Abstract

Context:

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 8 is important for GnRH neuronal development with human mutations resulting in Kallmann syndrome. Murine data suggest a role for Fgf8 in hypothalamo-pituitary development; however, its role in the etiology of wider hypothalamo-pituitary dysfunction in humans is unknown.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to screen for FGF8 mutations in patients with septo-optic dysplasia (n = 374) or holoprosencephaly (HPE)/midline clefts (n = 47).

Methods:

FGF8 was analyzed by PCR and direct sequencing. Ethnically matched controls were then screened for mutated alleles (n = 480–686). Localization of Fgf8/FGF8 expression was analyzed by in situ hybridization in developing murine and human embryos. Finally, Fgf8 hypomorphic mice (Fgf8loxPNeo/−) were analyzed for the presence of forebrain and hypothalamo-pituitary defects.

Results:

A homozygous p.R189H mutation was identified in a female patient of consanguineous parentage with semilobar HPE, diabetes insipidus, and TSH and ACTH insufficiency. Second, a heterozygous p.Q216E mutation was identified in a female patient with an absent corpus callosum, hypoplastic optic nerves, and Moebius syndrome. FGF8 was expressed in the ventral diencephalon and anterior commissural plate but not in Rathke's pouch, strongly suggesting early onset hypothalamic and corpus callosal defects in these patients. This was consolidated by significantly reduced vasopressin and oxytocin staining neurons in the hypothalamus of Fgf8 hypomorphic mice compared with controls along with variable hypothalamo-pituitary defects and HPE.

Conclusion:

We implicate FGF8 in the etiology of recessive HPE and potentially septo-optic dysplasia/Moebius syndrome for the first time to our knowledge. Furthermore, FGF8 is important for the development of the ventral diencephalon, hypothalamus, and pituitary.

Complex midline defects of the forebrain in humans are rare but may be associated with hypopituitarism, which in turn may lead to significant morbidity and mortality. They span a wide spectrum of phenotypes ranging from those which are incompatible with life, to holoprosencephaly (HPE) and cleft palate and septo-optic dysplasia (SOD).

SOD is a highly heterogeneous condition which, although usually sporadic and inclusive of possible environmental (including drug and alcohol induced) pathologies, has also been identified in a number of familial cases involving mutations in an increasing number of early developmental transcription factors including HESX1, SOX2, SOX3, and OTX2 (1–5). These genes are expressed in regions that determine the formation of forebrain and related midline structures such as the hypothalamus and pituitary (6). Consequently, SOD is characterized by variable phenotypes including midline telencephalic abnormalities, optic nerve hypoplasia, and pituitary hypoplasia with variable pituitary hormone deficiencies (7, 8).

HPE is etiologically heterogeneous but is the most frequent developmental forebrain anomaly in humans, with an incidence in liveborns of approximately one in 10,000–20,000 and in conceptuses as high as one in 250 (9). It results from varying degrees of incomplete cleavage of the prosencephalon into the cerebral hemispheres and ventricles. In addition, failure of the frontal and parietal lobes to divide posteriorly results in an absent corpus callosum. Facial features associated with HPE include cyclopia, anophthalmia, midface hypoplasia, hypotelorism, cleft lip and/or palate, and a single central incisor (10).

Recent studies have implicated a number of heterozygous genetic missense mutations and deletions in the etiology of HPE; cytogenetically visible abnormalities are estimated to be present in 25% of HPE patients (11). These in turn have led to the identification of a number of causative genes, including SHH, ZIC2, SIX3, and TGIF1 with subsequent identification of mutated genes in associated pathways including PTCH1, GLI2, DISP1, TDGF1, GAS1, EYA4, and FOXH1 (12–14). However, mutations have been identified in only 17% of cytogenetically normal children with HPE. In recent studies, submicroscopic deletions of a number of loci believed to be implicated in HPE were identified in a number of individuals with HPE (15), suggesting that a number of genetic mutations remain to be described.

Although not previously related to hypopituitarism, Kallmann syndrome is classically defined as the association of hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism with anosmia due to hypoplasia of the olfactory bulbs (16). However, the condition is genetically and clinically heterogeneous and may be associated with craniofacial defects such as Moebius syndrome, which is characterized by malformation of the sixth and seventh facial nerves (17, 18). One of the genetic pathways involved in Kallmann syndrome is the ubiquitously expressed fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family of signaling molecules and its receptors (19). Loss-of-function mutations in human FGF8 and FGFR1 have been implicated in this condition, and these factors potentially link the disorder to hypopituitarism through the requirement of Fgf8 to maintain anterior pituitary cellular proliferation via Lhx3 in mice (20, 21). Recently a putative role for FGF8 in two patients with HPE has been postulated upon the identification of two heterozygous mutations: 1) a 138-kb deletion at 10q24.3 encompassing FGF8 as well as a number of other genes (15), and 2) a p.T229M substitution associated with incomplete penetrance, which has previously been described in association with isolated hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism (16, 22). Although the latter patient manifested diabetes insipidus, there was no other evidence of endocrine dysfunction in the two pedigrees.

We hypothesized that FGF8 may be essential for the development of the forebrain and pituitary gland in humans and mouse and that mutations in this gene may contribute to the etiology of disorders such as SOD and HPE.

Patients and Methods

Patients

A total of 421 patients with congenital hypopituitarism and midline craniofacial/forebrain defects (SOD or HPE) were recruited between 1998 and 2010; 167 patients (39.7%) were recruited at the London Centre for Pediatric Endocrinology based at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children and the University College London Hospital, and 157 (37.3%) were referred from national and 97 (23%) from international centers. Ethical committee approval was obtained from the University College London Institute of Child Health/Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children Joint Research Ethics Committee, and informed written consent was obtained from patients and/or parents. Of the 421 patients screened (male to female ratio 1.1:1), 88.8% (n = 374) had SOD and its variants, whereas 11.2% (n = 47) had HPE or midline clefts.

Mutation analysis

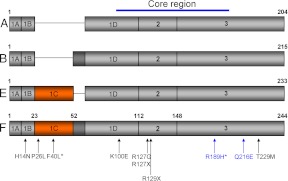

The coding region of human FGF8 (NM_033163) was amplified by PCR on an Eppendorf Thermocycler (Netheler, Germany) over 35 cycles with primers designed using the Primer3 program (available at http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3) flanking each of the coding regions, including the four alternative splice variants of exon 1 (Fig. 1). PCR parameters are available on request. For direct sequencing for mutations, PCR products were treated with MicroClean reagent (Web Scientific, Cheshire, UK; catalog no. 2MCL-10) according to manufacturer's instructions and then sequenced using BigDye version 1.1 sequencing chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) and analyzed on a 3730X1 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems/Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan; catalog no. 625-0020). Upon discovering FGF8 mutations, 480–686 controls were screened at the same allele to provide comparisons.

Fig. 1.

Structure of FGF8 isoforms. Schematic representation of the four FGF8 isoforms (A, B, E, and F) resulting from alternative splicing of exons 1C and 1D. The lettering refers to the specific FGF8 isoform. Exons are designated inside the rectangles and numbers above each exon-exon boundary indicate the amino acid position in the FGF8f isoform. The core region of the protein is predominantly made up of exons 2 and 3, which is conserved between isoforms. Previously identified mutations are indicated by arrows and numbered according to the FGF8f protein isoform, with the two novel mutations presented within this paper in blue type. Note that the asterisk denotes homozygous mutations. [Adapted from J. Falardeau et al.: Decreased FGF8 signaling causes deficiency of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in humans and mice. J Clin Invest 118:2822–2831, 2008 (16), with permission. © American Society for clinical Investigation; and E. Trarbach et al.: Nonsense mutations in FGF8 gene causing different degrees of human gonadotropin-releasing deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:3491–3496, 2010 (23), with permission. © The Endocrine Society.

In situ hybridization and hypomorphic mice

In situ hybridization was performed on paraffin sections from mouse and human embryos as previously described (24). Sections of human embryos were obtained from the Human Developmental Biology Resource (University College London Institute of Child Health, London, UK). The human FGF8 and FGFR1 probes were obtained from the Source BioScience LifeSciences (http://www.lifesci.ences.sourcebioscience.com/). The Fgf8 hypomorphic mouse embryos (Fgf8loxPNeo/−) were obtained by crossing the Fgf8+/− with Fgf8loxPNeo/+ line as has previously been described (25).

Immunohistochemistry and quantification of hypothalamic arginine vasopressin (AVP)-expressing nuclei

Brains from wild-type, heterozygote, and homozygote Fgf8 hypomorphic mouse embryos (Fgf8loxPNeo/−) were collected at postnatal day (PN) 0 and processed for immunohistochemistry on 50-μm frozen sections. Sections were taken from the preoptic area to the mamillary bodies, and neurons were stained for AVP using a rabbit anti-AVP antibody (Millipore, Billerica, CA; catalog no. AB1565) for 48 h at 4 C. These were then sequentially incubated with a biotinylated donkey antirabbit secondary antibody (1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) and the avidin-biotin complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Immunoreactivity was visualized with diaminobenzidine as the chromagen before counterstaining with methyl green.

Quantification of AVP-immunoreactive paraventricular nuclei (PVN) and suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) were conducted as recently described (26).

Statistical analysis

Treatments presented (see Fig. 4T) were compared with controls by ANOVA followed by Student Newman-Keuls test. P < 0.05 was used to determine whether results were statistically significant. All statistics were performed using SigmaStat version 3.5 (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA).

Fig. 4.

Mouse embryos carrying a Fgf8 hypomorphic allele exhibit pituitary and hypothalamic defects. In situ hybridization with specific markers on pituitary (A–O) or hypothalamic (P–S) frontal histological sections. A–O, Terminal differentiation of somatotrophs [Gh expressing cells (A–C)], corticotrophs and melanotrophs [Pomc1 expressing cells, D–F)], and thyrotropes and gonadotrophs [Cga expressing cells (G–I)] is unaffected in the Fgf8 hypomorph (Fgf8loxPNeo/−) embryos. However, the pituitary gland is smaller in the Fgf8 hypomorph embryos relative to Fgf8+/+ controls. Note the absence of posterior lobe in one embryo (arrow in B, E, and H). Expression of Tshβ was unaffected across the genotypes (J–L). However, a proportion of Fgf8 hypomorphs exhibited lack of Lhβ-expressing cells (M–O). P–S, The endocrine hypothalamus is severely compromised in Fgf8 hypomorph embryos as revealed by in situ hybridization with AVP (P, P′, Q, and Q′) and OT (R, R′, S, and S′) antisense riboprobes. There is an apparent reduction in numbers of AVP- and OT-expressing neurons in the SON, SCN, and PVN in the Fgf8 hymomorph embryos compared with control littermates. P′, Q′, R′, and S′ are magnified images of regions boxed in P, Q, R, and S of the same or an alternative section. T, Quantification analysis of AVP-immunoreactive neurons demonstrates a significant reduction in numbers of these neurons in the SCN and PVN nuclei of PN0 mice carrying specific combinations of Fgf8 alleles. Wt is Fgf8+/+, Het is Fgf8loxpNeo/+, and Homo is Fgf8loxPNeo/−. AL, Anterior lobe; PL, posterior lobe;. Scale bars, 200 μm. Data are mean ± sd. **, P < 0.002.

Results

Mutation analysis

After direct sequencing of 421 patients, two unrelated female patients were detected with novel mutations in exon 3 of FGF8. These included: 1) a homozygous mutation, c.566G>A, resulting in the substitution of arginine by histidine (p.R189H) (patient 1) and 2) a heterozygous mutation, c.646C>G, resulting in the substitution of glutamine by glutamic acid (p.Q216E) (patient 2). The clinical characteristics of both patients are presented in Table 1. None of 480 Caucasian controls screened exhibited either of the mutations. In addition, for patient 1, who was of Pakistani origin, screening a further 206 ethnically matched controls revealed no mutations. Neither patient identified with an FGF8 mutation had mutations in FGFR1, KAL1, PROK2, PROKR2, HESX1, or SHH.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of affected patients with FGF8 mutations

| Patient no. | Mutation | Position | Sex | Hypothalamo-pituitary | MRI | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Homozygous | c.566G>A, p.R189H | F | DI, ACTHI, evolving TSHD, PRLD | Semilobar HPE, bulky AP | DD, high arched palate, maxillary hypoplasia |

| 2 | Heterozygous | c.646C>G, p.Q216E | F | Borderline GH response to provocation | Agenesis of CC, optic nerve hypoplasia, normal pituitary | Moebius syndrome, microcephaly, DD, spastic diplegia |

DI, Diabetes insipidus; ACTHI, ACTH insufficiency; TSHD, TSH deficiency; PRLD, prolactin deficiency; CC, corpus callosum; DD, developmental delay; AP, anterior pituitary; F, female.

Patient 1

A female patient from a consanguineous family of Pakistani origin had been diagnosed antenatally with holoprosencephaly and absent corpus callosum; at birth she was noted to have microcephaly, micrognathia, and a high arched palate. She presented at the age of 7 wk with seizures and hypernatremia and was admitted to intensive care. Although her critical condition did not allow for extensive endocrine investigations, she was diagnosed with diabetes insipidus and ACTH insufficiency and has been treated with desmopressin and hydrocortisone. A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed semi-lobar holoprosencephaly with separation of the cerebral hemispheres anteriorly and failure of separation of the basal ganglia structures and the thalami from each other and across the midline. The corpus callosum was absent, and the hypothalamus was abnormal. The anterior pituitary gland was noted to be bulky, and the posterior pituitary was identified at the normal location (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Two novel mutations associated with recessive HPE and SOD. A and B, A total of 421 patients with hypopituitarism phenotypes ranging from HPE to SOD were screened for mutations in FGF8 by direct sequencing. A female patient with HPE exhibited a novel homozygous mutation at position c.566, resulting in a p.R189H substitution (A, arrow) in a highly conserved residue in all vertebrates analyzed (B). C and D, A second female patient with SOD and Moebius syndrome exhibited a novel heterozygous mutation at position c.646, leading to a p.Q216E substitution (C, arrow) in a highly conserved amino acid among mammals (D). E, Sagittal MRI scan of our SOD/Moebius syndrome patient (Q216E), demonstrating an absent corpus callosum (asterisk) but otherwise normal anterior pituitary (AP) and posterior pituitary (PP) glands. F, Sagittal and coronal MRI scans of a normal control subject and our HPE (p.R189H) patient. The latter presented with an absent corpus callosum (asterisk) and an enlarged anterior pituitary (AP). Failure of the brain to divide into its cerebral hemispheres in the patient is apparent in the coronal sections with a clearer view of the absent corpus callosum in the far right image.

A glucagon stimulation test performed at the age of 5.5 yr [height 107.6 cm (−0.6 sd score [SDS]), weight 16.6 kg (−0.9SDS)] showed a normal GH response (peak GH 29.1 μg/liter) with normal IGF-I (148 ng/ml; normal range 52–297 ng/ml) and IGF binding protein-3 (3.19 mg/liter; normal range 1.3–5.6 mg/liter), but she gradually developed TSH deficiency as shown by persistently low free T4 (FT4) concentrations, with a progressive reduction in prolactin concentrations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Serial endocrine evaluation of patient 1 (p.R189H)

| Age | Cortisol (μg/dl) | Peak GH (μg/liter) (NR >6.7 μg/liter) | FT4 (ng/dl) | FT4 NR | TSH (mU/liter) (NR <6mU/liter) | Basal PRL (μg/liter) | PRL NR (μg/liter) | Basal LH (IU/liter) | Basal FSH (IU/liter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 wk | <1–5.3 on profile | ND | 1.63 | 1.09–1.78 | 7.4 | 70.5 | 4.9–67 | <0.7 | 2.7 IU/liter |

| 21 months | ND | ND | 1.24 | 1.09–1.78 | 3.6 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 4 yr | ND | ND | 0.96 | 0.93–1.71 | 1.4 | 6.79 | 3.1–11.1 | ND | ND |

| 5.5 yr | 18 (peak GST on hydrocortisone) | 29.1 | 1.00 | 0.84–1.47 | 1.1 | 3.34 | 3.1–11.1 | <0.2 | 0.8 |

| 6.5 yr | ND | ND | 0.98 | 1.00–1.65 | 0.88 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 7 yr | ND | ND | 0.79 | 0.84–1.47 | 1.2 |

GST, Glucagon stimulation test; PRL, prolactin; ND, not done; NR, normal range.

Genetic screening revealed that she was homozygous for a novel FGF8 mutation (c.566G>A, p.R189H) involving a highly conserved region of the gene (Fig. 2, A and B). Both parents were heterozygous and had a normal phenotype with no history of delayed puberty or subfertility and a reported normal sense of smell.

Patient 2

A Caucasian female patient with SOD and agenesis of corpus callosum presented at the age of 6 yr for investigation of profound growth deceleration with a height of 99.2 cm (−2.7 SDS) and a weight of 15.8 kg (−1.9 SDS). She was born to unrelated parents, and in addition to SOD, she had microcephaly, global developmental delay with evolving spastic diplegia, and Moebius syndrome. Endocrine investigations revealed a low normal concentration of IGF-I [107 μg/liter (normal range: 53–302μg/liter)] with borderline peak GH responses to glucagon and clonidine stimulation (5.13 and 5 μg/liter, respectively), normal thyroid function, and an adequate peak cortisol in response to both glucagon (16.1 μg/dl) and synacthen (30 μg/dl) stimulation. Brain MRI revealed an absent corpus callosum and hypoplastic optic nerves with no structural abnormality of the pituitary gland (Fig. 2E). She had no evidence of any midline cleft, nor did she manifest diabetes insipidus. The patient is currently too young to test for olfactory dysfunction.

The patient was heterozygous for a novel FGF8 mutation (c.646C>G, p.Q216E) (Fig. 2C) in a highly conserved region of the gene across multiple species (Fig. 2D), whereas her unaffected mother was a carrier.

Expression analysis of FGF8 and FGFR1 in the developing human embryo

To understand the role of FGF8 and FGFR1 in human embryonic development and to bring insights into the pathogenesis of the phenotypes observed in patients harboring mutations in these genes, we performed expression analysis of FGF8 and FGFR1 in human embryos.

In situ hybridization analyses on early-staged human embryos, Carnegie stage (CS) 16, revealed FGF8 mRNA transcripts in the midline commissural plate of the developing telencephalon and telencephalic/diencephalic border and in the ventral diencephalon, but no expression was observed in Rathke's pouch (the primordium of the anterior pituitary) (Fig. 3A). In mouse, expression of Fgf8 in the ventral diencephalon is essential for Rathke's pouch induction and growth (21, 27, 28). In agreement with this notion, expression of FGFR1, which is the main receptor mediating FGF8 signaling, was detected in Rathke's pouch (Fig. 3, B and D) and in a broader domain within the ventral diencephalon (Fig. 3B). At CS 22, FGFR1 transcripts were present in the neuroepithelium of the developing brain and in Rathke's pouch (Fig. 3E). FGF8 and FGFR1 expression patterns in the human embryo parallel that of the mouse, suggesting a conserved function for FGF8 and FGFR1 in the development of these structures.

Fig. 3.

Expression of FGF8 and FGFR1 during early human development. Expression of FGF8 (A) and FGFR1 (B–E) during human embryonic CS 16 [37 d after fertilization (A and B) and CS 22 (C, D, and E)]. Sagittal (A–D) and coronal sections (E) are shown. A, FGF8 transcripts are localized in the commissural plate of the telencephalon (arrow in A), telencephalic/diencephalic border (asterisk), and the prospective hypothalamus (arrowheads in A) but not in Rathke's pouch (rp, blue arrow), the primordium of the anterior pituitary gland. B–E, FGFR1 transcripts are widely detected throughout the brain neuroepithelium (C and E) including the prospective hypothalamus (arrows in B, D, and E), hindbrain (arrowheads in B), and the developing Rathke's pouch (blue arrow in B, rp in D and E). D, An enlarged image of the boxed area in C. Scale bar (B), 200 μm; (C), 2 mm.

Hypothalamic and pituitary defects in mouse embryos carrying a hypomorphic Fgf8 allele

Mouse embryos carrying a hypomorphic allele of Fgf8 (Fgf8-loxPNeo) over a null allele (Fgf8loxPNeo/−) show severe defects in brain morphogenesis, including midbrain defects, absence of olfactory bulbs and optic chiasm, and HPE with an abnormal corpus callosum [Meyers et al. (25); Storm et al. (29)]. To further understand the pathogenesis of the defects observed in the patients carrying FGF8 mutations, we analyzed by in situ hybridization the differentiation of hormone-producing cells in the pituitary gland and the integrity of the neuroendocrine hypothalamus in Fgf8 hypomorphic mouse embryos. In addition to HPE, which was observed in two of six mutants analyzed, Fgf8loxPNeo/− embryos showed severe abnormalities in the pituitary gland and endocrine hypothalamus (Fig. 4). At 17.5 d postcoitum, we observed two different phenotypes: 1) a severe one, characterized by the substantial reduction of anterior pituitary tissue and absence of posterior lobe (two of six embryos analyzed) (Fig. 4, B, E, H, K, and N); and 2) a mild phenotype, in which the pituitary gland was morphologically more comparable with the controls (four of six embryos analyzed) (Fig. 4, C, F, I, L, and O). Despite these morphological abnormalities, the only defects in terminal differentiation of the hormone-producing cells were observed in those secreting LH.

Next, we studied the integrity of the endocrine hypothalamus in the Fgf8 hypomorph embryos. A marked reduction of AVP and oxytocin (OT) neurons was observed in the supraoptic (SON), SCN, and PVN nuclei in these mutant embryos relative to the controls (Fig. 4, P–S). Quantification of AVP-immunoreactive neurons on PN0 confirmed a significant (P < 0.002) loss of these neurons in the SCN and PVN of FGF8 hypomorphs (Fig. 4T). Together these expression analyses in mouse embryos highlight an essential role for FGF8 signaling in the formation of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and provide insights into the pathogenesis of the brain and endocrine defects observed in patients carrying mutations in FGF8 and FGFR1.

Discussion

Novel homozygous mutation in FGF8 in a female with holoprosencephaly

We have identified a novel homozygous mutation, c.566G>A (p.R189H), in exon 3 of FGF8, which resulted in an arginine substitution for histidine in the C-terminal region of the protein, in a patient with semilobar HPE associated with an absent corpus callosum and a bulky anterior pituitary on MRI. The parents of our proband are both unaffected carriers of the mutation and are first cousins. The recessive nature of this mutation, which occurs at a highly conserved residue, and its absence in 686 controls, suggests that FGF8 is critical for normal forebrain development, as indicated in a murine model carrying a hypomorphic Fgf8 allele (25, 29, 30).

The affected region of the protein is conserved across all isoforms and the variably penetrant loss-of-function heterozygous T229M mutation, which lies in the same region, has previously been associated with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism and HPE (16, 22). However, in vitro ligand receptor binding assays using bacteriological recombinant proteins appear to indicate that this FGF8 region may not be important for receptor binding (30). This suggests that FGF8 activity in vivo may require posttranslational modifications, which were absent in the recombinant proteins used in the previous study, but important for other aspects of FGF8 biology such as intracellular transport, diffusion, or protein half-life. Mouse studies strongly suggest that fine-tuning control of FGF8 signaling through gene dosage and binding to secreted inhibitors is essential for normal development. The assessment of the impact of the p.R189H mutation identified in this study on normal development awaits the development of new mouse models in the future.

Recently a role for FGF8 in the etiology of HPE has been proposed (15). However, because a cause-effect relationship was not established and mutations were found in heterozygosity, the possibility exists that mutations in other genes may underlie the observed defects (digenicity). Although loss-of-function homozygous mutations in FGF8 have been identified or predicted previously in patients with normosmic idiopathic hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism (16) and nonsyndromic cleft lip and palate, respectively (31), our patient is the first with a recessive form of HPE to be associated with an FGF8 mutation; all the other genetic mutations implicated in the disorder have been transmitted in a heterozygous state with variable penetrance. The lack of a phenotype in the heterozygous parents is particularly intriguing, given that heterozygous mutations in the gene have previously been associated with Kallmann syndrome.

Novel heterozygous mutation in FGF8 in a female with SOD and Moebius syndrome

The patient with the heterozygous p.Q216E substitution, which lies in the same region as our homozygous R189H mutation, manifested midline defects including an absent corpus callosum and hypoplastic optic nerves, reflecting a variant of SOD. A borderline GH response to stimulation with a low-normal IGF-I was the only endocrine abnormality, although one cannot exclude the possibility of an evolving endocrinopathy, particularly with reference to gonadotropin secretion.

An unusual finding in this patient was the presence of Moebius syndrome, a rare congenital dysinnervation syndrome characterized by poorly developed abducens (VI) and facial (VII) nerves (17). The condition has been associated with Kallmann syndrome in five cases (18), with the only midline association reported recently in a child with holoprosencephaly in which discontinuation of the pregnancy had been attempted with misoprostol, an agent previously linked with Moebius syndrome (32, 33). Although FGF8 has never previously been implicated in this disorder, its potential role is highlighted by its expression in the facial primordia and eyes in mice and the presence of facial skeletal defects in heterozygote Fgf8 zebrafish mutants, which resemble several human craniofacial disorders (34, 35). Furthermore, tissue-specific ablation of Fgf8 was associated with abnormal neural crest survival and patterning, which gives rise to the cranial nerves and bone, cartilage, connective tissue, and skin pigmentation (36). In agreement with this finding, the Fgf8loxPNeo/− embryos analyzed in this study also presented craniofacial defects.

The unaffected mother of the patient was the heterozygous carrier of the FGF8 mutation, suggesting variable penetrance of the mutated allele, or possibly a digenic cause of the disorder, both of which have been associated with Kallmann syndrome due to FGF8 mutations. Cases of the former are not unusual, with variable phenotypic-presentations within a given family, making it difficult to predict an expected phenotype based on the genotype alone (37). Variations in environmental exposure may also contribute to phenotypic variations (38). Alternatively, more than one gene could contribute to the condition, particularly in the most severe form (39). Screening for mutations in HESX1 and SHH, as well as other Kallmann syndrome-associated genes, failed to establish a digenic cause, although there may be a contribution from an as-yet-unknown gene, given that no genetic etiology has been identified in the majority of patients with Kallmann syndrome or midline forebrain defects. The association of Moebius syndrome with SOD in our patient, and with Kallmann syndrome and HPE in other patients, implicates an intrinsic link between these disorders in the form of overlapping phenotypes; both our data and those published previously point to associations with mutated FGF8 or related genes.

Fgf8/FGF8 is expressed in the developing hypothalamus and implicated in normal hypothalamo-pituitary development

Our expression analysis demonstrates that Fgf8/FGF8 is expressed in the telencephalon and ventral diencephalon (prospective hypothalamus) but not in Rathke's pouch, which is destined to form the anterior pituitary (39). Expression of FGFR1 colocalizes with FGF8 in the developing hypothalamus and is also found in Rathke's pouch. The similar localization of Fgf8/FGF8 expression in both mice and humans as presented herein suggests that the disrupted pituitary and hypothalamus in the Fgf8 hypomorphic mouse may parallel the endocrine deficits observed in our patients. The patient with the homozygous FGF8 mutation presented a bulky anterior pituitary with the presence of a posterior pituitary despite the association with diabetes insipidus, on MRI, and of note, the murine hypomorphs showed marked variability in the size of the anterior pituitary and the presence or otherwise of the posterior pituitary. Additionally, the reduction in AVP in the magnocellular SON and PVN of the hypomorphs may correlate with the diabetes insipidus observed in our patient, which is due to insufficient vasopressin signaling, a hormone important for maintaining urinary salt/water reabsorption (40). Furthermore, Fgf8 hypomorphs also harbor defects in the parvicellular AVP neurons in the SCN, suggesting that other hypothalamic functions such as circadian output may be dysregulated. Although not quantified in this study, the reduction in OT staining in SON and PVN nuclei is consistent with recently published data, which showed significantly reduced OT immunoreactivity in the same hypomorphic mice as used herein (26). Our data suggest that the hypopituitary phenotypes observed in our patients may be the result of reduced functional FGF8 in the diencephalon, leading to deficiencies in the neuroendocrine hypothalamus.

In conclusion, we report mutations in FGF8 that are associated with complex midline phenotypes, including the first autosomal recessive case of HPE and a potential role in a patient with SOD and Moebius syndrome, the genetic basis of the latter having remained elusive to date. Analysis of our patients and murine hypomorphs, as well as the conserved expression patterns of Fgf8/FGF8 and Fgfr1/FGFR1 in mouse and human, suggests that FGF8 signaling is important for telencephalic and hypothalamo-pituitary axis development and that mutations in this gene play a role in the pathogenesis of midline defects such as HPE and SOD as well as Kallmann syndrome.

Acknowledgments

Human embryonic material was provided by the Human Developmental Biology Resource (www.hdbr.org), which is supported by the Medical Research Council Grant G0700089 and the Wellcome Trust Grant 082557. We thank Dr. Gail Martin and Dr. Mark Lewandosky for providing mouse embryos.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the British Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes awarded to V.T. and M.T.D. I.S.F. is supported by the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council Centre for Obesity and Related Disorders and the U.K. National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre. M.J.M. is supported by a project grant from the Birth Defects Foundation-NewLife. M.T.D. is also funded by Great Ormond Street Children's Charity. J.-P.M.-B. is supported by Wellcome Trust Grants 084361 and 086545. E.P. is supported by El Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación Grant BFU2010-16538. C.G.-M. is supported by the National Institute for Health Research Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children/Univeristy College London Institute of Child Health Specialist Biomedical Research Centre.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- AVP

- Arginine vasopressin

- CS

- Carnegie stage

- FGF

- fibroblast growth factor

- FT4

- free T4

- HPE

- holoprosencephaly

- MRI

- magnetic resonance imaging

- OT

- oxytocin

- PN

- postnatal day

- PVN

- paraventricular nucleus

- SCN

- suprachiasmatic nucleus

- SDS

- sd score

- SOD

- septo-optic dysplasia

- SON

- supraoptic nucleus.

References

- 1. Kelberman D, Dattani MT. 2007. Genetics of septo-optic dysplasia. Pituitary 10:393–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kelberman D, Rizzoti K, Avilion A, Bitner-Glindzicz M, Cianfarani S, Collins J, Chong WK, Kirk JM, Achermann JC, Ross R, Carmignac D, Lovell-Badge R, Robinson IC, Dattani MT. 2006. Mutations within Sox2/SOX2 are associated with abnormalities in the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis in mice and humans. J Clin Invest 116:2442–2455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Webb EA, Dattani MT. 2010. Septo-optic dysplasia. Eur J Hum Genet 18:393–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dattani MT, Martinez-Barbera JP, Thomas PQ, Brickman JM, Gupta R, Mårtensson IL, Toresson H, Fox M, Wales JK, Hindmarsh PC, Krauss S, Beddington RS, Robinson IC. 1998. Mutations in the homeobox gene HESX1/Hesx1 associated with septo-optic dysplasia in human and mouse. Nat Genet 19:125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ragge NK, Brown AG, Poloschek CM, Lorenz B, Henderson RA, Clarke MP, Russell-Eggitt I, Fielder A, Gerrelli D, Martinez-Barbera JP, Ruddle P, Hurst J, Collin JR, Salt A, Cooper ST, Thompson PJ, Sisodiya SM, Williamson KA, Fitzpatrick DR, van Heyningen V, Hanson IM. 2005. Heterozygous mutations of OTX2 cause severe ocular malformations. Am J Hum Genet 76:1008–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alatzoglou KS, Dattani MT. 2009. Genetic forms of hypopituitarism and their manifestation in the neonatal period. Early Hum Dev 85:705–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Birkebaek NH, Patel L, Wright NB, Grigg JR, Sinha S, Hall CM, Price DA, Lloyd IC, Clayton PE. 2003. Endocrine status in patients with optic nerve hypoplasia: relationship to midline central nervous system abnormalities and appearance of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis on magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:5281–5286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mehta A, Hindmarsh PC, Mehta H, Turton JP, Russell-Eggitt I, Taylor D, Chong WK, Dattani MT. 2009. Congenital hypopituitarism: clinical, molecular and neuroradiological correlates. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 71:376–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koregol MC, Bellad MB, Nilgar BR, Metgud MC, Durdi G. 2010. Cyclopia with shoulder dystocia leading to an obstetric catastrophe: a case report. J Med Case Reports 4:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roessler E, Du YZ, Mullor JL, Casas E, Allen WP, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Roeder ER, Ming JE, Ruiz i Altaba A, Muenke M. 2003. Loss-of-function mutations in the human GLI2 gene are associated with pituitary anomalies and holoprosencephaly-like features. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:13424–13429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bendavid C, Dupé V, Rochard L, Gicquel I, Dubourg C, David V. 2010. Holoprosencephaly: an update on cytogenetic abnormalities. Am J Med Genet 154C:86–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abe Y, Oka A, Mizuguchi M, Igarashi T, Ishikawa S, Aburatani H, Yokoyama S, Asahara H, Nagao K, Yamada M, Miyashita T. 2009. EYA4, deleted in a case with middle interhemispheric variant of holoprosencephaly, interacts with SIX3 both physically and functionally. Hum Mut 30:E946–E955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paulussen AD, Schrander-Stumpel CT, Tserpelis DC, Spee MK, Stegmann AP, Mancini GM, Brooks AS, Collée M, Maat-Kievit A, Simon ME, van Bever Y, Stolte-Dijkstra I, Kerstjens-Frederikse WS, Herkert JC, van Essen AJ, Lichtenbelt KD, van Haeringen A, Kwee ML, Lachmeijer AM, Tan-Sindhunata GM, van Maarle MC, Arens YH, Smeets EE, de Die-Smulders CE, Engelen JJ, Smeets HJ, Herbergs J. 2010. The unfolding clinical spectrum of holoprosencephaly due to mutations in SHH, ZIC2, SIX3 and TGIF genes. Eur J Hum Genet 18:999–1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ribeiro LA, Quiezi RG, Nascimento A, Bertolacini CP, Richieri-Costa A. 2010. Holoprosencephaly and holoprosencephaly-like phenotype and GAS1 DNA sequence changes: report of four Brazilian patients. Am J Med Genet 152A:1688–1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosenfeld JA, Ballif BC, Martin DM, Aylsworth AS, Bejjani BA, Torchia BS, Shaffer LG. 2010. Clinical characterization of individuals with deletions of genes in holoprosencephaly pathways by aCGH refines the phenotypic spectrum of HPE. Hum Genet 127:421–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Falardeau J, Chung WC, Beenken A, Raivio T, Plummer L, Sidis Y, Jacobson-Dickman EE, Eliseenkova AV, Ma J, Dwyer A, Quinton R, Na S, Hall JE, Huot C, Alois N, Pearce SH, Cole LW, Hughes V, Mohammadi M, Tsai P, Pitteloud N. 2008. Decreased FGF8 signaling causes deficiency of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in humans and mice. J Clin Invest 118:2822–2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bianchi B, Copelli C, Ferrari S, Ferri A, Sesenna E. 2010. Facial animation in patients with Moebius and Moebius-like syndromes. Int J Oral Max Surg 39:1066–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jennings JE, Costigan C, Reardon W. 2003. Moebius sequence and hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism. Am J Med Genet 123A:107–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Villegas SN, Canham M, Brickman JM. 2010. FGF signalling as a mediator of lineage transitions—evidence from embryonic stem cell differentiation. J Cell Biochem 110:10–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ohuchi H, Hori Y, Yamasaki M, Harada H, Sekine K, Kato S, Itoh N. 2000. FGF10 acts as a major ligand for FGF Receptor 2 IIIb in mouse multi-organ development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 277:643–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kelberman D, Rizzoti K, Lovell-Badge R, Robinson IC, Dattani MT. 2009. Genetic regulation of pituitary gland development in human and mouse. Endocr Rev 30:790–829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arauz RF, Solomon BD, Pineda-Alvarez DE, Gropman AL, Parsons JA, Roessler E, Muenke M. 2010. A hypomorphic allele in the FGF8 gene contributes to holoprosencephaly and is allelic to gonadotropin-releasing hormone deficiency in humans. Mol Syndromol 1:59–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Trarbach EB, Abreu AP, Silveira LF, Garmes HM, Baptista MT, Teles MG, Costa EM, Mohammadi M, Pitteloud N, Mendonca BB, Latronico AC. 2010. Nonsense mutations in FGF8 gene causing different degrees of human gonadotropin-releasing deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:3491–3496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gaston-Massuet C, Andoniadou CL, Signore M, Sajedi E, Bird S, Turner JM, Martinez-Barbera JP. 2008. Genetic interaction between the homeobox transcription factors HESX1 and SIX3 is required for normal pituitary development. Dev Biol 324:322–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meyers EN, Lewandoski M, Martin GR. 1998. An Fgf8 mutant allelic series generated by Cre- and Flp-mediated recombination. Nat Genet 18:136–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brooks LR, Chung WC, Tsai PS. 2010. Abnormal hypothalamic oxytocin system in fibroblast growth factor 8-deficient mice. Endocrine 38:174–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhu X, Gleiberman AS, Rosenfeld MG. 2007. Molecular physiology of pituitary development: signaling and transcriptional networks. Physiol Rev 87:933–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Takuma N, Sheng HZ, Furuta Y, Ward JM, Sharma K, Hogan BL, Pfaff SL, Westphal H, Kimura S, Mahon KA. 1998. Formation of Rathke's pouch requires dual induction from the diencephalon. Development (Cambridge, England) 125:4835–4840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Storm EE, Garel S, Borello U, Hebert JM, Martinez S, McConnell SK, Martin GR, Rubenstein JL. 2006. Dose-dependent functions of Fgf8 in regulating telencephalic patterning centers. Development (Cambridge, England) 133:1831–1844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Olsen SK, Li JY, Bromleigh C, Eliseenkova AV, Ibrahimi OA, Lao Z, Zhang F, Linhardt RJ, Joyner AL, Mohammadi M. 2006. Structural basis by which alternative splicing modulates the organizer activity of FGF8 in the brain. Gene Dev 20:185–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Riley BM, Mansilla MA, Ma J, Daack-Hirsch S, Maher BS, Raffensperger LM, Russo ET, Vieria AR, Dodé C, Mohammadi M, Marazita ML, Murray JC. 2007. Impaired FGF signaling contributes to cleft lip and palate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:4512–4517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pirmez R, Freitas ME, Gasparetto EL, Araújo AP. 2010. Moebius syndrome and holoprosencephaly following exposure to misoprostol. Pediatr Neurol 43:371–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vargas FR, Schuler-Faccini L, Brunoni D, Kim C, Meloni VF, Sugayama SM, Albano L, Llerena JC, Jr, Almeida JC, Duarte A, Cavalcanti DP, Goloni-Bertollo E, Conte A, Koren G, Addis A. 2000. Prenatal exposure to misoprostol and vascular disruption defects: a case-control study. Am J Med Genet 95:302–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Albertson RC, Yelick PC. 2007. Fgf8 haploinsufficiency results in distinct craniofacial defects in adult zebrafish. Dev Biol 306:505–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aoto K, Nishimura T, Eto K, Motoyama J. 2002. Mouse GLI3 regulates Fgf8 expression and apoptosis in the developing neural tube, face, and limb bud. Dev Biol 251:320–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang X, Kilgallen S, Andreeva V, Spicer DB, Pinz I, Friesel R. 2010. Conditional expression of Spry1 in neural crest causes craniofacial and cardiac defects. BMC Dev Biol 10:48–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ming JE, Muenke M. 2002. Multiple hits during early embryonic development: digenic diseases and holoprosencephaly. Am J Hum Genet 71:1017–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Scriver CR. 2002. Why mutation analysis does not always predict clinical consequences: explanations in the era of genomics. J Pediatr 140:502–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Takagi H, Nagashima K, Inoue M, Sakata I, Sakai T. 2008. Detailed analysis of formation of chicken pituitary primordium in early embryonic development. Cell Tissue Res 333:417–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gamba G. 2010. Vasopressin regulates the renal Na+-Cl− cotransporter. Am J Physiol 298:F500–F501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]