Abstract

Objective

The nature of interpersonal relationships, whether supportive or critical, may affect the association between health status and mental health outcomes. We examined the potential moderating effects of social support, as a buffer, and family criticism, as an exacerbating factor, on the association between illness burden, functional impairment and depressive symptoms.

Methods

Our sample of 735 older adults, aged 65 and older, was recruited from internal and family medicine primary care offices. Trained interviewers administered the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Duke Social Support Inventory, and Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale. Physician-rated assessments of health, including the Karnofsky Performance Status Scale and Cumulative Illness Rating Scale were also completed.

Results

Linear multivariable hierarchical regression results indicate that social interaction was a significant buffer, weakening the association between illness burden and depressive symptoms, whereas perceived social support buffered the relationship between functional impairment and depressive symptoms. Family criticism and instrumental social support were not significant moderators.

Conclusions

Type of medical dysfunction, whether illness or impairment, may require different therapeutic and supportive approaches. Enhancement of perceived social support, for those who are impaired, and encouragement of social interactions, for those who are ill, may be important intervention targets for treatment of depressive symptoms in older adult primary care patients.

Keywords: Social Support, Family Criticism, Illness Burden, Functional Impairment, Depressive Symptoms

In the United States, approximately 13% of the adult population is diagnosed with major depressive disorder in their lifetime (Hasin et al. 2005). Of particular concern, older adults may be at greater risk for depression than other age groups due to developmental, role expectation, and health-related changes (Teachman 2006). Declining physical health is often a primary trigger for depression (Yang 2006), and epidemiological data suggests that 75% of adults 65 and older have at least one, and almost 50% have two or more, chronic illnesses (National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion 2000).

The association between chronic medical conditions and depressive symptoms may be tempered, or exacerbated, by the degree and quality of an individual’s interpersonal relationships. The Interpersonal Theory of Depression proposes that difficulties in interpersonal relationships, perhaps due to recent changes in a major interpersonal role resulting from illness, are a robust contributing factor to the onset and maintenance of depressive symptoms (Davidson et al. 2004;Weissman 2010). Having a large, active social network and the receipt of emotional support may provide a buffer against health-related stressors (Penninx et al. 1998;Yang 2006), whereas loneliness, isolation, or negative social exchanges may exacerbate the effect of poor health on emotional functioning (Cacioppo et al. 2006).

In the current study, we investigated the role of three types of social support as potential buffers of the association between illness, impairment and depressive symptoms, including: instrumental support (i.e., assistance with tasks of daily living); perceived support (i.e., subjective quality of and satisfaction with one’s social network); and, social interaction (i.e., the actual extent and availability of one’s social network) (George et al. 1989;Landerman et al. 1989). Of these, perceived social support is often more predictive of depressive symptoms than the objective forms of support (Antonucci et al. 1997).

Not all interpersonal relationships are positive or helpful in nature. Concerns over close relationships, and negative social exchanges, are associated with elevated depressive symptoms (Krause et al. 1989). Importantly, dysfunctional familial relationships may impact well-being more than conflicts in peripheral relationships (Abbey et al. 1985), as they threaten enduring commitments. In the context of health dysfunction, family members may become critical, disapproving or rejecting of the health behaviors and decisions of an older adult (Seaburn et al. 2005), which may result in further functional decline, maladaptive health behaviors, increased negative affect, and depression (Bressi et al. 2007;Shields et al. 1992). As such, in the current study, we examined the role of family criticism, or the extent to which an individual perceives the receipt of critical comments from family members (Shields et al. 1994), as a potential exacerbating factor that might strengthen the association between illness or impairment and depressive symptoms.

It is not clear from previous research, however, what type of social support, or negative social interaction, is most salient for illness versus impairment, if any differences exist. We hypothesized that both illness burden and functional impairment would be independently associated with greater levels of depressive symptoms. Further, we examined the potential independent and combined moderating effects of family criticism and social support, hypothesizing that family criticism would exacerbate the association between illness/impairment and depressive symptoms, whereas social support variables would buffer this relationship.

METHOD

Participants

Patients age 65 years and older were recruited from internal medicine and family medicine primary care offices in the Rochester (New York) region, as part of a ongoing, IRB-approved study of depression and medical comorbidity; written informed consent was obtained and no author conflicts of interest exist (Hirsch et al. 2007). Of eligible subjects, 735 (50.1%) completed an interview, which were conducted in their homes or at a university research office by a trained rater. Our sample ranged in age from 65 to 97 years old (mean age = 75.14, SD = 6.89), was 63.4% female (n = 466) and had an average education level of 14.03 years (SD = 2.61). Participants were predominantly Caucasian (92.1%; n = 677), and largely lived alone (34%; n=251) or with a spouse or significant other (48%; n=353). Enrolled subjects did not significantly differ from non-enrolled patients in age, gender, or the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale score. Cognitive status for this sample (mean MMSE score = 27.61, SD = 2.49) indicates largely intact cognitive functioning (See Table 1 for mean and standard deviation scores).

Pearson’s Product Moment Correlations and Point-Biserial Correlations

| Mean [SD] N [%] |

Age | Education | Cognitive Status |

Illness Burden |

Depressive Symptoms |

Social Interaction | Perceived Social Support |

Instrumental Social Support |

Family Criticism | Functional Impairment |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender [Female] | 466 [63.4%] | −.08* | .18** | −.07 | −.01 | −.21** | −.04 | .02 | .06 | .09 | − 14** |

| Age | 75.14 [6.89] | − | − 11** | −.26** | .25** | .06 | −.10** | −.04 | .04 | −.10** | .28** |

| Education | 14.03 [2.61] | − | − | .41** | −.13** | −.16** | .25** | .18** | .05 | −.09* | −.24** |

| Cognitive Status | 27.61 [2.49] | − | − | − | −.16** | −.09* | 23** | .18** | .04 | −.06 | −.26** |

| Illness Burden | 7.55 [3.00] | - | - | - | - | .33** | - 17** | - 17** | -.07 | .05 | .59** |

| Depressive Symptoms | 8.73 [6.05] | - | - | - | - | - | -.20** | -.36** | .01 | .20** | .39** |

| Social Interaction | 8.96 [1.58] | - | - | - | - | - | - | .31** | -.18** | -.12** | -.21** |

| Perceived Social Support | 19.51 [2.19] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -.31** | -.42** | -.28** |

| Instrumental Social Support | 14.81 [2.38] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .04 | -.04 |

| Family Criticism | 1.99 [2.95] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | .07 |

| Functional Impairment | 21.79 [13.20] | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Note: Cognitive status = MMSE score; Functional Impairment = Karnofsky Performance Scale; Illness Burden= Cumulative Illness Rating Scale score; Depressive Symptoms= Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score; Social Interaction, Perceived Social Support, and Instrumental Support = Duke Social Support Index subscale scores; Family Criticism = Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale;

p<.05;

p<.01

Measures

Demographic characteristics, including age, sex, education level, ethnicity, living arrangements and cognitive status, were assessed. Because of the common comorbidity between cognitive status and depressive symptoms in older adults (Potter and Steffens 2007), we covaried functioning and impairment (Tombaugh and McIntyre 1992). The MMSE exhibits adequate reliability and validity in use with older adults (Douglas et al. 2008). Mean score for the current sample was 27.61 (SD=2.49).

We assessed depressive symptoms utilizing the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), a 24-item structured clinical interview measuring symptom frequency and severity (Hamilton 1960). The HDRS uses a five-point scale (0=absence of a symptom, 4= endorsement of a severe level of a symptom); higher scores indicate more severe symptoms. The HDRS exhibits adequate psychometric properties, including in use with primary care patients (Iannuzzo et al. 2006); in the current study, Cronbach’s α = .80.

The Duke Social Support Index (DSSI) (Landerman, George, Campbell, & Blazer 1989), a 23-item measure employing Likert scales and yes/no answers, was used to assess three components of social support: instrumental support (12 items) (e.g., do friends or family help you out when you are sick?), perceived support (7 items) (e.g., when you are talking to your family and friends do you feel you are being listened to?), and social interaction (4 items) (e.g., other than members of your family, how many persons in this area, within one hour of travel can you depend on or feel close to?). In previous research with older adults, the DSSI exhibited adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .77) (Powers et al. 2004). In the current study, subscale Cronbach’s α = .81 for social interaction, .91 for perceived support, and .96 for instrumental support.

The Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale (FEICS) (Shields, Franks, Harp, McDaniel, & Campbell 1992) was used to assess critical comments from family members. Participants responded to the 7-item perceived criticism subscale (e.g., My family approves of most everything I do; My family complains about what I do for fun); anchor ratings range from 0 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). The FEICS exhibits sufficient construct and criterion validity, and adequate internal consistency (α=.82) in use with older adult and primary care patients (Shields, Franks, Harp, & Campbell 1994). In the current study, Cronbach’s α = .72.

Chronic medical problems were objectively assessed using the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) (Linn et al. 1968), completed by each patients’ primary physician, who assessed degree of pathology and impairment present in major organ groups. Physicians used a 5-point scale (0=none, 4=extremely severe) to assess illness burden in each of 6 categories: cardiovascular/respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, musculoskeletal or integument, neuropsychiatric, and general (endocrine metabolic). CIRS scores were derived from laboratory evaluations, physical examinations, and medical history collected from interviews and health records (Hirsch, Duberstein, Chapman, & Lyness 2007).

Finally, medically induced disability was assessed using the Karnofsky Performance Status Scale (KPSS) (Karnofsky and Barchenal 1949), a physician-rated scale, which is scored from 0-100 (0=dead, 100=no evidence of disease). In our analyses, the KPSS is reverse-scored for interpretability; higher scores represent greater impairment. The KPSS exhibits adequate validity in use with geriatric patients and is associated with greater depressive symptoms and suicide risk (Conwell et al. 2000;Crooks et al. 1991).

Statistical Analyses

To assess bivariate associations, Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficients were calculated; no variables met criteria for multicollinearity (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001). Multivariate, hierarchical linear regressions were used to conduct moderation analyses (Baron and Kenny 1986), and predictor and moderator variables were centered prior to analyses (Aiken and West 1991). We covaried age, education, ethnicity, sex, cognitive status, and living arrangements which, along with predictors, were entered on the first step of regression models; interaction terms were entered on the second step. In analyses examining functional impairment, illness burden was statistically controlled and, likewise, functional impairment was controlled in analyses examining illness burden. To assess the individual effects of each potential moderator, we tested independent analytic models but also constructed a combined analytic model to ascertain interaction effects within the context of other potential moderators. To create graphic displays of interactions, grouping variables were split one standard deviation above and below the mean, except for perceived social support and family criticism, which were split at the median due to skew and kurtosis.

RESULTS

Basic associations between variables occurred in expected directions (p < .001; See Table 1). Illness burden (r = .33), functional impairment (r = .39) and family criticism (r = .20) were significantly positively associated, and social interaction (r = −.20) and perceived social support (r = −.36) were significantly negatively associated, with depressive symptoms.

The potential moderating effect of perceived social support (PSS) on the association between cumulative illness burden and depressive symptoms (standardized β = .18, p = .001), was not significant. There was a main effect for perceived social support, which was associated with fewer depressive symptoms, (t = −7.83, p < .001; standardized β = −.27; Un β = −.77 [SE=.10]).

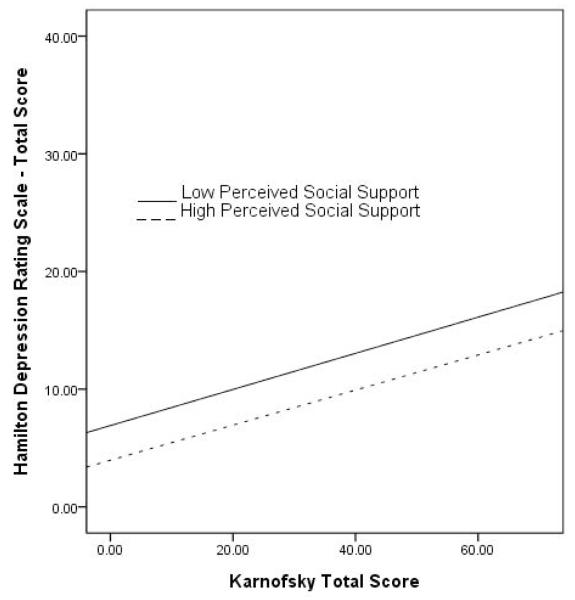

Higher functional impairment scores were associated with greater levels of depressive symptoms (t = 5.30, p < .001; standardized β = .21), and perceived social support significantly moderated this relationship, (F(1, 679) = 7.71; t = 2.78, p = .006). Those with greater perceived support have lower levels of depressive symptoms related to functional impairment (See Table 2; Figure 1). There were also main effects for perceived support, which was associated with fewer depressive symptoms (t = −8.32, p < .001), and for illness burden, (t = 4.40, p < .001), which was associated with greater depressive symptoms. While our results indicate the presence of an interaction, a graphical review suggests it is negligible; a main effect seems more predominant, such that although individuals with greater perceived support have less depressive symptoms across levels of functional impairment than those with less perceived support, they remain at increasing risk for depressive symptoms as impairment increases.

Table 2.

Multivariate hierarchical linear regressions of social relationship variables as moderators of association between functional impairment and depressive symptoms

| Perceived Social Support | All Social Support Subscales | All Social Support and Family Criticism Subscales |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 R2 | R2=.283 | R2=.282 | R2=.294 | ||||||

| Step 2 ΔR2 | ΔR2=.008** | ΔR2=.012* | ΔR2=.009 | ||||||

| Step 1 | T-value | Unβ[SE] | T-value | Unβ[SE] | T-value | Unβ[SE] | |||

| Gender | −5.03*** | −2.15 | [.43] | −4 95*** | −2.17 | [.44] | −5 24*** | −2.31 | [.44] |

| Age | −1.68 | −.05 | [.03] | −1.51 | −.05 | [.03] | −1.092 | −.035 | [.032] |

| Race | −1.61 | −.43 | [.27] | −1.54 | −.47 | [.30] | −1.56 | −.46 | [.30] |

| Residence | .12 | .02 | [.13] | .11 | .02 | [.13] | .56 | .08 | [.14] |

| Education | −1.37 | −.12 | [.09] | −1.00 | −.09 | [.09] | −.15 | −.01 | [.09] |

| Cognitive Status | .60 | .06 | [.09] | .98 | .09 | [.10] | 1.43 | .14 | [.10] |

| CIRS | 4 45*** | .36 | [.08] | 4.20*** | .35 | [.08] | 4 10*** | .35 | [.08] |

| FEICS | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.42* | .18 | [.08] |

| Social Interaction | - | - | - | −2.07* | −.29 | [.14] | −1.95* | −.28 | [.14] |

| Perceived Social Support | −7 81*** | −.75 | [.10] | −6.73*** | −.71 | [.11] | −5.66*** | −.71 | [.13] |

| Instrumental Support | - | - | - | −1.00 | −.09 | [.09] | −.78 | −.07 | [.09] |

| Karnofsky | 4 93*** | .10 | [.02] | 4 56*** | .10 | [.02] | 4 88*** | .10 | [.02] |

| Step 2 | T-value | Unβ[SE] | T-value | Unβ[SE] | T-value | Unβ[SE] | |||

| Gender | −5 15*** | −2.19 | [.43] | −5.06*** | −2.21 | [.44] | −5 31*** | −2.34 | [.44] |

| Age | −1.96 | −.06 | [.03] | −1.78 | −.06 | [.03] | −1.28 | −.04 | [.03] |

| Race | −1.51 | −.40 | [.26] | −1.35 | −.41 | [.30] | −1.28 | −.38 | [.30] |

| Residence | .42 | .06 | [.13] | .35 | .05 | [.13] | .64 | .09 | [.14] |

| Education | −1.44 | −.13 | [.09] | −.99 | −.09 | [.09] | −.07 | −.01 | [.09] |

| Cognitive Status | .56 | .05 | [.09] | 1.05 | .10 | [.10] | 1.25 | .12 | [.10] |

| CIRS | 4 40*** | .36 | [.08] | 4 18*** | .35 | [.08] | 4 11*** | .35 | [.08] |

| FEICS | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.12* | .16 | [.08] |

| Social Interaction | - | - | - | −2.01* | −.28 | [.14] | −1.80 | −.25 | [.14] |

| Perceived Social Support | −8 32*** | −.85 | [.10] | −7 48*** | −.83 | [.11] | −6.18*** | −.80 | [.13] |

| Instrumental Support | - | - | −.89 | −.08 | [.09] | −.99 | −.10 | [.10] | |

| Karnofsky | 5.30*** | .11 | [.02] | 4 61*** | .10 | [.02] | 4.77 | .12 | [.02] |

| Karnofsky * FEICS | - | - | - | - | 1.92 | .01 | [.01] | ||

| Karnofsky * Social Interaction | - | - | - | −.08 | .00 | [.01] | −.02 | .00 | [.01] |

| Karnofsky * Perceived Social Support | 2.78** | .02 | [.01] | 2.25* | .02 | [.01] | 2.36* | .02 | [.01] |

| Karnofsky * Instrumental Support | - | - | - | −1.12 | −.01 | [.01] | −.42 | −.00 | [.01] |

Note: Cognitive status = MMSE; Functional Impairment = Karnofsky; Illness Burden = CIRS; Depressive Symptoms = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; Social Interaction, Perceived Social Support, and Instrumental support = Subscales of the Duke Social Support Index; Family Criticism = subscale of Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale;

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Figure 1. Moderating Effect of Perceived Social Support on Association between Functional Impairment and Depressive Symptoms.

Note: Depressive symptoms = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression total score; Functional impairment = Karnofsky Performance Scale total score.

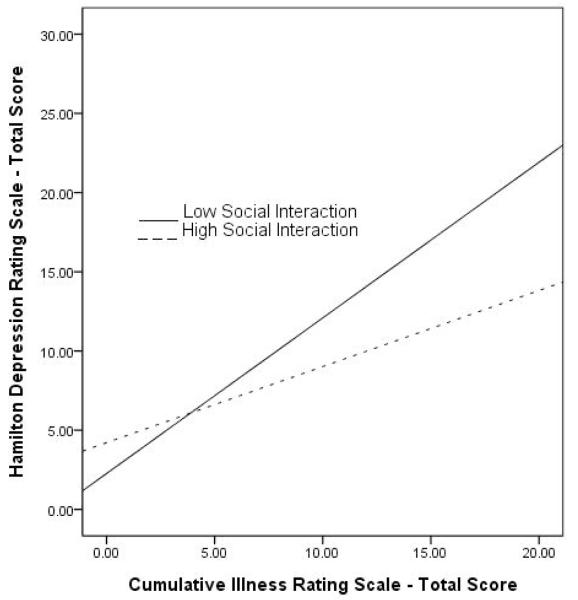

Greater illness burden was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms (t = 4.38, p < .001; standardized β = .18; Un β = .37 [SE=.09]), and social interaction was a significant moderator, (F(1, 674) = 6.24, t = −2.50, p < .05, Un β = −.11 [SE=.04]; R2=.236, ΔR2=.007, p < .05). Those with more social interaction have lower levels of depressive symptoms associated with illness burden (See Table 3; Figure 2). Main effects existed for functional impairment, (t = 5.55, p < .001; Un β = .12 [SE=.02]), which was associated with greater depressive symptoms, and for social interaction, (t = −3.42, p < .01; standardized β = −.13; Un β = −.47 [SE=.14]), which was associated with fewer depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Multivariable hierarchical linear regressions of social relationship variables as moderators of association between illness burden and depressive symptoms

| Perceived Social Support | All Social Support Subscales | All Social Support and Family Criticism Subscales |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 R2 | R2=.283 | R2=.282 | R2=.294 | ||||||

| Step 2 ΔR2 | ΔR2=.001 | ΔR2=.007 | ΔR2=.009 | ||||||

| Step 1 | T-value | Unβ[SE] | T-value | Unβ[SE] | T-value | Unβ[SE] | |||

| Gender | −4.96*** | −2.20 | [.44] | −4 95*** | −2.17 | [.44] | −5 24*** | −2.31 | [.44] |

| Age | −2.04* | −.07 | [.03] | −1.51 | −.05 | [.03] | −1.09 | −.04 | [.03] |

| Race | −2.03* | −.57 | [.28] | −1.54 | −.47 | [.30] | −1.56 | −.46 | [.30] |

| Residence | .69 | .09 | [.14] | .11 | .02 | [.13] | .56 | .08 | [.14] |

| Education | −1.54 | −.14 | [.09] | −1.00 | −.09 | [.09] | −.15 | −.01 | [.09] |

| Cognitive Status | .69 | .07 | [.10] | .98 | .09 | [.10] | 1.43 | .14 | [.10] |

| Karnofsky | 5 85*** | .12 | [.02] | 4 56*** | .10 | [.02] | 4 88*** | .10 | [.02] |

| CIRS | 4.33*** | .37 | [.09] | 4.20*** | .35 | [.08] | 4 10*** | .35 | [.08] |

| FEICS | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.42* | .18 | [.08] |

| Social Interaction | −3 59*** | −.49 | [.14] | −2.07* | −.29 | [.14] | −1.95 | −.28 | [.14] |

| Perceived Social Support | - | - | - | −6.73*** | −.71 | [.11] | −5.66*** | −.71 | [.13] |

| Instrumental Support | - | - | - | −1.00 | −.09 | [.09] | −.78 | −.07 | [.09] |

| Step 2 | T-value | Unβ[SE] | T-value | Unβ[SE] | T-value | Unβ[SE] | |||

| Gender | −4 95*** | −2.19 | [.44] | −4 94*** | −2.16 | [.44] | −5.20*** | −2.28 | [.44] |

| Age | −1.81 | −.06 | [.03] | −1.35 | −.04 | [.03] | −.86 | −.03 | [.03] |

| Race | −2.12* | −.60 | [.28] | −1.59 | −.48 | [.30] | −1.58 | −.47 | [.30] |

| Residence | .70 | .10 | [.14] | .08 | .01 | [.13] | .56 | .08 | [.14] |

| Education | −1.68 | −.16 | [.09] | −1.10 | −.10 | [.09] | −.33 | −.03 | [.09] |

| Cognitive Status | .71 | .07 | [.10] | 1.01 | .10 | [.10] | 1.53 | .15 | [.10] |

| Karnofsky | 5 55*** | .12 | [.02] | 4 39*** | .09 | [.02] | 4 69*** | .10 | [.02] |

| CIRS | 4.38*** | .37 | [.09] | 4 20*** | .35 | [.08] | 3.96*** | .34 | [.09] |

| FEICS | - | - | - | 2.33* | .18 | [.08] | |||

| Social Interaction | −3.42** | −.47 | [.14] | −1.97* | −.27 | [.14] | −1.91 | −.27 | [.14] |

| Perceived Social Support | - | - | - | −6.81*** | −.74 | [.11] | −5 78*** | −.74 | [.13] |

| Instrumental Support | - | - | - | −1.02 | −.09 | [.09] | −.95 | −.09 | [.10] |

| CIRS*FEICS | - | - | - | - | - | 1.38 | .03 | [.02] | |

| CIRS* Social Interaction | −2.50* | −.11 | [.04] | −2.25* | −.10 | [.05] | −2.43* | −.11 | [.05] |

| CIRS*Perceived Social Support | - | - | - | 1.55 | .05 | [.03] | 1.23 | .04 | [.04] |

| CIRS* Instrumental Support | - | - | - | −.48 | −.01 | [.03] | −.33 | −.01 | [.03] |

Note: Cognitive status = MMSE; Functional Impairment = Karnofsky; Illness Burden = CIRS; Depressive Symptoms = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; Social Interaction, Perceived Social Support, and Instrumental support = Subscales of the Duke Social Support Index; Family Criticism = subscale of Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale;

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Figure 2. Moderating Effect of Social Interaction on Association between Illness Burden and Depressive Symptoms.

Note: Depressive symptoms = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression total score; Illness burden = Cumulative Illness Rating Scale total score.

In an analysis of the potential moderating effect of social interaction on the association between functional impairment and depressive symptoms, (t = 5.71, p < .001; standardized β = .26; Un β = .12 [SE=.02]), social interaction was not a significant moderator. However, there was a significant main effect for social interaction, which was associated with fewer depressive symptoms, (t = −3.60, p < .001; standardized β = −.13; Un β = −.49 [SE=.14]).

Although there were main effects for the associations between cumulative illness burden and depression (F(1, 672) = .00, p= .971; standardized β = .19, p = .000), and functional impairment and depression (F(1, 672)= 1.67, p = .197; standardized β = .27, p = .000), instrumental social support was not a significant moderator in either analyses. Similarly, in analyses of family criticism, higher illness burden, (F(1, 655)= .20, p = .656; standardized β = .18, p = .000), and functional impairment, (F(1, 655) = .53, p = .465; standardized β = .27, p = .000), were associated with more depressive symptoms; however, family criticism was not a significant moderator. There was a main effect for family criticism, which was related to greater depressive symptoms, (t = 5.14, p < .001; standardized β = .1; Un β = .36 [SE=.07]).

In a combined model examining illness burden and all social support subscales simultaneously, greater illness burden was significantly associated with more depressive symptoms (t = 4.20, p < .001; standardized β = .18; Un β = .35 [SE=.08]), and only social interaction was a significant moderator (F(3, 654)= 2.19, p = .088; t = −2.25, p < .05; standardized β = −.08; Un β = −.10 [SE=.05]; ΔR2 = NS). Those with higher levels of social interaction reported fewer depressive symptoms related to illness burden (See Table 3). Main effects existed for social interaction, (t = −1.97, p < .05; standardized β = −.08; Un β = −.27 [SE=.14]), and perceived support, (t = −6.81, p < .001; standardized β = −.26; Un β = −.74 [SE=.11]), which were associated with less depressive symptoms.

Similarly, in a combined model examining functional impairment and all social support subscales (See Table 2), higher functional impairment was significantly associated with more depressive symptoms, (t = 4.61, p < .001; standardized β = .20), and perceived support was a significant moderator, (F(3, 654)= 3.70, p = .012; t = 2.25, p < .05; standardized β = .10). Those with greater perceived support reported fewer depressive symptoms associated with functional impairment. Main effects were found for social interaction, (t = −2.01, p < .05; standardized β = −.08), and perceived support, (t = −7.48, p < .001; standardized β = −.26), which were related to less depressive symptoms.

Finally, in a combined model examining illness burden, all social support subscales, and the family criticism scale, illness burden was significantly positively associated with depressive symptoms, (t = 3.96, p < .001; Un β = .34 [SE=.09]), yet, only social interaction moderated this relationship, (t = −2.43, p < .05; standardized β = −.09; Un β = −.11 [SE=.05]) (See Table 3). Similarly, in a combined model examining functional impairment and all potential social support and family criticism moderators, only perceived support significantly moderated this relationship, (t = 2.36, p < .05; standardized β = .10), although there was a trend toward significance for the interaction with family criticism, (t = 1.92, p = .056; standardized β = .07). Individuals with greater perceived support, and less perceived family criticism report less depressive symptoms related to functional impairment.

DISCUSSION

Supporting our hypotheses, we found a significant, positive association between illness burden, functional impairment, family criticism, and a significant negative relationship between perceived social support and social interaction, and depressive symptoms. Social interaction significantly buffered the association between illness burden, and perceived social support significantly buffered the relationship between functional impairment, and depressive symptoms. Neither instrumental support nor family criticism reached significance as moderators. Our results suggest that there may be context-specific differences in the effects of social support; type of support may make a difference, depending on the type of stressor.

For instance, perceived social support was a significant moderator of the association between functional impairment, but not illness burden, and depressive symptoms. Perceived quality of social relations may help older adults cope with deficits in many ways, including increasing life satisfaction, meaningfulness and feelings of belongingness (Newsom and Schulz 1996;Park 2009), and bolstering coping ability (Zautra et al. 2000). When impaired, a sense of the quality and genuineness of social support may be more important for reducing depression risk than simply having many social contacts (Roberson and Lichtenberg 2003).

On the other hand, social interaction significantly moderated the association between illness burden, but not functional impairment, and depressive symptoms. As an older adult experiences more social interactions, they may feel less lonely and isolated (Street et al. 1999), and more likely to feel supported emotionally. Interactions with others may also facilitate, through encouragement or enhancement of personal control, adaptive health behaviors such as adherence to treatment regimens or engagement in lifestyle changes, which may be beneficial not only for physical but mental health (Umberson and Montez 2010).

Instrumental support was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms, nor was it a moderator, suggesting that older adults experiencing chronic illness and impairment may benefit more, psychologically, from extent and quality of social support (Wallsten et al. 1999). For ill or impaired individuals, receiving instrumental support, while perhaps undesirable, may be viewed as a necessary consequence of one’s health status and may not, therefore, contribute to depression risk. It may be that instrumental support is not as crucial for our sample of ambulatory, older adults presenting for treatment in primary care offices, who are likely not as ill or functionally impaired as those in assisted living and nursing homes (Goodwin and Smyer 1999).

Family criticism was significantly positively associated with depressive symptoms, confirming previous research (Seaburn, Lyness, Eberly, & King 2005), but did not significantly moderate the association between illness burden and depressive symptoms, and only neared significance as a buffer of functional impairment. This lack of findings may be due to the interpersonal characteristics of our sample, which reported generally high levels of perceived social support and low levels of family criticism. Further, several questions on the FEICS (e.g, my family finds fault with my friends, and my family approves of my friends) may not be suitable for older adults. It may also be the case that already-elevated levels of stress associated with health difficulties supersede distress resulting from familial verbal criticism and, thus, do not additionally compound depression risk.

Our findings may have important implications for interventions in primary care settings which, due to the negative perception of older adults regarding utilization of mental health services (Bogner et al. 2009), are an important “point of capture” (Unützer 2002). Behavioral health consultants working in primary care should attempt to enhance both the number and quality of social interactions of elderly patients (Lebowitz et al. 1997). Older adults experiencing chronic illness may benefit from experiential or meaning-based social activities, perhaps involving close family or friends (Jopp and Hertzog 2010), or participation in religious or spiritual activities (Thune-Boyle et al. 2006). Participation in psycho-educational or self-help groups (Laitinen et al. 2006), or engagement in both leisure and productive social activities, such as physical exercise or attending a senior citizens center (Herzog et al. 1998), may help ill or impaired older adults develop a sense of competency and capability which, in turn, may reduce depressive symptoms.

Older adults with functional impairment, however, may not be willing or able to engage in frequent social interactions, due to decreased mobility and embarrassment or stigma regarding their impairment (Bahm and Forchuk 2009). In this case, interventions must be focused on either enhancing quality of support, perhaps from caregivers, or assisting the patient in ascribing meaning to the care they receive. Reflective listening techniques, cognitive reframing, or narrative therapy, may help a patient to explore themes of loss and devaluation (Kropf and Tandy 1998). In general, facilitation of interpersonal functioning, or enhancement of the perceived quality of support, may be accomplished using evidence-based treatments, such as CBT, which are cost-effective and, able to be broadly disseminated (Buenaver et al. 2006).

Despite our study’s many strengths, minor limitations must be addressed. Our cross-sectional design prevents the establishment of causal relationships, and bi-directionality of associations is a possibility. Symptoms of depression likely complicate health functioning and, as well, illness and impairment may affect the receipt of social support and family criticism (Fiscella and Campbell 1999;Meeks et al. 2000); prospective research is needed. A general lack of diversity in our sample limits generalizability, and a more thorough examination of the association between socio-cultural factors and the variables in our study is needed (Musil et al. 1998). In this secondary analysis, the measure of family criticism available, the FEICS, may not be ideally suited for older adults, and our measure of social support did not include an assessment of emotional support, which is of importance to older adult well-being (Oxman et al. 1992). There may also be potentially important variables that we were unable to include in analytic models. Finally, overall, our analytic models only accounted for a small percentage of variance, suggesting that there are other variables that should be accounted for to better explain the relationships posited in our hypotheses. Future research utilizing more appropriate and comprehensive measures, and including variables such as financial strain, loneliness, isolation, helplessness, and hopelessness, is needed.

Despite these limitations, our results suggest that perceived satisfaction with social support and frequency of social interactions are important to the psychological wellbeing of older adults with chronic illness and functional impairment. Although such health difficulties may have a critical impact on quality of life via the stressful experience of loss of role status, impaired sense of well-being, and disruption of social support (Newsom & Schulz 1996), our findings suggest that it may be possible to lessen such adverse psychological consequences by increasing perceived social support and promoting social interactions.

Key Points.

Illness burden and functional impairment contribute to risk for depressive symptoms.

Social support and family criticism affect the associations between health status and depressive symptoms, but their effect may differ depending on nature of the stressor.

For illness burden, social interaction moderated, and for functional impairment, perceived social support moderated, the association with depressive symptoms.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant numbers R01 MH61429, K24 MH071509-05 to JML).

References

- Abbey A, Abramis DJ, Caplan RD. Effects of different sources of social support and social conflict on emotional well-being. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1985;6(2):111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Fuhrer R, Dartigues JF. Social relations and depressive symptomatology in a sample of community-dwelling French older adults. Psychology and Aging. 1997;12(1):189–195. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahm A, Forchuk C. Interlocking oppressions: the effect of a comorbid physical disability on perceived stigma and discrimination among mental health consumers in Canada. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2009;17(1):63–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00799.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogner HR, de Vries HF, Maulik PK, Unützer J. Mental health services use: Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area follow-up. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009;17(8) doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181aad5c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bressi C, Cornaggia CM, Beghi M, Porcellana M, Iandoli II, Invernizzi G. Epilepsy and family expressed emotion: Results of a prospective study. Seizure: The Journal of the British Epilepsy Association. 2007;16(5):417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buenaver LF, McGuire L, Haythornthwaite JA. Cognitive-behavioral self-help for chronic pain. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62(11):1389–1396. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20318. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21(1):140–151. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conwell Y, Lyness JM, Duberstein P, Cox C, Seidlitz L, DiGiorgio A, Caine ED. Completed suicide among older patients in primary care practices: A controlled study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(1):23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks V, Waller S, Smith T, Hahn TJ. The use of the Karnofsky Performance Scale in determining outcomes and risk in geriatric outpatients. Journal of Gerontology. 1991;46(4):M139–M144. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.4.m139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson KW, Rieckmann N, Lesperance F. Psychological theories of depression: Potential application for the prevention of acute coronary syndrome recurrence. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2004;66(2):165–173. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000116716.19848.65. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000116716.19848.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas A, Letts L, Liu L. Review of cognitive assessments for older adults. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 2008;26(4):13–43. doi: 10.1080/02703180801963758. [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Campbell TL. Association of perceived family criticism with health behaviors. Journal of Family Practice. 1999;48(2):128–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini mental state”. A practical method of grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Blazer DG, Hughes DC, Fowler N. Social support and the outcome of major depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;154(4):478–485. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin PE, Smyer MA. Accuracy of recognition and diagnosis of comorbid depression in the nursing home. Aging & Mental Health. 1999;3(4):340–350. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1097–1106. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog AR, Franks MM, Markus HR, Holmberg D. Activities and well-being in older age: Effects of self-concept and educational attainment. Psychology and Aging. 1998;13(2):179–185. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.13.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JK, Duberstein PR, Chapman B, Lyness JM. Positive and negative affect and suicide ideation in older adult primary care patients. Psychology & Aging. 2007;22(2):80–85. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.380. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000209219.06017.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannuzzo RW, Jaeger J, Goldberg JF, Kafantaris V, Sublette ME. Development and reliability of the HAM-D/MADRS Interview: An integrated depression symptom rating scale. Psychiatry Research. 2006;145(1):21–37. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopp DS, Hertzog C. Assessing adult leisure activities: An extension of a self-report activity questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2010;22(1):108–120. doi: 10.1037/a0017662. doi: 10.1037/a0017662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnofsky DA, Barchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: Macleod CM, editor. Evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents. Columbia University Press; New York: 1949. pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Liang J, Yatomi N. Satisfaction with social support and depressive symptoms: A panel analysis. Psychology and Aging. 1989;4(1):88–97. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.4.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropf NP, Tandy C. Narrative therapy with older clients: The use of a “meaning-making” approach. Clinical Gerontologist: The Journal of Aging and Mental Health. 1998;18(4):3–16. doi: 10.1300/J018v18n04_02. [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen I, Ettorre E, Sutton C. Empowering depressed women: Changes in individual and social feelings in guided self-help groups in Finland. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling. 2006;8(3):305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Landerman R, George LK, Campbell RT, Blazer DG. Alternative models of the stress buffering hypothesis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1989;17(5):625–642. doi: 10.1007/BF00922639. doi: 10.1007/BF00922639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebowitz BD, Pearson JL, Schneider LS, Reynolds CF, Alexopoulos GS, Bruce ML, Conwell Y, Katz IR, Meyers BS, Morrison MF, Mossey J, Niederehe G, Parmelee P. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in late life. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278(14):1186–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linn BS, Linn MW, Gurel L. Cumulative illness rating scale. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1968;16(5):622–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1968.tb02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks S, Murrell SA, Mehl RC. Longitudinal relationships between depressive symptoms and health in normal older and middle-aged adults. Psychology and Aging. 2000;15(1):100–109. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musil CM, Haug MR, Warner CD. Stress, health and depressive symptoms in older adults at three time points over 18 months. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1998;19(3):207–224. doi: 10.1080/016128498249033. doi: 10.1080/016128498249033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion . Chronic diseases and their risk factors: The nation’s leading causes of death, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Washington, D.C.: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom JT, Schulz R. Social support as a mediator in the relation between functional status and quality of life in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11(1):34–44. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.11.1.34. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.11.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxman TE, Berkman LF, Kasl S, Freeman DH, Jr., Barrett J. Social support and depressive symptoms in the elderly. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1992;135(4):356–368. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park NS. The relationship of social engagement to psychological well-being of older adults in assisted living facilities. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2009;28(4):461–481. doi: 10.1177/0733464808328606. [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BWJH, van Tilburg T, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJH, Kriegsman DMW, van Eijk JT. Effects of social support and personal coping resources on depressive symptoms: Different for various chronic diseases? Health Psychology. 1998;17(6):551–558. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.6.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter GG, Steffens DC. Contribution of depression to cognitive impairment and dementia in older adults. The Neurologist. 2007;13(3) doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000252947.15389.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers JR, Goodger B, Byles JE. Assessment of the abbreviated Duke Social Support Index in a cohort of older Australian women. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2004;23(2):71–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2004.00008.x. [Google Scholar]

- Roberson T, Lichtenberg PA. Depression, social support, and functional abilities - longitudinal findings. Clinical Gerontologist. 2003;26(3):55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Seaburn DR, Lyness JM, Eberly S, King DA. Depression, perceived family criticism, and functional status among older, primary-care patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13(9):766–772. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.9.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields CG, Franks P, Harp JJ, Campbell TL. Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale (FEICS): II. Reliability and validity studies. Families, Systems & Health. 1994;12(4):361–377. doi: 10.1037/h0089289. [Google Scholar]

- Shields CG, Franks P, Harp JJ, McDaniel SH, Campbell TL. Development of the Family Emotional Involvement and Criticism Scale (FEICS): A self-report scale to measure expressed emotion. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1992;18(4):395–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1992.tb00953.x. [Google Scholar]

- Street H, Sheeran P, Orbell S. Conceptualizing depression: An integration of 27 theories. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 1999;6(3):175–193. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0879(199907)6:3<175::AID-CPP200>3.0.CO;2-Q. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Teachman BA. Aging and negative affect: The rise and fall and rise of anxiety and depression symptoms. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21(1):201–207. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.201. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thune-Boyle IC, Stygall JA, Keshtgar MR, Newman SP. Do religious/spiritual coping strategies affect illness adjustment in patients with cancer? A systematic review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(1):151–164. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.055. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini mental state examination: A comprehensive review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992;40:922–935. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(1 suppl):S54–S66. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unützer J. Diagnosis and treatment of older adults with depression in primary care. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):285–292. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallsten SM, Tweed DL, Blazer DG, George LK. Disability and depressive symptoms in the elderly: The effects of instrumental support and its subjective appraisal. International Journal of Aging & Human Development. 1999;48(2):145–159. doi: 10.2190/E48R-W561-V7RG-LL8D. doi: 10.2190/E48R-W561-V7RG-LL8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM. Interpersonal Psychotherapy. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. How does functional disability affect depressive symptoms in late life? The role of perceived social support and psychological resources. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47(4):355–372. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Hamilton N, Yocum D. Patterns of positive social engagement among women with rheumatoid arthritis. Occupational Therapy Journal of Research. 2000;20:21–40. [Google Scholar]