Abstract

Objective

To develop a conceptual framework for investigating the role of racial/ethnic residential segregation on health care disparities.

Data Sources and Settings

Review of the MEDLINE and the Web of Science databases for articles published from 1998 to 2011.

Study Design

The extant research was evaluated to describe mechanisms that shape health care access, utilization, and quality of preventive, diagnostic, therapeutic, and end-of-life services across the life course.

Principal Findings

The framework describes the influence of racial/ethnic segregation operating through neighborhood-, health care system-, provider-, and individual-level factors. Conceptual and methodological issues arising from limitations of the research and complex relationships between various levels were identified.

Conclusions

Increasing evidence indicates that racial/ethnic residential segregation is a key factor driving place-based health care inequalities. Closer attention to address research gaps has implications for advancing and strengthening the literature to better inform effective interventions and policy-based solutions.

Keywords: Racial/ethnic residential segregation, health care disparities, health care access, social determinants of health

Despite a substantial literature documenting persistent disparities in health and health care utilization by race/ethnicity (Smedley, Stith, and Nelson 2008; AHRQ 2010), our understanding of the cause of these disparities is incomplete. Although health insurance coverage, individual socioeconomic position, provider bias, and discrimination have all been demonstrated to impede access to care, there is increasing interest in elucidating the role of place in shaping observed health care inequities (Zaslavsky and Ayanian 2009). Recent evidence suggests that health care resources often reflect the geographic distribution of race/ethnicity. As a prominent organizing feature of American society, we focus on racial/ethnic residential segregation, to elucidate a framework for investigating the role of place in disparities in health care.

Racial/ethnic residential segregation refers to the degree to which two or more groups live separately from one another in a geographic area (Massey and Denton 2003). Levels of racial/ethnic segregation (hereafter segregation) in the United States are higher than economic segregation (Massey, Rothwell, and Domina 2010). The segregation of blacks is distinctive and remains higher in comparison with other racial/ethnic groups. Competing explanations of the cause and persistence of segregation such as personal preference, socioeconomic status (SES), and prejudice have been theoretically articulated and empirically tested and suggest that personal preferences have not substantially contributed to endemic levels of segregation (Charles 2002). Although overt discriminatory policies and institutional practices promoting segregation are now illegal, segregation continues to have lasting implications for both individual and community well-being (Massey and Denton 1988). Considered a spatial manifestation of institutionalized discrimination, segregation policies protected whites from residential contact with blacks and fostered racial inequality (Massey and Denton 1988). Segregation continues to perpetuate racial disparities in educational and employment opportunities, concentrate poverty, and shape social and physical features of neighborhoods (Williams and Collins 2011). These mechanisms also have serious consequences for individual and community health (Acevedo-Garcia et al. 2003; Kramer and Hogue 2005). The excess burden of poorer health resulting from segregation may be further exacerbated by disparities in health care. Similar pathways affecting health status may also present barriers to accessing and utilizing health care resources in segregated neighborhoods. The purpose of this paper is to synthesize findings from the health services research literature and present a framework that extends a seminal model of segregation and health disparities (Williams and Collins 2011) to address segregation as a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health care. We identify gaps in the understanding of segregation and health care disparities, discuss methodological and conceptual challenges, and outline needed research to advance the understanding of how segregation contributes to the inequitable provision of health care.

Conceptual Framework

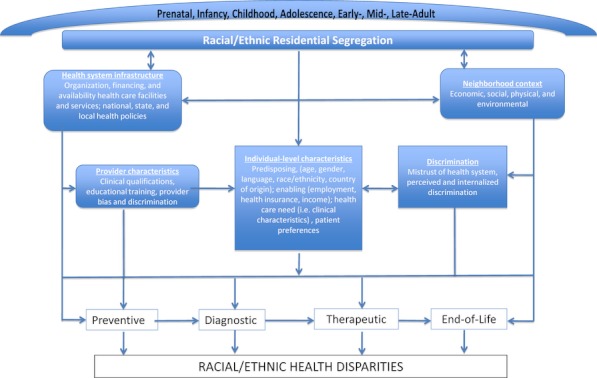

The mechanisms linking segregation to health care disparities are not clearly understood. The conceptual framework guiding this discussion posits that segregation is a fundamental factor influencing racial/ethnic disparities in access, quality, and the appropriate utilization of health care services (Figure). The framework builds upon prior models of segregation and health (Williams and Collins 2011; Schulz et al. 2009) and health care disparities (Landrine and Corral 2009; Sarrazin et al. 2003) situating segregation as a central factor driving racial/ethnic disparities. However, the model makes novel contributions in several ways. First, it delineates multiple mechanisms at the “neighborhood” (term is broadly used to represent geographic area of residence), health care system, provider, and individual level through which segregation contributes to health care disparities. Second, the model shows how segregation operates through the aforementioned factors to influence access, utilization, and quality across the full spectrum of health care, encompassing, preventive, diagnostic, therapeutic, and end-of-life care. Finally, the model reflects a lifecourse perspective and views segregation as a factor shaping the utilization and quality of health care services across various stages of an individual's life span. Attention to the cumulative effects of exposure to segregation along the continuum of health care has the potential to illuminate opportunities for research and action.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model Describing the Contribution of Racial/Ethnic Residential Segregation across the Life Span and Its Influence on the Continuum of Health Care

Mechanisms

Neighborhood Context

The economic, physical, social, and environmental context of neighborhoods may be shaped by segregation (Williams and Collins 2011; Acevedo-Garcia et al. 2003). Limited opportunities for employment and education and the high concentration of poverty that characterizes segregated neighborhoods can impede one's ability to obtain equitable health care services independent of individual-level factors (Kirby and Kaneda 2007). For example, neighborhoods characterized by economic and social disadvantage may have difficulty in attracting primary- and specialty-care physicians (Auchincloss, Van Nostrand, and Ronsaville 2011). Segregation may also influence neighborhood resources that facilitate access to care. For example, segregation may lead to social networks that influence the development of health-promoting institutional resource brokers, organizations that have ties to businesses, and nonprofit and governmental agencies with resources (Small 2004) that provide access to affordable and culturally sensitive health care services. More specifically, neighborhood childcare centers have been shown to be important resource brokers for health and dental care (Small, Jacobs, and Massengill 2005). Future research needs to identify the extent to which they compensate for the deficits of care and buffer against material disadvantage in highly segregated contexts.

Health Care System

The health care infrastructure (i.e., organization, financing, and availability of health care services) is related to the broader socioeconomic conditions of a community and thus has substantial implications for health care disparities. The historical context of segregation has played a major role in configuring health care facilities and services. Prior to the 1960s, blacks and whites were mandated by law to receive care either in separate facilities or on separate floors within a facility (Smith 2006). The 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibited legal segregation of health care institutions receiving federal funds and hospital desegregation was further facilitated by the enactment of Medicare in 1965 (Smith 2002). Yet vestiges of these historic patterns of segregation in health care facilities remain today. Recent studies have documented that hospital-level segregation and hospital racial composition are associated with health care disparities in treatment and utilization (Skinner et al. 2005; Barnato et al. 2004; Clarke, Davis, and Nailon 2007; Sarrazin et al. 2003; Merchant et al. 1993).

Important variations in health care financing, spending, and the delivery of services are associated with geographic location. These geographic variations have consequences for safety-net systems, the distribution of high-quality facilities and providers, and ultimately the health care of individuals, particularly those who reside in segregated neighborhoods. Institutions that predominantly care for the uninsured and underserved are in precarious financial conditions and several have closed, resulting in diminished access and availability of care in disadvantaged neighborhoods (Walker et al. 2005). These facilities, generally located in segregated neighborhoods, are more likely to have higher rates of adverse patient safety events (Ly et al. 2003) or have limited resources, such as less access to diagnostic imaging services (Kim, Samson, and Lu 2003), which partially account for health care disparities.

The supply and availability of providers often parallels the magnitude of segregation in a neighborhood and can ultimately contribute to health care disparities. For example, barriers to the recruitment and retention of primary care and specialty physicians in segregated areas impede access to care for children and adults (Guagliardo et al. 2009; Hayanga et al. 2009; Walker et al. 2003). Some health care settings lack providers or a health care workforce with linguistic diversity to provide interpretation and translation services to Limited English Proficiency populations (Smedley, Stith, and Nelson 2008). Moreover, local patterns of segregation have been shown to influence physician participation in Medicaid in highly segregated areas (Greene, Blustein, and Weitzman 2007).

Provider-Level Characteristics

Racial/ethnic health care disparities may emerge in part from the association between characteristics of health care providers and segregation. Provider quality as measured by the clinical qualifications and educational training of physicians is lower in neighborhoods with a high concentration of blacks or Hispanics (Bach et al. 2010). Providers practicing in segregated neighborhoods are more likely to be confronted with clinical, logistical, and administrative challenges (Fiscella and Williams 2001). For example, physicians who work in segregated neighborhoods are more likely to have a patient mix with a higher proportion of Medicaid patients and receive significantly lower reimbursements. Other research reveals that provider racial bias or discrimination can lead to biased treatment recommendations, less positive affect for patients, and poorer communication (Schulman et al. 2008; Stevens and Shi 2008; Green et al. 2002). Enhanced awareness of the association between neighborhood factors and health care may enable health care providers to identify those most vulnerable (Brown, Ang, and Pebley 2005). However, our current understanding is limited regarding how provider behavior can combine with segregation to affect health care delivery.

Perceived Discrimination

Research documents the persistence of racial discrimination across multiple social contexts in society (Pager and Shepherd 2010). Self-reports of these experiences have been shown to adversely affect health status and health care utilization (Williams and Mohammed 2001). Greater perceived racial discrimination has been associated with delays in care-seeking, filling prescriptions, use of alternative care as a substitute for conventional health care, and distrust of the health system (LaVeist, Nickerson, and Bowie 2010; Bazargan et al. 2005; Van Houtven et al. 2005; Casagrande et al. 2006). Although some evidence suggests that reports of discrimination are higher in less segregated areas and more diverse communities (Welch, Sigelman, and Bledsoe 2010; Hunt et al. 2009b), research examining the joint effect of segregation and perceived discrimination on patterns of health care utilization has remained largely unexplored. Moreover, older blacks who grew up prior to the civil rights movement may perceive segregation and discrimination differently than younger populations. Exploration of these issues may provide insight into the complex determinants of racial/ethnic health care disparities.

Individual-Level Economic, Health, and Social Status

The Andersen model describes how predisposing characteristics (e.g., age, gender, language, country of origin), enabling resources (e.g., health insurance, income, employment), and health care need (e.g., disease severity, perceived symptoms) determine health care utilization. However, these factors alone do not explain health care utilization patterns (Fiscella et al. 2010; Saha et al. 2007). Although patient preferences and care-seeking behaviors contribute to disparities, they are not the major sources of disparities in health care quality (Smedley, Stith, and Nelson 2008). Segregation and racial composition can influence each of these domains (Gaskin et al. 2004). For example, education attainment, income, and employment status tend to be lower in segregated neighborhoods (Massey and Denton 1988). Additionally, poorer health status has been associated with higher levels of segregation (Kramer and Hogue 2005).

Spectrum of Clinical Care

Preventive Care

Access and utilization of primary and preventive care are associated with better population health and smaller disparities in health (Starfield, Shi, and Macinko 1999). Access to physicians and health care providers in segregated neighborhoods is often limited and may explain some of the disparities in utilization of preventive care. This is supported by studies showing that substandard spatial access to primary care providers for children was more extreme in segregated neighborhoods (Guagliardo et al. 2009). Adult blacks who live in predominantly black neighborhoods were also less likely to have an office-based physician visit in the past year compared with whites in predominantly white zip codes (Gaskin et al. 2004). However, one study found that residence in predominantly black counties was associated with increased mammography use, and residence in predominantly Hispanic counties was associated with greater use of cholesterol screenings (Benjamins, Kirby, and Huie 2006).

Diagnostic

Racial/ethnic disparities in the receipt of diagnostic procedures are not fully explained by clinical differences, disease presentation, or severity of disease. Segregation may shape access and patterns of utilization. The availability of subspecialty providers, such as gastroenterologists and radiation oncologists, was inversely proportional to the percentage of blacks in a county (Hayanga et al. 2009). However, studies examining segregation and stage of diagnosis in breast cancer have been mixed. For example, one study found little evidence that metropolitan-area segregation or racial composition influenced racial/ethnic differences in stage of diagnosis of breast cancer among women in California (Warner and Gomez 2010), while another study noted smaller black–white disparities in early-stage diagnosis of breast cancer in highly segregated areas when compared with less segregated areas (Haas et al. 2007). The authors surmised that these findings could be attributed to targeted community outreach programs for early detection.

Therapeutic

Even after gaining access to medical care, blacks are often less likely to receive appropriate medical treatment in comparison with whites. The access and utilization of therapeutic options in segregated neighborhoods may account for some of the disparity. For example, a recent analysis found that patients with pneumonia who live in predominantly black or Hispanic neighborhoods were less likely than whites to receive appropriate pneumonia care (Hausmann et al. 2008b). Waiting time for a kidney transplant was longer for black and white patients living in zip codes with a high proportion of black residents in comparison to zip codes with a low proportion of black residents (Rodriguez et al. 2004). Furthermore, pharmacies located in segregated neighborhoods are less likely to stock sufficient medications to meet community needs compared to those located in less segregated areas (Morrison et al. 2003; Cooper et al. 2003).

End-of-Life

Disparities in access, utilization, and quality of palliative and end-of-life care may be influenced by the magnitude of segregation. Utilization of hospice care tends to be lower in neighborhoods with a higher proportion of blacks and Hispanics (Haas et al. 2004). While disparities in the use of hospice in neighborhoods with more black and Hispanic residents may be in part attributable to preferences, it may also reflect a fragmented nursing home system related to historical patterns of segregation (Smith et al. 2007). Substantial disparities in nursing home quality also remain (Smith et al. 2007). For example, high levels of segregation have been associated with a lower staffing ratio, inspection deficiencies, and greater financial vulnerability of nursing homes (Smith et al. 1998, 2007).

Methodological, Conceptual, and Research Considerations

The framework provides a structure for elucidating the role of place in health care disparities, using the example of segregation. Challenges to our understanding of the complex relationship between residential segregation and health care disparities arise both from the limitations of the research to date and from key methodological, conceptual, and research considerations. While issues related to conceptualizing and estimating the effect of segregation on health disparities have been discussed in detail elsewhere (Kramer and Hogue 2010; Landrine and Corral 2009; Osypuk and Acevedo-Garcia 2000; White and Borrell 2011), this paper builds upon these reviews and explicitly highlights concerns related to health services research.

Formal versus Proxy Segregation Measures

Segregation may be measured using a formal or a proxy measure. Formal measures of segregation are conceptualized using five geographic patterns: evenness, exposure, concentration, centralization, and clustering (Massey and Denton 2003). Similar to studies focused on disparities in health outcomes, in the health services literature, segregation is generally conceptualized using the evenness or exposure dimension; however, one recent study employed all five dimensions (Warner and Gomez 2010). Evenness refers to the degree to which groups are evenly distributed in space (Kramer and Hogue 2005). Exposure reflects opportunities for interaction between members of the same versus different racial groups in a defined geographical area. Indices used to measure these dimensions of segregation range from 0 (least segregated) to 1 (most segregated), where ≥0.60 is the standard to reflect high segregation (Massey and Denton 2003). Despite a substantial literature on measuring segregation, most health services research uses racial/ethnic composition as a proxy measure of segregation instead of employing formal measures, to characterize the racial/ethnic context of an area. Racial/ethnic composition reflects the proportion of a group in a given geographic area. Studies have used percent black (Haas et al. 2004; Rodriguez et al. 2004), percent Hispanic (Haas et al. 2004; Gaskin et al. 2004), percent Asian (Hayanga et al. 2011), and a combined percentage of blacks and Hispanics (Haas et al. 2004) to characterize racial/ethnic concentration.

The relationship between both formal and proxy measures of segregation and health care disparities may depend on the specification of the variable. For example, studies have used thresholds ranging as low as 16 percent to reflect high levels of neighborhood homogeneity (Benjamins, Kirby, and Huie 2006; Haas et al. 2004). Although some researchers have noted that the association between racial/ethnic composition and the respective health care outcome was robust and independent of threshold selection, the lack of standardized definitions makes it difficult to make comparisons across studies. Studies generally characterize segregation or racial composition using dichotomous variables, with continuous measures less frequently used. If segregation is assumed to have a linear relationship, continuous variables should be used; alternatively, if there are hypothesized threshold effects, then the variables should be categorized (Kramer et al. 2008). The choice of using a dichotomous versus a continuous variable should be guided by the underlying assumption regarding how segregation operates in conjunction with the specific health access, utilization, or quality outcome.

The empirical implications of using a formal versus proxy measure of segregation are unclear, particularly given the limited number of health services studies that have used formal measures. Correlation coefficients between formal and proxy measures of segregation have ranged between 0.062 and 0.80 (White and Borrell 2011). Conceptually, racial/ethnic composition may not capture the complex process of racial inequality, because it does not account for the racial clustering of the population or other characteristics like neighborhood boundaries or proximity to other neighborhoods (Kramer et al. 2008). More studies are needed to determine the extent to which different formal measures of segregation relate to a specific access or utilization outcome. For example, black–white disparities in use of cardiac revascularization procedures were associated with residential evenness, but unrelated to segregation as defined by exposure (Sarrazin et al. 2003). From a conceptual perspective, formal measures offer greater potential insights into disparities in health care utilization and access patterns given the spatial distribution of health care facilities and providers. Furthermore, the combination of formal, spatial segregation measures and spatial analytic techniques has the potential to extend our understanding of mechanisms linking segregation to health care utilization and accessibility.

Spatial Segregation Measures and Spatial Analysis

Recently developed spatial segregation measures reflect a more flexible definition of neighborhood experience (Wong 2010; Reardon and O'Sullivan 2010; Brown and Chung 2004). Although these measures have not yet been used in the health services research literature, they may enhance our understanding of health care disparities through a more accurate operationalization of segregation. Spatial analysis provides a set of tools to describe, quantify, and explain the geographic organization of health care services (Rushton 2004). More specifically, analyses of health care based on geographic information system (GIS) can be used to plan and evaluate health service delivery (McLafferty 2009) and may be particularly useful for elucidating place-based disparities. For example, the Dartmouth Atlas data have been widely used to document geographic differences in health care across the country (Onega et al. 2011). In addition, several studies have used spatial analyses to increase the precision of measuring spatial access to health care resources and providers as it relates to segregation or neighborhood racial composition (Guagliardo et al. 2009; Zenk, Tarlov, and Sun 1993; Dai 2007). Because health care utilization and access may not only depend on the resources within an individual's community but the distance to facilities or providers in surrounding neighborhoods (Luo and Wang 2006), classifying the relationship between segregation and relevant health resources is important. A growing body of research is analyzing the spatial dependence of resources between adjacent areas (Diez-Roux and Mair 2010). With the recent advances in GIS and multilevel analyses, future studies may be able to incorporate and extensively characterize features of neighborhood context that may mediate the association between segregation and health care with greater precision.

Several issues must be considered when applying spatial techniques to health services research. First, choosing a measure of spatial accessibility may depend on the type of residential area. For example, travel distance to providers may be more appropriate to measure in some rural areas than in more dense urban areas. Second, although spatial differences in the availability of health care facilities or providers are important, these differences do not reflect the quality of health care resources. Finally, place of residence may be an inadequate proxy for “place” of health service use, as daily activity spaces (i.e., near work or shopping areas) may be more representative of places where individuals seek health care (McLafferty 2009), particularly for young and middle-age adults (Guagliardo 2006).

Geographic Unit of Analysis

Because disparities have been documented at the regional, state, county, and city levels, a primary challenge for health services research is defining neighborhoods and operationalizing the relevant geographic unit of analysis (Diez-Roux 2009). Segregation studies generally use metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), as the macro-unit of analysis, although other levels of aggregation such as city, county, and zip code have been used (White and Borrell 2011). While some have argued that segregation is most appropriately measured at the MSA level (Osypuk and Acevedo-Garcia 2000), the choice of a macro-unit of analysis to measure segregation should be dictated by a theoretical justification of the causal processes (Diez-Roux and Mair 2010). Empirical tests to determine the best level to measure segregation to elucidate health care differences are limited. One recent study compared various dimensions of traditional and spatial measures of segregation to determine precision in the magnitude of disparities in preterm birth (Kramer et al. 2008). These findings suggest that the magnitude of segregation may be dependent on the geographic scale used to define segregation. Explicitly delineating a specific geographic level is paramount because of the significant implications for identifying points of intervention.

Health-Facility Segregation

The contribution of health-facility segregation, independent of neighborhood segregation, is also a factor that health services researchers should consider. Because blacks and whites largely live in different neighborhoods, systematic differences arise in the places where they seek care (Barnato et al. 2004). The segregation of health care facilities may, independently of neighborhood segregation, contribute to health care disparities (Sarrazin et al. 2003). Several studies have noted the magnitude of segregation in hospitals (Barnato et al. 2001; Clarke, Davis, and Nailon 2007; Sarrazin et al. 2003; Merchant et al. 1993) and nursing homes (Smith et al. 1998) as a factor contributing to health care disparities. Although there is no consensus regarding the optimal level to measure and intervene on health care disparities, further conceptualization and definition of segregation measures at various geographic aggregations of neighborhood and at the level of health care facilities may further elucidate racial/ethnic health care disparities.

Data Availability

Data availability often determines the choice of geographic unit for research. Prior reviews have identified contextual factors from a variety of sources that can be linked with nationally representative health and health care datasets (Hillemeier et al. 2003; Liang, Phillips, and Haas 2000). For example, Hillemeier et al. () outlined a multidimensional conceptual framework of community contextual characteristics, ranging from employment, political, behavioral, and transport domains, that could plausibly influence patterns of population health. Large national datasets such as the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey or the Area Resource File are replete with information for exploring complex questions related to contextual level characteristics and may be used to look at MSA-level differences in segregation across the country. However, these large datasets do not provide opportunities for revealing complex local relationships. More important, some health-related datasets do not make geographic identifiers below the level of the county available due to concerns about confidentiality. However, these more granular data may be available through specific arrangements (data use agreements, use of restricted files in secure data centers) in compliance with privacy directives.

Segregation of Racial/Ethnic Subgroups and Immigrants

Immigrants of all major racial/ethnic groups tend to be healthier than their U.S.-born counterparts (Singh and Miller 1999). However, some immigrants lack health insurance or have limited English proficiency and encounter barriers to accessing and utilizing health care. These barriers may be further exacerbated by segregation. Although examining the association between health care outcomes and the geographic distribution of race/ethnicity has largely focused on African Americans, understanding the challenges faced by foreign-born blacks and individuals of Hispanic ethnicity is essential for a comprehensive understanding of racial/ethnic health care disparities.

Studies using African Americans samples have not sufficiently taken black heterogeneity into account, which is an important limitation as foreign-born blacks make up nearly one quarter of the black population in several large metropolitan areas. A few studies have explored black immigrant health care utilization patterns (Lucas, Barr-Anderson, and Kington 2003; Hammond et al. 2008a), but no studies to our knowledge have investigated this in the context of segregation. Given that Caribbean black immigrants have higher levels of segregation than African Americans (Logan and Deane 2003), closer attention to the segregation patterns of black immigrants may inform the health care services literature.

Increasingly, studies are examining the influence of Hispanic racial composition on health care access. Factors such as the proportion of the population that speaks Spanish may be important for effective communication and the dissemination of health-related information that can protect against discrimination within health care settings. For example, Mexican immigrants residing in neighborhoods with a higher percentage of Spanish speakers and immigrants have had better access to care when compared to U.S.-born Mexican Americans residing in the same area (Gresenz, Rogowski, and Escarce 2011). Furthermore, studies examining whether the effect of segregation may differ for Hispanic ethnic subgroup is also limited. An analysis exploring the effects of segregation on self-rated health among Mexican and Puerto Rican residents in Chicago found that the association with segregation was not uniform (Lee and Ferraro 2009). Future studies are necessary to explore the relationships between the characteristics of place of residence and health care utilization for ethnic subgroups of Hispanics and other populations.

Health Care-Promoting Aspects of Segregation

The literature has mostly emphasized the deleterious effects of segregation on health care access and utilization. An assumption of a homogeneous negative association between segregation and health care is inconsistent with some of the current evidence. The framework presented includes pathways where segregation may be both positively and negatively linked with patterns of health services use. A full understanding of the complex interplay of segregation with other neighborhood- and individual-level demographic characteristics can shed light on how these factors influence access and utilization. Different levels of group concentration may contribute to higher collective efficacy in a neighborhood or foster the patterning of social networks and/or community resources that can enable access to care (Browning and Cagney 2007). For example, the proportion of the population who speaks Spanish may contribute to the creation of neighborhood social networks that facilitate health care utilization (Gresenz, Rogowski, and Escarce 2011). Moreover, higher group level concentration may also lead to a greater prevalence of racial concordance among physicians and patients which has the potential to facilitate access to care (Haas et al. 2004). Thus, future research should explore mechanisms in segregated neighborhoods that may enable access and utilization.

Conclusion

The elimination of racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care is one of the most important objectives of the national health agenda (Healthy People 2020). The Affordable Care Act, enacted in 2010, promises comprehensive health reform with the potential to reduce racial/ethnic health care disparities. While it represents an important step toward eliminating disparities in health care, equity in health care access will likely require ongoing assessment and additional intervention (Zhu et al. 2005; Alegria 2012). Health care reform could also weaken the safety net and reduce access for some vulnerable racial/ethnic groups and their communities (Andrulis and Siddiqui 2011). Taking into account the geographic and place-based disparities, such as those driven by segregation, is therefore crucial to charting a course for long-term improvements in health care disparities (Williams, McClellan, and Rivlin 2001).

The shift in the demographic characteristics of the U.S. population has in part contributed to a change in the racial landscape of neighborhoods. While the percentage of neighborhoods that are exclusively white has decreased dramatically in recent years (Rawling et al. 2008), the percentage of neighborhoods highly segregated by race and increasingly by SES merits continued investigation. Our framework highlights the influence of segregation in shaping access, utilization, and quality of health care services across the entire spectrum of clinical care. The inequitable distribution of the health care resources across this spectrum can have severe consequences for the long-term health of individuals and communities. Advancing and strengthening the evidence base to disentangle the complex interplay of factors requires attention to methodological, conceptual, and research considerations. Future research is needed to determine the optimal operationalization of segregation for specific outcomes and contexts, explore the association between segregation and health care services across a broader range of clinical conditions, and examine the role of segregation in the health care of children and adolescents. The continued study of how segregation and other characteristics of place may contribute to diminishing disparities in health care access, utilization, and quality by identifying avenues for intervention and policy-based solutions.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: The authors have no affiliation with any organization with a direct or indirect financial interest in the subject matter discussed in this manuscript. This research was conducted with support from the P50 CA148596 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (D. R. W., J. S. H.), and the Health Disparities Research Program of Harvard Catalyst|The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH Award UL1 RR 025758 and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers) (J. S. H.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers, the National Center for Research Resources, or the National Institutes of Health. Also, we acknowledge feedback from Drs. Benjamin Cook and John Ayanian on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- Acevedo-Garcia D, Lochner KA, Osypuk TL, Subramanian SV. “Future Directions in Residential Segregation and Health Research: A Multilevel Approach”. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93((2)):215–21. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AHRQ. National Healthcare Disparities Report. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. AHRQ Publication No. 11-0005. [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Lin J, Chen C-N, Duan N, Cook B, Meng X-L. “The Impact of Insurance Coverage in Diminishing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Behavioral Health Services”. Health Services Research. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01403.x. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrulis DP, Siddiqui NJ. “Health Reform Holds Both Risks and Rewards for Safety-Net Providers and Racially and Ethnically Diverse Patients”. Health Affairs. 2011;30((10)):1830–6. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auchincloss AH, Van Nostrand JF, Ronsaville D. “Access to Health Care for Older Persons in the United States: Personal, Structural, and Neighborhood Characteristics”. Journal of Aging and Health. 2001;13((3)):329–54. doi: 10.1177/089826430101300302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. “Primary Care Physicians Who Treat Blacks and Whites”. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351((6)):575–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnato AE, Lucas FL, Staiger S, Wennberg DE, Chandra A. “Hospital-Level Racial Disparities in Acute Myocardial Infarction Treatment and Outcomes”. Medical Care. 2005;43((4)):308–19. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156848.62086.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnato AE, Berhane Z, Weissfeld LA, Chang CCH, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, I. C. U. E.-O. Robert Wood Johnson Fdn “Racial Variation in End-of-Life Intensive Care Use: A Race or Hospital Effect?”. Health Services Research. 2006;41((6)):2219–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00598.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazargan M, Norris K, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Akhanjee L, Calderon JL, Safvati SD, Baker RS. “Alternative Healthcare Use in the Under-Served Population”. Ethnicity & Disease. 2005;15((4)):531–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamins MR, Kirby JB, Huie SAB. “County Characteristics and Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Use of Preventive Services”. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39((4)):704–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AF, Ang A, Pebley AR. “The Relationship between Neighborhood Characteristics and Self-Rated Health for Adults with Chronic Conditions”. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97((5)):926–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LA, Chung SY. “Spatial Segregation, Segregation Indices and the Geographical Perspective”. Population Space and Place. 2006;12((2)):125–43. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Cagney KA. “Neighborhood Structural Disadvantage, Collective Efficacy, and Self-Rated Physical Health in an Urban Setting”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43((4)):383–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande SS, Gary TL, LaVeist TA, Gaskin DJ, Cooper LA. “Perceived Discrimination and Adherence to Medical Care in a Racially Integrated Community”. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22((3)):389–95. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles CZ. “The Dynamics of Racial Residential Segregation”. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:167–207. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SP, Davis BL, Nailon RE. “Racial Segregation and Differential Outcomes in Hospital Care”. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2007;29((6)):739–57. doi: 10.1177/0193945907303167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HLF, Bossak BH, Tempalski B, Friedman SR, Des Jarlais DC. “Temporal Trends in Spatial Access to Pharmacies That Sell Over-the-Counter Syringes in New York City Health Districts: Relationship to Local Racial/Ethnic Composition and Need”. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2009;86((6)):929–45. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9399-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai DJ. “Black Residential Segregation, Disparities in Spatial Access to Health Care Facilities, and Late-Stage Breast Cancer Diagnosis in Metropolitan Detroit”. Health & Place. 2010;16((5)):1038–52. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Roux AV. “Investigating Neighborhood and Area Effects on Health”. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91((11)):1783–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Roux AV, Mair C. “Neighborhoods and Health”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186:125–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Williams DR. “Health Disparities Based on Socioeconomic Inequities: Implications for Urban Health Care”. Academic Medicine. 2004;79((12)):1139–47. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, Saver BG. “Disparities in Health Care by Race Ethnicity, and Language among the Insured — Findings from a National Sample”. Medical Care. 2002;40((1)):52–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaskin DJ, Dinwiddie GY, Chan KS, McCleary R. “Residential Segregation and Disparities in Health Care Services Utilization”. Medical Care Research and Review. 2011 doi: 10.1177/1077558711420263. Epub ahead of print. DOI: 10.1177/1077558711420263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, Ngo LH, Raymond KL, Iezzoni LI, Banaji MR. “Implicit Bias among Physicians and Its Prediction of Thrombolysis Decisions for Black and White Patients”. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22((9)):1231–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene J, Blustein J, Weitzman BC. “Race, Segregation, and Physicians' Participation in Medicaid”. Milbank Quarterly. 2006;84((2)):239–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2006.00447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresenz CR, Rogowski J, Escarce JJ. “Community Demographics and Access to Health Care among US Hispanics”. Health Services Research. 2009;44((5)):1542–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00997.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guagliardo MF. “Spatial Accessibility of Primary Care Concepts: Concepts, Methods and Challenges”. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2004;3((1)):3–21. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guagliardo MF, Ronzio CR, Cheung I, Chacko E, Joseph JG. “Physician Accessibility: An Urban Case Study of Pediatric Providers”. Health & Place. 2004;10((3)):273–83. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2003.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas JS, Phillips KA, Sonneborn D, McCulloch CE, Baker LC, Kaplan CP, Perez-Stable EJ, Liang SY. “Variation in Access to Health Care for Different Racial/Ethnic Groups by the Racial/Ethnic Composition of an Individual's County of Residence”. Medical Care. 2004;42((7)):707–14. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000129906.95881.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas JS, Earle CC, Orav JE, Brawarsky P, Neville BA, Acevedo-Garcia D, Williams DR. “Lower Use of Hospice by Cancer Patients Who Live in Minority versus White Areas”. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22((3)):396–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0034-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas JS, Earle CC, Orav JE, Brawarsky P, Keohane M, Neville BA, Williams DR. “Racial Segregation and Disparities in Breast Cancer Care and Mortality”. Cancer. 2008;113((8)):2166–72. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas JS, Earle CC, Orav JE, Brawarsky P, Neville BA, Williams DR. “Racial Segregation and Disparities in Cancer Stage for Seniors”. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23((5)):699–705. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0545-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP, Mohottige D, Chantala K, Hastings JF, Neighbors HW, Snowden L. “Determinants of Usual Source of Care Disparities among African American and Caribbean Black Men: Findings from the National Survey of American Life”. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2011;22((1)):157–75. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann LRM, Ibrahim SA, Mehrotra A, Nsa W, Bratzler DW, Mor MK, Fine MJ. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Pneumonia Treatment and Mortality”. Medical Care. 2009;47((9)):1009–17. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a80fdc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayanga AJ, Kaiser HE, Sinha R, Berenholtz SM, Makary M, Chang D. “Residential Segregation and Access to Surgical Care by Minority Populations in US Counties”. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2009;208((6)):1017–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayanga AJ, Waljee AK, Kaiser HE, Chang DC, Morris AM. “Racial Clustering and Access to Colorectal Surgeons, Gastroenterologists, and Radiation Oncologists by African Americans and Asian Americans in the United States A County-Level Data Analysis”. Archives of Surgery. 2009;144((6)):532–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. “Healthy People 2020”. [accessed January 4, 2012]. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/Consortium/HP2020Framework.pdf. [PubMed]

- Hillemeier MM, Lynch J, Harper S, Casper M. “Measuring Contextual Characteristics for Community Health”. Health Services Research. 2003;38((6)):1645–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt MO, Wise LR, Jipguep MC, Cozier YC, Rosenberg L. “Neighborhood Racial Composition and Perceptions of Racial Discrimination: Evidence from the Black Women's Health Study”. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2007;70((3)):272–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kim TH, Samson LF, Lu N. “Racial/Ethnic Disparities in the Utilization of High-Technology Hospitals”. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2010;102((9)):803–10. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30677-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JB, Kaneda T. “Neighborhood Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Acces to Health Care”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;2005((46)):15–31. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MR, Hogue CR. “Place Matters: Variation in the Black/White Very Preterm Birth Rate across US Metropolitan Areas, 2002-2004”. Public Health Reports. 2008;123((5)):576–85. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MR, Hogue CR. “Is Segregation Bad for Your Health?”. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2009;31((1)):178–194. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MR, Cooper HL, Drews-Botsch CD, Waller LA, Hogue CR. “Do Measures Matter? Comparing Surface-Density-Derived and Census-Tract-Derived Measures of Racial Residential Segregation”. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2010;3:3–21. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-9-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Corral I. “Separate and Unequal: Residential Segregation and Black Health Disparities”. Ethnicity and Disease. 2009;19((2)):179–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. “Attitudes about Racism, Medical Mistrust, and Satisfaction with Care among African American and White Cardiac Patients”. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;57:146–61. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Ferraro KF. “Neighborhood Residential Segregation and Physical Health among Hispanic Americans: Good, Bad, or Benign?”. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48:131–48. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang SY, Phillips KA, Haas JS. “Measuring Managed Care and Its Environment Using National Surveys: A Review and Assessment”. Medical Care Research and Review. 2006;63((6)):9S–36S. doi: 10.1177/1077558706293836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan JR, Deane G. Albany, NY: Lewis Mumford Center for Comparative Urban and Regional Research, University of Albany; Black Diversity in Metropolitan America. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas JW, Barr-Anderson DJ, Kington RS. “Health Status, Health Insurance, and Health Care Utilization Patterns of Immigrant Black men”. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93((10)):1740–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo W, Wang FH. “Measures of Spatial Accessibility to Health Care in a GIS Environment: Synthesis and a Case Study in the Chicago Region”. Environment and Planning B-Planning & Design. 2003;30((6)):865–84. doi: 10.1068/b29120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ly DP, Lopez L, Isaac T, Jha AK. “How Do Black-Serving Hospitals Perform on Patient Safety Indicators? Implications for National Public Reporting and Pay-for-Performance”. Medical Care. 2010;48((12)):1133–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f81c7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Denton NA. “The Dimensions of Residential Segregation”. Social Forces. 2010;67((2)):281–315. [Google Scholar]

- Denton . American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Rothwell J, Domina T. “The Changing Bases of Segregation in the United States”. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2009;626:74–90. doi: 10.1177/0002716209343558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLafferty SL. “GIS and Health Care”. Annual Review of Public Health. 2003;24:25–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.012902.141012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant RM, Becker LB, Yang FF, Groeneveld PW. “Hospital Racial Composition: A Neglected Factor in Cardiac Arrest Survival Disparities”. American Heart Journal. 2011;161((4)):705–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison RS, Wallenstein S, Natale DK, Senzel RS, Huang LL. “‘We Don't Carry That’ — Failure of Pharmacies in Predominantly Nonwhite Neighborhoods to Stock Opioid Analgesics”. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342((14)):1023–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004063421406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onega T, Duell EJ, Shi X, Demidenko E, Goodman D. “Influence of Place of Residence in Access to Specialized Cancer Care for African Americans”. Journal of Rural Health. 2010;26((1)):12–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osypuk TL, Acevedo-Garcia D. “Beyond Individual Neighborhoods: A Geography of Opportunity Perspective for Understanding Racial/Ethnic Health Disparities”. Health & Place. 2010;16((6)):1113–23. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pager D, Shepherd H. “The Sociology of Discrimination: Racial Discrimination in Employment, Housing, Credit, and Consumer Markets”. Annual Review of Sociology. 2008;34:181–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawling L, Harris L, Turner MA, Padilla S. Neighborhood Change in Urban America. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon SF, O'Sullivan DO. “Measures of Spatial Segregation”. Sociological Methodology. 2004;34:121–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez RA, Sen S, Mehta K, Moody-Ayers S, Bacchetti P, O'Hare AM. “Geography Matters: Relationships among Urban Residential Segregation, Dialysis Facilities, and Patient Outcomes”. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;146((7)):493–501. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton G. “Public Health, GIS,and Spatial Analytic Tools”. Annual Review of Public Health. 2003;24:43–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.012902.140843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Freeman M, Toure J, Tippens KM, Weeks C, Ibrahim S. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the VA Health Care System: A Systematic Review”. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23((5)):654–71. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin MSV, Campbell ME, Richardson KK, Rosenthal GE. “Racial Segregation and Disparities in Health Care Delivery: Conceptual Model and Empirical Assessment”. Health Services Research. 2009;44((4)):1424–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.00977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, Kerner JF, Sistrunk S, Gersh BJ, Dube R, Taleghani CK, Burke JE, Williams S, Eisenberg JM, Escarce JJ. “The Effect of Race and Sex on Physicians' Recommendations for Cardiac Catheterization”. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340((8)):618–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Kannan S, Dvonch JT, Israel BA, Allen A, 3rd, James SA, House JS, Lepkowski J. “Social and Physical Environments and Disparities in Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: The Healthy Environments Partnership Conceptual Model”. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2005;113((12)):1817–25. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Miller BA. “Health, Life Expectancy, and Mortality Patterns among Immigrant Populations in the United States”. Canadian Journal of Public Health-Revue Canadienne De Sante Publique. 2004;95((3)):I14–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03403660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner J, Chandra A, Staiger D, Lee J, McClellan M. “Mortality after Acute Myocardial Infarction in Hospitals That Disproportionately Treat Black Patients”. Circulation. 2005;112((17)):2634–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small ML. “Neighborhood Institutions as Resource Brokers: Childcare Centers, Interorganizational Ties, and Resource Access among the Poor”. Social Problems. 2006;53((2)):274–92. [Google Scholar]

- Small ML, Jacobs EM, Massengill RP. “Why Organizational Ties Matter for Neighborhood Effects: Resource Access through Childcare Centers”. Social Forces. 2008;87((1)):387–414. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DB. “Addressing Racial Inequities in Health Care: Civil Rights Monitoring and Report Cards”. Journal of Health Politics Policy and Law. 1998;23((1)):75–105. doi: 10.1215/03616878-23-1-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DB. Health Care Divided: Race and Healing a Nation. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DB, Feng ZL, Fennel ML, Zinn JS, Mor V. “Separate and Unequal: Racial Segregation and Disparities in Quality across US Nursing Homes”. Health Affairs. 2007;26((5)):1448–58. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DB, Feng ZL, Fennell ML, Zinn J, Mor V. “Racial Disparities in Access to Long-Term Care: The Illusive Pursuit of Equity”. Journal of Health Politics Policy and Law. 2008;33((5)):861–81. doi: 10.1215/03616878-2008-022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starfield B, Shi LY, Macinko J. “Contribution of Primary Care to Health Systems and Health”. Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83((3)):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens GD, Shi LY. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Primary Care Experiences of Children: A Review of the Literature”. Medical Care Research and Review. 2003;60((1)):3–30. doi: 10.1177/1077558702250229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Houtven CH, Voils CI, Oddone EZ, Weinfurt KP, Friedman JY, Schulman KA, Bosworth HB. “Perceived Discrimination and Reported Delay of Pharmacy Prescriptions and Medical Tests”. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20((7)):578–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker KO, Ryan G, Ramey R, Nunez FL, Beltran R, Splawn RG, Brown AF. “Recruiting and Retaining Primary Care Physicians in Urban Underserved Communities: The Importance of Having a Mission to Serve”. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100((11)):2168–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker KO, Leng M, Liang LJ, Forge N, Morales L, Jones L, Brown A. “Increased Patient Delays in Care Care after the Closure of Martin Luther King Hospital: Implications for Monitoring Health System Changes”. Ethnicity & Disease. 2011;21((3)):356–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner ET, Gomez SL. “Impact of Neighborhood Racial Composition and Metropolitan Residential Segregation on Disparities in Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis and Survival between Black and White Women in California”. Journal of Community Health. 2010;35((4)):398–408. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9265-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch S, Sigelman L, Bledsoe T. Race and Place: Race Relationships in an American City. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- White K, Borrell LN. “Racial/Ethnic Residential Segregation: Framing the Context of Health Risk and Health Disparities”. Health & Place. 2011;17((2)):438–48. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Collins C. “Racial Residential Segregation: A Fundamental Cause of Racial Disparities in Health”. Public Health Reports. 2001;116((5)):404–16. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, McClellan MB, Rivlin AM. “Beyond the Affordable Care Act: Achieving Real Improvements in Americans' Health”. Health Affairs. 2010;29((8)):1481–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. “Discrimination and Racial Disparities in Health: Evidence and Needed Research”. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32((1)):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DW. “Spatial Indexes of Segregation”. Urban Studies. 1993;30((3)):559–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. “Integrating Research on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care over Place and Time”. Medical Care. 2005;43:303–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000159975.43573.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenk SN, Tarlov E, Sun JM. “Spatial Equity in Facilities Providing Low- or No-Fee Screening Mammography in Chicago Neighborhoods”. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2006;83((2)):195–210. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Brawarsky P, Lipsitz S, Huskamp H, Haas JS. “Massachusetts Health Reform and Disparities in Coverage, Access and Health Status”. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25((12)):1356–62. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1482-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data availability often determines the choice of geographic unit for research. Prior reviews have identified contextual factors from a variety of sources that can be linked with nationally representative health and health care datasets (Hillemeier et al. 2003; Liang, Phillips, and Haas 2000). For example, Hillemeier et al. () outlined a multidimensional conceptual framework of community contextual characteristics, ranging from employment, political, behavioral, and transport domains, that could plausibly influence patterns of population health. Large national datasets such as the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey or the Area Resource File are replete with information for exploring complex questions related to contextual level characteristics and may be used to look at MSA-level differences in segregation across the country. However, these large datasets do not provide opportunities for revealing complex local relationships. More important, some health-related datasets do not make geographic identifiers below the level of the county available due to concerns about confidentiality. However, these more granular data may be available through specific arrangements (data use agreements, use of restricted files in secure data centers) in compliance with privacy directives.