsch TJ. CLC chloride channels and transporters: from genes to protein structure, pathology and physiology. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;43:3–36. doi: 10.1080/10409230701829110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki M, Suzuki M, Uchida S, Sasaki S, Marumo F. Stable and functional expression of the CIC-3 chloride channel in somatic cell lines. Neuron. 1995;14:1285–91. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki M, Uchida S, Monkawa T, Miyawaki A, Mikoshiba K, Marumo F, et al. Cloning and expression of a protein kinase C-regulated chloride channel abundantly expressed in rat brain neuronal cells. Neuron. 1994;12:597–604. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90215-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S, Uchida S, Kawasaki M, Adachi S, Marumo F. ClC family in the kidney. Jpn J Physiol. 1994;44:S3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Winter C, Cowley S, Hume JR, Horowitz B. Molecular identification of a volume-regulated chloride channel. Nature. 1997;390:417–21. doi: 10.1038/37151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton FC, Hatton WJ, Rossow CF, Duan D, Hume JR, Horowitz B. Molecular distribution of volume-regulated chloride channels (ClC-2 and ClC-3) in cardiac tissues. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H2225–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.5.H2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki J, Duan D, Janiak R, Kuenzli K, Horowitz B, Hume JR. Functional and molecular expression of volume-regulated chloride channels in canine vascular smooth muscle cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;507:729–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.729bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsani G, Rugarli EI, Taglialatela M, Wong C, Ballabio A. Characterization of a human and murine gene (CLCN3) sharing similarities to voltage-gated chloride channels and to a yeast integral membrane protein. Genomics. 1995;27:131–41. doi: 10.1006/geno.1995.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du XY, Sorota S. Cardiac swelling-induced chloride current depolarizes canine atrial myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H1904–16. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.4.H1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Fermini B, Nattel S. Alpha-adrenergic control of volume-regulated Cl− currents in rabbit atrial myocytes. Characterization of a novel ionic regulatory mechanism. Circ Res. 1995;77:379–93. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Hume JR, Nattel S. Evidence that outwardly rectifying Cl− channels underlie volume-regulated Cl− currents in heart. Circ Res. 1997;80:103–13. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Cowley S, Horowitz B, Hume JR. A serine residue in ClC-3 links phosphorylation-dephosphorylation to chloride channel regulation by cell volume. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:57–70. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorota S. Swelling-induced chloride-sensitive current in canine atrial cells revealed by whole-cell patch-clamp method. Circ Res. 1992;70:679–87. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick GM, Bradley KK, Horowitz B, Hume JR, Sanders KM. Functional and molecular identification of a novel chloride conductance in canine colonic smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1998;275:C940–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.4.C940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermoso M, Satterwhite CM, Andrade YN, Hidalgo J, Wilson SM, Horowitz B, et al. ClC-3 is a fundamental molecular component of volume-sensitive outwardly rectifying Cl− channels and volume regulation in HeLa cells and Xenopus laevis oocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40066–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205132200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GX, Hatton WJ, Wang GL, Zhong J, Yamboliev I, Duan D, et al. Functional effects of novel anti-ClC-3 antibodies on native volume-sensitive osmolyte and anion channels in cardiac and smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1453–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00244.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins BJ, Madesh M, Kirkpatrick CJ, Fisher AB. Superoxide flux in endothelial cells via the chloride channel-3 mediates intracellular signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2002–12. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiramatsu M, Furukawa T, Sawanobori T, Hiraoka M. Ion channel remodeling in cardiac hypertrophy is prevented by blood pressure reduction without affecting heart weight increase in rats with abdominal aortic banding. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2002;39:866–74. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200206000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browe DM, Baumgarten CM. Angiotensin II (AT1) receptors and NADPH oxidase regulate Cl− current elicited by {beta}1 integrin stretch in rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2004;124:273–87. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200409040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GL, Wang XR, Lin MJ, He H, Lan XJ, Guan YY. Deficiency in ClC-3 chloride channels prevents rat aortic smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ Res. 2002;91:E28–E32. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000042062.69653.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P, Liu J, Di A, Robinson NC, Musch MW, Kaetzel MA, et al. Regulation of human CLC-3 channels by multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20093–100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browe DM, Baumgarten CM. EGFR kinase regulates volume-sensitive chloride current elicited by integrin stretch via PI-3K and NADPH oxidase in ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:237–51. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda JJ, Filali MS, Moreland JG, Miller FJ, Lamb FS. Activation of swelling-activated chloride current by tumor necrosis factor-alpha requires ClC-3-dependent endosomal reactive oxygen production. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22864–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.099838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D. Phenomics of cardiac chloride channels: the systematic study of chloride channel function in the heart. J Physiol (Lond) 2009;587:2163–77. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.165860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan DY, Liu LL, Bozeat N, Huang ZM, Xiang SY, Wang GL, et al. Functional role of anion channels in cardiac diseases. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:265–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume JR, Duan D, Collier ML, Yamazaki J, Horowitz B. Anion transport in heart. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:31–81. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume JR, Wang GX, Yamazaki J, Ng LC, Duan D. CLC-3 chloride channels in the pulmonary vasculature. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;661:237–47. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-500-2_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann EK, Lambert IH, Pedersen SF. Physiology of cell volume regulation in vertebrates. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:193–277. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang F. Mechanisms and significance of cell volume regulation. J Am Coll Nutr. 2007;26:613S–623S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2007.10719667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange K. Cellular volume homeostasis. Adv Physiol Educ. 2004;28:155–9. doi: 10.1152/advan.00034.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cala PM, Maldonado H, Anderson SE. Cell volume and pH regulation by the Amphiuma red blood cell: a model for hypoxia-induced cell injury. Comp Biochem Physiol Comp Physiol. 1992;102:603–8. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(92)90711-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong D, Wang GX, Burkin DJ, Yamboliev IA, Singer CA, Rawat S, et al. Cardiac-specific overexpression of the human short CLC-3 chloride channel isoform in mice. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2009;36:386–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.05069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Lieberman M. Chloride conductance is activated by membrane distention of cultured chick heart cells. Cardiovasc Res. 1996;32:168–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Shimada K, Showalter LA, Weinman SA. Biophysical properties of ClC-3 differentiate it from swelling-activated chloride channels in Chinese hamster ovary-K1 cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:35994–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002712200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stobrawa SM, Breiderhoff T, Takamori S, Engel D, Schweizer M, Zdebik AA, et al. Disruption of ClC-3, a chloride channel expressed on synaptic vesicles, leads to a loss of the hippocampus. Neuron. 2001;29:185–96. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weylandt KH, Valverde MA, Nobles M, Raguz S, Amey JS, Diaz M, et al. Human ClC-3 is not the swelling-activated chloride channel involved in cell volume regulation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17461–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011667200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto-Mizuma S, Wang GX, Liu LL, Schegg K, Hatton WJ, Duan D, et al. Altered properties of volume-sensitive osmolyte and anion channels (VSOACs) and membrane protein expression in cardiac and smooth muscle myocytes from Clcn3−/− mice. J Physiol (Lond) 2004;557:439–56. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.059261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Zhong J, Hermoso M, Satterwhite CM, Rossow CF, Hatton WJ, et al. Functional inhibition of native volume-sensitive outwardly rectifying anion channels in muscle cells and Xenopus oocytes by anti-ClC-3 antibody. J Physiol (Lond) 2001;531:437–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0437i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vessey JP, Shi C, Jollimore CA, Stevens KT, Coca-Prados M, Barnes S, et al. Hyposmotic activation of ICl,swell in rabbit nonpigmented ciliary epithelial cells involves increased ClC-3 trafficking to the plasma membrane. Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;82:708–18. doi: 10.1139/o04-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YB, Zhou JG, Guan YY. Volume-regulated chloride channels and cerebral vascular remodelling. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2010;37:238–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.05137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YB, Liu YJ, Zhou JG, Wang GL, Qiu QY, Guan YY. Silence of ClC-3 chloride channel inhibits cell proliferation and the cell cycle via G/S phase arrest in rat basilar arterial smooth muscle cells. Cell Prolif. 2008;41:775–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R, Lau CP, Tse HF, Li GR. Regulation of cell proliferation by intermediate-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium and volume-sensitive chloride channels in mouse mesenchymal stem cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1409–16. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00268.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Chen L, Xu B, Wang L, Li H, Guo J, et al. Suppression of ClC-3 channel expression reduces migration of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:1706–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do CW, Lu W, Mitchell CH, Civan MM. Inhibition of swelling-activated Cl− currents by functional anti-ClC-3 antibody in native bovine non-pigmented ciliary epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:948–55. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou JG, Ren JL, Qiu QY, He H, Guan YY. Regulation of intracellular Cl− concentration through volume-regulated ClC-3 chloride channels in A10 vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7301–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin NG, Kim JK, Yang DK, Cho SJ, Kim JM, Koh EJ, et al. Fundamental role of ClC-3 in volume-sensitive Cl− channel function and cell volume regulation in AGS cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G938–48. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00470.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R, Lau CP, Tse HF, Li GR. Functional ion channels in mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1561–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00240.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddapah VA, Sontheimer H. Molecular interaction and functional regulation of ClC-3 by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) in human malignant glioma. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11188–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.097675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Z, Tong Y, Zhu H, Watsky MA. ClC-3 is required for LPA-activated Cl− current activity and fibroblast-to-myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C535–42. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00291.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong D, Heyman NS, Airey J, Zhang M, Singer CA, Rawat S, et al. Cardiac-specific, inducible ClC-3 gene deletion eliminates native volume-sensitive chloride channels and produces myocardial hypertrophy in adult mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:211–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–36. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Wu WJ, Qiu Y, Tang XL, Yang Z, Bolli R. Demonstration of an early and a late phase of ischemic preconditioning in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:H1375–87. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.4.H1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RJ, Losito VA, Mao GD, Ford MK, Backx PH, Wilson GJ. Chloride channel inhibition blocks the protection of ischemic preconditioning and hypo-osmotic stress in rabbit ventricular myocardium. Circ Res. 1999;84:763–75. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.7.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RJ, Batthish M, Backx PH, Wilson GJ. Chloride channel inhibition does block the protection of ischemic preconditioning in myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1887–9. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batthish M, Diaz RJ, Zeng HP, Backx PH, Wilson GJ. Pharmacological preconditioning in rabbit myocardium is blocked by chloride channel inhibition. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;55:660–71. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00454-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heusch G, Liu GS, Rose J, Cohen MV, Downey JM. No confirmation for a causal role of volume-regulated chloride channels in ischemic preconditioning in rabbits. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:2279–85. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorota S. Pharmacologic properties of the swelling-induced chloride current of dog atrial myocytes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1994;5:1006–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1994.tb01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heusch G, Cohen MV, Downey JM. Ischemic preconditioning through opening of swelling-activated chloride channels. Circ Res. 2001;89:E48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozeat N, Dwyer L, Ye L, Yao T, Duan D. The role of ClC-3 chloride channels in early and late ischemic preconditioning in mouse heart. FASEB J. 2005;19:A694–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bozeat N, Dwyer L, Ye L, Yao TY, Hatton WJ, Duan D. VSOACs play an important cardioprotective role in late ischemic preconditioning in mouse heart. Circulation. 2006;114:272–3. [Google Scholar]

- Guan YY, Wang GL, Zhou JG. The ClC-3 Cl− channel in cell volume regulation, proliferation and apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:290–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk AP, Heise CK, Hougen JL, Artman CM, Volk KA, Wessels D, et al. ClC-3 and ICl-swell are required for normal neutrophil chemotaxis and shape change. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:34315–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803141200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi K, Maeta H, Yamamoto A, Oe M, Kosaka H. Amelioration of myocardial global ischemia/reperfusion injury with volume-regulatory chloride channel inhibitors in vivo. Transplantation. 2002;73:1185–93. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200204270-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Chua CC, Ho YS, Hamdy RC, Chua BH. Overexpression of Bcl-2 attenuates apoptosis and protects against myocardial I/R injury in transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H2313–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier L, Shuba Y, Crepin A, Roudbaraki M, Slomianny C, Mauroy B, et al. Bcl-2-dependent modulation of swelling-activated Cl− current and ClC-3 expression in human prostate cancer epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4841–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L, Xiao AY, Jin C, Yang A, Lu ZY, Yu SP. Effects of chloride and potassium channel blockers on apoptotic cell shrinkage and apoptosis in cortical neurons. Pflugers Arch. 2004;448:325–34. doi: 10.1007/s00424-004-1277-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel DG, Higgins RS, Baumgarten CM. Swelling-activated Cl current, ICl, swell, is chronically activated in diseased human atrial myocytes. Biophys J. 2003;84:233a. [Google Scholar]

- Clemo HF, Baumgarten CM. Protein kinase C activation blocks ICl (swell) and causes myocyte swelling in a rabbit congestive heart failure model. Circulation. 1998;98:I-695. [Google Scholar]

- Clemo HF, Stambler BS, Baumgarten CM. Swelling-activated chloride current is persistently activated in ventricular myocytes from dogs with tachycardia-induced congestive heart failure. Circ Res. 1999;84:157–65. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Liu L, Wang GL, Ye L, Tian H, Yao Y, et al. Cell volume-regulated ion channels and ionic remodeling in hypertrophied mouse heart. J Cardiac Failure. 2004;10:S72. [Google Scholar]

- van Borren MM, Verkerk AO, Vanharanta SK, Baartscheer A, Coronel R, Ravesloot JH. Reduced swelling-activated Cl− current densities in hypertrophied ventricular myocytes of rabbits with heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;53:869–78. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00507-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong D, Ye L, Neveux I, Burkin DJ, Scowen P, Evans R, et al. Cardiac specific inactivation of ClC-3 gene reveals cardiac hypertrophy and compromised heart function. FASEB J. 2008;22:970.25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu LH, Ye L, McGuckin C, Hatton WJ, Duan D.Disruption of Clcn3 gene in mice facilitates heart failure during pressure overload J Gen Physiol 200312233A12810852 [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka M, Kawano S, Hirano Y, Furukawa T. Role of cardiac chloride currents in changes in action potential characteristics and arrhythmias. Cardiovas Res. 1998;40:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg JI, Bett GC, Powell T. Contribution of a swelling-activated chloride current to changes in the cardiac action potential. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C541–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.2.C541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan D, Fermini B, Nattel S. Sustained outward current observed after Ito1 inactivation in rabbit atrial myocytes is a novel Cl− current. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H1967–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.6.H1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du XY, Sorota S. Modulation of dog atrial swelling-induced chloride current by cAMP: protein kinase A-dependent and -independent pathways. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;500:111–22. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp022003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browe DM, Baumgarten CM. Stretch of beta 1 integrin activates an outwardly rectifying chloride current via FAK and Src in rabbit ventricular myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:689–702. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten CM, Clemo HF. Swelling-activated chloride channels in cardiac physiology and pathophysiology. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;82:25–42. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(03)00003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli GF, Marban E. Electrophysiological remodeling in hypertrophy and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:270–83. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara N, Masuda H, Shoda M, Irisawa H. Stretch-activated anion currents of rabbit cardiac myocytes. J Physiol (Lond) 1992;456:285–302. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb FS, Clayton GH, Liu BX, Smith RL, Barna TJ, Schutte BC. Expression of CLCN voltage-gated chloride channel genes in human blood vessels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:657–66. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian JS, Pang RP, Zhu KS, Liu DY, Li ZR, Deng CY, et al. Static pressure promotes rat aortic smooth muscle cell proliferation via upregulation of volume-regulated chloride channel. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2009;24:461–70. doi: 10.1159/000257485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT. Bayliss, myogenic tone and volume-regulated chloride channels in arterial smooth muscle. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;507:629. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.629bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meininger GA, Davis MJ. Cellular mechanisms involved in the vascular myogenic response. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1992;263:H647–H659. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.3.H647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson WF. Ion channels and vascular tone. Hypertension. 2000;35:173–8. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Conway MA, Knot HJ, Brayden JE. Chloride channel blockers inhibit myogenic tone in rat cerebral arteries. J Physiol (Lond) 1997;502:259–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.259bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty JM, Langton PD. Measurement of chloride flux associated with the myogenic response in rat cerebral arteries. J Physiol (Lond) 2001;534:753–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remillard CV, Lupien MA, Crepeau V, Leblanc N. Role of Ca2+- and swelling-activated Cl− channels in alpha1-adrenoceptor-mediated tone in pressurized rabbit mesenteric arterioles. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;46:557–68. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doughty JM, Miller AL, Langton PD. Non-specificity of chloride channel blockers in rat cerebral arteries: block of the L-type calcium channel. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;507:433–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.433bt.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T, Wei L, De SP, Van DW, Eggermont J, Droogmans G, et al. Downregulation of volume-activated Cl− currents during muscle differentiation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1997;272:C667–74. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.2.C667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Wang XG, Tang YB, Chen JH, Lv XF, Zhou JG, et al. Simvastatin ameliorates rat cerebrovascular remodeling during hypertension via inhibition of volume-regulated chloride channel. Hypertension. 2010;56:445–52. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniyama Y, Griendling KK. Reactive oxygen species in the vasculature: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Hypertension. 2003;42:1075–81. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000100443.09293.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe S, Wang X, Takahashi N, Uramoto H, Okada Y. HCO3(−)-independent rescue from apoptosis by stilbene derivatives in rat cardiomyocytes. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:517–22. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T. Oxidant signals and oxidative stress. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:247–54. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T, Deng CX, Mostoslavsky R. Recent progress in the biology and physiology of sirtuins. Nature. 2009;460:587–91. doi: 10.1038/nature08197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devadas S, Zaritskaya L, Rhee SG, Oberley L, Williams MS. Discrete generation of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide by T cell receptor stimulation: selective regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and fas ligand expression. J Exp Med. 2002;195:59–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai YP, Bongalon S, Hatton WJ, Hume JR, Yamboliev IA. ClC-3 chloride channel is upregulated by hypertrophy and inflammation in rat and canine pulmonary artery. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;145:5–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madesh M, Hawkins BJ, Milovanova T, Bhanumathy CD, Joseph SK, Ramachandrarao SP, et al. Selective role for superoxide in InsP3 receptor-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and endothelial apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:1079–90. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutzler R, Campbell EB, Cadene M, Chait BT, MacKinnon R. X-ray structure of a ClC chloride channel at 3.0 A reveals the molecular basis of anion selectivity. Nature. 2002;415:287–94. doi: 10.1038/415287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller FJ Jr, Filali M, Huss GJ, Stanic B, Chamseddine A, Barna TJ, et al. Cytokine activation of nuclear factor kappa B in vascular smooth muscle cells requires signaling endosomes containing Nox1 and ClC-3. Circ Res. 2007;101:663–71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.151076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]