Abstract

Lenalidomide is a synthetic compound derived by modifying the chemical structure of thalidomide. It belongs to the second generation of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs) and possesses pleiotropic properties. Even if lenalidomide has been shown to be active in the treatment of several hematologic malignancies, this review article is mostly focalized on its mode of action in multiple myeloma. The present paper is about the direct and indirect antitumor effects of lenalidomide on malignant plasmacells, bone marrow microenvironment, bone resorption and host's immune response. The molecular mechanisms and targets of lenalidomide remain largely unknown, but recent evidence shows cereblon (CRBN) as a possible mediator of its therapeutical effects.

1. Introduction

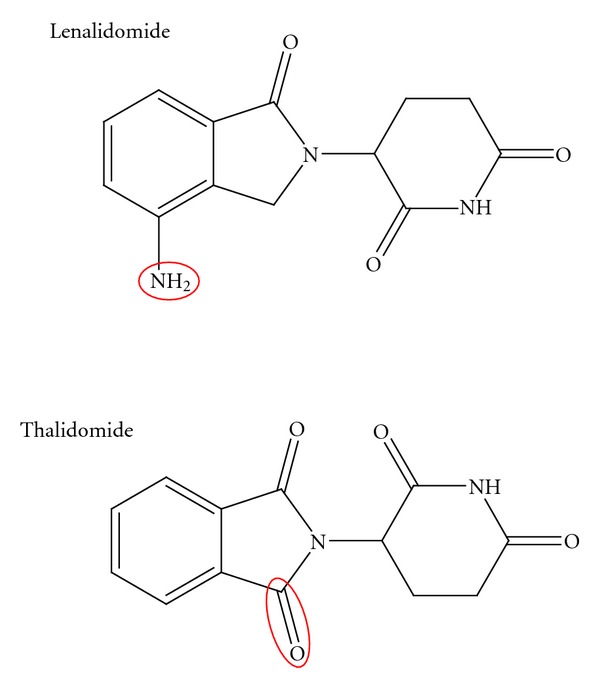

Lenalidomide and pomalidomide are synthetic compounds derived by modifying the chemical structure of thalidomide [1]. In particular, as shown in Figure 1, lenalidomide has been synthesized from the structural bone of thalidomide molecule. Lenalidomide has been developed by adding an amino group (NH2–) at 4th position of phthaloyl ring and by removing the carbonyl group (C=O) of the 4-amino-substituted phthaloyl ring. This drug is the result of the pressing need to develop molecules with enhanced immunomodulatory and antitumor activity in comparison to thalidomide. Lenalidomide, which possesses pleiotropic properties, belongs to the second generation of immunomodulatory drugs (IMiDs).

Figure 1.

Lenalidomide and thalidomide structure.

Lenalidomide and its parental molecule thalidomide have shown therapeutical activity in various malignancies [2–21].

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first approved lenalidomide for the treatment of patients suffering from 5q-myelodysplastic syndrome [22]. However, because of the proven activity of thalidomide in multiple myeloma (MM), the clinical activity of lenalidomide has been evaluated more extensively in this neoplasia [7–12], in respect to other B-cell neoplasia. The favourable toxic profile of lenalidomide and its antitumor activity emerged from phase I and phase II studies in relapsed or refractory MM patients [23–25]. These encouraging results led to the design of two large, phase III, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, registration trials (MM-009 in US and Canada and MM-010 in Europe, Australia, and Israel) in this setting of patients. In both studies, patients were randomly assigned to receive 25 mg of lenalidomide or placebo on days 1 to 21 of 28-day cycles plus dexamethasone (40 mg on days 1 to 4, 9 to 12 and 17 to 20 for the first four cycles, then only on days 1 to 4). The results of these trials have shown the superiority of lenalidomide-dexamethasone combination compared to placebo-dexamethasone in terms of time to progression (11,1–11,3 months versus 4,7 months in the lenalidomide and in the placebo group, resp., P < 0, 001), overall survival (in MM-009: 29,6 months versus 20,2 months in the lenalidomide and in the placebo group, resp., P < 0, 001, in MM-010: hazard ratio for death 0,66, P = 0, 03) and overall response rate (60,2–61% versus 19,9–24% in the lenalidomide and in the placebo group, resp., P < 0, 001). At a median followup of 48 months for surviving patients, a pooled update analysis of these studies has shown a significant benefit in overall survival (38 versus 31,6 months, P < 0, 045) for those patients initially randomized to be treated with lenalidomide-dexamethasone combination [8, 26]. It should be emphasized that the improved survival associated to lenalidomide-dexamethasone treatment was retained despite 47,6% of patients, who were initially randomized to placebo dexamethasone, received lenalidomide-based therapies after disease progression or study unblinding [27]. More recently, several studies have compared the activity of lenalidomide combined with high or reduced dose of dexamethasone in newly diagnosed MM patients [28, 29]. The results of these experiences are in favour of low dose of dexamethasone. Furthermore, clinical experience with lenalidomide indicates that early use in MM therapy is associated with a higher response rate and, possibly, prolonged survival [30]. To further improve the outcome of lenalidomide, combination regimens (BiRd, VRD, RAD, VDCR, and VRDD) [31–35] have been evaluated or are under investigation in both old and young MM patients, in transplant and non transplant settings.

MM has been chosen for this article with the purpose of showing our current knowledge on the mechanisms of antitumor activity of lenalidomide. Some of these actions are operative in other diseases too.

2. Biological Features of Multiple Myeloma

To understand the therapeutic activity of lenalidomide in MM, the knowledge of the pathophysiology of this disease and the complex crosstalk between malignant plasma cells (PCs) and their microenvironment in tumor growth and progression is relevant. In addition, the notion that survival of neoplastic cells is dependent on the escape from the host's antitumor immune response can help to explain the therapeutic role of lenalidomide.

Two major pathways are involved in the early pathogenesis of MM [36, 37]. Nearly half of these tumors are nonhyperdiploid and mostly are characterized by immunoglobulin H (IgH) translocations that involve five recurrent chromosomal loci, including 11p13, 6p21, 4p15, 16p23, and 20p11, which result in the dysregulated expression of an oncogene [36, 38]. These genetic lesions are responsible, at least in part, for anen hanced proliferative capacity of malignant PCs. In fact, the translocations lead directly (11q13 cyclin D1 and 6p21 cyclin D3) or indirectly (4p16, 16p23, 20p11 cyclin D2) to cyclin D dysregulation. In hyperdiploid tumors, cyclin D1 or less often cyclin D2 is usually dysregulated too [38]. Cyclin D, together with CDK4 and CDK6, regulates G1-S cell cycle progression by phosphorylating and inactivating retinoblastoma protein (RB). This reaction is inhibited by the CDK inhibitors p161INK4a and p181INK4c. These molecules can undergo mutations in MM and, in addition to cyclin D [39–41] dysregulation, can further facilitate the proliferation of the neoplastic clone.

Malignant PCs reside in the BM microenvironment which comprises physical and soluble factors. Physical elements of BM include extracellular matrix (ECM), glycoproteins, hemopoietic stem, progenitor, and precursor cells, as well as B, T, and NK lymphocytes, bone marrow endothelial cells, osteoclasts, and osteoblasts and bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs). Tumor cells adhere to ECM proteins and BMSCs. These interactions are responsible for tumor cell localization in the BM milieu and moreover for multiple biologically relevant sequelae [37, 42]. Adhesion molecules, including CD44, very late antigen 4 (VLA-4), very late antigen 5 (VLA-5), leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1, CD11a), neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM, CD56), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1, CD54), syndecan (CD138), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MPC-1), mediate adhesion of malignant PCs to either ECM proteins or BMSCs [37, 42] Table 1.

Table 1.

“Crosstalk” between PC and BMSC.

| Adhesion molecules |

| Very late activation antigens-4 (VLA-4) |

| Lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) |

| Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) |

| Intercellular adhesion molocule-1 (ICAM-1) |

| Syndecan-1 |

|

|

| Cytokines |

| Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) |

| Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) |

| Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) |

| Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) |

| Angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1) |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) |

| Insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) |

|

|

| Proteasi |

| Matrix metalloproteinases -2 and -9 (MMP-2 e MMP-9) |

|

|

| Chemokine |

| Macrophage inflammatory protein-1 (MIP-1) |

| Stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1) |

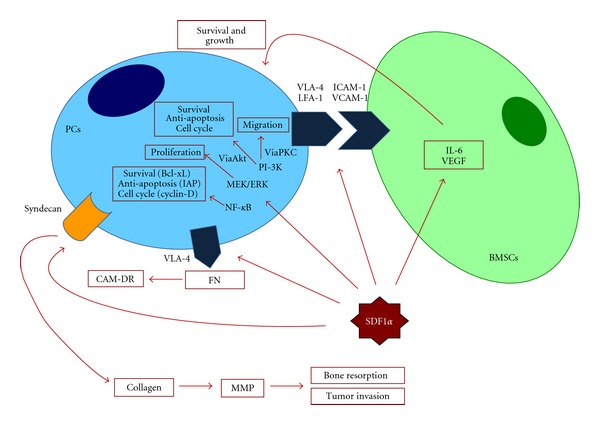

The initial homing of neoplastic cells to the BM milieu is mediated by the binding of the stromal-derived growth factor (SDF-1α), present in the BM, to its receptor CXCR4, expressed by malignant PCs. High serum concentrations of SDF-1α correlate with a more aggressive disease. This event is the consequence of the effect of this chemokine on IL-6 and VEGF production by BMSCs. These cytokines promote PC growth and survival [43]. Furthermore, SDF-1α modulates the expression of adhesion molecules on PCs (VLA4 and LFA-1) and BMSCs (VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) and favours the adherence between these cells. Syndecan and VLA-4, expressed on malignant PCs, mediate their adhesion to collagen and fibronectin, respectively [44, 45]. Finally, adhesion of malignant PCs via syndecan to collagen induces matrix metalloproteinase-1, thereby promoting bone resorption and tumor invasion, while binding via VLA-4 to fibronectin is responsible for cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR) [44, 45] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

SDF-1α actions and its functional sequelae.

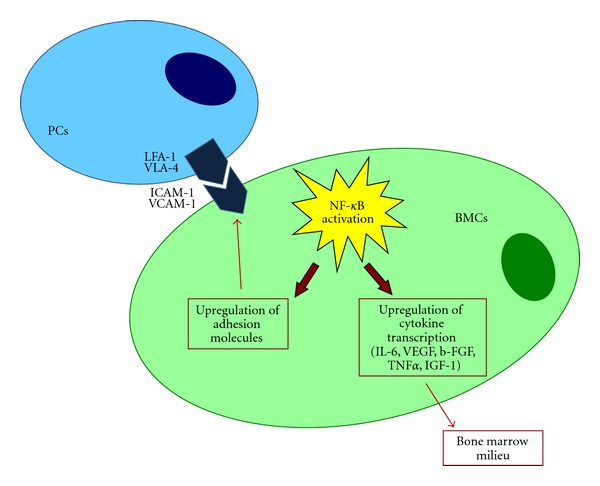

Moreover, adhesion of PCs to BMSCs triggers, in these latter cells, the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB) which results in both further upregulation of adhesion molecules, transcription and secretion of interleukine-6 (IL-6) [46] and other cytokines (vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (b-FGF), tumor necrosis factor-α [TNFα] and insulin-like growth factor-1 [IGF-1]) within the BM milieu [47, 48]. (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

NF-kB activation and its functional biological sequelae.

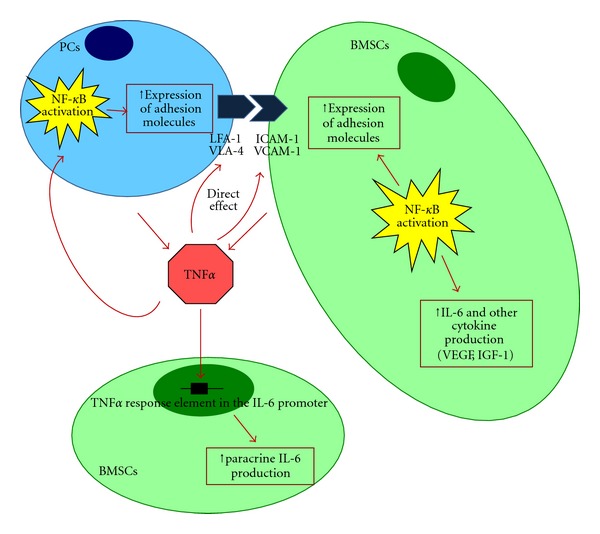

In detail, IL-6 is a critical growth factor for normal B-cell and PC development. IL-6 is primarily produced by BMSCs and by only a few malignant PCs [49]. TNFα is secreted by both malignant PCs and BMSCs. It does not induce growth and survival of the neoplastic clone directly, but it binds to a TNFα response element of the IL-6 promoter in BMSCs inducing paracrine production of IL-6 [49, 50]. Furthermore, TNFα secreted by malignant PCs activates NF-kB pathway, which results in additional upregulation of adhesion molecules (CD49d, an integrin alpha subunit and ICAM-1) on both tumor PCs and BMSCs [50]. The final effects of this loop consist in additional paracrine secretion of IL-6, as well as that of IGF-1 and VEFG by BMSCs and in induction of CAM-DR [44, 46] (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Induction of IL-6 secretion by TNFα and NF-kB activation.

Cytokine secretion in BMSCs is also upregulated by PC-derived transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and VEGF [48]. This event, in turn, induces BMSCs to produce further TNFα, VEGF and b-FGF. Overall, these events lead to the generation of a vicious circuit responsible for continuously increased cytokine production and malignant PC clone expansion.

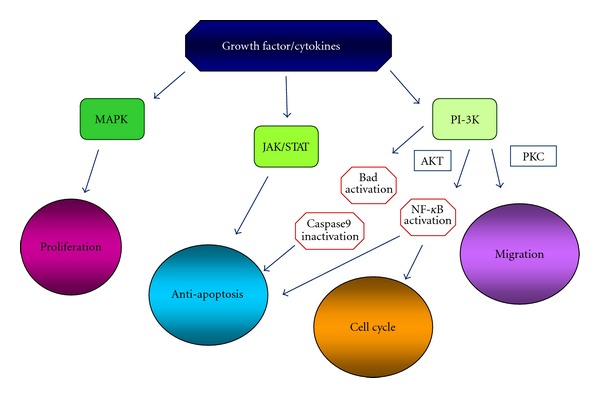

Binding of the cytokines to their receptors, expressed on malignant PCs, leads to activation of mitogenic/antiapoptotic pathways (mitogen actived protein kinase [MAPK], janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription [JAK/STAT], phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases/protein kinase B [PI-3K/Akt] and inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase [IKK/NF-kB]) [37], which promote cell proliferation, survival, cycle progression and migration. Survival is also mediated by increased transcription of antiapoptotic molecules (B cell lymphoma gene-2 [Bcl-2] family members such as B-cell lymphoma-extra large [Bcl-xL], myeloid cell factor-1 [Mcl-1] and caspase inhibitor such as Fas-Associated protein with Death Domain-like [FADD-like] IL-1β-converting enzyme (FLICE) inhibitor protein (FLIP) and cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein 2 (cIAP-2)) in malignant PCs which act along with disregulated cyclins whose expression is further upregulated by NF-kB activation [51–54]. Overall, cytokines present in the BM milieu, reflecting the PC-BMSC bidirectional interactions, mediate growth (IL-6, IGF-1, VEGF), survival (IL-6, IGF-1), drug resistance (IL-6, IGF-1, VEGF), and migration (IGF-1, VEGF, SDF1α) of neoplastic cells as well as angiogenesis (VEGF, b-FGF) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Signaling pathways activated by BM cytokines.

Because of its pleiotropic properties, lenalidomide interferes with several pathogenetic relevant moments associated to different clinical phases of MM.

First of all, lenalidomide upregulates the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (p21/waf1), a key cell cycle regulator that modulates the activity of cyclin dependent kinase (CDKs) [55]. Recently it has been demonstrated that lenalidomide mediates the increased expression of p21 by an epigenetic mechanism [56]. Lenalidomide reduces histone methylation and increases histone acetylation of the p21 promoter, thus enhancing transcription factor access to the DNA. In addition to upregulation of p21, lenalidomide-mediated growth inhibition has been demonstrated to be associated with the induction of CDK inhibitors p15, p16 and p27 and the early response transcription factors Egr1, Egr2 and Egr3 [57]. In MM derived cell lines, U266 and LP-1, reduction in CDK2 activity has been demonstrated after exposure to lenalidomide [55].

Lenalidomide inhibits the production of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-12 and increases the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. IMiDs have an opposite effect on IL-12 production, depending on the different type of stimulation on peripheral blood mononuclear cells [58].

Lenalidomide also downregulates adhesion molecules. This effect is mediated by the inhibition of TNFα production [50]. Thus, lenalidomide ultimately suppresses a positive feedback loop which upregulates the expression of cell surface adhesion molecules on both BMSCs and malignant PCs. Moreover the downregulation of PC adherence to BMSCs reduces the production of cytokines by these cells (IL-6, VEGF, IGF-1) which, as previously indicated, are responsible for thegrowth and survival of neoplastic clone. Lenalidomide also reduces the production of IL-6 by a direct action [59].

Increased micro-vascular density has been reported to correlate with MM-progression [60]. VEGF is produced by malignant PCs and BMSCs and accounts, at least in part, for increased angiogenesis in the BM of MM patients [60]. All IMiDs, including lenalidomide, possess antiangiogenic activity. This effect appears to occur via the modulation of TNFα, VEGF and b-FGF, which regulate endothelial cell migration, rather than cell proliferation. Antiangiogenesis by lenalidomide correlates with reduced Akt phosphorylation in response to both VEGF and bFGF [61]. Beyond the anti-angiogenesis, the lenalidomide induced-inhibition of VEFG and bFGF production determines other biological effects. In fact, these growth factors upregulate the production by BMSCs of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-6.

Apoptosis is triggered by the activation of both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. Besides, the success of this process is also related to the down-regulation of inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) activity. In malignant PCs, caspase 8 is activated in response to extracellular apoptosis-inducing ligand (i.e., FADD) [62]. Lenalidomide is able to induce caspase 8 activity which in turn results in increased malignant PC apoptosis [62]. Bcl-2 homology domains (BH3) interacting domain death agonist (Bid) can mediate a cross-talk of apoptotic signaling from caspase 8 to caspase 9 [63]. On the other hand,dexamethasone induced apoptosis in MM cells is associated with caspase 9 activation and release of second mitochondrial-derived activator of caspases (Smac) [64]. Moreover, long term treatment of malignant PCs with lenalidomide determines a downregulation of NF-kB activity, which results in a reduction of antiapoptotic proteins including cIAP2 [65] and FLIP [66]. Thus, lenalidomide induced apoptosis is the result of multiple effects consisting in the direct upregulation of caspase 8 activity, indirect upregulation of caspase 9 and the downregulation of NF-kB activity which, in turn, determines the inhibition of FLIP and cIAP2 and antagonizes prosurvival effects mediated by several cytokines (IL-6 and IGF-1). NF-kB is activated by IL-6 and determines the production of antiapoptotic proteins. Consequently, lenalidomide, by inactivating NF-kB, inihibits the antiapoptotic activity induced by IL-6.

Defective host immune surveillance has a central role in the survival of malignant PCs [67]. The mechanism responsible for myeloma cell tolerance includes the immunosuppressive activity of cytokines such as TGF-β derived by malignant PCs [68], reduced numbers of CD4+ T-cells [69], impaired cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell responses [70], defective antigen presentation, disfunction of human natural killer-T (NK-T) and natural killer (NK) [71, 72] cells as well as resistance to NK cell lysis [73].

Lenalidomide acts at different levels in the immune system by modifying cytokine production, improving T-cell activity, regulating T-cell co-stimulation and augmenting the NK-T- and NK-cell cytotoxicity. Lenalidomide enhances the cytolytic activity of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cells. This effect has been demonstrated in a dendritic cell/CD8+ T-cell in vitro co-culture system. It appears to be mediated by IL-2 induced expansion of antigen-specific memory effector CD8+ T-cells [74].

T-cell activation requires the presentation of the peptide fragments by antigen presenting cell (APC) to the T-cell receptor (TCR). Moreover to generate an effective response against the antigen, a secondary interaction is required [75]. This is mediated by the B7 family molecules on APC and CD28 molecule on the T-cell surface and provide the costimulatory signal that augments and potentiates T-cell proliferation, differentiation and survival followed by IL-2 and IFNγ production. In MM patients the number of dendritic cells (DCs) is normal, but CD80 (B7-1) expression may fail to be upregulated in the presence of trimeric human CD40-ligand (HU-CD40LT) because of the negative effect of tumor-derived TGF-β or IL-10 [76]. Impairment of T all activation by DCs is also mediated by IL-6 [77] and VEGF [78] of PC or BMSC origin. IMiDs including lenalidomide are only able to stimulate T-cells that have been partially activated by either anti-CD3 or DCs [75]. Lenalidomide induces the proliferation of partially activated CD3+ T cells obtained from human PBMC. T-cell proliferation is associated with increased IL-2 and INFγ production. The mechanism of T-cell co-stimulation by lenalidomide involves increased transcriptional activity of activated protein-1 (AP-1), a driver of IL-2 production [79]. In addition, this drug abrogates the requirement of a secondary co-stimulation signal from APCs to allow T-cell activation. In fact, it acts on T-cells via the B7-CD28 costimulatory pathway directly inducing tyrosine phosphorylation of CD28 on T-cells leading to the activation of downstream targets such as PI3K-signaling pathway and the nuclear translocation of the nuclear factor of activated T cells-2 (NFAT-2) [75, 80].

NK-T- and NK-cells belong to distinct lymphocyte lineages. However, these cells share striking similarities such as the expression of the same set of receptors (NKR-P1 and Ly49) and the capacity to rapidly release, without prior sensitization, INFγ and IL-4 (NK-T) or INFγ alone (NK) [81, 82]. IL-12 can modulate both NK-T-cells [83, 84] and NK-cells [85] to release INFγ and exert natural cytotoxicity. NK-T-cells are distinct lymphocytes, which often use a restricted T cell receptor (Vα24-Vβ11) that recognizes glicolipid ligands in the context of the major histocompatibility class 1-like CD1d molecule. The anti-tumor properties of these cells include a direct cytotoxic effect of neoplastic cells, INFγ production and interaction with DC expressing glicolipid ligands. Lenalidomide increases the NK-T-cell expansion mediated by DCs loaded with α GalCer and INFγ production from NK-T-cells [86]. Because of the cross-talk between NK-T- and NK-cells, NK-T-cells transact with NK-cells. This network of activation later involves B and T cells indicating the sequential recruitment of distinct and adaptive effector lymphocytes [87]. Lenalidomide might potentiate the function of these other immune cells, using the transactivation mediated by NK-T-cells.

Lenalidomide not only increases NK-cell proliferation, but also potentiates natural and antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) of NK-cells [88]. These effects are mediated by lenalidomide-induced IL-2 production by T cells. More in detail, lenalidomide triggers PI3K activation of AP-1 and related increased IL-2 secretion by T cells [88]. IL-2 in turn activates NK-cells.

Bone remodelling is a tightly regulated process. The binding of receptor activator of NF-kB ligand (RANKL), on BMSCs and OBLs, to its receptor RANK, on mature OCLs and their precursors, stimulates OCL late differentiation and activity. Osteoprotegerin (OPG), a decoy receptor for RANKL, is produced by OBLs. OPG inhibits RANK-RANKL interaction, thus suppressing osteoclastogenesis [89]. Several cytokines and chemokines [IL-6, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-11, macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF), TNF-α, TNF-β, macrophage inflammatory proteins-1α and -β (MIP-1α, -β) and VEGF], which possess pro-osteoclastogenic activity, as previously mentioned, are present in the BM milieu. Other molecules, as SDF-1α, IL-3 and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), secreted by both malignant PCs and BMSCs, stimulate the expression of RANKL by BMSCs and thus enhance osteoclastogenesis. In MM, OPG production is downregulated. In addition, malignant PCs internalize and degradate OPG. This vicious cycle determines an increased RANK-RANL binding, augments OCL differentiation and proliferation and favours bone resorption [90]. Moreover, OBL activity is impaired in MM. In fact, malignant PCs suppress OBL differentiation and induce mature OBL apoptosis through the production of dickkopf-1 (DKK-1) and soluble frizzle-related protein-2 (sFRP-2). These molecules inhibit the Wingless-type (Wnt) signaling pathway, which promotes OBL differentiation. Other molecules, such as IL-7, IL-3 and TGF-β, overexpressed in MM BM milieu, also downregulate the OBL maturation [91].

Lenalidomide has been reported to reduce osteoclastogenesis in MM [91]. This effect is achieved in a dose-dependent manner through the inhibition of the transcription factor PU.1 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). The first one is an early activator of osteoclastogenesis; the second one plays a key role in OCL survival and differentiation. In MM patients, after treatment with lenalidomide, OPG levels were significantly higher than baseline (P < 0, 05), whereas RANKL production was inhibited, so lenalidomide has been confirmed to reduce the serum markers of bone lytic disease.

Although all the above mentioned mechanisms explain the direct and indirect anti-myeloma effect of lenalidomide, the precise molecular mechanisms and targets through which this molecule exerts its effects remain not completely understood.

A seminal paper has recently identified cereblon (CRBN) as a primary target of thalidomide teratogenecity [92] and moreover an essential element for response to lenalidomide [93]. Human CRBN is a 51 kDa protein that is localized in cytoplasm, nucleus and peripheral membrane of cells in testis, spleen, prostate, liver, pancreas, placenta, kidney, lung, skeletal muscle, ovary, small intestine, peripheral blood leukocytes, colon, brain and retina [94]. CRBN links to DNA damage-binding protein 1 (DDB1) [92]. DDB1 is a nucleotide excision repair protein which binds to DDB2 leading to set up a heterodimer. It is part of the cullin-4 (Cul4)-based E3 ubiquitin protein ligase complex. This complex is formed by DDB1, Cul4 (Cul4A and Cul4B), regulator of cullins-1 (Roc1) and a substrate receptor. Cul4-based E3 ubiquitin protein ligase complex plays a relevant role in cell cycle regulation, carcinogenesis and embryogenesis [95, 96]. CRBN is a part of the Cul4-based complex and it competes with DDB2 in binding to DDB1. CRBN-complex has auto-ubiquitination properties, which are inhibited by thalidomide, as shown in in vitro-studies.

Several in vitro studies have shown that CRBN is also the target molecule of lenalidomide activity.

Zhu et al. have clearly demonstrated in human MM cell lines (HMMCLs) the central role of CRBN in sensitivity and resistance to lenalidomide and have identified interferon regulatory factor-4 (IRF-4) as one of the downstream targets of CRBN. IRF-4 has previously reported to also be a target of and downregulated by lenalidomide [93].

Lopez-Girona et al. have demonstrated that lenalidomide binds to CRBN-DDB1 complex in a dose-dependent manner and with a ten-fold higher affinity than thalidomide. Moreover, after reducing CRBN expression by short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) in activated human T cells, lenalidomide has increased IL-2 and TNF-α production by these cells, thus suggesting that some immunomodulatory effects of lenalidomide are mediated by CRBN complex. This study has also shown that induction of p21/waf1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor protein is prevented in absence of CRBN expression, indicating a role of CRBN in mediating antiproliferative effects of lenalidomide [97].

Heintel et al. have found a significant relationship between CRBN expression and response to lenalidomide in 44 MM patients. In fact, CRBN expression resulted three times higher in responding patients compared to non-responders. Moreover, this study has shown a clear correlation between CRBN levels and quality of response. CRBN expression was lower in patients with stable or progressive disease and higher in patients with complete remission or partial responses [98].

The data emerging from in vitro studies as well as the in vivo findings about the role of CRBN in lenalidomide action wait to be confirmed.

3. Conclusions

IMiDs including lenalidomide have proven therapeutically effective molecules in several malignant diseases characterized by different hystogenetic origin of neoplastic cells, as well as by distinct phatogenetic pathways. Notwithstanding these differences IMiDs activity in the diverse neoplasia can be traced back to the pleiotropic mechanism of these molecules.

Lenalidomide exerts a direct antitumor effect, interferes with the tumor microenvironment and enhances the host's antitumor immune responses. In MM, because of the complex bidirectional cross-talk between malignant PCs and the BM milieu including the BMSCs, the ECM proteins and the multitude of cytokines secreted in the BM milieu, the final effects of lenalidomide are the results of additional or synergic actions on different relevant pathogenetic events operating in this disease.

In addition, lenalidomide activates caspase 8 and downregulates NF-kB activity induced by cytokines secreted in the BM milieu. This in turn determines reduced expression of antiapoptotic proteins. Thus, relevant in the lenalidomide apoptosis is also the modulation induced by this drug on adhesion molecules on PCs and BMSCs as well as on cytokines production. The anti-angiogenetic well known properties of IMiDs, including lenalidomide, might be relevant in MM as increased microvascular density has been reported to be associated with disease progression. Furthermore, lenalidomide acts on different host's effector immune cells. However the immune-mediated antitumor activity well defined in vitro are not completely correlated with the clinical outcome because of the complex immunosuppressive activity of underlying disease as well as of conventional antitumor drugs.

Finally, lenalidomide downregulates bone resorption.

The molecular mechanisms and targets of lenalidomide remain largely unknown. However, CRBN has recently been identified as the possible central mediator of lenalidomide activity and IRF-4 as a downstream molecule of CRBN action. Lenalidomide resistance in MM cells which, despite CRBN depletion, are able to restore their IRF-4 levels, suggest the existence of alternative pathways.

References

- 1.Corral LG, Kaplan G. Immunomodulation by thalidomide and thalidomide analogues. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 1999;58(supplement 1):I107–I113. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.2008.i107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.List A, Kurtin S, Roe DJ, et al. Efficacy of lenalidomide in myelodysplastic syndromes. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352(6):549–557. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.List AF. Lenalidomide: from bench to bedside (part 1) Cancer Control. 2006;13(supplement 2-3) doi: 10.1177/107327480601304s01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.List AF, Baker AF, Green S, Bellamy W. Lenalidomide: targeted anemia therapy for myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Control. 2006;13(supplement 4–11) doi: 10.1177/107327480601304s02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raza A, Reeves JA, Feldman EJ, et al. Phase 2 study of lenalidomide in transfusion-dependent, low-risk, and intermediate-1-risk myelodysplastic syndromes with karyotypes other than deletion 5q. Blood. 2008;111(1):86–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-068833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.List A, Dewald G, Bennett J, et al. Lenalidomide in the myelodysplastic syndrome with chromosome 5q deletion. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355(14):1456–1465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tariman JD. Lenalidomide: a new agent for patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2007;11(4):569–574. doi: 10.1188/07.CJON.569-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber DM, Chen C, Niesvizky R, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma in North America. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(21):2133–2142. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baz R, Walker E, Karam MA, et al. Lenalidomide and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-based chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: safety and efficacy. Annals of Oncology. 2006;17(12):1766–1771. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niesvizky R, Jayabalan DS, Christos PJ, et al. BiRD (Biaxin [clarithromycin]/revlimid [lenalidomide]/dexamethasone) combination therapy results in high complete- and overall-response rates in treatment-naive symptomatic multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111(3):1101–1109. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-090258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajkumar SV, Hayman S, Nowakowski GS, et al. Combination therapy with thalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma not undergoing upfront autologous stem cell transplantation: a phase II trial. Haematologica. 2005;90(12):1650–1654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palumbo A, Falco P, Corradini P, et al. Melphalan, prednisone, and lenalidomide treatment for newly diagnosed myeloma: a report from the GIMEMA—Italian Multiple Myeloma Network. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2007;25(28):4459–4465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chanan-Khan A, Miller KC, Musial L, et al. Clinical efficacy of lenalidomide in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of a phase II study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(34):5343–5349. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chanan-Khan A, Porter CW. Immunomodulating drugs for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Lancet Oncology. 2006;7(6):480–488. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramsay AG, Johnson AJ, Lee AM, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia T cells show impaired immunological synapse formation that can be reversed with an immunomodulating drug. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118(7):2427–2437. doi: 10.1172/JCI35017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrajoli A, Lee BN, Schlette EJ, et al. Lenalidomide induces complete and partial remissions in patients with relapsed and refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;111(11):5291–5297. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, Zeldenrust SR, et al. The activity of lenalidomide with or without dexamethasone in patients with primary systemic amyloidosis. Blood. 2007;109(2):465–470. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-032987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gertz MA, Comenzo R, Falk RH, et al. Definition of organ involvement and treatment response in immunoglobulin light chain amyloidosis (AL): a consensus opinion from the 10th International Symposium on Amyloid and Amyloidosis. American Journal of Hematology. 2005;79(4):319–328. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiernik PH, Lossos IS, Tuscano JM, et al. Lenalidomide monotherapy in relapsed or refractory aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(30):4952–4957. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tefferi A, Cortes J, Verstovsek S, et al. Lenalidomide therapy in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. Blood. 2006;108(4):1158–1164. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Treon SP, Patterson CJ, Hunter ZR, Branagan AR. Phase II study of CC-5013 (revlimid) and rituximab in Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: preliminary safety and efficacy results. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2005;106(11, abstract 2443) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chanan-Khan AA, Cheson BD. Lenalidomide for the treatment of B-cell malignancies. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26(9):1544–1552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zangari MTG, Zeldis J, Eddlemon P, Saghafifar F, Barlogie B. Results of phase I study of CC-5013 for the treatment of multiple myeloma (MM) patients who relapse after high dose chemotherapy (HDCT) Blood. 2001;98, abstract 775a [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richardson PG, Schlossman RL, Weller E, et al. Immunomodulatory drug CC-5013 overcomes drug resistance and is well tolerated in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2002;100(9):3063–3067. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richardson PG, Blood E, Mitsiades CS, et al. A randomized phase 2 study of lenalidomide therapy for patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;108(10):3458–3464. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dimopoulos M, Spencer A, Attal M, et al. Lenalidomide plus dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357(21):2123–2132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dimopoulos MA, Chen C, Spencer A, et al. Long-term follow-up on overall survival from the MM-009 and MM-010 phase III trials of lenalidomide plus dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2009;23(11):2147–2152. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajkumar SV, Jacobus S, Callander NS, et al. Lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone versus lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone as initial therapy for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: an open-label randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2010;11(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70284-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palumbo A, Cavallo F, Hardan I, et al. A phase III study to compare melphalan, prednisone, lenalidomide (MPR) versus melphalan 200 mg/m2 and autologous transplantation (MEL200) in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. Blood. 2010;116, abstract 3573 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zonder JA, Crowley J, Hussein MA, et al. Lenalidomide and high-dose dexamethasone compared with dexamethasone as initial therapy for multiple myeloma: a randomized Southwest Oncology Group trial (S0232) Blood. 2010;116(26):5838–5841. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-303487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gay F, Rajkumar SV, Coleman M, et al. Clarithromycin (Biaxin)-lenalidomide-low-dose dexamethasone (BiRd) versus lenalidomide-low-dose dexamethasone (Rd) for newly diagnosed myeloma. American Journal of Hematology. 2010;85(9):664–669. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richardson PG, Weller E, Lonial S, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone combination therapy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;116(5):679–686. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-268862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knop S, Langer C, Engelhardt M, et al. The efficacy and safety of RAD (lenalidomide, adriamycin and dexamethasone) in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma—first results of a phase II trial by the German DSMM Group. Blood. 2010;116, abstract 1945 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumar SK, Flinn I, Noga SJ, et al. Novel three-and four drug combination regimens of bortezomib, dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, and lenalidomide, for previously untreated multiple myeloma: results from the multicenter, randomized, phase 2 EVOLUTION Study. Blood. 2010;116, abstract 621 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jakubowiak AJ, Reece DE, Hofmeister CC, et al. Lenalidomide, bortezomib, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, and dexamethasone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: updated results of phase I/II MMRC trial. Blood. 2009;114, abstract 132 doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-334755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuehl WM, Bergsagel PL. Multiple myeloma: evolving genetic events and host interactions. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2(3):175–187. doi: 10.1038/nrc746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hideshima T, Bergsagel PLI, Kuehl WM, Anderson KC. Advances in biology of multiple myeloma: clinical applications. Blood. 2004;104(3):607–618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bergsagel PL, Kuehl WM. Critical roles for immunoglobulin translocations and cyclin D dysregulation in multiple myeloma. Immunological Reviews. 2003;194:96–104. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urashima M, Teoh G, Ogata A, et al. Characterization of p16(INK4A) expression in multiple myeloma and plasma cell leukemia. Clinical Cancer Research. 1997;3(11):2173–2179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guillerm G, Gyan E, Wolowiec D, et al. p16INK4a and p15INK4b gene methylations in plasma cells from monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. Blood. 2001;98(1):244–246. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.1.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kulkarni MS, Daggett JL, Bender TP, Kuehl WM, Bergsagel PL, Williams ME. Frequent inactivation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p18 by homozygous deletion in multiple myeloma cell lines: ectopic p18 expression inhibits growth and induces apoptosis. Leukemia. 2002;16(1):127–134. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teoh G, Anderson KC. Interaction of tumor and host cells with adhesion and extracellular matrix molecules in the development of multiple myeloma. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 1997;11(1):27–42. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Hayashi T, et al. The biological sequelae of stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha in multiple myeloma. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2002;1(7):539–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Damiano JS, Cress AE, Hazlehurst LA, Shtil AA, Dalton WS. Cell adhesion mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR): role of integrins and resistance to apoptosis in human myeloma cell lines. Blood. 1999;93(5):1658–1667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hazlehurst LA, Damiano JS, Buyuksal I, Pledger WJ, Dalton WS. Adhesion to fibronectin via β1 integrins regulates p27(kip1) levels and contributes to cell adhesion mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR) Oncogene. 2000;19(38):4319–4327. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chauhan D, Uchiyama H, Akbarali Y, et al. Multiple myeloma cell adhesion-induced interleukin-6 expression in bone marrow stromal cells involves activation of NF-κB. Blood. 1996;87(3):1104–1112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dankbar B, Padró T, Leo R, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin-6 in paracrine tumor- stromal cell interactions in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2000;95(8):2630–2636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gupta D, Treon SP, Shima Y, et al. Adherence of multiple myeloma cells to bone marrow stromal cells upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor secretion: therapeutic applications. Leukemia. 2001;15(12):1950–1961. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klein B, Zhang XG, Jourdan M, et al. Paracrine rather than autocrine regulation of myeloma-cell growth and differentiation by interleukin-6. Blood. 1989;73(2):517–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hideshima T, Chauhan D, Schlossman R, Richardson P, Anderson KC. The role of tumor necrosis factor α in the pathophysiology of human multiple myeloma: therapeutic applications. Oncogene. 2001;20(33):4519–4527. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Catlett-Falcone R, Landowski TH, Oshiro MM, et al. Constitutive activation of Stat3 signaling confers resistance to apoptosis in human U266 myeloma cells. Immunity. 1999;10(1):105–115. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Puthier D, Bataille R, Amiot M. IL-6 up-regulates mcl-1 in human myeloma cells through JAK / STAT rather than ras / MAP kinase pathway. European Journal of Immunology. 1999;29(12):3945–3950. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199912)29:12<3945::AID-IMMU3945>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jourdan M, Veyrune JL, De Vos J, Redal N, Couderc G, Klein B. A major role for Mcl-1 antiapoptotic protein in the IL-6-induced survival of human myeloma cells. Oncogene. 2003;22(19):2950–2959. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang B, Gojo I, Fenton RG. Myeloid cell factor-1 is a critical survival factor for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2002;99(6):1885–1893. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verhelle D, Corral LG, Wong K, et al. Lenalidomide and CC-4047 inhibit the proliferation of malignant B cells while expanding normal CD34+ progenitor cells. Cancer Research. 2007;67(2):746–755. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Escoubet-Lozach L, Lin IL, Jensen-Pergakes K, et al. Pomalidomide and lenalidomide induce p21WAF-1 expression in both lymphoma and multiple myeloma through a LSD1-mediated epigenetic mechanism. Cancer Research. 2009;69(18):7347–7356. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gandhi AK, Kang J, Capone L, et al. Dexamethasone synergizes with lenalidomide to inhibit multiple myeloma tumor growth, but reduces lenalidomide-induced immunomodulation of T and NK cell function. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 2010;10(2):155–167. doi: 10.2174/156800910791054239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Corral LG, Haslett PA, Muller GW, et al. Differential cytokine modulation and T cell activation by two distinct classes of thalidomide analogues that are potent inhibitors of TNF-α . Journal of Immunology. 1999;163(1):380–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kotla V, Goel S, Nischal S, et al. Mechanism of action of lenalidomide in hematological malignancies. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2009;2, article 36 doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-2-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu JL, Lai R, Kinoshita T, Nakashima N, Nagasaka T. Proliferation, apoptosis, and intratumoral vascularity in multiple myeloma: correlation with the clinical stage and cytological grade. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2002;55(7):530–534. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.7.530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dredge K, Horsfall R, Robinson SP, et al. Orally administered lenalidomide (CC-5013) is anti-angiogenic in vivo and inhibits endothelial cell migration and Akt phosphorylation in vitro. Microvascular Research. 2005;69(1-2):56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chauhan D, Hideshima T, Anderson KC. Apoptotic signaling in multiple myeloma: therapeutic implications. International Journal of Hematology. 2003;78(2):114–120. doi: 10.1007/BF02983378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dai Y, Dent P, Grant S. Tumor necrosis factorrelated apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) promotes mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis induced by 7-hydroxystaurosporine and mitogenactivated protein kinase kinase inhibitors in human leukemia cells that ectopically express Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. Molecular Pharmacology. 2003;64(6):1402–1409. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.6.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chauhan D, Hideshima T, Rosen S, Reed JC, Kharbanda S, Anderson KC. Apaf-1/cytochrome c independent and Smac dependent induction of apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(27):24453–24456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100074200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chu ZL, McKinsey TA, Liu L, Gentry JJ, Malim MH, Ballard DW. Suppression of tumor necrosis factor-induced cell death by inhibitor of apoptosis c-IAP2 is under NF-κB control. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(19):10057–10062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kreuz S, Siegmund D, Scheurich P, Wajant H. NF-κB inducers upregulate cFLIP, a cycloheximide-sensitive inhibitor of death receptor signaling. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2001;21(12):3964–3973. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.12.3964-3973.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zou W. Immunosuppressive networks in the tumour environment and their therapeutic relevance. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2005;5(4):263–274. doi: 10.1038/nrc1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Urashima M, Ogata A, Chauhan D, et al. Transforming growth factor-β1: differential effects on multiple myeloma versus normal B cells. Blood. 1996;87(5):1928–1938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ogawara H, Handa H, Yamazaki T, et al. High Th1/Th2 ratio in patients with multiple myeloma. Leukemia Research. 2005;29(2):135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maecker B, Anderson KS, von Bergwelt-Baildon MS, et al. Viral antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses are impaired in multiple myeloma. British Journal of Haematology. 2003;121(6):842–848. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dhodapkar MV, Geller MD, Chang DH, et al. A reversible defect in natural killer T cell function characterizes the progression of premalignant to malignant multiple myeloma. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;197(12):1667–1676. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI, Trapani JA. A fresh look at tumor immunosurveillance and immunotherapy. Nature Immunology. 2001;2(4):293–299. doi: 10.1038/86297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jarahian M, Watzl C, Issa Y, Altevogt P, Momburg F. Blockade of natural killer cell-mediated lysis by NCAM140 expressed on tumor cells. International Journal of Cancer. 2007;120(12):2625–2634. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Haslett PA, Hanekom WA, Muller G, Kaplan G. Thalidomide and a thalidomide analogue drug costimulate virus-specific CD8+ T cells in vitro. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2003;187(6):946–955. doi: 10.1086/368126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.LeBlanc R, Hideshima T, Catley LP, et al. Immunomodulatory drug costimulates T cells via the B7-CD28 pathway. Blood. 2004;103(5):1787–1790. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brown RD, Pope B, Murray A, et al. Dendritic cells from patients with myeloma are numerically normal but functionally defective as they fail to up-regulate CD80 (B7-1) expression after huCD40LT stimulation because of inhibition by transforming growth factor-β1 and interleukin-10. Blood. 2001;98(10):2992–2998. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.10.2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ratta M, Fagnoni F, Curti A, et al. Dendritic cells are functionally defective in multiple myeloma: the role of interleukin-6. Blood. 2002;100(1):230–237. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gabrilovich DI, Chen HL, Girgis KR, et al. Production of vascular endothelial growth factor by human tumors inhibits the functional maturation of dendritic cells. Nature Medicine. 1996;2(10):1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Schafer PH, Gandhi AK, Loveland MA, et al. Enhancement of cytokine production and AP-1 transcriptional activity in T cells by thalidomide-related immunomodulatory drugs. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2003;305(3):1222–1232. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.048496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hayashi T, Hideshima T, Akiyama M, et al. Molecular mechanisms whereby immunomodulatory drugs activate natural killer cells: clinical application. British Journal of Haematology. 2005;128(2):192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bendelac A, Rivera MN, Park SH, Roark JH. Mouse CD1-specific NK1 T cells: development, specificity, and function. Annual Review of Immunology. 1997;15:535–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Biron CA, Nguyen KB, Pien GC, Cousens LP, Salazar-Mather TP. Natural killer cells in antiviral defense: function and regulation by innate cytokines. Annual Review of Immunology. 1999;17:189–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Takeda K, Seid S, Ogasawara K, et al. Liver NK1.1+ CD4+ αβ T cells activated by IL-12 as a major effector in inhibition of experimental tumor metastasis. Journal of Immunology. 1996;156(9):3366–3373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cui J, Shin T, Kawano T, et al. Requirement for V(α)14 NKT cells in IL-12-mediated rejection of tumors. Science. 1997;278(5343):1623–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Trinchieri G, Scott P. Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions. Research in Immunology. 1995;146(7-8):423–431. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(96)83011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fujii S, Shimizu K, Steinman RM, Dhodapkar MV. Detection and activation of human Vα24+ natural killer T cells using α-galactosyl ceramide-pulsed dendritic cells. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2003;272(1-2):147–159. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Carnaud C, Lee D, Donnars O, et al. Cutting edge: cross-talk between cells of the innate immune system: NKT cells rapidly activate NK cells. Journal of Immunology. 1999;163(9):4647–4650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hayashi T, Hideshima T, Akiyama M, et al. Molecular mechanisms whereby immunomodulatory drugs activate natural killer cells: clinical application. British Journal of Haematology. 2005;128(2):192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Takahashi N, Maeda K, Ishihara A, Uehara S, Kobayashi Y. Regulatory mechanism of osteoclastogenesis by RANKL and Wnt signals. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2011;16(1):21–30. doi: 10.2741/3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Terpos E, Dimopoulos MA, Sezer O. The effect of novel anti-myeloma agents on bone metabolism of patients with multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2007;21(9):1875–1884. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Breitkreutz I, Raab MS, Vallet S, et al. Lenalidomide inhibits osteoclastogenesis, survival factors and bone-remodeling markers in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22(10):1925–1932. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Takumi I, Hiroshi H. Deciphering the mystery of thalidomide teratogenicity. Congenital Anomalies. 2012;52(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-4520.2011.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhu YX, Braggio E, Shi CX, et al. Cereblon expression is required for the antimyeloma activity of lenalidomide and pomalidomide. Blood. 2011;118(18):4771–4779. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-356063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chang XB, Stewart AK. What is the functional role of the thalidomide binding protein cereblon? International Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2011;2(3):287–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cang Y, Zhang J, Nicholas SA, et al. Deletion of DDB1 in mouse brain and lens leads to p53-dependent elimination of proliferating cells. Cell. 2006;127(5):929–940. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cang Y, Zhang J, Nicholas SA, Kim AL, Zhou P, Goff SP. DDB1 is essential for genomic stability in developing epidermis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(8):2733–2737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611311104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lopez-Girona A, Mendy D, Miller K, et al. Direct binding with cereblon mediates the antiproliferative and immunomodulatory action of lenalidomide and pomalidomide. Proceedings of the ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Heintel D, Bolomsky A, Schreder M, et al. High expression of the thalidomide-binding protein cereblon (CRBN) is associated with improved clinical response in patients with multiple myeloma treated with lenalidomide and dexamethasone. Proceedings of the ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition; 2011; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]